Abstract

This article engages with discard studies scholarship to interrogate findings from a study that set out to deliberately follow wastepaper in an early childhood setting. The study, which used participatory methods positioning teachers and children as research partners, began with purposeful noticing and attunement to paper’s movements and materiality. This attentiveness defamiliarized paper and the ways in which it is known and experienced. It led to questions about the wider systems in which paper is entangled. In this article, thinking with discard studies provokes us to consider the relational systems that involve paper in early learning settings and leads us to question the reduce-reuse-recycle maxim which allows some systems to flourish by diverting attention away from them. The article concludes by suggesting that if we are to discard well, we must become aware of systems that are maintained by taken-for-granted waste practices such as reducing, reusing, and recycling.

Introduction

Paper is a ubiquitous material in Euro-Western early education. It is seen as essential for many learning experiences and practices, but it is also used extensively for communicating, record-keeping, reporting, packaging, cleaning, and sanitation. Early education institutions are called to reduce, reuse, and recycle paper as a move toward minimizing landfill and the environmental impacts of paper-making processes. Children are frequently involved in these actions as part of environmental education programs. These are worthy aims, particularly as paper makes up a significant proportion of landfill—up to 26 percent in the United States (Department of Environment, Citation2014; MacBride, Citation2012; United States Environmental Protection Agency, Citation2016b). Our experience suggests, however, that despite good intentions, reducing, reusing, and recycling paper is far from straightforward for an individual teacher or early education setting. Furthermore, efforts to reduce, reuse, and recycle may even contribute to the paper waste problem by diverting attention away from the processes and regimes that support and encourage paper production and consumption (MacBride, Citation2012).

This article is informed by our research that deliberately sought to pay close attention to paper at an early learning setting by following its forces, fluxes, rhythms and flows (Pacini-Ketchabaw et al., Citation2017). This attentiveness brought children, educators, and researchers into a relationship with paper, which in turn exposed the way in which paper production and consumption are inextricably entangled within much wider systems. Here, we engage with the theoretical perspectives emerging from the interdisciplinary field of discard studies, which seeks to “trouble the assumptions, premises and popular mythologies of waste” (Liboiron, Citation2014, para. 1) by bringing attention to the broader material, social and political systems that make discarding possible (Liboiron, Citation2021; Liboiron & Lepawsky, Citation2022; MacBride, Citation2012). Thinking with discard studies and paper, this article brings environmental education and discard studies into conversation by engaging with the questions: How might attentiveness to paper make the familiar strange, and what new relations might this defamiliarization activate? These questions lead us to consider how paper and other waste might be “discarded well” (Liboiron & Lepawsky, Citation2022) in early childhood and other educational settings. While this article does not aspire to provide neat answers or solutions, for environmental education these questions are important provocations, particularly as the reduce-reuse-recycle paradigm is often a mainstay of environmental education programs.

The article draws on research with an early learning center that was part of a nine-month-long participatory study involving five other early learning centers in Perth, Australia. The larger project sought to examine children’s relations with waste and was animated by the question, “What happens when waste materials are kept in sight and in mind?” Each setting in the study chose a different waste material to work with; the setting discussed in this article followed relations with used or “waste” paper after educators were prompted by a two-year-old child who refused to discard paper she had used. Motivated by discard studies scholars problematizing the well-known waste management triad, “reduce-reuse-recycle” (Geyer et al., Citation2016; Lepawsky, Citation2018; MacBride, Citation2012; Zink & Geyer, Citation2019), and Myra Hird’s contention that “waste flows and mobilizes relations” (2016, para. 4), the study set out to engage in slow and situated pedagogies that aimed to notice and critically work with a material commonly found in educational contexts. The research approach was also informed by projects with young children in Reggio Emilia, Italy (Cavallini et al., Citation2011) and Canada (Pacini-Ketchabaw et al., Citation2017), where materials are seen not as inert and passive but as active participants in shaping ideas, behaviors, places, and spaces.

We begin the article with a brief overview of discard studies and then spend a moment disturbing some commonly held assumptions about the “eco-friendliness” of paper. We also discuss the reduce-reuse-recycle triad that has long been the cornerstone of waste management and waste education approaches. We then describe some early childhood projects that have explored the materiality of paper before introducing our study’s setting and methodological approaches. Next, we narrate a series of excerpts from our research, discussing how intentional attunement to paper drew our attention to systems in which it is entangled. The article concludes by suggesting that “discarding well” (Liboiron & Lepawsky, Citation2022) in early childhood settings can begin with close attention to waste materials. Such attentiveness can defamiliarize children and teachers with everyday waste materials and undo understandings and practices such as reduce-reuse-recycle that seem normal or given.

