Abstract

Are government funds an opportunity or a threat to interest groups’ participation in policy-making? In answering this question, previous research has raised the question of the interrelatedness between access to policymakers and funding of interest groups’ activities. A popular argument represents funding opportunities as inhibitors of interest group access to policy-making because of the funds’ negative effect on an organization’s autonomy. In opposition to this view, many authors have argued that public funds open access opportunities and contribute to an active involvement of funded organizations in the policy process. This article provides a novel explanation for these contrasting findings. The effect of public funds on access critically depends on the type of contacts organizations have with policymakers. Funding might positively affect access initiated by policymakers (high threshold), but might not affect access initiated by interest groups (low threshold). Using survey data collected from more than 2000 organizations active in four European countries and at the EU level, the article shows that public funds are associated to an organization’s participation in policy-making but this correlation is indeed highly dependent on the type of contacts groups have with policymakers.

State funding of interest group communities is described in the literature as a system of direct transfers from government agencies to an organisation that seeks financial support with the aim of implementing a project or support administrative and organizational changes (Crepaz and Hanegraaff Citation2020).1 The existence of such mechanism is generally legitimised by the willingness of the state to support the development of civil society, ensure more efficient implementation, and add strength to the democratic process (Greenwood Citation2007; Kohler-Koch and Rittberger Citation2007; Saurugger Citation2008).

Research indicates that governments certainly ‘mould’ civil society through the allocation of public funds. This in turn affects the quality of democracy in various ways (Klüver and Saurugger Citation2013; Mahoney Citation2004). With the allocation of funds governments sustain organizations that would otherwise cease to exist because of lack of resources (Chaves et al. Citation2004; Klüver and Saurugger Citation2013; Smith Citation1999). In addition, funds can help organizations to improve their management structures, develop new targets, and widen the scope of their activities (Anheier et al. Citation1997; Leech Citation2006; Sanchez Salgado Citation2010). In principle, if imbalances in representation exist, public funds can hence correct existing biases in the system of interest representation, opening or closing channels of influence and participation (Bloodgood and Tremblay-Boire Citation2017; Mahoney and Beckstrand Citation2011; Sanchez Salgado Citation2014; Suarez Citation2011). On the other end, scholars also point towards a more pessimistic view in which public funds end up in the hands of overrepresented or wealthy groups creating thus more imbalances (Crepaz and Hanegraaff Citation2020; Persson and Edholm Citation2018). Moreover, governments could also make strategic use of public funds to pursue agendas that differ from citizen’s preferences with potential detrimental effects on representative democracy (Sanchez Salgado Citation2014).

One of the most direct ways to observe the intervention of public subsidies in democratic practices relates to the effect of funding on interest groups’ access to government (Anheier et al. Citation1997; Bloodgood and Tremblay-Boire Citation2017; Leech Citation2006; Sanchez Salgado Citation2010). With the provision of funds to organized interests, governments give the means, that might otherwise be deficient, to interest groups to voice their positions during the policy-making process. The European Commission (EC), for instance, often argues that its funds improve the input legitimacy of the EU’s political system and the quality of its policy proposals (European Commission Citation2001: 1; see also Greenwood Citation2007; Kohler-Koch and Rittberger Citation2007; Saurugger Citation2008). The question that arises is whether this argument actually holds in practice and whether funding schemes indeed increase the access opportunities of interest groups to the policy process.

The jury is, however, still out on whether or not government funding increases access opportunities for interest groups. Some authors have argued that there is a positive relation between access gained and public funding (Chaves et al. Citation2004; Sanchez Salgado Citation2014). Other studies have indicated that funded interest groups tend to gain less access to policymakers (Mosley Citation2012; Smith Citation2003). As a result, the extent to which funding actually supports a group’s political aspirations remains unclear.

In this article, we advance an original argument to explain these contradictory findings. In a nutshell, we argue that there are different types of access (see Binderkrantz et al. Citation2017), which are differently associated to public funding. We argue that public funding only affects access initiated by policymakers (high threshold) and does not clearly affect the access groups gain at their own initiative (low threshold). Our argument is based on the idea that interest groups might use funding in different ways, which do not necessarily increase the volume of their lobbying activity. Nevertheless, funding certainly increases an interest group’s legitimacy and credibility in the eyes of policymakers, which makes the latter more likely to invite interest groups to participate in the policy-making process (Nikolic and Koontz Citation2008).

We test our argument against a new and extensive dataset of over 2,000 organizations across four countries (Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, and Slovenia), and at the European Union (EU). This is currently by far the largest existing dataset that allows for testing hypotheses on the relationship between funding and access. Moreover, in each of these jurisdictions, a similar survey was conducted, allowing for a rigorous comparison across countries and political levels. This stands in contrast to former studies, which have focused on one country or one political system only. Compared to existing studies, both benefits – large N and variation across jurisdictions – allow us to provide a higher degree of generalization of the results.

Our findings contribute to several academic debates. First, by demonstrating the link between funding and access, we contribute to current debates on interest groups’ autonomy and independence (Anheier et al. Citation1997; Bloodgood and Tremblay-Boire Citation2017; Leech Citation2006; Sanchez Salgado Citation2010). Second, our findings help to understand the potential contribution of public funds to representative democracy. If we find that public funding is associated to bias in the access of interest groups instead of being associated to the support of an open and competitive system of decision-making, then we might conclude that existing funding schemes are not necessarily healthy for representative democracy. Third, we add to the extensive literature on why certain groups gain access to policymakers by adding funding as a new explanatory variable (Binderkrantz et al. Citation2015; Mahoney Citation2004). This literature tends to focus on supply-side factors, such as resources, group type, or the level of professionalization of groups. To these studies, we add a demand-side factor (Mahoney Citation2004), namely the stringent effect of funding by governments. Moreover, with regard to this literature we provide a broader perspective on what access to policymakers can entail. We hereby empirically confirm the usefulness of Binderkrantz et al.’s (Citation2017) analytical distinction of different types of access. Our results clearly highlight that the observed type of access drives the results of the study.

The article is structured as follows. The first two sections present the theoretical puzzle describing the relationship between the two variables. In the third and fourth section, we introduce our data collection strategy and present the results of our analyses. We end with some concluding remarks and a pathway for future research.

