Abstract

Leadership studies research reveals that political leaders’ beliefs affect their political and policymaking behaviour, especially in times of crisis. Moreover, the level of flexibility of these beliefs influences the likelihood that groups of leaders come to collective decisions. Insight into when and why political leaders do, in fact, change their beliefs is sorely lacking. This paper uses fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) to examine the antecedents of belief changes among 12 European leaders, all working in the realm of economic policy. Its findings reveal how increases in unemployment and unsustainable debt, as well as different government ideologies and increases in Euroscepticism lead to economic belief changes. In so doing, this paper begins to open the ‘black box’ of when, why, and under what conditions leaders change their beliefs.

Progress is impossible without change; and those who cannot change their minds, cannot change anything. (Shaw Citation1944: 330)

Political leaders, like all of us, are sense-making machines. When faced with a situation that threatens the status quo, political leaders turn to their personal beliefs to make the threat more ‘explicable, manageable and actionable’ (Blyth Citation2002: 10). In times of crisis, in particular, political leaders’ beliefs inform and shape their policymaking (Cuhadar et al. Citation2017; Dyson Citation2018; Kaarbo Citation2018; Van Esch and Swinkels Citation2015). At the same time, these beliefs are themselves susceptible to influence from the dynamics of political and economic contexts, a leader’s traits, the political time in which a political leader operates, and a leader’s relationship with followers (Goetz Citation2017; Helms Citation2014; Kaarbo Citation2018). Although many studies focus on the beliefs of political leaders as an independent variable affecting political and policy success or failure (e.g. Brummer Citation2016), fewer studies focus on beliefs as a dependent variable. As such, leadership studies lack knowledge of the antecedents of political leaders’ belief changes.

The Eurozone crisis (2009–2015) greatly tested EU leaders’ core beliefs about the economy. First, the EU lacked adequate mechanisms to deal with the crisis and these structural deficiencies caused severe deadlock in the EU’s political system. As such, the crisis provided the setting for an exercise in collective political leadership (Müller and Van Esch Citation2019). The fragmented and multi-faceted EU leadership polity was tasked with making sense of the situation at hand, while providing meaning to its various constituencies through a coherent crisis narrative (Boin et al. Citation2017; Van Esch and Swinkels Citation2015). Second, EU political leaders’ diverse preferences, pressures, and priorities can either constrain or enable their sense-making and meaning-making activities. The combination of a lack of an established institutional response and the diverse economic and political contexts in which political leaders operate provides scholars of EU leadership with a unique opportunity to study belief changes. The central questions, then, are whether such contextual factors affected the core beliefs of EU political leaders, and how.

This paper examines these questions. It uses insights from EU and leadership studies about the influence of changing political and economic contexts, and how this may manoeuvre the beliefs of political leaders. The paper presents a framework for tracking beliefs and belief change, and articulates four conditions suggested to influence the propensity for belief change in the realm of European economic policy. These are increases in negative support for the merits of European integration, unsustainable public debt, increased unemployment, and member states’ ideological divergence from average EU government ideology. Using unique material on European Council leaders’ economic beliefs, the paper describes the ways in which these conditions affected leaders’ beliefs, in the case of the Eurozone crisis (2009–2015), using fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA).

The outcome (dependent variable) is measured through Comparative Cognitive Mapping analysis of the core economic beliefs of 12 heads of state or government (HSG) during the Eurozone crisis of 2009–2015 (Van Esch et al. Citation2017).Footnote1 Existing data from the Comparative Political Data Set and Eurostat is used to study the conditions affecting belief change. The fsQCA findings reveal that, when faced with changes in their political and economic contexts, political leaders may re-evaluate both the salience and core meaning of their economic beliefs, but that these conditions only partially explain why core beliefs change during an economic crisis.

Theoretical framework

Leaders as believers

John (Citation1998: 145) states that ‘the policy process is permeated by ideas about what is the best course of action and by beliefs about how to achieve goals’. In EU studies, as well as in leadership studies, scholars increasingly focus on the ways in which political leaders’ beliefs and ideas influence their politics and policymaking (Crespy and Schmidt Citation2014; Van Esch and Swinkels Citation2015). The EU, as a political system, is characterised by polycentric governance that is shaped by actors from a wide spectrum of backgrounds and ideologies (’t Hart Citation2014; Tömmel and Verdun Citation2017). This leaves considerable space for belief contestation, especially in times of crisis.

Beliefs

In this study, a belief is defined as a perceived relationship between a cause and an effect (Jervis Citation2006). A collection of beliefs about a certain phenomenon (e.g. about the economy, politics, the environment, or foreign policy) form the core meaning of a belief dimension. For example, an economic belief dimension is a collection of an individual’s beliefs about what they consider to be an appropriate economic philosophy (e.g. a focus on economic stimulus or austerity). A political belief dimension, conversely, is a collection of beliefs about what an individual considers to be an appropriate political philosophy (e.g. conservative or liberal). The sum of all these belief dimensions forms a belief system that helps an individual to make sense of how the world works and how certain ends should be achieved (Van Esch Citation2007).

Belief change

Changes in political leaders’ beliefs may have important political consequences. They may, for instance, alter leaders’ political agendas and exacerbate or resolve deadlocks in political decision-making processes. Such belief changes can be characterised in terms of the object that is subject to change, the nature of the change process, and the direction in which change occurs. Each of these will be discussed, in order.

The belief that is subject to change can either pertain to the size of a belief dimension or to the core meaning of beliefs within a certain dimension. Change in the size of a belief dimension implies that a certain dimension in a belief system is strengthened or weakened, relative to other dimensions in a belief system. For example, a leader’s beliefs about the economy may become more or less salient than their beliefs about politics. This type of change is conceptualised as saliency change. Change to the core meaning of beliefs within a certain dimension implies that causal relations within a belief dimension can change, which would lead to a different core meaning of the belief dimension. For example, a leader may change their view about the level at which sovereign debt markets are likely to lose confidence in a government’s economic policy. This is conceptualised as core change.

