ABSTRACT

Influenced by psychoanalytic theory of drive and the desire, the surrealist movement aimed at breaking down the rational I of the individual, to liberate desire and sexuality and create a free human being by transgressing moral and social conventions. I explore the idea that sexual desire may be experienced as something foreign in us – as a drive for excess and boundlessness. Reflecting on the revolutionary project of surrealism from a psychoanalytic perspective, I specifically discuss female sexual desire as articulated by surrealist artists. I argue that art may confront us with what is foreign, thereby ‘calling’ upon us to integrate what was hitherto unrecognized.

‘Where they love they do not desire and where they desire they cannot love’ (Freud, Citation1912, p. 183). This is how Freud describes the split between love and desire.

Anders lives in a stable and safe relationship to his wife with whom he has two small children. Recently, he has felt restless and ‘fenced in.’ He does not like the boring person he feels he has become. The relationship seems more ‘dead’ and ‘dull’ than before, and secretly, Anders yearns for more excitement. One day at a job conference he encounters Anna – a beautiful, attractive younger colleague who quite directly seduces him. Anders falls in love with her immediately. For some months they engage in a passionate sexual relationship. One day Anders’ wife discovers an intimate message on her husband’s mobile phone. She is furious, tells him to leave, literally throws him out of the house. Anders is devastated. Suddenly, the passionate feelings for Anna are gone – the only thing he wants is to reunite with his wife and children. Begging his wife to take him back, Anders cries that he is ashamed that he could ‘lose control’: ”I don’t understand what happened. I was beside myself. It was as if something foreign took over. Now I’m myself again”.

This is an example from my own therapeutic practice of how desire enters the therapy room, as burning lust and desire, but also as what Anders calls something foreign. What he experiences as foreign is his sexual desire, a drive that conflicts with his need for security and belongingness. Anders was deeply attached to his wife and children; they were the very anchor of his life. Yet, his longing for passion was unfulfilled. Two different needs implying divergent pulls in Anders’ life. On the one hand the need for a safe, stable relationship, on the other hand a desire for erotic pleasure (Gullestad, Citation2020).

Why foreign – what kind of driving force is sexual desire? The surrealists found an answer – and great inspiration – in Freud’s drive theory. Let me shortly remind us of Freud’s seminal essay Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (Citation1905), which Strachey (Citation1953), in his introduction to the English translation, describes as Freud’s ‘most momentous and original contribution to human knowledge.’ Freud defines drive (Trieb) as a psychic representation of impulses and stimulations from inside – bodily needs are always mediated by the psyche, human sexuality is a psychosexuality – defined as a seeking of pleasure, a fundamental driving force in human life (the pleasure principle) expressed in countless masked and displaced forms. Freud forcefully argues against the conventional view of sexuality of his time implying that sexuality was absent in childhood and only beginning in puberty. Infantile sexuality, suggesting a ‘paradigm shift’ (Gammelgaard & Zeuthen, Citation2010) in the common view of sexuality, is obvious for everyone who wants to see, says Freud, as we observe it in the small child’s sensual sucking of her thumb, completely absorbed in an autoerotic pleasure.

Moreover, the aim of the sexual drive is not limited to sexual union and reproduction – a heteronormative view, that still has a strong hold in many religions. Indeed, Freud’s revolutionary idea was that the aim of the sexual drive is not given, but rather subject to great variation. We are all bisexual beings – and bisexual and homosexual desires as well as rude, obscene fantasies are part of human eroticism. One patient of mine got hot by sniffing his partner’s underwear, another by touching his girlfriend’s fur, reminding him of her hairy sex. What many people call perverse is part of normal sexuality. Rather, it is lack of tolerance for the perverse that leads to neurosis, Freud states (Freud, Citation1905, p. 165). The roads of desire are multifarious! Ruth Stein speaks about ‘the normative abnormality of sexuality’ (Stein, Citation2008, p. 47). When we are sexual, we confront something other in ourselves, a polymorph wildness that may be experienced as foreignness. We are reminded of the Greek Dionysian feasts that hailed drive as a pleasure-seeking force ignoring social and cultural norms. I have used the metaphor of the otherness of sexuality to capture this aspect of erotic passion (Gullestad, Citation2020) – what Anders felt as something other taking over, something that he did not acknowledge as ‘him’. Ruth Stein also speaks of otherness, understood as the experience of excess and transgression of ordinary life in eroticism. Surely a concept that may elucidate Anders’ ecstatic involvement with Anna.

The emergence of the modern view of sexuality, where pleasure and lust take precedence, is a story about ever greater liberation from given traditions, rules, and gender roles. In the center of surrealism’s vision of a new reality is the ideal of liberating sexuality and desire with the aim of creating a free human being, by transgressing moral and social conventions.

Surrealism and psychoanalysis

Before I discuss this vision, let me shortly remind you of the encounter between surrealism and psychoanalysis. What I shall present is my personal perception - and on surrealism’s ideas and works of art – I’m not a researcher in this field.

