Abstract

Much research is devoted to the relationship between populist parties and democracy. However, relatively little is known about the relationship between citizens’ populist attitudes and democracy. This article examines the relationship between populist attitudes, support for democracy, and political participation (voting, protest, support for referendums, and support for deliberative forms of participation). Using survey data from the Netherlands, this article shows that individuals with stronger populist attitudes are more supportive of democracy, are less likely to protest, are more supportive of referendums, and are more supportive of deliberative forms of political participation compared to individuals with weaker populist attitudes. Results show no relationship between populist attitudes and voting. These findings provide important insights into the relationship between populism, democracy, and political participation from a citizen’s perspective.

Discussions surrounding the crisis of democracy abound, and they have been especially numerous since the economic crisis in 2008.1 The so-called crisis of democracy is often associated with the rise of populist parties. Indeed, as Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser (Citation2017: 79) note ‘it is not far-fetched to suggest that the conventional position is that populism constitutes an intrinsic danger to democracy’. In the literature, it is well established that populist parties routinely want to reform democracy. Populists ‘criticize the poor results of the democratic regime, and, to solve this problem, they campaign for a modification of the democratic procedures’ (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2017: 95, emphasis in the original). Controversy flourishes, however, over what this modification entails. Some scholars argue that populists have an ‘ambivalent’ relation with ‘representative politics’ (Taggart Citation2002) or that the relationship between populism and democracy is ‘parasitical’ (Urbinati Citation2014: 135). The implication is that populism is seen as a threat to democracy. Other scholars are more nuanced, pointing to specific reforms proposed by populists, such as referendums (Mudde Citation2007), while also observing that populism can act as a threat or a corrective for democracy, depending on the context (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2017).

Most studies assess the relationship between populism, democracy, and political participation by focusing on populist parties. However, it is well established that citizens can also possess stronger or weaker populist attitudes (Akkerman et al. Citation2014; Hawkins et al. Citation2012; Spruyt et al. Citation2016; Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel Citation2018). Despite the apparent link between democracy and populism, it is striking that we know little about what citizens with stronger populist attitudes think about democracy and political participation.

This discussion brings us to the central question of this article: what is the relationship between populist attitudes, democracy, and political participation? To answer this question, we address three aspects of democracy and political participation. First, we examine the relationship between populist attitudes and support for democracy. Second, we examine the relationship between populist attitudes and participation. We focus on whether individuals with stronger populist attitudes make their voices heard through voting and protest. Third, we assess the stance of citizens with stronger populist attitudes towards referendums and deliberative forms of participation. We do so by conducting a series of regression analyses on the 2016 Dutch National Referendum Survey. Among others, we find that citizens with stronger populist attitudes are more supportive of democracy and they also favour more people-centred modes of participation such as referendums and, contrary to our expectations, support deliberative forms of participation.

Theoretical framework: populism, democracy, and political participation

Populism and populist attitudes

Three perspectives dominate the literature on populism, namely, populism as a style, populism as a strategy, and populism as a thin-centred ideology (Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007; Moffitt and Tormey Citation2014; Mudde Citation2004; Weyland Citation2001). In this article, we employ populism as a thin-centred ideology, as the two other perspectives are well suited to studying populist parties but not citizens. Treating populism as a set of ideas allows us to measure the degree to which citizens possess stronger or weaker populist attitudes (see Akkerman et al. Citation2014; Hawkins et al. Citation2012). The thin-centred ideological approach points to three core characteristics of populism. First, it is people-centred and anti-elite, focusing on the pure people vis-à-vis the corrupt elite. Second, populism frames the distinction between the pure people and the corrupt elite as antagonistic (i.e. a Manichean division between good and evil). Third, populists proclaim that politics needs to be an expression of the general will (i.e. of the pure people) (Mudde Citation2004). Mudde writes that populism is ‘an ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people’ (Mudde Citation2004: 543, emphasis in the original).

Researchers successfully operationalise this definition and have used it to measure populism within speeches, within parties, and among voters (Akkerman et al. Citation2014; Hawkins Citation2009; Hawkins et al. Citation2012; Meijers and Zaslove Citation2020; Rooduijn and Pauwels Citation2011; Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel Citation2018). In this article, we employ the thin-centred ideological definition to measure populist attitudes among individuals. We know from research that people vote for populist parties for many different reasons, e.g. they may oppose immigration (Norris Citation2005; Van der Brug et al. Citation2000), they may support income equality (Akkerman et al. Citation2017), or they may simply like the leader of the party. Thus, voting for a populist party is, in itself, insufficient to determine if someone has stronger populist attitudes than others. To be sure, populist parties are more likely to attract supporters who possess stronger populist attitudes (Akkerman et al. Citation2014, Citation2017; Geurkink et al. Citation2020; Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel Citation2018), but this does not mean that only individuals with strong populist attitudes support populist parties or that all people with strong populist attitudes vote for populist parties. Interestingly, one study finds that the Dutch Freedom Party and the Dutch Socialist Party also attract voters with stronger elitist attitudes (Akkerman et al. Citation2014). Therefore, we will use populist attitudes to address the relationship between populism, democracy, and political participation from a citizen perspective.

Populist attitudes and democracy: a people-centred approach

Much has been written about the relationship between populism and democracy (Abts and Rummens Citation2007; Canovan Citation1999; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser 2012; Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2012). However, we know little about what individuals with populist attitudes think about democracy. This is for several reasons: first, it has not been possible to directly measure populism among individuals given that, until fairly recently, there was no direct individual-level measure of populism (Akkerman et al. Citation2014; Hawkins et al. Citation2012). Second, and relatedly, there has been limited survey data collected that combines a measure of populist attitudes with attitudes regarding democracy and political participation. As a result, research mainly focuses on conceptual discussions regarding populism and democracy and on the link between populist parties and democracy (i.e. the supply side).

The literature on populism can, however, shed light on the relationship between populist attitudes and democracy. The bulk of the literature on populism and democracy focuses on the impact of populism on democracy. Two perspectives dominate: first, researchers regard populism as a threat to democracy (Abts and Rummens Citation2007; Müller Citation2014; Rummens Citation2017; Urbinati Citation2014). Here, the focus is on the anti-pluralist nature of populism (Müller Citation2014; Rummens Citation2017; Urbinati Citation2014, Citation2017). Second, researchers claim that populism can function as a democratic corrective (Canovan Citation1999; Laclau Citation2005a, Citation2005b). Canovan (Citation1999), for example, focuses on the redemptive nature of populism, arguing that populism seeks to save (or redeem) democracy from the excesses of ‘pragmatic politics’ by returning power to the people.

