Abstract

Studies of political contestation of EU decision making usually focus on the division lines in the European Parliament and, to a lesser extent, the Council of Ministers. This article seeks to broaden the analysis of the contestation of EU politics by conceptualising EU contestation across the EU’s ‘multilevel parliamentary field’. It distinguishes three ideal-typical structures of contestation – national, inter-institutional, and transnational contestation – and hypothesises that the more institutionalised the mode of EU decision making, the more likely it is that contestation takes place along transnational lines. The article then draws on the empirical literature on multilevel parliamentarism to assess the plausibility of this hypothesis for four modes of EU decision making: EU legislation, executive decisions, policy coordination and institutional design. Finding the hypothesis broadly confirmed, the article concludes that, if the supranational implications of EU decision making are to be appreciated, also less institutionalised decision-making modes require some form of transnational contestation.

Research on political contestation in the European Union has tended to focus on the ‘ordinary legislative procedure’, also since this procedure has become relatively standardised and is open to systematic data collection. Most attention has gone out to voting behaviour in the European Parliament (EP). The main finding there has been that political conflict in the EP has come to be defined almost completely in party-ideological terms (Hix et al. Citation2007). As a consequence, national considerations have been pushed to the background in EP politics, re-emerging only on rare, but particularly salient, occasions (Crespy and Gajewska Citation2010). More recent research on contestation in the EU has come to include the Council, the other EU legislator. While ideological preferences also register in the Council (e.g. Hagemann and Høyland Citation2008), governments’ behaviour turns out to be significantly conditioned by the stringency of parliamentary oversight that they are under (Hagemann et al. Citation2019). Combining these findings for the EP and the Council, this seems an appropriate mix of considerations for the EU as a ‘demoi-cracy’, that is, a polity of polities (a.o. Nicolaïdis Citation2004): transnational ideological considerations prevail but, on occasion, state-specific concerns come to the fore as well.

Ironically, however, once the ordinary legislative procedure had been fully consolidated in the Treaty of Lisbon in 2009, the polycrisis (Zeitlin et al. Citation2019) that hit the EU over the subsequent decade led EU decision making to turn to all kinds of alternative decision-making modes (Bickerton et al. Citation2015). That applies for the measures taken to avert the bankruptcy of Greece as much as for the migrants deal with Turkey, the negotiation of Brexit, and the surveillance of national economic policies through the European Semester. These decisions exemplify how decision making in the multilevel, demoi-cratic, system of the EU is always more complex and diverse than the way national polities legislate.

Hence, while EU politics has become increasingly contested (Kriesi Citation2016; Zeitlin et al. Citation2019), this article posits that we can only fully grasp the way this contestation gets structured if we examine it across different modes of decision-making. To develop this point, the article examines the following question: How does the pattern of parliamentary contestation vary across different EU policy-making modes? The analysis takes parliaments as the main sites where political contestation gets structured and focusses on the EP and national parliaments as loosely connected arenas (Crum and Fossum Citation2009). The way contestation gets structured across these parliamentary arenas may vary. In particular, we can distinguish contestation that gets mobilised across parliamentary institutions – for instance through transnational coalitions between parliamentarians of the same ideological persuasion – from contestation that rather pits different parliamentary institutions against each other. To map the ways in which the structure of contestation may vary, the article argues that the way that political contestation becomes structured across the multiple parliaments in the EU is a function of the mode of EU decision making involved.

The purpose of this article is primarily conceptual in that it seeks to broaden the analysis of the contestation of EU politics and to suggest a way to think about such contestation across the different policy-making modes through which the EU operates. Still, I also want to demonstrate empirically that the mode of policy-making matters for the way that political contestation gets structured. In particular, the article suggests the plausibility of the hypothesis that the less integrated the mode of EU decision making, the more likely contestation is to pit different parliaments against each other rather than to issue in cleavage lines that run across the different representative institutions. From a normative perspective, such an absence of crosscutting cleavage lines would be problematic as it implies that the main arenas in which collective will-formation takes place do not only remain disconnected from each other but even work at cross purposes.

The empirical analysis remains of an exploratory character as the complexity and diversity of the policy-making modes analysed prevents the collection of large-scale standardised data. Instead, the article relies on a meta-analysis of the literature on the role of parliaments in the EU (e.g. Auel et al. Citation2015; Auel and Christiansen Citation2015; Crum and Fossum Citation2013; Fasone and Lupo Citation2016). This literature has rapidly developed following the new powers that the Lisbon Treaty assigned to national parliaments, and it offers a useful point of reference if we want to track EU contestation beyond the Brussels institutions. Many empirical analyses have focussed on the Early Warning Mechanism that invites national parliaments to file an opinion when they find that proposed EU legislation violates the principle of subsidiarity (e.g. Cooper Citation2019; Gattermann and Hefftler Citation2015). Other studies have examined, among other things, the development of inter-parliamentary conferences (Herranz-Surrallés Citation2014; Kreilinger Citation2018) and the inter-parliamentary relations in the context of macro-economic policy coordination (Crum Citation2018; Fasone Citation2019).

The next section locates the argument in the broader debate about the evolving nature of EU decision making, operationalises the two key variables (EU policy-making modes and structure of parliamentary contestation) and outlines the hypothesised relations between them. The subsequent sections then use the available literature to sketch the dominant structure of contestation in four different EU policy modes. A final section compares the findings across the four domains and concludes.

