Abstract

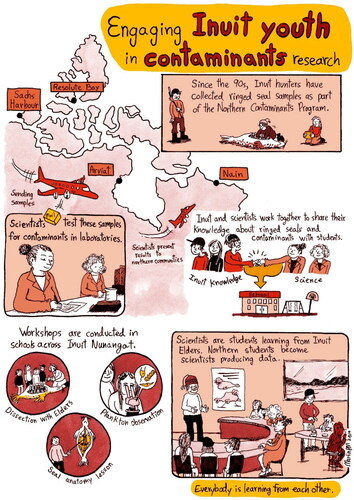

Since the 1990s, scientists and Indigenous peoples have worked together across Inuit Nunangat (Inuit homeland in Canada) to conduct research on contaminants in ringed seals (Pusa hispida; natsiq, natchiq or ᓇᑦᓯᖅ in Inuktut), a species of high cultural, economic and nutritional importance among Inuit. Developing innovative ways of engaging Indigenous communities in research has become essential. Here we examine a science outreach and knowledge mobilization project that was developed as part of a long-term contaminant monitoring program on ringed seals in the Canadian Arctic. This project engaged Inuit school students, youth and communities through workshops on ringed seal ecology and contaminants. We present our approach to workshop planning and delivery, discuss results from a workshop assessment, and reflect on lessons learned and best practices. We also assess the potential of school workshops that braid Western science and Inuit knowledge to support the meaningful engagement of Inuit youth in environmental research.

Introduction

The ringed seal (Pusa hispida; natsiq or natchiq or ᓇᑦᓯᖅ in Inuktut) has been harvested by Arctic Indigenous peoples since time immemorial (Koivura et al., Citation2020; Reeves et al., Citation1998). To this day, this species has played an important role in Inuit culture, diet and economy (Furgal et al., Citation2002; Hammill, Citation2018; Wenzel, Citation1991). Ringed seals are common throughout the Canadian Arctic, and the total population is estimated at about two million individuals across its circumpolar Arctic distribution range (Government-of-Canada, Citation2019; Kelly et al., Citation2010; Lowry, Citation2016).

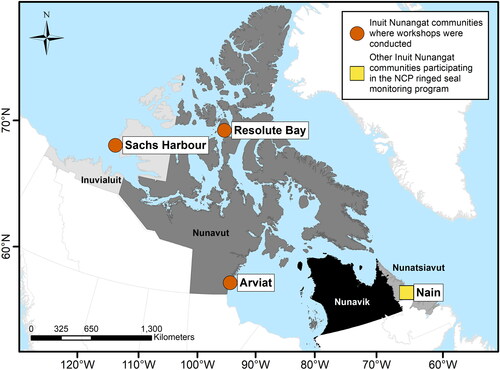

Environmental contaminants have been studied for decades in Arctic ringed seals, and high mercury concentrations found in ringed seal liver continue to be a concern for human health in some Inuit communities (Curren et al., Citation2017; Houde et al., Citation2020, Citation2019, Citation2017). In Canada, the Northern Contaminants Program (NCP) has been funding a long-term monitoring program on contaminants in ringed seals and supporting collaborative work between scientists and northern communities since the 1990s. Inuit hunters from the communities of Resolute Bay, Arviat, Harbour, and Nain have played a pivotal role in the success of this program by collecting ringed seal tissue samples (e.g., liver, blubber, muscle) and biological metrics (e.g., age, sex, length, girth) (Houde et al., Citation2020, Citation2019, Citation2017). Federal scientists have in the past communicated results to northerners (residents of northern regions in Canada) mostly through reports and community visits focused on local hunters and trappers organizations or associations. In recent years, Inuit organizations, research institutions and funding programs across Inuit Nunangat (Inuit homeland in Canada) have encouraged the development of innovative ways of engaging a wider range of northern community members in research on contaminants, and requested that research results be shared with northerners in an effective and timely manner (Inuit-Tapiriit-Kanatami [ITK], Citation2018a).

Meaningful research engagement and communication with northern residents can improve research methods and results, as well as enhance the usefulness of the information generated through the research process (Brunet et al., Citation2016; Gearheard & Shirley, Citation2009; Henri et al., Citation2020; Pearce et al., Citation2009). Given the importance of wildlife and the environment to Inuit cultural identity and livelihoods, Inuit have an interest in understanding and playing an active role in environmental research projects that reflect their priorities, and in seeing their knowledge guiding and contributing to such research (ITK, Citation2018a; Wilson et al., Citation2020). Across Inuit Nunangat, Inuit are working to achieve self-determination in research and greater engagement in decision-making processes embedded in research projects, including identifying research priorities, designing ethical methodologies allowing for knowledge co-production, and establishing appropriate data sharing practices (ITK, Citation2018a; Wilson et al., Citation2020). Thus, environmental research is increasingly driven by local and regional priorities, and approaches are developed to better reflect Inuit values and traditions (Brunet et al., Citation2014; ITK, Citation2018a). Conducting research in partnership with Indigenous communities instead of conducting research “on” or “in” Indigenous communities is the current paradigm in Canadian Arctic research (Brunet et al., Citation2016, Citation2014; MacMillan et al., Citation2019; Tobias et al., Citation2013; Vogel, Citation2015; Wong et al., Citation2020).

Over the years, researchers based in southern areas of Canada (who still represent the majority of investigators in Canadian Arctic research) have used various communication approaches to share information with Inuit communities including: attending in-person meetings with members from local organizations; disseminating information through printed media intended for local audiences; participating in interviews on local radio shows; social media; and occasionally conducting school presentations (Henri et al., Citation2020; Inuit-Tapiriit-Kanatami & Nunavut-Research-Institute [ITK & NRI], Citation2006). Visits to northern schools are often done by early-career researchers (i.e., students, post-doctoral fellows or early-career researchers). Consequently, the knowledge and expertise of highly trained researchers conducting fieldwork in the Canadian Arctic hardly reaches Inuit students (Henri et al., Citation2020). Acknowledging that the Inuit population is young and growing (Inuit-Tapiriit-Kanatami [ITK], Citation2018b), and that Inuit youth represent the next generation of researchers, hunters, knowledge holders, conservation officers, and resource managers, there is a pressing need to foster, train and engage Inuit youth within current research efforts (Sadowsky et al., Citation2022).

To date, only a few environmental science outreach projects or programs have been specifically designed for Inuit school-aged students in Inuit Nunangat; most of these programs have also occurred outside of school and regular instructional time. For example, the Students on Ice Expeditions program organizes annual educational expeditions to the Arctic for Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth, during which youth meet scientists, Elders, educators and leaders to learn from one another (https://soifoundation.org). ACTUA, a Canadian charitable organization that focuses on building confidence and skills in science, technology, engineering and math, delivers both school workshops and out-of-school summer day camps throughout the Arctic, with a focus on northern science (i.e., scientific research conducted in Arctic and northern regions) and traditional knowledge (https://actua.ca/en/programs/actua-in-the-north/). The Imalirijiit project led by local organizations from Kangiqsualujjuaq (Nunavik, Québec) and university-based researchers engages Inuit youth in a Science Land Camp program on water quality monitoring and environmental stewardship outside of the formal school environment (https://imalirijiit.weebly.com/).

