Abstract

While understanding interest group systems remains crucial to understanding the functioning of advanced democracies, the study of interest groups remains a somewhat niche field within political science. Nevertheless, during the last 15 years, the academic interest in group politics has grown and we reflect on the state of the current literature. The main objective is to take stock, consider the main empirical and theoretical/conceptual achievements, but most importantly, to reflect upon potential fertile future research avenues. In our view interest group studies would be reinvigorated and would benefit from being reintegrated within the broader field of political science, and more particularly, the comparative study of government.

The study of interest group politics – that is the organisation, aggregation, articulation, and intermediation of societal interests that seek to shape public policies – is a relatively small field within political science. There is no special journal devoted to interest group studies, and mainstream political science journals publish less on interest groups than they do on other areas of political science such as electoral, legislative, and party politics.Footnote1 This phenomenon is not due to interest group scholarship being less advanced or less sophisticated than the other sub-fields. It is largely an artefact of size: fewer scholars work in the group area than in party politics or policy studies. There are also more substantive reasons for the paucity of interest group research: several conceptual, methodological and disciplinary barriers militate against the accumulation of knowledge.

Nevertheless, during the last 15 years, the academic interest in group politics has grown. This is evidenced by numerous empirical studies – qualitative and quantitative – within the fields of European Union studies, comparative European politics, and American politics. In recent years, the American research community has become more diverse. It has largely moved beyond the Olsonian collective action paradigm, and there has been a growth in the importance of large-scale empirical research projects (e.g. some of the studies reviewed in Baumgartner and Leech Citation1998 as well as the Advocacy and Public Policy Project; http://lobby.la.psu.edu/). In Europe, scholars have advanced from the initial focus on descriptive case studies that were often tied to the study of European integration as a sui generic phenomenon to more systematic comparative or quantitative analyses. In addition to this, the traditional pluralist versus corporatist debate that dominated the literature for many years is much less prevalent today. European scholarship on interest groups has become more empirical, systematic and draws increasingly on sophisticated methodological techniques and consistent theoretical approaches (see the contributions in Coen Citation2007).

This volume explores the accomplishments of the interest group literature, the explanatory factors for its persistent niche status and highlights potential avenues for future research. The intellectual datum here is that understanding interest group systems remains crucial to understanding the functioning of advanced democracies, especially in an era when these democracies are becoming increasingly embedded in supranational policy networks. The pluralist argument that without groups there would be no democracy retains much plausibility, which is why it finds such resonance in the social capital research industry (Putnam Citation2000). Partly due to the transformation of the European nation state, the importance of electoral and party politics appears to be in decline (Bartolini Citation2005; Mair Citation2006) and the ‘authoritative allocation of values’ seems to migrate into policy networks (Van Waarden Citation1992; Falkner Citation2000) and negotiation systems (Mayntz and Scharpf Citation1995) in which interest groups assume prominent positions.

Accordingly, this is an apposite time for an in-depth reflection on conceptual, theoretical, methodological and normative issues related to the study of political interests in the European Union and elsewhere. This sustained reflection will connect some classic insights that still – often implicitly – inform current empirical work with more recent approaches. The aim of this volume is to contribute to the laying of a sound theoretical, conceptual and methodological basis for future research. Without such a foundation we run the risk of heroic empiricism. Moreover, the field is relatively fragmented and the integration and exchange among various strands of research can contribute to a more robust and consistent research agenda. It is not a rare occurrence to see similar research being carried out under different labels. There are various, and sometimes unconnected, research niches at the European domestic and EU levels, in American politics and at the international level. Research on interest groups is conducted among sociologists, economists, and in various branches of political science – industrial relations, social movement research, etc. Regrettably communication and intellectual exchange has not been at a premium. Accordingly, the study of interest groups needs to be reinvigorated and reintegrated within the broader field of political science, and more particularly the comparative study of government.

Interest group scholars often focus on the process of group formation. However, the interaction between governments, political parties, and interest groups, as well as the potential impact or influence of interest groups on policy outcomes, has been somewhat neglected. Recent scholarship has begun to address this deficit. Nevertheless, contemporary comparative politics remains largely focused on the formal aspects of the input side of government – i.e. elections, parties, parliament, legislative, and executive politics, while ignoring the role groups play in the agenda-setting, policy design, and implementation stages of the policy-making process. This volume brings together a number of scholars who have studied these aspects of interest group systems at the national and transnational level.

In the last 20 years, the study of EU interest groups has been indebted to the more general literature on interest groups – EU scholars have been net importers of approaches, conceptualisations and methodologies developed in other fields. But in the last decade concepts such as multi-level governance and Europeanisation have fed back into the comparative study of domestic politics, and EU interest group research has been increasingly linked to the general comparative study of interest groups. Hence, the study of EU interest group politics is no longer considered to be esoteric or idiosyncratic. On the contrary, it now contributes to the mainstream political science literature. Inevitably, however, future theoretical and empirical work will only improve through further intellectual exchanges between scholars working in different areas and various interest group niches. Comparison of the EU, as well as European interest groups, with other systems is not only relevant from an EU/European perspective. It will also contribute to a deeper understanding of existing theories and of the extent to which they are applicable in multiple settings.

The remainder of this introduction outlines why interest groups politics – despite being a significant subject matter of political science – is often under-researched. The discussion is related to the changing nature of government in Europe in the context of European integration and globalisation – two phenomena that have contributed to the segmentation of politics as well as to the growing importance of interest groups. In spite of this it is clear that the general study of interest group politics remains characterised by what Baumgartner and Leech (Citation1998) labelled ‘elegant irrelevance’. There are several explanatory factors for this irrelevance. The complexity involved in defining the ‘interest group’ concept constrains the development of adequate research designs. There is also a tendency to focus on a limited number of – sometimes easier to investigate – research questions. Finally, the field is Balkanised into different research niches. After discussing these aspects, we outline three major areas for future research that might help overcome the current state of affairs. First, we discuss the question of biased political representation. Second, we analyse the effects of political cleavages on interest groups and political parties. Thirdly, we scrutinise the relationship between organisational maintenance and the influence strategies developed by interest groups. We conclude with a brief overview of the contributions to this volume.

Defining Interest Groups: Why are Definitions Important?

Interest Groups and Interest Organisations

A major problem that plagues the field of interest group studies is an abundance of neologisms: e.g. interest groups, political interest groups, interest associations, interest organisations, organised interests, pressure groups, specific interests, special interest groups, citizen groups, public interest groups, non-governmental organisations, social movement organisations, and civil society organisations.Footnote2 As Jordan and Maloney (Citation2007: 26–7; see also Cammisa Citation1995: xv, 21) argue, ‘The broad-brush labeling of interest groups runs from organizations hierarchically, bureaucratically and professionally structured with large economic resources, to informal bodies in their nascent stage of development that may be resource poor and activist based, to private companies, to public organizations etc.’ (see below for a fuller discussion).

The deluge of terms also emerges because many are ‘tied’ to specific areas of research going hand-in-hand with specific approaches and normative assessments. Before discussing the most important ones, we present our own conceptualisation of interest groups. It remains the most commonly used neologism and most contributors to this volume use it, although we acknowledge that this label carries much baggage (see Jordan et al. Citation2004; Jordan and Maloney Citation2007). What are the key features or components which define an actor as an interest group? Basically, we propose three factors: organisation, political interests, and informality.

Organisation relates to the nature of the group and excludes broad movements and waves of public opinion that may influence policy outcomes as interest groups. Interest group politics concerns aggregated individuals' and/or organised forms of political behaviour. The defining nature of this aspect is exemplified by the fact that several contributors to this volume interchange the concept ‘interest organisations’ with the concept ‘interest groups’. Political interests refer to the attempts these organisations make to influence policy outcomes. This aspect is often called political advocacy, which refers to all efforts to push public policy in a specific direction on the behalf of constituencies or a general political idea. This notion of advocacy places interest group research squarely within the broader literature on political representation. Informality relates to the fact that interest groups do not normally seek public office or compete in elections, but pursue their goals through frequent informal interactions with politicians and bureaucrats. This, however, does not rule out that important facets of state–group relations in capitalist democracies can be heavily institutionalised.

