Abstract

The appropriate scale of metropolitan governance has been the subject of long-running debates. These debates between institutional fragmentation and integration proponents have revolved around the efficiency and effectiveness of metropolitan governance structures. However, the democratic acceptability of such reforms – whether and which citizens support or oppose metropolitan integration – has been largely ignored. This article makes two contributions. First, it develops a socio-psychological explanation of citizens’ support for metropolitan integration. Second, it uses unique survey data of 5000 respondents from eight West European metropolitan areas to demonstrate that group-based (local attachment and nationalist party support) and cognitive factors (exposure to metropolitan issues and heuristics) are linked to metropolitan integration support, while material interests are less relevant. These findings are in line with multilevel governance research more generally and suggest that citizens’ multilevel governance perceptions exhibit similar patterns across territorial scales.

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1929688 .

In 1999, the British government decided to reform the governance structure of the London metropolitan area. It transferred local competences in the domains of public transportation, police, and housing, among others, to a newly created, metropolitan-wide institution, the Greater London Authority. This metropolitan integration reform was an attempt to ameliorate the match between the functional reality of urban life – the constant flows of goods, services and people which circulate in the city-region – and the fragmented politico-administrative structure of the metropolitan area.

Indeed, such mismatches common to many urban areas worldwide pose challenges to metropolitan governance, particularly in domains that require coordination among local jurisdictions such as spatial planning or public transport policies (Sager Citation2006). These challenges push authorities to consider different kinds of institutional reforms to integrate metropolitan governance structures: metropolitan-wide institutions like in the London case, the amalgamation of local jurisdictions through mergers, and task-specific inter-municipal cooperation (Lefèvre Citation1998; Norris Citation2016).Footnote1

In scholarly debates on how to govern metropolitan areas, such integrative reforms have been promoted as one way to ensure that governance structures produce desirable outputs in efficient and effective ways. Integration proponents have insisted that upscaling authority from local jurisdictions to metropolitan institutions allows for more efficient public service delivery and for a more equal distribution of resources across the city-region (Sager Citation2006). These proposals have been contested by fragmentation proponents. They argue that jurisdictional fragmentation is more efficient and effective to tailor governmental outputs to citizens’ needs and demands (Ostrom Citation1972).

The main justification for both metropolitan integration and fragmentation is thus of a technocratic and depoliticised nature – focussed on efficiency and effectiveness (Keating Citation2008: 68). But what about the democratic acceptability of these reforms? Ordinary citizens are directly affected by jurisdictional reforms in numerous ways – particularly at the local level. Such reforms can change their access to public services, their exercise of political control through voting, and even their membership in political communities. Therefore, ignoring citizens’ perspective on metropolitan integration processes is normatively problematic. It is widely agreed that democratically legitimate decision-making processes ought to take citizens’ views into account, especially when making fundamental decisions about jurisdictional design such as metropolitan integration.

Furthermore, mass public support for metropolitan integration is also crucial from a practical point of view. This is evident in situations, where citizens are asked to vote on metropolitan integration reforms. Providing an overview of popular votes on metropolitan integration in the USA from 1947 to 2010, Norris (Citation2016: 113–5) shows that only 32 out of 150 city-county consolidation projects succeeded at the ballot box. A lack of public support can also have adverse political consequences in cases where such reforms are implemented top-down by higher government tiers (like the Greater London Authority): if citizens’ views are not taken into account for such decisions, their support for the political system might fade on the long term (see Hansen Citation2015). Despite their normative and practical relevance, the crucial questions of whether and which citizens support metropolitan governance reforms have remained largely unanswered.

These questions are at the core of the present article. I offer two main contributions towards answering them. First, I develop an original theory of citizens’ perceptions of metropolitan integration. It goes beyond existing theories that have focussed on citizens’ material interests (Edwards and Bohland Citation1991; Filer and Kenny Citation1980) by introducing socio-psychological factors highlighted in research on attitudes towards European integration and decentralisation processes (Hobolt and De Vries Citation2016; Verhaegen et al. Citation2017). I suggest that what matters is not only whether citizens themselves or their respective community might benefit from metropolitan integration but also factors such as citizens’ identification with different territorial scales, their political ideology, the knowledge they have about metropolitan governance and the heuristics they employ when evaluating metropolitan integration reforms. Such group-based and cognitive factors are currently absent from studies on mass public opinion towards metropolitan governance.

Second, I offer the first cross-national analysis of citizens’ metropolitan integration perceptions by testing this theory with data from a unique online survey conducted in fall 2015 with 5000 respondents from eight metropolitan areas in France, Germany, Switzerland and the UK. The results show that citizens exhibit consistent and structured perceptions of metropolitan integration. Moreover, they provide descriptive evidence that group-based factors – strong local identification and support for nationalist parties – are associated with more negative, whereas cognitive factors – exposure to metropolitan politics and trust in local government – go along with more positive perceptions of metropolitan integration. In contrast to these socio-psychological correlates, factors capturing material interests seem to matter less for citizens’ perceptions.

These findings suggest that the efficiency and effectiveness of metropolitan governance is not citizens’ primary concern. Rather, to enhance the legitimacy of metropolitan governance reforms in their eyes, reform debates should consider citizens’ social identities and authorities should provide adequate information on metropolitan governance and include citizens in the process of reforming political institutions.

Understanding citizens’ perceptions of metropolitan integration

What are the determinants of mass public support for metropolitan integration? Two kinds of dependent variables and corresponding explanations can be identified in the few existing studies: (i) metropolitan identification, explained through mobility behaviour and (ii) perceptions of metropolitan integration reforms, explained through material interests. The first group of studies does not directly focus on metropolitan integration perceptions, but on citizens’ orientations towards their city-region (Lidström Citation2018). To explain who is more or less oriented to the metropolitan scale, researchers highlight the role of citizens’ day-to-day and residential mobility behaviour (Kübler Citation2018). As an ever-larger number of people commutes across local jurisdictions for professional or leisure activities and moves regularly, their perception of the urban area as one connected space would be sharpened, so the argument goes, and lead to a rescaling of citizens’ political orientations to the metropolitan level (Lidström Citation2006). In this view, we could thus expect that citizens who are more mobile in their city-region do not only identify more with their city-region but are also more supportive of metropolitan integration reforms (see Wicki et al. Citation2019).