Furthermore, education practitioners and researchers have called for greater braiding of Indigenous knowledge and Western science into science outreach and education (Druker-Ibáñez & Cáceres-Jensen, Citation2022; Kimmerer, Citation2002). “Weaving,” “braiding,” or “bridging” knowledge systems can be defined as a process through which multiple types of knowledge are equitably brought together to enable the reciprocal exchange of understanding for mutual learning (Alexander et al., Citation2019; Henri et al., Citation2021; Johnson et al., Citation2016; Tengö et al., Citation2017). One science outreach program that has successfully bridged Western science and Inuit knowledge is the Wildlife Contaminants Workshop held since 2011 at the Nunavut Arctic College Environmental Technology Program in Iqaluit, Nunavut (Provencher et al., Citation2013). This annual program teaches college students about contaminants by having Elders, researchers, hunters and some of the students all playing an instructor role in different modules of the workshops, thus creating a sharing and learning space for everyone present.

Efforts to braid Inuit knowledge and Western science related to wildlife and contaminants through science education and outreach initiatives are particularly important as Inuit knowledge offers unique perspectives and ecological insights (Houde et al., Citation2022; Muir et al., Citation2021). Inuit knowledge refers to the knowledge acquired by Inuit through their lifetime and intergenerational transmission (Berkes, Citation2012; Karetak et al., Citation2017). The expression “Inuit knowledge” is also commonly used across Inuit Nunangat and by Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the national organization representing Inuit in Canada (ITK, Citation2018b). However, science outreach activities conducted by wildlife researchers in northern schools rarely present the knowledge held by Inuit Elders or experienced hunters. A known exception is the “Purple Tongue” project in Nunavik which combined research results on nutritional values and health benefits of Arctic wild berries (Anhê et al., Citation2018; Lemire et al., Citation2014). The efficacy of such outreach projects is also hardly evaluated and rarely published in the peer-reviewed literature due to time or financial constraints (Gould et al., Citation2010), therefore minimizing how learning outcomes can be shared.

To address this gap, we developed a science outreach and knowledge mobilization project as part of a long-term contaminants monitoring program on ringed seals in the Canadian Arctic (Houde et al., Citation2020, Citation2019, Citation2017). This project engaged Inuit students (kindergarten to grade 12), youth and communities through school workshops on ringed seal ecology and contaminants (). We developed educational workshops for school-aged children drawing from experiential learning theory (Kolb, Citation1984; Wright, Citation2006). Main workshop objectives were to: (1) allow scientists working on contaminants in ringed seals to share information about their work with Inuit students and northern residents; (2) provide an opportunity for Inuit Elders and hunters to share their knowledge with students and researchers in seal ecology and traditional methods for hunting/processing seals, and identifying abnormalities and diseases in harvested animals; (3) increase the engagement of northerners and school-aged youth in contaminants research; and (4) support the training of northern college students and early career researchers to foster community engagement capacity and leadership among youth. Here we present our approach to workshop planning and delivery, discuss results from a workshop assessment, and reflect on project outcomes, lessons learned and best practices identified. In doing so, we assess the potential of school workshops that braid Western science and Inuit knowledge to support the meaningful engagement of Inuit youth and communities in environmental research.

Materials and methods

This project was conducted as a partnership between schools, hunters and trappers organizations, associations and/or committees (hereafter referred to as HTOs) from the communities of Resolute Bay, Sachs Harbour and Arviat, and researchers from Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC). It followed ethical guidelines from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for conducting research involving Indigenous peoples in Canada (Canadian-Institutes-of-Health-Research et al., Citation2018).

Project location

School workshops were conducted in Resolute Bay (Nunavut, 2016), Sachs Harbour (Inuvialuit Settlement Region [ISR] of the Northwest Territories, 2016), and Arviat (Nunavut, 2018) (), located in Inuit Nunangat where 83% of the population identify as Inuit (Li & Smith, Citation2016). These communities were selected due to their contribution to the long-term NCP-funded monitoring program on contaminants in ringed seals and the interest of community partners in hosting school workshops (Houde et al., Citation2020, Citation2019, Citation2017).

Project team and community partners

Our project team included three non-Indigenous scientists from ECCC, one university-based non-Indigenous early career researcher (ECR), and two Inuit college students attending the Nunavut Arctic College Environmental Technology Program. Community partners included local schools and HTOs. In each community, an experienced local hunter was hired to harvest seals and take part in the dissection activities (), and two Elders were invited by local HTOs to share their knowledge on ringed seals during the workshops; honoraria were offered in compensation for their time. Local interpreters were also hired to support English-Inuktut translation as required during workshop activities; here we employ the term “Inuktut,” which includes the Inuktitut (spoken in Resolute Bay and Arviat, Nunavut) and Innuinaqtun (spoken in Sachs Harbour, ISR) dialects.

Table 1. Activities co-created among project partners for educational school workshops on ringed seal ecology and contaminants (see Supplemental Material for additional information on workshop activities).

Workshop planning and delivery

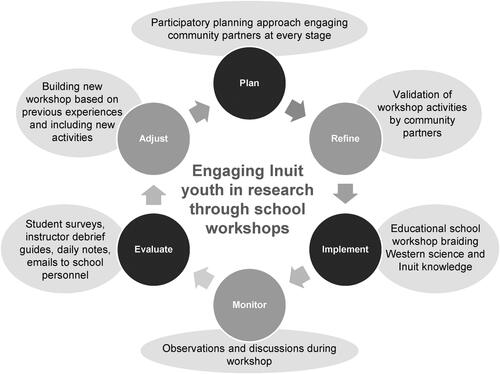

Workshops were planned employing a participatory approach engaging community partners at every stage (), adhering to the principles of relational accountability (Chilisa, Citation2012; Kovach, Citation2021; Ljubicic et al., Citation2021; Wilson, Citation2001; Wong et al., Citation2020; details in Supplemental Material). Over the course of three workshops, we visited four schools and engaged approximately 290 northern students (mainly Inuit) from kindergarten to high school, 17 teachers, as well as over 50 community members (Table S1 in Supplemental Material). The workshops lasted between one to two days, depending on the number of students and their age. In each participating community, three to five instructors (including scientists, Elders, ECR and college students) delivered one or more of the 15 educational activities developed (; ). The development of workshop activities was guided by theories of experiential learning (or learning by doing and reflecting; Kolb, Citation1984; Wright, Citation2006) and place-based learning in order for activities to be grounded in locally relevant content (Davidson-Hunt & O’Flaherty, Citation2007; Loveland, Citation2003). We took inspiration from the concept of play-based learning as a way to engage youth of various ages and multiple learner types (Taylor & Boyer, Citation2020). We also drew from the principles of “making and tinkering” which reflect practical, physical and playful modes of inquiry, and position students as knowledge producers (Gutwill et al., Citation2015; Vossoughi & Bevan, Citation2014). To support student learning, we created six large posters, an educational booklet and a one-page comic strip summarizing the project (). Activity sheets were also produced to guide instructors and inform school personnel about workshop activities (see Supplemental Material). Each new workshop was built on previous experiences, feedback received and included new activities ().

