Abstract

Trilogues have been studied as sites of secluded inter-institutional decision making that gather the Council of the European Union, the European Parliament (EP) and the European Commission. Trilogues, however, are not exempt from formal and informal party-political dynamics that affect intra- and inter-institutional contestation. The increase in Eurosceptics in the 2014 EP elections offers an opportunity to investigate their efforts to shape the position and behaviour of the EP negotiating team in trilogues. Therefore, this article investigates to what extent Eurosceptic party groups participate in trilogue negotiations and how mainstream groups deal with their presence. The analysis shows that the opportunities to participate in trilogues and shape the EP’s position are higher for those perceived as soft Eurosceptic MEPs, while mainstream groups apply a ‘cordon sanitaire’ to those perceived as being part of hard Eurosceptic groups – which reduces the chances of MEPs from those groups being willing to participate in parliamentary work.

Since 2014, the European Parliament (EP) has experienced an increase in political polarisation, which has made day-to-day policy making more challenging. Indeed, the 2014 EP elections saw a notable rise in the number of Eurosceptic members (MEPs) and made it almost impossible to legislate along a left/right ideological divide. The pressure exerted at the extremes accentuates the culture of compromise and consensus that has emerged since the introduction of the co-decision procedure, which has seen an increase in cartel politics and the establishment of an informal ‘grand coalition’ between social democrats (S&D) and Christian democrats (European People’s Party, EPP) (Rose and Borz Citation2013; Ripoll Servent Citation2018). Therefore, since 2014, the EP has had to find ways of building a strong institutional position that can improve its chances in inter-institutional negotiations while facing an increased level of polarisation on the pro-/anti-European dimension.

At the same time, the need to find compromise between the two co-legislators in an efficient manner has shifted decision making to secluded fora in the form of trilogues – informal meetings during which representatives of the EP, the Council of the European Union (Council) and the European Commission (Commission) negotiate compromises. The effectiveness of trilogues has been so high, that, since 2009, around 90% of the concluded co-decision procedures have been adopted in first- or early second-reading agreements, with none of the files requiring the establishment of an inter-institutional conciliation committee (Brandsma Citation2015; European Parliament Citation2017). Despite their effectiveness, trilogues have often been criticised for their lack of transparency, which makes it difficult to attribute the authorship (and responsibility) of inter-institutional agreements. This is particularly problematic in the EP, since trilogues have shifted political conflict away from committees and the plenary – with the latter tending to rubberstamp political agreements brokered with the Council (Brandsma Citation2018; Rasmussen and Reh Citation2013; Reh et al. Citation2013).

The lack of transparency and the difficulty in accessing trilogues makes it hard to understand how political conflict plays out in inter-institutional negotiations. Generally, it has been assumed that trilogues act as battlefields where the Council, EP and Commission try to maximise their preferences under conditions of informality and seclusion (e.g. Costello Citation2011; Costello and Thomson Citation2013; de Ruiter and Neuhold Citation2012; Hagemann and Høyland Citation2010; Héritier and Reh Citation2012; Shackleton Citation2000). However, this assumption remains to be ascertained – especially in a context of increased intra-institutional polarisation, where mainstream groups in the EP might be closer to a majority in the Council than to fringe Eurosceptic parties in its midst. To this effect, this article examines to what extent Eurosceptic party groups participate in trilogue negotiations and how mainstream groups deal with their presence. We aim to understand under what conditions Eurosceptic MEPs are willing and/or able to shape the position of the EP in trilogue negotiations and how EP mainstream groups react to their presence in co-decision negotiations.

The article investigates formal and informal processes within the EP that underpin inter-institutional trilogue negotiations on the basis of élite interviews with MEPs and the EP, Commission and Council officials conducted in March 2017 and February, April and May 2018. It also draws on ethnographic data obtained during a stay in the European Commission and the European Parliament (October 2017–April 2018), in which one of the authors was able to observe trilogues as well as preparatory work in the EP in the form of committee and shadows meetings. We targeted actors closely involved in trilogues mainly representing mainstream views because we were mostly interested in how they perceive Eurosceptics and their role in intra- and inter-institutional negotiations. A list of interviewees is provided in the annex. The first part of the article situates trilogues and their impact on inter-institutional negotiations. It is followed by a second section discussing existing categorisations of Euroscepticism and Eurosceptic MEPs’ behaviour inside the EP. The third section offers an inductive analysis of Eurosceptic MEPs in trilogues, showing a differentiated picture on how these groups are perceived by mainstream groups. Our analysis reveals that, while those perceived as soft Eurosceptics are largely integrated into day-to-day legislative work, those MEPs perceived as being part of hard Eurosceptic groups are largely left out of legislative negotiations. The presence of an informal ‘cordon sanitaire’ affects in particular those MEPs who, despite being perceived as hard Eurosceptics, are still willing to participate pragmatically in parliamentary work. Therefore, we argue that the presence of a ‘cordon sanitaire’ has contributed to delineating a line between tolerable and intolerable Eurosceptics. The presence of a ‘cordon sanitaire’ shifts political conflicts away from trilogue negotiations and increases seclusion and informality within the EP.

