Abstract

Nature degradation is rooted in the disruption of the human-land connection. Its restoration requires the regeneration of environmental stewardship as a way to live within environmental limits, especially for younger generations. In this study we used the implementation of a year-round, non-formal environmental education program during COVID-19 times to explore environmental stewardship in adolescents between 14- and 18-years old from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. Using a qualitative methodology, we mapped expressions of environmental stewardship among local youth. We found several barriers that can be challenged and levers that can be nurtured through inclusive, place-based and collaborative environmental education strategies to foster youth’s environmental stewardship in Colombian’s high-biodiverse regions.

Introduction

Planet Earth is brimming with life, but its wonders are being wiped out by endless economic growth and the consequences of the modern lifestyle of Western civilization (Shivanna, Citation2020). Our resource-demanding lifestyle irremediably alters the natural world, leading ecosystems to disruption and possible collapse (Barnosky & Hadly, Citation2016). During pre-colonial times, different cultures—certainly not all, but many cultures—across the globe lived in harmony with the land (Muller et al., Citation2019), developing an intimate connection with and an understanding of the land, passed on across generations (Salmon, Citation2000). The development of the modern capitalist system rooted on the idea and sentiment that there is an incurable wound that separates nature and humanity (Moore, Citation2015) has created a greedy machine capable of destroying entire ecosystems, has sent to oblivion thousands of species and has jeopardized our own existence; nevertheless, the social forms that condition the human-nature relationship are stiff and extremely resistant to change. As illustrated in the work of Berkes (Citation2012), the Western manual for environmental management based on a reductionist science and financed by colonizers and corporations, dredges the gap between humans and nature when considering humans as separate, superior beings that manage natural resources (Muller et al., Citation2019). In the process, environmental managers created the term “ecosystem services” to justify the need to protect ecosystems, seen as delivering entities for humans, in the framework that conservation needs to “pay off” (Bignall et al., Citation2016). The colonization of nature and associated processes of extraction, exploitation and commodification, have disrupted both connection with and understanding of nature (Muller et al., Citation2019) while Indigenous and local knowledge has been gradually lost and younger generations are at risk of being deprived of the wisdom to preserve biodiversity and create sustainable futures. One consequence of this predatory colonization is the shifting baseline syndrome, where members of each new generation accept the situation in which they were raised as being normal (Soga & Gaston, Citation2018). This means that each new generation accepts as normal a more degraded environment, with more threatened wildlife species and less pristine ecosystems. This has had negative effects on local ecological knowledge and related community based conservation (Papworth et al., Citation2009), bringing intergenerational amnesia, where generations lose connections with nature and awareness of past, healthier ecological conditions, therefore, they have nothing to teach their children in this regard and knowledge extinction occurs because younger generations are not aware of past biological conditions (Louv, Citation2005). This situation is aggravated when environmental education is not place-based and action-oriented, and when it lacks the mission of challenging the status quo of constant growth (Kopnina, Citation2020).

Within the range of mechanisms to restore biodiversity, the regeneration of eco-literacy, sense of place, agency and autonomy within local communities becomes fundamental (Gruenewald, Citation2003). In this paper, this regeneration is connected to environmental stewardship, expressed as a way to live and relate with the environment according to the acknowledgement of the interconnectedness, dependency and reciprocity between natural systems, non-human life and people (Mathevet et al., Citation2018), while rejecting human superiority over nature that grants us the “right” to manage nature. There are several attempts to conceptually frame environmental stewardship (Bennett et al., Citation2018; Enqvist et al., Citation2018; Worrell & Appleby, Citation2000), but in general the links between the theory and practice of environmental stewardship are underdeveloped (Cockburn et al., Citation2019), especially for the elements that can affect it among youth (Andrejewski et al., Citation2011; Pitt et al., Citation2019), and the majority of this research happens in Western countries (Andrejewski et al., Citation2011; Hoover, Citation2021; Pitt et al., Citation2019). A more in-depth understanding of environmental stewardship in youth, especially in highly biodiverse regions, may help inform educational efforts for supporting young people to become stewards of the land (Omoogun et al., Citation2016; Stern et al., Citation2008). We present empirical evidence about real-world expressions, or lack thereof, of environmental stewardship in adolescents as a result of their context. The study focuses on their understanding of environmental stewardship, and their related actions and elements that affect it. The research takes place in the village of La Tagua, in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia, under the scope of a pilot environmental education program run by a national NGO focused on facilitating youth’s environmental stewardship.

The two questions this article seeks to answer are: (1) What does environmental stewardship looks like for adolescents of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia? (2) What are the elements that affect adolescents’ environmental stewardship and its expression? By finding answers to these questions, we hope to not just improve and refine the pilot program under which this research happens, but also to inform the future development of environmental education in the region as a key mechanism for regenerating youth’s environmental stewardship.

The paper is structured as follows. First, we present the study site, along with the positionality of the researchers and the methodology applied, followed by a description of the methods. Next, we discuss the results, and in the final section we reflect on those and the implications for educational endeavors to promote stewardship.

Socio-political context

Colombia is a megadiverse country. The Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (SNSM), the study site, is the home of four different Indigenous tribes, dozens of endemic species of plants, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals, many of them endangered. The Sierra has been categorized as the most irreplaceable nature reserve in the world (Le Saout et al., Citation2013) Biosphere Reserve and World Heritage Site by UNESCO (Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia, Citation2021). This land has been facing habitat loss for the last 50 years (Unidad Administrativa Especial del Sistema de Parques Nacionales Naturales [UAESPNN], Citation2005) matching the start of Colombian armed conflict with the FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia a guerrilla group that used systematic violence to try to reduce power inequalities and benefit the working classes). Although a peace treaty was signed 5 years ago, remnants of violence still prevail in the country, especially in the rural areas.

To explore the environmental stewardship among adolescents in this region, this research focuses on La Tagua, a rural village in the buffer zone of the SNSM Park. This village is within a sub-Andean Forest that hosts many endangered and endemic species of birds, reptiles and frogs. The region was the home of the ancient Tayrona culture, dismembered by the Spanish colonization (Santos, Citation2006) into the four Indigenous tribes (Wiwas, Arhuacos, Kogis and Kankuamos) that populate the land today. Since pre-Hispanic times, these Indigenous groups have lived according to a worldview that dictates the management of their territory along natural cycles, astral movements and climatic patterns (Rodríguez-Navarro, Citation2000) that allowed them to thrive for centuries in the complex ecosystems of the Sierra Nevada.