A wealth of research explores the radical, abrupt, incremental, or gradual nature of changes to beliefs. One key taxonomy conceptualises these different degrees of change as the result of differences in exogenous or endogenous pressure and makes a distinction between fundamental (radical, abrupt) and secondary (incremental, gradual) belief change (Hall Citation1993; Princen and Van Esch Citation2016). Fundamental belief change implies a radical change in existing beliefs as a response to external events, such as a crisis or changes in the context in which political leaders operate (Hall Citation1993; Van Esch Citation2007). This type of belief change is considered to be rare and uncommon. Secondary belief changes are routine and incremental, and are perceived as the result of endogenous activities (Hall Citation1993). Princen and Van Esch (Citation2016) present a third, intermediate degree of belief change: the moving paradigmatic core. This challenges the assumption that fundamental changes only occur as a result of exogenous pressure and that secondary changes occur as a result of endogenous activities. Princen and Van Esch (Citation2016) show that core beliefs can change as a reaction to external events, without completely altering existing dominant beliefs. Their study on the European Commission’s beliefs on the Stability and Growth Pact demonstrates that the Commission’s beliefs about the economy remain highly ordoliberal, but that, as a result of ‘outside events’, certain elements of the Keynesian paradigm have transitioned into the Commission’s ordoliberal belief system. The literature is not unequivocal concerning the times at which political leaders’ fundamental or secondary belief changes are more likely to occur, as a result of either endogenous or exogenous pressures, which reveals the necessity of a more dynamic approach (Carstensen Citation2011; Princen and Van Esch Citation2016).

Combining insights on both the subject and the nature of political leaders’ belief changes leads to a taxonomy with four possible directions of belief change (). First, the size of a given belief dimension in a belief system can be reinforced or reduced as a result of pressure, resulting in a shift of the surrounding belief dimensions. Second, a belief dimension may either become dominant or cease to exist in the belief system (e.g. a leader stops talking about the economy as a whole). Third, changes pertaining to the core meaning of a belief dimension can transition either from or to the core meaning (the moving paradigmatic core). Fourth, the core meaning of a belief dimension can be completely altered, resulting in a new frame of reference that a leader uses when interpreting events (). Saliency changes at the level of belief dimensions can illustrate which belief dimensions are prioritised by a political leader during times of contextual change. Core-level changes explain changes to the core meaning of a certain belief dimension. Belief stability can occur in both types of changes.

Table 1. Taxonomy of belief change.

Conditions for belief change

Belief change may depend on institutional, contextual, and individual conditions. In situations of multi-fragmented leadership, as is the case with the EU, leaders’ contextual conditions can vary substantially. Differences in, for example, the socio-economic performance of member states or national political constraints can result in diverse responses to a shared systemic crisis (e.g. Bulmer and Paterson Citation2013). Müller and Van Esch (Citation2019) argue that the Eurozone crisis led to significant changes in the exogenous environment of HSG, in terms of both the distribution of welfare and the legitimacy of European publics and member state governments. These exogenous challenges contributed to increasingly complex leadership at the EU level. The study highlights four contextual conditions related to these issues of distribution and legitimacy, which are perceived to influence the individual beliefs of political leaders in the EU.

First, postfunctionalists claim that the preferences of the public and political parties have become a proxy for the process of European integration (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009). The behaviour of foreign policy elites is based on their assumptions about what people find acceptable (Cantir and Kaarbo Citation2016). A constituency’s negative image of the EU can have important implications for belief change, as it impacts the way that political actors talk about and explain a crisis (Hobolt and De Vries Citation2016). Recent studies exploring the sentiment, public interests, and complexity of European speeches given by EU HSG reveal that leaders do, indeed, pander to the Eurosceptic mood of the public at home (Rauh et al. Citation2018). Additional research suggests that governments (and their leaders) change position in response to national public opinion on European integration (Toshkov Citation2011). These findings warrant the expectation that an increase in Euroscepticism may affect a political leaders’ beliefs, as they may feel under pressure to change their beliefs depending on their constituents’ mood. This condition is important to consider in this study, as the impact of the economic crisis extended into a political crisis, and, as such, it threatened the legitimacy of the European Union (Hall Citation2014).

Second, economic performance, namely employment and public debt, may also significantly account for leaders’ belief changes. Unemployment is seen as a politically sensitive issue, and is therefore considered a proxy for experienced economic distress in general (Kessel Citation2015; Vis et al. Citation2012). When confronted with high levels of public debt, leaders must decide whether to reduce or increase public debt policies (Ostry et al. Citation2015). Underperformance leads to increased stress and pressure on leaders to change their beliefs (Van Esch and Swinkels Citation2015). Low levels of debt and rates of unemployment, in contrast, tend to reinforce pre-existing economic beliefs held by political leaders.

Third, leaders in the EU play political games on multiple levels by simultaneously leading a national government and participating in the European Council. The dominant ideology of a leader’s national government can either match that of their counterparts in the European Council or diverge from it. When a political leader’s national government ideology differs from the mainstream ideology of their peers in the European Council, they may be cast as an outsider and feel more pressure to change their beliefs to adhere to the ‘wisdom of the crowd’. This intra-elite contestation may lead to sustained dissonance and hinder decision-making (Hardiman and Metinsoy Citation2018; Van Esch Citation2014a). Studies have shown that political leaders of member states feel pressured to push through reforms, despite their national governments’ preferences or ideologies (Culpepper Citation2014; Kickert and Ysa Citation2014; Lynch Citation2015). Ideological differences can serve as a proxy to understanding the stability and change of political leaders’ policy beliefs. For example, ideological alignment between different levels of government explains favourable policy treatments, such as bail-outs or waivers (Fielding et al. Citation2012; Kleider et al. Citation2018; Nelson Citation2014).

From monocausal explanation to theoretical integration

An uneven focus that favours one condition over others can lead to an incomplete understanding of the ways in which belief changes occur. It is more likely that a myriad conditions affect political leaders’ belief changes (Cuhadar et al. Citation2017). This paper argues that the four conditions it presents do not operate independently, and must instead be examined and understood in relation to each other. We expect that the propensity for belief change is most likely when all conditions are present. The approach taken is a theoretical integration of these conditions, which attempts to understand how their different configurations can lead to the outcome of belief change (Mello Citation2017).

Research design

Case selection

It is important to study the beliefs of the HSG in the European Council, as there was a significant degree of freedom for the HSG to (re)act to the Eurozone crisis. The leaders of the European Council possessed both formal and informal power resources. Furthermore, they had the ability to make decisive contributions to the handling and outcome of the Eurozone crisis. Due to the absence of formal crisis management procedures and mechanisms, HSG leaders served as first responders and relied on their skills to deal with the crisis (Greenstein Citation1969).

This study selects HSGs in the European Council that can be characterised as ‘most different’, on the basis of four criteria (see ). The first criterion is variation in terms of varieties of capitalism. Hall (Citation2014) argues that countries with a focus on demand-led growth models have faced more negative distributive consequences from the Economic and Monetary Union than countries with a focus on export-led growth models, and, as such, these countries are more likely to face economic pressure in a crisis. The second criterion is variation in terms of Eurozone membership. Countries with the euro currency are likely to face more economic pressure than countries outside the Eurozone. The third criterion is variation amongst member states’ governments, in terms of political ideology. Differences in ideology imply that governments hold different preferences with regard to questions of distribution, which can cause growing dissensus about policy aims and actions. The last criterion is differences in growing Euroscepticism, as leaders with ‘dismissive dissensus’ have to deal with growing political constraints.

