Abstract

This article investigates the ‘conflict parabola’ of the negotiations between EU member states during the COVID-19 pandemic. The crisis reopened the foundational controversy over cross-national solidarity under economic adversities. After a peak of conflict in March–April 2020, the political climate gradually shifted from antagonism to appeasement, creating the conditions necessary for the adoption of the Next Generation EU plan. Building on the negative experiences of past crises, some EU leaders engaged in a strategy of ‘polity maintenance’, i.e. keeping the EU polity together, regardless of interest-based divisions. This strategy mainly rested on public communication. The article documents both conflict and appeasement by analysing a corpus of leaders’ quotes drawn from the press (covering eight countries) and a corpus of speeches by Angela Merkel. The Chancellor made a high political investment in EU polity maintenance, presenting European cohesion as part and parcel of Germany’s national interest.

This article analyses the ‘conflict parabola’ prompted by the COVID-19 crisis within the EU. We argue that the crisis reopened – with a vengeance – the foundational controversy over ‘who owes what to whom’ when member states are hit by severe adversities, a controversy already experienced in the manifold crises of the 2010s. The divisive imagery of saints and sinners reappeared in Europe’s public sphere, generating fears about disruptive rifts and a possible break-up of the Union. At the beginning of April 2020, the former President of the Commission Romano Prodi launched a passionate warning: if EU leaders could not find an agreement ‘even in such a dramatic situation, there [would be] no longer any basis for the European project’ (Die Welt 2020). After the April peak, however, the political climate gradually shifted from harsh antagonism to relative appeasement. Principled disagreements and policy disputes did not subside, but leaders started to converge towards the basic logic of the Next Generation EU (NGEU) plan, i.e. that of addressing the crisis by ‘walking the road together’, without ‘leaving countries, people and regions behind’ (von der Leyen Citation2020).

How did this relatively rapid switch from antagonism to appeasement unfold? How can it be interpreted? This article accounts for this puzzling pattern by adopting a ‘polity perspective’. We argue that, building on past negative experiences, some EU leaders were uneasy about the prospect of a new existential crisis and thus engaged in a deliberate strategy of reconciliation, which played out at two levels. On the one hand, an acceptable joint solution to the economic emergency had to be identified and negotiated in EU arenas. On the other, the desirability of this solution, involving deeper EU (fiscal) integration, had to be presented and justified to national publics. The two prongs of the strategy were obviously linked. But orchestrating the NGEU plan was primarily ‘policy-oriented politics’, while symbolic communication was essentially ‘polity-oriented’, serving the distinctive task of keeping the member states together.

Our study focuses on the second prong of the strategy and investigates how ‘polity maintenance’ unfolded in the European discourse over the economic recovery plan at the start of the COVID-19 crisis. It does that from a perspective on EU politics that acknowledges the key role played by the ‘communicative discourse’ in shaping perceptions of interests and institutional contexts, thereby facilitating (or obstructing) institutional reform (Borriello and Crespy Citation2015; Schmidt Citation2008). Polity maintenance typically becomes a salient political objective in the presence of potentially disruptive conflict. Therefore, we start by documenting the harsh confrontation over how the EU was to respond to the crisis. After the outbreak of the pandemic, the sharp divide between Northern and Southern member states seemed intractable, especially on the thorny issue of cross-national transfers and debt mutualisation. Initially siding with Northern governments, Germany gradually switched position and came to endorse the solidaristic approach and the specific proposals of the French government. This policy shift represented a U-turn with respect to the fiscally orthodox stance that Merkel’s governments had taken during the sovereign debt crisis at the beginning of the 2010s (Matthijs Citation2020). We argue that Merkel’s turn and her ability to legitimise it through communicative discourse played a key role in paving the way for the NGEU agreement.

In addition to offering a new and distinctive perspective on the political dynamics of the COVID-19 crisis, the article has a more general aim. By putting the questions of polity maintenance and the ‘solidarity ethos’ front and centre, and in particular the latter’s purposeful discursive construction, we suggest that in moments of severe adversity a close analysis of symbolic strategies of polity maintenance is as important as the empirical assessment of policy reforms. In the post-functionalist era when European integration has become politicised, incumbent leaders are forced to seriously consider the potentially politically undermining implications of distributive policies. Therefore, they have to send reassuring signals to various constituencies – in their countries and abroad – about the basic capacity of the member states to govern together as well as about their shared political and ethical commitments to integration, over and above ordinary policy disagreements.

The article is organised as follows. The next section introduces our analytical framework, while section three presents the research design and methodology. Section four tracks the shift from antagonism to appeasement through the analysis of a corpus of leaders’ quotes drawn from the national and international press. In section five we reconstruct the polity maintenance strategy deployed by the German Chancellor, based on the analysis of the speeches and press conferences she held between March and July 2020. The last section wraps up and highlights the wider implications of the article.

Polity maintenance in leaders’ communicative discourse

EU studies have been struggling for decades with the problem of capturing the nature of the EU as a novel political entity. Today few would challenge the idea that the EU is a ‘polity of sorts’ (Pollack Citation2005) In the Weberian tradition, being a polity means to exert authoritative control over a demarcated territory and its occupants, bonded together by a mix of associational and communal ties. Bounding (demarcations), binding (authoritative commands) and bonding (identity and social sharing) are the constitutive elements of a polity as well as the processes through which polities are built (Ferrera Citation2019). The EU polity has sui generis characteristics: to a large extent, it can actually be seen as a ‘metapolity’, i.e. a space which has gradually supervened on pre-existing and still partly autonomous national spaces. This feature renders the EU a fragile and ‘experimental’ polity, prone to functional crises and politicisation, including polity politicisation (Statham and Trenz Citation2015). The need for polity maintenance is thus much higher than it is for national consolidated polities.

By polity maintenance we understand a deliberate strategy driven by the primary objective of safeguarding the polity as such. The concept is related to ‘system maintenance’, a central notion of the structuralist-functionalist tradition (Almond and Powell Citation1978). However, while system maintenance connotes all the activities aimed at safeguarding the overall performance of any type of system, polity maintenance has a narrower target, i.e. the preservation of the territorial community qua political entity – in the sense specified above. When acting from a polity-maintenance logic, politicians subordinate or instrumentalise narrower policy aims to the ultimate objective of polity preservation. This implies in particular the (re)activation of diffuse support and legitimacy, i.e. the set of beliefs which attribute validity to authority, motivate compliance and nurture widespread feelings of ‘togetherness’ (Ferrera Citation2019). The need for polity maintenance is particularly high in hard times, i.e. when the polity is hit by severe exogenous shocks shattering the socio-economic structure and/or when internal conflicts take potentially destructive turns. In such cases, the challenge is more demanding than just ‘repairing legitimacy’ (Suchman Citation1995) by means of instrumental/functional arguments: it requires in fact the renewal of moral commitments to a polity which is perceived as valuable and which acts in accordance with shared collective purposes.

