?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Collaborative leadership has stood at the heart of European politics since its inception. Yet EU scholars have only recently started to examine the concept and mainly from an institutional perspective. This article conceptualises the phenomenon of collaborative leadership from an actor-centered perspective. It explores a central condition for successful collaborative leadership identified in the literature: the existence of shared beliefs among the leaders involved. To do this, the article focuses on four events in the history of European Economic and Monetary Union. Using the method of cognitive mapping, the study establishes the extent of congruence in the beliefs on European integration and fiscal and monetary policy of the four leadership trios overseeing these events. On the basis of a survey of leading experts in the field, the article reveals that the level of cognitive proximity in leaders’ beliefs aligns with the perceived success with which the trios exerted collaborative leadership.

In the European Union several interdependent actors at the supranational and intergovernmental level share power and collaborate to govern and lead the EU together (Cramme Citation2011; Tömmel Citation2014). As such, the European Union can best be understood as a leaderful environment (Müller and Van Esch Citation2019). Although scholars agree that no single centre of leadership exists in the EU, the topic of collaborative leadership has only recently gained traction in European studies (Nielsen and Smeets Citation2018; Smeets and Beach Citation2019).

Contributing to this emerging field, the article pursues three aims: First, it seeks to draw lessons from the leadership literature about the nature and conditions of collaborative leadership at the European level from an agency perspective, thereby focussing on individual leaders rather than collective actors (EU institutions). Second, it provides an in-depth study of the similarities and differences in the belief systems of the EU leadership trios – comprised of the French president, the German chancellor and the EU Commission president – overseeing four key events in the history of European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). Third, as the leadership literature identifies a meeting of minds among key leaders as one of the central aspects for successful collaboration, this article provides a first empirical exploration of the relation between cognitive proximity and EU collaborative leadership.

In particular, the paper studies the cognitive proximity and collaborative leadership of the following trios: (1) François Mitterrand, Helmut Kohl and Jacques Delors; (2) Jacques Chirac, Gerhard Schröder and Romano Prodi; (3) Nicolas Sarkozy, Angela Merkel and José Manuel Barroso; and, finally, (4) François Hollande, Angela Merkel and Jean-Claude Juncker. The article will establish these leaders’ ideas regarding the finalité of European integration as well as fiscal and monetary policy making, using the method of cognitive mapping (CM). Developed in political psychology, this method allows for in-depth qualitative and quantitative comparison of (espoused) policy beliefs as well as their level of convergence between individuals. Complemented by a survey of EU experts on the perceived collaborative success of each European trio, the article subsequently explores the link between the level of belief similarity and the likelihood of successful collaborative leadership in the European Union.

Collaborative leadership and European integration

Traditionally, the domain of leadership studies has focussed on the role of powerful individuals in the political arena. While in the majority of political systems, collective decision making, shared responsibility and political collaboration are the norm rather than the exception, most research into shared and collaborative leadership, political teamwork or leader-leader interactions is of recent vintage (Avolio et al. Citation2009: 43; Fletcher and Käufer Citation2003: 22).

Collaborative governance is defined as an iterative and cyclical process between two or more public and/or private stakeholders that engage in consensus-driven decision making on the basis of joint responsibility, authority and accountability to achieve mutually desired goals (Ansell and Gash Citation2007). It comes into play when the leading stakeholders acknowledge that unilateral agency is ineffective (Chrislip and Larson Citation1994). In this sense, collaboration can be distinguished from other forms of interaction and collective decision making like cooperation and coordination. Whereas the latter involve partners helping each other to achieve their own goals, collaborative governance concerns situations in which partners are equally involved in all ‘joint activities, joint structures and shared resources’, thus pursuing shared goals (Walter and Petr Citation2000: 495). Applying James MacGregor Burns’ distinction of transactional and transformational leadership to the relationship of interacting leaders, the modes of coordination and cooperation can best be described as transactional, implying an exchange of valued (material or non-material) commodities. In contrast, the mode of collaboration may best be understood as transformational, with ‘leaders … rais[ing] one another to higher levels of motivation and morality’ (Burns Citation2010 [1978]: 83; see also Müller and Van Esch Citation2019).

While collaborative governance is easy to conceive in the abstract, its actual realisation is hard, and ‘this is where “leadership” comes in’ (Archer and Cameron Citation2013: 12). Collaborative leadership aims at transcending organisational and procedural boundaries in order to create constructive processes that enable the appropriate stakeholders to meet, facilitate and maintain their interaction (Chrislip and Larson Citation1994; ‘t Hart Citation2014). While collaborative leadership always involves multiple (formal or informal) leaders instead of a single one, its essence is to jointly create a shared vision and joint strategy of all actors involved (Chrislip and Larson Citation1994; Fletcher and Käufer Citation2003).

Since its foundation, the European Union has been based on collaboration among national and supranational leaders as well as national and European institutions, constituting a core condition for both the EU’s major political integration steps as well as its day-to-day running (Van Esch Citation2017). Oddly, however, collaborative leadership has received little attention in theories of European integration. From neo-functionalism and supranationalism to liberal and new intergovernmentalism, European integration theories differ widely in their assessments of the role of intergovernmental or supranational actors in EU politics, often concluding that the decisive authority lies more with either the supranational institutions like the European Commission (Haas Citation1958; Sandholtz and Zysman Citation1989) or the member states and the intergovernmental Council of Ministers and European Council (Fabbrini and Puetter Citation2016; Moravcsik Citation1999). However, legally as well as in practice, the EU’s political system presupposes collaboration across the EU’s institutions and their protagonists. Research on the creation of the EU banking union, for example, confirms that interinstitutional collaboration is a central feature of EU policy making (Nielsen and Smeets Citation2018).

The same is true at the level of individual leaders. The actors that are typically seen to personify the polycentric and interactive leadership in the European Union are the French president, the German chancellor and the president of the European Commission (Dinan Citation2011; Verdun Citation1999: 310). The close French-German relationship is widely acknowledged as a significant political, economic and societal force in the EU. Many scholars have argued that the relations and friendships between the top German and French leaders – fostered by a shared perception of mutual interest and dependence – are an essential part of this (Van Esch Citation2009).

At the same time, this tandem needs supranational support by the European Commission – ‘the congenial partner’ – and its president to actually make the EU machine run (Germond Citation2013: 11). The permanent president of the European Council also provides co-leadership and mediates among member states but only since 2009. Moreover, it is the European Commission that for decades has had the administrative and procedural resources to initiate and monitor EU policies, and that embodies the union’s common interest without which the ongoing process of European integration would not work (Endo Citation1999; Müller Citation2016, Citation2017).