Trilogue negotiations: organisation and interest formation

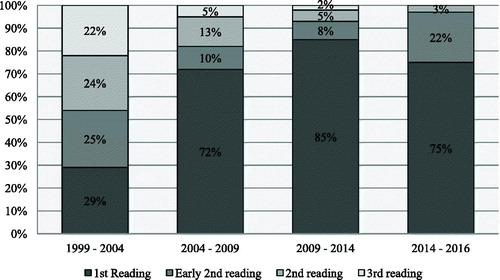

Trilogues originally developed as means to broker compromises between a smaller group of representatives from Parliament and Council to prepare the ground for an agreement in the conciliation committee (Huber and Shackleton Citation2013; Roederer-Rynning and Greenwood Citation2015; Shackleton Citation2000). With the increasing complexity and number of files decided under co-decision, trilogues were gradually introduced at earlier stages of the co-decision procedure, especially in the first reading stage, when the EP has not yet forwarded its opinion to the Council (Farrell and Héritier Citation2004). The use of trilogues has contributed to a steep rise in the number of early agreements (i.e. first- or early second-reading agreements), to the point that by 2016, the conciliation stage had become obsolete (Bressanelli et al. Citation2016; de Ruiter and Neuhold Citation2012; Rasmussen Citation2011; Rasmussen and Reh Citation2013; Reh Citation2014; Reh et al. Citation2013). Indeed, as shows, only 3% of files were adopted at second reading, with the majority of co-decision files agreed upon during first and early second reading. In the first half of the eighth EP term (2014–2016), 86 files were negotiated in 315 trilogues (European Parliament Citation2017: 20).

Figure 1. Co-decision files adopted between 1999 and 2016.

Source: European Parliament (Citation2017: 10).

Thus, trilogues now play an essential role in the legislative process. Although they are often referred to as being informal, secluded meetings – trilogues have no reference in the treaties – they are organised in a structured way. Despite the difficulty entailed in accessing trilogues, researchers have lately started to open up this black box. Notably, Roederer-Rynning and Greenwood (Citation2015) show that trilogues are organised in three layers: political trilogues, technical trilogues and bilateral meetings.1 For the purpose of this paper, political trilogues are the most interesting unit of analysis, as they comprise political representatives of the EP, Council and Commission, while technical trilogues involve technical (administrative) staff. The Council’s and Commission’s teams consist of fewer representatives compared to the EP negotiating team. The Council generally sends civil servants from the rotating Presidency, the Committee of Permanent Representatives (COREPER) and the Council Secretariat. The Commission team involves heads of unit or (deputy) director generals with supporting staff. Up to 30 people can represent the EP in political trilogues, including the committee chair, rapporteur, all shadow rapporteurs, sometimes EP vice-presidents and group coordinators or political advisors from the various groups (Roederer-Rynning and Greenwood Citation2015). The committee chair or the rapporteur preside over the negotiations, while the shadow rapporteurs, nominated by the remaining party groups, monitor the rapporteur and report back to their respective party groups but can also help to facilitate agreement between different groups (Farrell and Héritier Citation2004; Settembri and Neuhold Citation2009).

The EP negotiating team is equipped with a mandate from the responsible committee which marks the EP’s red lines in negotiations (Rule 69b). Over the years, the EP’s behaviour has been professionalised and institutionalised, especially when compared to the highly informal use of trilogues in the early 2000s. The EP’s Rules of Procedure have been modified at various points in time in order to provide committees with more control over the EP negotiating team. The 2016 reforms even gave the plenary the right to provide an ‘orientation vote’ if they felt that the EP team was not representing the EP as a whole in trilogue negotiations (Rule 69c).

The EP is often treated as a homogenous actor when trilogue negotiations are analysed. But as the overview provided here shows, MEPs from all political groups are involved in finding the EP’s position. Therefore, conflict between the different parliamentary actors is bound to occur, especially between committee chair and rapporteur as well as between representatives from bigger, mainstream groups and smaller, fringe groups. With the strengthening of Eurosceptic forces in the EP, it is particularly interesting to look at the interaction of Eurosceptic and mainstream party groups in the EP’s trilogue team: do Eurosceptic representatives participate in trilogues and, if so, how do they behave? How do mainstream actors deal with the presence of Eurosceptics in trilogues? Trilogues represent a special case to examine these interactions since, contrary to plenary and committees, they take place away from public scrutiny. Therefore, the secluded nature of trilogues may potentially reduce MEPs’ pressure to act according to an expected role, which in turn may result in different interactions between Eurosceptics and non-Eurosceptics. Also, while trilogue negotiations are about reaching an agreement with Council and Commission, the rapporteur needs to ensure that any deal is supported by the plenary and, therefore, profits when there is broad support from the other political groups. This gives the negotiating team more credibility and leverage and prevents possible inter-institutional coalitions, for example between unsatisfied shadow rapporteurs and the Council. Therefore, in trilogues, more than in committee or plenary, the behaviour and patterns of cooperation between Eurosceptic and non-Eurosceptic MEPs may be different than in other parliamentary fora.

Before discussing the role of Eurosceptic MEPs in trilogues, the next section shortly discusses Euroscepticism in the EP and the ideal-typical roles of Eurosceptic MEPs.

Eurosceptics in the EP: voting behaviour, coalitions and strategies

Eurosceptic parties achieved notable successes in the 2014 EP elections – the only exceptions being Luxembourg, Malta, Estonia, Slovenia and Romania; indeed, 201 seats out of 751 (that is 27%) in the EP belong to Eurosceptic MEPs (see Treib Citation2014). The composition of the Parliament changes considerably from election to election – especially regarding smaller, fringe or niche parties – and MEPs or whole national parties migrate from one party group to another. Therefore, an overview of Eurosceptic party groups in the current eighth parliamentary term (2014–2019) is given in , indicating also their main ideological line.

Table 1. Eurosceptic political groups in the eighth legislative term (2014–2019)–January 2019.

In the 2014 elections, the Eurosceptic right was the main winner: the ECR, for example, won 16 additional seats, making it the third largest group in the EP, while the EFDD could expand from 32 to 48 seats. Thus, Eurosceptics have become an important political force in the EP and should be expected to play a more significant role in day-to-day parliamentary work.

