Abstract

In the European context, the Commission is responsible for monitoring and enforcing states’ compliance with EU legislation. However, the Commission often entrusts external actors to monitor and assess implementation. To what extent does the Commission withhold, partially or fully disclose compliance assessments? Drawing on reputational accounts of bureaucratic performance, it is expected that the Commission is confronted with competing incentives. On the one hand, the Commission needs to justify enforcement decisions based on expert evaluations. On the other hand, disseminating information about non-compliance could exacerbate relations with the member states and threatens to damage the Commission’s unique reputation as the main guardian of the EU treaties. Employing a novel data-set on the transparency of compliance assessments, it is found that the Commission discloses compliance assessments prepared by highly competent external actors only partially. The finding raises concerns about the extent to which wider audiences are sufficiently informed about national implementation outcomes.

Accountability of political leaders to public demands lies at the heart of democratic societies. Transparency is an important precondition for accountability, as it affects the extent to which citizens are able to observe deviations from the public interest and effectively voice their discontent (Lindstedt and Naurin Citation2010; Naurin Citation2006). In international politics, transparency encourages national representatives to take positions that cater to the preferences of their national constituencies during international negotiations (Cross Citation2013; Stasavage Citation2004). Studies on transparency have focused on electoral accountability as the key mechanism, prompting political institutions to disclose and disseminate information. However, electoral incentives are ill-suited to explaining the transparency of information collected by non-majoritarian institutions in contemporary policy making. Furthermore, as democratic norms are increasingly applied to international organisations, there is a need to broaden the focus of the transparency of data collected by supranational institutions (Grigorescu Citation2007).

The present study analyzes the transparency of compliance data regarding member states’ implementation performance held by the European Commission. While the EU Commission is responsible for both monitoring and enforcing compliance with EU legislation, it often entrusts external consultancies to collect data and assess the implementation of specific rules (Zhelyazkova et al. Citation2016). Under what conditions does the EU enforcement institution withhold, partially reveal or fully publicise assessments about member states’ implementation activities? Drawing on theories of bureaucratic reputation and blame-avoidance (Carpenter Citation2001; Hood Citation2007), I argue that the Commission faces competing incentives to disclose information about member states’ compliance gaps. On the one hand, transparency helps the Commission justify decisions to start infringement proceedings against law-violating governments based on credible information. On the other hand, transparency of policy violations could aggravate relations with non-compliant member states. Public disclosure of external assessments could also raise questions about the Commission’s own competences to evaluate member states’ compliance. Under these conditions, the Commission is expected to reveal enforced violations by member states only to interested parties who request access to specific compliance assessments (i.e., limited disclosure). Moreover, the expertise of external monitoring agencies helps the EU oversight institution justify its enforcement actions. However, the Commission is unlikely to make external compliance assessments public to avoid attacks about limited capacities to evaluate member states’ implementation performance. This is especially the case, when the assessments have been prepared by highly competent consultancies that threaten the Commission’s unique reputation as the guardian of EU treaties.

These hypotheses are tested with a novel data-set on the secrecy, limited and full public disclosure of external compliance assessments held by the EU Commission. The analysis supports the conjecture that transparency outcomes are conditional on external expertise. While the Commission responds positively to individual requests to share member states’ compliance data, it shies away from publicly disseminating compliance assessments prepared by highly competent consultancies. The findings from this study have implications for the legitimacy of supranational enforcement, as they suggest that the Commission strategically uses the transparency of member states’ activities to avoid reputation losses with respect to failing to fulfil its obligations.

Bureaucratic reputation and transparency

Transparency of policy outcomes is a multifaceted concept – broadly defined it can pertain to any dimension of accountability and democracy (Dahl Citation1971; Hollyer et al. Citation2011). While recent studies provide a more precise definition of transparency as ‘the release of information by institutions that is relevant to evaluating those institutions’ (Bauhr and Grimes Citation2014; Florini Citation1999: 5; Hollyer et al. Citation2011), most research focuses on the transparency of governments. However, as governments have transferred extensive powers to independent non-majoritarian institutions, non-elected bodies also face increasing pressures to justify that they operate fairly, openly, and transparently (Maggetti Citation2010). Although there is a growing research on the transparency of central banks (Cukierman Citation2009; Eijffinger and Geraats Citation2006), the empirical implications from these studies are often restricted to monitory policy and the predictability of financial markets.

In this study, I adopt a broader view to non-majoritarian institutions by arguing that decisions for transparency are generally driven by reputational incentives and concerns by non-elected bodies (Hood Citation2007). Bureaucratic reputation is broadly defined as a set of symbolic beliefs about the capacities, history, roles, obligations, and mission of an organisation that are embedded in multiple audiences (Blom-Hansen and Finke Citation2020; Carpenter Citation2010; Maor and Sulitzeanu-Kenan Citation2013). Bureaucratic reputation is a valuable asset for non-majoritarian organisations as it helps them build political support for their activities (Blom-Hansen and Finke Citation2020) and shields them from political attacks (Hood Citation2002; Weaver Citation1986). Transparency of information helps organisations boost their reputation by demonstrating that they can create solutions to problems (e.g. expertise, efficiency) and provide services (e.g. moral protection) that are in line with the expectations held by key audiences. In addition, transparency prompts organisations to limit blame for unfavourable outcomes through various presentational, policy, and agency strategies (Hood Citation2002; Citation2007; Weaver Citation1986).

A number of studies have demonstrated that reputational concerns affect organisational strategies to communicate information about their activities (Gilad et al. Citation2015; Hood Citation2007; Maor et al. Citation2013). In particular, Maor et al. (Citation2013) find that national regulators respond to allegations to core tasks regarding which their reputation is weak or it is still evolving. Conversely, a regulator who enjoys a strong reputation can afford to keep silent when faced with criticism about core activities. Furthermore, regulatory agencies are more likely to publicly acknowledge problems when accused of being overly lenient, but they deny allegations that regulation is excessive (Gilad et al. Citation2015). Existing research also shows that the media are less likely to report on observed errors, when a regulator has an established reputation for scientific expertise (Maor Citation2011).

One of the major findings from these studies is that the observability of errors damages the reputation of regulators as competent and expert-based institutions (Maor Citation2011). Therefore, organisations have incentives to hide unfavourable outcomes from their audience. However, it is also important to acknowledge that organisations have incentives to limit the transparency of favourable outcomes for which they cannot claim credit and that could even threaten their unique position (Carpenter Citation2001, Citation2010). Moreover, existing research assumes that transparency only affects institutions that disseminate information about their own activities. In the context of policy enforcement, however, the transparency of non-compliance does not only affect enforcement actors but their separate audiences too. On the one hand, transparency of implementation performance and detected non-compliance could boost the public image of enforcement agencies as competent and credible guardians of the law (Etienne Citation2015; Maor and Sulitzeanu-Kenan Citation2013). On the other hand, information about non-compliance negatively affects the reputation of law-violating actors by exposing their implementation gaps. Currently, we lack understanding which of these opposing reputational logics drives the decisions of enforcement institutions to disclose compliance gaps. Do enforcement agencies strive to maintain their own reputation as competent actors or do they yield to pressures from audiences benefitting from non-complianceFootnote1?

