Abstract

This paper analyses the institutions associated with government termination in parliamentary systems: no-confidence and confidence motions, and the early dissolution of the parliament. We consider constitutional texts for all European countries between 1800 and 2019 and identify two broad trends: (1) the constitutionalisation of practices that have first emerged as the result of strategic interactions between the government and the parliament; (2) the tendency towards protecting both the executive and the parliament from mutual interference. While the first tendency has culminated with an almost universal constitutionalisation of the principle of parliamentarism in European constitutions, the second led to the protection of executives and the extension of effective legislative terms. We suggest that these constitutional developments are associated with the stabilisation of parliamentarism after World War II and conclude that although parliamentarism remains a flexible system, contemporary regimes do not function like their forebears did in the 19th century.

There are currently two fundamentally different ways to organise a political system in countries that seek to establish and sustain democracy: presidential and parliamentary. In presidential systems, both the head of the government and the legislature are independently and popularly elected for a fixed term in office. In parliamentary systems, the legislature, but not the government, is popularly elected: the government remains in office as long as it is at least tolerated by a majority in the parliament. In this sense, governments in parliamentary systems are politically responsible to the parliament in a way that they are not in presidential systems.Footnote1 This is why we also refer to parliamentary systems as systems with assembly confidence or government responsibility.

Today, constitutions that prescribe government responsibility are more popular than presidential constitutions. Between 1974 and 2008, there have been 80 transitions to democracy; 37 of these were in countries that were experiencing democracy for the first time. Of the countries where democracy was first implanted in 1974 or after, 62% chose a parliamentary constitution.Footnote2 Thus, the tendency among recent democratising countries has been to choose a constitution that requires governments to maintain the support of a majority in parliament, even if only tacitly.

In his groundbreaking comparison of presidential and parliamentary systems, Juan Linz famously distinguished between regime and government instability. For him, policy crises that in parliamentary systems were resolved through the removal of the government rapidly escalated into regime crises in presidential system. On the basis of this distinction, Linz (Citation1994) provided what became the first, and certainly the most accepted, institutionalist explanation for the instability of democracy experienced by Latin American countries. For him, the fact that executive and legislature served for a fixed term, a feature of presidentialism that advocates believed would stabilise the regime, should be seen as a problem and not an advantage. Fixed terms meant that in case of deadlock between the two powers, there would be no institutional solution that would force one of these powers to budge. President and legislature could, without immediate risk of losing office, stick to their guns until the next scheduled election while the country suffered the consequences of policy paralysis. The fact that the president and congress relied on separate democratic legitimacies – independent elections with different constituencies – would only make a bad situation worst; for it implied that not only were the executive and the legislature protected in their tenure, they would likely have different policy preferences as their constituencies were not the same.

Parliamentarism, in contrast, was seen as a flexible system in the sense that it provides an easy-to-invoke and relatively cheap mechanism for resolving conflicts between the executive and the legislative powers: the withdrawal of parliamentary confidence in the government. This institution, according to Linz and many others, represents a ‘built-in’ mechanism of conflict resolution that is not available in presidentialism. In the event of a disagreement, parliament replaces the government, presumably with one more aligned with its own preferences (Linz Citation1994; Stepan and Skach Citation1993). In fact, according to a widely employed model, parliamentarism should be seen as a single and continuous chain of delegation and accountability, starting with the voters and proceeding to the parliament, the government and the bureaucracy (Strøm Citation2000). In this model, the essential mechanism that keeps all interests neatly aligned is the possibility that principals can remove their agents: voters can remove members of parliament in general elections, and members of parliament can vote a government out of office through a vote of no confidence. In this sense, with few exceptions (e.g. Huber Citation1996b), scholars of parliamentarism assume a structurally co-operative, or at least non-conflictual, relationship between governments and parliaments; disagreements are temporary, corrected by the built-in conflict resolution mechanism. In this sense, a lot is made to ride on this one single institution, the mere presence of which should be sufficient to guarantee the peaceful operation and survival of the political system.

In this paper we show that the stability of parliamentarism as a political regime was not achieved until after World War II. The stylised history of parliamentarism is one of slow evolution, of small adjustments by actors who responded strategically to one another in the face of changing material conditions and new political forces. In line with this view, parliamentarism has been primarily seen as a regime form that emerged from a series of compromises, and not as a doctrine and theoretical model (Congleton Citation2011; von Beyme Citation1987, Citation2014). Although it is true that a few countries experienced a relatively smooth process of transition from a constitutional monarchy to a parliamentary democracy, this has not been the modal pattern. Historically, parliamentarism has had an uneven trajectory. Before WWII, both regime and government crises were frequent and the alignment of interests between the government and a parliamentary majority was anything but automatic.

Additionally, we show that parliamentarism in Europe has changed in at least two significant ways, which likely contributed to its post-WWII stabilisation. First, practices that had been left undefined in the first decades of the regime’s existence became constitutionalised. Second, constitutionalisation entailed the clarification of procedures and the limitation of the ways governments and parliaments can affect each other’s existence. This is true of all countries, even the ones where parliamentarism had more or less evolved over time as the product of interactions between monarchs, governments, and parliaments. Together, these changes make for a constitutional system that lacks some of the flexibility that has been traditionally seen as its hallmark. Interestingly, it is as these changes were introduced into national constitutions that we saw the consolidation of parliamentarism in countries where its history had been anything but stable.

Our analysis is based on the constitutions and relevant amendments for all European countries since 1800.Footnote3 We focus on Europe because this is where parliamentarism was born and where almost all countries today have constitutions based on assembly confidence. Many of the constitutional trends we discuss below were set in motion after some countries in the region experienced profound crises of government and/or regime. The diagnoses generated to explain these crises almost invariably implicated the institutional structure, if not as the cause, at least as the facilitator of the turmoil. Our goal is, on the one hand, to document constitutional changes in European parliamentary systems and, on the other hand, to show its stabilisation, as reflected in the absence of regime crises, longer prime ministerial tenure in office, and parliaments that serve a larger proportion of their constitutional term. It would be disingenuous for us to pretend we do not believe that the two events – constitutional protections of executives and parliaments against mutual encroachment and the stability of parliamentarism as a regime – may be causally related. Since we could not meaningfully test for a causal relationship, here we refrain from making such claims. Our analysis, however, strongly suggests that government responsibility as manifested in the assembly confidence mechanism, the very principle that defines parliamentarism, is not sufficient to generate stable governance. Much more needs to be regulated if the principle is to operate smoothly.

The historical record

We understand parliamentarism to be a system where the government is responsible to the legislature. As a minimum, responsibility means that the government must be tolerated by the legislature, but not necessarily explicitly supported by it; if not tolerated, the government can be voted out of office by the legislature. Even if in some European countries parliamentarism evolved relatively slowly, the system that they now possess can hardly be seen today as the result of an evolutionary process of transformation of constitutional monarchies into parliamentary democracies. Most of the countries where parliamentarism is said to have evolved as the product of interactions between monarchs, ministers, and parliaments have adopted parliamentary constitutions later on. Sweden, for instance, had an informal breakthrough of parliamentarism in 1917, and adopted a new constitution in 1974 with rules for executive–legislative relations that in many respects changed the practice that had evolved on the basis of the 1809 constitution. In Denmark, the first parliamentary government was appointed in 1901, but the principle of parliamentarism was formally introduced only in the 1953 constitution. Significant reforms, and the explicit constitutionalisation of parliamentarism, also happened in Belgium, the Netherlands, and Norway, some of them quite recently. This means that European parliamentarism today is almost exclusively based on explicit constitutional designs, implemented at moments of intentional constitution making.

