Abstract

During international crises, trust in government is expected to increase irrespective of the wisdom of the policies it pursues. This has been called a ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect. This article examines whether the COVID-19 crisis has resulted in such a rally effect. Using multi-wave panel surveys conducted in Austria and France starting from March 2020, in the article it is examined how government trust was affected by the perceived threats to the nation’s health and economy created by the pandemic as well as by the perceived appropriateness of the government’s crisis response. A strong rally effect is shown in Austria, where trust was closely tied to perceived health risks, but faded away quickly over time. Perceptions of government measures mattered, too, while perceived economic threat only played a minor role. In France, in contrast, a strong partisan divide is found and no rally effect.

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1925017 .

During international crises, support for the government is expected to increase even regardless of the wisdom of the policies it pursues (Mueller Citation1970, Citation1973). This effect is commonly called the ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect. As international crises create unexpected and profound challenges to the status quo, such an increase in support for the government helps politicians in objectively bad times to enact specific emergency policies (Davis and Silver Citation2004). While political support is critical for society’s functioning even under normal circumstances (Zmerli and van der Meer Citation2017), trust in the government in times of crisis becomes ever more important as it may serve as a resource for compliance with potentially life-saving measures.

The current COVID-19 pandemic can be considered a case of such an international crisis inflicting sudden and unprecedented hardship on societies at large. Importantly, the COVID-19 pandemic has simultaneously posed both health and economic threats. While the spreading of COVID-19 led to (the fear of) the collapse of the healthcare system, increasing numbers of patients and death tolls, containment measures brought the economic system to a standstill resulting in a severe economic downturn and high unemployment rates. COVID-19 thus created simultaneously two types of crises that national governments had to handle. While COVID-19 and the health crisis it provoked did hardly result from government actions themselves but rather was brought to the country as a ‘foreign’ shock (e.g. Baum Citation2002), the subsequent economic crisis was in part a direct consequence of the various severe lockdown measures that governments were taking to contain the health crisis. This soon provoked debates about the appropriateness of the crisis response by the government.

In this article, we study the underpinnings and temporal dynamics of trust in government during the COVID-19 crisis. Specifically, we investigate whether COVID-19 created a ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect. We argue that a ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect should manifest itself in a direct link to threat perceptions rather than in a relationship with the perceived quality of the crisis management by the government. To examine this conjecture, we assess the effects on trust in the national government of both types of consequences of the COVID-19 crisis (i.e. the perceived health and economic threats) simultaneously, and contrast their role with the effects of the perceived appropriateness of government measures. We argue further that opposition supporters should revert quickly to their normal critical stance towards the government as soon as the perceived level of health threat decreases.

We test these expectations in two countries, namely Austria and France, which differ substantially in terms of the initial level of trust in government, with the Austrian government enjoying average levels of support, and trust in government being markedly lower in France. While both countries were severely hit by COVID-19 from both a health and economic perspective, the reactions of the opposition parties towards the governments’ crisis management differ in the two countries: in Austria an all-party support of the government’s COVID-19 measures was immediately reached, while in France in the lower chamber the left-wing opposition never supported the anti-COVID-19 legislation. We rely on two multi-wave panel surveys, conducted independently in these two countries between March and June/July 2020, that included similar questions. The panel structure of the data allows following the same respondents across the turbulent weeks of March and April 2020, and then through a period when lockdown measures were successively relieved or even lifted. Overall, the article aims to contribute to our understanding of public opinion during the COVID-19 crisis in line with the aim of this Special Issue.

The article’s structure is as follows: first, we outline the underlying theoretical considerations and derive several hypotheses based on previous research; next, we provide further details on the data and methods used, and on the two countries studied; and finally, we present our results and conclude with a discussion of the theoretical and practical implications of our findings.

Theoretical considerations and previous research: the COVID-19 pandemic and trust in government

The COVID-19 pandemic has created unique challenges to political systems and, thus, to the political status quo. Sudden crisis situations often result in an increase in government support caused by a ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect (Mueller Citation1970). These effects have mainly been observed in connection with crises that are sudden, dramatic, and international in scope (Baker and O’Neal Citation2001), which is often the case with military conflict and terrorist attacks (e.g. following the 9/11 terror attacks and the US-led military intervention ‘Operation Desert Storm’ (Hetherington and Nelson Citation2003)). The magnitude and longevity of these rally effects have been varying from huge effects (e.g. 35 percentage points increase in presidential approval after 9/11) lasting for more than a year (Gaines Citation2002), to medium and smaller effects (e.g. 10 to 20 percentage points increase) lasting only for a few weeks or months (Hetherington and Nelson Citation2003).Footnote 1 One argument suggests that rally effects are due to the fact that citizens turn towards political actors who can enact policies that shall protect them from the risks international crises pose (Albertson and Gadarian Citation2015). Another argument sees people offsetting the uncertainty and distress created by international crises by increasing trust in internal actors such as the government (Druckman and McDermott Citation2008). In both cases, international crises provide politicians with the possibility to strengthen citizens’ faith in their competences and decision-making.

Previous research has shown that threat perceptions caused by international crises can indeed increase government trust (e.g. Hetherington and Nelson Citation2003; Albertson and Gadarian Citation2015).Footnote 2 Yet, the emerging literature about the political consequences of the COVID-19 crisis offers mixed findings in this regard. Analysing 15 Western European countries, Bol et al. (Citation2021) show that the lockdown has increased satisfaction with democracy, trust in government and (albeit to lesser extent) vote intentions for the party of the Prime Minister/President. However, when they tried to test whether such an increase in political support was due to the health crisis itself, and its incidence, they could not detect a ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect, at least not in the short temporal interval of their survey (less than a month). Other studies instead, conducted in the immediate aftermath of the implementation of lockdown measures, observed increases in government support in Canada (Merkley et al. Citation2020), Bavaria (Leininger and Schaub Citation2020), Sweden (Esaiasson et al. Citation2020), and the Netherlands (Schraff Citation2020), as well as a rise in the popularity of leaders such as Angela Merkel, Emmanuel Macron, Justin Trudeau, or Boris Johnson (The Economist, 9 May Citation2020). Meanwhile, the opposite effect could be observed in other countries, with declining levels of government support, such as in the United States (Gadarian et al. Citation2021), and lower popularity rates for leaders like Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil or Shinzo Abe in Japan (The Economist Citation2020).

The overwhelming majority of these studies has looked at the aggregate-level effect of the health crisis (e.g. number of infections or deaths) on government support. Building up on this research, we focus instead on the individual-level dynamics of government trust in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we investigate the effects of individual threat perceptions, cross-sectionally and over time. At the same time, we assess the role of perceptions of the appropriateness of government measures as a potential alternative explanation of why people trust the government in times of crisis. We study these perceptions simultaneously for government and opposition party supporters.

Hypotheses

As emphasised, the rally effect should manifest itself in high levels of government trustFootnote 3 that are directly linked to the perceived threats posed by the crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic is both a health and an economic crisis. Many political leaders faced the dilemma that measures aiming at containing health-related threats may reinforce the negative economic consequences of the pandemic (e.g. Baekgaard et al. Citation2020). Overall, both policy areas necessitate coordinated government action to attenuate the threats that accompany them, and both of them may, in principle, affect citizens’ level of trust in government.