The combination of these three features makes the population of interest groups rather heterogeneous and often difficult to delineate. Not all organisations are political interest groups, but many are what Truman (Citation1993) has called latent interest groups. For example, enjoying swimming or taking part in swimming competitions is the main – rather apolitical – business of the members of a swimming club. But if the swimming club lobbies the local government in order to obtain subsidies for maintaining the club or building a new swimming pool then it can be viewed as a political actor. Hence, many civic associations are episodically politically active and differ considerably from organisations such as Greenpeace whose most important objective is to influence environmental policies. Some organisations are permanently involved in politics, while for others political activities are more sporadic and ephemeral.Footnote3 Needless to say – and despite a comprehensive literature on political mobilisation (see below) – it is rather difficult to predict in what circumstances latent interests become manifest and enter the political process.

It is useful to contrast our definition of interest groups with other traditional participants in the policy process such as political parties, bureaucracies or governments. Bureaucracies are formally part of government and the main goal of political parties is to run government or control the parties in government. In contrast, interest groups do not usually have office-holding as a primary goal. However, even in this area there are no clear demarcations – the boundaries are blurred (for instance see Cammisa Citation1995). Interest group activities are largely focused on influencing policy outcomes, trying to force issues onto, or up the political agenda, and framing the underlying dimensions that define policy issues. Within this task list it should be noted that differences among interest groups can be considerable. While most groups are only consulted by policy-makers, under certain circumstances they may formally take part in some government activities or be legitimised by some sort of subsidiary principle: e.g. the autonomy to regulate specific sectors. Many welfare policies in continental Europe (the so-called Rhineland model), but also the current efforts at strengthening self-regulation and co-regulation by interest groups in the EU (see Commission 2002; ESC Citation2005), embrace this type of interest intermediation.

The sheer size of the interest group population, which is appreciably larger than the political party terrain, as well as the manifold differences between the groups pose significant problems when we move to empirical analyses (Berkhout and Lowery Citation2008). Given that the extent of political mobilisation differs significantly within the interest group population there is a rather heterogeneous set of potential cases to study. This makes it difficult to delineate a set of relevant cases. Frequently researchers have to draw samples from an unknown population (in terms of both quantity and quality). In that respect, we encounter a substantial difference between the study of political parties and interest groups. The former can be modelled as being principally concerned about political influence, electoral politics, and public office or public policy. In short, the raison d'être of parties is electoral politics – i.e. political parties seek to maximise the number of seats in the relevant legislature.

The strategies and tactics of interest groups are much more diverse and diffuse. While political parties have a rather general policy agenda that inevitably covers many issues, interest groups often tend to specialise in a handful of policy areas. Accordingly, it is very difficult to draw general conclusions concerning the organisational structures, the functions, or the influence of interest groups. Most of the time, conclusions are restricted to particular types of groups and their influence with regard to specific issues or policy areas under a specific set of conditions. This complexity is an important explanatory factor accounting for the prevalence of case studies in this area of political science. However, while the case study method can shed much light, this research strategy does not necessarily enhance the development and accumulation of literature. Only in recent years have quantitative studies (see the contributions in Coen Citation2007) and combined quantitative and qualitative approaches (see Dür and De Bièvre Citation2007) gained more ground in the study of interest groups in the EU. In sum, one of the reasons why there is a relative scarcity of interest group research and why groups are mostly studied in the case study mode is the simple fact that this is a complex area that militates against generalisability.

As noted above, a more significant explanation for the peripheral position of interest group scholarship relates to the cacophonous surfeit of definitions, concepts and approaches in the field that very often refer to similar, if not identical, phenomena. It is quite remarkable how such a relatively modest field is so heavily Balkanised. In some ways, such diversity indicates a multi-faceted research agenda and highlights the richness of a field with many different research puzzles. But it comes at a cost as it often goes hand-in-hand with a lack of intellectual communication and cross-fertilisation and may even generate contradictory outcomes.Footnote4

The concept ‘interest group’ can itself be somewhat misleading as it refers to the fact that individuals, organisations or institutions are associated in a body that designs strategies and tactics aimed at influencing public policy. However, not all interest group scholars study groups in this way. Some consider institutions (such as hospitals, schools or universities), firms or local governments as interest groups or interest organisations (see Cammisa Citation1995; Gray and Lowery Citation1996). These institutions are not, strictly speaking, part of government, but they show some level of organisation, they exhibit policy preferences and their capacity to mobilise resources makes them potentially powerful. Accordingly, it makes sense to conceive of such actors as interest organisations that are equivalent to interest groups, although they are not strictly speaking aggregating (or grouping) the preferences of some constituency (individuals, firms or organisations). Many interest groups have no members. Drawing on data on almost 3,000 social welfare and public affairs groups established between the early 1960s and the late 1980s, Skocpol (Citation1995) found that nearly 50 per cent had no members (see also Berry Citation1984). While many interest groups are indeed associations, a significant portion of the field does not consist of traditional membership groups but of organisations, institutions, firms and even regional branches of government that act like, or are, interest groups. Hence, interest groups and interest organisations are united in their function to influence public policy (see Jordan et al. Citation2004; Jordan and Maloney Citation2007: 32). Distinguishing interest groups from interest organisations acknowledges the existing heterogeneity and reduces some ambiguity through clearer labelling thus capturing important empirical and theoretical distinctions.

Special Interests, Social Movements, and Civil Society

Scholars in other subfields have adopted concepts that reflect their focus on specific subpopulations as well as an emphasis on different causal factors and social mechanisms. We restrict our brief discussion to three alternative definitions that are common in the literature: special interest organisation, social movement organisation, and civil society organisation.

The concept special interest organisation is en vogue among political economists. Essentially it refers to an important attribute attached to interest groups and acknowledged by political scientists – namely that groups often represent a narrow faction of the body politic. Accordingly, interest groups can be considered as a threat to the democratic/general interest because narrow sectional interests will mobilise and influence government policies whereas diffuse interests will be less capable of organising. Much political science literature as well as much of the public political discourse on interest groups shares this view.Footnote5 Often researchers in the field conclude that the interest group population consists mainly of specific economic interests and consequently they narrow their empirical research to these types of interest groups. As a result, many contributions in this vein have an implicit normative undertone that considers interest groups as inimical to democratic governance, contributing to economic sclerosis and biasing political representation. However, this perspective is by no means uncontroversial or uncontested. For example, much empirical evidence questions the economic and rationalistic underpinnings of Olson's (Citation1965) collective action puzzle and demonstrates that diffuse interests are capable of effectively organising (see for example Green and Shapiro Citation1994: 72–97). Many studies highlighted the role of group entrepreneurs (Salisbury Citation1969; Moe Citation1980), institutional patrons (Walker Citation1991), and the importance of factors such as collective identities (Offe Citation1995) for the mobilisation process. Another conclusion that is often linked to this perspective concerns the assumption that ‘mobilisation’ is associated with ‘strength’. This is a view that is also prevalent in the literature on EU interest groups. However, there is a plausible argument that mobilisation may actually be a sign of weakness. It can be a post factum response to some political threat: e.g. a hostile public opinion, threatening political initiatives, or countervailing mobilisation (see Walker Citation1991; Berry Citation1993; Smith Citation2000; Greenwood Citation2002: 70–73).