Table 2. Overview of selected political leaders and time in office.

Conversely, these leaders shared a responsibility to exercise leadership and had to (re)gain the trust of financial markets and their member states in order to find a way out of the crisis. As Höing and Kunstein (Citation2019) assert, the Eurozone crisis can be interpreted as a crisis of trust. Two critical junctures in the Eurozone crisis are identified as pivotal in (re)gaining trust, yet these had the potential to present leaders with changes in their exogenous environments, thus challenging their beliefs (Brunnermeier et al. Citation2016; Van Esch et al. Citation2017). The establishment of the first bail-out package and the setup of the contours of the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), 7–10 May 2010, represents the first juncture. These two rescue mechanisms served as a financial backstop. Economic and Financial Affairs Council (ECOFIN) leaders agreed on a mechanism of financial aid to assist countries like Greece, in order to prevent further escalation and to prevent effects extending to other countries. The second juncture of the Eurozone crisis was Mario Draghi’s ‘Whatever It Takes’ speech on 26 July 2012. At this time, government bond spreads had reached unprecedented heights, which led to speculation about a possible Eurozone collapse. In response, the European Central Bank (ECB) announced the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) programme to prevent further escalation of the crisis. These two events were both explicit cases of leadership by EU institutions, and were identical in terms of addressing questions of trust. Both these decisions were intended to calm markets and stabilise the economy (Höing and Kunstein Citation2019). Economically, the effect of these decisions seemed to stabilise European and global financial markets. Thus, it is reasonable to expect the effect on belief changes to be similar. As a result of choices for selecting cases, 12 HSG were included in the analysis ().

Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA)

QCA facilitates a systematic comparison of the characteristics of specific cases, in order to reveal patterns in data (Schneider and Wagemann Citation2012). When using QCA, causation is perceived as complex. This means that conditions do not compete for more or less variation in an outcome; instead, different configurations are equifinal alternatives for one another. In addition, conditions that explain an outcome can differ from conditions that explain the absence of the outcome (asymmetry). Furthermore, the effect of one condition cannot be isolated from others (conjunctural causation) (Mello Citation2017). This study uses this method to explore the ‘presence of logical implications or set relations in terms of necessity and sufficiency’ (Thomann and Maggetti Citation2017: 5).

This study employs a realist, or substantive interpretability, approach to explanation (Schneider Citation2018; Thomann and Maggetti Citation2017). The purpose of studies following the substantive interpretability approach is ‘to find meaningful super- and/or subsets of the phenomenon to be explained’ (Schneider Citation2016: 2). Analysing sufficient conditions involves assessing the plausibility of counterfactual assumptions. According to this approach, conservative or intermediate solutions are optimal when dealing with counterfactuals. Furthermore, the selected necessary conditions in this approach are interpreted as crucial explanatory factors, without which a given event could not have occurred (Thomann and Maggetti Citation2017). This approach is subsequently used in this study to understand how theoretical knowledge about belief change ensues empirically.

This paper uses a fuzzy-set QCA to examine the possible relationships between the four conditions (unsustainable debt, increased unemployment, different ideology, and increased Euroscepticism) and the outcomes of core and salient belief changes. FsQCA has been chosen for this study because it allows for partial membership in sets (Mello Citation2017), which is advantageous considering the different degrees of belief changes analysed (e.g. U-turns and moves from or towards other core beliefs or belief dimensions). Fuzzy sets use ‘corners’ of a multidimensional property space to establish possible configurations that produce an outcome. The four conditions in this study lead to 24 corners, which yield 16 possible paths to the outcome. To create the fuzzy sets, raw data on belief changes and the four conditions was transformed into fuzzy data via calibration, including the setting of qualitative breakpoints (Schneider and Wagemann Citation2010). The direct method of calibration was used for all four conditions and for the two outcome conditions (salient belief change and core belief change). Direct calibration is the use of a logistic function to transform the raw data into fuzzy-set data. These breakpoints were set in line with theoretical and substantive knowledge.

R QCA and SetMethods packages (Dușa Citation2019; Medzihorsky et al. Citation2018) were used to analyse the fuzzy-set data.Footnote2 Consistency and coverage measurements (varying between 0 and 1) were used to assess necessary and sufficient conditions.Footnote3 Consistency measurements provide a measurement to assess the extent to which the solution is a subset or superset of the outcome. A high consistency score indicates that all cases in a truth table row are the result of a particular configuration. This score is used to determine the inclusion and exclusion of truth table rows in the logical minimisation procedure. Coverage measurements describe the empirical importance of sufficient conditions, or the relevance of necessary conditions. A higher score indicates that the ‘consistent part of the solution overlaps with the outcome’ to a high degree (Schneider and Wagemann Citation2012: 130).

Measurement and calibrationFootnote4

Belief change

Data for belief changes derives from the TransCrisis Comparative Cognitive Mapping (CCM) database (Van Esch et al. Citation2017). The CCM method has been specifically developed to capture causal beliefs in the speeches of political leaders (Van Esch et al. Citation2016).Footnote5 Although alternative methods of measuring beliefs exist, such as operational code analysis, this study uses CCM data to analyse beliefs about a specific topic (the economy) in order to capture change (see Van Esch Citation2007). CCM data was used for the beliefs of the 12 leaders in this study; specifically, data capturing a leader’s beliefs about their preferred economic philosophy (Keynesian or ordoliberal). The central tenet of Keynesian beliefs is a focus on economic stimulation via government intervention, for the purpose of increasing employment rates and economic growth. The central tenet of ordoliberal beliefs is a belief in the primacy of price stability and in the ability to achieve stability via strict budgetary and fiscal policies, central bank autonomy, and by prioritising support for economic objectives over political ones (Princen and Van Esch Citation2016). Cognitive maps were constructed for each leader: one prior to a critical juncture (map 1) and one after (map 2).

These maps served as the basis for calculating belief changes (see Online Appendix A Supplementary material). Analysing all maps at t1 and t2, belief changes in this study are observed through qualitative analysis of the map, when the core meaning of beliefs is either moving in another direction or when the existing core meaning of beliefs is altered.