In the twentieth century, multinational companies arrived at the Sierra to establish the first coffee “fincas” (rural estate or ranch), pushing the Indigenous people toward the highest parts of the Sierra (Huertas Díaz et al., Citation2017). It was during this time that villages as La Tagua were created. There, the local economy is mostly based on coffee farming and subsistence agriculture, with an increasing tourism sector. These coffee farmers coexist with members of the Wiwa and Kogi tribes, who also dedicated to grow coffee or manage small tourist initiatives. An interesting feature of this village that extends to most parts of the Sierra Nevada is that the majority of its inhabitants are Christians (Catholic or Evangelical), including a great number of Indigenous people, a remnant of the colonialist processes that shaped the area. The economic prospects for young people are bleak, with limited occupational opportunities. The living conditions and low-income forces teenagers to drop out of school and work from early age to help the household economy, even sometimes missing school for several weeks to help with the coffee harvest. Local education is of poor quality (OECD, Citation2019), with precarious infrastructure and placeless curricula that ignores Indigenous knowledge and local culture. This results in a lack of learning possibilities, which pushes youth to leave rural areas into the city (Jurado & Tobasura, Citation2012). Add to this a long-lasting social conflict where local illegal armed groups control movements of people and goods, favor private interests and perpetuate dominant social hierarchies (García, Citation2011) while fertile lands have been appropriated by drug-traffickers, cattle farmers and monocultures (Rodríguez-Navarro, Citation2000). Besides, most of the local, non-Indigenous youth are the first (or second max) generation born in these villages. Their parents moved from other regions of Colombia pushed by the aforementioned armed conflict, and they did not have any knowledge about the ecological or cultural functioning of the new place where the settled in. The only source for this knowledge remained in the four Indigenous tribes whom they share land with that still live in the Sierra Nevada, and turns out that most farmers, neither the youth, don’t exchange knowledge with the Indigenous people (pers.obs.).

Researcher positionality & methodology

The Western manual for environmental management is based on reductionist science that dredges the gap between humans and nature by considering humans as separate beings that consume nature (Berkes, Citation2012; Muller et al., Citation2019), degrading and objectifying nature into a commodity providing accountable “services.” How can people become environmental stewards of their land within such a hegemonic narrative? One way is by finding what does environmental stewardship mean to people, which stewardship actions they engage in, and what underpins those. We do so by looking at a local scale with an open view, especially to be inclusive of and sensitive to the Indigenous people participating in this study (Brosius & Russell, Citation2003). We will search for actions, competences, skills, perspectives, interests, and incentives that the youth of SNSM have when relating to nature to comprehend the realities that condition their environmental stewardship.

This research takes a socially-critical and relational perspective, acknowledging the constructivist position that knowledge is created in interaction between the researchers and the researched (Pitard, Citation2017). Counting that a significant number of participants are Indigenous, we assume significant differences between the emic and ethical perspectives which are always present due to our own value systems as researchers (Lett, Citation1990), with the hope that we can stablish a balance that allows us to expand the understanding of the relationship human-nature in the given context so it can be regenerated. Accordingly, this study is guided by a critical phenomenology approach. Based on Wals (Citation1993), we seek to understand how education can serve the community with a goal of understanding, together with the participants, the reality that challenges them to inform the development of educational efforts. This study is embedded in an after-school, non-formal framework, providing a context less subject to constriction, so the participants can express their emotions, thoughts and opinions while integrating the research process within the local reality.

Methods

Participants of the study

The study participants were 25 teenagers between 15 and 18 years old, most of them daughters and sons of coffee farmers, a few of them daughters and sons of cattle ranchers, and 8 of them belonging to the Wiwa and Kogi Indigenous local communities. A common feature among almost all of the participants (including the Indigenous participants except two of them) is that they are Christians (catholic or evangelic). The participants’ names that will appear from this point forward are fabricated names to preserve the teenagers’ anonymity. The study is contextualized in a pilot, non-formal, environmental education program, called the Fly High Bird Club. This program was aimed to support adolescents to become environmental stewards and developed by the first two authors with the support of the Colombian NGO SELVA (where the last author is affiliated). We reached an agreement with the principal of the school of La Tagua to pilot the program with the oldest students, which were informed about the goals, content and the educational activities of the program, and they were invited to participate in the program under their parents’ consent. Throughout the program we put emphasis on ethical issues (confidentiality, safety, respect for their opinion, etc.). For 40 weeks, during the last semester of 2021 and the first semester of 2022 we organized and delivered weekly workshops where we guided participants in a learning process of different skills related to environmental conservation (birdwatching, photography, bird ringing, frog monitoring, citizen science, muralism, community greening, English) while engaging them in the construction of an ecotourism nature trail that mixes cultural, Indigenous, environmental, scientific and educational components. An impression of the activities of this program is provided in . This project-based, place-based, experiential learning allowed us to learn about the participants’ lives, actions, attitudes, ideas they have around nature, and their expressions of environmental stewardship, including the elements behind it.

Methods for data collection

The data was collected via qualitative methods during the 45 workshops that we conducted with the participants as part of the environmental education program described above: participant observations and informal conversations, along with arts-based qualitative methods such as photovoice and mind-mapping. The adoption of many methods assumed that the participants had different expression capabilities, allowing the collection of diverse information to explore their environmental stewardship. The data sets consist of the notes we took both on notebooks and in our phones during and after each activity, as well as the mind maps created by the participants during the mind mapping activity. A short description of how we applied each method follows:

Participant observations and listening: we integrated ourselves in participants’ daily life to document their interactions, routines and actions within a naturalistic setting (McGrath & Laliberte Rudman, Citation2019), especially actions and attitudes around nature, as well as listened to their conversations in various settings, which allowed us to reflect on the differences between what the participants said and did in real life (Forsey, Citation2010).

Informal conversations: they produce data with greater authenticity because they happen naturally, establishing horizontality (Swain & Spire, Citation2020). We oriented the conversations toward participants’ daily life, perspectives, family; how they relate with nature and which elements influence this relationship. When the participants mentioned possible expressions of environmental stewardship that they engaged in, we asked them why they did it. These conversations became fundamental in our interactions with the Indigenous students, who during the activities were reluctant to express, give their opinion and elaborate on them. Nevertheless, during these informal conversations we felt that they were feeling more at ease and comfortable when talking about their lives and understanding of the world.

Photovoice: cameras were given to the participants for 2 weeks to make pictures of their routines, community and territory. At the end, the pictures were explained to the other participants. gives an impression of those photovoice activities.

Mind mapping: mind maps represent interconnected ideas around a central topic (Burgess-Allen & Owen-Smith, Citation2010). With these, we seek to understand their ideas around environmental stewardship. We proposed to participants to develop mind maps around environmental stewardship (“cuidado medioambiental” in Spanish). Students were paired and asked to write new words connected that concept. An impression of the mind mapping is shown in . Afterwards, we asked participants if they had ever engaged in their suggested expressions of stewardship, and why. The data set contains the mind maps and our notes about participants’ reasoning and ideas of environmental stewardship.