The present study addresses these gaps in knowledge by focussing on the transparency of compliance data held by the EU’s centralised enforcement institution: the EU Commission. As a supranational actor, the Commission faces competing pressures from more diverse audiences than national enforcement bodies, which include the EU governments, the EU Parliament, the media, organised interests, and the wider European public (Blom-Hansen and Finke Citation2020: 136). Furthermore, the increasing competences of the Commission have invigorated public concerns about the EU’s inherent democratic deficit. Whereas increased transparency could ameliorate these concerns, revealed information could also threaten the Commission’s reputation in relation to specific audiences that are negatively affected by supranational decisions.

Enforcement, monitoring and transparency of compliance data in the EU

In the context of supranational enforcement, the EU Commission represents the Union’s centralised enforcement system that is responsible for both monitoring member states’ compliance with EU law and prosecuting law-violating member states by starting infringement proceedings (McCormick Citation2015: 169–72; van Voorst and Mastenbroek Citation2017).

The infringement procedure consists of three formal consecutive stages: a letter of formal notice, a reasoned opinion, and, ultimately, a referral to the European Court of Justice (ECJ). With each stage of the infringement procedure, the Commission increases the pressure on member states to comply. In particular, letters of formal notice aim to eliminate cases of uncertainty about member states’ non-compliance. If a member state fails to provide a satisfactory answer to a formal letter, the Commission issues a reasoned opinion outlining the nature of the violation and demanding that the respective government rectifies the problem. If the member state in question continues its actions in breach of the EU law, the infringement proceeding enters the third stage, wherein the Commission refers the member state to the ECJ. However, the Commission uses litigation as a last resort, and the majority of cases are resolved before the final stage of the procedure (Börzel et al. Citation2012; Hofmann Citation2018).

Whereas the enforcement obligations of the Commission are formally codified in the EU Treaties, this is not the case for its monitoring activities. In practice, the Commission traditionally relies on three types of instruments to monitor compliance. First, the Commission requires that member state governments incorporate the EU directives in national legislation before a specified deadline. The Commission also regularly asks governments to prepare ‘congruence tables’ indicating how each directive provision is implemented in national legislation (Smith Citation2015). Second, much like other oversight institutions, the Commission relies on reactive ‘fire-alarms’ sounded by individuals, organised interests (e.g. trade unions and non-governmental organisations) and companies, which are negatively affected by non-compliance (McCubbins and Schwartz Citation1984; Tallberg Citation2002). Third, the Commission could also actively ‘police’ member states by conducting ad-hoc inspections in a number of countries regarding specific policy issues (Börzel and Knoll Citation2012; Smith Citation2015; Tallberg Citation2002).

Despite these mechanisms, the Commission’s ability to oversee compliance across 27 member states and various policy areas remains limited. For example, national governments are generally reluctant to submit congruence tables that outline their level conformity with EU directives, and even if they meet the directives’ deadlines, this doesn’t mean they comply substantively. Furthermore, reactive oversight relies on societal mobilisation and engagement of domestic actors to raise complaints about non-compliance (Cichowski Citation2007; Sedelmeier Citation2008). However, some member states suffer from weak societal mobilisation structures to effectively monitor their governments (Howard Citation2003; Schrama Citation2017). Finally, the Commission officials can only conduct a limited number of on-site checks in the member states, which tend to be time-consuming and politically contentious (Börzel and Knoll Citation2012). Consequently, the EU Commission increasingly relies on third parties, including consultancies, legal experts, and academic institutions, to actively monitor and evaluate the implementation of EU policies across different member states (van Voorst and Mastenbroek Citation2017: 642; Zhelyazkova et al. Citation2016). Third-party monitoring fulfils two main purposes. First, external consultancies conduct conformity-checking studies assessing how each EU requirement is incorporated in national legislation (Smith Citation2015). Second, the EU Commission also delegates responsibilities to external actors to collect data about the practical implementation of EU policies, thus, avoiding resource-intensive and politically fraught ‘in-house’ investigations in the member states (Börzel Citation2001; Börzel et al. Citation2012; Tallberg Citation2002). In other words, third-party monitoring both complements and substitutes the Commission’s traditional instruments to monitor compliance. For example, since 2003, Milieu Ltd has been conducting conformity-checking studiesFootnote2 of the transposition of directives related environmental EU policies (see Online appendix). Furthermore, Milieu also evaluates the practical implementation of EU directives through surveys, interviews, and questionnaires with relevant domestic stakeholders. In some instances, interest groups are also contracted to analyse member states’ compliance with specific rules. For example, Association of European Chambers of Commerce (Eurochambers) has evaluated the implementation of the ‘Services directive’ based on stakeholder surveys.

While there is still no empirical research on the causes and consequences of third-party monitoring in the EU context, the Commission acknowledges that the purpose of external assessments is to inform about the need for commencing infringement proceedings against non-compliant member states (Commission correspondence, 30.1.2015). Nevertheless, the EU Commission remains responsible for curbing non-compliance with EU policies. The use of external consultancies appears decentralised and the Commission enjoys discretion whether to accept and act upon the conclusions from an external study and whether or not to divulge external assessments to the public (Krämer Citation2014; Smith Citation2015).

At the same time, the EU has been facing increasing demands for more transparency (Cross Citation2013). Norms of transparency are currently enshrined in Regulation (EC) 1049/2001 regarding public access to European Parliament, Council and Commission documents, which demands greater openness in the work of EU institutions. The regulation puts into effect the right of public access to documents produced and processed by any EU body. Thus, it also obliges the Commission to grant public access to documents that are obtained from third parties. However, EU actors can decide whether and how to meet pressures for transparency. For example, the Commission can grant access to information about member states’ compliance to interested parties and upon formal requests only (limited disclosure). Alternatively, the Commission can make compliance assessments publicly available on its website (public disclosure). Finally, the Commission officials can also reject demands for disclosing assessments about member states’ compliance (secrecy) when they concern sensitive information that could damage relations with national governments (Commission correspondence, 3.5.2015).

Enforcement and transparency of member states’ implementation gaps

In line with reputation-based accounts of bureaucratic behaviour, the Commission is expected to respond to reputation incentives and costs of revealing information about member states’ compliance. In the context of EU enforcement, there are two opposing reputational logics that lead to contradictory expectations about the transparency of compliance data. Based on the first logic, the Commission’s reputation depends on its capacity to detect violations by EU member states and effectively prosecute instances of non-compliance. As a credible enforcement agent, the Commission also needs to appear unbiased in its decisions to expose and punish law-violating member states (Majone Citation2005; Tallberg Citation2002). For example, when women’s rights NGOs publicised that Poland had failed to establish an appropriate institution to supervise the equal access to goods and services, the Polish government claimed that the country was granted an exemption from this requirement. The relevant Directorate-General (DG) denied this claim and immediately started infringement proceedings against Poland (Sudbery Citation2010). Thus, the Commission is sensitive to accusations about non-enforcement of member states’ implementation problems and is willing to defend its reputation to external observers.