Conceptualising political contestation in a multilevel parliamentary field

Recent theories of the EU as a demoi-cracy highlight the multilevel and multi-centredness of its decision making (Cheneval and Schimmelfennig Citation2013; Nicolaïdis Citation2004, Citation2013). The demoi-cratic reading of the EU emphatically opposes the suggestion that the EU is an integrated political system-in-the-making with a clear political centre (like a federal state). As Nicolaïdis (Citation2013: 353) puts it, a demoi-cracy involves ‘a Union of peoples, understood both as states and as citizens, who govern together but not as one’. In other words, as a demoi-cracy, the EU is recognised as a functional system of collective government while the primary processes of political identification and will-formation remain fragmented. In principle, the underlying demoi may be constituted along all kinds of, potentially overlapping identifications (Nicolaïdis Citation2004). However, in the context of the EU, the primary demoi are identified with the peoples of its member states, at most supplemented by a weakly constituted pan-EU demos that overarches all of them as EU citizens.

A demoi-cratic understanding of the EU has distinct implications for the main sites where contestation and deliberation on EU decision making takes place. Rather than focussing on the EP or even the EU Council, it highlights the importance of national parliaments to authorise and legitimate EU decision making (Bellamy Citation2013; Kröger and Bellamy Citation2016). At the same time, such an understanding has to make sense of the way these fragmented processes of deliberation interact and are aggregated at the collective level of the EU. Crum and Fossum (Citation2009) offer the concept of a ‘multilevel parliamentary field’ to conceptualise the interactions between national parliaments and between them and the EP. While the relations between parliaments in the EU remain under-institutionalised, there is indeed empirical evidence of them influencing each other as regards the modes of scrutiny adopted (Bormann and Winzen Citation2016; Buzogány Citation2013) and the positions adopted on EU proposals (Malang et al. Citation2019). Such transnational interactions encourage the alignment of patterns of contestation across national parliaments in a process of Europeanisation of national politics.

The complexity of EU decision making does not stop with recognising its multi-levelled and multi-centred nature. While the empirical studies just cited look at EU legislation, decision making in the EU takes many different forms, with non-legislative decisions gaining increasing prominence in the recent crisis years (Bickerton et al. Citation2015). If we define EU legislation as the adoption of generally binding acts that impose rights and obligations on EU subjects, it can be differentiated from three alternative forms of EU decision making.Footnote1 First, there is the EU adoption of one-off executive decisions. Typical examples of such decisions are the initiation of military and civilian missions in the foreign-policy domain, the imposition of penalties upon member states for breaking the Stability and Growth Pact or for failing to comply with the Union’s values (Art.7 TEU), or the activation of loan facilities to assist countries in financial distress. A second alternative mode of decision making involves policy coordination, in which the EU adopts non-binding recommendations that remain subservient to the national political level. In recent times, the main focus of policy coordination in the EU is the European Semester (Verdun and Zeitlin Citation2018).

Thirdly, we can distinguish EU legislation with direct effect on citizens and firms from institutional (or even constitutional) meta-decisions that rather serve to set the conditions under which decisions can be adopted. At the highest level, such decisions require an Intergovernmental Conference for member states to agree on amendments to the EU treaties. However, in the absence of any such conferences since the agreement on the Treaty of Lisbon, institutional design decisions can be elaborated through Inter-Institutional Agreements, as long as they remain within the limits set by the treaties. Each of these modes of EU decision making differs in the rules by which they are governed and in the way powers are divided between the national and the European level. We expect these institutional differences to affect the way that patterns of contestation map over the different parliaments involved.

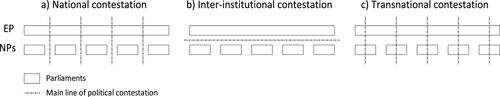

Ideal-typically, we can think of the pattern of contestation across EU parliaments to adopt three main forms: a national, an inter-institutional and a transnational pattern (). The first pattern presupposes that national interests prevail and are effectively represented by national parliaments. Thus, the main lines of political contestation intersect with the divisions between national parliaments (NPs) and also divide the EP along national lines. In the second pattern, the main cleavages also intersect with institutional divisions but rather concentrate on the distinction between (all) national parliaments on the one hand and the EP on the other. This structure of contestation one can for instance expect with issues that concern the transfer of competences between the national and the European level. Thirdly, one can envisage a situation in which transnational coalitions emerge across different parliaments. Typically, one would expect such coalitions to organise along party-ideological lines – pitting left-wing parliamentarians against right-wing ones; progressives against conservatives; populists against representatives of the establishment – in each of the parliaments involved.

The remainder of this article uses the literature on (national) parliaments in the EU to examine the dominant pattern of contestation that emerges for each of the four modes of decision making distinguished: legislation, executive decision making, policy coordination and institutional design. As a hypothesis, I expect the national pattern of contestation to become less dominant the more integrated the mode of decision making is. Thus, taking EU legislation as the most Europeanised policy mode, I expect it to be the most likely mode to invite the emergence of transnational coalitions. In contrast, as EU executive decision making and policy coordination remain very much anchored in national politics, I expect the pattern of contestation to track national divisions more closely. In turn, the constitutive issue of establishing inter-parliamentary conferences can rather be expected to invite institutional self-interests.

EU legislation

EU legislation is the mode of EU decision making that is most institutionalised and has the most direct force. It is characterised by the use of EU laws (directives and regulations) and is concentrated in the establishment and regulation of the EU single market in the broadest sense, including for instance questions of environmental standards and labour migration. EU legislation is also the mode of EU decision making in which the roles of the national parliaments and the EP are most clearly defined. The EP plays a prominent role in the EU’s ordinary legislative procedure as it operates as a full co-legislator besides the Council of Ministers with full rights to veto and to amend EU legislation. National parliaments can engage in EU legislation by scrutinising the involvement of their government in the Council (Raunio Citation2005).

Given its focus on fundamental political questions in the single market, one might consider EU legislation a most likely case to invite transnational contestation across EU parliaments. However, for a long time, national parliamentarians had few incentives to engage with European legislation and left their governments considerable discretion in negotiating with their counterparts and the EP (Pollak and Slominski Citation2003). Still, more recent analysis does find that greater oversight powers of the national parliament leads governments to operate more critically in EU decision making (Hagemann et al. Citation2019).