Second, scholars examine citizens’ perceptions of metropolitan integration reforms, like amalgamation, inter-municipal cooperation, or upscaling authority to metropolitan governments. The dominant explanation for these perceptions is the material interests of the concerned individuals (Filer and Kenny Citation1980). Egotropic explanations (‘what do I get?’) focus on citizens’ ability to exit their local jurisdiction (Tiebout Citation1956). Citizens who are bound to their place – because they own property or cannot afford to live somewhere else – cannot easily ‘vote with their feet’ and exit their jurisdiction in case metropolitan integration has adverse effects for them. Accordingly, they might be more critical of such reforms (Lyons et al. Citation1992). Sociotropic explanations (‘what does my jurisdiction get?’) focus on the expected effect of metropolitan integration for local jurisdictions. Citizens are expected to use the current situation of their place of residence as a benchmark to evaluate metropolitan integration proposals. For instance, if citizens perceive the local service quality to be good, they should be less inclined to support metropolitan integration – since they cannot gain much compared to residents in underserved jurisdictions (Bergholz and Bischoff Citation2019; Hawkins Citation1966). Similarly, residents of rather well-off, small, or peripheral jurisdictions should be more sceptical of metropolitan integration, out of fear of having to pay for metropolitan-wide policies that mostly benefit poorer jurisdictions or of being marginalised in metropolitan decision-making processes (Eklund Citation2018; Kübler Citation2018).

These accounts have largely ignored socio-psychological factors as a source of variation in citizens’ metropolitan integration perceptions – despite their pivotal relevance for citizens’ evaluation of political processes and outcomes (Zaller Citation1992). In the next section, I develop such a socio-psychological perspective for metropolitan integration perceptions.

Socio-psychological correlates of metropolitan integration perceptions

A socio-psychological perspective on metropolitan integration requires to consider social identities and cognitive processes: in addition to asking what we get from metropolitan integration, we have to ask what metropolitan integration means for us, how familiar we are with metropolitan issues, and how cognitive shortcuts shape the way we think about these issues.

Scholars assessing perceptions towards the reallocation of decision-making authority in other contexts – such as European integration or state decentralisation – have shown that the answers to these questions matter a great deal for citizens’ perceptions (Henderson et al. Citation2014; Hobolt and De Vries Citation2016; Hooghe and Marks Citation2005). These socio-psychological explanations can be further divided into two groups: group-based factors and cognitive factors. In what follows, I discuss the respective theoretical concepts, highlight their relevance for metropolitan integration, and formulate five hypotheses.

Group-based factors

Group-based explanations state that citizens’ multilevel governance preferences depend on their territorial and functional identities. Multilevel governance reforms not only create material winners and losers, but also mobilise social identities. Social identities allow individuals to feel close to some but also to demarcate themselves from other individuals. These demarcations can be made based on territorial criteria, such as living in a certain place, or based on functional criteria like ethnicity or political ideology. Whether someone supports or opposes a particular multilevel governance reform then depends on whether a person’s identity is compatible with it or not (Ejrnaes and Jensen Citation2019).

Scholars have demonstrated a strong positive correlation between citizens’ identification with Europe or their region, respectively, and their support for European integration or decentralisation (Fuchs et al. Citation2009; Henderson et al. Citation2014). Arguably, these persons endorse such reforms because political authority is transferred to the territorial scale they care a lot about. In reverse, scholars also show that strong national identification is negatively associated with support for European integration (Hooghe and Marks Citation2005). This is only the case, however, when citizens identify with their country and do not at the same time identify with Europe. Citizens holding such exclusive national identities perceive European integration as a threat to national sovereignty and self-determination and are thus hostile towards this process.

The relationship between citizens’ territorial identities and their preferred scale of governance can also be applied to metropolitan integration. Citizens who identify more strongly with their local jurisdiction than with their urban area might also be more sceptical of metropolitan integration: the reference point of their territorial identity, their local jurisdiction, would lose significance because it loses decision-making authority. We can thus expect that:

H1: The more exclusive citizens’ local attachment, the less they support metropolitan integration.

Functional identities can also matter for multilevel governance reforms. In particular, negative perceptions of ethnic minorities and foreigners, as well as support for nationalist parties are found to be strongly linked with Euroscepticism, because European integration challenges these identities. Scholars have found that hostile orientations towards out-groups are linked to lower levels of support for European integration and internationalisation, because xenophobic citizens fear that integration leads to a higher presence of out-groups in their country and furthers societal diversity to which they are opposed (De Vreese and Boomgaarden Citation2005; Ejrnaes and Jensen Citation2019).

In the metropolitan context, similar mechanisms might be at play. Contemporary metropolitan areas are socially diverse, but socio-economically, ethnically and politically segregated spaces (Sellers et al. Citation2013). Metropolitan integration would increase diversity in the political sphere by increasing exchanges among such segregated jurisdictions to which xenophobic persons might be opposed.

H2: Negative out-group sentiments are associated with more scepticism towards metropolitan integration.

Supporting nationalist parties is another important factor for understanding opposition towards European integration. Existing research has shown that an emerging cleavage between demarcation and integration structures post-industrial countries (Helbling and Jungkunz Citation2020). This cleavage is mobilised by traditionalist/authoritarian/nationalist (TAN) parties on the demarcationist end and by green/alternative/libertarian (GAL) parties on the integrationist end (Hooghe et al. Citation2002). TAN parties strongly oppose international integration processes and act as fervent defenders of their country’s sovereignty and self-determination, whereas GAL parties endorse international integration processes. This cleavage extends beyond the question of internationalisation. As Heinisch and Marent (Citation2018) show, TAN parties also criticise the centralisation of decision-making authority from the regional to the national, or from the local to the regional level. Moreover, Strebel (Citation2019) shows that higher TAN party vote shares in Swiss municipalities correlate with higher rejection probabilities of municipal merger proposals at the ballots. This suggests that nationalist party voters are eager to keep political control ‘close’ to them and are thus sceptical of any upscaling of decision-making authority.

H3a: TAN party supporters are more sceptical of metropolitan integration than non-partisans.

To date, there is no similar research on GAL parties’ multilevel governance positions. However, based on their positive orientation towards international integration and cooperation, we can expect their voters to take the counter position to nationalist party supporters and to be supportive of metropolitan integration.

H3b: GAL party supporters are less sceptical of metropolitan integration than non-partisans.

Cognitive factors

Until here we have assumed that citizens have a clear understanding of multilevel governance reforms. Cognitive explanations start out from the observation that most citizens do not know too much about multilevel governance (Hobolt and De Vries Citation2016). Scholars have studied (i) what difference knowledge makes for multilevel governance perceptions and (ii) what heuristics and cues citizens resort to in the absence of knowledge.