No QCA research exists on CCM data of political leaders, which means that this paper could not utilise existing anchors to define set membership. The anchors were instead defined following an appraisal of the quantitative data, an evaluation of the cognitive maps, and the conclusions of a prior descriptive study on the belief changes of these political leaders (Van Esch et al. Citation2017). The quantitative data on belief changes and the underlying cognitive maps showed large gaps in the numerical data on belief changes, and, as such, these gaps were used as the bases for the thresholds of calibration (see De Block and Vis Citation2018). The threshold for full inclusion (1.0) in the set belief change of the economic dimension was fixed at 10%. Thus, cases that display at least 10% change in economic beliefs are fully in the set of belief change. The point of indifference was fixed at 5.5% and the threshold for being fully out of the set (0) was fixed at 2% (see online appendix, Table B.1, Supplementary material).

With regard to the core belief changes, qualitative appraisal of the Cognitive Mapping data signalled a difference between the cognitive maps of Danish Prime Minister (PM) Lars Løkke Rasmussen and Italian PM Mario Monti. Where Rasmussen remains a committed Keynesian (change of 8.21% in his maps), Monti’s maps show a move from one predominant set of beliefs to another (change from 9.5%) (see online appendix, Table B.2, Supplementary material). On the basis of these observations, the threshold for full inclusion (1.0) in the set core belief change was fixed at 18%. Cases that display at least 18% change in core beliefs are fully in the set of core belief change. The point of indifference was placed at 9% and the threshold for being fully out of the set (0) was placed at 0% (see online appendix, Table B.2, Supplementary material).

Conditions

Cases can display membership in four sets: unsustainable debt (DT), increased unemployment (UNI), deviating government ideology (GD), and increased Euroscepticism (EI). Data for these four conditions was derived from Eurostat (Eurostat Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2018c) and the Comparative Political Data Set (Armingeon et al. Citation2018a, Citation2018b). The rationale for calibration for these four sets is discussed below. shows the thresholds for full inclusion and full exclusion, as well as the crossover point of the four conditions.

Table 3. Threshold set membership scores (calibration).

Despite the complex relationship between public debt and economic growth, it has been found that countries with national debt levels of 90% or higher may not be able to fulfil their future liabilities (Herndon et al. Citation2014; Reinhart and Rogoff Citation2010; Vis et al. Citation2012). The threshold for full inclusion (1.0) in the unsustainable debt set (DT) is therefore set at 90%. This is also higher than the average EU reported value for all 28 member states (EU28) (Eurostat Citation2018a). The threshold for being fully out of the set (0) is set at 60%, as this means full compliance to the rules of the Stability and Growth Pact.

Qualitative anchors for the unemployment condition do, conversely, exist (see Kessel Citation2015). As this study is primarily concerned with increases in unemployment, rather than the height of unemployment, thresholds for inclusion have been adjusted to fit the study’s purpose. However, Kessel’s (Citation2015) choice to work with averages is used here to determine the thresholds for the increased unemployment set (UNI) (see ). Increases in unemployment figures over time were calculated for the EU28. The average increase served as the point of indifference. The standard deviation marked the thresholds for inclusion and exclusion in the set.

Increased negative support for the EU (EI) is operationalised using an item in the biannual Standard Eurobarometer (see Rauh et al. Citation2018). This item asks respondents the following question: ‘In general, does the European Union conjure up for you a very positive, fairly positive, neutral, fairly negative, or very negative image?’ (Eurostat Citation2018a). The average increase over the date range of this study, for all EU28 countries, is used as the basis for a country’s fuzzy-set scores. Notable examples of countries where political leaders faced increased levels of negative support for the EU include the crisis-stricken countries of Spain, Ireland, and Italy. The data reveals little about the level of Euroscepticism per se, but explains the rise or decline in negative support, which in turn forces political leaders to adjust their positions to changing circumstances.

Ideological difference (GD) is operationalised as the ideological distance of a member state government from the dominant government orientation in the EU as a whole, per given year. For differences in ideological orientation, a distance of more than one category of the average EU government ideology was considered a ‘deviation’, signifying that a case displays set membership. For example, while in office, Rasmussen’s government was coded as a right-wing party hegemony. This mostly aligns with the EU’s dominant government orientation at this time, leading to a deviation score of 0.66 (signifying no set membership).

Results

This section describes the HSG’s belief changes that were observed in this study. The subsequent QCA analysis identifies the necessary and sufficient configurations of conditions that explain these belief changes.

The 2010 rescue mechanism: re-establishing trust in financial markets

Of the five HSGs in office at the time of the 2010 decision to create a financial backstop, French President Nicolas Sarkozy and Spanish PM José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero changed their core beliefs about the economy. Both shifted from Keynesian to ordoliberal beliefs in the period after May 2010 (). Zapatero lost an election soon after, as a result of this U-turn in his beliefs about economic policy, with voters blaming him for bending under EU pressure (Bosco and Verney Citation2012). In his book El Dilemma, Zapatero elaborates on the pressure to change his beliefs and the difficulty of withstanding the pressure from his EU colleagues (Rodríguez Zapatero Citation2013). For Sarkozy, Anglo-American media scrutiny of his economic policies and a loss of France’s triple-A status could have pressured him to adopt a more ordoliberal stance (Van Esch Citation2014b).

Table 4. Belief changes of political leaders.

Conversely, German Chancellor Merkel, Irish PM Cowen, and Danish PM Rasmussen did not change their pre-existing economic beliefs. The absence of belief changes for Cowen is unexpected, considering that he, like Zapatero, faced a worsening socio-economic situation and Irish citizens’ increased dissensus with the EU. Cowen fended off EU pressure to seek financial assistance in November 2010, only to later accept a loan when under pressure from his EU and International Monetary Fund (IMF) partners (Schimmelfennig Citation2015).

Concerning the saliency of economic beliefs, Sarkozy is the only leader in this timeframe who seems to focus less on the economy. The saliency of this dimension in his cognitive maps shows a sharp decrease.

The 2012 outright monetary transaction programme: creating a credible lender of last resort

ECB director Mario Draghi’s promise ‘to do whatever it takes’ was a second decisive moment in the Eurozone crisis, in terms of calming down financial markets and restoring trust (Schoeller Citation2019). In the months and years after, five leaders in this study changed or altered their core economic beliefs. Dutch PM Rutte made a U-turn from predominant ordoliberal to Keynesian beliefs. His focus on concepts such as economic growth, which qualify as Keynesian, can partially explain this U-turn. British PM Cameron’s cognitive maps also reveal a shift from ordoliberal to Keynesian beliefs. Lynch (Citation2015) suggests that this is the result of Cameron’s struggle with differing demands of party politics at home and the pressure of EU leaders to vote in favour of EU policies, in order to combat the crisis. Cameron’s Irish neighbour, PM Kenny, also changes his core beliefs from dominant ordoliberal to Keynesian.