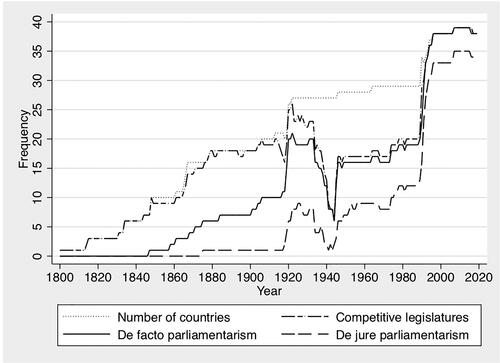

The process of formal constitutionalisation of parliamentarism can be observed in , which traces its evolution in Europe since 1800. For each year we record the number of independent countries, the number of countries with a minimally competitive legislature, the number of countries where parliamentarism exists de facto, and the number of countries where it is inscribed in a written constitution. We define a minimally competitive legislature as (1) a body that claims to perform some representative functions; (2) where individuals rather than classes or estates are represented; (3) which is at least partly elected by a subset of the population; (4) voters are given a choice of candidates at election; and (5) in which more than one political party or group participates.Footnote4 Note that our definition of competitive legislature does not require mass suffrage. What matters is the existence of individual representation and, strictly speaking, that there is a larger number of people voting than running for office. As important as the extension of suffrage has been for the democratisation of European countries, parliamentarism started to develop even under a system of restricted or oligarchic competition. We consider that parliamentarism exists de jure when the constitution explicitly states that governments can be removed from office through a vote of censure or no confidence. Parliamentarism exists de facto when we find evidence that governments that are no longer tolerated by a legislative majority are removed from office or not even appointed into office in the first place. Competitive legislatures and parliamentarism do not require and we do not assume the existence of democracy. Although today all European democracies (except Cyprus and Switzerland) are, in a pure form or in combination with directly elected presidents, parliamentary, in many countries, governments became responsible to parliaments well before elections were based on mass suffrage and led to alternation in power.Footnote5

It is apparent from that the parliamentarization of European countries is a relatively recent phenomenon. While most European countries in the 19th century had a minimally competitive legislature, at least half of them lacked governments subject to assembly confidence. The number of countries where parliamentarism existed de facto steadily increased until the beginning of WWI, although only a small number of constitutions explicitly provided for an executive that could be removed from office by the legislature. The end of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires led to the creation of several new countries, many of which adopted parliamentarism, both de facto and in their written constitutions. These regimes, as we know and confirms, did not last very long: by 1944, the number of European countries that had a competitive legislature was as low as it had been one hundred years earlier. It is only after WWII that we see that the existence of a competitive legislature implies parliamentarism; and it is only in the middle of the 1990s that all countries in Europe had a competitive legislature, with governments that were de facto subject to assembly confidence. Today, only Iceland, Luxembourg, and the United Kingdom lack written constitutional provisions that explicitly state that the government must have the confidence of parliament in order to stay in office.

The constitutionalisation of parliamentarism was associated with changes in the stability of regimes, executives, and legislatures. masks a large degree of turmoil, which we fail to see as we look to the past from today’s vantage point. Table A1 in the online appendix lists the European cases that are part of our dataset. This table includes 44 countries, of which five are historical, encompassing 80 spells of minimally competitive legislatures. Seventeen countries experienced 21 spells of competitive legislatures that were initiated in the 19th century (we start observation in 1801, with the creation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland). Ten additional countries had their first experience with competitive legislatures in the 20th century, prior to the outbreak of WWII, for a total of 20 spells. Thus, by 1939, 28 countries had experienced competitive legislatures. In ten of these – Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Great Britain, Ireland, Iceland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden – the legislature remained open and competitive until today, with relatively short periods of foreign occupation in five of these countries during WWI and/or WWII. In the remaining 17 countries, competitive legislatures were closed 31 times: two times in five countries (Austria, France, Germany, Romania and Turkey), three times in other three (Greece, Portugal and Spain), and four times in one (Bulgaria). However, of the thirty-six countries that established or re-established competitive legislatures after WWII, only three were closed in two countries, Greece in 1967 and Turkey in 1961 and 1982. To the extent that we conceive of regimes in terms of the presence or absence of a national competitive legislature, Europe in the post-WWII era is quite different from the Europe that existed prior to the war.

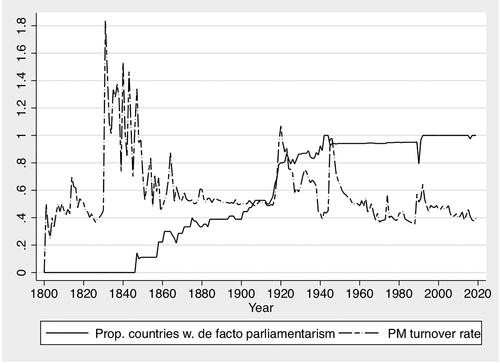

presents the proportion of countries with de facto parliamentarism and the average turnover rate for prime ministers in each year since 1800. Prime minister turnover is defined as the yearly rate with which PMs are replaced in the course of a spell of competitive legislature.Footnote6 The contrast between the left and the right parts of the picture is stark. Throughout the 19th century, when no more than 40% of the countries practiced parliamentarism, the rate of PM turnover was high, which is consistent with the idea that monarchs freely appointed and dismissed PMs. As de facto parliamentarism expanded in Europe, PM turnover decreased in tandem. Eventually, by the end of the 19th century, PMs changed once every two years (turnover rate around 0.5), while about 40% of the almost 20 countries in Europe were de facto parliamentary. On the other side of the figure we see that, after increasing during the unstable inter-war period, turnover declined to levels similar to pre-WWI, with short-term spikes related to the re-establishment of parliamentarism after WWII and the end of Communism in 1990. At the same time, however, all countries with a competitive legislature are parliamentary. Thus, as the number of parliamentary countries increased, the tenure of PMs became more stable; after WWII, PMs changed once every 2.5 years.

Figure 2. Prime Minister turnover and proportion of countries with de facto parliamentarism by year, 1800–2019.

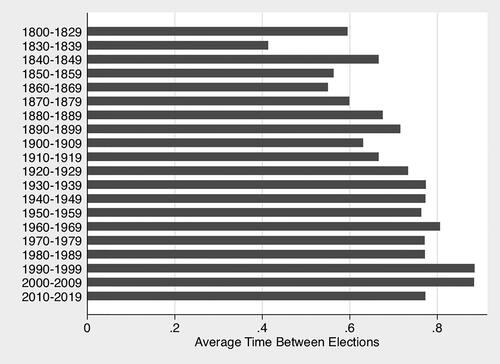

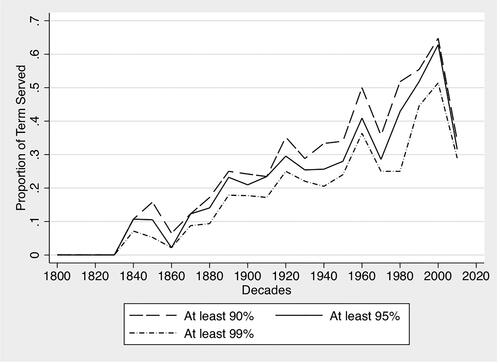

The life of legislatures, too, has been extended with the adoption of parliamentarism, particularly after WWII. depicts the proportion of the constitutional legislative term that European national assemblies served, averaged for each decade since 1800. Legislatures in the European constitutional monarchies of the 19th century rarely completed their terms. But the effective length of legislative terms increased since then: in the 19th century parliaments with 4-year terms served 2.4 years on average, while in the 20th they served 3.2 years; 5-year parliaments served 3 years of their terms in the 19th century, but 4 years after WWII. Thus, just like with prime ministerial tenures, the life of legislatures has become longer.

Figure 3. Duration of parliaments as a proportion of constitutionally mandated term, decade averages, 1800–2019.