Methods for data analysis

The data was analyzed by thematic analysis through manual coding under a constructivist approach for experiences, meanings and reality of participants, and how society and its constructs affect it (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). One drawback of such analysis is it limited interpretative power beyond description if it is not contextualized by using a framework to anchor the analytical claims from the data. We solve this by interpreting the results using Bennett et al. (Citation2018) environmental stewardship framework where actors, capacities, motivations merge under a context to generate environmental steward actions. Actors refer to the people who can carry out environmental stewardship actions. For our case, our actors are the adolescents participating in the study. Capacities are defined in this research as categories of assets that supply the resources or capabilities that can be leveraged to act stewardly, such as: social capital (relationships, networks), cultural capital (knowledge, connection to place, traditions), physical capital (infrastructure and technology), human capital (abilities, education, experiences), financial capital (patrimony, income, credit) and institutional capital (institutions, agency, political and structural processes). Motivations are the incentive structures able to provide power of will for individuals to act as stewards. Here, we distinguish between intrinsic (internal stimulus that correspond to emotional or psychological needs, such as sense of place) and extrinsic motivations (expectations for external outcomes).

We followed the phases of thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). Data constituted by our notes and the mind maps were translated from Spanish to English. Then, we (the authors) engaged into an iterative process. We analyzed selected random samples of the data set, defined codes describing elements of environmental stewardship as “suggested” by the youth and as “identified” by the researchers, and organized those codes into themes based on consensus (and guided by Bennett et al. (Citation2018)). Finally, we run a descriptive analysis on frequency distributions for the more common expressions of environmental stewardship, and elements representing levers or barriers. Thus, we counted how many times a particular expression of environmental stewardship was detected, and how many times a particular element was detected acting as a lever or barrier.

Results

The first research question explores in what ways participants’ environmental stewardship is manifested, while the second explores the elements affecting environmental stewardship and its expression. The mind map suggested nine environmental stewardship actions (), organized from left to right from the action named by most participants (participating in reforestation) to the action named by the minority of participants (protecting waters). We define these environmental stewardship actions as actions which support, don’t harm or don’t disrupt the normal functioning of natural ecosystems (including its alive and non-alive components). These are the nine ‘suggested’ stewardship actions briefly explained:

Table 1. Actions and related assets and motivations as “suggested” by the participants (n = 25).

Participating in reforestation: engaging in planting native species for nonproductive purposes, with the goal of restoring local ecosystems

Creating ecological points: establishing concrete locations in the village where the garbage is handled, separated in adequate bins and recycled/reused (what can be recycled and reused).

Reducing deforestation: decreasing logging of local forests.

Not polluting: not tossing garbage (especially plastics) away, not contaminating waters.

Not burning: not creating fires in the forest to create clear land for agricultural purposes.

Not hunting: not killing wild animals.

Protecting biodiversity: any action that can increase the chances of survival of wildlife in general.

Protecting reserves and sacred sites: not damaging private reserves dedicated to conservation or sacred locations for the Indigenous people.

Protecting waters: not engaging in actions that can pollute, disrupt or jeopardize rivers, mangroves, lakes and other masses of water.

The number of times each action was “suggested” appears below the action itself. The mind map also provided the reasons (capacities and motivations, which are listed in the first three columns) why they have ever participated or not in their “suggested” actions. Then, we assigned a plus (+) or a minus (−) to each capacity or motivation depending on if it was a lever or a barrier for engaging in a concrete “suggested” action. Capacities acted as levers when they were present, and as barriers when absent. For instance, the most “suggested” action, participating in reforestation, has a plus and a minus for the capacity environmental literacy because this acted both as a lever (+) and as a barrier (−), depending on if it was present or absent. Jose and Cristina, two participants, illustrated this clearly. On one hand, when asked why he reforests, Jose, answered: “Because my grandpa taught me how to do it.” Here, the presence of family habit and values and environmental literacy acted as levers. On the other hand, when we asked Cristina why she never reforested, she answered: “Because I don’t know how to do it.” Then the lack of environmental literacy acted as barrier.

For the motivations, in most cases an asset was working as a lever (+) when present. For instance, sense of place motivated some participants to protect biodiversity. Antonio, a participant, when asked about why he doesn’t cut trees in his coffee farm, said: “Because they belong to the land, same as me.” The only case where a motivation asset is present and works as a barrier is with the extrinsic motivation basic needs. When basic needs is present, it is acting as a barrier for the participants to act stewardly. Manuel, a participant, illustrated this when we asked him why he and his family shoot birds sometimes: “Because when we are working picking coffee for the whole day, we are very hungry, so if a bird perches close by, we shoot it.

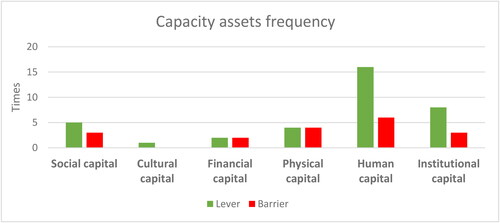

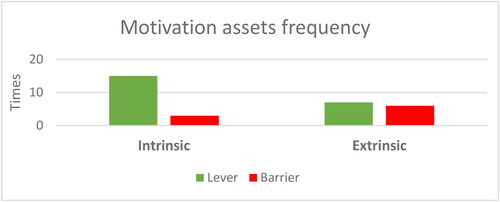

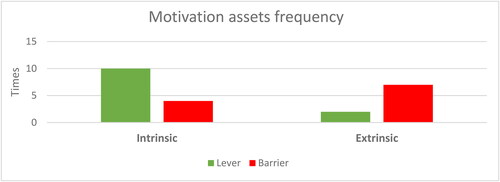

The graphics ( and ) show the number of time that the different capacities or motivations were mentioned in the mind maps acting as a lever or as a barrier on the participants “suggested” environmental stewardship actions. For instance, in we can see that, according to the participants, the financial capital acted always as a barrier due to the lack of resources for them to be able to engage in their “suggested” environmental stewardship actions. Andrés, made it very clear when we asked him why he never participated in any reforestation activities: “Because no one pays for it and I need to make money for my family.”

Figure 1. Number of times that each category of capacity assets was “suggested” as a lever or as a barrier (n = 25).

Figure 2. Number of times that each category of motivation assets was “suggested” as a lever or as a barrier (n = 25).

The same applies to institutional capital, where the lack of governmental support represents the biggest barrier mentioned by the participants. Meanwhile, human capital, especially environmental literacy was the most mentioned lever when present, and a barrier when absent. Social capital was mentioned both as lever and as a barrier, because family influence can be a strong force behind acting or not as a steward. In , the presence of intrinsic motivations as sense of place, nature connection and ethics acted as levers while extrinsic motivations as lack of economic incentives and existence of basic needs were barriers.

shows the results of the participant observations, photovoice and informal conversations. Here we briefly explain the ten environmental stewardship actions that we researchers “identified” on the participants:

Table 2. Actions and related assets and motivations as “identified” by the researchers.

Sharing nature knowledge: engaging in spreading knowledge related with local ecosystems or biodiversity, their importance and the need for their conservation.

Learning and researching about nature: actively investing time in knowing more about local ecosystems and biodiversity, their importance and how to protect them.

Choosing to live in a rural area: deciding to create and maintain their livelihood within a rural community.

Engaging in entrepreneurship: creating a business or developing a new economic activity within their community.

