?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Fostering pro-environmental behavior to achieve a sustainable society is one goal of Education for Sustainable Development worldwide. Connectedness with nature positively correlates with pro-environmental behavior and therefore needs to be studied in detail. In this mixed-method study, applying the “Inclusion of Nature in Self” (INS)-scale, we investigated 1) how closely preadolescents from urban middle schools (n = 651, 6th grade) are connected with nature, 2) whether the type of school (general or academic track) or 3) the time spent outdoors influences students’ connectedness with nature. We also explored 4) students’ reasons for their specific INS level and 5) how reasons and levels interconnect. Data show that students’ reported nature connectedness differs significantly with school type and that the reasons for feeling connected to nature are diverse. Positive attitudes and emotions toward nature plus time spent outdoors seem to predict high connectedness with nature, indicating the importance of direct nature experiences.

Introduction

Initiated by the United Nations, the present global action plan to achieve a more sustainable future, “Agenda 2030”, includes 17 interlinked and integrated Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 specific targets (UNESCO., 2015). Researchers identified education as playing a key role in achieving these goals (Otto & Pensini, Citation2017). Therefore, fostering pro-environmental behavior to achieve a more sustainable society is one of the key objectives of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). However, in order to create ESD programs or evaluate them, it is important to understand the factors contributing to individuals’ tendencies to engage in nature-conserving and environmental behaviors (Richardson et al., Citation2020). Previous studies indicate that a connection with nature correlates positively with pro-environmental behavior (Dutcher et al., Citation2007; Kals et al., Citation1999; Kollmuss & Agyeman, Citation2002; Otto et al., Citation2019; Roczen et al., Citation2014) and might therefore be a crucial determining factor to be fostered in formal or informal ESD contexts. Connectedness with nature is not a new construct: Wilson et al. (Citation1995) assumed that humans have an innate tendency to focus on and connect with other living organisms. This attraction to life and life-like processes, termed the biophilia hypothesis by Kellert and Wilson (Citation1993), can be interpreted from an evolutionary perspective and formed an important interdisciplinary research framework. Humans have spent almost all their evolutionary history in a natural environment, while urban life is a phenomenon of the recent past. This attraction, identification and need to connect with nature is thought to have been preserved in our modern psychology (Kellert & Wilson, Citation1993).

Nowadays, humanity is losing its connection to nature (Balmford & Cowling, Citation2006; Kesebir & Kesebir, Citation2017; Soga & Gaston, Citation2021), a phenomenon that is defined as “nature deficit disorder” (Louv, Citation2006). As a reason for that, researchers identified as among some of the key reasons the growing level of digitalization (Kuss & Griffiths, Citation2017; Michaelson et al., Citation2020; Pergams & Zaradic, Citation2007), and a loss of nature experiences (Kareiva, Citation2008; Pyle, Citation1993; Soga & Gaston, Citation2016). Studies show that students recognize more exotic species than local ones (Balmford et al., Citation2002; Genovart et al., Citation2013; Lindemann-Matthies & Bose, Citation2008), indicating that they hardly ever visit nature in their immediate surroundings or have little connection to it. This alienation between humans and nature is one of the potential explanations for the growing environmental problems caused by human activities (Jordan, Citation2009; Ponting, Citation2007; Vining et al., Citation2008).

Nature experiences in childhood and adolescence prove to have significant impact on environmental attitudes, commitments, and actions in adulthood (Cagle, Citation2018; Chawla, Citation2020; Chawla & Derr, Citation2012; Dettmann-Easler & Pease, Citation1999; Duerden & Witt, Citation2010; Tanner, Citation1980; Wells & Lekies, Citation2006). However, other studies show that it is more difficult to change adolescents’ connectedness with nature. (Braun & Dierkes, Citation2017; Clayton, Citation2003; Ernst & Theimer, Citation2011; Gifford & Sussman, Citation2012). Because of these interesting findings, we think it is essential to know more about preadolescents’ connectedness with nature and at the same time gain further insight into possible reasons for their connectedness with and personal concepts of nature. So far, only few studies focus on preadolescents, and to our knowledge, none include qualitative data such as self-reported information about the reasons for young persons’ connectedness with nature (Tseng & Wang, Citation2020; Zylstra et al., Citation2014).

Students’ connectedness with nature

Connectedness with nature is an important construct in environmental education, conservation education, and environmental psychology. Feeling connected to nature is closely related to personal well-being and mindfulness (Zelenski & Nisbet, Citation2014). In terms of environmental education, connectedness with nature is associated with pro-environmental behavior and an increase of positive environmental actions (Kaiser et al., Citation2008). Several studies show that environmental education programs can influence participants’ connectedness with nature in a positive way (Braun & Dierkes, Citation2017; Kossack & Bogner, Citation2012; Liefländer & Bogner, Citation2018). In the last 20 years, many instruments were developed to measure people’s connectedness with nature. The most important instruments in the field of Connectedness with Nature are presented in .

Table 1. Overview of instruments measuring Connectedness with Nature.

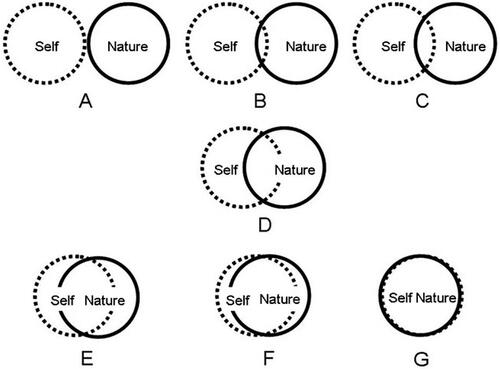

In our study, we refer to the inclusion with nature concept by Schultz (Citation2002) and applied his “Inclusion of Nature in Self” (INS) scale (Schultz, Citation2002) to assess students’ perceived connectedness with nature. The scale reflects the cognitive dimension of connectedness with nature by indicating the amount of overlap of a person’s cognitive representation of self with his or her cognitive representation of nature. The more overlap both have, the more a person defines him- or herself as part of nature. The scale is simple to apply, and its test-retest correlations have provided very high reliability between measurement times (Schultz et al., Citation2004). Also, compared to other multiple-item scales, the INS scale has been found to be accurate for measuring individual differences in connectedness with nature (Liefländer et al., Citation2013). The INS scale correlates with other connection with nature instruments (for example the Environmental Identity scale by Clayton (Citation2003) and the Connectedness to Nature scale by Mayer and Frantz (Citation2004); see ). Moreover, the same scale can be used either for children or adults and results from different cultures are comparable (Salazar et al., Citation2020). Schultz’ concept of Inclusion of Nature (2002) is based on the self-expansion model of close relationships by Aron et al. (Citation1992), which assumes that human relationships are built by integrating others into one’s self. It is represented with a Venn-like diagram with seven increasingly overlapping circles. The total area remains always constant. A perception of closeness as an overlapping “self” with another person is consistent with similar approaches in the social psychology literature (Aron et al., Citation1992). Schultz (Citation2002) extended this model in a way that it enables the integration of characteristics and properties of nature into oneself. He, too, chose circles of equal size for the increasing overlaps. The model is built on the idea that people actively take care of nature if it is perceived as part of themselves.