Following Taggart (Citation1998), Euroscepticism is understood here as the opposition or rejection of present and/or further European integration. Since this is a rather vague definition, researchers have attempted to classify Euroscepticism depending on how strongly parties or individuals pursue Eurosceptic goals. The most common typology of Euroscepticism is the one presented by Taggart and Szczerbiak (Citation2004), which distinguishes between hard and soft Euroscepticism. Hard Euroscepticism is the principled rejection of European political and economic integration that is ceding or transferring powers to EU institutions and opposition to a country joining or remaining in the European Union. Soft Euroscepticism, on the other hand, is contingent or qualified ‘opposition to the EU’s current or future planned trajectory based on the further extension of competencies that the EU is planning to make’ (Szczerbiak and Taggart Citation2008: 248). Soft Euroscepticism can manifest for example in opposition to specific policies intended for deepened political or economic integration. Other soft Eurosceptics insist on the importance of national interests trying to defend or stand up for it during debates or parliamentary work (Szczerbiak and Taggart Citation2008; Taggart and Szczerbiak Citation2004).2

While a categorisation of different nuances of Euroscepticism is important for an analysis of Eurosceptic parties and/or MEPs, it fails to explain Eurosceptics’ attitudes inside the EP, especially when it comes to voting behaviour, coalition formation or their behaviour in plenary compared to committees (Almeida Citation2010; Brack Citation2015; Vasilopoulou Citation2013; Whitaker and Lynch Citation2014). Brack has filled this gap by developing a typology of Eurosceptic MEPs based on their different approaches to parliamentary work (Brack Citation2013, Citation2015; Costa and Brack Citation2009). This typology classifies Eurosceptic MEPs into public orators, absentees, pragmatists and participants. Public orators focus on speeches in plenary and the distribution of negative information. They are opposition speakers trying to disseminate and defend their anti-EU position: always present during plenary debates but not interested in day-to-day parliamentary activities such as committee work. As a result, they are de facto excluded from EP work and concentrate mostly on the national arena. Absentees also focus on the national arena and their voters but, unlike public orators, they are rarely involved inside the EP. They participate neither in plenary debates nor in delegation or committee work. Pragmatists try to strike a balance between their Eurosceptic view and the wish to achieve concrete results. They decide on a case-by-case basis whether they want to become engaged but, if so, they respect the EP rules and sometimes exercise positions of responsibility or even draft reports. The most closely involved, however, are the participants. They are (or pretend to be) willing to integrate into the Parliament like any other MEP. Participants adopt a constructive approach, and know and respect formal as well as informal EP rules. Thus, participants not only use questions and speeches but also draft more opinions and reports compared to the other three types.

These four ideal types focus on MEPs’ behaviour in plenary and committees, rather than legislative negotiations. However, we do not know whether these ideal-types also apply to Eurosceptic MEPs in trilogues. The secluded nature of inter-institutional negotiations may lead Eurosceptic MEPs to behave differently, as no public proof of their behaviour (such as minutes or similar published documents) gets out to their voters. Consequently, the interactions with mainstream MEPs might be different compared to public parliamentary work. Therefore, we take Taggart and Szczerbiak’s as well as Brack’s work as a starting point and use an inductive approach building on ethnographic and interview data to examine and understand Eurosceptic MEPs’ behaviour in trilogue negotiations and how mainstream MEPs deal with them in day-to-day legislative work.

Eurosceptic MEPs in trilogues: drawing a more nuanced picture

As we have seen in the previous section, we need to distinguish between different types of Eurosceptic MEPs; their behaviour depends largely on their role perception, which leads some of them to take a more active interest in the work of the Parliament, while some are largely absent. All interviewees pointed to the fact that it would be erroneous to treat Eurosceptic party groups as a unified category when analysing their behaviour. Their attitude varies from party group to party group, national party to national party and sometimes even from MEP to MEP (interviews 3, 4, 5, 7, 8 and 9). In addition, their involvement strongly depends on specific cases and policy fields. Many interviewees observed that Eurosceptics often do not participate or interact with others in the negotiations (interviews 3 and 8), nor do they participate in shadows meetings and preparations in committees, and there was agreement that the overall level of participation in trilogues by Eurosceptics is low. However, some remarked that, when negotiations touch upon areas where Eurosceptic MEPs have a personal interest, they often exercise their right as shadows to participate (interview 5). MEP Peter Lundgren is such an example: a member of the right-wing Sweden Democrats, he joined the EFDD and just recently changed to ECR. As a former lorry driver in the Transport and Tourism (TRAN) committee, he has a personal interest in transport policies. Therefore, his points are heard by his co-shadow rapporteurs and he is seen as a valid interlocutor due to the expertise provided by his former professional career (interview 13).

Beyond this variation on the individual level, we see some patterns across Eurosceptic groups. When it comes to soft Eurosceptic groups like the ECR and the GUE/NGL, their MEPs adopt mostly a participant role. The GUE/NGL plays a constructive role during trilogues, sending shadow rapporteurs to most trilogues and sometimes even holding rapporteurship (interviews 7 and 9). While one interviewee pointed to the fact that the GUE/NGL shadow rapporteurs are quite quiet during trilogues (interview 9), this seems to be related to the professionalization of trilogues rather than to an attempt to show their rejection of EU politics. Generally, rapporteurs tend to speak for the EP as a whole and shadows remain silent (see the next section for further discussion on this point). Regarding the ECR, they are seen as a constructive group used to shaping proposals (interview 11). One interviewee described them as ‘legitimate, democratic and constructive in the preparation of trilogues’ (interview 8). This assessment is reflected in the fact that the ECR supervises reports more often than the other right-wing Eurosceptic party groups (interview 3; see ).

Table 2. Co-decision reports allocated to Eurosceptic groups (2014–2018).