I expect that the Commission will be willing to publicly disclose compliance data, when it successfully prosecuted law-violating governments. Transparency of compliance offers enforcement actors a protective shield against hostile audiences, who threaten to challenge their decisions (Busuioc and Lodge Citation2017; Hood Citation2002, Citation2011). Much like other enforcement actors, the EU Commission faces pressures to maintain an image of a credible enforcement institution whose actions are informed by evidence-based expertise of member states’ implementation activities. Consequently, if the Commission decides to prosecute cases of non-conformity, it is also pressured to justify its actions. This is especially important in situations of enforcement, when domestic actors and member states benefiting from non-compliance have incentives to challenge the Commission enforcement activities (König and Mäder Citation2014). In other words, the disclosure of member states’ compliance problems shields the Commission from blame for unjustified enforcement.

H1a: The Commission is more likely to publicly disclose information about member states’ implementation activities (relative to limited disclosure and secrecy), if it started infringement proceedings against non-compliance.

Conversely, based on the second reputational logic, compliance assessments reflect badly on the EU governments, especially when they expose implementation gaps that triggered infringement proceedings by the Commission (Börzel et al. Citation2012). The EU policy-making process is based on consensus, where national representatives try to reach compromises (Thomson Citation2011). In principle, compromise-based decision making should alleviate problems of non-compliance at the implementation stage (Thomson et al. Citation2007). Under these circumstances, instances of excessive non-compliance reveal that national governments have failed to honour their supranational commitments despite adopted compromises. Furthermore, public revelations about non-compliance risk mobilising domestic groups benefitting from the EU policies against national governments. Facing pressures from the EU member states, the Commission is expected not to publicize member states’ implementation gaps. However, the Commission could still justify the initiation of infringement proceedings by responding to individual requests to share compliance data. As a result, the Commission is more likely to partially share member states’ implementation outcomes, when this information is demanded.

H1b: The Commission is more likely to disclose information about member states’ implementation activities only to interested parties (limited disclosure), if it started infringement proceedings against non-compliance.

The conditional effect of external monitoring expertise

Furthermore, the expertise of third-party monitoring moderates the relationship between enforcement and transparency. The reputation of non-majoritarian institutions depends on expertise-based performance that forms ‘the core basis for the expectations of their multiple regulator audiences’ (Carpenter Citation2001; Rimkutė Citation2018: 73). In the EU context, this means that decisions to enforce compliance should be guided by involving external actors with high level of expertise.

However, the public disclosure of member states’ implementation gaps could also harm reputationally the Commission, especially if compliance data was obtained by highly competent and experienced monitoring institutions. Theories of bureaucratic reputation have emphasised the importance of ‘reputation uniqueness’ by referring to the ability of organisations to show that they can deliver outputs that cannot be obtained from their competitors (Carpenter Citation2001; Maor and Sulitzeanu-Kenan Citation2016; Rimkutė Citation2018). Moreover, organisations are also engaged in cultivating different types of reputation regarding their unique expertise and capacities to perform different tasks (Maor Citation2011). In the context of EU enforcement, the Commission nurtures two unique types of reputation: (1) as a competent monitoring agency that oversees compliance across all member states and policy areas and (2) as an unbiased enforcement institution that prosecutes law violations based on credible evidence about states’ implementation performance. These two reputational bases work in opposition. On the one hand, credible enforcement depends on extensive data collection about member states’ performance at different stages of the implementation process and, hence, requires the services of highly professional monitoring agencies. On the other hand, the Commission is also the main oversight institution responsible for monitoring compliance across member states. While relying on third-party monitoring alleviates the costs of conducting own investigations, it also increases competition from oversight institutions, especially those with extensive competences to monitor compliance in different countries and issue areas. After all, some EU member states may prefer to relocate resources for monitoring compliance to external consultancies. In a similar vein, monitoring capacity is not just a matter of data availability about member states’ implementation performance, but it also requires a discernible capacity to analyse compliance data. By promoting compliance assessments by highly professional consultancies, the Commission risks signalling that it has limited capacities to conduct compliance evaluations itself. Finally, transparency of third-party compliance assessments inhibits ‘credit-claiming’ for expert-based enforcement (Weaver Citation1986). In other words, the Commission cannot cultivate a positive reputation as a competent enforcement agent, when another organisation detected all implementation gaps.

Based on the arguments above, I expect that the Commission is likely to share compliance assessments prepared by external actors with extensive monitoring expertise, only to a limited extent. However, the Commission is unlikely to disseminate this information to wider audiences.

H2: The Commission is more likely to disclose information about enforced implementation gaps on demand (limited disclosure), when compliance data was obtained from a credible and competent oversight institution.

H3: The Commission is less likely to publicly disclose information about enforced implementation gaps (public disclosure), when compliance data was obtained from a credible and competent oversight institution.

Data and methods

In order to test hypotheses, the present study relies on a unique dataset on different levels of transparency of external compliance assessments held by the Commission.Footnote3 Compliance assessments concern the implementation performance of a member state regarding a specific EU directive. The analysis focuses on directives because the Commission prioritises directives in post-hoc evaluations about member states’ implementation (van Voorst and Mastenbroek Citation2017). Furthermore, most compliance assessments concern conformity-checking studies of the transposition of EU directives in national legislation. EU instruments such as regulations and decisions are excluded from such assessments because they do not require transposition. Finally, while I uncovered evaluations on the application of EU regulations, these studies mostly discussed best practices rather than member states’ level of compliance.

The empirical analysis is limited to four policy areas: Internal Market and Services; Justice and Home Affairs (JHA); Environment; and Social Policy. The selection aims to ensure variation with respect to the Commission enforcement activities and builds on existing research on reputation and transparency. First, the sectors differ in the number of infringement cases issued by the Commission. Whereas Environment is generally the most infringement-prone policy area, fewer infringement cases were opened against the Social Policy directives (Börzel and Knoll Citation2012; Zhelyazkova et al. Citation2016). Second, the selection accounts for sectorial differences regarding the strength of reputational mechanisms discussed in the literature (Maor et al. Citation2013). In particular, the EU has an established reputation in regulating Internal Market policy. Instead, the EU’s competences to legislate on immigration and social policy are relatively new and its reputation in these areas is still evolving.

Unfortunately, it was not possible to collect data on transparency for all major policy areas within the scope of a single study. As the Commission does not inform citizens which EU policies are subject to external compliance assessment, uncovering the existence of all assessment reports is highly cumbersome and time-consuming. Before collecting information on transparency, I identified all relevant EU policies in each sector and manually searched for conformity-checking and implementation reports using various EU sources, including OpenSpending datasets (2015) and OpenTender.org (on the EU’s contractual relations with external consultancies), the Commission annual overviews, and the working programmes of the relevant DGs. I also contacted the Commission and the external consultancies to ensure that a given directive was subject to assessment.

