Abstract

In the field of school-based outdoor education, researchers claim that pre-service teachers should already be provided with basic knowledge, skills, and methods for teaching curriculum-based content outdoors in their initial schoolteacher training. The present review aims to summarize and structure the variety of topics in the literature regarding outdoor teaching in initial formal schoolteacher training. We analyzed the general characteristics of 46 empirical studies from different regions that investigate skills, content areas, and pedagogical strategies to prepare pre-service teachers from early childhood to secondary education for teaching outdoors. We used deductive-inductive content analysis to identify categories and emerging themes. We identified eight themes in the reviewed studies, of which we detail and discuss the four most frequently mentioned: collaboration, creativity, strategies for outdoor learning and sustainability. We discuss the implications for further research and for teacher training.

Introduction

Outdoor education is becoming increasingly important in formal school education. Schoolteachers teaching outdoors have reported positive impacts on their teaching practice, job satisfaction, health, and wellbeing (Marchant et al., Citation2019; Rickinson et al., Citation2004; Waite et al., Citation2016) as well as increased motivation, communication, and participation among students (Fägerstam, Citation2014). However, a repeatedly cited barrier to implementing outdoor teaching in school practice is insufficient experience and training during initial teacher training (Hanna, Citation1992; Kendall et al., Citation2006; Scott et al., Citation2015; Tal & Morag, Citation2009; Tuuling et al., Citation2019; van Dijk-Wesselius et al., Citation2020). In this context, the researchers point out that it is essential to familiarize pre-service teachers with outdoor curriculum-based teaching in their initial formal teacher training. In some Swedish universities, pre-service teachers study outdoor activities as part of their teacher training program (Niklasson & Sandberg, Citation2012). With the growing interest and relevance of outdoor education in teacher education, research studies on the topic are emerging all over the world.

We attempt to characterize and structure the diversity of topics in the research and clarify emerging themes to provide insights for future research and teacher educators. We briefly describe the distribution of general characteristics in the analyzed articles and quantify the themes that appear. Finally, we discuss the themes and shed light on the ways outdoor education can be positioned in initial formal teacher training.

An attempt to describe “outdoor teaching”

The understanding and practice of outdoor education is diverse and is influenced by the sociocultural contexts of the regions in which it is practiced (Rea & Waite, Citation2009). It has been difficult to define outdoor education or place it within a theoretical framework (Nicol, Citation2002, Citation2003) and practitioners still express confusion or uncertainty regarding its content and methodology (Torkos, Citation2018; Tuuling et al., Citation2019).

Reflections and attempts at outdoor learning modes are part of the history of education. Outdoor education has its roots in the early 20th century focus on welfare for learners (Sutherland & Legge, Citation2016). This was coupled with the use of outdoor learning experiences to enhance the development of learners’ personal skills. The teaching of natural sciences has also taken over outdoor teaching methods to the point of clearly addressing environmental issues in the second half of the 20th century. Outdoor teaching during excursions, camps, and classes in nature authentically addresses the issues of access to natural resources and the learner’s place in nature. The evolution of outdoor learning practices is thus part of a Western cultural history of opening school learning to consider the social and natural environment in which learning takes place.

Although outdoor education has developed different regional expressions and characterizations, the Danish “Udeskole” model (Bentsen & Jensen, Citation2012) has spread and there is evidence that other countries have adapted similar models and approaches (Larsson & Rönnlund, Citation2021; O’Brien & Murray, Citation2007; Remmen & Iversen, Citation2022; Skea & Fulford, Citation2021). Therefore, we would like to use the “Udeskole” model as a reference for the description of outdoor teaching in the context of the present review. It includes regular, compulsory educational activities outside the school buildings (Bentsen et al., Citation2009) in both natural and cultural settings, for example, forests, parks, local communities, factories, and farms (Jordet, Citation2007); use of the local environment when teaching specific curriculum subjects (Bentsen & Jensen, Citation2012); and planning to include cross-disciplinary and cross-curricular activities (Bentsen & Jensen, Citation2012).

Within this thematic framework, the present review focuses on studies that specifically used the outdoor environment as a learning setting for pre-service teachers.

Relevance of outdoor learning in initial formal schoolteacher training

Reports of positive impacts on school students’ general health and well-being, connection to nature, and engagement in learning with curriculum-based outdoor learning come from around the world including the UK (Marchant et al., Citation2019; Waite, Citation2020; Waite et al., Citation2016), Denmark (Bentsen et al., Citation2022; Bølling et al., Citation2018, Citation2019), Australia (Lloyd et al., Citation2018), Canada (Breunig et al., Citation2015) and the USA (Lieberman & Hoody, Citation1998). Interest in using nature and the environment for education is thus growing and has resulted, e.g., in the UK and the US, in strategies and policy developments to include outdoor learning (Department for Education and Skills (DfES),), Citation2003), learning for sustainability (Beames et al., Citation2011; Higgins et al., Citation2021), and environmental education (North American Association for Environmental Education (NAAEE), 2019). As early as the 1950s, it was pointed out that outdoor education required professional skills (Vinal, Citation1953) and was of particular importance in the initial training of teachers (Hammerman, Citation1957; Jaffe, Citation1955; Roossinck, Citation1957). The consensus for outdoor educators and researchers is that using the outdoors as a context and learning environment for school content promotes personal and academic development as well as environmental education (e.g., Bølling et al., Citation2019; Dale et al., Citation2020; Mann et al., Citation2021; Rickinson et al., Citation2004). However, teachers report various challenges and concerns, as well as low confidence in teaching outdoors in Australia (Dyment et al., Citation2014), Europe (Kubat, Citation2017; Torkos, Citation2018; Tuuling et al., Citation2019), the Middle East (Ihmeideh & Al-Qaryouti, Citation2016), the UK (Glackin, Citation2016; Marchant et al., Citation2019; Scott et al., Citation2015), the US (Torquati et al., Citation2017), and Singapore (Atencio & Tan, Citation2016). Indeed, the same studies reveal that pre-service teachers and schoolteachers feel unable or are unwilling to teach outdoors, due to inadequate education or training.

This article presents a review of studies published between 2000 and 2020, investigating outdoor learning and teaching (OLT) in initial formal schoolteacher training from early childhood to secondary education. In particular, this review includes articles from different regions of the world that address skills, content areas, and pedagogical strategies for OLT.

Methods

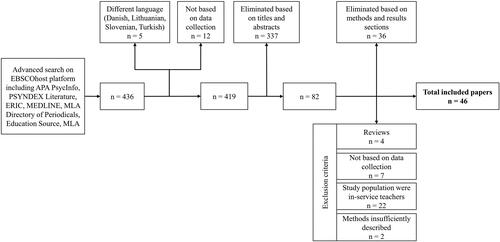

We followed a five-step process for a systematic literature review (Casey & Goodyear, Citation2015; Shulruf, Citation2010), which is an established method in social sciences (Petticrew & Roberts, Citation2006). It has been used in the context of outdoor education in relation to the education of teachers in physical education (Sutherland & Legge, Citation2016). The initial step was to (1) focus on the scope of the review with our research questions. Next, we planned the (2) search process with a protocol considering peer-reviewed, empirical research. We identified as much relevant literature as possible through a comprehensive search of academic databases using the main search term. Then, we (3) screened the articles and decided on the (4) inclusion and exclusion of studies based on methodological criteria (). Finally, we (5) synthesized the research findings through the process of qualitative content analysis, as explained in detail in the next paragraphs.