Public funding and its effects on access

Many scholars have recognized the importance of funding for interest groups. Within this body of research, scholars of the voluntary sector, for instance, have assessed the impact of government funds on an organization’s autonomy (Roberts Citation2007; Sanchez Salgado Citation2014), independence (Chaves et al. Citation2004), bureaucratization (Anheier et al. Citation1997), and level of professionalization (Suarez Citation2011). A common finding in this literature is that public funding influences the behaviour of the organization receiving it (Anheier et al. Citation1997; Chaves et al. Citation2004). With this idea in mind, scholars have tried to explain the extent to which public funding shapes state–society relations (Sanchez Salgado Citation2014).

A first set of studies on public funding of interest groups has focused on factors that influence the distribution of funds showing that while funding seeks to serve redistribution purposes, its allocation can be biased in favour of better-endowed and better-organised organizations (Crepaz and Hanegraaff Citation2020; Mahoney Citation2004; Mahoney and Beckstrand Citation2011; Sanchez Salgado Citation2014; Suarez Citation2011). A second body of literature focuses on the effects of public funds on the survival prospects of interest organizations (Child and Grönbjerg Citation2007) and organizational development (Chaves et al. Citation2004; Klüver and Saurugger Citation2013; Smith Citation1999) suggesting that funding is in many cases vital for the sustainment of an active interest community. A third set of studies focuses on the effects of funding on group strategies, such as outside lobbying and issue prioritization pointing towards mixed picture (Anheier et al. Citation1997; Bloodgood and Tremblay-Boire Citation2017; Leech Citation2006; Sanchez Salgado Citation2010).

One key question in this latter debate, and the focus of this paper, pertains to the effect of funding on access to policymakers. Even if the greatest bulk of public funds is directed to the implementation of public policies, their effects on access to decision-making processes remains crucial. Many scholars and policymakers argue that funding should give to groups with deficient resources the means to interact with state institutions (Greenwood Citation2007; Kohler-Koch and Rittberger Citation2007; Saurugger Citation2008). The question as to whether funding indeed leads to more frequent interactions between interest groups and policymakers is therefore an important one.

There is, however, a lack of agreement in the literature about the effects of funding on interest groups’ access to policymakers. Several authors have advanced the argument that interest groups getting substantial amounts of public funds would gain less access to policymakers. This argument follows two distinct logics, namely the ones of ‘resource dependency’ and ‘goal displacement’. According to the former reasoning, funded organizations might decide to participate less in policy-making because they fear punishment for unwelcomed advocacy. Organizations that wish to secure funds in the future might decide to avoid running the risk of ‘biting the hand that feeds them’. With this logic in mind, interest groups would be reluctant to criticize government lest they anger government officials and lose their funding (Smith Citation2003). For instance, even if actual instances of retribution in response to political activities are thought to be rare, civil society organization (CSO) staff has sometimes reported examples of punishment after advocacy activities by different means, including the discontinuing of grant support (Chaves et al. Citation2004).

According to the logic of goal displacement, funded organizations might decide to redirect attention and resources away from advocacy, dedicating instead more resources to other activities, such as project management and obtaining funding. Interest groups would be forced to shift their focus from advocacy to direct service to get public funds (Smith Citation2003). Organizations would thus become more active on topics where there is more funding (Sanchez Salgado Citation2014). More often than not, public funds also imply the professionalization of organizations such as CSOs, and this may lead interest groups to redirect attention and energy towards administrative activities, grant writing, and reporting (Chaves et al. Citation2004; Sanchez Salgado Citation2014).

A second group of authors have found the exact opposite association between funding and access. According to this set of studies, public funding increases access opportunities for interest groups. Most of the theoretical arguments underlying these findings have been developed specifically for CSOs and voluntary organizations but it is plausible that they can also be applied to other interest groups, such as business and professional organizations. This body of research indicates that government funding does not necessarily inhibit advocacy involvement (Chaves et al. Citation2004). Rather, government funding may ensure that CSOs get better access to decision-makers because of their established funding relationship (Mosley Citation2012). Interest groups getting public funds would seek more access, because they would like to improve the match between the service they provide and public priorities.

Getting government funding is also a good way to be considered as a leader or expert by government officials (Pratt et al. Citation2006). It needs to be considered that recent studies showed that funds tend to be granted to well-resourced and experienced organizations, which might already indicate their status of leader and expert (Crepaz and Hanegraaff Citation2020). Nevertheless, it cannot be denied that the same governments that operate as public donors also tend to open policy-making to organized interests with the aim of improving their processes of participatory democracy. In these situations, leadership, knowledge and status legitimacy appear to be important characteristics for the successful participation of interest groups in decision-making (Chaves et al. Citation2004; Suarez Citation2011). On the one hand, the receipt of funds confers status legitimacy to an organization and therefore increases the interest group’s chances of being granted access. This is confirmed by the fact that CSOs sometimes decide to apply for funds not because they need them, but rather because they want to improve their access opportunities (Sanchez Salgado Citation2014). On the other hand, funds are associated with more access simply because the transfer of financial resources to an organization might empower its political activity (Chaves et al. Citation2004; Leech Citation2006). Public funds, in particular EU funds, have also been associated with the positive growth of organizations’ financial security. For example, research has demonstrated that EU funds have also instigated a growth process among CSOs, especially humanitarian CSOs, transforming them into large CSOs with substantial budgets, enabling them to effectively engage in advocacy activities (Sanchez Salgado Citation2014).

In short, current findings on the effects of government funding are quite ambivalent. The difference in results may be explained by the fact that there are many relevant variables that need to be taken into account in the analysis, such as the size of the organization and its budget, the type of organization and its internal characteristics, the type of funding opportunities, the level of governance in which funding is supplied, and the more/less confrontational attitude of organizations towards state institutions (Chaves et al. Citation2004; Leech Citation2006; Roberts Citation2007; Sanchez Salgado Citation2014). While our emphasis is placed on the obtainment of public funding, we expect that some of these other variables are also significant to understand access. These alternative explanations are further discussed while presenting the control tests and robustness checks. To better discuss the relevance of alternative variables, we also propose a comparison including different levels of governance and different EU member states. This comparison between different national governments, which subsidize interest groups to a different degree, represents a novelty compared to previous works and increases the external validity of this study.