The other two concepts –social movement organisation and civil society organisation– view group mobilisation more positively. Literatures that use these labels go to great lengths to avoid the ‘interest group’ label because they associate this term with selfish inside lobbying (usually conducted by narrow economic or sectional interests). Much of the social movement literature in which the social movement organisation (SMO) concept is prevalent shares, when it concerns interest groups, basic normative insights of the political economy literature. Accordingly, the SMO label is used by scholars to study allegedly different forms of contentious politics with a focus on political opportunity structures as well as the processes of identity formation and the mobilisation of resources in SMOs (della Porta and Diani Citation1999). The main difference between this literature and the political economy perspective is that the former emphasises to a greater extent the conflictual nature of politics. It focuses on how citizens form grass-roots networks and organisations, how they use non-institutionalised forms of claim-making and how contentious politics contributes to the creation of political identities.

In contrast, interest group approaches tend to stress the semi-institutionalised process of lobbying and the importance of resources such as expert knowledge. Interest group scholars are less tempted to portray organised interests as outsiders or beggars at the (policy-making) gate. They portray politicians and bureaucrats as having interests of their own and as seeking support from interest groups. Indeed, on many occasions, policy-makers depend on authoritative or expert information or other resources supplied by groups. Interest group scholars tend to depict the role of groups as politically and democratically useful – in terms of the functional expertise they supply – and as crucial to the proper functioning of democracies – certainly not as trouble-makers. Although these distinctions are not always that clear-cut, it is quite remarkable how these bifurcated scholarships de facto analyse similar forms of political organisations but attach different labels to them: NGOs, diffuse interests, public interests, and social movement organisations. This bifurcation goes hand-in-hand with a somewhat different – often implicit – normative outlook. As Grant (Citation2002: 3) notes ‘NGOs’ is a ‘hurrah’ word compared to the ‘boo’ word ‘interest group’.

While the social movement literature has no explicit normative concern, there is a large normative literature that applauds the emergence of so-called civil society organisations that mediate between individual citizens and the institutions of government. It would take us too long to review the vast (pluralistic) literature running from Madison, de Tocqueville, Bentley, Truman, and Dahl to Putnam. But its main thrust is that a dense and diverse network of political and civil society organisations enhances democratic efficiency and contributes to the creation of social capital which is seen as undergirding democracy. This argument is echoed in some of the Europeanisation and integration literature that is increasingly being stimulated by the European Commission's ‘hope’ that civil society organisations may help plug the democratic deficit (Commission 2001, 2002). Although social movement scholars and the normative civil society literature often deal with the same sort of organisations, both tend to generate different conclusions. On the one hand, social movement scholars highlight the importance of political conflict as constitutive for the development of political societies and as something to which social movement organisations contribute. On the other hand, the normative literature on associative democracy conceives civil society organisations as vital for the health and stability of representative and democratic governments (Cohen and Rogers Citation1995).

Why are Interest Groups Important for the Study of Politics?

As outlined above, the study of political interest groups is plagued by all kinds of conceptual problems, the Balkanisation of the field and the difficulty of building research designs that facilitate the accumulation of knowledge. Nevertheless, the systematic study of interest groups and interest organisations is crucial for several reasons – many of which are discussed in more detail in the individual articles below. Several contributions focus on the EU literature on interest groups because European integration is one of the main causes for the changing nature, and growing importance, of interest group politics in Europe. While the EU is certainly not the sole cause of change (see also Grote and Lang Citation2003), it exemplifies some key trends and the significance of interest groups, which makes it an important object for the comparative study of these entities.

The European Interest Group Population

Before examining in detail the specific impact of the EU as a contributory factor in the growing importance of interest groups, we discuss several relevant trends. First, the number of interest groups is much larger than the number of other types of political organisations such as political parties. It is also worthwhile highlighting that the mobilisation capacity of interest groups is considerable: more citizens, as well as organisations wherein citizens are professionally active (firms, business, institutions), are part of the interest group universe compared to political parties. Mair (Citation2006) noted an erosion of party support and several scholars have highlighted the reductions in party membership and the corresponding dramatic rise in both group numbers and the numbers in groups. Jordan and Maloney (Citation2007) record that the Directory of British Associations (CBD Citation2006) lists 7,755 organisations – 48 per cent of which were founded in the 1966–95 period. In 1956 the (US) Encyclopedia of Associations estimated that the number of Washington DC-based organisations was just under 5,000, by 1997 it had risen to 22,901 (Putnam Citation2000: 49). Jordan and Maloney (Citation2007: 3) suggest that such an ‘explosion from the 1960s seems normal in all politically mature systems’. Between 1950 and the mid-1990s ‘Aggregate Party Enrolment’ declined in many advanced democracies: from 1.3 million to 600,000 in France; from 3.7 million to 1.9 million in Italy; and from 3.4 million to 800,000 in the UK (Scarrow Citation2000: 89). Meanwhile many (public) interest groups have relatively ‘healthy’ membership in the UK: the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) 1 million; the Countryside Alliance has over 100,000 ordinary members and a further 250,000 associate members; and Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace and Amnesty International have memberships in excess of 100,000. Finally, Hall (Citation2002: 25) suggests that the average number of associational memberships in Britain grew by 44 per cent between 1959 and 1990 (see Jordan and Maloney Citation2007 for a detailed discussion).

Second, the decline of party thesis posits that groups are more effective linkage vehicles on the basis that parties are fewer in number, have suffered from a declining membership base in recent decades, and are subject to increasing electoral volatility as well as low, and in some cases falling, electoral turnout and declining trust. Related to this, policy-making is increasingly segmented and dispersed over different arenas and specialised agencies, several of which are clearly non-majoritarian (Mair Citation2006). The shifting of policy-making, as a result of delegation, from arenas where electoral politics is relevant (e.g. the domestic level and legislative bodies) to highly specialised agencies creates fertile areas in which groups can flourish. It is important to keep in mind that the EU is not a ‘state’ in the traditional sense as we know liberal-democratic nation-states. Its complex system of multi-level governance has both contributed to the horizontal segmentation and the dispersion of policy-making capacities across different levels. In some ways this limits governmental manoeuvrability and, more importantly, it has hollowed out the importance of electoral competition within the EU member states. In short, much politics is no longer predominantly organised on a partisan basis.

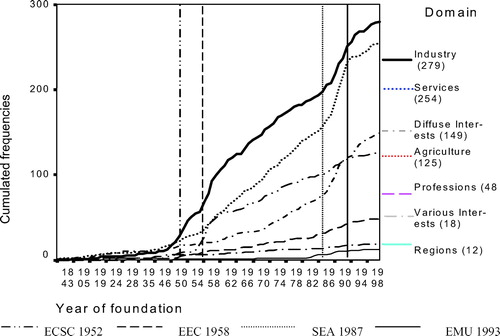

In response to the dispersion and sharing of political competencies among European and national institutions, domestic interest groups that were traditionally active within national arenas have extended their reach beyond national borders (see Princen and Kerremans Citation2008). This process has increased the number of access points and channels through which political conflicts can be resolved. As a result the density (numbers) and diversity (range) of the EU-level interest group population has increased considerably over time. At the start of the European integration process (1950s/60s) a small number of interest organisations were active in Brussels (Eising and Kohler-Koch Citation2005).Footnote6 illustrates the density and diversity of the interest group system and demonstrates that in the early days the population consisted mainly of specific economic interests. However, in more recent years the number of diffuse interests or NGOs has grown appreciably.Footnote7 Initially, EU interest organisations were mainly sectoral or cross-sectoral peak associations of national interest groups. Today many are mixed membership groups that include combinations of national associations, multinational corporations, other interest organisations as well as cities and regions. These mixed membership organisations cover most issue areas. It is now commonplace for large numbers of firms, national associations, regions, and political consultants to have Brussels offices – and many more are frequent commuters.

