Abstract

In recent decades, a new integration-demarcation cleavage has emerged in Europe, pitting political parties in favour of globalisation against those opposing globalisation. Although a lot is known about the socio-structural basis and the political organisation of this cleavage, we do not know the extent to which these political divides have led to social divides. Therefore, this article investigates how losers and winners of globalisation oppose each other. On the basis of representative online experiments in Germany and Austria, this article studies attitudes and behaviour towards people with different nationalities, education, and party preferences, which correspond to the cultural, socio-structural, and organisational elements of the new cleavage. More particularly, the extent to which people are willing to interact with each other in daily life and how much they trust each other is investigated. The main results show that people who identify with different parties (especially if they belong to the other side of the cleavage) oppose each other much more strongly than people with different nationalities. There is no divide, however, between the low-skilled and high-skilled. Finally, it appears that the social divides are asymmetrical: the winners of globalisation resent the losers more than the other way round.

The rise of right-wing populist parties in Western Europe over the last decades has led to fierce political debate over issues of denationalisation and the question of whether or not national borders should be opened or closed, and whether or not globalisation brings more advantages than disadvantages. As Kriesi et al. have shown, globalisation has changed the political structure in Western Europe and has led to the emergence of the new integration-demarcation cleavage, which pits those who profit from globalisation against those who do not (Kriesi et al. Citation2008, Citation2012). Although we already know a lot about the existence of this cleavage at the political level and on how parties position themselves around it, we do not know to what extent these political divides also exist as social divides between the (real or potential) winners and losers of globalisation. Having different political convictions does not necessarily mean that voters of different parties dislike each other. Or could it be that right-wing populist voters prefer not to interact with voters of parties in favour of more open borders in their daily life and vice versa?

The existence of such social tensions would tell us something about the salience of this cleavage. If people not only disagree with others on their political views but also do not want to have them in their neighbourhood or among their friends, we can speak of a particularly strongly embedded cleavage. The main goal of this article is thus to find out whether such social divides exist and how strong they are, resulting in a more comprehensive understanding of the new political cleavage.

Following the literature in this field, we define losers of globalisation as those who see their opportunities in life diminished as a result of globalisation. Often, this group are characterised as being less educated, opposing migration and supporting populist parties. In contrast, winners of globalisation are those who see their life chances improved through globalisation. Usually, these individuals are found among the more highly educated; they tend to be in favour of migration; and they support non-populist parties (e.g. Azmanova Citation2011; Hobolt Citation2016; Rooduijn Citation2015; Steenvoorden and Harteveld Citation2018; Teney et al. Citation2014). Accordingly, in our analyses we investigate how populist/non-populist voters, poorly/highly-educated people, and natives/immigrants position themselves towards each other.

In contrast to the infinite number of studies that for several decades have investigated prejudice against immigrants (Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2014), social divides and more particularly tensions between members of different parties or different educational groups have hardly been studied so far, not even outside the cleavage literature. Kuppens et al. (Citation2018) were the first to provide a systematic analysis of whether and why people evaluate education-based in-groups and out-groups differently. Most research on partisan polarisation investigated attitudes towards different political parties or their candidates in the United States (Levendusky Citation2018; Mason Citation2015; Rogowski and Sutherland Citation2016; Webster and Abramowitz Citation2017). Research on polarisation between voters of different parties is fairly recent, showing that it exceeds discrimination against members of religious, linguistic, racial, ethnic, or regional out-groups (Iyengar and Westwood Citation2015; Mason Citation2018; Westwood et al. Citation2018). In a related field, it has been shown that people with liberal and conservative attitudes oppose each other to the same degree (Brandt et al. Citation2014; Chambers et al. Citation2013; Crawford et al. Citation2017). None of these studies, however, was concerned with political cleavages, because their focus was on specific political or social conflicts between partisan, value-based or educational groups. Although we do adopt some of the individual arguments discussed in these studies and some of their methodologies, we go beyond them by aiming to make a contribution to the cleavage literature and by looking at partisan, national and educational groups together.

We expect the divide between voters of parties on the two sides of the integration-demarcation cleavage to be relatively large—at least as large as that between natives and immigrants—because people are mobilised by political rhetoric consisting to a large extent of hostilities directed at opposing parties. Contrary to other minority traits, there are no social norms that prevent people from expressing negative views towards voters of other parties or people with a different education (Iyengar and Westwood Citation2015: 690; Kuppens et al. Citation2018: 431). Both education and party choice are seen by many as personal choices that may be criticised and opposed.

We also explore the extent to which these divides are asymmetrical in nature. It may be argued that the losers of globalisation dislike the winners much more than the other way round, given that right-wing populists appear as the driving force in current controversies. At the same time, the highly educated winners of globalisation are often seen as being generally tolerant towards minorities. It may also be argued, however, that the winners strongly oppose the losers, because they see their achievements put in danger, especially in the absence of social norms that would prevent them from showing prejudice against out-groups.

In order to test our arguments, we conducted representative online surveys in Germany and Austria in which we included vignette experiments and trust games to measure attitudes and behaviour towards other groups. We show that people who vote for different parties (especially if they belong to the other side of the cleavage) oppose each other much more strongly than people of different nationalities. There is no divide, however, between the low-skilled and high-skilled. Finally, it appears that the social divides are asymmetrical in nature, with the winners of globalisation resenting the losers more than the other way round. The general patterns are the same in Germany and Austria. We find that polarisation is bigger in Germany, however. We conclude by discussing possible reasons for this difference.

Cleavage in-group bias and social distance

Modern societies are characterised by widespread and permanent ‘cleavages’, a specific structure of political conflict that profoundly shapes their political systems (Bartolini Citation2005; Lipset and Rokkan Citation1967). Fully developed cleavages, according to Bartolini and Mair (Citation1990: 213–20), should include three elements: a distinct socio-structural basis such as class or religion, a collective identity, and a particular form of political organisation of this group. In other words, a cleavage is more than just a cluster of social groups with diverging interests. These groups need to be aware of their common interests and develop some form of group consciousness or collective identity. Moreover, some organisational structure is necessary to articulate these interests.

Whereas traditional cleavages of class and religion have declined in importance (Franklin et al. Citation1992), a new integration-demarcation cleavage has been shown to have emerged in Western societies over the last decades, one driven by economic, cultural and political globalisation (Kriesi et al. Citation2008, Citation2012). Increasing transnational economic competition has led to economic risks and feelings of insecurity. Immigration and increasing cultural diversity are often perceived as a threat to one’s national culture. Finally, European integration is regarded by some as a threat to national sovereignty. These processes affect some citizens more than others, or they are perceived differently by different groups, thereby creating a latent structural potential of ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ of globalisation, that is, people who benefit from these processes and those who do not.

