Abstract

This article builds from scholarship in Environmental Education Research (EER) and Critical Global Citizenship Education calling for more explicit attention to how teaching global issues is embedded in the colonial matrix of power. We also consider the extent to which recent calls in EER for explicit attention to coloniality connect to discussions about posthuman thinking through a shared critical reading of modernity. We argue that ethical approaches to global issues, and pedagogical processes and practices that would contribute to them, are possible only if we recognize the relations of power that have shaped history and engage with critical modes of inquiry. Furthermore, we argue for the need to engage deeply with and confront historical patterns in concrete pedagogical practices in order to interrupt our own epistemic, political, ethical, and strategic place and categories. Finally, we will draw upon an example from our classroom-based research to consider how our findings relate to what is being called for in the critical scholarship of praxis, as informed by empirical studies.

Decoloniality as praxis

Our collaborative work takes up a common critique across Environmental Education Research (EER) and critical work in Global Citizenship Education (GCE) regarding reproductions of colonial systems of power. While there is substantive scholarship and theoretical work in this area (Andreotti, Citation2011; Andreotti & Souza, Citation2012; Blenkinsop, Affifi, Piersol, & Sitka-Sage, Citation2017; Le Grange, Citation2007; Martin, Citation2011; Matthews, Citation2011; Pashby, Citation2012; Tuck, McKenzie, & McCoy, Citation2014), we seek to contribute a praxis point of view to empirically engage these theoretical critiques with classroom practice. According to Giroux, praxis “represents the transition from critical thought to reflective intervention in the world” (Giroux, Citation1981, p. 117). Building from this definition, we argue teaching about global issues in classrooms is an intervention. We draw on Andreotti (Citation2014) to consider pedagogical praxis that moves beyond the reflective to promote reflexive interventions. Our approach to praxis intervenes into and traces individual assumptions to the collective construction of such assumptions that define what is real, ideal and knowable (Andreotti, Citation2014). We are specifically interested in intervening into, and delinking from the colonial systems, or the colonial matrix of power (cmp), in which global issues and mainstream approaches to teaching about them are embedded. Thus, drawing on Mignolo (Citation2018), we argue for decoloniality as a type of praxis to support ethical global issues pedagogy. We understand decoloniality as both an analytic of modernity/coloniality – a way of making intelligible the cmp itself – and “a set of creative processes leading to decolonial narratives legitimizing decolonial ways of doing and living” (Mignolo, Citation2018, p. 146). Using praxis used in this sense, we promote explicitly identifying and, therefore, seeking to undo some of the linkages that maintain the cmp through our epistemological framings: “Undoing is doing something; delinking presupposes relinking for something else. Consequently, decoloniality is undoing and redoing, it is praxis” (Mignolo, Citation2018, p. 12).

The empirical studies we have conducted focus on the important role of the teacher who presents, frames and engages with ethical global issues in the classroom (Pashby & Sund, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Sund & Pashby, Citation2019). These issues include migration, climate change, unequal power and the growing gaps between the rich and poor. We argue that ethical approaches to global issues, and pedagogical processes and practices that would contribute to them, are possible only if we recognize the relations of power that have shaped history and engage with critical modes of inquiry. In other words, ethical global issues pedagogy requires making the cmp visible through an analytic of decoloniality. The deep concern regarding reification of the cmp has persisted through various eras of development, sustainability, environmental and global education, as has been highlighted in light of early 21st century work in both EER and GCE. We are interested in how teaching about such issues is practiced and contextualized by teachers in northern Europe in various subjects areas including science, social sciences/studies and geography in our recent studies. We have investigated how teachers design pedagogy to implement complex global issues, and how this work can be developed and supported by highlighting the cmp. While one project included student and teacher contributions to discussions in classes (Sund & Pashby, Citation2019), another focused on teachers’ reflections about their practice (Pashby & Sund, Citation2019a, Citation2019b). In both cases, we sought to build theory from practice or, as described by Walsh (Citation2018), “theorizing from and with praxis” (p. 84) and, in environmental education research, developing “practice theory” about ecopedagogy (Payne, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). Thus, in this article, we consider how our theorizing of decoloniality speaks to and from pedagogical realities of today’s classrooms.

We draw on discussions about coloniality and decoloniality to focus on the importance of delinking to an ethical approach to studying today’s global environmental issues. We will consider the arguments of some postcolonial and decolonial scholars, focusing on the work of Mignolo, who established the importance of deeply considering eurocentrism and how the modern colonial matrix of power continues to constrain possibilities for relating ethically within our shared planet. As Stein (Citation2019) notes, there is not a single lineage of decolonial thought being connected through overlapping work in post-colonial, anti-colonial, Indigenous, Black and abolitionist studies and social movements. We will center critiques stressing the importance of ruptures and a deeply different pluralism of approaches that decenter Eurocentric modernism seeing as, simply speaking, more modernity will not solve the issues of how modern development is complicit with systems of exploitation and oppression. As explained by Walsh (Citation2018), we are all within modernity, there is no outside. Modernity is coterminous with not easily a corrective to key problems we continue to have (oppression, exploitation, dispossession and degradation of nature). The benefits enabled by the realities of the oppressions occurring under the cmp are unequally experienced. As white, non-indigenous women with strong socio-economic privilege, we recognize this as a key reflexive positioning of our research, and similarly, teachers of global issues in northern Europe where our studies have been based occupy various positions of privilege. The challenge is to think and learn from where we are located and look for innovations and ruptures that outline new strategies of action and solidarity (Walsh, Citation2018, p. 27).

We also outline how the premises of the cmp contribute to and respond to research in environmental and sustainability education (ESE) and will use them to consider the current status of (post-and) decolonial approaches in EER. Here we will also relate to/consider the extent to which recent calls in EER for explicit attention to coloniality connect to discussions about posthuman thinking through a shared critical reading of modernity. To what extent is decoloniality as praxis offering something distinct from or complementary to posthumanist approaches? In keeping with Payne (Citation2020) we see posthumanism as an “intellectual recourse” that might help researchers new to EER, so we add further consideration of the extent to which a decolonial analytic asks similar or differently useful questions to that identified in posthuman theory. We then suggest implications for decolonial strategies in secondary education and what possibilities and challenges a decoloniality approach presents for the current context of teaching in northern Europe. Finally, we will draw upon an example from our classroom-based research to consider how our theoretical contributions emerge from and speak to empirical work in classrooms, exploring how our findings relate to what is being called for in the critical scholarship of praxis.

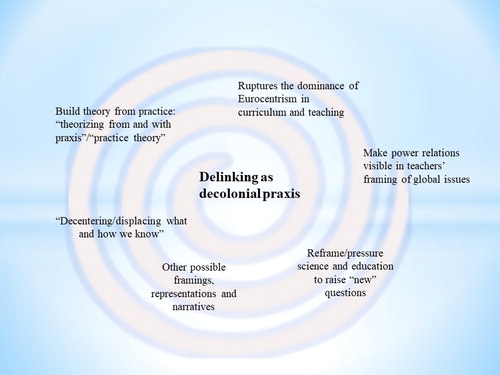

In keeping with the framing of this Special Issue and its focus on the global politics of knowledge production in EER and “new” theory in North-South representations, our precise focus is summarized in our amended Mindmap in (based on the original Mindmap presented in this special issue’s introduction – Rodrigues et al., Citation2020).