Surrealism came into existence in the wake of the First World War, which had left Europe in ruins and caused millions of deaths. André Breton, the pioneering figure of the surrealist movement, met with Freud’s work in 1916 – he felt that Freud revealed groundbreaking insights into the human mind. Breton had worked at a psychiatric center for psychotic patients – a work that fascinated him – and thought that psychoanalysis might help him understand the irrationality and wildness of the psychotic mind. Breton developed the idea of psychic automatism – aiming at expressing the actual functioning of thought, in the absence of control by reason, free from aesthetic and moral concern. Through automatic writing, he argued, one would get access to a superior reality (sur-réel), more ‘real’ than ordinary reality, characterized by the omnipotence of dreams (Breton, Citation1924). However, Breton’s romance with Freud was one-sided. Once, he succeeded in meeting his great idol, he managed to get an appointment at Berggasse in October 1921 but was immensely disappointed. The meeting was short, Freud was not interested. Later, in 1937, Freud refused to collaborate with Breton on his 1938 book Trajectoire du rêve. Freud declared: ‘A mere collection of dreams without the dreamer’s associations, without knowledge of the circumstances in which they occurred, tells me nothing and I can hardly imagine what it could tell anyone’ (Freud, quoted in Gombrich 1954). It was ‘wonderful to be designed as Patron Saint of surrealism’, Freud said, but added: ‘I don’t really understand … I’m at such a distant position from art’. In France, however, Jacques Lacan, was inspired by surrealism, published in their journals and for a period was part of the surrealist circuit in Paris (Esman, Citation2011). And in literature about surrealism, Lacan is referred to as a most important figure, a defender of fantasy and the irrational (Fløgstad et al., Citation1980). I will come back to this. But in general, the relation between psychoanalysis and surrealism has been of greater interest to art historians than to psychoanalysts (Esman, Citation2011, p. 173).

Breton’s main idea was that artists, by surrendering to the unconscious – dreams, desire, irrational impulses – should pave the way for a radically new world order. In the nineteen twenties and -thirties he attracted a diverse group of poets, painters and filmmakers that confronted conventional morals, tradition, and rationality. Among them were Max Ernst, Dora Maar, René Magritte, Leonora Carrington, Salvador Dali, Louis Bunuel, Hans Bellmer and Unica Zürn. The surrealist movement played a dominant role in art and culture in the Western world for at least a generation between the wars.

Confronting the foreign

This winter, a new Munch-museum celebrating the work of the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch, opened in Oslo. The opening exhibition, titled The savage eye, was a broad presentation of surrealist art and thinking at the same time bringing together central ideas in surrealism, symbolism and Edvard Munch’s work. On the occasion of this first exhibition by the new museum – a great cultural event – Norwegian psychoanalytic society was invited to collaborate by giving public lectures on the theme of the exhibition. A great honor, of course, for the outreach of psychoanalysis in our small country! Certainly, the obvious reason was surrealists’ pronounced celebration of what they considered key psychoanalytic ideas. This article is based on my contribution to these public lectures. One of the exhibition rooms of The savage eye was titled ‘haunted identities’. ‘Who am I’? André Breton begins his fictional novel Nadja with this question. The question is answered by the poet Arthur Rimbaud (1854–1891) – the brilliant precursor of surrealism and the first modern poet, says the famous Norwegian author Kjartan Fløgstad, with titles like Le bateau ivre (A drunken boat båt) and Une saison en enfer (A season in hell). The answer to Bréton’s question «who am I» is that – «Je est un autre» («I am another», with the verb in third person), says Rimbaud (Rimbaud et al., Citation2004). He articulates a radical critique of traditional poetry and advances a new poetics. The poet must become a seer, a clairvoyant – he must use his ‘inner eye’ to capture the inner images of the soul. We find the same thought by Edvard Munch. The artist must reject realistic depictions of the surrounding world in favor of exploring the inner life of the soul – this idea was central to the broad cultural movement called symbolism (with names like Rimbaud, Gauguin, Rodin, Strindberg, Munch), a precursor of surrealism. The aim of art was to express the ideas behind visible reality. The poet touches a tone, says Rimbaud, thereafter the poem follows it’s own course: ‘It is wrong to say “I think”. Someone thinks me’. When «Je est un autre», the ‘I’ is not stable and constant, but rather fluid, fragmented and even in a sense self-alienated. The same thought as articulated in Freud’s ‘the ego is not master in its own house’, and later in Jacques Lacan’s idea of something speaking in me, ‘from another place’. The poet and the psychoanalyst approach the same experience from different perspectives. Certainly, a possibility for a mutual, fruitful dialogue.