The Lisbon Treaty sought to increase the involvement of national parliaments. Most notably, Protocol 2 of the Lisbon Treaty established the Early Warning Mechanism (EWM), which assigns a specific responsibility to national parliaments to monitor whether EU draft legislation complies with the principle of subsidiarity. If a third (or a quarter, in the case of EU legislation affecting the area of freedom, security and justice) of all parliamentary chambers comes to a negative judgement on the issue, the EU legislator (usually the Commission) is obliged to reconsider its proposal. Besides the specific (collective) power of the EWM, national parliaments retain the right to put any other kind of concerns on the draft legislation to their government or, indeed, to avail themselves of the various means of direct political dialogue with the Commission.

In response to the new powers provided by the Treaty of Lisbon, most EU national parliaments upgraded their procedures and resources in EU affairs (Auel et al. Citation2015). Notably, these investments have not directly led to an extensive use of the EWM (Cooper Citation2019). National parliaments remain highly selective in their involvement with EU legislation. Over the first decade of the Treaty of Lisbon, the required threshold of reasoned opinions has been reached on only three legislative proposals.

Still, the expansion of national parliaments’ capacities that was invited by the Lisbon Treaty has had a broader spill-over effect on parliaments’ engagement in EU affairs and, in particular, in the direct scrutiny of their governments’ engagement in EU affairs (Miklin Citation2017). Indeed, the concerns of national parliaments often range far beyond the mere issue of subsidiarity on which the EWM requires them to focus. Typically, two of the three directives on which national parliaments activated the EWM did not survive in their original form, even if the Commission rejected the subsidiarity challenge: the Monti II directive was eventually shelved for lack of political support and the proposal for a European Public Prosecutor’s Office was adopted as a form of enhanced cooperation, thus allowing individual governments to opt out from it. It is difficult to say whether the mobilisation of national parliaments was critical in these cases or whether it was only an indication that their concerns were shared more widely. Still, looking at the broader set of the proposals that received at least half of the required number of reasoned opinions, Cooper (Citation2019) finds that the engagement of national parliaments left a mark on the eventual outcome of four out of nine legislative proposals involved even if the EWM threshold was not reached.

What is more, while the EWM’s focus on subsidiarity reduces the chances of vertical coordination between the national parliaments and the EP (Cooper Citation2013), it encourages national parliaments to coordinate strategically among each other. There have been examples of national parliamentarians actively lobbying their colleagues in other countries to coordinate the submission of subsidiarity complaints (Cooper Citation2015: 1413; Miklin Citation2017: 378). Such coordination yields various kinds of coalitions among parliaments. A large-n analysis by Malang et al. (Citation2019) suggests that transnational ideology is indeed a prominent factor as parliaments with similar ideological compositions influence each other in submitting reasoned opinions. An illustration of such a transnational coalition comes from the pre-Lisbon case of the EU Services directive, where Social-Democratic parties, trade unions and other NGOs did engage in transnational coordination (Crespy and Gajewska Citation2010; Crum and Miklin Citation2013). However, there are also clear cases where inter-parliamentary coalitions have rather formed around the intersection of national interests. Most telling is the coalition of national parliaments that mobilised against the revised posted workers directive. This coalition was formed almost exclusively by parliaments from Central and Eastern Europe who sought to push back on any new restrictions for their countrymen and -women to be posted elsewhere in the EU (Fromage and Kreilinger Citation2017; Jančić Citation2017).

For sure, most contestation over EU legislation remains concentrated at the EU level. Thus, contestation is above all marked by the ideological cleavage lines that dominate the EP. As the Lisbon Treaty sought to increase the involvement of national parliaments in EU legislation, it has affected the structure of contestation in two, somewhat contradictory, ways. On the one hand, the focus of the EWM on subsidiarity feeds into a sense of inter-institutional contestation between the EP and national parliaments, where national parliaments try to claw back powers that a majority in the EP seeks to Europeanise. On the other hand, national parliaments have become more alert and more likely to tighten the scrutiny of their national government in those specific cases in which EU legislation does raise national political concerns. Notably, the structure of coordination between national parliaments often seems to be informed by transnational ideological considerations, although occasionally national concerns also come to the fore.

EU executive decisions

As a second EU policy mode, I turn to EU executive decisions, which are one-off in character rather than that they have general application and are particularly employed when responding to foreign policy issues or crisis situations. Notably, such EU decisions very much continue to be collectively controlled by its member governments and these have been reluctant to delegate executive power. If they allow supranational agents – like the High Representative, other Commissioners, or the president of the Euro-group – to make such decisions, they do so under the very close shadow of the (European) Council. In the end, many EU executive decisions, and the consensus required for them, only emerge under conditions of great functional pressure (typically some form of ‘crisis’), intense deliberation among the member governments, and effective policy entrepreneurship of a leading actor (be it a prominent member government or a supranational actor).

As these executive decisions remain under the control of the member governments, scrutiny and accountability of them is relegated to national parliaments; even if the EP may organise a debate on such decisions, it lacks the powers to intervene. The exclusive reliance on national parliaments for accountability can be justified in those cases, like EU military missions, where the member states that commit to the decision do so wholeheartedly, while those who are not committed get a complete opt-out. Importantly, however, most EU executive decisions are more than the mere sum of the wills of the member governments; they are the product of a long-winding decision-making process that requires considerable compromising from all member states (cf. Wallace Citation2005: 87).

While national parliaments are the main arenas for the political contestation of EU executive decisions, they are unlikely to capture any such transnational dynamics. For one, it is beyond their institutional horizon. What is more, as this kind of decisions often goes to the heart of national sovereignty (and national culture), their contestation remains captive to distinctively national frames and is likely to trigger concerns of national sovereignty. These national inclinations are reinforced by the fact that there is much variation in the scrutiny powers that national parliaments command over these EU decisions as well as in their willingness to actually employ these powers if they have them (Wessels et al. Citation2013).