Contemporary parliamentary systems, thus, have adopted written constitutions, prime ministers have longer tenures, and parliaments serve a higher proportion of their constitutional term. These changes are associated with the constitutional developments that have taken place regarding the mechanisms of government termination in parliamentary systems: the no-confidence vote, the confidence vote, and assembly dissolution. We cannot claim that these changes caused the stabilisation of parliamentarism. But they are temporally correlated with it and, ultimately, amount to a blueprint of parliamentarism that is not quite the same as the ‘classic’ form, in which the system of ‘mutual interdependence’ (Stepan and Skach Citation1993) was left unregulated. The need and intention to codify parliamentary practices was already apparent after WWI. As the legal scholar Mirkine-Guetzévitch (Citation1950: 610) noted, ‘the authors of European constitutions after 1919 adopted a variant of the French parliamentary regime, but one that was systematised, dogmatised, and rationalised; and the parliamentarism of the 19th century, an entirely customary moving ensemble of empirical rules, changes into a doctrine homogeneous and rigid.’ Yet, rather than the rigidity of the constitution, what mattered were the specific provisions introduced to regulate the conditions for the formation of governments and for engaging their political responsibility, having in mind a primary concern with government stability and in direct dialogue with their perception of the political crises of the inter-war period and the aftermath of WWII.Footnote7 Today, parliamentary constitutions are still characterised by a degree of flexibility that distinguishes them from presidential ones. But this flexibility is regulated, with significant restrictions on the ability of legislative majorities to remove governments, and on the ability of governments to dismiss parliaments. In a way, parliamentarism can no longer be seen as a system based on spontaneous equilibria and immediate adjustments to shocks; actors, now, are forced to be more patient.

The process we document in this paper raises two issues of broader interest. First, the constitutional changes that underly the trends detailed in this section are not exclusive to parliamentarism. In fact, presidential constitutions also went through significant changes, albeit later in time than the changes observed in parliamentary ones. These changes have also been related to the stabilisation of presidential systems in Latin America, the region where presidentialism was the rule and where chronic governmental (and regime) instability prevailed until the re-establishment of competitive legislatures in the 1980s (Cheibub et al. Citation2014; Figueiredo and Limongi Citation2000; Negretto Citation2013). Like the process that led to the ‘rationalization of parliamentarism’ in post-WWII Europe, much of the impetus for reforming presidential constitutions during the last decades of the 20th century was provided by the crises that had led to the establishment of the military dictatorships of the 1960s and 1970s. Yet, because the constitutional problems perceived as having contributed to the crises were specific to each form of government, the solutions were also distinct. Second, the constitutional changes that were introduced in both parliamentary and presidential constitutions are often seen as having contributed to a strengthening of the executive to the detriment of legislatures. Yet, an alternative perspective sees them as ways to solve the intrinsic tension of democratic regimes, namely, the requirement that governments, political parties, and legislators must cooperate with one another in order to govern and yet compete to gain votes in periodic elections.

Parliamentary confidence and government termination

Apart from the expiration of the legislative term, there are three ways a parliamentary government, but not the regime, can end: the government resigns because it loses or fears to lose a no confidence vote; the government resigns because it loses a vote of confidence that it requested from parliament; the government resigns because the assembly is dissolved before the end of its constitutional term. In this section we discuss the first two institutions, which embody the notion of government responsibility; we will discuss parliamentary dissolutions in the following section. The two institutions we focus on here share the word ‘confidence’, even though they are drastically distinct. To avoid confusion, we emphasise the difference between the two: the no-confidence vote is mainly an instrument of the opposition and implies a censure of the government; the confidence vote is an instrument of the incumbent, who requests the parliament to affirm its confidence on the government.

No-confidence or censure vote

The requirement that a government resign if it loses a no-confidence vote is the quintessential parliamentary institution, and the only one that distinguishes parliamentarism from other forms of government. It is through the no-confidence vote that the idea of parliamentary responsibility – the notion that a government must be at least tolerated by a legislative majority – becomes reality. The no-confidence procedure is simple: a group of legislators proposes a motion expressing its lack of confidence in the government; the motion is voted by the legislature and if a majority approves it, the government must resign. Today, most parliamentary constitutions contain an explicit clause allowing a group of legislators to express its lack of confidence in the government and requiring that the government resign as a result. This, of course, was not always the case and there are some countries that have undeniably functioned as a parliamentary democracy before formally constitutionalising the no-confidence vote.

The vote of no confidence is an instrument of the opposition and, in this sense, is a negative institutional tool. It is proposed by a group of legislators who believe the government, for some reason, must be removed from office. It is approved if a majority supports the removal of the government. As can be easily imagined, the majority that supports the removal of the government need not agree on a replacement. And to the extent that the proposal and approval of no-confidence motions are relatively costless, it is conceivable that it may become an instrument of obstruction in the hands of the opposition, rather than an instrument to resolve conflicts between the legislative majority and the executive. Perhaps the best example of the use of no-confidence motions as a strategy of obstruction rather than of conflict resolution is the French 3rd and 4th Republics.Footnote8

The historical record demonstrates that, left unregulated, the no-confidence vote can at times encumber the normal operation of the political system. The convention requiring that governments be appointed that are at least tolerated by a legislative majority is so simple and intuitive when considered in the abstract that we tend to forget all the ambiguities that it involves: What must happen for it to be unequivocal that the government no longer has the confidence of the parliament? Is the defeat of a government-sponsored bill sufficient to convey it? If so, all bills or just some of them? Which ones? Who can initiate a no confidence motion? What is the majority necessary for it to pass? Much of the politics in the early years of parliamentarism revolved around identifying the (lack of) correspondence between the government and the majority of the legislature, and the attempts to either bring the two into line or resist pressures to do so.

We identify two changes that imply an attempt to regulate the no-confidence procedure and avoid the crises provoked by its ambiguity. First, after a period of intense conflict and political instability, many countries made the details of the no confidence mechanism explicit and, at the same time, increased the costs of initiation and approval. No-confidence clauses went from being vague and implicit to a coherent set of procedures spelling out details of how to use the institution. These include rules about the minimal number of legislators necessary to initiate a no-confidence motion; the number of motions that can be initiated in any given session, or the number of times any legislator can initiate one; the amount of time required to elapse before a motion can be voted on; and, importantly, the size of the majority required to approve no-confidence in the government. These regulations, including the move from simple to absolute majority (as, for instance, in Greece, Portugal, and Sweden), all aimed to protect governments and make them more stable.

Second, a number of countries adopted a ‘constructive’ no-confidence procedure, which is harder to be used primarily as an instrument of legislative obstruction. Invented in Germany, this institution was explicitly conceived as a way to avoid what was seen as the abuses of the regular no-confidence vote during the Weimar Republic (Lindseth Citation2004). It requires that any successful motion to remove the government also indicate the head of the next government. By requiring that an alternative head of government be approved as the incumbent is rejected, the constructive no-confidence vote raises the cost for the opposition and prevents the formation of negative majorities, that is, majorities that can come together to oppose a government but not to support one: if one wants to oust the government one must be in a position to take over its reins. Currently there are six countries in Europe that require a constructive vote of no confidence for the legislative removal of the government: Germany, Spain, Hungary, Slovenia, Poland, and Belgium (Lento and Hazan Citation2020 in this issue; Tutnauer and Hazan Citation2020). Belgium also allows for a regular no-confidence motion to be voted on, but its approval does not lead to the resignation of the government. Rather, it implies that the King is allowed, if he so wishes, to dissolve the legislature and call early elections.