Starting with the health aspect, recent research confirms that citizens react with anxiety when confronted with the existential threat posed by COVID-19 and its potential impact on the health and well-being of the population (Tabri et al. Citation2020). Similar to what happens after terror attacks, governments may, once sudden health threats emerge, ‘[…] function as aides for citizens to manage a deep-seated, primal fear of death’ (Baekgaard et al. Citation2020: 6), and thus may be less blamed for health-related threats. For these reasons, we expect a positive relationship between the perceived health threats and the degree of trust in government.

The expected surge in government trust that characterises a ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect due to the health crisis should present another important feature: the levels of trust in government should be subject to little or no partisan polarisation. That is, the higher level of government trust due to high perceptions of a health threat should not exclusively be driven by government party supporters, but it should be observable among all partisan groups. We know that people’s attitudes towards the government are, in normal times, strongly shaped by their partisanship (Evans and Chzhen Citation2016; though some have questioned this argument, e.g. Lewis-Beck et al. Citation2008). However, in times of crisis, the literature has shown that a cross-partisan consensus is more likely to happen (e.g. Merkley et al. Citation2020), also affecting the trust levels of opposition parties’ supporters. This may particularly be the case when opposition parties support the policies taken by the government to address the crisis (e.g. Brody Citation1984). In such a situation, and when the level of perceived threat is high, the difference in trust between supporters of incumbent parties and other party supporters should be reduced. Based on these considerations, we hypothesise that:

Hypothesis 1 : A larger perceived threat to public health is associated with a higher level of trust in the government.

The health threats caused by COVID-19 were imposed on citizens by external circumstances and rather unexpectedly, like terror attacks. To some extent, this is true for the economic threats as well, with unemployment numbers surging dramatically in the early stage of the crisis. The economic threats, however, were more directly caused by the governments’ decisions bringing the economic life with the implemented lockdown measures to an immediate and unprecedented halt. From the literature on retrospective economic voting (e.g. Anderson Citation2007; Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier Citation2000), we know that governments are blamed for bad economic performance. Even more importantly, Chanley et al. (Citation2000) have also shown that economic pessimism reduces trust in government substantially. Thus, citizens could also hold the government responsible for the economic consequences of the pandemic and sanction it accordingly with lower levels in government trust. However, as conflicting motives – threat perceptions and the accountability mechanism – might cancel each other out, we expect the following:

Hypothesis 2: The association between perceived economic threats and trust in government is weaker, or even in the opposite direction, compared to the association between perceived health threats and trust in government.

Apart from health and economic threats, the governments’ performance in handling the crisis might play an important role. Most notably, Bol et al. (Citation2021) conclude that the surge in government trust amidst the COVID-19 pandemic was mainly driven by assessments of the government’s performance in handling the crisis rather than by a rally effect. To speak of a ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect, they argue, the increased level of trust in government should be due to the crisis itself, rather than a reaction to the policies implemented by the government in a logic of ‘reward’ and ‘punishment’ and voter gratitude for beneficial policy decisions (e.g. Key Citation1966; Bechtel and Hainmueller Citation2011). Hence, as citizens’ perceptions of the government’s crisis management may provide an alternative (or complementary) explanation, it seems essential to assess its relevance alongside that of threat perceptions. This leads to our third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: The perception of government’s measures to deal with the COVID-19 crisis as being too extreme (or not sufficient) will have a negative association with trust in government.

Note that Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 actually result in two different types of observable implications: first of all, between groups of citizens cross-sectionally, and second, longitudinally over time. Cross-sectionally, following Hypothesis 1, we expect higher trust among citizens who perceive more health threats compared to citizens with lower health threat perceptions. We assume this to be true across the partisan spectrum, but that it should be most notably visible among the opposition party supporters, creating a moment of unity amidst the crisis. For the economy, due to conflicting motives between threat perceptions and accountability mechanisms, we conjecture based on Hypothesis 2 that the association between threat perceptions and trust will be weaker or negative. Hence, there will be fewer differences in trust in government across varying levels of perceived economic threat. When it comes to performance of the government, we expect based on Hypothesis 3 that citizens who perceive the government’s measures as too extreme or insufficient have lower trust compared to those perceiving these measures to be appropriate.

With regards to longitudinal effects over time, we expect based on Hypothesis 1 that if the level of health threat perceived by a given citizen declines over time, his or her trust in government should weaken. In other words, a decrease in perceived levels of threat could explain the fading away of the ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect often observed in the existing literature (e.g. Gaines Citation2002; Hetherington and Nelson Citation2003). In contrast, a decline in perceived economic threats over time, following Hypothesis 2, would be expected to result in only rather little change in government trust due to the conflicting underlying motives. Yet, in the spirit of Hypothesis 3, a decrease in government trust at the individual level could also (or alternatively) be related to a decline in the perceived appropriateness of the government’s measures.

Finally, we have a longitudinal hypothesis that focuses explicitly on the differences between partisan groups. As outlined, the rally effect is supposed to bridge the gap in trust between supporters of the government and the opposition. However, as the crisis continues, partisan differences should again become more evident with a return to a more standard pattern of partisan polarisation. This ‘normalisation’ is expected to be mainly due to the fact that declining health threat perceptions will lower citizens’ deep-seated, primal fear of death (Baekgaard et al. Citation2020). Citizens will resort to long-standing partisan identities when assigning trust to the government. With opposition parties increasingly returning to ‘normal’ daily political competition (Chowanietz Citation2011), trust in government among opposition party supporters is expected to decline over the months, leading to our fourth hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: The trust gap between supporters of government parties and supporters of the opposition should grow larger over time.

Data and methods

In order to test our hypotheses, we make use of two unique online panel surveys conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic in Austria and France. Data for France were collected as part of the project ‘Citizens’ Attitudes Under the COVID-19 Pandemic’. The data collection of this survey started on March 16, 2020, with weekly panel waves until early May (wave 8), and then further waves in the second halves of May and June. About 1,000 respondents participated in wave 1, and about 2,000 from wave 2 to wave 10 (June 2020). For Austria, data are from the Austrian Corona Panel Project (ACPP; Kittel et al. Citation2020a), an online panel survey in which around 1,500 panellists participated first in weekly waves from March 27, 2020 until June 3, 2020 (Wave 1 until Wave 10), and then in bi-weekly waves until July 15, 2020 (Wave 11 till Wave 13).Footnote 4 Both panel data collection efforts were implemented independently in the two countries at the time when the respective government announced its various lockdown measures, or shortly after, and ran throughout the following stages of the crisis when lockdown measures were being lifted. The design of the two longitudinal studies is very similar, and they are, thus, ideally suited to test our hypotheses on the ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect both cross-sectionally and longitudinally.Footnote 5