Discard studies

The emerging interdisciplinary field of discard studies, “the social science of waste and wasting” (Liboiron, Citation2021), is particularly influential in the interrogation of our research. The term “discard studies” was first coined in 2010 by anthropologist-in-residence at New York City Department of Sanitation, Robin Nagle, who founded the Discard Studies website (see discardstudies.com) as a site for organizing the emerging field. The site was subsequently managed by Nagle’s (then) graduate student Max Liboiron, with colleagues Josh Lepawsky and Alex Zahara, who have become key contributors to the website and to theorizing the field more broadly. Other contributors include scholars from disciplines as varied as anthropology, cultural studies, environmental humanities, geography, and history, as well as artists, activists, and other community members. The website states that:

the field of discard studies is united by a critical framework that questions premises of what seems normal or given, and analyzes the wider role of society and culture, including social norms, economic systems, forms of labor, ideology, infrastructure, and power in definitions of, attitudes toward, behaviors around, and materialities of waste. (Discard Studies, n.d., para. 2)

Paper: “eco-friendly?”

The fact that paper is made from plant fiber is well known—two-to-four-year-old children in our study frequently declared paper “is made from trees.” Thus, as an organic, “biodegradable” and recyclable material made from pulped wood, wastepaper was regarded at the outset of our study by participants as benign or “eco-friendly” waste. However, paper and its production have a significant ecological impact. To begin with, tree plantations grown for paper pulp require logging of old-growth forests and destruction of habitat to create monocultures that support very few other species. Paper production also creates air and water pollution (Kumar, Citation2017; Liboiron, Citation2016). For example, in the United States, the paper industry was the second highest contributor to air pollution (United States Environmental Protection Agency, Citation2015, updated 2017), and contributed to 9% of industrial releases to water (United States Environmental Protection Agency, Citation2016a). In addition to pulped wood, paper also contains fillers, brighteners, dyes, adhesives, and many other additives (Bajpai, Citation2018a). While most of the approximately 10,000 chemicals commonly found in paper are more-or-less harmless, 157 are classed as problematic, 51 persist when paper is recycled, and 24 have potential to bioaccumulate (Pivnenko et al., Citation2015). In short, when paper is composted or recycled, toxic residues persist, and this is exacerbated when paper is repeatedly recycled.

Predictions that technology would lead to decreased paper use have not come to fruition. In fact, global paper consumption has escalated (Bajpai, Citation2018b) and despite increases in paper recycling, paper remains a significant component of landfill. As previously mentioned, in the United States, paper makes up around 26 percent of material in landfill (United States Environmental Protection Agency, Citation2016b). In Australia, where this study took place, the Federal Department of Environment estimates that around 1.5 million tonnes of paper is discarded annually, with most ending up in landfill (Department of Environment, Citation2014). However, the anaerobic conditions of landfill are not conducive to decay and studies of landfill have reported recovering paper virtually intact after decades of burial (Ximenes et al., Citation2008; Citation2015). Thus, contrary to popular belief, landfills “are not vast composters; rather they are vast mummifiers" (Rathje & Murphy, Citation2003, p. 112).

Paper, therefore, is not a benign waste material. It has a significant environmental impact, but what is important to note here is that paper is also part of systems that not only promote widespread paper use but also work to keep wastepaper out of sight and out of mind. It is these systems that came to light in our study.

Troubling the 3Rs

The “reduce-reuse-recycle” (3Rs) triad has been the basis of waste management and education approaches for many years. Reduce-reuse-recycle is a catchy slogan but it belies the complexity of issues surrounding waste and serves to “perpetuate easy narratives about blame and harm without attending to the nuances, or even facts, of the matter” (Lepawsky, Citation2019, para 1). One of these “easy narratives” is that solutions to waste issues lie within the individual, but as Lepawsky (Citation2019) argues, this absolves manufacturers of responsibility for their contribution to the waste problem and confines discussion to what becomes of waste after it already exists. Reduce-reuse-recycle educational programs are aimed squarely at consumers, not producers who ultimately have the most power to put the mantra into action. It is no coincidence, then, that manufacturers of paper and paper products are often also key players in the paper recycling industry as it is in manufacturers’ interests to promote guilt-free use of paper by ensuring wastepaper is quickly kept out of sight and out of mind. Another easy narrative is that recycling “saves trees” but as MacBride (Citation2019) explains, recycling can exacerbate resource (for example, trees) use by enabling more efficient use of resources, which then enables more extraction.

The field of education has taken up the reduce-reuse-recycle triad wholeheartedly; it is frequently the centerpiece of sustainability curriculum materials and programs. Printed and digital reduce-reuse-recycle resources for educators abound, with most suggesting, either explicitly or implicitly, the 3Rs as the solution to the world’s ever-increasing waste problem. Recycling paper is promoted as a way to reduce pressure on the resources and ecosystems on which paper production relies. As a result, “a general optimism about recycling as earth-saving has become internalized in the thought processes of children and adults genuinely concerned about preservation” (MacBride, Citation2019, para. 19).