The argument: not all access is equal

The majority of studies on interest groups’ access conducted to date (including those not related to public funds) do not differentiate between different types of access. However, not all access is equal, because of the ‘inherently multifarious’ nature of the concept (Binderkrantz et al. Citation2017: 320). In general, access is usually understood as contact between an interest group and a political institution (Dür and Mateo Citation2013; Eising Citation2007). A more recent study by Binderkrantz et al. (Citation2017: 306) defines access as a situation in which ‘a group has entered a political arena (parliament, administration, or media) passing a threshold controlled by relevant gatekeepers (politicians, civil servants, or journalists)’. This definition stresses the complexity and multidimensionality of the concept of access because it ‘refers to different types of actors (i.e. organized interests and policymakers), multiple social mechanisms that lead to more or less access, and it can concern various arenas’ (Binderkrantz et al. Citation2017: 320).

An important distinction between various types of access is thus the threshold associated with the contact with policymakers. Some types of contact have a very low threshold: A member of parliament might take no or little notice of phone calls or email correspondences, but will not be able to prevent an organization from placing a call or sending an email. Low threshold access also includes groups reaching out to policymakers to make an appointment (Binderkrantz et al. Citation2017; Eising Citation2007). In this case, policymakers have some control, but since access is at the initiative of the interest group, the control is limited. There is a chance that policymakers will not turn down an invitation, but there is no guarantee that they will really listen or that they will initiate policy change.

A much more stringent type of access refers to access at the initiative of policymakers. In this instance, policymakers themselves reach out to organised interests, providing them with access to the policy-making process. The participation of interest groups in parliamentary committees and advisory councils is considered a relevant expression of this form of access (Broscheid and Coen Citation2003; Christiansen et al. Citation2010; Eising and Spohr Citation2017; Fraussen et al. Citation2015), because it allows policymakers to ‘keep a finger on the pulse of civil society’ (Bourgeois Citation2009: 22). Policymakers generally rely on interest group involvement in committees to increase input legitimacy. One could therefore expect that when policymakers provide this type of access, interest groups may have a better chance of being heard. For these reasons, the composition of such councils is often a contested matter, with policymakers having the last word over the selection of the participants (Fraussen et al. Citation2015). Being invited by policymakers is considered a high-threshold access type, since only a few prominent interest groups are actually invited on a regular basis.

We argue that the distinction of different types of access is crucial for a better understanding of the effects of public funds on access. While the literature has indicated that public funding does not seem to have a consistent effect on how funded groups seek access and how they gain it (low threshold), we argue that public funding has a clear effect on access at the initiative of policymakers (high threshold).

First, as far as contacts initiated by the interest group are concerned (low threshold), we expect that funded organizations are equally likely to reach out to policymakers as unfunded ones. Reaching out to policymakers is part of the overall strategy of interest groups, and is in particular related to inside strategies (Maloney et al. Citation1994). So-called inside strategies are ‘usually defined as lobbying activities that are directly aimed at policymakers’ (Hanegraaff et al. Citation2016: 569). This includes informal phone calls, emails, and physical meetings with policymakers and their staff.

We do not find theoretical reasons to expect that the extent to which funded groups decide to seek access and how they seek it are systematically correlated to public funding following a linear pattern. As discussed in the previous section, there are contradictory findings regarding the link between public funding and reaching out to policymakers (Mosley Citation2012; Sanchez Salgado Citation2014; Smith Citation2003). Funded interest groups have reasons both to decide to seek access (empowerment) and to avoid it (goal displacement and resource dependency). Even when interest groups may fear punishment from unwanted advocacy, this does not necessarily mean that they are no longer going to reach out to policymakers. They may just decide to avoid public confrontation and opt for collaborative strategies. Goal displacement may alter interest groups’ goals and priorities, but this will not necessarily reduce their direct contacts with policymakers regarding questions that interest the latter. Last but not least, interest groups’ strategies do not only depend on their relationship with policymakers, but also on other factors such as their constituencies, customers, and the media. Even business groups that seem less dependent on members have citizens to deal with, namely customers, stock holders, and clients. As far as the media is concerned, established interest groups have increasingly professionalized their communication efforts with the aim of maximizing their exposure to the media (Trapp and Laursen Citation2017). As we should not expect a systematic response in terms of seeking access as a result of funding, we therefore hypothesize:

H1: Interest groups that receive public funding are not more likely to gain access to policymakers at the initiative of the interest group than unfunded ones.

The situation is entirely different when policymakers’ responses to funded organizations are considered. As far as contacts initiated by policymakers are concerned, we argue that funded organizations are systematically more likely to be invited to participate in the decision-making process than unfunded organizations. Our expectations here are driven by whether the choice to reach out to certain groups is in the control of policymakers. In the framework of different theories of interest representation, scholars have studied the conditions under which policymakers include interest groups in platforms of negotiation or exclude them from such platforms (Christiansen et al. Citation2010).

Generally, groups that enjoy access are privileged and their regular involvement in policy-making at the legislator’s initiative is a function of a group’s level of insiderness (Fraussen et al. Citation2015). It should be noted that insiderness refers to the insider ‘status’ (Grant Citation2001) of an organization and not to the use of inside strategies. Broscheid and Coen (Citation2003), for example, have demonstrated that the European Commission (EC) tends to produce insiders when lobbying costs are low and the demand for input legitimacy (and therefore a wide consultation process) is low. Fraussen et al. (Citation2015) have illustrated that this process also happens at the national level, in so-called neo-corporatist systems, such as Belgium, where the government produces core insiders by distributing seats on advisory bodies to interest associations. These studies prove that governments mould interest group communities by deciding who is in and who is out.

Recent studies have indicated that, also as far as the allocation of public funds is concerned, ‘once in, you are pretty much in’ (Suarez Citation2011: 316), meaning that organizations that have a positive record in the use of grants tend to obtain more funds in subsequent application cycles (Crepaz and Hanegraaff Citation2020). Our argument is thus that insiderness exists in the system of government subsidies as it does in the system of interest intermediation. In other words, a group that systematically obtains funding might also systematically be asked to participate in public committees, councils, and commissions. While insiderness is certainly also relevant for low-threshold access (insiders will certainly seek contact with policymakers), we argue that the link between funding and level of insiderness will become visible when policymakers themselves initiate the contact with interest groups. There are several reasons behind this argument.

