Abstract

The COVID-19 crisis has demanded that governments take restrictive measures that are abnormal for most representative democracies. This article aims to examine the determinants of the public’s evaluations towards those measures. This article focuses on political trust and partisanship as potential explanatory factors of evaluations of each government’s health and economic measures to address the COVID-19 crisis. To study these relationships between trust, partisanship and evaluation of measures, data from a novel comparative panel survey is utilised, comprising eleven democracies and three waves, conducted in spring 2020. This article provides evidence that differences in evaluations of the public health and economic measures between countries also depend on contextual factors, such as polarisation and the timing of the measures’ introduction by each government. Results show that the public’s approval of the measures depends strongly on their trust in the national leaders, an effect augmented for voters of the opposition.

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1930754 .

The policy responses in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic that swept the globe from late 2019 onwards presented unique challenges for democratic representation. Faced with the urgency and scale of the problem pressure, elites of democratic societies had to take quick measures to ensure the health system could cope with the surge of coronavirus cases and to respond rapidly to the economic consequences of the crisis. The rapid spread of the virus implied that elites had to take such decisions without much time to consult with the general public. In the absence of a real public debate on the measures, a quintessential link of government responsiveness was broken. If there is no time to consult and debate measures, elites have no or only limited knowledge of what the public wants, making it hard for them to respond to majority opinion. Even more problematically, given the unprecedented nature of pandemic politics, citizens have been unable to rely on past experiences, accumulated knowledge and the usual information sources – mass media, social media, trusted experts, social circles, etc. – to form coherent preferences on the proper remedies. In the cacophony of punditry and a torrent of often-conflicting information overflowing the airwaves, any preference aggregation of the public was going to be ridden with difficulties on various fronts. Under these constraints, governments were sailing in uncharted waters, having to take initiative without much input from public opinion.

The unique nature of the pandemic also implies that understanding the extent and the sources of the public’s (dis)approval of the policy responses is even more crucial than in crisis moments in the past. Though policy evaluations on particular issue domains have long been shown to have the potential to make or break governments, or at least shape their re-election prospects (Cavari Citation2019; Goerres and Walter Citation2016; Highton Citation2012), the current pandemic may point beyond ‘business as usual’ with more far-reaching consequences. Decisions that decide the fate of thousands of lives coupled with the sharpest fall in economic activity in the post-war period may be expected to trigger what Roberts (Citation2008) referred to as ‘hyper-accountability’ in the context of post-communism transition. Simply put, when there is more at stake compared to normal times, the electoral repercussions are likely to be greater, possibly making policy evaluations in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic one of the most important pieces of political information for the future of electoral politics in the Western world and beyond. Alternatively, during periods of crises, citizens may tend to uncritically throw their support to sitting governments (at least in the initial stages of the crises) to find solutions to their immediate fears and concerns. This eagerness for solutions may make them less appreciative of the normal process of democratic politics which includes critical opposition parties and vigilant media. Thus, previous work on the COVID-19 crisis (Bol et al. Citation2021) tends to suggest that citizens in the early phases of the crises were more supportive of their governments and more satisfied with their democratic institutions. Even in contexts where political leaders appeared to grossly mismanage the policy response early on, such as in the US and Brazil, leaders’ approval ratings held steady or even enjoyed a modest bounce. This type of ‘rally-round-the-flag’ dynamic may have been particularly pronounced during the COVID-19 crisis precisely because it was difficult to assess the performance of governments due to the technical nature of the topic.

Moreover, policy evaluations have the potential to shape the course of the pandemic itself. A citizenry convinced of the appropriateness of stringent lockdown measures is more likely to display higher levels of compliance, and to maintain this compliant attitude over time, a crucial determinant of the measures’ success. In this sense, early policy evaluations can be conceptualised as triggers for a virtuous or a vicious cycle between public opinion and policy output: when policy evaluations are positive and compliance with the measures is high, governments are likely to be more successful at suppressing the pandemic which in turn retrospectively justifies positive policy evaluations in the first place. Conversely, under a more distrustful public displaying higher levels of non-compliance, the infection curve is likely to be stickier, underscoring the sceptics’ view. Which way the cycle goes can then shape the room for political manoeuvre for governments in the face of subsequent waves of the pandemic.

