ABSTRACT

Three decades after the end of the Cold War, the United States still deploys about 100 nuclear weapons in Europe under NATO’s nuclear sharing policy. Two of the hosting states, Germany and the Netherlands, are now debating the prospective withdrawal of these weapons from their territory. This article presents the findings of a recent public opinion poll in the two countries, where German and the Dutch citizens expressed their views on the US withdrawal. Given the changing political landscape in these two countries, public support for these policies is a pertinent aspect of the political decisions over the future of US nuclear weapons in Europe.

Does stationing US nuclear weapons in Europe still make sense? As of 2021, there remain about 100 B61 nuclear bombs stored at military bases in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, and Turkey (Kristensen and Korda Citation2021). Deployed under NATO’s nuclear sharing policy, these air-deliverable weapons are supposed to serve as a tool of extended deterrence against Russia and assurance of European allies about the willingness of Washington to defend them with all means available.

Yet, there are new – and loud – voices on both sides of the Atlantic that question the need to continue this Cold War-era practice in the 21st century. While certainly not everyone agrees with the recent proposal by Harvard University’s Stephen Walt to “fold America’s nuclear umbrella” altogether (Walt Citation2021), many politicians in European hosting states advocate for at least an early removal of the remaining US bombs from their soil. Arguably, the debates over the future of US nuclear weapons in Europe are now of paramount importance given the attempts of the new US administration to balance its approach vis-à-vis Moscow (Squassoni Citation2021) and Europe’s ambition to seek strategic autonomy (Meijer and Brooks Citation2021).

In Germany and the Netherlands – two NATO countries – the prospective withdrawal of US nuclear weapons has gained particular prominence in the past year. German and Dutch citizens reported their views on a potential US withdrawal in our recent public opinion survey. Given the changing political landscape in these two countries, particularly the September 2021 general elections in Germany, public support for these policies will likely be a pertinent aspect of the political decisions over the future of US nuclear weapons in Europe.

Tornado replacement and a new round of the German withdrawal debate

“Nuclear weapons in Germany do not increase our security, on the contrary … it is about time that Germany precludes the(ir) future stationing. After all, other countries have done so without questioning NATO” (Der Tagesspiegel Citation2020a). These words from Rolf Mützenich, the chairperson of the parliamentary caucus of the German Social Democratic Party, reignited the German nuclear-sharing debate in May 2020. They, however, did not come out of the blue.

About two weeks earlier, the Ministry of Defense prepared a “compromise” proposal for the lower house of the German parliament (the Bundestag) to replace the aging fleet of dual-capable Tornado aircraft – partly with pan European Eurofighter Typhoons and partly with US-made F-18 fighter jets. Out of 45 F-18s, 30 would be designated for potential nuclear missions carrying an estimated 20 US B61 bombs stored at Büchel Air Base. This dual arrangement between the United States and Germany has been a pillar of NATO extended deterrence strategy in Europe since the 1950s. Yet, the costs of the acquisition of new aircraft – in the middle of the global COVID-19 pandemic – provided new ground for the argument that perhaps it was time to revisit the very idea of nuclear sharing (Meier Citation2020; Fuhrhop Citation2021).

Quite unsurprisingly, the views on a prospective nuclear withdrawal reflected traditional political divides. Representatives of the center-right Christian Democrats and Liberals strongly opposed any ideas for abandoning the existing nuclear sharing policy, highlighting the Russian threat, and accusing the withdrawal proponents of dangerous naivete (Der Tagesspiegel Citation2020b). The Greens, on the other hand, went as far as rejecting the legitimacy of nuclear deterrence strategies altogether. For example, a prominent Green parliamentarian Katja Keul recently called nuclear deterrence an “aberration” that should be abandoned by NATO “sooner rather than later” (Deutscher Bundestag Citation2021, 21693).