We know little systematically about the actual use of no-confidence votes. It is clear that in some countries the introduction of no-confidence motions is a frequent matter, although the vast majority of them are never successful. For example, Hazan (Citation2014) reports that 166 no-confidence motions were introduced in Austria since 1926, but none has ever been successful; there have been 26 in Portugal since 1976, but only one was successful. According to Hem and Wahl (Citation2018), there have been 64 motions since 1945 in Norway, and only one was approved in 1963. According to Stan (Citation2015), 25 censure motions were debated and voted on in Romania between 1989 and 2012, and only two were approved. Thus, no-confidence motions, regular or constructive, are seldom successful. The main goal of constructive votes of no confidence is to prevent the emergence of negative majorities. By design, it makes it harder for the opposition to use motions of censure primarily to obstruct legislative proceedings or to signal to voters the existence of policy differences with the government. While the constructive vote of no confidence technically does not prevent the opposition from introducing a censure motion even when it does not have the support to form an alternative government, such an action would lack the credibility necessary to serve as a useful signal to voters or perhaps to be even allowed into the legislative agenda.Footnote9 The small number of times governments are removed by a successful no-confidence vote, however, should not be seen as an indication that the procedure is innocuous; its true effect is to be found not so much in the number of times a government resigns after it loses a no-confidence vote, but in the number of times it resigns or adjusts its policies in anticipation of such a vote. Thus, in a manner that is quite general with respect to institutions, what matters is not the actual use or success of the no-confidence procedure, but the possibility of it being used at all.

Parliamentary constitutions have a grey area regarding what happens when governments resign, whether because of a loss in a parliamentary vote, a conflict among coalition partners, or the end of the legislative term. In some cases, governments that resign stay in power in a caretaker capacity until a new government comes into office. This is so even if the new government is only formed after new elections. In a few other cases, such as in Greece under the 1975 constitution, a new interim prime minister is appointed to serve for the duration of the transition between the old and the new government, which includes overseeing an election. What should happen after a government resigns is not always made explicit in constitutions, although an increasing number of them explicitly requires that resigning governments stay in power in an interim capacity until elections happen and/or a new government is appointed.

Studies of interim governments in parliamentary systems are scarce. Part of the reason for this is the presumption that interim governments do not really govern, that they are simply taking care of the government’s day-to-day operations, essentially paying the bills that are due. Under an interim government no new, certainly no new major, legislation is supposed to be introduced or considered, and no new appointments made. For this to be true, however, we have to assume that heads of interim governments willingly abide by this norm and refrain from using the instruments that are still at their disposal and which allow them to change the status quo without engaging the normal legislative process. Thus, the belief that interim governments ‘should’ not do much does not immediately imply that they are inactive and only act on trivial issues. Furthermore, even legislative activity is not brought to a halt under all interim governments. In their study of the long interim governments in Belgium during 2007–2008 (194 days) and 2010–2011 (541 days), Van Aelst and Louwerse (Citation2014) show that a total of 115 bills became law and that 353 roll-call votes were held on bills spanning most policy areas. For these reasons, we believe, the presumption about interim governments should be the opposite of what it is now: whoever is in the head of an interim government will seek to advance their interests and, to do so, will engage in actions that are likely to have important consequences both in terms of policy and in terms of the incumbent coalition's survival in office. In other words, it is important to pay attention to the actions these governments undertake instead of simply assuming them away as irrelevant.

The successful passage of a no-confidence motion opens up a number of possibilities, including whether parliament will be dissolved and elections called. If no elections are called, new formation attempts can take place, leading to a new or reformed coalition or, eventually, elections. If elections are called after the successful no-confidence motion, one of three alternatives happen: the incumbent government remains with full power, the incumbent government goes into caretaker mode, or a new caretaker government takes over. After the election, a new government forms, and that government may or may not be identical to the previous one. It is not difficult to see that the paths implied by these alternatives are fraught with ambiguities and open to much brinksmanship. As we stated before, more recent constitutions clarify these ambiguities and raise the bar for a successful removal of the government through a no-confidence procedure.

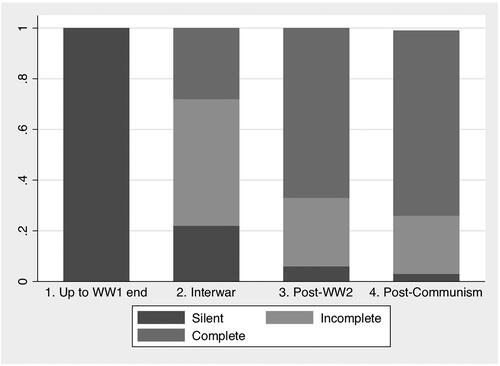

We classified the constitutions and relevant amendments of European countries into three groups according to the level of details they contain regarding the government’s political responsibility to parliament. The first group is composed of documents that were silent about political responsibility.Footnote10 The constitutions in this group generally contain provisions related to the criminal prosecution or impeachment of members of the government. Some of them contain a laconic statement to the effect that the government (or the ministers who compose the government) is ‘responsible’. We find no details about how responsibility is to be manifested and responsibility is, again, meant to be criminal and not political. Yet, the practice of assembly confidence started and, in some cases, continued for many years under these constitutions, albeit with significant ambiguities. In the second group we find constitutions in which provisions about assembly responsibility are present but incomplete. They contain some more or less detailed provisions about the expression of parliamentary (lack of) confidence in the government, but still leave a lot of what should happen implicit. Although they explicitly indicate that parliament can withdraw its confidence from the government, they do not always indicate how this can be done or with what consequences. In some of these cases, the decision rule can be inferred from the constitution’s stipulation regarding any decision by parliament. The problem is that even the general decision rule is not always made explicit. Finally, the third group is composed of constitutions with complete specification of the confidence procedure: Who can initiate it?Footnote11 Must a dedicated motion be introduced? What kind of majority is necessary for the motion to be approved? What happens if the motion is approved? Are there restrictions on the introduction of no-confidence motions?

The distribution of constitutions by time period is presented in . As can be seen, more recent constitutions tend to regulate explicitly and in detail the steps necessary for initiating a vote of no confidence, the rule to be used for approving it, and the consequence of a successful no-confidence vote. Whereas pre-WWI constitutions at best provided for the very basic statement of government responsibility, a large number of post WWII, and particularly post-Communist, constitutions provided for unambiguous and complete procedures. Constitutions written between 1946 and 2019 are overwhelmingly of the third type.

Two further observations can be made on the basis of the data that underlie . First, that in 21 out of 39 cases (54%) the constitutions that explicitly stipulate a rule for deciding on a vote of no confidence adopt an absolute majority rule, that is, they require the approval of 50% of all members of parliament. This, of course, makes it less likely that the government will be removed by the parliament than if no-confidence could be passed by a simple majority or a majority, of those present for the vote. Furthermore, of these, 19 emerged after 1945 and 14 after 1990. In eleven of these cases, the adoption of an absolute majority requirement comes after a failed experience of parliamentarism, in which no-confidence procedures were ambiguously formulated and the decision rule was a simple majority. These cases include Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Portugal, all of which experienced a parliamentary breakdown during the interwar period (or, in the case of Greece, also later). Similarly, the country that first instituted a constructive vote of no confidence – Germany – did so partly in reaction to the government instability of the Weimar Republic.

The second observation is that when the principle of assembly confidence becomes explicitly constitutionalised, the consequence of a successful no-confidence procedure is unambiguous: the government must resign. This represents a departure from the ‘classic’, British model, in which the prime minister, faced with a successful no-confidence vote, will not necessarily resign since she can advise the head of state to dissolve parliament instead. Thus, given that government resignation always follows a successful no-confidence vote, the removal of the government has been dissociated from the dissolution of the assembly. To the extent that this is true, we should observe a weaker correlation between government resignation and the occurrence of early elections in the more recent years than in the years during which parliamentary systems were being built. Because our dataset is organised by individual prime ministers, and not cabinets, we are not in a position to verify if this is the case. We will discuss assembly dissolution in the next section. For the moment it is sufficient to say, first, that these changes in the no confidence provisions have happened concurrently with a tendency towards the removal of individual discretion in bringing about an assembly dissolution. The result is the dissociation between parliamentary votes of no confidence and the occurrence of early elections. Second, the same combination of these two trends allows oppositions in parliamentary regimes to remove the government from office knowing that new elections will not follow inevitably.