I have, so far, talked about the experience of not knowing oneself and I have highlighted the otherness of sexuality – the feeling of foreignness. Yet, and this is the idea I want to explore in this article, drives are not only foreign will. Erotic desire brings me in contact with a vitally important part of myself, what I may experience as the very core of my being. What I sense as unknown are also impulses and feelings that I want to get to know, yes, that I wish to make part of what I experience as me. This is the liberation project of psychoanalysis on an individual level, a process of confronting the foreign. Psychoanalytic treatment offers what the philosopher Jürgen Habermas (Citation1969) called an emancipatory knowledge. Surrealists had a parallel project of emancipation on a cultural level. They wanted to liberate desire and sexuality and create a free human being by transgressing moral and social conventions. Let me specify by exploring the question of female desire.

Female desire

Surrealism honored the revolution of unconscious drives and desire and greeted the idea of a free, emancipated human being. However, as emphasized by The savage eye-exhibition, most surrealists were heterosexual men who prioritized their own needs and impulses. Women were first and foremost treated as objects of desire, not as individuals with their own sexuality. In an essay about the female surrealist artist Leonora Carrington, the Danish-Norwegian literary critic Susanne Christensen (Citation2019) explores this idea. There was an artistic-pornographic goddess cult in the surrealist movement, says Christensen. The male surrealists were hypnotized by femaleness. The woman was an inspiring muse, in her essence the woman was closer to the unconscious, closer to nature. Being a portal to man’s inner unconscious, the female, and especially the young female, la femme-enfant (the child-woman/barnekvinnen), has a role of medium, muse and metaphor (Toft Eriksen, Citation2022) – the enigmatic other of the male genius. Surrealism also fetiches so called primitive people – these are original, spontaneous, maybe more childlike, and closer to nature. Breton enthusiastically describes Mexico as the most surrealistic country in the world! The white man’s look – a missionary, colonial look, I will say, a Western look that constitutes the ‘oriental’ as something alien, as Edvard Said (Citation1978) describes it in Orientalism.

But not only. Female sexuality also has something transgressive, André Breton thought. He acclaimed Munch’s depiction of female desire as it was expressed in Munch’s short story

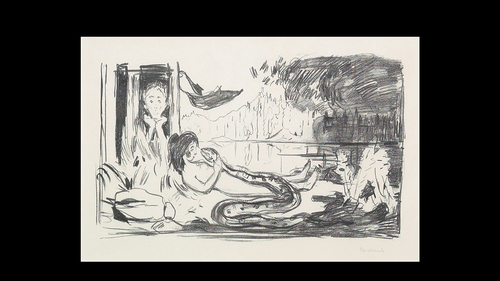

Alpha and Omega, that Breton published in his journal Medium. Munch portrays Omega’s desire in the following way (picture 1)

«Alpha called upon Omega, but Omega did not hear him. Then Alpha saw that Omega held a snake’s head in her hands and stared into its shining eyes, a big snake that came from the snake nest and meandered around her body. (…) Once she meets with a bear. Omega shivered when she felt the bears soft fur against her body. Then she put her arm around its neck, sank into the soft fur” (Munch, Citation1908–09).

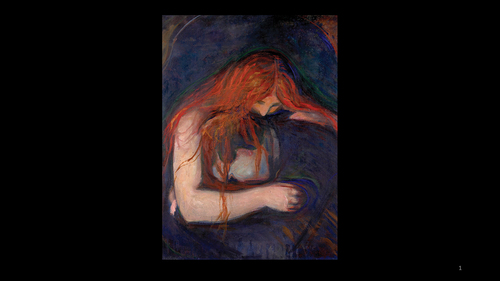

Omega is a woman in possession of her own desire, like the princess in the Norwegian fairy tale Kvitebjørn kong Valemon. ‘Did you ever sit softer; did you ever see clearer?’ asks the white bear. ‘No, never’, answers the princess (Asbjørnsen & Moe, Citation1978). Omega in Munch’s short story and the princess, both embrace the raw, animalistic in their own sexuality. For sure, such a woman may be experienced like aggressive and challenging for a traditional masculine man who demands that the woman subordinates herself. And Alpha remains lonely while Omega unfolds her desire. The story does not have a happy ending. I grew up with Munch’s Vampyre on the wall (picture 2). The woman bows down over the man’s neck. Is she sucking life out of him? A picture of the male anxiety encountering female power?

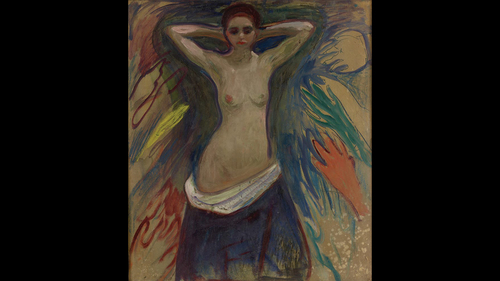

Let’s move from Alpha and Omega to Edvard Munch’s Hendene (The hands, picture 3) Hands that stretches towards the woman’s body, hands that desire, men’s hands. A woman closing her eyes, coming forward, enjoying and lustful she welcomes man’s desire. The painting captures the double sidedness of desire: to desire, to be desired, to desire to be desired. A transgressive painting, in my experience, representing female eros, the need for surrender, for excess, for boundlessness. – Munch’s painting anticipates the female surrealists. They existed, even if they were ignored for a long time. The savage eye brought them forward, like Louisiana’s exhibition Fantastiske kvinner, in 2021.