Paper as lively matter in early childhood education

Although paper is commonplace in Euro-Western early childhood educational (ECE) settings, it is mostly used once then quickly discarded. Some paper may remain longer if it is in the form of a book or record to be retained for regulatory reasons, but in the digital age paper documents are becoming less common and most paper in ECE settings is only there for a short time. So while paper may appear to be a “solid” and seemingly inert material, it can in fact be viewed in terms of its “flow” (Gille, Citation2006; Hird, Citation2016); a lively material that is always on the move.

Even though paper is seen as indispensable for education, as a material it does not generally attract much pedagogical attention. It is the print it carries, the items it packages, and the hygiene it affords that are highly valued—the paper itself is rarely noticed. Educators from the Italian city of Reggio Emilia (see, for example, Vecchi & Giudici, Citation2004; Vecchi & Ruozzi, Citation2015), however, are among a few who have paid close attention to paper’s materiality in an educational setting. Paper was included in the system-wide, long-term, materials-focused inquiry, Dialogue with Materials (Cavallini et al., Citation2011; Ruozzi, Citation2010), which led to the creation of a permanent public exhibition or “atelier” called The Secrets of Paper Atelier (Reggio Children, Citation2022). The Secrets of Paper Atelier enables citizens of Reggio Emilia to “discover [paper’s] anatomy, its capacity for becoming plastic and malleable, for holding within itself the memories of gesture, for generating and being regenerated” (Reggio Children, Citation2022). Rather than viewing paper as static and passive matter to be contained and managed (Hird, Citation2016), The Secrets of Paper project imagined paper as being able to do things as an actant (Latour, Citation2004) that can modify and change other entities, including humans.

Inspired by the work in Reggio Emilia, a group of Canadian educators and researchers also experimented with various materials, paper among them, in a project called Encounters with Materials (Pacini-Ketchabaw et al., Citation2017). In seeking to know materials beyond their physical properties, Encounters with Materials led educators and researchers “to tell stories of how materials [including paper] are caught up in the world’s flows, rhythms, and intensities” (p. 15). Following paper brought attention to its entangled relations: “To know paper in this way is not just to describe its properties or attributes, but to learn how it moves and to describe what happens to it as it shifts, mixes, modifies, mutates” (p. 24). By choosing to see paper as lively and always in motion, both the Italian and Canadian projects invited human participants to pay attention to the inseparability of humans, paper, and the wider systems in which they exist, and how all constantly change one another.

Ways of working

It is with this background that we approached our study with a 35-place early learning center (hereafter, “the Center”) for two-to-four-year-old children in Perth, Western Australia where Katie (third author) was owner and head educator. Katie was invited to be part of this study as she and her team were interested in environmental issues, used the arts in their practice, and were familiar with “pedagogical documentation” (Dahlberg, Citation2012; Giudici et al., Citation2001) as a collaborative and emergent approach to researching with children. Developed by educators in Reggio Emilia, pedagogical documentation is enacted as part of the daily educational program. It is as much a process as a product (Dahlberg, Citation2012). In our study, pedagogical documentation included engaging children in drawing, talking, singing, making, and playing, which educators and researchers recorded through field notes, photography, and videoing. These methods were not implemented as a pre-planned regime but were deployed as the research unfolded. Katie worked daily with educators and children, while Jane (first author) partook in weekly two-hour participant-observer visits to the Center. Between visits, Jane and Katie engaged in critically collaborative dialogues via email and videoconferencing. They shared their documentation with the larger research group (other educators and the research team) via a private blog and several in-person meetings. These discussions also informed the research and pedagogy as the project proceeded.

Thinking, noticing, experimenting with paper

The excerpts from our documentation that follow are but some of many that could have been shared. In sharing these seemingly unremarkable excerpts “[w]e are interested in telling stories that draw others, including ourselves, into new forms of curiosity and understanding, new relationships and so new accountabilities” (van Dooren, Citation2018, p. 443). They tell a story of how thinking, noticing, and experimenting with paper led to questioning of reduce-reuse-recycle assumptions. We begin with an excerpt narrated by Katie who had noticed two-year-old Franny’s (pseudonym) intense interest in paper. Each day Franny scrunched, glued, marked, and carried various pieces of paper. She refused invitations to discard these papers and insisted on taking them home as “gifts” for her mother, although we learned from Franny’s mother that she had not received any gifts; rather, Franny kept them in her bedroom and fiercely objected to them being thrown out. It was Franny’s passion for paper that led to it being chosen as the waste material to be followed at the Center.