Research reveals that several factors have an impact on connectedness with nature: gender, age, occupation, ethnicity, and time spent in nature. Regarding time spent in nature, for example, studies show that it is a key factor for a greater connectedness with nature (Braun & Dierkes, Citation2017; Cheng & Monroe, Citation2012; Nisbet et al., Citation2009; Schultz & Tabanico, Citation2007). However, only a few studies so far investigated the possible influence of students’ academic level on their connectedness to nature. Most studies done to date in environmental education research, especially those with questionnaires or tests, focus only on academic track schools (i.e. university-preparatory schools), often due to easier accessibility to the schools and higher reading abilities by the students. In general, knowledge and attitudes of general-education-track students are greatly understudied. This might be a significant mistake, since a study from Liefländer et al. (Citation2013) shows that academic track students are more connected with nature than general track students. In the study reported here we therefore explicitly chose to focus on both groups. To our knowledge, our study is the first in Austria that also includes data of general track students and compares the two cohorts. In Austria, after completing elementary school in 4th grade, students choose between two types of schools: a general track middle school or an academic track middle school. The former usually continue education in vocational schools and the latter mostly continue to college/university (Oberwimmer et al., Citation2019). In general, students are separated based on their academic achievement in elementary school. Usually, students in general track schools generally stem from lower income households and their parents more often have a nonacademic background (no college or university degree) (Pisa, Citation2019). The curricula in both types of middle school are equivalent.

The aim of this study is to investigate in depth the connectedness with nature of middle school students in urban areas, looking at both tracks of education, general and academic. Here, we especially focus on their individual understanding, on reasons for and perception of their own connectedness with nature, as connectedness with nature is a key predictor of pro-environmental behavior (Kollmuss & Agyeman, Citation2002; Otto & Pensini, Citation2017; Roczen et al., Citation2014).

Our research questions are 1) How closely are Austrian middle school students (grade 6) connected with nature? 2) Does the type of school (i.e. general or academic track) have an influence on students’ connectedness with nature? 3) Does the frequency of time spent in nature have an influence on students’ connectedness with nature? 4) Which reasons do they report to explain their level of connectedness with nature? And 5) How do their reasons and their level of connectedness interconnect?

Materials and methods

In this study, we used a mixed-method approach. Next to applying quantifying methods in order to analyze the INS data, qualitative inductive research methods were used, too, in order to gain an in depth insight into students’ explanations about their levels of connectedness (Mayring, Citation2010).

Sample and methods

The sample consists of 651 students from ten schools in Vienna, Austria (grade 6, Mage: 11.63, SD: .85, 45.1% female). 347 students from four general track schools (Mage: 12.04, SD: .81, 45.5% female) and 302 students from six academic track schools (Mage: 11.28, SD: .51, 46.0% female) participated in the study. 70.4% of students from general track schools and 49.3% of students from academic track schools have a migration background. The definition of a migration background is applied to students whose mother and father were both born in a country where students took the questionnaire (Schleicher, Citation2019). However, the majority of students from both type of schools were born in Austria (85%). 13.3% of general track students’ parents and 57.6% of academic track students’ parents finished tertiary education. Most parents of students from general track schools work in blue-collar occupations (90.2%), while the majority of parents of students from academic track schools are employed as semi-skilled professionals (32.8%) or as managers and professionals (52.8%). The questions on migration background and socio-economic status were selected and analyzed based on the questions used in PISA (Schleicher, Citation2019). Data collection was carried out in 2020. The criteria for school selection were their willingness to participate in the research project and had to be either a general track or an academic track school. All schools are public middle schools that are supported financially by the government and provide free education. None of the schools has a focus on specific subjects or offer special education programs. Prior to participation, students were informed about the aims of the research, duration, procedure, and anonymity of the data. Participation was always voluntary, and only students whose parents signed consent forms to participate in the study, were included in the data analysis. Data was collected and analyzed anonymously. Under Austrian law, approval by an ethics committee was not necessary as this study did not involve patients, was noninvasive, and participation was voluntary and anonymous.

Measurements

Students completed an anonymous paper-and-pencil questionnaire. The questionnaire included the environmental attitudes scale “Inclusion of Nature in Self” (INS) (Schultz, Citation2002), as a direct, explicit measure for assessing cognitive beliefs and detecting perceived connectedness with nature. The INS relies on self-report responses and uses a graphical one-item design, represented by seven circle pairs, labeled “self” and “nature” which differ in the degree of overlap (). Students were asked to mark one circle pair in response to: “How interconnected are you with nature? Choose the picture which best describes your relationship to nature.” Scores range from 1 to 7, with the least overlapping circle receiving a score of 1 (complete separation from nature) and the most overlapping circle receiving a score of 7 (complete connection to nature) (see Schultz (Citation2002) for details). Four weeks after the INS test, we conducted a retest with 10% of the students. The test-retest reliability for the INS scale provided a Cronbach’s α 4-week retest = .90 (N = 53) which is in line with test-retest corrections from Schultz et al. (Citation2004) Cronbach’s α 1-week retest = .90, Cronbach’s α 4 -week retest = .94 and Liefländer et al. (Citation2013) Cronbach’s α 4-week retest = .93. Feedback from students in a pilot phase (n = 57, Mage: 12.08, SD: .85) did not highlight any problems with understanding the INS scale and the accompanying open question.

Figure 1. One-item INS scale by Schultz (Citation2002).