The current status of post-, anti- and decolonial approaches in EER

In recent years, several researchers in ESE have discussed the role of Indigenous, post-, and decolonizing perspectives (e.g., land education, place-based education and settler colonialism). Matthews (Citation2011) notes that the environmental injustices and problems facing the planet provide the occasion to think more carefully about pedagogy and how postcolonial theory and interdisciplinarity suggested in postcolonial ecocriticism can inform the practice of education for a sustainable future. Matthews (Citation2011) argues that if we do not connect globalization, postcolonialism, and environmental matters, then “inequality and injustice are not linked to historical and locally specific environmental contexts” (p. 267). As a consequence, subjugation and continuing marginalization of indigenous and non-Western worldviews and knowledge are perpetuated through “the assumption that educational solutions to contemporary environmental problems can be found in the addition of more science-based environmental education, education for sustainability, or climate change management courses and programs” (Matthews, Citation2011, p. 274).

Writing from settler-colonial contexts, Tuck and Yang (Citation2012), Tuck et al. (Citation2014) and Tuck and McKenzie (Citation2015) highlight the necessity of centering historical and current contexts of colonization in education on and in relation to land, also emphasizing that colonialism is not an event contained in the past, but indeed ongoing. Tuck and Yang (Citation2012) caution against using the term “decolonization” without bringing attention to Indigenous agency and Indigenous rights to land and resources. The authors point to unsettling calls to “decolonize schools” and “decolonize student thinking”, thus turning decolonization into “a metaphor for other things we want to do to improve our societies and schools” (p. 1). Following Tuck and Yang (Citation2012), Patel (Citation2014) draws on Calderon (Citation2014) to raise the unmet promises of the term decolonization, proposing that an anticolonial stance “seems to meet more fully the task of locating the hydra-like shape-shifting yet implacable logics of settler colonialism” (p. 360). In reflecting on her own social location and responsibilities within settler colonialism, Patel (Citation2014) thus contextualizes her work as anticolonial to quiet down and take pause from the overuse of decolonization. She works to “leverage both terms” and to focus on naming and opposing settler colonial logics and practices while also recognizing locating these genealogies does not “directly address the repatriation of land and alterations to material conditions” (p. 360).

By elaborating on how to counter coloniality in educational research, Patel (Citation2014) notes a lack of answerability from mainstream frames of educational research to Indigenous epistemologies: “Answerability means that we have responsibilities as speakers, listeners, and those responsibilities include stewardship of ideas and learning, not ownership” (Patel, Citation2014, p. 372). In the same vein, Blenkinsop et al. (Citation2017) call for “an anti-colonial praxis for ecopedagogy” as a reminder to listen to “the voices of the silenced” (p. 349). Our work thus builds off of these calls for careful attention to what decolonial projects claim, thus our use of Mignolo’s (Citation2018) notion of decoloniality as a praxis not an ultimate promise draws from Patel’s (Citation2014) focus on naming logics of knowledge and knowledge production.

Le Grange (Citation2007) and Kayira (Citation2015) suggest the worldview of Ubuntu/uMunthu as a platform to challenge the dominant truths espoused by Western thought. Ma Rhea (Citation2015, Citation2018) suggests that to break the stranglehold of colonial legacy and mindset in the current, dominant model of education system (in this case in Australia) requires both potentially valuable inter-cultural “crossings” between Indigenous and non-indigenous approaches to education and a paradigmatic and systems approach to change toward an Indigenist, rights-based perspective. Taking an Indigenist perspective means a commitment to a pro-Indigenous worldview and a questioning of the colonial mindset. Such a perspective implies leadership and management in education (and in the national curriculum) that directly recognize and support Indigenous rights, lifeways and perspectives without implying that the supporter is Indigenous (Ma Rhea, Citation2018). Like Mignolo, Ma Rhea (Citation2015) makes an argument for disruptions or shifts in sensemaking created through coloniality of knowledge. It is the latter, the delinking and decentering of narratives of modernity that we have found to be an entry point into working with classrooms in northern Europe. Indeed, Davis and Todd (Citation2017) frame the colonial period as the underlying cause of climate change and argue that modernity itself are responsible for the ecological crisis (and its associated problems in the cultural, political, and economic spheres): “the current environmental crises which are named through the designation of the Anthropocene, can be viewed as a continuation of, rather than a break from, previous eras that begin with colonialism and extend through advanced capitalism” (Davis & Todd, Citation2017, p. 771).

A central question raised by the SI and in the Mindmap of the Introduction (Rodrigues et al., Citation2020) is how (new ∼ not new) movements toward decentering might reframe/pressure science (education) to raise “new” questions, come up with “new” designs (). For the context of teaching about global issues in northern Europe we, as researchers and educators, believe that decoloniality as praxis offers a decentered orientation for situated and historical critique that recognizes explicitly and therefore identifies and aims to depart from and/or rupture the dominance of Eurocentrism in curriculum and teaching. From a decoloniality perspective, the concept “decentering” refers to displacing what we thought we knew, how we knew it, and how we came to know it or, as described by Walsh and Mignolo (Citation2018), creating and illuminating pluriversal paths “that disturb the totality from which the universal and the global are most often perceived” (p. 2). Acknowledging that we work from within a modern-colonial grammar and that schools are themselves fully complicit in the material and epistemological injustices embedded within coloniality, we are arguing for de-centering rather than stepping over the colonial systems of power in any type of “new” design. Rather than suggest a “new” design, we argue for the importance of on-going grappling with pluricentred or “plural ontologies” and “different ways of being in the world” from the Mindmap. Here we draw on Walter Mignolo (Mignolo, Citation2009, Citation2011a, Citation2011b, Citation2018), who sees decoloniality as a method of analysis that is both an epistemic and political project, reminding us that our knowledges are situated and that we speak from a particular location within power structures. We center our engagement with the debates about what is allegedly “new” in EER and re-center discussions within EER on criticisms of modernity and its vision of capitalism, development and consumption.

Decoloniality and the “colonial matrix of power”

In the broadest/most general terms, decoloniality, as described by Mignolo (Citation2011a), is the project to delink the trap of the entwined concept “modernity/coloniality” (p. xxi). Mignolo (Citation2011a) argues that the rhetoric of modernity aiming at persuading humanity of its progress through promises of economic growth, development and market democracy goes hand in hand with and legitimizes the logic of coloniality. Thus, coloniality is implicated in modernity in that the modern world (political, economic, epistemic, ethnic, sexual, etc.) is inextricably linked with the systems of oppression that define coloniality (slavery, genocide, over-exploitation, dispossession, etc.). The decolonial analytic starts from epistemic delinking or, in other words, epistemic disobedience (Mignolo, Citation2011b). Mignolo (Citation2011a) uses the term “monocultures of the mind” (p. 140) from Shiva (Citation1993) to describe dominant knowledge premised on a singular narrative of modernity — salvation, progress, development, individual welfare and consumption. Through epistemic disobedience, one recognizes knowledge and denaturalize it at the same time. As researchers and educators, we work to delink our approaches through epistemological disobedience by recognizing how a dominant system, including the education systems in which we work, is also a local system with its basis in a particular culture and history (Mignolo, Citation2018, p. 161). We aim to be disobedient to the normalization of Eurocentrism, and to deeply consider and delink local-global relations within the cmp.