However, collaborative leadership does not arise automatically or even easily. A review of the literature indicates that an important condition for its establishment is that the individual leaders share core beliefs and values regarding their common pursuit, as these are ‘the glue that hold … collaborative efforts together’ (Walter and Petr Citation2000: 495–96; cf. Van Esch Citation2009). Moreover, such cognitive proximity is important because ‘individuals tend to filter new information through their pre-existing beliefs’ (Renshon Citation2008: 822, 824; cf. Haas Citation1992: 28; Van Esch and de Jong Citation2019). Despite differences in the German and French approaches to economic and monetary integration, Dyson, for example, argues that the French-German relationship fundamentally rests on a shared belief in its value as the ‘motor’ of Europe (Dyson Citation1999; see also Van Esch Citation2007; Young Citation2012). Finally, scholars working on the theme of epistemic communities argue that collaborating actors are in need of ‘a shared set of normative and principled beliefs, which provide a value-based rationale for the social action of community members’ (Haas Citation1992: 3, 22; see also Verdun Citation1999: 320). Of course, this does not mean that challenges are absent among like-minded people, but kindred spirits may draw upon shared understandings and values, allowing each other the benefit of the doubt when misperceptions or other difficulties arise (Bligh Citation2017). Theoretically, it may therefore be expected that the more similar the core beliefs among stakeholders are, the more successful they will be in exerting collaborative EU leadership.

This thesis diverges from that put forward in the domain of (EU) negotiation theory, in which scholars argue that EU decision making is most effective when states have opposite, yet reconcilable interests. Following a transactional quid pro quo reasoning, these scholars reason that due to the difference in their positions, the views of the German chancellor and French president may actually represent the interests and beliefs of a wider subset of EU member states. This allows them to factually act as the spokespeople of a wider set of states, thereby facilitating compromise among a larger group of member states (Schild Citation2010; Schoeller Citation2018; Webber Citation1999). Although this branch of thought departs from a different, transactional perspective and focusses on cooperation rather than collaboration, it does raise the question of whether belief proximity is indeed necessary for successful collaborative leadership to emerge. As collaboration has been a core and vital feature of European governance since the EU’s inception, understanding under what conditions collaborative leadership arises and may be successful is an important question.

Research design

The article’s empirical analysis will focus on the domain of European economic and monetary integration. This choice was made because collaboration in this domain has a long history and includes a variety of collaborative efforts to compare. Choosing four cases from within the same domain also facilitates the comparison of beliefs and belief proximity between the cases. To establish the level of similarity among the leaders’ belief systems, the method of cognitive mapping (CM) is used. This method is specifically designed to study the content of policy beliefs and allows for the structural qualitative and quantitative comparison of leaders’ belief systems (Van Esch Citation2007; Young and Schafer Citation1998). Like most ‘at a distance’ studies of leaders, cognitive maps are derived from leaders’ public assertions in speeches, writings and interviews (Axelrod Citation1976: 6–7; Marfleet Citation2000; Renshon Citation2009; Van Esch Citation2007). In this study, the maps are composed on the basis of a selection of the French, German and Commission leaders’ public speeches concerning European economic and monetary issues held prior to a historic EMU event.

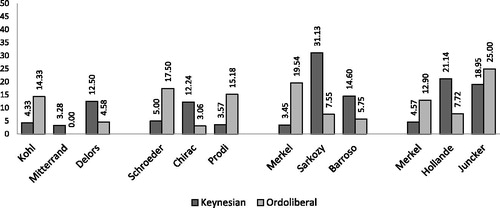

One cognitive map per leader is constructed to ascertain their individual beliefs as well as the congruence in the beliefs among the members of each trio. To increase construct-validity, the maps are based on public speeches directed at various audiences over a given period of time (). Only the sections of speeches that explicitly dealt with European economic and monetary policy making were selected for analysis. From these, all causal and normative relationships were hand coded.1 To avoid concept overlap and facilitate comparison across time and between different leaders, the concepts were standardised. Subsequently, the relationships were transformed into a graphic map displaying the coded relations as arrows between two concepts. These maps were analysed using the software application Gephi (Bastian et al. Citation2009). The weight of the relations and saliency of concepts in CM were determined by ascertaining the frequency with which relations are mentioned and the number of dyads the concepts are part of. Several studies have revealed that disputes over two sets of rival paradigms – Keynesian versus ordoliberal, and intergovernmental versus supranational – underlie decision making in the domain of European economic and monetary integration (Dullien and Guérot Citation2012; Dyson Citation1999; Van Esch Citation2007, Citation2012, Citation2014; Young Citation2012). As the literature indicates proximity in principled beliefs fosters collaborative leadership, leaders’ positions on these two value-dimensions are examined. All concepts in the CMs were coded as belonging (more) to one of the rival paradigms using preconstructed coding manuals. The concepts were coded independently by two raters. The coding returned a Cohen’s Kappa of .651 for the economic and .676 for the European integration dimension, indicating substantial inter-rater reliability for both dimensions (Gwet Citation2014). The authors discussed the remaining differences until agreement was reached on the final assessment. To establish the score of the leaders on each of the dimensions, the saliency of all the positively valued concepts per category were added up.2 To facilitate comparison across leaders and trios, the resulting scores are represented as percentage points of the aggregated saliency of the CM.

Table 1. Overview of selected trios and cases.

To ascertain the level of similarity of beliefs within the respective trios, we first study each trio individually, evaluating what the most salient concepts in their map are per dimension and category. Second, we calculate the saliency per paradigm.3 Third, we calculate per trio the standard deviations of the scores of the leaders per dimension and category. The lower the standard deviation, the more closely the three leaders are aligned in their beliefs.

Finally, we conducted an expert survey to establish the level of the perceived success of each trio’s collaborative leadership. Expert surveys ‘are rarely intended to serve as representative samples of a well-defined population’; still, they are a particularly useful method for ‘difficult-to-measure phenomena’, such as the quality of collaborative leadership (Maestas Citation2018: 590, 585). An expert survey can be considered as valid ‘if one accepts on face value that these [selected] experts are qualified to make these judgments, and that these judgments are superior of any other easily reachable group’ (O’Malley Citation2007: 14). All the experts in our survey are academic scholars who have widely published on the trios under study, and EMU more broadly (for similar expert surveys, see O’Malley Citation2007).4 They were selected on the grounds of having first-hand empirical expertise in the topic matter as manifested by their own research based on, for example, the conduction of expert interviews, archival research or participant observations. Given the relatively small field of scholarship on the Franco-German tandem and Commission leadership in the field of EMU governance, a relatively high number of scholars participated in this survey (17 out of 26 invitees, response rate of 65%). As the four trios span across 30 years, an expert survey among present and former EU officials – while providing a more first-hand account of the collaboration efforts – would likely have shown a much higher participation of observants of the recent cases and thereby potentially have introduced a bias in the results. In addition, to increase the validity of our findings, we conducted a literature-search for existing evaluations of the leadership of the trios.