Education and social class constitute the crucial socio-structural basis of winners and losers of globalisation, and populist and non-populist parties are the main political actors articulating their respective interests (Kriesi et al. Citation2008, Citation2012). Highly educated people and socio-cultural specialists are more in favour of cultural integration than less-educated people and unskilled workers. Bovens and Wille (Citation2017: 51–2) show that educational differences correlate with cosmopolitan and nationalist attitudes. Stubager (Citation2009, Citation2010) argues that education explains authoritarian and libertarian values in the same way as social class used to explained socialist left and conservative right positions. For these reasons, it has been argued that the educational revolution in the 1960s and 1970s has led to a new cleavage. Stubager (Citation2010) even speaks of an education cleavage. Right-wing populist parties rely much more on low- and medium-educated than highly educated people (Arzheimer Citation2009). At the other end of the political spectrum, green and social-democratic parties mostly attract highly educated voters (Bovens and Wille Citation2017: 53–4). These are the parties that most strongly represent the two sides of the new integration-demarcation cleavage.

Most of the existing literature emphasises the socio-structural and the organisational components of the cleavage. Kriesi et al. (Citation2008, Citation2012), for example, analyse the demand and supply side of the new cleavage, looking at how voters and political parties position themselves towards crucial political issues that make up the integration-demarcation cleavage. The extent to which group consciousness or collective identity exist around this cleavage and how it affects the perceptions of in- and out-groups and interactions between these groups has yet to be shown, however. Thus, there is still little evidence as to what extent the new cleavage is also socially embedded.

We follow social identity group scholars who argue that under the condition of group competition (such as conflicts over globalisation issues), collective identities should lead to the ascription of undesirable traits to persons that do not belong to the in-group (Tajfel Citation1970; Tajfel and Turner Citation1979). This can also be called in-group bias. For if cleavage identities do exist, we should observe that in the process of creating in- and out-groups, they lead to positive views of the self and negative views of the other side of the cleavage (H1a). Such favouritism is not simply based on values, or in our case policy positions, but more generally on a sense of inclusion or exclusion (Brewer Citation2001). In such situations, people are opposed to close interpersonal relationships with out-group members. Accordingly, and accounting for the degrees of social distance (Bogardus Citation1925), we expect different degrees of acceptability that depend on social distance: attitudes towards out-groups become more negative the closer these groups come to the in-group in social terms (H1b).

If a social divide can be expected between winners and losers of globalisation, the question is how strong is it? We expect winners and losers to express more negative attitudes towards the respective out-groups than natives express towards immigrants—one of the most researched social divides—because there are no social norms that prevent people from expressing negative views towards voters of other parties or people with a different level of education (H2) (Iyengar and Westwood Citation2015: 690; Kuppens et al. Citation2018: 431). This stands in stark contrast to constraints that exist regarding ethnicity, religion, gender, disability, sexuality and age. Discrimination based on these characteristics is forbidden by German anti-discrimination law, for example. Chambers et al. (Citation2013) show that prejudice towards ethnic minorities increases even among liberals if these minorities are described as particularly conservative. It thus appears that supposedly tolerant people have no difficulty expressing negative attitudes if the minorities’ political convictions are emphasised.

The absence of such norms in the political context can also be explained by the mobilising political rhetoric that consists, to a large extent, of hostilities directed at opposing parties (Iyengar and Westwood Citation2015: 690). In the light of these everyday struggles among political parties, it seems to be completely acceptable for ordinary voters to express negative attitudes towards partisan out-groups. In fact, negative party identification has had a major impact on political outcomes across the western world (Medeiros and Noël Citation2014), as quite often people define themselves not by who they are but rather by who they are not (Zhong et al. Citation2008). Not only are such negative evaluations more influential than positive ones (Baumeister et al. Citation2001), they also show different causes and effects (Cacioppo and Berntson Citation1994).

With respect to education, Kuppens et al. (Citation2018: 429) argue in a similar vein that ‘attitudes to those with few educational qualifications have become one of the last bastions of ‘acceptable’ prejudice […]’. They go on to say that these negative attitudes might not even be perceived as prejudice, showing in various experiments that the highly educated are perceived (by both highly and less-educated people) as being superior. One reason is that education is seen as the responsibility of the individual. In other words, under a neoliberal perception, a person’s level of education is as much seen as being a matter of personal choice as voting for a political party—accordingly, criticising or opposing such choices is not considered discriminatory behaviour.

Symmetrical or asymmetrical social divides?

Besides the question to which extent such social divides exist, we have also tried to discover whether or not they are symmetrical. Do losers and winners of globalisation dislike each other in equal measure? Two competing arguments are tested. On the one hand, it may be argued that it is mainly the losers of globalisation who create these tensions, meaning they oppose the winners of globalisation more than the other way round (H3a). After all, the rise of right-wing populist parties can first and foremost be seen as opposition to globalisation. Accordingly, the voters of populist right-wing parties oppose those voters they think are responsible for, or benefit from, open borders. As education can be seen as a status marker in modern societies (Spruyt Citation2014) or as symbolic capital indicating competence and respectability (Bourdieu 1979/1984), the highly educated are also perceived more generally as part of the elite and hence serve as the main opponents of right-wing populist parties and voters (Mudde Citation2007). Populist voters may also think of themselves as a group dominated by the cosmopolitan elite, or they feel frustration because they cannot profit from the advantages of globalisation, hence finding themselves in a position where they want to change the power relationship (Stubager Citation2009: 226).

The losers’ stronger opposition towards the winners of globalisation might also be owing to the fact that as members of the dominant group, the highly educated might not even be aware of the conflict between the two groups, being ‘entirely embedded within their own perspective’ (Stubager Citation2009: 226). At the same time, the winners of globalisation possess characteristics that are normally related to tolerance towards out-groups. A large number of studies has already shown that cosmopolitans and highly educated people are more tolerant, especially when it comes to immigrants and ethnic minorities (Flanagan and Lee Citation2003; Hagendoorn and Nekuee Citation1999; Heyder Citation2003; Vogt Citation1997; Wagner and Zick Citation1995). It has been shown that there is generally more intergroup bias among low-status groups than among high-status groups (Mullen et al. Citation1992). One explanation is offered by social identity theory, which says that low-status groups have to work harder to create a positive identity for themselves (Tajfel and Turner Citation1979).

On the other hand, it may also be argued that the losers of globalisation are less opposed towards the winners than vice versa (H3b). Although more highly educated people have often been shown to be less prejudiced towards other groups, we know surprisingly little about the mechanisms behind this effect. Hello et al. (Citation2006) and Halperin et al. (Citation2007) found that open-mindedness and cognitive sophistication hardly play a role. Rather, it is the absence of a perceived threat that leads to more tolerant attitudes. This explains why highly skilled people do not oppose immigrants, who are more often low skilled and do not compete with them in the job market. The losers of globalisation, however, may indeed be perceived as a threat by the winners of globalisation—mostly for cultural reasons, as the losers of globalisation challenge the winners’ cosmopolitan attitudes. Even ethnic minorities may be perceived as a threat if they do not share the winners’ cosmopolitan values (Brandt et al. Citation2014). Material reasons may also play a role, because the winners of globalisation may fear losing the privileges they gained through the process of globalisation. It seems plausible, therefore, that the tolerance of the highly educated is merely an ideological discourse to mask their self-interests (Jackman and Crane Citation1986; Jackman and Muha Citation1984). This disguise may easily disappear in a context where voicing prejudice towards an out-group is less restricted, if at all, by social control, as argued above.