We borrow the contrast between ‘destructive’ and ‘constructive’ conflict from neo-Weberian theory (Collins Citation1975, Citation1986). In the former type of conflict, one or more parties tend to see disagreement in zero-sum terms, taking little or no responsibility for the overall direction of the process and therefore overlooking the wider picture which transcends the issue at stake, however salient and crucial for a single actor. This type of conflict is often accompanied by strongly antagonistic self-other conceptions: actors use tones and expressions which seem to delegitimise the quality of (or qualification for) membership of their ‘enemies’ in the same polity. In constructive conflict, actors instead quarrel about a specific (set of) issue(s) but tend to keep an eye on wider and shared important interests and values as well as on the long-term preservation of the mutual relationship. In our language, constructive conflict remains ‘polity-conscious’, i.e. at least implicitly aware of the risks and overall costs of polity disruption (let alone break-up) for all actors.

Polity maintenance is typically Chefsache, a ‘cause’ to be pursued by top executive leaders.Footnote 1 They are in fact the formal custodians of the very territorial system which they are meant to ‘lead’. It is often forgotten that democratic leaders are bound not only by the duties of responsiveness and accountability but also by a wider responsibility towards ‘the whole’ in its functional and political foundations (Sartori Citation2016). Since its key aim is legitimation – in our case, diffuse support for ‘walking the road together’ in responding the COVID-19 crisis – polity maintenance typically rests on public communication addressed to the widest possible audience and makes extensive use of symbolic resources. Leaders strive to reinfuse value in ‘togetherness’ – the fact of belonging to a common political space. Shared experiences and purposes, solidarity commitments and practices are reconfirmed and presented as key form of leverage for upholding systemic integrity and restoring overall durability and performance.

Polity-maintenance-motivated leaders typically engage in two courses of action. On the one hand, they seek to shift the focus from substantive juxtapositions of issues towards the basic ‘floor’ on top of which all polity interactions (including conflicts) occur. On the other hand, leaders launch appeals to tone down antagonistic interactions and to adopt pragmatic and compromising stances in a constructive fashion. This dual change of perspective is meant to produce various positive effects: extending the horizon of actors, allowing them to perceive the wider balance of intertemporal costs and benefits which accrue from polity membershipFootnote 2 ; opening up unexploited opportunities to reach compromises and package deals; and providing conflicting parties with a broader and shared sense through which to interpret their substantive and relational choices.

A polity-maintenance strategy must be discursively constructed. As the public sphere tradition has argued (Habermas Citation1989), the emergence and durability of legitimate orders are accompanied by constant discursive processes in which different standards for accepting/supporting authority and different understandings of the polity confront each other. Thus, while both ‘coordinative’ and ‘communicative’ discourses are important (Schmidt Citation2008),Footnote 3 the latter plays a crucial role. Polities are essentially ‘imagined we spaces’; their maintenance is as much a question of specific interest-based transactions as of general and diffuse normative beliefs about the desirability of continued membership. Therefore, the study of the public discourse of leaders is an obvious entry point for understanding the logic of polity maintenance.

Research design and methodology

This article has primarily heuristic objectives. We revisit important concepts of the political science tradition – polity/community and polity maintenance – and highlight their persisting analytical and theoretical significance. We then suggest how to operationalise such concepts and measure their role in communicative discourse. As such, our exercise does not have causal explanatory ambitions. In the language of process tracing, we limit ourselves to a preliminary ‘straw in the wind’ test (Van Evera Citation1997), i.e. ascertaining whether the constituent parts of our argument can be observed empirically in the expected temporal sequence.Footnote 4 In the context of this paper, this implies finding evidence that: (1) there were indeed harsh and potentially polity-disruptive conflicts, particularly at the beginning of the crisis; (2) these were followed by reconciliation efforts on the part of key leaders, based on explicit polity-maintenance objectives; (3) such efforts accompanied a more general turn towards constructive conflict and cooperation throughout the EU, possibly reflected in citizens’ perceptions. Finding empirical traces of such a temporal sequence is crucial for turning our argument into a plausible causal mechanism deserving of additional exploration against alternative and complementary hypotheses.

We proceed in two steps. First, in the next section, we focus on conflictual dynamics between EU elites during the COVID-19 crisis management debate. We document the escalating antagonism surrounding the issues of cross-national solidarity and debt mutualisation and show that conflictual dynamics gradually attenuated after the European Council of 23 April, with Germany being the only member state to switch sides by openly endorsing mutualisation. We hypothesise this shift as being key in tilting the overall balance of forces in favour of greater fiscal integration, not only due to Germany’s hegemonic position within Europe’s political economy (Matthijs Citation2020) but also because it removed from the fiscally conservative coalition its most powerful actor. However, such a reversal of Germany’s traditional negative stance on risk mutualisation required public justification, in primis to German voters but also to the ‘frugal’ countries. As such, in a second step (fifth section), we narrow the focus to analyse how Germany justified this policy change and eventually become a defender of it in the context of the NGEU negotiations.

For the analysis of discursive conflict between EU national governments, the fourth section draws on the methodology of claim-making analysis (Koopmans and Statham Citation2010; Papadimitriou et al. Citation2019). More concretely, we analyse all ‘direct quotes’ by a number of EU leaders that appeared in a selection of both national and international newspapers between March and July 2020. In order to build our corpus, we have used the electronic depository of newspapers Factiva. We are aware that selecting quotes from newspapers to study elites’ discourses has the shortcoming of incorporating journalists’ own reporting biases. However, as recognised by a vast literature (e.g. Hutter et al. Citation2012), such a method has the advantage of identifying those parts of the elites’ discourses that actually reach wide audiences and thus have the potential to shape opinion formation.

We have selected 19 political leaders who played a key role in the EU macroeconomic debate on the management of the COVID crisis (see in the Online appendices). These include the heads of government and the finance ministers of ten EU member states, involving both traditionally frugal states (Austria, Denmark, Germany and the NetherlandsFootnote 5 ) and pro-fiscal integration member states (Portugal, Spain, Italy and France). We have also traced the discourses of the President of the European Commission and the European Commissioner for Financial Affairs. Using search strings that contained both the terms ‘name and surname of the leader’ and ‘European Union’ or ‘EU’ (in both English and national languages) and looking for each leader into two national quality newspapers (see in the Online appendices) as well as in Reuters, the Financial Times and Euractiv, we recovered a total of 4,044 articles from Factiva archives. Through a process of manual coding supported by the software NVivo 12, we recovered 1,087 unique quotes that contained claims/arguments about the EU and the COVID-19 crisis.

