Abstract

This article analyses patterns in interest group access to the political process in the Netherlands from 1970 to 2017. Research has indicated that corporations are amongst the most frequent participants in contemporary political systems. Yet such research has had a strong focus on the US, leaving a gap in our knowledge of corporate lobbying within Europe. This study demonstrates for the first time in a European context that, in contrast to several decades ago, corporations have managed to increase their access to the political process. In doing so, the article tests a new approach that identifies large-scale interest group populations. The method shows itself to be reliable and can therefore be useful for other scholars. The explanatory model indicates that corporate access increases when the economy weakens and political opportunities increase. Overall, the article demonstrates that business interests have managed to expand their access, contributing to a fragmented interest group system.

Keywords:

Why do corporations increasingly participate in the political process on their own behalf? This question is important because if interest representation of the business community takes place via associations, the interests need to be accommodated among members and ‘encompassing associations tend to focus members’ attention on broader shared concerns and collective ambitions’ (Gray et al. Citation2004; Martin Citation2005; Martin and Swank Citation2004: 598; Wilson Citation1973: 310). Instead, when corporations increasingly lobby on their own behalf (see Gray and Lowery Citation2001; Gray et al. Citation2004; Madeira Citation2016), they can represent their interests through minimal liaison with peers, leading to interests that are overall less moderate, narrower and more self-oriented (Hart Citation2004; Salisbury Citation1984). An increase in individual corporate lobbying thus has important consequences for the functioning of political systems, as it causes bias through the fragmentation of interest systems (Gray et al. Citation2004: 20). With this in mind, it is worrisome that most studies now highlight that individual corporations constitute the largest set of actors in interest group communities across many Western democracies (Baumgartner and Leech Citation2001; Berkhout et al. Citation2018; Chalmers Citation2013; Lowery et al. Citation2005; Salisbury Citation1984; Schlozman Citation1984).

In this article we aim to find out what has caused this shift towards increased corporate access to the political process. The study contributes to the literature in three ways. First, theoretically, the current literature has addressed questions on drivers of corporate lobbying by conducting research at different levels of analysis. We identify three main explanatory perspectives, each associated with the level of analysis of these studies: an organisational, a sector, and a structural perspective (e.g. Bernhagen and Mitchell Citation2009; Boies Citation1989; Bouwen Citation2002; Coen Citation1997; Grant et al. Citation1989; Gray et al. Citation2004; Grier et al. Citation1994; Lowery and Gray Citation1998; Salisbury Citation1984; Walker and Rea Citation2014). The first two perspectives have received most attention in that they produced both appealing theoretical arguments and empirical tests to validate the arguments. The latter perspective, nonetheless, has received far less scholarly focus. Whilst several scholars certainly recognise the importance of structural changes for lobbying activity of corporations such as variation in the economy and political systems (Bernhagen and Mitchell Citation2009; Lowery and Gray Citation1998), their ideas are hardly empirically tested. As a result, we do not exactly know to what extent corporations have replaced other types of organised interests at the political negotiation table over time, let alone which structural factors have caused such shifts. To fill this void, this paper therefore carefully maps the extent to which corporations have gained access to the political system over time, as well as it theoretically develops and tests structural factors that could affect such access. More precisely, we develop hypotheses associated with several economic and political-institutional changes that could affect the extent to which corporate actors – relative to other types of organised interests – over time gain access to politics.

The second contribution of this article is our empirical focus. Most of the current studies on corporate access either focus on lobbying in a US context (e.g. Boies Citation1989; Lowery and Gray Citation1998; Salisbury Citation1984; Schlozman Citation1984) or towards the European Union institutions (Bernhagen and Mitchell Citation2009; Bouwen Citation2004; Coen Citation1997). This means that most of the academic endeavours on corporate lobbying were carried out in a distinct pluralist system such as the United States, or an ‘elitist pluralist system’ such as the European Union (Chalmers Citation2013: 484; Eising Citation2007: 384). We therefore know little about corporate lobbying in a more corporatist setting. This article seeks to fill this gap through expanding the empirical focus by studying the Netherlands, a country that is characterised as neo-corporatist (Streeck and Kenworthy Citation2005). This is an important addition as it adds to our knowledge on possible biases toward business interests in contexts outside of the US or towards the EU institutions (Beyers Citation2004; Dür and Mateo Citation2013; Hanegraaff et al. Citation2016).

Our third innovation is of a methodological nature. By employing both web scraping and automatic content analysis methods, we make use of and test a new approach which enables large-scale identification and analysis of interest group populations. More precisely, we created a dataset on access of interest groups to parliamentary committees in the Netherlands between 1970 and 2017. This study seeks to test whether this approach is reliable and therefore useful for other scholars that aim to identify large-scale interest group communities, and possibly other types of political actors.

In the following sections, we set out the theoretical framework, where we provide an overview of state-of-the-art work on why corporations tend to lobby and seek access on their own behalf. Subsequently, we theorise on potential structural explanatory factors. Through large-scale empirical analysis, trends of the phenomenon under study will be generated and modelled. Lastly, we discuss our results and outline suggestions for further research.

Literature review: current explanations for why corporations lobby alone

The political science literature has certainly not ignored the political interests of corporations (Baumgartner and Leech Citation2001; Hojnacki et al. Citation2012). Indeed, several of the most influential political scientists of the twentieth century have carefully considered how various economic interests, including business interests, were represented. In his seminal piece, Truman (Citation1971) poses that interest groups representing economic interests are highly significant for the political process and can play a major part in a system’s stability. In Schattschneider’s (Citation1960: xxi) work, business interests are a substantial part: he rejected the description of politics as a ‘balance of power’ and denounced the myth that the ‘pressure system is automatically representative of the whole community’. Pressure politics, rather, is a ‘selective process ill designed to serve diffuse interests’ and a ‘flawed heavenly chorus that sings with a strong upper-class accent, most notably economic interests’ (Schattschneider Citation1960: 35). Olson (Citation1965) also criticised the pluralist view, arguing that concentrated economic interests will be overrepresented, whereas diffuse majority interests are trumped due to a free-rider problem that becomes stronger when a group becomes larger. The importance of business interests was indeed a crucial part of their work.