Along the same lines, relative gratification theory assumes that favourable in-group comparison also leads to increased prejudice (Dambrun et al. Citation2006; Guimond and Dambrun Citation2002). Considered the inverse of relative deprivation (LeBlanc et al. Citation2015), favourable in-group comparison describes a certain privilege awareness (Kawakami and Dion Citation1995; McIntosh Citation2012) that leads people to develop stereotypes against out-groups and ethnic minorities in particular (Guimond and Dambrun Citation2002). Most likely, individuals with higher social or economic status tend to stigmatise low-status groups in order to justify inequality and their current privileges (Crocker et al. Citation1998), which is in line with social dominance theory (Sidanius and Pratto Citation1999) and system justification theory (Jost and Banaji Citation1994). Prejudice is considered an insurance policy that helps to support group-based hierarchy and in-group hegemony (LeBlanc et al. Citation2015). In addition, oppression of those with low status can serve simultaneously to benefit the group (i.e. by maintaining the status quo) and the individual (i.e. their within-group status, trust, and influence). Thus, privileged individuals might act strategically to secure specific objectives within their own group, too (Postmes and Smith Citation2009). This asymmetric relationship might be amplified by the fact that even the lower-educated see their lack of education as an undesirable trait. Kuppens et al. (Citation2018) have shown that lower-educated people judged their own group to be more responsible for their disadvantaged situation.

In sum, the literature suggests that if social divides between winners and losers of globalisation do exist, they are very unlikely to be symmetrical. The extent to which this relationship is in fact asymmetrical, and which cleavage group holds more negative attitudes towards the other group, is an empirical question that will be analysed in the following sections.

Data

Two representative surveys from an online panel executed by the survey firm respondi were fielded in Germany in October 2017 (N = 1229) and in Austria in July and August 2018 (N = 1094).1 Online surveys allow participants to read short vignettes, which we use for our experiments (see below), and are now considered a standard tool in the social sciences, with data quality being comparable to more traditional survey modes (Ansolabehere and Schaffner Citation2014; Yeager et al. Citation2011). Comparing Germany and Austria allows us to generalise our findings. Both countries are very similar in economic and institutional terms and have known extensive mobilisation from the populist right. The two countries can therefore be seen as most likely cases regarding the emergence of the social divides discussed above.

Unfortunately, it is not possible directly to measure cleavage consciousness or collective identities, because survey participants would struggle to answer questions regarding the extent to which they identify with winners or losers of globalisation. Following a large number of studies in this field, we therefore operationalise winners and losers of globalisation on the basis of party choices, attitudes towards immigrants and level of education, which correspond to the organisational, cultural and socio-structural elements of the new cleavage. (e.g. Azmanova Citation2011; Hobolt Citation2016; Rooduijn Citation2015; Steenvoorden and Harteveld Citation2018; Teney et al. Citation2014). Kriesi (Citation2012) shows that it is mainly the parties from the populist right and to some extent also those from the populist left that mobilise losers of globalisation and are thereby the driving forces behind the emergence of the new cleavage, especially around the topics of immigration and European integration. Most other parties on both the moderate left and right support the lowering of national boundaries.2 Dolezal and Hutter (Citation2012) conclude that besides social class, it is education in particular that allows us to distinguish winners from losers of globalisation.

In investigating the strength of these cleavage identities, we follow the literature on affective polarisation (e.g. Iyengar and Westwood Citation2015), which looks at the consequences of collective identities in a competitive setting, namely how much one group opposes another group and thus how strongly people’s attitudes or behaviour towards their own cleavage group and towards the opposing cleavage group differ. In other words, we seek to find out how a person’s attitudes and behaviour change when they are confronted with someone who shares the same characteristics in terms of party preferences, nationality and education, as opposed to a person who does not share them.

We conducted both attitudinal and behavioural vignette survey experiments (see Table A1 in the Online appendix for descriptive statistics and Table A2 for question wording). For the attitudinal dimension of social distance, respondents received one vignette and were presented with persons who either had one of three nationalities (German/Austrian, Italian or Turkish) or were members of national political parties. Turks constitute the largest immigration group in Germany and the third largest in Austria (after Germans and Serbians). In both countries, Italians are among the most important immigration group from Western Europe, and the two groups have led to fierce political debates in the post-WWII period (Italians) and over the last three decades (Turks). Accounting for these two immigrant groups allows us to differentiate between one group that is culturally closer and considered as relatively well integrated (Italians) and one that is culturally more distant and often portrayed as relatively poorly integrated (Turks).

Regarding partisanship, we differentiate between the two most relevant left-wing and right-wing populist parties in Germany, The Left and the Alternative for Germany (AfD), and the two most important moderate left- and right-wing parties, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU).3 We regard both the SPD and the CDU as parties that represent the winners of globalisation. Until the 2000s, the CDU positioned itself on the exclusionist side of the cleavage, especially in terms of culture (Dolezal Citation2008b: 226–31). It belonged to the group of parties with culturally protectionist and nationalist positions similar to newly emerged right-wing populist parties and transformed mainstream parties such as the Dutch VVD or the UK Conservatives (Kriesi Citation2012: 102). Although the AfD failed to enter the national parliament in the 2013 elections, it clearly positioned itself as the dominant nationalist and anti-immigrant party. At the same time, the CDU moved to a more centrist inclusionist position, which is relatively close culturally to that of the SPD (Bremer and Schulte-Cloos Citation2019).

In Austria, we differentiate between the major right-wing populist Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) and the two major moderate parties: the Social Democratic Party of Austria (SPÖ) and the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP). In the absence of an important left-wing populist party in Austria, we included the Green Party in order to also have four parties in Austria to make the survey designs as similar as possible in the two countries. Since the transformation of the FPÖ in the late 1980s, Austria has known one of the first and most successful right-wing populist parties in Europe (Mudde Citation2007: 42). Since the 1999 elections, which led to a coalition between ÖVP and FPÖ and subsequent EU sanctions, Austria has seen a highly polarised configuration between the government parties on the one side and SPÖ and Greens on the other (Dolezal Citation2008a: 126–27). In the 2000s, however, the ÖVP became much more culturally liberal than the FPÖ, similar to some European liberal parties (Kriesi et al. Citation2012: 102).