As a muse, the woman is separated from her own agency, says Susanne Christensen: she is a screen for emotional and aesthetic projections rather than being center of her own actions, doomed to observe herself from the outside. Or – is this so, Christensen asks. Maybe the task of a muse is also to walk across a white male body with sharp stiletto heels? And this is how she presents Leonora Carrington. Carrington’s short story titled The debutante (in La dame ovale, Carrington, Citation1939) is a surrealistic description of a fantasized debut in social life: Leonora is friend with a hyena in the zoo, and persuades the hyena to take her place at the dinner dance her mother gives to honor her. Leonora hates dinner dances, in the story as well as in real life. To avoid being recognized, the hyena must first eat the servant and take on her face. Of course, it ends in scandal – the hyena goes to the table with the words: ‘I smell a bit strong, don’t I? Well, I don’t eat cookies’. With these words she tore off her face and ate it. A gigantic jump out of the window, and the hyena disappeared. The story conveys Leonora Carrington’s ingrained rage and vehement rebellion against the English upper class she was born into. A liberating rage! We sense the same kind of rage in Louise Bourgeois’ sculpture Pair of knives (picture 4) – knives as weapons, signaling that women must fight to be free. According to Bourgeois, who was in psychoanalysis for many years, her family viewed her brothers’ protest and fury as completely normal – ‘that’s how boys are’. If she was angry, however, something was wrong with her. ‘It does not suit you to be angry’, as one of my patients was told as a child. Women must access their own aggression, this is the surrealist artist Louise Bourgeois’ contribution to psychoanalysis, says Juliet Mitchell (Larratt-Smith & Mitchell, Citation2021).

I’m struck by the way in which the female surrealist artists confront myths about women.

Leonora Carrington’s self-portrait in riding pants with a hyena at her side (picture 5): It’s as if she ridicules her male colleagues’ celebration of women as nature. For Leonora, nature represents freedom, the opposite of bourgeois narrow-mindedness. Woman and animal in alliance – in a deep sense Leonora embraces desire as a force of nature beyond rational control, thus transcending the constricted gender roles of her time. The painting pictures a white horse, wildly galloping, a flight towards freedom. «I’m a mare», Leonora says to her father. «Yes, you’re a nightmare», answers her father. Leonora departs for Paris with her lover Max Ernst.

Meret Oppenheim’s Le déjeuner en fourrure (Breakfast in fur) – a teacup dressed in fur – is also mocking (picture 6). Oppenheim was called the fairytale princess of surrealism. Le déjeuner en fourrure from 1936 – evoking associations to the female sex and oral sexual pleasure – has remained one of modernism’s iconic pictures, instantly bought by MOMA. A woman painter who herself owns the representation of erotic lust and desire. Lee Miller, another female surrealist artist through her photographs seems to attempt to regain control over the female body and confront the oppressive gender politics of that time. By serving the viewer a severed breast on a plate she exposes the male look at women. As a subject, she challenges the objectification of the female body, thus reclaiming ownership of her sexuality. Hence, the female artists in the surrealistic movement, in different ways, stood up for themselves, using their own feminist language. What had been something foreign in traditional culture – female desire – was brought forward, it became represented, symbolized, allowing for an integration in our cultural self-understanding. Exhibitions like The savage eye are to be honored for promoting previously silenced female surrealists.

Sexual liberation?

What is the standing today of the surrealist idea of liberation of sexuality – of revolutionary desire? As we know, in this sense Freud, was no revolutionary. In line with romanticism, a dominant philosophical trend of the 19th century, as expressed by e.g., Schopenhauer, Freud emphasized the in-built conflict between drive and civilization, between nature and culture – sexual drive was explosive and uncontrollable and could threaten social and moral order. Many of us reading Freud in the seventies had a different view. Where Freud talked about an essential opposition between nature and culture, the German philosopher Herbert Marcuse (Citation1955) claimed that this opposition is not universal. It is the capitalist, patriarchal society that is repressive, not culture as such. Marcuse was our man! The motto of the flower power generation – their future utopia – was a liberated eros. ‘Love is in the air’ was the tune of the time. My generation regarded the sexual revolution of the sixties and seventies as liberating, playful and healthy. With birth control pills in our handbags, we women now should walk freely into the world, owning and expressing our desire!

