ABSTRACT

As part of a larger survey, we asked social workers whether they had been involved in medical assistance in dying (MAID) so far. Of the 367 survey participants, 141 reported that they had. These were invited to describe their roles, needs, and sense of competence, focusing on their last MAID experience. Roles were diversified, beginning before and extending beyond the provision of MAID. Nearly 60% needed training on MAID. Perceived competence was lower among those lacking training. Findings point to educational needs that must be addressed to ensure the quality of end-of-life care and the well-being of social workers who engage in MAID.

Introduction

End-of-life care practices have changed drastically in the last two decades, with many jurisdictions having legalized some forms of assisted death (Fujioka et al., Citation2019; Gupta & Blouin, Citation2021). Medical assistance in dying (MAID) became a legal option in Canada on 17 June 2016, allowing medical and nurse practitioners to prescribe, provide or administer a substance to an eligible person, at their request, to bring about death (Criminal Code, art. 241.1). MAID had been legalized in the Canadian province of Quebec six months earlier, on 10 December 2015, through the Act respecting end-of-life care (Citation2014).

To qualify for MAID under the current Canadian legislation, a person must “(a) be eligible […] for health services funded by a government in Canada; (b) be at least 18 years of age and capable of making decisions with respect to their health; (c) have a grievous and irremediable medical condition; (d) have made a voluntary request for MAID […]; and (e) give informed consent to receive MAID after having been informed of the means that are available to relieve their suffering, including palliative care” (Criminal Code, art. 241.2(1)). A person has a grievous and irremediable medical condition if “(a) they have a serious and incurable illness, disease or disability; (b) they are in an advanced state of irreversible decline in capability; and (c) that illness, disease or disability or that state of decline causes them enduring physical or psychological suffering that is intolerable to them and that cannot be relieved under conditions that they consider acceptable” (Criminal Code, art. 241.2(2)). By the end of 2020, 21589 Canadians had received MAID, mostly from a physician (Health Canada, Citation2021). Discussions are ongoing in Canada as to whether access to MAID should be widened, including through advance requests from individuals who fear losing their capacity to make health-related decisions (Government of Canada, Citation2020; Quebec National Assembly, Citation2021).

As a result of greater access to assistance in dying, social workers practicing in health care increasingly encounter clients who wish to die. With self-determination as the primary ethical principle guiding their profession (CASW, Citation2005; Government of Quebec, Citation2020; NASW, Citation2021), and given their knowledge of family dynamics and communication skills (Csikai, Citation1999), social workers are uniquely qualified to interact with persons considering MAID to end their suffering. For example, they may help clients distinguish between care options and make decisions based on their own values; investigate the impact of personal and contextual factors on motivations for a hastened death, including quality-of-life considerations and how the desire relates to their suffering; assess capacity for informed consent to MAID; advocate for clients’ rights; assist family members in understanding and supporting their loved one’s choice; and provide emotional support to families and coworkers before and after the patient has passed away (Antifaeff, Citation2019; CASW, Citation2016; Fujioka et al., Citation2018; Selby et al., Citation2021).

Death that occurs through MAID is a unique experience for healthcare professionals that has been described as both rewarding and emotionally challenging (Hébert & Asri, Citation2022; Ward et al., Citation2021). To date, however, research has largely focused on physicians’ and nurses’ experiences with assisted dying (Bellens et al., Citation2019; Brooks, Citation2019; Elmore et al., Citation2018; Hébert & Asri, Citation2022; Khoshnood et al., Citation2018; Pesut et al., Citation2020; Shaw et al., Citation2018; Variath et al., Citation2020; Ward et al., Citation2021; Winters et al., Citation2021). Studies that have targeted social workers were published some years ago (e.g., Ganzini et al., Citation2002; Leichtentritt, Citation2002; Miller et al., Citation2004) or were qualitative in nature, and hence based on small samples (e.g., Antifaeff, Citation2019; Mills et al., Citation2021; Norton & Miller, Citation2012).

Social workers’ actual professional experiences with MAID have thus been understudied compared to physicians and nurses. The current paper addresses a gap in the literature by reporting on the experiences of social workers who have been directly involved in the MAID process in Quebec. Findings highlight unmet needs for support, education, and training. Addressing these needs is paramount to improving the MAID process and the well-being of social workers who agree to be involved.