Figure 4. Examples of workshop activities: a) ringed seal dissection: Peter Amarualik Sr. shows students how to butcher a seal (Resolute Bay, 2016); b) seal stomach dissection: students look for different beads (each bead corresponds to a seal prey) by digging in a mock stomach made of jelly (Resolute Bay, 2016); c) observing and feeding plankton: Mick Appaqaq (Nunavut Arctic College student) helps students observing plankton on magnifying glass (Sachs Harbour, 2016); d) Inuktut lesson about seal anatomy: Elder Paul Sanertanut leads an Inuktitut lesson (Arviat, 2018).

Following the experiential learning framework, we employed a collaborative approach to workshop planning and delivery. Local school principals and teachers played key roles in both workshop preparation and implementation, acting as main points of contact between our project team and schools that were visited. Local teachers, in particular, provided valuable guidance on workshop design (scheduling, group size, activity types), and offered insightful advice to visiting instructors regarding teaching styles and techniques that were most adapted to the needs of their students (e.g., use of short games between educational activities, frequent repetition of new concepts, emphasis on hands-on activities). In some cases, teachers made instructional contributions as activity leaders (see “Inuktut lesson about seal anatomy” in ), and supported instructors by providing additional explanations to students when needed. Most importantly, our project team wanted to provide workshops that would effectively enhance student learning, and this was achieved by collaborating with local principals and teachers so we could collectively develop classroom activities (Moseley et al., Citation2020).

Workshop assessment

Upon workshop completion, the project team sought feedback from workshop participants and community partners through student surveys, instructor debrief guides, daily workshop notes, and emails to school personnel (; details in Supplemental Material). Approximately 30% (86 out of 291) of students who participated in the workshops completed written feedback surveys. Student surveys were either completed by individual students or by class; from the 17 student surveys obtained, eight represented the perspective of a single student, and nine represented class perspectives. Eleven instructor debrief guides were completed by a total of seven project team instructors (instructors who participated in multiple workshops completed one debrief guide after each workshop). We also took daily notes during all workshops; these included feedback received from school personnel. Emails received from a school principal were also used to inform our discussion.

Student surveys, instructor debrief guides, notes, and school personnel emails were entered into the qualitative analytical software program NVivo10 (Version 10, 2012), and analyzed using thematic content analyses (Creswell, Citation2009). When a student survey was obtained for a class as a whole (i.e., the teachers asked questions aloud to students and filled the survey themselves according to student answers), assumptions were made to obtain the approximate number of students involved in the survey based on participation on the day of the activity. For example, if the survey was filled by a class of 30 students, we assumed 50% of the students participated in the survey (n = 15). This assumption was based on feedback obtained from a class of 15 high school students, who shared eight individually filled student surveys. Note that number of students were systematically rounded up to the closest whole number. For student surveys completed by a class, we also assumed that each response represented a consensus from students. Statistical analyses were performed in the free software R 3.0.1 (Ihaka & Gentleman, Citation1996; R-Development-Core-Team, Citation2017). To compare proportions, Chi-squared tests with Yates continuity correction and Fisher-exact tests (for frequency lower or equal to 0.05) were used (see statistical results in Supplemental Material).

Our workshop assessment strategy presented limitations similar to those reported in previous studies (Clark et al., Citation2016; Roberts & Wassersug, Citation2009). For example, anonymous student surveys did not allow the collection of information on student age and it was difficult to obtain the exact numbers of students who participated in the workshops and the surveys. We were also aware of the potential bias created by conducting our own analyses of the workshops we developed. To address this, an independent researcher (LMML), who did not plan or participate in any of the workshops, conducted the analyses.

Results

Perspectives from students

Out of the 86 students who participated in the survey, 87% indicated that they learned from activities conducted at the workshops (see Supplemental Material for details related to this section). Specifically, of the students who reported learning outcomes (n = 75), 29% mentioned learning about the Arctic food chain and contaminants and 21% reported learning about ringed seal preys: “We learned different things that seals ate by pretending to look in their stomach [during the mock seal stomach dissection activity].” Around 20% of students also reported learning “how to scrape the fat off the skin” and how to age a seal using teeth. Students from the three communities mentioned having acquired knowledge about plankton: “We learned zooplankton live for only 20 days in water. We really enjoyed watching them swim around and using the tools [microscopes, pipettes].” Students also reported learning how to use a microscope and about seal anatomy, pollution, marine mammal sounds, as well as about the benefits and risks of ringed seal consumption. Several students also remembered that “ringed seals are good for you if they are not sick.”

Favorite workshop activities among students (n = 84) were: observing and feeding plankton (65%), ringed seal dissection (56%), Arctic food chain game (38%), ringed seal stomach dissection (27%), and ringed seal artwork (20%). Significant differences were observed when comparing favorite activities in relation to school level and amongst workshops (see details in Supplemental Material). In response to the survey question “Is there an activity that you did not like?” 92.5% of students who answered (37 out of 40) specified that they liked all the activities. Overall, 97% of students (57 out of 59) answered yes to the question “Where instructors easy to understand?” All students, except for one, reported instructors were interesting: “Yes, our presenters were awesome! Lots of fun to play with us in the gym and everything they were able to show and teach us.” Moreover, 24% (14 out of 59) reported that instructors were “fun.”

To the question: “What could researchers do better if they came to visit again?” 26% of students (22 out of 85) answered “nothing.” While students from Sachs Harbour and Arviat (second and third workshops) made almost no suggestions on how to improve the workshops, students from Resolute Bay (first workshop) suggested several improvements including: increasing the number of interactive activities and fun break times, adding videos on seals, and dissecting other species (e.g., polar bears, caribous, birds) (see Supplemental Material). Students from Arviat (12%; 10 out of 86) suggested improving the selection of local knowledge holders by “asking around the community and see who has more knowledge about animals.” Sachs Harbour students (4%; 3 out of 11) suggested that researchers learn more about the local culture: “Researchers seemed surprised that the people of Sachs Harbour do not eat very much seal meat. This seemed to throw them off.” Finally, 93% of students (51 out of 55) reported discussing with their family or friends about what they had learned during the workshops. Students from Sachs Harbour reported: “We shared what we learned with everyone at home: mom, nannak, brothers and aunties.”

Perspectives from project team instructors

Most instructors reported that the workshops benefited northern communities and southern-based researchers by creating strong working relationships between them: “I think meeting face-to-face with our project partners in communities is very important to build good working relationships, developing a sense of respect for and understanding of everyone’s perspectives and realities.” Another instructor reported: “Each time we have a positive interaction with community members, we are working towards a larger communal support of contaminants research in the North.” Other benefits frequently reported by instructors included: raising awareness about Arctic contaminants among Inuit communities, familiarizing northern youth to scientific concepts (e.g., bioaccumulation, biomagnification), and fostering intercultural and intergenerational sharing of Inuit knowledge. In addition, workshops allowed southern-based researchers to learn about Inuit culture, realities and concerns: “Communicating [research] results, answering questions, listening to [community] concerns are all important benefits to these meetings. Discussing about [northern] wildlife, environment, reality and living it, even for just a few days, makes everything more real and understandable.” Instructors also highlighted that the project enabled the engagement of Inuit students and communities in research, sharing research results and developing innovative communicating tools: “As instructors, we became better at communicating scientific concepts and developing material that is adapted to student needs and preferences.” Some instructors further reported that this community outreach project might help them become better researchers: “Meeting community members in person may create long-lasting relationships and help projects go in new and future directions. Being able to observe the specific sites of [scientific] research and learn from [community members] about the species also help understand the specific environment studied and interpret scientific data.”