Excerpt 1: Noticing paper’s possibilities

Katie:

Franny has a piece of red A4 paper in her hands. She begins rolling it, just a little, then when its long edge overlaps, she scrunches it lengthways until it fits in the palm of one hand. She looks at its shape for a moment. Franny sits on the carpet with her paper and as we talk, she moves her paper back and forth though the air. She waves her arms around; perhaps the paper is dancing. She lies the paper down horizontally and notices something—the place where her hand has been has made a slight bend in the paper. Noticing this, Franny folds the paper with ends together and it springs back slightly. She places paper down onto the carpet to make a “rainbow.” The paper falls over and Franny tries again to make the paper rainbow stand. It falls over a third time, so she holds it in place and stares at it for a few seconds.

Franny then draws lines in the crevices of paper, while singing, “Rainbow, rainbow” (). She shakes it and listens. “It’s a shaker,” she says. She finds small pieces of rubber band and places them inside the shaker. Franny unfurls the paper again which reveals dots, circles, and markings she has made throughout the morning. She sniffs the paper and says, “Look inside…a flower.” Franny plays around with her flower, exploring how to balance it upright using one hand, then holds it between her knees and finally her thighs then laughs as she pulls it towards her stomach.

For Franny, paper is “vibrant matter” (Bennett, Citation2010), a lively, interesting, responsive and interactive partner that seems to call her to “look here!” (Bennett, Citation2022). It enchants her. As educators and researchers, we wonder if, like other educators and researchers interested in the liveliness of paper (Cavallini et al., Citation2011; Pacini-Ketchabaw et al., Citation2017; Ruozzi, Citation2010), we too can be enchanted by paper, or at least learn to see it as lively rather than as an inert resource to be used then discarded? And we wonder if learning to see paper differently might help us to “devise new procedures, technologies, and regimes of perception that enable us to … listen and respond more carefully” (Bennett, Citation2010, p. 108)? In response, Katie devises some experimentations of her own, as the next excerpt describes.

Excerpt 2: Experimenting with paper

Katie:

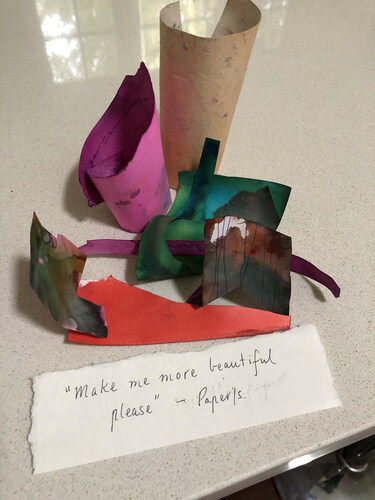

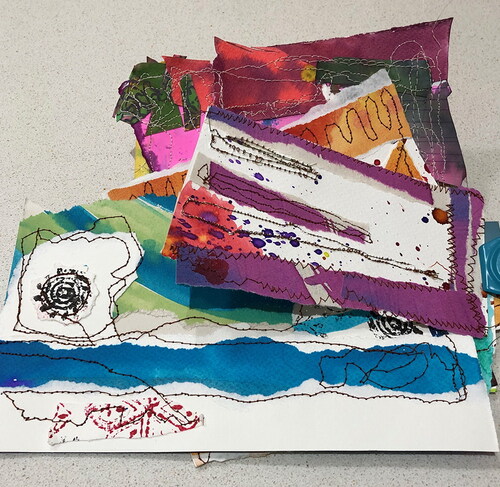

How can I learn to see paper like Franny? Over several weeks I work with a selection of used paper and think of Franny as I examine each piece – I play with it, tear it, fold it, scrunch it, soak it, shine lights onto and through it, print and paint over it again and again ( and ). I listen to the sounds it makes when I tear curly strips. I arrange pieces into little papery compositions in glass vases and jars. I explore layering and sewing paper pieces together and realise how strong paper and thread become. I am playing in the way I see Franny “play.” She returns to a piece over and over, adding more and more. These experimentations take time, but they lead me to see paper in more detail – like the way paper records the patterns and creases when a scrunched-up ball of wastepaper is painted and left to dry in the sun. I look forward to unfolding these delicate crispy paper – they look like clouds at sunset. These experimentations change my relationship with paper. Instead of merely recycling or reusing wastepaper, I now enjoy being creatively entangled with it, see its potentiality, and even feel myself becoming fond of it.

Katie’s experimentations are made possible by being deliberately attentive to paper. Touching, tearing, curling, soaking, scrunching, and layering paper defamiliarizes a material she had previously regarded simply as a lifeless pedagogical resource. Katie’s playful “enchanted animism” (Merewether, Citation2020) of paper brings it to life, stirring her “ecological imagination” (Taylor, Citation2020), which allows her “to go visiting, to venture off the beaten path to meet unexpected, non-natal kin, and to strike up conversations, to pose and respond to interesting questions” (Haraway, Citation2015, p. 8). This defamiliarization leads Katie not only to insights about how Franny might see paper, but importantly it also allows Katie to imagine paper’s movements within and beyond the Center. Now that Katie’s attentiveness to paper is piqued, she notices it is “hiding” at the Center, as the following excerpt illustrates.