With regards to our dependent variable, ‘trust in government’, both datasets include measures asked on a (almost) weekly basis. Respondents in Austria were asked: ‘Do you have much, some, little or no trust in each of the institutions mentioned in the context of the Corona crisis?’, including in the list of institutions amongst others also ‘The Federal Government’. Answers were given on an 11-point scale, ranging from 0 ‘No trust at all’ to 10 ‘Much trust’. Participants in the French panel were asked ‘How much [they] trust the Government’, as part of a battery about trust in a number of institutions or groups. They answered using a four-point scale, with categories ‘Trust completely’, ‘Trust somewhat’, ‘Don’t trust a lot’, and ‘Don’t trust at all’.Footnote 6 For both countries, we recode answers to the 0–1 range.Footnote 7

Questions on perceived health and economic threats posed by the pandemic to society at large were asked in slightly different ways in the two studies. In Austria, the corresponding questions were ‘How great do you estimate the health [economic] risk posed by the coronavirus to the Austrian population?’. In France, respondents were asked ‘Would you say that the consequences of the coronavirus epidemic for health [the economy] in France are today…?’. In both countries responses were given on a five-point scale (‘very large’, ‘large’, ‘average’, ‘small’, ‘very small’ in Austria; ‘very serious’, ‘quite serious’, ‘somewhat serious’, ‘not serious’, ‘not at all serious’ in France). For the present analyses, all of these variables were recoded to the 0–1 range, with higher values indicating perceptions of a more acute threat.

The appropriateness of the government’s COVID-19 measures was also assessed. In France, respondents were invited to evaluate ‘the measures taken by the President and its government’ to protect ‘the health of the French’. Answers to this question were recorded on a five-point scale (with categories ‘Really exaggerated’, ‘Somewhat exaggerated’, ‘Neither inadequate, nor exaggerated’, ‘Somewhat inadequate’, and ‘Very inadequate’). In Austria, there was one question on that topic, asking ‘Do you consider the reaction of the Austrian Government in view of the outbreak of coronavirus to be insufficient, appropriate or too extreme?’ with response options on a 5-point scale (ranging from ‘not sufficient at all’ to ‘too extreme’). As non-linear effects are to be expected in this, with citizens being more sceptical of the government when it does too little or too much, we recode the responses into three categories (‘not enough’, ‘appropriate’, ‘too extreme’), and insert them using dummy variables into our models.

Party preferences are assessed by a measure of vote choice. In the case of France, this is a prospective measure (‘If the first round of parliamentary elections took place next Sunday…’), whereas in Austria we rely on the reported voting behaviour in the last parliamentary election that was held on September 29, 2019 as a substitute. We differentiate between three categories of respondents: supporters of government parties, of opposition parties, and a residual category of those that do not report to support either of them (i.e. who say they would or did not vote, cast a blank or invalid vote or refused to answer). In Austria, government supporters are those who voted for the Christian-Democratic ÖVP or the Green Party, while opposition supporters voted for the Social-Democratic SPÖ, the right-wing populist FPÖ, the liberal NEOS, or other minor parties. In France, supporters of the incumbent government reported intending to vote for La République en Marche (LREM) or its ally, the Mouvement Démocrate (MoDem). Respondents who intend to vote for any other of the French parties (including among others the conservative Republicans, the Social-Democratic Socialists, and the far-right party, Rassemblement National), we group together as supporters of the opposition. We also include gender, age and education as controls in our cross-sectional analysis.

Our strategy of analysis is three-fold. First, we start with some descriptive statistics to show how the main variables – trust in government, health and economic threats perceptions as well as perceptions of government measures – evolved over time in the two countries. The data will be weighted by demographic weights to ensure that the sample composition closely matches population targets at every point in time. The purpose of this analysis is to provide relevant background information on the two countries and to inspect the overall trends at the aggregate-level.

Second, we evaluate differences across groups of respondents cross-sectionally. We use data from the first wave in Austria and the second wave in France as they were conducted almost at the same time during the critical phase of rising infection numbers and the economy coming to a standstill, namely at the end of March 2020 (see also Online Appendix A). Using OLS regression, we start out by estimating some baseline models, including stagewise first our sociodemographic control variables and then party preferences (for the results of the baseline models, see Models 1 and 2 in Table C1 and C2 in Online Appendix C). Then follows the cross-sectional tests of Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3, by adding the perceived threat to public health and the economy to the model, along with the measure of the appropriateness of the government’s COVID-19 measures and interactions with party preferences.

In the third part of our analysis, we make use of the panel structure of our data using fixed-effect panel regressions (Brüderl and Ludwig Citation2015), studying whether and why the levels of trust tend to decline over time. To assess Hypothesis 4, whether it is in particular supporters of opposition parties reverting to their critical stance towards the government, we first estimate a model including a time trend for each group. We then include again the key independent variables – perceived threats (health and economy) and perceived appropriateness of the measures – in conjunction with partisan preferences. To ensure temporal ordering of the dependent and independent variables and avoid simultaneity problems, we lag the independent variables by one interval (lag-1) in this analysis. This analysis offers a test of the longitudinal impact of our Hypotheses 1 to 3.

We estimate separate regression models for Austria and France.Footnote 8 To evaluate the observable implications of our hypotheses, we inspect the relevant plots of predicted values and marginal effects. This is in line with the recommendations of the literature on interpreting models including interactions (Brambor et al. Citation2006; Franzese and Kam Citation2009) and facilitates a straightforward interpretation of the results. The full estimation tables for all models are included in Online Appendix C.

The COVID-19 crisis in Austria and France

We focus in our analysis on two countries, Austria and France, who approached the COVID-19 crisis rather similarly with regards to the lockdown and the later lifting of measures. France declared a lockdown on March 17, 2020, while the Austrian government announced on March 13, 2020 that a lockdown was set to start on March 16, 2020. Immediately, after the announcement of the lockdown, a broad national reaction across all ideological camps followed in Austria: all political parties represented in the Austrian parliament announced their support of this government decision. The newly formed coalition government between the Christian-Democratic ÖVP and the Greens could thus rely on a broad consensus amongst all parties when introducing their various measures, both with regard to health and economic policies. Meanwhile, in France opposition parties did not unanimously support the government’s emergency laws, neither during the first lockdown nor afterwards. For instance, left-wing Members of Parliament (Les Echos Citation2020) either voted against the emergency law introduced in the wake of the first lockdown or abstained. These differences may be based in the set-up of the political system and the government composition of the two countries. While based on their constitutions both countries can qualify as semi-presidential systems, Austria, in practice, operates like a classical parliamentary system (Duverger Citation1980; Müller Citation1999) with coalition governments being able to rely on a comfortable majority in the parliament. Instead France has often been considered as the supposed primordial case of a semi-presidential system with a strong president and a less powerful government in comparison (Duverger Citation1980; but see Elgie Citation2009). While Austria is commonly characterised as a consensual political system with a proportional electoral system, coalition governments, and government and opposition parties working together at different levels (e.g. in the social partnerships, at the regional levels, etc.), France with its majoritarian electoral institutions had been a classical example of left–right bi-polarisation for decades until the rise of the far-right resulted into a tripartite structure of opposition (Bornschier and Lachat Citation2009; Sauger Citation2009).