According to all project team instructors, the overall workshop approach and activities were appropriate. A northern college student noted: “I applaud the preparation of this project. There was little to no aspect of it that I would change.” Five out of seven instructors highlighted the success of interactive activities: “The games were good for the students as they emphasized [concepts] we had presented to them [before].” Another instructor highlighted: “[An Elder] showed students how to prepare seal skin. A few girls liked this activity so much that they spent the afternoon taking blubber off the skin. The girls were so proud, concentrated and patient. It was beautiful to watch.” Similarly, Elders reported to instructors having appreciated the opportunity they had to share their knowledge with students. Three instructors also mentioned the importance of local school personnel in facilitating workshop planning and delivery: “The school science teacher was extremely helpful at facilitating communication between [the project team] and school staff. She helped us prepare everything and asked other teachers for their support and collaboration.” Involving Inuit Elders in the workshop was also highlighted by three instructors as very positive aspect of the workshops. An Inuk college student mentioned: “The Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit [Inuit knowledge] aspect should still be included in this program because it can reveal what may have been looked over by science.” Another instructor reported that playing games with students either before or after an activity was “a good way for [instructors] to bond with students and get know them to have a better feeling of the group before starting teaching.”

Some of the main challenges identified by instructors included: dealing with last minute changes (e.g., absence of Inuktut translator or Elders); engaging and maintaining student attention; adapting activities to the different age groups; and having to cancel the seal dissection (as a result of poor hunting conditions prior to the workshop in Sachs Harbour). Following the Sachs Harbour workshop, one instructor commented: “The timing [of our presentation] was fine, and the content appropriate, although the first part of the PowerPoint presentation was a little too formal and students lost attention very fast, unless we engaged them by asking questions and making the presentation more interactive […] The age difference was huge among students [from 4 to 14 years old] and it was difficult to find a way to transmit the information in a common way.” Ringed seal hunting being nowadays uncommon in Sachs Harbour, especially among younger generations, three instructors mentioned the difficulty of engaging students and keeping their interest about seal hunting. Another challenge for some instructors was their lack of training and preparedness to deal with behavior issues: “I tried to harness the energy of distracted students as much as I could, for example by asking the winner of an arm wrestle game to come help me read a slide, or by playing student games like 7 Up for a few minutes before beginning an activity […] A few times, I had to stop the activity I was doing to let the teacher handle behavior issues.” In addition, instructor feedback from the three workshops referred challenges associated with meaningful inclusion of Inuit knowledge in some activities: “As a southern-based researcher, I find including Inuit knowledge in the process challenging. When carrying the workshops, we are constrained with time and resources to generate a dialogue between Western science and Inuit knowledge, and there are language barriers.” Finally, organizing the workshops remotely and working with existing student science bases were also identified as challenges.

In the light of challenges identified after each workshop, project team instructors identified ways in which workshops could be improved. Some instructors believed that activities led by Elders could be further developed and expanded. Three instructors reported that more time should be spent with Elders to better plan the activities they engage in, but also to make sure that they have enough time to share stories with students. Furthermore, three instructors reported that it was important to manage student expectations related to the ringed seal dissection (e.g., not telling students in advance about the activity) in case a seal could not be harvested: “If hunting is unsuccessful as it was in Sachs Harbour, the disappointment [of students] is hard to overcome and makes it difficult to get them interested and have their attention.” Instructors also encouraged leaving materials such as posters and educational booklets with teachers so they can use them after the workshop, as well as better adapting workshop content to different age groups. Adding videos, integrating Inuktut in every activity, distributing notebooks and concluding the event with a final discussion were also suggested. Finally, an Elder who led a ringed seal dissection activity, suggested doing the seal butchering outside, a suggestion that was welcomed by instructors.

According to instructors, the quality of message delivery has improved between workshops, particularly because instructors “became better at communicating scientific concepts and developing materials adapted to student needs and preferences.” An early career researcher who was present in both Sachs Harbour and Arviat commented on how improvements were made between the two workshops: “We created more opportunities for students to do hands-on activities based on feedback received.” Finally, for future workshops, instructors suggested: sending to teachers a pre-workshop activity; preparing seal meat at school and invite community members for a feast; and organizing a meeting with the different workshop partners and participants, including school personnel, Elders and local organizations to discuss and improve the educational content.

Perspectives from school personnel

Overall, feedback received from school principals and teachers was positive. A school principal from Resolute Bay wrote:

Students enjoyed the workshop a great deal […] From my perspective, the students from grades 1 through 12 were very engaged in the presentations, and got much out of them. We are trying to raise awareness in students of science around us, and about how to become a scientist. As well, we are working to strengthen Inuktitut language skills in our students. The workshops helped with all three […] Having an Elder cut up the animal, with explanations, having our language teacher translate and focus on anatomy, and involving our older students in the dissection gave the students a good grounding. The follow-up presentations, activities, and interviews, were all viewed positively by students and staff.

After the Arviat workshop, an instructor reported:

The teachers I spoke to appreciated that we had age-appropriate material for many age groups and that we included Inuktitut materials they could work with. They also liked that we left some material for them to follow up with. Many of the adults and hunters I talked to in town were very pleased that we did the workshop at the school, and focused on activities for the kids.

Lastly, a principal emphasized the importance of ensuring that instructors took their time when introducing concepts and words that may be new to students. He suggested that “instructors repeat words such as “invertebrates,” “contaminants” or “bioaccumulation” many times during the workshop to make sure students learn and remember them.”

Perspectives from northern college students and early career researcher

The northern college student involved in the first and second workshops reported:

This workshop fits into the aspirations I have of becoming an advocate for Inuit, their welfare, their concerns of country food being impacted by climate change or development […] This workshop is pushing me toward my goal of going into office, where I can contribute positive changes to our environment, the welfare of wildlife in a world and future that is full of uncertainties.

The northern college student who participated in the third workshop highlighted “the importance of sharing [his experience with students] and learning continuously from Elders and community leaders.” He added that the workshop offered him an opportunity to exercise public speaking with school-aged students and interact with various NCP experts. Both college students highlighted that participating in workshops offered them a chance to network with northerners and southern-based researchers, as well to travel to Inuit communities where they had never been before.

The early-career researcher reported the workshops were an opportunity to combine her background in environmental education with her seal research skills:

I wanted to gain experience delivering outreach activities to northern communities that support my research. I have spent a couple of weeks each fall in Arviat [before joining the project] but felt that I could have a larger impact by going to the schools and speaking with the students […] It was a great experience talking about some of the work I do back in the lab and how the seals that their families have provided enables us to do research.

Discussion

Engaging Inuit school-aged students in environmental sciences

Student survey answers suggested that over 85% of students had acquired new knowledge or skills in the short term as a result of workshop engagement. However, our assessment methodology did not allow to track participant learning over a longer period of time. Tracking student learning over time is a challenge when studying the efficiency of science school projects, mostly due to capacity constraints (Clark et al., Citation2016). To our knowledge, no study has assessed to date the long-term (e.g., years) potential benefits of science outreach projects among Indigenous students, including Inuit. A study evaluating a two-week science summer camp for US middle school students indicated that, over the years, participating students maintained a more positive attitude toward science and a greater interest in science careers than those who did not participate (Gibson & Chase, Citation2002). Relatedly, US high school students who participated in a hands-on summer science program were more likely to do a career in science compared with students whose science first experience did not occur until university (Roberts & Wassersug, Citation2009). Thus, it may be logical to assume that, similarly, Inuit students who participated in our workshops could develop a more positive attitude toward science in the long term than those who did not. During our workshops, student participants had the opportunity to meet scientists in-person, which can help break stereotypes youth may have about science (Concannon & Grenon, Citation2016). Students also had the opportunity to learn about post-secondary education in environmental sciences through testimonies from Inuit college instructors.

