Abstract

Calls for a common environmental education (EE) vision imply imposing certain values as universal. Nevertheless, there is a lack of knowledge on the extent to which EE reflects universalities versus diverse sociocultural realities. We explored practitioners’ perspectives on the purpose of EE by interviewing practitioners in Finland and Madagascar using a theory of change approach. We classified EE goals into eight categories following the framework of Clark et al. (Citation2020). We found signs of universal patterns, with commonalities such as the importance of the cognitive domain and de-emphasis of sociocultural aspects. Yet, differences arise: the connection to nature was central in Finland, whereas economic and bridging strategies were more common in Madagascar. Our results reflect the tradition of EE in post-industrial countries and suggest the influence of the colonial legacy and Western epistemologies in Madagascar. Questions remain about the extent to which those differences are culturally grounded.

Résumé

Pour une vision commune de l’éducation à l’environnement (EE), il faut imposer certaines valeurs comme universelles. On observe cependant un manque de connaissances sur la mesure dans laquelle l’EE reflète les universalités par rapport aux diverses réalités socioculturelles. Nous avons exploré les perspectives des praticiens sur l’objectif de l’EE en interviewant des praticiens en Finlande et à Madagascar, en utilisant une approche de la théorie du changement. Nous avons classé les objectifs d’EE en huit catégories, selon le cadre de Clark et al. (2020). Nous avons trouvé des signes évocateurs de modèles universels, avec des points communs, comme l’importance du domaine cognitif et la désaccentuation des aspects socioculturels. Pourtant, des différences apparaissent: le lien avec la nature était central en Finlande, tandis que les stratégies économiques et de transition étaient plus courantes à Madagascar. Nos résultats reflètent la tradition de l’EE dans les pays post-industriels et suggèrent l’influence de l’héritage colonial et des épistémologies occidentales à Madagascar. Des questions demeurent quant à la mesure dans laquelle ces différences sont fondées sur la culture.

Introduction

Environmental education (EE) is considered a key intervention to address the current environmental crisis (Reid et al., Citation2021). Responding to this global crisis, EE practitioners are committed to making the world a better place. From children to adults, and from classrooms to zoos and parks, EE embraces a range of topics, learner types, contexts, approaches, values, and ideologies (Rickinson & McKenzie, Citation2020). For some, this diversity can simultaneously play as a drawback. Clark et al. (Citation2020, p. 382) stated that a major obstacle to the overarching goal of EE is “reaching agreement on what constitutes a ‘better place’—or whom, under what conditions, and by what path or paths”.

The UNESCO Tbilisi Declaration (UNESCO, Citation1977) established that the ultimate goal of EE is to ensure people’s active participation in moving society toward the resolution of environmental problems. Since then, a multiplicity of perspectives have emerged, and groups and organizations have described different aims and priorities for EE (Salazar et al., Citation2021). At the same time, conservation organizations and intergovernmental agencies have defined frameworks to establish a common vision of EE; for instance, the WWF Global Environmental Education Programme (Huckle, Citation1988), the UNEP Strategy for Environmental Education and Training (UNEP, Citation2005), and the UNESCO Roadmap on Education for Sustainable Development (UNESCO, Citation2020). Similarly, policymakers and practitioners are concerned by the need of “scaling up”, moving education activities from a small to a larger impact, and finding generalizable solutions (Mickelsson, Citation2020).

However, many environmental educators hold the view that environmental stewardship is neither an innate nor universal value, but it depends on the context where it is learnt and taught (Reid et al., Citation2021). Along these lines, researchers question the idea of standard educational proposals designed for a diversity of countries, cultures, and peoples, as they imply risks of imposing concrete perceptions of the world and its problems as universal (De Andrade & Sorrentino, Citation2014). Given the complexity and multiple scales of current socioenvironmental challenges, one of the remaining key questions is how an initiative such as EE is implemented in practice in diverse local social, political, and cultural contexts (Larsen & Brockington, Citation2018) and whether EE programs are imposing universalized priorities, cultures, and themes (De Andrade & Sorrentino, Citation2014).

Up to date, the question of why we do EE remains largely unaddressed (Clark et al., Citation2020) and the few studies that include the views of practitioners focus exclusively on the perspectives of North American practitioners (Clark et al., Citation2020; Fraser et al., Citation2015; Salazar et al., Citation2021). To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies on this topic focus on EE practitioners in the Global South. Accordingly, the aim of this research is to examine whether the goals and priorities of EE differ in different contexts. To do so, we explore practitioners’ perspectives on the purpose of EE in two distinct countries: Finland as an example of a Global North country and global leader on education, and Madagascar as an illustration of a Global South country and a top global conservation priority. Specifically, the focus of this study is on the following research questions:

What are the goals of EE according to practitioners working in Finland and Madagascar?

What are the similarities and differences in the purpose of EE between Finland and Madagascar?

To what extent does the perceived purpose of EE reflect universalities, and to what extent does it reflect different sociocultural contexts?

Theoretical background

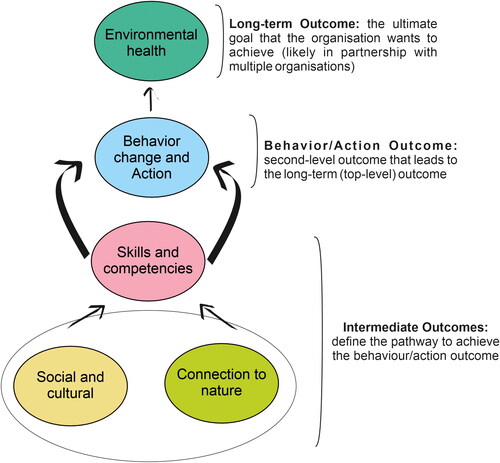

In this article, we draw on discussions about the goals and priorities of EE. While the Tbilisi and Belgrade documents from the 1970s are often core reference points, priorities have changed over decades (Reid et al., Citation2021). Thus, we consider as a starting point the article by Clark et al. (Citation2020) who presented that North American EE professionals and leaders came to agreement on the core outcomes for the EE field, described as: (1) environmentally related action and behavior change, (2) connecting people to nature, (3) improving environmental outcomes, (4) improving social/cultural outcomes, and (5) learning environmentally relevant skills and competencies. These five core outcomes have thereafter been acknowledged as an established EE framework by other researchers working in the USA and beyond (Bercasio, Citation2021; Bieluch et al., Citation2021; Dawson et al., Citation2022; Reid et al., Citation2021; Tolppanen et al., Citation2022). For this study, we operationalize core outcomes as a change in the environment or in people’s engagement with or actions on the environment. In particular, ‘core’ means it is a centrally important outcome of EE (Clark et al., Citation2020, p. 384). Thus, we use Clark’s conceptual framework as a tool to frame our analysis and discussion on the various core outcomes of EE.

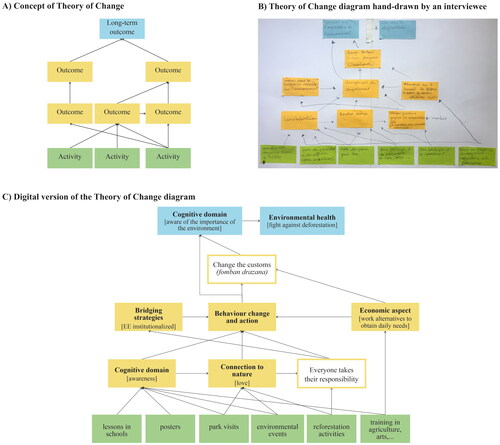

To identify the EE goals, we implement theory of change as a research tool. A theory of change (ToC) is an explanation of how and why an initiative generates a particular change (Belcher & Claus, Citation2020). Generally, a ToC is expressed as a diagram articulating a network of connections between activities, intermediate outcomes, and long-term outcomes, as exemplified in . This tool is widely applied in development organizations for strategic planning and program evaluation (Vogel, Citation2012), but it is less common in the field of EE. Inspired by the work of Krasny (Citation2020), we use the ToC as a research tool to identify how EE activities lead to outcomes.