(1) Research questions

The review process was guided by two research questions:

RQ1 What are the general characteristics of the body of literature on OLT in initial formal schoolteacher training?

RQ2 What are emerging themes in the analyzed body of literature?

(2) Literature search process and protocol

The initial search included multiple and broad terms resulting in too many unspecific results but helped to identify the central search terms. The second literature search was conducted in December 2020 using the intuitive online research database package, EBSCOhost. The EBSCOhost platform included the following databases for the research: APA PsycInfo, PSYNDEX Literature with PSYNDEX Tests, ERIC, MEDLINE, MLA Directory of Periodicals, Education Source, and MLA International Bibliography with Full Text. This second advanced search was conducted using the specific search terms “outdoor education” and “teacher education,” which were combined with the “AND” function. No field option such as “all text” or “title” was selected. The search included the Boolean/Phrase mode with the option to apply equivalent subjects selected. The results were limited to peer reviewed articles and the search was limited to publications between the years 2000 and 2020 to include recent publications and consider research from several decades. The third author, who is a French native, also searched and screened articles using the same aforementioned criteria in three French databases, CAIRN, PASCAL, and FRANCIS. The search returned no articles meeting the search criteria. Therefore, no French articles were evaluated during the analysis.

(3) Article screenings and (4) criteria

At first, exclusion criteria were used to narrow down the number of relevant articles (). We excluded articles that were not published in English (due to the assumption that studies regarding international interest would be published in English), that were not based on primary data collection, or were unpublished or published in a noncommercial form, e.g., conference proceedings, reports, dissertations/theses. Moreover, articles that did not provide a comprehensive method section, e.g., missing information relating to the number of participants or course contents, interviewing, analysis of journals, etc., were excluded. We decided to include articles based on the following inclusion criteria: (a) a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods research design; (b) study participants were either pre-service teachers and/or teacher educators at teacher training colleges/universities; (c) the learning environment was an outdoor space or a combination of an indoor and outdoor experience, e.g., a museum visit and field experience; (d) data collection was in the context of initial formal schoolteacher training programs from early childhood to secondary level. We define teacher educators as lecturers or people who teach pre-service teachers at teacher training colleges.

(5) Synthesis of research findings

(a) Pre-analysis

Articles selected through the screening (Appendix, ) were pre-analyzed in terms of article information, context and theoretical background, research questions, research objectives, hypotheses, methodological information, results, implications for initial formal schoolteacher training, implications for research, instrument validation, general remarks, and comments on the study. We adapted the analysis grid from Ayotte-Beaudet et al. (Citation2017), who studied teaching and learning science in schools’ surroundings.

(b) Validity and reliability of instruments

Instrument validation was initially added to the grid as a characteristic for the research quality of the studies. This was intended to show how many studies based their data collection on valid and reliable instruments. In Creswell (Citation2014), validity is described as being able “to draw meaningful and useful inferences from scores to the instruments” (p. 160) and reliability is demonstrated if “items’ responses are consistent across constructs” and “scores are stable over time when the instrument was administered a second time” (p. 247). Both are methodological aspects designed to reduce threats to trustworthiness. Due to inconsistent information regarding instrument validation, it was not a focus in the review or a quality criterion for the selection of articles. Therefore, we include this information in the Methods rather than in the Results section.

Six quantitative research articles presented Cronbach’s alpha and one used the Guttman split-half coefficient to measure scale reliability; three articles did not specify the measures to determine reliability. One quantitative research article used a modified Delphi method (Dunn et al., Citation1999) for the process of survey development to strengthen instrument reliability. One quantitative research article referred to factor analysis and Pearson’s correlation for validity. One qualitative study described measures for internal validity (long-term interaction, deep-focus data collection, diversification, and expert review strategies) and intercoder reliability.

(c) Qualitative content analysis

Qualitative content analysis was performed on the extracted data, as described by Kuckartz (Citation2016, pp.181–182), using MAXQDA Plus 2020 software. The main characteristic of qualitative content analysis is working with categories (codes) and developing a category system or category frame. These categories are analysis tools, which build the substance of the research to develop a theory (Kuckartz, Citation2019, p. 183). If categories are derived from a theory, the literature, or research questions, they are developed in a concept-driven way (deductively). If categories are developed step-by-step from the text material in an open coding process, continuously organized and systematized into top-level codes and subcodes, they are developed in a data-driven manner (inductively). In the present review, we mixed the concept-driven and data-driven development of codes, starting with deductively formed codes and then subsequently engaging in inductive coding of data (Kuckartz, Citation2019, p. 185).

Through this process, emerging themes were allocated to three main categories (top-level codes): (1) attitudes and perceptions of pre-service teachers (PSTs) and/or teacher educators, (2) teaching strategies for preparing PSTs to teach outdoors, and (3) effects of outdoor teaching preparation on PSTs and the implications for teacher educators. Subcategories were developed within the main categories, e.g., (1) PSTs’ perceived obstacles/PSTs’ perceived competence to teach outdoors, (2) building partnerships with internal or external institutions, and (3) effects on PSTs’ species knowledge/effects on PSTs’ nature relatedness. In a second analysis step, eight recurrent themes within the main and subcategories were identified. The text material was re-sorted by the themes. Then, the extracted text material was screened again for each theme with the “Keyword-in-Context” function of MAXQDA. An example of the theme “cooperation” is: “The program was delivered in cooperation with NTBG staff on Kaua’i and centered on students’ (and my own) experiences in its three botanical gardens.” (Zandvliet, Citation2019, p. 146)

Results

RQ1 General characteristics of research

We first describe general characteristics from the pre-analysis of articles to give an overview of the field of research. The mixed methods and qualitative methodology were represented twice and three times, respectively, as often as the quantitative research methods (). More than 40% of the studies were conducted using between one and 50 participants, while only a few studies were conducted with more than 100 participants. Two studies were conducted using more than 500 participants. Participants in almost all studies were PSTs, while in a few studies they were teacher educators. All educational levels of initial formal schoolteacher training were represented, from early childhood to secondary education. Most studies were conducted in the area of primary teacher education (teaching children at ages four to seven until eleven to 14, depending on the country), around one-third were conducted in the area of secondary teacher education (teaching children at ages eleven to 14 until 15 to 18, depending on the country), the fewest were in the area of early childhood education. The remaining studies did not specify the level of education.

Table 1. General characteristics of selected research articles (n = 46) on outdoor learning and teaching (OLT) in initial formal teacher training.

Regarding discipline, OLT was most often implemented or studied in the sciences, such as during a biology or science methods course. In addition to being integrated into social sciences and physical education, OLT is also explicitly offered in courses on outdoor or environmental education in teacher education programs (). The outdoor environment in which OLT took place was often not specified, and some studies collected data without reference to a course. If the environment for OLT was mentioned in studies, it was twice as likely to be a forest, clearing, or botanical garden, rather than school grounds, the university campus, a park, or close to water bodies. Around 70% of studies reported the durations of OLT courses or events. Most reported durations between one and 13 weeks. A small number reported durations of between one and four hours.