Others, carefully considered business interests and more specifically those of individual corporations. Schattschneider (Citation1935) and Bauer et al. (Citation1972), for example, studied the interests involved in the tariff policy negotiations, including those of large and smaller firms. Bauer et al. (Citation1972: 230) find that leaders from larger corporations are more actively involved in information exchange on foreign policy compared to small firms and that this latter group was more likely to engage in matters specific to their own company rather than to general policy. Smith (Citation2000) illustrates in his book that the US Chamber of Commerce, which has both organisational and individual members, resisted participating in a policy debate that affected only a small part of the membership. When there is no broader support among the members for the association to act upon, corporations are inclined to ‘wage their own political battles on particularistic issues’ (Smith Citation2000: 41). Both Schlozman (Citation1984) and Salisbury (Citation1984) have also studied the interests of individual corporations. They observed that of all organisations having a Washington presence, corporations constitute the largest part (45.7% and 33.5%, respectively). Gray and Lowery (Citation2001) and Gray et al. (Citation2004) have demonstrated that the relative share of institutions (of which for-profit organisations constitute the largest share) registered to lobby increased from 39.55% in 1980 to 57.51% in 1997. In the European Union, we see a similar trend. While it seemed that individual firm lobbying decreased somewhat over the course of 1996 to 2007 (see Berkhout and Lowery Citation2010), in a recent study, Berkhout et al. (Citation2018) found that individual corporations now comprise the largest part of the lobbying community in the EU.

Despite the increasing dominance of corporations within interest group communities, our knowledge about why corporations lobby alone is still quite limited. We currently recognise three sets of explanations for why corporations tend to lobby alone, of which some are more developed than others. We can summarise these as explanations focusing on organisational characteristics, explanations focused at the level of policy sectors, and structural explanations (e.g. Bernhagen and Mitchell Citation2009; Boies Citation1989; Bouwen Citation2002; Coen Citation1997; Grant et al. Citation1989; Hart Citation2004; Walker and Rea Citation2014). In the remainder of this section we discuss these three perspectives and what we aim to contribute to these debates.

A first set of explanations focuses on organisational incentives that influence the strategic decision of corporations to seek access on their own behalf. Material interests of corporations, for example, form an important driver to engage in individual lobbying efforts. However, these interests can only explain such behaviour when tied to long-term relationships with the state, that is, corporations ‘with the richest history of interaction with the state are amongst the most politically active’ (Boies Citation1989: 830). Coen (Citation1997: 103) has illustrated that the take-up of new political channels by corporations, amongst other things through individual representation, is influenced by cost considerations, and concludes that ‘as the importance of cost grows, the greater the uncertainty of political returns associated with a specific channel’. In this context Bouwen (Citation2002: 374) has argued that when it comes to individual representation, ‘the reasoning is obvious: large players have more resources to invest’. Large firms are therefore more inclined to undertake individual lobbying attempts compared to smaller firms, as the latter group has to rely on collective action more often (see also Grant Citation1982).

A second set of studies highlights determinants at the level of policy issues or interest communities. The most influential work in this regard is provided by Grier et al. (Citation1994; see also Bernhagen and Mitchell Citation2009). Their benefit–cost model of firm political activity describes how variations in the structure of economic sectors provide different incentives for firms to engage in political activity in order to pursue investment-oriented goals. The ability to achieve such goals is conditioned, on the one hand, by the benefits of political action and, on the other hand, by the costs of engaging in cooperation and collective action (Grier et al. Citation1994). Madeira (Citation2016) finds that US corporations increasingly lobby alone in economic sectors characterised by intra-industry trade. The competitive nature within these sectors makes it difficult to coordinate trade preferences among individual corporations, leading them to increasingly bypass business associations and engage in lobbying activity by themselves. Lowery and Gray (Citation1998) have also provided important work in this regard, but these authors studied ‘institutions’ which include corporations, and also other actors, and focused on the dynamics of interest populations.

Lowery and Gray (Citation1998) relied on the assumption of population ecology to explain individual lobbying by institutions. They tested two ideas at this level describing mechanisms that could lead to relative increased individual lobbying by institutions. The first is related to the argument that relative levels of institutional representation increase as interest systems become denser (see also Wilson-Gentry et al. Citation1991: 5). The second hypothesis, ‘competitive exclusion’, states that if the number of members within an association grows, the association has a harder time to accommodate all the wishes of its members. As a result, members will have greater incentives to look for specific modes of representation (Gray et al. Citation2004). In the context of Europe, Grant et al. (Citation1989) studied the convergence between large firms and governments with regard to the chemical industry in Britain, Italy and West Germany. Whilst the study is mostly descriptive, the authors theorised about underlying pressures, such as the internationalisation of the industry, with the ‘increasing use of joint ventures between companies, and a growing European presence in the United States’ (Grant et al. Citation1989: 89).

The third set of studies provides hypotheses on how structural explanations could trigger corporations to lobby on their own behalf. Yet, of all three perspectives, the determinants of individual corporate lobbying from a structural perspective are by far the least developed. True, in a pluralist context, scholars have put forward several interesting ideas on how variation in economies and governments could affect the likelihood of institutions engaging in representation on their own behalf (Bernhagen and Mitchell Citation2009; Lowery and Gray Citation1998). These hypotheses, however, have hardly been empirically tested due to a lack of available data. In a corporatist context, scholars have extensively theorised about a more general trend towards less coordinated decision-making processes: the so-called decline of the traditional corporatist set-up (e.g. Binderkrantz Citation2012; Crepaz Citation1994; Öberg et al. Citation2011; Rommetvedt et al. Citation2013). Yet, applied to interest groups, a decline of corporatism is a description of an overall trend towards the declining importance of umbrella organisations in political decision making. Who has filled this void and why, has been largely overlooked so far (but see Binderkrantz Citation2012), let alone which economic and political-institutional factors could have cause these shifts in interest representation.