Despite these disagreements regarding the implications of populism for democracy, there is a broader consensus on the core of populism, and, as such, the populist conception of democracy. There is a general consensus that concepts such as the people, the general will, and sovereignty (of the people) lie at the heart of populism (see Canovan Citation1999, Citation2002; Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2014; Rummens Citation2017). Rovira Kaltwasser argues that the general will ‘plays a major role since it allows for developing a specific notion of politics: given that the people is the sovereign, nothing should constrain its will’ (Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2014: 479). At its core, populism is about political representation; political representation based upon the exclusive rule and sovereignty of the people.

Extending this discussion to populists’ perceptions of democracy, Canovan highlights that ‘Populists see themselves as true democrats, voicing popular grievances and opinions systematically ignored by governments, mainstream parties and the media’ (Canovan Citation1999: 2). Populists, as such, consider themselves to be the basis of a democratic corrective to a political system that is perceived to be out of balance (Canovan Citation1999; Mény and Surel Citation2002; Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2012). At the individual level, we can therefore expect citizens with stronger populist attitudes to internalise the democratic self-perception of populism, the idea that populism serves as a democratic corrective, and most importantly that political representation is based exclusively upon the sovereignty of the people and on the general will. After all, it is through democracy that the sovereignty of the people and the general will can be enacted. As such, we expect individuals with stronger populist attitudes to be more supportive of democracy than individuals with weaker populist attitudes.

H1: Individuals with stronger populist attitudes are more likely to support democracy than individuals with weaker populist attitudes.

Populist attitudes and political participation

Thus far, we have discussed the relationship between populist attitudes and democracy: we expect that individuals with stronger populist attitudes will be more supportive of democracy. However, populists are also frustrated with the current state of democracy. Populists are critical of intermediary institutions, judges, bureaucrats, and political parties, leading them to question the quality of real, existing democracy (Canovan Citation2002: 33; Kitschelt Citation2002: 179; Mair Citation2002). Empirically, researchers have consistently shown that those who vote for populist parties are more likely to be dissatisfied with how democracy works (Oesch Citation2008; Ramiro Citation2016; Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel Citation2018).

What are the implications of this combination of support for democracy and dissatisfaction with the current state of democracy for political participation? Are individuals with stronger populist attitudes more likely to participate in politics? Are they more supportive of some forms of political participation? We focus on four prominent types of political participation: voting, protest, support for referendums, and support for deliberative democracy.

Voting

Expectations differ regarding the relationship between populism and voting. Much of the theoretical literature on populism does not directly deal with voting, but rather with political participation more generally (Taggart Citation2002; Urbinati Citation2014). One highly relevant theoretical insight from this literature is that populists have an uncomfortable relationship with political parties. Indeed, populists often oppose political parties (Mair Citation2002; Mény and Surel Citation2002). Mair (Citation2002: 89) even argues that populism ‘tends towards partyless democracy’. From this perspective, populism should be detrimental to voting, discouraging voter turnout. Others, on the other hand, contend that populism can facilitate political inclusion (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2017), populist parties can enhance the clarity of issues and emphasise previously ignored issues (Leininger and Meijers, Citation2020), encouraging individuals to vote (Huber and Ruth Citation2017; Immerzeel and Pickup Citation2015).

Empirical research demonstrates that, within the European context, the presence of populist radical right parties does not substantially increases voter turnout (Huber and Ruth Citation2017; Immerzeel and Pickup Citation2015; Schwander et al. Citation2020). Houle and Kenny (Citation2018) similarly conclude that populism does not increase voting in Latin America. These studies, however, focus on aggregated levels of voting or voting for populist parties (not populist attitudes). Anduiza et al. (Citation2019), on the other hand, focus on populist attitudes, investigating whether individuals with stronger populist attitudes (independent of vote choice) are more likely to vote. They find no general positive relationship between populist attitudes and voting; in countries in which they do find a significant relationship, those with stronger populist attitudes are less likely to vote (i.e. Germany, Poland, and Switzerland) (Anduiza et al. Citation2019).

The core of our argument is that even though individuals with stronger populist attitudes are pro-democratic, they are dissatisfied with the current state of democracy. In particular populists are frustrated with party politics (cf. Kitschelt Citation2002; Mair Citation2002; Mény and Surel Citation2002). Frustrations with the current state of democratic politics, in combination with frustrations with party politics, should have negative implications for voting. As such, we expect individuals with stronger populist attitudes to be less likely to vote. It is possible that the supply side has a moderating effect on whether an individual will vote or not. The presence of a populist party may make an individual less antagonistic towards elections compared to individuals in a country lacking a populist party. The presence of a populist party may stimulate individuals with stronger populist attitudes to vote.

However, given their general frustrations with the current state of politics (and in particular with party politics), in the end, we still expect that individuals with stronger populist attitudes will be less likely to vote compared to individuals with weaker populist attitudes. This leads to the following hypothesis.

H2: Individuals with stronger populist attitudes are less likely to vote than individuals with weaker populist attitudes.

Protest

Next to voting, there are other ways in which individuals can participate in politics. Protesting and demonstrating often occur outside the realm of party politics. Given the opposition of populism towards political parties this might be a way for individuals with stronger populist attitudes to participate politically. There are a number of empirical examples of protest movements from the left and the right that are often classified as populist (i.e. the Indignados in Spain, Occupy Wall Street, the Yellow Vests in France, and Pegida in Germany) (for a good discussion of populism and social movements, see Aslanidis Citation2017).

Limited theory exists regarding populism and protest, however. Hutter and Kriesi (Citation2013) argue that right-wing populists protest less given that they equate protests with ‘chaotic’ behaviour (associated with left-wing politics) or with right-wing extremist movements. Although Hutter and Kriesi (Citation2013) shed light on why right-wing populists may not protest, emphasis is placed on the attaching ideology and not on populism per se. To better understand the link between populist attitudes and protest, we therefore combine the literature on populism with the literature on social movements and protest politics. Populism favours direct and unmediated political participation (Mudde Citation2007; Müller Citation2014; Rummens Citation2017; Taggart Citation2002; Urbinati Citation2017). As such, this populist perspective of political participation clashes with protest politics, and with the literature on social movements more broadly speaking. This literature on social movements and protest focuses on concepts such as collective action, networks, consensus mobilisation, and deliberation (Della Porta Citation2009a, Citation2009b; Della Porta and Diani Citation2020; Della Porta and Doerr Citation2018; Diani Citation2004; Diani and Mische Citation2015; Klandermans Citation2008), again standing in opposition to the populist preference for direct and unmediated participation.