In this article, we pursue two related goals. Building on an original survey fielded in 10 countries, we first trace the evolution of COVID-19-related policy evaluations in the public health and the economic domain. We aim to understand whether the public’s evaluations were more critical this time, in line with Roberts’ (Citation2008) theory of ‘hyper-accountability’ or whether they followed a ‘rally-around-the-flag’ pattern with wide-spread support for governments in a time of emergency as suggested by Bol et al. (Citation2021). Second, we seek to understand the individual-level determinants of policy evaluations by highlighting the role of two crucial dispositional factors shaping political behaviour: political trust and ideology (partisanship). Third, we shall highlight two contextual conditions that we regard as key to predicting average levels of policy evaluations across countries. First, we shall zoom in on the role of problem pressure (see Dimick et al. (Citation2018) for a review of how problem pressure is linked to redistribution preferences) in the form of the different trajectories of the infection rates in different countries and at what point governments took decisive measures to ‘flatten the curve’. Second, we highlight the role of political context in general and mass-level polarisation in particular as likely determinants of average policy evaluations.

In order to preview the main findings, we provide evidence that trust in political leadership and partisanship play a central role in the evaluation of governments’ public measures to tackle COVID-19. Our results indicate that trust is strongly associated with positive evaluations, as voters of the opposition who nonetheless trust the government tend to have a better opinion of the measures’ efficacy in battling COVID-19. We provide evidence however that this strong relationship between trust and measure evaluation may be tempered by contextual circumstances. Political systems featuring high levels of polarisation tend to undermine this effect, as opposition voters almost never trust the government. We also demonstrate that the timing of the measures’ adoption relative to other countries affects the public’s perception of their effectiveness.

The article proceeds as follows. In the next section we theorise what we consider as the ‘baseline’ expectation on policy evaluations in the context of a high-stakes crisis informed by the ‘rally-around-the-flag’ phenomenon prominent in the public opinion and political behaviour literature. However, we bring in the role of trust and ideology as likely predictors of policy evaluations, acting as a brake in the rally. The following section discusses the characteristics of our survey data and presents descriptive patterns across countries and over time. In the penultimate section we lay out our empirical strategy and build logistic regression models to test our hypotheses. The last section concludes.

Trust, partisanship and performance during the COVID-19 crisis

Policy evaluations are part and parcel of democratic representation because an informed citizenry with clear policy preferences allows elites to respond to majority opinion. In the most salient issues of day-to-day politics – redistribution, social policies, immigration policy, law and order policies, environmental measures, etc. – these preferences tend to pit groups supporting government policies against those opposing them. The relative size of the groups depends on a host of factors, such as the relative size of material winners and losers, the ideological distribution of the electorate, the government’s standing in the polls, among others. In certain exceptional circumstances, however, studies on political behaviour found that this stand-off gives way to moments of grace for governments. In such times, an overwhelming majority of citizens lines up behind the government, resulting in what Mueller (Citation1970) coined as the ‘rally around the flag’ effect: a short-term boost to political leaders’ popularity or job approval. The most common examples of this phenomenon occur on the eve of foreign military interventions (Baker and Oneal Citation2001; Callaghan and Virtanen Citation1993; Groeling and Baum Citation2008; Norrander and Wilcox Citation1993), terror attacks (Brouard et al. Citation2018; Hetherington and Nelson Citation2003), and natural disasters (Reeves Citation2011; Velez and Martin Citation2013). The acute sense of national crisis in the wake of these events is likely to give rise to rare moments of national unity when dramatic jumps of government approval are the norm and even the party-political opposition tacitly goes along with government initiatives (Chowanietz Citation2011). Though most studies of the rally analysed the phenomenon with approval ratings as the dependent variable, in this study we extend its application to more narrowly defined policy evaluations in specific issue domains: the healthcare policy response and the economic policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

We posit that much like 9/11 and natural disasters, the COVID-19 pandemic was an exogenous, unforeseen shock, and within this context the behaviour of the public vis-à-vis the government should be expected to mimic other such similar situations and crises. With daily headlines dominated by infection counts and mortality statistics, the general public needed no special reminder that far from living in ordinary times, it was possibly witnessing the crisis of its lifetime. In this article therefore, we aim to decode political behaviour in the context of the pandemic. We do this in two steps, first by describing some important contextual factors that might differentiate public opinion in various countries and then by applying a comparative, statistical analysis, based on survey data, to the relationship between evaluations of government measures, trust and partisanship.

First, we want to explore whether a short-term rally was present in this context, given that the sudden and shocking nature of the pandemic crisis was likely to trigger such a phenomenon and predispose the public positively towards the government compared to normal times. As the crisis unfolded, it is likely that the perception of the COVID-19 emergency as an extraordinary and dangerous event, focussing the public’s mind, was accompanied by an increased support of the government measures dealing with it. As such, we would expect that in the initial phases of the pandemic, government policies would be supported by an overwhelming majority of public opinion.