The debate will likely gain another impetus given the upcoming federal election in September 2021. The final decision over the acquisition of the new dual-capable aircraft was left up to the new members of the Bundestag and it is therefore likely that the future of nuclear sharing will feature among the foreign policy topics in the election campaign. The latest public opinion polls nevertheless suggest that the proponents of US withdrawal might gain an upper hand on the newly-drawn German political map (Reuters Citation2021), perhaps creating momentum for a shift in the long-standing nuclear sharing policy.

The treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons and nuclear-sharing practice in the Netherlands

Similar to Germany, the Dutch government has also been actively searching for a replacement for its aging dual-capable F-16 fleet and is currently considering the purchase of American F-35s for future nuclear missions. However, in the Netherlands, the debate over the need to continue the country’s participation in NATO’s nuclear sharing arrangement has had an additional impetus that has resonated strongly in the withdrawal debate: the recent adoption of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

The question mark hanging over the Dutch position toward the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons goes back to 2015 when pressure from pro-disarmament nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and the Dutch parliament compelled the government to actively participate in the United Nations deliberations leading up to the nuclear ban treaty (Onderco Citation2021, 43; Buijs Citation2018). In 2017, Dutch diplomats were the only representatives of a NATO country to attend the treaty’s actual negotiations – and subsequently the only participating country voting against its adoption (see Shirobokova Citation2018). Since then, the possibility of future Dutch accession has been repeatedly discussed in parliament and the public also seems to be largely supportive of such a step (Onderco et al. Citation2020; ICAN Citation2021).

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons accession, the expensive replacement of nuclear-capable aircraft, and the future of the nuclear-sharing arrangement are, therefore, issues closely interconnected in the Dutch political debate. The parliament has voted on a number of nuclear weapons-related motions over the past few years, and most Dutch political parties have at least flirted with the idea of ending Dutch participation in NATO’s nuclear sharing practice. While the recent elections in March 2021 were won by the status-quo-advocating People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy, the second-ranking Democrats 66, as well as GreenLeft, the Socialist Party, Labor Party, and Christian Union are all in favor of the withdrawal of US nuclear weapons from the Netherlands. As such, there is every reason to expect that the future of nuclear weapons in Europe will continue to be vigorously debated also in the post-election period.

Public views on a prospective US withdrawal

To learn more about the views of German and Dutch citizens on these issues, we worked with the Kieskompas–Election Compass research institute to conduct a public opinion survey on a large sample of the general public in the two countries.Footnote1 In the survey, respondents answered questions about their agreement with the withdrawal of US nuclear weapons from their country under different conditions.

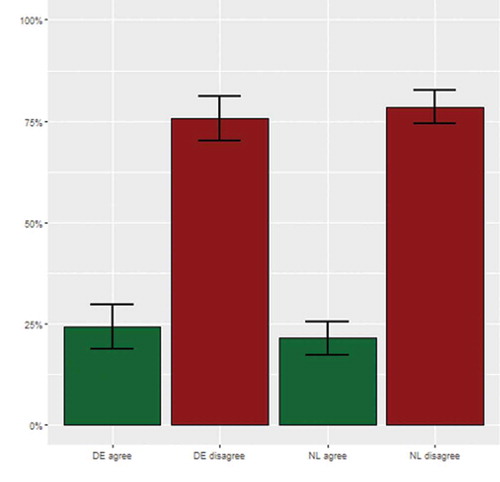

First, we asked the German and Dutch citizens about their support for the most status-quo-oriented option: that US nuclear weapons should not be withdrawn under any circumstances. As we show in , less than a quarter of respondents in both Germany and the Netherlands would agree with the statement that American nuclear bombs should remain in the two hosting countries no matter what. These findings suggest that the German and the Dutch public do not share the idea that the stationing of US nuclear weapons in Europe is an irreplaceable pillar of the security of NATO countries.