FIGURE 1 EUROPEAN INTEREST GROUPS ACCORDING TO DOMAIN AND YEAR OF FOUNDATION FROM 1843 TO 2001 (CUMULATED FREQUENCIES)

While the ‘lobby system in Brussels’ is no longer in its nascent stage of development, the EU system of interest representation remains less stable and less consolidated than some national associational systems. This is a consequence of the mutating EU constitutional structure and the series of treaty revisions since the Single European Act in 1986 which led to more majority voting in the Council of the EU, enhanced the powers of the EP and equipped the EU with more policy competencies in a greater number of issue areas. It is also likely that successive enlargements had a significant impact on the EU system of interest representation – a largely under-researched phenomenon (but see Blavoukos and Pagoulatos Citation2008). The changing EU interest group system and increasing group density and diversity has led some scholars to characterise the EU system as quasi-pluralist (Streeck and Schmitter Citation1991; Schmidt Citation1999).

But why would the EU, and more generally the fragmentation, segmentation and dispersion of its access points, be such a fertile environment for interest groups to flourish? Studies on the relations among federal (or multi-level) systems and interest group systems suggest three major reasons (Armingeon Citation2002: 214). First, multi-level systems allow for greater interregional differences in interest group organisation than unitary states. Second, cultural, social, and economic differences are more pronounced in multi-level systems than in unitary states, giving rise to greater variety of interest organisations. Finally, in unitary states interest groups have greater incentives to concentrate on central-level representation whereas the dispersion of political authority in multi-level systems makes for greater differentiation within the associational landscape. Hence, most of the evidence points to multi-levelness and segmentation as forming a conducive environment for the formation of interest groups. Most research also finds a growing diversity and density of the interest group population in advanced political economies (Atkinson and Coleman Citation1989). However, the jury is still out with regard to the question on whether this improves the influence of private actors versus government actors or vice versa. While some studies point to a multitude of access points (Pollack Citation1997), find interest groups heavily involved in the formulation (Sandholtz Citation1992) and implementation of EU policies (Wolf Citation2005), there is also evidence that points to the resilience with which state actors adapt and play a key role when trying to push public policies (Baltz et al. Citation2005; Grande Citation1996).

Explananda and Gaps of EU Interest Group Research

Therefore, it is useful to clarify some ambiguities in the key explananda of interest group research and how the roles and functions of groups are conceptualised. In studying EU interest group politics, contemporary scholars have devoted much attention to the conditions under which European interest groups mobilise (Greenwood and Aspinwall Citation1998; Weßels Citation2004; Mahoney Citation2004), the institutional configurations that promote or constrain access (Marks and McAdam Citation1996; Grande Citation1996), the resources and strategies that affect access (Bouwen Citation2002; Beyers Citation2004; Eising Citation2007a), the channels and levels most likely to be used (Bennet Citation1997; Beyers Citation2002; Coen Citation1998; Eising Citation2004), the stages during which lobbying will be most effective (Crombez Citation2002), and the distinction between public and business interests as well as diffuse and specific interests that affect access and influence (Pollack Citation1997; Baltz et al. Citation2005). Few EU studies deal explicitly with the measurement of influence and the political impact of interest groups which is indeed one of the most fraught, difficult and complex problems in political science research (see Dür Citation2008).

Perhaps this gap in the literature reflects a social and political reality that is not always fully comprehended. It is important to remember that there are multiple reasons why organisations lobby and seek to shape public policies. Organisational perspectives suggest that their political activities are not always related to the political issue at stake or the aim of influencing specific policy outcomes (see Wilson Citation1995; Knoke Citation1990; Lowery Citation2007; Schmitter and Streeck Citation1999). Lobbying can also serve organisational maintenance by developing political and technical expertise, gathering information, sustaining political networks, or enhancing public visibility vis-à-vis key constituencies. In order to be able to generate political influence in the long run, interest group entrepreneurs seek to develop strategies that facilitate group survival.

The twin rationales of lobbying success and organisational survival are not always compatible. Interestingly, there is an inherent tension between these two demands. Seeking political success through high-profile campaigning may actually threaten the group's long-term survival or its political influence. While high-profile campaigns and protests may generate the necessary publicity that maintains the flow of vital funds into the organisational coffers, they may be counterproductive in terms of contributing to policy solutions because other key actors could view these activities as irresponsible or sensationalising complex issues (Wilson Citation1995). Hence, organisational survival is only ensured if seeking effective influence over policy outcomes by means of an insider strategy counts less with members/supporters than high-profile protests. In fact, social movement or citizen groups that are financially dependent on their membership and provide no selective material rewards may need to stick close to the protest mode because, after all, they are selling protest (Jordan and Maloney Citation1997, Citation2007).

Thus while much lobbying could easily be viewed as ineffective in terms of shaping policy outcomes, this may under-estimate the usefulness of the lobby effort from the organisational maintenance perspective. The practice of lobbying can create positive externalities that are not directly related to policy outcomes. The political activities of many interest groups are not limited to lobbying on specific issues, but include diffuse practices such as attending workshops, receptions, press conferences, monitoring newspaper and other media stories. Interest groups monitor the policy process to generate information for their clients and constituencies. Interest group goals are often quite diffuse. Many interest group activities concern what we could call ‘market policies’, that try to shape the reputation of groups and the sector they represent among a broader set of market participants including consumers, stakeholders and competitors. Image building, reputation management and/or damage control are relevant aims for many interest groups. Finally, as noted above, in some areas it makes little sense to speak about interest groups influencing policies or pressurising policy-makers because they are integral to the design and execution of public policies (e.g. standard-setting or private rule-making). In these areas, the distinct roles traditionally attributed to public and private actors are blurring (Lehmbruch Citation1977; Cowles Citation2003).

The EU system of interest representation is also a rich laboratory for the study of interest group politics from a broader perspective – i.e. how groups act, develop and survive in a system that is neither a traditional state nor a traditional international organisation. One of the intriguing puzzles is that the expanding scope of the EU seems to increase the diversity of the interests mobilised. While the initial focus on market integration certainly provided greater incentives for economic – export-oriented – interests to get organised and represent their interests at EU level, the EU is now expanding its scope of governance into other policy areas such as social, immigration, and foreign policy. These enlarged activities and involvements can also be presented as an antidote to the powers of specific interests that may dominate some smaller domestic polities. Therefore, integration could have a normatively positive effect on the biased nature of political mobilisation as the larger scale and scope of governance may stimulate the mobilisation of a more diverse set of interests.

The impact of EU integration on domestic interest group systems is another crucial issue. While much has been written about the interface between domestic and EU-level interest groups, we lack the space here to review this extensive literature. Nonetheless, it is important to emphasise that the growing volume of the EU-level interest population has implications for domestic interest groups. These bodies increasingly have to take into account EU-level aspects, including both EU-level interest organisations and interest organisations in other member states. The importance of the continuing interaction among the EU level and the national level has led to a substantial Europeanisation literature that deals with the adaptation of national modes of interest intermediation (for a review, see Eising Citation2007b). One of the contributions of EU scholarship to the general literature on interest groups is the need to study multiple institutional arenas and how they interact, e.g. what Cowles calls the ‘false domestic vs. international dichotomy’ (Cowles Citation2003). Indeed, a substantial number of domestic groups take part in EU-level lobbying processes and EU policies can have profound consequences for domestic political opportunity structures (see Eising Citation2009).

Three Prevailing Research Puzzles: Bias, Cleavages and Organisations

Given the current ‘state of the art’ of the interest group literature we identify three main research problems that should be addressed in future research projects. Typically, these issues are characterised by profound uncertainties and knowledge gaps. First, the skewed political representation delivered by the interest group system. Second, the relationship between interest groups and underlying political cleavages. Third, the link between organisational maintenance and influence strategies. The limited accumulation of knowledge in these areas is due to the fact that much interest group research is still based on isolated case studies, weak conceptualisation and one-sidedness in terms of research questions. There have been very limited efforts at integrating different approaches and linking them to more general political science problems. Our discussion and the following articles seek to provide greater clarity on these points.