These rallies, however, are likely to be highly context dependent. One major difference in context is the sheer scale of the pandemic and the perceived timeliness and scale of the government responses to it. While some leaders, such as US President Donald Trump and Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, were notorious for downplaying the significance of COVID-19 by likening it to a flu, others, such as Italian premier Giuseppe Conte and New-Zealander premier Jacinda Ardern, implemented severe lockdown measures early on. Of course, the stringency of the measures should be understood in the context of the underlying infection curve: timely and untimely responses are defined by a given country’s position on the curve at the time the measures were adopted. In particular, it is probable that as the scale of the pandemic became clearer to the citizenry, they became more supportive of stringent health care measures in line with the rally hypothesis and were more likely to evaluate health care policies positively when timely measures were taken. Therefore, we should expect that where measures were introduced at an earlier stage of the infection curve, i.e. before the virus spread uncontrollably, the citizens, evaluating the government’s ability to provide timely measures would have been more supportive of its measures than in countries where the pandemic was not dealt with at the outset of the crisis.

Additionally, as lockdowns gave rise to economic grievances alongside public health concerns, a mirror logic dictates that the evaluation of the economic interventions should be put in context of the stringency of the health containment measures and the resulting economic hardship. From the economic angle then, it is not the combination of timeliness and content, like for health measures, that matters, but rather the generosity of the economic responses, relative to the economic fallout and the lockdown’s stringency. It is more likely that positive evaluations of the economic measures were more frequent where the measures of economic relief were more generous, if one compares countries with equally stringent lockdowns.

The perception of the timeliness and the generosity of the measures, however, is also largely a political act in itself, clouded and driven by partisan biases in the interpretation of facts (Bartels Citation2002; Bullock and Lenz Citation2019). The extent to which such partisan biases are prevalent in the electorate is thus likely to have a crucial impact on the evaluation of the governments’ policy response. In particular, we posit that partisan polarisation is another variable that influences policy evaluations in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. In relatively non-polarised settings, the dynamics of the rally are likely to act as a centripetal force across the political spectrum. In more polarised settings, where the opposition voters are more suspicious and inherently hostile to the government, it is likely that they will demonstrate lower levels of support for the government measures, hence a lower share of the citizens would be expected to support government policies

Having established the contextual factors that might influence the existence and scale of a rally-around-the-flag phenomenon and generally the approval of government policies within the pandemic across countries, we next aim to examine individual political behaviour in the context of the pandemic, in a comparative perspective. Even in settings that create the perfect conditions for a political rally, it is likely to dissipate, though more or less quickly, after a certain some point, as immediate concerns about the pandemic give way to economic hardship, lockdown fatigue and a general desire to return to normality. The natural question that arises then concerns the type of individuals that grow more critical of the government. We expect the main dividing line to emerge from dispositional factors because sociodemographic profiles offer little guidance in times of deep uncertainty and a general lack of experience with comparable crisis situations at the mass level. In particular, we zoom in on the role of political trust and partisanship as the most likely individual-level determinants for driving a wedge between supporters and critics of government responses to COVID-19.

Although there is considerable debate in the literature about the extent to which contemporary survey measures of political trust tap into the diffuse sort of regime support that Easton (Citation1965) put forward originally,Footnote 1 it suffices for our purposes to understand trust as a heuristics device that establishes a link between citizens and the elites irrespective of their agreement with any particular issue of the day. As formulated by Rudolph (Citation2017), ‘political trust functions as a heuristic or decision rule that helps people decide whether to support or oppose government action’ (Rudolph Citation2017: 197). The empirical trust literature has indeed found a strong link between trust and policy evaluations. Hetherington and Globetti (Citation2002) find a significant impact of political trust on race policy preferences in the United States while Rudolph (Citation2009) uses a political trust variable to predict tax cut initiatives during the first G.W. Bush administration. In both accounts, however, the impact of trust (in government) is contingent on race and ideology, respectively. In the European context, the impact of political trust (in government) has been found to be influential to explain support for welfare state reform (Gabriel and Trüdinger Citation2011), environmental policy instruments (Harring Citation2018), and migration and asylum policy preferences (Jeannet et al. Citation2020).