Mignolo (Citation2011a, Citation2018) draws on Quijano’s (Citation2000; Citation2007) introduction of the concept of coloniality to describe European colonial expansion and its extension of a “colonial matrix of power” (cmp) that continues to the present day. The cmp focuses on how the colonial past is still active in the inequalities of the present and consists of four interrelated domains/spheres of management and control (cf. Noxolo, Citation2017): economy (through global capitalism); authority (through political power, law-making and policymaking); racism, gender and sexuality (through a particular kind of social agent as norm: male, White, heterosexual and Westerner); and finally, subjectivity and knowledge (through education and control of institutions of knowledge, such as universities – cf. the SI critiques of “new” forms of post-intellectual colonization, even global academic imperialism, in Rodrigues et al., Citation2020, and Payne, 2020). Mignolo (Citation2011a) discussed “nature” as a possible fifth domain/sphere that lies between the domains of economics and politics, but rightly points out that the question is not where to “file” nature, but rather what are the issues that emerge from the coloniality of nature on environmental issues. He concluded, much in line with what is explained in the SI Introduction as “the lingering tendencies of Northern/Western academic colonization” (Rodrigues et al., Citation2020, p. xx), that it is a problem with “the idea of nature as something outside of human beings” that has been consolidated and persists (in Western thought or) in “the hegemonic domain of scholarship” (Mignolo, Citation2011a, p. 10). Thus, recognizing the cmp not only recognizes how colonial power relations continues to leave lingering marks in the four described areas, but also how man/human who invented the cmp, sets himself apart from nature.

Mignolo (Citation2011a) explains how the racial and patriarchal foundation of knowledge that manages and controls the different spheres of the matrix (and its logic) proceeded through three different stages that span from 1500 to present day: An initial stage of salvation (saving the souls through conversion to Christianity), a civilizing mission (management of bodies that Foucault analyzed as bio-politics1), and an on-going stage characterized by the domination of corporations and the market where citizens are converted into consumer entrepreneurs (Mignolo, Citation2011a, p. 14). The strong claim in Mignolo’s work is the geopolitical structure/world order that remains today is established and inherited by the coloniality of power. The rhetoric of modernity in words like economic progress, growth, development “hides” the deeply problematic model, perpetuated through an unquestioned adoption of capitalist ideals of progress and growth, that drives increases in consumption and production unproblematically alongside calls for an ecologically sound and socially equitable world. Mignolo (Citation2002, Citation2018) uses the concept “geopolitics of knowledge” to unveil the location of knowledge (and abstract universals) and to make visible the terms (the principles and assumptions) of knowledge which cannot be separated from politics and economy. Consequently, controlling knowledge is necessary for controlling the four interrelated domains, and ultimately “managing the people who are shaped by the domains” (Mignolo, Citation2018, p. 188).

Seeking to problematize “the location of knowledge”, Canaparo (Citation2009) uses the term “geo-epistemology” to describe how knowledge is always localized and related to an idea of culture (p. 22). He also argues for what he calls “spatial thinking”, that is to say we cannot critically think without standing in a particular location in biosphere terms. Spatial (local) thinking thus concerns the comprehension of knowledge (and its limits and conditions), and the idea of space has a direct relation to the geometrical meaning of the environment – “the understanding of the local condition of knowledge cannot be separated from the local construction of the space (environment) itself” (p. 71). The notion of geo-epistemology as a location of knowledge and direction of thinking has been theorized within the field of environmental education research in attempts to reconnect humans and non-human nature in aesthetic education (Iared, Torres de Oliveira, & Payne, Citation2016) and in stressing the need for localized knowledge to inform ecologically sustainable development policy makings and implementations (cf. Lotz-Sisitka, Citation2016; Payne, Citation2016). Epistemology is unquestionably an important topic in ESE, and we believe that it is important to connect these discussions around knowledge more clearly to coloniality and, like Mignolo, treat knowledge as directly tied to the cmp.

Decoloniality and posthuman approaches - Shared ground and/or distinctions

How then do (postcolonial and) decolonial approaches in EER deal more precisely and assertively with allegedly new theory/intellectual resources (such as posthumanism) and identified Mindmap concepts driving the SI rationale? Do we see some shared ground and/or distinctions? The Introduction to this SI draws broad attention to the ways “post” theoretical approaches such as posthumanism gain “authority”, and what this may potentially assume or conclude about human/non-human in EER and its practices. In considering connections among decolonial and posthuman approaches, we address the extent to which and how posthumanism adds to and/or shares with decolonial approaches, and what points of convergence or difference imply for curriculum/ESE pedagogies.

Posthuman approaches work to disrupt assumptions that humans are the only species capable of producing knowledge and with the capacity to know, and thus they represent a reaction against anthropocentrism and expansion of moral concern beyond the human species (Cudworth & Hobden, Citation2015; Ulmer, Citation2017; Zembylas, Citation2018). Zembylas (Citation2018) and Mignolo (Citation2018) argue that posthuman and decolonial approaches, in some senses and to a certain extent, overlap in that both these trajectories share the critique of modernity, and open up spaces for listening to the voices of the marginalized/silenced. Both seek to decenter the human species and think beyond Eurocentric binaries (human/non-human, nature/culture) deeply rooted in anthropocentrism.

As noted in the SI Introduction, James (Citation2017) emphasizes “decentering” and challenges assumptions of posthuman versions of the human. In earlier work, James, Magee, Scerri, and Steger (Citation2015) explain the Circles of Social Life approach and suggest that social life should be understood holistically across four interrelated domains: ecology, economics, politics and culture. Each of the domains are always located in relation both to each other and to nature (p. 43). With this approach James (Citation2017) decenters the human without returning to fluid boundaries between or collapsing the social and the natural, and displaces economics by treating economics as one of four overlapping social domains and not as the master domain separated from its social foundation or “the raison d’être of global change” (James et al., Citation2015, p. 28). James’ approach is an alternative to the mainstreaming of new posthuman theory, and a persuasive critique of posthuman thinking. Still, we miss the decentering of the privilege of Eurocentrism and how decolonial thinkers problematize the origins of modern concepts like man, human, nature: when, why, who, and what for? (Mignolo, Citation2018, p. 171).

Taking a stance to decenter the human without promoting a non-anthropocentric position, Lindgren and Öhman (Citation2019) seek to combine ethics, politics, and posthumanist ontology in their argumentation for a pluralistic approach to ESE, described as an education that criticizes consensus thinking and normativity and, instead, encourages “an education of participation that is open to conflicting views” (p. 1). From a pluralist point of view the authors raise an important argument that humanism has “values that we may not want to abandon”, and “putting human interests aside would therefore leave us with a useless ethics that would be both insufficient and irrelevant for political decision-making and potential environmental concern” (p. 2).