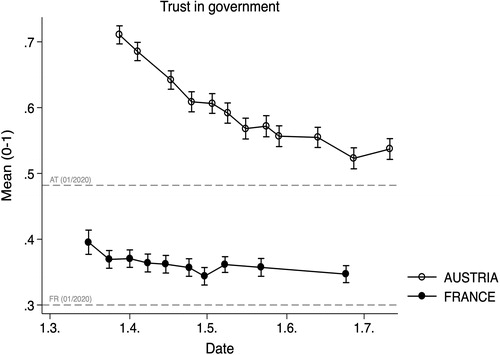

Another stark contrast between the two countries is evident when considering the distribution of our dependent variable, trust in government, and how it changed over time. presents the average levels of trust in each panel wave, as well as a baseline value, taken from separate surveys conducted in January of the same year. On the 0–1 scale, the pre-crisis level of trust in government was substantially higher in Austria (just below 0.5) than in France (about 0.3). While the level of trust was higher in both countries after the first confinement measures, this surge was clearly more pronounced in Austria, reaching an impressive value of 0.7 in the first wave of the Austrian panel. However, this very high value in Austria in late March then declined steadily over the next three months, while the corresponding attitudes among respondents in France did not vary much over time. This also means that at the end of our period of observation the gap between the two countries is again similar to the pre-crisis level. Whereas the pattern in Austria is consistent with the notion of a ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect, in France, we see much less change in average trust over time.

Figure 1. Dynamics of trust in government in Austria and France during the COVID-19 crisis.

Note: Data for Austria are from the Austrian Corona Panel Project (ACPP), for France from the dataset on ‘Citizens’ Attitudes Under the COVID-19 Pandemic’. Reference values for January (grey dashed lines) come from the AUTNES Online Panel Study 2017–2019 (Aichholzer et al. Citation2020), wave 13 (10.–24.1.2020), and the Baromètre de la Confiance Politique (28.1.–4.2.2020). For further details on the two panel surveys and question wording, see Online Appendix A and B.

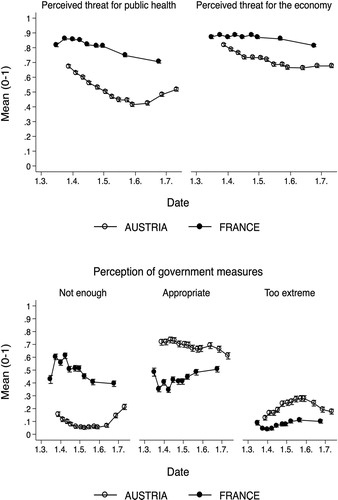

Moving to the perceived threats posed by the pandemic, shows that French and Austrian citizens perceived its consequences for health rather differently. French respondents assessed its consequences as being serious or very serious throughout March and April (average values above 0.8), with a small decline in the last two waves, reaching an average value of 0.7 in late June. In contrast, Austrian citizens, while certainly being concerned about the health threat particularly at the beginning of the lockdown, showed lower health threat perceptions and on average they also became less concerned over time. The results in largely meet face validity. While a number of factors might be responsible for this result, the differences we observe are at least consistent with the differences in the rate of COVID-19 related deaths and infections in the two countries (see Online Appendix A). While Austria could contain both overall infection rates and death tolls relatively fast and did not experience problems in its health system capacities, France, in contrast, faced problems on all these dimensions resulting even in COVID-19 patients to be transferred to German or Austrian hospitals (Busse et al. Citation2020).

Figure 2. Perceptions of threats and government measures in Austria and France during the COVID-19 crisis.

With regards to respondents’ economic threat perceptions, we see from the upper right panel in that citizens in both countries throughout our period of observation considered the economy to be endangered by the COVID-19 pandemic. While the French citizens expect the economic consequences to be very serious throughout the period of observation, Austrian citizens become slightly less fearful over time, though the average perceived threat remains well above 0.5. Overall, in both countries, the perceived economic threats are on average deemed to be more serious than the health-related threats.Footnote 9

Lastly, perceptions of the appropriateness of government measures vary substantially both between and within the two countries. A large majority of Austrian citizens consider the measures adopted by their government to address the COVID-19 crisis as appropriate. While this proportion declines slightly over time, it remains at a very high level throughout the period of observation: above 70 per cent until early May, and above 60 per cent in all later waves. In contrast, French citizens expressed less satisfaction in the evaluation of their government’s handling of the crisis. Throughout the lockdown period (from March 17 to May 11), the modal answer was that the government’s measures were not sufficient – a proportion that reached 60 per cent in late March and early April. It is only in later waves of the panel that we can observe a slight decrease in the number of French respondents that are critical of their government’s response.

Results

Cross-sectional analysis: who trusts the government in times of crisis?

In the following, we look at the results of our cross-sectional regression analysis run on data collected in both countries at the end of March 2020. We start by estimating the impact of the perceived health and economic threats posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as of the evaluation of the government’s response, to assess the group differences derived from our first three hypotheses.

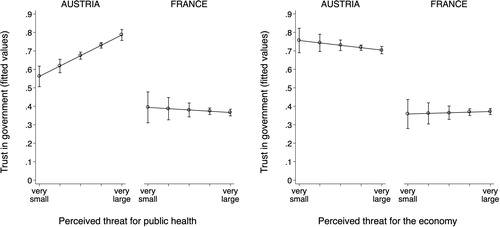

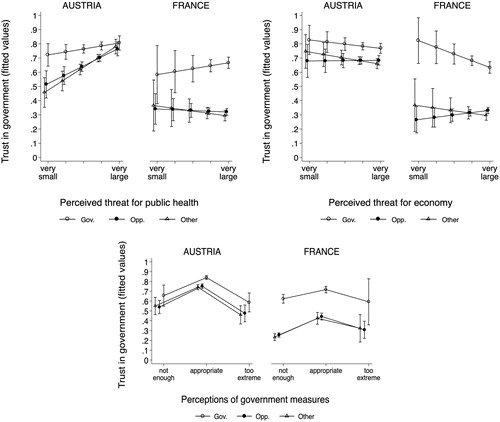

reveals that health threat perceptions are significantly and positively related to trust in government in Austria, while there seems to be no significant association in France. Higher economic threat perceptions, in contrast, are not associated with government trust at all at the beginning of the pandemic. The right-hand panel of may suggest a slightly negative relation in Austria and a slightly positive one in France, but neither of these associations are significant.

Figure 3. Trust in government and threat perceptions during the COVID-19 crisis (cross-sectional analysis).

Note: Fitted values from a model with socio-demographic variables, party preferences, threat perceptions, and evaluations of government measures (Model 3, Table C1 and C2 in Online Appendix C). Data for Austria come from wave 1 (27.–30.3.2020) and for France from wave 2 (24.–25.3.2020).

The results in Austria are in line with the first two hypotheses. First, in line with Hypothesis 1 derived from the notion of a ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect, at the beginning of a crisis, citizens who perceive larger health threats from the pandemic do express higher trust in government. Second, as expected by Hypothesis 2, the corresponding association with economic threats is weaker; in fact, it is essentially zero. While these results in Austria are in line with the first two hypotheses, these hypotheses find no support in France, where there is little evidence of a ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect. We saw earlier that the initial increase in government support has been very limited (), especially compared to Austria. We now further observe that the level of government trust among French citizens is not systematically related to the perceived threats of the crisis, neither for health nor for the economy. In line with Hypothesis 3, however, we find in both countries a systematic relation between the evaluation of the government measures and the degree of trust in government (), with citizens regarding the measures to be appropriate displaying the highest level of trust in both countries.