We did not combine nationality and partisanship, because some combinations would have been rather unrealistic (e.g. Turkish AfD partisans). In all seven categories, however, we differentiated between people of different nationalities or partisanship as having either a university degree or a high school degree. High school degree refers to the German Hauptschule, the lowest secondary school in Germany and Austria. We specifically chose this school type because its negative image heavily polarises public debate. In sum, we thus distinguished between 14 randomly assigned groups. Tables A3a–A4c in the Online appendix provide balance cheques and display the distribution of relevant socio-economic characteristic across all 14 treatment groups.

Each survey respondent received one vignette and was asked on a seven-point scale whether it would cause a problem, for example, if a person with a university degree and Turkish citizenship moved into their neighbourhood, if they had to work with that person, if that person was among their close friends, or if someone from their immediate family would marry that person. The order of these four situations was randomised. These questions allow us not only to compare attitudes towards in- and out-groups but also to see whether attitudes towards out-groups become more negative the closer this group comes to the respondent (Bogardus Citation1925).

In order to test the robustness of our findings and to see how in-group bias also leads to discriminatory behaviour, we ran a second experiment with vignettes similar to the ones used in the attitudinal setting (see Table A2 in the Online appendix for detailed instructions and question wording for this experiment). This time, however, respondents played a trust game, in which they were assigned a fictitious amount of 10 euros. They were then allowed to divide the sum between themselves (player 1) and a hypothetical player 2 (vignette). The amount given to player 2 would be tripled, and player 2 would decide how much money to give to player 1. Player 1 would keep the sum from the first round plus whatever player 2 would potentially assign him in the second round. Respondents were told that higher rewards would indicate greater success in the game.4 As in the previous case, player 2 was randomly assigned 1 of 14 different combinations of nationality, partisanship and education. The entire game was played twice, meaning that each respondent received two vignettes. In the second round, it was assured that respondents played the game against an opponent with a different combination of characteristics. Contrary to rationality expectations and despite the fact that they play with a relatively small amount of money, behavioural economists have shown that survey participants allocate non-trivial amounts, depending on the characteristics of the respondents and those of their fictitious partners (Fershtman and Gneezy Citation2001; Wilson and Eckel Citation2011).

To test our arguments, we calculated the average positions in the first (attitudinal) experiment by means of OLS regression analyses. We ran linear regressions for each treatment combination, separately including only a dependent variable but no predictors. We then plotted the constant (i.e. the mean of each treatment group) with 95% confidence intervals (see Jann Citation2014). As participants provided answers to two vignettes in the second (behavioural) experiment, we constructed a stacked data file that includes two cases for each respondent. For this reason, we ran multilevel analyses to predict the amount of money someone gives to the other player by taking into account the nested structure of the data (participants are the upper level and the vignettes the lower level). Again, we ran separate models for each treatment group that contained only the dependent variable and plotted the mean of each treatment group with 95% confidence intervals. The detailed regression analyses can be found in the Online appendix (Tables A5–A8). All scales were recoded so that higher values indicate more positive attitudes.

Analyses

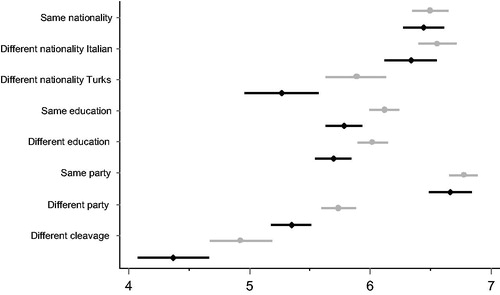

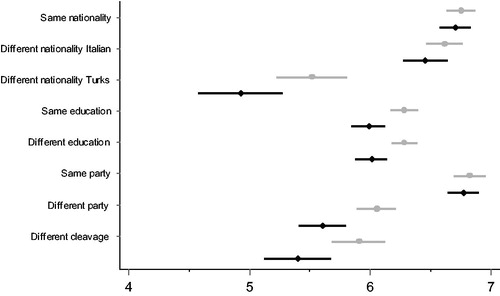

In the first step of our analyses in and , we have tried to discover how people position themselves towards others who have either the same or a different nationality, education or party identity (see also Online appendix, Tables A5a and A5b).5 We look at the national out-groups, Italians and Turks, which represent culturally more close and distant immigration groups and are considered better and rather poorly integrated in Germany. Regarding partisan out-groups, we look at people’s attitudes towards members of a different party or members of a party at the other cleavage side. This last differentiation pits AfD voters against all other voters and vice versa. For each category, we show separately whether people see it as a problem if these other people moved into their neighbourhood (grey) or if a close family member married someone from these groups (black). For the sake of clarity, we do not display the results for the two items work and friendship. More detailed analyses have shown that in most instances the items neighbourhood and marriage constitute the two extreme values, as would be expected by social distance theory.

Figure 1. Attitudes towards in- and out-groups in Germany.

Note: Average scores on a scale from 1 (negative) to 7 (positive) and 95% confidence intervals are reported. The results are based on the regression models documented in Online appendix Table A5a. Grey dots indicate neighbourhood, black dots marriage. ‘Different cleavage’ indicates attitudes between AfD and all other voters.

Figure 2. Attitudes towards in- and out-groups in Austria.

Note: Average scores on a scale from 1 (negative) to 7 (positive) and 95% confidence intervals are reported. The results are based on the regression models documented in Online appendix Table A5b. Gray dots indicate neighbourhood, black dots marriage. ‘Different cleavage’ indicates attitudes between FPÖ and all other voters.

We found confirmation for our hypothesis 1, according to which in-groups are seen more positively than out-groups.6 This finding, however, depends very much on how the in- and out-groups are defined. National and partisan in-groups are seen more positively than educational in-groups. There is hardly any difference in attitudes if the out-group is a culturally relatively close and well-integrated group, like the Italians, or if they have a different level of education. For reference, the average sympathy ranges from 6.45 (Germany: marriage, CI: 6.29; 6.61) to 6.76 (Austria: neighbourhood, CI: 6.64; 6.88) on a scale from 1 to 7 for the national in-group in both countries and almost the same for Italians (Germany: marriage, 6.34 [CI: 6.12; 6.56] to Austria: neighbourhood, 6.62 [CI: 6.46; 6.76]). Out-groups are strongly resented, however, if they are a culturally distant immigrant group, like the Turks, and if they identify with a different party, especially if this party belongs to the other side of the integration-demarcation cleavage. For instance, people’s approval of someone close marrying a person with Turkish background drops by around one point in Germany (to 5.26, CI: 4.97; 5.55) and by almost two points in Austria (to 4.93, CI: 4.58; 5.28) compared to that person marrying a native or Italian. And quite similarly, people affiliated with a party from the other side of the cleavage are rated about one point lower in Austria (5.40, CI: 5.13; 5.67) and about two points lower in Germany (4.37, CI: 4.08; 4.66) as compared to people with the same nationality (i.e. the reference group).