What we are interested in is therefore (1) to map the nature of interest representation over time and (2) link this to specific indicators of economic and political-institutional changes in society over an extensive time frame. In other words, do we observe a substantial rise in corporate access to the political process over the past decades and can we explain this through changes in the economic and political-institutional settings during this timeframe? This study seeks to explore this question, as it employs a novel dataset of interest group access to parliamentary commissions in the Netherlands over an extended period of time (almost 50 years). It builds on research that assessed the distribution of interest group communities and possible biases towards certain groups in constant changing contexts (Berkhout et al. Citation2018; Gray et al. Citation2004; Salisbury Citation1984; Schlozman Citation1984). By adding a longitudinal perspective to these debates we are able to carefully link the presence of different types of interest groups to (structural) variation in the state of the economy and the political-institutional context over time (Bernhagen and Mitchell Citation2009; Lowery and Gray Citation1998).

Hypotheses: exploring structural drivers of corporate access

Broadly, we consider two types of structural factors which could potentially affect the access corporations gain to policymakers: economic and political-institutional. We start with the effect of the economy on corporate access. Lowery and Gray (Citation1998: 251) have suggested that institutions dominate when governments are large compared to the economy, and during times of economic stress, where ‘the impact of economic size seems to be a function of enhanced free-riding within larger economies’. The underlying assumption is that more diverse and/or larger associations are more constrained compared to smaller or more homogeneous groups when it comes to interest representation (Aldrich et al. Citation1990; Wilson Citation1973). These constraints can be ‘exacerbated by economic conditions’ (Lowery and Gray Citation1998: 236), that is, when the economic conditions are better, it might be easier to accommodate or balance interests compared to when the economic conditions are tight, which might lead to a situation where lobbying is an endeavour of ‘every man – or institution – for himself’. In other words, when the state of the economy weakens, corporations may not be content with the decisions or performance of an association, as the latter actor may find itself in a situation where it becomes harder to accommodate all the wishes and needs of its members. This leads to the first hypothesis:

H1: Negative tendencies in the economy of a country lead to relatively increased access of individual corporations to the political system.

We continue with factors related to political-institutional developments. Our second explanation of individual corporate access is based on the idea of the benefit–cost model (Grier et al. Citation1994). In terms of this theoretical model, corporations are thought to engage in lobbying efforts to ‘secure sales and avoid or modify costly regulations’ (Hansen and Mitchell Citation2000: 892). We apply this logic to the development of Europe as a single market and the associated political opportunities and constraints that emerged in Europe. During this process, several treaties were signed, such as the Single European Act and the Maastricht Treaty, which we believe triggered corporations to increase individual lobbying instead of seeking access to politics via associations. For instance, Streeck and Schmitter (Citation1991) noted that during the late 1970s business was granted the opportunity, on the one hand, to withstand corporatism at the national level and, on the other hand, to keep its distance from collective action endeavours at the EU level. In this way, corporations were ‘successfully playing the two political markets against each other’ (Coen Citation1997: 94).

This also put pressure on the relationship between corporations and national business associations. Indeed, corporations no longer need to collectively bargain with a national association, but can play at multiple boards at the same time to increase their own gains as much as possible (see Coen Citation1997: 94 for a similar argument). Likewise, governments are less able to force corporations to lobby via associations, as was common in a corporatist setting, but need to accommodate the individual needs of corporations to keep them on board. Hence, we believe, increased Europeanisation has greatly strengthened the position of individual corporations at the expense of associations. As a result, firms have often bypassed associations, while politicians are more frequently forced to include them in parliamentary hearings. Overall, we therefore expect that European integration has led to increased incentives for corporations to lobby by themselves, rather than rely on business associations alone, and a willingness by MPs to grant them access. We therefore state that:

H2: The increased degree of political opportunities due to European integration leads to relatively increased access of individual corporations to the political system.

Third, the size of the government could serve as a trigger for individual corporate access (Esty and Caves Citation1983; Salisbury Citation1984; Wilson Citation1973). Although not exclusively discussing corporations, Wilson (Citation1973: 341) made a careful first step in this direction by arguing that political activity initiated by interest organisations is related to the scope of government. In 1983, Esty and Caves demonstrated that government expenditures facilitate favours being conferred on an industry. Salisbury (Citation1984: 68) has also provided important work in this regard by proposing triggers of the dominance of corporations within interest group communities, arguing that their dominance increases as governments and the scope and impact of their policies expand. Lowery and Gray (Citation1998) have explored the relation between the size of governments and the relatively dominant position of firms by building on the work of Wilson-Gentry et al. (Citation1991), stating that the potential advantages to particular interests become larger when governments become larger compared to the costs involved in initiating an individual lobbying effort or setting up a specialised association (Lowery and Gray Citation1998). This mechanism then leads to a higher rate of specialised interests. As a result, we should expect to find that the relative share of corporate access increases as the size of the government grows (and vice versa). This leads to the following hypothesis:

H3: Increased government size leads to relatively increased access of individual corporations to the political system.

Finally, we explore whether the political orientation of the government of a country matters. We expect that corporations are more inclined to seek access on their own behalf when the government has a right-wing or liberal political orientation. First, corporations are thought to lobby on narrow and specific issues when they lobby individually (Gray et al. Citation2004), and are therefore more likely to lobby their friends (see Gullberg Citation2008; Kollman Citation1997: 539). Second, governments with a more right-wing or liberal political orientation are thought to have better ties with capital than with labour. Although the Netherlands is characterised by a depillarised society (Mair Citation2008), where ties between the right wing and capital and the left wing and labour have been loosened, traditionally they are still there, for example because they generally share common interests and viewpoints on issues (Kollman Citation1997). We therefore argue:

H4: An increased degree of right-wing or liberal political orientation in government leads to relatively increased access of individual corporations to the political system.

Data and methods

The data that we relied on for this study consist of two parts. First, we scraped1 the minutes of parliamentary hearings of various commissions from 1970 to 2017. Prior to attendance, a process takes place between the organisations that seek to attend parliamentary hearings and the members of parliament who invite organisations to attend.2 For this endeavour, we used the attendance lists of these minutes. While parliamentary hearings are not necessarily representative for the entire degree of access interest groups may gain to the political system, it is a very important point of access for interest groups in the Netherlands.3 Most important for our case, parliamentary hearings are an important link between the state and civil society (see Hough Citation2012; Pedersen et al. Citation2015). If we find an increase of corporate lobbying within this venue, it is a strong indication that similar processes, perhaps even more outspoken, are taking place within other venues, such as in bureaucratic access (see Binderkrantz et al. Citation2015: 105; Bouwen Citation2004: 358; Braun Citation2013). It must be noted here that minutes were not always kept and documented. Up until 2008, transparency of the political process was deemed less important and for this reason it could very well be the case that more hearings were held which are not included in our dataset. We controlled for this deficit by determining the relative share of the presence of organised interests in parliamentary hearings. Our dataset contains 1080 documents.