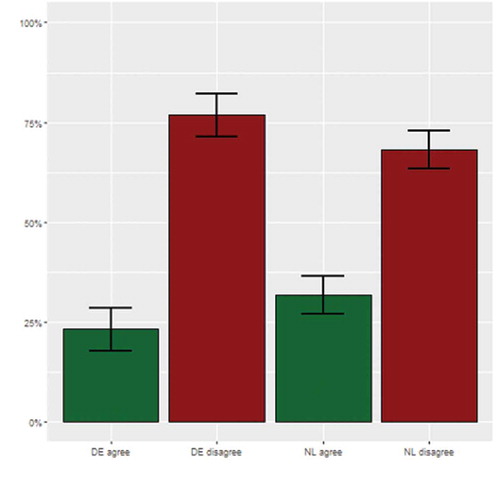

In the second part of our survey, we explored whether respondents would be receptive to trade-off logic: having US nuclear weapons withdrawn in exchange for additional reinforcements by US troops in Europe. As shown in , the majority of the public in both hosting countries would not agree that “more boots on the ground” would be a desirable policy route when dealing with the removal of US nuclear weapons. The German public seems to be even more disapproving of the idea, which is in line with the stronger pacifist tendencies in German society (Rassbach Citation2010), as well as the recent polls showing large public support for the withdrawal of US troops from Germany (DPA Citation2020).

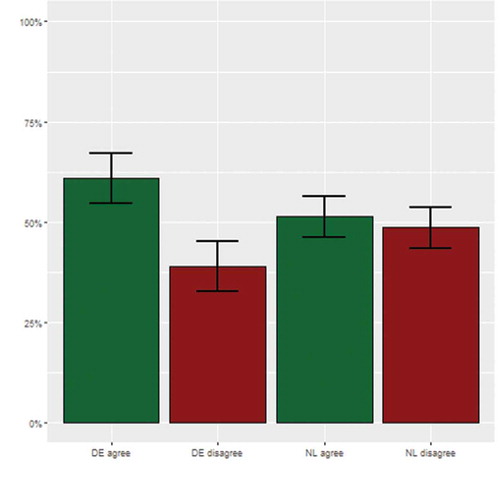

Another potential trade-off could be US nuclear withdrawal in exchange for strengthening conventional capabilities in European NATO countries. shows that this question is where the views of the public in the two countries differ the most. Whereas German citizens are more receptive to this European solution than to an increase in American troops, a clear majority of respondents (63 percent) still disagreed with this option. In our Dutch sample, on the other hand, the respondents were almost evenly split on this issue (51 percent agreed and 49 percent disagreed).

Figure 3. US nuclear weapons can be withdrawn if European NATO countries strengthen their conventional capabilities

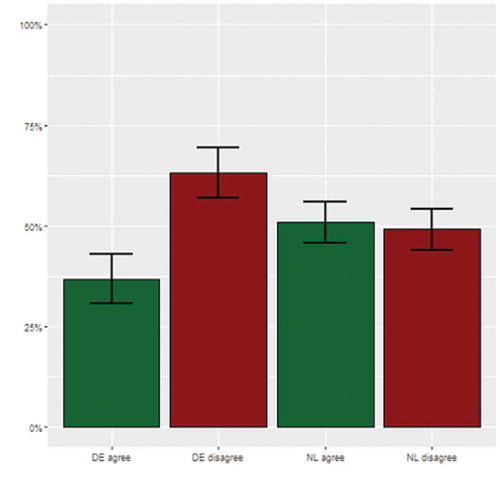

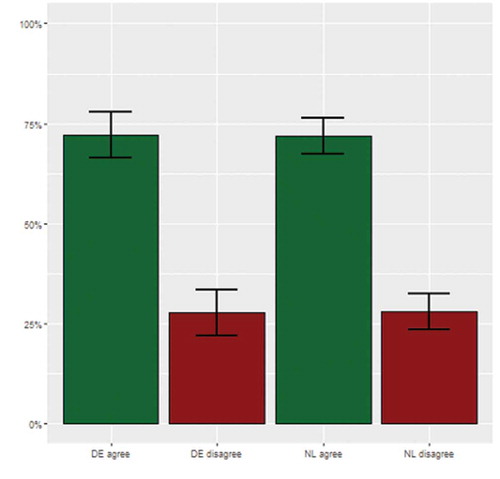

By far the most preferred option in both countries was the withdrawal of nuclear weapons in the context of new US-Russian arms control initiatives. As we show in , almost three-quarters of respondents in both the German and the Dutch sample would agree with such a course of action. Such a high support for bilateral arms control is in line with the view that nuclear weapons were initially accepted by Europeans essentially as bargaining chips in US–Soviet arms reduction negotiations (Egeland Citation2020).