According to Mignolo (Citation2018), (enlightenment) universalist humanism, or the universal(ized) model of human anchored in the rhetoric of modernity, is under attack from two perspectives: “One is the postmodern conceptualization of the posthuman, and the endowment of a new history: the anthropocene, the era of the anthropos. The other arises from decolonial questioning” (p. 170). One could argue that Lindgren and Öhman (Citation2019) pluralist approach and their argumentation for the development of a “more-than-human” ESE practice offers a third perspective, as is argued by Carvalho, Steil, and Gonzaga (Citation2020), in this special issue, after critiquing the global North2’s insertion of the prefix “post” into the human/ism.

What tends to be forgotten in discussions about humanism in educational practice (cf. Sund & Öhman, Citation2014) and what decolonial scholars interrogate are the limits of ideas of the universal human. Through a decoloniality prism, the universal human (Man/Human) is embedded in the cmp and is the reference point in every domain. Coloniality mapped not only the land, but also the people which lead to classification and ranking of people (for example the separation between humanitas and anthropos3). Mignolo (Citation2018) significantly qualifies the universal human, noting the idea of human and humanity was built upon a logic disguised as an existing entity: “Human was a fictional noun pretending to be its ontological representation” (p. 155). Further, we argue it is important to distinguish between pluralism and pluriversality, the latter explicitly interested in delinking from the cmp. Presenting humanism or posthumanism without recognizing the origins and limitations of modernity may mean a pluralist approach that allows for a categorization of ideas or worldviews and a description of a static relationship and conflict between worldviews that fails to decenter modernity and delink from the cmp. The pluralist criticism of consensus thinking and normativity could be what Mignolo (Citation2018, p. 151) calls a “Eurocentric critic of Eurocentrism (e.g., demodernity), which is necessary but highly insufficient”. Rather, he argues, “what is essential at this point is the non-Eurocentric critic of Eurocentrism; which is decoloniality in its planetary diversity of local histories that have been disrupted by North Atlantic global expansions” (Ibid).

To expand on this point, Mignolo (Citation2018) connects humanism – a set of discourses enunciated by agents identifying themselves as human, projecting self-fashioning onto a universal scale – with posthumanism, which he argues is another examples of “the West’s particular ontology of history continu[ing] to assert its universality” (p. 119). He concludes the posthuman generally amounts to “a Eurocentric critique of European humanism” (Mignolo, Citation2018, p. 171), adding “conceptualizations of posthuman and posthumanism carries the weight of its regional racial and sexual classifications and ranking” (Mignolo, Citation2018, p. 155). Thus, decoloniality as praxis requires a “critique of both the concepts of human and posthuman” (p. 171 – emphasis added).

Referring to Sylvia Wynter’s work (2003, 2007), and appreciating her “confrontation of Western hegemony (overrepresentation would be Wynter’s term),” Mignolo (Citation2018) points out that the modes of being human can be traced through époques or ruptures in Western history (p. 171). Wynter (Citation2007) argues that a first form of man, the secularized and rational homo politicus (Man1), occurred during the Renaissance, while a second form, the Liberal homo economicus (Man2), coincided with the era of Enlightenment and the rise of capitalism. Mignolo (Citation2018) does not regard the concept of the posthuman as a way to think of Man/Human beyond colonial modernity, but rather, adding to Wynter’s (Citation2007) genealogy, articulates it as an extension to Man3: “Human, Man/Human, and Posthuman are three moments in the history of the cmp attempting to maintain control of epistemic meaning in the sphere of culture, parallel to the control of meaning and power in the sphere of economics and politics” (p. 172). Hence, adding a prefix – posthuman, neither solves the ways domains of the cmp work together nor how the hierarchy of humanness is maintained. One could argue that, by not solving the “problems” it addresses “critically” [in theory], it actually contributes to its reproduction/perpetuation – a “dynamic conservatism”, where [the illusion of] change contributes to non-change.

In this line of reasoning, humanity or being human, is an invention rooting back to the Renaissance. Mignolo (Citation2018) asserted that two main pillars (racism and sexism) hierarchically classified people. However, “there is one more facet in the procedural constitution of the human: the invention of nature and the degradation of life” (p. 158). In the cmp, nature lies between the domains/spheres of economics and politics and was invented to separate human from all living organisms on the planet. From decolonial approaches, it has accordingly been argued that the opposition between nature and culture is not universal, but Eurocentric.

Although posthumanist perspectives offer relevant tools to identify and critique the nature/culture and human/non-human dualisms, there are concerns that approaches to posthumanism may be tightly bound in and by Eurocentric epistemologies (Sundberg, Citation2014). Further, as Zembylas (Citation2018) notes, decentering the human may not necessarily make transparent global power relations nor delink from colonial history and oppression. Sundberg (Citation2014) argued that in the discipline of geography posthumanism “remains within the orbit of Eurocentered epistemologies and ontologies” because it “refers to a foundational ontological split between nature and culture as if it is universal” (p. 35, emphasis in original text). For example, Sundberg asserts, posthumanist theories are silent about location and silent about Indigenous epistemes (Ibid). Sundberg (Citation2014) thus reinforces what Mignolo (Citation2009, Citation2011a, Citation2018) terms “geo-historical and bio-graphic loci of enunciation” to address that knowledge comes from somewhere and is, therefore, “located by and through the making and transformation of the colonial matrix of power” (Mignolo, Citation2009, p. 2).

Braidotti’s (Citation2013) work offers an interesting convergence. The idea that advanced capitalism and its values create a shared form of unity of a negative kind, a “pan-humanity” through our collective vulnerability, described by Braidotti (Citation2013) as “a global sense of inter-connection between the human and the non-human environment in the face of common threats” (p. 50) has been engaged from decolonial perspectives (cf. Rekret, Citation2016; Zembylas, Citation2018). Zembylas (Citation2018) raises the possibility that posthumanism’s rejection of Eurocentric forms of humanism and the above described pan-humanity “will not necessarily result in greater humility for humans’ interdependence with other living and non-living beings nor will it fight the various manifestations of structural violence, colonialism and racism” (p. 263). From this perspective, some authors drawing on decolonial scholarship argue that posthumanism is “another false universal brought about by the post-Enlightenment subject” (Atanasoski & Vora, Citation2015, p. 11; cf. Mignolo, Citation2018 ). Mignolo (Citation2018) notes that the universality of posthuman “presupposes that all on the planet is posthuman when, in reality, modernity has reduced the majority of the population to quasi-human” (Mignolo, Citation2018, p. 119). From this, we believe we should engage with and consider posthumanism as an important nuance in the historicity of the construction of humans offering an important reflexive space to conceptualize climate change. When we engage with posthumanist approaches in considering a praxis of delinking for teaching global issues it must be from coloniality stance and with decoloniality as analytical frame.

Discussions regarding the Anthropocene have involved converging critiques as Stein (Citation2019)—drawing on Davis and Todd (Citation2017), Di Chiro (Citation2014) and Karera (Citation2019)—points out. There are many critiques of the term Anthropocene, with alternatives like Capitalocene offered so as to differentiate the affluent North from various injustices, ecological and/or social and/or cultural (Payne, Citation2020). Qualifying the position that humanity has been the primary force of global environmental change, critique centering decolonial analyses highlights that a particular subset of humanity has had the largest responsibility. Stein (Citation2019) points out the irony that while Indigenous and racialized people have been excluded from being human or as Mignolo (Citation2018) puts it, are “quasi-human”, within the cmp, the framing of the concept of the Anthropocene relies on a universal human figure that erases these differences. Stein (Citation2019) thus argues for diagnosing the interrelated colonial structures of genocide and ecocide as root causes of climate change (citing Whyte, Citation2018).