To further examine students’ individual understanding, perception, and reason for connectedness with nature, the item was accompanied by an open question in which students were asked to explain why they chose their specific INS level. Students were also asked to provide some general socio-demographic information and questions about personal habits concerning nature, such as time spent outdoors.

Data analysis

The INS scale data from the questionnaire were analyzed using the statistical program IBM SPSS Statistic, version 28. Data obtained were processed at the level of descriptive and inferential statistics. Because INS is measured on an ordinal scale we used the Mann-Whitney U test to analyze the differences between students’ connectedness with nature with respect to type of school, frequency of spending time in nature and age of students. The level of significance is .05; the corresponding confidence level is 95%. The effect size r was calculated according to Field (Citation2013) r = z/

, with .10 as a small, .30 as a medium and .50 as a large effect (Cohen, Citation1960). Spearman rank correlation was calculated for exploring correlations between connectedness with nature level, type of school, time spent in nature and age of students. A total of 658 students’ written answers were transcribed, translated from German to English and subsequently analyzed using an inductive-deductive analysis approach performing a Qualitative Content Analysis (Kuckartz & Rädiker, Citation2019). The analysis was conducted with the Qualitative Data Analysis (QDA) software MAXQDA 2022, which also allowed a semi-quantitative analysis (e.g., occurrence of technical terms). Answer categories are derived from the material itself, performing a qualitative in-depth analysis of the data and inductively established coding categories defined by patterns that emerged in the data. Some categorizations were later redefined and added based on data material and the theoretical framework. Data that represent less than 2% of answers were not coded. The developed coding guideline includes a clear category definition and an example from the students’ answers for each category to verify the transparent categorization. Ten main categories were established, referring to the students’ responses. Statements were coded into several categories if they applied to more than one category. Anchor examples are cited from the original questionnaires (see ). The first author and two trained research assistants applied the coding guideline, which was continuously adapted throughout the analyzing process, involving iterative reviews, discussions, categorizing, and coding. We conducted an interrater-reliability test, using Kendall’s-W in MAXQDA and a randomly selected sample of 20% of all questionnaires (Kuckartz & Rädiker, Citation2019; Mayring, Citation2010). Kendall’s W revealed an “almost perfect” (Cohen, Citation1960) result (W = .85).

Table 2. Coding guideline (n = 651, 658 statements) and examples from the students’ answers for each category. Data that represent less than 2% of answers were not coded.

Finally, the categories were related to the INS statements to investigate possible connections between the students’ connectedness to nature and their self-perceived reasons. Based on the model from Kossack and Bogner (Citation2012), three response categories were formed for the purposes of data analysis: low connectedness level (1-3); medium connectedness level (3); and high connectedness level (4-7).

Results

Results are divided into two main sections: quantitative results of the middle school students’ connectedness with nature and qualitative results of students’ explanation of their connectedness with nature.

Quantitative results: Middle school students’ connectedness with nature

The study shows that Austrian middle school students from an urban area in grade 6 have on average medium to high INS-scores (M = 4.30, SD = 1.70, n = 651).

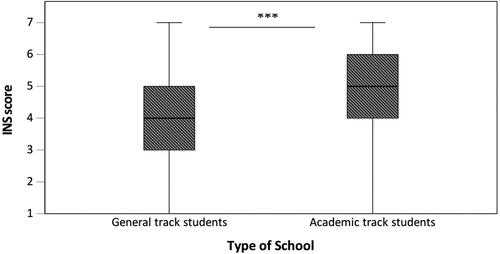

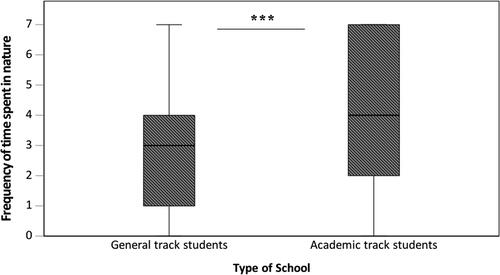

Figure 2. Differences in INS scores according to the type of school (n = 651; general track students (n = 347), academic track students (n = 302), Mann-Whitney U, ***significant at p <.001.

Our comparison of the INS scores (7-points scale) showed that general track students scored significantly lower on the INS scale (n = 354; Mdn = 4.00) compared to academic track students, r = 0.14) see .

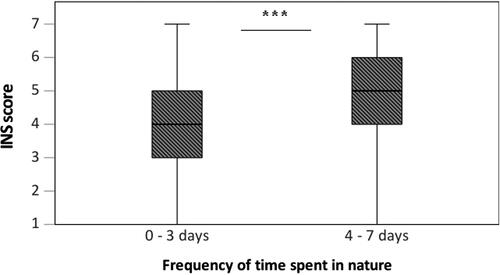

General track students are on average older (n = 354, Mage: 12.04, SD: .81) compared to academic track students (n = 297, Mage: 11.28, SD: .51). To find out whether the age difference introduced bias into the main analysis, we performed an additional analysis, including students in the 11-12 age range only from both cohorts. Results showed that the difference was still statistically significant between groups r = 0.11), therefore we can conclude that age is not a predictor. Regarding their time spent in nature, results show that students spending less time in nature (0 - 3 days) (n = 326; Mdn = 4) have a significantly lower INS score than students who spent more time in nature (4—7 days) (r = 0.23), see .

Figure 3. Differences in INS scores according to frequency of time spent in nature (n = 651), Mann-Whitney U, ***significant at p <.001.

When comparing students’ effective time spent in nature (0 - 7 days), results show that general track students (n = 332; Mdn = 3) spent significantly less time in nature than academic track students (r = .30), see .

Figure 4. Differences in frequency of time spent in nature according to the type of school (n = 651; general track students (n = 347), academic track students (n = 302), Mann-Whitney U, ***significant at p <.001.

Next to that, our comparison of frequency of time spent in nature (0-7 days) showed that younger students spent significantly more time in nature (n = 510, Mdn = 3.00) compared to older students (r = 0.17). Additionally, younger students (n = 537, Mdn = 4.00) have a statistically significantly higher INS-score compared to older students (r = 0.15).

Spearman’s rank correlation was computed to assess the relationship between reported INS-scores, time spent in nature, type of school, and age of students. The results are presented in . The INS is significantly positively correlated with frequency of time spent in nature rs (651) = .378, p < .001, type of school rs (651) = .144, and significantly negatively correlated with students’ ages rs (651) = −.165, The frequency of time spent in nature is significantly positively correlated with the type of school rs (651) = .300, and significantly negatively correlated with student age rs (651) = −.250, Type of school is significantly negatively correlated with student age rs (651) = −.503.