I remember well my encounter with surrealist art when I first came to Paris in 1968. I was fascinated. Indeed, the liberated eros was the project of surrealism, as it was for many of us in the 1968-generation. Certainly, it may be argued that this vision relied on a a naïve idea of liberation. As the surrealists realized, desire also contains dark energies. Compte de Lautréamont, with Les Chants de Moldoror (Citation1868) was one of their ‘heroes’ – Moldoror being an evil anti-hero. Another of their idols was Marquis de Sade, honoring the expression of in-built primitive, sadistic impulses. This dark vision of eroticism is also conveyed in their art, as the violence pictured in the drawings of the female surrealist artist Unica Zürn (picture 7). Sølvi Kristiansen (Citation2022), in a recent analysis of Unica Zürn, demonstrates how in Zürn’s life sexuality was interwoven with aggression turned against the self, leading to fragmentation. Zürn’s partner, the surrealist artist Hans Bellmer, in his iconic installation Die Puppe (The doll), pictures such fragmentation, which is theoretically captured in Lacan’s concept le corps morcelé (the fragmented body). Indeed, a hundred years after the heyday of surrealism in the nineteen twenties, we know a lot about the opaque energies of erotic desire – as the actions of the pedophile that are now openly disclosed to the public, sexual actions blindly directed by horniness, deprived of empathy for other people’s feelings – the destructive egocentricity of drives. Indeed, desire can be unruly and destructive.

Also, many among the flower power children now looking back at their vision of ‘free love’ will say that, after all, it wasn’t that easy. Leonard Cohen, in this context a talesman for the 68 revolutions, praised himself for living in a time where sex was free – this rare moment in history, as Cohen calls it, where it was possible to express friendship sexually, permitting both men and women to satisfy their sexual appetite, and where no one should have property rights over another human being. However, as it turned out, for many people such sexual freedom came into conflict with jealousy and the wish for an exclusive relationship, it could clash with the wish for being the chosen one as well as with the basic need for attachment. Consequently, not only moral demands and conservative norms hinder unbound lust. Other emotional needs, like the need for belongingness, may create conflict. It is this kind of conflict we face in our therapy rooms, as in Anders’ account of a marriage being torn apart. In my encounter with young patients, they may relate that having sex is easy. What is difficult, some of them tell, is to feel – that they want to be the only one, that they feel jealous and that they long for attachment. Such feelings create shame.

What, then, can we make of Breton’s idea of ‘revolutionary desire’? I will approach the question by highlighting Lacan’s theory of desire. As I said, Lacan and the surrealists socialized, they referred to each other and Lacan at one point consulted Salvador Dali, to better understand Dali’s theory of the paranoic – a mode of perception that both Dali and Lacan conceived of as constituted by desire (Bergesen, Citation2010).Footnote1 In line with Breton,Footnote2 Lacan was fascinated by the psychotic state of mind ,Footnote3 and wanted to understand the structure of the ‘language’ of the psychotic. Moreover, Lacan and the surrealists shared a common frame of reference in propagating what has been called the ‘French Freud’ (Turkle, Citation1982) – a psychoanalysis in dialogue with the intellectual, artistic avantgarde (in contrast to America).

It seems that for Lacan, surrealism was primarily an attitude and a social praxis – like the surrealists he was critical of the existing social and political order, wanting to transcend the conservative, bourgeois, catholic culture. ‘Don’t compromise with your desire’, Lacan wrote, because ‘desire is a spear’. Desire should be the motor of a releasing uprising! Later, Lacan was to develop a far more complex concept of desire – a concept that I think contribute to nuance our discussion.

In a previous paper, I have explored how the psychoanalytic drive theories of Freud, Laplanche and Lacan elucidate the conflicted nature of desire and object choice (Gullestad, Citation2020). Here, I will try to give a short account of some major points. Lacan (Citation1966, Citation1973), based on reflection on the early mother – child relationship, introduces a distinction between drive and desire. While the drive ‘circulates,’ so to say, independent of the object, desire is directed towards another subject, towards a specific person. Here, there is no longer a question of pure satisfaction, but of what we mean to the other person. Desire implies a vulnerable position, surrendered to the other. In desire, there is a lack – man’s desire is the desire of the other. When our conscious wishes are gratified, there is still ‘something’ that leaves us dissatisfied. It is this something that Lacan designates as desire. It is linked to a quest for a thing beyond representation, something that is not verbalized or symbolized – the lost yet unforgettable object that continuously must be re-found – the forbidden object of incestuous desire, the mother. In fantasy, this ‘something’ implies the ultimate pleasure, which Lacan calls jouissance—a pleasure transcending the pleasure principle, and that expresses a longing for the impossible and forbidden. Realization of this kind of pleasure would be intolerable and dangerous – desire can have fatal repercussions. Thus, jouissance represents a pleasure that cannot be symbolized (Lacan, Citation1973; Stein, Citation2008). Fantasy, for Lacan, is what fills out the empty and insurmountable space between the subject and the object of desire, says Judy Gammelgaard and Sølvi Kristiansen in a study of unconscious fantasy (Citation2017).