Policymakers should in theory trust organizations with a positive track record in public funding more, because they associate funding with leadership in the field and the expert position of the organization. In this situation, public funds operate as a ‘seal of approval’, which tells policymakers that they are dealing with a reliable and legitimate organization (Pratt et al. Citation2006).

Consequently, grants are not only beneficial for financial purposes, but are a shortcut for organizations to be known ‘in political circles’ (Suarez Citation2011: 316). Public funding might also indicate that the organization the government is dealing with tends to have a cooperative approach towards state institutions, because funded organizations are less likely to adopt a confrontational strategy (Sanchez Salgado Citation2010). We therefore expect to observe a systematic link between funded organizations and the access that policymakers grant them. These considerations lead us to the following hypothesis:

H2: Interest groups that receive public funding are more likely to gain access to policymakers at the initiative of policymakers compared to unfunded ones.

Research design

For this article we make use of data gathered in the Comparative Interest Group Survey (CIGS).2 More specifically, we focus on four countries (Belgium, the Netherlands, Slovenia, and Italy) and the EU. The project focuses on the organizational characteristics and political activities and strategies of non-profit organizations. The overall response rate to the survey is 38%, which is relatively high compared to other online surveys (Marchetti Citation2015). Moreover, the response rate is quite evenly distributed across countries. More precisely, response rates were as follows, from lowest to highest: Italy (32%); Slovenia (36%); the EU (36%); the Netherlands (38%); and Belgium (41%) (see Supplementary material online appendix 6 for an extensive description of the project, case selection, and sampling strategy). The data provides us with relevant information on national and EU funding and its relationship with access.

This leaves us with a set of four countries, different in size, population, organisation of the economy, and years of democratic establishment. This diversity is representative of the internal heterogeneity of the EU, in which these countries are nested. Belgium and the Netherlands are well-known neo-corporatist systems with generous funding opportunities and a developed and professionalized interest groups system. However, while in Belgium interest groups are embedded in a multi-level and multi-lingual context, the Netherlands is a centralized country. Italy has a very fragmented interest groups system with a large disparity of resources among actors (Wilson 2014). Southern regions are characterised by low levels of associationism and high clientelistic relations. In Central and Northern Italy, regions have established distinct types of state–civil society relationships ranging from neo-corporatism to pluralism. While Slovenia has a quite developed interest group system, it is still far from more professionalised interest groups systems in advanced democracies. Its interest representation is strongly based on elite networks, a limited access to financial and human resources and a strong dependence from the state in their obtainment (Novak and Fink-Hafner Citation2019).

Dependent variables

In this article we rely on two dependent variables that relate to actual contacts between policymakers and interest groups. We explicitly emphasized in this question the amount of actual contacts (gained access), not the attempt to get into contact (sought access). For our analysis, we make a distinction between contacts initiated by interest groups (‘low threshold’), and contacts initiated by policymakers (‘high threshold’). For the first dependent variable, we rely on the following question in the survey: ‘How often in the last year has your organization initiated contact with policymakers?’ Respondents could choose from five categories: never, at least once, at least every three months, at least once a month, or at least once a week. We use the data to construct an estimate of the number of times an organization has been in contact with a policymaker. If an organization indicates to have been in contact with a policymaker once a year, this counts as ‘one’ contact; if they indicate to have been in contact once every three months, this counts as ‘four’ contacts, etcetera. This provides us with a count variable of how often interest groups have been in contact with policymakers at their own initiative, ranging from 0 to 52 contacts over the course of one year.

The second dependent variable concerns access provided by policymakers and to measure this we rely on the following question: ‘How often did policymakers initiate contact with your organization in the last year?’ Respondents could again choose from five categories: never, at least once, at least every three months, at least once a month, or at least once a week. We transform this into count data, in the same way as for the first dependent variable above. In this case, however, the count variable provides us with an indicator of how often interest groups have been in contact with policymakers at the initiative of the latter.

Independent variable

We use only one key independent variable in our analyses. We aim to explain the link between varying types of access and the obtainment of government funding. For this we rely on a question in the survey which indicates whether or not groups had received government funding over the past financial year, and from which government. For national groups we listed all groups that indicated having received national funding as ‘yes’; and all other organizations as ‘no’. For the EU survey we listed all organizations that indicated to have received EU funding as ‘yes’ and all organizations that had not received this type of funding as ‘no’. This way we can link access to national or EU-level institutions to funding at the requisite level. There are several shortcomings coming from dichotomising the key independent variable, the most obvious one being the loss of specificity and detail in the original data if we had considered the size of the obtained funds. However, we do not expect types of access to be linked to the size of the grant in the same way that we expect it to be for the obtainment of funding.3

Given the large scope of the survey, the data do not allow us, unfortunately, to distinguish precisely between different types of funding the governments provide to interest groups. This is an important limitation of the data since the type of funding could affect access in different ways. For example, funding specifically destined to support advocacy activities might encourage high and low threshold access, as opposed to project or core funding. Thus, while interpreting results, it is important to take into account that in political systems, such as the EU, where the funding of advocacy activities is more frequent, the link between access and funding might be stronger. However, we do not to expect this to bias our results excessively, given that project funding is much more common than advocacy funds, at least in European countries (European Commission Citation2001). Still, we provide separate tests for each political system to see whether the EU is an outlier or not (see Supplementary material online appendix 5).

Accounting for alternative explanations: control variables and robustness checks

In order to ensure our results are robust, we control for various alternative explanations which could affect access, including the type of interest group,4 its budget and degree of professionalization, the representational objective of the organization, the competition for resources, and the age of the organization (see for summary statistics; for the specific operationalization of these variables see Supplementary material online appendix 7).

Table 1. Overview of variables used in article.

Previous research has indicated that the type of interest group matters when access is studied, in the sense that citizen groups tend to gain and seek less access than business groups (Dür and Mateo Citation2012, Citation2016). Regarding budget, as general rule, more resources empower an organisation in accessing public institutions (Coen and Katsaitis Citation2013; Eising Citation2007). We control for representation because policymakers might prefer to give access to groups that are embedded in society through direct representation of members (Greenwood Citation2011). We control for competition for resources as more competition could affect the access that groups gain to policymakers (Hanegraaff et al. Citation2016). Finally, we control for the age of an organization, as long-established interest groups might gain more access.