Two other leaders, Italian PM Monti and Spanish PM Rajoy, adopted a more ordoliberal stance in the timeframe after Draghi’s speech. Culpepper (Citation2014) explains Monti’s U-turn as a result of pressure from the EU elite to reform. Again, as with Zapatero, Monti’s changes and subsequent acts were perceived negatively by the Italian electorate in the next election.

The core economic beliefs of the other three leaders, Merkel, Thorning-Schmidt, and Orbán, stayed stable. Thorning-Schmidt remained a committed Keynesian, whereas the beliefs of Merkel and Orbán remained predominantly ordoliberal. Concerning the saliency of economic beliefs, Thorning-Schmidt, Monti, and Rajoy seem to refocus their attention on other topics, as this dimension becomes less salient in their cognitive maps.

To conclude, this data analysis demonstrates that the economic beliefs of EU political leaders either stay stable or decrease after critical junctures. In terms of the core meaning of these beliefs, the Spanish, Italian, and French leaders pivoted towards ordoliberal beliefs, whereas the Irish, Dutch, and UK PMs pivoted towards Keynesian beliefs. The subsequent section analyses what configuration of conditions best explains the occurrence of these belief changes.

Understanding the pathways to belief changes

The prior section illustrates a diverse picture of belief changes. This study’s QCA analysis can subsequently, and systematically, uncover patterns in the data. First, the necessity analysis (Online Appendix D, Supplementary material) reveals that none of the individual conditions have a consistency value of 0.9. This means that none qualify as a necessary (stand-alone) condition for the presence or absence of political leaders’ belief changes in this study. Subsequently, the study conducted necessity analyses for disjunctions of the conditions. These analyses showed consistency values of >0.9 for both salient and core belief change (Online Appendix D, Supplementary material). The results of the analyses for the absence of salient economic belief changes (∼ECOC) and occurrence of core belief changes (KOC) have a coverage value of >0.7, and two findings here are striking. First, for salient economic belief change to not take place, there either has to be no increase in unemployment (∼UNI) or no substantive debt (∼DT) (con. 0.937; cov. 0.720). Second, for core belief change to take place, cases either need to display increased unemployment (UNI) or unsustainable debt (DT) (con. 0.960; cov. 0.719). These findings emphasise the importance of a higher-order concept for belief change: good or bad socio-economic situation. This higher-order concept is necessary for salient belief change to be absent or for core belief change to be present. These necessary disjunctions are ‘crucial explanatory factors, without which a given event could not have occurred’ (Thomann and Maggetti Citation2017: 9) and imply that future analyses of economic belief changes should consider the socio-economic situation of a leader’s country.

Additionally, the study conducted the analysis for sufficiency. First, truth tables for all possible outcomes were constructed (Online Appendix E.1–E.4, Supplementary material). These served as the basis for the logical minimisation procedure (Online Appendix E, Supplementary material). The goal of this procedure is to represent the information in the truth table as a final solution formula, with regard to the different combinations of conditions that produce a specific outcome.Footnote6

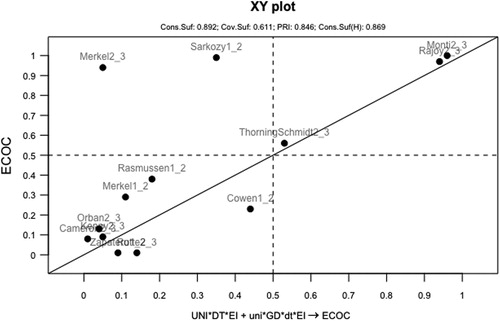

The intermediate solution formula for the presence of economic belief change reveals two combinations that lead to salient belief change. First, the saliency of economic beliefs decreases when leaders face increased unemployment (UNI), unsustainable debt (DT), and increased Euroscepticism (EI). This means that, contrary to what may be expected, when economic and political conditions become increasingly pressured, some leaders will become less vocal about the situation. Second, the saliency of economic beliefs decreases when leaders simultaneously face the absence of increased unemployment (∼UNI), sustainable debt (∼DT), increased Euroscepticism (EI), and a deviant government ideology (GD). The consistency of 0.892 shows that the solution does, indeed, correspond to sufficient combinations, and the coverage of 0.611 indicates that the solution explains a fair share of the outcome of belief change (see ).Footnote7

Three out of 13 cases hold membership in this solution formula (Monti, Rajoy, and Thorning-Schmidt) and can thus be considered typical cases. The difference in configurations for these cases most likely relates to differences in membership type (Denmark’s Thorning-Schmidt as non-Eurozone versus Monti and Rajoy as Eurozone members). The cases of Merkel (before and after critical juncture 2) and Sarkozy show membership in the fuzzy set, but not in the solution term. These are deviant cases in terms of coverage, meaning that they are consistent with the outcome but not with the solution (Schneider and Rohlfing Citation2013). The case of Merkel before and after critical juncture 2 can be considered a typical deviant case for coverage. This case is examined in more detail below.

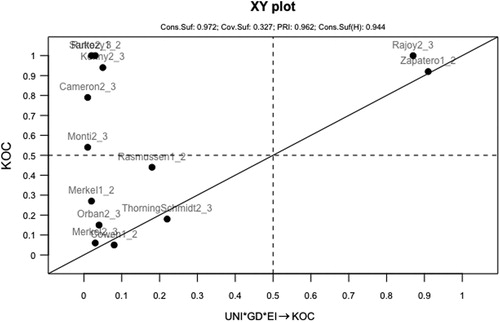

For the outcome of Keynesian/ordoliberal belief change, the intermediate solution shows that a shift in the core meaning of economic beliefs can be explained by a combination of increased unemployment (UNI), a different ideology (GD), and increased Euroscepticism (EI). The consistency score of 0.972 provides evidence that this path corresponds to a sufficient combination. However, the low coverage of 0.327 indicates that these paths only explain a small part of the outcome (see ).