The first group of studies postulates that limited knowledge and information increases the tendency to perceive integration processes as a threat. Higher exposure to multilevel governance processes should thus go along with higher support for them. Inglehart (Citation1970) provides evidence for this link. He shows that ‘cognitive mobilisation’ – operationalised through news consumption – correlates with more favourable attitudes towards European integration in Western Europe. For the regional level, Verhaegen et al. (Citation2017) find no significant correlation between factual knowledge about regional competences and decentralisation attitudes in Belgium, however. Finally, Walter-Rogg (Citation2018) shows that German citizens with more knowledge about city-regional politics also tend to be more attached to their metropolitan area. Building on this latter finding, I assume that increased exposure to metropolitan politics increases knowledge of metropolitan issues and, consequently, support for metropolitan integration.

H4: The more citizens follow metropolitan politics, the more they support metropolitan integration.

The second group of studies analyzes the criteria based on which citizens evaluate multilevel governance in the absence of knowledge and information. The basic idea is that citizens resort to heuristics and cues when they do not have informed opinions. In an influential article, Anderson (Citation1998) argues that citizens use their perceptions of national governments as a proxy for their evaluation of European integration when they lack other information. When citizens perceive their national government to be trustworthy, and their national government engages in European integration, their support extrapolates to this process as well. This extrapolation mechanism has been tested and is well-established in numerous studies on European integration (Ejrnaes and Jensen Citation2019; Harteveld et al. Citation2013). We can make an analogous argument for metropolitan integration. If citizens lack information on such reforms, they have to rely on heuristics. An appropriate heuristic in this context is citizens’ evaluation of their local government. When citizens trust their local governments and representatives, they might as well trust them to find good solutions to metropolitan governance problems together with other local jurisdictions.

H5: The more citizens believe the local political system is working well, the more they support metropolitan integration.

Research design

Data

The five hypotheses formulated above are tested with data from a unique online survey administered on 5052 residents of eight metropolitan areasFootnote2 in France, Germany, Switzerland and the UK (NCCR Democracy Citation2016, details on the sampling procedure in Online Appendix A). These data allow for the first systematic cross-national examination of citizens’ metropolitan governance perceptions.

In particular, the selected metropolitan areas allow one to assess whether citizens’ metropolitan integration perceptions systematically differ depending on the metropolitan context. The selected metropolitan areas vary on two important features (see ). The first one is their role in the national political system, i.e. whether metropolitan areas are the capital city-region or not. Because governments and administrations from different levels are located in capital regions, citizens are more exposed to the multilevel structure of the state and might thus be more favourable to metropolitan integration. In contrast, residents in more peripheral areas might perceive some national government actions as an encroachment on their regional autonomy and hence reject attempts to centralise decision-making authority also on the regional level. This relates to the group-based explanations and inclusive versus exclusive identities (Fitjar Citation2010). The second important feature is metropolitan areas’ existing governance structures, i.e. whether they already have multi-purpose governance institutions that qualify as metropolitan governments or not (Lefèvre Citation1998). Citizens’ metropolitan integration perceptions might indeed covary with the presence or absence of metropolitan institutions. Familiarity with such institutions might be associated with lower scepticism towards metropolitan integration. This would be in line with the argument that cognitive exposure increases support for metropolitan integration. In contrast, citizens living under metropolitan governments could also be less favourable towards further metropolitan integration. Metropolitan governments are designed to address governance problems in city-regions and hence the problem pressure for reform might be smaller in areas with such multi-purpose institutions. Consequently, citizens in these areas might perceive further metropolitan integration to be unnecessary.

Table 1. Case selection and data.

Measuring support for metropolitan integration

In order to measure support for metropolitan integration, I rely on a question that asked respondents to indicate their support for the three kinds of metropolitan integration reforms mentioned in the introduction: amalgamation, inter-municipal cooperation and the creation of multi-purpose metropolitan governments.Footnote3

Do citizens across metropolitan areas have a shared and structured understanding of metropolitan integration? To assess this, I test whether the three items measure the same latent concept (support for metropolitan integration) and whether we find this latent concept in all eight metropolitan areas. For this purpose, I rely on confirmatory factor analysis (Davidov et al. Citation2014). Confirmatory factor analysis allows for testing of whether a set of items represents a postulated concept and whether this concept travels across different contexts. This requires that the observed items load on the same latent factors across contexts. Substantively, this ‘means that the latent concepts can be meaningfully discussed in all countries’, or here metropolitan areas, and that the configuration of the item-factor structure is equivalent across contexts (63).

displays the results of confirmatory factor analyses for both the overall sample and the eight metropolitan areas separately.Footnote4 The factor loadings of the three items suggest that they indeed constitute one latent factor both in the full sample and in the eight metropolitan subsamples. The goodness-of-fit statistics in the bottom half of indicate very good model fit. All three measures clearly meet the required thresholds (RMSEA < .08, CFI and TLI ≥ .95 according to Schreiber et al. Citation2006).

Table 2. Confirmatory factor analysis: support for metropolitan integration.

The three items thus constitute a robust latent factor in the overall sample and in the eight metropolitan subsamples and we have established configural equivalence. While the items best representing the latent factor ‘support for metropolitan integration’ differ across metropolitan areas, we cannot attribute this variation meaningfully to cross-metropolitan variation in metropolitan governance structures, such as the presence or absence of a metropolitan government (see ).Footnote5 Importantly, this does not mean that citizens are equally supportive of different reform types. Mean levels of support for the different types vary both within and across metropolitan areas (see Online Appendix C). Rather, the results suggest that citizens in all eight metropolitan areas perceive the three reforms to be part of the same underlying dimension and they have consistent views on it: those who support amalgamation reforms also tend to support inter-municipal cooperation or metropolitan-wide government institutions and vice versa.

Operationalisation of socio-psychological and control factors

In order to operationalise the hypotheses and the existing explanations presented above, I rely on various survey items and local context indicators.Footnote6

Citizens’ exclusive local attachment (H1) is measured through a question that asks respondents to indicate their respective level of attachment to the local and to the metropolitan level. Using the two items, I calculate respondents’ net attachment to the local level by subtracting metropolitan from local attachment. To operationalise negative out-group sentiments (H2), I follow De Vreese and Boomgaarden (Citation2005) and use respondents’ attitudes towards immigration. Citizens’ support for TAN (H3a) and GAL parties (H3b), is measured via a question on citizens’ party identification. I recode their answers into four categories: no, other, TAN and GAL party identification. The parties are coded based on data from the 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey (see Online Appendix C).