Table 1. Coding scheme on constructive versus destructive moods in leaders’ communicative discourse.

We manually coded each quote along two dimensions. Borrowing from sentiment research (Gaspar et al. Citation2016), the first dimension captures the antagonistic or conciliatory nature of leaders’ discourses. summarises the (ideal-typical) discursive practices that we connect to either ‘constructive’ or ‘destructive’ political conflict. Following these guidelines, we assigned each quote to one of these two categories of conflict (respectively coded as −1 and +1) and added a third category to capture neutral stances (coded as 0).

The second dimension concerns leaders’ substantive positions on ‘fiscal risk pooling’, i.e. the readiness to support a relative EU centralisation of financial resources and their management with a view to mitigating the impact of economic adversities on member states. As is known, this was the most contentious matter. We have inductively identified a number of relevant policy issues related to risk sharing, and we have then coded the various quotes according to a trichotomous ordinal measure in which the value (+1) indicates support for greater risk sharing, the value (-1) opposition to greater risk sharing (and therefore greater defence of the principle of national responsibility) and the value (0) a neutral or absent evaluation on the policy issue.Footnote 6 For example, in the debate on the establishment of temporary fiscal transfers, we have assigned the value of (+1) to those opinions defending grants and (-1) to those defending loans.Footnote 7 As for the reliability of the coding results, we obtained a Cohen’s kappa coefficient of 0.78, which according to Stemler (Citation2000) can be considered a ‘substantial’ intercoder coherence. Online appendix 2 provides the descriptive statistics of our leaders’ quotes database, which is available upon request from the authors.

For the analysis of Merkel’s communication strategy (fifth section), we collected all the pertinent speeches (18) pronounced by the Chancellor between March and July 2020. We then coded each sentence of each speech based on a deductively elaborated scheme which breaks down our master theoretical concept – polity maintenance – into three different analytical components: frames, symbols and values (Chong and Druckman Citation2007; Pansardi and Battegazzorre Citation2018). Frames are specific definitions and interpretations of social reality which confer meaning to a sequence of events, and symbols are mental representations of reality which confer some normativity to it. Finally, values are desirable states of affairs which ground the normativity of symbols.Footnote 8

These three categories are not per se reserved for discourses about polity: they may well be used for policy discussions also. Thus, our analytical effort has been to identify in Merkel’s speeches specific discursive features which can qualify as being polity-supporting. The key distinctive feature of the latter is that challenges, their causal implications, as well as responses tend to be decoupled from their substantive and contingent policy content and to be represented instead in a more abstract and general form, thereby emphasising their deeper implications for the broader community. Synechdoches are often used: what matters is that the ‘part’ symbolising the whole (for example, the internal market) is defended as such, ultimately as a precondition for smooth and productive interaction (for example, as a ‘higher-order good’). Rhetorical figures play an important role in inspiring, motivating and building the public’s confidence (Mio et al. Citation2005), in group making and unmaking (Bourdieu Citation1991). Another feature of polity frames is the use of a distinctive expressive repertoire (Bull Citation2007): a dramatisation of the challenge; an explicit reference to its disruptive systemic consequences; explicit appeals to joint action, cohesion and solidarity; a call for extraordinary efforts, up to the challenge but also in line with prevailing values and historical legacies; a tendency to shift from instrumental/procedural to ethical/political justifications; and the presence of pathos and an emotional style.

In sum, we have centred our identification of polity-maintenance communication in Merkel’s speeches on two criteria: a set of analytical categories for coding single sentences and a set of theoretical guidelines aimed at sorting out polity-related from policy-related sentences.

A fast-changing parabola: from harsh confrontation to gradual appeasement

The COVID-19 outbreak came suddenly and unexpectedly to Europe. It soon became clear that, on top of the dramatic death toll, the economic consequences of the pandemic were to be massive, entailing negative implications for the overall equilibrium of the EU economy. Member states were initially deeply divided on how to respond to this challenge. However, contrary to what happened during the euro crisis, this time it took them only about five months to reach an agreement (the NGEU recovery plan and the new Multiannual Financial Framework [MFF] endorsed in July 2020) (Ladi and Tsarouhas Citation2020). In these five months, the initial tensions were toned down, and the need to reconcile different views and find a compromise took priority.

The fast-changing parabola of the conflict surrounding crisis management was clearly perceived by the European public. Data from the survey ‘The economic and political consequences of the COVID-19 crisis in Europe’ show that the vast majority of citizens in six member states did note the shift from confrontation to appeasement. Interviewed in early June, a share of respondents ranging from 75 per cent in the Netherlands to 90 per cent in Germany recognised that, at the outbreak of the pandemic in March, national leaders were strongly divided on common European solutions (online appendices Figure A1). On average, about 65 per cent of respondents also agreed that since the end of April EU leaders had become more committed to cooperation and mutual help (only slightly more than half of the respondents in Italy and Sweden but above 65 per cent in Germany, Spain, France and the Netherlands).Footnote 9

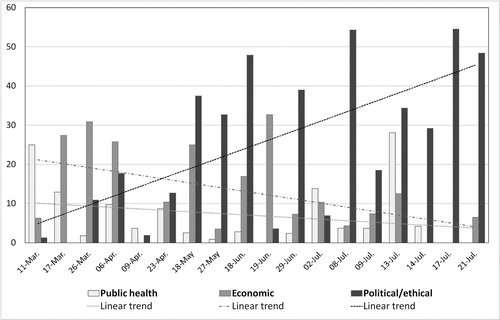

Figure 1. Total number of antagonistic statements (shaded area, left axis) and average constructive/destructive tone of leaders’ quotes from the press (lines, right axis): weekly trends.