Braiding knowledge systems

Our efforts to braid Inuit knowledge and Western science through science outreach and knowledge mobilization workshops can be situated within the wider landscape of inuitization and decolonization of education systems in Inuit Nunangat (Cram, Citation1985; McGregor, Citation2015), and more generally among Canadian Indigenous communities (Battiste & Youngblood-Henderson, Citation2009). Indeed, Canadian education systems have historically systematically excluded Indigenous cultures, values, knowledge, languages and ways of being in their curriculum leading to identity loss (Cram, Citation1985; McGregor, Citation2015). Although efforts have been deployed to develop education programs that are guided and informed by Inuit perspectives and worldviews, embedding Inuit knowledge in school programming has remained challenging particularly because of a lack of experience in engaging Inuit knowledge appropriately and effectively among educators (McGregor, Citation2015).

In this context, our workshops proposed activities aiming to promote exchanges among Inuit youth, Elders and hunters and scientists, and facilitate intergenerational and intercultural knowledge sharing (). Feedback received through the workshop assessment process emphasized the value of including both Inuit knowledge holders and scientific researchers as workshop instructors. Our experience also highlighted the importance of finding ways to facilitate meaningful Elder engagement in workshops activities, including: taking the time to establish a connection and trust between the project team and contributing Elders; carving enough space and time in workshop programming to make Elders feel comfortable; and ensuring adequate Inuktut-English translation support during all activities. Experienced Elders who are comfortable interacting with youth also have to be selected to support meaningful learning and knowledge sharing. In addition, Elder involvement in workshop preparation can decrease the stress that implies talking to a large group of students within a limited timeframe in a classroom setting, which differs from how Inuit knowledge is typically shared. Indeed, Inuit knowledge is generally transmitted on the land through observation (Karetak et al., Citation2017).

It is noteworthy that the top three topics students reported learning about involved Arctic food webs, contaminants and seal skin preparation. These three topics represent knowledge types that typically stem from Western science (i.e., contaminants), Inuit knowledge (i.e., seal skin preparation), or both (i.e., food webs). This demonstrates that students learned from multiple knowledge systems, and from multiple instructors in this workshop setting. Given the aim of presenting knowledge types together, and in context for student audiences, this suggests that co-taught workshops such as the ones presented here can be places of learning across knowledge systems. Our workshops provide an example where knowledge types are taught independently, but alongside each other, further modeling for students that multiple knowledge systems can be presented in parallel, while all being part of a larger holistic discussion, in this case around seal populations, health and traditional uses.

Finally, our experience illustrated that more efforts are still required to explain to students the power that lies in braiding Inuit knowledge and Western science to understand Arctic biodiversity, animal ecology as well as Arctic environmental changes. In the future, an idea we are interested in exploring to further support intergenerational learning and knowledge braiding in ringed seal monitoring would be to partner school students with local hunters – through local HTOs and with mentorship from scientists – in order for students to participate in seal hunts and document Inuit ecological observations during annual ringed seal sampling activities supported by the NCP. Such an initiative would involve teaching and learning about Inuit hunting skills and knowledge of the environment, which has proven to reinforce intergenerational relationships (Condon et al., Citation1995; Furgal et al., Citation2002). It could also be paired with existing community-based programs. For example, the Ujjiqsuiniq Young Hunters Program allows Inuit youth from Arviat to gain skills and knowledge related to sustainable harvesting practices by spending time and engaging in hunting activities with experienced Elders (see https://www.aqqiumavvik.com/young-hunters-program).

Identifying best practices for engaging with Inuit youth

Through our workshop experience and assessment process, we identified eight best practices for engaging Inuit youth and communities in environmental research through school workshops ().

Table 2. Summary of best practices for engaging Inuit youth in environmental research through school workshops as identified by workshop instructors, students and school personnel.

According to northern partners, a successful knowledge mobilization project must respect Inuit culture, involve local partners at each step of the project and propose culturally appropriate forms of communication and results dissemination (Brunet et al., Citation2014; Garnett et al., Citation2009; Inuit-Tapiriit-Kanatami & Nunavut-Research-Institute [ITK & NRI], Citation2003; ITK, 2018a; ITK & NRI, 2006). Thus, the approval and support of key local partners, particularly HTOs and school directors, are essential for the elaboration and implementation of school workshops in Inuit communities. Our experience illustrated that local schools and HTOs are uniquely positioned to support efficient project logistics. For example, school personnel can help with identifying and scheduling activities for their students. HTOs can also identify qualified and interested hunters, Elders and translators.

Another best practice identified through our workshops was to collect feedback from students and instructors through written surveys, and from school personnel and community members through emails or informal discussions, and then integrating these in the planning of the next workshop (). Globally, repeating the workshops and taking into account suggestions received improved the entire process, including the communication skills of instructors.

Importantly, our experience showed that workshop instructors need to have a flexible approach to workshop programming, including being able to adapt to last minute changes. Having extra activities at hand enabled our project team to make rapid changes to the program when needed. Visiting project team members also traveled to communities a few days before the workshops to ensure adequate engagement and planning with local partners. Having a qualified and diverse team of instructors with experience working with Indigenous youth and northern communities helped our team adapt to unexpected situations.

Alternating short presentations with interactive hands-on activities also proved to be a successful approach to workshop delivery. For example, playing games or conducting a hands-on activity right after a short presentation helped students assimilate scientific concepts. Interactive hands-on activities – such as observing and feeding plankton, conducting a ringed seal dissection and playing games in the gym – were the most appreciated activities among students who participated in the workshops. Similarly, inquiry-based approaches (i.e., learning from questions and action) and hands-on activities were found to be more engaging among US middle school students participating to science summer camps compared to lecturing (Gibson & Chase, Citation2002). Inquiry-based learning rather than memorization of facts, may indeed help students develop scientific curiosity, critical thinking and intellectual independence (Komoroske et al., Citation2015).

Adapting workshop activity content to audience diversity (e.g., age, language skills and group size) was identified as another key for success. Although our workshops included a diversity of activities, from an art activity that can be done by kindergarten students to a discussion on how to become a scientist for older students, most of the activities we developed were designed for middle school students. Our overall experience revealed that developing activities that are more targeted to specific ages and group sizes could help improve workshop content delivery. Furthermore, including Inuit post-secondary students – who shared the culture and language of workshop participants – in workshop planning and delivery helped create a sense of familiarity and proximity between students and our project team, and significantly contributed to ensuring that workshop content was adapted to our audience.

To support the continuous learning of concepts taught during workshops, educational material (e.g., posters, activity booklet) can be left with teachers. We found in this project that these were appreciated by the educators. This material needs to be easy to use by teachers and target specific age groups. Educational neuroscience demonstrated that knowledge is reinforced by using it a certain number of times, ideally through different ways (e.g., exercises, games, explaining to others) (Squire, Citation2009). Elaborating multiple activities on the same science concept in addition to leaving educational material with teachers may therefore support learning and the continuous use of knowledge acquired during the workshop.