In order to capture citizens’ exposure (H4) to metropolitan politics, I cannot rely on a direct knowledge measure, since such measures were not incorporated in the survey. I thus have to rely on two more indirect measures of exposure. A first one is whether citizens use local newspapers to inform themselves about political issues or not. Newspapers that report only on local topics or that have an important local section are considered to be local news media. A second, more subjective, indicator for metropolitan exposure is citizens’ interest in the politics of other municipalities in the same area. Centre city residents were asked about their interest in the politics of the surrounding municipalities and vice versa. Thus, I approximate exposure to metropolitan politics with local media consumption and metropolitan political interest.

Finally, I use two indicators to operationalise citizens’ evaluation of the local political system (H5): trust in local government and the feeling of local external political efficacy, i.e. the belief that local politicians are responsive to the needs of citizens in their jurisdiction.

In addition to the socio-psychological factors, I also include factors examined in the few existing studies as control variables. One factor highlighted by studies on citizens’ identification with their metropolitan area is mobility. I thus include indicators for both respondents daily and residential mobility. Daily mobility is captured through respondents’ commuting behaviour. Respondents are asked how often (less than once a week, once a week, several days per week, daily) they pursue five different activities (both professional and leisure) in municipalities other than their own. I construct a commuting indicator from these items through polychoric exploratory factor analysis (see Online Appendix C). Residential mobility is captured via two indicators: the number of years citizens live in their current jurisdiction and their previous residence in another municipality of the same metropolitan area, the latter capturing their residential connection to the city-region.

The second group of control variables concerns individuals’ ego- and sociotropic material interests. Egotropic explanations focus on individuals’ ability to vote with their feet in case metropolitan integration has adverse consequences for them. Two indicators are relevant in this respect: homeownership and income. Homeowners and low-income households might indeed have more trouble to relocate, because they own property or because they cannot afford to move to another jurisdiction. This might promote scepticism towards metropolitan integration since it centralises decision-making authority and consequently decreases the ‘voice’ options of local residents. Yet, ‘voice’ is crucial for both homeowners and low-income households who lack ‘exit’ options (Lyons et al. Citation1992).

Sociotropic explanations include both individuals’ subjective evaluations of their place of residence as well as municipal-level indicators. Citizens’ satisfaction with five local services at their place of residence captures subjective sociotropic evaluations. Using exploratory factor analysis, I construct an indicator of local service satisfaction (see Online Appendix C). The municipal benchmark indicators include a jurisdiction’s economic well-being, namely its median income relative to other municipalities in the area and its local unemployment rate. Sociotropic explanations posit that dissatisfied citizens and those living in poor municipalities are more supportive of metropolitan integration, because their municipality might benefit from it. Lastly, local government size and location of a jurisdiction in the city-region (centre vs. suburb) capture the extent to which residents would lose political control because of metropolitan integration. This loss is likely higher for residents of small or suburban jurisdictions and they might accordingly be more sceptical. Finally, the analysis includes indicators for gender, age and education.

Estimation

In order to test the five hypotheses, I rely on multilevel regressions due to the hierarchical data structure. Respondents are nested in municipalities (level-2), which are themselves nested in metropolitan areas (level-3) and countries (level-4). It is plausible that respondents living in the same municipality/metropolitan area/country are more similar in their support for metropolitan integration than respondents living in different contexts. Standard ordinary least squares regression models do not take this nestedness into account, which poses a statistical and a conceptual problem (Hox Citation2010: 3). Statistically, ignoring this nestedness entails the risk of underestimating the standard errors of regression coefficients, since observations are treated as independent when they are not. Conceptually, ignoring nestedness poses the danger of atomistic fallacy, i.e. inferring from individual-level to contextual patterns. Due to the multiple levels of nestedness in the case at hand, I thus employ multilevel regression models.

One challenge for the present analysis is that we are dealing with eight metropolitan areas on level-3 and four countries on level-4. This small number of cases does not allow for incorporation of these two levels in the multilevel regression models.Footnote7 However, this problem is mitigated by the fact that the variance of metropolitan integration support on these two levels is very small. The results of random effects ANOVAs for metropolitan integration support and the three different levels as level-2 suggest that citizens only vary significantly in their attitudes towards metropolitan integration support across municipalities, but not across metropolitan areas or countries (Online Appendix D). The associated intra-class correlation amounts to 22% in the random effects ANOVA for the municipalities but is virtually zero for the two higher levels. This means that respondents living in the same metropolitan area or the same country are not more similar in their support for metropolitan integration than respondents from different metropolitan areas or countries. We can therefore rely on multilevel regressions with respondents as level-1 and municipalities as level-2. To nevertheless capture eventual cross-metropolitan variance, I include metropolitan area-fixed effects in the model.

Who supports metropolitan integration?

Above, I have presented different explanations for why citizens support or oppose metropolitan integration. In particular, I have argued that we should pay more attention to socio-psychological factors in order to better understand citizens’ support for metropolitan integration. It is important to note that the results presented here do not allow for a causal interpretation. Rather, they allow to map descriptive patterns and correlations between the theoretically motivated variables and citizens’ metropolitan integration support.

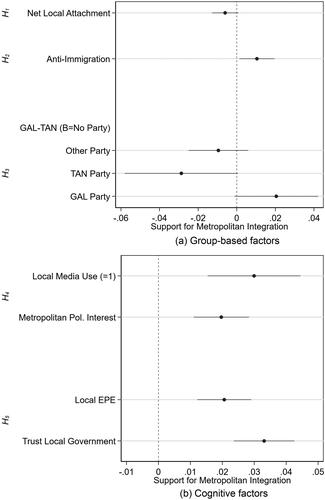

In order to ease interpretation, I rely on coefficient plots for the presentation of the results.Footnote8 displays the results for the three hypotheses on the group-based factors. In line with hypothesis H1, I find that citizens who feel more attached to the local than to the metropolitan level tend to be more critical of metropolitan integration. Ceteris paribus, the difference between the most exclusively locally and the most exclusively city-regionally attached individual amounts to 4.95 percentage points on the metropolitan integration support scale.

Figure 1. Socio-psychological variables.