The high degree of conflict perceived by European citizens at the outbreak of the pandemic reflects the turbulent politics which unfolded in the EU public sphere. provides a bird’s-eye view of developments in line with the antagonism-conciliation dimension described in the previous section. The shaded area indicates the weekly number of antagonistic statements (left-hand axis scale). This helps to identify the peaks of the conflict, which were reached in the fourth week of March and in the second of April, when the highest numbers of antagonistic statements appeared in the press (respectively 36 and 43). The lines show the evolution of the average tone of leaders’ quotes (right-hand axis) for three country groups: the three most outspoken ‘frugal’ countries (Austria, Denmark and the Netherlands), Southern countries plus France, and Germany. The latter indicator is computed as the mean of antagonistic/conciliatory/neutral statements; it ranges from −1 (when all claims were antagonistic – an utterly ‘destructive’ conflictual style that characterised, for example, frugal countries in the weeks from May 4th to May 17th) to +1 (all conciliatory claims, suggesting a ‘constructive’ attitude, as in the case of Southern countries in the first week of June and of Germany during May 4–10 and 18–24).

suggests three phases in leaders’ discourse around EU negotiations. Initially, the debate in the media was clearly dominated by Southern member states and France (see Figure A3 in the online appendices), which, being more affected by the virus, were ‘louder’, assertively calling for help and solidarity. Their calls, however, remained unheard. Business-as-usual politics was going on in the other member states, where domestic public spheres were still consumed by other issues (i.e. a scarce presence of claims concerning the EU COVID crisis in early March: online appendices Figure A3). Germany and the frugal countries only entered the media debate in mid-March. A second phase goes from late March to the end of April. In this period, the COVID crisis hit the headlines throughout Europe: albeit to diverse extents, everyone was affected, and the economic repercussions of lockdowns became a shared concern.

The ‘destructive’ peak of the conflict was reached soon after the European Council meeting of March 26. Cross-country contrapositions became barefaced, emblematically brought into the spotlight by the quarrel between the Dutch Finance Minister Wopke Hoekstra and the Portuguese PM António Costa.Footnote 10 The week of April 6 through 12 registered the highest number of antagonistic statements on both sides. Remarkably, at the peak of the conflict Germany went against the tide, maintaining a conciliatory tone (fine-dashed line in ). This was due to the outspoken solidaristic stance taken by the German Finance Minister Olaf Scholz, who broke the initial silence of Angela Merkel (no reported statements from the Chancellor in the week following the March 26 Council meeting, when the political climate heated up: see Table A2 and Figure A3 in the online appendices). At the same time, Scholz orchestrated a compromise with France’s Finance Minister Le Maire through a bilateral dialogue that mostly took place ‘behind the scenes’ (Chazan et al. Citation2020) but whose solidaristic aim was made clear in the public sphere by a number of joint statements to the press (as registered in our database).

Table 2. Merkel’s COVID19 crisis frames.

Antagonism across the north-south divide continued until the Council meeting of April 23, when state leaders reached an agreement that started to pave the way for a shared EU recovery plan.Footnote 11 After that, a third phase can be identified, whereby the conflict surrounding policy responses to the crisis gradually became less harsh. The total number of antagonistic statements reported by the press decreased (shaded area in ), and the general mood veered towards more constructive and conciliatory relationships (upward trend of the lines). Southern leaders toned down their antagonistic stance already in the run up to April 23, when they began to show openness towards the less sweeping policy proposals of the Frugal Four. On the other hand, since the beginning of May, the Frugals were less present in the media (online appendices Figure A3), although their very few public statements remained mostly antagonistic (thus the slump of the dashed line in in the first weeks of May). However, afterwards, they also gradually shifted towards a more constructive position. Again, hardly any antagonistic statements came from Germany, which adopted a more conciliatory tone during the whole period observed.

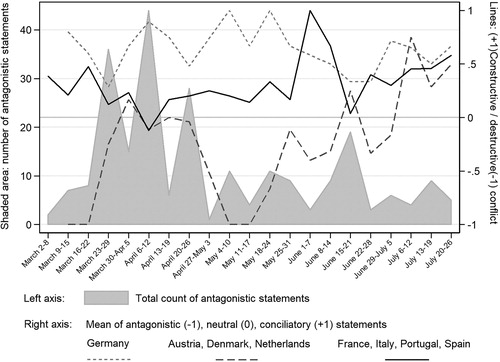

illustrates developments along our second dimension, i.e. policy positions regarding risk pooling. The figure displays the same country groupings as above and adds as a benchmark the position of the European Commission. After the business-as-usual period at the beginning of March, the second phase (late March/April) appears to be characterised by very high polarisation of policy preferences, with a clear juxtaposition between Southern and Frugal countries. On one side, Italy, France, Portugal and Spain advocated high-risk-pooling policy responses, such as the flagship proposal of ‘coronabonds’, de facto calling for a leap towards a fiscal union. On the other side, the Frugal Four (backed by Finland and some Eastern member states, not shown in the graph) opposed any step in that direction and, digging their heels in on the grounds of their long-standing concern for moral hazard, insisted on national responsibility by favouring the use of existing crisis resolution mechanisms and (conditional) loans to countries in need. In this phase, Germany oscillated between the two poles: siding with the Frugals in opposing coronabonds but taking a relatively supple stance and repeatedly calling for European solidarity. Such oscillations reflect the initial divergence in opinions between Merkel, rather sceptical towards the option of issuing joint debt, and the Finance Minister Scholz, who was since the beginning more sympathetic towards that option. The position of Germany coalesced around a pro-risk-pooling stance by the middle of May. The dashed line for Germany in rises and remains stable in the upper side of from that period, that is when Merkel put forward the Franco-German plan together with Macron (18 May), thereby irritating the Frugals (who reacted by presenting their counterproposal on May 23), and laying the foundations for the Commission proposal, which was presented a week later on May 26.

Figure 2. EU leaders’ positions on policy responses to the crisis, ranging from ‘national responsibility’ (negative values) to ‘risk pooling’ (positive values): trends over time, 10-day moving averages.

Despite revived divisions over hot policy issues (see also the partial resurgence of antagonistic tones around mid-June in ), we observe clear convergence of policy positions in the final rush towards the NGEU plan adoption, which came a few weeks after the start of the German presidency at the end of a long and tense European Council meeting in July (17–21). This is reflected in , whereby the gap between the lines for the Frugals and Southern countries closes around an overall pro-risk-pooling common position in July. The resulting compromise solution, although not so ambitious as that advocated by the Southern bloc, still constituted an unprecedented integrative step for the EU since it involved the European Commission undertaking massive borrowing on the capital markets for the first time (up to €750bn) to provide grants (up to €390bn) and loans to economically weak member states.