Figure 1. A. Concept of theory of change (ToC): activities in green, intermediate outcomes in yellow and long-term outcome in blue (Adapted from Belcher & Claus, Citation2020). ToC is created using a backwards mapping process: first, the desired long-term goals; second, the intermediate outcomes; and third, the activities. After defining these three elements, the interviewees draw the arrows to connect the different variables, creating a complex web of assumptions about what needs to happen to bring about change (Center for Theory of Change, Citation2021); B. Example of a hand-drawn ToC diagram done by an interviewee; and C. Digital version of the same ToC, with the long-term and intermediate outcomes coded according to the classification matrix.

Finnish context

Finland is a post-industrial and urbanized Northern European country, and one of the most forested countries in Europe. Most forested areas are owned by private individuals or families and heavily used for logging, but public access to forests is guaranteed by jokamiehen oikeudet (everyone’s rights) that gives everyone the basic right to roam freely in the countryside, to camp for a short period, and to pick berries and mushrooms (Rantala & Puhakka, Citation2020). Old-growth forests are rare, and the species dependent on dead wood are particularly threatened (Blattert et al., Citation2022). Thus, sustainable forestry is one of the major environmental discourses in Finland.

Finland has a long tradition of EE both as a part of formal education, but also in semiformal and nonformal settings. The Finnish school system has a national curriculum for primary and secondary schools, which is adapted to the local context by the local organizers of the education (Finnish National Board of Education [FNBE], Citation2014, Citation2015). The very first national curriculum in the 1920s already included “ethics and morality” as a school subject, which covered topics such as “care for the nature” and “charity towards animals”, and emphasized the need for outdoor education, though mostly for the physical education and wholesomeness of the education (Kansakoulun opetussuunnitelmakomitea, Citation1925). The concept of “environmental education” was adopted quite quickly after the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm in 1972. The first documented use in a Finnish source was in a dissertation three years later (Leinonen, Citation1975).

EE in Finland is driven by a focus on young people. In 1985, EE was included as a transdisciplinary topic in Finnish primary and lower secondary school national core curriculum (FNBE, Citation1985). This status has remained ever since. After the 1990s, the emphasis has strongly been on sustainable development and the concept of biodiversity has emerged as an important bridging concept not only in biology, but also in other school subjects. Thus, currently, every school subject in primary and secondary school in Finland should contain something that can be described as EE.

Traditionally, both formal and nonformal EE have been seen as a responsibility of Finnish municipalities, and the forthcoming revised Nature Conservation Act is expected to formalize this (Finnish Ministry of Environment, Citation2021), which will probably strengthen the role of nonformal EE. In practical terms, several governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) run EE outside the school system. A substantial number of these, such as museums, zoos or nature schools, target their activities at schools, i.e., they are out-of-classroom settings for formal education, conforming to the national core curriculum. Also, these same organizations and additional organizations take part in nonformal EE. Additional organizations could include associations belonging to the scouting movement, youth organizations of nature conservation associations or other NGOs.

Malagasy context

Madagascar is widely renowned for its high biodiversity (Myers et al., Citation2000). Despite the country’s biodiversity wealth, Madagascar is ranked among the poorest countries and it is predominantly rural, where people rely on a combination of subsistence farming and non-timber forest products for their livelihoods (e.g. food, fuel, shelter) (Randrianarivony et al., Citation2016; Ward et al., Citation2018). Its unique biodiversity has attracted a lot of research and international donor attention (Waeber et al., Citation2016), that has translated into a network of protected areas as the main conservation strategy in the country (Waeber et al., Citation2019). Yet, Madagascar’s great share of endemic species is increasingly endangered due to anthropogenic disturbance (Schwitzer et al., Citation2014; Vieilledent et al., Citation2018), linked to political and social instability, weak governance and corruption (Jones et al., Citation2019; Ralimanana et al., Citation2022).

International actors have also influenced Madagascar’s educational agenda (Brias-Guinart et al., Citation2020). Since the 1970s, the Malagasy government has prioritized the integration of EE into its education and environmental policy, as a strategy to recognize the value of the country’s natural heritage. Since then, Madagascar has ratified several treaties and policy plans that emphasize the role of education, communication and awareness related to the environment. To mention a few: the National Policy on Environmental Education (ME & MINESEB, Citation2002), the National Education Policy on the Environment and Sustainable Development (MEF, Citation2013), Education Sector Plan (MEN, Citation2017). Additionally, EE has been defined as one of the priorities of the current Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development (Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement durable, Citation2020).

Despite these policy plans, little has been implemented into practice, and environmental and social-educational issues persist. As an example, a study by Heriniaina (Citation2013) found that exotic species are better known and preferred by schoolchildren than endemic species. Overall, EE strategies within the current Malagasy school system remain weak and EE is only marginally integrated into teacher training curricula (Niens et al., Citation2021). In practice, most EE interventions are conducted by nonformal education organizations: mostly NGOs (both national and international) (Brias-Guinart et al., Citation2020), but also by churches, civil society, and associations that contribute to raising awareness in various parts of Madagascar using a variety of tools and techniques.

Methods

The study context

In our study, we targeted EE practitioners to explore the purpose of EE in their organization. We focused particularly on governmental organizations and NGOs conducting nonformal EE programs throughout Madagascar and Finland. Due to the existing large differences in the status of EE in the formal school system between the two countries, we focused on nonformal education, as that gave better grounds for comparison. Additionally, nonformal organizations, as opposed to the formal school system, have more flexibility to adapt the content and teaching methods, which result in a greater diversity of perspectives and approaches that provide richer grounds for analysis.

We identified participants via snowball sampling (Browne, Citation2005). We conducted 31 interviews (15 in Madagascar and 16 in Finland). We included a representative sample of actors for both countries. The profile of actors conducting EE is different in the two countries (see Appendix S1). In Madagascar, they are mostly NGOs with a high number of foreign organizations. Funding is provided mainly by international foundations, as well as development agencies, zoos, and private donors. In Finland, on the contrary, most organizations are Finnish, and are a patchwork of zoos, museum, churches, companies, and associations. Funding comes substantially from public sources (from municipal to national ones), and from private funds. In Finland, we focused on organizations targeting people under 18 years of age. In Madagascar, although we did not select organizations based on that criterion, most represented organizations also target children and youth.

Data collection

We conducted the data collection during September-October 2019 (Madagascar) and May-October 2020 (Finland). In most cases, the interviews were one-on-one between facilitator and participant, lasting between an hour and a half, and two hours each. We asked participants to describe the views of the organization, rather than describing their own beliefs. In Madagascar, ABG did the interviews in English or French; in Finland, MH conducted them in Finnish. Throughout the research in both countries, we adhered to the standard ethical procedures of Free Prior and Informed Consent with each participant, and we followed the guidelines of the Finnish Advisory Board on Research Integrity. The research was approved by the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development of Madagascar (9 July 2019, 182/19/MEDD/SG/DGEF/DGRNE).