Table 3. Correlation between INS, time spent in nature and school (n = 651), Spearman’s, ***significant at p <.001.

Qualitative results: Students’ explanations of their connectedness with nature

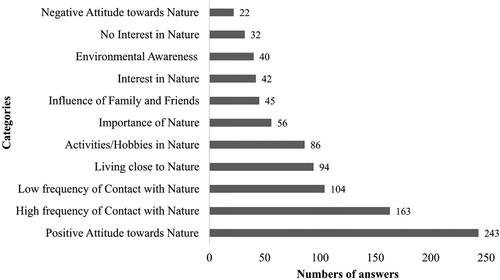

When students were asked to explain their connectedness with nature, 658 answers were received in total. The responses were assigned to a total of eleven main categories. illustrates how often each category was found in the students’ answers.

Positive attitudes toward nature

Positive attitudes toward nature are the most frequently mentioned explanations for students’ connectedness with nature (25.9% of all answers). Students express various positive emotions, such as sympathy, empathy, and respect toward nature. 46.2% of answers in this category stem from general track students and 53.8% from academic track students. Examples included:

I love animals like deer, eagles and snakes. Nature is always quiet. male, 11 yrs, academic track

Because I love nature, plants, trees, fresh air. male, 12 yrs, general track

Students also mention esthetic components of nature such as:

Nature is beautiful. female, 11 yrs, academic track

I think trees and plants are beautiful! male, 11 yrs, general track

High frequency of contact with nature

High frequency of contact with nature is students’ second-highest mentioned category (17.4% of answers) as explanation for their INS score. 24.6% of answers in this category are mentioned by general track students and 75.4% by academic track students. Time spent outdoors is an important value for these students. For example:

Because I much prefer being outside and enjoying nature than being at home. male, 12 yrs, academic track

Because I am often in nature (forest, meadow). female, 11 yrs, general track

Low frequency of contact with nature

The third most mention explanation (11.1% of all answers) is a low frequency of contact with nature. 44.2% of answers in this category are from general track students and 55.8% are from academic track students. Students often explain the low frequency of nature contact with a lack of time, as can be seen here:

I am rarely in nature because I don’t have the time. female, 11 yrs, general track

Because I have to go to school every day and only have time to go outside at the weekend, sometimes not. male, 13 yrs, academic track

On the contrary, some students explain that they spend most of their free time indoors on purpose. Often, they mention screen time as their reason for a low frequency of contact with nature:

I spend most of my time at the computer or mobile phone and rarely go outside. male, 11 yrs, general track

I prefer to stay at home and play computer games. male, 14 yrs, general track

I like to play games on my smartphone, and when I get bored, I go into nature. male, 11 yrs, academic track

Living close to nature

Some students explain their connectedness with nature by referring to living close to nature (10% of all answers). 30.6% of answers in this category are from general track students and 69.4% are from academic track students. They live close to nature, or they have a garden, plants or pets:

We have many plants on the patio, and I spend a lot of time there. male, 11 yrs, academic track

Because I love nature and I have pets at home. male, 11 yrs, general track

Every day after school I go into the forest close to our garden. In the garden, we have raised garden beds and apple trees. male, 11 yrs, academic track

Some students mention living close to a forest or park:

I go to the forest three times per week. male, 11 yrs, general track

Because I often go in the park after school. female, 11 yrs, academic track

Some students mention they had lived close to nature before they moved to the city:

In Vienna, I do not feel so close to nature, but in Poland, where I lived before, we lived in a village, and I felt more connected with nature. female, 12 yrs, general track

In the land where my parents come from, we have a house with a garden and trees. I go there twice a year. male, 12 yrs, academic track

Activities/hobbies in nature

Students also describe their connectedness with nature referring to activities and hobbies undertaken in nature (9.2% of answers). 16.1% of answers in this category are from general track students and 83.9% are from academic track students. For example, they mention playing in nature or practicing hobbies in nature:

I often go outside with my friends, and I often play in the forest. male, 12 yrs, general track

Doing sports in nature (for example because I love to go mountain biking). male, 12 yrs, academic track

Because I like to walk in nature and imagine what is there, for example insects, beetles, trees, plants, waters and so on. female, 11 yrs, academic track

Importance of nature

Only a few students (6.1% of answers) describe their connectedness with nature from an ecocentric point of view on nature. 93.2% of answers in this category are from general track students and 6.8% are from academic track students. In their reasoning, nature is not only important for humanity but also for other living organisms:

Because the environment is important for all of us and I would like to help. male, 13 yrs, general track

Because nature is important for humanity, and if you throw waste into the sea, 1000 fish (and other animals) can die. female, 12 yrs, academic track

Some students mention air and oxygen:

Nature is important for us because trees produce oxygen, and we need that. male, 12 yrs, general track

I want to do something about not cutting down trees because the leaves make oxygen and if we do not have leaves on earth or they cannot grow, we do not have fresh oxygen. female, 11 yrs, general track

Influence of family and friends

Only 4.9% of the answers refer to the influence of their close family, grandparents and friends when describing their connectedness with nature. 37.8% of answers in this category are from general track students and 62.2% are from academic track students.

Because I always go outside with my family. female, 11 yrs, general track

I go hiking with my mother every free afternoon. female, 12 yrs, academic track

It is best to be outside and with friends. female, 11 yrs, academic track

Interest in nature

We sorted 5.5% of answers into the category interest in nature. 79.2% of answers in this category are from general track students and 20.8% are from academic track students. Students describe their connectedness as curiosity about nature; they would like to learn more about nature:

Because I am interested in nature and can learn new things. female, 11 yrs, general track

Because I am very often in nature, and I am interested in what happens there. male, 12 yrs, academic track

Environmental awareness and protection

We allocated 3.3% of answers to the category environmental awareness and environmental protection. 75.0% of answers in this category are from general track students and 25% are from academic track students. Some students mention a loss of biodiversity:

I do not want to pollute our world so that animals will not die, for example polar bears, penguins. female, 11 yrs, academic track

Because the environment is very important, and many animals are becoming extinct, I love animals so I will do everything in my power to save them. male, 12 yrs, general track

Some students mention pro-environmental behavior:

Because I am careful with nature, so I take care of nature. female, 12 yrs, general track

Because the environment is important for all of us, and I would like to help. male, 11 yrs, academic track

No interest in nature

Only a few answers (4.3%) were categorized into the category “No Interest in Nature”. 90.6% of answers in this category are from general track students and 9.4% are from academic track students. Some examples are:

Because unfortunately, I do not care! male, 11 yrs, general track

Because I am more interested in other things than nature. female, 13 yrs, academic track

Negative attitudes toward nature

Only a very few students (2.3% of answers) express negative emotions toward nature, such as fear or boredom. 56.6% of answers in this category are from general track students and 44.4% are from academic track students.