We also conducted a total of five robustness checks to validate our results in light of alternative explanations. The first concerns potential interferences of the level of governance in which funding is supplied. To account for the level of governance, we ran a multilevel model in which the EU is the highest level, followed by the four countries and then the interest groups active in these countries (Supplementary material online appendix 1). The second robustness check concerns an important alternative explanation, namely the attitude of organizations towards the government institution in their jurisdiction5 (Supplementary material online appendix 2). This is a relevant control variable since confrontational organisations are expected to engage less in direct lobbying and are certainly approached less on the policymakers’ initiative. The third robustness check concerns the size of grants (Supplementary material online appendix 3). The fourth robustness check concerns the obvious interaction between the obtainment of funds and the size of an organization’s budget (Supplementary material online appendix 4). Finally, as said, to test the external validity of our argument it is critical we understand how our argument works in different contexts. For this reason we conduct separate analyses per country/EU in Supplementary material online appendix 5. This allows us to assess the generalizability of our results in for the specific cases of our analysis. In addition, this allows us to attempt an interpretation of the results for political systems outside the scope of our analysis.

Results

Before presenting the main findings, we briefly introduce some descriptive data about our dependent and independent variables across jurisdictions. While, a careful consideration of country difference is not the main focus of this study, variation across countries is important in light of the external validity of our argument. In addition, understanding how our dependent and independent variables vary across political systems helps putting our main conclusions into context. For this reason we present some descriptive data on country/EU differences (see below) and provide separate analyses to test our main argument (see Supplementary material online appendix 5).

First, how is funding distributed in the four countries and the EU (see )? The results reveal that the number of interest groups that received government funding depends much on the national context where they are embedded. While in Slovenia (39%) and at the EU level (38%) a significant number of groups received government funding, the number of interest groups that received public funds in Italy is quite low (18%). This confirms existing research according to which Slovenian interest groups depend on the state for their survival (Novak and Fink-Hafner Citation2019). The results in the Netherlands (33%) and Belgium (25%) were also not surprising. Many interest groups in these countries benefit from generous public funding opportunities, but at the same time, individual donors and contributors represent main sources of funding. The absence of alternative sources of funding, other than EU agencies and the Commission, could also explain why the percentage of funded groups is so high at the EU level.

Table 2. Distribution of public funding across countries and EU (in percentages).

Next, we examine how access is distributed across countries. illustrates that both types of access (initiated by the interest group or at the initiative of the policymaker) are frequent (mean = 5.06, and between roughly 2 and 8 meetings per year), but access at the interest group’s initiative is slightly more common (mean = 7.90, and between 3 and 11 meetings per year). Again, there is quite some variation across countries and jurisdictions. At the country level, Slovenian interest groups seem to enjoy substantially lower levels of access than interest groups in other countries. This is in line with existing research according to which Slovenian interest groups have low levels of access (Novak and Fink-Hafner Citation2019). Average levels of access (especially high threshold) appear to be highest in the Netherlands and the EU.

Table 3. Distribution of low and high threshold access gained to policymakers across countries and EU.

In the Dutch case, this might be explained by its developed lobbying sector and its consociative model of policy-making (Vollaard et al. Citation2014). In the case of the EU, higher levels of access are explained by the EU’s openness towards interest groups with the aim of increasing input legitimacy (Greenwood Citation2011).

In our multivariate analyses we include two dependent variables, each highlighting a different type of access (see ). The first type of access measures access gained at the interest group’s initiative (‘low threshold’). The second variable measures access requested by policymakers (‘high threshold’). Both variables contain count data, i.e. the number of times interest groups and policymakers have had contact in a year. To account for the type of data, we rely on a negative binomial regression analysis.6 Our independent variable is whether or not groups have received funding (1 = Yes; 0 = No). We control for group type, resources, professionalization, competition, representation, age of the organization, and country.

Table 4. Negative binomial regressions predicting types of access across four countries and EU.

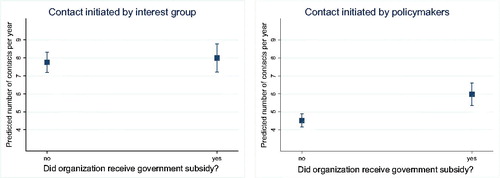

As expected, the relationship between funding opportunities and access depends on the type of access. Public funds do not seem to be associated to access sought by groups (H1), but they have a positive relation with access at the initiative of policymakers (H2). In other words, funding opportunities do not seem to have any particular effect on interest groups’ access strategies, but they seem be correlated with group’s status, that is, when policymakers facilitate access.

More specifically, our first hypothesis stated that public funding does not enhance the contacts between interest groups and policymakers at the initiative of the former. The findings are in line with this hypothesis. This is most clearly indicated by the marginal plots (see , left panel). Funded and unfunded groups in our sample gain successful access to policymakers at their own initiative almost to the same extent (around 8 times a year on average). Moreover, the slight difference we do observe is clearly not significant in statistical terms. The very wide confidence intervals indicate that there is a large degree of variation in access at the initiative of interest groups across both funded and unfunded organisations. This fits with our reasoning, namely that there are reasons both to expect a positive and a negative relationship between seeking access and public funding (Chaves et al. Citation2004; Mosley Citation2012; Smith Citation2003). In other words, there is no systematic linear effect of funding on seeking access to policymakers.

Figure 1. Predictive number of contacts between interest groups across low (left) and high (right) threshold access, and whether or not groups received funding.

Note: The models are based on (contact initiated by interest groups, see Model 1; contact initiated by policymakers, see Model 2).