The survey consisted of five statements per trio. To capture the full meaning of the term ‘successful collaborative leadership’ and taking into account that collaborative leadership may be more or less successful (cf. Müller and Van Esch Citation2019), three questions pertained to the quality of the collaboration between the leaders and two to the level of success they achieved (see supplementary material for the list of questions). The experts were asked to what extent they disagreed or agreed with the statements on a 5-point scale. By comparing the rating of the trios’ collaborative leadership with the congruence in their beliefs, we explore to what extent and how a meeting of minds is related to successful collaborative leadership. No benchmarks for belief proximity or successful collaborative leadership exist in the literature, therefore conclusions will be based on the ranking of the leadership trios.

Successful collaborative leadership in EMU

In the long history of European Economic and Monetary Union, several major events took place in which leaders collaborated to make a grand bargain possible or solve a major crisis. Despite the complexity of making such a judgement, the differences in context and the leadership challenge at hand, the literature on European integration history includes some evaluations of how well the leaders in our study collaborated.

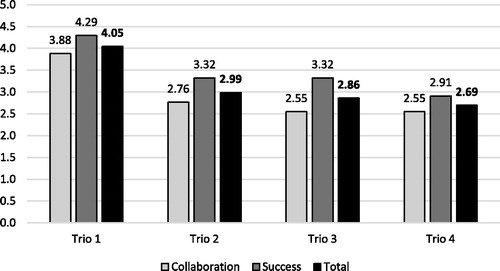

The first major event in the creation of Economic and Monetary Union was the publication of the Delors report (17 April 1989), on which EMU was later built (Endo Citation1999). The trio that oversaw the establishment of EMU in 1991, French president François Mitterrand, German chancellor Helmut Kohl and Commission president Jacques Delors, is generally seen as a team that worked well together and succeeded in constructing the compromise on which EMU was built (Dinan Citation2004; Krotz Citation2010; Müller Citation2019; Van Esch Citation2012). This judgement is shared by the experts who participated in our survey. As shows, this trio is perceived as the most successful in terms of collaborative leadership, with an average score of 4.05, ahead of the other leadership teams by more than a full point on the scale.

Figure 1. Expert opinion about the successful collaboration of the leadership trios in the domain of EMU.

The physical introduction of the single currency on 1 January 2002 was another major event in the history of EMU (Dinan Citation2004). The trio consisting of French president Jacques Chirac, German chancellor Gerhard Schröder and Commission president Romano Prodi faced strong resistance among European citizens due to the fiscal and social welfare adjustments needed in the run up to the Euro (Tömmel Citation2014). As such, a collective effort was required to make the introduction of the Euro a success. However, as a leadership task this was less challenging than those posed by the other three events since the decision was made before they took office.5 In the literature, judgements of the working relationship of these leaders are scarce; however, the experts that participated in the survey ranked this trio second in terms of successful collaborative leadership, with an average score of 2.99.

In late 2009, the EU was confronted by the Eurozone crisis, which posed a challenging leadership task for German chancellor Angela Merkel, French president Nicolas Sarkozy and Commission president José Manuel Barroso. In the literature, the lack of a common understanding between the French and German leaders is generally perceived as one of the causes of the crisis’ longevity, especially during its first phase (Dinan Citation2011; Schild Citation2012). Merkel and Sarkozy reconciled in 2010, which resulted in a better working relationship and substantially contributed to the Council decision on the first fiscal support package for Greece (2 May 2010) (Dinan Citation2011). Nonetheless, when asked about the collaboration and success of this trio, the experts in our survey judged them slightly less favourably than trio 2, with an average score of 2.86. This difference is due to the trio’s lower score for quality of collaboration, rather than the success of its collaborative outcome (see ).

Over the next five years, the Eurozone crisis led to a substantial polarisation and intergovernmentalisation of decision making, making it difficult for EU leaders to successfully exert collaborative leadership (Fabbrini and Puetter Citation2016; Risse Citation2015). Against this backdrop, Chancellor Merkel, French president François Hollande, and Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker had to face the challenge of dealing with the 2015 (re)negotiation of the second and third Greek fiscal support packages to which the Council agreed on 12 July 2015. EU scholars paint a less than favourable picture of their collaboration (Dinan Citation2016; Tömmel Citation2019; Van Esch Citation2017), which is corroborated by the outcome of the expert survey: In the respondents’ judgement, the trio appears least successful in its collaboration among the four groups studied, with an average score of 2.69.

Comparing EU leaders’ beliefs: a meeting of minds?

The results of our expert survey indicate different levels of successful collaboration among the four leadership trios, with Mitterrand-Kohl-Delors being perceived best and Hollande-Merkel-Juncker worst. In this section, the similarities in the leaders’ belief systems are compared, among and across the trios.

Mitterrand, Kohl and Delors: launching EMU (1989)

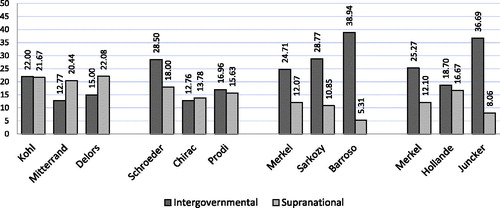

The CM of German chancellor Kohl indicates that he was a proponent of the establishment of EMU, even before the fall of the Berlin Wall (S = 7, cf. Van Esch Citation2012). However, in terms of the mode of integration in this field, Kohl had no clear preference for either intergovernmental or supranational arrangements (). While he seems to have valued supranational policies as a means to further political integration (S = 7), in his view both intergovernmental and supranational arrangements fostered economic development, German reunification, social justice and democracy (S = 12, 9, 1, 1). In contrast, Mitterrand’s rationale for supporting further European integration seemed to be predominantly geopolitical. He believed that a united Europe led by the French had the potential to develop into a third superpower (S = 7, 6), safeguard its independence, and foster both European democratic ideals and French interests (S = 8, 5, 3). Concerning the form of European integration, Mitterrand supported supranational decision making in the economic and monetary realm (but not in other domains, cf. Germond Citation2013: 10–11). In fact, the supranational dimension is almost twice as salient as intergovernmental governance in his CM. The concept of ‘European unification’ even emerges as Mitterrand’s top-ranking belief (S = 26). Finally, Delors’ CM indicates that he focussed almost completely on the further development of the European Monetary System (S = 15), the Single European Act (S = 12) and the plans for monetary integration and capital liberalisation that were associated with them (S = 7, 12, cf. Müller Citation2017, Citation2019). Delors associated EMU positively with welfare, employment and the benefit of society. Although he referred to both monetary unification and cooperation in his speeches, the overall analysis indicates a strong belief in further supranational integration in this domain (cf. Endo Citation1999: 106).