Because it is boring. male, 11 yrs, general track

I am afraid of nature. male, 12 yrs, academic track

Some students mentioned a dislike of insects:

I hate insects and I don’t care about nature. male, 13 yrs, general track

I do not like nature because you can find many insects there. female, 11 yrs, academic track

Linking students’ explanation of their connectedness with nature with their INS level

In a more in-depth analysis, we compared students’ explanation of their connectedness to nature with their INS level ().

Table 4. Students’ Explanations of their Connectedness with Nature in comparison to their INS level, Pearson’s Chi-square test p. significant p-values are shown in bold, difference is significant at level p <.001**.

Clearly, students with a high INS score (5-7) and a middle INS score (4) particularly often stated positive attitudes toward nature and reported higher frequencies of contact with nature as the reason for their level of connectedness with nature. Students with lower INS scores (1-3) most often mentioned low frequencies of contact with nature, and consequently, only a few students with lower INS scores mentioned activities in nature to explain their connectedness with nature. Students with lower INS scores often reported no interest in nature as an explanation for their low connectedness with nature (). Students with a high INS score (5-7) and middle INS score (4) mostly explained their connectedness with living close to nature, activities, and hobbies in nature (anthropocentrism). In the case of ecocentrism, we found the importance of nature mostly mentioned by students with high INS scores. Moreover, the category “importance of nature” shows the biggest gap between students with high, middle, and low INS scores. Difference between students with different INS levels (high, middle, and low) and categories based on their explanation for nature connectedness proved to be statistically significant, for all categories except for the categories “Influence of Family and Friends” as well as “Interest in Nature”. ().

Discussion

Young people are vital stakeholders in behavioral change toward a more sustainable future. Connection with nature is considered an important factor in behavioral change toward a more sustainable lifestyle. Studies indicate that it correlates positively with self-reported pro-environmental behavior (Dutcher et al., Citation2007; Kals et al., Citation1999; Kollmuss & Agyeman, Citation2002; Otto et al., Citation2019; Roczen et al., Citation2014) and might therefore be a determining factor that should be fostered in formal or informal ESD contexts. Because of this, the aim of this study was to investigate in depth the connectedness with nature of middle school students in grade 6 in urban areas in Austria. We chose grade 6 because so far, only few studies focus on preadolescents, and to our knowledge, none include qualitative data (Tseng & Wang, Citation2020; Zylstra et al., Citation2014). We were particularly interested in general track students who are still greatly understudied. We were also interested in comparing the two school tracks, general and academic. Our second focus was an in-depth analysis of students’ individual reasoning and personal perceptions of their own connectedness with nature.

Middle school students’ connectedness with nature

In answer to our first question about how Austrian middle school students are connected with nature, the results show that participating middle school students in Austria show middle to high INS scores (M = 4.45), which is in line with previous studies (Braun & Dierkes, Citation2017; Bruni et al., Citation2017; Fränkel et al., Citation2019; Liefländer & Bogner, Citation2014). Bruni and Schultz (Citation2010) reported that 10- to 11-year-old students from California (U.S.) had INS scores of 4.45 on average, which is almost the same average level of connectedness as our Austrian students. It indicates that preadolescent students are still more connected with nature than adults or teenage students over 12 years.

Middle school students’ connectedness with nature related to the type of school

However, in our present research, although all students were in grade 6, their age ranged from 10 to 14 years. This was mostly due to older students in the general track school. In Austria’s school system, students must repeat the whole grade if they fail several classes. Students who attend grade 6 at 13 years or older repeated at least one grade. This may have many reasons, above all presumably language barriers: students with immigrant roots on average have a poorer knowledge of the German language and thus have more difficulties following the lesson. Thus, sixth-grade students in our sample that stem from academic track schools were on average younger than in the general track schools. Related to age, we found that younger students (11-12 years) had significantly higher INS scores than older students (13-14 years). Similar results were reported by previous studies (Braun & Dierkes, Citation2017; Liefländer & Bogner, Citation2014), suggesting that environmental programs are more effective with students under 12. We found a statistically significant difference concerning the INS level between students in general and academic track schools. To find out whether the above reported age difference introduced bias to our results, we performed an additional analysis, only including 11-12-year-old students from both cohorts. Results showed that the difference was still statistically significant between groups, therefore we can conclude that age is not a predictor in our study groups. The differences in connection with nature among general and academic middle school students was also found in a German study conducted by Liefländer et al. (Citation2013), that found statistically significant differences in connection with nature in favor of academic track middle school group of students.

Middle school students’ connectedness with nature related to time outdoors

In addition, our results also show that students from academic track schools spent more time in nature than general track students. Time spent outdoors is a strong predictor for connectedness with nature (Fränkel et al., Citation2019; Schultz, Citation2002). Hence, the differences in INS outcomes between students of these two types of schools require a more complex explanation. Austria is one of eight countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), where students are differentiated at age 10 based on their achievements in a primary school (Pisa, Citation2019). However, formal entrance exams are not obligatory, and parents can influence the school choice. Often parents with a higher socioeconomic status prefer that their children attend higher-achieving schools (academic track schools) that cater to students who are on track to attend university (Oberwimmer et al., Citation2019). Parents with lower income and lower levels of formal education often have fewer opportunities to attend recreational outdoor activities in nature outside of urban areas, which could partially explain our findings. In our study, students from general track schools reported spending more time indoors and rather attend activities in local city parks. Studies from Seattle and San Diego (U.S.) (Tandon et al., Citation2012) and Finland (Kantomaa et al., Citation2007) also show, that students with a lower socio-economic status spend more time indoors. General-track students also show lower INS score in studies from Liefländer et al. (Citation2013), and Bruni and Schultz (Citation2010); their results indicate that higher INS scores of students are positively related to a higher level of education of their parents. One solution might be that these deficits could be partially offset by education. Formal or non-formal education programs alike should offer more opportunities to increase direct nature experiences (for example field trips or camps) for this group of students. This could include forests and meadows, but also nature environments in urban areas, like parks and gardens. ESD with direct nature experiences should be an explicit part of the curriculum for general track middle school students and should not merely be considered an extra-curricular activity. Here we propose place-based education, an educational approach based on the idea of actively linking schools with their local communities (Cincera et al., Citation2019; Smith, Citation2002; Sobel, Citation2004). Additionally, it is essential that students can also experience nature in their free time and not only in an education context. Here, federal states, cities, and municipalities could provide free offers for nature experiences such as free transport and entrance to national parks, nearby forests, or lakes. These offers should not only be granted for students alone but for whole families and communities.

