Abstract

To promote pro-environmental behavior (PEB), it is crucial to understand the drivers behind it. Studies indicate that, in addition to environmental attitudes and nature activities, interest in nature drives people to engage in PEB. However, the relationship between interest in nature and PEB is still greatly understudied among adolescents even though the foundations for PEB seem to be laid during childhood. Therefore, our study focuses specifically on the link between adolescents’ interest in nature, their nature activities, and PEB. We collected self-reported cross-sectional data from 954 German school students using the Scale of Interest in Nature (SIN) and the General Ecological Behavior Scale (GEB). Findings indicate a decline in interest in nature, PEB, and nature activities from grade 5 to 9, while also revealing a significant positive correlation between all these constructs. Results highlight the importance of fostering interest in nature in environmental education programs and suggest including it in further research.

Introduction

For several decades, humanity has exceeded the planet’s ecological limits (Steffen et al., Citation2015). The consequences are severe on a global scale, ranging from record-low sea ice levels in the Arctic and bush fires in Australia, to heat waves in Europe, and a massive decline of biodiversity on all continents (Eichenberg et al., Citation2021; Goldrick, Citation2019; IPCC, Citation2021). Both the IPBES (Citation2019) and IPCC reports (Citation2021) confirm that human behavior and decisions are the main cause of these global effects. In order to overcome or at least mitigate these crises and achieve a more sustainable future, the United Nations (Citation2015) presented a global action plan, the “Agenda 2030”, encompassing 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Researchers worldwide highlight education as one of the cornerstones in the effort to achieve these goals (Möller et al., Citation2021; Otto et al., Citation2020; Reimers, Citation2021; Winter et al., Citation2022). Especially, Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) responds to these challenges by fostering a lifelong learning process empowering individuals to make informed decisions and to take national and global actions (UNESCO, Citation2020). ESD is grounded in the belief that a sustainable future is only possible if people start engaging more in nature-protective and pro-environmental behaviors (Gifford & Nilsson, Citation2014; Liefländer et al., Citation2013; Otto et al., Citation2019; Otto & Kaiser, Citation2014; Richardson et al., Citation2020).

To promote pro-environmental behavior (PEB) and develop effective ESD programs, it is important to understand and determine key influencing factors of PEB (Richardson et al., Citation2020; Whitburn et al., Citation2020). While some influencing factors such as environmental attitudes, connection to nature and experiences in nature, have been examined in empirical studies (Bamberg & Möser, Citation2007; Gifford & Nilsson, Citation2014; Li et al., Citation2019; Roczen et al., Citation2014), the full extent of factors influencing PEB and the challenges in its development remain uncertain (Kollmuss & Agyeman, Citation2002). One recurring—yet not investigated to a great extent—factor we identified is interest in nature, which describes the specific relationship between a person and nature as an object of interest (Krapp, Citation2002; Neurohr et al., Citation2023). What distinguishes this concept is its incorporation of emotion and value related as well as intrinsic motivation. According to the theory of interest (Krapp, Citation2002), individuals are more likely to engage with objects of interest when they can personally identify with and integrate them into their sense of self (Blankenburg & Scheersoi, Citation2018; Krapp & Prenzel, Citation2011). Interest in nature could serve as an intrinsic motivator, potentially driving a person’s involvement in nature preservation without relying on external rewards or incentives (Schiefele et al., Citation1993), thus solidifying it as a robust individual trait and enhancing one’s commitment to preserving nature (Kals et al., Citation1999; Schiefele et al., Citation1993).

While interest in nature has been acknowledged as an influencing factor, especially among young people (Kals et al., Citation1999; Leske & Bögeholz, Citation2008), its conceptualization in prior research has been characterized by a diverse terminology. This diversity has led to the measurement of different concepts, as seen in the case of connection to nature, environmental perception, or love and care for nature (Salazar et al., Citation2020; Todd, Citation2021). The interchangeable use of the term’s connection to nature and interest in nature underscores the need for clarification in research to precisely define and measure these distinct yet related concepts. Consequently, the current research addresses a significant gap by aiming to disentangle the concept of interest in nature from other related ideas through a theoretical foundation. Moreover, our study places a particular emphasis on interest in nature and seeks to comprehensively explore its interactions with self-reported Pro-Environmental Behavior (PEB) within the critical demographic of adolescents. This approach aims to contribute valuable insights into the nuanced relationship between interest in nature and PEB, thereby filling a crucial gap in the existing literature and advancing our understanding of these interconnected constructs.

Theoretical background

Conceptualization of interest in nature

Krapp’s person-object theory (Citation2002) posits that interest involves an interactive connection between an individual and a specific object in their environment. This concept encompasses both cognitive and affective elements and is divided into two forms: situational interest and individual interest (Krapp, Citation2002). Situational interest refers to a temporary psychological state characterized by heightened attention, effort, and positive emotions experienced during a specific activity (Harackiewicz et al., Citation2016). It typically arises in response to external stimuli and may develop through repeated engagement with the object. Effective external triggers for situational interest include instructional conditions or specific learning environments, such as hands-on activities, group work, or physical activities related to the object of interest (Hidi et al., Citation1998; Holstermann et al., Citation2010; Randler & Bogner, Citation2007; Richardson et al., Citation2020). Individual interest is a dispositional motivational state, in which a person engages with an object of interest without external stimulation (Krapp & Prenzel, Citation2011). Sustained individual interest typically emerges following previous experiences of situational interest, reflecting a motivational state of engagement during an activity based on genuine interest (Hidi & Renninger, Citation2006). Individuals with a strong individual interest are primarily driven by personal initiative and demonstrate persistence in their actions, even in the face of failures or negative emotions (Renninger & Hidi, Citation2002). When individuals can identify with an object of interest and integrate it into their self-concept, they are more likely to engage with it (Blankenburg & Scheersoi, Citation2018; Krapp & Prenzel, Citation2011). Given that interest influences the direction, intensity, and persistence of goal-oriented behaviors, it is reasonable to assume that an inclination to protect nature is associated with an increasing appreciation for and heightened interest in nature (Kaiser et al., Citation2013; Kals et al., Citation1999; Neurohr et al., Citation2023; Roczen et al., Citation2014).

Individual interest in an object consists of cognitive and affective components (Hidi et al., Citation2004). Schiefele et al. (Citation1993) underscore interest as primarily an affective variable, distinguishing three key components: emotion-related and value-related components and intrinsic orientation. The emotional component pertains to positive feelings such as joy, while the value-related component involves matters of personal significance. However, the defining characteristic of interest lies in its intrinsic nature (Krapp, Citation2007), indicating that interest is authentic when engagement with an object is primarily driven by internal motivations. This intrinsic component signifies engagement driven by internal motivations rather than external rewards or incentives (Schiefele et al., Citation1993). This study focuses on these three affective components of interest, as previous research indicates that cognitive variables, such as environmental knowledge, have minimal impact on environmental behavior (Knutti, Citation2019; Otto & Pensini, Citation2017; Steg & Vlek, Citation2009).

Our approach to measuring interest utilizes a psychometric methodology, grounded in established research in educational psychology and anchored in the person-object theory (Krapp, Citation2002). This theory focuses on building relationships between individuals and the object of interest (nature), emphasizing the cultivation of meaningful connections recognizing nature’s intrinsic value, rather than viewing it solely in terms of its usefulness to humans. In our study, “nature” encompasses the biophysical environment, including flora, fauna, and geological landscapes, and underscores its existence independently of human presence (Kals et al., Citation1999; Zylstra et al., Citation2014). Although our emphasis on emotion- and value-based factors, as well as intrinsic motivation, may predominantly reflect Western perspectives, we acknowledge the importance of incorporating diverse cultural perspectives. While our study does not explicitly incorporate a spiritual component, we recognize the potential for non-Western communities to embrace various emotional and value-based connections to nature, which may manifest in diverse forms (Verschuuren & Brown, Citation2018).