Note: Dots represent regression coefficients. Lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

The second hypothesis (H2) – that negative out-group orientations are associated with higher scepticism towards metropolitan integration reforms – must be rejected. My analysis shows that xenophobia plays out counter to the expectations: compared to those most sceptical of immigration, those most favourable rank 3.2 percentage points lower on metropolitan integration support. Unlike in the European context, immigration critics thus support integration reforms in the metropolitan context. This might be the case because immigration policies and free movement of people is closely linked to European integration, whereas metropolitan integration does not have implications for immigration policies. Hence, xenophobia is not necessarily linked to integration perceptions at the subnational level. On the contrary, a strengthening of the metropolitan or the regional scale might be conceived as a way of strengthening in-group ties to fellow nationals in the same region. This could explain why the correlation is positive. However, the bivariate correlation between anti-immigration attitudes and support for metropolitan integration is weak but negative – as expected. This suggests that only a subgroup of immigration critics is positively oriented towards metropolitan integration. Given that xenophobia is closely linked to partisan identification, I examined whether the position on the GAL-TAN dimension interacts with xenophobic attitudes (see Online Appendix E.2). The positive link between xenophobia and metropolitan integration support seems to be mostly present among TAN partisans, but not among supporters of other parties – even if the associated interaction effect is not statistically significant. This suggests that the part of the TAN ideology that is not associated with xenophobia particularly drives opposition towards metropolitan integration. Xenophobic TAN partisans thus seem to be torn on the issue of metropolitan integration. On the one hand, they might see it as a way to strengthen in-group ties to fellow nationals and are hence supportive of it. On the other hand, however, they might also perceive metropolitan integration as an infringement on local sovereignty and autonomy and hence reject it. Yet, this is only a preliminary explanation and needs to be examined further in future research.

When it comes to the role of partisan identification itself for metropolitan integration support, we find support for both H3a and H3b: those who identify with TAN parties are more sceptical of metropolitan integration and those identifying with GAL parties less so. However, the confidence intervals are rather large, and the coefficients indicate moderate effects only. TAN partisans rank 2.9 percentage points lower and GAL partisans 2.6 percentage points higher on the metropolitan integration support scale than non-partisans. Still, clearly shows that TAN and GAL partisans take the two extreme positions on metropolitan integration with non-partisans and supporters of other parties ranging in between. This mirrors the situation at the European level.

contains the results for the cognitive factors (H4 and H5). H4 posits that those more exposed to or aware of metropolitan politics are more favourably oriented to metropolitan integration. Indeed, readers of local newspapers rank 3 percentage points higher on the metropolitan integration scale than those who do not read local newspapers. Moreover, citizens more interested in metropolitan politics are also more favourably oriented towards metropolitan integration. The difference on the metropolitan integration scale between the least and most interested in metropolitan politics amounts to 6.5 percentage points. Together, this is strong support for hypothesis H4.

also shows very clear evidence for hypothesis H5 – that positive sentiments towards the local political system go together with higher metropolitan integration support. Those who are most convinced that their voice is heard by local officials rank 8.5 percentage points higher on the metropolitan integration support scale than those who feel politically inefficacious. Moreover, citizens who trust their local government the most rank 13.5 percentage points higher than those with the least trust. These are rather substantial effects and yield strong support for H5. This suggests that citizens indeed use their evaluation of the local political system as a heuristic for their perception of metropolitan integration.Footnote9 Overall, this is compelling evidence that socio-psychological factors matter for our understanding of mass support towards metropolitan integration.

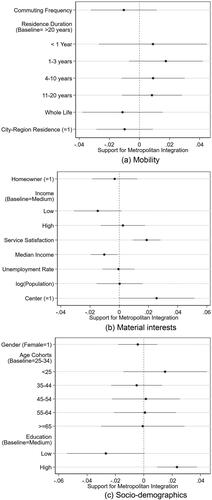

The results for the control variables suggest that mobility and material interests are less useful for understanding metropolitan integration support. Respondents’ daily and residential mobility is not significantly linked with support for metropolitan integration (). While these factors might matter for citizens’ identification with their city-region, they are not significantly correlated with citizens’ metropolitan integration support.

Figure 2. Control variables.

Note: Dots represent regression coefficients. Lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Egotropic considerations seem to matter to a limited extent (). While homeowners are not more sceptical of metropolitan integration than tenants, respondents from low-income households tend to be, in line with arguments on the role of exit and voice possibilities (Lyons et al. Citation1992). The results for sociotropic considerations, citizens using subjective and objective characteristics of their place of residence as a benchmark to evaluate metropolitan integration, are equally mixed. In line with existing explanations, respondents from more well-off and from suburban municipalities are more sceptical of metropolitan integration, yet neither the local unemployment rate nor jurisdiction size is linked to respondents’ metropolitan integration perceptions. Finally, the results show that citizens who are more satisfied with local services are more and not less likely to support metropolitan integration. This effect is substantial. The difference between the least and the most satisfied respondent amounts to 9.8 percentage points on the metropolitan integration scale. It seems that dissatisfied citizens do not perceive metropolitan integration as a way to ameliorate the local conditions in their jurisdiction. This is at odds with arguments made in many existing studies on metropolitan governance perceptions (Bergholz and Bischoff Citation2019; Hawkins Citation1966). At the same time, some scholars also report a positive correlation between service satisfaction and upscaling political authority (Mohamed Citation2008; Wicki et al. Citation2019). Yet, only Mohamed (Citation2008) provides a possible explanation for this relationship. For the case of regional governance in land-use planning, he argues that satisfied citizens want to keep things the way they are and therefore support regional land-use planning to prevent urban sprawl and deterioration. Amenable living conditions, arguably, are thus best preserved through a continuous adaptation of governance institutions.

A second possible explanation for this finding is that citizens think of the metropolitan region when evaluating local services, since task-specific service provision, e.g. public transport, often transcends municipal boundaries. When satisfied citizens are aware of this, they might support the further integration of services. An approximative test of this explanation is whether the positive link between service satisfaction and metropolitan integration support is stronger in metropolitan areas with metropolitan governments. In the latter, service provision is more integrated than in city-regions without metropolitan governments. Hence, satisfied citizens might attribute responsibility accordingly. However, the empirical analysis does not support this explanation (Online Appendix E.4).