Excerpt 3: Keeping waste in sight

Katie:

I realise used paper is being hidden in the multiple “recycling boxes” peppered throughout the Center, which we regularly empty into three large curbside recycling bins provided by the council.

So, as a strategy for keeping wastepaper in sight and in mind, I have replaced these boxes with several large open-weave wastepaper baskets, and I have asked educators to place all used paper neatly in the baskets and try to re-use it with the children ().

I imagined only a slight shift in practice was needed, but after only a week the baskets are overflowing, and I have begun to feel despair! We are at a loss to know what to do with ALL THIS PAPER! Paper is now very visible and the sheer volume of it is overwhelming! Newspaper, brown paper, shredded paper, and cardboard arrives uninvited – packed around supplies such as paint, glue, and markers – most of these would not break if packed in one box together, but instead they are sent to us in several boxes with loads of paper packaging. Catalogues, magazines and flyers, posters and information sheets arrive continuously. Furthermore, now that families know we are using wastepaper, they are bringing in more in the hope we can get rid of it for them. We have had to refuse all paper donations because we just can’t cope with the paper generated on site.

The intentional choice to keep paper in sight and mind, rather than divert it to recycling bins, reveals the huge volume of paper that enters the Center. A significant proportion of this paper arrives, as Katie puts it, “uninvited” in the form of packaging, advertising, and unsolicited mail. Prior to the study, Katie and her team had diligently ensured this paper was quickly hidden in strategically placed recycling bins throughout the Center, but when they remove these bins as an option, the extent of paper’s presence is exposed. Hird (Citation2013) argues that Western landfills are “sites of forgetting” (p. 105), but educators at the Center discover that the process of forgetting begins with recycling bins. Catlin and Wang (Citation2013, p. 126) assert that “the availability of a recycling option can actually increase resource usage”—the Center’s experience confirms this, and Katie and her team come to the uncomfortable realization that their well-intentioned recycling is enabling paper waste and wasting not reducing it.

In response to this realization, educators decide to try to reduce paper consumption at the Center by offering children various opportunities to reuse it, but unlike Franny, most children dismiss it as an option and either insist on using “new” paper or simply choose other activities. Some even explicitly reject used paper as “rubbish,”Footnote1 as Katie’s next excerpt illustrates:

Excerpt 4: Used paper is rubbish

Katie:

I set out neatly rolled-up pieces of used paper for children to reuse. Alongside is an array of pencils, glue sticks, scissors, stamps, inks, and markers. Two-year-old Lachlan arrives and picks up one of the carefully rolled up papers and puts it the bin. He repeats this process. I ask what he is doing. “Put[ting] rubbish in the bin,” he replies.

Then, he picks up one of Franny’s paper “gifts” that she has left unattended for a moment and is on his way to the bin when Franny returns just in time to save it.

Katie and her team’s attempts to reduce the amount of paper going into recycling bins by keeping it in view and reusing it meets strong resistance from the children—our study reveals that children as young as two and three years old are already well attuned to the logics of paper’s disposability. As discard studies scholar Gay Hawkins (Citation2019, para. 1) points out, “[w]hen we describe something as ‘disposable’ we are really describing it as rubbish, we are pointing to the fact that it was made to be wasted—not reused.” Although paper at the Center is clearly visible and burgeoning each day, the children ignore it, apart from remarking on several occasions that it is “rubbish.” The logic of paper as a single-use material dominates, so educators decide that if children are to see used paper differently, interventions that call attention to used paper’s properties, movements, and potentialities are needed. The next excerpt from Jane’s documentation narrates one of these interventions.

Excerpt 5: Curling and Sounding with Paper

Jane:

Katie shows children how she has noticed that when paper is torn in a particular way it forms curls, seemingly of its own accord. She invites children to try it too. They drop the curls into a large glass vase, creating an intriguing everchanging curlicue within. ()

“Listen to the sound paper makes as it tears,” Katie suggests.

“It sounds like fire!”

“It sounds like water.”

“It sounds like rain!” the children exclaim.

These purposeful encounters with paper hone children’s and educators’ “arts of noticing” (Tsing, Citation2015), opens them to experimentation and speculation, and sensitizes them to paper’s materiality, vitality, and relations. Paper becomes a lively material with histories and agency. Educators then extend children’s (aural) listening to paper to “listening” to the trees and land that provide paper - what might the trees and land be saying? How might they feel? Children also try to make their own paper from wastepaper and from fallen leaves at the Center, but the results are not useable, let alone reusable. Nonetheless, it gives them insight into the resources and labor needed to turn trees into paper. A truck driver tells an educator he takes “recycling” directly to landfill, not to a recycling depot, so Katie tries to inquire what happens to paper once it leaves the Center. She encounters guarded and vague responses. Local councils direct her to companies they contract for recycling, but Katie learns the specifics are proprietary knowledge. Meanwhile, the Center significantly reduces the paper it buys, but paper continues to arrive in copious amounts, particularly as packaging. This leads to the following two excepts from Jane’s documentation, which narrate children’s attempts to dispose the paper on site, and their discovery that paper is not as disposable as they had thought.