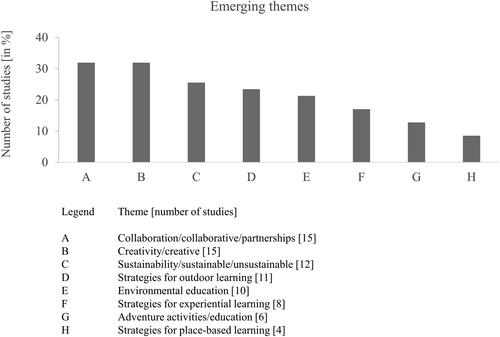

RQ2 Emerging themes of research

The most frequently mentioned themes were collaboration, creativity, sustainability, and strategies for outdoor learning (). Collaboration and creativity were mentioned as skills to develop during training. Collaboration also included partnering with schoolteachers or other staff outside the teacher training institutions for the delivery of teaching. Creativity was mentioned as a strategy for problem-solving or a practice for creative thinking. Sustainability served as thematic content for courses, such as exploring local and global issues from ecological and socio-cultural perspectives. Strategies for outdoor learning was the broadest theme and was connected to all other themes. These top four themes occurred in around a third of analyzed articles each and are described and characterized in the next paragraphs.

Figure 2. Distribution of themes identified in research regarding outdoor teaching in initial schoolteacher training.

The theme environmental education occurred in 21% and adventure activities/education, strategies for experiential learning, and strategies for place-based learning occurred in less than 20% of the analyzed articles (). Environmental education and strategies for outdoor learning are thematically close. They were distinguished according to the occurrence of the words in the text material and according to their attribution to either a content (environmental education) or methodological orientation (strategies for outdoor learning). Experiential learning was mentioned as a learning strategy for PSTs to enable them to engage more closely with the natural outdoor environment as a learning space and to develop outdoor (pedagogical) skills. While adventure activities were associated with risk-taking, team challenges, and physical education, strategies for place-based learning were interpreted as authentic, hands-on activities embedded in local contexts, near ‘green spaces’ and considered as potential learning environments.

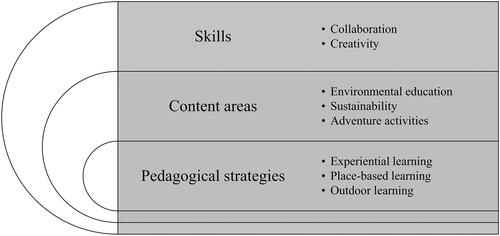

Areas of context

The themes across the studies are diverse and reflect different areas of context (). The first area (skills) not only supports skill development in PSTs, but also various benefits gained from collaborations arranged by teacher educators and from creative/innovative program design. The second area (content) not only describes fields of topics to demonstrate outdoor learning, but also includes ways in which those fields of topics serve as vehicles for teacher educators to develop the motivation and self-efficacy of PSTs. The third area (pedagogical strategies) describes the types and impacts of various forms of learning that PSTs experienced or observed ().

Figure 3. Areas of context, comprising skills, content areas and pedagogical strategies, were identified through the analysis of 46 studies on outdoor teaching in initial schoolteacher training.

In the following section, we describe and characterize the four themes mentioned most frequently in the research concerning initial formal schoolteacher training with regard to outdoor teaching. The themes are characterized, firstly, by their frequency in the articles studied and secondly, the findings from the research are distinguished between insights into teacher educators’ outdoor teaching and PSTs’ outdoor learning.

Collaboration

Collaboration, collaborative, or partnerships was summarized into collaboration and is associated with the skills area. It was evident in 15 of the 46 analyzed articles.

Teacher educators’ outdoor teaching

The studies reported three dimensions of collaboration in relation to supporting OLT in teacher training: firstly, collaboration and/or partnerships between universities and schools (e.g., Moseley et al., Citation2002) or the community (e.g., Kalungwizi et al., Citation2020). Some teacher education universities used external expertise to support the teaching of PSTs, e.g., in global environmental issues or locally relevant topics (Kalungwizi et al., Citation2020; Zandvliet, Citation2019). Kalungwizi et al. (Citation2020) described how PSTs and tutors from a teacher education college in Tanzania worked together with primary schoolteachers to learn about environmental challenges from local actors. The goal was to help PSTs to teach environmental education confidently. Local leaders or activists in the community helped to plan and implement environmental activities within the schools. Such collaborations motivated PSTs and local communities to address local environmental issues.

The second dimension was collaboration between teacher educators within teacher education universities. Teacher educators in England worked together to facilitate a training intervention for primary and secondary PSTs, enabling collaboration in planning imaginative fieldwork activities for children in an urban green space (Bore, Citation2006). Through the training intervention, PSTs discovered the potential of environmental education as a context for creativity and continuity for curriculum planning and explored how to use environmental education to develop scientific and eco-literacy (Bore, Citation2006).

The third dimension was collaboration in the context of teaching strategies. For example, stimulating collaborative conversations between PSTs, e.g., discussing the ecology and health of water bodies (Howes et al., Citation2004) or learning strategies to resolve conflicts between colleagues in an outdoor education methods course (Jacobs et al., Citation2019) were mentioned in the context of how collaboration can facilitate the reflection process. Another study described how PSTs’ understanding of theory and practice for early childhood outdoor pedagogy was shaped through collaborative reflection during a field trip to Danish Forest Kindergartens. Collaborative reflections supported PSTs’ alternative constructions of outdoor pedagogy, the roles of adult and child and challenged their assumptions of characteristics of good outdoor practice. Here, collaborative reflections linked to a field trip (real-world context) were used to elaborate outdoor pedagogy in early childhood education (Layen & Hattingh, Citation2020).

PSTs’ outdoor learning

Collaboration or partnerships with parts of the local community, like botanical gardens, schools, kindergartens, other local leaders, or community members (Bore, Citation2006; Kalungwizi et al., Citation2020; Zandvliet, Citation2019) enhanced PSTs’ place-based learning and extended their teaching strategies (Zandvliet, Citation2019). Learning about the local environment and associated local problems by collaborating with environmentally active community members and schools motivated PSTs to learn more about the meaningful teaching of environmental education (Kalungwizi et al., Citation2020). Kärki et al. (Citation2018) explored mobile outdoor learning in the context of meaningful learning. Pre-service teachers in Finland learned about mathematics, health-related issues in everyday life, and exploring the daily environment from an outdoor learning perspective by using an action track app. The attribute “collaborative” received the highest mean scores from PSTs and was described as peer support, feedback, and using the individual strengths of the group members (Kärki et al., Citation2018). When PSTs explore place-responsive education they learn how to utilize local people and places in their teaching. Given the chance to experience learning in and about the natural world, PSTs can realize their need to use the collective knowledge of teaching/learning groups. Partnering with regional communities for outdoor learning fostered PSTs’ confidence in teaching beyond traditional settings and working together with peers (Green & Dyment, Citation2018).

Creativity

Creativity or creative, a theme associated with the skills area, was evident in 15 of the 46 analyzed articles. Creativity can be defined in different contexts. Ken Robinson said in 2014 “it is primarily the (crafting) process of (a person or a group) creating original ideas that have value in the context of inventions, problem solving, creative thinking or the artistic field.” (Greenberg, Citation2014). When examining the field of research into outdoor teaching in the analyzed studies, it seems that training can be given to support skills in problem solving and creative thinking.

Teacher educators’ outdoor teaching

If teacher educators design courses in innovative and creative ways, even online courses can be a viable and valuable way for PSTs to gain knowledge and understanding about outdoor education (Dyment et al., Citation2018). Dyment et al. (Citation2018) reported that conventional teaching approaches were failing to instill (in their PSTs and themselves as teacher educators) the capacity to imagine and develop creative and emergent pedagogical ideas. This was also the case when PSTs had to teach outdoor activities that they had not developed themselves (Richards et al., Citation2018).