A final possible explanation for this finding is that service satisfaction works according to the same logic as local trust and local external political efficacy. While trust in local government and external efficacy perceptions represent evaluations of the ‘input’ possibilities to political systems, service satisfaction represents an evaluation of their ‘output’. Service satisfaction might thus also serve as a positive cue from which metropolitan integration support is extrapolated. This explanation is supported by the fact that trust and efficacy perceptions exhibit medium-strong correlations with service satisfaction (Online Appendix C). Moreover, when trust and efficacy perceptions are included in the model, the coefficient of service satisfaction drops substantially, further indicating that satisfaction might capture the same mechanism as trust and efficacy. Finally, an interaction model between service satisfaction and local media use shows that the relationship between satisfaction and integration support is insignificant for more informed individuals, whereas it is very strong and positive for uninformed individuals (Online Appendix E.4). This supports the idea that uninformed individuals use their satisfaction with local services as a cue for their support of metropolitan integration.

At last, metropolitan integration support is partially linked to socio-demographic indicators as well. shows that neither gender nor age is significantly correlated with metropolitan integration support. However, more educated individuals are more supportive of metropolitan integration.

The robustness of the results presented here has been tested in three ways (Online Appendix E.5–E.8). First, the patterns also hold under alternative model specifications (multiple imputation of missing observations and municipality-fixed effects regressions). Second, the results can be replicated if we replace metropolitan integration support with the individual items amalgamation, inter-municipal cooperation and metropolitan government support. While one could expect citizens to resort to different logics when evaluating different integration reforms, the general patterns remain the same across the three integration reforms. This further corroborates the idea that citizens’ attitudes towards metropolitan integration constitute one latent dimension. Third, variations across metropolitan areas were also assessed. Metropolitan-level features (governance structures, national and global status of a city-region) do not seem to matter for citizens’ perceptions of metropolitan integration. None of the indicators is significantly or substantially linked to metropolitan integration support, suggesting that cross-metropolitan differences do not affect citizens’ metropolitan governance perceptions. Municipal-level differences in metropolitan governance structures are equally irrelevant – with two exceptions. First, residents of municipalities under the jurisdiction of a metropolitan government tend to be more supportive of metropolitan integration than residents of the same city-region living outside said jurisdiction. This is in line with the cognitive exposure idea: familiarity with metropolitan institutions seems to increase support for metropolitan integration (see earlier section on Data). Second, residents of municipalities that benefit from inter-municipal equalisation payments tend to be more in favour of metropolitan integration. This is in line with arguments on sociotropic concerns: gains from metropolitan integration increase citizens’ support for it (for a more detailed discussion, see Online Appendix E.8). Generally, citizens’ metropolitan integration perceptions do not seem to covary with the metropolitan context.

Altogether, the results presented here demonstrate the relevance of socio-psychological factors for citizens’ perceptions of metropolitan integration. Except for respondents’ out-group sentiments (H2), the results corroborate all hypotheses. Citizens with a predominantly local territorial identity (H1), sympathisers of nationalist parties (H3a), citizens less concerned with metropolitan politics (H4) and those who evaluate their local government less positively (H5) are all less supportive of metropolitan integration, whereas cosmopolitans (H3b) are more so. By contrast, factors associated with citizens’ mobility behaviour and material interests seem to be less relevant for metropolitan integration support.

Conclusion

The goal of this study was to advance our understanding of the democratic acceptability of metropolitan governance reforms by analysing citizens’ perceptions of metropolitan integration. It proposed to do so by complementing the few existing studies and looking at the relevance of socio-psychological factors – citizens’ social identities and their cognitive engagement – for understanding metropolitan integration perceptions. Using unique survey data from 5000 respondents in eight metropolitan areas, I have shown, first, that citizens hold structured and consistent opinions on metropolitan integration across a diverse set of metropolitan areas. Second, these perceptions are correlated with citizens’ territorial identities, their position on the emerging cleavage between demarcation and integration, their exposure to metropolitan politics and their evaluation of the local political system. In contrast to these group-based and cognitive factors, existing explanations focussed on citizens’ mobility behaviour in the city-region and their material interests regarding metropolitan governance yield only mixed results. The findings presented in this article hold across a diverse selection of metropolitan areas characterised by various governance structures, population sizes and roles in the national political system as well as in the global economy. This suggests that the findings might be generalisable to metropolitan areas in Western countries. Moreover, the findings are also in line with recent research on European integration and decentralisation attitudes (Ejrnaes and Jensen Citation2019; Verhaegen et al. Citation2017) and point to the existence of more fundamental patterns of citizens’ multilevel governance perceptions that hold not only across metropolitan areas but also across territorial scales.

A limitation of this study is that the external validity of the findings comes at a certain price for internal validity. To obtain a cross-nationally comparable measure of metropolitan integration support, the survey items needed to leave some local specificities aside to focus on commonalities at a more general level. This results in two limitations. First, the present study cannot make a statement about mass public preferences for specific reform types and options as opposed to others. Obtaining such information would require surveying citizens’ preferences at a moment when different reform options are discussed in a given metropolitan area. Second, the level of generality also means that we should not dismiss the relevance of material interests for metropolitan integration support too fast. One can imagine that more tailored measurements of egotropic and sociotropic concerns in a specific reform context would generate more significant results. However, this does not affect the conclusion that socio-psychological factors are relevant to the study of metropolitan integration. A next important step would thus entail a systematic study of the interactions between material and socio-psychological explanations and a test of whether some of the socio-demographic or behavioural traits antecede attitudinal factors used in the analysis.Footnote10 Doing so would also allow one to go beyond the correlational nature of this study and to determine whether the reported patterns bear causal significance as well.

Despite these limitations, the findings of this study can inform different research areas. For metropolitan governance research, they suggest that the debate on integration and fragmentation needs to move beyond the technocratic discourse on efficiency and effectiveness of governance structures. More specifically, this output-focussed ‘policy’ perspective needs to be complemented with a more input-focussed ‘politics’ perspective that emphasises political processes. Questions related to collective identities and political communities, their absence, presence or emergence at different spatial scales, need to enter the debate on metropolitan governance. Such a discussion on the shared fate of citizens living in the same city-region seems all the more important in times of increasingly polarised urban political geographies (Sellers et al. Citation2013). Moreover, the strong correlation between confidence in the local political system and metropolitan integration support points to the important role of democratic processes for democratically legitimate metropolitan governance reforms (see also Strebel et al. Citation2019). Instead of implementing such reforms top-down (like in the case of the Greater London Authority), metropolitan governance reforms ideally would follow a bottom-up approach, where reform decisions are made by local actors. This might prevent the adverse effects such reforms can have on citizens’ attitudes towards democracy (Hansen Citation2015). In short, including citizens in metropolitan governance reform processes seems pivotal to enhance their democratic acceptability.