Political Bias

The emergence of the EU-level system of interest representation and the proliferation of interest groups in domestic contexts have important political and normative implications. Many scholars have correlated the size, structure and composition of an interest group system with the policy process and policy outcomes. Moreover, it appears that the institutional and political context affects prevailing organisational formats, strategies, and tactics. Thus, due to the focus of the EU institutions on market integration, citizen interests or diffuse interests were for many years severely under-represented at the EU level. It also appears that expertise-based inside lobbying dominates grass-roots mobilisation. As noted above, many observers therefore suggest that the EU system of interest representation is strongly biased in favour of economic and concentrated interests (see Greenwood and Aspinwall Citation1998; Bouwen Citation2002). Only the successful mobilisation of diffuse interests during the last ten years has led to a view among some scholars that the EU might evolve towards an associative democratic structure (see Heinelt Citation1998; Smismans Citation2004). Still, it could in fact be the case that EU interest representation is heavily biased and, therefore, reinforces or reproduces existing power constellations instead of contributing to a Europe-wide system of competing interests.

The bias question is one of the most enduring and important in interest group research. It has major normative implications for the characterisation of European/EU democracy, political legitimacy and European politics generally. In our opinion, research on this issue would be more fruitful if bias were conceived as a complex conceptual and empirical puzzle. The biased nature of politics is too often taken for granted even though it is not particularly well comprehended. First, many interest groups do not fulfil the functions which some normative theorists tend to ascribe to civil society organisations. They are neither efficient deliberative vehicles nor do they intermediate between the state and society (see Warleigh Citation2001; Roose Citation2003). Indeed, many interest groups – even the so-called civil society genre – are not well equipped to fulfil these functions. For example, Maloney and van Deth (Citation2008) found that engagement with and confidence in the EU (compared to national institutions) was relatively weak among the group of citizens that the social capital model predicts would be highest – associational members. Moreover, Mahoney (Citation2008) found that interest groups – in ‘their’ role as intermediary associations and using ‘outside lobbying’– were not particularly successful in fostering citizen engagement. The modern era is characterised by the growing professionalisation of the interest group industry, and weak links between interest groups and grass-roots memberships also militate against groups performing such a role.

Furthermore, domestic as well as European political institutions ‘organise bias’ by regulating access through subsidies, the setting up of advisory committees and so on (Greenwood and Aspinwall Citation1998). Hence, bias is not simply a matter of variation among a set of existing interest groups and their organisation at different levels of government, their resource endowment or the access they gain to the media and government. To rephrase Schattschneider (Citation1960): political institutions themselves and the ways in which they incorporate societal interests into policy-making constitute a mobilisation of bias. Finally, some sections of society – prisoners, illegal refugees, the mentally ill, children, the homeless – simply do not get organised because they lack the necessary resources or skills. In this sense, bias reflects the unequal distribution of resources in society. The existing interest group system, which in our view also includes so-called civil society organisations, does not, and cannot really redress this but replicates or maybe even reinforces existing inequalities (Grant Citation2001).

What is more, in normative terms bias is not always a negative phenomenon. Beyond the ‘negative’ aspects of skewed participation there can be ‘positive’ biases. The alleged pathology of unrepresentativeness and the arguments about the decline of civic and political involvement require more examination than the headlines suggest. For example, as political advocates, some groups perform a surrogate function acting on behalf of constituencies that lack resources. Many groups seek to advance causes that benefit constituencies and interests beyond the direct interests of participants (e.g. poverty in Africa, human rights in Zimbabwe, homelessness). Furthermore, there may be redistributive or progressive elements to skewed involvement. Many wealthy citizens patronise causes that poorer citizens also support. For example, many relatively poor citizens have strong pro-environmental attitudes but cannot afford the indulgence of membership. As a form of cross-subsidisation, the contribution of their wealthier co-citizens ensures that this interest is represented (almost akin to business travellers subsidising the airfare costs in economy).

Another reason for scepticism about the heroic normative claims relates to the way competencies are divided and shared in a complex system of multi-level governance is that much bias is the result of interest group specialisation. Groups may not be active in policy sectors where EU competencies are weak or non-existent or where their interests are not affected, and they may also concentrate on those areas where they believe they are likely to be most influential. Groups may be absent from the EU level, not because they do not have resources, are weak, or EU institutions discriminate against them or they do not appreciate potential European benefits but simply because they are able to realise their political goals at the domestic level (Beyers and Kerremans Citation2007). So while some bias is surely the result of existing inequalities in society, a second component of the explanation has no direct relationship to differential resource bases. Therefore, we should exercise great caution when evaluating the unequal political mobilisation of different groups.

Political Cleavages and Interest Groups

There is a dearth of work on the relationship of interest groups to the underlying political cleavages and the inter-organisational dynamics of cooperation and competition. Most work in this area has remained descriptive, and more systematic research emanating from social movement scholars is a relatively recent advancement (see for instance Imig and Tarrow Citation2001). Little cross-fertilisation exists between the burgeoning literature on EU party politics and political cleavages, on the one hand, and the EU interest group literature, on the other. Researchers continue to pay little attention to the possibility that a small number of political cleavages shape the EU interest group system (exceptions include Weßels Citation2004; Beyers and Kerremans Citation2004). Although this topic – the structure of conflict and consensus – is central to many fields of political science, it has received too little systematic attention from interest group scholars. A more explicit and thorough linkage of interest group politics with the overall structure of conflict in a polity seems crucial in order to better understand the role of advocates in a broader political context. At this point, many studies deal with one type of political organisation (often parties, sometimes interest groups) and then make indirect inferences with regard to the other type. Systematic comparison is required.

Often the literature presents these two types of political representation – parties and interest groups – as completely discrete phenomena occupying fundamentally different ideological niches. However, empirical patterns of complex overlap and competition may turn out to be problematic for the overall relationship between parties and interest groups. For instance, as parties seek to become part of government, they often have to balance conflicting demands originating from the interest group system for resources and regulations. Claims with regard to different policy areas have to be aggregated into an overall party programme. In contrast, while making claims interest groups need not worry about the budgetary implications of governmental spending increases or cuts, or about the potential or actual regulatory changes that may flow from acceding to their demands. Groups cannot be punished through elections for any negative externalities flowing from their successes. In contrast, parties may face electoral defeat if economic downturn is attributed to imprudent fiscal policies or if they ignore or reject group claims that accord with the views of a significant proportion of the electorate.

A more thorough comparative analysis of political parties and interest groups would be instructive in order to examine both the specific features of each type of political organisation and the interaction between and among them. Such an integrated approach would represent an important advance beyond the isolated focus on single types of political organisation. However, we should not under-estimate the substantial intellectual challenge involved in this exercise. There are at least four separate literatures that need to be analysed/synthesised: social movements, agenda-setting, party politics and political cleavages and the organisational literature on parties and interest groups.

Organisational Maintenance and Political Behaviour

More systematic attention must also be devoted to the link between the intra-organisational dynamics of interest groups and their external political behaviour. While group–government interactions have gained a central place in many research projects (see above), especially in EU-level studies, very few pay attention to intra-organisational dynamics and how these relate to the large variety of political activities that groups may develop (see Greenwood Citation2002).

The tension between the internal dynamics of interest groups (i.e. getting and staying mobilised) and their external purposes (i.e. achieving political influence) is not novel and has been explored by many scholars. For example, Schmitter and Streeck's (Citation1999) distinction between the ‘logic of influence’ and the ‘logic of membership’ is a good example (see also Wilson Citation1995; Moe Citation1980; Knoke Citation1990; Lowery Citation2007). What we claim, however, is that the explicit linking of these mechanisms (or logics) has been somewhat ignored in recent empirical research projects. Moreover, a closer investigation of the internal logic of political mobilisation and how this relates to the choice of political tactics and strategies is important for understanding the bias in political mobilisation as well as the political cleavages related to the politics of organised interests.