PSTs’ outdoor learning

One general finding was that positive physical and mental experiences in nature supported PSTs’ learning and creativity (Blatt & Patrick, Citation2014; Çirak Karadağ, Citation2019; Goulet & McLeod, Citation2002; Gray & Colucci-Gray, Citation2019; Lamorey, Citation2013; Zacharious & Valanides, Citation2006). Pre-service teachers in the U.S. stated that nature is not only important for learning but also for the development of creative thinking (Shume & Blatt, Citation2019). Creativity was perceived as a requirement for outdoor adventure activities by PSTs in Brazil, who associated it with initiative and proactive behavior (Marinho et al., Citation2017). In that same study, most PSTs rated creativity and leadership as crucial factors regarding professional competence in outdoor adventure education. Primary and secondary PSTs in England were given the opportunity to develop ideas for educational opportunities in a Botanical Garden to develop children’s eco-literacy, action competences, and views on the value of the garden environment to the community (Bore, Citation2006). The PSTs reported that environmental education was a potent source of creativity and continuity in curriculum planning for science (Bore, Citation2006). However, some PSTs found it difficult to connect the ecological contents to other parts of the science curriculum. Bore (Citation2006) found that those PSTs who had not been previously exposed to school practice during their training, planned more pupil-centered, explorative, and creative activities for children. Outdoor programs (in nature) often included new experiences or perspectives on learning strategies or content for PSTs, which in turn inspired them and stimulated their creativity to plan and implement outdoor or nature-based learning arrangements (Goulet & McLeod, Citation2002; Gray & Colucci-Gray, Citation2019; Zacharious & Valanides, Citation2006).

Sustainability

The theme of sustainability was evident in 12 of the 46 analyzed articles and is associated with content area. Content area includes different fields of topics associated with aspects of sustainability, or explicitly, education for sustainable development (ESD), understanding and actions for environmental sustainability, biodiversity education, and social sustainability in the context of initial formal schoolteacher training. It also includes ways in which those topics serve as vehicles for teacher educators to develop the motivation and self-efficacy of PSTs. Generally, learning about aspects of sustainability or ESD was associated or encouraged by learning in authentic environments outdoors. The sustainability theme was closely related to environmental topics.

Teacher educators’ outdoor teaching

In several studies, it was concluded that PSTs need opportunities to experience the natural world that promote PSTs’ knowledge and skills, e.g., ecological literacy, which is considered an important part of professional development in sustainability education (Palmberg et al., Citation2015; Palmberg et al., Citation2018; Skarstein & Skarstein, Citation2020). Australian teacher educators reported a lack of environmental and sustainability-related education within the initial schoolteacher training program and poorly developed environmental knowledge and concerns among many of their PSTs (Green & Dyment, Citation2018). They offered courses, which focused on place-responsive education to help PSTs understand the pedagogical value of the local, cultural, and environmental dimensions of places close to home to favor children’s learning of science, sustainability, and literacy. The conservation of natural resources is a main purpose of environmental education in Tanzania. However, teaching environmental topics is still a main challenge and the need for sustainable environmental activities and policy support encouraged Kalungwizi et al. (Citation2020) to develop outdoor activities for environmental education together with teacher educators, PSTs, primary schoolteachers, and local actors. The PSTs learned how to teach their school students about environmental activities such as tree-planting, gardening, and ocean cleaning. This improved their ability to plan and implement experiential teaching lessons connected to local environmental topics. Kalungwizi et al. (Citation2020) concluded that when PSTs learn sustainable practices themselves, they can be facilitators for the understanding and practice of environmental sustainability in the broader community.

A Canadian teacher educator addressed global issues such as the inequitable distribution of wealth and resources, food production, or transportation in a university field school on Hawaii, which is part of an elective environmental education course (Zandvliet, Citation2019). The field school includes the idea of the ecology of home model, which “describes the forces that we enact or that act on us where we live” (p. 148) and applies a multidisciplinary approach to help PSTs understand aspects of ESD and a sustainable society. During the field school, PSTs also engaged in field work, community service, and curriculum development.

PSTs’ outdoor learning

A project in Cyprus examined the impact of an outdoor program on PSTs and primary school children (Zacharious & Valanides, Citation2006). For two months, PSTs designed and applied innovative pedagogical activities to global social, ecological, and economic issues. The training program included theory and practice and helped PSTs understand the concept of sustainable development with its complexities and interconnections to relevant issues, which in turn helped develop personal and professional responsibility in matters of sustainable development (Zacharious & Valanides, Citation2006).

During a three-day outdoor residential field course, Norwegian science and mathematics PSTs learned about the environment in a specific area and how to use this environment for outdoor pedagogy to facilitate the realization of ESD (Jegstad et al., Citation2018). The PSTs prepared and practiced pupil-active teaching methods such as inquiry-based learning and phenomenon-based teaching; gained ESD competencies such as problem-solving, creativity, or critical thinking; and reported an increased motivation and confidence to teach science in a natural environment. Here, the environment and connection to nature was crucial as an intrinsic motive “for contributing to sustainable development, both personally and in the role as a teacher” (Jegstad et al., Citation2018, p. 109).

Nordic-Baltic primary PSTs suggested experiential learning outdoors as the most efficient learning method for knowledge and understanding of biodiversity and ESD (Palmberg et al., Citation2015). In Finland, Norway, and Sweden, primary PSTs rated biodiversity and species identification as important for sustainability education (Palmberg et al., Citation2018). Their statements were mainly explained by ecological (scientific, conservation, and naturalistic) views and less by emotional (feelings concerning nature) and educational (professional and general education) views. The latter mostly consisted of general rather than professional perspectives. Several PSTs reported that “species identification would help them understand their own environment” (p. 408). Palmberg et al. (Citation2018) stressed that teacher training programs should include interdisciplinary, interactive learning in natural environments. Norwegian early childhood PSTs expressed a need for species knowledge for nature excursions to encourage children’s curiosity, understanding of, and relationship with nature (Skarstein & Skarstein, Citation2020). Skarstein and Skarstein (Citation2020) concluded that PSTs need both the knowledge and skills to facilitate the variety of learning possibilities that exist in nature and presented species identification as an important aspect for early childhood teacher training as well as for sustainable development.

Strategies for outdoor learning in initial schoolteacher training

Enabling outdoor learning for PSTs was a constant characteristic in all studies. However, 11 of the 46 analyzed articles focused on strategies to facilitate outdoor learning.

Teacher educators’ outdoor teaching

Legge and Smith (Citation2014) reported about their twenty years of annual five-day bush-based residential camps with physical education PSTs in New Zealand. Activities included connecting oneself to the environment, native plant identification and awareness, native flora as cultural identity, and an overnight solo survival experience. These activities created the basis for experiential outdoor learning and place-based experiences to support PSTs for their future outdoor planning and teaching (Legge & Smith, Citation2014). The strategies could be quite different. In Finland, teacher educators used technology including mobile learning with an app to show PSTs how to use different learning environments like the outdoors for meaningful learning (Kärki et al., Citation2018). Teaching food chemistry and replacing some lab units with outdoor fieldwork, teacher educators in Norway suggested that outdoor teaching units need to be followed up with reflective teaching sequences to make sure that intended learning outcomes have been achieved (Höper & Köller, Citation2018). Two teacher educators in Israel advocated to carefully prepare PSTs to plan and perform outdoor learning activities for schoolchildren as they rarely get to prepare and practice teaching in the outdoors in their methods course or during their practicum (Tal & Morag, Citation2009). It would be especially important to support PSTs during their outdoor teaching experiences and reflect individually and in the group about their outdoor teaching experiences afterwards (Tal & Morag, Citation2009).