Thus, while the object of the drive is shifting, love has its origin in the early mother – child relationship. In Lacan’s perspective, this relationship is ‘total’ in the sense that the other is for me and just for me – it is ‘total’ in the sense of absence of lack. However, because it is a relationship where individuality is suspended, it is misleading to speak about a relationship. As humans, we start life in an undifferentiated form, in a union with the other. Splitting of this union creates desire implying a search – not for the lost object, but for the lost union. Hence, the little child’s pursuit of the mother suggests a desire that can never be satisfied – a quest for a union that is irretrievably lost, but that we long for from the cradle to the grave. Love thus originates in the first relationships – forever lost and eternally desired. When we are attracted to each other, we are often blind to the fact that what we wish for is not what we desire. Therefore, we are often disappointed when we have what we wish for.

Let me further highlight the question of liberation of desire by returning to the concept of ‘otherness’. I started with highlighting the otherness of sexuality both as feeling of something other, or alien, in us, as well at otherness understood as an experience of ecstatic transgression and excess. To my mind, a concept of otherness is also implied in Lacan’s concept of desire, underscoring how sexual desire has a soundboard in archaic fantasies that cannot be satisfied through real objects. Another aspect of ‘otherness’ is elaborated by Jean Laplanche, in his radical exploration of the origin of drive and sexuality. Laplanche (Citation1970, Citation1997) characterizes Western philosophy as a way of thinking that does not recognize the ‘otherness’ of the other. Although Freud discovered the otherness of the unconscious (das Andere), psychoanalysis has yet to acknowledge that internal otherness is founded upon external otherness (der Andere) (Laplanche, Citation1997, p. 654). While both Freud (Citation1905, p. 120) and Laplanche emphasize that mother is the first seducer, and that the fantasies coloring the individual’s sexual desires and dreams are fundamentally marked by the mother, Laplanche in strong terms refers to the mother’s unconscious transmission of her sexuality to her baby. Through the interplay with the child, the mother puts a ‘mark’ on it. Her interaction with the child is imbued by her sexual unconscious, thus the mother is ‘seducing’ her child. The child will, according to Laplanche, experience mother’s sexuality as enigmatic messages. With a metaphor, mother carries a Mona Lisa smile, exciting and vaguely attracting, which can only be interpreted nachträglich. The sexual messages remain partly un-symbolized and persist in the child as an element of irreducible otherness. Thus, the child’s sexuality is established through the unconscious, fantasized sexuality of the other. It is the mother that introduces the child to the language of desire.

In line with Freud, Laplanche underscores the plasticity of human sexual drive. Sexuality is anarchique (anarchistic), says Laplanche (Citation2007, p. 6), and exceedingly more wide-ranging than genital drive aiming at reproduction; it is mobile as to its aim and its objects, and it reaches beyond sexual differences. Certainly, it is psychosexuality, related to and mediated by fantasy, which Laplanche in his last works calls le sexual (Laplanche, Citation2007).

Thus, Freud, Laplanche and Lacan, although in different ways, all convey an idea of sexuality’s otherness: Experiences of the erotic drive as strange otherness; desires for the impossible and forbidden object; fantasies that exceed concretely lived life, creating a feeling of non-fulfilment – in Lacan’s terms, we are characterized by a lack. Sexuality and love are not necessarily integrated, we are split creatures, the dance of love is challenging. I’m inspired by a distinction that Michel Foucault develops in his study of how the early Christian church fathers reflected on sin, sexuality, penance, and confession published as a last volume of Histoire de la sexualité (Foucault, Citation2018, published after his death), called Les aveux de la chair, (Confessions of the flesh). Foucault here differentiates between le corps (the body) and la chair (the flesh). La chair confesses an idea of unappeasable desire that is transcending in relation to the body. Hence, a way of thinking that does not reduce sex to the body.

So, in what sense, if in any sense, can we speak of liberation of sexuality and desire? To my mind, the idea of otherness is liberating, in the sense that it conveys acceptance of something incomprehensible. It is something in ourselves that we do not fully grasp. In a discussion of queer theory and dis-identification from heterosexuality and the constraints it imposes, Alice Kuzniar (Citation2017) emphasizes Laplanche’s notion of enigmatic sexuality. Sensitivity to this enigma entails a sense of openness to das Andere, the internal otherness that we perpetually carry within us and that de-center us, but that is founded by contact with an external otherness. The notion of enigma may, according to Kuzniar, pave the way for a more gender-variable identifications and introjections ‘that occur queerly or across any clear dividing line between homosexuality and heterosexuality or female and male’ (2017, 63). As the internal ‘other’ is founded on the external ‘other’, this idea of otherness allows for cultural critique. Speaking clinically, Laplanche’s theory sensitizes us to understandthat the way the mother, always culturally situated, touches her baby – how she rocks and sniffs, her skin and warmth – will transmit her own sensuality to the child. Indeed, if mother’s erotic investment in the child’s body is lacking, the child will be hindered in developing bodily pleasure and in experiencing her own desire in its phantasmatic and symbolic dimension (Gullestad, Citation2020; K. Gammelgaard & Zeuthen, Citation2010; Laplanche, Citation1997). Openness to the incomprehensibility and enigma of sexuality is, to recall Laplanche, the source of creativity.