Excerpt 6: Disappearing Paper?

Jane:

Katie asks the children, “Could you make paper disappear without putting it in a bin?

They speculate:

Bury it. ()

Bury it, but with water too.

Add water to the paper and leave it in the sun.

Put it in soil from the worm farm.

Burn it!

If you put it in the ground, it turns back into a tree again.

The children investigate some of these ideas. After a few weeks, they revisit paper buried in sand, in soil from the worm farm, in water, etc. In all instances, much to children’s surprise, the paper was still as new–it did not disappear at all.

Excerpt 7: Noticing Paper’s Properties

Jane:

It is raining. Katie takes a (waste)paper basket outside and suggests to three children they take paper into the rain and puddles. A small piece of paper that is painted on one side attracts a child’s attention. He places it paint-side down in a puddle. “Water makes it soggy.”

He scoops the soggy paper up and inspects it carefully.

He puts the paper back into the water, stamps on it, then takes it to a small patch of dry sand. He rubs it carefully with his hand then folds it into a small square. He unfolds it and repeatedly jumps on it. He folds it again and immerses it again in small puddles (). The paper loses its colour but remains intact at the end of these experimentations.

Nearby, another child is doing something similar with another piece of paper. But this paper behaves differently and quickly falls apart. The child gathers blobs together and moulds them into a “sausage” then a “pancake.” *

A third child puts another piece of paper through a similar process of wetting, burying, stamping, folding. At the end of it all, he exclaims, “This paper is strong! It won’t break!”

*A week later, I find this pancake in the sandpit, now dried out but still recognizable.

Children’s and educators’ “passionate immersion” (Tsing, Citation2011, p. 19) in the life of paper, exposes its endurance, the myth of its “disposability, and how it never really goes away. Katie and her team now question the ethics of disposing of paper via curbside recycling, which they previously assumed was the “right” thing to do. They realize their recycling efforts are part of the “tactics of avoidance” (Liboiron & Lepawsky, Citation2022, p. 90) that contribute to wider systemic mechanisms that help maintain paper production by keeping paper waste hidden from public view (Liboiron & Lepawsky, Citation2022; MacBride, Citation2019). Educators are no longer confident that paper they put into recycling bins is actually recycled, or if recycling paper is feasible at a scalable level. As MacBride (Citation2019) points out, it is unlikely that profit-driven resource extraction companies will scale back extraction due to the input from recycling. Indeed, increased recycling exists alongside increased resource extraction (MacBride, Citation2019). Passionate immersion in paper also reveals the vast quantities of largely unsolicited paper that come to the Center, and how little power educators have to control it, at least at a level that is scalable. The “scalar mismatch” (Liboiron & Lepawsky, Citation2022, pp. 35–59) of educators’ and children’s efforts compared to the systemic machinations involved in paper production and consumption becomes plainly obvious to educators.

Concluding discussion

This article does not present grand conclusions for environmental education, only troublings of common knowledges and practices surrounding waste and wasting narratives that came to light during our situated inquiry in an early childhood center. In our study, deliberately calling attention to paper served as a technique of defamiliarization (Liboiron & Lepawsky, Citation2022) that foregrounded how little we (educators, researchers and children) knew about the ubiquitous material that is paper. Following paper made the familiar strange and threw into question taken-for-granted notions surrounding paper production, consumption, and waste. It led educators and children to see paper as more than a classroom resource. Paper became an active protagonist in the Center and in systems beyond. It prompted questions such as: What else is in paper other than trees? How is paper made? Whose traditional lands were annihilated so we could have paper? What does paper do? Is paper an eco-friendly material? What happens to paper we put into recycling bins? Is the paper recycling process eco-friendly? Each question kindled more questions, and assumptions about the reduce-reuse-recycle model that had underpinned educators’ approaches to waste management and education began to unravel. This was deeply disappointing for our educators as it forced them to let go of dearly held practices that they formerly believed “good.”