Methods

Design, target population, and sampling

The data come from a Quebec-wide, anonymous, web- and paper-based survey on social workers’ attitudes toward the extension of the current MAID legislation – which requires most patients to have decision-making capacity – to incompetent patients who would have requested MAID through an advance request prior to losing capacity. The survey was conducted between February and June 2021, with the assistance of the Ordre des travailleurs sociaux et des thérapeutes conjugaux et familiaux du Québec (OTSTCFQ) which regulates the profession of social work in Quebec. Membership in the OTSTCFQ is required to bear the title of social worker in Quebec. Given its focus, the survey specifically targeted social workers whose practices include persons with dementia.

Membership to the OTSTCFQ and working with dementia clients were the sole eligibility criteria to the survey. The OTSTCFQ had no means of identifying which of its members were eligible to the survey. The research team was thus provided with the list of all OTSTCFQ members who had not explicitly refused to be solicited for research purposes, irrespective of whether they were working with dementia clients. This feature precludes establishing a response rate, as the number of eligible individuals in the sampling frame is unknown.

Listed social workers were first sent a personalized e-mail invitation to take part in the survey. The e-mail stated the aim of the survey, explained how recipients were identified, and addressed issues of privacy and anonymity. It also contained the electronic link to the questionnaire developed with LimeSurvey, along with the recipient’s personal single-use access code. The e-mail was followed by two electronic reminders, sent one and two weeks later.

To reach more potential participants (Dillman et al., Citation2014), 500 social workers were then selected randomly among the non-respondents and mailed a survey package containing a personalized cover letter, a letter from the OTSTCFQ encouraging participation in the survey, the questionnaire, and a stamped return envelope addressed to the research office. A thank you/reminder postcard followed two weeks later. As detailed elsewhere (Bravo et al., Citation2022), 367 social workers judged eligible returned a usable questionnaire, either electronically or by mail.

Data collection

The questionnaire included 21 items relevant to the current paper, mostly accompanied by 5-point Likert-type scales. One item assessed respondents’ attitudes toward the current MAID legislation, while others collected sociodemographic and work-related data. Toward the end of the questionnaire, respondents were asked whether they had been professionally involved in the MAID process so far. Those who had were asked to focus on their latest MAID case and describe their roles, needs, and perceived competence regarding this case.

Data analysis

Summary statistics are reported as means ± standard deviations, or as counts with percentages in parentheses. Chi-square, t-tests and ANOVAs were used to explore differences between subgroups. Analyses were conducted with SPSS for Windows, version 25, and all reported p-values are two-sided.

Results

Comparing social workers with and without MAID experiences

Of the 367 survey participants, 141 (38.4%) reported having been involved in the MAID process since the legislation came into effect in Quebec. compares their characteristics to those of survey participants without any MAID experience at the time of data collection. Social workers who had engaged in MAID prior to the survey were more likely to be born in Canada, to practice in hospitals with clients who had reached the end of their life, and to have received assistance-in-dying requests from clients or families (not necessarily formal MAID requests), than those with no prior MAID experiences. They were also more likely to have been trained in palliative care or on MAID, and less likely to feel the need for training on MAID. In addition, compared to social workers with no MAID experiences, those with such experiences were more likely to support the current MAID legislation and to be aware of their right to conscientious objection afforded by article 241.2(9) of the Criminal Code and article 50 of the Act respecting end-of-life care. Focusing on respondents who reported having been involved in the MAID process, it is quite worrisome to find that 36.4% had not been trained on MAID and 22.1% did not know that they could refuse to be involved. Also noteworthy, 5% of social workers who had participated in the MAID process did not support the MAID legislation in effect at the time.

Table 1. Survey respondent characteristics, stratified by whether they reported having been involved in the MAID process.

Roles, needs, and perceived competence

summarizes social workers’ experiences with their last MAID case. The number of tasks assumed varied widely, from one for 3.5% of the respondents to 10 or more for 14% (median: 6). Assistance with decision making and emotional support to clients and families were the most common tasks, reported by 73.8% to 87.2% of the respondents. These were followed by providing procedural support to the person (69.5%), informing about end-of-life care (63.8%), and assessing social functioning (59.6%). Notably, 40.4% of social workers were present when MAID was administered.

Table 2. Social workers’ experiences with their last MAID case (n = 141).