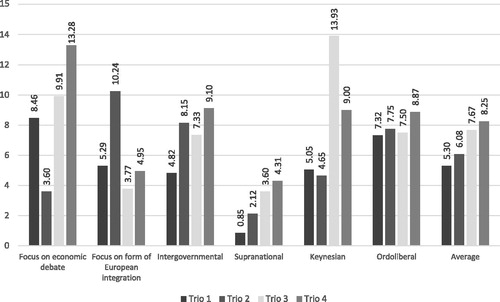

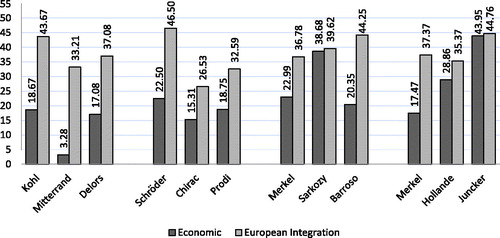

Figure 2. The European integration beliefs of the leadership trios (% of total salience of map concepts).

With regard to the economic paradigm, the analysis shows that Kohl’s preferences were very pronounced and that he internalised the main tenets of the ordoliberal paradigm (): Kohl was convinced of the need to maintain price stability (S = 13) and strict budgetary policies. In contrast, economic issues seem to have left Mitterrand indifferent. The few concepts he distinguished, like employment, economic growth and government support for industry (S = 5, 1, 1), put him in the Keynesian school of thought. However, the saliency value of his Keynesian beliefs occupies only around 3% of his map. Of this trio, Delors comes across as the most Keynesian, although – in contrast to Mitterrand – he also voiced some ordoliberal ideas. However, his CM shows a greater focus on (more) Keynesian values like employment than on ordoliberal values such as price stability and sound public finances (S = 11, 5, 2).

Finally, the analysis shows that ideas on European integration as well as economic topics held a pivotal role in Chancellor Kohl’s belief system, while the latter did not feature prominently in the CM of Mitterrand. Delors took a middle position. In addition, for each of the three leaders the mode of European integration was considerably more salient than economic policy ().

Figure 4. The overall saliency of economic, and European integration beliefs of the leadership trios (% of total salience of map concepts).

To sum up, on the mode of integration in the field of EMU, a reasonable level of consensus existed among the trio: They all supported supranational integration to more or lesser extent rather than intergovernmental integration, albeit for very different reasons. With regard to their economic preferences, the leaders did not see eye to eye. Whereas Mitterrand and especially Delors adhered to the Keynesian paradigm, Kohl held strong ordoliberal beliefs. Finally, all three leaders – and Mitterrand in particular – assigned more value to the form of European integration than the economic paradigmatic debate.

Chirac, Schröder and Prodi: introducing the Euro to the public (2002)

Chancellor Schröder’s CM indicates that he was a strong proponent of European integration and the single currency (S = 16) but favoured a more intergovernmental over supranational functioning of EMU (). For him, issues like the benefit for member states of joining EMU and European economic cooperation (not unification) had high saliency (S = 12, 6). He also believed intergovernmental cooperation would lead to more public support and guarantee the survival of the EU (S = 6, 5). The majority of supranational concepts – like European unification and European political unification (S = 2, 3) – had a much lower saliency in Schröder’s belief system than did his intergovernmental ideas. French president Chirac’s beliefs regarding the form of European governance show almost equal support for intergovernmental and supranational integration (13% versus 14%, ). However, he seemed to prefer supranational policies like the pooling of sovereignty (S = 8) predominantly because he felt this served to benefit the member states and France in particular (S = 6, 8). Commission president Prodi’s map is similarly balanced (17% versus 16%). For Prodi, supranational policies like a single capital market, the idea that the Eurozone should speak with one voice and a smooth introduction of the Euro (S = 9, 3, 3) all featured high in his rhetoric (Tömmel Citation2013: 801) and are seen as having led to a more successful EMU, greater public support and a stronger EU (S = 3, 2, 2). However, he also adhered to some intergovernmental concepts with a strong focus on the benefits of EMU for member states, debtor states in particular, and a support for stronger economic governance (not unification) of the Eurozone (S = 8, 4, 7).

Turning to the economic paradigm, the similarity between the trio’s members disappears. Schröder’s CM shows a strong ordoliberal conviction (18% versus 5% Keynesian, ). This is the result of the relatively high saliency of ordoliberal concepts like fiscal consolidation and discipline, and sound single monetary policy (S = 10, 5, 3). As for Chirac, his economic views were skewed towards Keynesianism, with high scores for concepts like economic growth, employment and devaluation (S = 11, 8, 3) and an almost complete absence of ordoliberal ideas. Finally, Prodi’s economic beliefs closely resembled those of Schröder both in paradigm, aim and preferred instruments: In the Commission president’s CM, ordoliberal convictions are almost three times as salient as Keynesian ideas (15% versus 3.5%). Among his ordoliberal ideas, price stability has by far the highest saliency, followed by credible public finances and fiscal discipline (S = 11, 4, 3). His Keynesian concepts have consistently lower saliency, with employment (S = 3) ranking highest.

In terms of the overall saliency of European and economic integration beliefs, it is notable that for Schröder and Prodi European integration was more than twice as salient as economic integration (). For Chirac, the balance was less skewed, but he was still more concerned about the form of European integration than the underlying economics.

Overall, this trio’s cognitive maps reveal some differences regarding the form of European integration, with a high score on intergovernmentalism for Schröder and balanced views for Chirac and Prodi. However, the two latter partly saw supranational arrangements as means to promote national interests. In any case, their differences in economic views were more pronounced, although this dimension was less salient to each of the leaders which may have softened the weight of their economic disagreements.