In general, we anticipate that individuals with stronger populist attitudes will be less likely to protest than individuals with weaker populist attitudes. To be clear, we do not exclude the possibility that in the case of a political crisis (e.g. the recent European asylum crisis) or in the case of extensive political upheaval, that the anti-elite stance of individuals with stronger populist attitudes may lead to social protest. Yet, in general, we expect that those with stronger populist attitudes will oppose the more pluralist orientation of protest politics, and, as a result, they will be less likely to participate in protests or demonstrations than individuals who have weaker populist attitudes (independent of their right- or left-wing ideology). We thus hypothesise the following:

H3: Individuals with stronger populist attitudes are less likely to protest or demonstrate than individuals with weaker populist attitudes.

Support for referendums

A large body of research points to growing pressure for democratic reforms and for more direct and participatory forms of political participation (Cain et al. 2003). Referendums are a prominent component of these calls for democratic reform (Scarrow Citation2003). The question is whether individuals who are more populist are also more inclined to favour referendums than individuals who are less populist.

A defining feature of populism is a belief in the pure people, who are typically characterised as homogenous (Mudde Citation2004; Müller Citation2014; Rummens Citation2017). Within the literature on populism, there is discussion regarding the nature of the people. It is often more difficult to define who the pure people are than who they are not. The notion of the people functions as an empty signifier (Laclau Citation2005a) to be filled in by the subjects.2 Different populist movements define the people in different terms, with some definitions identifying the people as more homogenous and pure than other definitions (Kioupkiolis Citation2016; Stavrakakis and Katsambekis Citation2014).

However, a common element that unifies all populist movements is the idea that the pure people represent a unified whole. It is argued that the people can (and should) be represented in their entirety with as little differentiation as possible (Canovan Citation2005; Müller Citation2014). Based on this notion of the pure people, we expect individuals with stronger populist attitudes to be more supportive of referendums compared to individuals with weaker populist attitudes. After all, referendums are precisely the tools by which the voice of the people can be directly represented. They cater to a homogenous notion of the people and allow citizens to rally against the elites (see also Mudde Citation2007), which is something that appeals less to individuals who have relatively weaker populist attitudes, and a more plural notion of the people.3 As Jacobs et al. (Citation2018a: 520) put it: ‘Referendums fit with each of the three key aspects of populism: they are people centered, reduce the power of the elite and are a means to keep the corrupt elite in check (at least to some extent)’. Therefore, we expect the following:

H4: Individuals with stronger populist attitudes are more likely to support referendums than individuals with weaker populist attitudes.

Support for deliberative forms of participation

Recent research on democratic reform also focuses on deliberative forms of democracy, such as citizen juries, town hall meetings, and citizens’ assemblies (Ansell and Gingrich Citation2003; Curato et al. Citation2017; Elstub et al. Citation2016). Deliberative forms of democracy can be understood as an alternative to existing forms of democratic participation. Moreover, they can be seen as the ultimate form of people participation. It can be argued that deliberative bodies represent pure democracy emanating from the people. In their purest form, they relate to what Lucardie (Citation2014) labels democratic extremism, i.e. the unbridled and unmediated rule of the people.

However, it can also be argued that deliberative bodies represent a more plural form of political participation (Bächtiger et al. Citation2018; Brown Citation2018) than what is envisioned by populists (see Müller Citation2014; Niemeyer and Jennstål Citation2018; Rummens Citation2017; Urbinati Citation2014). Research on deliberative democracy focuses on the importance of inclusion and consensus (Bächtiger et al. Citation2018), while other scholars even view deliberation as a means by which to counter the ‘non-deliberative strategies’ of populism (Niemeyer and Jennstål Citation2018: 330). In contrast to deliberative forms of participation, populism is wary of compromise, given that populism dismisses the idea that there may be differing views on the ‘common good’ (Müller Citation2014: 487). Consistent with this argument, we expect that people with stronger populist attitudes are less likely to be supportive of deliberative forms of participation than people with weaker populist attitudes. Accordingly, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H5: Individuals with stronger populist attitudes are less likely to support deliberative forms of participation than individuals with weaker populist attitudes.

provides an overview of our hypotheses. In short, we expect individuals with stronger populist attitudes to be (1) more supportive of democracy, (2) less likely to vote, (3) less likely to protest, (4) more supportive of referendums, and (5) less supportive of deliberative forms of participation compared to individuals with weaker populist attitudes.

Table 1. Overview of hypotheses.

Methodology

Case selection

We tested our expectations on survey data from the Netherlands. The Netherlands is a suitable case for several reasons. First, populism has played an important role in Dutch politics for some time now, i.e. since the rise of Pim Fortuyn in the early 2000s. Research has demonstrated that populist attitudes are present, but not at an unusually high level (Akkerman et al. Citation2014). Second, the Netherlands has both a left- and a right-wing populist party (Akkerman et al. Citation2014, Citation2017; Lucardie and Voerman Citation2012; Otjes and Louwerse Citation2015). At the time of the survey the Dutch political landscape housed two populist parties: the populist radical right Party for Freedom (PVV), led by Geert Wilders, and the left-wing populist Socialist Party (SP). The former was virtually the biggest party in the polls (31–35 seats), while the latter was tied in third position (15–19 seats) (Peilingwijzer 2016). Third, the Netherlands has not suffered any unusual external shocks (Geurkink et al. Citation2020). Thus, the Netherlands was not hit exceptionally hard by the 2008 economic crisis or by the European asylum crisis, which may lead to unusually high levels of dissatisfaction or protest. Fourth, there are sufficient opportunities for citizens to participate in referendums and in deliberative forms of political participation (Jacobs et al. Citation2016; Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Schaap et al. Citation2019). Finally, social protests are not considered to be exceptionally high, such as in France. In sum, populist attitudes and populist parties are present; however, at the same time, it is not possible to speak of a democratic, political, or economic crisis. These conditions allow us to more readily generalise our findings to other countries than would be possible from cases that have recently experienced a profound economic or political crisis.