Most social workers (85.5%) rated the emotional charge generated by their most recent MAID case as medium or high; 62.4% felt the need for a break to process their emotions; and 75.9% felt supported by their work environment. Ninety percent of social workers who rated their emotional charge as high felt the need for a break, compared to 10% of those who rated it as low (χ2 = 43.8, p < .001). However, the level of emotional charge was not associated with whether the respondent felt supported by their work environment (χ2 = 1.3, p = .528). Interestingly, social workers who were at the patient’s side during the MAID procedure did not rate their emotional charge higher than those who were not present (χ2 = 2.4, p = .308). However, they were more likely to feel the need for a break (77%) than those who did not witness the procedure (52%) (χ2 = 8.9, p = .003).

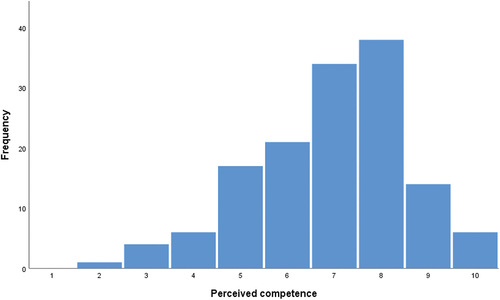

Perceived competence was relatively high, with a mean of 6.9 (median: 7) on a scale from 1 (incompetent) to 10 (very competent) (cf. and ). On average, competence was rated lower by social workers who had not received any training in palliative care (6.4 vs. 7.3, p < .001) or on MAID (6.6 vs. 7.2, p = .035) and by those who expressed the need for training on MAID (6.5 vs. 7.5, p < .001). Competence rating was not related to level of emotional charge (F = 1.7, p = .182) nor to whether respondents felt supported by their work environment (t = 1.0, p = .306). It was, however, related to respondents feeling the need for a break (t = 2.5, p = .014), with those who expressed that need rating their competence higher, on average, than the others (7.2 vs. 6.5).

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study is the first to describe social workers’ experiences with MAID in the current Canadian context. The findings add to the emerging body of literature on healthcare professionals’ experiences with assistance in dying, by giving voice to a group of professionals often overlooked. We found evidence of unmet needs for support, education, and training among social workers who had engaged in MAID, with impact on their sense of competence and well-being.

Nearly 40% of our survey participants had been involved in the MAID process at the time of the survey. This percentage should not be interpreted as a prevalence rate of MAID involvement among Quebec social workers practicing in health care. Our sample is not representative of this population because the survey was restricted to social workers whose practices include patients with dementia. Nonetheless, it provides valuable information on social workers’ experiences with MAID and on how they were affected. These experiences most likely did not involve persons with dementia-induced decisional incapacity, because MAID is not currently accessible to this population. As mentioned earlier, “being capable of making decisions with respect to their health” is a key element of the current MAID legislation.

Our findings concur with those of others regarding the diversity of tasks social workers may be called upon to perform in the context of an assisted death (Antifaeff, Citation2019; Fujioka et al., Citation2018). Most tasks deal with empowering clients to make end-of-life decisions for themselves and supporting loved ones of those who opt for MAID. As in the study reported by Selby et al. (Citation2021), social workers who participated in our survey described their role as beginning before and extending beyond the provision of MAID.

Effectively performing these tasks requires adequate professional training on end-of-life issues, and on MAID specifically. While survey participants with MAID experiences more often reported having been trained in palliative care and on MAID than those without, roughly half expressed the need for (perhaps further) training on MAID. Importantly, sense of competence was rated lower among social workers who expressed the need for training on MAID. While different from being competent, feeling competent may impact the delivery of quality care at the end of life.

Somewhat counter-intuitively, competence was rated higher among social workers who felt the need for a break after being involved with their last MAID case. Perhaps competence increases awareness of the emotional impact of an involvement in MAID. Still, the statistically significant relationship that we observed between competence and needing a break must be interpreted cautiously as it may reflect confounding, i.e., be the result of unmeasured variables. Moreover, the average difference in competence between social workers who needed to break and those who did not is less than one point, on a scale from 1 to 10, and may not be clinically significant.

We did not query social workers about which specific aspects of the MAID process they felt less prepared for. The right to conscientious objection is clearly one topic that should be addressed in future training. This would spare some social workers from getting involved when doing so would go against their values. A small number of survey participants reported being opposed to the current MAID legislation, but nonetheless contributing to the process. This finding is in line with Ganzini et al. (Citation2002), who conclude that “[e]ven though not all hospice […] social workers [in Oregon] support the Death with Dignity Act, they are all willing to care for patients who make this choice” (p. 588). Future studies could explore the underlying reasons. Are these social workers aware that they can refuse to be involved? If so, do they feel pressured to participate despite their discomfort? Does pressure originate from their working environment and coworkers, or is it internalized, resulting from social workers’ deep commitment to upholding the principles of self-determination and autonomy dear to their profession?