Merkozy and Barroso: the challenge of the first Greek package (2010)

The analysis of Chancellor Merkel’s CM reveals that she was a proponent of intergovernmental rather than supranational solutions to the Eurozone crisis (25% versus 12%, ). Among the intergovernmental concepts that featured most prominently in her rhetoric were compliance with SGP norms and the German debt brake (S = 7, 4) which in her eyes benefitted Germany and fostered the credibility and stability of EMU as well as fiscal discipline (S = 6, 7, 6, 2). Only two supranational concepts – the stability of the single currency and the general credibility of EMU (S = 7, 6) – have high saliency. According to Sarkozy’s map, he also was a strong proponent of intergovernmental rather than supranational integration (29% and 11%). The most dominant intergovernmental concepts in his CM comprise European economic cooperation, French-German cooperation and raising taxes (S = 9, 5, 8), whereby the former two are considered to have benefited all and fostered the resilience of the EU. The latter is seen to increase employment and improve government finances. Of the 70 concepts in Sarkozy’s map, only four were clearly supranational. Turning to José Manuel Barroso, his map shows he was even more intergovernmental than those of his national counterparts (39% versus 5%). Barroso’s most salient intergovernmental concepts are the benefit of member states, the fiscal support package, stronger economic governance of the Eurozone and European coordination (S = 36, 9, 8, 4). Moreover, Barroso used many neutral terms in his speeches, like European integration, not specifying the precise level of integration he had in mind (cf. Müller Citation2016, Citation2017). This result is striking since Commission presidents are generally expected to advocate for supranational integration to strengthen the role of the Commission in EU decision making (Dinan Citation2011; Endo Citation1999). This may partly be explained by Barroso’s support for some crisis measures that were inherently intergovernmental by nature.

With regard to the trio’s economic beliefs, the analysis shows that Chancellor Merkel had a strong ordoliberal outlook on economic and monetary policy making, almost five times as salient as her Keynesian views (20% versus 3.5%, ). Among the ordoliberal arguments, Merkel’s pleas for the compliance with SGP norms, sound public finances and the German debt brake feature most prominently (S = 7, 4, 4). She also referred favourably to several Keynesian crisis measures, like the fiscal support packages and general bailouts (S = 1, 3), but their saliency is low by comparison. Sarkozy took the opposite stance and overwhelmingly favoured a Keynesian approach to the crisis (31% over 8%).6 Among the most dominant Keynesian concepts in his map are government investment and leniency towards budgetary deficits (S = 17, 9). Although Sarkozy also stressed that poor public finances lay at the root of the crisis and both sound public finances (S = 4) and compliance with SGP norms (S = 1) were necessary, these beliefs were far less salient. Barroso took a middle position, with his Keynesian concepts scoring more than twice as high as his ordoliberal ideas (15% versus 6%). This is reflected in the high saliency of concepts like fiscal support packages, employment and economic growth (S = 9, 10, 4). In addition, Barroso also voiced his support for forms of economic stimulation as included in the Lisbon Strategy. The ordoliberal concepts he mentioned – like fiscal discipline and consolidation – had low saliency (S = 1, 3) and were not linked to the sovereign debt crisis (cf. Müller Citation2017).

Finally, the analysis shows that while Chancellor Merkel and Commission president Barroso were more concerned with the form of European integration than economic strategy, French president Sarkozy paid almost equal attention to both dimensions ().

All in all, while Merkel and Sarkozy were at opposite sides of the economic debate on the crisis, they saw eye to eye in terms of the mode of European integration. Agreement on the saliency of the latter dimension may have facilitated their collaboration.

Hollande, Merkel and Juncker: the third Greek package (2015)

Reviewing the beliefs of the final trio reveals that Chancellor Merkel’s convictions regarding European integration remained almost the same throughout the Eurozone crisis (). Among the prominent intergovernmental concepts is again ‘stronger economic governance of the Eurozone’ which is seen to benefit the member states – Germany, in particular (S = 18, 12, 10). Although Merkel also favoured the strengthening of the economic union and the institutional reform of EMU (S = 5, 4) as means to battle the Eurozone crisis and public debt, as well as to foster competitiveness, these ideas had substantially lower saliency. In contrast, Hollande had a balanced view on the mode of European integration in the economic and monetary field (19% and 17%). One of the most important intergovernmental concepts in Hollande’s map is ‘negotiations between member states’ which in his eyes helped to prevent a Grexit and benefitted the member states (S = 4, 6, 10). A successful EMU and the European Investment Plan suggested by Jean-Claude Juncker (S = 4, 3) are his most prominent supranational beliefs. Commission president Juncker in turn is a strong proponent of an intergovernmental mode of European governance (25% versus 12%), focussing mainly on the third Greek bailout package which he felt was in the benefit of the member states and would lead to improvements in national administrations (S = 32, 9, 5). With the exception of his European Investment Plan (S = 10), references to supranational concepts are substantially less salient.

Concerning the economic paradigm, Merkel’s beliefs remained relatively stable and clearly ordoliberal throughout the crisis. Although her Keynesian beliefs slightly increased, her ordoliberal convictions were still dominant (13% versus 4.5%, ). Merkel’s most salient ordoliberal concepts again include compliance with SGP norms and fiscal consolidation, as well as the strengthening of the SGP (S = 8, 8, 4). Her Keynesian beliefs feature a concern for economic growth (S = 8). In contrast, Hollande emerges as a convinced Keynesian with a saliency score that is almost three times as high as that of his ordoliberal ideas (21% and 8%). For Hollande, the most important Keynesian concepts also encompass economic growth as well as employment, and a rejection of fiscal discipline (S = 14, 4, 6). Although the French president also mentioned sound public finances (S = 4), their overall saliency of his ordoliberal ideas is low. Finally, Juncker’s economic beliefs show a slight leaning towards ordoliberal thinking (25% versus 19%). His most dominant ordoliberal concepts comprise support for the third Greek bailout package, fiscal consolidation and sound public finances (S = 32, 8, 8). His Keynesian ideas feature economic growth and employment, as well as his European Investment Plan (S = 15, 5, 10).

While the fourth trio all placed considerable focus on European integration (between 35% and 45%, ), they differ significantly in the extent to which they addressed the underlying economic paradigmatic debate: Juncker dedicated about 40% of his remarks to this, more than twice as much as Merkel, while Hollande held a middle position.

In sum, this trio strongly favoured intergovernmental integration in the EMU domain but for very different reasons. Moreover, they were strikingly divided in their economic convictions, with Merkel holding an ordoliberal, Juncker a very strong ordoliberal and Hollande a strong Keynesian stand. In fact, some of their economic preferences were polar opposites. As especially Hollande and Juncker felt that economics was a relatively – although not the most – important issue, this may have made collaboration especially difficult.