Developing organic coffee farming: working the land to develop a coffee plantation that grows in a balanced, not harmful way with the rest of the local ecosystem (no chemicals, no fires, keeping local vegetation to provide shade, food and shelter both for coffee and other wildlife).

Participating in wildlife monitoring: engaging in projects or activities aimed at monitoring and/or protecting populations of native, endemic and endangered species.

Documenting wildlife: engaging in recording, taking pictures, drawing or any other action that demonstrate the existence of wildlife.

Participating in reforestation: engaging in planting native species for nonproductive purposes, with the goal of restoring local ecosystems

Creating ecological points: establishing concrete locations in the village where the garbage is handled, separated in adequate bins and recycled/reused (what can be recycled and reused).

Not hunting: not killing wild animals.

While the “suggested” actions () were proposed by the participants as ideal environmental stewardship actions, the “identified” actions () were recognized by us (the researchers) as actions that the participants regularly engaged in. Those “identified” actions are organized from left to right from the action “identified” most to the action “identified” least. The number of times each action was “identified” appears below the action itself. Also, based on participant observations and informal conversations, we outlined elements (capacities and motivations) that enabled or disabled participants to engage in the ten “identified” actions. Then, we assigned a plus (+) or a minus (−) to each capacity or motivation depending on if it was a lever or a barrier. In some cases, an element acted both as a lever and a barrier (e.g., family influence over hunting or not hunting wildlife), while in other cases, it is the absence of an element that acts as a barrier, as illustrated in the following case. “We invited several participants to come at night to monitor frogs, and Manuel, a very enthusiast participant, didn’t raise his hand. After a while I asked him why he was not going to come, and he answered that his father won’t let him to.” In this case, lack of family support impeded one participant to participate in wildlife monitoring, but the presence of family support allowed the rest to be a part of the activity.

Of the nine environmental stewardship actions “suggested” by the participants () only three of them were “identified” by us researchers (). Those three actions, namely participating in reforestation, creating ecological points, not hunting wildlife, were among the most popular actions “suggested” by the participants (see ) but where the least common actions “identified” by the researchers (see ). We could not identify any of the remainder actions “suggested” by the participants. Furthermore, none of the first seven actions “identified” by us were “suggested” by the participants through the mind mapping.

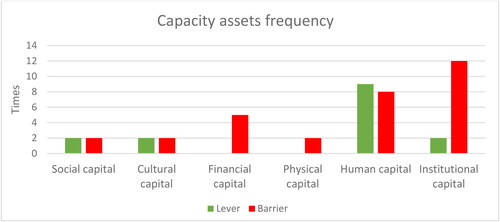

The graphics below ( and ) show the number of times each capacity or motivation asset was “identified” as a lever or as a barrier for participants to engage in the “identified” environmental stewardship actions. We can observe that human capital acted both as the most frequent lever and barrier, depending upon its presence or lack thereof. Contrary to the results shown in , the institutional capital acted mostly as a lever for environmental stewardship, mostly pushed by NGOs support. For instance, a participant told us about his family not using chemical fertilizers in their coffee farm “Because the coffee association gives us money to keep our farm organic so our coffee can be sold as organic and bio.” Regarding motivations, the extrinsic ones mainly correspond to economic benefits, which acted as a lever when taking care of nature brought a reward, and as a barrier when it did not. On the other hand, the presence of many intrinsic motivations as cultural beliefs, sense of place and nature connection acted as levers. Particularly nature connection was present as a lever in most of the “identified” stewardship actions. A clear example of this happened when we were discussing how to create a garden for colibris around the school, and Andrea, a Kogi student, mentioned a plant that she always sees full of colibris: “I know my flowers, they live around my house, I have seen them all my life.” These results show how all the “identified” stewardship actions had at least one motivation asset linked to them.

Discussion

Based on the study results just elucidated, at least three main findings emerge which are discussed in this section. Those findings can inform the understanding of youth environmental stewardship and implications for educational endeavors in the context of la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta and similar highly biodiverse, low-income regions.

Differences between participants’ understanding of environmental stewardship vs. researchers’ perspective on the participants’ environmental stewardship

We found a significant difference between the conceptions about environmental stewardship that the participants have () versus our interpretation of what environmental stewardship looks like in their daily lives (). On the one hand, through participant observations, informal conversations and photovoice, we have “identified” several environmental stewardship actions of the participants, such as: sharing knowledge about nature, learning and researching about nature, choosing to live in a rural area, engaging in entrepreneurship, developing organic coffee farming, participating in wildlife monitoring and documenting wildlife. None of these actions were “suggested” as environmental stewardship actions by the participants themselves when, during the mind maps, we asked them about actions which ideally would be the best ones to take care of their natural environment. We considered these “identified” environmental stewardship actions as expressions of the participants’ actual capacities and motivations dictated by their socio-economic context, and as an important steppingstone to draw a baseline on where educational programs can start building upon to strengthen the local youth’s environmental stewardship.

In order to protect something, you need to both know about it and feel or care for it. Knowing and caring are intricately connected (Kollmuss & Agyeman, Citation2002). For any people to develop environmental knowledge and affection for their territory, there is the need to inhabit the place. To wander in it, to sense it, to see the subtle connections of its elements and to learn how to create a livelihood from it, a fundamental aspect that standard education has completely neglected (Gruenewald, Citation2003). Throughout our observations, we came to see that most of our participants (especially non-Indigenous participants), didn’t know anything about the high number of endemic, endangered species that inhabit their territory. How are you going to take care of living beings that you don’t even know that they exist, but that at the same time they are all around you? This is why we considered as environmentally steward actions as sharing knowledge about nature and learning and researching about nature. The important question that arises then is the how. There is a huge difference between being given knowledge (sitting in a class while the teacher is just lecturing) and actively discovering and experiencing the creation of new knowledge by taking the classroom into the real world while simply walking around (and discovering that in the creek that passes by your school there is a plant growing that attracts an unique, endangered species of hummingbird that in the local culture symbolizes the wisdom of a shaman and that people from other countries come and pay to see it). And this is where a critical pedagogy of place needs to substitute the scientific imperialism that pervades Western culture and education characterized by creating isolated bubbles of knowledge (Tsevreni, Citation2011). By developing education programs that bring active, experiential learning along with critical reflection we will allow the youth to see the connections that influence their realities in order to develop the agency to shape their lives. Therefore, it is key to decolonize environmental education by respectfully include Indigenous knowledge and pedagogies, since they sustainably inhabited the land for centuries before Western colonization (Sutherland & Swayze, Citation2012). Several options, as introducing cultural elements linked to nature, language, and even the Indigenous Elders involvement in sharing traditional teachings can expose students to a worldview that lives by the intrinsic value and interdependence of living creatures and spiritual entities. For example, the only students that suggested as environmental stewardship actions protecting reserves and sacred sites, and protecting waters were Indigenous students. For them, the water, the stones, the sand, and everything commonly considered non alive by Western way of thinking, was protected and treated as sacred. Also, the mention of protecting sacred sites is extremely meaningful since the Sierra Nevada is fully surrounded by what is called the Black Line, an imaginary line that surrounds the whole region and connects locations of extreme spiritual, social and ecological importance for the four Indigenous tribes of the Sierra (López Rozo, Citation2020). Especially in the Sierra Nevada, where there is coexistence between Indigenous and non-Indigenous, accepting and respectfully integrating this type of knowledge in all educative levels would be an idea worth it to be explored. Besides, most of the participants belong to families of coffee farmers, thus the organic conversion process becomes a very significant way to positively affect the territory, since the farmers stop using chemicals, mix the coffee plants with other native species that attract other wildlife and protect both the soil and water sources. Therefore, a program that provides the youth with access to the knowledge, technologies and funding (thus improving their capacities and motivations) to transform their coffee farms into organic ones, would not just preserve the local biodiversity and enhance the quality and price of their product, but it would also be facilitating and strengthening sharing knowledge about nature, learning and researching about nature, choosing to live in a rural area, engaging in entrepreneurship, developing organic coffee farming, protecting biodiversity and protecting waters.