Surrealist art pictures the roads of pleasure as multifarious, and they portray sex and gender as fluid – these certainly are liberating ideas. Erotic desire expresses life energy, emerging despite tight social rules, and transcending conventional morals, permitting a more authentic existence. I want to honor the female surrealist artists for transgressing the role of being muse and objects of male desire in favor of expressing their own eroticism and creativity!

Life and art

I will end by reflecting on the relationship between life and art, from a personal perspective. The center of surrealism was Paris. Breton’s Manifeste du surréalisme was published in 1924. Forty years earlier, in 1885, Freud came to Paris to study with Jean Martin Charcot. Freud developed an intense transference, not only to Charcot, the master, but to the city of Paris, Joel Whitebook maintains, in Freud. An intellectual biography from 2017. In letters to his fiancée Martha, Freud describes the city as ‘magically attractive and repulsive’ – as ‘one long confused dream’. Freud is struck by something unheimlich – uncanny. Paris is, he says, like a ‘wanton, female temptress’ (2017, 112). At this time psychology as an experimental science was born in Germany, in the laboratory of Wilhelm Wundt. Through the study of the senses, how we perceive the world, questions that philosophers had struggled with for centuries, the soul was brought into the laboratory. In Paris a different kind of psychology emerged, la psychologie nouvelle. Interest was directed toward phenomena like somnambulism, human automatisms, multiple personality, double consciousness, as well as demonic possessions, fugue states and waking dreams. Charcot was famous for the soirées that he threw in his mansion on the Boulevard Saint-Germain. Le tout Paris – the social, intellectual, and political elites of the city were there. Freud wrote to Martha that he found these soirées so intimidating that he had to fortify himself before attending them with a dose of cocaine, to lessen the anxiety and ‘untie (his) tongue’ (Whitebook, Citation2017, p. 116).

About forty years after the surrealists, I came to Paris, in 1968, eigtheen years old, during la revolution du Mai. Undoubtedly, I was also a bit frightened. Encountering the foreign that Paris represented for a girl from a village outside Oslo was groundbreaking, a game changer. On the streets of Paris, I bought Wilhelm Reich’s La function de l’orgasme (The function of the orgasm) (Citation1927) and La révolution sexuelle (The sexual revolution) (Citation1936) (as well as L’érotisme (Citation1957b) and La littérature et le mal (Citation1957a) by Georges Bataille and Breton’s Manifestes du surréalisme (Citation1924). These were texts that permitted confrontation with the foreign in myself. Meeting with art may be transformative, in a deep sense life expanding. For me, the encounter with Paris embodied affirmation of something I did not know was me, that was foreign, yet was me. Art and literature may create new experiences, thereby new ways of living. A liberation of repressed vitality.

Does art imitate life, or is it the case, as Oscar Wilde suggested, that to a great extent life imitates art? In this case, art is viewed as the creation of different ways of constructing experience, and thus as the maker of new modes of living. Discussing empathizing in the analytic situation Roy Schafer (Citation1983) argues that the analyst in a similar way contributes to widen the image the analysand has of herself, empathy is not just imitative. The analyst so to say holds up a picture of what the analysand can become, thus contributing to create in the person of the analysand someone who has never quite existed before, to new manners of conceiving of self and others. Analytic listening is in this sense constitutive of new experience – analytic listening is creative; it has a transformational aspect. Schafer relates a short history told about Picasso. When at first told that his now celebrated portrait of Gertrude Stein did not resemble her at all, Picasso replied simply – and according to Schafer, with enviable confidence – ‘It will’ (Schafer, Citation1983, p. 56).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Siri Erika Gullestad

Siri Erika Gullestad, Dr. philos.,Professor emeritus of clinical psychology, University of Oslo. Training and supervising analyst, IPA. Gullestad is former Head of Department of the Department of psychology and former president of the Norwegian Psychoanalytic Association. Currently Chair of Research Committee, IPA. Author of many articles and books within the psychoanalytic field, e.g. Theory and practice of psychoanalytic therapy. Listening for the subtext. Routledge, 2020 (with Bjørn Killingmo); The otherness of sexuality: Exploring the conflicted nature of drive, desire and object choice, Int J Psychoanal, 2020. Gullestad was awarded the Sigourney prize 2019.

Notes

1. The paranoic refers to the emergence of the object as an active process of perception of the surrounding world, as opposed to the rather passive process connoted by the concept of automatism. Certainly, an important epistemological discussion that I will not go into further here.