In most issue areas studied by the trust literature, citizens can simultaneously rely on trust as a heuristic device and their issue-specific knowledge and preferences to form their performance evaluations. By contrast, in an environment characterised by deep uncertainty and very little issue-specific knowledge by ordinary voters, we expect an especially tight link between trust and policy evaluations because other sources of opinion formation will offer little guidance to voters. Moreover, performance evaluation in the course of a pandemic is tightly intertwined with citizens’ propensity to comply with the law. In their recent review on political trust, Citrin and Stoker (Citation2018) discuss a number of studies that document a positive relationship between trust and compliance standards. Extending the compliance logic to the COVID-19 pandemic, we can thus expect that even as trusting citizens are more likely to comply with the law, they are more likely to display higher propensities to agree with the policy measures taken by the governments. We thus formulate our trust hypothesis as follows:

H1 – Trust hypothesis: Citizens who display higher levels of trust in government (political trust) tend to evaluate government responses to COVID-19 more positively in both the health and the economic domain.

In addition to the diffuse sense of political trust, governments can tap into another source of popular support for their response measures, which is more directly oriented at particular governments in power. Though declining in recent years in most countries, with the notable exception of the US (Clarke and Stewart Citation1998; Holmberg Citation2007), partisanship continues to serve as a ‘perceptual screen’ through which citizens view the world (Bullock and Lenz Citation2019; Holmberg Citation2007). In fact, partisan identifiers form vastly different opinions on such factual information as the state of the economy (Iyengar et al. Citation2019) and a large portion of them are predisposed to sign up to conspiracy theories to delegitimize partisans and the leadership of competing parties (Bullock and Lenz Citation2019).

It does not take a conspiratorial mindset or even an excessive dose of motivated reasoning (Kunda Citation1990; Leeper and Slothuus Citation2014; Milton and Taber Citation2013) to anticipate partisan alignment with governments to be closely aligned with performance evaluations in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. In a logic similar to political trust, partisanship might offer the kind of perceptual screen for citizens that enables them to support government measures in the face of deep uncertainty, as they might accommodate facts to their pre-existing worldview (Bisgaard Citation2019). Citizens suspicious of the intentions and competence of the government are much less likely to support their policy initiatives than those whose general partisan affiliations are towards governing parties. For instance, in the case of economic measures, partisan supporters of centre-left governments might offer executives the benefit of the doubt and presuppose that their stimulus measures are at least partly driven by considerations of social justice compared to measures offered by right-leaning governments. Even in the public health domain where substantive ideological differences are expected to play a relatively muted role, partisan supporters of government parties are likely to presuppose that elected officials will choose a policy mix that best protects the citizenry at large but also (and perhaps particularly) their voting base. We can thus formulate our fourth hypothesis as follows:

H2 – Partisan alignment hypothesis: Partisan supporters of government parties tend to offer more positive policy evaluations over the course of the pandemic compared to opposition voters or non-voters.

Moreover, the associations between trust and partisanship on the one hand and policy evaluations on the other need not necessarily combine in a linear and additive manner as the trust hypothesis and the partisan alignment hypothesis imply. For that matter, a prominent finding in the trust literature is that the impact of trust is greatest among those voters who have to pay a greater ‘ideological sacrifice’ in the face of a particular policy proposal. For instance, Rudolph (Citation2009) and Rudolph and Popp (Citation2009) analyse the determinants of support for tax cuts and social security privatisation, respectively, in the G.W. Bush era and find that the impact of trust is greater among liberals, in other words among voters who are ideologically opposed to these initiatives. Though such prior ideological opposition to public health and economic intervention is unlikely to be prevalent in the face of a public health emergency and an economic meltdown, the notion of ideological sacrifice can be readily extended to partisanship. Opponents of government parties (opposition partisans) need to first overcome their aversion to government parties in order to evaluate their policy responses positively and a relatively higher level of trust in government may provide the right dispositional push to achieve this. By contrast, government voters are likely to be positively predisposed towards policy initiatives by governments to begin with and their trust levels are unlikely to make a large difference in their already supportive evaluations. We thus expect that trust and partisanship interact in what we call the ideological sacrifice hypothesis:

H3 – Ideological sacrifice hypothesis: The link between trust and policy evaluations is tighter among opposition voters than among government voters.