Figure 4. US nuclear weapons in Germany can be withdrawn if the US and Russia agree on further arms control steps

Finally, we inquired whether the Germans and the Dutch would be supportive of an unconditional withdrawal of US nuclear weapons from Europe. As shown in , the two hosting countries differ in their views on this option. While Germans clearly prefer the arms control solution, removal without preconditions still received majority support among our respondents (61 percent agreed and 39 percent disagreed). In the Netherlands, on the other hand, the views were almost evenly split (51 percent agreed and 49 percent disagreed). These findings would be in line with the claim that while there is sizable support for the withdrawal of US nuclear weapons in both countries, German citizens exhibit more willingness to opt for a quick unilateral solution to nuclear stationing if the multilateral option through arms control negotiation is not on the table.

The future of US nuclear weapons in Europe

In June 2020, two leading members of President Joe Biden’s national security team engaged with the German withdrawal debate through an op-ed in the popular German news magazine Der Spiegel. The two American experts, with a plethora of experience in matters of defense and international security, made a persuasive plea for what they saw as “the heart of the trans-Atlantic bargain” (Flournoy and Townsend Citation2020). Yet, there are three major reasons why the removal of US nuclear weapons from Europe might become a reality in the coming years under Joe Biden’s watch.

First, after the dramatic disintegration of the nuclear arms control architecture during the four years of former president Donald Trump’s administration, Biden made a pledge to “head off costly arms races and re-establish [US] credibility as a leader in arms control” (The White House Citation2021). The extension of the New Strategic Arms Reductions Treaty (New START) for five years gives Washington and Moscow much-needed breathing space for negotiating a follow-up treaty that would establish limits for the arsenals of the two nuclear powers. Yet, it is already clear that any future bilateral talks will need to address a number of issues well beyond the New START focus, including nonstrategic nuclear weapons and ballistic missile defense in Europe (Vaddi Citation2021). Using the removal of US nuclear weapons from five European countries as a bargaining chip is a pragmatic strategy to reduce the Russian nuclear threat against Europe significantly. And, as the findings of our survey suggest, this step would likely find broad public support in NATO hosting countries.

Second, the renewed calls for the removal of US nuclear weapons from Europe came hand in hand with European disillusion with US handling of both nuclear affairs and Alliance politics under the Trump administration and the suggestions for building a greater role for French nuclear weapons in the European deterrence architecture (Kunz Citation2020). Such debates gained significant traction in some European countries. In Germany, for example, almost twice as many people would prefer a “eurodeterrent” over the continuation of the US nuclear umbrella (Czaputowicz et al. Citation2019). Despite various strategic, political, and legal obstacles to such a complex rearrangement of security relations on the European continent, such debates are inseparable from the contemporary calls advocating bold shifts toward strategic autonomy in Europe (Fiott Citation2018; Bargués Citation2021).

Third, the citizens’ support for the withdrawal together with the changing political landscape in hosting states might soon create an unprecedented political momentum for the removal of US nuclear weapons from Europe that has not existed for a very long time. This is particularly true for the upcoming federal elections in Germany. Since 2005, German politics has been dominated by the Christian Democrats, who vigorously opposed any revision of nuclear sharing practice in NATO. Yet, the elections will likely amplify the voice of political parties with strong antinuclear sentiments, particularly the Greens, who call for the removal of US nuclear weapons from Germany, even if such a decision would need to be done unilaterally. If the Greens replace the Christian Democrats as a leading party that would form the future German government, Berlin will likely propose a significant shift in NATO’s nuclear sharing practice. And, as suggested by our survey, such a move would likely enjoy the broad support of the German population.