Figure 4. Trust in government and perceptions of government measures during the COVID-19 crisis (cross-sectional analysis).

Note: Fitted values from a model including socio-demographic variables, party preferences, threat perceptions, and perceptions of government measures (Model 3, Table C1 and C2 in Online Appendix C). Data for Austria come from wave 1 (27.–30.3.2020) and for France from wave 2 (24.–25.3.2020).

In another cross-sectional model, we interact threat perceptions and evaluations of government measures with party preferences. The results offer again distinct patterns in Austria and France; but they offer additional evidence in line with a ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect in Austria. Starting with the latter country, we see in the left-hand panel of that the different partisan groups become more similar to one another as they perceive greater health threats. Among those who consider the health-related threat of the pandemic to be very severe, trust in government is high, regardless of their party preferences. If these threats are perceived at a lower level, in contrast, trust in government is more strongly structured by partisanship. This is entirely consistent with the expectation of a rally effect.

Figure 5. Interactions with party preference (cross-sectional analysis).

Note: Fitted values from a model including socio-demographic variables, party preferences, threat perceptions, perceptions of government measures, and interactions with party preference (Model 4, Table C1 and C2 in Online Appendix C). Data for Austria come from wave 1 (27.–30.3.2020) and for France from wave 2 (24.–25.3.2020).

In contrast, in France, we cannot observe such a pattern. We see a clear difference between government supporters and opposition supporters, with the former expressing a much higher level of trust when they consider the health threats of the pandemic to be very severe, while the opposite is true for supporters of opposition parties. The differences between partisan groups are less clear at lower levels of threats perceptions, given that we have fewer such respondents. However, by all accounts, the partisan structuring of government trust is much stronger in France than in Austria even when considering perceptions of health threats caused by COVID-19.

The patterns are somewhat different for the economic threat perceptions. In Austria, government trust across levels of perceived economic threat does not differ significantly between partisan groups. In France, the direction and intensity of these associations seems to vary somewhat between these groups – though the uncertainty surrounding these estimates is relatively large. The results suggest that government party supporters are more likely to display less trust in their government if they perceive economic threats to be high, similar to a pattern of economic accountability. Other partisan groups, in contrast, always express low trust in the government. In any case, these results show that the association with partisanship is much stronger in France than that with threat perceptions, whereas the effect of partisanship is weak or absent in Austria, in line with the expectations of a rally effect.

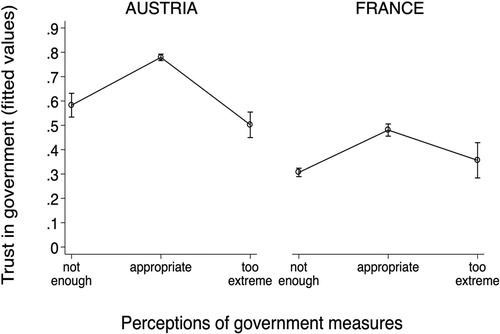

This pattern also appears clearly with respect to the evaluation of the government’s measures (, lower panel). In both France and Austria, citizens who deem these measures to be either too extreme or not sufficient express lower trust in their national government than those who consider them to be appropriate, regardless of their party preference. In France, however, we see a much larger gap in trust between government and opposition supporters, suggesting that partisanship strongly shaped trust in the government.

Panel analysis: why does trust in government decline over time?

Next, we focus on individual-level changes. While the previous analyses studied government trust by comparing groups of respondents, we now focus on intra-individual changes over time. We estimate a series of fixed-effect panel regression models to study the effects of threat perceptions, evaluations of government measures, and party preferences (for all estimation tables, see Tables C3 and C4 in Online Appendix C).

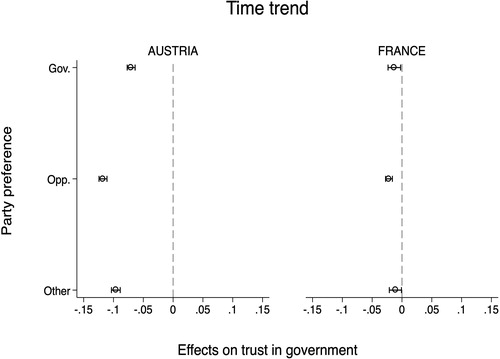

First, we focus on the time path of trust in government among different partisan groups to evaluate Hypothesis 4. As already hinted at by the descriptive statistics, trust in government declined significantly over time in Austria for all party supporters (). But most importantly, in line with Hypothesis 4, we now also observe that this decline is significantly larger for opposition party supporters than for government supporters. This supports another aspect of the expected ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect in Austria: not only did it lead to higher government trust, it also reduced partisan gap. With time passing, however, citizens tend to return to their ‘normal’ level of government trust, and the association with party predispositions becomes again stronger. In France, we can also observe a significant decline in government trust, in all three partisan groups. But the decrease is much smaller than in Austria, which is not surprising given that trust in the French government was rather low to start with, and a comparable strong ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect was never observable in the French case.

Figure 6. The effect of time on trust in government (panel analysis).

Note: Estimates are marginal effects for time trend (1 unit = 8 weeks) from a linear fixed-effects panel model (Model 1, Table C3 and C4 in Online Appendix C).

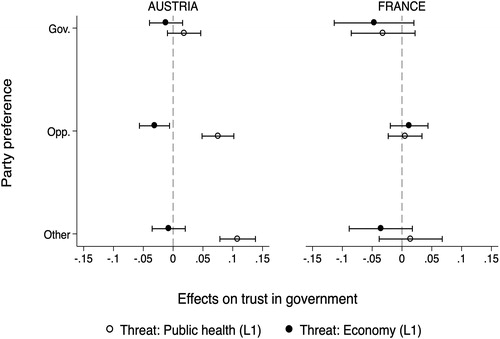

Second, we are taking health and economic threat perceptions into account. Again, we find patterns in line with a rally effect in Austria while in France changes in perceived threats does not affect trust in government over time (), corroborating our cross-sectional findings. In Austria, we observe that changes in health threat perceptions are associated with changes in government trust, providing evidence for the longitudinal observable implications of Hypothesis 1. We also see that this effect is conditional on partisanship. Among government supporters, the effect of changes in health threat perceptions is clearly smaller than in the other partisan groups. In other words, as the perceived threat on health decreases, opposition party supporters see a stronger decline in their level of government trust, in line with the expected patterns of Hypothesis 4. Again, this is consistent with a pattern of a declining ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect in Austria, and with the absence of such an effect in France. Furthermore, we find again that this decline in Austria was related only to health threat perceptions, not to economic ones. The latter do not appear to be associated with government trust – with the exception of opposition party supporters in Austria trusting the government less when levels of economic threat increase, but this effect is substantively rather small. While this difference in the effects of both types of threat is in line with the longitudinal considerations of Hypothesis 2, it basically shows that changes in the respondents’ perception of the pandemic’s economic impact in both countries did not modify their level of government trust.