The external evaluation reports were prepared in the period between 2005 and 2013 and encompass all member states except Croatia. Because external agencies evaluated member states’ compliance only once, the unit of analysis reflects the level of transparency of evaluations regarding the implementation of an EU directive by a given member state. The final sample includes transparency of conformity assessments regarding 69 EU directivesFootnote4 in relation to 27 member states (Social Policy directives (11), Internal Market (18), Justice and Home Affairs (18), Environment (22)), which amounts to 1843 potential transparency outcomes. However, not all member states were subject to evaluations and some directives were not applicable to all EU member states (e.g. the UK, Denmark and Ireland have opt-outs for some JHA directives).

Dependent variable: transparency outcomes

The dependent variable is the Commission’s transparency practices in relation to external assessments about a member state’s compliance with a given directive. Thus, the analysis captures the extent to which the relevant DGs publicly disclose compliance data beyond the formal transparency requirements. Many of the compliance assessments are publicly available on the websites of the relevant DGs in the EU Commission (public disclosure). When this was not the case, I requested the remaining assessments using the Commission online request form. In most cases, the Commission provided individual access to reports about the performance of some member states, but refused to disclose information about others. Based on this information, it is possible to identify three distinct types of transparency practices: (1) Secrecy (the Commission refused to disclose information about member states’ implementation activities); (2) Limited disclosure (the Commission granted individual access to requested assessments, but did not make the information public) and (3) Public disclosure (the report is publicly available on the Commission website).

As all assessments are subject to the same formal rules, analysing practices enables studying actual transparency of compliance data across policy areas, directives and member states. Nevertheless, this approach has potential weaknesses. In particular, transparency practices may change over time. For example, the Commission may impose only temporary restrictions over the dissemination of information. To address this concern, I revisited the Commission websites a year after the completion of the project to see whether any of the requested reports were publicly available. In the case of rejected reports, I re-sent requests for information disclosure a year after completing the data collection.Footnote5

Supranational enforcement and external monitoring expertise

The measure for supranational enforcement records whether or not the Commission opened an infringement case against a member state regarding an EU directive (Infringement case = 1). The Commission infringement database provides information about individual stages of the infringement procedure (‘formal letter’, ‘reasoned opinion’ and ‘referral to the ECJ’) for specific member states and directives. Because all compliance assessments relate to the conformity of national legislation and implementation outcomes, the analysis focuses on infringement cases that were specifically opened against ‘non-conformity’.Footnote6 As letters of formal notice serve to eliminate cases of uncertainty, the analysis is based on the issuing of a reasoned opinion (coded as 1). The reasoned opinion constitutes the first stage where the Commission establishes that there is a problem of non-compliance.

External monitoring expertise is captured by characteristics of the external oversight institution charged with evaluating member states’ implementation activities. An oversight institution is deemed to have narrow expertise if it has assessed member states’ legal conformity with only one directive (coded as 0). Monitoring expertise is higher, but still limited if an external institution has been contracted to evaluate legal compliance in relation to multiple directives from one policy area (coded as 1). Instead, contracted consultancies with diverse expertise have prepared compliance assessments for directives from different policy areas (e.g. environment and internal market) (coded as 2). Finally, agencies with extensive monitoring expertise are not only able to provide compliance assessments concerning various issues, but they also analyse different stages of the implementation process (e.g. both legal and practical implementation) (coded as 3). Thus, the measure captures the expertise of oversight institutions to inspect member states’ compliance on diverse issues and at distinct stages of the implementation process.Footnote7 The indicator for external monitoring expertise is a continuous variable (that ranges between 0 and 3) in the main analysis and it is a categorical variable in the robustness checks (see Online appendix).

Alternative explanations: the power of different audiences

The analysis also accounts for the possibility that the Commission is responsive to demands of different audiences. In particular, member states are generally reluctant to have their implementation gaps exposed to the public because non-compliance could damage their international reputations as cooperative partners committed to compliance with EU legislation. States are more sensitive to reputational costs imposed by external actors, the more dependent they are on future co-operation (Börzel et al. Citation2012; Keohane and Nye Citation1977). On the one hand, exposed non-compliance has a stronger negative impact on smaller states with limited weight in the EU decision-making process. On the other hand, the Commission may be more responsive to challenges by more powerful EU member states (Börzel et al. Citation2012) and refuse to disclose data about their implementation gaps. Member states’ voting power is quantified based on the Banzhaf index (Banzhaf Citation1965). Furthermore, the Commission may not want to further alienate Eurosceptic publics and governments by publicly disclosing their implementation performance. Societal support for EU integration is computed based on different Eurobarometer surveys related to issues from each of the four policy areas. Eurobarometer has regularly asked respondents whether they believe that particular policies should be decided by their national government (coded as 1), or by the EU (coded as 2). The variable takes the average score for the years where information is available on societal preferences regarding a particular policy sector. The measure for government EU support is based on the Chapel Hill surveys on party positions (Bakker et al. Citation2015). The measure records the average position on EU integration for all parties in government, weighted by their seat share in government in the year that the directive was implemented by a given member state.Footnote8

The EU Commission could also refrain from revealing member states’ implementation outcomes, if non-compliance favours powerful domestic interest groups. To control for the influence of interest group intermediation, the analysis accounts for country-level corporatism based on the ICTWSS database on institutional characteristics of trade unions, wage setting, state intervention, and social pacts (Visser Citation2015). In a more corporatist system, national implementation outcomes are more likely to reflect interest group preferences.Footnote9

Finally, the Commission may decide not to reveal member states’ implementation activities, when it holds similar preferences to national governments on substantive policy issues. This argument is theoretically grounded in theories of legislative–bureaucratic relations suggesting that executive actors cater to legislators who support similar policy objectives (Epstein and O’Halloran Citation1994). Furthermore, existing research has also shown that the Commission policy preferences affect its enforcement behaviour (Thomson et al. Citation2007). To measure levels of preference alignment between member states and the Commission, I first computed the left–right position of states’ government at the time of policy implementation (Crombez and Hix Citation2015) based on the ParlGov database. I also identified the party position of each relevant Commissioner who was in charge of a given policy area at the date of transposition of a directive.Footnote10 The indicator for preference alignment captures the proximity between the Commission and member state government on the left–right dimension.

Alternative sources of compliance data

The final set of controls accounts for the possibility that information about member states’ compliance could be disseminated through alternative channels, not controlled by the EU’s centralised enforcement system. For example, some member states are more likely to disclose information about their activities because of strong Freedom of Information (FOI) laws. The measure for government transparency was obtained from the World Economic Forum (WEF) (Schwab Citation2015). It captures how easy it is for businesses in a country to obtain information about changes in government policies and regulations affecting their activities.

In addition, compliance data could be disclosed by national parliaments with privileged access to information about EU affairs. National parliaments differ in the extent to which they oblige governments to share information about their EU-related activities (Winzen Citation2012). I employ the ‘National parliamentary control of European Union affairs’ data-set indicators for the presence and stringency of EU-related information requirements imposed by national parliaments on their executives.