Distinguishing interest in nature from related constructs

Interest in nature and connection to nature are two closely related yet distinct concepts in research concerning human interaction with the natural environment. While these terms are sometimes used interchangeably, there is a need for clarification in research to precisely define and measure these concepts.

Interest in nature refers to an individual’s curiosity, attraction, or fascination with the natural world. It encompasses both emotional aspects, such as positive feelings like joy and pleasure, and value-related aspects reflecting personal meaningfulness derived from engaging with the features, processes, and phenomena in nature (Krapp, Citation2007). This concept typically revolves around an individual’s intrinsic motivation to explore the natural world (Neurohr et al., Citation2023; Schiefele et al., Citation1993). Engagement with an object can be attributed to interest only when it occurs intentionally, based on the qualities or characteristics of the object itself (Krapp & Prenzel, Citation2011; Schiefele et al., Citation1993).

In contrast, connection to nature represents a broader concept that encompasses an individual’s emotional, psychological, and experiential relationship with the natural environment. It reflects a person’s sense of belonging, identity, and interdependence with nature (Tam, Citation2013; Whitburn et al., Citation2020). This concept goes beyond mere interest and involves a deeper, more profound connection. It includes feelings of oneness with nature, a sense of stewardship, and an understanding of the interconnectedness between humans and the environment (see ).

Table 1. Comprehensive overview of instruments measuring connection to nature and the measured concepts.

Upon examining various scales measuring connection to nature (), it is evident that this concept embodies three interconnected dimensions of the humans-nature relationship: affect (feelings toward nature), cognition (knowledge and beliefs about nature), and behavior (actions and experiences in nature) (Whitburn et al., Citation2020). Some scales assess connection to nature as a single dimension, emphasizing either emotional attachment to nature (Davis et al., Citation2009; Kals et al., Citation1999; Mayer & Frantz, Citation2004; Perkins, Citation2010) or the integration of nature within one’s cognitive self-concept (Schultz, Citation2002). Conversely, other scales adopt a multidimensional approach, encompassing all three dimensions of this relationship (Beery & Wolf-Watz, Citation2014; Brügger et al., Citation2011; Clayton & Opotow, Citation2003; Dutcher et al., Citation2007; Nisbet et al., Citation2009; Tam, Citation2013). However, as shown in , connection to nature spans across affective, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions, illustrating its multifaceted nature. In contrast, interest in nature, as conceptualized here based on Schiefele et al. (Citation1993) general interest concept, revolves around the affective relationship between an individual and nature, fueled by intrinsic motivation. While connection to nature emphasizes a broader and deeper emotional bond, underscoring an individual’s relationship with and responsibility toward nature, interest in nature serves as a component within this connection, highlighting affective aspects and the intrinsic desire to be captivated by nature.

Underlying mechanism of interest in nature and pro-environmental behavior

Pro-environmental behavior (PEB) encompasses various actions aimed at reducing one’s environmental impact, such as energy and water conservation (Berardi, Citation2017; Kaiser & Wilson, Citation2004), waste management (Liu et al., Citation2017), and sustainable transportation choices (Eriksson et al., Citation2008). Adolescents often engage in PEB by conserving resources at home (electricity and water), using reusable packaging for school or sports activities (such as lunch boxes or water bottles), or participating in recycling initiatives (Kaiser & Wilson, Citation2004). Social norms and individual motives, including attitudes, problem awareness, and perceived behavioral control, emerge as crucial predictors of PEB (Bamberg & Möser, Citation2007; Kaiser & Wilson, Citation2004). Recent research underscores the significance of factors such as environmental attitudes, connection to nature, and experiences in nature in promoting PEB (Brügger et al., Citation2011; Chawla, Citation2020; Nisbet et al., Citation2009; Richardson et al., Citation2020; Roczen et al., Citation2014; Schultz, Citation2002; Torkar & Krašovec, Citation2019). Despite widespread concern for environmental issues, a gap persists between environmental attitudes and actual behavior due to barriers such as personal costs (e.g., time and financial constraints) and lack of structural support (e.g., lack of efficient public transportation options) (Kollmuss & Agyeman, Citation2002; Whitburn et al., Citation2020). Understanding these complexities is essential for developing effective programs and policies in ESD aimed at fostering sustainable behaviors. This study explores the relationship between young people’s interest in nature and their PEB, an aspect that has received limited investigation. An in-depth analysis of this construct could shed light on its role in shaping PEB. Through this research, we aim to advance the understanding of the multifaceted nature of PEB and contribute to the development of targeted interventions and policies to promote sustainable behaviors.

Even though influencing factors on interest in nature have not yet been studied in greater detail, one central factor is already emerging: time spent in nature (Chawla, Citation2020; Cheng & Monroe, Citation2012; Kals et al., Citation1999; Torkar & Krašovec, Citation2019). Studies show that spending time in nature can help to build up emotional bonds and interest in nature (Bezeljak et al., Citation2023; Neurohr et al., Citation2023). Hobbies in nature, such as hiking, picking flowers or fruits, planting trees, or caring for plants as well as being an active member of an environmental organization have a positive relationship with pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors (Arnold & Kaiser, Citation2016; Kals et al., Citation1999; Neurohr et al., Citation2023; Otto et al., Citation2021; Richardson et al., Citation2020; Tam, Citation2013; Wells & Lekies, Citation2006; Zylstra et al., Citation2014). However, most of these studies focus only on adults, whereas adolescents remain greatly understudied. This might be a significant gap, as research shows that most of the foundations for environmentally protective behavior are laid in childhood (for an overview, see Chawla, Citation2020). Adult conservation volunteers, for example, develop their interest in nature at a young age (Guiney, Citation2009). Studies reveal a concerning trend where children are spending a decreasing amount of time in nature and become increasingly alienated from it (Kellert et al., Citation2017; Larson et al., Citation2019; Louv, Citation2005; Soga & Gaston, Citation2016). Since children’s experiences in nature are declining, it is highly likely that their interest in nature is also falling (Chawla, Citation2020; Soga & Gaston, Citation2016). A cross-sectional study observed a downward trend in students’ interest in nature from upper secondary school (grades 9 and 10) to the end of high school (Leske & Bögeholz, Citation2008). As possible reasons, researchers identified not only a decline in nature experiences (Pyle, Citation1993; Soga & Gaston, Citation2016), but a growing level of digitalization as well (Kuss & Griffiths, Citation2017; Michaelson et al., Citation2020).

ESD programs could be an opportunity to offer children direct contact with nature through experiences in nature, and thus foster their interest in nature. To appropriately develop such programs, it is essential to know more about adolescents’ interest in nature and gain further insights into its role as a determinant of PEB: How is interest in nature demonstrated in different age groups? Which kind of nature experiences correlate with interest in nature? How does interest correlate with PEB? So far, there are only a few studies focusing on interest in nature, and to our knowledge, none focuses on preadolescents and adolescents or investigates possible correlations with PEB (Kals et al., Citation1999; Kleespies et al., Citation2021; Leske & Bögeholz, Citation2008). In our study, we therefore explicitly chose to focus on lower secondary school students (grades 5 to 9), using an age-appropriate scale to measure students’ self-reported interest in nature (Scale of interest in nature—“SIN”) and analyzing its relationship with PEB.

Research goals

With the here presented study we aim to address four objectives: (1) to observe the extent of interest in nature among a large sample of German lower secondary school students (grades 5–9), (2) to examine the relationship between interest in nature and PEB, (3) to analyze nature activities such as time spent outside, membership in an environmental organization or a hobby in nature among students in different lower secondary school grades, and (4) to identify which of these nature activities are associated with a strong interest in nature.

Our research questions are:

To what extent does students’ interest in nature vary across grades 5 to 9?

Is there a demonstrable positive correlation between students’ interest in nature and their engagement in pro-environmental behaviors (PEB)?

To what degree are lower secondary school students engaged in nature-related activities, including time spent outdoors, membership in environmental organizations, or participation in nature-oriented hobbies?

Which specific nature-related activities are associated with a strong interest in nature among students in lower secondary schools?