In the foreign policy domain, we find that, while decision making at the EU level has become increasingly standardised, scrutiny in EU national parliaments remains patchy and has tended to diverge along national lines rather than to converge. Typically, when it comes to committing to participation in an EU military mission, some member governments (e.g. in Germany or Spain) need the explicit consent of their national parliaments while for others (e.g. Belgium) this is not required (Peters et al. Citation2013). Cultural differences remain deeply entrenched in the ways that parliamentarians scrutinise EU foreign policy decisions (Huff Citation2015). Looking specifically at how national parliaments scrutinise EU military missions, Schade (Citation2018) finds that parliamentary engagement remains divided depending on distinct political traditions and national troop contributions. On the whole, Anna Herranz-Surrallés (Citation2019) asserts that, as national politicisation of the involvement in European Security policy activates sovereignty concerns, the parliamentarisation of foreign policy tends to re-emphasise national divisions rather than to contribute to their Europeanisation.

In the decisions taken in immediate response to the euro crisis, the interdependencies between national decisions was unassailable. Still, contestation became very much concentrated at the national level, inviting the use of national stereotypes (Adler-Nissen Citation2017) and highlighting the division between northern and southern member states (Matthijs and McNamara Citation2015). Typically, in parliamentary debates, governments rather invoked national economic interests to justify their commitment to European measures than to appeal to a sense of European solidarity (Closa and Maatsch Citation2014). Such national divides are reinforced by the different levels of parliamentary engagement. Thus, in the case of disbursement of loans or guarantees by the European Stability Mechanism, in about half of the EMU member states the approval of parliament is required, while in the other half the approval of the Minister of Finance suffices (Kreilinger Citation2015). These different levels of parliamentary activity give rise to significant asymmetries in the democratic control that national parliaments exercise over EU decisions (Benz Citation2013), which reflect and reinforce pre-existing asymmetries in the power member states wield within the EU. Thus, although other factors play a role as well, most notably the involvement of the Federal Constitutional Court, it is no coincidence that Germany, as the greatest contributor in the European Stability Mechanism, can also ‘afford’ to grant a major role to its national parliament in approving disbursements.

Overall, then, the absence of a European arena for accountability very much affects the way political contestation becomes structured. For sure, many EU executive decisions – be they about military missions or about bailing out countries – resonate strongly across European borders. However, being left to national parliaments, national divisions tend to be reinforced. In the absence of an effective European arena for accountability, it is not self-evident to which parliamentary arena any transnational concerns would be best addressed. For that reason, it is rare for effective transnational coalitions to emerge on these issues. At most, parliamentarians take advantage of the exchange of information as it takes place through inter-parliamentary conferences (see below).

EU policy coordination

A third kind of decisions for which it is interesting to analyse the relationship between national parliaments and the EP is policy coordination. In the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008/2009 and its effects on the stability of the euro zone, policy coordination in the economic policy domains has been significantly revamped and integrated in the so-called European Semester (Verdun and Zeitlin Citation2018). True to the original idea of policy coordination, the EU leaves the primacy to the national budgetary procedures and does not adopt binding legislation. Still, the EU-level does seek to steer member states to minimise the negative externalities of their policies and to foster convergence between them. Where member states deviate all too much from the collectively set benchmarks and norms, they can be put under tightened supranational scrutiny and, ultimately, may be liable to a penalty.

In contrast to EU legislation, we find that the national parliaments retain the upper hand in EU policy coordination. They remain the ultimate authority over the national budget – to the extent that they effectively hold that power according to the national provisions – during the (second) half of the year that counts as the ‘national semester’. The EP plays a much more modest role in this process. It does not get to approve any final decisions. Instead, it only exercises a consultative and advisory role in the course of the European Semester.

Because of the primacy of the national level in policy coordination, political contestation remains very much organised along national lines. Most of the political choices are framed in specific national contexts, and the kind of policies we see pursued by the left and right of the political spectrum vary markedly between the different political-economic systems and between, so-called, creditor and debtor countries. Typically, much of the understanding of the euro crisis has been framed in national stereotypes (Adler-Nissen Citation2017) that precluded the building of inter-institutional, let alone truly transnational coalitions. Analysing the actual operation of the European Semester, Aleksandra Maatsch (Citation2017) highlights how the politics of complying with EU Country-Specific Recommendations remain very much conditioned by the national political context, and how these debates do not connect across countries. She also underlines that there is significant variation in the ability of national parliaments to contest EU policy recommendations due to the differences in powers that parliaments traditionally enjoy. Similarly, Mette Buskjaer Rasmussen (Citation2018) finds substantial differences in the level of activity of parliaments in the European Semester. Overall, however, she finds ‘little appetite for parliamentary debate’ (Rasmussen Citation2018: 352), and even less interest among parliaments in the transgovernmental dimension of the European Semester.

These findings confirm the assessment that, even if many European parliaments have reinforced their role in the budgetary process in the wake of the financial crisis in Europe, ‘these reforms do not outweigh the centralisation of EU powers’ (Jančić Citation2016: 225; cf. Fasone Citation2019). A critical issue in this respect is that, as the European Semester requires national governments to commit to their main economic policies already in spring, the ability for national parliaments to contest these pre-commitments in the actual budgetary debates in autumn is severely constrained (Dawson Citation2015: 989). Notably, however, also already in the earlier stages of the process, national parliaments are generally content to be consulted on the pre-commitments of their governments (in the form of the Stability and Convergence Programmes and the National Reform Programme) rather than that they insist on the power to amend and veto these (Crum Citation2018).