Finally, information about (non-)compliance can be obtained and disseminated through ‘fire-alarms’ sounded by affected citizens and interest groups (McCubbins and Schwartz Citation1984; Tallberg Citation2002). Existing research suggests that the effectiveness of ‘fire-alarm’ supervision depends on the strength of civil society (Sedelmeier Citation2008). I employ two separate indicators for civil society strength: citizen participation in voluntary organisations and the involvement of civil society organisations (CSOs) in government consultations (Schrama and Zhelyazkova Citation2018). Civic participation is measured by the percentage of respondents in Eurobarometer surveys who volunteer in organisations specifically focussing on the issue areas covered in this study. CSO involvement in policy making is based on data from the V-Dem project (Coppedge et al. Citation2019) whether major CSOs are routinely consulted by policy-makers on issues relevant to their members. The Online appendix presents the descriptive statistics for all variables employed in the analysis.

Explaining the transparency of compliance assessments

The empirical analysis applies multinomial logistic regression because the dependent variable comprises three distinct levels of transparency: secrecy, limited disclosure and public disclosure. Furthermore, transparency practices concerning compliance assessments are likely dependent on decisions to evaluate member states’ implementation performance. Enforcement institutions that face reputational threats from disclosing compliance data may be reluctant to keep records of sensitive information (Etienne Citation2015; Hood Citation2007). Transparency practices could be also endogenous to decisions to delegate responsibilities to external oversight institutions with extensive expertise. Therefore, I controlled for the potential dependency of transparency practices on the availability of external compliance assessments in the robustness analysis (see below).

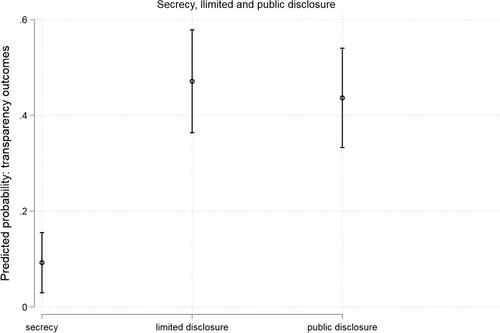

Before discussing the results on the impact of enforcement and monitoring expertise on transparency, I assess the probabilities of different transparency outcomes. shows that the Commission often grants access to compliance assessments either on demand or publicly. On average, the Commission refuses to disclose only 8 percent of the total external assessments, while the average probability of limited and public disclosure is 50 and 42 percent respectively. However, transparency outcomes are unequally distributed across the four policy areas. In particular, all assessments concerning Social Policy directives were publicly available. This finding supports existing research that non-majoritarian institutions are more vocal and transparent in areas, where they do not have an established reputation yet (Maor et al. Citation2013). Additional robustness checks excluding Social policy directives did not produce substantially different results (see online appendix).

presents the estimates from the main analysis of secrecy, limited, and public disclosure of compliance assessments. Models 1–4 show the likelihood of limited (Models 1 and 2) and public disclosure (Models 3 and 4) of compliance assessments relative to secrecy. Models 5 and 6 show the likelihood of public compared to limited disclosure of compliance data. In addition, the analysis tests the moderating effect of external monitoring expertise on the relationship between enforcement and transparency practices (Models 2, 4 and 6). All models include robust standard errors at the level of EU directives. The online appendix presents the results when controlling for policy-area differences and robust standard errors at the level of member states.Footnote11

Table 1. Multinomial logit analysis of the secrecy, limited and public disclosure of compliance assessments held by the Commission.

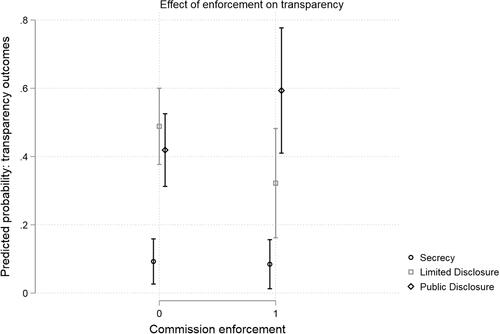

Contrary to the expectations in H1(a–b), the issuing of reasoned opinions by the Commission does not significantly influence the transparency of compliance assessments. further illustrates that the Commission is less likely to keep compliance assessments confidential regardless of whether it started infringement proceedings. However, the predicted probability of public disclosure increases if the Commission opened an infringement case. Although the change is not significant, it indicates that the Commission does not shy away from publicly shaming law-violating member states by exposing their implementation gaps.

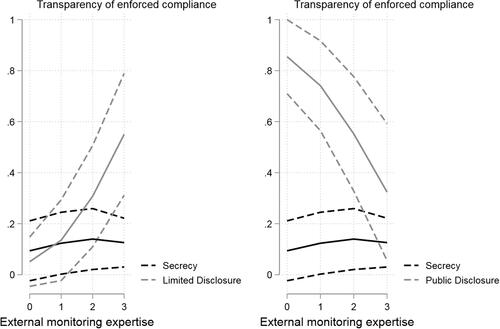

While we do not find strong support for the direct relationship between Commission enforcement and transparency, the analysis indicates that the expertise of external overseers moderates this relationship, as evidenced by the significant interaction effects. To facilitate the interpretation of the results, illustrates the probabilities of limited (left-hand) and public disclosure (right-hand) versus secrecy at different levels of external monitoring expertise and for enforced non-compliance (infringement case = 1). The figure specifically highlights the transparency of member states’ implementation gaps that triggered the start of the infringement procedure by the EU Commission. illustrates the contrasting effect of external expertise on the transparency of member states’ implementation of EU directives. In particular, the Commission is more likely to disclose – albeit to a limited extent — information about member states’ policy deviations that led to the initiation of infringements proceedings. In line with H2, the effect is significant only when this information was collected by an agency with extensive experience in assessing compliance. The result supports the conjecture that the Commission seeks to justify its enforcement decisions by relying on highly competent external actors.

Figure 3. Comparing the predicted probabilities of transparency outcomes at varying levels of external expertise and for enforced non-compliance.

Conversely, the probability of public disclosure of member states’ prosecuted non-compliance decreases for higher levels of external monitoring expertise (right-hand). The probability that the Commission will publicly reveal compliance assessments is 0.85 if information is collected and assessed by an institution with narrow monitoring expertise and decreases to 0.32 for assessment reports prepared by agencies with extensive resources to monitor various stages of the policy cycle. Compliance assessments prepared by highly competent agencies have equal chance to be kept confidential as evidenced by the overlapping confidence intervals (right-hand).

In sum, the analysis shows that higher levels of external monitoring expertise help the Commission justify enforcement decisions (when demanded), but it also decreases the observability of implementation gaps to wider audiences. The results from Model 1 also show that the negative effect of agency expertise on public disclosure is not conditional on enforcement (see ). Therefore, the Commission is unlikely to advertise the assessments of agencies with extensive expertise, even when member states’ complied with an EU directive (i.e. when the Commission did not start infringement cases). This result supports the assumption that the Commission strategically guards its unique reputation as the main supervision institution responsible for assessing member states’ implementation. Publicly advertising the expertise of external overseers makes the Commission vulnerable to blame for excessively relying on third-party monitoring. Furthermore, compliance assessments produced by agencies with extensive monitoring expertise decrease the ability of the Commission to claim credit for monitoring member states’ compliance (Hood Citation2011; Weaver Citation1986).