On the other hand, during the mind mapping, the participants “suggested” nine (9) environmental stewardship actions ). Using the other three research methods, we identified the participants engaging in just three (3) of their own “suggested” actions: participating in reforestation, creating ecological points, and not hunting. Nevertheless, we couldn’t identify the participants engaging in the other six (6) of their own “suggested” actions. These are: reducing deforestation, not polluting, not burning, protecting biodiversity, protecting reserves and sacred sites, and protecting waters. What impedes them to engage in most of the stewardship actions that they consider appropriate? Being immersed in such a context provides fertile ground for environmental stewardship to unfold but the participants’ lived experience does not seem to align with their verbalized ideas about what environmental stewardship should be. One explanation for this is that the participants may be externally influenced about what can be done to take care of nature. TV, radio, Internet, friends and family, NGOs working in the area, all these actors can influence their comprehension about what environmental stewardship is. This can be an especially interesting issue for the Indigenous participants. Their worldview and their way to live with the surrounding nature may have probably been affected by centuries of colonialist processes, whose influence right now is significant with the arrival of accessible technology. We saw all the Indigenous participants owning a mobile phone and engaging with social media, and the impacts of this process on them and their culture are unknown yet. Also, the practices and attitudes of the dominant Western culture toward nature may be in a way also influencing Indigenous livelihoods (Waterworth et al., Citation2016). Another element could be that the participants provided socially desirable responses by telling us what they thought we wanted to hear, something common in this kind of research (Norenzayan & Schwarz, Citation1999). If this is the case, it still reveals some of their understanding of and affinity with environmental stewardship. But it could also be that the participants also face a lot of barriers that impede them to put in practice their understanding of environmental stewardship (Kollmuss & Agyeman, Citation2002).

Barriers for environmental stewardship

Thus, why can’t participants enact most of their “suggested” stewardship actions in their everyday lives? According to them, the lack of economic resources or incentives of environmental literacy and of institutional support are the main barriers that impede them in, for instance, participating in reforestation one of the most common practices for ecosystem restoration. These barriers were also reported in a similar context in Costa Rica (Powlen & Jones, Citation2019). These barriers mainly point toward a lack of support from local, regional and state entities as expressed by weak participatory governance, a lack of adequate planning and monitoring (Murcia et al., Citation2016), lack of coherent policy (Rocca & Zielinski, Citation2022) and lack of economic support as consequence of agricultural policies that are unfavorable to smallholder farmers (Hegger, Citation2020). Even in some cases when there were economic resources, the institutions failed to take the needs of the local communities in to consideration, reducing both actors’ stewardship capacity assets and their motivation (Humavindu & Stage, Citation2015). Another example is waste management. According to the participants, the lack of resources, technologies, initiative, government support, infrastructure, environmental literacy, sense of place, personal interest and incentives are keeping them from managing their waste in a responsible way. All of these elements point toward a relative state of abandonment of rural areas, a fact shared by farmers from all around Colombia (Muñoz-Rios et al., Citation2020; Revelo Rebolledo & García Villegas, Citation2018). Here we can observe how the different categories of stewardship assets influence each other. In this case, the extreme weakness of institutional capital negatively affects the other sets of stewardship assets, as infrastructure, knowledge and motivations. Regarding the illegal hunting of wildlife, the barriers include family and friends’ influence, lack of environmental literacy, motivated by basic needs and preference for the taste of wild game, and for those with low economic resources, hunting meets basic needs (Duffy et al., Citation2016).

Lack of environmental literacy and school support is another critical element. For instance, participants didn’t know about the local endemic and endangered species, so why would they stop hunting them? The lack of school support is directly related to the lack of environmental literacy because these rural communities don’t have other sources of environmental knowledge other than the local school and the community. The knowledge about local species is hardly or not implemented in the local schools’ curricula. This does not affect just the possibility for the youth to stop hunting wildlife, it also hampers the possibility of initiating community-led monitoring of endangered species, restoring degraded land, changing farming practices and developing local conservation plans. Again, weak institutional capital (school) jeopardizes the human capital (awareness, knowledge, skills) that people can develop to enable stewardship. The data suggests that weak governmental support, and lack of regulation and modeling (government itself does not act accordingly, why should I?), plus a lack of economic incentives (I can’t afford to be a steward) and of environmental literacy (I don’t know how to be a steward) are the major barriers in front of La Tagua’s youth to become the environmental stewards of their territories. The lack of competence of many Colombian government officials worsens the situation by supporting privileged elites that control wealth, feed the paramilitarism, ignore environmental abuses and keep the rural underserved (Fergusson & Fergusson, Citation2019; Muñoz-Rios et al., Citation2020).

So, how can these barriers be overcome from an educational lens? We think that a combination of the following two ideas can bring positive results: first, train the teachers, and second, formalize and integrate environmental education. The teachers in places like La Tagua are with the students throughout the whole year. Building upon the motivations and capacities of the teachers around environmental stewardship (Corpuz et al., Citation2022) can be a significant move. Teachers need to learn how to integrate environmental stewardship into the formal curricula, and bring them into the reality of the community to address challenges (Wolff & Skarstein, Citation2020). The second idea is one that can help the integration of environmental stewardship within the curricula. In Colombia there is a formal figure called PRAE (Environmental School Programs), which incentivizes schools to include environmental issues within the curricula, from a practical perspective using school and community spaces. According to the Colombian National Ministry of Education, the PRAE are pedagogic projects that prompt the analysis and comprehension of local, regional and national environmental problems, as well as generate participatory spaces to implement solutions accordingly with natural and sociocultural dynamics (Ministerio de Educación Nacional de Colombia, Citation2023). There are a few successful PRAE examples around Colombia (Henao Hueso et al., Citation2019) that can serve as inspiration and motivation to enable environmental stewardship actions. Nevertheless, the National Policy of Environmental Education in Colombia reflects the interests of neoliberal policy agendas that look to consolidate their power positions by disregarding constructive, critical viewpoints from the environmental education researcher community discourses about how to deal with environmental issues through education (Mejía-Cáceres et al., Citation2021). This poses the question of until which point the formal education tools that are provided by the state can be used as a tool for empowering the youth in a reflective, critical and transformative environmental stewardship that questions and challenges the root of the socioecological problems that affect today’s society.