Methods

Participants and recruitment

Our study encompassed a convenience sample of 1092 students from North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, covering grades 5 to 9 (ages 10 to 15, Mage: 12.48, SD: 1.54; 54% female). The sample was evenly distributed across all five grades. All schools were public schools, supported financially by the government and providing free education. None of the participating schools had a focus on specific subjects, nor offered special education programs. Students were informed in advance about the aims of the research, duration, procedure, and anonymity of the data. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the data analysis. In accordance with the law in North Rhine-Westphalia, the study was approved by each head of school. This study did not involve clinical patients, was noninvasive, and participation was voluntarily and anonymous.

Procedures

Students completed an anonymous paper-and-pencil questionnaire during their regular class time. The questionnaire was administered by teachers from the respective classes, who volunteered to dedicate their lesson time (subject dependent on the teacher) to facilitate the study. In addition to the written instructions on the questionnaire, the teachers received standardized instructions for an oral introduction and explanations. It took the students between 30 and 40 min to complete the questionnaire. The students’ questionnaires were returned to the research team after successfully completing the questionnaires. The questionnaire included seven scales measuring different aspects of affective attitudes and awareness related to nature and the environment. These were either directly adopted from established literature or adapted for our own study. In this study, however, we focus exclusively on two of the scales since we aim to examine the role of interest in nature as determinant of PEB (see Supplemental Materials 1 and 2).

Measures

Interest in nature was measured by the Scale of interest in nature (SIN: Neurohr et al., Citation2023). The scale comprises 18 items, each consisting of a statement regarding the individuals’ interest in nature (e.g., "In my opinion, documentaries and movies on nature are interesting.”). The participants had to rate their agreement with each statement on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = strongly disagree, 1 = disagree, 2 = partially agree, 3 = agree, and 4 = strongly agree). To control for response style bias, the scale includes reversed items, which we recoded afterwards. The results of the analysis show that all items fit the model, and the Rasch-model-based item reliability of the measure was discovered to be 1.00 (N = 954).

Pro-environmental behavior was assessed based on the Campbell paradigm (Kaiser et al., Citation2010), which addresses the extent to which individuals generally embrace an environmentally friendly lifestyle, instead of focusing on specific behavioral domains. This approach recognizes that individuals perform a broad multitude of behaviors, which all have some environmental impact (Otto & Pensini, Citation2017). To capture an individual’s broader environmental impact, a broad assessment of ecological behaviors is necessary. Therefore, we used the behavior-based environmental attitude scale (GEB: Kaiser et al., Citation2007) as a comprehensively tested and validated self-report instrument. There is currently no other general performance measure that is similarly well developed, and specifically designed to be used with adolescents. Respecting the limited behavioral alternatives available to adolescents (Evans et al., Citation2007), we reduced the scale to the most suitable 18 behavioral items, while still addressing all 6 domains of the original scale: recycling, waste avoidance, consumerism, mobility and transportation, energy conservation, and vicarious conservation behaviors. The reduction of items was justified by two pilot studies in which we examined person reliability, item difficulty, normal distribution, and the basic model fit of the items. Example items are „I separate my trash “or „I take a tote bag or backpack with me when I go shopping”. We used a five-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always) for the behavioral self-report items. 3 of 18 items were reverse coded and described unecological behaviors. Item reliability was found to be rel. = 1.00 (N = 954).

Nature activities were assessed in terms of three different aspects: time spent in nature, pursuing a hobby in nature, and membership in an environmental protection organization (see Supplemental Materials 1 and 2). Students answered how many days per week (0–7) they spend time in nature on average. In line with Bezeljak et al. (Citation2023), for the analyses, we split the reported time spent in nature into two groups: those spending less time in nature (0–3 days) and those spending more time in nature (4–7 days). In addition, participants indicated if they have a hobby that involves spending a lot of time in nature, such as hiking, rock climbing, birdwatching, or gardening and if they are an active member of an environmental protection organization (e.g., Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth Germany (BUND), or the Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union (NABU)). Both items were answered in a dichotomous format („yes “or „no”). Furthermore, we collected demographic information such as grade, age, and gender.

In this study, we employ self-reported scales to measure both interest in nature (SIN) and pro-environmental behavior (PEB), despite their known limitations. Self-reported scales have faced criticism due to potential issues related to objectivity, such as discrepancies between reported and actual behavior (Gatersleben et al., Citation2002; Kormos & Gifford, Citation2014). Subjectivity biases, including social desirability bias, may also arise as participants might lack accurate insight into their motivations or experiences (Koller et al., Citation2023). Such concerns could impact the reliability and validity of collected data, relying on participants’ honesty and accuracy in reporting. However, despite these concerns, self-reported data offers practical advantages, especially in studies with large sample sizes like ours, which includes over 1000 students. Self-reported scales provide efficient means to assess substantial data volumes (Kormos & Gifford, Citation2014). Furthermore, they offer insights into individuals’ subjective experiences and beliefs regarding interest in nature and PEB, which may not be readily observable or measurable through other methods (Olli et al., Citation2001).

SIN and PEB are complex constructs, often challenging to capture through objective indicators alone. Self-reported scales allow us to delve into the nuanced aspects of human psychology, providing valuable insights into these constructs (Olli et al., Citation2001). In selecting the scales for our study, we ensured to choose instruments with rigorous development and validation processes to enhance their reliability and validity (Arnold et al., Citation2017; Byrka et al., Citation2016; Neurohr et al., Citation2023; Otto et al., Citation2014). Thus, despite acknowledging the limitations of self-reported scales, we believe that their use in this study yields valuable insights into students’ interest in and behavior toward nature and the environment.

Data analysis

We employed the Rasch rating scale model using the Winsteps software program (Linacre, Citation2021) to calibrate our measures of interest in nature (SIN) and general ecological behavior (GEB). Initially, a missing value analysis was conducted to exclude cases with significant missing data on the main scales, resulting in the exclusion of 138 participants (12.64%) and a reduced sample size of 954 participants. To ensure the quality of our measures, various steps were taken in line with standard practices for Rasch rating scale analysis (Boone & Staver, Citation2020; Boone et al., Citation2014; Davis & Boone, Citation2021; Otto et al., Citation2021). These steps included examining the dimensionality of the scales, assessing the functioning of the rating scales, evaluating reliability indices, and generating Wright maps from the data.

The reliability of the measurement instruments was assessed by evaluating person and item reliability as well as person and item separation (Boone & Staver, Citation2020; Boone et al., Citation2014). Critical values suggested by Malec et al. (Citation2007) were considered, such as an item reliability value of .90, person reliability of .80, person separation of 2.0, and item separation of 4.0. The data were controlled for unidimensionality using infit mean squares (MNSQ), within an acceptable range of 0.5 to 1.5 (Linacre, Citation2021; O'Connor et al., Citation2016). A principal component analysis of residuals (PCAR) was employed to assess unexplained variance, with an eigenvalue below 2.0 indicating evidence of unidimensionality (Bradley et al., Citation2016). Point measure correlations were examined to ensure that items were measuring the same construct, with correlations larger than 0.3 considered indicative of this (Li et al., Citation2019).

Furthermore, we evaluated the rating scale functioning and checked that all rating scale categories contribute to providing measurement information regarding respondents. Following other researchers, we used five guidelines by Linacre (Citation1999, Citation2002) for investigating the rating scale functioning: (1) 10 observations in each rating scale category, (2) normal distribution of observations, (3) outfit MNSQ is less than 2.0, (4) monotonic increase of average measures within each category and (5) orderly series of step calibrations that advance in a monotonic way. Targeting, floor and ceiling effects were evaluated as a final step of the Rasch analysis (Khadka et al., Citation2016; Wong et al., Citation2018). Good targeting was indicated by a difference between the average person measure and average item measure below 1.00 logits (Finger et al., Citation2012). Floor and ceiling effects, representing the presence of respondents at the extreme ends of the scale, were categorized as “excellent” when below 0.5% and as “poor” when greater than 5% (Fisher, Citation2007).