We created an interview protocol adapting the methodology detailed by LaMere et al. (Citation2020) (for more details on the full protocol, see Brias-Guinart et al., Citation2022). We conducted various pilot sessions and revised the protocol accordingly to ensure clarity and relevance across backgrounds and cultures. At the beginning of each session, the facilitator explained the ToC tool to the interviewees to ensure a similar level of understanding. The facilitator used three main questions to guide the process of drawing the ToC diagram (see ): What is the intended long-term outcome of your education program? Which intermediate outcomes will lead to your ultimate goal? Which education activities or interventions is your organization conducting? These questions were reiterated as needed until reaching saturation.

In dialogue with the facilitator, interviewees drew the diagrams themselves, ensuring co-ownership and transparency of the research process (Belcher et al., Citation2019). In addition, this methodology provided opportunities to engage in critical reflection and examine interviewees’ assumptions (Krasny, Citation2020), while avoiding possible social desirability bias (i.e., the tendency to give answers that make the respondent look good (Paulhus, Citation1991)). As a result, each ToC was formed by two elements: a diagram () and a narrative. The narrative was the transcription of the audio-recording during the interview to provide more detail on particular elements of the diagram.

Data analysis

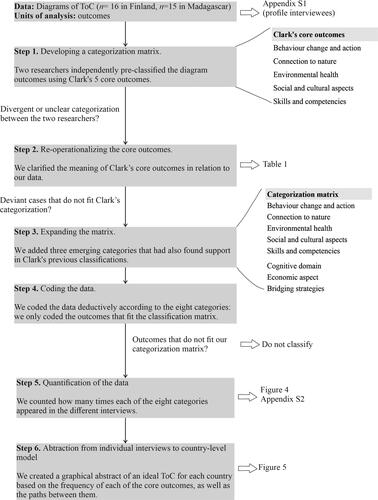

We were interested in identifying the goals of EE according to practitioners working in Finland and Madagascar. Our units of analysis were the outcomes as they appeared in the diagrams, supported by the transcripts of the interviews when clarifications about the written abstractions were needed and to extract quotes to illustrate the different categories. The data from the diagrams was translated into English. As explained before, the diagrams were drawn by the interviewees themselves and, for this reason, had their explicit acceptance.

We conducted a content analysis, deductively coding the diagram outcomes using Clark’s conceptual framework (). To do this, we included as our units of analysis outcomes recognized as either long-term or intermediate by the interviewees and we followed the steps described in . We did a first round of coding using Clark’s five core outcomes. After that, we expanded the categorization matrix, adding three emerging categories that had found support in Clark’s previous classifications. Then, we did a second round of coding the data with the eight categories (). Each of the steps of the data analysis was done in duplicate independently by two researchers (ABG and TA). After each step, the two researchers discussed potential disagreements and decided how to proceed on the following step. Yet, we acknowledge the outcomes are intertwined and connected, rather than exclusive from one another (Braus et al., Citation2022).

Figure 2. Interactions among the five core outcomes of environmental education (EE) (adapted from Clark et al., Citation2020) are represented here as a theory of change (based on Krasny Citation2020). This is just an abstraction of the five core outcomes, as not all EE programs focus on environmental quality as their long-term goal. For example, some may aim to increase skills and competencies as their ultimate outcome.

Figure 3. Methodology flow chart. The chart describes each of the steps of the data analysis, connecting them with the corresponding table and figures.

Table 1. Core outcomes (Adapted from Clark et al., Citation2020).

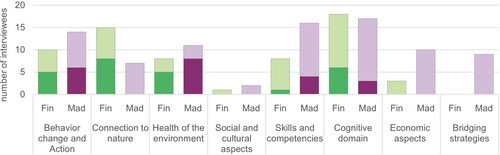

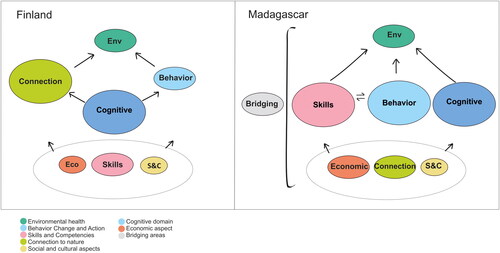

Once the outcomes were categorized, we counted how many times each of the eight categories appeared in different interviews (). Finally, to create a conceptual synthesis and contrast the two countries, we formed a consensus graphical abstract based on the frequency of each of the core outcomes, as well as the paths amongst them ().

Figure 4. Bar graph illustrating the number of interviewees (y axis) that mentioned at least once the outcomes classified into each of the eight categories (x axis), differentiated between Finland (green) and Madagascar (purple) and long-term outcomes (dark color) and intermediate outcomes (light color).

Figure 5. Core outcomes for environmental education in Finland (on the left) and Madagascar (on the right). The three different sizes of the bubbles indicate how often different interviewees mentioned that outcome (from small to big, less to more often). The top outcomes are the ones defined as long-term outcomes, whereas the bottom ones are the intermediate outcomes.

Trustworthiness

We reflect on the trustworthiness of this qualitative study by embracing some of the strategies advocated by Shenton (Citation2004). We chose ToC as a research methodology to ensure the credibility of our sampling, and to address possible reflexivity issues. Our mix of nationalities (Malagasy, Finnish and Spanish) allowed for prior understanding of the cultural context of both Finland and Madagascar. In addition, thanks to previous visits to Madagascar, we had developed an early familiarity with some of the participants. To allow transferability, we provide details on the context and boundaries of the study for the reader to decide whether the findings can be applied to another setting. At the same time, the detailed methodological description enables understanding of the methods and their effectiveness (dependability). Finally, we acknowledge the limitations of our research and that the positionality and values of the authors — trained in ecology and conservation research — had certain impacts on the data collection process and subsequent data interpretation (confirmability).

Findings

EE core outcomes for practitioners in Finland and Madagascar

We classified the outcomes mentioned by the interviewees into eight different categories as the core outcomes of EE, five of them corresponding to Clark’s framework, complemented by three additional ones that we identified. While in most cases the diagrams were sufficient to code the outcomes and classify them, transcripts were used to clarify a few entries. For example, the outcome “the restoration” could be referring to a change that should happen in the community (behavior change and action) or in the environment (environmental health). After looking at the transcript, “there will be a day when the local community will be aware of the importance of the ecosystem and they will be themselves who will do the restoration of the abandoned rice fields” (Interviewee M10), we coded the outcome as behavior change. The outcomes fit under the same main categories in both countries. Yet, there were clear differences in content for some of the categories, as described next.

Category 1. Behavior change and action

This category ranged from concrete environmental actions (e.g., planting trees, restoring a natural habitat), to behavior change in general or to more sustainable lifestyle.

Finnish interviewees described a shift to a sustainable lifestyle:

We think of it as education for a sustainable way of life. So, these actions that we have, for example, to prevent climate change, that they would be part of everyday habits. In other words, what we strive for is that these actions, the concrete things, would be part of everyday, normal life (Interviewee F8).

The local communities are still dependent on the natural resources, they cut the forest, collect firewood, cut the trees for the house constructions, … so we try to change their behavior, to be good citizenship like, “ok, it is not allowed to do this, and this and this” (Interviewee M12).

Category 2. Connection to nature

The outcomes classified to this category differed between Finnish and Malagasy interviewees.

Finnish interviewees commonly mentioned fostering a positive relationship toward nature. Other outcomes mentioned were appreciation, care and respect of nature:

Forming some kind of relationship with nature that usually comes after spending time in nature, or some kind of remarkable experience …. That relationship adds somehow to their understanding that we are part of nature, and what pristine nature still exists in Finland (Interviewee F10).