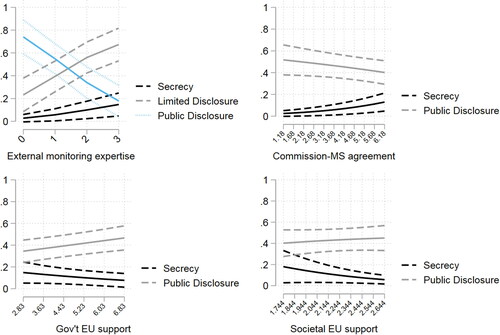

Figure 4. Predicted probabilities of transparency outcomes at varying levels of external expertise, level of congruence b/n the Commission a member state on the left-right dimension, government EU support and societal EU support.

The analysis in also supports the relevance of government characteristics on the public disclosure of compliance assessments. More precisely, the Commission is more likely to publicly reveal information about the implementation performance of more EU-supportive governments and member states with overwhelmingly Europhile publics (see ). Conversely, the Commission is hesitant to further aggravate its relations with Eurosceptic governmentsFootnote12 and avoids antagonising Eurosceptic citizens by publicly disclosing compliance data. The analysis also shows that the Commission is less likely to reveal information about a member state’s implementation performance, the more it holds similar policy preferences with the respective government on the left–right dimension. illustrates that the more the overseeing Commissioner and the implementing government align on the left–right dimension, the lower the probability of public disclosure and the higher the probability of secrecy. This result is in line with theories of legislative—bureaucratic relations based on which the Commission is expected to cater to governments, who share their policy objectives (Epstein and O’Halloran Citation1994; Thomson and Torenvlied Citation2011).

The analysis shows that the Commission is still responsive to government preferences in decisions regarding the public disclosure of member states’ implementation outcomes. However, the guardian of the Treaties does not respond to all relevant audiences. Neither member states’ decision power, nor different levels of corporatism significantly affect the transparency of compliance assessments. Decisions to withhold or reveal compliance assessments do not depend on alternative sources of information either, as government transparency, parliamentary control, and civil society strength (CSO consultation and civic participation) do not have significant effects on transparency (see ).

Robustness analysis

In order to verify the results from the multinomial logit models, I conducted various robustness checks that are presented in the online appendix. First, I estimated Heckman probit models on the likelihood that transparency practices depend on the Commission incentives to delegate authorities to external agencies. The selection equation further controls for additional factors informed by transaction-cost models of delegation (Epstein and O’Halloran Citation1994). In particular, the Commission is expected to delegate monitoring responsibilities regarding highly complex issues. Policy complexity is commonly measured as the number of recitals in a directive (Thomson and Torenvlied Citation2011; van Voorst and Mastenbroek Citation2017). Moreover, the Commission is less likely to require the services of external agencies, if it can single-handedly monitor compliance across member states. Thus, the analysis controls for the presence of reporting clauses in a directive requiring member states to regularly inform the Commission of their implementation activities (Zhelyazkova and Yordanova Citation2015). Finally, the Commission is more likely to request assessments by external actors when a directive was adopted jointly by the Council and the EU Parliament. In this case, the Commission does not only need to satisfy demands by the member states, but also by the Parliament (Blom-Hansen and Finke Citation2020). The results do not substantially differ from the main analysis.Footnote13

Second, I also tested alternative model specifications to validate the main findings. The robustness analysis partially controls for the Commissioners’ policy preferences based on their positions on the economic and cultural left–right dimensions. The measure assumes that Commissioners with more economically rightist positions are more likely to agree with the objectives of Internal Market directives, whereas the opposite is true for Social policy directives. In a similar vein, more culturally liberal Commissioners are expected to emphasise the importance member states’ compliance with environmental and JHA directives. The indicator at least partially accounts for the Commission’s varying policy preferences in the absence of more precise data.

Conclusion and discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the conditions under which the EU’s centralised enforcement institution reveals information about member states’ policy outcomes in relation to EU legislation. More precisely, the Commission often entrusts third parties with varying degrees of expertise to collect data and assess member states’ implementation of specific EU policies. When does the Commission disclose external compliance assessments? On the one hand, the EU’s main supervisory institution faces pressures to justify its enforcement actions based on reliable evaluations of member states’ implementation performance. On the other hand, public disclosure of external compliance assessments incurs reputational risks for both the EU Commission and law-violating governments. For example, exposing member states’ implementation gaps risks alienating national governments and European citizens. Furthermore, excessive reliance on external oversight damages the unique reputation of the Commission as the main monitoring institution in the EU (Maor Citation2011; Rimkutė Citation2018). External compliance assessments could prompt hostile audiences to challenge the Commission’s competence as the main guardian of the Treaties and inhibits its ability to claim credit for detecting member states’ violations (Weaver Citation1986).

The findings from this study have important implications for the legitimacy of enforcement in the EU context. More generally, I find support that the EU Commission enjoys discretion over the transparency of information about member states’ implementation activities, even if this information concerns nationally sensitive topics. Furthermore, I do not find overwhelming evidence that the disclosure of compliance assessments is driven by member states’ incentives to conceal their implementation gaps. Secrecy is rare and the Commission releases compliance assessments, even when external reports expose member states’ violations of EU rules. This finding contrasts with previous results showing that national governments have remained in charge of the dissemination of information produced by international bodies (Grigorescu Citation2007).

Nevertheless, the findings also raise concerns about the extent to which citizens and interest groups are sufficiently informed about non-compliance. First, I hypothesised and found that transparency of enforced non-compliance depends on the expertise of external oversight actors. In particular, the Commission justifies enforcing policy violations by disclosing assessments produced by agencies with extensive expertise only to a limited extent. However, the Commission is unlikely to make these assessments publicly available. By pushing compliance assessments away from the public eye, the Commission deprives interest groups and European citizens from gaining a better understanding of member states’ implementation outcomes, especially when this information has been collected by highly competent overseers. Second, the findings suggest that the Commission does not reveal information about compliance equally across member states. Compliance assessments of member states with Eurosceptic governments and publics are less likely to be widely disseminated. Given that Eurosceptic societies are especially susceptible to EU politicisation (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009), the EU Commission seems to respond to threats of politicisation (Rauh Citation2019) by keeping member states’ implementation outcomes out of public sight. These findings raise concerns about the long-term impact of growing levels of Euroscepticism on the Commission incentives for transparency.

More generally, the findings from this study contribute to research on the politics of information disclosure and reputational incentives of supranational organisations (Blom-Hansen and Finke Citation2020). Thus, this research goes beyond formal rules of transparency as a choice between secrecy and full transparency (Rittberger and Goetz Citation2018). In particular, the study underscores the importance of limited disclosure as a possible strategy by enforcement institutions to guard their unique reputations as competent and impartial guardians of the law, when confronted with pressures to increase openness with respect to their activities. This finding supports ideas that increasing transparency is unlikely to lead to a fundamental transformation in organisational behaviour. Instead, transparency prompts political and bureaucratic actors to adopt new creative strategies to avoid blame and claim credit for observed outcomes (Hood Citation2007).