Decoloniality as praxis: Reorienting and re-curricularizing

In our empirical studies (Pashby & Sund, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Sund & Pashby, Citation2019), we engage this level of theoretical critique with classroom exemplars grounded in practice to examine reconstructions of curricula and pedagogy from a decolonial perspective to develop a praxis of delinking. What do these tensions within the theoretical literature imply for reimagining pedagogies in secondary education? To what extent do these wider scholarly discussions relate to and assist in analysis of examples of classroom practice, and what insights do these examples provide to speak back to the theoretical discussions?

As an answer to the questions raised in the Introduction of the SI, how (new ∼ not new) movement might pressure and reframe social science (education) to open up space for decentering and raise “new” questions, we think in terms of decolonial pedagogies. Walsh (Citation2018) describes very aptly decolonial pedagogies “as methodologies and processes of struggle, practice, and praxis that are embodied and situated, that confront, that push historical, political, ethical and strategic learnings, and that oblige epistemic, political, ethical, strategic ruptures and displacements” (p. 48–49, emphasis added). Centering decoloniality as a pedagogical imperative in (environmental and citizenship) educational research can help us make visible how processes of production and consumption today remain entrenched in systems of oppression tied to unequal colonial systems of power. This gesture to praxis is an important contribution that not only aims to delink from Eurocentric thought and the epistemological foundations of colonialism, but also encourage venues of re-existence, understood as implementing “a strategy of questioning and making visible the practices of racialization, exclusion and marginalization” and confront “the bio-politic that controls, dominates, and commodifies subjects and nature” (Ibid, p. 18). Mignolo (Citation2018) explains that re-existence follows up on delinking: “re-existence means the sustained effort to reorient our human communal praxis of living” (p. 106). Thus, a re-existence-based struggle and strategies of (political, economic, epistemic, etc.) interventions will assist in recognizing and pushing against the cmp by centering on considerations of how decoloniality delinks from this matrix and constructing paths and praxis toward an otherwise of thinking and doing.

As educators and researchers in the areas of critical GCE and ESE and as white women from global North contexts ourselves, we recognize both the importance of, and the difficulties faced in, making decoloniality intelligible in both theory and pedagogical practice. A complex and critical approach to education takes account of power relations, situatedness, and complexities and, at the same time, provokes shifts in our relationships with (and geopolitics of) knowledge, others, and the world. Obviously, there is more to a praxical framing than just implementing the official curriculum. And, as we consider decoloniality through delinking as a praxis possibility, we must acknowledge the complex situations of how teachers make sense of their own approaches to teaching about sustainable development issues, and to consider these as entry points or spaces of foreclosure to ethical global issues pedagogy rooted in decoloniality. A decoloniality intervention urges considerations of the “methodological-pedagogical-praxistical stance” (Walsh, Citation2018, p. 20). We see this as a potential reframing of curriculum and resources that support educators in the global North to think and act in ways that work to dismantle the structures of privilege and opens up possibilities for a praxis that interrupts and cracks the cmp. It is extremely difficult when education systems themselves are so entangled in the cmp; and yet, pedagogy offers possibilities that must be taken up. We also find Baszile’s (Citation2019) challenges of “rewriting/re-curricularizing” knowledge processes useful, arguing for “presenting the field from the perspective of those whose lives have often been terrorized and/or invisibilized in and through the dominant processes of knowledge production, evaluation and legitimation” (p. 9). In our work, we start with the idea that it is important to discuss with teachers the extent to which they acknowledge dominant knowledge systems and existing power relations in their framing of and pedagogical treatment of global issues. In the context of teaching in northern Europe, the idea of re-curricularizing can be understood in such a way that it provides teachers the space to consciously reassess their own knowledge embedded in their teaching and bring about new approaches to and pluralizing of bodies of knowledge within their teaching, even if it begins by acknowledging the knowledges that are not present or that do not seem available. It is, essentially, a pedagogy of delinking in this context. We argue that from there, it may be possible to consider wider decolonial approaches, including indigenization, an area we feel requires much further developing in the context of northern Europe. In our work, and as a start in this direction, we focus on the extent to which teachers delink from modern/colonial narratives.

Our theorizing from practice, or “practices theory” is supported by results from a small-scale participatory research project that engaged secondary and upper secondary teachers in England, Finland, and Sweden with a reflective tool4 presented in workshops in all three contexts that enables critical interventions in the contexts of educational initiatives that aim to address global justice and enact social change (Andreotti, Citation2012). Teachers attending the workshops articulated the significance of taking a more critical and complex approach to teaching about global issues and being aware of mainstream approaches to development and aid. Some teachers connected their work directly with ethnocentrism and stressed the importance of revisiting the curriculum and the need to take a more in-depth look in the current teaching material which they noted tend to present the problems through a Western/Northern Europe mindset (Pashby & Sund, Citation2019a, Citation2019b). However, teachers in that study were also focused on providing consolidations and solutions to global issues and this constrained their ability to deeply delink global issues (Pashby & Sund, Citation2019b).

In another study, we examined how Swedish upper secondary teachers take up ethical global issues in their classrooms through classroom observations and interviews with teachers and students. In the following, we use an example from a classroom observation to explore how we are building theory from practical examples and to demonstrate what engaging decolonial options in class might look like. The focus of this example is on and includes a student-teacher conversation. We believe it is helpful to jump off of examples from practice. At the same time, this work is based on a limited number of empirical examples and builds from previous empirical studies (Pashby & Sund, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Sund & Pashby, Citation2019). Thus, we are not using the examples from empirical studies here to claim generalized findings but rather to consider the extent to which theorizing in this area speaks to and from day-to-day examples of practice in secondary schools. This is a similar process/“outcome” to the SI on ecopedagogy as/in scapes (Payne, Citation2018a, Citation2018b) where seven researchers from different geopolitical locations of knowledge production theorized and combined 30-odd studies of ecopedagogy. Their contribution can be seen as part of a “new” metamethodology of SIs being pioneered praxically in JEE, and an ongoing narrative within EER discourse/praxis.

Delinking global issues in northern Europe classrooms

The crux of our approach to praxis is that analytical delinking is pedagogical in addition to being theoretical. In teachers’ praxis we understand delinking as reorienting strategies of (political, economic, epistemic, etc.) organization toward confronting the cmp and to re-curricularizing knowledge processes. In essence, delinking as decolonial praxis aims to make dominant knowledge systems and existing power relations visible in teachers’ framing of and pedagogical treatment of global issues.

An empirical example

Students in Science teacher Carla’s classroom (grade 11) in a small city in Sweden examined solid domestic waste and its increase as a result of growing human populations and consumption. Toward the end of the class and with reference to a quote from Greenpeace in their textbook, the teacher brought up the issue of the growing electronic waste problem:

The Greenpeace quote presented to the class the problem of electronic waste whereby the burden of the toxicity of wastes from the global North falls mainly onto developing countries. But, there was no problematization as to why e-waste “historically” ends up “dumped” in the global South.