Nevertheless, both Finnish and Malagasy interviewees mentioned that the connection to nature appears after spending time in the forest. As one interviewee said:

I think is different because if they just go at the education center, and then we give them theory, they just imagine what they are trying to protect, but if we invite them to visit the park, they have in mind that they are protecting something real, concrete things, I think that’s it (Interviewee M4).

Category 3. Environmental health

This category encompassed outcomes such as improving the status of particular species or ecosystems (e.g., lemurs, insects, forest), securing the well-being of nature in general, and reducing environmental pressures. One participant described: We have two goals: one is to increase forest cover, to recover half of what was lost, and the other one is to remove those species from critically endangered” (Interviewee M9). In Madagascar, common environmental threats were deforestation, gold mining, and poaching.

In Finland, pressing environmental concerns were the use of natural resources, climate change, food waste, and landfill waste.

Category 4. Social and cultural aspects

We included all the outcomes that referred to a benefit for the community or wider society in this category.

In the Finnish interviews, it was mentioned only once as “striving for common good”: We try to teach that when everyone has as much everyone else, it is good for everyone” (Interviewee F9).

In the Malagasy ones, it related to improved governance of natural resources by increasing the participation of local communities in conservation actions: The local communities should be involved in the protection of the forest … For example, they should be members of the VOI [community-based natural resource management association], guides, forest patrol…” (Interviewee M12).

Category 5. Skills and competencies

We defined skills and competencies broadly. Skills ranged from social and leadership skills to action competence skills to preserve the environment, including also scientific skills and outdoors skills. In addition, many interviewees mentioned enhancing a sense of agency, as well as empowering children, youths, and local communities to become environmental agents related to the management of their own natural resources, or sustainable development in general:

One of our goals is that they [kids and other target groups] will have skills, that they are motivated and empowered to act, that they are the ones who act themselves, but also affect their local environment in their own communities, so that change happens (Interviewee F12).

In Madagascar, agency was connected to empowering local communities to become future actors and leaders in biodiversity conservation.

So that in the future the EE program is fully implemented, but also that one day there is no need for our NGO anymore, and they would be teaching their own children or other children. So that they become the next generation of conservationists and rangers protecting their forest (Interviewee M2).

Category 6. Cognitive domain

Most interviewees included the cognitive domain as a core outcome. For instance, 13 out of 16 interviewees in Finland, and 14 out of 15 in Madagascar mentioned at least one cognitive outcome as either long-term or intermediate. Thus, we decided to include the “cognitive domain” in our classification matrix, even if Clark et al. (Citation2020) had defined the programs focusing on environmental knowledge as foundational (i.e. that support core outcomes). This category ranged from access to information, expanding knowledge and understanding (including critical thinking), to increase awareness of environmental topics. As one interviewee mentioned: “Learning is not just about acquiring knowledge, but it is also understanding the connections, understanding the importance of insects, for example” (Interviewee M13). Some organizations focused on particular species (e.g., large carnivores, insects, lemurs), whereas others spoke generally about biodiversity, nature or the environment.

Category 7. Economic aspect

We included this category in our matrix as economic outcomes were a common occurrence in Malagasy ToC diagrams. In the Malagasy context, these were linked to access to alternative livelihoods: “The local communities should have access to alternative solutions that avoid the dependence on the forest (…): for the food, for the house and for fuel” (Interviewee M12).

While rare in the Finnish interviews, it appeared related to circular economy and work-life experiences.

We train new entrepreneurs in the themes of circular economy. … The underlaying idea is that in future there is no environmental experts but every worker should be the environmental expert in their company” (Interviewee F8).

Category 8. Bridging strategies

Similarly to the previous one, outcomes related to bridging areas were one of the differentiating factors between both countries, as no Finnish interviewees mentioned outcomes in this category, but they were mentioned by more than half of the interviewees in Madagascar (see Appendix S2). We included in this category outcomes that would typically not be considered as EE outcomes (e.g. Ardoin et al., Citation2020)—articularly in Global North settings—but that may be seen as critical in parts of the world with high biodiversity and harsh societal conditions (Padua, Citation2010, Brias-Guinart et al., Citation2022).

Malagasy interviewees described outcomes related to human health (including family planning and hygiene practices), access to studies and literacy, law enforcement, and institutionalization of EE through government and non-governmental means. For example, related to human health, one interviewee said:

[The park] is experiencing much higher disturbance …, and one of the main reasons is that there is a much larger human population around the park. … The population growth rate in Madagascar is not sustainable currently, but more importantly, women repeatedly inform us on their difficulties in obtaining family planning services. And that is why now we have established a very active family planning program (Interviewee M8).

Talking about access to education, one interviewee said:

We have a program that focus specially in giving scholarships to students, so they can go to school for longer time, so they can have a job, rather than fishery, so they can escape from fishing, and they can become actors and leaders from their community to make a change in the environment (Interviewee M15).

When people see that someone has broken the rule, but he is not punished, then they say, since there is no punishment, why I am not doing the same thing? So that is why we are working on the law enforcement as well with the education (Interviewee M9).

We [our organization] try to support the civil society that works in Education for Sustainable Development to collaborate with the government to develop the curriculum that integrates the sustainability dimension. Here the youth are not direct actors, but at the end of the day, that benefits youth. If they are still at school, they will learn what sustainability is, what they need to do to protect the environment, and all that, so that can help them to become, in long-term, direct actors (Interviewee M6).

Similarities and differences between Finland and Madagascar

We found clear indications of generalized differences between countries both in the frequency of each of the core outcomes (), and the paths amongst them (). Yet, some similarities appeared across the two countries as well. For individual answers for each organization, refer to Appendix S2.

In terms of long-term outcomes, behavior change and health of the environment were common in both countries. No interviewee mentioned social and cultural aspects, economic aspects and bridging strategies as long-term outcomes. Connection to nature was the most common long-term goal in Finland, whereas none of the Malagasy interviewees’ long-term outcomes were classified as such ().

In terms of intermediate outcomes, those in common for both countries were cognitive domain, connection to nature, behavior change and health of the environment. Yet, Madagascar had a greater diversity of intermediate outcomes, with outcomes in all eight categories, whereas Finland had few economic, social and cultural outcomes, and no bridging strategies. Skills and competencies was much more common as an intermediate outcome in Madagascar than in Finland.

When we articulated the core outcomes as a ToC (), the paths amongst the outcomes become apparent. As in Clark’s framework, environmental health remained the ultimate goal in both countries (, on the top). Just below this one, behavior change and cognitive domain were long-term outcomes for both countries. In the case of Finland, connection to nature was also an important long-term outcome—even more common than behavior change—whereas that remained an intermediate outcome in the case of Madagascar. On the contrary, skills and competencies were prioritized as a long-term outcome in Madagascar. In both countries, economic, and social and cultural outcomes remained as intermediate outcomes (, on the bottom). Madagascar had one extra outcome: bridging strategies, which intersect and find synergies with all other outcomes.

Discussion

Our research illustrates the similarities and differences in the purpose of EE amongst practitioners from a Global North and a Global South country: Finland and Madagascar. The classification of practitioners’ answers from both countries mostly fit with Clark’s framework on the core outcomes that focus the EE field (). Thus, our results reflect, to some extent, a general universal pattern on the core outcomes for EE. However, when we take a closer look at our results, differences arise: even if the categories were the same between the two countries, they include a spectrum of concepts and understandings.

The two countries present a very distinct institutional landscape in terms of EE and natural resources. Yet, some commonalities emerged on the importance of core outcomes (). We next discuss the extent to which the goals and priorities of EE reflect the different sociocultural contexts of both countries.