One of the reasons for differences in INS scores between students could also be due to diverse cultural backgrounds. Most of the participating students (83%) were born in Austria but 70.4% of student from general track schools and 49,3% of students from academic track schools have migration backgrounds. Some students who were not born in Austria mention they had lived close to nature before they moved to Vienna (see student’s answers in chapter “Lining close to nature”).

Middle school students’ explanation of their connectedness with nature

An in-depth qualitative analysis of the students’ individual reasoning and personal perceptions of their connection with nature reveals different understandings of the concept of connection to nature. Our findings show that a higher frequency of contact with nature and a positive attitude toward nature are the most common explanations of students’ connectedness to nature. The higher the frequency of contact with nature is also consistent with the quantitative part of our results. Students’ reasons for connectedness with nature are very diverse and interconnected with their level of connectedness with nature.

Students that are more connected with nature mention frequent activities in nature and often explain that they live close to it. Students less connected to nature rarely mentioned activities in nature, which could be explained by the so-called “extinction of experiences” (Pyle, Citation1993). Studies show that people who live far from nature or close to degraded areas spend less time outside (Neumayer, Citation2003; Soga & Gaston, Citation2016). However, that should not be the case in our study, since the study was conducted in Vienna, where 53% of the area is covered with green areas and water bodies (Vienna City Statistical Yearbook, Citation2020). Students who explained their low INS score with a low frequency of contact with nature often mentioned that they preferred to spend their time online or at the computer and smartphone and that they do not have any time for nature, here we found no difference between general and academic track schools. Bruni and Schultz (Citation2010) and Larson et al. (Citation2019) also found that students who reported spending more time outdoors have a higher connectedness with nature. Time spent in nature is proven to be one of the most important factors affecting students’ connectedness with nature (Fränkel et al., Citation2019; Kals et al., Citation1999; Mayer et al., Citation2009; Schultz & Tabanico, Citation2007). The issue here is how students spend their time in nature and what they understand by the term nature. Understanding the concept of nature is essential for understanding the concept of connectedness to nature. The links in the perception of the concept of nature and connectedness to the perception of connectedness to nature need to be further explored. In conclusion, we would like to add that the results of our study have clearly shown the importance of complementing quantitative scales with open-ended questions to clarify students’ understanding and perception of constructs, in our case, connectedness to nature. Additionally, different reasons lead students to the same result on the INS scale; in order to find out how formal or informal teaching interventions can possibly increase connectedness with nature or pro-environmental behavior we need to know their motivations, reasons, and perceptions of connectedness with nature in greater detail.

Limitations

The study was conducted with students living in an urban area, but it would be interesting to compare the results with preadolescents from rural areas, too. To get a better insight into students’ connectedness with nature, various scales about connectedness with nature could be implemented in future research. One of the limitations of the study is that we did not conduct additional interviews with the students in order to get more in-depth information about their personal conceptualization of the concept connectedness to nature. For example, it would have been interesting to find out more about the concept of the term nature of those students that indicated a low INS score and reported that they do not care about nature. In general, more qualitative data about students’ understanding of the concept of nature and about their activities in nature would additionally help in understanding preadolescents’ connectedness with nature, especially to better understand the difference between the two types of schools. A limitation of the study is also that we were not able to further investigate the cultural background of students that were not born in Austria. Students’ roots in other countries might also be a reason for the differences in their level of connectedness with nature and understanding of connectedness with nature (Fränkel et al., Citation2019). Another limitation might be the fact that when students were asked about their time spent outdoors, they were to report how many days per week on average they spent outside in nature. Larson et al. (Citation2019) suggests that it is better to ask about hours per day; this way students can more easily calculate their time outdoors. Also, instead of questionnaires using an open-ended question, it would be interesting to use nature diaries, in which students can describe their time outdoors, their activities and their connectedness with nature in detail (Ardoin et al., Citation2020; Michaels et al., Citation2007).

Conclusion

Our study shows that students from urban middle schools in grade 6 on average have medium to high INS scores. Academic track students’ connectedness with nature was significantly higher than general track students. Also, the more time students spent outdoors the higher they report their connection to nature. Therefore, especially general track students at preadolescent age might benefit from more time in nature, preferably through an environmental program with direct nature experiences. This is also indicated in students’ explanations for their self-reported connectedness with nature. Therefore, we suggest that direct nature experiences should be part of the curriculum for middle school students, not only in biology lessons but possibly interdisciplinary based on the place-based education approach, where students can learn and be in touch with their local environment. Our research also indicates that the reasons for feeling connected to nature are diverse and seem to highly depend on positive attitudes toward nature and time spent in nature. Here, we suggest that additional open questions should accompany quantitative research scales more frequently to get a broader and more detailed view of the topic. Our research is based on the INS Model, in which the main idea is that people actively protect nature only if they perceive themselves as part of it (Schultz, Citation2002). Our results indeed show that students who perceive themselves as part of nature often describe their high connectedness with activities and hobbies in nature. Students who live close to nature detect the importance of nature for humans and other living organisms. Therefore, loving and feeling connected to one’s (local) environment might apparently help to protect nature more effectively. However, at the same time our data suggest that it probably needs a whole-of-society approach with policy decisions that enable people to spend (more) time in nature, for example through free education programs based on the place based education. This will become increasingly important in the near future as it is estimated that by 2050 two out of three people are likely to live in cities or other urban centers (United Nations Population Division, Citation2019), where access to nature will be even more difficult.