The analysis reveals a sufficient pathway for the core belief changes of Spanish PMs Rajoy and Zapatero but fails to explain the core belief changes of Monti, Cameron, Kenny, Rutte, and Sarkozy. These latter five cases are deviant cases for coverage. Reviewing the truth table (Online Appendix E.3, Supplementary material) illustrates that the cases of Monti and Sarkozy come closest to the ‘ideal deviant case coverage’ and thus warrant further in-depth analysis.Footnote8

There are a number of possible explanations for the three typical deviant cases for coverage in this study. For salient economic changes, the decrease in saliency of Merkel’s economic dimension can best be explained by the prevailing European discourse that became more focused on fiscal issues than monetary issues (Van Esch Citation2014b). The development of this broader EU discourse significantly reduced the saliency of Merkel’s economic beliefs in the period after the announcement of the OMT programme. This alternative explanation hints at the importance of investigating the interaction between the broader European discourse and individual belief change.

In terms of core belief changes, those of Monti and Sarkozy warrant further analysis. Culpepper (Citation2014) characterises Italy under Monti as an ‘unmediated democracy’ and as a country run by a ‘government of professors’ (1275). This situation made it possible for Monti to adopt unpopular austerity programmes and act in line with pressure from EU elites. Monti seemed, at the time, more concerned with steering the economy than with the domestic political situation (Culpepper Citation2014). Therefore, it is likely that Monti, an economics professor by training, changed his beliefs as a result of the pressure to reform from EU leaders and his own ‘objective’ economic analysis of the situation. This alternative explanation emphasises the need for more country-specific and leader-specific analyses in the study of belief changes.

Schoeller et al. (Citation2017) and Van Esch (2014) offer an alternative explanation for Sarkozy’s U-turn from Keynesian to ordoliberal beliefs. The emergence of the ‘Merkozy duumvirate’ (Schoeller et al. Citation2017: 1211) at the onset of the Eurozone crisis may indicate that Sarkozy changed his beliefs in order to form a powerful leadership in tandem with Chancellor Merkel. Furthermore, Sarkozy’s Keynesian beliefs about the economy in 2010 were geared towards monetary issues rather than fiscal issues. As the broader EU discourse shifted to fiscal policies, his core beliefs may consequently have been more malleable (Van Esch Citation2014b). A combination of the ‘Merkozy’ emergence and Sarkozy’s potentially malleable beliefs provide a logical explanation for his U-turn, subsequently implying that studies of belief change should also tailor the roles played by alliances and networks.

Conclusion

This study opened with a quote from George Bernard Shaw (Citation1944: 330) stating that ‘progress is impossible without change; and those who cannot change their minds, cannot change anything’. The study examined under what conditions such a ‘changing of the mind’ of European HSG occurred in the Eurozone crisis. These conditions are unsustainable debt, increases in unemployment, different ideologies, and increases in negative support for the EU. The analysis established that no stand-alone condition is necessary or sufficient to explain the outcome of belief changes. It also demonstrated that either unsustainable debt or increased unemployment is a necessary disjunction for the occurrence of core belief changes. This conclusion implies that the socio-economic situation of a leader’s country is a necessary, higher-order concept for the study of leaders’ belief changes.

For salient belief changes to occur, the analysis illustrated that two paths lead to the outcome. First, for leaders of countries in the Eurozone, the combination of increased Euroscepticism, increased unemployment, and unsustainable debt provides a sufficient explanation. For non-Eurozone leaders, the configuration of increased Euroscepticism combined with different government ideology, sustainable debt, and no increases in unemployment provides a sufficient explanation. This result implies that differences in Eurozone membership type impact contextual conditions’ levels of importance, in terms of the occurrence of belief changes.

For core belief changes to occur, the analysis indicated that a combination of increased unemployment, different ideology, and increased Euroscepticism provides a sufficient explanation. In sum, these results bear implications for theories of belief change. This article thus adds to literature suggesting that contextual causes for belief change are the result of configurations of conditions, rather than the result of one condition being more explanatory than another. The empirical analysis strongly urges scholars to further examine configurational hypotheses.

Furthermore, the study only illustrated the sufficient paths to belief change in a limited number of cases. Further in-depth analysis of typical deviant cases is thus necessary to provide coverage. In-depth analyses of the Merkel, Sarkozy, and Monti cases suggest four possible alternative explanations for belief changes to occur: the influence of the broader European discourse on political leaders’ economic beliefs, country-specific conditions, such as size or government type, leader-specific conditions, such as leadership role or leaders’ personalities, and the influence of alliances and networks on belief change.

This study also has broader implications for our understanding of leadership in foreign policy crises, particularly from a theoretical, empirical, and EU-specific angle. In terms of the theoretical angle, the conceptual model of belief change contributes to role theory in foreign policy analysis, as it can help to further unpack responses of ‘state agents’ to contextual changes (Cantir and Kaarbo Citation2016).

Empirically, conclusions about these four conditions are relevant for different types of foreign policy crises (e.g. military, political). Although it can be argued that these four specific conditions are more typical for economic crises, they also relate to broader ideas about the importance of understanding the role of the domestic arena in foreign policy crises.

Finally, the findings of this study are more applicable to EU foreign policy crises (e.g. Brexit, the migration crisis, the Ukraine crisis) than to foreign policy crises between unitary states. The Eurozone crisis took place in a transboundary institutional arrangement that urged governments to act together; yet, at the same time, they were being pushed apart as a result of differences amongst them (Youngs Citation2013). As EU leaders are compelled to cooperate in times of foreign policy crisis, the nexus between their own domestic arena and EU-level leadership expectations may necessitate different mechanisms for belief change than foreign policy interactions between single states.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (210.4 KB)Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the valuable comments of and exchange of ideas with all the participants of the ECPR Workshop on ‘The Role of Leadership in EU Politics and Policy Making’, held at Nicosia, Cyprus, 10–14 April 2018. A special thanks goes out to the two anonymous reviewers of this paper who gave incredibly detailed and constructive feedback that helped to improve the quality of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marij Swinkels

Marij Swinkels is a PhD candidate and lecturer at the Utrecht University School of Governance. Her research interests include political leadership, ideas, crisis management and Eurozone governance. Her work has appeared in West European Politics, The International Journal of Emergency Management, and in several edited volumes on leadership and crisis management. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 These leaders are Lars Løkke Rasmussen (DK), Helle Thorning-Schmidt (DK), Nicolas Sarkozy (FR), Angela Merkel (DE), Victor Orbán (HU), Brian Cowen (IE), Enda Kenny (IE), Mario Monti (IT), Mariano Rajoy (ES), José Luis Zapatero (ES), Mark Rutte (NL), and David Cameron (UK).

2 R Scripts for both analyses can be found in Part C of the online appendix (Supplementary material). The Analysis performed in this study is Standard Analysis.

3 A consistency score of 1 or 0 represent perfect consistency for a given row. A consistency score of 0.5 displays perfect inconsistency.