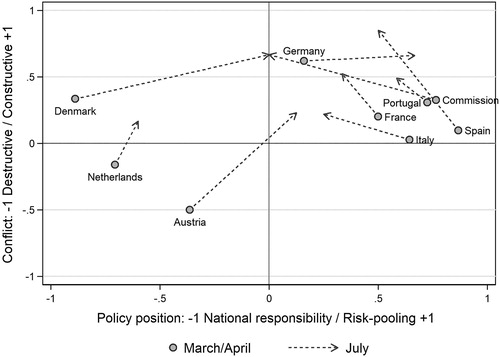

takes stock of the progress made by the eight countries along our two key-dimensions – the nature of the conflict and the policy stance – showing the moves from the positions taken at the peak of the conflict parabola (the round markers: average values mid-March/end of April) to those in July when the NGEU plan was adopted (the arrows, pointing to the July averages). Once again, the initial polarisation is apparent, with frugal countries located in the left quadrants (national responsibility), Southern states and the Commission located at the opposite end, and Germany taking a middle position. As suggested by the arrows, all countries by and large converged towards a ‘central equilibrium’ between risk pooling and national responsibility, with the notable exception of Germany, which moved further to the centre of the upper-right quadrant towards a more solidaristic pro-risk-sharing policy stance. Most importantly, even at the peak of the conflict in March/April (the markers in ), all states but the Netherlands and Austria were on average leaning towards ‘constructive’ confrontational tones. The arrows for these two most antagonistic countries cross the horizontal 0 line in , meaning that Austria and the Netherlands also eventually abandoned an utterly destructive conflictual tone and, despite persisting divergence on some specific policy issues, adopted more constructive attitudes.Footnote 12

Figure 3. Country positions along the two crucial analytical dimensions of conflict tone and policy position. Dots: starting positions (average 16 March–3 May); arrows: arrival position (July average).

In sum, two camps confronted each other in the COVID-19 crisis, engaging in a bellicose tug of war rooted in profoundly different policy preferences and conceptions of the EU. After the April Council meeting, the two camps gradually toned down their clash in the communicative sphere, with a view to reaching a difficult yet ambitious final agreement at the end of July. Germany and France certainly took the lead in devising a first blueprint for a compromise agreement. While French President Macron and his Finance Minister Le Maire were firm on their pro-risk-pooling stance, Germany shifted from siding with the Frugal countries to promoting solidaristic policy options. Despite this notable change in substantive policy positions, German leaders carefully avoided destructive-conflictual tones and sought the compromise in the name of European solidarity, thus playing a key role as mediators. The Social-Democratic Finance Minister Scholz had been leaning towards EU-solidaristic solutions since the beginning of the COVID crisis. The crucial actor in the ideational shift, ultimately tilting the European balance, was the Christian-Democratic Chancellor. Merkel shifted towards policy positions from which she (and her former epistemic entourage) had long held back, like fiscal transfers and increased risk sharing with highly indebted Southern economies. The next section delves deeper into Merkel’s communicative strategy to justify the shift and build consensus around it.

Defending the EU polity through public communication: Angela Merkel’s speeches

During the sovereign debt crisis in the early 2010s, Angela Merkel was strongly criticised for her lack of leadership and a tendency to postpone decisions until the last minute. Joschka Fischer, a former foreign minister and influential public figure, accused her of having broken the backbone of all German policies: Europeanising problems and solutions and making Germany increasingly European. With her stubborn closure towards financial solidarity with the countries of the South, Merkel had followed the opposite path: bending Europe to German preferences and interests (Fischer Citation2015; but see also Habermas Citation2015; Offe Citation2015).

The preceding section has shown that during the COVID-19 crisis Merkel played a much different and constructive role. A number of factors facilitated Merkel’s turn. Right before the outburst of the epidemic, she had publicly announced her determination not to run again for the Chancellery. The prospective withdrawal from the partisan arena attenuated those constraints coming from her national legitimation basis, which had proved so powerful in the past (Van Esch Citation2017). The relatively effective management of the public health emergency pleased German voters, who throughout the crisis continued to show high levels of support for Merkel personally and the government as a whole.Footnote 13 The arrival of Scholz at the Finance Ministry and the replacement of Schäuble’s ordoliberal entourage with officers closer to the SPD provided the political and ideational space for abandoning fiscal intransigency. This change facilitated interactions with French financial technocrats and allowed Merkel to reach an agreement with Macron. The prospect of the German rotating EU Presidency, due to start in July, also served as an incentive to be proactive and compromise oriented. Finally, the increasingly shared perception that monetary policy alone could not stabilise the economic situation, repeatedly emphasised during these months by ECB’s president Christine Lagarde (Arnold Citation2020), and made even more imperative after the German Constitutional Court’s complaints on ECB’s bond-buying programmes, prompted EU leaders to take action on the fiscal side. Net of all such factors, Merkel’s communicative strategy during the COVID-19 crisis revealed nonetheless some distinctive features which are typical of ‘purpose-oriented’ or even ‘conviction leadership’, as opposed to mere ‘consensus-seeking politics’ (Müller and Van Esch Citation2020). Conviction leadership rests in fact on the promotion of beliefs and values running against the perceived interests of the leader’s main constituency and/or the presence of a clearly recognisable ethical dimension (Helms et al. Citation2019).

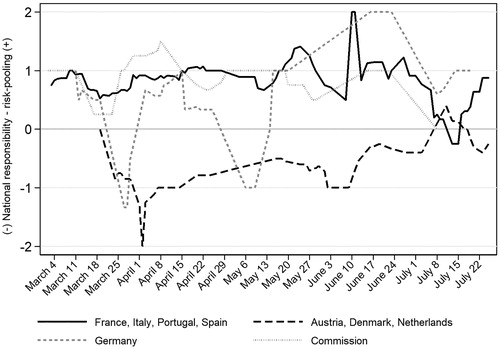

Our speech analysis has tried to detect, in the first place, the narrative frames used by the Chancellor to characterise the crisis. Through our sentence-based coding, we have extracted all content related to the two main analytical components of crisis frames, i.e. challenges and responses. Three frames have clearly emerged (). For the public health frame, the overarching challenge was the pandemic as such, and the appropriate response was mutual collaboration. The economic frame pointed to disturbances in the internal market and, later, to the recession, requiring a fiscal stimulus and organised cross-national financial solidarity. For the political frame – the last to emerge – the key challenges were increasing conflicts both between and within countries. Here, the Chancellor called for an extraordinary response, based on bold solidaristic initiatives.

With the intensification of the crisis, the sentiment of each frame becomes increasingly apprehensive, making use of the expressive repertoire described in the methodology section. Thus, within the public heath frame, the pandemic gets dramatised as a ‘natural disaster’ (6 April) and as ‘the greatest test ever’ (18 April). The reference to initiatives of practical help, at most inspired by ‘sympathy’ (11 March), gets charged up with increasing pathos: for example, ‘Europeans have proved to be citizens with heart and reason, ready to do something for their fellow human beings, capable to view the big picture’ (23 April). In the economic frame, the warnings about possible interruptions of the free movement of goods, ‘so important for Germany’s car industry’ (17 March) is replaced by a generalised plea for a fully-fledged defence of the internal market as such, defined as a ‘higher-order good’ (27 March) and a precondition for European prosperity. In addition, the EU economy is explicitly acknowledged as a common space and valorised as bringing about precious collective advantages. Since a potentially disruptive systemic crisis is looming, generating a ‘massive slump’ (18 April), there is also a growing proliferation of fervent appeals to cohesion and financial solidarity organised at the EU level. The political frame betrays in its turn an increasing alarm about polity disruption. And – as we shall see in a moment – this frame served as the main leverage for Merkel’s strenuous strategy of polity maintenance.