Data

In this article, we use data from the LISS (Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences) panel administered by CentERdata (Tilburg University, The Netherlands).4 The LISS-panel conducts several standard waves to link standardised questions on political values and background variables to specialised surveys about different topics. We use the April 2016 National Referendum Survey (NRO survey) (LISS-Data Citation2016a) and combine this survey with data from two other waves. One includes information on protest behaviour, satisfaction with democracy, and individuals’ left–right placement (politics and values survey) collected at the end of 2016 (LISS-Data Citation2016b)5 and one wave that covers background characteristics (i.e. education, age, and gender) collected in April 2016 (LISS-Data Citation2016c). The median duration of the survey was 14 minutes for the NRO survey and 17 minutes for the politics and values survey. The background characteristics are asked when individuals join the panel, after which they are presented with this information every month and instructed to enter any changes. The respondents were paid (€4.50) for completing the NRO questionnaire, which was conducted from 7 to 26 April 2016 and started directly after the Dutch referendum on a Dutch law that approved the association agreement between the EU and Ukraine, with a response rate of 87.1%. While the timing of the survey is unlikely to have impacted our findings regarding, for instance, protest, it may have made referendums more salient to our respondents. Future research using surveys fielded at different moments in time is therefore useful.

After excluding the people who did not participate in all three surveys and did not have a valid response to the populist attitudes items, 1,896 participants remained in the dataset. After excluding the respondents who did not have a valid response on one of the other variables of interest, the number of cases in our models ranges between 1,393 (for voting) and 1,712 (for protest).6 Of these remaining respondents, 51.1% were males. The mean age of the respondents was 55 years. The mean gross household income was €52,997, and 36.0% of the respondents had some form of higher education. The data from the national population register in 2016 (CBS 2016) show that in April 2016, 49.6% of the Dutch citizens were male, and 29.2% held a higher education degree. Furthermore, the mean age was 51 years (excluding individuals under 18 years), and the mean gross household income was €59,000. This comparison indicates that respondents of our final sample were on average slightly older, men were a little overrepresented, respondents were more often highly educated, and they had lower incomes than the Dutch population.

Measures

Independent variable: populist attitudes

As previously indicated, we use populist attitudes as the main independent variable. For the measurement of the populist attitudes of the respondents, we rely on the populist attitudes scale as constructed by Akkerman et al. (Citation2014). By using this scale, the three defining elements of Mudde’s (Citation2004) definition of populism are captured, namely, the distinction between the pure people and the corrupt elite, an antagonistic relationship between the pure people and the corrupt elite, and the idea that populists represent the general will. shows the items that are combined to measure populist attitudes. For each of these statements, the respondents were asked to indicate their agreement with the statement on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 represents ‘disagree completely’ and 5 ‘completely agree’. With a principal axis factor analysis, we derive the latent variable of populist attitudes. The analysis indicated a one-factor structure with an eigenvalue of 3.01 of the first factor and factor loadings for all items above 0.6.

Table 2. Items that measure populist attitudes.

Dependent variables

The first dependent variable that is used in this article is support for democracy. For this variable, we combined the following two statements about how people valued democracy: ‘Democracy is the best political system’ and ‘It is important that a country is governed based on democratic principles’. The respondents were asked to respond to these statements on a scale that ranged from 1 (disagree completely) to 5 (agree completely). The correlation between the items was 0.74. We used the mean of these two items.

For the vote variable, we used the question ‘If general elections were held today, what party would you vote for?’ and recoded it into a dummy variable in which ‘0’ is ‘I wouldn’t vote’ and ‘1’ indicates that the respondent would vote.7

Protest is measured by a question regarding whether participants raised a political issue or attempted to influence politicians or government through participation ‘in a protest action, protest march or demonstration’, with ‘1’ being yes and ‘0’ being no.

For the variable support for referendums, the respondents were asked to indicate, on a scale that ranged from 1 (disagree completely) to 5 (agree completely), the extent to which they agreed with the following statement: ‘Some of the decisions that are important for our country need to be voted on directly by the electorate by means of a referendum’.8

Support for deliberative forms of participation was measured by asking for a response to ‘If I had the opportunity to participate in a meeting where citizens discuss important issues regarding the community and/or local politics, then I would certainly do so’. The respondents were asked to respond to this statement on a scale that ranged from 1 (disagree completely) to 5 (agree completely). This statement taps into the respondents’ general support for deliberative forms of participation and is consistent with other national election surveys.9

Control variables

In all our analyses, we added several control variables. We controlled for satisfaction with democracy, asking: ‘How satisfied are you with the way democracy works in the Netherlands?’, with answers ranging from ‘very dissatisfied’ (0) to ‘very satisfied’ (10). Additionally, we controlled for political trust, which is an averaged score of individuals’ trust in Dutch parliament and Dutch government with answers ranging from ‘no trust at all’ (0) to ‘full trust’ (10). The correlation between the two items was 0.93. We controlled for education: middle education (‘higher secondary education’ or ‘intermediate vocational education’) and higher education (‘higher vocational education’ or ‘university’) with lower education (‘primary school’ or ‘intermediate secondary education’) as a reference category. Additionally, we controlled for age, gender, and individuals’ left–right self-placement ranging from ‘left’ (0) to ‘right’ (10).10 In , the descriptive statistics of the variables of interest are presented.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics.

Results

Populist attitudes and democracy

The first model in tests the degree to which individuals who have stronger populist attitudes are more or less supportive of democracy. This model includes satisfaction with democracy, trust, education, age, gender, and left–right orientation as control variables. We expect that individuals with stronger populist attitudes are more supportive of democracy compared to individuals with weaker populist attitudes. The model demonstrates that there is indeed a positive relationship between populist attitudes and support for democracy. Turning to the control variables, we find that individuals with higher levels of satisfaction with democracy, higher levels of political trust, and higher levels of education as well as those who are older are more supportive of democracy. The size of the observed relationship between populist attitudes and support for democracy indicates that an increase of one unit in populist attitudes results in 0.04 more support for democracy. Although this can be considered a relatively small effect, we find support for hypothesis 1: Individuals with stronger populist attitudes are more likely to support democracy than individuals with weaker populist attitudes.

Table 4. Relationship between populist attitudes and variables of interest.

Populist attitudes and political participation

In the second model (see ), we test whether individuals with stronger populist attitudes are less likely to vote (H2). In this model, our dependent variable is a binomial variable for which we performed a logistic regression. We test the effect of populist attitudes on voting, and we control for satisfaction with democracy, political trust, background characteristics, and left–right ideology. The results indicate that there is a negative relationship, but that this is effect is not significant.1112 If we turn to the control variables, we find that individuals with higher levels of trust, individuals who are older, and women (compared to men) are more likely to vote. Therefore, we do not find support for the hypothesis that individuals with stronger populist attitudes are less likely to vote compared to individuals with weaker populist attitudes.