The pattern regarding attitudes towards partisan out-groups confirms our hypothesis 2. Winners and losers of globalisation express particularly strong negative attitudes towards each other in Germany. These tensions are even bigger than those towards immigrants, especially if one compares them with attitudes towards Italian immigrants. But we see increased resentment even in comparison with attitudes towards Turkish immigrants.7 Attitudes towards partisan in-groups (6.67, CI: 6.49; 6.85) are even slightly more positive than towards the national in-group (6.45, CI: 6.29; 6.61), and there are clearly more negative attitudes towards cleavage out-groups (4.37, CI: 4.08; 4.66) than towards Turkish immigrants (5.26, CI: 4.97; 5.55). In Austria, the pattern is similar but less polarising for partisans. Here, fellow partisans (6.77, CI: 6.65; 6.89) are again rated in more sympathetic terms than the national in-group (6.71, CI: 6.59; 6.83), but those from the other side of the cleavage (5.40, CI: 5.13; 5.67) are not rated lower than Turkish immigrants (4.93, CI: 4.58; 5.28). Concerning educational out-groups, our hypotheses 1 and 2 are only partly confirmed. We see that attitudes are more negative towards educational out-groups (AT: 6.01 [CI: 5.89; 6.13], DE: 5.69 [CI: 5.53; 5.85]) than towards Italian immigrants (AT: 6.46 [CI: 6.28; 6.64], DE: 6.34 [CI: 6.12; 6.56]) but similar and partly more positive in comparison to attitudes towards Turkish immigrants (AT: 4.93 [CI: 4.58; 5.28], DE: 5.26 [CI: 4.97; 5.55]). People, however, make no difference between educational in- and out-groups.

We also see the social distance argument confirmed, with average sympathy across treatment groups being about 0.3 to 0.6 points lower when considering a person supposed to marry someone close to oneself as compared to someone moving into the respondent’s neighbourhood. Especially for highly resented groups like Turkish immigrants and partisan out-groups, we see that attitudes get even more negative when people are asked how they would react if close family members married someone from these groups (AT: 5.52 [CI: 5.23; 5.81] to 4.93 [CI: 4.58; 5.28], DE: 5.89 [CI: 5.64; 6.14] to 5.26 [CI: 4.97; 5.55]). As expected, social distance does not play any role for national or partisan in-groups. It is rather surprising, however, that such a difference exists for educational in-groups.

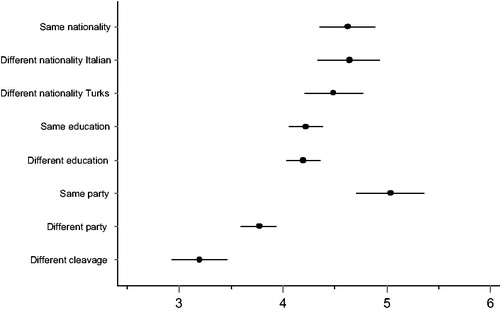

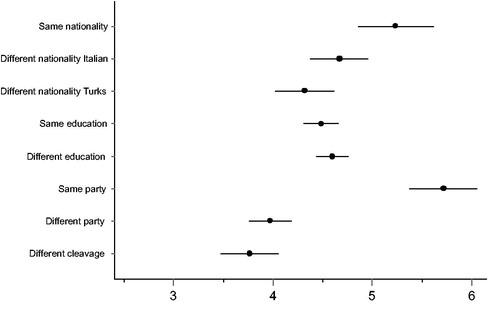

and shows the results of our behavioural trust games and allows us to see whether or not the behaviour towards opposing cleavage groups corresponds to the attitudes we observed in and . The scale goes from 0 (less generous) to 10 (more generous behaviour). In and , we display the average values across both rounds (see also Online appendix, Tables A6a and A6b). Overall, the behavioural games led to the same results as the attitudinal vignette study. The differences are not as pronounced, however. Although the social distance hypothesis cannot be tested here, we see with respect to partisan and cleavage in- and out-groups that they lead to the strongest polarisation. Again, the effect in Austria is somewhat weaker. Moreover, we find again that people make no differentiation between educational in- and out-groups. Contrary to and , we see that more negative attitudes towards Turks (compared to Germans/Austrians or Italians) do not translate into actual discriminatory behaviour. This can also be seen as confirmation of our hypothesis 2, namely that social desirability bias plays a role for ethnic but not partisan groups. When different partisans are addressed, people do not suppress their attitudes to keep a favourable public image. Rather, they clearly discriminate against those supporting opposing parties.

Figure 3. Behaviour towards in- and out-groups in Germany.

Note: Average scores on a scale from 0 to 10 euros and 95% confidence intervals are reported. The results are based on the regression models documented in Online appendix Table A6a. ‘Different cleavage’ indicates attitudes between AfD and all other voters.

Figure 4. Behaviour towards in- and out-groups in Austria.

Note: Average scores on a scale from 0 to 10 euros and 95% confidence intervals are reported. The results are based on the regression models documented in Online appendix Table A6b. ‘Different cleavage’ indicates attitudes between FPÖ and all other voters.

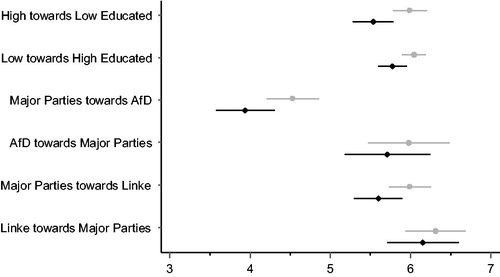

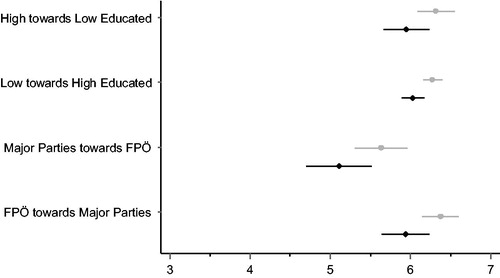

Having compared attitudes towards in- and out-groups across different categories, we now try to discover how symmetrical these opposing attitudes are. Could it be that one side of the cleavage resents the other more strongly than the other way round, or are these attitudes completely reciprocal? In , we differentiate between attitudes among highly and less-educated people, as well as between AfD, Linke, and majority party (CDU, SPD) partisans, towards the respective out-groups (see also Online appendix, Table A7a). For each category, we again show separately whether people see it as a problem if these other persons moved into their neighbourhood (grey) or if a close family member married someone from these groups (black). Given that the sample only includes natives, we do not investigate asymmetrical relationships between natives and immigrants.

Figure 5. Asymmetrical relationships (attitudes) in Germany.