While the three frames partly intertwine with each other in some of the speeches, our analysis reveals a clear temporal sequence. shows the frequency of sentences which, in the various speeches, are attributable to each frame. The public health frame prevailed at the beginning of the crisis but was then superseded by the economic frame. The political frame made its appearance in April and then became by far the dominant one. Merkel used it both for supporting the EU and promoting ‘common understandings despite diverging positions’ (13 July) and for warning about ‘a return of nationalism’ and ‘anti-democratic forces, the radical, authoritarian movements [which] are only waiting for economic crises in order to then exploit them politically’ (18 June).

As is typical of polity-oriented communication, Merkel’s speeches used a variety of metaphors aimed at activating positive orientations towards the EU (listed in Table A3 in the online appendices). Three trends stand out: (1) an increase of ‘communitarian’ symbols, (2) their ‘temporalisation’ by means of explicit linkages to a shared past and a common future and (3) their expression through an emotionally charged language. Sentences (or clusters of sentences) containing symbols also tended to teem with values (the above-mentioned political-ethical dimension). This is especially the case for communitarian symbols (references to cohesion, solidarity, togetherness, commonality, respect for fundamental rights and democracy and so on). The turning point was the speech of 23 April (see below). The reference to solidarity and cohesion peaked (more than 30%)Footnote 14 during the joint press conferences by Merkel and Macron: here the German Chancellor engaged in a great effort of normative justification for risk-sharing. The inaugural speech of the German Presidency on July 8 was also ripe with normative references: solidarity and cohesion featured in 21% of the sentences; values linked to democracy, liberty and rights featured in 23% of the sentences, and emotional expressions regarding the importance of the EU featured in 16% of the sentences.Footnote 15

In summary, our data show that in her public speeches during the COVID-19 crisis Merkel made a significant political investment in EU polity maintenance and EU re-legitimation. High levels of domestic support in Germany – contrasting with Macron’s domestic situation, which was more unstable and strongly polarised (Jørgensen et al. Citation2021; Kritzinger et al. Citation2021; Smith Citation2020) – enhanced the ‘leadership capital’ (Helms and Van Esch Citation2017) that Merkel could spend in favour of a more solidaristic EU. Persuading German voters was not an easy task, given the Chancellor’s own ‘rhetorical entrapment’ in the moral hazard arguments often used during the previous decade (Katzenstein Citation2013). Thus, Merkel was extremely attentive to justifying her polity-maintenance effort. To this aim, she used first an economic rationale, according to which German prosperity depends on the internal market and, more generally, on the correct functioning and the overall equilibrium of all European economies. Then, she started to use a political rationale, according to which supporting European integration is in the interest of the German state.

The most emblematic example of this latter rationale can be found in the speech pronounced on April 23 in front of the Bundestag a few hours prior to the European Council which sealed ‘reconciliation’ after the first phase of harsh conflict. Here Merkel cautiously brings up, in the first part of her speech, the issue of German interest vis-à-vis the EU. After a series of rhetorical questions, she unveils her own view: ‘For us in Germany, the commitment to a united Europe is part and parcel of our reason of state […] We are a community of fate’. And later on she adds: ‘Europe is not Europe if it does not stand up for one another in times of indebtedness’. The speech concludes with a passionate plea for a European Germany: ‘What is valid in Europe is also the most important thing for us in Germany’.

There is no space here to present the elaborations of this reasoning that Merkel offers in later speeches. One element, however, deserves to be stressed again, as it constitutes the political cornerstone of the Chancellor’s strategy. Preserving the EU polity as such requires a dedicated exercise of leadership for safeguarding the conditions for pan-European ‘ever closer’ cooperation, based on cohesion and solidarity. Persuading German voters that the ties between the German polity and the EU polity are the safest guarantee of prosperity, security and democracy is in its turn the precondition for German leaders to be able to undertake the exercise and invest in EU polity building.

Conclusions

The dramatic socio-economic crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic reawakened those acute tensions between Northern and Southern member states which had already shattered the EU several times during the 2010s. The risk of a new ‘existential crisis’ was, however, successfully averted. Since the end of April, EU national leaders adopted a more constructive approach and were eventually able to reach an ambitious distributive compromise on how to relaunch the EU economy through deeper European fiscal integration. Through discourse analysis, this article has documented the gradual shift from antagonism to appeasement in EU leaders’ communicative discourses and, in particular, has reconstructed the symbolic strategy articulated by the German Chancellor Angela Merkel in order to promote this shift. We have argued that the latter has responded to a deliberate endeavour of ‘polity maintenance’ – i.e. keeping the EU polity together, regardless of deep interest-based divisions. Rather than arguing for discourse as a single explanatory variable, the argument of this article is that the described discursive dynamics constitute one key factor – along with others, such as institutional logics and economic imperatives – in accounting for the establishment of the NGEU package. This was achieved not only by providing the ideational context within which the European Council agreement of 21 July could take place but also by successfully legitimising said agreement in front of the wider European publics: as two post-agreement surveys have shown, support for the new joint European fiscal instrument is high not only in the European South but also in Germany and the Frugal Four (Bremer et al. Citation2020; Dennison and Zerka Citation2020).

In addition to accounting for the peculiar unfolding of the COVID-19 crisis, our article makes two more general contributions. First, by drawing on neo-Weberian as well as discursive approaches to institutional analysis, we have shown the value of the analytical separation between the policy and the polity level and the value of the key role played by polity maintenance and its main instrument – i.e. a communicative discourse based on a recognisable set of symbols, values and expressive repertoire. Second, we have unveiled aspects of EU politics that challenge some mainstream assumptions. Against liberal intergovernmentalism, we have found that integration is largely driven by a quintessentially political logic that is linked to the foundational imperative of safeguarding the bounding, binding and especially bonding preconditions of interest-based interactions. Against post-functionalism, our analysis invites reconsideration of both the extent of dissensus and its constraining effects. There seems to be both an underestimated wealth of support for cohesion and solidarity among EU citizens (also in the North) as well as much wider-than-expected room for committed leaders to ‘steer’ rather than defer to public orientations vis-à-vis the EU (Ferrera Citation2019). For all Europhiles, this may be a reason for political optimism; for EU scholars, it is an incentive to delve deeper into the supply side of the integration process and to better theorise and investigate the agency of individual leaders and their capacity to make responsible polity-oriented choices when needed.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.3 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank three anonymous reviewers of West European Politics for their helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript, and Laura Cabeza for her assistance on speech analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential competing interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Data available on request from the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maurizio Ferrera