In addition to this, there are several reasons to expect that the intra-organisational dynamics – e.g. relations among groups and constituencies – are of increasing importance for group survival. As groups grow in number and diversity their competition for critical resources also increases. Likewise, the growing complexity of a group's political and socio-economic environment – again the EU is an obvious example – means that its constituency or its ‘customers’ are likely to become increasingly dependent on group services such as information about key political, social and economic developments. Thus, if an interest group is unable to meet these demands, its membership may choose to exit and may join another group or even establish a new competitor organisation.

How these intra-organisational dynamics relate to the political strategies of groups and the policy agendas which reflect underlying political cleavages is not yet well understood. There is, however, some excellent research being conducted in this area (see Binderkrantz Citation2003, Citation2005). Generally, the literature distinguishes between insider and outsider strategies (Wilson Citation1995; Kollman Citation1998; Walker Citation1991; Grant Citation2001) whereby the former concerns networking with key administrative and political elites, while the latter includes media strategies (such as issuing press releases or writing letters or articles) and the mobilisation of constituencies (letter-writing campaigns, petitions or demonstrations, etc.). All interest group leaders face the dilemma of how to balance the advantages/disadvantages of insider strategies and outsider strategies (see above).

In this regard, it would be interesting to investigate the connection between the strategic choices groups make and their organisational development.Footnote8 Three different stages can be distinguished: start-up, the stage where the group enjoys an insider status, and the crisis point over the best strategy.

Outsider strategies may be important in the nascent stage of development. At this point gaining public attention is critical for membership groups in order to entice potential members to join as well as to raise awareness among policy-makers. At this stage competition for new members is high. Initially (at least) high-profile outsider strategies can be viewed as crucial for organisational maintenance reasons.

As groups mature they get more experienced at balancing internal and external pressures. Established groups have solved their resource problems and occupy stable policy niches. They gain access to the policy process and seek to insinuate themselves into the insider game. Such strategic constellations are common in areas characterised by policy monopolies or domains where access to the policy process is limited. Outsiders seek to challenge and undermine the dominant idea that underpins the policy monopoly (Baumgartner and Jones Citation1993). Neo-corporatism whereby certain groups are granted a privileged institutional position can be seen as such a policy monopoly.

Yet there are strategic constellations in which insider strategies are increasingly combined with outsider strategies and may ultimately result in a dominant preference for outsider strategies. Established groups specialised in insider strategies may turn to outsider strategies when their insider position and the related policy monopoly comes under pressure as a result of successful mobilisation by outsiders' developments within a policy area. For example, European farmer interest groups are active on and integrated in the inside track, but are also vocal in the public sphere. A large number of threatening challenges – such as environmental interests, development concerns, and the pressure of international trade negotiations – are critical for farming interests and challenge their positions as an established interest. Accordingly such interest organisations need to find a balance between different strategies. On the one hand, failing to respond to the demands from members may backfire, but, alternatively, turning to outsider strategies may damage relations with government.

Overview of the Volume

The contributions to this volume provide a theoretical state-of-the-art reflection on interest group politics. Each contribution focuses on a specific topic and provides a discussion of the relevant theoretical propositions with the aim of assessing the extent of intellectual progress and/or stagnation. All authors were asked to reflect on the theories and methods that have been used, to provide a brief evaluation of the merits and shortcomings, and to summarise some existing empirical knowledge. They were also encouraged to think laterally by exploring areas that have not been previously studied and have lacked specific attention, by drawing on various strands of political science, and by attempting to integrate these different dimensions. By doing this we hope that each contribution identifies some contested (and relatively uncontested) research questions as well as potential new research agendas.

The contributions combine the analysis of interest group politics in the EU with the comparative study of interest organisations. While EU politics is at the core of most contributions, the volume provides coverage beyond the EU and places national and EU systems in direct comparison. In addition, it focuses on the interface between systems and levels of governance. Unlike most EU interest group studies that examine different sectors, policy areas or types of interest organisations, this volume takes a more general approach and is organised around three major research themes.

After this introduction, the first section focuses on the relationship between the EU institutional setting and the politics of interests in the EU. First, Princen and Kerremans analyse the consequences of the EU multi-level setting for the political opportunity structures of interest groups. They connect this with a theoretical discussion of four analytical literatures that deal with this topic. Their reflections reduce these four literatures into two generic approaches; one that views political opportunity structures as an external fixed constraint and another that sees them as the result of a policy process in which groups themselves take part. Second, Blavoukos and Pagoulatos concentrate on the consequences of successive enlargements on the system of interest organisations at the EU level. For this largely under-studied topic they develop a framework that conceptualises enlargement as having an impact on the structural properties of groups as well as the agenda content of EU interest associations.

The second section focuses on dominant practices, cleavages, and power relations. Beyers examines the micro-logic of interest representation, investigating whether interest organisations follow a logic of arguing or a logic of political exchange and to what extent these different logics are shaped by the nature of policy issues and organisational format. Thereafter, Eising analyses the macro-patterns of EU interest intermediation, beginning by searching for cross-sectoral patterns based on the distinction between pluralism, corporatism, and statism. Thereafter sectoral, issue-specific and longitudinal variations are subjected to investigation. He suggests tying the typological study of interest intermediation closer to the explanatory theory of interest organisations. Dür examines the notoriously difficult topic of power relations in EU politics. First he discusses the concepts of power and influence, and subsequently re-analyses the findings of qualitative and quantitative studies. His contribution lists different ways that address the obstacles in assessing power.

The final section is explicitly comparative. Baumgartner and Mahoney compare the research on interest group politics in the United States with that of the EU, accounting for the major differences and similarities. They also engage in some lesson drawing from both academic literatures. They conclude that the perspectives on interest group politics are increasingly converging and that, for various reasons, the European scholarship is comparatively more international in its focus than the American scholarship. Thereafter, Lowery, Poppelaars and Berkhout discuss the general conceptual and methodological limitations of comparative interest group research by reviewing interest group literatures on the US, the EU and the Netherlands. They argue that it is difficult to build interest group theories that hold up in different contexts. Based on the core concept of political representation, the final contribution by Saurugger offers a critical analysis of the role of civil society as it is highlighted in the normative study of EU democracy. Her main argument is that normative puzzles on the role of associations are in need of systematic qualitative and quantitative research in order to understand what groups can or cannot contribute to democratic representation.

Notes

1. For instance, a search on the keywords for articles published in the European Journal of Political Research resulted for the period 1997–2005 in six articles which have the keyword ‘interest groups’, in contrast to 94 articles that have ‘political parties’ as keyword.

2. Policy-makers tend to inflate this abundance of concepts. For instance, the European Commission counts employers federations and trade unions (the ‘social partners’), other organisations representing social and economic players, non-governmental organisations uniting actors in a common cause, community based organisations set up within society, and religious groups all among the ‘civil society organisations’ (Commission 2002: 6).

3. Even among a population of organised interests we find substantial differences in terms of political involvement. For example, in his study on German and French business associations Eising observed that a large group displays only infrequent political activities because they mainly concentrate on the provision of services or the coordination of markets (Eising Citation2004; see also Salisbury Citation1969).

4. A nice example is the study of national patterns of group–government interactions. In their analyses of the Europeanisation of interest intermediation in the United Kingdom, Germany, and France Maria Green Cowles, on the one hand, and Vivien Schmidt, on the other hand employ different conceptions of pluralism and, because of that, they classify one of their cases, the UK, in a different category (Schmidt Citation1999; Cowles Citation2001). The end result consists of two contradictory research outcomes (see Eising Citation2007).

5. For instance, with regard to the EU it is often argued that the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is basically the result of an influential farming lobby and that it disadvantages the general interests of consumers.