As a final consideration, note that both the trust hypothesis and the partisan alignment hypothesis anticipate differences between citizens to emerge from the start. However, combining them with the rally hypothesis should lead one to expect that the differences are muted in the beginning but grow larger over time as the initial rally gives way to scepticism and critique. This critique is likely to mark a divergence between trusting and distrusting citizens on the one hand, and partisan supporters of the government and opposition voters (or non-voters), on the other. We thus formulate our last hypothesis which embeds the trust and the partisan alignment hypotheses in a dynamic context:

H4 – Divergence hypothesis: Differences in policy evaluation between trusting and distrusting citizens as well as between partisans and non-partisans grow over time as the initial rally gives way to scepticism and critique by parts of the citizenry.

Research design

In order to test our hypotheses, we use a collection of panel data in ten different countries gathered during the months of the first wave of the COVID-19 crisis, in three separate waves (see list of countries in Online appendix A1). The first wave was fielded between March 24–30, when the COVID-19 crisis in Italy reached its peak and started to spread elsewhere in Europe. The second wave occurred between April 15–18, as the COVID-19 crisis had just passed it peak and relaxation measures were being discussed. The last wave was fielded between June 21–28, as cautious relaxation measures had already taken place in most of Europe. Overall, we have a sample of 39,018 individuals replying to at least one of the questionnaires. For two countries, Sweden and Poland, the first wave is missing, while for one country, France, we have had a disproportionately large number of responses. To address this, we only kept a sub-sample from France, namely the waves from the French surveys that correspond to the dates when the panels were conducted in other countries. The utilised sample for each panel is reported in in the online appendix.

Table 1. Polarisation in the 10 countries: coefficient of variation of trust in government, per country.

Performance evaluations constitute the dependent variables in our analyses, while political trust and partisanship are our main independent variables. Performance evaluations are based on a question asking respondents whether they consider that the measures taken by their respective government to protect their health were inadequate, exaggerated or neither, on a 1–5 ordinal scale (ranging from very inadequate to really exaggerated). We create three dummy variables for each type of measure, which indicate whether a respondent considered the measures exaggerated or not, inadequate or not, or neither exaggerated nor inadequate.

Political trust is measured by the question whether respondents trust the Prime Minister (in parliamentary systems) or the President (in presidential or semi-presidential systems: US, France, Poland), measured on a four-point ordinal scale, ranging from complete trust to no trust at all. Finally, as a proxy for partisanship, we utilise the reported vote intentions of respondents. We then separate respondents into government voters on the one hand, and opposition voters and non-voters on the other hand. Additionally, we operationalise timing (and the divergence hypothesis) by creating a dummy for the panel wave in which a respondent participated.

Furthermore, we introduce three country-specific indicators to explore differences in initial levels of government support arising from contextual factors such as the timing of measures or previously-existing polarisation within a country. To measure polarisation, considering the lack of conventional indicators in our data, e.g. a like/dislike scale for all politicians, we use the coefficient of variation for trust in the government as a proxy.Footnote 2 While admittedly non-ideal, it is conceptually similar to other measures of polarisation and its measurement strategy based on micro-data (Lauka et al. Citation2018; Levendusky and Malhotra Citation2016; Reiljan Citation2020). The greater the variation in trust in the government, the greater the polarisation in the political system. presents the classification according to this indicator. Four countries, Poland, the US, France and the UK clearly stand out as highly polarised, compared to the other six with either medium or low levels of polarisation.Footnote 3

A second contextual indicator we rely on is the timing of the public health measures. More specifically, we pinpoint the date when countries took stringent lockdown measures relative to the countries’ location on the infection curve and to their peers. We rely on the ‘stringency’ index designed by a team of researchers at the Oxford COVID-19 database (Hale et al. Citation 2020).Footnote 4 We define countries as first movers and latecomers depending on the number of cases/deaths before its stringency index reached a certain threshold,Footnote 5 and on whether the country was consistently behind its peers in implementing lockdown measures.Footnote 6 In sum, a country is considered a latecomer if it takes measures too late compared to its epidemic curve and in relation to its peers. Under this definition, also shown in Online appendix Table A2, New Zealand, Poland, France and Italy are first movers, taking measures early in their epidemic curve and in relation to other countries, while Germany, the UK, the US, Australia and Sweden are latecomers. Austria is an intermediate case due to a small lag compared to other countries, but as it does not fulfil both criteria to be a latecomer and the relatively slow evolution of its epidemic curve evolution justifies this lag, we include it in the first-mover category.