Confidence vote

As we know, the confidence vote, as distinct from the no-confidence or censure vote, is an instrument of the government. It has received attention from political scientists as an institution that allows the prime minister to shape policies in a way that brings them closer to her own preferences (constrained by the preferences of the legislative majority) (Diermeier and Feddersen Citation1998; Huber Citation1996a). The confidence vote is also seen as a mechanism that, as put by Huber (Citation1996b), helps to reconcile a tension that is at the core of democratic governance: the fact that politicians must compete to win elections but cooperate to govern. Thus, when, from the government’s point of view, legislators are faced with the need to support policies that are not favourable to their constituents, the confidence vote provides credible electoral cover: it allows legislators to support the government but claim to their voters that the alternative – no policy but also no government – was worse. But the confidence vote is also clearly related to government termination: once invoked, government resignation becomes a possible outcome.

The institution is quite simple. The government either requests that parliament take a vote on a motion expressing its confidence in the government or announces that the vote on a given policy is also a vote of confidence in the government. In some cases, the vote on the policy or the motion is based on the general decision rule used for regular parliamentary decision making; in other cases, the confidence vote requires the use of a different decision rule. If parliament expresses confidence in the government, it remains in office and, when confidence is attached to a policy, the legislative status quo is changed; if parliament fails to express confidence in the government, the government must resign. It is easy to see how a confidence request changes the calculus of the legislators who belong to government parties. Under normal circumstances, the legislators voting decision requires a weighing of the policy status quo against a policy proposal; under a confidence request, the comparison also involves the very existence of the government; the comparison is no longer between simply keeping or changing the policy status quo, but keeping the policy status quo and not the government or changing the policy status quo and keeping the existing government.

The confidence procedure varies in many important ways. In one potentially important instance, some constitutions allow the government to raise the issue of confidence in general, that is, without it being attached to approval of any specific policy proposal. The rationale for this is that it would allow the government to obtain a clear and public statement from parliament about the level of support it can expect in its future pursuits. Presumably, this would allow the government to proceed in advancing policies that it might have otherwise not pursued or pursued with great difficulty. The ultimate goal of employing the confidence procedure in this case is still policy related. But unlike confidence requests which are attached to a specific policy proposal and thus have immediate implications, those of this type are meant to boost the government in its pursuit of broader actions in the immediate future. In this sense, this general expression of confidence would not be too distant from an informal delegation from the parliamentary majority to the government. On the other hand, to the extent that a successful generic vote of confidence does not imply any real delegation of authority, its power to induce government legislators to support specific proposals in the future may be purely symbolic. When the time comes for these future votes to be taken, legislators will weigh the alternatives in the same way they weigh any other policy proposal: the value of the existing policy status quo versus that produced by the new policy. Since defeat of the policy under consideration does not imply government resignation, no consideration of government survival is likely to enter legislators’ minds.Footnote12

Another variation in the structure of the vote of confidence has to do with what the legislators actually vote on and, as a matter of fact, whether they are required to vote at all. The standard procedure in most votes is that the choice is made explicitly over the option available: given a motion of confidence or a policy to which confidence is attached, legislators would vote ‘yes’ to approve or ‘no’ to disapprove the motion or the policy. In some constitutions, however, the use of the confidence procedure triggers the opportunity for a no-confidence motion to be raised within a specified period of time. The expression of confidence requested by the government is granted when a majority rejects the motion of no confidence. Thus, given the government's initiative, the burden of mobilisation is placed on the opposition to that initiative. The French and Romanian constitutions provide for an even stronger mechanism: once the government attaches confidence to a proposal, it is considered approved if a motion of no-confidence is not introduced and approved by an absolute majority within 24 hours. It is the fact that a bill can become law without the express consent of parliament that so enrages many observers, who take this provision as one more indication of the irrelevance of parliament in a world of strong and undemocratic executives. Yet, not acting when one is given the choice to do so is different from not being allowed to act; in this case, not acting is itself a choice in a menu of options that includes rejecting the policy. As one would presume, and Huber (Citation1996b) demonstrates, all that the ‘lack of action’ entails in this kind of strong confidence procedure is that it allows the executive to get the best outcome it can get within the range of outcomes that a legislative majority is willing to tolerate.

In some countries, the confidence procedure, like the vote of no confidence, evolved in practice before it was formally introduced into constitutional documents. We defined parliamentarism above as the system in which the government must be at least tolerated by a legislative majority. In practice, this means that the assembly may remove the cabinet at (almost) any time for whatever reason or no reason at all. Similarly, the government may submit its resignation at any time for whatever reason or no reason at all. Although this is technically true of governments in any system, only in a parliamentary system is the resignation of the government seen as part of the normal functioning of institutions. Although this is a simplification, it highlights the fact that governments in parliamentary systems do not have fixed terms for two reasons: they can be removed by parliament or they may just resign. If the possibility of voluntary resignation exists, then any government may use it strategically to get its way in the political (legislative) arena. Note that the threat to resign can be used strategically even if the confidence vote is not formalised or constitutionalised; the potential threat to resign is an inherent feature of parliamentary systems even without formal institutionalisation. Thus, the institutionalisation of the confidence procedure is similar to that of the no-confidence procedure: it clarifies areas of ambiguity, specifies procedures, spells out consequences. At the same time that this was done, many constitutions also tilted the procedure to favour the government rather than the opposition. Thus, in the set of constitutions analysed in the previous section, we found that there are 29 which contain at least one paragraph dedicated to establishing the possibility that the government may request a vote of confidence from parliament. With the exception of the 1920 constitution of Czechoslovakia, all of them were written after 1945. Fifteen of these constitutions adopted procedures that clearly favoured the government; in eleven of them, confidence in the government could be expressed by a simple majority, that is, 50% of those voting; in two, Greece 1975 and Portugal 1975, confidence is expressed with a plurality or a negative majority, respectively;Footnote13 and in two, France 1958 and Romania 1991, the failure to pass a censure motion with the support of an absolute majority in response to the government’s engagement of parliamentary confidence in connection with a piece of legislation implies the legislation’s approval. In all but one case of constitutions with confidence procedures, the failure to obtain a positive expression of confidence implies the resignation of the entire government. The exception is Slovenia 1991, where failure to obtain confidence allows for three possible outcomes: the assembly elects a new prime minister within 30 days; the president dissolves the assembly; or the prime minister obtains a new vote of confidence.

Thus, significant changes were made with respect to both the no-confidence and the confidence procedures in parliamentary constitutions during the post-WWII period in Europe. Today, the majority of constitutions explicitly include a statement to the effect that governments are collectively responsible to parliament; many go further and specify in quite some detail the procedures that must be followed in order for a no-confidence vote to be introduced and approved: (1) A non-trivial number of legislators must support the motion’s introduction and, if it is defeated, those who supported the motion are likely to be barred from doing it again within some period of time. (2) Approval is likely to require the support of a majority of members of the legislature, and not simply of those voting, thus making it harder for motions to be approved. (3) A successful no confidence motion almost universally causes the government to resign. Running alongside these cases, are those that introduce a constructive vote of no confidence, which ties the removal of an existing government to the selection of the next. A similar process of constitutionalising the government’s confidence request has also taken place during the same period. Like the no-confidence vote, a loss for the government, the denial of confidence by the parliament, explicitly requires the resignation of the government. Unlike the no-confidence vote, votes of confidence on a government’s request can generally be approved by a simple majority. Moreover, unlike the no-confidence vote, the threat to resign can be made by the government, whether the constitution explicitly allows it or not. Together these measures, first, clarify ambiguities that existed when parliamentarism functioned simply on the basis of conventions and, second, protect the government by raising the bar for its removal.