Surprisingly, the cognitive domain was a common outcome for most of organizations in both countries, despite differences in the history and institutionalization of EE. We anticipated that the cognitive domain would be more relevant in Malagasy organizations, as those organizations fill in the gaps of the formal school system, whereas we expected that Finnish organizations would not focus as much in the cognitive domain, as that is already included in the school curriculum.

Emphasis on the cognitive outcomes may be tied to the expectation that increased knowledge and awareness will lead to environmentally responsible behavior (Price et al., Citation2009). Cognitive outcomes are often used as indicators of success in impact evaluations (Thomas et al., Citation2019) and thus, the focus on cognitive outcomes may be influenced by the requirements of accountability between organizations and funders. Donor appraisals tend to focus on tangible and easily quantifiable measures of success and failure (Ebrahim, Citation2002). At the same time, organizations may see cognitive outcomes as “objective measures” that offer the opportunity to prove to funders the effectiveness of their programs (Sherrow, Citation2010). This is particularly relevant in contexts where education programs are dependent on external (and often limited) sources of funding, such as the case of Madagascar (Reibelt et al., Citation2017). Interestingly, North American practitioners in Clark’s study did not rank the cognitive domain as one of their top five outcomes. This rationale aligns with the literature that suggests that, even if knowledge is a necessary component to foster environmental literacy (Hollweg et al., Citation2011), it is rarely sufficient and independent to lead to behavior outcomes (Schultz, Citation2002).

Furthermore, the emphasis on the cognitive domain relates to an instrumental approach of EE, often associated with formal education, that focus on the transmission of scientific knowledge to change behaviors and solve environmental problems (Fraser et al., Citation2015) . By contrast, we anticipated that our results would rather reflect transformative learning approaches, as those are easily adopted in nonformal settings, which are commonly not limited by national curriculum policies (Reid et al., Citation2021). The collaboration with the formal school system may explain the contradiction. Organizations providing EE both in Finland and Madagascar commonly take part in the formal education, which focuses on cognitive aspects. For example, in Finland, pupils might go to the zoo as part of a school trip. In the case of Madagascar, even if the connection with the national curriculum is looser, organizations often work in collaboration with local teachers and public institutions, teaching lessons during or after school, integrating their activities with the formal curriculum (Dolins et al., Citation2010). Accordingly, the results in Finland and Madagascar may reveal that formal school institutions may be outsourcing EE, allocating it to nonformal organizations, which design their interventions conforming to the national curriculum.

One of the differentiating factors between the two countries was the focus on economic outcomes and other bridging strategies by organizations working in Madagascar, whereas those were rarely mentioned in Finland. An explanation for this broader understanding of EE in Madagascar may be the tight connection between conservation and development. In Madagascar, EE initiatives are mostly implemented by conservation NGOs (Brias-Guinart et al., Citation2020), which are constantly reshaping their initiatives responsive to project funding and shifting sociocultural dynamics (Larsen & Brockington, Citation2018). In this sense, the conservation agenda in Madagascar, as in other Global South countries, is strongly linked with development, and the international donor community has long provided aid in an effort to balance conservation and poverty alleviation (Waeber et al., Citation2016). On the one hand, this approach attempts to address the power imbalances and the mismatch between who benefits and who bears the costs of the use of natural resources, which is particularly aggravated in countries like Madagascar. On the other hand, NGOs work to counteract natural resource dependency by providing access to alternative livelihoods, which was frequently mentioned during the interviews. Likewise, Malagasy interviewees provided a stronger emphasis on skills and competencies as one of the core outcomes of EE. In this sense, engaging in activities like reforestation programs can increase participants’ professional skills, which may eventually improve their economic situation (Pohnan et al., Citation2015).

Another differentiating factor was connection to nature, which was much more central and frequently mentioned by Finnish practitioners than Malagasy ones. The results regarding the Finnish practitioners align with the large body of research that argues that a greater connection to nature is needed to develop environmental consciousness and intrinsic motivation to foster pro-environmental behaviors (Whitburn et al., Citation2020). Calls to promote direct experiences in nature as a response to anthropogenic degradation are characteristic of life in post-industrial and urbanized societies—such as Finland (Fletcher, Citation2017). In fact, most studies suggesting the importance of connection to nature are conducted in Western countries (Whitburn et al., Citation2020). So, if the concept of connection to nature is embedded in Western countries, to what extent it is relevant in a Malagasy context?

Most Malagasy people do not have the opportunity to visit natural protected areas due to financial constraints, with the exception of fieldtrips organized during university courses or by NGOs (Reibelt et al., Citation2017). Ironically, Madagascar’s biodiversity is an international selling point and most international tourists in the country visit natural protected areas. At the same time, local communities living close to those protected areas are, according to the interviewees, commonly lacking that “connection to nature”. This may be a consequence of a model of fortress conservation. Historically, the establishment of protected areas has failed to fully consider the needs of local communities who directly depend on natural resources for their wellbeing, and their access to natural resources has often been limited to areas outside protected areas (Vuola & Pyhälä, Citation2016). Despite an increasing shift toward a conservation model with shared governance in which sustainable uses are permitted (Gardner et al., Citation2018), the strict, centrally governed model still remains prevalent in Madagascar and in many other Southern countries. Under this colonial legacy of conservation that has led to the denial of access to nature, attempts to “reconnect” local communities to that same nature seem paradoxical.

These reflections connect with different interpretations of the value of nature. As mentioned earlier, environmental stewardship is not a universal value (Reid et al., Citation2021), and nature is perceived and valued in different, and often conflicting, ways (Pascual et al., Citation2017). Yet, most interviewed practitioners in both countries referred to “nature” as a separate entity from humans and society (Fletcher, Citation2017), connected to the Western nature/culture dichotomy (Strathern, Citation1980). Thus, while conservation discourses often emphasize the value of biological diversity, rural Malagasy people may see the forest as being essential for their dietary requirements, their health and a resting place for their ancestors (Fritz-Vietta, Citation2016; Scales, Citation2012). Similarly, in the case of Finland, Finnish people may appreciate nature for its potential for commercial forestry, or for outdoor recreation activities such as leisure hunting, skiing or spending time at a recreational home (mökki) (Rantala & Puhakka, Citation2020).

The scarcity of sociocultural outcomes in our results further illustrates this ecological perspective of EE. Our expectations were that social and cultural outcomes would be more prevalent, as natural resource management in both countries is strongly connected with their sociocultural heritage, for instance, the free access to and recreational use of forests in Finland (Parviainen, Citation2015) or the extended tradition of collection and consumption of medicinal plants in Madagascar (Randriamiharisoa et al., Citation2015; Razafindraibe et al., Citation2013). Our results are in line with previous studies that recognize the lack of an integrated socioecological approach to EE (Jenson, Citation2021). In addition, these findings provide support to the claims that EE requires a complex understanding of the socioecological systems (Ardoin et al., Citation2020), recognizing the need to engage with values, politics, and other social dimensions (Bennett et al., Citation2017). On these same lines, we suggest considering approaches such as place-based education that would provide opportunities for contextualized learning, being grounded in local resources, themes, and values (Velempini et al., Citation2018). At the same time, sense of place encompasses a holistic view of place, incorporating not only a biophysical perspective but also embracing psychological, sociocultural, political, and economic systems (Ardoin, Citation2006).