EU policy coordination thus constrains the scope of political contestation in national parliaments. This might be corrected if there were a more effective coupling of the parliamentary scrutiny between the European part of the semester in spring and the adoption of national budgets in autumn. Formally, such coupling is foreseen through the Inter-Parliamentary Conference on Stability, Economic Coordination and Governance (SECG), which convenes in every early spring and autumn to bring together national and European parliamentarians. In practice, however, there is no evidence of national and European parliamentarians aligning their strategic agendas. The very design of the inter-parliamentary conference has taken much time and energy, and revealed the divergent interests parliamentarians take in the cooperation (Cooper Citation2016; Kreilinger Citation2018). The EP’s involvement is focussed on the meeting in February, which it hosts in the context of the ‘European Parliamentary Week’, an event that also features a number of inter-parliamentary committee meetings. In turn, most national MPs tend to approach the inter-parliamentary conference merely as a means to collect input for their involvement in the budgetary process at home (cf. Kreilinger Citation2018: 74ff.). The EP could certainly deepen its cooperation with national parliaments. However, as Cristian Fasone (Citation2019: 18) highlights, even the formal possibility for the EP to include national parliamentarians in the economic dialogues that it maintains with EU economic executives has not been used.

Overall, there appears a kind of division of tasks between the national parliaments taking centre-stage during the national semester in autumn and the EP operating as the main parliamentary forum during the preceding European Semester in spring. Such a division of tasks allows each of them to remain relatively agnostic to what the other does. As a consequence, rather than that we see that the basic choices of macroeconomic policy invite the emergence of transnational coalitions, national debates remain impervious to whatever political contestation takes place at the European level.

EU institutional design: inter-parliamentary conferences

Since the Treaty of Lisbon, no major new EU treaties have been negotiated. Notably, however, national parliaments and the EP have been closely involved in the establishment of three new inter-parliamentary conferences: the Inter-Parliamentary Conferences on the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and on Stability, Economic Coordination and Governance (SECG), as well as the Joint Parliamentary Scrutiny Group for Europol. The interactions between the parliaments in establishing these conferences are quite instructive, both for the underlying tensions that they display as well as for the ways in which they were eventually resolved. Arguably, zooming in on institutions that exclusively involve the two kinds of parliaments may amplify the level of animosity that is found. Ultimately, however, all meta-decisions are about the division of powers – and, in the EU, specifically about the division of competences between levels of government – and in that light the relatively simple settings of inter-parliamentary conferences may well provide a clearer light on the structure of inter-parliamentary contestation than what one would be able to uncover in a case of EU Treaty negotiations. What is more, the focus on inter-parliamentary conferences has the advantage that we can look across three different policy domains and that the debates involved have been extensively analysed in the literature.

The inter-parliamentary conferences are truly inter-institutional institutions that rely on the joint involvement of both the EP and the national parliaments. They serve two kinds of functions. First, they provide platforms for parliaments to exchange information and experiences. Second, they serve as public arenas in which European executives can give account of their past actions and communicate their plans for the future. Importantly, these conferences do not adopt any decisions that have direct (binding) effect. Most spelled out are probably the powers of the Joint Parliamentary Scrutiny Group in the Europol regulation (EU Regulation 2016/794), but also in this case its prerogatives are restricted to the right to be briefed, to receive information, and to be consulted (without binding effect).

In the processes of establishing the three recent inter-parliamentary conferences, the main political division line opposed the EP against the national parliaments. Exactly because these conferences are about the way that the EP and that national parliaments organise their powers together, they were bound to invite a sense of competition between them and, hence, for contestation to become primarily structured along interinstitutional lines (Cooper Citation2016; Herranz-Surrallés Citation2014; Kreilinger Citation2018; Ruiz de Garibay Citation2013). One recurring issue was whether the delegation of the EP should be equal in size to that of individual national parliaments or bigger. A second question was whether these conferences would only be able to adopt positions by consensus or whether some form of qualified majority voting (like ¾ in COSAC) could be used. Obviously, considering itself the primary parliamentary body at the European level, the EP pushed for its delegation to be bigger than that of national parliaments. It also opposed any form of majority voting and, more generally, as Cooper (Citation2016: 249) puts it with regard to the SECG-conference, ‘any independent decision-making authority or appearance of democratic legitimacy’.

This kind of institutional decisions leaves little relevance for party ideologies or the possibility to forge ideological coalitions across institutions. If anything, we find some national differences interfering with the dominant inter-institutional cleavage as some parliaments (typically, the German, Belgian and Italian ones) adopt positions more sympathetic to the EP while others (typically, France and some Scandinavian parliaments) strongly insist on the primacy of national parliaments (Cooper Citation2016; Herranz-Surrallés Citation2014; Kreilinger Citation2018).

Still, while the coming into operation of all three conferences was significantly delayed by the inter-institutional wrangling that ensued, eventually we have seen a gradual settlement of the inter-parliamentary cooperation in the different conferences and even the emergence of an institutional format for handling conflicts. Notably, the EU Speakers’ Conference has come to be recognised as a kind of meta-regulatory, or appeal, authority that can rule authoritatively when negotiations become deadlocked (Cooper Citation2017; Fasone Citation2016). Thus, the Speakers’ Conference has arbitrated on the rules of procedure for the CFSP conference (Herranz-Surrallés Citation2014: 970) as well as for the SECG conference (Cooper Citation2016: 265f.). It was also the Speakers’ Conference that, following the outlines provided in the Europol regulation, took the lead on establishing the Joint Parliamentary Scrutiny Group.

Thus, this mode of EU decision making is very much marked by the competing institutional interests of the EP, on the one hand, and the national parliaments, on the other. Still, eventually, the parliaments seem to have found ways to settle their disagreements and been able to agree on a set of procedures to organise the terms of their cooperation.