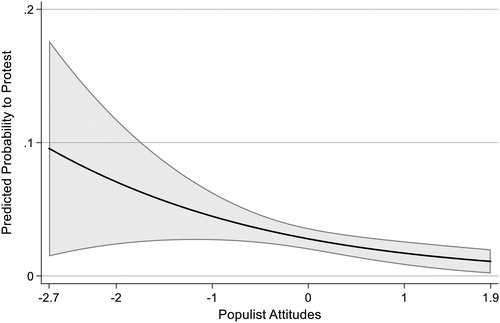

We now turn to our hypotheses regarding the likelihood of individuals to protest or demonstrate (H3). The dependent variable – raising a political issue or attempting to influence politicians or the government through participation in a protest action, protest march, or demonstration – is a binomial variable, and we thus perform a logistic regression (Model 3, ). We examine the extent to which individuals with stronger populist attitudes are more likely to engage in protests or demonstrations. We find a statistically significant negative effect indicating that higher scores on the populist attitude scale are associated with lower participation in protests, marches, or demonstrations. The marginal effects plot () represents the predicted probability to protest for different levels of populist attitudes. The plot indicates that stronger populist attitudes result in a substantively lower probability of engaging in protests or demonstrations. We conclude that we do find support for hypothesis 3: individuals with stronger populist attitudes are less likely to protest or demonstrate than individuals with weaker populist attitudes.

Figure 1. Predicted probability to protest for different levels of populist attitudes with 95% confidence intervals.

The fourth model tests the extent to which individuals who have stronger populist attitudes are more supportive of referendums (H4) (see Model 4, ). Results show a statistically significant and positive effect of populist attitudes on support for referendums. Age is the only other variable that is statistically significant; individuals who are younger are more supportive of referendums. With regard to the size of the effects, we find that a one-unit increase in the populist attitudes scale results in being 0.75 more supportive of referendums (measured on a five-point scale), which we consider a strong effect. These results support hypothesis 4.

The fifth and final model (Model 5, ) tests the extent to which populist attitudes relate to support for deliberative forms of participation. We find a positive and statistically significant effect of populist attitudes on the inclination to participate in deliberative forms of participation. Therefore, we find no support for hypothesis 5. Contrary to our expectations, we find that individuals who are more populist are more inclined to support deliberative forms of participation. Additionally, we find that more highly educated individuals, males, older people, and left-wing individuals are more likely to support deliberative forms of participation. The results show a moderate to small effect; a one unit increase on populist attitudes results in being 0.20 more supportive of deliberative forms of participation (on a five-point scale).

Discussion and conclusions

In this article, we examine the relationship between populist attitudes, democracy and political participation. Our first expectation was that individuals with stronger populist attitudes are more supportive of democracy than individuals with weaker populist attitudes. We find a weak but positive relationship between populist attitudes and support for democracy. Thereby, this article provides an important first step in identifying the relationship between populism and democracy on the individual level. However, some questions remain unanswered and require further study. For example, what do individuals with stronger populist attitudes think about the substantive dimensions of democracy, in particular the tension between the sovereignty of the people and the rule of law? The question is whether, as Mudde (Citation2007: 156–7) notes, the ‘monism’ of populism clashes with the inherent ‘pluralism’ in a liberal democracy. In sum, however, and in line with the supply-side literature, our findings support the idea that populism (among individuals) is not anti-democratic per se; individuals with stronger populist attitudes are even more supportive of democracy.

In addition, the article examines the relationship between populist attitudes and political participation. We find no statistically significant relationship between populist attitudes and voting: individuals with stronger populist attitudes are not less likely to vote. Other studies show that there is no relationship in some countries, while in others populist attitudes and voting are often negatively related (e.g. Anduiza et al. Citation2019). That we find no effect might be due to the availability of populist parties in the Netherlands, with left- and right-wing populist parties. Further research could investigate the relationship between individuals’ propensity to vote and the supply of populist parties. It might be that in countries in which populist parties are absent, on either the left or the right (or both), that a negative relationship between populist attitudes and voting exists. In case of an electorally successful populist party on one side of the political spectrum (e.g. the left), we expect the relationship to be negative for voters with populist attitudes on the other side of the political spectrum (e.g. the right). Additionally, this might be dependent on the degree to which these parties are populist (see Meijers and Zaslove Citation2020).

With regard to protest, we find that individuals with stronger populist attitudes are less likely to protest. These findings suggest, in line with our hypothesis, that the inherent pluralism of protest politics may clash with the anti-pluralism of populism. It is, however, possible that the low level of protest in the Netherlands in general may discourage individuals with stronger populist attitudes from protesting, i.e. there may be a higher stigma in the Netherlands against protesting than there is in other countries, such as France. We therefore encourage researchers to test the findings on the relation between populist attitudes and political participation in other contexts.

Consistent with other studies, we find that individuals who have higher scores on the populist attitude scale also demonstrate stronger support for referendums (Jacobs et al. Citation2018a; Pauwels Citation2014). Surprisingly, we find that people who hold stronger populist attitudes are also more supportive of deliberative forms of participation. Although we expected the positive relationship between populist attitudes and referendums, we did not expect this for deliberative forms of participation. It might be that this support represents intrinsic support for this type of political participation. However, it might also be that it is simply a case of the ‘grass is greener’: any alternative to the current system may be preferred over the status quo. Furthermore, we measured support for deliberative forms of participation at the local level. It is possible that individuals with stronger populist attitudes may feel more affinity for politicians and issues at the local level. Issues may be less ideologically charged and less conflictual at the local level. However, if we take our findings at face value, it appears that individuals with stronger populist attitudes are in favour of more direct (i.e. referendums) and more deliberative forms of political participation.