It is important to recognize that most of the instructors who took part in our workshops were from southern Canada, and had varying levels of familiarity with Inuit culture. In our case, providing cultural awareness training opportunities to instructors could therefore ensure a better understanding of Inuit culture by non-Inuit instructors or Indigenous students coming from other communities. Inuit realities and dialects differ across communities; it is therefore important to obtain as much information as possible about the local culture before working in a community. One way to achieve this is by involving local partners in workshop content development. In addition to cultural training, most of our workshop instructors had limited training in education and pedagogy. As such, several aspects of the workshop, particularly maintaining the attention of students and managing behavior issues, represented a challenge for some instructors. Nonetheless, a few successful strategies were put in place by instructors, including playing with students a game of their choice before the activities, using humor, and asking students to assist instructors during activities. Having support and advice from teachers was essential in implementing these strategies, which highlighted the importance of collaboration between the project team and school personnel. Given that student misbehavior negatively impacts student learning and increases teacher stress (Clunies-Ross et al., Citation2008), introductory training on classroom management would be beneficial to all instructors involved in future workshops and would help nurture positive learning environments.

Fostering leadership among northern college and university students

Arctic researchers, including ECRs, often receive little-to-no formal training on how to respectfully and collaboratively conduct research with Inuit communities (MacMillan et al., Citation2019; Tondu et al., Citation2014). Including ECRs in this project helped introduce and train future Arctic researchers and establish a wider network of qualified researchers who are willing and able to conduct outreach workshops with northern communities. Similarly, Inuit youth often receive no formal training on how to interact and collaborate with researchers, although some written guidelines exist (ITK, Citation2018a; ITK and NRI, Citation2006). This is problematic as an elevated number of researchers annually visit northern communities to conduct research projects (Brunet et al., Citation2016). To provide part of this training, we enrolled two college students from the Nunavut Arctic College Environmental Technology Program as workshop instructors. Through their engagement in our project, these students worked in close collaboration with a team of researchers, learned about research on wildlife and contaminants, had an opportunity to engage with students, and met with various local organizations. College students also contributed to project presentations at national conferences, thus learning and expanding their own professional skill sets and networks through the project.

Expanding collaboration between northern residents and researchers

Knowing that effective communication and engagement between researchers and northern community members is central to the success and meaningfulness of environmental research projects conducted in the Canadian Arctic (Brunet et al., Citation2016, Citation2014; Henri et al., Citation2020; Sadowsky et al., Citation2022), proposing educational school projects might help Arctic research. Our experience showed that such projects can offer significant benefits for everyone involved (see ). Indeed, school projects not only provide opportunities to meet with local collaborators but also create space for less formal discussions about research projects. Southern-based researchers need to spend more time in northern communities to foster relationship-building with Indigenous and northern partners (Wong et al., Citation2020). While this commitment may be perceived as difficult to achieve by some researchers given the high costs of field research in remote Arctic areas (Brunet et al., Citation2014; Powell, Citation2007), such time may provide additional opportunities to truly and meaningfully partner with northern communities in research.

Table 3. Main workshop benefits according to instructors, students and school personnel.

Conclusion

Through this science outreach and knowledge mobilization project, we engaged Inuit youth and communities in research on ringed seals and contaminants. This work helped expand communication and collaboration between northern residents and scientific researchers, and supported training the next generation of northern environmental leaders. Best practices identified to optimize the success of outreach workshops stress the importance of developing a diverse project team, working closely with community partners, and being flexible and adaptable. Our experience also highlighted the need for adequate training for workshop instructors to help support student learning opportunities. Given the number of environmental challenges we are currently facing, supporting activities that increase scientific literacy and promote knowledge sharing across Indigenous and Western cultures is critical. The braiding of Indigenous and Western sciences through schools workshops offers a promising pathway to achieving this goal.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (5.5 MB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support and commitment of all the individuals and organizations who made this project possible. Thank you to: Jason Carpenter, Julia Landry, Daniel Martin and Mike Salomonie (Nunavut Arctic College in Iqaluit); Juanita Balhuizen and Doreen Hannak (Qitiqliq Middle School, Arviat); Tony Phinney, Jamie Kablutsiak and Joshua Gibbons (Levi Angmak Elementary School, Arviat); the Arviat Hunters and Trappers Organization; Peter Sanertanut, Julia Pingushat, Martha Pingushat (Arviat); Karen Bibby and Nicolas Kopot (Inualthuyak School, Sachs Harbour); Kyle Wolki (Sachs Harbour Hunters and Trappers Committee); Shannon O’Hara (Inuvialuit Regional Corporation); Kristin Hynes (Fisheries Joint Management Committee); Jeff Kuptana, John Keogak and Betty Haogak (Sachs Harbour); Rob Filipkowski and Kevin Xu (Qarmartalik School, Resolute Bay); the Resolute Bay Hunters and Trappers Organization; David Idlout, Peter Amarualik Sr., Zipporah Aronsen and Susan Salluviniq (Resolute Bay); Derek Muir, Amie Black, Maeva Giraudo and Michelle Sincennes (Environment and Climate Change Canada); Steven Ferguson and Brent Young (Fisheries and Oceans Canada); Chris Furgal (Trent University); Eric Loring (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami); David Yurkowski (University of Manitoba); and Julia Baak (McGill University). We also thank the Regional Contaminants Committees from the Northern Contaminants Program who provided valuable feedback on the project as the workshops were developed and implemented with partners. We also thank the reviewers for their constructive feedback on the manuscript prior to publication.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alexander, S. M., Provencher, J. F., Henri, D. A., Taylor, J. J., & Cooke, S. J. (2019). Bridging Indigenous and science-based knowledge in coastal-marine research, monitoring, and management in Canada: A systematic map protocol. Environmental Evidence, 8, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-019-0159-1

- Anhê, F. F., Varin, T. V., Le Barz, M., Pilon, G., Dudonné, S., Trottier, J., St-Pierre, P., Harris, C. S., Lucas, M., Lemire, M., Dewailly, É., Barbier, O., Desjardins, Y., Roy, D., & Marette, A. (2018). Arctic berry extracts target the gut-liver axis to alleviate metabolic endotoxaemia, insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in diet-induced obese mice. Diabetologia, 61(4), 919–931. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-017-4520-z

- Battiste, M., & Youngblood-Henderson, J. (2009). Naturalizing Indigenous knowledge in Eurocentric education. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 32, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- Berkes, F. (2012). Sacred ecology: traditional ecological knowledge and resource management (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Brunet, N. D., Hickey, G. M., & Humphries, M. M. (2014). The evolution of local participation and the mode of knowledge production in Arctic research. Ecology and Society, 19, 69. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06641-190269

- Brunet, N. D., Hickey, G. M., & Humphries, M. M. (2016). Local participation and partnership development in Canada’s Arctic research: challenges and opportunities in an age of empowerment and self-determination. Polar Record. 52(3), 345–359. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003224741500090X

- Canadian-Institutes-of-Health-Research, Natural-Sciences-and-Engineering-Research-Council-of-Canada, Social-Sciences-and-Humanities-Research-Council-of-Canada. (2018). Tri-Council policy statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans.