The findings remain stable across various robustness checks while also accounting for decisions to delegate oversight powers to external actors. Nevertheless, the results also raise questions about the Commission’s incentives to rely on external consultancies for monitoring and assessing member states’ implementation outcomes. Future research should further elucidate the conditions for entrusting external actors with varying levels of expertise to evaluate member states’ compliance. Moreover, it is also important to recognise that transparency is a dynamic process. For example, the Commission may change its transparency practices over time due to increased demands for openness by organised interest groups or because of newly acquired information about member states’ non-compliance. Finally, it remains an open question whether the public disclosure of compliance assessments actually increases citizens’ awareness of national responses to EU legislation. Future research should attempt to shed more light on the consequences of information disclosure on the actual observability of compliance gaps.

fwep_a_1845943_sm3705.pdf

Download PDF (162.3 KB)Acknowledgements

This article has greatly benefitted from helpful suggestions by Tobias Hofmann, Rik Joosen, Markus Haverland, Geske Dijkstra, Reinout van der Veer, the members of the ‘European and Global Governance’ group of Erasmus University Rotterdam and two anonymous WEP reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Asya Zhelyazkova

Asya Zhelyazkova is Assistant Professor in European Politics and Public Policy at the Department of Public Administration and Sociology (DPAS), Erasmus University Rotterdam. Her research focuses on member states’ compliance and implementation of EU policies, delegation in the EU, responsiveness of EU policies. Her recent work has appeared in journals such as the European Journal of Political Research, European Union Politics, the Journal of European Public Politics, and the Journal of Common Market Studies. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 Furthermore, studies of communication strategies focus on organizational responses to criticisms by key audiences. However, reputation-seeking organizations are eager to avoid accusations in the first place by strategically managing the release of information about their activities.

2 Conformity-checking reports outline how each directive provision has been incorporated in national legislation and whether the transposed provisions conform to the directive requirements.

3 The practice of delegating compliance assessments to external actors is well-documented by some legal scholars (Krämer Citation2014; Smith Citation2015). However, there is no research examining the exact nature of these assessments and the mandate of external agencies.

4 The total number is limited to 69 directives because I excluded reports that described the implementation process, but did not explicitly assess member states’ level of compliance.

5 Another potential disadvantage is that transparency practices may be biased towards characteristics of the persons requesting information. For example, the Commission may be less likely to refuse requests from NGOs or government officials than an individual EU citizen. The purpose of this study is, however, to assess the transparency of information to EU citizens.

6 Infringement cases against delayed transposition of EU directives are excluded from the analysis.

7 External expertise is a characteristic of the agency. Thus, an agency that assessed member states’ compliance only in relation to a specific directive could be still rated as highly competent if it had previously completed evaluations on diverse policy areas and at different implementation stages.

8 The Chapel Hill data-set does not include information about Cyprus, Luxembourg and Malta.

9 Whereas most studies employ Lijphart’s index of interest group pluralism, it does not include information about the new CEE member states (Lijphart Citation1999).

10 The external assessment reports provide information about the date of the main transposition measure in each member state. When this information was not available, I took the date of the transposition deadline.

11 I excluded policy-area controls from the main analysis because they over-determined outcomes of public disclosure. This is because all Social Policy assessments are publicly available. As already indicated, excluding Social Policy directives from the analysis does not lead to different results.

12 An alternative explanation would suggest that pro-EU governments encounter fewer implementation problems and consequently face fewer reputational losses from the transparency of their implementation activities. However, alternative model specifications did not support this conjecture.

13 Moreover, some compliance assessments are produced by the same external consultancies (e.g. Milieu Ltd; Tipik Legal; Odesseus). The variable for external monitoring expertise and clustering in directives already accounts for the dependency in the observations at the level of agencies. Therefore, robustness multilevel models did not produce reliable estimates.

References

- Bakker, Ryan, et al. (2015). ‘Measuring Party Positions in Europe: The Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File, 1999–2010’, Party Politics, 21:1, 143–52.

- Banzhaf, John (1965). ‘Weighted Voting Doesn’t Work: A Mathematical Analysis’, Rutgers Law Review, 19:2, 319–43.

- Bauhr, Monika, and Marcia Grimes (2014). ‘Indignation or Resignation: The Implications of Transparency for Societal Accountability’, Governance, 27:2, 291–320.

- Blom-Hansen, Jens, and Daniel Finke (2020). ‘Reputation and Organizational Politics: Inside the EU Commission’, Journal of Politics, 82:1, 135–48.

- Börzel, Tanja (2001). ‘Non-Compliance in the European Union: Pathology or Statistical Artefact?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 8:5, 803–24.

- Börzel, Tanja, Tobias Hofmann, and Diana Panke (2012). ‘Caving in or Sitting It out? Longitudinal Patterns of Non-Compliance in the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy, 19:4, 454–71.

- Börzel, Tanja, and Moritz Knoll (2012). ‘Quantifying Non-compliance in the EU: A Database on EU Infringement Proceedings’, Berlin working paper on european integration 15, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin Center for European Studies.

- Busuioc, Madalina, and Martin Lodge (2017). ‘Reputation and Accountability Relationships: Managing Accountability Expectations through Reputation’, Public Administration Review, 77:1, 91–100.

- Carpenter, Daniel (2001). The Forging of Bureaucratic Autonomy: Reputations, Networks, and Policy Innovation in Executive Agencies, 1862-1928. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Carpenter, Daniel (2010). Reputation and Power: Organizational Image and Pharmaceutical Regulation at the FDA. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Cichowski, Rachel A. (2007). The European Court and Civil Society: Litigation, Mobilization and Governance. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Coppedge, Michael, et al. (2019). ‘V-Dem Dataset Version 9’, Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemcy19

- Crombez, Christophe, and Simon Hix (2015). ‘Legislative Activity and Gridlock in the European Union’, British Journal of Political Science, 45:3, 477–99.

- Cross, James P. (2013). ‘Striking a Pose: Transparency and Position Taking in the Council of the European Union’, European Journal of Political Research, 52:3, 291–315.

- Cukierman, Alex (2009). ‘The Limits of Transparency’, Economic Notes, 38:1-2, 1–37.

- Dahl, Robert (1971). Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Eijffinger, Sylvester C. W., and Petra M. Geraats (2006). ‘How Transparent Are Central Banks?’, European Journal of Political Economy, 22:1, 1–21.

- Epstein, David, and Sharyn O’Halloran (1994). ‘Administrative Procedures, Information, and Agency Discretion’, American Journal of Political Science, 38:3, 697–722.

- Etienne, Julien (2015). ‘The Politics of Detection in Business Regulation’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 25:1, 257–84.

- Florini, Ann M. (1999). ‘Does the Invisible Hand Need a Transparent Glove? The Politics of Transparency’, Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics, 1–40 http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWBIGOVANTCOR/Resources/florini.pdf%5Cn http://derechoasaber.org.mx/documentos/pdf0042.pdf

- Gilad, Sharon, Moshe Maor, and Pazit Ben Nun Bloom (2015). ‘Organizational Reputation, the Content of Public Allegations, and Regulatory Communication’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 25:2, 451–78.