Note: Average scores on a scale from 1 (negative) to 7 (positive) and 95% confidence intervals are reported. The results are based on the regression models documented in Online appendix Table A7a. Gray dots indicate neighbourhood, black dots indicate marriage.

Concerning education, we see no difference for the neighbourhood question. In Germany, the average level of sympathy of the higher educated with the lower educated and vice versa is about 6 points. In Austria, the pattern is pretty much the same, with about 0.3 higher overall agreement. We see, however, that more highly educated people have a bigger problem with family members marrying a lower educated person than vice versa. We see a similar relationship between voters of the Left and voters of majority parties. Whereas answers for the neighbourhood question are very similar, majority party voters clearly have a bigger problem if close family members marry a voter of the Left than vice versa (5.60 [CI: 5.31; 5.89] vs. 6.16 [CI: 5.73; 6.59]). An extremely asymmetrical relationship can be observed between AfD and majority party identifiers. Whereas AfD positions are similar to those between educational groups, attitudes of majority party identifiers towards AfD partisans are by far the most negative of all the different relationships we investigate (3.94 [CI: 3.57; 4.31] vs. 5.71 [CI: 5.18; 6.24]).8 We find similar asymmetrical effects for Austria, even though the absolute degree of polarisation is slightly weaker (5.11 [CI: 4.70; 5.52] vs. 5.94 [CI: 5.65; 6.23], see and Online appendix, Table A7b). Finally, we found more or less similar but weaker effects in the behaviour experiment (see Figures A1a and A1b and Tables A8a and A8b in the Online appendix).

Figure 6. Asymmetrical relationships (attitudes) in Austria.

Note: Average scores on a scale from 1 (negative) to 7 (positive) and 95% confidence intervals are reported. The results are based on the regression models documented in Online appendix Table A7b. Gray dots indicate neighbourhood, black dots indicate marriage.

Overall, these findings confirm hypothesis 3b and disconfirm hypothesis 3a, especially for party voters but partly also for education: losers of globalisation are less opposed to the winners than vice versa. Highly educated people and the voters of majority parties are more opposed to less-educated people and minority party voters than the other way round. We also see the social distance argument reconfirmed: attitudes towards the marriage question are more negative than attitudes towards the neighbourhood question; this is particularly true for better educated and majority party voters.

Conclusion

This article set out to investigate the extent to which the new integration-demarcation cleavage is socially embedded in the everyday life of ordinary citizens. Although we already know a lot about the socio-economic basis of the new cleavage and how it has been politically articulated, we do not know to what extent it pits winners and losers of globalisation against each other and thus constitutes not only a political but also a social divide. Our study revealed the existence of a salient partisan in-group bias, showing that people prefer having people in their neighbourhood and in their family, who identify with the same party, and that they oppose especially those who identify with a party from the other side of the cleavage. This in-group bias is as strong, if not stronger, than the ethnic in-group favouritism that we took as a reference category. We did not find any in-group favouritism, however, when it comes to education, which is a crucial socio-economic characteristic of losers and winners of globalisation. Potentially, future studies could investigate this further in terms of different perceptions of each group’s habitus (Bourdieu Citation1990). Educational characteristics should thus not be varied in terms of objective levels of education, but rather as different cultural manifestations on the basis of certain lifestyles, language, attire or taste.

Winners and losers of globalisation do not only vote for different parties that support or oppose denationalisation processes, they also try to avoid each other in daily life. It seems that the hostile political rhetoric of opposing parties left its imprint on ordinary citizens. It could be argued (and tested in future studies) that prejudice against people from the other side of the political cleavage is considered an acceptable attitude, unlike prejudice against immigrants, which is inhibited by social and legal norms, as argued by Iyengar and Westwood (Citation2015: 690) and Kuppens et al. (Citation2018: 431).

Such an effect might also explain why, in the trust games, people’s behaviour towards players from other parties is clearly more negative than it is towards immigrants. The absence of social norms might also explain the asymmetrical divide, because the winners of globalisation (who are often more tolerant towards others who are considered out-groups by some, such as immigrants or ethnic minorities) more strongly oppose the losers of globalisation (who are often more prejudiced against these out-groups) than vice versa. This is especially true for party voters but partly also for people with different levels of education. We argued that it seems plausible that winners of globalisation perceive the opponents of globalisation as a threat to their own cultural and economic privileges and therefore prefer to maintain group-based hierarchy and in-group hegemony.

The fact that we observed the same patterns in a country where the new integration-demarcation cleavage and a major right-wing populist party emerged some time ago (Austria) and in a country where the cleavage and a right-wing populist party are much more recent phenomena (Germany), allows us to make certain generalisations. Investigating only two cases for a single period of time is an important limitation, however. Data across time would be necessary to understand better how the emergence of the cleavage affects the evolution of social divides. Investigating contextual effects might help us better understand how the political divide is translated into a social divide. Given the differences we observed in Austria and Germany, it seems plausible that polarisation between partisans begins to weaken once a newly established party becomes more familiar. In other words, the stronger level of polarisation in Germany could be explained by a positive bias to stigmatise AfD sympathisers in Germany. However, polarisation does not disappear, even in a country that has known one of the longest right-wing populist traditions in Europe.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (90.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank David Art, Bart Bonikowski, Simon Bornschier, Bruno Castanho Silva, Heike Klüver, Rahsaan Maxwell, Andres Reiljan, Oliver Strijbis, Denise Traber and Markus Wagner as well as two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marc Helbling

Marc Helbling is Full Professor in Political Sociology at the University of Bamberg and a Research Fellow at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center. He works on immigration and citizenship policies, nationalism, national identities, xenophobia/islamophobia, and right-wing populism. His work has appeared, among others, in British Journal of Political Science, Comparative Political Studies, European Sociological Review and Social Forces. [[email protected]]

Sebastian Jungkunz

Sebastian Jungkunz is Research Associate and Lecturer at the University of Bamberg and Zeppelin University. His research interests include populism, political extremism and polarisation of public opinion. He has published in Ethnicities, Political Research Exchange, and Political Research Quarterly, amongst others. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 The sample includes German and Austrian nationals above the age of 18 who were sampled according to their gender, age and education. Respondi maintains an ISO-certified Online Access Panel with around 100,000 potential respondents per country. For more information on the respondi access panel, see https://www.respondi.com/. To control for speed and slowness, we excluded the fastest and slowest three percent of respondents from the dataset. This did not change our results in any way though. We also checked whether the removal of the small number of respondents with a migration background would alter our results. This was not the case in any of the models reported.

2 It goes without saying that political parties also represent other social groups, not just winners and losers of globalization, especially given the fact that the political sphere also consists of other cleavages. Nonetheless, as we show below, the parties included in this study represent the main political forces on the two sides of the cleavage in the two countries under study.

3 For pragmatic reasons, and in order to have sufficiently large respondent groups per treatment, we did not include other parties that might also have been interesting in this context, such as the Greens or the pro-market Free Democrats (FDP).