Maurizio Ferrera is Professor of Political Science at the University of Milan. He is currently one of the three PIs of the ERC Synergy project ‘SOLID’ (www.solid-erc.eu). He has written extensively on the welfare state and European integration and his articles have appeared in major international journals. In 2005, he authored The Boundaries of Welfare (Oxford UP) and is currently completing a manuscript on Politics and Social Visions (Oxford UP, forthcoming). In 2020, he was awarded the Mattei Dogan Prize by the International Political Science Association. [[email protected]]

Joan Miró

Joan Miró is Postdoctoral Researcher at the Department of Social and Political Sciences, University of Milan. His research interests include comparative social policy, discourse analysis and EU integration theory. He has published in Policy Studies, Review of International Political Economy, Socio-Economic Review, Social Politics and Constellations, amongst others. [[email protected]]

Stefano Ronchi

Stefano Ronchi is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Department of Social and Political Sciences, University of Milan. His research interests include comparative welfare state analysis and the politics of European integration. His articles have appeared in journals such as the Journal of Social Policy, International Political Science Review and South European Society and Politics. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 According to Weberian theory, for ‘responsible leaders’, preserving the political community is a superordinate cause (‘Sache’) that must be served (Waters and Waters Citation2015).

2 The shift to constructive conflict for the sake of extending the time horizon for decision-making is in fact crucial for activating the process of ‘emergency politics that buys time for democracies’ as described by Ganderson et al. (Citation2021).

3 Schmidt (Citation2008) distinguishes between ‘coordinative discourse’ – consisting of actors at the centre of the policy-making process, who are involved in the elaboration of programmatic ideas and policies – and ‘communicative discourse’ – the actors at the centre of political communication involved in the presentation, deliberation and legitimisation of political ideas to the general public.

4 Straw-in-the-wind tests allow for an initial assessment of a causal hypothesis but do not yield conclusive results in terms of necessary or sufficient causes.

5 We do not include Sweden – the remaining member of the so called ‘Frugal Four’ coalition – because, in a preliminary analysis, it showed a very scarce presence in the press.

6 Ten policy issues dominated the risk-sharing discussion: 1) flexibilisation of the Stability and Growth Pact’s fiscal rules, 2) appropriateness of the European Stability Mechanism, 3) establishment of a European joint debt guarantee, 4) introduction of new EU taxes, 5) introduction of temporary fiscal transfers, 6) governance mechanisms of these new instruments (i.e. debate on the so-called ‘conditionality’), 7) size and composition of the 2021–2027 Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), and 8) size and composition of the required EU countercyclical fiscal stimulus. We have not coded statements on monetary policy or on the protection of the MFF in case of rule-of-law deficiencies, as these two topics are not related to greater fiscal integration.

7 As such, although it also implies some degree of risk sharing, the preference for the European Stability Mechanism to provide credit has been coded as −1, as it implies much less risk sharing than grant-based options in the concrete policy debate.

8 Online appendix 3 provides details on the selection of speeches and on the codebook. The speech database is available from the authors.

9 Details of the survey are found in Online appendix 1.

10 Hoekstra stated that issuing coronabonds would incentivise ‘moral hazard’ and called on the EU to ‘investigate countries which say they have no budgetary margin to deal with the effects of the crisis’ although the eurozone had grown for seven consecutive years. At the press conference following the March 26 Council, Costa reacted by calling that statement ‘repugnant’ (Euractiv Citation2020a). See also Ganderson et al. (Citation2021) for a detailed summary of the events.

11 After the video call of the Council meeting, the Dutch PM Mark Rutte even denied the tensions that had emerged since March: ‘Tensions, if they were there at all, are not there any longer’ (Euractiv Citation2020b).

12 The leftward shift of Italy (and, to some extent, of the Commission) in Figure 1 is due to the general openness to the use of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM, coded as ‘national responsibility’ in our database) in the last phase of the negotiations. The ESM had generated much opposition in Italian politics. PM Conte and the Finance Minister Gualtieri, however, had started to show openness to the use of the ESM (without financial conditionality) since mid-April and confirmed their position in July.

13 In April 2020, a survey attributed to Merkel had an approval score of 74%. Markus Söder – CSU’s leader – obtained 72% and Olaf Scholz – SPD’s leader – 63% (NTV Citation2020). In May 2020, Merkel’s approval rate reached a record high of 75% (RND Citation2020).

14 By incidence we mean the percentage of sentences including the two words over the total of sentences of a given speech which obtained a pertinent polity-maintenance code as per our codebook (online appendix 3).

15 In this speech words related to democracy, freedom and rights as well as emotional expressions reached their highest incidence over the whole period.

References

- Almond, Gabriel A. , and G. Bingham Powell (1978). Comparative Politics: A Developmental Approach . Boston: Little, Brown and Co.

- Arnold, Martin (2020). ‘Lagarde Warns of Threats as ECB Leaves Policy on Hold’, Financial Times, July 16.

- Borriello, Arthur , and Amandine Crespy (2015). ‘How Not to Speak the F-Word: Federalism between Mirage and Imperative in the Euro Crisis’, European Journal of Political Research , 54:3, 502–24.

- Bourdieu, Pierre (1991). Language and Symbolic Power . London: Polity Press.

- Bremer, Bjorn , Theresa Kuhn , Maurits Meijers , and Francesco Nicoli (2020). ‘The EU Can Improve the Political Sustainability of the Next Generation EU by Making it a Long-Term Structure’, VOXEU-CEPR, November 4, available at: https://voxeu.org/article/improving-political-sustainability-next-generation-eu (accessed 7 January 2021).

- Bull, Peter (2007). ‘Political Language and Persuasive Communication’, in Ann Weatherall , Bernadette M. Watson , and Cindy Gallois (eds.), Language, Discourse and Social Psychology . London: Palgrave, 255–75.

- Chazan, Guy , Sam Fleming , Victor Mallet , and Jim Brunsden (2020). ‘Coronavirus Crisis Revives Franco-German Relations’, Financial Times, April 13.

- Chong, Dennis , and James N. Druckman (2007). ‘Framing Theory’, Annual Review of Political Science , 10:1, 103–26.

- Collins, Randall (1975). Conflict Sociology . New York: Academic Press.

- Collins, Randall (1986). Weberian Sociological Theory . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dennison, Susi , and Pawel Zerka (2020). ‘The Transformative Five: A New Role for the Frugal States after the EU Recovery Deal’, ECFR Policy Brief.