Discussion and conclusion

Extending the analysis of the contestation of EU decision making beyond the ordinary legislative procedure reveals its complexity as a polity. The demoi-cratic EU needs multiple modes of decision making. The examination of four decision-making modes strongly suggests that the mode of decision making (and the institutions and balance between European and national powers that it involves) matters for the way that political contestation gets structured (). Each policy mode comes with its own structure of political contestation. Notably, once we extend the scope of analysis beyond the Brussels-based institutions, it becomes apparent that national divisions remain prominent throughout and that at times EU contestation even risks getting bogged down in inter-institutional fights (as in the initial attempts to set up inter-parliamentary conferences). The pre-eminence of national divisions is particularly apparent in the more intergovernmental modes of ‘executive decisions’ and ‘policy coordination’.

Table 1. EU decision-making modes and their structure of parliamentary contestation.

Still, the potential for transnational contestation appears to increase as decision-making modes become more institutionalised. Most obviously, that is the case in EU legislation, where the EP is the main arena where national divisions have become transcended. Still, also in EU legislation, national divisions enter the game again through the other institutions involved in the legislative process. Notably, the way the Early Warning Mechanism has focussed the involvement of national parliaments on the issue of subsidiarity has not helped to build coalitions between national parliaments and the EP, even if we see some signs of transnational ideological considerations in the way that national parliaments coordinate among each other.

In the case of the establishment of inter-parliamentary conferences, we have seen something of a learning curve. Initially, contestation developed along rather antagonistic inter-institutional lines, opposing in particular the national parliaments against the EP. However, in the last few years, some kind of settlement seems to have been reached, especially as the EU Speakers’ Conference has adopted the role of arbitrator. In contrast, while one can discern the potential and mutual benefits of cross-parliamentary coalition building in EU policy coordination (Fasone Citation2019), the evidence so far rather points towards some form of peaceful co-existence than to genuine co-scrutiny.

From a normative perspective, the finding that, on the whole, national division lines remain very difficult to transcend, and to some extent need to be taken as a natural ingredient of any political process in the EU, reinforces earlier calls that the demoi-cratic character of the EU requires its politics to be domesticated by national parliaments (Kröger and Bellamy Citation2016). However, if national domestication implies that the lines of contestation fully intersect with the institutional divisions, it will be very hard to appreciate any decisions that have genuine European implications. Hence, the present analysis suggests that all EU modes of decision making require at least some interlocking and mutual awareness between the parliamentary arenas of contestation to capture the transnational features of the decision-making process (cf. Piattoni and Verzichelli Citation2019).

The review of the decision-making modes indicates that such interlocking has effectively been secured in EU legislation and that parliaments have gone through a steep learning curve in establishing inter-parliamentary conferences. While it makes sense for national parliaments to remain rather selective in their engagement in EU legislation, they can make a difference if they want to and manage to coordinate their actions.

The bigger challenge lies in the contestation of EU executive decisions and policy coordination. There, the primary parliamentary institutions remain at the national level. Yet, their authority has been compromised because of the European context in which their governments are committed. As a consequence, parliamentary engagement has been reduced or, at least, limited to a rather narrow national focus in which the transnational impacts of decisions tend to be ignored. Thus, in EU policy coordination, the potential for trans-institutional coordination remains under-exploited and for EU executive decisions it is even harder to think of ways in which contestation across – rather than between – parliaments might be facilitated.

Obviously, the empirical analysis has remained exploratory. So far, it is only rarely that we grasp how a political decision reverberates through the EU as a whole. Even for the most publicised cases, like the posted workers directive or the recent Recovery and Resilience Facility, impressions from national parliaments often remain anecdotical and incomplete. For a better understanding of the structure of contestation across EU parliaments, we both need case studies that succeed in comprehensively covering parliamentary responses of EU decisions as well as the development of measures of the structure of contestation that hold across parliaments as well as across modes of decision making. Systematic comparisons would allow us to identify more sophisticated models of the way that contestation interacts along different ideological dimensions and between parliamentary sites, and to track the overall cohesion of the EU’s Multilevel Parliamentary Field. By laying out some first conceptualisations, models and preliminary analyses, this article has aspired to offer an invitation for such research that analyses the contestation of EU decisions beyond the European institutions.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this paper have been presented at workshops at the Institute for European Integration Research in Vienna (25–26 October 2018) and the University of Luxembourg (3–4 October 2019). I thank the participants, and in particular Olga Eisele, Katrin Auel, Katarzyna Granat and Katharina Meissner, for their helpful comments. Furthermore, the paper has benefitted from invaluable comments from Valentin Kreilinger, Alvaro Oleart and two anonymous reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ben Crum

Ben Crum is Professor of Political Science at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. He researches how processes of internationalisation change established practices and understandings of democracy and solidarity. He is the author of Learning from the EU Constitutional Treaty (Routledge, 2012) and co-editor (with John Erik Fossum) of Practices of Inter-Parliamentary Coordination in International Politics (ECPR Press, 2013). Most recently, his research articles have appeared in Political Studies, European Security, and the Journal of European Public Policy. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 Cf. Wallace (Citation2005), who distinguishes five EU policy modes: a traditional Community method, the regulatory mode, the EU distributional mode, policy coordination, and intensive transgovernmentalism.

References

- Adler-Nissen, Rebecca (2017). ‘Are we “Nazi Germans” or “Lazy Greeks”? Negotiating International Hierarchies in the Euro Crisis’, in Ayşe Zarakol (ed.), Hierarchies in World Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 198–218.

- Auel, Katrin, and Thomas Christiansen (2015). ‘After Lisbon: National Parliaments in the European Union’, West European Politics, 38:2, 261–81.

- Auel, Katrin, Olivier Rozenberg, and Angela Tacea (2015). ‘Fighting Back? And, If So, How? Measuring Parliamentary Strength and Activity in EU Affairs’, in Claudia Hefftler, Christine Neuhold, Olivier Rozenberg and Julie Smith (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of National Parliaments and the European Union. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 60–93.