With respect to economic measures, we distinguish the countries based on the generosity of the measures adopted. We again use the Oxford COVID-19 database to distinguish between generous and restrained economic support. We focus on two indicators measuring economic support of households: income support and debt relief. Both indicators have three levels – no, partial, or comprehensive support. The difference between partial and comprehensive support is defined for both indicators as support exceeding fifty percent of the income loss/median income or of contractual obligations in the case of debt relief. We designate countries as restrained if they failed to provide comprehensive support in terms of either measure within a month since the first containment measures. Within our sample, as shown in Online appendix Table A3, only Italy and Poland qualify as restrained, as they extended only modest economic support to their citizenry both in terms of income and debt relief support. The other countries provided generous support in terms of either debt relief (Australia) or income support (Germany, Sweden, New Zealand (which also gave debt relief belatedly) or both (Austria, France, UK, US).

We proceed by first providing descriptive evidence for the rally and some tentative explanation for its variation across countries based on contextual factors, such as polarisation and timing/generosity of measures. Having explored these potential causes of inter-country differences in the support for government measures at the pandemic’s start, we then run logistic regression models, using panel data, to test our hypotheses on the effects of trust and partisanship/government support (H1, H2) on the public’s evaluation of health and economic measures as well as their interaction (H3). In these regression models, we also examine whether the rally fades away by the time the later panel waves were fielded (H4).

Analysis

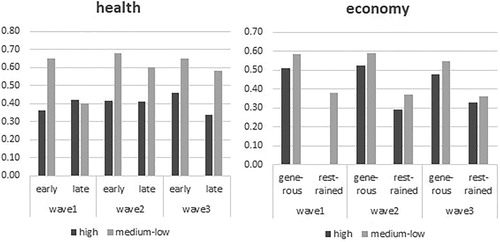

Initially, we postulated that a large number of citizens would approve of the measures in response to the sense of national crisis and the ‘rally around the flag’ that this widespread sentiment triggers. In , we can see that there is no universal rally around government measures in all of our countries, but instead it varies greatly by country.

Figure 1. Evaluation of the public health and economic measures taken by the governments in the COVID-19 crisis, by wave, polarisation, timing and generosity of the measures: shares of respondents who are assessing the measures as adequate.

Other factors, that we expected to be influential, indeed seem to be associated with the existence and scale of an initial rally. Specifically, in , we can see that in high polarisation countries, approval of health policies is, on average, markedly lower than in low polarisation countries. The only low polarisation countries for which we witness high disapproval are latecomers in terms of the policy response and only in wave one, i.e. at the initial stages of the pandemic. This is possibly a reflection of a sceptical public, as in some latecomer countries, like Germany or Australia, the public was wary of their governments’ relatively reluctant response to the COVID-19 crises compared to their peers who had already locked down. Similarly, in Sweden, which was an outlier in terms of its approach to dealing with COVID-19 since it avoided a general lockdown, approval for the government’s measures was significantly lower than in other countries with similarly low polarisation. Note, however, that for the low-polarisation latecomers, the corresponding scores improved in subsequent waves.

Similarly, apart from polarisation, it appears that the support for government measures is also loosely correlated with the timeliness of public health measures and the generosity of economic measures. Governments which adopted generous measures obtained better evaluations than governments with restrained measures, which makes sense in light of the large disruption and economic anxiety created by the COVID-19 response. Similarly, governments that reacted late, defying the international consensus on emergency measures, and governments where political trust between the opposing political camps had already eroded at the time the crisis hit were less likely to experience rally-around-the-flag effects in terms of policy evaluations. Due to the relatively limited number of countries in our sample, we are not able to attain statistical certainty about this conclusion and hence we only present these qualitative associations to provide a frame for the initial rally and its scope. It should be noted, however, that polarisation, timing, and generosity do correlate with levels of support for government measures and subsequent shifts as the governments update their policies.

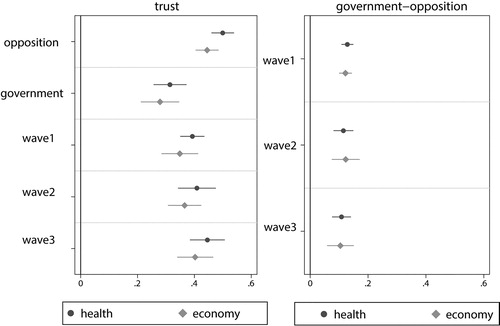

In order to explore our formal hypotheses, we perform a logistic regression, using evaluations of health and economic measures as the dependent variables and trust in the PM/president, support of the government/opposition and a dummy for each panel wave as the independent variables. In this case, the dependent variable is represented by a dummy: the respondents are split between those saying the measures were neither inadequate nor exaggerated versus all the others. The panel regressions include country fixed effects and clustering of standard errors by individual respondents. presents the results in graphical form.