Importantly, a new push for the removal of nuclear weapons from Germany would likely create a domino effect and thereby strengthen the arguments of nuclear critics in other European hosting countries. In the Netherlands, politicians and NGOs that advocate for the Dutch accession to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons would likely call on the government to follow the German lead. While our findings suggest that the Dutch are more wary of a unilateral solution than the Germans in this matter, a revision of NATO’s nuclear sharing policy following a German initiative would likely enjoy sizable popular support – particularly if Washington seizes the opportunity to negotiate a reciprocal reduction of nonstrategic weapons with Moscow. As such, while NATO’s nuclear sharing in Europe has survived the end of the Cold War, the current developments in European politics could finally signal the end of this decades-long practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Funding

Research for this paper was funded by the Charles University Research Centre programs UNCE/ HUM/028 (Peace Research Center Prague/Faculty of Social Sciences) and PROGRES Q18.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michal Smetana

Michal Smetana is Assistant Professor at Charles University and Coordinator of the Peace Research Center Prague. His articles have been published in International Affairs, Journal of Peace Research, International Studies Review, The Washington Quarterly, and many other academic and policy journals. He is the author of Nuclear Deviance: Stigma Politics and the Rules of the Nonproliferation Game.

Michal Onderco

Michal Onderco is Associate Professor of International Relations at Erasmus University Rotterdam. His book Networked Nonproliferation is forthcoming from Stanford University Press, and he has had papers published in International Studies Quarterly, European Journal of Political Research, Cooperation & Conflict, The Nonproliferation Review (and elsewhere).

Tom Etienne

Tom Etienne is a Research Fellow at Kieskompas – Election Compass in the Netherlands. He focuses on survey methods, political psychology and communication, and political parties. He has published numerous policy reports and his findings have been published in several national media outlets.

Notes

1. We collected the data between September 17–19, 2020 in the Netherlands (1,603 respondents in total) and between September 22–28, 2020 in Germany (1,352 respondents in total). We weighted the data to make our sample representative of age, gender, education, geographic location, and voter recall of the last parliamentary election.

References

- Bargués, Pol. 2021, February. “From ‘Resilience’ to Strategic Autonomy: A Shift in the Implementation of the Global Strategy?” EU-LISTCO Policy Paper Series, No. 09. https://www.eu-listco.net/publications/from-resilience-to-strategic-autonomy

- Buijs, Peter. 2018. “The Influence of NVMP’s Medical-Humanitarian Arguments on Dutch Nuclear Weapons Politics: The Netherlands Can Make a Difference in Reaching a Nuclear Weapons-Free World.” Medicine, Conflict and Survival 34 (4): 313–323. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13623699.2019.1591667.

- Bundestag, Deutscher. 2021. “Stenografischer Bericht. 207. Sitzung. Plenarprotokoll 19/207.” Accessed January 29 2021. https://dipbt.bundestag.de/dip21/btp/19/19207.pdf

- Czaputowicz, Jacek, Fu Ying, Brett McGurk, and Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer. 2019. The Berlin Pulse: German Policy in Perspective. Hamburg: Körber Stiftung. https://www.koerber-stiftung.de/fileadmin/user_upload/koerber-stiftung/redaktion/the-berlin-pulse/pdf/2019/TheBerlinPulse_2019_FINAL.pdf

- Der Tagesspiegel. 2020a. “Es Wird Zeit, Dass Deutschland Die Stationierung Zukünftig Ausschließt.” Accessed May 3 2020. https://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/spd-fordert-abzug-aller-us-atomwaffen-aus-deutschland-es-wird-zeit-dass-deutschland-die-stationierung-zukuenftig-ausschliesst/25794070.html

- Der Tagesspiegel. 2020b. “Rolf Mützenich Is on the Wrong Track.” Accessed May 8 2020. https://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/nukleare-teilhabe-rolf-muetzenich-ist-auf-dem-falschen-weg/25815082.html

- DPA. 2020. “Survey: Germans Largely in Favour of US Troops Withdrawing.” Accessed August 4 2020. https://www.dpa-international.com/topic/survey-germans-largely-favour-us-troops-withdrawing-urn%3Anewsml%3Adpa.com%3A20090101%3A200804-99-32198

- Egeland, Kjølv. 2020. “Spreading the Burden: How NATO Became a ‘Nuclear’ Alliance.” Diplomacy and Statecraft 31 (1): 143–167. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09592296.2020.1721086.