PSTs’ outdoor learning

Outdoor learning became more relevant to PSTs when they could observe the way in which children learn outdoors (Höper & Köller, Citation2018; Scott et al., Citation2015; Tal & Morag, Citation2009; Torquati et al., Citation2017). In the context of science, PSTs expressed difficulties in carrying out outdoor learning activities because of concerns about logistic obstacles and pupils’ learning outcomes (Karademir & Erten, Citation2013; Shume & Blatt, Citation2019). The teaching of environmental topics as such has been reported as challenging by Tanzanian PSTs (Kalungwizi et al., Citation2020). In an outdoor chemistry course, Norwegian PSTs referred to the importance of clear assignments, suitable group sizes, and outdoor locations for promoting a positive learning environment (Höper & Köller, Citation2018). However, PSTs’ misconceptions of understanding organic chemistry in organisms were questioned and solved by transferring them into a real-life context using an outdoor chemistry approach inspired by the concept of “chemistry trails” (Höper & Köller, Citation2018, p.27). Subramaniam (Citation2019) reported that elementary PSTs in the U.S. think about teaching life sciences outdoors as being situated in the schoolyard, being taught teacher-directed, and disconnected from classroom science instruction.

The willingness to perform outdoor learning activities was emphasized by PSTs as a prerequisite in Turkey (Karademir & Erten, Citation2013). Barrable and Lakin (Citation2020) showed that PSTs’ nature relatedness was positively associated with perceived competence and a willingness to undertake outdoor sessions, and that nature relatedness increased after practical environmental outdoor sessions. A limited affinity for the outdoors was concurrently suggested to be associated with a lower appreciation of outdoor experiences and outdoor learning (Scott et al., Citation2015).

In the U.S.A., outdoor learning, taught through an outdoor education course, as well as a teaching experience with primary school students (ages six to 11/12), could increase PSTs’ confidence to teach physical outdoor education (Richards et al., Citation2018). Early childhood PSTs in the U.S. and primary PSTs in Tanzania reported similar planning processes and the implementation of environmental education activities following their own outdoor learning experiences (Torquati et al., Citation2017; Kalungwizi et al., Citation2020, respectively). Researchers suggested including outdoor learning in independent courses or integrated in field trips and science courses within the initial schoolteacher training curriculum (Dyment et al., Citation2018; Gray & Colucci-Gray, Citation2019; Höper & Köller, Citation2018; Kalungwizi et al., Citation2020; Karademir & Erten, Citation2013; Richards et al., Citation2018; Tal & Morag, Citation2009; Uzel, Citation2020).

Combination of themes for teacher training

When considering possible relationships between themes, we found that some themes identified in our analysis overlapped within individual studies (). This might be of relevance for future research and practice of OLT in initial formal teacher training. The most frequent combination of themes included courses for PSTs linked to learning or experiences of collaboration with educational goals relating to either creativity, education for sustainability, or environmental education (13% of analyzed studies). Almost as often, themes and strategies for environmental education and education for sustainability were combined for implementation or research of OLT in schoolteacher training (11%). A smaller number of themes emerged from studies that addressed outdoor and experiential learning strategies, sustainability, and creativity, or that emphasized creative thinking through OLT in PSTs (9%).

Table 2. Matrix presenting relations (proportions from total number of analyzed studies) between themes from research on outdoor learning and teaching in formal initial schoolteacher training.

Discussion and conclusion

The present review outlines the themes of outdoor learning and teaching in initial formal schoolteacher training, which, according to research, demonstrate evidence of supporting teacher educators’ outdoor teaching and PSTs’ outdoor learning and teaching (OLT) skills.

General characteristics of research into outdoor learning and teaching in initial formal schoolteacher training

We found that most data in this field of research come from qualitative studies, of which most examine the opinions and attitudes of PSTs. Over 70% of the analyzed articles in this review did not refer to or mention the validity of research instruments. Some articles were not precise in their description of study population or in which study field or university course the study was conducted. Research in this area could benefit from clearly describing these study characteristics. Reviews like those of Ayotte-Beaudet et al. (Citation2017) provide a clear overview (analysis grid), describing which variables are important for the transparency of the research and for further review articles.

Thirty-four of the analyzed 46 studies are based in science and physical teacher education. The review presents an argument for examining and evaluating the outdoor learning environment in terms of more aspects than these two subject areas. Further investigation of how to integrate OLT, e.g., in languages and visual arts, could help to advance recognition and understanding of OLT as a concept or strategy in initial schoolteacher training.

Emerging themes of research into outdoor learning and teaching in initial formal schoolteacher training

Skills

Collaboration and creativity are two of the 21st century skills required to face present and future challenges in our society (Chiruguru, Citation2020). For that reason, PSTs should be trained in those competences, so that they themselves can use them and can train students to use them. Multiple studies have found that PSTs’ professional confidence is enhanced when they learn how to solve local, real-world problems in the outdoors in collaboration with their peers. One way to support 21st century skills development in PSTs is through teacher training colleges, local stakeholders, and schools engaging in outdoor learning collaboration (Kalungwizi et al., Citation2020; Tal & Morag, Citation2009; Zandvliet, Citation2019). Creativity was mentioned on fewer occasions than collaboration as a skill in which PSTs should be trained. Instead, it was reported as a valuable by-product from engaging in OLT activities. One study addressed environmental education as a potential context for creativity and continuity in curriculum planning, linking environmental topics with science (Bore, Citation2006). An interesting question is whether 21st century skills could be developed as a subject area for teacher education.

Content

Interestingly, ESD was almost exclusively mentioned in the context of ecological sustainability but rarely in the social or economic contexts of sustainability. Therefore, there is potential in the research field of outdoor teaching to strengthen the connection among ecological, cultural, and economic perspectives and consequently, to expand into other disciplines. The “re-orientation” of all education, declared by the Agenda 21 (United Nations, 1992), explicitly states that ESD should be integrated into school curricula. Such a holistic approach requires that PSTs learn methods and content for integrating subject-based knowledge into a real-world context and offers opportunities to experience and learn in authentic environments. Kassahun Waktola (Citation2009) concluded that the curricula of teacher colleges in Tanzania should provide more environmental knowledge and practice on how to use local environmental resources for outdoor teaching.

Strategies

Exploring the ecological, socio-cultural, and technical factors of natural places helps PSTs consider the multiple (cultural) perspectives on local (home) issues (Zandvliet, Citation2019). Place-based education or activities include opportunities for educational objectives in various subject areas. Visual arts can express the synergy of real-world community-based learning and open a dialogue between students and the community with regard to a particular place (Hursen & Islek, Citation2017; Inwood, Citation2008). Integrating local environments or places and giving PSTs professional and emotional support (Tal & Morag, Citation2009) can create a positive learning environment, which in turn could support the development of PSTs’ positive attitudes toward the environment (Barrable & Lakin, Citation2020; Çirak Karadağ, Citation2019) and teaching outdoors (Niklasson & Sandberg, Citation2012). A practical attitude through participation in OLT should be infused into every subject area (Parr, Citation2005) in teacher training to prepare PSTs for engaging their students in outdoor learning. Parr argues that “[i]t is only through our own participation and engagement that we truly come to acknowledge the challenges faced by our students and the demands (instructional and otherwise) that we place on our students, and realize the importance of trust, risk-taking, and confidence, which ultimately lead to full engagement of our learners” (p. 139).