- Bellamy, Richard (2013). ‘An Ever Closer Union among the Peoples of Europe’: Republican Intergovernmentalism and Demoicratic Representation within the EU’, Journal of European Integration, 35:5, 499–516.

- Benz, Arthur (2013). ‘An Asymmetric Two-level Game. Parliaments in the Euro Crisis’, in B. Crum and J. E. Fossum (eds.), Practices of Inter-Parliamentary Coordination in International Politics: The European Union and Beyond. Colchester: ECPR Press, 125–40.

- Bickerton, Chris, Dermot Hodson, and Uwe Puetter (2015). ‘The New Intergovernmentalism: European Integration in the Post-Maastricht Era’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 53:4, 703–22.

- Bormann, Nils-Christian, and Thomas Winzen (2016). ‘The Contingent Diffusion of Parliamentary Oversight Institutions in the European Union’, European Journal of Political Research, 55:3, 589–608.

- Buzogány, Aron (2013). ‘Learning from the Best? Interparliamentary Networks and the Parliamentary Scrutiny of EU Decision Making’, in Ben Crum and John Erik Fossum (eds.), Practices of Inter-Parliamentary Coordination in International Politics: The European Union and Beyond. Colchester: ECPR Press, 17–32.

- Cheneval, Francis, and Frank Schimmelfennig (2013). ‘The Case for Demoicracy in the European Union’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 51:2, 334–50.

- Closa, Carlos, and Aleksandra Maatsch (2014). ‘In a Spirit of Solidarity?’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 52:4, 826–42.

- Cooper, Ian (2013). ‘Deliberation in the Multilevel Parliamentary Field: The Seasonal Workers Directive as a Test Case’, in Ben Crum and John Erik Fossum (eds.), Practices of Inter-Parliamentary Coordination in International Politics: The European Union and Beyond. Colchester: ECPR Press, 51–67.

- Cooper, Ian (2015). ‘A Yellow Card for the Striker: National Parliaments and the Defeat of EU Legislation on the Right to Strike’, Journal of European Public Policy, 22:10, 1406–25.

- Cooper, Ian (2016). ‘The Interparliamentary Conference on Stability, Economic Coordination and Governance in the European Union (the ‘Article 13 Conference’)’, in Nicola Lupo and Cristina Fasone (eds.), Interparliamentary Cooperation in the Composite European Constitution. Oxford: Hart Publishing, 247–68.

- Cooper, Ian (2017). ‘The Emerging Order of Interparliamentary Cooperation in the Post-Lisbon EU’, in Davor Jančić (ed.), National Parliaments after the Lisbon Treaty and the Euro Crisis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 227–46.

- Cooper, Ian (2019). ‘National Parliaments in the Democratic Politics of the EU: The Subsidiarity Early Warning Mechanism, 2009–2017’, Comparative European Politics, 17:6, 919–39.

- Crespy, Amandine, and Katarzyna Gajewska (2010). ‘New Parliament, New Cleavages after the Eastern Enlargement? The Conflict over the Services Directive as an Opposition between the Liberals and the Regulators’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 48:5, 1185–208.

- Crum, Ben (2018). ‘Parliamentary Accountability in Multilevel Governance: What Role for Parliaments in Post-Crisis EU Economic Governance?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:2, 268–86.

- Crum, Ben, and John E. Fossum (2009). ‘The Multilevel Parliamentary Field: A Framework for Theorizing Representative Democracy in the EU’, European Political Science Review, 1:2, 249–71.

- Crum, Ben, and John Erik Fossum (eds.). (2013). Practices of Inter-Parliamentary Coordination in International Politics: The European Union and Beyond. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Crum, Ben, and Eric Miklin (2013). ‘Interparliamentary Coordination in Single Market Policy-Making: The EU Services Directive’, in Ben Crum and John Erik Fossum (eds.), Practices of Inter-Parliamentary Coordination in International Politics: The European Union and Beyond. Colchester: ECPR Press, 71–85.

- Dawson, Mark (2015). ‘The Legal and Political Accountability Structure of “Post‐crisis” EU Economic Governance’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 53:5, 976–93.

- Fasone, Cristina (2016). ‘Ruling the (Dis-)Order of Interparliamentary Cooperation? The EU Speakers’ Conference’, in Nicola Lupo and Cristina Fasone (eds.), Interparliamentary Cooperation in the Composite European Constitution. Oxford: Hart Publishing, 269–89.

- Fasone, Cristina (2019). ‘Economic Governance: A Field of “Conflictual Cooperation”?’, paper presented at the Workshop on ‘Inter-parliamentary Relations in the post-Lisbon European Union’, University of Luxembourg (3-4 October 2019).

- Fasone, Cristina, and Nicola Lupo (2016). ‘Introduction. Parliaments in the Composite European Constitution’, in Nicola Lupo and Cristina Fasone (eds.), Interparliamentary Cooperation in the Composite European Constitution. Oxford: Hart Publishing, 1–19.

- Fromage, Diane, and Valentin Kreilinger (2017). ‘National Parliaments' Third Yellow Card and the Struggle over the Revision of the Posted Workers Directive’, European Journal of Legal Studies, 10:1, 125–60.

- Gattermann, Katjana, and Claudia Hefftler (2015). ‘Beyond Institutional Capacity: Political Motivation and Parliamentary Behaviour in the Early Warning System’, West European Politics, 38:2, 305–34.

- Hagemann, Sara, and Bjørn Høyland (2008). ‘Parties in the Council?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 15:8, 1205–21.

- Hagemann, Sara, Stefanie Bailer, and Alexander Herzog (2019). ‘Signals to Their Parliaments? Governments’ Use of Votes and Policy Statements in the EU Council’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 57:3, 634–50.