In comparison, hard Eurosceptic groups present more interesting patterns of behaviour – especially in the case of the EFDD. The latter functions as a technical group where the two dominant parties – the Italian Five Star Movement (M5S) and the UK Independence Party (UKIP) – only cooperate in order to profit from the advantages that political groups enjoy in the EP. Its behaviour is characterised as peculiar compared to the other groups (interviews 7 and 8), with a clear difference between a harder Eurosceptic pro-Brexit UKIP and a softer M5S, whose MEPs do not want to leave the EU but rather change its organisation and orientation (interview 7). The M5S parliamentarians were described as highly qualified MEPs interested in the EP’s work and generally present in trilogues; they hold many committee memberships and sometimes even oversee reports (interviews 5 and 9; see also ). One Council official said that the M5S MEPs’ approach in trilogues is quite idealistic but that they are committed to work constructively with the other negotiating parties on files in which they have an interest (interview 9). Nevertheless, an EP staffer – working for a big political group – complained that their reports ‘set off crises in our group’ (interview 5) – meaning that M5S MEPs are motivated but often use their reports to make a point or prepare technically poor drafts. An M5S rapporteur dealing with a highly salient file was described as ‘weak’, due to constantly shifting her political positions; her membership of the M5S was seen as ‘not helpful’ and made it easier for mainstream shadow rapporteurs to question her and take over her job as rapporteur (interviews 10 and 12). Nevertheless, M5S MEPs mostly behave as pragmatists and participants.

In contrast, UKIP and the ENF groups generally adopt a classical public orator role. While they are present in the plenary, making noise and voicing their opinion, they seldom take part in trilogue preparations and negotiations (interviews 2, 5, 7, 8 and 9). Of the currently 19 UKIP EFDD members, only two have been nominated as shadow rapporteurs. Public orator MEPs are mostly not involved in trilogues although they do not try to obstruct them. One official described the ENF’s attitude in trilogues as a ‘complete refusal of negotiations’ (interview 8), while an EP staffer reported that the chair of Lega Nord never attended or voted on opinions although he was in charge of the ENF (interview 6). A Commission official, who has regular contact with political advisors from all party groups, affirmed that, while EFDD advisors are not as interested as mainstream party groups’ advisors, he never had contact with the ENF’s advisor because he was never present at meetings; furthermore, the UKIP advisor responsible for an international trade (INTA) trilogue never attended any meetings (interview 7).

This attitude, however, sometimes turns into a dilemma for hard Eurosceptic public orators. One interviewee illustrated this situation using the example of the revision of the Posted Workers Directive (interview 4): despite their unwillingness to involve themselves with the parliamentary work of the EP, the French Front National (FN) decided to name a shadow rapporteur to follow this specific negotiation, since it was seen to be highly important for French voters. This nomination shows the trade-off that hard Eurosceptics sometimes face: they either have to abandon their principles by involving themselves in the work of an institution that they see as illegitimate or they have to decide not to participate in negotiations and face the electoral damage that other French parties may inflict, by accusing them of refusing to do something in favour of the people they claim to represent.

In sum, although it is difficult to find direct connections between the level of Euroscepticism in political groups and the roles adopted by their MEPs, we can see some trends in how they approach shadows meetings and trilogues. While public orators are not present in negotiations, concentrating on voicing their opinions in plenary, MEPs with pragmatist and participant attitudes are more actively involved in trilogues, trying to influence their course, cooperating and sometimes even holding a rapporteurship. At the same time, we need to differentiate, especially within the EFDD group, where the right wing of the group (UKIP) adopts harder positions and behaviour than the left wing (M5S), whose MEPs tend to be more willing to participate in trilogue negotiations.

Mainstream party groups’ perceptions of Eurosceptic MEPs

As we have seen before, the presence of Eurosceptics is important in order to understand intra- and inter-institutional processes of coalition-building. Tighter majorities and higher levels of polarisation make it more difficult for the EP to stand behind a unified position. However, how do mainstream groups perceive and deal with Eurosceptic MEPs in day-to-day legislative work? This is an important question given that the EP faces conflicting pressures: on the one hand, since the 2014 elections, it has become more polarised and finds it more difficult to build stable majorities; on the other hand, the EP is under pressure to reach solid intra-institutional agreements that represent a majority in the chamber if it wants to have better chances in trilogues. If the EP is united behind a single position, it is usually more difficult for the Council to develop strategies of ‘divide and conquer’, whereby it attempts to create divisions within the EP in order to win over some of its members to form inter-institutional coalitions. In addition, presenting a unified front makes it more difficult for the Council to rhetorically and normatively oppose the EP, since the latter can always play on its legitimacy as representative of EU citizens to force the Council’s hand (Trauner and Ripoll Servent Citation2016).

The diverse composition of the EP negotiating team compared to those of the Council and the Commission is a double-edged sword: the presence of a bigger team can be an advantage, since it can outnumber the other institutions, but it also reflects more diverse political interests (interview 6). In the past, this led to open conflicts between the EP’s negotiators in front of the two other institutions, which weakened its performance in trilogues (interview 9). Since then, various reforms to its Rules of Procedure have sought to make the pre-negotiation process better organised, more prepared and thus more professionalised (interviews 6 and 9). As a result, EP representatives try to appear as one united bloc and, in case of disagreement between members of the EP negotiating team, they tend to take a break during negotiations in order to find a solution, instead of fighting openly before the other EU institutions (interviews 1, 5 and 6). Therefore, there is a growing shared understanding that the EP’s negotiating team should represent the entire Parliament; this means that rapporteur, chair and shadow rapporteurs all have to accept the given mandate even if it might conflict with their personal view or the opinion of their political group (interviews 4, 5 and 7). As one interviewee summarised it: ‘once the EP’s position is set, it’s set’ (interview 7).