The second hypothesis stated that public funding is positively correlated to access initiated by public authorities. The results are in line with our expectation (see Model 2, ). This result is particularly interesting if we consider that, in many cases, the institutions or policymakers that invite interest groups to participate in committees and advisory groups are not necessarily the same authorities that are in charge of the management of funding opportunities. This does not rule out endogeneity but allows providing a first interpretation of the causal mechanism that lies between high threshold access and funding. The most reasonable explanation is that receiving public funds confers a certain privileged (partner) status or expert position to the interest groups receiving these funds (as suggested by Suarez Citation2011: 316, see also Pratt et al. Citation2006; Sanchez Salgado Citation2014). In this situation, grants operate as a ‘seal of approval’ that indicates to a government agency that, for example, needs to allocate seats in an advisory council that the funded organizations are experts in their field, are reliable organizations as far as the management of funds is concerned, and are non-confrontational when it comes to dealing with government issues. To look at whether an organization is funded or not might therefore describe one of the possible ways that governments use to ‘ascribe’ status to an organization in the sense used by Maloney et al. (Citation1994).

To grasp the extent to which public funding is positively correlated to this type of access, we plotted the predicted probability of access requests for funded and unfunded groups (see , right panel). Here we see that, all things being equal, policymakers are predicted to reach out to funded groups 25% more often than to unfunded groups. That is, the predicted access at policymakers’ initiative increases from 4.5 contacts a year for unfunded organizations to 6 contacts per year for funded organizations. This is a substantial increase in the number of times policymakers initiate contacts with interest groups and provides strong support for our second hypothesis.

As shown in , the relevant control variables that we identified following existing literature do not compromise the results of our analysis. Moreover, the five robustness checks conducted also reinforce the validity of our results. Appendices 1 and 2 show that the results in the models, taking into account the multilevel dimension and groups’ attitudes towards government, are the same as the results shown in .

The remaining robustness checks, while not compromising our results, reveal further interesting nuances. While the robustness test regarding the size of the grant (Supplementary material online appendix 3) does not alter the validity of our main result, it suggests that the obtainment of funding (affecting only high threshold access) seems to follow a different logic than the size of the grant (affecting both types of access). This might be because large grants strengthen a group’s organizational capacity in a way that it enhances its advocacy activities, regardless of type of access. As a result, it seems that funding supports general access in the same way a large budget supports advocacy. However, it needs to be noted that, despite statistical significance, the size of a grant seems to have a substantially larger effect on high threshold access than on low threshold access.

Finally, we argued that funding is skewed towards more resourceful organizations and, to see whether this affects our results, we added an interaction between resources and funding in Supplementary material online appendix 4. The results highlight that resources function as a catalyst for funded groups to be invited by policymakers. If groups are relatively well-resourced and receive funding, then they have the highest chances to be invited by policymakers. There is no effect for groups getting access at their own initiative.

Overall, the results presented in are consistent within three countries (Belgium, the Netherlands, and Italy) and the EU in Supplementary material online appendix 5. In all these cases, funding does not affect access gained at the initiative of interest groups, but it does significantly increase the likelihood to be invited by policymakers. While the results hold for all four political systems, the finding may be more significant for Italy and the EU, given that being contacted by policymakers is a rare event relative to low threshold access (see gap between low and high threshold access in ). It might thus well be that interest groups in Italy and the EU perceive funding as crucial for their activities, at least more than in Belgium and the Netherlands. More research is however needed to explore to which extent this is the case.

Interestingly our findings do not hold for Slovenia. Funding does not increase access opportunities, irrespective of who takes the initiative. This result suggests that our general finding may not be valid in countries with a less developed interest group system. As already indicated, interest groups in Slovenia operate with very little resources and staff and are reluctant to contact policymakers (Novak and Fink-Hafner Citation2019). More generally, in a country where a high number of organizations are dependent on public funds and where high-threshold contacts are rare, it seems logical to find no correlation between access and funding.

In brief, funds seem to be correlated to high threshold access in many western democracies, with diverse systems of public funding and systems of interest representation. Yet, the extent to which our results hold in other countries with, for example, a statist tradition of both interest representation and funding like France, or in younger democracies with less developed lobbying environments like Poland, is still open to debate. More research is therefore needed to explore the nuances of the mechanisms explored in this article. Whether studies should focus on country differences, differences in the systems of interest representation, or differences in the tradition of public funding supply, is a choice that we leave to future scholars.

Conclusion

In this article we explored whether there is a relation between government subsidies to interest groups and the access these groups gain to policymakers. The current literature does not speak with one voice on this matter. Where some observe a positive relation, others find a negative relation between funding and access (Chaves et al. Citation2004; Mosley Citation2012; Sanchez Salgado Citation2014; Smith Citation2003). In this article we argued that this might be due to the way access has been conceptualised and operationalized. We therefore proposed to make a distinction between two types of access: access gained at the initiative of interest groups (low threshold) and at the initiative of policymakers (high threshold). Our hypotheses stated that funding has a different effect on each type of access. In our analysis, we found solid evidence for our claim.

Our findings indicate that, in western democracies, the attainment of government funding does not seem to affect interest group behaviour as far as organizations seeking access to legislators is concerned, but seems to be associated with the behaviour of policymakers who provide access. We find that policymakers approach funded organizations systematically more often than unfunded ones. However, funded and unfunded organizations do not differ as far as lobbying at their own initiative is concerned.

Our findings are relevant for several literatures. First, and most directly, we contribute to debates on the effect of funding on interest group advocacy strategies and outcomes (Anheier et al. Citation1997; Bloodgood and Tremblay-Boire Citation2017; Leech Citation2006; Sanchez Salgado Citation2010). Our article highlights that funding does relate to the ‘insider status’ of interest groups in western democracies, but finds no link between funding and strategic considerations (Maloney et al. Citation1994). This means that it is erroneous to assume that funding might always discourage advocacy based on the principles of resource dependency and goal displacement. Neither is it obvious that funds will be automatically used by organizations to increase their lobbying efforts. Thus, public funds seem to influence less the autonomy of groups than is usually claimed. While policymakers can normally decide who they wish to meet and listen to, they cannot ensure that funded groups will seek more or less access. Qualitative research might be needed to analyse how and why such control may be exerted in specific instances.