Limitations of the research

Our choices in our research approach led to some limitations in this study. Firstly, while it would be beneficial to compare similar organizations between countries, this is not likely to be possible as the operation of EE organizations varies widely between countries. Secondly, the scope of this study is limited to between-country comparisons and future studies would benefit from examining within countries differences. Thirdly, while the core curriculum in both Madagascar and Finland is highly centralized and at the national level, some of the EE organizations are local. Thus, regional differences within countries might partly drive the differences. Fourthly, in the case of Madagascar, most interviewees were highly educated individuals, living in the capital Antananarivo, who were accustomed to work with international collaborators and organizations. Thus, being interviewed by a non-Malagasy researcher might not be optimal for understanding the relationship between their traditional and local sensitivities, and more Western-centric views. Fifthly, we inquired about the practitioners’ perceptions of the intended outcomes of their organizations, and we did not ask about effectiveness and impact, or whether their personal opinions on EE objectives differed from the organizational ones. How closely aligned practitioners’ personal opinions are to those of the organization might also differ between organizations, and how much they have an opportunity to shape EE practices and goals in their organization.

A better place for whom?

Overall, our research provides insights into the debates on why we do EE, being one of the first attempts to illustrate the perspectives of EE practitioners beyond North America. Some questions remain unanswered: while there are different perspectives across practitioners in Finland and Madagascar, are those differences culturally grounded? To what extent do they reflect different needs, different contingencies and different contexts? Environmental organizations pride themselves on using EE as a meaningful approach to make this world “a better place”. But a better place for whom?

In general, our results for both countries reflect the tradition of EE in post-industrial countries, where EE has historically focused on conservation and natural resource management issues (Padua, Citation2010), failing to account for the complexity and nuances of socioecological systems (Ardoin et al., Citation2020). Yet, the inclusion of aspects of human health and livelihoods in the Malagasy context reflects a broader understanding of EE. In addition, organizations providing nonformal education are conditioned by the structure of the formal curriculum, which is less flexible in terms of scope and approaches, and strongly focused on the cognitive domain. In the case of Madagascar, EE is influenced by funders, Western epistemologies on nature/people relationships, international development goals, and a colonial legacy of biodiversity conservation, rather than local cultural contexts. Nevertheless, our results also support alternatives to the instrumental tradition of EE: some interviewees mentioned skills to empower youths and adults to become environmental agents for the management of their own natural resources, and improved governance of natural resources as one of their social and cultural outcomes. This perspective aligns with an emancipatory role of EE that focuses on empowering communities, and enhancing sense of agency and emancipation (Sauve, Citation2005; Wals et al., Citation2008). Moreover, it connects with the concept of justice as a key component of EE’s identity (Rodrigues & Lowan-Trudeau, Citation2021).

The outcomes of our study further question the idea of a universal agenda for education and add to the recognized need for decolonization of EE programs (McLean, Citation2013; Root, Citation2010; Velempini et al., Citation2018). Similarly, our findings encourage educators to question the uncritical or decontextualized use of EE tools and frameworks and, instead, endeavor to establish programs that are environmentally and culturally appropriate (Monroe & Krasny, Citation2016). Therefore, differing from Clark et al. (Citation2020) who considered the diversity of views of EE to be a roadblock, we embrace diversity of EE as a richness—and almost as a need. In line with others, we claim that successful EE interventions –both in the Global North and South—should be embedded in the people and their environment, and must be grounded in the sociocultural context, recognizing and working with place-based values and local understandings of natural resource use.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, ABG, TA and MC; Methodology, ABG; Validation, ABG, TA, MH and RH; Formal Analysis, ABG and TA.; Investigation, ABG and MH; Data Curation, AB-G; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, ABG; Writing—Review & Editing, ABG, TA, MH, RH and MC; Visualization, ABG.; Supervision, MC; Project Administration, ABG.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (43.3 KB)Acknowledgments

We particularly thank all the participants in Finland and in Madagascar that shared their time with us, and S. F. Nunes and S. R. M. Pentikäinen for kindly providing their feedback on the Finnish interview protocol. We further thank A. K. Haukka and S. Jovero for insights on the Finnish context, A. Kervinen for thoughtful comments on latter versions of the manuscript; and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

References

- Ardoin, N. M. (2006). Toward an interdisciplinary understanding of place: Lessons for environmental education. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education (CJEE), 11(1), 112–126.

- Ardoin, N. M., Bowers, A. W., & Gaillard, E. (2020). Environmental education outcomes for conservation: A systematic review. Biological Conservation, 241(108224). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108224

- Belcher, B., & Claus, R. (2020). Theory of change. Td-net toolbox profile. Swiss Academies of Arts and Sciences: Td-Net Toolbox for Co-Producing Knowledge, 5. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3717451

- Belcher, B., Claus, R., Davel, R., Jones, S., & Ramirez, L. (2019). Research theory of change. A practical tool for planning and evaluating change-oriented research. Sustainability Research Effectiveness. https://researcheffectiveness.ca/additional-resources/

- Bennett, N. J., Roth, R., Klain, S. C., Chan, K. M. A., Clark, D. A., Cullman, G., Epstein, G., Nelson, M. P., Stedman, R., Teel, T. L., Thomas, R. E. W., Wyborn, C., Curran, D., Greenberg, A., Sandlos, J., & Veríssimo, D. (2017). Mainstreaming the social sciences in conservation. Conservation Biology, 31(1), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12788

- Bercasio, R. R. O. (2021). Assessment of practices in integrating environmental education in the teacher education program. Randwick International of Education and Linguistics Science Journal, 2(4), 625–636. https://doi.org/10.47175/rielsj.v2i4.359

- Bieluch, K. H., Sclafani, A., Bolger, D. T., & Cox, M. (2021). Emergent learning outcomes from a complex learning landscape. Environmental Education Research, 27(10), 1467–1486. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2021.1947985

- Blattert, C., Eyvindson, K., Hartikainen, M., Burgas, D., Potterf, M., Lukkarinen, J., Snäll, T., Toraño-Caicoya, A., & Mönkkönen, M. (2022). Sectoral policies cause incoherence in forest management and ecosystem service provisioning. Forest Policy and Economics, 136, 102689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2022.102689

- Braus, J. A., Heimlich, J. E., Ardoin, N. M., & Clark, C. R. (2022). Building bridges, not walls: Exploring the environmental education ecosystem. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 21(4), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533015X.2022.2115226

- Brias-Guinart, A., Korhonen-Kurki, K., & Cabeza, M. (2022). Typifying conservation practitioners’ views on the role of education. Conservation Biology. 36(4), e13893. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13893

- Brias-Guinart, A., Pyhälä, A., & Cabeza, M. (2020). Linking biodiversity conservation and education: Perspectives from education programmes in Madagascar. Madagascar Conservation & Development, 15(1), 35–39.

- Browne, K. (2005). Snowball sampling: Using social networks to research non‐heterosexual women. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000081663

- Center for Theory of Change. (2021). How does theory of change work? Center for Theory of Change. https://www.theoryofchange.org/what-is-theory-of-change/how-does-theory-of-change-work/

- Clark, C. R., Heimlich, J. E., Ardoin, N. M., & Braus, J. (2020). Using a Delphi study to clarify the landscape and core outcomes in environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 26(3), 381–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1727859

- Dawson, V., Eilam, E., Tolppanen, S., Assaraf, O. B. Z., Gokpinar, T., Goldman, D., Putri, G. A. P. E., Subiantoro, A. W., White, P., & Widdop Quinton, H. (2022). A cross-country comparison of climate change in middle school science and geography curricula. International Journal of Science Education, 44(9), 1379–1398. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2022.2078011

- De Andrade, D. F., & Sorrentino, M. (2014). Dialogue as a basis for the design of environmental pedagogies. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 8(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973408214548373

- Dolins, F. L., Jolly, A., Rasamimanana, H., Ratsimbazafy, J., Feistner, A. T. C., & Ravoavy, F. (2010). Conservation education in Madagascar: Three case studies in the biologically diverse island-continent. American Journal of Primatology, 72(5), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20779

- Ebrahim, A. (2002). Information struggles: The role of information in the reproduction of NGO-funder relationships. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 31(1), 84–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764002311004

- Finnish Ministry of Environment. (2021). Luonos hallituksen esitykseksi luonnonsuojelulaiksi (Draft for the governement proposal for Nature Conservation Act). Finnish Government.