4 For an elaborate discussion on the raw data of this study, see Online Appendix A (Supplementary material).

5 See Online Appendix A (Supplementary material) for an explanation of the Cognitive Mapping Method and its subsequent analysis. Data files available upon request. Contact the author.

6 The solution presented here is the intermediate solution. For an overview of all three solutions (parsimonious, complex, and intermediate), see Online Appendix F (Supplementary material).

7 Cons.suf = measure to assess the extent to which the solution is a subset or superset of the outcome. A high consistency score indicates that all cases in a truth table row are the result of a particular configuration; Cov.suf = describes the empirical importance of sufficient conditions; PRI = proportional reduction in consistency; Cons.suf(H) = adjusted consistency measure.

8 The analyses of and solutions for the negated outcomes are presented in Online Appendix F (Supplementary material).

References

- Armingeon, Klaus, Virginia Wenger, Fiona Wiedemeier, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler (2018a). Comparative Political Data Set 1960-2015 [Dataset], available at http://www.cpds-data.org (accessed 4 June 2018).

- Armingeon, Klaus, Virginia Wenger, Fiona Wiedemeier, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler (2018b). Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set: Government Composition 1960-2015 [Dataset], available at http://www.cpds-data.org/ (accessed 4 June 2018).

- Blyth, M. (2002). Great Transformations: Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Boin, Arjen, Paul’t Hart, Eric Stern, and Bengt Sundelius (2017). The Politics of Crisis Management: Public Leadership under Pressure. New York: Cambridge.

- Bosco, Anna, and Susannah Verney (2012). ‘Electoral Epidemic: The Political Cost of Economic Crisis in Southern Europe’, South European Society and Politics, 17:2, 129–54.

- Brummer, Klaus (2016). ‘“Fiasco Prime Ministers”: Leaders’ Beliefs and Personality Traits as Possible Causes for Policy Fiascos’, Journal of European Public Policy, 23:5, 702–17.

- Brunnermeier, Markus Konrad, Harold James, and Jean-Pierre Landau (2016). The Euro and the Battle of Ideas. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Bulmer, Simon, and William E. Paterson (2013). ‘Germany as the EU's Reluctant Hegemon? Of Economic Strength and Political Constraints’, Journal of European Public Policy, 20:10, 1387–405.

- Cantir, Cristian, and Juliet Kaarbo, eds. (2016). Domestic Role Contestation, Foreign Policy, and International Relations. London: Routledge.

- Carstensen, Martin B. (2011). ‘Paradigm Man vs. The Bricoleur: Bricolage as an Alternative Vision of Agency in Ideational Change’, European Political Science Review, 3:1, 147–67.

- Crespy, Amandine, and Vivien A. Schmidt (2014). ‘The Clash of Titans: France, Germany and the Discursive Double Game of EMU Reform’, Journal of European Public Policy, 21:8, 1085–101.

- Cuhadar, Esra, Juliet Kaarbo, Baris Kesgin, and Binnur Ozkececi-Taner (2017). ‘Examining Leaders’ Orientations to Structural Constraints: Turkey’s 1991 and 2003 Iraq War Decisions’, Journal of International Relations and Development, 20:1, 29–54.

- Culpepper, Pepper D. (2014). ‘The Political Economy of Unmediated Democracy: Italian Austerity under Mario Monti’, West European Politics, 37:6, 1264–1281.

- De Block, Debora, and, Barbara Vis (2018). ‘Addressing the Challenges Related to Transforming Qualitative Into Quantitative Data in Qualitative Comparative Analysis’, Journal of Mixed Methods Research, Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689818770061.

- Dușa, Adrian (2019). QCA with R. A Comprehensive Resource. New York: Springer International Publishing.

- Dyson, Stephen Benedict (2018). ‘Gordon Brown, Alistair Darling, and the Great Financial Crisis: Leadership Traits and Policy Responses’, British Politics, 13:2, 121–45.

- Eurostat (2018a). Data from: Public Opinion Database Eurobarometer [Dataset]. available at http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/index#p=1&yearFrom=2009&yearTo=2015 (accessed 21 June 2018).

- Eurostat (2018b). Data from: General Government Gross Debt Statistics (sdg_17_40) [Dataset], available at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/en/sdg_17_40_esmsip2.htm (accessed 13 August 2018).

- Eurostat (2018c). Data from: Unemployment statistics (une_rt_q) [Dataset], available at http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Unemployment_statistics (accessed 31 July 2018).

- Fielding, Kelly S., Brian W. Head, Warren Laffan, Mark Western, and Ove Hoegh-Guldberg (2012). ‘Australian Politicians’ Beliefs about Climate Change: Political Partisanship and Political Ideology’, Environmental Politics, 21:5, 712–33.

- Goetz, Klaus H. (2017). ‘Political Leadership in the European Union: A Time-Centred View’, European Political Science, 16:1, 48–59.

- Greenstein, Fred I. (1969). Personality and Politics: Problems of Evidence, Inference and Conceptualization. Chicago, IL: Markham.

- Hall, Peter A. (1993). ‘Policy Paradigms, Social Learning and the State: The Case of Economic Policy-Making in Britain’, Comparative Politics, 25:3, 275–96.

- Hall, Peter A. (2014). ‘Varieties of Capitalism and the Euro Crisis’, West European Politics, 37:6, 1223–43.

- Hardiman, Niamh, and Saliha Metinsoy (2018). ‘Power, Ideas, and National Preferences: Ireland and the FTT’, Journal of European Public Policy, Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1539117

- Helms, Ludger (2014). ‘Institutional Analysis’, in Paul’t Hart and Rod A. W. Rhodes (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Leadership. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 195–210.

- Herndon, Thomas, Michael Ash, and Robert Pollin (2014). ‘Does High Public Debt Consistently Stifle Economic Growth? A Critique of Reinhart and Rogoff’, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 38:2, 257–79.

- Hobolt, Sara B., and Catherine E. De Vries (2016). ‘Public Support for European Integration’, Annual Review of Political Science, 19, 413–32.

- Höing, Oliver, and Tobias Kunstein (2019). ‘Political Science and the Eurozone Crisis. A Review of Scientific Journal Articles 2004–15’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57:2, 298–316.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks (2009). ‘A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus’, British Journal of Political Science, 39:1, 1–23.

- Jervis, Robert (2006). ‘Understanding Beliefs’, Political Psychology, 27:5, 641–63.

- John, Peter (1998). Analysing Public Policy. London: Continuum.

- Kaarbo, Juliet (2018). ‘Prime Minister Leadership Style and the Role of Parliament in Security Policy’, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 20:1, 35–51.