This development in the EP’s attitude does not leave room for open conflicts and interest formation in the negotiating team during trilogues. Therefore, although it is the shadow rapporteurs’ task to control the rapporteur, it has become clear that they should not wait until trilogues to present a diverging opinion (interviews 1, 5 and 6). To secure a smooth cooperation in trilogues and to make sure that the EP representatives all support the mandate, the EP has developed new working practices, which allow the negotiating team to prepare its positions in so-called ‘shadows meetings’ before going into trilogues (interviews 1, 4 and 6). It is in these meetings that the rapporteur(s) and shadow rapporteurs negotiate and voice their different opinions in order to resolve any major conflict between the political groups. As a result, it has become easier to represent Parliament in trilogue meetings, since nowadays it is generally accepted that the rapporteur should act as chief negotiator, while the committee chair is in charge of presiding. The shadow rapporteurs are there to support and control, but normally keep to the side-lines and do not interfere in the negotiations (see, however, Roederer-Rynning and Greenwood Citation2017 for more detail on the role of committee chairs in trilogues). The intra-institutional contestation has thus shifted to the committees and especially to the shadows meetings, which have become more important fora for analysing interest formation and political conflict than trilogues themselves.

What does it mean, in practice, for Eurosceptic groups to stand behind a single EP position? How much can they actually shape it? The opportunities are different depending on whether these groups are perceived as hard or soft Eurosceptics. As we have seen in the previous section, soft Eurosceptics like the ECR and GUE/NGL are seen as pragmatists or participants, which means that they take part in trilogues and do so in a cooperative or at least non-obstructive way (interviews 1, 5 and 9). These types of Eurosceptic MEPs are not ipso facto excluded from the process of forming a unified position. In shadows meetings, all minority opinions that are voiced are heard and discussed (interviews 5 and 7) and some of them participate very actively – often stressing issues like the principle of subsidiarity or the positions of their member states (interview 3). Therefore, the participation of ECR and GUE/NGL in parliamentary work is largely accepted by mainstream groups. Indeed, soft Eurosceptic groups have become even more integrated since the (informal) ‘grand coalition’ that had been formed after the 2014 EP elections was declared dead at the beginning of 2017 (Euobserver Citation2017). As a result, the EPP and Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE) do tend to see the ECR as a legitimate coalition partner, while the S&D often includes the GUE/NGL in left-wing coalitions (interviews 1, 2 and 8).

In contrast, this legislative term has seen the continuation and increase in parliamentary practices developed by mainstream groups to avoid the involvement of hard Eurosceptics in leadership structures and legislative work. For instance, when committee chairs were allocated at the start of the legislature, the EFDD was supposed to get the chairmanship of the Petitions committee, but its members ‘revolted’ against the idea and voted instead for an ALDE MEP (Politico 2014). Similarly, mainstream groups have managed to exclude hard Eurosceptics from the EP’s vice-presidencies, which means that they are not represented in the Bureau and, therefore, are excluded from crucial political discussions. The EPP’s chair (Manfred Weber) even proposed to create an informal ‘G6’ group (gathering the chairs of all political groups except for the EFDD and the ENF) outside the formal structure of the Conference of Presidents, so that hard Eurosceptic groups could be excluded from discussions on key political decisions (Politico Citation2017).

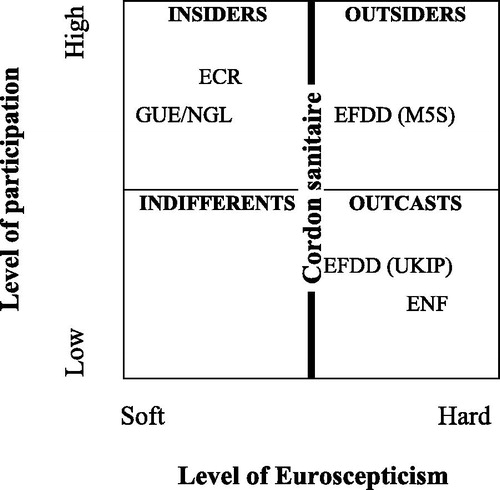

This practice of a ‘cordon sanitaire’ also extends itself to legislative work, where mainstream parties try to prevent Eurosceptics from gaining too much influence, for instance by preventing them from getting an important role in trilogues (see ).

Particularly when it comes to files that are perceived as important by the EP, the largest groups want to keep them in progressive hands, so that it is easier to find a compromise that furthers European integration (interviews 2, 5 and 8). As a Council official, who works closely with the EP, explained: ‘the “cordon sanitaire” works. It is reality but not relevant because the big groups try to isolate Eurosceptics’ amendments’ (interview 9) – a practice affirmed by other interviewees to varying degrees. The behaviour is also reflected in shadows meetings: although hard Eurosceptics are not isolated due to their political positions, mainstream political groups react to the stronger presence and involvement of Eurosceptics in the EP and in trilogues – for instance, by categorically rejecting ENF and EFDD proposals as common practice (interview 8). One MEP assistant (interview 13) described the case of an ENF MEP being rapporteur for an opinion:

It was a really intricate manoeuvring. The S&D rejected everything. The [S&D shadow] didn’t want to come to any meeting. It was a complete refusal. ALDE tried to treat the rapporteur normally, while the EPP hummed and hawed. It was not a contentious topic. In parts it was abstruse, confused and also embarrassing for the established party groups and it gives the ENF the legitimate accusation that they are ostracised.

Thus, the insights from the data suggest that depending on how Eurosceptic MEPs are perceived, mainstream groups either cooperate with them or try to exclude them from forming an EP trilogue position.

Discussion

The inductive analysis of our ethnographic and interview data revealed that while soft Eurosceptics like the ECR and GUE/NGL were generally characterised as cooperative, interested and involved in shadows meetings and trilogue preparations, most hard Eurosceptics from the ENF and the EFDD were characterised as absent and not interested in trilogue work. When it comes to the reaction of mainstream groups, we see that, in a context where it has become more difficult to build alliances beyond a ‘grand coalition’, the largest groups cannot dismiss soft Eurosceptics as coalition partners, as they would deprive themselves of important allies in the process of building coalitions. The EPP therefore tries first to forge alliances with the liberals and the ECR, while the S&D tries to coalesce with the party groups on the left, including GUE/NGL. They are more reticent to expand this behaviour to party groups they perceive as hard Eurosceptic.