The teacher tried to engage students in an ethical discussion, inviting students to reflect on why the handling and recycling of e-waste is not being done in the global North and the question of responsibility related to that (“Why does it not end up here?”, “How come we don’t take care of this?”). Still, the conversation focused on the dumping of e-waste in the global South as a technical issues (strategies of managing e-waste), an epistemological issue (a lack of knowledge of e-waste recycling in the global South), an environmental issue (e-waste harms the environment and people if not properly processed, an economic issue (the cost of responsible e-waste treatment is considered too expensive), and, finally, it socially is a judicial issue as there is, allegedly, no law that makes it illegal to dump hazardous waste in the global South. (Cf. the Circles of Social Life approach that recognizes both ontological difference and the interconnectedness of social-natural life, and the decentering logic/practice James, [Citation2017] promotes in contrast to a posthumanist approach). Since this is a Science class, it is understandable that the teacher and the students applied scientific knowledge and discussed environmental effects and technical solutions to e-waste problems. A posthuman perspective and/or James’ (2017) Circles approach could also point out how there is a strong differentiation between humans and the ecosystem. This could also be included as a way to decenter discussions; and yet, this, we argue, must begin with a contextualization of the issue as tied to the cmp if discussions of posthumanism are to delink and re-curricularize. At the end of the discussion the teacher confirms that it comes down to knowledge, convenience and cost to properly dispose of electronics.

Conclusion

The teacher’s attempt to actively encourage students to discuss complex moral and political issues and open up space for these conversations is characteristic/specific to a Nordic pluralistic and democratic tradition in the context of ESE (Öhman & Östman, Citation2019). Nevertheless, and as exemplified here and supported by other examples (see Pashby & Sund, Citation2019b), teachers can unintentionally get caught up in consolidating a humanistic and uncomplicated analysis rather than challenging unfair life-chances around the world, thus reproducing modern narratives. Based on biopolitical theory, Hellberg and Knutsson (Citation2018) argue that there is a risk that ESD practices and interventions, despite good intentions, forms part of a global biopolitical regime that actually helps to sustain and consolidate the lifestyle divide “that separates wealthy mass consumers from poor subsistence level populations” (p. 103). It is important to take these authors’ concerns seriously, and in our argument, a decolonial lens can help us illuminate some important features that have gone largely unnoticed in previous research.

From a decoloniality possibilities perspective and for the context of teaching about global issues in northern Europe, we stress the importance of lifting the ethical perspective in a classroom discussion. The challenge of teaching in the example is to shape an ethical response to the e-waste problem. The students need to be offered the possibility to interpret and morally investigate the option articulated by modernity/coloniality and the options and ruptures that decoloniality offers. To encourage students to view reflexivity as a core requirement of their ethical practice, a teacher could make visible the practices of exclusion and marginalization, perhaps by raising moral questions: “Shouldn’t we in the global North take care of our e-waste? And why would we frame this as an issue for others, whose knowledge is perceived as better and what knowledges do we lack in approaching this issue”. There are also good reasons why a teacher might not do this given the complex ways teachers are or are not prepared to engage in ethical global issues pedagogy (see Sund & Pashby, Citation2019), which points to the need for further empirical research in this area to recognize the limitations to delinking due to institutional (policy, curriculum, pedagogical traditions), personal, and cultural (societal, school-based, classroom-based) reasons and constraints.

Consequently, we argue that it is essential that the analytic of coloniality is taken-up through addressing the continued role of colonialism in today’s global problems and that teachers explicitly direct attention to historical patterns (Andreotti, Citation2012; Andreotti et al., Citation2018) of oppression and their contributions to global issues. If we return to what we mentioned initially about the challenge “to think and learn from where we are located” and apply that to pedagogical praxis – how is the question of promoting ethical global issues pedagogy contextualized within where we are located and how can it be transferred, but not generalized, as generative “new” strategies of action? As researchers and educators, we need to engage deeply with and confront historical patterns in concrete pedagogical practices in order to interrupt our own epistemic, political, ethical, and strategic place and categories. These ruptures can help us unveil “neutral universals” and recognize the mechanisms that privilege certain perspectives, rationales, sites. Decolonial critique opens up for critical engagements and the use of pedagogical delinking can be an entry point into working with classrooms in northern Europe where we argue it is highly required and also very context specific. There may also be possibilities for this type of delinking pedagogy in other global North and global South contexts, yet we focus here on northern European classrooms where there are curricular routes to global issues that risk reinscribing colonial power relations (see Bryan, Clarke, & Drudy, Citation2009; Niens & Reilly, Citation2012; Pashby & Sund, Citation2019a; Sund, Citation2016).

As we mentioned at the beginning, as two White women with significant socio-economic and educational privilege, we center our work on the challenge of how to think and learn from where we are located and look for innovations and ruptures that outline new strategies of action. Our theoretical work in this paper, and its empirical support with an example of how we build our theorizing from practice, raises a lot of questions and challenges. We cannot claim to decolonize classrooms, and acknowledge this may not be a real possibility given both education’s and research’s complicity in the cmp. However, in light of the important possibilities being promoted through a turn to posthumanist approaches in ESE to take seriously humans’ complicity in the significant damage to ecosystems and to put ethical relations to more than human beings into question, we argue it is just as necessary to offer a delinking approach to pedagogy alongside posthumanist approaches thereby taking up the critique that posthumanism is an ethnocentric critique of ethnocentrism. In the northern Europe contexts in which we work with teachers, we argue it is of the utmost importance that we consider pluriversality and take a strong stance to recognize global problems as epistemological injustices.

Specifically, as a non-exhaustive but focused way forward for research and practice, we offer five key directions for developing a pedagogical praxis of delinking:

Explore multiple and multiply positioned perspectives that reflect different worldviews and narratives and explore and engage with complexities and contractions within and between perspectives.

“Denaturalize” dominant one-sided narratives (on progress, development, consumption, etc.), and recognize how these concepts are socially and politically constituted.

Acknowledge that what it means to be human is entrenched in the cmp, and also who was/is included in the human concept (nature as outside of human in cmp).

Historicize/contextualize how contemporary views (on progress, development, consumption etc.) in the global North have gained prominence and why other views have been pushed to the margins.

Recognize the lingering impact of colonization persistence of unequal power relations and how these are directly related to today’s pressing issues, including climate change and environmental degradation.

We are centered on raising coloniality as a central condition of today’s global issues and seek to open spaces to acknowledge coloniality as a key element of ethical global issues pedagogy. It is quite obvious to us that in northern Europe, there is a need to respond pedagogically – the question is how? We think one way is to at the very least raise coloniality explicitly – to consider the grand design of development education and ESE in Europe and open some ruptures. We don’t claim this will change everything, but it is most definitely imperative worth pursuing.

Notes

1 Foucault (1990/1976) used the term biopolitics to refer to state technologies and strategies of population control to administer and regulate social life: “to ensure, sustain, and multiply life, to put this life in order” (p. 138). As noted by Mignolo, (Citation2011a, Citation2018), Foucault focused his attention to a European context, but such technologies were also applied to the colonies. Mignolo, (Citation2011a) argues that “bio-politics is half of the story. Coloniality is the missing half, the darker side of modernity and bio-politics, that decolonial arguments unveil” (p. 140).