Government resignation and assembly dissolution

One feature of most parliamentary systems is that assemblies can be dissolved before the end of their constitutional terms. Often, governments induce parliamentary dissolution and the occurrence of early elections for strategic reasons (Lupia and Strøm Citation1995; Smith Citation2003). This brings us to issues related to the power to dissolve the legislative assembly, a power that is pervasive but not necessary for a parliamentary regime to exist. Where this power exists, the premature dissolution of the legislature and the calling of new elections is an option available to some actors in the course of their ordinary conduct of the business of governing. In fact, it is the possibility of assembly dissolution that, sometimes, renders the no-confidence and the confidence votes effective. In fact, the possibility of dissolution looms large in most parliamentary systems and presumably affects the behaviour of all actors involved in the process of policy negotiation (Becher and Christiansen Citation2015; Lupia and Strøm Citation1995).

Assembly dissolution interacts in a complex way with the confidence and no-confidence procedures analysed in the previous section (Becher Citation2019). Dissolution is a consequence, rather than a cause, of government termination. Yet, its possibility affects the conditions under which the confidence procedure will be used and, given that it is used, the calculus of legislators regarding how to vote. In this sense, the two confidence procedures and the possibility of premature assembly dissolution are intertwined.

In this section, we argue that the nature of assembly dissolution in contemporary European parliamentary systems has changed significantly: it went from the expression of an executive prerogative, exercised at will by whoever embodied the executive, to a constitutionally prescribed device to resolve impasses in the process of forming a government and legislating. This does not imply that dissolution no longer results from strategic behaviour on the part of prime ministers, presidents, individual legislators, or parties. After all, actors can strategically behave in the pursuit of the impasse that, they know, will entail the premature dissolution of parliament. All we are saying is that the incumbent government now has less discretion over assembly dissolution and that it is not the only actor that can act strategically to cause a dissolution. In the next section we discuss early parliamentary elections as a mechanism to provide incumbent governments an electoral advantage. After that, we show how early elections have become tied to specific events that are identified in constitutions as ways to resolve legislative deadlocks.

Together, these subsections show how contemporary parliamentary regimes deviate from a view of parliamentarism according to which unconstrained power of dissolution is what balances the parliament’s ability to pass no confidence votes.

Early elections as incumbent advantage

For some political scientists, the government’s ability to dissolve parliament before the end of its term is of the essence of parliamentarism. In these systems, governments are assumed to be free to dissolve the assembly at any time and, given this power, do so to improve their position: they call early elections when public opinion is favourable to the government or at least not as opposed to it as it may become in the near future. In this way, incumbent governments increase the number of seats they control or, at least, reduce any electoral losses that may be inevitable in the near future.

This view is at odds with the role of early elections in the ‘classic’ theory of parliamentarism (Selinger Citation2019). If there has ever been such a ‘classic’ theory, in it the function of assembly dissolution is to allow voters to make the ultimate decision when there are disagreements between the government and the parliament on important issues. Although there are many instances in the history of parliamentarism in which assemblies were dissolved in order to allow voters to express their view on a specific issue, this is far from been the modal reason for early parliamentary dissolution.

The right to dissolve parliament, just like the right to convoke it, has, from the very beginning, been the monarch’s prerogative. As is well known, in England, but not only there, parliaments were called when the monarch saw fit and were dismissed when the monarch decided that they had accomplished the objective for which they had been convened. To a large extent, the history of the emergence of responsible government is the story of how the cabinet was transformed into a body distinct from the monarch and, eventually, one that was controlled by the parliament (Roberts Citation1966). A condition for this to happen is that the parliament exists independently from the monarch’s will. The passage of the Meeting of Parliament Act of 1694 and the Septennial Act of 1716, which required that Parliament be held at least once every three or seven years, respectively, represents an important moment in the history of parliamentarism. Neither act required that parliaments last for the full length of the term for which they had been convoked. But implicitly, both recognised that a parliament would exist continuously and that it would be periodically renewed. Monarchs, therefore, were no longer able to avoid calling a parliament, like they had done up to the end of the 17th century. Indeed, that a parliament exists by right is a basic condition for the establishment of parliamentarism since a government cannot be responsible to a body whose existence can be arbitrarily decided by another actor. This is why constitutional provisions establishing that parliaments ‘convene of right’, and that new elections must be called within a certain period after parliaments are dissolved, are so important in the constitutional history of parliamentarism. By the middle of the 19th century, provisions such as these existed in every European constitution, even those in which references to government responsibility were non-existent or very basic.

Whereas the right to be convoked was well entrenched by the 19th century, parliament continued to be seen as something the monarch could dismiss at will. As a matter of fact, dissolution became a crucial weapon in the monarch’s conflict with parliaments over the control of the executive. As Przeworski et al. (Citation2012) have shown, some monarchs resisted parliamentary control of the government by dissolving the assembly and staging elections that would produce results more akin to their preferences. Combined with a tight control over the electoral process, a control that included a ‘menu of manipulation’ not unlike the one available to contemporary electoral authoritarian leaders (Schedler Citation2002), dissolution was the mechanism which, according to Lauvaux (Citation1983), allowed monarchs to adjust the parliament to the composition of the government, rather than the government to the composition of parliament. Without the power to remove unsupportive parliaments, it is likely that monarchs in the countries where parliamentarism ‘evolved’ would have been much less patient and restrained than they have been forced to be.Footnote14

The executive’s unconstrained right to dissolve the assembly, which today only exists in a few constitutions, is thus the mere survival of the power of dissolution as practiced in the 19th century by pre-parliamentary heads of state. One fundamental difference, of course, is the fact that elections today are no longer as executive controlled as they were then. Elections in most of Europe today occur free of significant malpractices and undue influence by the government. But the fact that parliaments can be dissolved at any point during their term, even with competitive elections, grants the executive an advantage that is not dissimilar to that 19th century monarchs possessed. Though now vested in a prime minister ultimately subject to popular elections, it is still true that the discretionary power to dissolve parliament allows the incumbent government to seek a more adequate distribution of seats than the one obtained at the time the seating parliament was chosen. And, keeping in mind the caveats necessary to interpret the available evidence, incumbent prime ministers, unsurprisingly, do benefit electorally from calling early elections (Schleiter and Tavits Citation2016; Strøm and Swindle Citation2002). Thus, even under democratic conditions, incumbents who are allowed to call new elections seem to be able to improve the conditions under which they govern.

Restricted assembly dissolution

Today, only a small number of parliamentary constitutions allow for unconstrained dissolution by the government. A significant portion of these refers to countries where the British constitutional tradition is strong (Australia, Canada, New Zealand), even though the United Kingdom itself has moved to significantly reduce the conditions under which parliament can be dissolved. In fact, in an analysis of dissolution provisions in 56 European constitutions, Goplerud and Schleiter (Citation2016) find that only ten receive the highest value in their score of discretionary dissolution, that is, the score indicating that the prime minister, the government, or the president are unconstrained to unilaterally dissolve the assembly. In all other constitutions significant restrictions are imposed on dissolution: the number of times an assembly can be dissolved by the same actor or for the same reason; suspension of the right to dissolve during a certain moment in the life of the assembly, or in the term of the cabinet or the head of state; termination of the head of state’s term in office if the assembly is dissolved before the end of its constitutional term. In other words, a large number of constitutions now include significant restrictions on the executive’s power to dissolve the legislature, forcing it to seek a solution to disagreements through compromise.