Figure 7. The effects of perceived threats for public health and the economy on trust in government (panel analysis).

Note: Estimates are marginal effects for perceived threats (range: 0–1) from a linear fixed-effects panel model (Model 2, Table C3 and C4 in Online Appendix C).

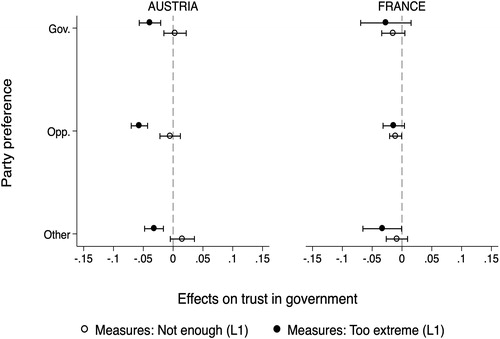

Finally, we assess the role of perceptions of the government’s measures (). Again, we do not find any significant effects for France: regardless of whether government actions become considered too extreme or not sufficient, trust in government does not change significantly over time. For Austria the story is different. There, trust in government decreases significantly more strongly when respondents change their appraisal of how the crisis is handled from appropriate to too extreme. This is true across all partisan groups. Thus, Hypothesis 3 considered from a longitudinal perspective gets partially supported in the case of Austria. Taken together, the findings suggest that the ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect fades away not only once the health threat perception decreases but also when the government measures become increasingly considered as too extreme. These results show that government trust in times of crisis is affected by complementary factors – perceptions of threats and government measures –, which are not mutually exclusive from each other, but jointly seem to shape the dynamics of public opinion.Footnote 10

Figure 8. The effect of the perceptions of government measures on trust in government (panel analysis).

Note: Estimates are marginal effects for perceptions of government measures (dummy 0/1) from a linear fixed-effects panel model (Model 2, Table C3 and C4 in Online Appendix C).

Discussion and conclusion

The aim of this article was to contribute to our understanding of public opinion during the COVID-19 crisis by using panel data from two countries – Austria and France – collected since the beginning of the crisis. The findings from this article show that the COVID-19 crisis provoked a substantial rally effect, at least in one of the two countries that we examine, namely Austria. High levels of government trust in Austria were closely tied to health threat perceptions cross-sectionally and over the course of the crisis, with supporters of the opposition parties quickly reverting to a more critical view of the government as time went on. Yet, while health threats were associated with trust in government, this was less the case for economic threat perceptions, possibly due to the conflicting motives between economic threat perceptions and accountability mechanisms as outlined in the theory section. Perceptions of the appropriateness of the government’s response mattered, too. While they played a rather minor role in bridging the trust gap between government and opposition supporters, they contributed significantly to the dynamics of trust over time affecting government and opposition supporters about equally. Taken together, the results for Austria suggest that trust in government was jointly influenced both by the health threat directly caused by the crisis (Schraff Citation2020; Esaiasson Citation2020) and by performance evaluations of the government’s policies (Bol et al. Citation2021). The French case shows that an international health crisis does, however, not automatically provoke a ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect. While in Austria both supporters of government and opposition parties feature high trust in government, a sharp divide between the two groups of party supporters can be observed in France. It seems that initially low levels of trust in government and high levels of partisan polarisation have reduced the chances that citizens rally behind its government.

We can speculate about possible reasons responsible for the contrast in the two countries. As outlined, Austria and France differed quite substantially in how the national political actors approached the crisis. Opposition parties in Austria initially supported the government, with most laws passed with unanimity in the early stage of the crisis, whereas public discourse in France was marked by controversial debates from the beginning. Also, the government support started from different baselines, most likely given by the differing electoral cycles in the two countries. While in France the government has been in place since 2017, in Austria the ÖVP-Green coalition government was inaugurated just two months (January 7, 2020) before the lockdown was imposed on the Austrian population. In line with these notions, the political baseline from which the two countries had to face and manage the initial phases of the COVID-19 crisis differs quite substantially which seems to have had implications on government trust. However, future research needs to look more closely into factors at the country level, and their effects on crisis perception and government trust; comparative research can indeed help to identify the condition under which threat might give rise to a ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect.

We believe that we contribute in at least two important ways to our understanding of public opinion. First, most of the existing literature on the ‘rally-round-the-flag’ phenomenon has focussed on international crises posited by terrorist attacks (Albertson and Gadarian Citation2015; Balcells and Torrats-Espinosa Citation2018). As such, we still know little about the impact of other types of crises on trust in government, especially if those crises pose more than one type of threat at once within different political settings. Our findings show that in the context of the COVID-19 crisis with different types of threats arising simultaneously, perceived threats to public health shaped trust in government more strongly than economic concerns.

Second, our analyses on the temporal dynamics of the rally effect shed light on the important question of the duration of a rally effect. In other words, how long can the government rely on the strong support of its citizens? In our hypothesis focussing on developments throughout time we already hinted at the possibility that rally effects might decay differently for different groups (e.g. supporters from opposition versus government parties). Furthermore, Baum (Citation2002) has shown for the US case that contextual factors can also influence the longevity of the ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect. We suggest that the rally effect should be understood as a short-term reaction to an immediate threat that motivates supporters of the opposition to lend support to the government for a limited amount of time, with support decreasing rather quickly as soon as the immediate danger has been averted. A precondition for the rally effect to happen seems to be a sufficient level of societal consensus that does not get undermined, for example, by very high levels of partisan polarisation. Future studies should investigate these aspects further.

In practical terms, these results have implications for what to expect and how to effectively overcome a moment of crisis. First, the rally effect is transient in its very nature. Mismanagement of the crisis, of course, may add to a more rapid decline and could have possibly even further detrimental side effects. Yet, even if the government manages a crisis perfectly well, it is to be expected that the government will lose support over time due to the declining levels of perceived threat and supporters of the opposition returning to their normal critical assessment of the government. Finally, to overcome a crisis effectively, a basic level cross-partisan consensus should be maintained even in regular times, as a crisis may strike suddenly, and the effectiveness of containment policies (e.g. Kittel et al. Citation2021) may in the end depend as well on the undivided or at least strong support for the government in society at large.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.1 MB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the organisers and participants of the Citation2020 APSA Panel ‘Relevance, quality, and expedience: Political science responds to COVID-19: Comparing and explaining policy reactions and political consequences’. Special thanks to the discussant Andrea Louise Campbell for providing us with helpful comments on an earlier version of the paper. Data collection has been made possible by the COVID-19 Rapid Response Grant EI-COV20-006 of the Vienna Science and Technology Fund (WWTF) and financial support by the Rectorate of the University of Vienna. Further funding by the Austrian Social Survey (SSÖ), the Vienna Chamber of Labour (Arbeiterkammer Wien), and the Federation of Austrian Industries (Industriellenvereinigung) is gratefully acknowledged. French data collection has received financial support from ANR (French Agency for Research) – REPEAT grant (ANR-20-COVI-0079) and from French region Nouvelle Aquitaine. The data from the Austrian Corona Panel Project that support the findings of this study are openly available via AUSSDA (The Austrian Social Science Data Archive) at https://doi.org/10.11587/28KQNS. The data from France that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sylvia Kritzinger