2 The concept of global North indicates our location in an area of epistemological, economic, and political privilege within the current geopolitical configuration and our complicity within the CMP that has contributed to establishing and maintaining this distinction. Similarly, global South has been contested and should not be understood as merely geographical classification of the world. Acknowledging its imperfect nature and potential for re-inscribing a binary we are seeking to challenge, we use it here it to reference epistemic and political marginalization and a challenge to the dominance of Western ways of perceiving the world as discussed by, for example, Levander and Mignolo (2011) and Mignolo, (Citation2011a). According to Kloß (2017) the global South “is not an entity that exists per se but has to be understood as something that is created, imagined, invented, maintained, and recreated by the ever-changing and never fixed status positions of social actors and institutions” (p. 1).

3 Mignolo (Citation2011a) explains that “since humanitas is defined through the epistemic privilege of hegemonic knowledge, anthropos was stated as the difference – more specifically, the epistemic colonial difference. In other words, the idea was that humans and humanity were all ‘human beings’ minus the anthropos” (p. 85).

4 The HEADSUP tool helps learners and educators to identify seven problematic patterns of representations and engagements commonly found in narratives presented in educational approaches to global issues, particularly North-South engagements with local populations who are structurally marginalized (Andreotti et al., 2018, p. 15).

References

- Andreotti, V. (2011). (Towards) Decoloniality and diversality in global citizenship education. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 9(3-4), 381–397. doi:10.1080/14767724.2011.605323

- Andreotti, V. (2012). Editor’s preface: HEADS UP. Critical Literacy: Theories and Practices, 6(1), 1–3.

- Andreotti, V. (2014). Critical literacy: Theories and practices in development education. Policy & Practice A Development Education Review, 19, 12–32.

- Andreotti, V., & Souza, L. M. T. (2012). Postcolonial perspectives on global citizenship education. New York: Routledge.

- Andreotti, V., Stein, S., Sutherland, A., Pashby, K., Susa, R., & Amsler, S. (2018). Mobilising different conversations about global justice in education: Toward alternative futures in uncertain times. Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, 26, 9–41.

- Atanasoski, N., & Vora, K. (2015). Surrogate humanity: Posthuman networks and the (racialized) obsolescence of labor. Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, 1(1), 1–40. doi:10.28968/cftt.v1i1.28809

- Baszile, D. T. (2019). Rewriting/recurricularlizing as a matter of life and death: The coloniality of academic writing and the challenge of black mattering therein. Curriculum Inquiry, 49(1), 7–24. doi:10.1080/03626784.2018.1546100

- Blenkinsop, S., Affifi, R., Piersol, L., & Sitka-Sage, M. (2017). Shut-Up and listen: Implications and possibilities of Albert Memmi’s characteristics of colonization upon the “Natural World”. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 36(3), 349–365. doi:10.1007/s11217-016-9557-9

- Braidotti, R. (2013). The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity.

- Bryan, A., Clarke, M., & Drudy, S. (2009). Social justice education in initial teacher education: A cross border perspective, A report for the standing conference on teacher education north and south (SCoTENS). Retrieved from http://scotens.org/docs/2009-Social%20Justice%20Education%20in%20Initial%20Teacher%20Education.pdf.

- Calderon, D. (2014). Uncovering settler grammar in curriculum. Educational Studies, 50(4), 313–338. doi:10.1080/00131946.2014.926904

- Canaparo, C. (2009). Geo-epistemology: Latin America and the location of knowledge. Oxford, UK: Peter Lang.

- Carvalho, I., Steil, C., & Gonzaga, F. (2020). Learning from a more-than-human perspective: Plants as teachers. The Journal of Environmental Education, 51(2).

- Cudworth, E., & Hobden, S. (2015). Liberation for straw dogs? Old materialism, new materialism, and the challenge of an emancipatory posthumanism. Globalizations, 12(1), 134–148. doi:10.1080/14747731.2014.971634

- Davis, H., & Todd, Z. (2017). On the importance of a date, or decolonizing the Anthropocene. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, 16(4), 761–780.

- Di Chiro, G. (2014). Response: Reengaging environmental education in the ‘Anthropocene. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 30(1), 17–17. doi:10.1017/aee.2014.18

- Foucault, M. (1990/1976). The history of sexuality: Volume 1, an introduction. New York, NY: Vintage Books. doi:10.1086/ahr/84.4.1020

- Giroux, H. (1981). Ideology, culture and the process of schooling. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Hellberg, S., & Knutsson, B. (2018). Sustaining the life-chance divide? Education for sustainable development and the global biopolitical regime. Critical Studies in Education, 59(1), 93–107. doi:10.1080/17508487.2016.1176064

- Iared, V. G., Torres de Oliveira, H., & Payne, P. G. (2016). The aesthetic experience of nature and hermeneutic phenomenology. The Journal of Environmental Education, 47(3), 191–201. doi:10.1080/00958964.2015.1063472

- James, P. (2017). Alternative paradigms for sustainability: Decentring the human without being posthuman. In K. Malone, S. Truong, & T. Gray (Eds.), Reimagining sustainability in precarious times (pp. 29–44). Singapore: Springer.

- James, P., Magee, L., Scerri, A., & Steger, M. (2015). Urban sustainability in theory and practice: Circles of sustainability. London: Routledge.

- Karera, A. (2019). Blackness and the pitfalls of Anthropocene ethics. Critical Philosophy of Race, 7(1), 32–56. doi:10.5325/critphilrace.7.1.0032

- Kayira, J. (2015). (Re)creating spaces for uMunthu: Postcolonial theory and environmental education in southern. Environmental Education Research, 21(1), 106–128. doi:10.1080/13504622.2013.860428

- Kloß, S. T. (2017). The Global South as subversive practice: Challenges and potentials of a heuristic concept. The Global South, 11(2), 1–17.

- Le Grange, L. (2007). Integrating western and indigenous knowledge systems: The basis for effective science Education in South Africa?International Review of Education, 53(5-6), 577–591. doi:10.1007/s11159-007-9056-x

- Levander, C., & Mignolo, W. D. (2011). Introduction: The global South and world dis/order. The Global South, 5(1), 1–11. doi:10.2979/globalsouth.5.1.1

- Lindgren, N., & Öhman, J. (2019). A posthuman approach to human-animal relationships: Advocating critical pluralism. Environmental Education Research, 25(8), 1200–1215. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1450848

- Lotz-Sisitka, H. (2016). Reviewing strategies in/for ESD policy engagement: Agency reclaimed. The Journal of Environmental Education, 47(2), 91–103. doi:10.1080/00958964.2015.1113915

- Ma Rhea, Z. (2015). Leading and managing indigenous education in the postcolonial world. London, England: Routledge.

- Ma Rhea, Z. (2018). Towards an Indigenist, Gaian pedagogy of food: Deimperializing foodscapes in the classroom. The Journal of Environmental Education, 49 (2), 103–116. doi:10.1080/00958964.2017.1417220

- Martin, F. (2011). Global ethics, sustainability and partnership. In G. Butt (Ed.), Geography, education and the future (pp. 206–224). London: Continuum.