This article highlights the complex relationship between populist attitudes, democracy, and participation. Although research often views populism as an expression of anti-establishment sentiments (Barr Citation2009), other research demonstrates the degree to which populism is more than political discontent (Geurkink et al. Citation2019). Individuals with stronger populist attitudes also express their support for something, i.e. for people-centred politics (Akkerman et al. Citation2017; Geurkink et al. Citation2020; Spruyt et al. Citation2016). Relating this to democracy and political participation, this article shows that individuals with stronger populist attitudes are pro-democratic, while they are supportive of highly people-centred notions of political participation (i.e. referendums and deliberative forms of participation). What this entails for liberal democracy, and more specifically the liberal dimension of liberal democracy, requires further research (Mény and Surel Citation2002). For example, we need to know more about what individuals with stronger populist attitudes think about individual and minority rights and the separation of powers between the judiciary and the parliament.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (48.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of West European Politics for their constructive comments. Furthermore, we are grateful to Reinhard Heinisch, Sarah de Lange, Alex Lehr, Martin Rosema, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser for their feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from CentERdata. Data are available at https://www.lissdata.nl with the permission of CentERdata. A do-file containing detailed information on the reproduction of the findings presented in this study using Stata can be found in the online appendix.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andrej Zaslove

Andrej Zaslove is Associate Professor at the Department of Political Science, Institute for Management Research, Radboud University. His research interests include populism and political parties, with a particular interest in measuring populism (supply and demand), voting for populist parties, democracy and populism, gender and populism, and foreign policy and populism. He has recently published in Comparative Political Studies, Political Studies, and the European Political Science Review. [[email protected]]

Bram Geurkink

Bram Geurkink is a PhD candidate at the Department of Economics, Institute for Management Research, Radboud University. His research interests include political behaviour, political socialization, workplace voice, and populism. He has recently published in Political Studies. [[email protected]]

Kristof Jacobs

Kristof Jacobs is Associate Professor at the Department of Political Science, Institute for Management Research, Radboud University. His research interests include democratic challenges and innovations, populism, democracy, and social media. He has recently published in European Journal of Political Research, Political Studies, and New Media & Society. [[email protected]]

Agnes Akkerman

Agnes Akkerman is Professor of Labour Market Institutions and Labour Relations at the Department of Economics, Institute for Management Research, Radboud University. Her research interests include industrial conflict, co-determination, and worker participation and voice; protest mobilization and repression. She has recently published her interdisciplinary research in the American Journal of Sociology, Political Psychology, Socio Economic Review, and Comparative Political Studies. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 For example, see Kriesi (Citation2018). For the Dutch discussion, see Van der Meer (Citation2017) and Thomassen et al. (Citation2014).

2 For a good discussion on populism and the people, see Canovan (Citation2005).

3 Clearly, some types of referendums are more consistent with this reasoning than other types. In particular, binding, bottom-up referendums are consistent with the populist ideology. However, referendums always offer at least some opportunity for citizens to go against the elites in an unmediated way, and the 2016 Brexit referendum, a top-down non-binding referendum, is a good example.

4 The LISS panel is a representative sample of Dutch individuals who participate in monthly internet surveys. The panel is based on a true probability sample of households drawn from the population register. Households that could not otherwise participate are provided with a computer and internet connection. A longitudinal survey is fielded in the panel every year, covering a large variety of domains including work, education, income, housing, time use, political views, values, and personality.

5 For these variables we used the first measurement after April 2016 since it includes one of our dependent variables. As a robustness check, we performed the same analyses using the latest available measurement before April 2016. We do not come to different conclusions with regard to our hypotheses.

6 Most of our missing values are due to ‘no opinion’ on at least one of our variables of interest. We ran additional robustness analyses treating the ‘no opinion’ as middle categories on our variables of interest (e.g. neither agree nor disagree). We do not come to different conclusions with regard to our hypotheses.

7 Note that we had a relatively high percentage of individuals indicating that they would vote. This is because we included votes for all parties, blank ballots and invalid ballots, under the category ‘would vote’. Only those who specifically indicated that they would not vote were treated as ‘would not vote’. Furthermore, many individuals (about 20%) indicated that they were unsure and were therefore treated as missing. Additional analysis treating those who were unsure as non-voters did not yield different results with regard to the effect of populist attitudes on voting.

8 The Netherlands had two national referendums in the last 15 years and several local referendums. In 2015, a law that allows for bottom-up, non-binding referendums to repeal legislation was introduced.

9 Another possible question that addresses the support for deliberative forms of participation is whether people actually participate ‘in a government-organised public hearing, discussion or citizens participation meeting’. However, this question was not included in this variable for two reasons. First, the two questions did not show internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.138). Second, in deciding which of the two questions we would include, we argue that the question we use is a more valid measurement of the extent to which people support deliberative forms of participation. After all, the alternative question mainly measures the actual participation in the deliberative process, not the respondents’ preference for such an instrument.

10 Collinearity diagnostics were conducted for all models. No evidence of problems with multicollinearity was detected in any of the models.

11 In order to get more insight in the relationship between populist attitudes and voting, we also ran a multinomial regression analysis separating those who indicated that they would vote (73.4%), those who indicate that they would not vote (4.5%), and those who did not know (22.1%). No significant effects for populist attitudes were found (available upon request).

12 We also tested the effect for actual voting behaviour in the 2017 general election, about one year after the measurement of populist attitudes for this wave (note that the samples do not overlap completely). Here, we find that individuals with stronger populist attitudes are significantly less likely to vote compared to individuals with weaker populist attitudes. This might represent the difference between vote intention and actual behaviour. This might also show that, of those individuals who have not yet decided whether they will vote, those with stronger populist attitudes choose not to vote. Additional research is necessary to provide more insight into this relationship.

References

- Abts, Koen, and Stefan Rummens (2007). ‘Populism versus Democracy’, Political Studies, 55:2, 405–24.

- Akkerman, Agnes, Cas Mudde, and Andrej Zaslove (2014). ‘How Populist Are the People? Measuring Populist Attitudes in Voters’, Comparative Political Studies, 47:9, 1324–53.

- Akkerman, Agnes, Andrej Zaslove, and Bram Spruyt (2017). ‘We the People’ or ‘We the Peoples’? A Comparison of Support for the Populist Radical Right and Populist Radical Left in The Netherlands’, Swiss Political Science Review, 23:4, 377–403.

- Anduiza, Eva, Marc Guinjoan, and Guillem Rico (2019). ‘Populism, Participation, and Political Equality’, European Political Science Review, 11:1, 109–24.

- Ansell, Christopher, and Jane Gingrich (2003). ‘Reforming the Administrative State’, in Bruce Cain, Russell J. Dalton, and Susan Scarrow (eds.), Democracy Transformed: Expanding Political Opportunities in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 164–191.

- Aslanidis, Paris (2017). ‘Populism and Social Movements’, in Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul Taggart, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Pierre Ostiguy (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Populism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 305–325.

- Bächtiger, André, John S. Dryzek, Jane Mansbridge, and Mark E. Warren (2018). ‘Deliberative Democracy: An Introduction’, in André Bächtiger, John S. Dryzek, Jane Mansbridge, and Mark E. Warren (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 35–54.