Basic teaching competences with relevance for outdoor teaching

Apart from the emerging themes, we found that a variety of aspects described in the studies are not unique to outdoor teaching, e.g., the professional competence of PSTs. However, these are relevant for general teacher training. Consequently, several competences associated with general training in initial schoolteacher training, such as reflection, are also relevant for outdoor teaching. Some topics for reflection include, for example, teacher educators’ reflection on teaching practice, e.g., regarding the conflicting discourse on theory-practice relationships (Clayton et al., Citation2014; North, Citation2017), or PSTs’ divergent attitudes and perspectives in determining which is more essential in outdoor education, the adventure education approach or the place-based education approach (Atencio & Tan, Citation2016; Timken & McNamee, Citation2012; Zandvliet, Citation2019). Species knowledge and water ecosystems are typical topics for biology education, but were transformed into special experiences, both for PSTs and schoolteacher trainers, due to the outdoor context (Howes et al., Citation2004).

Limitations of the review

We recognize that the review does not reflect all available research to give a complete picture of the state of research. We focused on specific search terms and used the most relevant research databases to provide an overview of reoccurring themes in the research into OLT in initial formal schoolteacher training. We identified sustainability as an emerging theme from the literature, as it was mentioned and referred to in the respective studies. Sustainability should include ecological, social, and economic components. The latter was not mentioned in any of the analyzed studies. Studies regarding sustainability were strongly related to environmental education and were perhaps not associated with defined sustainability, although there was an incentive for sustainable thinking and action.

Implications for further research

In general, there is more literature in the field of outdoor learning than there is in relation to outdoor teaching. The disparity in research literature is also evident with regard to outdoor learning for students in schools versus PSTs in initial teacher training institutions. This is an indication that there is still a great deal of potential in exploring how to facilitate and emphasize OLT from the educators’ perspective, especially in initial schoolteacher training. The present review lays a foundation for future reviews and highlights interesting remaining research questions to be explored in this area. Associated themes such as collaboration, creativity, strategies for outdoor learning, and environmental education in initial schoolteacher training could reveal useful insights into multifaceted learning effects for PSTs. Including more details on research method, instrument validation, participant selection, or outdoor programs could help future researchers plan projects. In addition to specific issues, more fundamental aspects are also emerging such as how to train the trainers, set and monitor the training objectives, and identify which tools are helpful in evaluating OLT in initial teacher training. A collection of “good practice” examples could support the development of a basic concept of outdoor teaching for initial formal schoolteacher training.

Implications for initial schoolteacher training

The themes found in the 46 analyzed studies do not yet provide the outline of an action plan for the basic implementation of OLT in initial formal schoolteacher training. However, the literature provides insights into ideas, strategies, and examples for the integration of outdoor teaching into the initial schoolteacher training curriculum.

One finding that almost all the studies had in common was that continuous practice during initial schoolteacher training can increase PSTs’ self-confidence and self-efficacy in outdoor teaching (Hovey et al., Citation2020; Kassahun Waktola, Citation2009; Lindemann-Matthies et al., Citation2011; Marinho et al., Citation2017). In 1960, Hammerman described the importance of elementary PSTs’ firsthand outdoor experiences throughout their training years, with an increasing number of experiences per year (Hammerman, Citation1960). He concluded that to gain the ability to teach classes inside and outside the classroom, PSTs first need to collect a variety of direct experiences themselves and secondly, gain outdoor knowledge and skills (Hammerman, Citation1960). We agree with Hammerman and add that in addition to regular experiences, PSTs should learn how to transfer learning opportunities from the outdoors to the classroom and vice versa.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our research team, especially Robbert Smit and Sanja Atanasova, who supported us with helpful feedback and creative ideas in the analysis process. We would especially like to thank Ismael Zosso from the Waadt University of Teacher Education (Switzerland) for his expertise on outdoor education and his perspective as a teacher educator for outdoor teaching, as well as Rolf Jucker, head of the outdoor teaching organization, Silviva, for his support and feedback. We would also like to recognize and thank our student assistants, Michelle Porchet and Malin Wiget, for their research work.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Atencio, M., & Tan, Y. S. M. (2016). Teacher deliberation within the context of Singaporean curricular change: Pre- and in-service PE teachers’ perceptions of outdoor education. The Curriculum Journal, 27(3), 368–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2015.1127843

- Ayotte-Beaudet, J.-P., Potvin, P., Lapierre, H. G., & Glackin, M. (2017). Teaching and learning science outdoors in schools’ immediate surroundings at K–12 levels. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 13(8), 5343–5363. https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2017.00833a.

- Barrable, A., & Lakin, L. (2020). Nature relatedness in student teachers, perceived competence and willingness to teach outdoors: An empirical study. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 20(3), 189–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2019.1609999

- Beames, S., Higgins, P., & Nicol, R. (2011). Learning outside the classroom: Theory and guidelines for practice. (1st ed.) Routledge.

- Bentsen, P., & Jensen, F. S. (2012). The nature of udeskole: Outdoor learning theory and practice in Danish schools. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 12(3), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2012.699806

- Bentsen, P., Mygind, E., & Randrup, T. B. (2009). Towards an understanding of udeskole: Education outside the classroom in a Danish context. Education 3-13, 37(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004270802291780

- Bentsen, P., Mygind, L., Elsborg, P., Nielsen, G., & Mygind, E. (2022). Education outside the classroom as upstream school health promotion: ‘Adding-in’ physical activity into children’s everyday life and settings. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 50(3), 303–311.

- Blatt, E., & Patrick, P. (2014). An exploration of pre-service teachers’ experiences in outdoor ‘places’ and intentions for teaching in the outdoors. International Journal of Science Education, 36(13), 2243–2264. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2014.918294

- Bølling, M., Otte, C. R., Elsborg, P., Nielsen, G., & Bentsen, P. (2018). The association between education outside the classroom and students’ school motivation: Results from a one-school-year quasi-experiment. International Journal of Educational Research, 89, 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2018.03.004

- Bølling, M., Niclasen, J., Bentsen, P., & Nielsen, G. (2019). Association of education outside the classroom and pupils’ psychosocial well-being: Results from a school year implementation. The Journal of School Health, 89(3), 210–218.

- Bore, A. (2006). Creativity, continuity and context in teacher education: Lessons from the field. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 22(1), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0814062600001634

- Breunig, M., Murtell, J., & Russell, C. (2015). Students’ experiences with/in integrated environmental studies programs in Ontario. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 15(4), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2014.955354

- Casey, A., & Goodyear, V. A. (2015). Can cooperative learning achieve the four learning outcomes of physical education? A review of literature. Quest, 67(1), 56–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2014.984733

- Chiruguru, S. (2020). The Essential Skills of 21st Century Classroom (4Cs). Project: The role of 4Cs (Critical Thinking, Creative Thinking, Collaboration and Communication) in the 21st Century Classroom. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.36190.59201

- Çirak Karadağ, S. (2019). Psychosocial achievements of social studies teacher candidates in outdoor geography courses. Review of International Geographical Education Online, 9(3), 663–677.

- Clayton, K., Smith, H., & Dyment, J. (2014). Pedagogical approaches to exploring theory–practice relationships in an outdoor education teacher education programme. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 42(2), 167–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2014.894494

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Dale, R. G., Powell, R. B., Stern, M. J., & Garst, B. A. (2020). Influence of the natural setting on environmental education outcomes. Environmental Education Research, 26(5), 613–631. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1738346

- Department for Education and Skills (DfES). (2003). Excellence and enjoyment: A strategy for primary schools University College London, Institute of Education, Digital Education Resource Archive (DERA).