The results also corroborate established findings from public opinion research. They emphasise the importance of socio-psychological factors and processes, such as the use of heuristics, for citizens’ perceptions of political issues, in addition to their material interests. Moreover, the results also point to the relevance of information as a moderating variable. The interaction between service satisfaction and local media use suggest that more informed individuals rely less on heuristics and cognitive shortcuts than less informed citizens. This is perfectly in line with central assumptions of public opinion theory (Zaller Citation1992). An additional established finding in this literature is that material interests matter for political issue perceptions particularly among well-informed individuals. Future research could assess the relevance of this interaction also in the context of subnational governance reforms. Ideally, this would be done by focussing on a specific reform or by relying on experimental approaches that allow for the manipulation of respondents’ gains and losses from a specific policy. Such a design would also allow for a more causal interpretation of the findings.

For multilevel governance research, the findings point to covariations of socio-psychological factors and multilevel governance perceptions that are independent of territorial scales. Territorial identities and the political divide between GAL and TAN parties do not only shape attitudes towards European integration (Hooghe and Marks Citation2018) but also appear to matter for metropolitan governance perceptions. The findings on citizens’ cognitive engagement point in a similar direction. Importantly, they corroborate the well-documented extrapolation of trust in national governments on European integration support in the metropolitan context (Harteveld et al. Citation2013). Thus, more fundamental patterns and underlying mechanisms rooted in socio-psychological factors seem to transcend territorial scales and shape citizens’ perceptions of multilevel governance. Acknowledging and researching these patterns across territorial scales will help to identify their wider significance and to cope with the practical and normative challenges of multilevel governance in a globalised world.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.9 MB)Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this article have been presented at the Annual Conference of the European Urban Research Association 2018 in Tilburg, the ECPR General Conference 2018 in Hamburg, the Political Psychology Colloquium at the Department of Political Science, University of Zurich, and at the ECPR Joint Sessions 2019 in Mons. I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of West European Politics, as well as Macarena Ares, Céline Colombo, Alice el-Wakil, David Kaufmann, Daniel Kübler, Lucas Leemann, Anders Lidström, Marco Steenbergen, Filipe Teles, Maxime Walder, Rebecca Welge, and the participants of these workshops for helpful comments and suggestions. Eleanor Willi provided excellent research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michael Andrea Strebel

Michael Andrea Strebel is a post-doctoral researcher at the Institute of Political Studies, University of Lausanne. His research interests include public opinion, multilevel governance, territorial reforms, urban elites and democratic legitimacy. He has recently published work in Comparative European Politics, in the European Journal of Political Research and in the Urban Affairs Review.

Notes

1 This article focuses on institutional reforms among local governments. Reforms that involve public-private partnerships or some form of network governance are not considered here (see Le Galès and Harding Citation1998: 133).

2 To have a cross-nationally comparable definition of metropolitan areas, Eurostat’s (Citation2013) ‘functional urban area’ definition is used for the survey. The sample is stratified to reflect the population distribution between center city and surrounding areas.

3 Question wording in Online Appendix B.

4 In total, 157 respondents were excluded from the sample due to satisficing behavior, i.e. always ticking the same categories independently of the question, a problem common in online surveys.

5 Further robustness checks can be found in Online Appendix E.1.

6 Question wording in Online Appendix B and descriptive statistics in Online Appendix C.

7 In an evaluation of the quality of multilevel estimates with varying numbers of groups and group sizes, Maas and Hox (Citation2005) find that less than 50 groups at level-2 lead to biased estimates. By contrast, they do not find a minimum requirement for group size. In the case at hand, the 5052 respondents are nested in 1347 municipalities. The minimum requirement for group number is thus clearly fulfilled. The minimum group size is 1, the average 3.8, and the maximum 83 respondents.

8 The corresponding regression models can be found in Online Appendix D. The results shown here display the coefficients from the full model. In addition to the full model, Table D.2 includes separate models for control variables, for group-based, and for cognitive factors only. The analyses presented here are performed on a listwise deleted sample, i.e. respondents with missing values on one of the variables were excluded. To assess the model quality, I inspected the post-estimation correlation matrix of the independent variables for multicollinearity and the level-1 and level-2 residuals for non-normality and heteroskedasticity (see Hox Citation2010: 23–8). None of these are issues for the case at hand. In addition, likelihood ratio tests suggest that the full model fits the data better than any of the nested models in Table D.2.

9 One concern the reader might have is that the correlation between trust and integration support is not due to an extrapolation from the local to the metropolitan level, but rather due to a more general negative link between political disaffection and support for political reforms. To assess this, I have tested whether trust in national government and feeling of external political efficacy in national politics are also associated with support for metropolitan integration (see Online Appendix E.3). The results show that national trust/efficacy feelings are also associated with metropolitan integration support, but that this relationship is less strong than the one between local trust/efficacy feelings when both indicators are included in the model. This suggests that part of the correlation might also be about general political disaffection, but that it is mostly about extrapolation.

10 Yet, a stepwise testing of the different factors (see Table D.2 in Online Appendix D) does not provide strong evidence for this.

References

- Anderson, Christopher J. (1998). ‘When in Doubt Use Proxies. Attitudes towards Domestic Politics and Support for European Integration’, Comparative Political Studies, 31:5, 569–601.

- Bergholz, Christian, and Ivo Bischoff (2019). ‘Citizens’ Support for Inter-Municipal Cooperation: Evidence from a Survey in the German State of Hesse’, Applied Economics, 51:12, 1268–83.

- Davidov, Eldad, Bart Meuleman, Jan Cieciuch, Peter Schmidt, and Jaak Billiet (2014). ‘Measurement Equivalence in Cross-National Research’, Annual Review of Sociology, 40:1, 55–75.

- De Vreese, Claes H., and Hajo G. Boomgaarden (2005). ‘Projecting EU Referendums: Fear of Immigration and Support for European Integration’, European Union Politics, 6:1, 59–82.

- Edwards, Patricia K., and James R. Bohland (1991). ‘Reform and Economic Development: Attitudinal Dimensions of Metropolitan Consolidation’, Journal of Urban Affairs, 13:4, 461–78.

- Ejrnaes, Anders, and Mads Dagnis Jensen (2019). ‘Divided but United: Explaining Nested Public Support for European Integration’, West European Politics, 42:7, 1390–419.

- Eklund, Niklas (2018). ‘Citizens’ Views on Governance in Two Swedish City-Regions’, Journal of Urban Affairs, 40:1, 117–29.

- Eurostat (2013). Territorial Typologies for European Cities and Metropolitan Regions, available at http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Territorial_typologies_for_European_cities_and_metropolitan_regions (accessed 13 April 2021).