On the contrary, it seems that funding affects a government’s view of interest groups by granting them systematically more access. We interpret this as government institutions using the attainment of funds as an indicator of trust and reliability (Suarez Citation2011). Since the criteria that policymakers use to grant access may be similar to the criteria that they use to grant financial support, obtaining funding could appear, in the eyes of a government, as an informational shortcut to select core insiders. We controlled for several factors which could serve as such shortcuts, such as the resources of a group, the type of organization, the age and level of professionalization, but others may exists. This could include the reputation of an organization or personal traits of interest group representatives (e.g. being a former politician). We cannot test this with the data at hand, so more research is needed to analyse why some groups are perceived as more competent and reliable than others. Still, whatever the exact sources of these shortcuts are, our study shows that some groups simply have a clear advantage towards political institutions: they gain more funding and are also more often invited to talk to policymakers. This is an important finding in and of itself.

Second, we add to the extensive literature on why certain groups gain access to policymakers by adding funding as a new explanatory variable (Binderkrantz et al. Citation2015; Mahoney Citation2004). The literature tends to focus on supply-side factors, such as resources, group type, or the level of professionalization of groups. To these studies, we have added government funding as another relevant factor in understanding patterns of access. Moreover, in this paper we confirm the usefulness of Binderkrantz et al.’s (Citation2017) analytical distinction of different types of access. Our results clearly highlight that the observed type of access drives the results of the study and future studies would benefit from a similar approach.

Despite the important findings presented in this article, we see our study as a starting point. More qualitative evidence needs to be collected to demonstrate how policymakers ascribe insider status to funded organizations. Another possible pathway is to further explore the null finding concerning low threshold access and funding. Our reasoning is that there are contradictory effects which cancel each other out. Yet our data do not allow fleshing out these mechanisms any further. Future studies should follow up on this causal claim. Lastly, we hope this study sparks more attention to the effect of funding on interest group strategies and outcomes. For instance, with a budget of 20 billion euros, the EU has a mighty tool to affect interest mediation, but not much is known about the effects for interest groups. Our results clearly indicate that more attention to this issue is warranted.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (86.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the three anonymous reviewers as well as the editors for their constructive comments and suggestions on earlier versions. The authors are also indebted to all participants in our panel at the 2018 ECPR Standing Group Conference on the EU, specially to the discussant, Carlo Ruzza. All our thanks to the European Research Council (ERC-2013-CoG 616702-iBias, principal investigator Jan Beyers) for its financial contribution. We are also grateful for the financial support of the NWO (Hanegraaff VENI Grant: 451-16-016).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michele Crepaz

Michele Crepaz is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Political Science at Trinity College Dublin. His current research covers topics in transparency research, public policy analysis and interest group politics. His work has appeared in the Journal of European Public Policy, the Journal of Public Policy and Interest Group and Advocacy, while his latest co-authored book on lobbying regulations was released by Manchester University Press. [[email protected]]

Marcel Hanegraaff

Marcel Hanegraaff is an Assistant Professor in Political Science at the University of Amsterdam. He researches the politics of interest representation in a transnational and EU context, as well as on the functioning of international organizations in the fields of climate change and global trade. His work has appeared, among others, in the European Journal of Political Research, Comparative Political Studies, European Union Politics, the Journal of European Public Policy, West European Politics, Party Politics, Governance and the Review of International Organizations. [[email protected]]

Rosa Sanchez Salgado

Rosa Sanchez Salgado is Assistant Professor of European Politics in the Department of Political Science, University of Amsterdam. Much of her previous research has focused on the EU shaping of civil society organizations, including the effects of public funding. More recently, she has also investigated the role of emotions in dynamics of public contestation and social change. She has published articles in the Journal of European Integration, Journal of Common Market Studies, Politics & Governance, and several other journals. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 The core characteristics of such system are, first, that funding needs to be requested through an application system including a call for proposals and a competitive selection process. This differentiates it from state aid which is assigned to, for example firms or farmers, without a competitive call.

2 See https://www.cigsurvey.eu/ for a full description of the project, data, and the methodology for its collection (last accessed February 4th, 2019)

3 We provide a test of the effect using the size of the grant in Supplementary material online appendix 3.

4 We hereby rely on the eight categories stemming from the INTERARENA coding scheme (see Binderkrantz et al. Citation2014; http://interarena.dk/)

5 We decided to exclude this control variable from our main analysis and include it in Supplementary material online appendix 2 because of 300 missing observations. The results are the same.

6 A Pearson Chi2 dispersion test indicated that this model is a better fit than a Poisson model.

References

- Anheier, Helmut K., Stefan Toepler, and Wojciech S. Sokolowski (1997). ‘The Implications of Government Funding for Non-Profit Organizations: Three Propositions’, International Journal of Public Sector Management, 10:3, 190–213.

- Binderkrantz, Anne S., Peter M. Christiansen, and Helene H. Pedersen (2014). ‘Lobbying across Arenas: Interest Group Involvement in the Legislative Process in Denmark’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 39:2, 199–225.

- Binderkrantz, Anne S., Peter M. Christiansen, and Helene H. Pedersen (2015). ‘Interest Group Access to the Bureaucracy, Parliament, and the Media’, Governance, 28:1, 95–112.

- Binderkrantz, Anne S., Helene H. Pedersen, and Jan Beyers (2017). ‘What is Access? A Discussion of the Definition and Measurement of Interest Group Access’, European Political Science, 16:3, 306–21.

- Bloodgood, Elizabeth, and Joannie Tremblay-Boire (2017). ‘Does Government Funding Depoliticize Non-Governmental Organizations? Examining Evidence from Europe’, European Political Science Review, 9:3, 401–24.

- Bourgeois, Geert (2009). Beleidsnota Bestuurszaken 2009–2014. Brussel: Vlaamse Regering.

- Broscheid, Andreas, and David Coen (2003). ‘Insider and Outsider Lobbying of the European Commission: An Informational Model of Forum Politics’, European Union Politics, 4:2, 165–89.

- Chaves, Mark, Laura Stephens, and Joseph J. Galaskiewicz (2004). ‘Does Government Funding Suppress Nonprofits’ Political Activity?’, American Sociological Review, 69:2, 292–316.

- Child, C., and Kristen A. Grönbjerg (2007). ‘Nonprofit Advocacy Organizations’, Social Science Quarterly, 88:1, 259–81.

- Christiansen, Peter M., Asbjørn S. Nørgaard, Hilmer Rommetvedt, Tosten Svensson, Gunnar Thesen, and PerOla Öberg (2010). ‘Varieties of Democracy: Interest Groups and Corporatist Committees in Scandinavian Policy Making’, Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 21:1, 22–40.