At the same time, our examination suggests that the picture of hard Eurosceptic groups is more nuanced than usually depicted, especially when we look at the EFDD group: most M5S MEPs were characterised as either pragmatists or participants. This is an important finding, since it underlines the necessity to apply a more fine-grained analysis of Eurosceptic groups and to examine potential differences within each political group. If we go back to the typologies discussed at the beginning of the article, we see that the patterns which occur when it comes to the behaviour of Eurosceptic MEPs in plenary or committees are similar in trilogues: absentees are absent from parliamentary life, which includes also trilogues and any preparation work. In comparison, while public orators are active in parliamentary arenas that give them voice, they do not see any interest in work done ‘behind the scenes’ and are generally absent from trilogues. Absentee and public orator MEPs can, thus, be bracketed in one group when looking at trilogues. In comparison, pragmatists and participants do take an interest in parliamentary life and are thus active in trilogues (interviews 7, 8, 9 and 11).

Based on these findings, we propose a typology of Eurosceptic MEPs in trilogues based on mainstream party groups’ perceptions () and use it to draw four different types of Eurosceptic MEPs in trilogue settings based on their different approaches to parliamentary work.

While ENF and UKIP MEPs use their positions to voice their opinions in plenary, they find no interest in participating in trilogues. Without published minutes or media attention, public orators are deprived of their most important means to obstruct EP procedures. Combined with the use of a ‘cordon sanitaire’, they become (willing) ‘outcasts’ from trilogue negotiations. In comparison, pragmatists or participants do involve themselves more intensely in parliamentary work. Since trilogues have become central to EU policy making, they accept that, in order to change things, they need to engage with them and thus participate actively in shadow and committee meetings. Although there certainly might exist cases of low-participating soft Eurosceptics, there does not seem to be a generalised perception of this specific type of ‘indifferent’ Eurosceptic as a separate category among mainstream groups. However, we do see how the ‘cordon sanitaire’ acts as a dividing line between those perceived as soft Eurosceptics, seen as legitimate ‘insiders’ fully integrated in the system, and MEPs who are perceived as hard Eurosceptics.

Nevertheless, the practice of a ‘cordon sanitaire’ has different consequences for different types of hard Eurosceptics. It is, probably, not so problematic for those adopting the role of an absentee or a public orator, since they do not participate in most legislative negotiations in any case. When they do try to participate, their efforts are generally not successful – either through an active effort from mainstream MEPs to exclude them or because they do not know how to participate effectively in parliamentary work. For instance, a member of staff of a mainstream party group gave the example of an ENF report that was voted down. As she explained, it was not voted down because it was from a hard Eurosceptic group, but because the report itself was badly written and was just used to make a point. As she put it: ‘Eurosceptics don’t accept the rules of the game. What do you expect? They knew their report would be voted down’ (interview 2).

This example leads to the conclusion that, particularly hard Eurosceptic public orators are not interested in actually participating; they use the rare opportunities when they have a rapporteurship to underpin their positions instead of using it to actively change something. Engaging with legislative work in a constructive manner is not in their interest as they would have to take responsibility for their actions on the EU level (interview 6), which goes against their core political principles. Therefore, the analysis of the data leads to the conclusion that the use of a ‘cordon sanitaire’ focuses in particular on those that act as public orators and use legislative negotiations to make a point or even undermine the EP’s position in trilogues.

This raises a question about those hard Eurosceptics who actually adopt a pragmatist or participant role and would like to participate in trilogue negotiations. As we have seen above, most interviewees agreed that many MEPs from the EFDD – especially those from the M5S – are cooperative and not refusing or obstructing cooperation. Indeed, as shows, out of the nine files led by the EFDD, eight were allocated to a MEP from the M5S. The question is, whether they are also affected by the ‘cordon sanitaire’ and therefore not taken into consideration; even if they do want to effectively participate in legislative work. Two interviews with EFDD staff suggest that this is not the case. If the EFDD has a valid point it will be taken into account in the amendments, but only as long as the big groups do not object. Overlap between an EFDD suggestion with another group’s amendment facilitates their participation (interviews 14 and 15). In many cases, they are treated as ‘outsiders’ – allowed to participate but not seen as trusted partners and thus are more likely to be excluded and bypassed if they do not contribute constructively to building a common EP position.

Conclusion

This article has presented an analysis of Eurosceptic MEPs’ behaviour in trilogues and how mainstream political groups react to higher levels of polarisation. To this end we used Taggart and Szcerbiak’s (2004; Szczerbiak and Taggart Citation2008) differentiation between soft and hard Euroscepticism and combined it with Brack’s (Citation2013, Citation2015) four ideal-types of Eurosceptic MEPs as a starting point for an inductive examination of Eurosceptic MEPs in trilogues. The analysis revealed that pragmatist or participant Eurosceptic MEPs are present and actively involved in trilogues; Eurosceptic MEPs acting as public orators or absentees do not participate in trilogues or even try to disrupt them. When it comes to the reactions of mainstream groups, we suggest that only soft Eurosceptics are seen as legitimate partners in intra-institutional negotiations, while mainstream MEPs exclude hard Eurosceptics from trilogue negotiations in order not to give them a platform to propagate their views. The M5S group in the EFDD presents a special case, since they are willing to involve themselves in trilogues and shadows meetings but are often treated as outsiders. This is an important finding, since it underlines the necessity to apply a more fine-grained analysis of Eurosceptic groups and to examine potential differences within each political group.