- Chilisa, B. (2012). Indigenous methodologies. Sage.

- Clark, G., Russell, J., Enyeart, P., Gracia, B., Wessel, A., Jarmoskaite, I., Polioudakis, D., Stuart, Y., Gonzalez, T., MacKrell, A., Rodenbusch, S., Stovall, G. M., Beckham, J. T., Montgomery, M., Tasneem, T., Jones, J., Simmons, S., & Roux, S. (2016). Science educational outreach programs that benefit students and scientists. PLOS Biology, 14(2), e1002368–8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002368

- Clunies-Ross, P., Little, E., & Kienhuis, M. (2008). Self-reported and actual use of proactive and reactive classroom management strategies and their relationship with teacher stress and student behaviour. Educational Psychology, 28(6), 693–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410802206700

- Concannon, C., & Grenon, M. (2016). Researchers: Share your passion for science! Biochemical Society Transactions, 44(5), 1507–1515. https://doi.org/10.1042/bst20160086

- Condon, R., Collings, P., & Wenzel, G. (1995). The best part of life: Subsistence hunting, ethnicity and economic adaptation among young adult Inuit males. Arctic, 48(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic1222

- Cram, J. (1985). Northern teachers for northern schools: An Inuit teacher-training program. McGill Journal of. Education, 20, 112–131.

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.2307/1523157

- Curren, M. S., Wania, F., Laird, B., & Lemire, M. (2017). Chapter 2: Exposure to contaminants in northern Canada, Canadian Arctic Contaminants Assessment Report IV. Human Health Assessment 2017. Government of Canada.

- Davidson-Hunt, I. J., & O’Flaherty, R. M. (2007). Researchers, Indigenous peoples, and place-based learning communities. Society & Natural Resources, 20(4), 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920601161312

- Druker-Ibáñez, S., & Cáceres-Jensen, L. (2022). Integration of Indigenous and local knowledge into sustainability education: A systematic literature review. Environmental Education Research, 28(8), 1209–1236. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2022.2083081

- Furgal, C. M. M., Innes, S., & Kovacs, K. M. (2002). Inuit spring hunting techniques and local knowledge of the ringed seal in Arctic Bay (Ikpiarjuk), Nunavut. Polar Research, 21(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-8369.2002.tb00063.x

- Garnett, S. T., Crowley, G. M., Hunter-Xenie, H., Kozanayi, W., Sithole, B., Palmer, C., Southgate, R., & Zander, K. K. (2009). Transformative knowledge transfer through empowering and paying community researchers. Biotropica, 41(5), 571–577. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7429.2009.00558.x

- Gearheard, S., & Shirley, J. (2009). Challenges in community-research relationships: Learning from natural sciences in Nunavut. Arctic, 60(1), 271–275. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic266

- Gibson, H. L., & Chase, C. (2002). Longitudinal impact of an inquiry-based science program on middle school students’ attitudes toward science. Science Education, 86(5), 693–705. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.10039

- Gould, W., González, G., Walker, D. A., & Ping, C. L. (2010). Commentary. Integrating research, education, and traditional knowledge in ecology: A case study of biocomplexity in Arctic ecosystems. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 42(4), 379–384. https://doi.org/10.1657/1938-4246-42.4.379

- Government-of-Canada. (2019). Species profile. Ringed seal. https://wildlife-species.canada.ca/species-risk-registry/species/speciesDetails_e.cfm?sid=347

- Gutwill, J., Hido, N., & Sindorf, L. (2015). Research to practice: Observing learning in tinkering activities. Curator: The Museum Journal, 58(2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.12105

- Hammill, M. O. (2018). Ringed seal: Pusa hispida. In B. Würsig, J. G. M. Thewissen & K. M. Kovacs (Eds.), Encyclopedia of marine mammals (3rd ed., pp. 822–824). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804327-1.00218-1

- Henri, D. A., Brunet, N. D., Dort, H. E., Odame, H. H., Shirley, J., & Gilchrist, H. G. (2020). What is effective research communication? Towards cooperative inquiry with Nunavut communities. Arctic, 73(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic70000

- Henri, D. A., Provencher, J. F., Bowles, E., Taylor, J. J., Steel, J., Chelick, C., Popp, J. N., Cooke, S. J., Rytwinski, T., McGregor, D., Ford, A. T., Alexander, S. M. (2021). Weaving Indigenous knowledge systems and Western sciences in terrestrial research, monitoring and management in Canada: A protocol for a systematic map. Ecological Solutions and Evidence, 2, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/2688-8319.12057

- Houde, M., Krümmel, E. M., Mustonen, T., Brammer, J., Brown, T. M., Chételat, J., Dahl, P. E., Dietz, R., Evans, M., Gamberg, M., Gauthier, M. J., Gérin-Lajoie, J., Hauptmann, A. L., Heath, J. P., Henri, D. A., Kirk, J., Laird, B., Lemire, M., Lennert, A. E., … Whiting, A. (2022). Contributions and perspectives of Indigenous Peoples to the study of mercury in the Arctic. The Science of the Total Environment, 841, 156566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156566.

- Houde, M., Taranu, Z. E., Wang, X., Young, B., Gagnon, P., Ferguson, S. H., Kwan, M., & Muir, D. C. G. (2020). Mercury in ringed seals (Pusa hispida) from the Canadian Arctic in relation to time and climate parameters. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 39(12), 2462–2474. https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.4865

- Houde, M., Wang, X., Colson, T. L. L., Gagnon, P., Ferguson, S. H., Ikonomou, M. G., Dubetz, C., Addison, R. F., & Muir, D. C. G. (2019). Trends of persistent organic pollutants in ringed seals (Phoca hispida) from the Canadian Arctic. The Science of the Total Environment, 665, 1135–1146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.138

- Houde, M., Wang, X., Ferguson, S. H., Gagnon, P., Brown, T. M., Tanabe, S., Kunito, T., Kwan, M., & Muir, D. C. G. (2017). Spatial and temporal trends of alternative flame retardants and polybrominated diphenyl ethers in ringed seals (Phoca hispida) across the Canadian Arctic. Environmental Pollution (Barking, Essex: 1987), 223, 266–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.01.023

- Ihaka, R., & Gentleman, R. (1996). R: A language for data analysis and graphics. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 5(3), 299–314. https://doi.org/10.2307/1390807

- Inuit-Tapiriit-Kanatami and Nunavut-Research-Institute. (2003). Negotiating research relationships: A guide for communities.

- Inuit-Tapiriit-Kanatami and Nunavut-Research-Institute. (2006). Negotiating research relationships with Inuit communities. A guide for researchers.

- Inuit-Tapiriit-Kanatami. (2018a). National Inuit strategy on research.

- Inuit-Tapiriit-Kanatami. (2018b). Inuit statistical profile.

- Johnson, J. T., Howitt, R., Cajete, G., Berkes, F., Louis, R. P., & Kliskey, A. (2016). Weaving Indigenous and sustainability sciences to diversify our methods. Sustainability Science, 11(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-015-0349-x

- Karetak, J., Tester, F., & Tagalik, S. (2017). Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit. What Inuit have always known to be true. Fernwood Publishing.

- Kelly, B. P., Bengtson, J. L., Boveng, P. L., Cameron, M. F., Dahle, S. P., Jansen, J. K., Logerwell, E., Overland, J. E., Sabine, C. L., Waring, G. T., & Wilder, J. M. (2010). Status review of the ringed seal (Phoca hispida). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce (NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC-212).