6. The various directories of interest groups in the European Union comprise different types of organisations and differ with regard to the total number of actors in each class, so that the entire population of interest organisations in the EU is not exactly known. This difference is also related to the fact that the different institutions have adopted different regulations with regard to interest groups (Berkhout and Lowery Citation2008).

7. Note, however, that founding dates do not provide us with a reliable and valid measurement on whether an organisation became political active and the amplitude of these political activities. It could be that many existing organisations remain inactive for a long period, that they then are activated for some specific upcoming issues and start ‘sleeping’ again when issue disappears from the political agenda. At this moment there is almost no systematic research on the political entrance and exit, the birth and mortality of EU-level interest organisations.

8. Here, we connect political strategies with the stages of interest group development and political agendas. Ignored is the distinction between diffuse interests, on the one hand, and specific economic interests, on the other hand (Beyers Citation2004; Binderkrantz Citation2005). Usually a correlation is hypothesised (and from time to time observed) between interest type and political strategies. Therefore, it is possible that the threefold categorisation developed here co-varies with the interest type.

References

- Armingeon , Klaus . 2002 . “ ‘Verbändesysteme und Föderalismus. Eine vergleichende Analyse’ ” . In Föderalismus. Analysen in entwicklungsgeschichtlicher und vergleichender Perspektive , Edited by: Benz , Arthur and Lehmbruch , Gerhard . 213 – 233 . Wiesbaden : PVS Special Issue 32/2001 .

- Atkinson , Michael M. and Coleman , William D. 1989 . ‘Strong States and Weak States: Sectoral Policy Networks in Advanced Capitalist Democracies’ . British Journal of Political Science , 19 ( 1 ) : 47 – 67 .

- Baltz , Konstantin , König , Thomas and Schneider , Gerald . 2005 . “ ‘Immer noch ein etatistischer Kontinent: Die Bildung nationaler Positionen zu EU-Verhandlungen’ ” . In Interessenpolitik in Europa , Edited by: Eising , Rainer and Kohler-Koch , Beate . 283 – 310 . Baden-Baden : Nomos .

- Bartolini , Stefano . 2005 . Restructuring Europe: Centre Formation, System Building, and Political Structuring between the Nation State and the European Union , Oxford : Oxford University Press .

- Baumgartner , Frank R. and Leech , Beth L. 1998 . Basic Interests. The Importance of Interest Groups in Politics and in Political Science , Princeton , NJ : Princeton University Press .

- Baumgartner , Frank R. and Jones , Brian D. 1993 . Agendas and Instability in American Politics , Chicago : The University of Chicago Press .

- Bennett , Robert J. 1997 . ‘The Impact of European Economic Integration on Business Associations: The UK Case’ . West European Politics , 20 ( 3 ) : 61 – 90 .

- Berkhout , Joost and Lowery , David . 2008 . ‘Counting Organized Interests in the European Union: A Comparison of Data Sources’ . Journal of European Public Policy , 15 ( 4 ) : 489 – 513 .

- Berry , Jeffrey . 1993 . ‘Citizen Groups and the Changing Nature of Interest Group Politics in America’ . The Annals, AAPSS , 528 : 30 – 41 .

- Berry , Jeffrey M. 1984 . The Interest Group Society , Glenview , IL : Scott, Foresman/Little Brown .

- Beyers , Jan . 2002 . ‘Gaining and Seeking Access. The European Adaptation of Domestic Interest Associations’ . European Journal of Political Research , 41 ( 5 ) : 585 – 612 .

- Beyers , Jan . 2004 . ‘Voice and Access. Political Practices of European Interest Associations’ . European Union Politics , 5 ( 2 ) : 211 – 240 .

- Beyers , Jan and Kerremans , Bart . 2004 . ‘Bureaucrats, Politicians, and Societal Interests. How is European Policy-Making Politicized?’ . Comparative Political Studies , 37 ( 10 ) : 1 – 31 .

- Beyers , Jan and Kerremans , Bart . 2007 . ‘Critical Resource Dependencies and the Europeanization of domestic interest groups’ . Journal of European Public Policy , 14 ( 3 ) : 460 – 481 .

- Binderkrantz , Anne . 2003 . ‘Strategies of Influence: How Interest Organizations React to Changes in Parliamentary Influence and Activity’ . Scandinavian Political Studies , 26 ( 4 ) : 287 – 306 .

- Binderkrantz , Anne . 2005 . ‘Interest Group Strategies: Navigating Between Privileged Access and Strategies of Pressure’ . Political Studies , 53 ( 4 ) : 694 – 715 .

- Blavoukos , Spyros and Pagoulatos , George . 2008 . ‘“Enlargement Waves” and Interest Group Participation in the EU Policy-Making System: Establishing a Framework of Analysis’ . West European Politics , 31 ( 6 ) : 1147 – 1165 .

- Bouwen , Pieter . 2002 . ‘Corporate Lobbying in the European Union: The Logic of Access’ . Journal of European Public Policy , 9 ( 3 ) : 365 – 390 .

- Cammisa , Anne Marie . 1995 . Governments as Interest Groups: Intergovernmental Lobbying and the Federal System , Westport , CT : Praeger .

- CBD (Current British Directory) . 2006 . Beckenham : Directory of British Associations and Associations in Ireland .

- Coen , David . 1998 . ‘The European Business Interest and the Nation State: Large-Firm Lobbying in the European Union and Member States’ . Journal of Public Policy , 18 ( 1 ) : 75 – 100 .

- Coen , David . 2007 . ‘Empirical and Theoretical Studies in EU Lobbying’ . Journal of European Public Policy , 14 ( 3 ) (Special Issue)

- Cohen , Joshua and Rogers , Joel . 1995 . Associations and Democracy , London : Verso .

- Commission of the European Communities . 2001 . “ ‘European Governance. A White Paper’ ” . Brussels 25 July 2001: COM(2001) 428 final

- Commission of the European Communities . 2002 . “ ‘Communication from the Commission. Consultation Document: Towards a Reinforced Culture of Consultation and Dialogue – Proposal for General Principles and Minimum Standards for Consultation of Interested Parties by the Commission’ ” . Brussels, 5 June 2002: COM(2002) 277 final

- Cowles , Maria Green . 2001 . “ ‘The Transatlantic Business Dialogue and Domestic Business–Government Relations’ ” . In Transforming Europe. Europeanization and Domestic Change , Edited by: Cowles , Maria Green , Caporaso , James and Risse , Thomas . 159 – 179 . Ithaca , NY : Cornell University Press .

- Cowles , Maria Green . 2003 . ‘Non-State Actors and False Dichotomies: Reviewing the Traditional IR/IPE Approaches to European Integration’ . Journal of European Public Policy , 10 ( 1 ) : 102 – 120 .

- Crombez , Christophe . 2002 . ‘Information, Lobbying and the Legislative Process in the European Union’ . European Union Politics , 3 ( 1 ) : 7 – 32 .

- Della Porta , Donatella and Diani , Marco . 1999 . Social Movements. An Introduction , Malden , MA : Blackwell .

- Dür , Andreas . 2008 . ‘Interest Groups in the European Union: How Powerful Are They?’ . West European Politics , 31 ( 6 ) : 1212 – 1130 .

- Dür , Andreas and De Bièvre , Dirk . 2007 . ‘The Question of Interest Group Influence’ . Journal of Public Policy , 27 ( 1 ) : 1 – 12 .

- Eising , Rainer . 2004 . ‘Multilevel Governance and Business Interests in the European Union’ . Governance , 17 ( 2 ) : 211 – 245 .

- Eising , Rainer . 2007a . ‘Institutional Context, Organizational Resources, and Strategic Choices: Explaining Interest Group Access in the European Union’ . European Union Politics , 11 ( 3 ) : 329 – 369 .