As for experiences with MAID, the small body of literature addressing educational needs of healthcare professionals in this area of practice has focused on physicians (Brown et al., Citation2020; Gewarges et al., Citation2020; Macdonald et al., Citation2018). While means to address the educational needs of physicians (e.g., course-based; conferences and practice guidelines available online; role playing; mentorship) (Kelley et al., Citation2020; Selby et al., Citation2021) may be suited for other healthcare professionals, social workers may have unique needs related to the content and delivery mode of MAID educational materials. These should be explored in future studies. Meanwhile, suggests that content should address how best to assist clients with decision making and provide emotional support when the decision has been made to seek an assisted death. As pointed out by Ogden and Young (Citation1998), “the principles of self-determination and autonomy, which are germane to social work in North America, present unique difficulties when dealing with seriously ill persons who want to die” (p. 162). Social workers require guidance, perhaps in the form of practical steps to follow (Csikai & Bass, Citation2000), on how to balance these principles with the need to protect vulnerable persons.

Given that social workers spend more time with their clients than do physicians (Ogden & Young, Citation1998), other topics to address in educational materials or training sessions designed specifically for social workers include strategies to uncover the reasons behind the wish to die (e.g., quality of life considerations, social isolation, depression) and the extent to which alternative means to relieve suffering should be discussed (e.g., continuous deep sedation). Training should also focus on assessing decision-making capacity to request MAID, a task that often falls on social workers (cf. ). Determining whether the person’s judgment is compromised by mental illness, and the role that emotions such as lack of hope, frustrations, and anger play in the decision to seek MAID, may be challenging (Charland et al., Citation2016; Ogden & Young, Citation2003). Lastly, as many societies are increasingly multicultural, training should assist social workers in dealing appropriately with values that they may not share.

As found for other professional groups (Hébert & Asri, Citation2022; Oczkowski et al., Citation2021; Variath et al., Citation2020), our study reveals that involvement in MAID may place a significant emotional burden on social workers. Like other healthcare professionals, social workers who experience intense negative emotions from participating in MAID may choose to stop participating (Oczkowski et al., Citation2021), depriving persons requesting a hastened death of their unique skills. It is thus important to find ways to attenuate burden, such as providing opportunities and space in the workplace to debrief around their latest MAID case and openly discuss possible tensions between personal and professional values (Pesut et al., Citation2020; Ward et al., Citation2021).

Limitations

As already mentioned, our findings lack generalizability to social workers practicing in health care in Quebec. Replicating our study among all those who have been involved in the MAID process, irrespective of their client groups, would provide a more complete picture of their lived experiences. Extension of our study to other Canadian provinces is also warranted.

Survey participants were asked to describe emotions linked to their latest MAID case. We felt that this approach was preferable to one that would have asked respondents to average the intensity of their emotions over several MAID cases. However, some participants, perhaps unconsciously, may have focused on cases that they had found particularly challenging. As a result, emotional charge may have been overrated, and perceived competence underrated.

By relying on a quantitative approach, we were able to reach a relatively large sample of social workers with MAID experiences. However, due to the need to limit the length of the questionnaire, only a few questions were put to those with such experiences. Complementing our approach, in-depth qualitative interviews would allow further exploration of social workers’ challenges. Interviews could explore, for instance, how social workers deal with assistance-in-dying requests, what influences their decision to remain engaged with clients who opt for MAID, what aspects of the process they consider more complex (legal, ethical, psychosocial), and how best to address their educational needs in those areas. Studies on conscientious objection would also be warranted. Given social workers’ divers roles (cf. ), do objectors refuse involvement in the entire process or only parts of it (e.g., assessing eligibility, signing the form, being present while MAID is being delivered)?

Conclusion

Social workers described their roles as spanning the entire MAID process, from providing information on end-of-life care options to supporting families and coworkers after the person’s death. Most considered their last MAID case emotionally demanding and voiced educational needs that must be addressed to foster their well-being and ensure quality care for clients who opt for MAID.

Author contributions

G. B., N. D.-C., I. D., and M.-E. B designed the study and secured funding. M. R. and L. T. were involved in data collection and analysis. G. B. wrote the paper, which was critically reviewed by all coauthors. All coauthors approved the final version of the paper.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the CIUSSS de l’Estrie – CHUS (file #2021–3798).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Geneviève Cloutier and Alain Hébert from the OTSTCFQ for making this study possible.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The data used for this paper are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Act respecting end-of-life care. (2014). Available from https://www.legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/document/cs/S-32.0001.