Additional analyses, including group comparisons, bivariate correlational analyses, and regression analyses, were conducted using IBM SPSS 26. Before applying the statistical tests, statistical outliers were identified and assumptions for parametric statistics and regression analysis were examined. While the SIN data were found to be normally distributed, as confirmed by the Shapiro-Wilk test (p > .05), this assumption was violated for the GEB. Homogeneity of variance using Levene’s Test was satisfied for the GEB (p > .05), but not for the SIN. Given the relative robustness of single-factor ANOVA to violations of the normal distribution assumption, ANOVA was used for further analyses (Blanca et al., Citation2017).

After controlling for assumptions in the regression analysis, we found a total missing data rate of 6.71% for variables related to activities in nature (time spent in nature: 4.4%; membership in environmental organization: 0.7%; hobby in nature: 3.1%). The missing data was primarily due to item nonresponse. To handle this, we used multiple imputation (MI) with all analysis variables, assuming the missing values were random (Little test: p = .772). MI has been shown to be superior to listwise deletion and other traditional methods (Allison, Citation2002; Buhi et al., Citation2008; Cox et al., Citation2014). During the regression analysis, we identified and removed five outliers. These cases not only exceeded the ±3 standard deviation threshold but also violated the guidelines for leverage values and Cook distances (Huber, Citation1981). Ultimately, all assumptions for linear regression were met, including multicollinearity, independent error, heteroscedasticity, and normality of residuals (Durbin-Watson = 1.910, VIF: 1.053–1.466, tolerance: 0.682–0.950, highest r = .693; Breusch-Pagan: p = .148; see ).

Table 5. Pro-environmental behavior regressed stepwise on interest in nature and activities in nature (time spent in nature, membership in an environmental organization, and hobby in nature), controlling for demographic variables, in grades 5 to 9.

Results

The results are presented in two parts. First, we report scale calibration details for the employed measurement instruments, including fit statistics and reliability information. Second, we present details of the cross-sectional study, focusing on interest in nature: its prevalence across grades 5 to 9, its role as a determinant of PEB, and its association with different kinds of nature activities.

Calibration of measurement instruments

Item reliability and item separation for both scales were high, with values above 0.90 and 4.0 (SIN: rel. = 1.00, sep. = 21.26; GEB: rel. = 1.00, sep. = 21.61). Person reliability and person separation for the SIN scale were satisfactory (person rel. = 0.89, person sep. = 2.84), while the GEB scale fell slightly below the suggested values (person rel. = 0.78, person sep. = 1.87).

The analysis supported the unidimensionality assumption for both scales. Item fit measures (MNSQ) demonstrated a good overall fit within the suggested range of 0.7 and 1.5. Principal component analysis of residuals (PCAR) showed eigenvalues of the unexplained variance in the first contrast, indicating unidimensionality for both scales (SIN: eigenvalue = 1.8; GEB: eigenvalue = 1.7). Point measure correlations for the SIN scale were positive and above 0.3, supporting the coherence of the items. Although one GEB item had a point measure slightly below 0.3 (0.28), its good item fit (MNSQ Infit = 1.41) justifies its inclusion in the analysis.

The rating scales performed as expected. They met the criteria of having at least 10 observations in each category and a uniform distribution of responses within the categories. MNSQ values for all categories were below 2.0, satisfying the criteria. Average measures and Andrich thresholds increase monotonically from the lowest to the highest rating scale category. Lastly, targeting, floor and ceiling effects were evaluated. The differences between the average person measure and average item measure were below 1.00 logits (ΔSIN = 0.17 logits; ΔGEB = 0.15 logits), indicating good targeting. Floor effects were minimal, with 0.2% (SIN) and 0% (GEB), while the ceiling effect for both scales was 0.1%. Overall, the Scale of interest in nature (SIN) and the General ecological behavior (GEB) scale can both be considered excellent instruments.

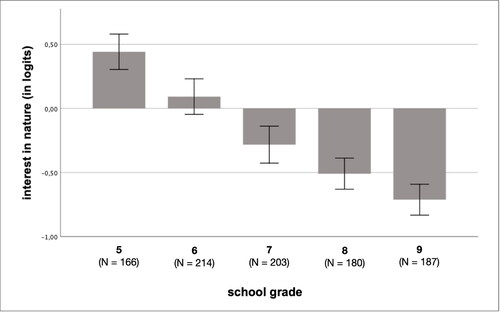

Interest in nature in relation to grade in school and nature activities

The study shows that lower secondary school students’ interest in nature decreases from grade 5 (M = 0.44, SD = 0.90) to 9 (M = −0.71, SD = 0.83), see and . The ANOVA indicated a significant difference between grades (F(4, 945) = 43,87, p < .001, η2 = .16). Post hoc comparisons using t-tests with Bonferroni correction indicated highly significant differences between almost all grades (p < .003), with small to large effect sizes (0.36 < d < 1.33). The further apart the compared grades, the higher the effect size. Only between grades 7 and 8 (t (381) = 2,337, p = .19) and grades 7 and 9 (t (365) = 2,343, p = .38) were no significant differences found.

Figure 1. Level of self-reported interest in nature (SIN) across grades 5 to 9; mean values and 95% confidence intervals.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of interest in nature (SIN in logits), general ecological behavior (GEB in logits), and days spent outside (0–7 days) in grades 5 to 9.

In addition to school grades, we also aimed to investigate whether nature activities change over the course of lower secondary school and what kinds of activities are associated with a strong interest in nature. To do so, we focused on three variables in detail: time spent in nature, active membership in environmental organizations and pursuing a hobby in nature. The results show that both time spent in nature (F(4,892) = 6,740, p < .001, η2 = .03) and pursuing a hobby in nature (F(4,940) = 3,495, p = .008, η2 = .01) differed significantly by grade level. This means that older students tend to spend less time in nature and are less likely to pursue a hobby in nature. For example, 48% of 5th graders spend time in nature 4–7 days per week, compared to only 29.4% of 9th graders. 73.5% of 5th graders, but only 58.6% of 9th graders, report having a hobby in nature. In terms of active membership in an environmental organization, there is a decreasing trend from grade 5 to 9, but we could not identify significant differences between the different school grades (F(4,940) = 0,806, p = .522). In general, we found that only 2.8–6% of all students were members of an environmental organization (highest percentage in grade 5 and lowest in grade 8).

Next, we analyzed which of these nature activities are associated with a strong interest in nature. Regarding time spent in nature, the results show that students who spend more time in nature (4–7 days a week) have a significantly higher SIN score than students who spend less time in nature (0–3 days a week) (t(896) = −10,518, p < .001, d = .70). The same applies to the other two variables describing nature activities: students show a higher interest in nature if they are members of environmental organizations (t(947) = −6,903, p < .001, d = .45) or pursue a hobby in nature (t(722,327) = −8,244, p < .001, d = .61).

To further assess the relationships between reported SIN scores, grade level, time spent in nature, membership in environmental organizations, and pursuing a hobby in nature, we examined Spearman’s rank correlations. The results are presented in . The SIN is significantly positively correlated with the frequency of time spent in nature (Spearman’s ρ = .38, p < .001), membership in an environmental organization (Spearman’s ρ (949) = .22, pursuing a hobby in nature (Spearman’s ρ = .25, p < .001), and significantly negatively correlated with students’ grade in school (Spearman’s ρ = −0.40, p < .001). Furthermore, grade level is significantly negatively correlated with frequency of time spent in nature (Spearman’s ρ = −0.17, p < .001) and pursuing a hobby in nature (Spearman’s ρ = −0.11, p = .001)). Hence, the older the students get, the less time they spend in nature and the less likely they are to pursue a hobby in nature.

Table 3. Correlation between self-reported interest in nature (SIN), grade in school, time spent in nature, membership in environmental organizations, and hobbies in nature (N = 945), levels of significance: ** for p <.01, * for p <.05.