At the time of writing, educators in our study are still grappling with the question of what it means to “discard well” (Liboiron & Lepawsky, Citation2022). Hird explains how “[t]he indeterminacy of waste draws our attention to the imprescriptibility of ethical responsibility to future generations and environmental sustainability” (Hird, Citation2016, para 19) so we will not offer any prescriptions here. Rather, we hope that the narration of our experience opens a space for others concerned with environmental education for (re)examining presumptions and practices, and to respond in ways that are specific to each context. For the educators we worked with, attentiveness to waste, rather than avoiding it was key. As Hawkins (Citation2006, p. 133) notes, “[t]he very act of attention, of noticing what we so often don’t see, captures us in different relations with objects that can become new networks of obligation.” Following paper drew attention to its materiality and presence, making visible the prevailing “ethos of distance, denial, and disposability” (Hawkins, Citation2006, p. 22) that surrounds paper. Importantly, it drew attention to systems that permit and perpetuate waste and wasting and showed the insignificance of their efforts to reduce, reuse, and recycle paper, relative to the scale of paper production at a global level. These were deeply bewildering things to learn as there are no certain actions to deploy instead of the 3Rs. Nonetheless, for those in our project, keeping waste in sight and in mind was a starting point for discarding well. It helped “cultivate the mindset to consider the deeper systemic factors underlying waste and consumption patterns” (Goldman et al., Citation2021, p. 399). A disposition to question has been sparked. For now, we take heed of MacBride’s (Citation2019, p. 6) suggestions to:

“[A]sk corporate spokespeople how the tonnage they take credit for recycling fed back into their operations last year, in a specific country, and how it in turn measurably reduced virgin extraction. Be specific. Ask them where and when it led to a reduced material throughput in their company or industry. Query them on the documented, not speculative, environmental protection afforded by, say, making cheap picture frames made out of spent polystyrene packaging. (p. 6)

This, of course, is not something that young children can do without significant assistance from their teachers. However, even very young children are concerned about environmental issues and teachers can pose these questions on children’s behalf or help children to pose them themselves. Admittedly, this may seem an inadequate response given the extent of the waste issues the world faces, but as discard studies scholars are showing, it is not tenable to continue promulgating reduce-reuse-recycle logics as if they are beyond critique. We therefore advocate a “joining-in” approach in which specific experiences contribute to ongoing conversations that open paths for thinking about and with waste. We hope that sharing situated accounts of attempts to notice, follow, and experiment with waste in educational settings, as we have done here, may help provoke reconsideration of, or at least render less appealing, simplistic assumptions that pervade approaches to waste in early childhood education and beyond.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all our research colleagues and participants for their generous and enthusiastic sharing of time, experience, and insights. We are also grateful to our anonymous reviewers whose thoughtful suggestions made this a better paper.

Notes

1 In Australia “rubbish” is a common term used for trash or garbage.

References

- Bajpai, P. (2018a). Biermann’s handbook of pulp and paper (3rd ed., Vol. 1 & 2). Elsevier.

- Bajpai, P. (2018b). Introduction and the literature. In P. Bajpai (Ed.), Biermann’s handbook of pulp and paper (3rd ed., pp. 1–18). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-814240-0.00001-X

- Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Duke University Press.

- Bennett, J. (2022). Afterword: Look here. Environmental Humanities, 14(2), 494–498. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-9712533

- Catlin, J. R., & Wang, Y. (2013). Recycling gone bad: When the option to recycle increases resource consumption. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 23(1), 122–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2012.04.001

- Cavallini, I., Filippini, T., Vecchi, V., & Trancossi, L. (Eds.). (2011). The wonder of learning: The hundred languages of children (J. McCall, Trans.). Reggio Children.

- Dahlberg, G. (2012). Pedagogical documentation: A practice for negotiation and democracy. In C. Edwards, L. Gandini, & G. Forman (Eds.), The hundred languages of children: The Reggio Emilia experience in transformation (3rd ed., pp. 225–231). Praeger.

- Department of Environment. (2014). National Inventory Report 2012 Volume 3, Commonwealth of Australia 2014. http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/6b894230-f15f-4a69-a50c-5577fecc8bc2/files/nationalinventory-report-2012-vol3.pdf.

- Discard Studies. (n.d). What is discard studies? https://discardstudies.com/what-is-discard-studies/

- Geyer, R., Kuczenski, B., Zink, T., & Henderson, A. (2016). Common misconceptions about recycling. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 20(5), 1010–1017. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12355

- Gille, Z. (2006). Detached flows or grounded place-making projects? In A. Mol & G. Spaargaren (Eds.), Governing cnvironmental flows: Global challenges to social theory (pp. 137–156). MIT Press.

- Giudici, C., Rinaldi, C., & Krechevsky, M. (Eds.). (2001). Making learning visible: Children as individual and group learners. Reggio Children.

- Goldman, D., Alkaher, I., & Aram, I. (2021). “Looking garbage in the eyes”: From recycling to reducing consumerism- transformative environmental education at a waste treatment facility. The Journal of Environmental Education, 52(6), 398–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2021.1952397

- Haraway, D. (2015). A curious practice. Angelaki, 20(2), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969725X.2015.1039817

- Hawkins, G. (2006). The ethics of waste. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Hawkins, G. (2019). Disposability. Discard Studies. https://discardstudies.com/2019/05/21/disposability/

- Hird, M. J. (2013). Waste, landfills, and an environmental ethic of vulnerability. Ethics & the Environment, 18(1), 105–124. https://doi.org/10.2979/ethicsenviro.18.1.105

- Hird, M. J. (2016). The phenomenon of waste-world-making. Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, 30, 183–191. https://doi.org/10.20415/rhiz/030.e15

- Kumar, V. (2017). Recycling of waste and used papers: A useful contribution in conservation of environment: A case study. Asian Journal of Water, Environment and Pollution, 14, 31–36. https://doi.org/10.3233/AJW-170034

- Latour, B. (2004). Politics of nature: How to bring the sciences into democracy (C. Porter, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

- Lepawsky, J. (2018). Reassembling rubbish: Worlding electronic waste. The MIT Press.