- Finnish National Board of Education (FNBE). (1985). National core curriculum for comprehensive school.

- Finnish National Board of Education (FNBE). (2014). National core curriculum for general upper secondary school.

- Finnish National Board of Education (FNBE). (2015). National core curriculum for comprehensive school.

- Fletcher, R. (2017). Connection with nature is an oxymoron: A political ecology of “nature-deficit disorder. The Journal of Environmental Education, 48(4), 226–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2016.1139534

- Fraser, J., Gupta, R., & Krasny, M. E. (2015). Practitioners’ perspectives on the purpose of environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 21(5), 777–800. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2014.933777

- Fritz-Vietta, N. V. M. (2016). What can forest values tell us about human well-being? Insights from two biosphere reserves in Madagascar. Landscape and Urban Planning, 147, 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.11.006

- Gardner, C. J., Nicoll, M. E., Birkinshaw, C., Harris, A., Lewis, R. E., Rakotomalala, D., & Ratsifandrihamanana, A. N. (2018). The rapid expansion of Madagascar’s protected area system. Biological Conservation, 220, 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.02.011

- Heriniaina, R. R. (2013). Perception, connaissance et attitude des eleves vis-à-vis des animaux endemiques malgaches: Cas des lemuriens [Diplome d’Etudes Approfondies, Université d’Antananarivo]. http://biblio.univ-antananarivo.mg/pdfs/heriniainaRioR_AGRO_M2_13.pdf

- Hollweg, K. S., Taylor, J. R., Bybee, R. W., Marcinkowski, T. J., McBeth, W. C., & Zoido, P. (2011). Developing a framework for assessing environmental literacy. North American Association for Environmental Education. https://cdn.naaee.org/sites/default/files/devframewkassessenvlitonlineed.pdf

- Huckle, J. (1988). What we consume: The teachers’ handbook. World Wide Fun for Nature. Richmond Publishing Company.

- Jenson, K. (2021). First-time participant experiences of socioecological learning opportunities in an environmental education program for adults. [Walden University]. Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies, 11085 https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/11085/

- Jones, J. P. G., Ratsimbazafy, J., Ratsifandrihamanana, A. N., Watson, J. E. M., Andrianandrasana, H. T., Cabeza, M., Cinner, J. E., Goodman, S. M., Hawkins, F., Mittermeier, R. A., Rabearisoa, A. L., Rakotonarivo, O. S., Razafimanahaka, J. H., Razafimpahanana, A. R., Wilmé, L., & Wright, P. C. (2019). Last chance for Madagascar’s biodiversity. Nature Sustainability, 2, Article 5 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0288-0

- Kansakoulun opetussuunnitelmakomitea. (1925). Maalaiskansakoulun opetussuunnitelma – komiteamietintö. Valtioneuvosto.

- Krasny, M. E. (2020). Advancing environmental education practice. Cornell University Press.

- LaMere, K., Mäntyniemi, S., Vanhatalo, J., & Haapasaari, P. (2020). Making the most of mental models: Advancing the methodology for mental model elicitation and documentation with expert stakeholders. Environmental Modelling & Software, 124, 104589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2019.104589

- Larsen, P. B., & Brockington, D. (Eds.). (2018). The anthropology of conservation NGOs: Rethinking the boundaries. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60579-1

- Leinonen, M. (1975). Ympäristökasvatuksen kehittäminen peruskoulussa. Finnish Ministry of Education.

- McLean, S. (2013). The whiteness of green: Racialization and environmental education. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien, 57(3), 354–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12025

- Mickelsson, M. (2020). ‘I think it works better if we have an example to help us’: Experiences in collaboratively conceptualizing the scaling of education for sustainable development practices in South Africa. Environmental Education Research, 26(3), 341–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1724889

- Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale (MEN). (2017). Plan Sectoriel de l’Education (2018-2022) (PSE). https://www.education.gov.mg/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/PSE-narratif.pdf

- Ministère de l’Environnement et des Forêts (MEF). (2013). Décret N° 2013-880 fixant la Politique Nationale de l’Éducation relative à l’Environnement pour le Développement Durable (PErEDD). http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/mad146112.pdf

- Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement durable (2020). Education environnementale: Une des priorités de la nouvelle Ministre de l’Environnement. http://mg.chm-cbd.net/news/education-environnementale-une-des-priorites-de-la-nouvelle-ministre-de-l

- Ministère de l’Environnement & Ministère de l’enseignement secondaire et de l’éducation de base. (2002). Décret n°2002-751 fixant la Politique d’éducation relative à l’environnement (PERE). http://mg.chm-cbd.net/implementation/programmes-thematiques/education-et-sensibilisation/po_nat_ere.pdf

- Monroe, M. C., & Krasny, M. E. (2016). Across the spectrum: Resources for environmental educators (3rd ed.). North American Association for Environmental Education. https://naaee.org/eepro/resources/across-spectrum-resources-environmental-educators

- Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., da Fonseca, G. A. B., & Kent, J. (2000). Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature, 403, Article 6772. https://doi.org/10.1038/35002501

- Niens, J., Richter-Beuschel, L., Stubbe, T. C., & Bögeholz, S. (2021). Procedural knowledge of primary school teachers in Madagascar for teaching and learning towards land-use- and health-related sustainable development goals. Sustainability, 13(16), 9036. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169036

- Padua, S. M. (2010). Primate conservation: Integrating communities through environmental education programs. American Journal of Primatology, 72(5), 450–453. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20766

- Parviainen, J. (2015). Cultural heritage and biodiversity in the present forest management of the boreal zone in Scandinavia. Journal of Forest Research, 20(5), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10310-015-0499-9

- Pascual, U., Balvanera, P., Díaz, S., Pataki, G., Roth, E., Stenseke, M., Watson, R. T., Başak Dessane, E., Islar, M., Kelemen, E., Maris, V., Quaas, M., Subramanian, S. M., Wittmer, H., Adlan, A., Ahn, S., Al-Hafedh, Y. S., Amankwah, E., Asah, S. T., … Yagi, N. (2017). Valuing nature’s contributions to people: The IPBES approach. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 26–27, 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2016.12.006

- Paulhus, D. (1991). Measurement and control of response bias. In P. R. Shaver, L. S. Wrightsman, & J. P. Robinson (Eds.), Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes (pp. 17–59). Academic Press.