- Antifaeff, K. (2019). Social work practice with medical assistance in dying: A case study. Health & Social Work, 44(3), 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlz002

- Bellens, M., Debien, E., Claessens, F., Gastmans, C., & Dierckx de Casterlé, B. “It is still intense and not unambiguous.” Nurses’ experiences in the euthanasia care process 15 years after legalisation. (2019). Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(3–4), 492–502.Blinded. for review. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15110

- Bravo, G., Delli-Colli, N., Dumont, I., Bouthillier, M. -E., Rochette, M., & Trottier, L. (2022). Social workers' attitudes toward medical assistance in dying for persons with dementia: Findings from a survey conducted in Quebec, Canada. Journal of Social Work in End-Of-Life & Palliative Care, 18(3), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/15524256.2022.20933142

- Brooks, L. (2019). Health care provider experiences of and perspectives on medical assistance in dying: A scoping review of qualitative studies. Canadian Journal on Aging, 38(3), 384–396. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980818000600

- Brown, J., Goodridge, D., & Thorpe, L. (2020). Medical assistance in dying in health sciences curricula: A qualitative exploratory study. Canadian Medical Education Journal, 11(6), e79–89. https://doi.org/10.36834/cmej.69325

- Canadian Association of Social Workers (CASW). (2005). Code of Ethics. Available from https://www.casw-acts.ca/files/documents/casw_code_of_ethics.pdf.

- Canadian Association of Social Workers (CASW). (2016). Discussion paper: Medical assistance in dying. Available from https://www.casw-acts.ca/en/discussion-paper-medical-assistance-dying.

- Charland, L. C., Lemmens, T., & Wada, K. (2016). Decision-making capacity to consent to medical assistance in dying for persons with mental disorders. Journal of Ethics in Mental Health, Open volume, 1–14. Available from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2784291

- Criminal Code. Available from https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-46/.

- Csikai, E. L. (1999). Euthanasia and assisted suicide: Issues for social work practice. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 31(3–4), 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1300/J083v31n03_04

- Csikai, E. L., & Bass, K. (2000). Health care social worker’s views of ethical issues, practice, and policy in end-of-life care. Social Work in Health Care, 32(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1300/J010v32n02_01

- Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Elmore, J., Wright, D. K., & Paradis, M. (2018). Nurses’ moral experiences of assisted death: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Nursing Ethics, 25(8), 955–972. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733016679468

- Fujioka, J. K., Mirza, R. M., Klinger, C. A., & McDonald, L. P. (2019). Medical assistance in dying: Implications for health systems from a scoping review of the literature. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 24(3), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819619834962

- Fujioka, J. K., Mirza, R. M., McDonald, L. P., & Klinger, C. A. (2018). Implementation of MAID: A scoping review of healthcare professionals’ perspectives. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 55(6), 1564–1576.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.02.011

- Ganzini, L., Harvath, T. A., Jackson, A., Goy, E. R., Miller, L. L., & Delorit, M. A. (2002). Experiences of Oregon nurses and social workers with hospice patients who requested assistance with suicide. The New England Journal of Medicine, 347(8), 582–588. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa020562

- Gewarges, M., Gencher, J., Rodin, G., & Addullah, N. (2020). Medical assistance in dying: A point of care educational framework for attending physicians. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 32(2), 231–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2019.1682588

- Government of Canada. (2020). What we Heard Report. A Public Consultation on Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID). Available from https://canada.justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/ad-am/wwh-cqnae/toc-tdm.html.

- Government of Quebec. (2020). Code of ethics of the members of the Ordre professionnel des travailleurs sociaux et des thérapeutes conjugaux et familiaux du Québec. Available from https://www.legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/document/cr/C-26,%20r.%20286%20/.

- Gupta, M., & Blouin, S. (2021). Ethical judgment in assessing requests for medical assistance in dying in Canada and Quebec: What can we learn from other jurisdictions? Death Studies, 46(7), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2021.1926636

- Health Canada. (2021). Second annual report on medical assistance in dying in Canada 2020. Available from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/medical-assistance-dying/annual-report-2020.html.