4 The players only used virtual money and were not rewarded with the actual sum.

5 As Die Linke has traditionally been a political party from East Germany and the AfD has been slightly more successful in East than in West Germany, we also analyzed our data separately for both regions. It appeared that the patterns we observe in our data are the same in West Germany. The overall patterns are also very similar in East Germany, with a few exceptions that are reported in the following sections.

6 In general, we see that attitudes towards out-groups are also rather positive if one takes into account the full scale. As we cannot compare these findings with other studies, it is difficult to interpret the absolute levels. This is one of the reasons why we are mostly interested in the relative differences and compare attitudes towards different kinds of in- and out-groups.

7 In East Germany, attitudes towards Turks are more negative than in West Germany. The attitudinal gap between partisan in- and outgroups is therefore similar to the gap between national in- and outgroups.

8 This finding is mainly driven by voters in West Germany. Majority party voters in East Germany have more positive attitudes towards AfD voters than majority party voters in West Germany.

References

- Ansolabehere, S., and B. F. Schaffner (2014). ‘Does Survey Mode Still Matter? Findings from a 2010 Multi-Mode Comparison’, Political Analysis, 22:3, 285–303.

- Arzheimer, K. (2009). ‘Contextual Factors and the Extreme Right Vote in Western Europe, 1980-2002’, American Journal of Political Science, 53:2, 259–75.

- Azmanova, A. (2011). ‘After the Left-Right (Dis)Continuum: Globalization and the Remaking of Europe’s Ideological Geography’, International Political Sociology, 5:4, 384–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-5687.2011.00141.x.

- Bartolini, S. (2005). Restructuring Europe: Centre Formation, System Building, and Political Structuring between the Nation State and the European Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bartolini, S., and P. Mair (1990). Identity, Competition, and Electoral Availability: The Stabilisation of European Electorates 1885-1985. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Baumeister, R. F., E. Bratslavsky, C. Finkenauer, and K. D. Vohs (2001). ‘Bad Is Stronger than Good’, Review of General Psychology, 5:4, 323–70.

- Bogardus, E. (1925). ‘Social Distance and Its Origins’, Journal of Applied Sociology, 9:3, 216–26.

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press (Original work published 1979).

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). The Logic of Practice. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Bovens, M., and A. Wille (2017). Diploma Democracy: The Rise of Political Meritocracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brandt, M. J., C. Reyna, J. R. Chambers, J. T. Crawford, T. and G. Wetherell (2014). ‘The Ideological-Conflict Hypothesis: Intolerance among Both Liberals and Conservatives’, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23:1, 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721413510932.

- Bremer, B., and J. Schulte-Cloos (2019). ‘The Restructuring of British and German Party Politics in Times of Crisis’, in S. Hutter and H. Kriesi (eds.), European Party Politics in Times of Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 281–301.

- Brewer, M. (2001). ‘The Many Faces of Social Identity: Implications for Political Psychology’, Political Psychology, 22:1, 115–25.

- Cacioppo, J. T., and G. G. Berntson (1994). ‘Relationship between Attitudes and Evaluative Space: A Critical Review, with Emphasis on the Separability of Positive and Negative Substrates’, Psychological Bulletin, 115:3, 401–23.

- Chambers, J. R., B. R. Schlenker, and B. Collisson (2013). ‘Ideology and Prejudice: The Role of Value Conflicts’, Psychological Science, 24:2, 140–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612447820.

- Crawford, J. T., M. J. Brandt, Y. Inbar, J. R. Chambers, and M. Motyl (2017). ‘Social and Economic Ideologies Differentially Predict Prejudice across the Political Spectrum, but Social Issues Are Most Divisive’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112:3, 383–412. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000074.

- Crocker, J., B. Major, and C. Steele (1998). ‘Social Stigma’, in D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, and G. Lindzey (eds.), Handbook of Social Psychology. Vol. 2, 4th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 504–53.

- Dambrun, M., S. Guimond, and D. M. Taylor (2006). ‘The Counter-Intuitive Effect of Relative Gratification on Intergroup Attitudes: Ecological Validity, Moderators and Mediators’, in S. Guimond (ed.), Social Comparison and Social Psychology: Understanding Cognition, Intergroup Relations, and Culture. New York: Cambridge University Press, 206–27.

- Dolezal, M. (2008a). ‘Austria: Transformation Driven by an Established Party’, in H. Kriesi, E. Grande, R. Lachat, M. Dolezal, S. Bornschier, and T. Frey (eds.), West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 105–29.

- Dolezal, M. (2008b). ‘Germany: The Dog That Didn’t Bark’, in H. Kriesi, E. Grande, R. Lachat, M. Dolezal, S. Bornschier, and T. Frey (eds.), West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 208–33.

- Dolezal, M., and S. Hutter (2012). ‘Participation and Party Choice: Comparing the Demand Side of the New Cleavage across Arenas’, in H. Kriesi, E. Grande, M. Helbling, D. Hoeglinger, S. Hutter, and B. Wüest (eds.), Political Conflict in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 67–95.

- Fershtman, C., and U. Gneezy (2001). ‘Discrimination in a Segmented Society’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116:1, 351–77.

- Flanagan, S. C., and A.-R. Lee (2003). ‘The New Politics, Culture Wars, and the Authoritarian-Libertarian Value Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies’, Comparative Political Studies, 36:3, 235–70.

- Franklin, M. T., Mackie, T. T., and Valen, H. (eds.) (1992). Electoral Change: Responses to Evolving Social and Attitudinal Structures in Western Countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Guimond, S., and M. Dambrun (2002). ‘When Prosperity Breeds Intergroup Hostility: The Effects of Relative Deprivation and Relative Gratification on Prejudice’, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28:7, 900–12.

- Hagendoorn, L., and S. Nekuee (eds.) (1999). Education and Racism: A Cross-National Inventory of Positive Effects of Education on Ethnic Tolerance. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Hainmueller, J., and D. J. Hopkins (2014). ‘Public Attitudes toward Immigration’, Annual Review of Political Science, 17:1, 225–49.

- Halperin, E., A. Pedahzur, and D. Canetti-Nisim (2007). ‘Psychoeconomic Approaches to the Study of Hostile Attitudes toward Minority Groups: A Study among Israeli Jews’, Social Science Quarterly, 88:1, 177–98.

- Hello, E., P. Scheepers, and P. Sleegers (2006). ‘Why the More Educated Are Less Inclined to Keep Ethnic Distance: An Empirical Test of Four Explanations’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 29:5, 959–85.

- Heyder, A. (2003). ‘Bessere Bildung, bessere Menschen? Genaueres Hinsehen hilft weiter’, in W. Heitmeyer (ed.), Deutsche Zustände (Folge 2). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 78–99.