- Dunn, J. G. H., Bouffard, M., & Rogers, W. T. (1999). Assessing item content-relevance in sport psychology scale-construction research: Issues and recommendations. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 3(1), 15–36. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327841mpee0301_2

- Dyment, J., Downing, J., Hill, A., & Smith, H. (2018). I did think it was a bit strange taking outdoor education online’: Exploration of initial teacher education students’ online learning experiences in a tertiary outdoor education unit. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 18(1), 70–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2017.1341327

- Dyment, J., Morse, M., Shaw, S., & Smith, H. (2014). Curriculum development in outdoor education: Tasmanian teachers’ perspectives on the new pre-tertiary outdoor leadership course. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 14(1), 82–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2013.776863

- Fägerstam, E. (2014). High school teachers’ experience of the educational potential of outdoor teaching and learning. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 14(1), 56–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2013.769887

- Glackin, M. (2016). „Risky fun “or authentic science”? How teachers’ beliefs influence their practice during a professional development programme on outdoor learning. International Journal of Science Education, 38(3), 409–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2016.1145368

- Goulet, L., & McLeod, Y. (2002). Connections and reconnections: Affirming cultural identity in aboriginal teacher education. McGill Journal of Education/Revue Des Sciences de L’éducation de McGill, 37(3), 355–370.

- Gray, D. S., & Colucci-Gray, L. (2019). Laying down a path in walking: Student teachers’ emerging ecological identities. Environmental Education Research, 25(3), 341–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2018.1499014

- Green, M., & Dyment, J. (2018). Wilding pedagogy in an unexpected landscape: Reflections and possibilities in initial teacher education. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 21(3), 277–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-018-0024-7

- Greenberg, B. (2014, August 30). Sir Ken Robinson - Can Creativity Be Taught? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vlBpDggX3iE

- Hammerman, D. R. (1957). Teacher education moves outdoors. Illinois Education, 45, 350–351.

- Hammerman, D. R. (1960). First-rate teachers need firsthand experience: The teacher who would bring meaning and understanding to learning should first be well grounded himself in a variety of direct experiences. Journal of Teacher Education, 11(3), 408–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/002248716001100320

- Hanna, G. (1992)., October 8-11). Jumping deadfall: Overcoming barriers to implementing outdoor and environmental education [Paper presentation]. In Celebrating our tradition charting our future: Proceedings of the International Conference for the Association for Experiential Education, Banff, Alberta, Canada. 77–84.

- Higgins, P., Nicol, R., Beames, S., Christie, B., Scrutton, R. (2021). Education and Culture Committee, Outdoor Learning. https://archive2021.parliament.scot/S4_EducationandCultureCommittee/Inquiries/Prof_Higgins_submission.pdf

- Höper, J., & Köller, H. G. (2018). Outdoor chemistry in teacher education—A case study about finding carbohydrates in nature. Lumat: International Journal of Math, Science and Technology Education, 6(2), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.31129/LUMAT.6.2.314

- Hovey, K., Niland, D., & Foley, J. T. (2020). The impact of participation in an outdoor education program on physical education teacher education student self-efficacy to teach outdoor education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 39(1), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2018-0288

- Howes, E. V., Jones, K. M., & Rosenthal, B. (2004). Cultivating environmental connections in science teacher education: Learning through conversation. Teachers and Teaching, 10(5), 553–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354060042000243042

- Hursen, C., & Islek, D. (2017). The effect of a school-based outdoor education program on visual arts teachers’ success and self-efficacy beliefs. South African Journal of Education, 37(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v37n3a1395

- Ihmeideh, F. M., & Al-Qaryouti, I. A. (2016). Exploring kindergarten teachers’ views and roles regarding children’s outdoor play environments in Oman. Early Years, 36(1), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2015.1077783

- Inwood, H. (2008). At the crossroads: Situating place-based art education. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 13(1), 29–41.

- Jacobs, J. M., Richard, K., Wahl-Alexander, Z., & Ressler, J. D. (2019). Helping preservice teachers learn to negotiate sociopolitical relationships through a physical education teacher education outdoor education experience. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 38(4), 296–304. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2018-0102

- Jaffe, D. K. (1955). Preparing teachers to teach outdoors. Nation’s Schools, 55, 47–50.

- Jegstad, K. M., Gjøtterud, S. M., & Sinnes, A. T. (2018). Science teacher education for sustainable development: A case study of a residential field course in a Norwegian pre-service teacher education programme. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 18(2), 99–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2017.1374192

- Jordet, A. H. N. (2007). „Naermiljøet som klasserom“: En undersøkelse om uteskolens didaktikk i et danningsteoretisk og erfaringspedagogisk perspektiv University of Oslo. (Doctoral Dissertation No. 80) [The local environment as classroom]

- Kalungwizi, V. J., Krogh, E., Gjøtterud, S. M., & Mattee, A. (2020). Experiential strategies and learning in environmental education: Lessons from a teacher training college in Tanzania. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 20(2), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2018.1555047

- Karademir, E., & Erten, S. (2013). Determining the factors that affect the objectives of pre-service science teachers to perform outdoor science activities. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology, 1, 270–293.

- Kärki, T., Keinänen, H., Tuominen, A., Hoikkala, M., Matikainen, E., & Maijala, H. (2018). Meaningful learning with mobile devices: Pre-service class teachers’ experiences of mobile learning in the outdoors. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 27(2), 251–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2018.1430061

- Kassahun Waktola, D. (2009). Challenges and opportunities in mainstreaming environmental education into the curricula of teachers’ colleges in Ethiopia. Environmental Education Research, 15(5), 589–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620903151024

- Kendall, S., Murfield, J., Dillon, J., & Wilkin, A. P. (2006). Education Outside the Classroom: Research to Identify What Training Is Offered by Initial Teacher Training Institutions. Research Report RR802. National Foundation for Educational Research.

- Kubat, U. (2017). Determination of science teachers’ opinions about outdoor education. Online Submission, 3(12), 344–354.

- Kuckartz, U. (2016). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung [Qualitative content analysis. Methods, practice, computer support]. (3rd revised ed.). Beltz Juventa.

- Kuckartz, U. (2019). Qualitative text analysis: A systematic approach. In G. Kaiser & N. Presmeg (Ed.), Compendium for Early Career Researchers in Mathematics Education. (pp. 181–197) Springer International Publishing.

- Lamorey, S. (2013). Making sense of a day in the woods: Outdoor adventure experiences and early childhood teacher education students. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 34(4), 320–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2013.845636

- Larsson, A., & Rönnlund, M. (2021). The spatial practice of the schoolyard. A comparison between Swedish and French teachers’ and principals’ perceptions of educational outdoor spaces. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 21(2), 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2020.1755704

- Layen, S., & Hattingh, L. (2020). Supporting students’ development through collaborative reflection: Interrogating cultural practices and perceptions of good practice in the context of a field trip. Early Years, 40(3), 306–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2018.1432572

- Legge, M., & Smith, W. (2014). Teacher education and experiential learning: A visual ethnography. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(39), 94–109. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2014v39n12.7

- Lieberman, G., Hoody, L. (1998). Closing the achievement gap. Using the environment as an integrate context for learning. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED428943.pdf.