The analysis also revealed that most of the process of interest formation inside the EP negotiating team happens during shadows meetings, which are largely unexplored in the literature. It is there that shadow rapporteurs can more easily steer the mandate in their preferred direction. We therefore need to examine further how conflicts are resolved in these preparatory meetings, how much room is given to minority opinions and whether it makes any difference when it comes to these different types of Eurosceptics: do outsiders manage to overcome their status in preparatory meetings through their individual behaviour? Or are they also perceived as unreliable (or even illegitimate) participants in these meetings?

In addition, the proclaimed end of the ‘grand coalition’ between EPP, S&D and ALDE and the upcoming European elections in 2019 may have implications for how political conflict is managed in the EP (interviews 1, 2 and 8). Although some did not expect to see major changes (interviews 6 and 9), we need to observe whether new patterns of coalition-building emerge and whether the larger groups (EPP and S&D) are pushed to cooperate more often with soft Eurosceptics from the ECR and GUE/NGL. This might have consequences not just for inter-group coalition patterns but also for intra-group dynamics, since it might bolster Eurosceptic delegations within mainstream groups. Indeed, it would be equally important to examine the presence of Eurosceptic MEPs in mainstream groups, such as the Hungarian Fidesz party in the EPP group. This would allow us to evaluate which type of behaviour they adopt and to what extent it is comparable to that of insiders or whether there are also patterns of exclusion within mainstream groups, whereby certain delegations are treated as outsiders and excluded from legislative work.

These questions are important, since they relate to the capacity of the EP to manage increasing levels of politicisation and political conflict in the EU and to represent a more diverse and polarised European citizenry. Therefore, while practices like the ‘cordon sanitaire’ might be seen as pragmatic and legitimate by mainstream political groups (and voters), they might contribute to the alienation of certain sectors of society and increase the perception of a gap in the representativeness (and legitimacy) of the European Parliament.

List of interviews

European Parliament:

Interview 1 (2 EP staff, 2017)

Interview 2 (EPP group, 2017)

Interview 3 (ALDE MEP assistant, 2017)

Interview 4 (MEP, 2017)

Interview 5 (S&D group, 2017)

Interview 6 (EP staff, 2017)

Interview 8 (EP staff, 2017)

Interview 10 (GUE/NGL MEP assistant, 2017)

Interview 11 (ALDE MEP assistant, 2017)

Interview 12 (Greens/EFA group, 2017)

Interview 13 (ALDE MEP assistant, 2018)

Interview 14 (EFDD policy advisor, 2018)

Interview 15 (EFDD MEP assistant, 2018)

Council: Interview 9 (Council official, 2017)

Commission: Interview 7 (Commission official, 2017)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants at the European Union Studies Association (EUSA) conference in Miami, the University Association for Contemporary European Studies (UACES) conference in Bath and the Deutsche Vereinigung für Politikwissenschaft (DVPW) conference in Frankfurt (Main) for their comments as well as the team of the TRILOGUES project for their feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ariadna Ripoll Servent

Ariadna Ripoll Servent is Junior Professor of Political Science and European Integration at the University of Bamberg and visiting professor at the College of Europe, Bruges. Her research interests focus on decision making in the EU, with an emphasis on institutional and policy change. She has published widely on the role of the European Parliament and the area of freedom, security and justice. [[email protected]]

Lara Panning

Lara Panning is a PhD candidate and research fellow in Political Science and European Politics at the University of Bamberg. Her research interests focus on EU institutions, especially the European Parliament and Commission, informal negotiation processes within the institutions as well as the rise of populism and Euroscepticism. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 Interestingly, several interviewees objected to the use of the term technical trilogues. They explained that trilogues are always political, while what Roederer-Rynning and Greenwood call technical trilogues are termed technical meetings (Interviews 1 and 9).

2 For other, more fine-grained categorisations see, for example, Kopecký and Mudde (2002), who distinguish between Euroenthusiasts, Europragmatists, Eurosceptics and Eurorejects, or Costa and Brack (2009), who suggest anti-EU, minimalist, reformist and resigned. Flood and Usherwood (2005) talk about maximalists, reformists, gradualists, minimalists, revisionists and rejectionists, ranging from unconditioned support for further EU integration to principled opposition to EU membership. These categories go beyond the scope of our present study and therefore we have limited ourselves to the more parsimonious definition offered by Taggart and Szczerbiak.

References

- Almeida, Dimitri (2010). ‘Europeanized Eurosceptics? Radical Right Parties and European Integration’, Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 11:3, 237–53.

- Brack, Nathalie (2013). ‘Euroscepticism at the Supranational Level: The Case of the “Untidy Right” in the European Parliament’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 51:1, 85–104.

- Brack, Nathalie (2015). ‘The Roles of Eurosceptic Members of the European Parliament and Their Implications for the EU’, International Political Science Review, 36:3, 337–50.

- Brandsma, Gijs Jan (2015). ‘Co-Decision after Lisbon: The Politics of Informal Trilogues in European Union Lawmaking’, European Union Politics, 16:2, 300–319.

- Brandsma, Gijs Jan (2018). ‘Transparency of EU Informal Trilogues through Public Feedback in the European Parliament: Promise Unfulfilled’, Journal of European Public Policy. DOI: 10.1080/13501763.2018.1528295.

- Bressanelli, Edoardo, Christel Koop, and Christine Reh (2016). ‘The Impact of Informalisation: Early Agreements and Voting Cohesion in the European Parliament’, European Union Politics, 17:1, 91–113.

- Costa, Olivier, and Nathalie Brack (2009). ‘The Role(s) of the Eurosceptic MEPs’, in Dieter Fuch, Raul Magni-Berton, and Antoine Roger (eds.), Euroscepticism. Images of Europe Among Mass Publics and Political Elites. Opladen: Barbara Budrich Publishers, 253–271.