- Hobolt, S. B. (2016). ‘The Brexit Vote: A Divided Nation, a Divided Continent’, Journal of European Public Policy, 23:9, 1259–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1225785.

- Iyengar, S., and S. J. Westwood (2015). ‘Fear and Loathing across Party Lines: New Evidence on Group Polarization’, American Journal of Political Science, 59:3, 690–707.

- Jackman, M. R., and M. Crane (1986). ‘“Some of My Best Friends Are Black…”: Interracial Friendship and Whites’ Racial Attitudes’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 50:4, 459–86.

- Jackman, M. R., and M. J. Muha (1984). ‘Education and Intergroup Attitudes: Moral Enlightenment, Superficial Democratic Commitment, or Ideological Refinement? ’, American Sociological Review, 49:6, 751–69.

- Jann, B. (2014). ‘Plotting Regression Coefficients and Other Estimates’, The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 14:4, 708–37.

- Jost, J. T., and M. R. Banaji (1994). ‘The Role of Stereotyping in System-Justification and the Production of False Consciousness’, British Journal of Social Psychology, 33:1, 1–27.

- Kawakami, K., and K. L. Dion (1995). ‘Social Identity and Affect as Determinants of Collective Action: Toward an Integration of Relative Deprivation and Social Identity Theories’, Theory & Psychology, 5:4, 551–77.

- Kriesi, H. (2012). ‘Restructuring the National Political Space: The Supply Side of National Electoral Politics’, in H. Kriesi, E. Grande, M. Helbling, D. Hoeglinger, S. Hutter, and B. Wüest (eds.), Political Conflict in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 96–126.

- Kriesi, H., E. Grande, M. Helbling, D. Hoeglinger, S. Hutter, and B. Wüest (eds.) (2012). Political Conflict in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, H., E. Grande, R. Lachat, M. Dolezal, S. Bornschier, and T. Frey (eds.) (2008). West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kuppens, T., R. Spears, A. S. R. Manstead, B. Spruyt, and M. J. Easterbrook (2018). ‘Educationism and the Irony of Meritocracy: Negative Attitudes of Higher Educated People towards the Less Educated’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, 429–47.

- LeBlanc, J., A. M. Beaton, and I. Walker (2015). ‘The Downside of Being up: A New Look at Group Relative Gratification and Traditional Prejudice’, Social Justice Research, 28:1, 143–67.

- Levendusky, M. S. (2018). ‘Americans, Not Partisans: Can Priming American National Identity Reduce Affective Polarization?’, The Journal of Politics, 80:1, 59–70.

- Lipset, S. M., and S. Rokkan (eds.) (1967). Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York: Free Press.

- Mason, L. (2015). ‘“I Disrespectfully Agree”: The Differential Effects of Partisan Sorting on Social and Issue Polarization’, American Journal of Political Science, 59:1, 128–45.

- Mason, L. (2018). ‘Ideologues without Issues: The Polarizing Consequences of Ideological Identities’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 82:S1, 301–866.

- McIntosh, P. (2012). ‘Reflections and Future Directions for Privilege Studies’, Journal of Social Issues, 68:1, 194–206.

- Medeiros, M., and A. Noël (2014). ‘The Forgotten Side of Partisanship: Negative Party Identification in Four Anglo-American Democracies’, Comparative Political Studies, 47:7, 1022–46.

- Mudde, C. (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mullen, B., R. Brown, and C. Smith (1992). ‘Ingroup Bias as a Function of Salience, Relevance, and Status: An Integration’, European Journal of Social Psychology, 22:2, 103–22.

- Postmes, T., and L. G. E. Smith (2009). ‘Why Do the Privileged Resort to Oppression? A Look at Some Intragroup Factors’, Journal of Social Issues, 65:4, 769–90.

- Rogowski, J. C., and J. L. Sutherland (2016). ‘How Ideology Fuels Affective Polarization’, Political Behavior, 38:2, 485–508.

- Rooduijn, M. (2015). ‘The Rise of the Populist Radical Right in Western Europe’, European View, 14:1, 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12290-015-0347-5.

- Sidanius, J., and F. Pratto (1999). Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Spruyt, B. (2014). ‘An Asymmetric Group Relation? An Investigation into Public Perceptions of Education-Based Groups and the Support for Populism’, Acta Politica, 49:2, 123–43.

- Steenvoorden, E., and E. Harteveld (2018). ‘The Appeal of Nostalgia: The Influence of Societal Pessimism on Support for Populist Radical Right Parties’, West European Politics, 41:1, 28–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1334138.

- Stubager, R. (2009). ‘Education-Based Group Identity and Consciousness in the Authoritarian-Libertarian Value Conflict’, European Journal of Political Research, 48:2, 204–33.

- Stubager, R. (2010). ‘The Development of the Education Cleavage: Denmark as a Critical Case’, West European Politics, 33:3, 505–33.

- Tajfel, H. (1970). ‘Experiments in Intergroup Discrimination’, Scientific American, 223:5, 96–103.

- Tajfel, H., and J. C. Turner (1979). ‘An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict’, in W. G. Austin and S. Worchel (eds.), The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Teney, C., O. P. Lacewell, and P. de Wilde (2014). ‘Winners and Losers of Globalization in Europe: Attitudes and Ideologies’, European Political Science Review, 6:4, 575–95. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773913000246.

- Vogt, P. W. (1997). Tolerance and Education: Learning to Live with Diversity and Difference. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Wagner, U., and A. Zick (1995). ‘The Relation of Formal Education to Ethnic Prejudice: Its Reliability, Validity and Explanation’, European Journal of Social Psychology, 25:1, 41–56.

- Webster, S. W., and A. I. Abramowitz (2017). ‘The Ideological Foundations of Affective Polarization in the U.S. Electorate’, American Politics Research, 45:4, 621–47.

- Westwood, S. J., S. Iyengar, S. Walgrave, R. Leonisio, L. Miller, and O. Strijbis (2018). ‘The Tie That Divides: Cross-National Evidence of the Primacy of Partyism’, European Journal of Political Research, 57:2, 333–54.

- Wilson, R. K., and C. C. Eckel (2011). ‘Trust and Social Exchange’, in J. S. Druckman, D. P. Green, J. H. Kuklinski, and A. Lupia (eds.), Cambridge Handbook of Experimental Political Science. New York: Cambridge University Press, 243–57.

- Yeager, D. S., J. A. Krosnick, L. Chang, H. S. Javitz, M. S. Levendusky, A. Simpser, and R. Wang (2011). ‘Comparing the Accuracy of RDD Telephone Surveys and Internet Surveys Conducted with Probability and Non-Probability Samples’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 75:4, 709–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfr020

- Zhong, C.‑B., K. W. Phillips, G. J. Leonardelli, and A. D. Galinsky (2008). ‘Negational Categorization and Intergroup Behavior’, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34:6, 793–806.