- Pohnan, E., Ompusunggu, H., & Webb, C. (2015). Does tree planting change minds? Assessing the use of community participation in reforestation to address illegal logging in West Kalimantan. Tropical Conservation Science, 8(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/194008291500800107

- Price, E. A., Vining, J., & Saunders, C. D. (2009). Intrinsic and extrinsic rewards in a nonformal environmental education program. Zoo Biology, 28(5), 361–376. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.20183

- Ralimanana, H., Perrigo, A. L., Smith, R. J., Borrell, J. S., Faurby, S., Rajaonah, M. T., Randriamboavonjy, T., Vorontsova, M. S., Cooke, R. S. C., Phelps, L. N., Sayol, F., Andela, N., Andermann, T., Andriamanohera, A. M., Andriambololonera, S., Bachman, S. P., Bacon, C. D., Baker, W. J., Belluardo, F., … Antonelli, A. (2022). Madagascar’s extraordinary biodiversity: Threats and opportunities. Science (New York, N.Y.), 378(6623), eadf1466. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adf1466

- Randriamiharisoa, M. N., Kuhlman, A. R., Jeannoda, V., Rabarison, H., Rakotoarivelo, N., Randrianarivony, T., Raktoarivony, F., Randrianasolo, A., & Bussmann, R. W. (2015). Medicinal plants sold in the markets of Antananarivo. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 11(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-015-0046-y

- Randrianarivony, T. N., Andriamihajarivo, T. H., Ramarosandratana, A. V., Rakotoarivony, F., Jeannoda, V. H., Kuhlman, A., Randrianasolo, A., & Bussmann, R. (2016). Value of useful goods and ecosystem services from Agnalavelo sacred forest and their relationships with forest conservation. Madagascar Conservation & Development, 11(2), 44–51.

- Rantala, O., & Puhakka, R. (2020). Engaging with nature: Nature affords well-being for families and young people in Finland. Children’s Geographies, 18(4), 490–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2019.1685076

- Razafindraibe, M., Kuhlman, A. R., Rabarison, H., Rakotoarimanana, V., Rajeriarison, C., Rakotoarivelo, N., Randrianarivony, T., Rakotoarivony, F., Ludovic, R., Randrianasolo, A., & Bussmann, R. W. (2013). Medicinal plants used by women from Agnalazaha littoral forest (Southeastern Madagascar). Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 9, 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-9-73

- Reibelt, L. M., Richter, T., Rendigs, A., & Mantilla-Contreras, J. (2017). Malagasy conservationists and environmental educators: Life paths into conservation. Sustainability, 9(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9020227

- Reid, A., Dillon, J., Ardoin, N., & Ferreira, J.-A. (2021). Scientists’ warnings and the need to reimagine, recreate, and restore environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 27(6), 783–795. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2021.1937577

- Rickinson, M., & McKenzie, M. (2020). Understanding the research-policy relationship in ESE: Insights from the critical policy and evidence use literatures. Environmental Education Research, 27(4), 480–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1804531

- Rodrigues, C., & Lowan-Trudeau, G. (2021). Global politics of the COVID-19 pandemic, and other current issues of environmental justice. The Journal of Environmental Education, 52(5), 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2021.1983504

- Root, E. (2010). This land is our land? This land is your land: The decolonizing journeys of white outdoor environmental educators. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 15, 103–119.

- Salazar, G., Rainer, K. C., Watkins, L. A., Monroe, M. C., & Hundemer, S. (2021). 2020 to 2040: Visions for the future of environmental education. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 0(0), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533015X.2021.2015484

- Sauve, L. (2005). Currents in environmental education: Mapping a complex and evolving pedagogical field. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 10(1), 11–37.

- Scales, I. R. (2012). Lost in translation: Conflicting views of deforestation, land use and identity in western Madagascar. The Geographical Journal, 178(1), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4959.2011.00432.x

- Schultz, P. W. (2002). Knowledge, information, and household recycling: Examining the knowledge-deficit model of behavior change. In T. Dietz & P. C. Stern (Eds.), New tools for environmental protection: Education, information, and voluntary measures (pp. 67–82). National Academy Press.

- Schwitzer, C., Mittermeier, R. A., Johnson, S. E., Donati, G., Irwin, M., Peacock, H., Ratsimbazafy, J., Razafindramanana, J., Louis, E. E., Jr., Chikhi, L., Colquhoun, I. C., Tinsman, J., Dolch, R., LaFleur, M., Nash, S., Patel, E., Randrianambinina, B., Rasolofoharivelo, T., & Wright, P. C. (2014). Averting Lemur extinctions amid Madagascar’s political crisis. Science (New York, N.Y.), 343(6173), 842–843. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1245783

- Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-2004-22201

- Sherrow, H. M. (2010). Conservation education and primates: Twenty-first century challenges and opportunities. American Journal of Primatology, 72(5), 420–424. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20788

- Strathern, M. (1980). No nature, no culture: The Hagen case. In C. MacCormack & M. Strathern (Eds.), Nature, culture and gender (pp. 174–222). Cambridge Univ. Press. https://schwarzemilch.files.wordpress.com/2009/02/015_strathern-1998nnaturenculture_1.pdf

- Thomas, R. E. W., Teel, T., Bruyere, B., & Laurence, S. (2019). Metrics and outcomes of conservation education: A quarter century of lessons learned. Environmental Education Research, 25(2), 172–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2018.1450849

- Tolppanen, S., Kang, J., & Riuttanen, L. (2022). Changes in students’ knowledge, values, worldview, and willingness to take mitigative climate action after attending a course on holistic climate change education. Journal of Cleaner Production, 373, 133865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133865

- UNEP. (2005). UNEP strategy for environmental education and training: A strategy and action planning for the decade 2005–2014. United Nations Environment Programme. https://wedocs.unep.org/xmlui/handle/20.500.11822/11278

- UNESCO. (1977). The Tbilisi Declaration. In Intergovernmental conference on environmental education (pp. 14–16). UNESCO, UNEP. https://www.gdrc.org/uem/ee/EE-Tbilisi_1977.pdf

- UNESCO. (2020). Education for sustainable development: A roadmap. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802

- Velempini, K., Martin, B., Smucker, T., Randolph, A. W., & Henning, J. E. (2018). Environmental education in southern Africa: A case study of a secondary school in the Okavango Delta of Botswana. Environmental Education Research, 24(7), 1000–1016. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2017.1377158

- Vieilledent, G., Grinand, C., Rakotomalala, F. A., Ranaivosoa, R., Rakotoarijaona, J.-R., Allnutt, T. F., & Achard, F. (2018). Combining global tree cover loss data with historical national forest cover maps to look at six decades of deforestation and forest fragmentation in Madagascar. Biological Conservation, 222, 189–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.04.008

- Vogel, I. (2012). Review of the use of “Theory of Change” in international development. UK Department for International Development. https://www.theoryofchange.org/pdf/DFID_ToC_Review_VogelV7.pdf

- Vuola, M., & Pyhälä, A. (2016). Local community perceptions of conservation policy: Rights, recognition and reactions. Madagascar Conservation & Development, 11(2), Article 2.

- Waeber, P. O., Rafanoharana, S., Rasamuel, H. A., & Wilmé, L. (2019). Parks and reserves in Madagascar: Managing biodiversity for a sustainable future. In Protected areas, national parks and sustainable future. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.85348

- Waeber, P. O., Wilmé, L., Mercier, J.-R., Camara, C., & Lowry, P. P. II, (2016). How effective have thirty years of internationally driven conservation and development efforts been in Madagascar? PloS One, 11(8), e0161115. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161115

- Wals, A., Geerling-Eijff, E. J., Hubeek, F., Kroon, F., van der, S., & Vader, J. (2008). All mixed up? Instrumental and emancipatory learning toward a more sustainable world: Considerations for EE policymakers. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 7(3), 55–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15330150802473027

- Ward, C., Stringer, L., & Holmes, G. (2018). Changing governance, changing inequalities: Protected area co-management and access to forest ecosystem services: A Madagascar case study. Ecosystem Services, 30, 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.01.014

- Whitburn, J., Linklater, W., & Abrahamse, W. (2020). Meta-analysis of human connection to nature and proenvironmental behavior. Conservation Biology: The Journal of the Society for Conservation Biology, 34(1), 180–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13381