Second, we employed the database of the Netherlands Chamber of Commerce. We used its database to generate reliable, population-wide data over an extended period, that is, a list of all the organisations that were active between 1970 and 2017. The organisations that were included in our dataset are corporations with 250 employees or more. This cut-off point was selected, first, because although these corporations are large, they represent a broad range of companies and different sectors. Second, as larger firms are more likely to represent themselves individually than smaller firms, the odds that smaller firms representing themselves would be ignored are small. The dataset also includes (professional) membership groups, business associations, unions, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), groups of institutions and authorities, and research/think tank groups with 100 employees or more. The cut-off point for all the other organised interests is lower, as they tend to have smaller numbers of employees. To ensure that we would, on the one hand, capture these organisations and, on the other hand, would have a comparable sample, this cut-off point was set. The only problematic factor here is the category of NGOs, which often only have a small number of employees and many volunteers. To compensate for this, we included a list of NGOs that were active in the Netherlands over an extended period.4

As for the variables and measurement, we start with the operationalisation of our dependent variable: access of corporations to parliament, relative to the access of all types of interest groups. We employed a similar categorisation of interest groups to that applied by Binderkrantz (Citation2012). More precisely, corporate access was measured as the relative share of individual corporate access per year, that is, the number of mentions of individual corporations relative to the number of mentions of associations and non-profit organisations in parliamentary hearings per year. Table 2 in the online appendix displays the full operationalisation and measurement of our dependent variable under study. The dependent variable was measured by running an automated query of the names extracted from the Netherlands Chamber of Commerce in our dataset of minutes of parliamentary hearings.

In order to ensure reliability of this method, a random sample of 50 documents, and therewith 245 organisations, was manually coded.5 When comparing the original list of organisations and the documents, the automated query missed 5.7% due to different spelling that was used in the documents compared to the register. Of the 245 organisations, 7.6% was counted double. This occurred when both the full name and abbreviation were used in the documents or when a merger of two organisations took place during the period under study; 92.4% of the identified organisations can therefore be categorised as correct. In total, there was an error of 13.3%. Reliability of the manual coding scheme was ensured by involving a second independent coder which coded an identical sample of 20 documents, yielding Krippendorff’s alphas of 0.94, 0.86, 0.65, 0.71 and 0.62. The reported alphas correspond with the variables of the coding scheme which is included in the online appendix. The errors caused by the automatic method could have been prevented when all documents were coded manually, however when one wishes to make inferences on large-scale populations, this is highly time-consuming and therefore costly. Compared to using random or policy samples to identify the interest group population (see Berkhout et al. Citation2018 for a discussion), this method is a good way forward for scholars seeking to identify interest group communities across different countries and time. That is, when the necessary documents are available and when the method is combined with close monitoring of systematic error that could bias the results and manual verification.

In order to model the development of corporate access over time and to test whether our independent variables have an effect, we used an autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model (Box and Jenkins Citation1970). The autoregressive integrated moving average model is a time series analysis model that takes into account that observations are sequential, and often there is a matter of autocorrelation. The latter means that a current value is correlated with previous values over time. The main assumption of an ARIMA is that ‘a time series variable’s own past can help to explain its current value, and therefore before exogenous explanatory variables can even be considered, it is first necessary to model the series’ own past and thus capture its endogenous dynamics’ (Vasileiadou and Vliegenthart Citation2014: 696).

We now turn to our independent variables.6 In order to measure tendencies in the economy (H1), we used the gross domestic product (GDP) of the country under study and, more specifically, the annual growth rate of the GDP, for which we relied on statistics provided by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). For the degree of political opportunities and constraints that came into existence due to European integration (H2), we relied on the treaties signed by the EU. A treaty is a binding agreement between members of the EU and has several objectives, such as the introduction of new areas of cooperation. Since within our period under study several treaties were signed, this variable has an ordinal measure. To measure government size (H3), we used government expenditure as a proxy, which was calculated as the percentage of actual government expenditure in million euros from actual GDP in million euros. Subsequently we calculated the growth rate, which is the change in growth compared to the previous year. The actual expenditure by government was extracted from the database of Statistics Netherlands (CBS). For our final political-institutional variable (H4), that is, the political alignment of government, we relied on data gathered and coded as part of the Comparative Political Dataset (Armingeon et al. Citation2018). More specifically, for this project, cabinet composition was coded, using the Schmidt index, which has a five-point scale, where 1 stands for ‘Hegemony of right-wing (and centre) parties’ and 5 stands for ‘Hegemony of social-democratic and other left parties’. Table 2 in the online appendix displays the full operationalisation and measurement of our independent variables under study.

Analysis

Descriptive analysis

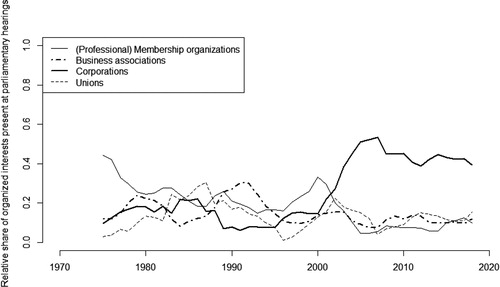

In this section, we first present a descriptive analysis, followed by the explanatory analysis of our study in the next section. Over time, and in total, we identified 1784 organised interests that gained access to parliamentary hearings. The largest category present at the hearings comprises corporations, which made 664 appearances at parliamentary hearings in the Netherlands during the period under study. Professional and regular membership groups are ranked second, with a total of 264 appearances. The third largest category consists of unions, with a total of 230 appearances, and the fourth category comprises business associations, with 213 appearances. The appearances of these four categories during the entire period under study are depicted in .7

Figure 1. Moving average of relative share of organised interests, including corporations, present at parliamentary hearings over time in the Netherlands.