- Filer, John E., and Lawrence E. Kenny (1980). ‘Voter Reaction to City-County Consolidation Referenda’, The Journal of Law and Economics, 23:1, 179–90.

- Fitjar, Rune D. (2010). ‘Explaining Variation in Sub-State Regional Identities in Western Europe’, European Journal of Political Research, 49:4, 522–44.

- Fuchs, Dieter, Raul Magni-Berton, and Antoine Roger (2009). Euroscepticism: Images of Europe Among Mass Publics and Political Elites. Opladen: Budrich.

- Hansen, Sune Welling (2015). ‘The Democratic Costs of Size: How Increasing Size Affects Citizen Satisfaction with Local Government’, Political Studies, 63:2, 373–89.

- Harteveld, Eelco, Tom Van Der Meer, and Catherine E. De Vries (2013). ‘In Europe We Trust? Exploring Three Logics of Trust in the European Union’, European Union Politics, 14:4, 542–65.

- Hawkins, Brett W. (1966). ‘Public Opinion and Metropolitan Reorganization in Nashville’, The Journal of Politics, 28:2, 408–18.

- Heinisch, Reinhard, and Vanessa Marent (2018). ‘Sub-State Territorial Claims Making by a Nationwide Radical Right-Wing Populist Party: The Case of the Austrian Freedom Party’, Comparative European Politics, 16:6, 1012–32.

- Helbling, Marc, and Sebastian Jungkunz (2020). ‘Social Divides in the Age of Globalization’, West European Politics, 43:6, 1187–210.

- Henderson, Ailsa, Charlie Jeffery, and Daniel Wincott (2014). Citizenship after the Nation State: Regionalism, Nationalism and Public Attitudes in Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hobolt, Sara B., and Catherine E. De Vries (2016). ‘Public Support for European Integration’, Annual Review of Political Science, 19:1, 413–32.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks (2005). ‘Calculation, Community and Cues’, European Union Politics, 6:4, 419–43.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks (2018). ‘Cleavage Theory Meets Europe’s Crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the Transnational Cleavage’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:1, 109–35.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, Gary Marks, and Carole J. Wilson (2002). ‘Does Left/Right Structure Party Positions in European Integration?’, Comparative Political Studies, 35:8, 965–89.

- Hox, Joop J. (2010). Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications. New York: Routledge.

- Inglehart, Ronald (1970). ‘Cognitive Mobilization and European Identity’, Comparative Politics, 3:1, 45–70.

- Kübler, Daniel (2018). ‘Citizenship in the Fragmented Metropolis: An Individual-Level Analysis from Switzerland’, Journal of Urban Affairs, 40:1, 63–81.

- Keating, Michael (2008). ‘Thirty Years of Territorial Politics’, West European Politics, 31:1–2, 60–81.

- Le Galès, Patrick, and Alan Harding (1998). ‘Cities and States in Europe’, West European Politics, 21:3, 120–45.

- Lefèvre, Christian (1998). ‘Metropolitan Government and Governance in Western Countries: A Critical Review’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 22:1, 9–25.

- Lidström, Anders (2006). ‘Commuting and Citizen Participation in Swedish City-Regions’, Political Studies, 54:4, 865–88.

- Lidström, Anders (2018). ‘Territorial Political Orientations in Two Swedish City-Regions’, Journal of Urban Affairs, 40:1, 31–46.

- Lyons, William E., David Lowery, and Ruth Hoogland DeHoog (1992). The Politics of Dissatisfaction. Citizens, Services, and Urban Institutions. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe.

- Maas, Cora J. M., and Joop J. Hox (2005). ‘Sufficient Sample Size in Multilevel Modeling’, Methodology, 1:3, 86–92.

- Mohamed, Rayman (2008). ‘Who Would Pay for Rural Open Space Preservation and Inner-City Redevelopment? Identifying Support for Policies That Can Contribute to Regional Land Use Governance’, Urban Studies, 45:13, 2783–803.

- NCCR Democracy (2016). Democratic Governance and Citizenship Regional Survey [Dataset], University of Zurich, Distributed by FORS, Lausanne, 2019, Retrieved from https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.23662/FORS-DS-954-1.

- Norris, Donald F. (2016). Metropolitan Governance in America. New York: Routledge.

- Ostrom, Elinor (1972). ‘Metropolitan Reform: Propositions Derived from Two Traditions’, Social Science Quarterly, 53:3, 474–93.

- Sager, Fritz (2006). ‘Policy Coordination in the European Metropolis: A Meta-Analysis’, West European Politics, 29:3, 433–60.

- Schreiber, James B., Amaury Nora, Frances K. Stage, Elizabeth A. Barlow, and Jamie King (2006). ‘Reporting Structural Equation Modeling and Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results: A Review’, The Journal of Educational Research, 99:6, 323–38.

- Sellers, Jefferey M., Daniel Kübler, Melanie Walter-Rogg, and Alan R. Walks (2013). The Political Ecology of the Metropolis. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Strebel, Michael A. (2019). ‘Why Voluntary Municipal Merger Projects Fail: Evidence from Popular Votes in Switzerland’, Local Government Studies, 45:5, 654–75.

- Strebel, Michael A., Daniel Kübler, and Frank Marcinkowski (2019). ‘The Importance of Input and Output Legitimacy in Democratic Governance: Evidence from a Population-Based Survey Experiment in Four West European Countries’, European Journal of Political Research, 58:2, 488–513.

- Tiebout, Charles M. (1956). ‘A Pure Theory of Local Expenditures’, The Journal of Political Economy, 64:5, 416–24.

- Verhaegen, Soetkin, Louise Hoon, Camille Kelbel, and Virginie Van Ingelgom (2017). ‘A Three-Level Game: Citizens’ Attitudes About the Division of Competences in a Multilevel Context’, in Kris Deschouwer (ed.), Mind the Gap: Political Participation and Representation in Belgium. Colchester: ECPR Press, 133–59.

- Walter-Rogg, Melanie (2018). ‘What about Metropolitan Citizenship? Attitudinal Attachment of Residents to Their City-Region’, Journal of Urban Affairs, 40:1, 130–48.

- Wicki, Michael, Sergio Guidon, Thomas Bernauer, and Kay Axhausen (2019). ‘Does Variation in Residents’ Spatial Mobility Affect Their Preferences Concerning Local Governance?’ Political Geography, 73, 138–57.

- Zaller, John R. (1992). The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.