- Costello, Rory (2011). ‘Does Bicameralism Promote Stability? Inter-institutional Relations and Coalition Formation in the European Parliament’, West European Politics, 34:1, 122–144.

- Costello, Rory, and Robert Thomson (2013). ‘The Distribution of Power among EU Institutions: Who Wins under Codecision and Why?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 20:7, 1025–1039.

- Euobserver (2017). ‘Socialist MEPs seek new role after grand coalition’, February 17. https://euobserver.com/news/136933 (Accessed 28 February 2017).

- European Parliament (2017). ‘Activity Report on the Ordinary Legislative Procedure: 4 July 2014–31 December 2016’.

- Farrell, Henry, and Adrienne Héritier (2004). ‘Interorganizational Negotiation and Intraorganizational Power in Shared Decision Making: Early Agreements Under Codecision and Their Impact on the European Parliament and Council’, Comparative Political Studies, 37:10, 1184–1212.

- Flood, Christopher, and Simon Usherwood (2005). ‘Positions, Dispositions, Transitions: A Model of Group Alignment on EU Integration’, in 55th Annual Conference of the Political Studies Association, University of Leeds.

- Hagemann, Sara, and Bjørn Høyland (2010). ‘Bicameral Politics in the European Union’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 48:4, 811–833.

- Héritier, Adrienne, and Christine Reh (2012). ‘Codecision and Its Discontents: Intra-Organisational Politics and Institutional Reform in the European Parliament’, West European Politics, 35:5, 1134–1157.

- Huber, Katrin, and Michael Shackleton (2013). ‘Codecision: A Practitioners’ View from Inside the Parliament’, Journal of European Public Policy, 20:7, 1040–1055.

- Kopecký, Petr, and Cas Mudde (2002). ‘The Two Sides of Euroscepticism: Party Positions on European Integration in East Central Europe’, European Union Politics, 3:3, 297–326.

- Politico (2016). ‘EFDD Loses out as Groups Share the Spoils’. July 7 http://www.politico.eu/article/members-of-parliaments-committees-choose-their-leaders/ (Accessed August 4, 2016).

- Politico (2017). ‘Germany’s Weber wants a “G6” to push out the populists’. February 14 http://www.politico.eu/article/manfred-weber-wants-a-g6-to-push-out-populists-european-parliament/ (Accessed February 27, 2017).

- Rasmussen, Anne (2011). ‘Early Conclusion in Bicameral Bargaining: Evidence from the Co-decision Legislative Procedure of the European Union’, European Union Politics, 12:1, 41–64.

- Rasmussen, Anne, and Christine Reh (2013). ‘The Consequences of Concluding Codecision Early: Trilogues and Intra-Institutional Bargaining Success’, Journal of European Public Policy, 20:7, 1006–1024.

- Reh, Christine (2014). ‘Is Informal Politics Undemocratic? Trilogues, Early Agreements and the Selection Model of Representation’, Journal of European Public Policy, 21:6, 822–841.

- Reh, Christine, Adrienne Héritier, Edoardo Bressanelli, and Christel Koop (2013). ‘The Informal Politics of Legislation: Explaining Secluded Decision Making in the European Union’, Comparative Political Studies, 46:9, 1112–1142.

- Ripoll Servent, Ariadna (2018). The European Parliament. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Roederer-Rynning, Christilla, and Justin Greenwood (2015). ‘The Culture of Trilogues’, Journal of European Public Policy, 22:8, 1148–1165.

- Roederer-Rynning, Christilla, and Justin Greenwood (2017). ‘The European Parliament as a Developing Legislature: Coming of Age in Trilogues?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 24:5, 735–754.

- Rose, Richard, and Gabriela Borz (2013). ‘Aggregation and Representation in European Parliament Party Groups’, West European Politics, 36:3, 474–497.

- de Ruiter, Rik, and Christine Neuhold (2012). ‘Why Is Fast Track the Way to Go? Justifications for Early Agreement in the Co-Decision Procedure and Their Effects’, European Law Journal, 18:4, 536–554.

- Settembri, Pierpaolo, and Christine Neuhold (2009). ‘Achieving Consensus Through Committees: Does the European Parliament Manage?’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 47:1, 127–151.

- Shackleton, Michael (2000). ‘The Politics of Codecision’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 38:2, 325–342.

- Szczerbiak, Aleks, and Paul Taggart (eds.) (2008). Opposing Europe?: The Comparative Party Politics of Euroscepticism: Volume 1: Case Studies and Country Surveys. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Taggart, Paul (1998). ‘A Touchstone of Dissent: Euroscepticism in Contemporary Western European Party Systems’, European Journal of Political Research, 33:3, 363–388.

- Taggart, Paul, and Aleks Szczerbiak (2004). ‘Contemporary Euroscepticism in the Party Systems of the European Union Candidate States of Central and Eastern Europe’, European Journal of Political Research, 43:1, 1–27.

- Trauner, Florian, and Ariadna Ripoll Servent (2016). ‘The Communitarization of the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice: Why Institutional Change Does not Translate into Policy Change’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 54:6, 1417–1432.

- Treib, Oliver (2014). ‘The Voter Says No, but Nobody Listens: Causes and Consequences of the Eurosceptic Vote in the 2014 European Elections’, Journal of European Public Policy, 21:10, 1541–1554.

- Vasilopoulou, Sofia (2013). ‘Continuity and Change in the Study of Euroscepticism: Plus ça change?’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 51:1, 153–168.

- Whitaker, Richard, and Philip Lynch (2014). ‘Understanding the Formation and Actions of Eurosceptic Groups in the European Parliament: Pragmatism, Principles and Publicity’, Government and Opposition, 49:2, 232–263.