- Lepawsky, J. (2019). PSA: Beware of easy narratives. https://discardstudies.com/2019/08/12/psa-beware-of-easy-narratives/

- Liboiron, M. (2021). Pollution is colonialism. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1jhvnk1

- Liboiron, M., & Lepawsky, J. (2022). Discard studies: Wasting, systems, and power. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/12442.001.0001

- Liboiron, M. (2014). Why discard studies? Discard Studies. https://discardstudies.com/2014/05/07/why-discard-studies/

- Liboiron, M. (2016). The politics of recycling vs. reusing. Discard Studies. https://discardstudies.com/2016/03/09/the-politics-of-recycling-vs-reusing/

- Liboiron, M. (2018). The what and the why of discard studies. Discard Studies. https://discardstudies.com/2018/09/01/the-what-and-the-why-of-discard-studies/

- MacBride, S. (2012). Recycling reconsidered: The present failure and future promise of environmental action in the United States. MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/8829.001.0001

- MacBride, S. (2019). Does recycling actually conserve or preserve things? Discard Studies. https://discardstudies.com/2019/02/11/12755/

- Merewether, J. (2020). Enchanted animism: A matter of care. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949120971380

- Pacini-Ketchabaw, V., Kind, S., & Kocher, L. (2017). Encounters with materials in early childhood education. Routledge.

- Pivnenko, K., Eriksson, E., & Astrup, T. F. (2015). Waste paper for recycling: Overview and identification of potentially critical substances. Waste Management (New York, N.Y.), 45, 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2015.02.028

- Rathje, W., & Murphy, C. (2003). Rubbish! The archaeology of garbage. University of Arizona Press.

- Reggio Children. (2022). The secrets of paper. https://www.reggiochildren.it/en/ateliers/i-segreti-della-carta-en/

- Reno, J. O. (2015a). Waste and waste management. Annual Review of Anthropology, 44(1), 557–572. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102214-014146

- Reno, J. O. (2015b). Waste away: Working and living with a North American landfill. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520963771

- Reno, J. O. (2017). Wastes and values. In D. Sosna & L. Brunclíková (Eds.), Archaeologies of waste: Encounters with the unwanted (pp. 17–22). Oxbow Books.

- Ruozzi, M. (2010). Dialogue with materials: Research projects in the infant-toddler centers and preschools of Reggio Emilia. Innovations in Early Education: The International Reggio Emilia Exchange, 17(2), 1–12.

- Taylor, A. (2020). Downstream river dialogues: An educational journey toward a planetary-scaled ecological imagination. ECNU Review of Education, 3(1), 107–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/2096531120905194

- Thompson, M. (2017). Rubbish theory: The creation and destruction of value (2nd ed.). Pluto Press.

- Tsing, A. (2011). Arts of inclusion, or, how to love a mushroom. Australian Humanities Review, 50(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.22459/AHR.50.2011.01

- Tsing, A. (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in the capitalist ruins. Princeton University Press.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2015). Updated 2017). TRI National Analysis 2015. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2017-01/documents/tri_na_2015_complete_english.pdf

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2016a). 2015 annual effluent guidelines review report. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-06/documents/2015-annual-eg-review-report_june-2016.pdf

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2016b). Advancing sustainable materials management: 2014 fact sheet. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-11/documents/2014_smmfactsheet_508.pdf

- van Dooren, T. (2018). Thinking with crows: (Re)doing philosophy in the field. Parallax, 24(4), 439–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/13534645.2018.1546722

- Vecchi, V., & Giudici, C. (Eds.). (2004). Children, art, artists: The expressive languages of children, the artistic language of Alberto Burri. Reggio Children.

- Vecchi, V., & Ruozzi, M. (2015). Mosaic of marks, words, materials. Reggio Children.

- Ximenes, F., Björdal, C., Cowie, A., & Barlaz, M. (2015). The decay of wood in landfills in contrasting climates in Australia. Waste Management (New York, N.Y.), 41, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2015.03.032

- Ximenes, F., Gardner, W., & Cowie, A. (2008). The decomposition of wood products in landfills in Sydney, Australia. Waste Management (New York, N.Y.), 28(11), 2344–2354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2007.11.006

- Zink, T., & Geyer, R. (2019). Material recycling and the myth of landfill diversion. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 23(3), 541–548. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12808