Note: Moving average is calculated as the means of non-overlapping groups of five.

The trends of appearances of the four categories depicted in the first figure range in nature from positive to stable and slight negative trends. When we take a closer look at business associations that attended parliamentary hearings, we can identify a trend that is slightly negative (r(46) = −0.19, p = 0.18). When we consider both business associations and corporations as part of the business community, however, the image alters. While this category was certainly not the most substantial group at the beginning of the period under study, corporations have managed to gain access at an increasing rate from the mid-1990s onwards (r(46) = 0.59, p < 0.0001). This indicates that, just as in pluralist contexts, corporations constitute the largest set of actors that gain access to politics (Baumgartner and Leech Citation2001; Berkhout et al. Citation2018; Chalmers Citation2013; Salisbury Citation1984; Schlozman Citation1984) and have also managed to increase this access (Gray et al. Citation2004).

Both the decrease of appearances by business associations and the increase of appearances by corporations that have managed to gain access to policymakers in a corporatist context are in line with ideas on the decline of neo-corporatist arrangements (Öberg et al. Citation2011; Rommetvedt et al. Citation2013). More specifically, the latter concept could account for an increase in corporate lobbying, as scholars have argued that due to such a decline, groups that were by default invited to the negotiation table are no longer necessarily included (Binderkrantz Citation2012; Crepaz Citation1994). It makes sense, therefore, that the members of these umbrella groups which previously participated in the political process through their representatives are more inclined to represent their own interests compared to before. While this general phenomenon could help to explain a broader trend of increased access by corporations to the political process in the Netherlands, it cannot account for the trend while ruling out randomness with an explanatory model, nor can it necessarily explain the steep increase that is visible from 1995 onwards, as scholars have stated that corporatist exchange ‘was at its heyday in the Netherlands between 1990 and 2005’ (Woldendorp Citation2011: 22). In other words, there must be other structural factors that can explain this sudden and lasting peak of increased corporate access in the Netherlands beyond the decline of corporatism. We shall analyse this in the next section.

Explanatory analysis

We now turn to the explanatory part of our analysis. Our variables were modelled in an ARIMA framework, where we first tested assumptions and attempted to generate the best possible model fit. One of the most important assumptions of an ARIMA model is stationarity. This means that the mean of the time series dependent variable should be ‘unaffected by a change of time origin’ (Vasileiadou and Vliegenthart Citation2014). In our case, we can see an upward trend in the dependent variable, which means that our data are non-stationary. The augmented Dickey–Fuller test also indicated that our data are non-stationary. We therefore differenced our dependent variable to ensure that we meet all the requirements of the test.8

This resulted in a test statistic that confirms that our data are now stationary. Subsequently, we found that an ARIMA (4,1,0) model had the best fit, that is, with four AR terms, first order differencing and zero MA terms. We first ran the effects separately, as we did not have any prior expectations about the causal order of our independent variables, and subsequently fitted them into one model. The results are displayed in .

Table 1. Separate macro-effects with four lags on individual corporate lobbying and combined in one model (n = 47).

Our explanatory analysis indicates a significant negative effect of economy on our dependent variable, which indicates that when negative shocks are observable in the state of the economy, individual access of corporations increases. By adding this exogenous variable to our model, the fit increases, as the AIC decreases from −29.98 to −34.75. When controlling for all the other exogenous variables under study, the significant effect remains. This finding is in line with the economic stress mechanism (Gray et al. Citation2004; Lowery and Gray Citation1998), where the relative share of corporate access increases as a result of a negative shock in the state of the economy. This finding also echoes macroeconomic lows in the Netherlands before 1995, as well as both the subsequent linkage between the market and public sectors and the economic drop after 9/11 and the bursting of the so-called internet bubble (Woldendorp Citation2011). After 2005, the public and market sectors were again delinked (Woldendorp Citation2011). Although these trigger events could certainly help explain peaks in corporate access, our model rather confirms our first hypothesis, indicating that broader negative tendencies in the economy lead to a relative increase in corporate access.

Our measure of political opportunities and constraints as a result of European integration indicates a positive effect on corporate access. While the separate effect is not significant, when we control for other macro-determinants it is (p < 0.05). Moreover, when we add this variable to the model, the AIC decreases, thereby increasing the fit of our model. This means that when the degree of political opportunities within Europe increases, individual corporate access increases. This finding is in line with Coen’s observation that firms aim to ‘play two political markets against each other’ (Coen Citation1997: 94). This finding also explains why we observe a longer episode of higher shares of corporate access starting in 1994 (see ), which could be caused by the political opportunities and constraints that were created with the realisation of two important European treaties (Maastricht and Amsterdam), which were signed and came into force during the period between 1992 and 1999. Overall, we confirm hypothesis 2: an increased degree of political opportunities and constraints due to European integration has led to increased corporate access.

The third hypothesis, on government size, where we used government expenditure as a proxy, indicates a positive effect on the degree of corporate access. The effect has the direction that we expected, however, it is non-significant, and we therefore cannot confirm our third hypothesis. This finding does not align with earlier work (Esty and Caves Citation1983; Salisbury Citation1984; Wilson Citation1973), which indicates that government expenses could trigger individual corporate access. Also, Lowery and Gray (Citation1998) empirically found a positive and significant relation between state expenditure and firm lobbying in the US across states. It is unclear whether the different findings for these studies relate to the context (pluralist versus corporatist) or to the research design (cross-sectional versus longitudinal). Future research should address this. For now, however, we do not confirm that state expenses affect individual corporate access over time.

Our last measure, political orientation of the government, indicates a negative effect on the degree of individual corporate access. This would mean that the more right-wing the government, the more access individual corporations gain. We do not, however, find this effect to be significant. An explanation for our finding could be that other mechanisms occur simultaneously, that is, when organised interests lobby foes (Ainsworth Citation1993) or opt for both depending on different conditions such as the policy issue (Gullberg Citation2008). Yet our data do not allow including such measures, as they are micro-level explanations which fall beyond the scope of this study. We can state here that, overall, it does not matter which government is in power for the degree of access that corporations gain. We do not confirm the fourth hypothesis.