Acknowledgement

We thank Linda Hämmerle, Helene Parzer, and Christina Priller for help with the data collection as well as all participating students and their teachers for contributing to this study.

References

- Ardoin, N. M., Bowers, A. W., & Gaillard, E. (2020). Environmental education outcomes for conservation: A systematic review. Biological Conservation, 241, 108224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108224

- Aron, A., Aron, E. N., & Smollan, D. (1992). Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(4), 596–612. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.596

- Balmford, A., Clegg, L., Coulson, T., & Taylor, J. (2002). (2367). Why conservationists should Heed Pokémon. Science (New York, N.Y.), 295(5564), 2367–2367. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.295.5564.2367b

- Balmford, A., & Cowling, R. M. (2006). Fusion or failure? The future of conservation biology. Conservation Biology. 20, 695. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00434.x

- Braun, T., & Dierkes, P. (2017). Connecting students to nature - how intensity of nature experience and student age influence the success of outdoor education programs. Environmental Education Research, 23(7), 937–949. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1214866

- Bruni, C. M., & Schultz, P. W. (2010). Implicit beliefs about self and nature: Evidence from an IAT game. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(1), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.10.004

- Bruni, C. M., Winter, P. L., Schultz, P. W., Omoto, A. M., & Tabanico, J. J. (2017). Getting to know nature: evaluating the effects of the Get to Know Program on children’s connectedness with nature. Environmental Education Research, 23(1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2015.1074659

- Cagle, N. L. (2018). Changes in experiences with nature through the lives of environmentally committed university faculty. Environmental Education Research, 24(6), 889–898. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2017.1342116

- Chawla, L. (2020). Childhood nature connection and constructive hope: A review of research on connecting with nature and coping with environmental loss. People and Nature, 2(3), 619–642. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10128

- Chawla, L., & Derr, V. (2012). The development of conservation behaviors in childhood and youth.

- Cheng, J. C. H., & Monroe, M. C. (2012). Connection to nature: Children’s affective attitude toward nature. Environment and Behavior, 44(1), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916510385082

- Cincera, J., Valesova, B., Krepelkova, S., Simonova, P., & Kroufek, R. (2019). Place-based education from three perspectives. Environmental Education Research, 25(10), 1510–1523. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1651826

- Clayton, S. (2003). Environmental identity: A conceptual and an operational definition. In S. Clayton & S. Opotow (Eds.), Identity and the natural environment: The psychological significance of nature, 45–65. MIT Press.

- Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104

- Dettmann-Easler, D., & Pease, J. L. (1999). Evaluating the effectiveness of residential environmental education programs in fostering positive attitudes toward wildlife. The Journal of Environmental Education, 31(1), 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958969909598630

- Duerden, M. D., & Witt, P. A. (2010). The impact of direct and indirect experiences on the development of environmental knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(4), 379–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.03.007

- Dutcher, D. D., Finley, J. C., Luloff, A. E., & Johnson, J. B. (2007). Connectivity with nature as a measure of environmental values. Environment and Behavior, 39(4), 474–493. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916506298794

- Ernst, J., & Theimer, S. (2011). Evaluating the effects of environmental education programming on connectedness to nature. Environmental Education Research, 17(5), 577–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2011.565119

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Sage Publications Ltd.

- Fränkel, S., Sellmann-Risse, D., & Basten, M. (2019). Fourth graders’ connectedness to nature – Does cultural background matter? Journal of Environmental Psychology, 66, 101347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.101347

- Genovart, M., Tavecchia, G., Enseñat, J., & Laiolo, P. (2013). Holding up a mirror to the society: Children recognize exotic species much more than local ones. Biological Conservation, 159, 484–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2012.10.028

- Gifford, R., & Sussman, R. (2012). Environmental attitudes. In S. D. Clayton (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of environmental and conservation psychology (pp. 65–80). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199733026.013.0004

- Jordan, M. (2009). Nature and self—An ambivalent attachment? Ecopsychology, 1(1), 26–31. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2008.0003

- Kaiser, F., Roczen, N., & Bogner, F. (2008). Competence formation in environmental education: Advancing ecology-specific rather than general abilities. Umweltpsychologie, 12 (2), 56–70. https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-9249

- Kals, E., Schumacher, D., & Montada, L. (1999). Emotional affinity toward nature as a motivational basis to protect nature. Environment and Behavior, 31(2), 178–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/00139169921972056

- Kantomaa, M., Tammelin, T., Näyhä, S., & Taanila, A. (2007). Adolescents’ physical activity in relation to family income and parents’ education. Preventive Medicine, 44(5), 410–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.01.008

- Kareiva, P. (2008). Ominous trends in nature recreation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105, 2758. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0800474105

- Kellert, S. R., & Wilson, E. O. (1993). The biophilia hypothesis (Vol. 4). Island Press.

- Kesebir, S., & Kesebir, P. (2017). A growing disconnection from nature is evident in cultural products. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(2), 258–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616662473

- Kollmuss, A., & Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 239–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620220145401

- Kossack, A., & Bogner, F. X. (2012). How does a one-day environmental education programme support individual connectedness with nature? Journal of Biological Education, 46(3), 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2011.634016

- Kuckartz, U., & Rädiker, S. (2019). Analyzing qualitative data with MAXQDA. Springer.

- Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(3), 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14030311

- Larson, L., Green, G., & Castleberry, S. (2011). Construction and validation of an instrument to measure environmental orientations in a diverse group of children. Environment and Behavior, 43(1), 72–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916509345212

- Larson, L. R., Szczytko, R., Bowers, E. P., Stephens, L. E., Stevenson, K. T., & Floyd, M. F. (2019). Outdoor time, screen time, and connection to nature: Troubling trends among rural youth? Environment and Behavior, 51(8), 966–991. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916518806686

- Liefländer, A. K., & Bogner, F. (2014). The effects of children’s age and sex on acquiring pro-environmental attitudes through environmental education. The Journal of Environmental Education, 45(2), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2013.875511

- Liefländer, A. K., & Bogner, F. X. (2018). Educational impact on the relationship of environmental knowledge and attitudes. Environmental Education Research, 24(4), 611–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1188265

- Liefländer, A. K., Fröhlich, G., Bogner, F. X., & Schultz, P. W. (2013). Promoting connectedness with nature through environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 19(3), 370–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2012.697545

- Lindemann-Matthies, P., & Bose, E. (2008). How many species are there? Public understanding and awareness of biodiversity in Switzerland. Human Ecology, 36(5), 731–742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-008-9194-1

- Louv, R. (2006). Last child in the woods: Saving our children from nature-deficit disorder (6th ed.) Algonqun Books of Chapel Hill.