- Kessel, Stijn (2015). Populist Parties in Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kickert, Walter, and Tamyko Ysa (2014). ‘Public Money & Management New Development: How the Spanish Government Responded to the Global Economic, Banking and Fiscal Crisis’, Public Policy and Management, 34:6, 453–57.

- Kleider, Hanna, Leonce Röth, and Julian L. Garritzmann (2018). ‘Ideological Alignment and the Distribution of Public Expenditures’, West European Politics, 41:3, 779–802.

- Lynch, Philip (2015). ‘Conservative Modernisation and European Integration: From Silence to Salience and Schism’, British Politics, 10:2, 185–203.

- Medzihorsky, Juraj, Ioana Oana, Mario Quaranta, and Carsten Q. Schneider (2018). ‘Set Methods: Functions for Set-Theoretic Multi-Method Research and Advanced QCA’, R Package Version 2.3.1. Available at https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/SetMethods/index.html (accessed 16 August 2018).

- Mello, Patrick A. (2017). ‘Qualitative Comparative Analysis and the Study of Non-State Actors’, in Andrea Schneiker and Andreas Kruck (eds.), Researching Non-State Actors in International Security: Theory & Practice. London: Routledge, 123–42.

- Müller, Henriette, and Femke Van Esch (2019). ‘The Contested Nature of Political Leadership in the European Union: Conceptual and Methodological Cross-Fertilisation’, West European Politics, 31:6, 1103–28.

- Nelson, Stephen C. (2014). ‘Playing Favorites: How Shared Beliefs Shape the IMF’s Lending Decisions’, International Organization, 68:2, 297–328.

- Ostry, Jonathan D., Atish R. Ghosh, and Raphael Espinoza (2015). ‘When Should Public Debt Be Reduced?’. International Monetary Fund, available at https://doi.org/https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2015/sdn1510.pdf. (accessed 29 October 2018).

- Princen, Sebastiaan, and Femke Van Esch (2016). ‘Paradigm Formation and Paradigm Change in the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact’, European Political Science Review, 8:3, 355–75.

- Rauh, Christian, Bart Joachim Bes, and Martijn Schoonvelde (2018). ‘Undermining, Defusing, or Defending European Integration? Assessing Public Communication of European Executives in Times of EU Politicization’, European Journal of Political Research, Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12350.

- Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth S. Rogoff (2010). ‘Growth in a Time of Debt’, American Economic Review, 100, 573–78.

- Rodríguez Zapatero, José Luis (2013). El Dilema: 600 Días de Vértigo. Madrid: Planeta.

- Schimmelfennig, Frank (2015). ‘Liberal Intergovernmentalism and the Euro Area Crisis’, Journal of European Public Policy, 22:2, 177–95.

- Schneider, Carsten Q. (2016). ‘Real Differences and Overlooked Similarities’, Comparative Political Studies, 49:6, 781–92.

- Schneider, Carsten Q. (2018). ‘Realists and Idealists in QCA’, Political Analysis, 26:2, 246–54.

- Schneider, Carsten Q., and Claudius Wagemann (2010). ‘Standards of Good Practice in Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Fuzzy-Sets’, Comparative Sociology, 9:3, 397–418.

- Schneider, Carsten Q., and Claudius Wagemann (2012). Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences: A Guide to Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schneider, Carsten Q., and Ingo Rohlfing (2013). ‘Combining QCA and Process Tracing in Set-Theoretic Multi-Method’, Sociological Methods and Research, 42:2, 559–97.

- Schoeller (2019). ‘Tracing Leadership. The ECB’s “Whatever It Takes” and Germany in the Ukraine Crisis', West European Politics. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1635801

- Schoeller, Magnus, Mattia Guidi and Yannis Karagiannis (2017). ‘Explaining Informal Policy-Making Patterns in the Eurozone Crisis: Decentralized Bargaining and the Theory of EU Institutions’, International Journal of Public Administration, 40:14, 1211–22.

- Shaw, George Bernard (1944). Everybody’s Political What’s What? London: Constable and Company Limited.

- ’t Hart, Paul (2014). Understanding Public Leadership. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Thomann, Eva, and Martino Maggetti (2017). ‘Designing Research With Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA)’, Sociological Methods & Research, Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124117729700

- Tömmel, Ingeborg, and Amy Verdun (2017). ‘Political Leadership in the European Union: An Introduction’, Journal of European Integration, 39:2, 103–12.

- Toshkov, Dimiter (2011). ‘Public Opinion and Policy Output in the European Union: A Lost Relationship’, European Union Politics, 12:2, 169–91.

- Van Esch, Femke (2007). ‘Mapping the Road to Maastricht: A Comparative Study of German and French Pivotal Decision Makers’ Preferences Concerning the Establishment of a European Monetary Union during the Early 1970s and Late 1980s’, unpublished Phd. Thesis, Nijmegen: Radboud University Nijmegen, Faculty of Management Sciences.

- Van Esch, Femke (2014a). ‘A Matter of Personality? Stability and Change in EU Leaders’ Beliefs during the Euro Crisis’, in D. Alexander and J. Lewis (eds.), Making Public Policy Decisions: Expertise, Skills and Experience. London: Routledge, 53–72.

- Van Esch, Femke (2014b). ‘Exploring the Keynesian-Ordoliberal Divide. Flexibility and Convergence in French and German Leaders’ Economic Ideas During the Euro-Crisis’, Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 22:3, 288–302.

- Van Esch, Femke (2017). ‘The Nature of the European Leadership Crisis and How to Solve it’, European Political Science, 16:1, 34–47.

- Van Esch, Femke, and Marij Swinkels (2015). ‘How Europe’s Political Leaders Made Sense of the Euro Crisis: The Influence of Pressure and Personality’, West European Politics, 38:15, 1203–25.

- Van Esch, Femke, Rik Joosen, Sebastiaan Steenman, and Marij Swinkels (2016). ‘D3.1 Cognitive Mapping Coding Manual’, available at https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/358307 (accessed 10 May 2017).

- Van Esch, Femke, Sebastiaan Steenman, and Rik Joosen (2017). ‘D3.3 Making Meaning of the Euro-Crisis’, available at https://www.transcrisis.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Deliverable-3.3-Meaning-Making-of-the-Euro-Crisis.pdf (accessed 10 May 2017).

- Vis, Barbara, Jaap Woldendorp, and Hans Keman (2012). ‘Economic Performance and Institutions: Capturing the Dependent Variable’, European Political Science Review, 4:1, 73–96.

- Youngs, Richard (2013). The Uncertain Legacy of Crisis: European Foreign Policy Faces the Future. Washington, DC: Carnegie Europe.