Levers for environmental stewardship

Both participants and we researchers identified levers toward environmental stewardship actions, such as environmental literacy, experience, NGO support, sense of place, nature connection and economic incentives. Environmental literacy and experience play a key role since nobody can be a steward if they don’t know how to behave as one. Different conservation approaches, as community-based monitoring, ecological restoration or citizen science require the cooperation of local, non-experienced participants under professional guidance, benefitting nature and community while building local capacity. This is a good space for the school to bring learning into the real world and enforcing positive socioecological impacts while challenging dominant practices in conventional education (Gruenewald, Citation2003). Regarding sense of place and nature connection, it seems fundamental that the school facilitates place attachment (Kudryavtsev et al., Citation2012) and place meanings (Masterson et al., Citation2017). Especially in multicultural places like the Sierra Nevada where Indigenous communities still thrive, sense of place needs to be linked to any expression of environmental stewardship to strengthen the latter. For the Indigenous cultures of the Sierra Nevada (Rodríguez-Navarro, Citation2000), nature is related to their spirituality. This bond is forged in reciprocity with the surrounding species, acknowledging wholeness (Muller et al., Citation2019). Nature integration within the social, physical, emotional and spiritual realms significantly enhances Indigenous nature’s stewardship compared with Western environmental management (Kealiikanakaoleohaililani & Giardina, Citation2016), thus knowledge and practice exchange with the Indigenous communities looks very much needed. It is the duty of the school to integrate the Indigenous knowledge into the curriculum so students can re-connect with their land (Canadian Commission for UNESCO, Citation2021). Nevertheless, as this is a daunting challenge and the Colombian State cannot meet the needs of its rural inhabitants (Jurado & Tobasura, Citation2012), there is the need for external alliances to move forward. As our data suggest, NGOs can facilitate youth engagement in environmental stewardship actions such as learning about nature, monitoring wildlife, developing organic coffee farming and engaging in entrepreneurship. Collaborations between schools and NGOs dedicated to conservation and related fields may improve the environmental stewardship capacities and motivations of the local youth (Pérez et al., Citation2019). Lastly, economic benefits are fundamental to motivate people to become stewards. We have seen that small economic incentives, as daily payments for monitoring birds and frogs, encourage youth to engage in stewardship actions (Şekercioğlu, Citation2012). Consequently, professional opportunities appear: a few participants became birdwatching guides, research assistants or started own ecotourism businesses. The ongoing conflict resolution in Colombia brings an opportunity for economic development of rural, impoverished communities, and a conservation threat of deforestation in newly accessible rural areas. Here, ecotourism is considered a “win–win” solution for developing countries to meet both economic and conservation needs. Considering Colombia as a megadiverse country, there is has a unique opportunity to build youth capacity around biodiversity-conservation related skills to develop a profitable and respectful nature tourism sector around birdwatching, herping or nature photography (Ocampo-Peñuela & Winton, Citation2017). This can be done at small scale through non-formal eco-clubs fostered by small, local NGOs. Also, considering the importance of coffee farming in the area, financial incentives linked to the completion of conservation education programs aimed to provide the human, technological and financial capital needed to cultivate profitable, yet biodiverse, organic coffee production systems could motivate the rural youth to become knowledgeable environmental stewards while developing fruitful livelihoods (Iverson et al., Citation2019) supported by the consumers’ willingness to pay for sustainable coffee (Gatti et al., Citation2022) recognized through certification programs as Bird Friendly coffee (Williams et al., Citation2021). As the state appears indolent while the Colombian forests get wrecked (Clerici et al., Citation2020) and youth struggles to create decent livings in rural areas, (Jurado & Tobasura, Citation2012) the support of alternative organizations appears fundamental to build youth capacity for environmental stewardship to achieve nature positive communities.

Conclusion

In this article, our aim was to share how the youth from a high-biodiverse region in Colombia may perceive and enact environmental stewardship, and which are the elements that impede or enable their stewardship. By means of a qualitative methodology, accompanied by a descriptive analysis, we mapped expressions of environmental stewardship and related levers and barriers, according to the perspective of the youth and the perspective of the researchers. This study provides evidence that a disruption in the current educative trends is needed to facilitate the youth to develop environmental stewardship. This educative transformation requires a dialogue of ways of knowing among several institutions and social actors, and particularly more political willingness and economic support from the State, but given its current lack of action in this regard, the role of NGOs in building youth capacity for nature conservation is paramount. The importance of the teachers cannot be overstated; therefore, they have to be trained and supported in new ways of knowing and acting. Besides, the integration of all aspects of nature learning (for instance, food sovereignty, water security, biodiversity conservation, ecological restoration, regenerative agriculture) under a pedagogy of place that is aware of the importance of emotions need to be integrated within the formal curricula using current available mechanisms, in order to foster capacities and motivations for the development of environmental stewardship. Of special significance is the inclusiveness of local, Indigenous knowledge, worldviews and practices to provide a solid baseline for a respectful relationship with the territory.

Finally, it is important to consider that the present research was focused on a few teenagers of one community, using mainly qualitative methods. A bigger sample size of students and regions would allow for better identification of key capacities and motivations that can be used as levers toward youth becoming stewards of their land. Further research is needed to understand how to finance and implement long-term, place-based, action-oriented, environmental education programs that empower the youth of high-biodiverse regions to become better stewards of their land.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Cecilia Rincón for all the support to work in her school and for giving us the freedom to work with the students in various ways. Thank you to Daniel Cárdenas for being a part of this research in his own way. A special thank you for the funding of this project to the National Geographic Society and the Rufford Foundation. Lastly, thank you to the teachers and students of the La Tagua school, for making learning and researching so enjoyable.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andrejewski, R., Mowen, A., & Kerstetter, D. (2011). An examination of children’s outdoor time, nature connection, and environmental stewardship. National Environment and Recreation Research Symposium. Available Online. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/nerr/2011/Papers/2

- Barnosky, A. D., & Hadly, E. A. (2016). Tipping point for planet earth: How close are we to the edge? Thomas Dunne Books.