- Kimmerer, R. W. (2002). Weaving traditional ecological knowledge into biological education: A call to action. Bioscience, 52(5), 432–438. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2002)052[0432:WTEKIB]2.0.CO;2

- Koivura, T., Broderstad, E. G., Cambou, D., Dorough, D., & Stammer, F. (2020). Routledge handbook on Arctic Indigenous peoples in the Arctic (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning as the science of learning and development. Prentice Hall.

- Komoroske, L. M., Hameed, S. O., Szoboszlai, A. I., Newsom, A. J., & Williams, S. L. (2015). A scientist’s guide to achieving broader impacts through K-12 STEM collaboration. Bioscience, 65(3), 313–322. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biu222

- Kovach, M. (2021). Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, conservations, and contexts. Second edition University of Toronto Press.

- Lemire, M., Harris, C., Lucas, M., Cuerrier, A., Gauthier, M., Bouchard, A., Labranche, E., Alary-Vézina, P., Tardif, M., & Dewailly, É. (2014). From knowledge to action: Understanding wild berries health benefits to implement community-based interventions linking public health and social innovation in Nunavik. EcoHealth 2014, The 5th Biennial Conference of the International Association for Ecology and Health, Montreal, Canada, 11–15 August 2014. Northern Public Affairs, Special Issue 2014: 85–87.

- Li, S., & Smith, K. (2016). Inuit: Fact sheet for Inuit Nunangat. Minister of Industry, Statistics Canada, Social and Aboriginal Statistics Division. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/89-656-x/89-656-x2016014-eng.pdf?st=5EmOAFzH

- Ljubicic, G. J., Mearns, R., Okpakok, S., & Robertson, S. (2021). Learning from the land (Nunami iliharniq): Reflecting on relational accountability in land-based learning and cross-cultural research in Uqšuqtuuq (Gjoa Haven, Nunavut). Arctic Science, 40, 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1139/as-2020-0059

- Loveland, E. (2003). Acheiving academic goals through place-based learning: Students in five states show how to do it. Rural Roots, 4(1), 6–11.

- Lowry, L. (2016). Pusa hispida. The IUCN red list of threatened species 2016. http://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T41672A45231341.en

- MacMillan, G. A., Falardeau, M., Girard, C., Dufour-Beauséjour, S., Lacombe-Bergeron, J., Menzies, A. K., & Henri, D. A. (2019). Highlighting the potential of peer-led workshops in training early-career researchers for conducting research with Indigenous communities. Facets, 4(1), 275–292. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2018-0046

- McGregor, H. E. (2015). Decolonizing the Nunavut school system: Stories in a river of time. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of British Columbia.

- Moseley, C., Summerford, H., Paschke, M., Parks, C., & Utley, J. (2020). Road to collaboration: Experiential learning theory as a framework for environmental education program development. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 19(3), 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533015X.2019.1582375

- Muir, D., Houde, M., & Kruemmel, E. (2021). Involvement of Arctic Indigenous communities in POPs-climate change research. Arctic Monitoring Assessment Programme Climate Change and POPs Assessment, Tromsø, Norway.

- Pearce, T. D., Ford, J. D., Laidler, G. J., Smit, B., Duerden, F., Allarut, M., Andrachuk, M., Baryluk, S., Dialla, A., Elee, P., Goose, A., Ikummaq, T., Joamie, E., Kataoyak, F., Loring, E., Meakin, S., Nickels, S., Shappa, K., Shirley, J., & Wandel, J. (2009). Community collaboration and climate change research in the Canadian Arctic. Polar Research, 28(1), 10–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-8369.2008.00094.x

- Powell, R. C. (2007). Geographies of science: Histories, localities, practices, futures. Progress in Human Geography, 31(3), 309–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132507077081

- Provencher, J. F., McEwan, M., Mallory, M. L., Braune, B. M., Carpenter, J., Harms, N. J., Savard, G., & Gilchrist, H. G. (2013). How wildlife research can be used to promote wider community participation in the North. Arctic, 66(2), 237–243. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic4302

- R-Development-Core-Team. (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.r-project.org/

- Reeves, R. R., Wenzel, G. W., & Kingsley, M. C. (1998). Catch history of ringed seals (Phoca hispida) in Canada. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 1, 100. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.2983

- Roberts, L. F., & Wassersug, R. J. (2009). Does doing scientific research in high school correlate with students staying in science? A half-century retrospective study. Research in Science Education, 39(2), 251–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-008-9083-z

- Sadowsky, H., Brunet, N. D., Anaviapik, A., Kublu, A., Killiktee, C., & Henri, D. A. (2022). Inuit youth and environmental research: Exploring engagement barriers, strategies, and impacts. Facets, 7, 45–70. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2021-0035

- Squire, L. R. (2009). Memory and brain systems: 1969-2009. Journal of Neuroscience, 29(41), 12711–12716. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.3575-09.2009

- Taylor, M. E., & Boyer, W. (2020). Play-based learning: Evidence-based research to improve children’s learning experiences in the kindergarten classroom. Early Childhood Education Journal, 48(2), 127–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-019-00989-7

- Tengö, M., Hill, R., Malmer, P., Raymond, C. M., Spierenburg, M., Danielsen, F., Elmqvist, T., & Folke, C. (2017). Weaving knowledge systems in IPBES, CBD and beyond—lessons learned for sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 26-27, 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2016.12.005

- Tobias, J. K., Richmond, C. A. M., & Luginaah, I. (2013). Community-based participatory research (CBPR) with Indigenous communities: Producing respectful and reciprocal research. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 8(2), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1525/jer.2013.8.2.129

- Tondu, J. M. E., Balasubramaniam, A. M., Chavarie, L., Gantner, N., Knopp, J. A., Provencher, J. F., Wong, P. B. Y., Simmons, D., & Simmons, D. (2014). Working with northern communities to build collaborative research partnerships: Perspectives from early career researchers. Arctic, 67(3), 419–429. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic4416

- Vogel, L. (2015). The new ethics of Aboriginal health research. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 187(5), 316–317. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.109-4998

- Vossoughi, S., & Bevan, B. (2014). Making and tinkering: A review of the literature (Vol. 67, pp. 1–55). National Research Committee on Successful out of School Time STEM.

- Wenzel, G. (1991). Animal rights human rights: Ecology, economy and ideology in the Canadian Arctic. University of Toronto Press.

- Wilson, K. J., Bell, T., Arreak, A., Koonoo, B., Angnatsiak, D., & Ljubicic, G. J. (2020). Changing the role of non-Indigenous research partners in practice to support Inuit self-determination in research. Arctic Science, 6(3), 127–153. https://doi.org/10.1139/as-2019-0021

- Wilson, S. (2001). What is Indigenous research methodology? Canadian Journal of Native Education, 25, 166–174.

- Wong, C., Ballegooyen, K., Ignace, L., Johnson, M. J., & Swanson, H. (2020). Towards reconciliation: 10 Calls to Action to natural scientists working in Canada. FACETS, 5(1), 769–783. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2020-0005

- Wright, T. (2006). Feeling green: Linking experiential learning and university environmental education. Higher Ed. Persp, 2(1), 69–81.