Even more significant is the fact that in many constitutions, dissolution is associated with the occurrence of specific events that denote the existence of an impasse. Many constitutions, all post-1975, require the dissolution of the assembly if a government fails to win an investiture vote after a certain amount of time has elapsed since its appointment, or after a certain number of failed formation attempts. Other constitutions allow for dissolution if a budget is not passed, or if legislation is not passed in parliament. These provisions establish that in the face of a situation that makes it impossible to proceed with the normal business of governing, voters will be called to attempt to resolve the impasse. But, unlike before, there is no incumbent government that may benefit from the new election since either the government has not yet been formed or it is simultaneously dissolved with the parliament. Other than the occurrence of such conflicts, parliaments will exist for the duration of their terms.

To the extent that early assembly dissolutions became less discretionary and more associated with pre-identified events inscribed in constitutional documents, they became less frequent: parliaments, in turn, lasted longer, with durations that were closer to their full constitutional term. This is what can be seen in .

Figure 5. Proportion of parliaments surviving 90%, 95% and 99% of their terms by decades, Europe, 1800–2019.

Note that coding early elections in a cross-national context is not without its challenges. Although it is possible to obtain information with respect to the timing of specific elections, we have not been able to directly determine the status of a large number of elections. In light of this, our strategy to determine the occurrence of early elections has been to combine information about the date the election occurred and the length of the parliamentary term. We consider three definitions of a full parliamentary term, such that a parliament is considered to have served a full term if the time between two elections was at least 90%, 95% or 99% of its maximum constitutional term, counting from the day of the election. These thresholds are arbitrary, but they serve the purpose of demonstrating that, under many different cut-off points, the proportion of parliaments serving for a full term has been increasing since the middle of the 19th century. As indicates, under the laxest criterion, in the 1850s only about 10% of parliaments completed their full term; in 2019, close to 60% did. Under the most stringent criterion, the figures are, respectively, about 5% and 53%. There were fluctuations along the way, but those were temporary.

Thus, parliamentary dissolution has become less arbitrary and, as a consequence, legislatures in parliamentary regimes are sitting for a longer period of time than they did before. Dissolution as a mechanism to resolve an impasse is still possible; but the tendency is for the circumstances of the impasse to be pre-identified in the constitution and for dissolution to occur as a solution of last resort. In this sense, at the same time that contemporary parliamentary constitutions tend to protect governments from fleeting or negative majorities, they also protect parliaments from the whims of incumbent executives. The system is still flexible in that government termination and assembly dissolution are possible courses of action that are not available in alternative constitutional designs. But there is an element of rigidity that may have been what saved the system from the outcomes observed prior to WWII.

Conclusion

Parliamentarism is a system of responsible government; if not tolerated by the legislature, the government can be voted out of office for purely political reasons. It is often seen as having evolved over the years in a continuous struggle between a monarch and the legislature for control over the executive government. It is also frequently seen as a system that requires little institutional designing since the very principle that defines it provides a mechanism for resolving deadlocks between the executive and the legislative powers. This is buttressed by the fact that the institutional framework that emerged over decades in England, largely based on unwritten rules, became identified as the paradigmatic case of parliamentarism.

In this paper we argued that, although this is true for the UK and a handful of other countries, it does not describe the experience of the rest of Europe. We showed, first, that the trajectory of parliamentarism in many countries has been far from being a straight line. Instead, parliamentarism frequently collapsed, indicating that it did not provide the framework that allowed for the peaceful resolution of conflicts given the conditions that then prevailed. We then analysed three central parliamentary institutions, which are consequential for the termination of governments, the hallmark of the system: the no-confidence procedure, which is initiated largely by the opposition; the confidence procedure, which can be requested by the government; and the premature dissolution of the parliament and holding of new elections.

With respect to the first institution, we showed that most constitutions today have explicit provisions regulating who can move a no-confidence motion, how these motions are to be voted on, the decision rule to be employed, and the consequence of a successful motion of no confidence. We highlighted two aspects of the process of institutionalisation of the no-confidence procedure: the fact that almost in all cases a successful no-confidence vote mandates the resignation of the government, and the adoption of absolute majority as the decision rule for voting no confidence. The former removes any ambiguity as to what should happen in cases in which parliament expresses no confidence in the government, preventing the emergence of conflicts over how to interpret certain events. The latter raises the bar for a majority to remove the government, making the emergence of negative majorities, those that only agree on the government they do not want to have, less likely. Parallel to these developments, we also noted the creation of the constructive vote of no confidence, which associates the removal of a government with the simultaneous installation of another.

As to the confidence procedure, we noted that in many recent constitutions it too is clearly stated. These constitutions specify that the government can request that the parliament express its confidence in it, whether through a dedicated motion or in association with a specific bill. Although resigning is an option always open to any government, the explicit constitutionalisation of the procedure, again, removes ambiguities by forcing the government who threatens a resignation to actually do so if no majority voted for it to stay. The decision rule for the confidence vote is generally less demanding than that for the no-confidence vote. Thus, whereas the bar is raised for removing the government from office, it is lowered to favour its continuation in office.

Finally, we also identified a constitutional trend that makes assembly dissolution less subject to the discretion of the executive. Not only are prime ministers (or heads of state) less free to choose early elections as a course of action, they are also prevented from doing so under a series of circumstances specified in the constitution. Additionally, recent constitutions identify a number of circumstances that trigger the dissolution of the assembly, allowing actors to bargain with a clear and shared understanding of the outcomes associated with some courses of action.

These constitutional trends, we believe, keep parliamentarism still sufficiently flexible in the sense that it allows governments and majorities to adjust to changing circumstances. At the same time, it provides a blueprint that can be adopted and adapted to specific circumstances. Parliamentary systems, like presidential ones, must function under conditions of high or increasing inequality and polarisation and, given these circumstances, procedural clarity and a degree of status quo bias may not be a terrible idea.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (498.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Argelina Figueiredo, Fernando Limongi, Csaba Nikolenyi, Thomas Saafeld, Yael Shomer, Reuven Hazan and participants in the Workshop on Parliaments and Government Termination, Hebrew University, 9–11 February 2020, for their comments on a previous version. We extend a special thanks to Shane Martin for all the long and productive conversations we have had, some of which are reflected in this paper. We thank Francesco Bromo and Joowon Yi for excellent research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

José Antonio Cheibub

José Antonio Cheibub is the Mary Thomas Marshall Professor in Liberal Arts and Professor in the Department of Political Science, Texas A&M University. His research focuses on democratisation and democratic institutions. [[email protected]]

Bjørn Erik Rasch

Bjørn Erik Rasch is Professor and Head of the Department of Political Science, University of Oslo. His main research interest is democratic institutions and voting procedures. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 We think of semi-presidential systems as being ‘parliamentary’ since a majority in parliament can remove the prime minister and the cabinet from office. Given parliamentary responsibility, the fact that the head of state is popularly elected for a fixed term is not sufficient to make it a unique form of government. Note that this does not imply that popular presidential elections in these systems are inconsequential. Whether they matter depends on what for, and this is, essentially, an empirical question. There is a vibrant literature that studies the impact of direct presidential elections in parliamentary systems. We interpret its findings as primarily indicating that direct presidential elections have little or no effect on government stability, regime stability, accountability, and other outcomes (see, among many others, Cheibub and Chernykh Citation2009; Elgie Citation1999, Citation2011; Tavits Citation2008).

2 These figures come from Cheibub et al. (Citation2010).

3 We adopt the broadest possible definition of Europe to include countries in the analysis (East et al. Citation2020). We exclude Andorra, Monaco, Liechtenstein, San Marino, and the Vatican because they are not fully independent countries. We also exclude Switzerland and Cyprus because executives in their constitutions serve a fixed term in office.