Interest in nature and pro-environmental behavior

Finally, we analyzed the relationship between interest in nature and PEB. Since studies have already shown that experiences in nature have an influence on one’s PEB (Otto et al., Citation2021; Richardson et al., Citation2020), we included the three variables regarding nature activities in our analysis to control for possible effects. We found strong correlations between students’ interest in nature and PEB in grades 5 to 9 (see ). The strongest correlation between the two constructs is in grade 6 (r = .701, p = <.001, N = 214) and 7 (r = .722, p <.001, N = 203). Time spent in nature showed a moderate correlation with general ecological behavior (r = .35, p <.001, N = 949), whereas membership in an environmental association (r = .20, p <.001, N = 949) and pursuing a hobby in nature (r = .19, p <.001, N = 949) showed only low correlations with GEB.

Table 4. Bivariate correlations between interest in nature (SIN) and general ecological behavior (GEB) in grades 5 to 9.

Using a stepwise regression analysis, we followed recommendations from the literature (Petrocelli, Citation2003), and first entered general socio-demographics as more static variables in the regression analysis. Interest in nature was entered in a second and nature activities in a third step (see ). We first regressed students’ general ecological behavior levels (M = 0.14, SD =0.56) on age (M = 12.48, SD = 1.55) and gender (M = 0.48 SD = 0.50). We found students’ GEB to be systematically related to both variables, F(2, 946) = 64,054, p < .001, R2 = .119, explaining 12% of the variance in PEB (). After including interest in nature (M = −0.21, SD = 1.01) in the second step, the model explained 48.3% (F(3, 945) = 294,219), p <.001, R2 = .483, Adj. R2 = .481) of the variance in PEB. Interest in nature accounted for an additional 36.4% of variance above demographics. The gender variable, however, no longer explained significant variance in the model (β = .003, p = .840). In a third step, we included the variables for time spent in nature (M = 3.25, SD = 1.86), membership in environmental organizations (M = 0.04, SD = 0.20), and hobby in nature (M = 0.65, SD = 0.48). Including these three variables led to a slightly higher proportion of explained variance (F(6,942) = 153, 524, p <.001, R2 = .494, Adj. R2 = .411). Gender (β = .003) and hobby in nature (β = −0.01) did not emerge as significant predictors of general ecological behavior (p > .05). Even when all other variables were included in the model, interest in nature turned out to be the comparatively strongest determinant of PEB (β = .62).

In summary, the sociodemographic variables combined accounted for 12% of the variance in students’ PEB, interest in nature alone accounted for 36.4%, and activities in nature—time spent in nature and membership in an environmental organization—for another 1%. In other words, interest in nature determined whether a student would act in a pro-environmental way. In the full model (Step 3), gender no longer explains any variance in GEB (p = .916), nor does pursuing a hobby in nature seem to add any value to the model in this case (p = .749).

Discussion

Many studies have pointed to the increasingly severe conditions on our planet (IPCC, Citation2021). Extreme natural phenomena such as global warming, sea-level rise, glacier melting or biodiversity loss are clearly the result of human behavior over the past decades (Al-Ghussain, Citation2019; Brighenti et al., Citation2019; IPCC, Citation2021; Nerem et al., Citation2018). To counteract this trend, we must encourage a wider engagement in PEB, such as reducing individuals’ environmental impact and supporting the restoration of biodiversity (Richardson et al., Citation2020). To do so, it is of great importance to better understand determinants of PEB. Although studies have indicated that interest in nature has a direct effect on the development of willingness to engage in nature protection (Kals et al., Citation1999; Leske & Bögeholz, Citation2008; Vining & Ebreo, Citation1992), there have been no studies focusing on interest in nature and its relationship to PEB among adolescents. In our study, we aim to examine the previously under-studied construct of affective interest in nature in more detail and analyze its relationship to age (represented by grade level in school), nature activities, and PEB.

Comparing the cross-sectional data, we found that interest in nature decreases with increasing grade level (see ). We identified significant differences between almost all grades, especially when they were further apart. This is also reflected in the effect sizes: the greater the distance between two grades, the stronger the effect. Thus, students in the early years of secondary school exhibited greater interest in nature compared to those in later years. This aligns with previous studies showing a decreasing trend in environmental attitudes and behavior from primary school to high school (Bogner & Wiseman, Citation2002; Bogner et al., Citation2015; Collado et al., Citation2015; Otto et al., Citation2019; Torkar et al., Citation2020). As interest in nature can be considered an important aspect of environmental attitudes (Neurohr et al., Citation2023), we expected a similar pattern. Our findings support this hypothesis by demonstrating a significant decline in interest in nature during lower secondary school (from grade 5 to 9), expanding on previous research (Leske & Bögeholz, Citation2008). This trend is consistent with students’ level of involvement in nature activities. Both time spent in nature and engagement in nature-related hobbies decrease significantly as grade level increases. Although participation in environmental organizations remains relatively stable across grade levels, the overall percentage of students who are active members is notably low. These results are especially troubling when looking more closely at the relationship between activities in nature and interest in nature. All three nature activities studied exhibit a significant positive correlation with interest in nature. This suggests that students with more exposure to nature, involvement in environmental organizations, or engagement in nature-related hobbies also display higher levels of interest in nature. Older students may prioritize forming social connections and become more immersed in the digital world, leading to a disconnection from nature (Flammer et al., Citation1999; Kuss & Griffiths, Citation2017; Michaelson et al., Citation2020). As adolescents spend less time outdoors, their bond with nature weakens, resulting in a decline in interest in nature (Louv, Citation2005).

In addition, we shed light on the potential link between students’ interest in nature and their PEB, aiming to deepen understanding of the complex dynamics at play in shaping sustainable behaviors. Our analysis revealed robust correlations between interest in nature and PEB across all grade levels, with correlation coefficients ranging from .541 to .720. Furthermore, regression analysis confirmed this relationship, indicating that 36.4% of the variance PEB can be explained by SIN. These findings highlight the significance of interest in nature as not only positively associated with connection to nature, as previously demonstrated (Neurohr et al., Citation2023), but also with PEB. Consequently, interest in nature emerges as a valuable variable within the intricate framework influencing PEB, offering nuanced insights into the multifaceted nature of PEB. Identifying this relationship provides insights into the mechanisms underlying the development of sustainable PEB. When considered alongside other influencing factors, interest in nature may act as a catalyst which can be intentionally cultivated in both formal and non-formal learning settings. This realization opens avenues for tailored educational interventions designed to stimulate and sustain students’ interest in nature. Activities such as nature excursions, tending to plants in the classroom or a school garden, or observing birds or insects in the schoolyard can serve as effective strategies to foster interest in nature among students. Notably, direct interaction with natural elements has been shown to enhance individuals’ sense of connection to nature (Richardson et al., Citation2020). Research indicates that young individuals who spend leisure time in nature and actively engage with their surroundings demonstrate heightened interest in nature (Guiney, Citation2009; Neurohr et al., Citation2023; Sheldrake & Reiss, Citation2022). Our aim with these findings is not to propose a simplistic explanation centered solely on interest but rather to underscore the importance of this variable as one among many potential influencers that can be modified in classroom settings. By integrating a measurement of interest in nature into future studies assessing the effectiveness of learning interventions, researchers can gain a deeper understanding of the impact of educational strategies on students’ attitudes and behaviors toward the environment. This holistic approach holds promise for informing the design of more effective educational programs aimed at fostering sustainable PEB among young people.

Previous studies indicate that PEB can develop through experiences in nature (Otto et al., Citation2021; Richardson et al., Citation2020). The regression analysis in our study showed that time spent in nature and participation in an environmental organization together explain only 1.1% of the variance in environmental behavior. A hobby in nature does not explain any significant variance in PEB. This goes in line with prior research showing that time spent in nature can influence an individual’s affinity with and connection to nature (Chawla, Citation2020; Kals et al., Citation1999). However, the low amount of explained variance is consistent with Richardson et al. (Citation2020), suggesting that it is not time spent outside per se that influences environmental behavior, but how that time is spent. Nature activities like birdwatching or gardening have been found to be linked to PEB as well as connectedness with nature (Richardson et al., Citation2020). In general, meaningful and experiential activities related to students’ lives encourage positive PEB (Johnson & Činčera, Citation2023). Interestingly, PEB has been found to be especially high when children spent a lot of time in nature during their early years, especially in the form of unstructured play in nature (Guiney, Citation2009; Mackay & Schmitt, Citation2019; Whitburn et al., Citation2019).