Sylvia Kritzinger is Professor of Methods in the Social Sciences at the Department of Government, University of Vienna. She is deputy director of the Vienna Centre for Electoral Research (VieCER) and one of the project leaders of the Austrian National Election Study (AUTNES). Her research focuses on political behaviour, electoral research, democratic representation, political participation and quantitative methods. [[email protected]]

Martial Foucault

Martial Foucault is full Professor of Political Science at Sciences Po in Paris, director of the CEVIPOF (CNRS) and associate researcher within the Laboratoire Interdisciplinaire d’Evaluation des Politiques Publiques (LIEPP). His research ranges from political economy to political behaviour, with a focus on public policies, local politics and statistical methods. [[email protected]]

Romain Lachat

Romain Lachat is Associate Professor of Political Behaviour at CEVIPOF, the Centre for political research at Sciences Po, Paris. His research focuses on the comparative analysis of electoral behaviour and on political representation. He is particularly interested in the impact of political institutions and party characteristics on individual-level behaviour. [[email protected]]

Julia Partheymüller

Julia Partheymülle r works as Senior Scientist at the Vienna Centre for Electoral Research (VieCER), University of Vienna, and is a member of the project team of the Austrian National Election Study (AUTNES). Her research focuses on political behaviour, the dynamics of public opinion and the effects of political communication. [[email protected]]

Carolina Plescia

Carolina Plescia is Assistant Professor in the Department of Government at the University of Vienna. She holds a PhD from Trinity College Dublin and conducts research on topics such as public opinion, election campaigning and party politics. She currently leads an ERC Starting Grant project on the meanings of ‘voting’ for ordinary citizens, their causes and consequences. [[email protected]]

Sylvain Brouard

Sylvain Brouard is Senior Research Fellow FNSP at Sciences Po – CEVIPOF and Associate Researcher within the Laboratoire Interdisciplinaire d’Evaluation des Politiques Publiques (LIEPP). His research focuses on political attitudes and behaviour, political institutions and law making. Recent publications include articles in the American Journal of Political Science, Electoral Studies and Political Behaviour. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 Most of the literature on the ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effect explores the United States. Effects are thus studied and observed on the approval of or trust in the president and not on the government as such.

2 However, it must not be necessarily that citizens become more trusting of the government per se, rather individuals could simply increase their trust toward the relevant political actors, like in health authorities as it was the case with smallpox influenza (Albertson and Gadarian Citation2015).

3 Note that the variable trust in government can be seen as either a specific or diffuse type of support for the government (Easton Citation1965), as the term ‘government’ can refer to both the current composition of the government and the institution itself (Bol et al. Citation2021). We will come back to this issue in the empirical analysis of this paper.

4 For a detailed description of the ACPP dataset, see Kittel et al. (Citation2020b).

5 See Online Appendix A for an overview over the schedule of waves against the background of the daily numbers of new COVID-19 cases (per million inhabitants) as well as an analysis of panel retention.

6 For the question wording of the dependent and independent variables, see also Online Appendix B.

7 The datasets also include a measure of satisfaction with the current government. Empirically, we find that this measure is strongly correlated with the measure of trust in government (.78 in Austria and .76 in France), suggesting a close relationship under the given circumstances.

8 Running a pooled model with country dummies and level interactions leads to substantially identical results.

9 While this holds for each wave and country, the difference is larger in Austria (average difference of 0.20) than France (average of 0.06).

10 In a supplementary analysis (Online Appendix D), we analyse the role of time-varying effects to assess to what extent the rally effect is the result of changes in the salience of perceptions of threats and government measures in addition to changes in the mean level of these perceptions. The results show that the decline in government trust in Austria was associated not only with a decrease in levels of perceived health threat, but also with a decline in salience of these perceptions as a dimension to evaluate the government. In contrast, perceived economic threat became more salient over time, with higher levels of economic threat being associated with a decrease in government trust. Also, perceptions of the government measures being too extreme slightly gained in salience. Overall, however, both of the latter two effects were relatively small in size, suggesting that the main factor behind the decline in levels of government trust in Austria were the changes in the levels and salience of perceived health threats. For France, we see fewer dynamics in general and there is considerable uncertainty. If anything, the results suggest that the salience of perceived economic threat grew slightly over time, suggesting that the French government became increasingly punished for the economic consequences of the crisis.

References

- Aichholzer, Julian , Julia Partheymüller , Markus Wagner , Sylvia Kritzinger , Carolina Plescia , Jako-Moritz Eberl , Thoms Meyer , Nicolai Berk , Nico Büttner , Hajo Boomgaarden , and Wolfgang C. Müller (2020). AUTNES Online Panel Study 2017–2019 [Dataset], AUSSDA Dataverse, Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.11587/QDETRI (accessed 12 March 2021).

- Albertson, Bethany , and Shana Kushner Gadarian (2015). Anxious Politics: Democratic Citizenship in a Threatening World . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Anderson, Christopher J. (2007). ‘The End of Economic Voting? Contingency Dilemmas and the Limits of Democratic Accountability’, Annual Review of Political Science , 10:1, 271–96.

- Baekgaard, Martin , Julian Christensen , Jonas Krogh Madsen , and Kim Sass Mikkelsen (2020). ‘Rallying around the Flag in Times of Covid-19: Societal Lockdown and Trust in Democratic Institutions’, Journal of Behavioral Public Administration , 3:2, 1–12.

- Baker, William D. , and John R. O’Neal (2001). ‘Patriotism or Opinion Leadership? The Nature and Origins of the “Rally Round the Flag” Effect’, Journal of Conflict Resolution , 45:5, 661–87.

- Balcells, Laia , and Gerard Torrats-Espinosa (2018). ‘Using a Natural Experiment to Estimate the Electoral Consequences of Terrorist Attacks’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 115:42, 10624–9.

- Bartels, Larry M. (1999). ‘Panel Effects in the American National Election Studies’, Political Analysis , 8:1, 1–20.

- Baum, Matthew A. (2002). ‘The Constituent Foundations of the Rally-Round-the-Flag Phenomenon’, International Studies Quarterly , 46:2, 263–98.

- Bechtel, Michael M. , and Jens Hainmueller (2011). ‘How Lasting is Voter Gratitude? An Analysis of the Short- and Long-Term Electoral Returns to Beneficial Policy’, American Journal of Political Science , 55:4, 852–68.

- Bol, Damien , Marco Giani , André Blais , and Peter John Loewen (2021). ‘The Effect of COVID-19 Lockdowns on Political Support: Some Good News for Democracy?’, European Journal of Political Research , 60:2, 497–505.

- Bornschier, Simon , and Romain Lachat (2009). ‘The Evolution of the French Political Space and Party System’, West European Politics , 32:2, 360–83.

- Brambor, Thomas , William R. Clark , and Matt Golder (2006). ‘Understanding Interaction Models: Improving Empirical Analyses’, Political Analysis , 14:1, 63–82.