- Fiott, Daniel. 2018.“ Strategic Autonomy: Towards ‘European Sovereignty’ in Defence?” European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS). Accessed May 12 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/resrep21120.pdf

- Flournoy, Michèle, and Jim Townsend. 2020. “Striking at the Heart of the Trans-Atlantic Bargain.” Der Spiegel, Accessed June 3 2020. https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/biden-advisers-on-nuclear-sharing-striking-at-the-heart-of-the-trans-atlantic-bargain-a-e6d96a48-68ef-49ab-8a0c-8a979abf2bb4

- Fuhrhop, Pia. 2021. “The German Debate: The Bundestag and Nuclear Deterrence.” In Europe’s Evolving Deterrence Discourse, edited by Amelia Morgan and Anna Péczeli, 27–38. Livermore, CA: Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

- ICAN. 2021. “NATO Public Opinion on Nuclear Weapons.” Accessed May 12 2021. https://www.icanw.org/nato_poll_2021

- Kristensen, Hans M., and Matt Korda. 2021. “United States Nuclear Weapons, 2021.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 77 (1): 43–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2020.1859865.

- Kunz, Barbara. 2020. “Switching Umbrellas in Berlin? the Implications of Franco-German Nuclear Cooperation.” Washington Quarterly 43 (3): 63–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2020.1814007.

- Meier, Oliver. 2020. “German Politicians Renew Nuclear Basing Debate.” Arms Control Today. Accessed June 2020. https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2020-06/news/german-politicians-renew-nuclear-basing-debate

- Meijer, Hugo, and Stephen G Brooks. 2021. “Illusions of Autonomy: Why Europe Cannot Provide for Its Security if the United States Pulls Back.” International Security 45 (4): 7–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00405.

- Onderco, Michal. 2021. “The Dutch Debate: Activism Vs. Pragmatism.” In Europe’s Evolving Deterrence Discourse, edited by Amelia Morgan and Anna Péczeli, 39–50. Livermore, CA: Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

- Onderco, Michal, Michal Smetana, Sico Van der Meer, and Tom W. Etienne. 2020. “When Do the Dutch Want Their Country to Join the Nuclear Ban Treaty? Findings of a Public Opinion Survey in the Netherlands.” Working Paper.

- Rassbach, Elsa. 2010. “Protesting US Military Bases in Germany.” Peace Review 22 (2): 121–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10402651003751321.

- Reuters. 2021. “German Greens Overtake Conservatives as Chancellor Candidates Announced.” Accessed April 20 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-germany-election-poll/german-greens-overtake-conservatives-as-chancellor-candidates-announced-idUSKBN2C72IX

- Shirobokova, Ekaterina. 2018. “The Netherlands and the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.” Nonproliferation Review 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10736700.2018.1487600.

- Squassoni, Sharon. 2021. “Why Biden Should Abandon the Great Power Competition Narrative.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 77 (1): 3–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2020.1859854.

- Vaddi, Pranay. 2021. “How Biden Can Advance Nuclear Arms Control and Stability with Russia and China.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 77 (1): 18–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2020.1859862.

- Walt, Stephen M. 2021. “It’s Time to Fold America’s Nuclear Umbrella: Using Washington’s Nuclear Arsenal to Protect Its Allies No Longer Makes Any Sense.” Foreign Policy, Accessed March 23 2021. https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/03/23/its-time-to-fold-americas-nuclear-umbrella/

- The White House. 2021. “Interim National Security Strategic Guidance.” Washington, D.C. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NSC-1v2.pdf