Even one-day interventions can enhance environmental attitudes and connection to nature when they are filled with experiential activities (Kossack & Bogner, Citation2012; Sellmann & Bogner, Citation2013). However, lasting bonds with nature require longer and repeated experiences (Sellmann & Bogner, Citation2013; Stern et al., Citation2008). The same might be true for interest in nature. When students are regularly exposed to nature, they can develop an individual interest in nature over time (Krapp, Citation2002) and might act in a pro-environmental way out of their own motivation (Krapp, Citation2002; Krapp & Prenzel, Citation2011; Renninger & Hidi, Citation2002). We thus suggest that educational programs in ESD should systematically incorporate exploratory and ecological nature experiences to strengthen students’ interest in nature. Active involvement in environmental organizations during one’s free time also correlates with a higher interest in nature, a stronger connection to nature and greater environmental values in adolescents (Neurohr et al., Citation2023). Therefore, motivating adolescents to participate in environmental protection during their free time can foster sustainable PEB. This is meaningful, since studies suggest that early engagement in nature can predict adults’ PEB (Evans et al., Citation2018; Otto & Pensini, Citation2017; Wells & Lekies, Citation2006). Thus, ESD programs should be integrated into students’ education from an early age.

Promoting PEB among students through ESD programs necessitates a deeper understanding of the concept of “nature”, critical engagement with power relations, and recognition of environmental education’s entanglement in broader political-economic processes (Arenas, Citation2021; Fletcher, Citation2017). Initially, the conventional use of the term “nature” may reinforce a perceived dichotomy between human consciousness and the natural world, hindering holistic relationship with Earth and its ecosystems (Morton, Citation2007). To address this limitation, environmental education should explore alternatives to the nature-culture binary, embracing concepts such as “socionatures” (Braun & Castree, Citation1998) or distinguishing between “humans” and “nonhumans” rather than framing discussions solely around “humans” and “nature” (Fletcher, Citation2017). However, it is important to acknowledge that these alternatives may still maintain some level of distinction between humans and the biophysical world. Moreover, environmental education must confront material power relations that shape the “politics of nature” to avoid perpetuating environmental degradation (Fletcher, Citation2017). Neglecting these power dynamics could reinforce weak sustainability and individualistic growth economies, as critiqued by perspectives like the Nature Deficit Disorder thesis (Dickinson, Citation2013; Gruenewald, Citation2004). Effective environmental education should address not only environmental issues but also the cultural, economic, and political systems that contribute to them, including poverty, racial segregation, and overconsumption (Dickinson, Citation2013; Haluza-Delay, Citation2013). Furthermore, environmental education itself is embedded within political-economic systems, raising concerns about its alignment with neoliberal dynamics (Hursh et al., Citation2015). Therefore, understanding environmental education’s role within broader political-economic contexts is crucial for fostering meaningful change.

While our research primarily focuses on the concept of interest in “nature”, it is essential to address the concerns raised regarding the anthropocentric framing of nature (Fletcher, Citation2017). The definition of “interest in nature” as the specific relationship between a person and nature as an object of interest indeed implies a human-centric perspective. It could suggest an instrumental view of nature, valuing it based solely on its relevance or appeal to humans. However, our approach is grounded in the person-object theory (Krapp, Citation2002), which emphasizes building relationships between individuals and the object of interest (nature), fostering meaningful connections that recognize nature’s intrinsic value beyond its utility to humans. It is important to note that our usage of “interest in nature” aligns with established psychometric literature and our theoretical framework, where the object of interest is consistently conceptualized as something external to the individual (Krapp, Citation2002; Leske & Bögeholz, Citation2008). While alternatives such as “interest in non-human nature” may address some of the concerns raised, they may also introduce complexity and linguistic challenges. Moving forward, we recognize the significance of adopting a more non-anthropocentric perspective, acknowledging the intrinsic value of non-human nature independent of its utility to humans. This perspective underscores the reciprocal and interconnected relationships between humans and the natural world, recognizing nature as a subject with its own agency and value.

As noted in the methodology section, a potential limitation of our study lies in the use of self-reported scales, including the GEB scale, which has faced criticism for its perceived inability to capture the depth of information compared to measures of actual engagement in PEB. Self-reported scales rely on individuals’ subjective perceptions of their own interest or behavior, introducing a potential lack of objectivity and discrepancies between reported and actual behavior (Gatersleben et al., Citation2002; Kormos & Gifford, Citation2014). This subjectivity may introduce biases, such as social desirability bias, as participants may lack accurate insight into their motivations or actions. Additionally, participants may struggle to recall past experiences or behaviors accurately, potentially leading to response inaccuracies (Koller et al., Citation2023), thus comprising the reliability and validity of the collected data, which heavily relies on participants’ honesty and accuracy in reporting. Despite these limitations, the GEB remains a well-established measure of general ecological behavior that has been repeatedly validated as relevant for behaviors including energy use, transportation and mobility, and acceptance of nature conservation measures (e.g., Arnold et al., Citation2017; Byrka et al., Citation2016; Otto et al., Citation2014). While social desirability bias may have influenced our findings due to the use of self-reports, the GEB has demonstrated resistance to such bias (Kaiser, Citation1998; Oerke & Bogner, Citation2013). Research also suggests that while social desirability may have a minimally impact on environmental attitudes, its influence on environmental behavior is negligible (Oerke & Bogner, Citation2013). We ensured anonymity during questionnaire administration to mitigate potential biases, but future studies may benefit from including a social desirability index as a potential statistical covariate. To address these concerns and enhance the robustness of findings, future research should consider supplementing self-reported scales with alternative methods, such as behavioral observations and objective measures. Objective measures could involve device measurements, observations by trained observers, and peer ratings provided by individuals closely associated with the participant (e.g., parents, teachers) (Kormos & Gifford, Citation2014). Integrating diverse data sources can offer a more comprehensive and reliable understanding of individuals’ attitudes and behaviors toward nature and environment conservation.

Another limitation of our study is its cross-sectional design, preluding the establishment of causal relationships between interest in nature PEB. While our findings provide insights into the association between these variables at a single point in time, they do not indicate the direction of causality. To overcome this limitation and gain a deeper insight, future research should employ longitudinal study designs. Longitudinal studies would enable the examination of how changes in interest in nature correlate with subsequent changes in PEB, and vice versa. Additionally, experimental designs or intervention studies could shed light on the causal mechanisms underlying the relationship between interest in nature and PEB. Furthermore, researchers could explore potential mediating and moderating variables that may influence the link between interest in nature and PEB, including environmental attitudes, connection to nature, and social norms. Addressing these recommendations will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics between interest in nature and pro-environmental behavior, facilitating the development of effective interventions and educational programs aimed at promoting environmental conservation.