The in-depth examination of the leaders’ beliefs provides several important insights:

The form of European integration was more salient in the minds of all four trios than the economic dimension, but the saliency of economic ideas increased over time;

Within the trios more agreement existed with regard to the form of European integration than the appropriate economic approach;

Over time, the trios developed a stronger preference for intergovernmental integration, whereas no clear longitudinal trend in the economic beliefs is visible;

A clear national division in economic thinking is apparent with all German chancellors adhering to the ordoliberal and French presidents (and Delors) to the Keynesian paradigm, while the Commission presidents differ considerably among each other;

The belief systems of all leaders include intergovernmental as well as supranational and Ordoliberal as well as Keynesian arguments and goals, thereby pragmatically combining beliefs derived from different paradigms (Princen and Van Esch Citation2016).

If cognitive proximity is indeed related to collaborative leadership, these results suggest that successful collaborative leadership became more difficult over time, especially due to differences in opinion regarding economic policy. However, since all leaders pragmatically combine ideas that derive from rivalling paradigms – rather than seeing these ideas as incommensurable – successful collaborative leadership may still have been possible.

Collaborative leadership: a matter of cognitive proximity

In order to establish whether a relationship exists between cognitive proximity and successful collaborative EU leadership, shows the average standard deviation of the belief scores per trio and category (last set of bars). These scores indicate each trio’s degree of cognitive proximity, whereby the lower the SD, the closer the proximity in the trio’s beliefs. Combined with the results of the expert survey, these scores provide a first indication that a higher level of cognitive proximity is indeed associated with more positive evaluations of the trios’ collaborative success.

The findings show that while the Mitterrand-Kohl-Delors trio was seen by the experts as the most successful, both in terms of the process of collaboration and the success of the collaborative outcome, this leadership team also has the closest average alignment in beliefs (lowest average SD, , last set of bars). The team Chirac-Schröder-Prodi comes in second both in terms of the experts’ evaluation and their cognitive proximity. At some distance, the third trio, Sarkozy-Merkel-Barroso, follows again in correspondence with the expectation. Finally, the fourth trio, Hollande-Merkel-Juncker, is least aligned in the members’ overall beliefs and was scored lowest by the experts in terms of collaborative process and success of its outcome.

However, the alignment between belief convergence and successful collaborative leadership is only complete for the average SD over all categories and for the leaders’ beliefs on supranational integration. In the categories ‘intergovernmental integration’, ‘ordoliberalism’ and ‘focus on economic debate’ one trio is misaligned while for the categories ‘Keynesianism’ and ‘focus on European integration’ the rankings of belief convergence and successful collaborative leadership are misaligned. This suggests that at a more specific level, the relation between ideas and collaborative leadership differs and leaders’ overall consensus, and especially consensus on the mode of European integration, plays a more important role in the success of collaborative leadership, at least for the cases in this study. Finally, the trio with the most pro-supranational beliefs () as well as the greatest consensus on their evaluation of supranational governance () is also seen as most successful in their collaborative leadership by the experts.

However, some methodological caveats apply. Given the small number of cases these results should be treated with caution and would require further corroboration. This is especially the case because of the limited differences between the trios in the outcomes of the survey. Moreover, while an expert survey is a valuable method in a complex comparison of historical cases, an in-depth study of collaborative leadership would ideally also include the evaluations of those directly involved and affected. Finally, and more fundamentally, in order to establish whether a causal relationship exists, a different research design including, for instance, process tracing is required (cf. Schoeller Citation2019).

Conclusion

Acknowledging the important role collaborative leadership between key EU leaders has played in the European project, this article set out to provide an agency perspective on EU collaborative leadership. It has aimed to draw lessons from the literature about the nature and conditions of collaborative leadership at the European level and to empirically explore whether cognitive proximity among key intergovernmental and supranational EU leaders is associated with successful collaborative EU leadership.

The empirical evidence presented in this article provides a first corroboration of the relationship between cognitive proximity and successful EU collaborative leadership. While many factors are at play in EU politics, in the cases under study our findings show that the greater the overall cognitive proximity within the leadership trios, the more favourably their collaboration was judged by the experts. However, our study also shows that for certain specific dimensions belief proximity is more strongly correlated with successful collaborative leadership than others. Remarkably, and despite the fact that the debate over the proper economic approach to the Eurozone crisis dominated Europe’s public spheres, our findings show that congruence in leaders’ beliefs regarding the form of European integration was more strongly associated with successful collaborative leadership than proximity in economic beliefs. This may be the case because, as our study also shows, the former dimension was more salient in the leaders’ belief systems than the latter. On a theoretical level, this may suggest that – in addition to the extent to which beliefs are shared – the degree to which a belief-dimension is salient in the minds of leaders may also affect the success of collaborative leadership.

These conclusions should not be interpreted as refuting the argument of scholars of EU negotiation theory who argue that rivalling, but reconcilable ideas contribute to EU cooperation. In our study, we set out to capture leaders’ cognitive proximity in terms of their general adherence to four political and economic paradigms. Our findings suggest that at this level of abstraction, more cognitive proximity may foster successful EU collaborative leadership. Yet at a more detailed level, many differences between the trios’ belief systems exist. In fact, our in-depth analysis of leaders’ beliefs suggests that collaborative leadership may still arise when their ideas on specific dimensions or regarding particular policy measures do not align. In addition, in contrast to what is assumed in the literature on paradigms, the leaders in our study are cognitively flexible, pragmatically combining and reconciling beliefs that are derived from different paradigms (cf. Princen and Van Esch Citation2016): Several leaders in our study justify their support for supranational integration by arguing it serves the national interest or vice versa, and all of them simultaneously support measures that belong to the rivalling economic paradigms of ordoliberalism and Keynesianism. Only in the case of Merkel and Hollande did true irreconcilable differences with regard to fiscal discipline emerge. In the minds of the leaders in our study, there seems to be little that cannot be cognitively reconciled.