4 See the Online appendix for the rules we used to code minimally competitive legislatures.

5 See Przeworski et al. (Citation2012) for the dates when first alternation in power due to elections took place. We follow Müller et al. (Citation2003: 12–13) in defining parliamentarism as the regime in which ‘the cabinet must be tolerated by the parliamentary majority’. This definition, thus, does not consider the head of state – a monarch, an indirectly elected president, or a directly elected president – as sufficient to characterize different regime types. For these reasons, constitutions that are considered ‘semi-presidential’ are as parliamentary as those considered ‘fully parliamentary’.

6 Turnover rate equals the accumulated number of changes of prime minister in each year divided by the age of the spell of competitive legislature. For example, a turnover rate of 2 means that by year t PMs were changing at the rate of two per year. The figure plots for each year, the average PM turnover rate for all the countries that had a competitive legislature in that year.

7 On the legal movement that sought to rationalized parliamentarism, see Lauvaux (Citation1988) and Bradley and Pinelli (Citation2012); for a discussion of specific constitutions within the framework of ‘rationalized parliamentarism’, see Huber (1996b) on France 1958, Wyrzykowski and Cieleń (Citation2006) on Poland 1997, Lauvaux and Le Divellec (Citation2015) on Germany 1949, Sweden 1974, Spain 1978, Italy 1947, and Tanchev (Citation1993) on post-communist Eastern European constitutions. See Lindseth (Citation2004) for the institutional conditions leading to the inter-war crisis in both France and Germany, as well as for an analysis of how these crises affected the post-WWII constitutions in these countries.

8 No-confidence votes can also serve electoral purposes, as Williams (Citation2011) and Somer-Topcu and Williams (Citation2014) argue. Lento and Hazan (2020) offer a framework to analyse no-confidence procedures that incorporates both their ‘electoral’ and ‘removal’ aspects.

9 We thank an anonymous referee for calling our attention to recent instances of the electoral use of the constructive no-confidence vote in Spain.

10 Underlined words in this paragraph represent the labels of the groups as they appear in Figure 4.

11 Most constitutions require a minimum number of signatories for tabling a no-confidence motion, ranging from one-tenth of members in Croatia 1958, Finland 1919, and France 1958, to as high as one-third of members in Belgium 1994, Czechoslovakia 1920, and Montenegro 2007.

12 We do not know how many generic confidence votes have taken place in European countries. As Rasch et al. (Citation2015) show, some confidence votes are, in fact, part of the investiture process: they are required as the final step for a government to be formed, whether they are formed after an election or not. Our discussion here does not apply to these cases since their occurrence is not subject to strategic considerations; they happen because they are required, not because the government chose to have it.

13 These are rather weak requirements, open to strategic manipulation as abstentions favor the positive votes; at the limit, assuming a required quorum of 50% of the assembly, a motion of parliamentary confidence in the government could be approved with support of 25% + 1 legislators.

14 And, to extend the reasoning beyond Europe, it is also likely that if presidents in the 19th century republics of Latin America had the power to legally dissolve congress, the number of ‘coups’ would likely be smaller (Limongi and Cheibub, Citation2021).

References

- Becher, Michael (2019). ‘Dissolution Power, Confidence Votes, and Policymaking in Parliamentary Democracies’, Journal of Theoretical Politics, 31:2, 183–208.

- Becher, Michael, and Flemming Juul Christiansen (2015). ‘Dissolution Threats and Legislative Bargaining’, American Journal of Political Science, 59:3, 641–55.

- Bradley, Anthony W., and Cesare Pinelli (2012). ‘Parliamentarism’, in Michel Rosenfeld and András Sajó (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Constitutional Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 650–70.

- Cheibub, José Antonio, Jennifer Gandhi, and James R. Vreeland (2010). ‘Democracy and Dictatorship Revisited’, Public Choice, 143:1-2, 67–101.

- Cheibub, José Antonio, and Svitlana Chernykh (2009). ‘Are Semi-Presidential Constitutions Bad for Democratic Performance?’, Constitutional Political Economy, 20:3-4, 202–29.

- Cheibub, José Antonio, Zachary Elkins, and Tom Ginsburg (2014). ‘Beyond Presidentialism and Parliamentarism’, British Journal of Political Science, 44:3, 515–44.

- Congleton, Roger D. (2011). Perfecting Parliament: Constitutional Reform, Liberalism, and the Rise of Western Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Diermeier, Daniel, and Timothy J. Feddersen (1998). ‘Cohesion in Legislatures and the Vote of Confidence Procedure’, American Political Science Review, 92:3, 611–21.

- East, W. Gordon, Thomas M. Poulsen, Brian Frederick Windley, and William H. Berentsen (2020). ‘Europe’, Encyclopedia Britannica, available at https://www.britannica.com/place/Europe (accessed 11 September 2020).

- Elgie, Robert (ed.) (1999). Semi-Presidentialism in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Elgie, Robert (2011). Semi-Presidentialism: Sub-Types and Democratic Performance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Figueiredo, Argelina, and Fernando Limongi (2000). ‘Constitutional Change, Legislative Performance and Institutional Consolidation’, Brazilian Review of Social Sciences, 1, 1–22.

- Goplerud, Max, and Petra Schleiter (2016). ‘An Index of Assembly Dissolution Powers’, Comparative Political Studies, 49:4, 427–56.

- Hazan, Reuven Y. (2014). ‘Legislative Coalition Breaking: The Constructive Vote of No-Confidence’, Presented at the workshop on Institutional Determinants of Legislative Coalition Management, Tel-Aviv University, November 16–19.

- Hem, Per, and Tanja Wahl (2018). ‘Mistillitsforslag, Kabinettsspørsmål, Kritikkforslag – en oversikt’, Perspektiv, 1, 18.

- Huber, John D. (1996a). ‘The Impact of Confidence Votes on Legislative Politics in Parliamentary Systems’, American Political Science Review, 90:2, 269–82.

- Huber, John D. (1996b). Rationalizing Parliament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lauvaux, Philippe (1983). La Dissolution des Assemblées Parlementaires. Paris: Economica.

- Lauvaux, Philippe (1988). Parlementarisme Rationalisé et Stabilité du Pouvoir Exécutif. Bruxelles: Emile Bruylant.

- Lauvaux, Philippe, and Armel Le Divellec (2015). Les Grandes Démocraties Contemporaines. 4th ed. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Lento, Tal, and Reuven Y. Hazan. (20xx in this issue). ‘The Vote of No-Confidence: Towards a Framework for Analysis’, West European Politics.

- Limongi, Fernando, and José Antonio Cheibub (2021). ‘Elections’, in Conrado Hübner Mendes and Roberto Gargarella (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Constitutional Law in Latin America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lindseth, Peter L. (2004). ‘The Paradox of Parliamentary Supremacy: Delegation, Democracy, and Dictatorship in Germany and France, 1920s–1950s’, The Yale Law Journal, 113:7, 1341–415.

- Linz, Juan J. (1994). ‘Presidential and Parliamentary Democracy: Does It Make a Difference?’, in Juan J. Linz and Arturo Valenzuela (eds.), The Failure of Presidential Democracy, Vol. 1. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 3–87.

- Lupia, Arthur, and Kaare Strøm (1995). ‘Coalition Termination and the Strategic Timing of Parliamentary Elections’, American Political Science Review, 89:3, 648–65.

- Mirkine-Guetzévitch, Boris (1950). ‘Le Régime Parlementaire dans les Récentes Constitutions Européennes’, Revue Internationale de Droit Comparé, 2:4, 605–38.

- Müller, Wolfgang C., Torbjörn Bergman, and Kaare Strøm (2003). ‘Parliamentary Democracy: Promise and Problems’, in Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman (eds.), Delegation and Accountability in Parliamentary Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 3–32.

- Negretto, Gabriel (2013). Making Constitutions: Presidents, Parties, and Institutional Choice in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.