- Coen, David, and Alexander Katsaitis (2013). ‘Chameleon Pluralism in the EU: An Empirical Study of the European Commission Interest Group Density and Diversity across Policy Domains’, Journal of European Public Policy, 20:8, 1104–19.

- Crepaz, Michele, and Marcel Hanegraaff (2020). ‘The Funding of Interest Groups in the EU: Are the Rich Getting Richer?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 27:1, 102–21.

- Dür, Andreas, and Gemma Mateo (2012). ‘Who Lobbies the European Union? National Interest Groups in a Multilevel Polity’, Journal of European Public Policy, 19:7, 969–87.

- Dür, Andreas, and Gemma Mateo (2013). ‘Gaining Access or Going Public? Interest Group Strategies in Five European Countries’, European Journal of Political Research, 52:5, 660–86.

- Dür, Andreas, and Gemma Mateo (2016). Insiders versus Outsiders: Interest Group Politics in Multilevel Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Eising, Rainer (2007). ‘Institutional Context, Organizational Resources and Strategic Choices: Explaining Interest Group Access in the European Union’, European Union Politics, 8:3, 329–62.

- Eising, Rainer, and Florian Spohr (2017). ‘The More, the Merrier? Interest Groups and Legislative Change in the Public Hearings of the German Parliamentary Committees’, German Politics, 26:2, 314–33.

- European Commission (2001). European Governance: A White Paper. COM (2001) 428 final, Brussels, 25 July 2001.

- Fraussen, Bert, Jan Beyers, and Tom Donas (2015). ‘The Expanding Core and Varying Degrees of Insiderness: Institutionalised Interest Group Access to Advisory Councils’, Political Studies, 63:3, 569–88.

- Grant, Wyn (2001). ‘Pressure Politics: From ‘Insider’ Politics to Direct Action?’, Parliamentary Affairs, 54:2, 337–48.

- Greenwood, Justin (2007). ‘Organized Civil Society and Democratic Legitimacy in the European Union’, British Journal of Political Science, 37:2, 333–57.

- Greenwood, Justin (2011). Interest Representation in the European Union. London: Macmillan.

- Hanegraaff, Marcel, Jan Beyers, and Iskander De Bruycker (2016). ‘Balancing inside and outside Lobbying: The Political Strategies of Lobbyists at Global Diplomatic Conferences’, European Journal of Political Research, 55:3, 568–88.

- Klüver, Heike, and Sabine Saurugger (2013). ‘Opening the Black Box: The Professionalization of Interest Groups in the European Union’, Interest Groups & Advocacy, 2:2, 185–205.

- Kohler-Koch, Beate, and Berthold Rittberger (2007). Debating the Democratic Legitimacy of the European Union. Plymouth: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Leech, Beth L. (2006). ‘Funding Faction or Buying Silence? Grants, Contracts, and Interest Group Lobbying Behaviour’, Policy Studies Journal, 34:1, 17–35.

- Mahoney, Christine (2004). ‘The Power of Institutions: State and Interest Group Activity in the European Union’, European Union Politics, 5:4, 441–66.

- Mahoney, Christine, and Michael J. Beckstrand (2011). ‘Following the Money: European Union Funding of Civil Society Organizations’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 49:6, 1339–61.

- Maloney, William, Grant Jordan, and Andrew M. McLaughlin (1994). ‘Interest Groups and Public Policy: The Insider/Outsider Model Revisited’, Journal of Public Policy, 14:1, 17–38.

- Marchetti, Kathleen (2015). ‘The Use of Surveys in Interest Group Research’, Interest Groups & Advocacy, 4:3, 272–82.

- Mosley, Jennifer (2012). ‘Keeping the Lights on: How Government Funding Concerns Drive the Advocacy Agendas of Nonprofit Homeless Service Providers’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22:4, 841–66.

- Nikolic, Sara J., and Tomas Koontz (2008). ‘Nonprofit Organizations in Environmental Management: A Comparative Analysis of Government Impacts’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18:3, 441–63.

- Novak, Meta, and Danica Fink-Hafner (2019). ‘Slovenia: Interest Groups Developments in a Postsocialist-Liberal Democracy’, Journal of Public Affairs, 19:2, e1867 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/pa.1867

- Persson, Thomas, and Katsa Edholm (2018). ‘Assessing the Effects of European Union Funding of Civil Society Organizations: Money for Nothing?’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 56:3, 559–75.

- Pratt, Brian, Jerry Adams, and Hannah Warren (2006). Official Agency Funding of Ngos in Seven Countries: Mechanisms, Trends and Implications. INTRAC.

- Roberts, Jonathan (2007). ‘Partners or Instruments: Can the Compact Guard the Independence and Autonomy of Voluntary Organizations?’, Voluntary Sector Working Papers, 8, 40. p.

- Sanchez Salgado, Rosa (2010). ‘NGO Structural Adaptation to Funding Requirements and Prospects for Democracy: The Case of the European Union’, Global Society, 24:4, 507–27.

- Sanchez Salgado, Rosa (2014). ‘Rebalancing EU Interest Representation? Associative Democracy and EU Funding of Civil Society Organizations’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 52:2, 337–53.

- Saurugger, Sabine (2008). ‘Interest Groups and Democracy in the European Union’, West European Politics, 31:6, 1274–91.

- Smith, Steven R. (1999). ‘Government Financing of Nonprofit Activity’, in Elizabeth T. Boris and Eugene C. Steuerle (eds.), Nonprofits and Government. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press, 177–210.

- Smith, Steven R. (2003). ‘Government and Nonprofits in the Modern Age’, Society, 40:4, 36–45.

- Suarez, David F. (2011). ‘Collaboration and Professionalization: The Contours of Public Sector Funding for Nonprofit Organizations’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 21:2, 307–26.

- Trapp, Leila, and Bo Laursen (2017). ‘Inside out: Interests’ Groups ‘Outside’ Media Work as a Means to Manage ‘Inside’ Lobbying Efforts and Relationships with Politicians’, Interest Groups & Advocacy, 6:2, 143–60.

- Vollaard, Hans, Jan Beyer, and Patrick Dumont (2014). European Integration and Consensus Politics in the Low Countries. London: Routledge.