Discussion

Scholarly work indicates that corporations are amongst the most frequent policy participants in our political systems. Yet important work on this phenomenon has focused strongly on the US, leaving a gap in our knowledge on corporate lobbying within European contexts. This article illustrates for the first time that, in contrast to several decades ago, corporations have over time managed to increase their access to policymakers in a neo-corporatist European context. What is more, this category now constitutes the largest group participating in the political process, highlighting the robustness and generalisability of work on the same phenomenon in pluralist contexts (Baumgartner and Leech Citation2001; Berkhout et al. Citation2018; Chalmers Citation2013; Gray and Lowery Citation2001; Gray et al. Citation2004; Lowery et al. Citation2005; Salisbury Citation1984; Schlozman Citation1984).

The main finding of this study resonates with ideas on the decline of traditional corporatist arrangements (Öberg et al. Citation2011; Rommetvedt et al. Citation2013), as umbrella groups such as business associations have not necessarily managed to expand their access to the political process. While this could have led to a more diverse distribution of organised interests that gain access to the political process, it seems that it is rather the members of this latter category that have managed to expand their access, as they have been inclined to seek other modes of interest representation, such as representing themselves. As a result, when both business associations and corporations are considered as business interests, the distribution of organised interests involved in the political process is largely skewed towards business. This study illustrates an even stronger overrepresentation of relative access of business to parliamentary venues than other studies that look at parliamentary access (see Binderkrantz et al. Citation2015: 105; Fraussen and Beyers Citation2016: 17). What is more, other work that has studied interest group access to parliamentary venues indicates that bias towards business is less strong in political venues compared to bureaucratic venues (Bouwen Citation2004: 358). This would mean that we can expect an even stronger overrepresentation of business when it comes to administrative access, a finding that is problematic as democracies thrive when many different voices are expressed.

While the so-called decline of traditional corporatist set-ups could help explain a general trend of corporations that have managed to expand their access to the political system, it cannot explain the steep increase in corporate presence from 1995 onwards, nor can it account for the phenomenon under study in this article while ruling out randomness. The explanatory model of this article indicates that when the economy weakens, corporations tend to interact with politicians more frequently. The former finding is in line with mechanisms that have been labelled as the ‘economic stress mechanism’, where ‘fragmentation is caused by the general economy as it is easy to have an umbrella organization when there is a lot of money to go around’, however, when the economy is in a bad state, ‘lobbying may devolve to a situation of every man for himself’ (Lowery and Gray Citation1998: 236–37). This is troubling due to the potential threats it can pose to democratic systems (Gray et al. Citation2004; Hart Citation2004; Martin and Swank Citation2004; Olson Citation1965; Salisbury Citation1984; Wilson Citation1973: 310).

Second, corporations have also gained more access due to increased European integration. This could explain the observed longer shock of higher shares of corporate access in the decade of the 1990s, and resonates with Coen’s (Citation1997: 94) suggestion that increased political opportunities for corporations allow them to participate in two political markets at both the European and national level. This is an important finding, as it indicates that Europeanisation could account for changed state–interest group interactions in recent decades. While we contend that we cannot overgeneralise based on our case and dynamic model, we do believe this warrants more research to critically examine the effects of corporatism for lobby behaviour and access in other contexts and, more importantly, how these relate to the Europeanisation of political and economic processes.

Finally, this study illustrates that our automated approach to identify large-scale interest group populations is a reliable tool. With equivalent materials at hand and manual verification to minimise systematic error, it is a way forward compared to other approaches to identify interest group communities such as complete manual coding or the use of policy or random samples. With registers of organisations available in most countries in Europe, the US and Australia, scholars are able to create queries for all organisations active over extensive periods of time and can test for political activity in documents ranging from minutes and agendas of parliamentary meetings to political newspaper coverage. The former would indicate political activity through interaction with political elites and the latter participation in the political discourse when filtered for political news. With the availability of statistical data on societal, economic and political developments, scholars can also study drivers of interest group patterns beyond the scope of corporations. In short, we believe that with the current use of methods and data, large-scale interest group communities can be studied in a systematic manner over extended periods of time and across political systems.

Whilst this endeavour contributed to our knowledge of the development of corporate access over time, certain factors limited our pursuit. The first aspect concerns the dataset on which we relied to measure individual corporate access, that is, minutes of parliamentary hearings. Although this set provides a good source from which to draw inferences regarding the presence of corporations in the political process, it does not include all hearings that were held during this period, as they were not always obliged to take minutes and store these on a platform accessible to the public. However, we do not see this as a major problem for this study, as we controlled for this by determining relative shares. At the same time, we certainly encourage other studies to validate or challenge our findings, either in a similar context or beyond.

Second, our focus on parliamentary hearings means that we did not shed light on access to the entire policy process, most notable the bureaucracy. Yet most studies indicate that biases towards specific interests are higher at bureaucratic venues, given their need for technical and detailed information. The parliamentary hearings are by design intended to provide various stakeholders the opportunity to voice their concerns or provide input on (potential) legislation. Hence, the fact that we find an increase of corporate lobbying, even at this venue, suggests that this is part of a broader trend. However, more research is needed to substantiate this expectation.

Finally, it is important to stress that it is impossible with our type of data to shed light on the causal mechanisms in place before corporations (or other groups) managed to gain access to the policy process. In other words, we do have a better understanding of when corporations participated in the process, but we have not been able to grasp their unsuccessful efforts to gain access or those of other organised interests to compare the two groups. Moreover, we find links between certain structural changes in society and changes in corporate access. Yet the dynamic nature of our model does not allow us to make strong causal claims about the origins of these links. These illustrated links, however, represent interesting paths to pursue in future research. For instance, it would be recommended to delve deeper into the sudden change in corporate lobbying in the 1990s. Case studies could seek to address whether this is indeed, as we expect, mainly driven by changes in European governance. More specific analysis in this regard would be a great addition to capture the more nuanced mechanism underlying the broad trend we present in this article.