- Grigorescu, Alexandru (2007). ‘Transparency of Intergovernmental Organizations: The Roles of Member States, International Bureaucracies and Nongovernmental Organizations’, International Studies Quarterly, 51:3, 625–48.

- Hofmann, Tobias (2018). ‘How Long to Compliance? Escalating Infringement Proceedings and the Diminishing Power of Special Interests’, Journal of European Integration, 40:6, 785–801.

- Hollyer, James R., Peter Rosendorff, and James Vreeland (2011). ‘Democracy and Transparency’, Journal of Politics, 73:4, 1191–11205.

- Hood, Christopher (2002). ‘The Risk Game and the Blame Game’, Government and Opposition, 37:1, 15–37.

- Hood, Christopher (2007). ‘What Happens When Transparency Meets Blame Avoidance?’, Public Management Review, 9:2, 191–210.

- Hood, Christopher (2011). The Blame Game: Spin, Bureaucracy, and Self-Preservation in Government. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks (2009). ‘A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus’, British Journal of Political Science, 39:1, 1–23.

- Howard, Marc (2003). The Weakness of Civil Society in Post-Communist Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Keohane, Robert O., and Joseph Nye (1977). Power and Interdependence. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company.

- König, Thomas, and Lars Mäder (2014). ‘The Strategic Nature of Compliance: An Empirical Evaluation of Law Implementation in the Central Monitoring System of the European Union’, American Journal of Political Science, 58:1, 246–63.

- Krämer, Ludwig (2014). ‘EU Enforcement of Environmental Laws: From Great Principles to Daily Practice-Improving Citizen Involvement’, Environmental Policy and Law, 44:1–2, 247–56.

- Lijphart, Arend (1999). Patterns of Democracy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Lindstedt, Catharina, and Daniel Naurin (2010). ‘Transparency Is Not Enough: Making Transparency Effective in Reducing Corruption’, International Political Science Review, 31:3, 301–22.

- Maggetti, Martino (2010). ‘Legitimacy and Accountability of Independent Regulatory Agencies: A Critical Review’, Living Reviews in Democracy, 2, 1–10.

- Majone, Giandomenico (2005). Dilemmas of European Integration: The Ambiguities and Pitfalls of Integration by Stealth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Maor, Moshe (2011). ‘Organizational Reputations and the Observability of Public Warnings in 10 Pharmaceutical Markets’, Governance, 24:3, 557–82.

- Maor, Moshe, Sharon Gilad, and Pazit Ben Nun Bloom (2013). ‘Organizational Reputation, Regulatory Talk, and Strategic Silence’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 23:3, 581–608.

- Maor, Moshe, and Raanan Sulitzeanu-Kenan (2013). ‘The Effect of Salient Reputational Threats on the Pace of FDA Enforcement’, Governance, 26:1, 31–61.

- Maor, Moshe, and Raanan Sulitzeanu-Kenan (2016). ‘Responsive Change: Agency Output Response to Reputational Threats’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 26:1, 31–44.

- McCormick, John (2015). European Union Politics. 2nd ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McCubbins, Mathew D., and Thomas Schwartz (1984). ‘Congressional Oversight Overlooked: Police Patrols versus Fire Alarms’, American Journal of Political Science, 28:1, 165–79.

- Naurin, Daniel (2006). ‘Transparency, Publicity, Accountability: The Missing Links’, Swiss Political Science Review, 12:3, 90–8.

- Rauh, Christian (2019). ‘EU Politicization and Policy Initiatives of the European Commission: The Case of Consumer Policy’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:3, 344–65.

- Rimkutė, Dovilė (2018). ‘Organizational Reputation and Risk Regulation: The Effect of Reputational Threats on Agency Scientific Outputs’, Public Administration, 96:1, 70–365.

- Rittberger, Berthold, and Klaus H. Goetz (2018). ‘Secrecy in Europe’, West European Politics, 41:4, 825–45.

- Schrama, Reini (2017). Rooted Implementation – The Practical Implementation of EU Policy through Cooperative Society. ETH Zürich, available at https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/handle/20.500.11850/202231 (accessed 15 April 2020).

- Schrama, Reini, and Asya Zhelyazkova (2018). ‘“You Can’t Have One without the Other”: The Differential Impact of Civil Society Strength on the Implementation of EU Policy’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:7, 1029–48.

- Schwab, Klaus (2015). ‘The Global Competitiveness Report 2015–2016’, World Economic Forum, 21, 78–80.

- Sedelmeier, Ulrich (2008). ‘After Conditionality: Post-Accession Compliance with EU Law in East Central Europe’, Journal of European Public Policy, 15:6, 806–25.

- Smith, Melanie (2015). ‘Evaluation and the Salience of Infringement Data’, European Journal of Risk Regulation, 6:1, 90–100.

- Stasavage, David (2004). ‘Open-Door or Closed-Door? Transparency in Domestic and International Bargaining’, International Organization, 58:04, 667–703.

- Sudbery, Imogen (2010). ‘The European Union as Political Resource: NGOs as Change Agents’, Acta Politica, 45:1-2, 136–57.

- Tallberg, Jonas (2002). ‘Paths to Compliance: Enforcement, Management, and the European Union’, International Organization, 56:3, 609–43.

- Thomson, Robert (2011). Resolving Controversy in the European Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thomson, Robert, and René Torenvlied (2011). ‘Information, Commitment and Consensus: A Comparison of Three Perspectives on Delegation in the European Union’, British Journal of Political Science, 41:1, 139–59.

- Thomson, Robert, René Torenvlied, and Javier Arregui (2007). ‘The Paradox of Compliance: Infringements and Delays in Transposing European Union Directives’, British Journal of Political Science, 37:4, 685–709.

- van Voorst, Stijn, and Ellen Mastenbroek (2017). ‘Enforcement Tool or Strategic Instrument? the Initiation of Ex-Post Legislative Evaluations by the European Commission’, European Union Politics, 18:4, 640–57.

- Visser, Jelle (2015). ICTWSS Data Base. Version 5.0. University of Amsterdam: Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies AIAS.

- Weaver, R. Kent (1986). ‘The Politics of Blame Avoidance’, Journal of Public Policy, 6:4, 371–98.

- Winzen, Thomas (2012). ‘National Parliamentary Control of European Union Affairs: A Cross-National and Longitudinal Comparison’, West European Politics, 35:3, 657–72.

- Zhelyazkova, Asya, Cansarp Kaya, and Reini Schrama (2016). ‘Decoupling Practical and Legal Compliance: Analysis of Member States’ Implementation of EU Policy’, European Journal of Political Research, 55:4, 827–46.

- Zhelyazkova, Asya, and Nikoleta Yordanova (2015). ‘Signalling ‘Compliance’: The Link between Notified EU Directive Implementation and Infringement Cases’, European Union Politics, 16:3, 408–28.