- Barr, Robert R. (2009). ‘Populists, Outsiders and Anti-Establishment Politics’, Party Politics, 15:1, 29–48.

- Brown, Mark B. (2018). ‘Deliberation and Representation’, in André Bächtiger, John S. Dryzek, Jane Mansbridge, and Mark E. Warren (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 171–186.

- Cain, Bruce E., and Russel Dalton and Susan Scarrow, eds. (2003). Democracy Transformed? Expanding Political Opportunities in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Canovan, Margaret (1999). ‘Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy’, Political Studies, 47:1, 2–16.

- Canovan, Margaret (2002). ‘Taking Politics to the People: Populism as the Ideology of Democracy’, in Yves Mény and Yves Surel (eds.), Democracies and the Populist Challenge. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 25–44.

- Canovan, Margaret (2005). The People. Cambridge: Polity.

- CBS (2016). Statline, available at http://statline.cbs.nl/Statweb (accessed 12 August 2017).

- Curato, Nicole, John S. Dryzek, Selen A. Ercan, Carolyn M. Hendriks, and Simon Niemeyer (2017). ‘Twelve Key Findings in Deliberative Democracy Research’, Daedalus, 146:3, 28–38.

- Della Porta, Donatella, ed. (2009a). Democracy in Social Movements. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Della Porta, Donatella, ed. (2009b). Another Europe: Conceptions and Practices of Democracy in the European Social Forums. London: Routledge, 3–25.

- Della Porta, Donatella, and Mario Diani (2020). Social Movements: An Introduction. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons.

- Della Porta, Donatella, and Nicole Doerr (2018). ‘Deliberation in Protests and Social Movements’, in André Bächtiger, John S. Dryzek, Jane Mansbridge, and Mark E. Warren (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 392–406.

- Diani, Mario (2004). ‘Networks and Participation’, in David A. Snow, Sarah A. Soule, and Hanspeter Kriesi (eds.), The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 339–359.

- Diani, Mario, and Ann Mische (2015). ‘Network Approaches and Social Movements’, in Donatella della Porta, and Mario Diani (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Social Movements. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 306–325.

- Elstub, Stephen, Selen Ercan, and Ricardo F. Mendonça (2016). ‘Editorial Introduction: The Fourth Generation of Deliberative Democracy’, Critical Policy Studies, 10:2, 139–51.

- Geurkink, Bram, Andrej Zaslove, Roderick Sluiter, and Kristof Jacobs (2019). ‘Is Populism About More Than Discontent?’, LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) Blog, available at https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2019/08/21/is-populism-about-more-than-discontent/ (accessed 4 may 2020).

- Geurkink, Bram, Andrej Zaslove, Roderick Sluiter, and Kristof Jacobs (2020). ‘Populist Attitudes, Political Trust, and External Political Efficacy: Old Wine in New Bottles?’, Political Studies, 68:1, 247–67.

- Hawkins, Kirk A. (2009). ‘Is Chávez Populist? Measuring Populist Discourse in Comparative Perspective’, Comparative Political Studies, 42:8, 1040–67.

- Hawkins, Kirk, Scott Riding, and Cas Mudde (2012). ‘Measuring Populist Attitudes’, Committee on Concepts and Methods: Working Paper Series No. 55, available at www.concepts-methods.org/Files/WorkingPaper/PC_55_Hawkins_Riding_Mudde.pdf

- Houle, Christian, and Paul D. Kenny (2018). ‘The Political and Economic Consequences of Populist Rule in Latin America’, Government and Opposition, 53:2, 256–87.

- Huber, Robert A., and Saskia P. Ruth (2017). ‘Mind the Gap! Populism, Participation and Representation in Europe’, Swiss Political Science Review, 23:4, 462–84.

- Hutter, Swen, and Hanspieter Kriesi (2013). ‘Movements of the Left, Movements of the Right Reconsidered’, in Jacquelien van Stekelenburg, Conny Roggeband, and Bert Klandermans (eds.), The Future of Social Movement Research: Dynamics, Mechanisms, and Processes. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 281–298.

- Immerzeel, Tim, and Mark Pickup (2015). ‘Populist Radical Right Parties Mobilizing “the People”? The Role of Populist Radical Right Success in Voter Turnout’, Electoral Studies, 40:4, 347–60.

- Jacobs, Kristof, Agnes Akkerman, and Andrej Zaslove (2018a). ‘The Voice of Populist People? Referendum Preferences, Practices and Populist Attitudes’, Acta Politica, 53:4, 517–41.

- Jacobs, Kristof, Marijn van Klingeren, Henk van der Kolk, Koen van der Krieken, Matthijs Rooduijn, and Charlotte Wagenaar (2018b). Het Wiv-referendum: Nationaal Referendum Onderzoek 2018, available at https://kennisopenbaarbestuur.nl/media/255931/wiv-referendumonderzoek-2018.pdf.

- Jacobs, Kristof, Marijn van Klingeren, Henk van der Kolk, Tom van der Meer, and Eefje Steenvoorden (2016). Het Oekraïne-referendum. Nationaal Referendum Onderzoek 2016, available at https://kennisopenbaarbestuur.nl/media/254244/het-oekra%c3%afne-referendum-nationaal-referendumonderzoek-2016.pdf.

- Jagers, Jan, and Stefaan Walgrave (2007). ‘Populism as Political Communication Style: An Empirical Study of Political Parties’ Discourse in Belgium’, European Journal of Political Research, 46:3, 319–45.

- Kioupkiolis, Alexandros (2016). ‘Podemos: The Ambiguous Promises of Left-Wing Populism in Contemporary Spain’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 21:2, 99–120.

- Kitschelt, Herbert (2002). ‘Popular Dissatisfaction with Democracy: Populism and Party Systems’, in Yves Mény and Yves Surel (eds.), Democracies and the Populist Challenge. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 179–196.

- Klandermans, Bert (2008). ‘The Demand and the Supply of Participation: Social-Psychological Correlates of Participation in Social Movements’, in David A. Snow, Sarah A. Soule, and Hanspeter Kriesi (eds.), The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 360–379.

- Kriesi, Hanspieter (2018). ‘The Implications of the Euro Crisis for Democracy’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:1, 59–82.

- Laclau, Ernesto (2005a). ‘Populism: What’s in a Name’, in Francisco Panizza (ed.), Populism and the Mirror of Democracy. London: Verso, 32–49.

- Laclau, Ernesto (2005b). On Populist Reason. London: Verso.