To conclude, with this article we aimed to highlight and explain the growing importance of corporations in political systems beyond the US. Through the current endeavour, we sought to test a new approach which proves to be a useful tool to identify large-scale interest group populations that is also applicable in other contexts. We hope that European scholars are now keener to further acknowledge the role and importance of corporations within our political systems by exploring why corporations lobby, what strategies they use and, ultimately, what impact they have on policy making.

Notes on contributors

Ellis Aizenberg is a PhD Candidate in Political Science at the University of Amsterdam. Her research focuses on interest groups and lobbying. She currently works on the lobbying behaviour of corporations in Western Europe. [[email protected]]

Marcel Hanegraaff is Assistant Professor in Political Science at the University of Amsterdam. His research is on the politics of interest representation in a transnational and EU context, as well as on the functioning of international organisations in the fields of climate change and global trade. [[email protected]]

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (53.9 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Beth Leech, Joost Berkhout and the anonymous reviewers for their useful feedback on previous versions of this paper and Sarah Kalaï for her assistance in coding.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

Notes

1 Scraping was done by writing a script in the programming language Python that automatically identified, downloaded and stored our documents of interest.

2 According to a head of public affairs that works for a big airline company and a senior policy advisor that directly reports to the Prime Minister. These explorative interviews were held respectively in October and November, 2016 in preparation of the data collection.

3 See note 2.

4 This list was extracted from a news platform, Oneworld.nl, that reports on the work of NGOs in the Netherlands.

5 The coding scheme is included in the online appendix.

6 As a test of robustness, multicollinearity checks were conducted. No multicollinearity was identified between the independent variables, as all correlated no higher than r < 0.36.

7 Figure 2 in the online appendix depicts the appearances of all organised interests that were identified during the period under study.

8 The dependent variable after first-order differencing is depicted in Figure 3 in the online appendix.

References

- Ainsworth, S. (1993). ‘Regulating Lobbyists and Interest Group Influence’, The Journal of Politics, 55, 41–56.

- Aldrich, Howard E., Udo Staber, Catherine Zimmer, and John J. Beggs (1990). ‘Minimalism and Organizational Mortality: Patterns of Disbanding Among U.S. Trade Associations, 1900-1983’, in Jitendra V. Singh (ed.), Organizational Evolution: New Directions. Newbury Park: SAGE.

- Armingeon, Klaus, Virginia Wenger, Fiona Wiedemeier, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner, and Sarah Engler (2018). Comparative Political Data Set 1960-2016. Berne: Institute of Political Science, University of Berne.

- Bauer, R., Ithiel de Sola Pool, and Lewis A. Dexter (1972). American Business and Public Policy: The Politics of Foreign Trade. New York: Atherton.

- Baumgartner, Frank R., and Beth L. Leech (2001). ‘Interest Niches and Policy Bandwagons: Patterns of Interest Group Involvement in National Politics’, Journal of Politics, 63:4, 1191–213.

- Berkhout, J., and D. Lowery (2010). ‘The Changing Demography of the EU Interest System since 1990’, European Union Politics, 11:3, 447–61.

- Berkhout, J., J. Beyers, C. Braun, M. Hanegraaff, and D. Lowery (2018). ‘Making Inference across Mobilisation and Influence Research: Comparing Top-Down and Bottom-Up Mapping of Interest Systems’, Political Studies, 66:1, 1–20.

- Bernhagen, P., and N. J. Mitchell (2009). ‘The Determinants of Direct Corporate Lobbying in the European Union’, European Union Politics, 10:2, 155–76.

- Beyers, J. (2004). ‘Voice and Access: Political Practices of European Interest Associations’, European Union Politics, 5:2, 211–40.

- Binderkrantz, A. (2012). ‘Interest Groups in the Media: Bias and Diversity over Time’, European Journal of Political Research, 51:1, 117–39.

- Binderkrantz, A. S., P. M. Christiansen, and H. H. Pedersen (2015). ‘Interest Group Access to the Bureaucracy, Parliament, and the Media’, Governance, 28:1, 95–112.

- Boies, J. L. (1989). ‘Money, Business, and the State: Material Interests, Fortune 500 Corporations, and the Size of Political Action Committees’, American Sociological Review, 54:5, 821–33.

- Bouwen, P. (2002). ‘Corporate Lobbying in the European Union: The Logic of Access’, Journal of European Public Policy, 9:3, 365–90.

- Bouwen, P. (2004). ‘Exchanging Access Goods for Access: A Comparative Study of Business Lobbying in the European Union Institutions’, European Journal of Political Research, 43:3, 337–69.

- Box, G., and G. Jenkins (1970). Time Series Analysis, Forecasting and Control. San Francisco: Holden Day.

- Braun, C. (2013). ‘The Driving Forces of Stability: Exploring the Nature of Long-Term Bureaucracy–Interest Group Interactions’, Administration & Society, 45:7, 809–36.

- Chalmers, A. W. (2013). ‘With a Lot of Help from Their Friends: Explaining the Social Logic of Informational Lobbying in the European Union’, European Union Politics, 14:4, 475–96.

- Coen, D. (1997). ‘The Evolution of the Large Firm as a Political Actor in the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy, 4:1, 91–108.

- Crepaz, M. M. L. (1994). ‘From Semisovereignty to Sovereignty: The Decline of Corporatism and Rise of Parliament in Austria’, Comparative Politics, 27:1, 45–65.

- Dür, A., and G. Mateo (2013). ‘Gaining Access or Going Public? Interest Group Strategies in Five European Countries’, European Journal of Political Research, 52:5, 660–86.

- Eising, R. (2007). ‘The Access of Business Interests to EU Institutions: Towards élite Pluralism?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 14:3, 384–403.

- Esty, D. C., and R. E. Caves (1983). ‘Market Structure and Political Influence: New Data on Political Expenditures, Activity, and Success’, Economic Inquiry, 21:1, 24–38.

- Fraussen, B., and J. Beyers (2016). ‘Who’s in and Who’s out? Explaining Access to Policymakers in Belgium’, Acta Politica, 51:2, 214–36.

- Grant, W. (1982). ‘The Government Relations Function in Large Firms Based in the United Kingdom: A Preliminary Study’, British Journal of Political Science, 12:4, 513–16.