- Hébert, M., & Asri, M. (2022). Paradoxes, nurses’ roles and medical assistance in dying: A grounded theory. Nursing Ethics, 29(7–8), 1634–1646. https://doi.org/10.1177/09697330221109941

- Kelley, L. T., Coderre-Ball, A. M., Dalgarno, N., McKeown, S., & Egan, R. (2020). Continuing professional development for primary care providers in palliative and end-of-life care: A systematic review. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 23(8), 1104–1124. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2020.0060

- Khoshnood, N., Hopwood, M. -C., Lokuge, B., Kurahashi, A., Tobin, A., Isenberg, S., & Hussain, A. (2018). Exploring Canadian physicians’ experiences providing medical assistance in dying: A qualitative study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 56(2), 222–229.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.05.006

- Leichtentritt, R. D. (2002). Euthanasia: Israel social workers’ experience, attitudes and meanings. British Journal of Social Work, 32(4), 397–413. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/32.4.397

- Macdonald, S., LeBlanc, S., Dalgarno, N., Schultz, K., Johnston, E., Martin, M., & Zimmerman, D. (2018). Exploring family medicine preceptor and resident perceptions of medical assistance in dying and desires for education. Canadian Family Physician, 64(9), e400–406.

- Miller, L. L., Harvath, T. A., Ganzini, L., Goy, E. R., Delorit, M. A., & Jackson, A. (2004). Attitudes and experiences of Oregon hospice nurses and social workers regarding assisted suicide. Palliative Medicine, 18(8), 685–691. https://doi.org/10.1191/0269216304pm961oa

- Mills, A., Bright, K., Wortzman, R., Bean, S., & Selby, D. (2021). Medical assistance in dying and the meaning of care: Perspectives of nurses, pharmacists, and social workers. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 27(1), 60–77. Mar 8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459321996774

- National Association of Social Workers (NASW). (2021). Code of Ethics. Available from https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English.

- Norton, E. M., & Miller, P. J. (2012). What their terms of living and dying might be: Hospice social workers discuss Oregon’s death with dignity act. Journal of Social Work in End-Of- Life and Palliative Care, 8(3), 249–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/15524256.2012.708295

- Oczkowski, S. J. W., Crawshaw, D., Austin, P., Versluis, D., Kalles-Chan, G., Kekewish, M., Curran, D., Miller, P. Q., Kelly, M., Wiebe, E., Dees, M., & Frolic, A. (2021). How we can improve the quality of care for patients requesting medical assistance in dying: A qualitative study of health care providers. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 61(3), 513–521.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.08.018

- Ogden, R. D., & Young, M. G. (1998). Euthanasia and assisted suicide: A survey of registered social workers in British Columbia. British Journal of Social Work, 28(2), 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjsw.a011321

- Ogden, R. D., & Young, M. G. (2003). Washington state social workers’ attitudes toward voluntary euthanasia and assisted suicide. Social Work in Health Care, 37(2), 43–70. https://doi.org/10.1300/J010v37n02_03

- Pesut, B., Thorne, S., Storch, J., Chambaere, K., Greig, M., & Burgess, M. (2020). Riding an elephant: A qualitative study of nurses’ moral journeys in the context of medical assistance in dying (MAiD). Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(19), 3870–3881. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15427

- Quebec National Assembly. (2021). Report of the Select Committee on the Evolution of the Act respecting end-of-life care. Available from http://www.assnat.qc.ca/en/travaux-parlementaires/commissions/cssfv-42-1/index.html.

- Selby, D., Wortzman, R., Bean, S., & Mills, A. (2021). Perception of roles across the interprofessional team for delivery of medical assistance in dying. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 37(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2021.1997947

- Shaw, J., Wiebe, E., Nuhn, A., Holmes, S., Kelly, M., & Just, A. (2018). Providing medical assistance in dying: Practice perspectives. Canadian Family Physician, 64(9), e394–399.

- Variath, C., Peter, E., Cranley, L., Godkin, D., & Just, D. (2020). Relational influences on experiences with assisted dying: A scoping review. Nursing Ethics, 27(7), 1501–1516. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733020921493

- Ward, V., Freeman, S., Callander, T., & Xiong, B. (2021). Professional experiences of formal healthcare providers in the provision of medical assistance in dying (MAiD): A scoping review. Palliative & Supportive Care, 19(6), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951521000146

- Winters, J. P., Pickering, N., & Jaye, C. (2021). Because it was new: Unexpected experiences of physician providers during Canada’s early years of legal medical assistance in dying. Health Policy, 125(11), 1489–1497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.09.012