- Leininger, Arndt, and Maurits Meijers (2020) ‘Do Populist Parties Increase Voter Turnout? Evidence from over 40 Years of Electoral History in 31 European Democracies’, Political Studies. doi:10.1177/0032321720923257

- LISS-Data (2016a). ‘Election Survey Ukraine referendum’, CentERdata, available at http://www.dataarchive.lissdata.nl/study_units/view/651.

- LISS-Data (2016b). ‘Politics and Values’, CentERdata, available at https://www.dataarchive.lissdata.nl/study_units/view/663.

- LISS-Data (2016c). ‘Backgroud Variables’, CentERdata, available at https://www.dataarchive.lissdata.nl/study_units/view/322.

- Lucardie, Paul (2014). Democratic Extremism in Theory and Practice: All Power to the People. London: Routledge.

- Lucardie, Paul, and Gerrit Voerman (2012). Populisten in de Polder. Amsterdam: Boom.

- Mair, Peter (2002). ‘Populist Democracy vs Party Democracy’, in Yves Mény and Yves Surel (eds.), Democracies and the Populist Challenge. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 81–98.

- Meijers, Maurits, and Andrej Zaslove (2020). ‘Measuring Populism in Political Parties: Appraisal of a New Approach’, Comparative Political Studies.

- Mény, Yves, and Yves Surel (2002). ‘The Constitutive Ambiguity of Populism’, in Yves Mény and Yves Surel (eds.), Democracies and the Populist Challenge. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1–21.

- Moffitt, Benjamin, and Simon Tormey (2014). ‘Rethinking Populism: Politics, Mediatisation and Political Style’, Political Studies, 62:2, 381–97.

- Mudde, Cas (2004). ‘The Populist Zeitgeist’, Government and Opposition, 39:4, 541–56.

- Mudde, Cas (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, eds. (2012). Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat or Corrective for Democracy? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (2017). Populism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Müller, Jan-Werner (2014). ‘The People Must Be Extracted from within the People: Reflections on Populism’, Constellations, 21:4, 483–93.

- Niemeyer, Simon, and Julia Jennstål (2018). ‘Scaling up Deliberative Effects: Applying Lessons of Mini-Publics’, in André Bächtiger, John S. Dryzek, Jane Mansbridge, and Mark E. Warren (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 329–347.

- Norris, Pippa (2005). Radical Right: Voters and Parties in the Electoral Market. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Oesch, Daniel (2008). ‘Explaining Workers’ Support for Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe: Evidence from Austria, Belgium, France, Norway, and Switzerland’, International Political Science Review, 29:3, 349–73.

- Otjes, Simon, and Tom Louwerse (2015). ‘Populists in Parliament: Comparing Left-Wing and Right-Wing Populism in The Netherlands’, Political Studies, 63:1, 60–79.

- Pauwels, Teun (2014). Populism in Western Europe: Comparing Belgium, Germany and The Netherlands. London: Routledge.

- Peilingwijzer (2016). Peilingwijzer, Update 20 April 2016, available at https://peilingwijzer.tomlouwerse.nl/2016/04 (accessed 2 February 2020).

- Ramiro, Luis (2016). ‘Support for Radical Left Parties in Western Europe: Social Background, Ideology and Political Orientations’, European Political Science Review, 8:1, 1–23.

- Rooduijn, Matthijs, and Teun Pauwels (2011). ‘Measuring Populism: Comparing Two Methods of Content Analysis’, West European Politics, 34:6, 1272–83.

- Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal (2012). ‘The Ambivalence of Populism: Threat and Corrective for Democracy’, Democratization, 19:2, 184–208.

- Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal (2014). ‘The Responses of Populism to Dahl’s Democratic Dilemmas’, Political Studies, 62:3, 470–87.

- Rummens, Stefan (2017). ‘Populism as a Threat to Liberal Democracy’, in Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul Taggart, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Pierre Ostiguy (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Populism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 554–570.

- Scarrow, Susan E. (2003). ‘Making Elections more Direct? Reducing the Role of Parties in Elections’, in Bruce Cain, Russell J. Dalton, and Susan Scarrow (eds.), Democracy Transformed? Expanding Political Opportunities in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 44–58.

- Schaap, Linze, Frank Hendriks, Niels Karsten, Julien van Ostaaijen, and Charlotte Wagenaar (2019). ‘Ambitieuze en Ambivalente Vernieuwing Van de Lokale Democratie in Nederland’, Bestuurswetenschappen, 73:2, 47–69.

- Schwander, Hanna, Dominic Gohla, and Armin Schäfer (2020). ‘Fighting Fire with Fire? Inequality, Populism and Voter Turnout’, Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 61:2, 261–83.

- Spruyt, Bram, Gil Keppens, and Filip Van Droogenbroeck (2016). ‘Who Supports Populism and What Attracts People to It?’, Political Research Quarterly, 69:2, 335–46.

- Stavrakakis, Yannis, and Giorgos Katsambekis (2014). ‘Left-Wing Populism in the European Periphery: The Case of SYRIZA’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 19:2, 119–42.

- Taggart, Paul (2002). ‘Populism and the Pathology of Representative Politics’, in Yves Mény and Yves Surel (eds.), Democracies and the Populist Challenge. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 62–80.

- Thomassen, Jacques J., Carolien van Ham, and Rudy Andeweg (2014). De wankele democratie: Heeft de democratie haar beste tijd gehad? Amsterdam: Prometheus Bert Bakker.

- Urbinati, Nadia (2014). Democracy Disfigured. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Urbinati, Nadia (2017). ‘Populism and the Prinicple of Majority’, in Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul Taggart, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Pierre Ostiguy (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Populism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 571–589.

- Van der Brug, Wouter, Meindert Fennema, and Jean Tillie (2000). ‘Anti-Immigrant Parties in Europe: Ideological or Protest Vote?’, European Journal of Political Research, 37:1, 77–102.

- Van der Meer Tom (2017). Niet de kiezer is gek. Amsterdam: Unieboek Uitgeverij Het Spectrum.

- Van Hauwaert, Steven M., and Stijn Van Kessel (2018). ‘Beyond Protest and Discontent: A Cross‐National Analysis of the Effect of Populist Attitudes and Issue Positions on Populist Party Support’, European Journal of Political Research, 57:1, 68–92.

- Van Kessel, Stijn (2011). ‘Explaining the Electoral Performance of Populist Parties: The Netherlands as a Case Study’, Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 12:1, 68–88.

- Weyland, Kurt (2001). ‘Clarifying a Contested Concept: Populism in the Study of Latin American Politics’, Comparative Politics, 34:1, 1–22.