- Lindemann-Matthies, P., Constantinou, C., Lehnert, H.-J., Nagel, U., Raper, G., & Kadji-Beltran, C. (2011). Confidence and perceived competence of preservice teachers to implement biodiversity education in primary schools—Four comparative case studies from Europe. International Journal of Science Education, 33(16), 2247–2273. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2010.547534

- Lloyd, A., Truong, S., & Gray, T. (2018). Take the class outside! A call for place-based outdoor learning in the Australian primary school curriculum. Curriculum Perspectives, 38(2), 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-018-0050-1

- Mann, J., Gray, T., Truong, S., Sahlberg, P., Bentsen, P., Passy, R., Ho, S., Ward, K., & Cowper, R. (2021). A systematic review protocol to identify the key benefits and efficacy of nature-based learning in outdoor educational settings. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 1199. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031199

- Marchant, E., Todd, C., Cooksey, R., Dredge, S., Jones, H., Reynolds, D., Stratton, G., Dwyer, R., Lyons, R., & Brophy, S. (2019). Curriculum-based outdoor learning for children aged 9-11: A qualitative analysis of pupils’ and teachers’ views. PloS One, 14(5), e0212242.

- Marinho, A., Santos, P. M. d., Manfroi, M. N., Figueiredo, J. d P., & Brasil, V. Z. (2017). Reflections about outdoor adventure sports and professional competencies of physical education students. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 17(1), 38–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2016.1218781

- Moseley, C., Reinke, K., & Bookout, V. (2002). The effect of teaching outdoor environmental education on preservice teachers’ attitudes toward self-efficacy and outcome expectancy. The Journal of Environmental Education, 34(1), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958960209603476

- Nicol, R. (2002). Outdoor education: Research topic or universal value? Part two. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 2(2), 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729670285200201

- Nicol, R. (2003). Outdoor education: Research topic or universal value? Part three. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 3(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729670385200211

- Niklasson, L., & Sandberg, A. (2012). Reflecting on field studies in teacher education: Experiences of student teachers in Sweden. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 33(3), 287–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2012.705807

- North American Association, & for Environmental Education (NAAEE). (2019). Professional development of environmental educators: Guidelines for excellence. NAAE.

- North, C. (2017). Swinging between infatuation and disillusionment: Learning about teaching teachers through self-study. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 22(4), 390–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2016.1268586

- O’Brien, L., & Murray, R. (2007). Forest school and its impacts on young children: Case studies in Britain. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 6(4), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2007.03.006

- Palmberg, I., Berg, I., Jeronen, E., Kärkkäinen, S., Norrgård-Sillanpää, P., Persson, C., Vilkonis, R., & Yli-Panula, E. (2015). Nordic–Baltic student teachers’ identification of and interest in plant and animal species: The importance of species identification and biodiversity for sustainable development. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 26(6), 549–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-015-9438-z

- Palmberg, I., Hermans, M., Jeronen, E., Kärkkäinen, S., Persson, C., & Yli-Panula, E. (2018). Nordic student teachers’ views on the importance of species and species identification. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 29(5), 397–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/1046560X.2018.1468167

- Parr, M. (2005). Knowing is not enough: We must do! Teacher development through engagement in learning opportunities. International Journal of Learning, 12(6), 135–140.

- Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. Blackwell Publishing.

- Rea, T., & Waite, S. (2009). International perspectives on outdoor and experiential learning. Education 3-13, 37(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004270802291699

- Remmen, K. B., & Iversen, E. (2022). A scoping review of research on school-based outdoor education in the Nordic countries. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 1–19. Ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2022.2027796

- Richards, K. A. R., Jacobs, J. M., Wahl-Alexander, Z., & Ressler, J. D. (2018). Preservice physical education teacher socialization through an outdoor education field experience. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 18(4), 367–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2018.1483252

- Rickinson, M., Dillon, J., Teamey, K., Morris, M., Choi, M. Y., Sanders, D., & Benefield, P. (2004). A review of research on outdoor learning. Field Studies Council, National Foundation for Educational Research and King’s College London.

- Roossinck, E. P. (1957). Use the outdoors as a resource in education. Illinois Education, 45, 315–315.

- Scott, G. W., Boyd, M., Scott, L., & Colquhoun, D. (2015). Barriers To biological fieldwork: What really prevents teaching out of doors? Journal of Biological Education, 49(2), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2014.914556

- Shulruf, B. (2010). Do extra-curricular activities in schools improve educational outcomes? A critical review and meta-analysis of the literature. International Review of Education, 56(5-6), 591–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-010-9180-x

- Shume, T. J., & Blatt, E. (2019). A sociocultural investigation of pre-service teachers’ outdoor experiences and perceived obstacles to outdoor learning. Environmental Education Research, 25(9), 1347–1367. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1610862

- Skarstein, T. H., & Skarstein, F. (2020). Curious children and knowledgeable adults—Early childhood student-teachers’ species identification skills and their views on the importance of species knowledge. International Journal of Science Education, 42(2), 310–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2019.1710782

- Skea, C., & Fulford, A. (2021). Releasing education into the wild: An education in, and of, the outdoors. Ethics and Education, 16(1), 74–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449642.2020.1822612

- Subramaniam, K. (2019). An exploratory study of student teachers’ conceptions of teaching life science outdoors. Journal of Biological Education, 53(4), 399–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2018.1472133

- Sutherland, S., & Legge, M. (2016). The possibilities of “doing” outdoor and/or adventure education in physical education/teacher education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 35(4), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2016-0161

- Tal, T., & Morag, O. (2009). Reflective practice as a means for preparing to teach outdoors in an ecological garden. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 20(3), 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-009-9131-1

- Timken, G. L., & McNamee, J. (2012). New perspectives for teaching physical education: Preservice teachers’ reflections on outdoor and adventure education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 31(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.31.1.21

- Torkos, H. (2018). Introducing new education types: Teachers’ opinions on outdoor education. Journal plus Education/Educatia Plus, 20(2), 198–212.

- Torquati, J., Leeper-Miller, J., Hamel, E., Hong, S.-Y., Sarver, S., & Rupiper, M. (2017). “ I Have a Hippopotamus!”: Preparing effective early childhood environmental educators. The New Educator, 13(3), 207–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/1547688X.2017.1331095

- Tuuling, L., Õun, T., & Ugaste, A. (2019). Teachers’ opinions on utilizing outdoor learning in the preschools of Estonia. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 19(4), 358–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2018.1553722

- United Nations Conference on Environment and Development 1992 : Rio de Janeiro, B. (1992). Agenda 21, Rio declaration, forest principles. United Nations.

- Uzel, N. (2020). Opinions of prospective biology teachers about “outdoor learning environments”: The case of museum visit and scientific field trip. Participatory Educational Research, 7(2), 115–134. https://doi.org/10.17275/per.20.23.7.2

- van Dijk-Wesselius, J. E., van den Berg, A. E., Maas, J., & Hovinga, D. (2020). Green schoolyards as outdoor learning environments: Barriers and solutions as experienced by primary school teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2919.

- Vinal, W. G. (1953). Outdoor education is a profession. Education, 73, 425–430.

- Waite, S. (2020). Where are we going? International views on purposes, practices and barriers in school-based outdoor learning. Education Sciences, 10(11), 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110311

- Waite, S., Passy, R., Gilchrist, M., Hunt, A., & Blackwell, I. (2016). Natural Connections Demonstration Project, 2012-2016: Final Report (NECR215). (Natural England, pp. 1–96). Plymouth Institute of Education.

- Zacharious, A., & Valanides, N. (2006). Education for sustainable development: The impact of an out-door program on student teachers. Science Education International, 17, 187–203.

- Zandvliet, D. (2019). Ecological education via “islands of discourse”: Teacher education at the intersection of culture and environment. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 22(2), 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-019-00037-3

Appendix

Table I. List of analyzed studies about research on outdoor learning and teaching in initial teacher training including (some) general characteristics, sorted according to geographic origin of data.