- Bennett, N., Whitty, T. S., Finkbeiner, E., Pittman, J., Bassett, H., Gelcich, S., & Allison, E. H. (2018). Environmental stewardship: A conceptual review and analytical framework. Environmental Management, 61(4), 597–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-017-0993-2

- Berkes, F. (2012). Sacred ecology (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203123843

- Bignall, S., Hemming, S., & Rigney, D. (2016). Three ecosophies for the anthropocene: environmental governance, continental posthumanism and indigenous expressivism. Deleuze Studies, 10(4), 455–478. https://doi.org/10.3366/dls.2016.0239

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brosius, J. P., & Russell, D. (2003). Conservation from above imposing transboundary conservation. Journal of Sustainable Forestry, 17(1–2), 39–65. https://doi.org/10.1300/J091v17n01_04

- Burgess-Allen, J., & Owen-Smith, V. (2010). Using mind mapping techniques for rapid qualitative data analysis in public participation processes. Health Expectations : An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 13(4), 406–415. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00594.x

- Canadian Commission for UNESCO (2021). Land as teacher: Understanding Indigenous land-based education. Canadian Commission for UNESCO. https://en.ccunesco.ca/idealab/indigenous-land-based-education

- Clerici, N., Armenteras, D., Kareiva, P., Botero, R., Ramírez-Delgado, J. P., Forero-Medina, G., Ochoa, J., Pedraza, C., Schneider, L., Lora, C., Gómez, C., Linares, M., Hirashiki, C., & Biggs, D. (2020). Deforestation in Colombian protected areas increased during post-conflict periods. Scientific Reports, 10(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61861-y

- Cockburn, J., Cundill, G., Shackleton, S., & Rouget, M. (2019). Meaning and practice of stewardship in South Africa. South African Journal of Science, 115(5/6), 5339. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2019/5339

- Corpuz, A. M., San Andres, T. C., & Lagasca, J. M. (2022). Integration of environmental education (EE) in teacher education programs: toward sustainable curriculum greening. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 80(1), 119–143. https://doi.org/10.33225/pec/22.80.119

- Duffy, R., St John, F. A. V., Büscher, B., & Brockington, D. (2016). Toward a new understanding of the links between poverty and illegal wildlife hunting. Conservation Biology : The Journal of the Society for Conservation Biology, 30(1), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12622

- Enqvist, J., West, S., Masterson, V., Haider, L., Svedin, U., & Tengö, M. (2018). Stewardship as a boundary object for sustainability research: Linking care, knowledge and agency. Landscape and Urban Planning, 179, 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.07.005

- Fergusson, L., & Fergusson, L. (2019). Who wants violence? The political economy of conflict and state building in Colombia. Cuadernos de Economía, 38(78), 671–700. https://doi.org/10.15446/cuad.econ.v38n78.71224

- Forsey, M. G. (2010). Ethnography as participant listening. Ethnography, 11(4), 558–572.

- García, L. C. (2011). El accionar político militar del paramilitarismo en la región de la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta y su incidencia sobre la situación de los derechos humanos de las poblaciones indígenas entre los años 2002 y 2007 (p. 78). Universidad Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario, Facultad de ciencia Política y Gobierno.

- Gatti, N., Gomez, M. I., Bennett, R. E., Scott Sillett, T., & Bowe, J. (2022). Eco-labels matter: Coffee consumers value agrochemical-free attributes over biodiversity conservation. Food Quality and Preference, 98, 104509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2021.104509

- Gruenewald, D. A. (2003). The best of both worlds: A critical pedagogy of place. Educational Researcher, 32(4), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032004003

- Hegger, K. (2020). How to sow peace?: A value chain approach for environmental peacebuilding in Sierra de la Macarena National Park, Colombia. In Master Thesis Series in Environmental Studies and Sustainability Science, No 2020:051 (p. 73). LUCSUS.

- Henao Hueso, O., Sánchez Arce, L., Henao Hueso, O., & Sánchez Arce, L. (2019). La educación ambiental en Colombia, utopía o realidad. Conrado, 15(67), 213–219.

- Hoover, K. S. (2021). Children in nature: Exploring the relationship between childhood outdoor experience and environmental stewardship. Environmental Education Research, 27(6), 894–910. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1856790

- Huertas Díaz, O., Esmeral Ariza, S. J., & Sánchez Fontalvo, I. M. (2017). Realidades sociales, ambientales y culturales de las comunidades indígenas en La Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. Producción + Limpia, 12(1), 10–23. https://doi.org/10.22507/pml.v12n1a1

- Humavindu, M. N., & Stage, J. (2015). Community-based wildlife management failing to link conservation and financial viability. Animal Conservation, 18(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/acv.12134

- Iverson, A. L., Gonthier, D. J., Pak, D., Ennis, K. K., Burnham, R. J., Perfecto, I., Ramos Rodriguez, M., & Vandermeer, J. H. (2019). A multifunctional approach for achieving simultaneous biodiversity conservation and farmer livelihood in coffee agroecosystems. Biological Conservation, 238, 108179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.07.024

- Jurado, C., & Tobasura, I. (2012). Dilema de la juventud en territorios rurales de Colombia: ¿campo o ciudad? Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 10(1), Article 1. http://revistaumanizales.cinde.org.co/rlcsnj/index.php/Revista-Latinoamericana/article/view/581

- Kealiikanakaoleohaililani, K., & Giardina, C. P. (2016). Embracing the sacred: An indigenous framework for tomorrow’s sustainability science. Sustainability Science, 11(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-015-0343-3

- Kollmuss, A., & Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 239–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620220145401

- Kopnina, H. (2020). Education for the future? Critical evaluation of education for sustainable development goals. The Journal of Environmental Education, 51(4), 280–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2019.1710444

- Kudryavtsev, A., Krasny, M. E., & Stedman, R. C. (2012). The impact of environmental education on sense of place among urban youth. Ecosphere, 3(4), art29. https://doi.org/10.1890/ES11-00318.1

- Le Saout, S., Hoffmann, M., Shi, Y., Hughes, A., Bernard, C., Brooks, T. M., Bertzky, B., Butchart, S. H. M., Stuart, S. N., Badman, T., & Rodrigues, A. S. L. (2013). Protected areas and effective biodiversity conservation. Science (New York, N.Y.), 342(6160), 803–805. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1239268

- Lett, J. (1990). Emics and etics: Notes on the epistemology of anthropology. In Thomas N. Headland, Kenneth L. Pike, & Marvin Harris (Eds.), Emics and etics: The insider/outsider debate (pp. 127–142). Sage.

- López Rozo, L. A. (2020). The “Black Line” (“La línea negra”) as acknowledgement of the ancestral territories of the Indigenous communities of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. IUSTA, 53, 45–67. https://repository.usta.edu.co/handle/11634/32630

- Louv, R. (2005). Last child in the woods: Saving our children from nature-deficit disorder. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. http://richardlouv.com/books/last-child/

- Masterson, V., Stedman, R., Enqvist, J., Tengö, M., Giusti, M., Svedin, U., & Wahl, D. (2017). The contribution of sense of place to social-ecological systems research: A review and research agenda. Ecology and Society, 22(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08872-220149

- Mathevet, R., Bousquet, F., & Raymond, C. M. (2018). The concept of stewardship in sustainability science and conservation biology. Biological Conservation, 217, 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.10.015

- McGrath, C., & Laliberte Rudman, D. (2019). Using participant observation to enable critical understandings of disability in later life: An illustration conducted with older adults with low vision. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 160940691989129. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919891292

- Mejía-Cáceres, M. A., Huérfano, A., Reid, A., & Freire, L. M. (2021). Colombia’s national policy of environmental education: A critical discourse analysis. Environmental Education Research, 27(4), 571–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1800594

- Ministerio de Educación Nacional de Colombia (2023). https://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/article-90893.html

- Moore, J. W. (2015). Capitalism in the web of life: Ecology and the accumulation of capital. Verso Books.