- Mayer, F. S., & Frantz, C. M. (2004). The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals feeling in community with nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24(4), 503–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2004.10.001

- Mayer, F. S., Frantz, C. M., Bruehlman-Senecal, E., & Dolliver, K. (2009). Why is nature beneficial?: The role of connectedness to nature. Environment and Behavior, 41(5), 607–643. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916508319745

- Mayring, P. (2010). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken (11., aktualisierte und überarb. Aufl. ed.). Beltz. http://www.content-select.com/index.php?id=bib_view&ean=9783407291424 https://ubdata.univie.ac.at/AC08813808

- Michaels, S., Shouse, A. W., Schweingruber, H. A., & Council, N. R. (2007). Ready, set, science!: Putting research to work in K-8 science classrooms. National Academies Press.

- Michaelson, V., King, N., Janssen, I., Lawal, S., & Pickett, W. (2020). Electronic screen technology use and connection to nature in Canadian adolescents: A mixed methods study. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 111(4), 502–514. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-019-00289-y

- Neumayer, E. (2003). Weak versus strong sustainability: Exploring the limits of two opposing paradigms. In Weak Versus Strong Sustainability: Exploring the Limits of Two Opposing Paradigms. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781781007082

- Nisbet, E. K., Zelenski, J. M., & Murphy, S. A. (2009). The nature relatedness scale: Linking individuals’ connection with nature to environmental concern and behavior. Environment and Behavior, 41(5), 715–740. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916508318748

- Oberwimmer, K., Vogtenhuber, S., Lassnigg, L., & Schreiner, C. (2019). Nationaler Bildungsbericht Österreich 2018. Das Schulsystem im Spiegel von Daten und Indikatoren. Leykam.

- Otto, S., Evans, G., Moon, M., & Kaiser, F. (2019). The development of children’s environmental attitude and behavior. Global Environmental Change, 58, 101947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.101947

- Otto, S., & Pensini, P. (2017). Nature-based environmental education of children: Environmental knowledge and connectedness to nature, together, are related to ecological behaviour. Global Environmental Change, 47, 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.09.009

- Pergams, O., & Zaradic, P. (2007). Videophilia: Implications for childhood development and conservation. Journal of Developmental Processes, 2, 130–144.

- Pisa, O. (2019). Results (Volume I): What students know and can do. OECD Publishing.

- Ponting, C. P. C. (2007). A new green history of the world: The environment and the collapse of great civilizations. Penguin Books.

- Pyle, R. M. (1993). The thunder tree: Lessons from an urban wildland (Vol. 337). Houghton Mifflin.

- Richardson, M., Dobson, J., Abson, D. J., Lumber, R., Hunt, A., Young, R., & Moorhouse, B. (2020). Applying the pathways to nature connectedness at a societal scale: a leverage points perspective. Ecosystems and People, 16(1), 387–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2020.1844296

- Roczen, N., Kaiser, F., Bogner, F., & Wilson, M. (2014). A competence model for environmental education. Environment and Behavior, 46(8), 972–992. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916513492416

- Salazar, G., Kunkle, K., & Monroe, M. (2020). Practitioner guide to assessing connection to nature. North American Association for Environmental Education.

- Schleicher, A. (2019). PISA 2018: Insights and Interpretations. OECD Publishing.

- Schultz, P. W. (2002). Inclusion with nature: The psychology of human-nature relations. In P. Schmuck & P.W. Schultz (Eds.), Psychology of sustainable development (pp. 61–78). Kluwer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-0995-0_4

- Schultz, P. W., Shriver, C., Tabanico, J. J., & Khazian, A. M. (2004). Implicit connections with nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(03)00022-7

- Schultz, P. W., & Tabanico, J. (2007). Self, identity, and the natural environment: Exploring implicit connections with nature. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37(6), 1219–1247. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00210.x

- Smith, G. A. (2002). Place-based education: Learning to be where we are. Phi Delta Kappan, 83(8), 584–594. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170208300806

- Sobel, D. (2004). Place-based education: Connecting classroom and community. Nature and Listening, 4(1), 1–7.

- Soga, M., & Gaston, K. (2016). Extinction of experience: The loss of human-nature interactions. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 14(2), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1225

- Soga, M., & Gaston, K. J. (2021). Towards a unified understanding of human–nature interactions. Nature Sustainability, 5(5), 374–383. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00818-z

- Tandon, P. S., Zhou, C., Sallis, J. F., Cain, K. L., Frank, L. D., & Saelens, B. E. (2012). Home environment relationships with children’s physical activity, sedentary time, and screen time by socioeconomic status. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9(1), 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-9-88

- Tanner, T. (1980). Significant life experiences: A new research area in environmental education. The Journal of Environmental Education, 11(4), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.1980.9941386

- Tseng, Y.-C., & Wang, S.-M. (2020). Understanding Taiwanese adolescents’ connections with nature: Rethinking conventional definitions and scales for environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 26(1), 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1668354

- UNESCO. (2015). Global action programme on education for sustainable development information folder.

- United Nations Population Division. (2019). U. N. N. York.

- Vienna City Statistical Yearbook. (2020). M. d. S. Wien.

- Vining, J., Merrick, M. S., & Price, E. A. (2008). The distinction between humans and nature: Human perceptions of connectedness to nature and elements of the natural and unnatural.

- Wells, N., & Lekies, K. (2006). Nature and the life course: Pathways from childhood nature experiences to adult environmentalism. Children, Youth and Environments, 16(1), 1–24.

- Wilson, E. O., Katcher, A., Kellert, S. R., McCarthy, C., McVay, S., & Wilkins, G. (1995). The biophilia hypothesis.

- Zelenski, J. M., & Nisbet, E. K. (2014). Happiness and feeling connected: The distinct role of nature relatedness. Environment and Behavior, 46(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916512451901

- Zylstra, M. J., Knight, A. T., Esler, K. J., & Le Grange, L. L. L. (2014). Connectedness as a core conservation concern: An interdisciplinary review of theory and a call for practice. Springer Science Reviews, 2(1-2), 119–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40362-014-0021-3