Finally, our study also shows that leaders’ beliefs – and in association, the chances that successful collaborative leadership emerges – are not formed in a vacuum and that leaders’ beliefs include a lot of references to the context. Many factors exert an influence on the cognitive maps of political leaders (cf. Swinkels Citation2019) and may induce (cognitive) compromises. One of the most important findings in this regard is that the trend towards more polarisation and intergovernmentalism in EU politics has seeped into the belief systems of political leaders. Cognitive proximity declines over time and after the formidable trio of Kohl, Mitterrand and Delors, supranational thinking on issues concerning EMU seems to have become a thing of the past, even among Commission presidents (Müller Citation2017). Our study thus suggests that more polarisation – especially regarding the preferred form of integration – as well as the increased saliency of the debate on EU integration may therefore also hamper EU collaboration via the minds of key EU leaders. In the current era of political turmoil, the findings of this study are therefore highly consequential. For whereas EU decision making has always relied on collaboration, it is especially in times of crisis that successful EU collaborative leadership is most crucial.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (53.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding from the EU’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program, under grant agreement number 649484-Transcrisis. They also would like to thank the 17 experts who participated in the survey for their cooperation. In addition, the authors are very grateful to the participants of the ECPR Joint Sessions workshop ‘The Role of Leadership in EU Politics and Policy Making’, held 10–14 April 2018 in Nicosia, as well as the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Henriette Müller

Henriette Müller is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Leadership Studies at New York University Abu Dhabi. Her research focuses on political leadership as well as women and leadership with a regional focus on the EU and GCC states. Her first book Political Leadership and the European Commission Presidency will be published with OUP in 2019. She has published in Politics and Governance, Journal of European Integration and West European Politics, among others. [[email protected]]

Femke A. W. J. Van Esch

Femke A.W.J. Van Esch is an Associate Professor in European Integration and Leadership at the Utrecht School of Governance. Her research interests include: European (monetary) integration, political leadership, ideas, cognitive mapping and German and French politics. She has published in Journal of European Public Policy, West European Politics and Journal of Common Market Studies, amongst others. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 For a detailed explanation of the method, see Van Esch (Citation2007) and Van Esch et al. (Citation2016).

2 From a CM one can derive to what extent a concept in a map is seen as positive or negative. Only the saliency of positively valued concepts is included in the total saliency per category, except for those paradigms that place the rejection of certain policies at the core of their thinking (e.g., the ordoliberal rejection of running large deficits).

3 This is calculated using the following equations of standard deviations: and

4 Of the 26 experts in the field of the European Economic and Monetary Union that were invited, 15 EU scholars and two experts working both as scholars and practitioners participated in the survey. The experts are either associate or full professors and come from 11 countries, including Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom and United States. The survey was open from 23 July until 9 September 2018.

5 This was also noted by three of the experts. Moreover, the number of ‘neutral’ (3-point) responses to the statements about this trio was far greater than for the others (34 versus 8, 19 and 20). Omitting these does not change the ranking of the cases.

6 Previous research indicates that, during the crisis, a convergence in the beliefs of Merkel and Sarkozy took place (Van Esch Citation2014).

References

- Ansell, Chris, and Alison Gash (2007). ‘Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18:4, 543–71.

- Archer, David, and Alex Cameron (2013). Collaborative Leadership: Building Relationships, Handling Conflict and Sharing Control. New York: Routledge.

- Avolio, Bruce J., Fred O. Walumbwa, and Todd J. Weber (2009). ‘Leadership: Current Theories, Research, and Future Directions’, Annual Review of Psychology, 60:1, 421–49.

- Axelrod, Robert, ed. (1976). Structure of Decision: The Cognitive Maps of Political Elites. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Bastian, Mathieu, Sebastien Heymann, and Mathieu Jacomy (2009). ‘Gephi: An Open Source Software for Exploring and Manipulating Networks’. International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media.

- Bligh, Michelle (2017). ‘Leadership and Trust’, in Joan Marques and Satinder Dhiman (eds.), Leadership Today: Practices for Personal and Professional Performance. New York: Springer, 21–42.

- Burns, James MacGregor (2010 [1978]). Leadership. New York: HarperCollins.

- Chrislip, David D., and Carl E. Larson (1994). Collaborative Leadership: How Citizens and Civic Leaders Can Make A Difference. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Cramme, Olaf (2011). ‘In Search of Leadership’, in Loukas Tsoukalis and Janis A. Emmanouilidis (eds.), The Delphic Oracle on Europe: Is There a Future for the European Union? Oxford: Oxford University Press, 30–49.

- Dinan, Desmond (2004). Europe Recast: A History of European Union. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dinan, Desmond (2011). ‘Governance and Institutions: Implementing the Lisbon Treaty in the Shadow of the Euro Crisis’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 49:1, 103–21.

- Dinan, Desmond (2016). ‘Governance and Institutions: A More Political Commission’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 54:1, 101–16.

- Dullien, Sebastian, and Ulrike Guérot (2012). ‘The Long Shadow of Ordoliberalism: Germany’s Approach to the Euro Crisis’, ECFR Policy Brief, 49, 16.

- Dyson, Kenneth (1999). ‘The Franco-German Relationship and Economic and Monetary Union: Using Europe to “Bind Leviathan”’, West European Politics, 22:1, 25–44.

- Endo, Ken (1999). The Presidency of the European Commission Under Jacques Delors: The Politics of Shared Leadership. Oxford: Macmillan Press.

- Fabbrini, Sergio, and Uwe Puetter (2016). ‘Integration without Supranationalisation: Studying the Lead Roles of the European Council and the Council in Post-Lisbon EU Politics’, Journal of European Integration, 38:5, 481–95.

- Fletcher, Joyce K., and Katrin Käufer (2003). ‘Shared Leadership: Paradox and Possibility’, in Craig L. Pearce and Jay A. Conger (eds.), Shared Leadership: Reframing the Hows and Whys of Leadership. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 22–47.

- Germond, Carine (2013). ‘Dynamic Franco-German Duos: Giscard-Schmidt and Mitterrand-Kohl’, in Erik Jones, Anand Menon, and Stephen Weatherill (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the European Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 14.

- Gwet, Kilem L. (2014). Handbook of Inter-Rater Reliability: The Definitive Guide to Measuring The Extent of Agreement Among Raters. Gaithersburg: Advanced Analytics.

- Haas, Ernst B. (1958). The Uniting of Europe: Political, Social, and Economic Forces, 1950-1957. Standford: Stanford University Press.

- Haas, Peter M. (1992). ‘Introduction: Epistemic Communities and International Policy Coordination’, International Organization, 46:1, 1–35.

- Krotz, Ulrich (2010). ‘Regularized Intergovernmentalism: France-Germany and beyond (1963 –2009)’, Foreign Policy Analysis, 6:2, 147–85.

- Maestas, Cherie (2018). ‘Expert Surveys as a Measurement Tool: Challenges and New Frontiers’, in Lonna Rae Atkeson and R. Michael Alvarez (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Polling and Survey Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 583–607.