Conclusion

Our research contributes to a deeper understanding of adolescents’ interest in nature and its relationship with nature activities and PEB. The results of our study reveal a positive correlation between engagement in nature activities, interest in nature, and PEB among students from grades 5–9. Specifically, those spending more time in nature demonstrate stronger interest in it, and they also exhibit a higher level of engagement in PEB. However, concerning trends emerge among lower secondary school students, showing a decline in nature engagement and nature-related hobbies. Addressing this decline requires a comprehensive approach, with social policies facilitating increased access to nature for children and adolescents. Importantly, our study highlights a shift from connection to nature to a more refined focus on interest in nature. While connection to nature encompasses affective, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions, interest in nature, rooted in Schiefele et al. (Citation1993) concept, is focusing on the affective relationship between individuals and nature, driven by intrinsic motivation. Unlike connection to nature, which encapsulates a broader emotional bond and responsibility toward nature, interest in nature isolates the affective dimension, emphasizing the intrinsic desire to be captivated by nature. As projected urbanization limits the access to nature (World Health Organization, Citation2019), integrating nature activities into curricula becomes fundamental. Such initiatives might foster individual interest in nature, serving as a leverage to influence PEB. Understanding the link between interest in nature and PEB elucidates the mechanism driving PEB. Similar to how a fascination for science promotes deeper learning (Otto et al., Citation2020), interest in nature could serve as a motivating factor for students’ engagement in PEB. Moving forward, future studies should acknowledge interest as a pivotal factor in shaping attitudes and behaviors toward the environment. By dissecting the nuances of interest in nature, researchers can develop targeted interventions and policies aimed at fostering sustainable behaviors effectively.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (386.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We want to thank Annette Philipps, Theresa Krause-Wichmann, Helge Brunswig, and Maximilian Willrich for help with data entry and organization as well as the participating students and their teachers for contributing to this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://osf.io/q9kbn/ (DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/Q9KBN).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Al-Ghussain, L. (2019). Global warming: Review on driving forces and mitigation. Environmental Progress & Sustainable Energy, 38(1), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/ep.13041

- Allison, P. (2002). Missing data. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412985079

- Arenas, A. (2021). Pandemics, capitalism, and an ecosocialist pedagogy. Journal of Environmental Education, 52(6), 371–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2021.1999197

- Arnold, O., & Kaiser, F. G. (2016). Understanding the foot-in-the-door effect as a pseudo-effect from the perspective of the Campbell paradigm. International Journal of Psychology: Journal International De Psychologie, 53(2), 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12289

- Arnold, O., Kibbe, A., Hartig, T., & Kaiser, F. G. (2017). Capturing the environmental impact of individual lifestyles: Evidence of the criterion validity of the general ecological behavior scale. Environment and Behavior, 50(3), 350–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916517701796

- Bamberg, S., & Möser, G. (2007). Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2006.12.002

- Beery, T. H., & Wolf-Watz, D. (2014). Nature to place: Rethinking the environmental connectedness perspective. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 40, 198–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.06.006

- Berardi, U. (2017). A cross-country comparison of the building energy consumptions and their trends. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 123, 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2016.03.014

- Bezeljak, P., Torkar, G., & Möller, A. (2023). Understanding Austrian middle school students’ connectedness with nature. Journal of Environmental Education, 54(3), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2023.2188577

- Blanca, M. J., Alarcon, R., Arnau, J., Bono, R., & Bendayan, R. (2017). Non-normal data: Is ANOVA still a valid option? Psicothema, 29, 557. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2016.383

- Blankenburg, J., & Scheersoi, A. (2018). Interesse und Interessenentwicklung [Interest and interest development]. In D. Krüger, I. Parchmann, & H. Schecker (Eds.), Theorien in der naturwissenschaftlichen Forschung [Theories in science education research] (pp. 245–259). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-56320-5_15

- Bogner, F. X., & Wiseman, M. (2002). Environmental perception: Factor profiles of extreme groups. European Psychologist, 7(3), 225–237. https://doi.org/10.1027//1016-9040.7.3.225

- Bogner, F. X., Johnson, B., Buxner, S., & Felix, L. (2015). The 2-MEV model: Constancy of adolescent environmental values within an 8-year time frame. International Journal of Science Education, 37(12), 1938–1952. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2015.1058988

- Boone, W. J., & Staver, J. R. (2020). Advances in Rasch analyses in the human sciences (1st ed.). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43420-5https://ubdata.univie.ac.at/AC15714645

- Boone, W. J., Staver, J. R., & Yale, M. S. (2014). Rasch analysis in the human sciences. Springer. https://ubdata.univie.ac.at/AC14509431

- Bradley, K. D., Peabody, M. R., & Mensah, R. K. (2016). Applying the many-facet rasch measurement model to explore reviewer ratings of conference proposals. Journal of Applied Measurement, 17(3), 283–292.

- Braun, B., & Castree, N. (Eds.). (1998). Remaking reality: Nature at the millennium. Routledge.

- Brighenti, S., Tolotti, M., Bruno, M. C., Wharton, G., Pusch, M. T., & Bertoldi, W. (2019). Ecosystem shifts in Alpine streams under glacier retreat and rock glacier thaw: A review. Science of the Total Environment, 675, 542–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.221

- Brügger, A., Kaiser, F. G., & Roczen, N. (2011). One for all? Connectedness to nature, inclusion of nature, environmental identity, and implicit association with nature. European Psychologist, 16(4), 324–333. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000032

- Buhi, E., Goodson, P., & Neilands, T. (2008). Out of sight, not out of mind: Strategies for handling missing data. American Journal of Health Behavior, 32(1), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.32.1.8

- Byrka, K., Kaiser, F. G., & Olko, J. (2016). Understanding the acceptance of nature-preservation-related restrictions as the result of the compensatory effects of environmental attitude and behavioral costs. Environment and Behavior, 49(5), 487–508. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916516653638

- Chawla, L. (2020). Childhood nature connection and constructive hope: A review of research on connecting with nature and coping with environmental loss. People and Nature, 2(3), 619–642. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10128

- Cheng, J. C.-H., & Monroe, M. C. (2012). Connection to nature:children’s affective attitude toward nature. Environment and Behavior, 44(1), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916510385082

- Clayton, S., & Opotow, S. (2003). Identity and the natural environment: The psychological significance of nature [Book]. The MIT Press. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=138631&site=ehost-live

- Collado, S., Corraliza, J. A., Staats, H., & Ruiz, M. (2015). Effect of frequency and mode of contact with nature on children’s self-reported ecological behaviors. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 41, 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.11.001

- Cox, B., McIntosh, K., Reason, R., & Terenzini, P. (2014). Working with missing data in higher education research: A primer in real-world example. Review of Higher Education, 37(3), 377–402. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2014.0026

- Davis, J. L., Green, J. D., & Reed, A. (2009). Interdependence with the environment: Commitment, interconnectedness, and environmental behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(2), 173–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.11.001

- Davis, D. R., & Boone, W. (2021). Using Rasch analysis to evaluate the psychometric functioning of the other-directed, lighthearted, intellectual, and whimsical (OLIW) adult playfulness scale. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 2, 100054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2021.100054

- Dickinson, E. (2013). The misdiagnosis: Rethinking nature-deficit disorder. Environmental Communication, 7(3), 315–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2013.802704

- Dutcher, D. D., Finley, J. C., Luloff, A. E., & Johnson, J. B. (2007). Connectivity with nature as a measure of environmental values. Environment and Behavior, 39(4), 474–493. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916506298794

- Eichenberg, D., Bowler, D. E., Bonn, A., Bruelheide, H., Grescho, V., Harter, D., Jandt, U., May, R., Winter, M., & Jansen, F. (2021). Widespread decline in Central European plant diversity across six decades. Global Change Biology, 27(5), 1097–1110. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15447

- Eriksson, L., Garvill, J., & Nordlund, A. M. (2008). Acceptability of single and combined transport policy measures: The importance of environmental and policy specfic beliefs. Transportation Resarch Part A: Policy and Practice, 42(8), 1117–1128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2008.03.006

- Evans, G. W., Brauchle, G., Haq, A., Stecker, R., Wong, K., & Shapiro, E. (2007). Young children’s environmental attitudes and behaviors. Environment and Behavior, 39(5), 635–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916506294252

- Evans, G. W., Otto, S., & Kaiser, F. G. (2018). Childhood origins of young adult environmental behavior. Psychological Science, 29(5), 679–687. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617741894

- Finger, R. P., Fenwick, E., Pesudovs, K., Marella, M., Lamoureux, E. L., & Holz, F. G. (2012). Rasch analysis reveals problems with multiplicative scoring in the macular disease quality of life questionnaire. Ophthalmology, 119(11), 2351–2357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.05.031

- Fisher, W. P. (2007). Rating scale instrument quality criteria. Rasch Measurement Transactions, 21(1), 1095. https://www.rasch.org/rmt/rmt211m.htm

- Flammer, A., Alsaker, F. D., & Noack, P. (1999). Time use by adolescents in an international perspective. I: The case of leisure activites. In A. Flammer & F. D. Alsaker (Eds.), The adolescent experience. European and American adolescents in the 1990s (1st ed., pp. 33–60). Psychology Press.