- Muller, S., Hemming, S., & Rigney, D. (2019). Indigenous sovereignties: Relational ontologies and environmental management. Geographical Research, 57(4), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12362

- Muñoz-Rios, L. A., Vargas-Villegas, J., & Suarez, A. (2020). Local perceptions about rural abandonment drivers in the Colombian coffee region: Insights from the city of Manizales. Land Use Policy, 91, 104361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104361

- Murcia, C., Guariguata, M. R., Andrade, Á., Andrade, G. I., Aronson, J., Escobar, E. M., Etter, A., Moreno, F. H., Ramírez, W., & Montes, E. (2016). Challenges and prospects for scaling-up ecological restoration to meet international commitments: Colombia as a case study. Conservation Letters, 9(3), 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12199

- Norenzayan, A., & Schwarz, N. (1999). Telling what they want to know: Participants tailor causal attributions to researchers’ interests. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29(8), 1011–1020. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199912)29:8 < 1011::AID-EJSP974 > 3.0.CO;2-A

- Ocampo-Peñuela, N., & Winton, R. S. (2017). Economic and conservation potential of bird-watching tourism in postconflict Colombia. Tropical Conservation Science, 10, 194008291773386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940082917733862

- OECD. (2019). PISA results from PISA 2018 Colombia. Country note. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/PISA2018_CN_COL_ESP.pdf

- Omoogun, A. C., Egbonyi, E. E., & Onnoghen, U. N. (2016). From environmental awareness to environmental responsibility: Towards a stewardship curriculum. Journal of Educational Issues, 2(2), 60–72. https://doi.org/10.5296/jei.v2i2.9265

- Papworth, S. k., Rist, J., Coad, L., & Milner-Gulland, E. j (2009). Evidence for shifting baseline syndrome in conservation. Conservation Letters, 2(2), 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2009.00049.x

- Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia (2021). Parque Nacional Natural Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. https://www.parquesnacionales.gov.co/portal/es/ecoturismo/region-caribe/parque-nacional-natural-sierra-nevada-de-santa-marta-2/

- Pérez, D. R., González, F., del, M., Araujo, M. E. R., Paredes, D. A., & Meinardi, E. (2019). Restoration of society-nature relationship based on education: A model and progress in Patagonian drylands. Ecological Restoration, 37(3), 182–191. https://doi.org/10.3368/er.37.3.182

- Pitard, J. (2017). A journey to the centre of self: Positioning the researcher in autoethnography. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.3.2764

- Pitt, A. N., Schultz, C. A., & Vaske, J. J. (2019). Engaging youth in public lands monitoring: Opportunities for enhancing ecological literacy and environmental stewardship. Environmental Education Research, 25(9), 1386–1399. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1649368

- Powlen, K. A., & Jones, K. W. (2019). Identifying the determinants of and barriers to landowner participation in reforestation in Costa Rica. Land Use Policy, 84, 216–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.02.021

- Revelo Rebolledo, J. E., & García Villegas, M. (Eds.). (2018). El estado en la periferia: Historias locales de debilidad institucional [Primera edición]. Dejusticia.

- Rocca, L. H. D., & Zielinski, S. (2022). Community-based tourism, social capital, and governance of post-conflict rural tourism destinations: The case of Minca, Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. Tourism Management Perspectives, 43, 100985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2022.100985

- Rodríguez-Navarro, G. E. (2000). Indigenous knowledge as an innovative contribution to the sustainable development of the Sierra Nevada of Santa Marta, Colombia. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 29(7), 455–458. https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447-29.7.455

- Salmon, E. (2000). Kincentric ecology: Indigenous perceptions of the human nature relationship. Ecological Applications, 10(5), 1327–1332. https://doi.org/10.2307/2641288

- Santos, Á. O. (2006). Asentamientos humanos y caracterización de la diversidad cultural en la sierra nevada de santa marta. Jangwa Pana, 5(1), 132–149. https://doi.org/10.21676/16574923.456

- Şekercioğlu, Ç. H. (2012). Promoting community-based bird monitoring in the tropics: Conservation, research, environmental education, capacity-building, and local incomes. Biological Conservation, 151(1), 69–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2011.10.024

- Shivanna, K. R. (2020). The sixth mass extinction crisis and its impact on biodiversity and human welfare. Resonance, 25(1), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12045-019-0924-z

- Soga, M., & Gaston, K. J. (2018). Shifting baseline syndrome: Causes, consequences, and implications. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 16(4), 222–230. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1794

- Stern, M. J., Powell, R. B., & Ardoin, N. M. (2008). What difference does it make? Assessing outcomes from participation in a residential environmental education program. The Journal of Environmental Education, 39(4), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEE.39.4.31-43

- Sutherland, D., & Swayze, N. (2012). Including indigenous knowledges and pedagogies in science-based environmental education programs. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education (CJEE), 17, 80–96.

- Swain, J. M., & Spire, Z. D. (2020). The role of informal conversations in generating data, and the ethical and methodological issues. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 21(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.1.3344

- Tsevreni, I. (2011). Towards an environmental education without scientific knowledge: An attempt to create an action model based on children’s experiences, emotions and perceptions about their environment. Environmental Education Research, 17(1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504621003637029

- Unidad Administrativa Especial del Sistema de Parques Nacionales Naturales (UAESPNN) (2005). PARQUE NACIONAL NATURAL SIERRA NEVADA DE SANTA MARTA (p. 170). UAESPNN.

- Wals, A. (1993). Critical phenomenology and environment education research. In R. Mrazek (Ed.), Alternative paradigms in environmental education research (pp. 153–175). NAAEE (North American Association for Environmental Education).

- Waterworth, P., Dimmock, J., Pescud, M., Braham, R., & Rosenberg, M. (2016). Factors affecting Indigenous West Australians’ health behavior: Indigenous perspectives. Qualitative Health Research, 26(1), 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315580301

- Williams, A., Dayer, A. A., Hernandez-Aguilera, J. N., Phillips, T. B., Faulkner-Grant, H., Gómez, M. I., & Rodewald, A. D. (2021). Tapping birdwatchers to promote bird-friendly coffee consumption and conserve birds. People and Nature, 3(2), 312–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10191

- Wolff, L.-A., & Skarstein, T. H. (2020). Species learning and biodiversity in early childhood teacher education. Sustainability, 12(9), 3698. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093698

- Worrell, R., & Appleby, M. C. (2000). Stewardship of natural resources: Definition, ethical and practical aspects. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 12(3), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009534214698