Figure 2. The effects of trust, government–opposition and wave on performance evaluations: predicted probabilities of maximum effect (trust) and average predicted values (government–opposition).

Based on the results presented in Online appendix Table A4 and (left-hand panel), we find evidence to support our trust hypothesis (H1). There is indeed a tendency for people who trust the PM/President of their country to be more likely to be supportive of the COVID-19 measures and the effect is statistically significant and substantively large, producing the largest coefficient estimate amongst our independent variables. Placing trust in the head of the government who leads the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic appears to increase the likelihood of evaluating the measures positively. It should be noted that this association is somewhat stronger for public health measures. One possible explanation could be that the stakes in the field of public health were higher and the reaction of most leaders to the looming pandemic threat was forceful and immediate.

There is also some evidence for the partisan alignment hypothesis (H2), although the associations are weaker compared to the trust hypothesis (, right-hand panel). The results show that voters of government parties are more likely to evaluate the public health and economic measures positively compared to non-aligned and opposition voters. Again, this is in line with the theoretical insights on the effects of partisanship on government performance evaluations: partisan alignment with the government is typically accompanied by more positive evaluations of the government’s policy outputs.

Moreover, the association of trust with the two types of evaluation is considerably stronger among supporters of the opposition than among those of the government. In line with our ideological sacrifice hypothesis (H3), trust in the country’s leadership tends to dampen the negative outlook towards government policies generally held by opposition voters. The results are again stronger for health measures.

Finally, our hypothesis on the expected divergence of evaluations based on trust and partisanship throughout the course of the pandemic (divergence hypothesis – H4) is also confirmed by the data, but only for trust. As we can see from the left-hand panel in , there is evidence of a widening gap of positive evaluations between trustful and distrustful citizens from one wave to the next. This widening gap is in line with the expectation that the initial rally effect is weakening across the waves. We find no such evidence for partisanship. In fact, the corresponding gap between supporters of the opposition and of the government is slightly, but significantly reduced in the third wave, which is to suggest that the rally effect is more persistent with respect to partisanship than with respect to trust in the government. In this respect as well, the results are stronger for the health measures.

Discussion and conclusions

In this article, we set out to explore the relationship between political trust, partisanship and the policy evaluations of governments throughout the first wave of the COVID-19 crisis, and how different contextual factors might influence this equation. Policy evaluations by the public are a crucial aspect of political behaviour during the pandemic, due to their potential effect on citizens’ compliance patterns and the subsequent trajectory of the pandemic. Additionally, the determinants of policy evaluations carry an intrinsic interest for political scientists for comparative purposes: are the usual suspects that determined policy attitudes in past crises applicable for a novel type of national emergency?

With this comparative perspective in mind, we set up our article with expectations derived from the empirical literature on other crises: we questioned if the crisis would lead to an effect akin to Roberts’ hyper-accountability concept or whether we should expect the public to rally around the flag and support the policies of the political leaders. We indeed found qualitative evidence for the latter, as such a rally manifested itself, but only in countries with comparatively low levels of polarisation. We suggested that in polarised settings such as the US and Poland, intense political conflict is unlikely to disappear even if the lives of hundreds of thousands of citizens are at stake. In these countries, distrust in leaders tends to give rise to negative evaluations of their policies on COVID-19, either because the public deems them inadequate or exaggerated, depending on the context. In countries such as New Zealand where the PM was popular and enjoyed a high level of public trust, policy evaluations tended to be much more positive as government and opposition supporters both believed that the governing elite observes minimum standards of public stewardship.

However, this might not be the only mechanism at work here. COVID-19 is much unlike other types of crises studied before, in that the ‘adversary’ is not some terrorist organisation or, as in the case of Europe, intra-union antagonists who are frugal or reckless with spending. Instead, citizens faced an invisible threat and the rally effect might have been limited by the absence of a clear and visible adversary. The crisis was primarily domestic, concerned with public health policies and the credibility of each administration, possibly further accentuating the existing divisions and lack (or presence) of political trust in each country. As such, the question is not about rallying with ‘our’ leader against an ‘other’, but of assessing whether ‘our’ PM/President really has ‘our’ own best interests at heart and/or the competence to steer the ship in troubled waters. This might explain why polarisation and distrust persist in this crisis and how, in countries where leaders had been unpopular before the crisis (such as France), evaluations of their policies were rather negative during the crisis itself. Overall, the unique nature of the crisis presents fruitful grounds for future comparative research on how crisis politics and political behaviour unfold in different crisis contexts.