- Herranz-Surrallés, Anna (2014). ‘The EU’s Multilevel Parliamentary (Battle)Field: Inter-Parliamentary Cooperation and Conflict in Foreign and Security Policy’, West European Politics, 37:5, 957–75.

- Herranz-Surrallés, Anna (2019). ‘Paradoxes of Parliamentarization in European Security and Defence: When Politicization and Integration Undercut Parliamentary Capital’, Journal of European Integration, 41:1, 29–45.

- Hix, Simon, Abdul Noury, and Gerard Roland (2007). Democratic Politics in the European Parliament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Huff, Ariella (2015). ‘Executive Privilege Reaffirmed? Parliamentary Scrutiny of the CFSP and CSDP’, West European Politics, 38:2, 396–415.

- Jančić, Davor (2016). ‘National Parliaments and EU Fiscal Integration’, European Law Journal, 22:2, 225–49.

- Jančić, Davor (2017). ‘EU Law’s Grand Scheme on National Parliaments: The Third Yellow Card on Posted Workers and the Way Forward’, in Davor Jančić (ed.), National Parliaments after the Lisbon Treaty and the Euro Crisis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 141–58.

- Kreilinger, Valentin (2015). ‘Asymmetric Parliamentary Powers: The Case of the Third Rescue Package for Greece’, blog post, Jacques Delors Institute, 19 August, www.delorsinstitut.de/en/allgemein-en/asymmetric-parliamentary-powers-the-case-of-the-third-rescue-package-for-greece.

- Kreilinger, Valentin (2018). ‘From Procedural Disagreements to Joint Scrutiny? The Interparliamentary Conference on Stability, Economic Coordination and Governance’, Perspectives on Federalism, 10:3, 155–83.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter (2016). ‘The Politicization of European Integration’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 54:S1, 32–47.

- Kröger, Sandra, and Richard Bellamy (2016). ‘Beyond a Constraining Dissensus: The Role of National Parliaments in Domesticating and Normalising the Politicization of European Integration’, Comparative European Politics, 14:2, 131–53.

- Maatsch, Aleksandra (2017). ‘Effectiveness of the European Semester: Explaining Domestic Consent and Contestation’, Parliamentary Affairs, 70:4, 691–709.

- Malang, Thomas, Laurence Brandenberger, and Philip Leifeld (2019). ‘Networks and Social Influence in European Legislative Politics’, British Journal of Political Science, 49:4, 1475–98.

- Matthijs, Matthias, and Kathleen McNamara (2015). ‘The Euro Crisis’ Theory Effect: Northern Saints, Southern Sinners, and the Demise of the Eurobond’, Journal of European Integration, 37:2, 229–45.

- Miklin, Eric (2017). ‘Beyond Subsidiarity: The Indirect Effect of the Early Warning System on National Parliamentary Scutiny in European Union Affairs’, Journal of European Public Policy, 24:3, 366–85.

- Nicolaïdis, Kalypso (2004). ‘The New Constitution as European “Demoi-Cracy”?’, Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 7:1, 76–93.

- Nicolaïdis, Kalypso (2013). ‘European Demoicracy and Its Crisis’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 51:2, 351–69.

- Peters, Dirk, Wolfgang Wagner, and Cosima Glahn (2013). ‘Parliaments at the Water’s Edge: The EU’s Naval Mission Atalanta’, in Ben Crum and John Erik Fossum (eds.), Practices of Inter-Parliamentary Coordination in International Politics: The European Union and Beyond. Colchester: ECPR Press, 105–23.

- Piattoni, Simona, and Luca Verzichelli (2019). ‘Revisiting Transnational European Consociationalism: The European Union a Decade after Lisbon’, Swiss Political Science Review, 25:4, 498–518.

- Pollak, Johannes, and Peter Slominski (2003). ‘Influencing EU Politics? The Case of the Austrian Parliament’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 41:4, 707–29.

- Rasmussen, Mette Buskjaer (2018). ‘Accountability Challenges in EU Economic Governance? Parliamentary Scrutiny of the European Semester’, Journal of European Integration, 40:3, 341–57.

- Raunio, Tapio (2005). ‘Much Ado about Nothing? National Legislatures in the EU Constitutional Treaty’, European Integration online Papers 9, http://eiop.or.at/eiop/texte/2005-009a.htm, visited 11 August 2017.

- Ruiz de Garibay, Daniel (2013). ‘Coordination Practices in the Parliamentary Control of Justice and Home Affairs Agencies: The Case of Europol’, in Ben Crum and John Erik Fossum (eds.), Practices of Inter-Parliamentary Coordination in International Politics: The European Union and Beyond. Colchester: ECPR Press, 87–103.

- Schade, Daniel (2018). ‘Limiting or Liberating? The Influence of Parliaments on Military Deployments in Multinational Settings’, British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 20:1, 84–103.

- Verdun, Amy, and Jonathan Zeitlin (2018). ‘Introduction: The European Semester as a New Architecture of EU Socioeconomic Governance in Theory and Practice’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:2, 137–48.

- Wallace, Helen (2005). ‘An Institutional Anatomy and Five Policy Modes’, in Helen Wallace, William Wallace and Mark Pollack (eds.), Policy-Making in the European Union. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 49–90.

- Wessels, Wolfgang, Olivier Rozenberg, Mirte van den Berge, Claudia Hefftler, Valentin Kreilinger, and Laura Ventura (2013). ‘Democratic Control in the Member States of the European Council and the Eurozone Summits’, Study for the European Parliament’s Committee on Constitutional Affairs, document PE 474.392.

- Zeitlin, Jonathan, Francesco Nicoli, and Brigid Laffan (2019). ‘Introduction: The European Union beyond the Polycrisis? Integration and Politicization in an Age of Shifting Cleavages’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:7, 963–76.