- Eising , Rainer . 2007b . “ ‘Interest Groups and Social Movements’ ” . In Europeanization. New Research Agendas , Edited by: Graziano , Paolo and Vink , Maarten P. 167 – 181 . New York : Palgrave MacMillan .

- Eising , Rainer . 2009 . The Political Economy of State–Business-Relations in Europe. National Varieties of Capitalism, Modes of Interest Intermediation, and the Access to EU Policy-Making , London : Routledge (UACES Contemporary European Studies .

- Eising , Rainer and Kohler-Koch , Beate . 2005 . “ ‘Interessenpolitik im europäischen Mehrebenensystem’ ” . In Interessenpolitik in Europa , Edited by: Eising , Rainer and Kohler-Koch , Beate . 11 – 75 . Baden-Baden : Nomos .

- ESC (Economic and Social Committee) . 2005 . ‘The Current State of Co-Regulation and Self-Regulation in the Single Market’ . EESC Pamphlet Series , Brussels

- Falkner , Gerda . 2000 . ‘Policy Networks in a Multi-Level System: Convergence towards Moderate Diversity?’ . West European Politics , 23 ( 4 ) : 94 – 121 .

- Grande , Edgar . 1996 . ‘The State and Interest Groups in a Framework of Multi-Level Decision Making: The Case of the European Union’ . Journal of European Public Policy , 3 ( 3 ) : 318 – 338 .

- Grant , Wyn . ‘Civil Society and the Internal Democracy of Interest Groups’ . paper for the PSA Conference . April , Aberdeen .

- Grant , Wyn . 2002 . ‘Pressure Politics: From “Insider” Politics to Direct Action?’ . Parliamentary Affairs , 54 ( 2 ) : 337 – 348 .

- Gray , Virginia and Lowery , David . 1996 . The Population Ecology of Interest Representation. Lobbying Communities in the American States , Ann Arbor : The University of Michigan Press .

- Green , Donald P. and Shapiro , Ian . 1994 . Pathologies of Rational Choice Theory , New Haven , CT : Yale University Press .

- Greenwood , Justin . 2002 . Inside the EU Business Associations , New York : Palgrave .

- Greenwood Justin Mark Aspinwall Collective Action in the European Union. Interests and the New Politics of Associability London Routledge 1998

- Grote , Jürgen and Lang , Achim . 2003 . “ ‘Europeanization and Organizational Change in National Trade Associations: An Organizational Ecology Perspective’ ” . In The Politics of Europeanization , Edited by: Featherstone , Kevin and Radaelli , Claudio . 225 – 254 . Oxford : Oxford University Press .

- Hall , Peter A. 2002 . “ ‘Great Britain: The Role of Government in the Distribution of Social Capital’ ” . In Democracies in Flux: The Evolution of Social Capital in Contemporary Society , Edited by: Putnam , R. D. 21 – 58 . Oxford : Oxford University Press .

- Heinelt , Hubert . 1998 . ‘Zivilgesellschaftliche Perspektiven einer demokratischen Transformation der Europäischen Union’ . Zeitschrift für Internationale Beziehungen , 5 ( 1 ) : 79 – 107 .

- Imig Doug Sidney Tarrow Contentious Europeans. Protest and Politics in an Emerging Polity Oxford Rowman & Littlefield 2001

- Jordan , Grant and Maloney , William A. 1997 . The Protest Business? Mobilising Campaign Groups , Manchester : Manchester University Press .

- Jordan , Grant and Maloney , William A. 2007 . Democracy and Interest Groups , Basingstoke : Palgrave Macmillan .

- Jordan , Grant , Halpin , Darren and Maloney , William A. 2004 . ‘Defining Interests: Disambiguation and the Need for New Distinctions’ . British Journal of Politics and International Relations , 6 ( 2 ) : 1 – 18 .

- Knoke , David . 1990 . Organizing for Collective Action. The Political Economies of Associations , Hawthorne , NY : Aldine de Gruyter .

- Kollman , Ken . 1998 . Outside Lobbying. Public Opinion and Interest Group Strategies , Princeton , NJ : Princeton University Press .

- Lehmbruch , Gerhard . 1977 . ‘Liberal Corporatism and Party Government’ . Comparative Political Studies , 10 ( 1 ) : 91 – 126 .

- Lowery , David . 2007 . ‘Why Do Organized Interests Lobby? A Multi-Goal, Multi-Context Theory of Lobbying’ . Polity , 39 ( 1 ) : 29 – 54 .

- Mahoney , Christine . 2004 . ‘The Power of Institutions. State and Interest Group Activity in the European Union’ . European Union Politics , 5 ( 4 ) : 441 – 466 .

- Mahoney , Christine . 2008 . “ ‘The Role of Interest Group in Fostering Citizens Engagement: The Determinants of Outside Lobbying’ ” . In Civil Society and Governance in Europe: From National to International Linkages , Edited by: Maloney , William A. and van Deth , Jan W. 170 – 192 . Cheltenham : Edward Elgar .

- Mair , Peter . 2006 . ‘Polity-Scepticism, Party Failings, and the Challenge to European Democracy’ . Ulenbeck Lecture , 24 Wassenaar

- Maloney , William A. and van Deth , Jan W. 2008 . “ ‘The Associational Impact of Attitudes Towards Europe: A Tale of Two Cities’ ” . In Civil Society and Governance in Europe: From National to International Linkages , Edited by: Maloney , William A. and van Deth , Jan W. 45 – 70 . Cheltenham : Edward Elgar .

- Marks , Gary and McAdam , Doug . 1996 . ‘Social Movements and the Changing Structure of Opportunity in the European Union’ . West European Politics , 19 ( 2 ) : 164 – 192 .

- Mayntz Renate Scharpf Fritz W. 1995 Gesellschaftliche Selbstregulierung und politische Steuerung Frankfurt a.M. Campus

- Moe , Terry M. 1980 . The Organization of Interests. Incentives and the Internal Dynamics of Political Interest Groups , London : The University of Chicago Press .

- Offe , Claus . 1995 . “ ‘Some Skeptical Considerations on the Malleability of Representative Institutions’ ” . In Associations and Democracy , Edited by: Cohen , Joshua and Rogers , Joel . 114 – 132 . London : Verso .

- Olson , Mancur . 1965 . The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups , Cambridge , MA : Harvard University Press .

- Pollack , Mark A. 1997 . ‘Representing Diffuse Interests in EC Policy-making’ . Journal of European Public Policy , 4 ( 4 ) : 572 – 590 .

- Princen , Sebastiaan and Kerremans , Bart . 2008 . ‘Opportunity Structures in the EU Multi-level System’ . West European Politics , 31 ( 6 ) : 1129–46

- Putnam , Robert D. 2000 . Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community , New York : Simon & Schuster .

- Roose , Jochen . 2003 . “ ‘Umweltorganisationen zwischen Mitgliedschaftslogik und Einflusslogik in der europäischen Politik’ ” . In Bürgerschaft, Öffentlichkeit und Demokratie in Europa , Edited by: Klein , Ansgar , Koopmans , Ruud , Trenz , Hans-Jörg , Klein , Ludger , Lahusen , Christian and Rucht , Dieter . 141 – 158 . Opladen : Leske + Budrich .

- Salisbury , Robert H. 1969 . ‘An Exchange Theory of Interest Groups’ . Midwest Journal of Political Science , 13 ( 1 ) : 1 – 32 .

- Sandholtz , Wayne . 1992 . High-Tech Europe. The Politics of International Cooperation , Berkeley : University of California Press .

- Scarrow , Susan E. 2000 . “ ‘Parties without Members? Party Organization in a Changing Electoral Environment’ ” . In Parties Without Partisans: Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies , Edited by: Dalton , Russel J. and Wattenberg , Martin P. 79 – 101 . Oxford : Oxford University Press .