- Die, Welt (2020). ‘Die Deutschen halten sich noch immer für eine überlegene Rasse’, 1 April 2020.

- Euractiv (2020a). ‘Portugal Slams Dutch Finance Minister for “Repugnant” Comments’, 30 March 2020.

- Euractiv (2020b). ‘EU Leaders Agree Plans for “Unprecedented” Stimulus against Pandemic’, 23 April 2020.

- Ferrera, Maurizio (2019). ‘EU Solidarity: A Freestanding Political Justification’, paper presented at the Conference "Is Europe Unjust?", EUI, Florence, 16-17 September.

- Fischer, Joschka (2015). Scheitert Europa? Cologne: Kiepenheuer & Witsch.

- Gaspar, Rui , Claudia Pedro , Panos Panagiotopoulos , and Beate Seibt (2016). ‘Beyond Positive or Negative: Qualitative Sentiment Analysis of Social Media Reactions to Unexpected Stressful Events’, Computers in Human Behavior , 56, 179–91.

- Ganderson, Joseph , Waltraud Schelkle , and Zbigniew Truchlewski (2021). ‘Buying Time for Democracies? European Union Emergency Politics in the Time of Covid’, West European Politics .

- Habermas, Jürgen (1989). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere . Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Habermas, Jürgen (2015). The Lure of Technocracy . Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Helms, Ludger , and Femke A. W. J. Van Esch (2017). ‘Turning Structural Weakness into Personal Strength: Angela Merkel and the Politics of Leadership Capital in Germany’, in Mark Bennister and Ben Worthy (eds.), The Leadership Capital Index: A New Perspective on Political Leadership . Oxford: OUP, 28–44.

- Helms, Ludger , Femke A. W. J. Van Esch , and Beverly Crawford (2019). ‘Merkel III: From Committed Pragmatist to “Conviction Leader”?’, German Politics , 28:3, 350–70.

- Hutter, Swen , Edgar Grande , and Hanspeter Kriesi (2012). Politicising European Integration . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jørgensen, Frederik , Alexander Bor , Marie Fly Lindholt , and Michael Bang Petersen (2021). ‘Lockdown Evaluations during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic’, West European Politics .

- Katzenstein, Suzanne (2013). ‘Reverse-Rhetorical Entrapment: Naming and Shaming as a Two-Way Street’, Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law , 46, 1079–98.

- Kritzinger, Silvia , Martial Foucault , Romain Lachat , Julia Partheymüller , and Carolina Plescia (2021) ‘Rally around the Flag: The COVID-19 Crisis and Trust in the National Government’, West European Politics .

- Koopmans, Ruud , and Paul Statham (2010). ‘Theoretical Framework, Research Design, and Methods’, in Ruud Koopmans and Paul Statham (eds.), The Making of a European Public Sphere: Media Discourse and Political Contention . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 34–59.

- Ladi, Stella , and Dimitris Tsarouhas (2020). ‘EU Economic Governance and Covid-19: Policy Learning and Windows of Opportunity’, Journal of European Integration , 42:8, 1041–56.

- Matthijs, Matthias (2020). ‘Hegemonic Leadership Is What States Make of It: Reading Kindleberger in Washington and Berlin’, Review of International Political Economy , 1–28. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1813789

- Mio, Jeffrey S. , Ronald E. Riggio , Shana Levin , and Renford Reese (2005). ‘Presidential Leadership and Charisma: The Effects of Metaphor’, The Leadership Quarterly , 16:2, 287–94.

- Müller, Henriette , and Femke A. W. J. Van Esch (2020). ‘The Contested Nature of Political Leadership in the European Union: Conceptual and Methodological Cross-Fertilisation’, West European Politics , 43:5, 1051–71.

- NTV (2020). ‘Merkel bekommt die Top-Bewertung’, available at: https://www.n-tv.de/politik/Merkel-bekommt-die-Top-Bewertung-article21707107.html (accessed 7 January 2021).

- Offe, Claus (2015). Europe Entrapped . Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Pansardi, Pamela , and Francesco Battegazzorre (2018). ‘The Discursive Legitimation Strategies of the President of the Commission: A Qualitative Content Analysis of the State of the Union Addresses’, Journal of European Integration , 40:7, 853–71.

- Papadimitriou, Dimitris , Adonis Pegasiou , and Sortirios Zartaloudis (2019). ‘European Elites and the Narrative of the Greek Crisis: A Discursive Institutionalist Analysis’, European Journal of Political Research , 58:2, 435–64.

- Pollack, Mark A. (2005). ‘Theorizing the European Union: International Organization, Domestic Polity, or Experiment in New Governance?’, Annual Review of Political Science , 8:1, 357–98.

- RND (2020). ‘Umfrage zur Corona-Krise: Merkel bekommt Zuspruch – Deutsche sorgen sich um Wohlstand’, available at https://www.rnd.de/wissen/umfrage-zur-corona-krise-merkel-bekommt-zuspruch-deutsche-sorgen-sich-um-wohlstand-XTBBS2C22V26RNQADDRWZKNSL4.html (accessed 7 January 2021).

- Sartori, Giovanni (2016). Elementi di Teoria Politica . Bologna: Il Mulino.

- Schmidt, Vivien (2008). ‘Discursive Institutionalism: The Explanatory Power of Ideas and Discourse’, Annual Review of Political Science , 11:1, 303–26.

- Smith, Justin E. H. (2020). ‘France’s President Stands on Principle, but Stumbles on Practice’, Foreign Affairs, November 2020.

- Statham, Paul , and Hans-Jorg Trenz (2015). ‘Understanding the Mechanisms of EU Politicization: Lessons from the Eurozone Crisis’, Comparative European Politics , 13:3, 287–306.

- Stemler, Steve (2000). ‘An Overview of Content Analysis’, Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation , 7, 171–6.

- Suchman, Mark C. (1995). ‘Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches’, Academy of Management Review , 20:3, 571–610.

- Van Esch, Femke A. W. J. (2017). ‘The Paradoxes of Legitimate EU Leadership. An Analysis of the Multi-Level Leadership of Angela Merkel and Alexis Tsipras during the Euro Crisis’, Journal of European Integration , 39:2, 223–37.

- Van Evera, Stephan (1997). Guide to Methods for Students of Political Science . Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press.

- Von der Leyen, Ursula (2020). ‘Speech by President Von der Leyen at the European Parliament Plenary on the EU Recovery Package’, 27 May 2020.

- Waters, Tony , and Dagmar Waters (2015). Weber's Rationalism and Modern Society . London: Palgrave.