- Fletcher, R. (2017). Connection with nature is an oxymoron: A political ecology of nature-deficit disorder. Journal of Environmental Education, 48(4), 226–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2016.1139534

- Gatersleben, B., Steg, L., & Vlek, C. (2002). Measurement and determinants of environmentally significant consumer behavior. Environment and Behavior, 34(3), 335–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916502034003004

- Gifford, R., & Nilsson, A. (2014). Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. International Journal of Psychology: Journal International De Psychologie, 49(3), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12034

- Goldrick, G. (2019). 2019 has been a year of cimate disaster. Yet still our leaders procrastinate. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/dec/20/2019-has-been-a-year-of-climate-disaster-yet-still-our-leaders-procrastinate

- Gruenewald, D. (2004). A Foucauldian analysis of environmental education: Toward the socioecological challenge of the Earth Charter. Curriculum Inquiry, 34(1), 71–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-873X.2004.00281.x

- Guiney, M. S. (2009). Caring for nature: Motivations for and outcomes of conservation volunteer work. University of Minnesota. ].

- Johnson, B., & Činčera, J. (2023). Relationships between outdoor environmental education program characteristics and children’s environmental values and behaviors. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 23(2), 184–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2021.2001756

- Haluza-Delay, R. (2013). Education for environmental justice. In R. B. Stevenson, M. Brody, J. Dillon, & A. E. J. Wals (Eds.), International handbook of research on environmental education (pp. 394–403). Routledge.

- Harackiewicz, J. M., Canning, E. A., Tibbetts, Y., Priniski, S. J., & Hyde, J. S. (2016). Closing achievement gaps with a utility-value intervention: Disentangling race and social class. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111(5), 745–765. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000075

- Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. A. (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_4

- Hidi, S., Renninger, K. A., & Krapp, A. (2004). Interest, a motivational construct that combines affective and cognitive functioning. In D. Dai & R. Sternberg (Eds.), Motivation, emotion and cognition: Integrative perspectives on intellectual functioning and development (pp. 89–115). Erlbaum. https://search-ebscohost-com.uaccess.univie.ac.at/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=113811&site=ehost-live

- Hidi, S., Weiss, J., Berndorff, D., & Nolan, J. (1998). The role of gender, instruction and a cooperative learning technique in science education across formal and informal settings. In L. Hoffman, A. Krapp, K. A. Renninger, & J. Baumert (Eds.), Interest and learning: Proceedings of the Seeon conference on interest and gender (pp. 215–227). IPN.

- Holstermann, N., Grube, D., & Bögeholz, S. (2010). Hands-on activities and their influence on students’ interest. Research in Science Education, 40(5), 743–757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-009-9142-0

- Huber, P. J. (1981). Robust statistics. Wiley. https://ubdata.univie.ac.at/AC00272151

- Hursh, D., Henderson, J., & Greenwood, D. (2015). Environmental education in a neoliberal climate. Environmental Education Research, 21, 299–318.

- IPBES. (2019). Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services (S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio, H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, et al., Eds.). IPBES Secretariat.

- IPCC. (2021). Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S. L. Connors, C. Péan, and S. Berger Eds.). Cambridge University Press.

- Kaiser, F. (1998). A general measure of ecological behavior1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(5), 395–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01712.x

- Kaiser, F. G., Byrka, K., & Hartig, T. (2010). Reviving campbell’s paradigm for attitude research. Personality and Social Psychology Review: An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, 14(4), 351–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310366452

- Kaiser, F. G., & Wilson, M. (2004). Goal-directed conservation behavior: The specific composition of a general performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(7), 1531–1544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2003.06.003

- Kaiser, F. G., Oerke, B., & Bogner, F. X. (2007). Behavior-based environmental attitude: Development of an instrument for adolescents. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(3), 242–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.06.004

- Kaiser, F., Hartig, T., Brügger, A., & Duvier, C. (2013). Environmental protection and nature as distinct attitudinal objects: An application of the campbell paradigm. Environment and Behavior, 45(3), 369–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916511422444

- Kals, E., Schumacher, D., & Montada, L. (1999). Emotional affinity toward nature as a motivational basis to protect nature. Environment and Behavior, 31(2), 178–202. https://publishup.uni-potsdam.de/opus4-ubp/frontdoor/index/index/docId/21844 https://doi.org/10.1177/00139169921972056

- Kellert, S. R., Case, D. J., Escher, D., Witter, D. J., Mikels-Carrasco, J., & Seng, P. T. (2017). The nature of Americans: Disconnection and recommendation for reconnection. DJ Case. https://natureofamericans.org/

- Khadka, J., Huang, J., Chen, H., Chen, C., Gao, R., Bao, F., Zhang, S., Wang, Q., & Pesudovs, K. (2016). Assessment of cataract surgery outcome using the modified catquest short-form instrument in China. PloS One, 11(10), e0164182. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164182

- Kleespies, M. W., Doderer, L., Dierkes, P. W., & Wenzel, V. (2021). Nature interest scale – Development and evaluation of a measurement instrument for individual interest in nature [original research]. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 774333. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.774333

- Knutti, R. (2019). Closing the knowledge-action gap in climate change. One Earth, 1(1), 21–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2019.09.001

- Koller, K., Pankowska, P. K., & Brick, C. (2023). Identifying bias in self-reported pro-environmental behavior. Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology, 4, 100087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cresp.2022.100087

- Kollmuss, A., & Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior. Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 239–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620220145401

- Kormos, C., & Gifford, R. (2014). The validity of self-report measures of proenvironmental behavior: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 40, 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.09.003

- Kossack, A., & Bogner, F. X. (2012). How does a one-day environmental education programme support individual connectedness with nature? Journal of Biological Education, 46(3), 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2011.634016

- Krapp, A. (2002). Structural and dynamic aspects of interest development: Theoretical considerations from an ontogenetic perspective. Learning and Instruction, 12(4), 383–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(01)00011-1

- Krapp, A. (2007). An educational–psychological conceptualisation of interest. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 7(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-007-9113-9

- Krapp, A., & Prenzel, M. (2011). Research on interest in science: Theories, methods, and findings. International Journal of Science Education, 33(1), 27–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2010.518645

- Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(3), 311. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/14/3/311 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14030311

- Larson, L. R., Szczytko, R., Bowers, E. P., Stephens, L. E., Stevenson, K. T., & Floyd, M. F. (2019). Outdoor time, screen time, and connection to nature: Troubling trends among rural youth? Environment and Behavior, 51(8), 966–991. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916518806686

- Larson, L. R., Whiting, J. W., & Green, G. T. (2011). Exploring the influence of outdoor recreation participation on pro-environmental behaviour in a demographically diverse population. Local Environment, 16(1), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2010.548373

- Leske, S., & Bögeholz, S. (2008). Biologische Vielfalt regional und weltweit erhalten – Zur Bedeutung von Naturerfahrung, Interesse an der Natur, Bewusstsein über deren Gefährdung und Verantwortung. Zeitschrift Für Didaktik Der Naturwissenschaften, 14, 167–184.

- Li, C.-Y., Romero, S., Bonilha, H. S., Simpson, K. N., Simpson, A. N., Hong, I., & Velozo, C. A. (2018). Linking existing instruments to develop an activity of daily living item bank. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 41(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278716676873

- Li, D., Zhao, L., Ma, S., Shao, S., & Zhang, L. (2019). What influences an individual’s pro-environmental behavior? A literature review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 146, 28–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.03.024