- Grant, Wyn, Alberto Martinelli, and William Paterson (1989). ‘Large Firms as Political Actors: A Comparative Analysis of the Chemical Industry in Britain, Italy and West Germany’, West European Politics, 12:2, 72–90.

- Gray, V., and D. Lowery (2001). ‘The Institutionalization of State Communities of Organized Interests’, Political Research Quarterly, 54:2, 265–84.

- Gray, V., D. Lowery, and J. Wolak (2004). ‘Demographic Opportunities, Collective Action, Competitive Exclusion, and the Crowded Room: Lobbying Forms among Institutions’, State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 4:1, 18–54.

- Grier, K. B., M. C. Munger, and B. E. Roberts (1994). ‘The Determinants of Industry Political Activity, 1978–1986’, American Political Science Review, 88:4, 911–26.

- Gullberg, A. T. (2008). ‘Lobbying Friends and Foes in Climate Policy: The Case of Business and Environmental Interest Groups in the European Union’, Energy Policy, 36:8, 2964–72.

- Hanegraaff, M., J. Beyers, and I. De Bruycker (2016). ‘Balancing inside and outside Lobbying: The Political Strategies of Lobbyists at Global Diplomatic Conferences’, European Journal of Political Research, 55:3, 568–88.

- Hansen, W. L., and N. J. Mitchell (2000). ‘Disaggregating and Explaining Corporate Political Activity: Domestic and Foreign Corporations in National Politics’, American Political Science Review, 94:4, 891–903.

- Hart, D. M. (2004). ‘“Business” Is Not an Interest Group: On the Study of Companies in American National Politics’, Annual Review of Political Science, 7:1, 47–69.

- Hojnacki, M., D. C. Kimball, F. R. Baumgartner, J. M. Berry, and B. L. Leech (2012). ‘Studying Organizational Advocacy and Influence: Reexamining Interest Group Research’, Annual Review of Political Science, 15:1, 379–99.

- Hough, R. (2012). ‘Do Legislative Petitions Systems Enhance the Relationship between Parliament and Citizen?’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 18:3–4, 479–95.

- Kollman, K. (1997). ‘Inviting Friends to Lobby: Interest Groups, Ideological Bias, and Congressional Committees’, American Journal of Political Science, 41:2, 519–44.

- Lowery, D., and V. Gray (1998). ‘The Dominance of Institutions in Interest Representation: A Test of Seven Explanations’, American Journal of Political Science, 42:1, 231–55.

- Lowery, D., V. Gray, and M. Fellowes (2005). ‘Sisyphus Meets the Borg: Economic Scale and Inequalities in Interest Representation’, Journal of Theoretical Politics, 17:1, 41–74.

- Madeira, M. A. (2016). ‘New Trade, New Politics: Intra-Industry Trade and Domestic Political Coalitions’, Review of International Political Economy, 23:4, 677–711.

- Mair, P. (2008). ‘Electoral Volatility and the Dutch Party System: A Comparative Perspective’, Acta Politica, 43:2-3, 235–53.

- Martin, C. J. (2005). ‘Corporatism from the Firm Perspective: Employers and Social Policy in Denmark and Britain’, British Journal of Political Science, 35:1, 127–48.

- Martin, C. J., and D. Swank (2004). ‘Does the Organization of Capital Matter? Employers and Active Labor Market Policy at the National and Firm Levels’, American Political Science Review, 98:4, 593–611.

- Öberg, P., T. Svensson, P. M. Christiansen, A. S. Nørgaard, H. Rommetvedt, and G. Thesen (2011). ‘Disrupted Exchange and Declining Corporatism: Government Authority and Interest Group Capability in Scandinavia’, Government and Opposition, 46:3, 365–91.

- Olson, M. (1965). The Theory of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Pedersen, H. H., D. Halpin, and A. Rasmussen (2015). ‘Who Gives Evidence to Parliamentary Committees? A Comparative Investigation of Parliamentary Committees and Their Constituencies’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 21:3, 408–27.

- Rommetvedt, H., G. Thesen, P. M. Christiansen, and A. S. Nørgaard (2013). ‘Coping with Corporatism in Decline and the Revival of Parliament: Interest Group Lobbyism in Denmark and Norway, 1980–2005’, Comparative Political Studies, 46:4, 457–85.

- Salisbury, R. H. (1984). ‘Interest Representation: The Dominance of Institutions’, American Political Science Review, 78:1, 64–76.

- Schattschneider, E. E. (1935). Politics, Pressures and the Tariff. New York: Prentice Hall.

- Schattschneider, E. E. (1960). The Semisovereign People: A Realist’s View of Democracy in America. Hinsdale: The Dryden Press.

- Schlozman, K. L. (1984). ‘What Accent the Heavenly Chorus? Political Equality and the American Pressure System’, The Journal of Politics, 46:4, 1006–32.

- Smith, M. A. (2000). American Business and Political Power: Public Opinion, Elections, and Democracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Streeck, W., and L. Kenworthy (2005). ‘Theories and Practices of Neocorporatism’, in T. Janoski, R. R. Alford, A. M. Hicks, and M. A. Schwartz (eds.), The Handbook of Political Sociology: States, Civil Societies and Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 441–61.

- Streeck, W., and P. C. Schmitter (1991). ‘From National Corporatism to Transnational Pluralism: Organized Interests in the Single European Market’, Politics & Society, 19:2, 133–64.

- Truman, D. B. (1971). The Governmental Process. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Vasileiadou, E., and R. Vliegenthart (2014). ‘Studying Dynamic Social Processes with ARIMA Modeling’, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 17:6, 693–708.

- Walker, E. T., and C. M. Rea (2014). ‘The Political Mobilization of Firms and Industries’, Annual Review of Sociology, 40:1, 281–304.

- Wilson, James Q. 1973. Political Organizations. New York: Basic Books.

- Wilson-Gentry, L. A., G. G. Brunk, and K. G. Hunter (1991). ‘Institutional and Environmental Influences on the Form of Interest Group Activity’, Annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Chicago, Illinois, April.

- Woldendorp, J. J. (2011). ‘Corporatism in Small North-West European Countries 1970-2006: Business as Usual, Decline, or a New Phenomenon?’, unpublished manuscript, VU University Amsterdam.