- Marfleet, B. Gregory (2000). ‘The Operational Code of John F. Kennedy during the Cuban Missile Crisis: A Comparison of Public and Private Rhetoric’, Political Psychology, 21:3, 545–58.

- Moravcsik, Andrew (1999). ‘A New Statecraft? Supranational Entrepreneurs and International Cooperation’, International Organization, 53:2, 267–306.

- Müller, Henriette (2019). Political Leadership and the European Commission Presidency. Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming.

- Müller, Henriette, and Femke A. W. J. Van Esch (2019). ‘The Contested Nature of Political Leadership in the European Union: Conceptual and Methodological Cross-Fertilisation’, West European Politics. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1678951

- Müller, Henriette (2016). ‘Between Potential, Performance and Prospect: Revisiting the Political Leadership of the EU Commission President’, Politics and Governance, 4:2, 68–79.

- Müller, Henriette (2017). ‘Setting Europe’s Agenda: The Commission Presidents and Political Leadership’, Journal of European Integration, 39:2, 129–42.

- Nielsen, Bodil, and Sandrino Smeets (2018). ‘The Role of the EU Institutions in Establishing the Banking Union: Collaborative Leadership in the EMU Reform Process’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:9, 1233–56.

- O’Malley, Eoin (2007). ‘The Power of Prime Ministers: Results of an Expert Survey’, International Political Science Review, 28:1, 7–27.

- Princen, Sebastiaan B. M., and Femke A. W. J. Van Esch (2016). ‘Paradigm Formation and Paradigm Change in the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact’, European Political Science Review, 8:3, 355–75.

- Renshon, Jonathan (2008). ‘Stability and Change in Belief Systems: The Operational Code of George W. Bush’, Journal of Conflict Resolution, 52:6, 820–49.

- Renshon, Jonathan (2009). ‘When Public Statements Reveal Private Beliefs: Assessing Operational Codes at a Distance’, Political Psychology, 30:4, 649–61.

- Risse, Thomas (2015). ‘European Public Spheres, the Politicization of EU Affairs, and Its Consequences’, in Thomas Risse (ed.), European Public Spheres: Politics Is Back. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 141–64.

- Sandholtz, Wayne, and John Zysman (1989). ‘1992: Recasting the European Bargain’, World Politics, 42:1, 95–128.

- Schild, Joachim (2010). ‘Mission Impossible? The Potential for Franco–German Leadership in the Enlarged EU’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 48:5, 1367–90.

- Schild, Joachim (2012). ‘Leadership in Hard Times: France, Germany and the Management of the Eurozone Crisis’, Paper Presented at the UACES Conference, 2–5 September, University of Passau.

- Schoeller, Magnus G. (2018). ‘The Rise and Fall of Merkozy: Franco-German Bilateralism as a Negotiation Strategy in Eurozone Crisis Management’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 56:5, 1019–35.

- Schoeller, Magnus G. (2019). ‘Tracing Leadership: The ECB’s “Whatever It Takes” and Germany in the Ukraine Crisis’, West European Politics. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1635801

- Smeets, Sandrino, and Derek Beach (2019). ‘Political and Instrumental Leadership in Major EU Reforms: The Role and Influence of the EU Institutions in Setting up the Fiscal Compact’, Journal of European Public Policy, 1–19. doi:10.1080/13501763.2019.1572211

- Swinkels, Marij (2019). ‘Beliefs of Political Leaders: Conditions for Change in the Eurozone Crisis’, West European Politics. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1635802

- Tömmel, Ingeborg (2013). ‘The Presidents of the European Commission: Transactional or Transforming Leadership?’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 51:4, 789–805.

- Tömmel, Ingeborg (2014). The European Union: What it is and How it Works. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tömmel, Ingeborg (2019). ‘Political Leadership in Times of Crisis: The Commission Presidency of Jean-Claude Juncker’, West European Politics. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1646507

- ‘t Hart Paul (2014). Understanding Public Leadership. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Van Esch, Femke A. W. J. (2007). ‘Mapping the Road to Maastricht. A Comparative Study of German and French Pivotal Decision Makers’ Preferences Concerning the Establishment of a European Monetary Union during the Early 1970s and Late 1980s’, unpublished PhD thesis, Radboud University Nijmegen, Faculty of Management Sciences.

- Van Esch, Femke A. W. J. (2009). ‘The Rising of the Phoenix: Building the European Monetary System on a Meeting of Minds’, L’Europe en Formation, 3, 133–48.

- Van Esch, Femke A. W. J. (2012). ‘Why Germany Wanted EMU: The Role of Helmut Kohl’s Belief System and the Fall of the Berlin Wall’, German Politics, 21:1, 34–52.

- Van Esch, Femke A. W. J. (2014). ‘Exploring the Keynesian–Ordoliberal Divide: Flexibility and Convergence in French and German Leaders’ Economic Ideas during the Euro-Crisis’, Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 22:3, 288–302.

- Van Esch, Femke A. W. J. (2017). ‘The Paradoxes of Legitimate EU Leadership: An Analysis of the Multi-Level Leadership of Angela Merkel and Alexis Tsipras during the Eurocrisis’, Journal of European Integration, 39:2, 223–37.

- Van Esch, Femke A. W. J., L. Brand, M. C. Joosen, S. Steenman, J. F. A. Snellens, and E. M. Swinkels (2016). Cognitive Mapping Coding Manual. Deliverable 3.1 for the TRANSCRISIS Horizon2020 Project, available at: http://www.transcrisis.eu/publications. (accessed 20 April 2018).

- Van Esch, Femke A. W. J., and Eelke de Jong (2019). ‘National Culture Trumps EU Socialization: The European Central Bankers’ Views of the Euro Crisis’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:2, 169–87.

- Verdun, Amy (1999). ‘The Role of the Delors Committee in the Creation of EMU: An Epistemic Community?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 6:2, 308–28.

- Walter, Uta M., and Christopher G. Petr (2000). ‘A Template for Family-Centered Interagency Collaboration’, Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Human Services, 81:5, 494–503.

- Webber, Douglas (1999). ‘Franco-German Bilateralism and Agricultural Politics in the European Union: The Neglected Level’, West European Politics, 22:1, 45–67.

- Young, Brigitte (2012). ‘The German Debates on Eurozone Austerity Programs: The Economic Streit and the Power of Ordoliberalism’, Paper Presented at the EU after the Crisis Conference, 6–7 December, Weimar.

- Young, Michael D., and Mark Schafer (1998). ‘Is There Method in Our Madness? Ways of Assessing Cognition in International Relations’, Mershon International Studies Review, 42:1, 63–96.