- Matthews, J. (2011). Hybrid pedagogies for sustainability education. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 33(3), 260–277. doi:10.1080/10714413.2011.585288

- Mignolo, W. D. (2002). The geopolitics of knowledge and the colonial difference. South Atlantic Quarterly, 101(1), 57–96. doi:10.1215/00382876-101-1-57

- Mignolo, W. D. (2009). Epistemic disobedience, independent thought and decolonial freedom. Theory, Culture & Society, 26(7–8), 159–−181. doi:10.1177/0263276409349275

- Mignolo, W. D. (2011a). The darker side of western modernity. Global futures, decolonial options. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Mignolo, W. D. (2011b). Epistemic disobedience and the decolonial option: A manifesto. Transmodernity: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World, 1(2), 44–66.

- Mignolo, W. D. (2018). The Decolonial option. In W. D. Mignolo & C. E. Walsh (Eds.), On Decolonialty. Concepts, Analytics, Praxis (pp. 105–244). Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Niens, U., & Reilly, J. (2012). Education for global citizenship in a divided society? Young people’s views and experiences. Comparative Education, 48(1), 103–118. doi:10.1080/03050068.2011.637766

- Noxolo, P. (2017). Introduction: Decolonising geographical knowledge in a colonised and re-colonising postcolonial world. Area, 49(3), 317–319. doi:10.1111/area.12370

- Öhman, J., & Östman, L. (2019). Different teaching traditions in environmental and sustainability education. In K. Van Poeck, L. Östman & J. Öhman (Eds.), Sustainable development teaching. Ethical and political challenges (pp. 70–82). Routledge Studies in Sustainability. London & NY: Routledge.

- Pashby, K. (2012). Questions for global citizenship education in the context of the ‘new imperialism. In V. de Oliveira Andreotti and L. M. T, M. de Souza (Eds.), Postcolonial perspectives on global citizenship education (pp. 9–26). New York: Routledge.

- Pashby, K., & Sund, L. (2019a). Bridging 4.7 with Secondary Teachers: Engaging critical scholarship in Education for Sustainable Development and Global Citizenship. In Philip Bamber (Ed.), Teacher education for sustainable development and global citizenship: Critical perspectives on values, curriculum and assessment (pp. 99–112NY and London: Routledge.

- Pashby, K., & Sund, L. (2019b). Critical GCE in the era of SDG 4.7: Discussing HEADSUP with secondary teachers in England, Finland, and Sweden. In Douglas Bourn (Ed.), Bloomsbury handbook for global education and learning (pp. 314–326). UK: Bloomsbury.

- Patel, L. (2014). Countering coloniality in educational research: From ownership to answerability. Educational Studies, 50(4), 357–377.

- Payne, P. G. (2016). The politics of environmental education. Critical inquiry and education for sustainable development. The Journal of Environmental Education, 47(2), 69–76. doi:10.1080/00958964.2015.1127200

- Payne, P. G. (2018a). The framing of ecopedagogy as/in scapes: Methodology of the issue. The Journal of Environmental Education, 49(2), 71–87. doi:10.1080/00958964.2017.1417227

- Payne, P. G. (2018b). Ecopedagogy as/in scapes: Theorizing the issue, assemblages, and metamethodology. The Journal of Environmental Education, 49(2), 177–188. doi:10.1080/00958964.2017.1417228

- Payne, P. G. (2020). Amnesia of the moment” in environmental education. The Journal of Environmental Education, 51(02).

- Quijano, A. (2000). Coloniality of power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America. Nepentla: Views from the South, 1(3), 533–580.

- Quijano, A. (2007). Coloniality and modernity/rationality. Cultural Studies, 21(2-3), 168–178. doi:10.1080/09502380601164353

- Rekret, P. (2016). A critique of new materialism: Ethics and ontology. Subjectivity, 9(3), 225–245. doi:10.1057/s41286-016-0001-y

- Rodrigues, C., Payne, P., Le Grange, L., Carvalho, I. C. M., Steil, C. A., Lotz-Sistka, H., & Linde-Loubser, H. (2020). Introduction: “New theory, “post” North-South representations, practices. The Journal of Environmental Education, 51(2).

- Shiva, V. (1993). Monocultures of the mind. Trumpeter, 10(4), 2–11.

- Stein, S. (2019). The ethical and ecological limits of sustainability: A decolonial approach to climate change in higher education. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 1–15. doi:10.1017/aee.2019.17

- Sund, L. (2016). Facing global sustainability issues: Teachers’ experiences of their own practices in environmental and sustainability education. Environmental Education Research, 22(6), 788–805. doi:10.1080/13504622.2015.1110744

- Sund, L., & Öhman, J. (2014). On the need to repoliticise environmental and sustainability education: Rethinking the postpolitical consensus. Environmental Education Research, 20(5), 639–659. doi:10.1080/13504622.2013.833585

- Sund, L., & Pashby, K. (2019). Taking-up ethical global issues in the classroom. In K. Van Poeck, L. Östman, & J. Öhman (Eds.), Sustainable development teaching: Ethical and political challenges (pp. 204–212). London: Routledge Studies in Sustainability, Routledge Taylor Francis.

- Sundberg, J. (2014). Decolonizing posthumanist geographies. Cultural Geographies, 21(1), 33–47. doi:10.1177/1474474013486067

- Tuck, E., & McKenzie, M. (2015). Place in research theory, methodology, and methods. New York: Routledge.

- Tuck, E., McKenzie, M., & McCoy, K. (2014). Land education: Indigenous, post-colonial, and decolonizing perspectives on place and environmental education research. Environmental Education Research, 20(1), 1–23. doi:10.1080/13504622.2013.877708

- Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1 (1), 1–40.

- Ulmer, J. B. (2017). Posthumanism as research methodology: Inquiry in the Anthropocene. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(9), 832–848. doi:10.1080/09518398.2017.1336806

- Walsh, C. E. (2018). Decolonialty in/as praxis. In W. D. Mignolo & C. E. Walsh (Eds.), On decolonialty. Concepts, analytics, praxis (pp. 15–102). Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Walsh, C. E., & Mignolo, W. D. (2018). Introduction. In W. D. Mignolo & C. E. Walsh, (Eds.), On Decolonialty. Concepts, Analytics, Praxis (pp. 1–12). Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Whyte, K. P. (2018). Indigeneity in geoengineering discourses: Some considerations. Ethics, Policy & Environment, 21(3), 289–307. doi:10.1080/21550085.2018.1562529

- Wynter, S. (2003). Unsettling the coloniality of being/power/truth/freedom: Towards the human, after man, its overrepresentation – An argument. CR: The New Centennial Review, 3(3), 257–337. doi:10.1353/ncr.2004.0015

- Wynter, S. (2007). Human being as noun? Or being human as praxis? Towards the autopoietic turn/overturn: A manifesto. Retrieved from https://www.scribd.com/document/329082323/Human-Being-as-Noun-Or-Being-Human-as-Praxis-Towards-the-Autopoietic-Turn-Overturn-AManifesto#from_embed.

- Zembylas, M. (2018). The entanglement of decolonial and posthuman perspectives: Tensions and implications for curriculum and pedagogy in higher education. Parallax, 24(3), 254–267. doi:10.1080/13534645.2018.1496577