- Brody, Richard A. (1984). ‘International Crises: A Rallying Point for the President?’, Public Opinion , 6:6, 41–3.

- Brüderl, Josef , and Volker Ludwig (2015). ‘Fixed-Effects Panel Regression’, in Christof Wolf and Henning Best (eds.), The Sage Handbook of Regression Analysis and Causal Inference. Los Angeles: Sage, 327–57.

- Busse, Claire , Ulrike Esther Franke , Rafael Loss , Jana Puglierin , Marlene Riedel , and Pawel Zerka (2020). European Solidarity Tracker . Berlin: European Council on Foreign Relations, available at https://www.ecfr.eu/solidaritytracker (accessed 12 March 2021).

- Chanley, Virginia A. , Thomas J. Rudolph , and Wendy M. Rahn (2000). ‘The Origins and Consequences of Public Trust in Government: A Time Series Analysis’, Public Opinion Quarterly , 64:3, 239–56.

- Chowanietz, Christophe (2011). ‘Rallying around the Flag or Railing against the Government? Political Parties’ Reactions to Terrorist Acts’, Party Politics , 17:5, 673–98.

- Davis, Darren W. , and Brian D. Silver (2004). ‘Civil Liberties vs. Security: Public Opinion in the Context of the Terrorist Attacks on America’, American Journal of Political Science , 48:1, 28–46.

- Druckman, James N. , and Rose McDermott (2008). ‘Emotion and the Framing of Risky Choice’, Political Behavior , 30:3, 297–321.

- Duverger, Maurice (1980). ‘A New Political System Model: Semi-Presidential Government’, European Journal of Political Research , 8:2, 165–87.

- Easton, David (1965). A Systems Analysis of Political Life . New York: Wiley.

- Elgie, Robert (2009). ‘Duverger, Semi-Presidentialism and the Supposed French Archetype’, West European Politics , 32:2, 248–67.

- Esaiasson, Peter , Jacob Sohlberg , Marina Ghersetti , and Bengt Johansson (2020). ‘How the Coronavirus Crisis Affects Citizen Trust in Institutions and in Unknown Others: Evidence from ‘the Swedish Experiment’, European Journal of Political Research , available at https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/a32r7/ (accessed 12 March 2021).

- Evans, Geoffrey , and Kat Chzhen (2016). ‘Re-Evaluating the Valence Model of Political Choice’, Political Science Research and Methods , 4:1, 199–220.

- Frankel, Laura L. , an d Sunshine D. Hillygus (2014). ‘Looking beyond Demographics: Panel Attrition in the ANES and GSS’, Political Analysis , 22:3, 336–53.

- Franzese, Robert J. , and Cindy Kam (2009). Modeling and Interpreting Interactive Hypotheses in Regression Analysis . Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Gadarian, Shana Kushner , Sara Wallace Goodman , and Thomas B. Pepinsky (2021). ‘Partisanship, Health Behavior, and Policy Attitudes in the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic’, PLoS One , 16:4, e0249596.

- Gaines, Brian J. (2002). ‘Where’s the Rally? Approval and Trust of the President, Cabinet, Congress, and Government since September 11’, Political Science & Politics , 35:03, 531–6.

- Hetherington, Marc J. , and Michael Nelson (2003). ‘Anatomy of a Rally Effect: George W. Bush and the War on Terrorism’, Political Science and Politics , 36:01, 37–42.

- Key, V. O. (1966). The Responsible Electorate . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Kittel, Bernhard , Fabian Kalleitner , and David Schiestl (2021). ‘Avoiding a Public Health Dilemma: Social Norms and Trust Facilitate Preventive Behaviour If Individuals Perceive Low COVID-19 Health Risks’, SocArXiv , available at https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/q9b23 (accessed 12 March 2021).

- Kittel, Bernhard , Sylvia Kritzinger , Hajo Boomgaarden , Barbara Prainsack , Jakok-Moritz Eberl , Fabian Kalleitner , Noëlle S. Lebernegg , et al. (2020a). Austrian Corona Panel Project (SUF edition) [Dataset], AUSSDA Dataverse, Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.11587/28KQNS (accessed 12 March 2021).

- Kittel, Bernhard , Sylvia Kritzinger , Hajo Boomgaarden , Barbara Prainsack , Jakok-Moritz Eberl , Fabian Kalleitner , Noëlle S. Lebernegg , et al. (2020b). ‘The Austrian Corona Panel Project: Monitoring Societal Dynamics Amidst the COVID-19 Crisis’, European Political Science , available at https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-020-00294-7 (accessed 12 March 2021).

- Leininger, Arndt , and Max Schaub (2020). ‘Voting at the Dawn of a Global Pandemic’, SocArXiv , available at https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/a32r7/ (accessed 12 March 2021).

- Les Echos (2020). ‘Coronavirus: le Parlement vote l’état d’urgence sanitaire’, Paris: Les Echos, available at https://www.lesechos.fr/politique-societe/gouvernement/coronavirus-accord-trouve-sur-la-loi-instaurant-letat-durgence-sanitaire-1187694 (accessed 12 March 2021).

- Lewis-Beck, Michael S. , Richard Nadeau , and Angelo Elias (2008). ‘Economics, Party, and the Vote: Causality Issues and Panel Data’, American Journal of Political Science , 52:1, 84–95.

- Lewis-Beck, Michael S. , and Mary Stegmaier (2000). ‘Economic Determinants of Electoral Outcomes’, Annual Review of Political Science , 3:1, 183–219.

- Merkley, Eric , Aengus Bridgman , Peter J. Loewen , Taylor Owen , Derek Ruths , and Oleg Zhilin (2020). ‘A Rare Moment of Cross-Partisan Consensus: Elite and Public Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Canada’, Canadian Journal of Political Science , 53:2, 311–8.

- Mueller, John E. (1970). ‘Presidential Popularity from Truman to Johnson’, American Political Science Review , 64:1, 18–34.

- Mueller, John E. (1973). War, Presidents, and Public Opinion . New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Müller, Wolfgang C. (1999). ‘Austria’, in Robert Elgie (ed.), Semi-Presidentialism in Europe . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 22–46.

- Sauger, Nicolas (2009). ‘Party Discipline and Coalition Management in the French Parliament’, West European Politics , 32:2, 310–26.

- Schraff, Dominik (2020). ‘Political Trust during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Rally around the Flag or Lockdown Effects?’, European Journal of Political Research , available at https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12425 (accessed 22 April 2021).

- Tabri, Nassim , Samantha Hollingshead , and Michael J.A. Wohl (2020). ‘Framing COVID-19 as an Existential Threat Predicts Anxious Arousal and Prejudice Towards Chinese People’, PsyArXiv, available at: https://psyarxiv.com/mpbtr/ (accessed 12 March 2021).

- The Economist . (2020). COVID-19 Has Given Most World Leaders a Temporary Rise in Popularity , London: The Economist, available at https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2020/05/09/covid-19-has-given-most-world-leaders-a-temporary-rise-in-popularity (accessed 12 March 2021).

- Zmerli, Sonja , and Tom W. G. van der Meer (eds.). (2017). Handbook on Political Trust . Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.