2. Breton and his colleagues, wanting to demonstrate the thin line between normality and madness, had experimented with simulating psychotic episodes, expressed through automatic writing. To my mind this amounts to a kind of ideological idealization of madness, that ignored the pain and chaotic destructiveness of the psychotic state of mind.

3. Lacan’s doctoral dissertation was an in-depth study of Aimée, a psychotic patient he treated for one and a half year. Through his case studies, he demonstrated the family- and social dynamics determining the psychotic states of mind, thus arguing that patients are ill from culture, not nature. By rending psychosis understandable, the early Lacan contributed to humanization of psychiatric illness, important in the society at that time.

References

- Asbjørnsen, P. C., & Moe, J. (1978). Norske folkeeventyr. Gyldendal.

- Bataille, G. (1957a). La littérature et le mal. Éditions Gallimard.

- Bataille, G. (1957b). L’érotisme. Union Générale d’Éditions. 10/18.

- Bergesen, L. (2010). Jacques Lacan i lys av surrealismen – et bidrag til «bildet av Lacan». Masteroppgave, Universitetet i Oslo.

- Breton, A. (1924). Manifestes du surréalisme. Gallimard.

- Carrington, L. (1939). La dame ovale. Paris: Guy Lévis Mano.

- Christensen, S. (2019). Leonoras reise. Oktober.

- Esman, A. H. (2011). Psychoanalysis and surrealism: André Breton and Sigmund Freud. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 59(1), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003065111403146

- Fløgstad, K., Gundersen, K., Heggelund, K., & Lie, S. (1980). Surrealisme. En antologi. Gyldendal.

- Foucault, M. (2018). Les aveux de la chair. Gallimard.

- Freud, S. (1905). Three essays on the theory of sexuality. SE, 7, 135–244.

- Freud, S. (1912). On the universal tendency to debasement in the sphere of love. SE, 11, 65–177.

- Gammelgaard, J., & Kristiansen, S. (2017). The screen function of unconscious fantasy. Scandinavian Psychoanalytic Review, 40(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/01062301.2017.1354495

- Gammelgaard, K., & Zeuthen, J. (2010). Infantile sexuality—the concept, its history and place in contemporary psychoanalysis. Scandinavian Psychoanalytic Review, 33(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/01062301.2010.10592849

- Gullestad, S. E. (2020). The otherness of sexuality: Exploring the conflicted nature of drive, desire and object choice. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 101(1), 64–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207578.2019.1686390

- Habermas, J. (1969). Erkenntnis und Interesse. Suhrkamp.

- Kristiansen, S. (2022). Når jeget slår sprekker. Om unica zürn. (Cracking up. Unica Zürn’s autobiographical writings). Unpublished manuscript.

- Kuzniar, A. K. (2017). Precarious sexualities: Queer challenges to psychoanalytic and social identity categorization. In N. Giffney & E. Watson (Eds.), Clinical encounters in sexuality. Psychoanalytic practice and queer theory (pp. 63). Punctum books.

- Lacan, J. (1966). Écrits. Éditions du Seuil.

- Lacan, J. (1973). Le Séminaire de Jacques Lacan, Livre XI, “Les quatres concepts fondamentaux de la psychanalyse. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

- Laplanche, J. (1970). Vie et mort en psychanalyse. Flammarion.

- Laplanche, J. (1997). The theory of seduction and the problem of the other. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 78 (Pt 4), 653–666.

- Laplanche, J. (2007). Sexual. La sexualité élargie au sens freudien. Presses Universitaires de France.

- Larratt-Smith P., & Mitchell, J. (2021). Louise Bourgeois, Freud’s daughter. New Books in Psychoanalysis, Podcast.

- Lautréamont, C. D. (1868). Les chants de Moldoror. Gustave Balitout, Questroy et Cie.

- Marcuse, H. (1955). Eros and civilization. Vintage.

- Munch, E. (1908-09). Alpha og Omega. Edvard Munchs tekster. Muchmuseets arkiv.

- Reich, W. (1927). La fonction de l’orgasme. L’Arche Editeur. 1952 (Trans.from English).

- Reich, W. (1936). La révolution sexuelle. Librairie Plon. 1968 (Trans.from English).

- Rimbaud, A., Fowlie, W., & Whidden, S. (2004). Selected poems and letters. Penguin Classics. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226719788.001.0001

- Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. Vintage. 1979.

- Schafer, R. (1983). The analytic attitude. Basic books.

- Stein, R. (2008). The otherness of sexuality: Excess. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 56(1), 43–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003065108315540

- Strachey, J. (1953). Editor’s note. “Three essays on the theory of sexuality”. SE, 7, 126.

- Toft Eriksen, L. (2022). I villskapens øye. Utstillingskatalog. Munchmuseet. (red).

- Turkle, S. (1982). La France freudienne. Grasset.

- Whitebook, J. (2017). Freud – an intellectual biography. Cambridge University Press.