Furthermore, we saw that the relationship between trust, partisanship and policy evaluations may be influenced by timing. This might be also associated with some of the idiosyncrasies of the COVID-19 pandemic. The fact that the crisis was not linked to one or a limited set of countries, but took place almost simultaneously in every country, arguably triggered the emergence of a sort of ‘international consensus’ about the way the pandemic should be countered. Countries that deviated from this consensus and were perceived by their citizens to endanger their lives received lower evaluation scores than ‘first movers’. Negative evaluations, however, as evidenced by our dynamic analysis, are not necessarily doomed to persist. If the government yielded and followed the international consensus, its citizens’ trust rose along with the positive evaluations of the new, typically more stringent measures.

Overall, we saw that trust in leadership and partisanship may play a significant role in the public’s reaction to government public health and economic measures. As our statistical analysis indicates, trust, particularly among opposition voters, is highly correlated with a positive reception of containment measures. As such, we conclude that robust institutional structures that inhibit political polarisation and create a hospitable environment for consensual leadership may prove to have another beneficial side-effect: positive policy evaluations of, and arguably higher compliance standards with, stringent lockdown measures – with thousands of saved lives as a reward.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (146.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The data were collected for the project ‘Citizens’ Attitudes Under COVID-19 Pandemic’ by the following research team: Sylvain Brouard (Sciences Po – CEVIPOF & LIEPP), Michael Becher (Institute for Advanced Studies in Toulouse & Université Toulouse Capitole 1), Martial Foucault (Sciences Po – CEVIPOF), Pavlos Vasilopoulos (University of York), Vincenzo Galasso (Bocconi University), Christoph Hönnige (University of Hanover), Eric Kerrouche (Sciences Po – CEVIPOF), Vincent Pons (Harvard Business School), Hanspeter Kriesi (EUI), Dominique Reynié (Sciences Po – CEVIPOF).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

Argyrios Altiparmakis, Abel Bojar and Hanspeter Kriesi acknowledge the financial support from the EGPP program of the Robert-Schumann Centre at the European University Institute, as well as from the EU Grant Agreement 810356 – ERC-2018-SyG (SOLID). Martial Foucault and Sylvain Brouard acknowledge the financial support from ANR – REPEAT grant (ANR-20-COVI-0079), CNRS, Fondation de l’innovation politique, as well as regions Nouvelle-Aquitaine and Occitanie. Richard Nadeau acknowledges the financial support from the Fonds de recherches Société et Culture du Québec (2017-SE-205221).

Notes

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Argyrios Altiparmakis

Argyrios Altiparmakis is a Research Fellow at the European University Institute. His research focuses on party politics, political behaviour and the recent European crises. He is currently working on the SOLID-ERC project. [[email protected]]

Abel Bojar

Abel Bojar is a full-time Postdoctoral Researcher at the Department of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute in Florence. [[email protected]]

Sylvain Brouard

Sylvain Brouard is Senior Research Fellow FNSP at Sciences Po – CEVIPOF and Associate Researcher within the Laboratoire Interdisciplinaire d’Evaluation des Politiques Publiques (LIEPP). His research focuses on political attitudes and behaviour, political institutions and law making. Recent publications include articles in the American Journal of Political Science, Electoral Studies and Political Behaviour. [[email protected]]

Martial Foucault

Martial Foucault is a full-time Professor of Political Science at Sciences Po Paris and director of the CEVIPOF (CNRS) and Associate Researcher within the Laboratoire Interdisciplinaire d’Evaluation des Politiques Publiques (LIEPP). His research interests range from political economy to political behaviour, including public policies, fiscal policies and statistical methods. He is also associate editor of the journal French Politics and director of the series Fait Politique (Presses de Sciences Po). [[email protected]]

Hanspeter Kriesi

Hanspeter Kriesi is a part-time Professor at the European University Institute in Florence. He is also affiliated with the Laboratory for Comparative Social Science Research, National Research University Higher School of Economics, the Russian Federation. [[email protected]]

Richard Nadeau

Richard Nadeau is Professor of Political Science at the University of Montreal. His interests are voting behaviour, public opinion and political communication. He has authored or co-authored over 180 articles and book chapters (e.g., American Political Science Review, American Journal of Political Science, Journal of Politics) and 15 books including Anatomy of a Liberal Victory, Latin American Elections: Choice and Change and The Danish Voter: Democratic Ideals and Challenges. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 Hetherington (1998), for instance, uses structural equation models to locate trust measures on the specific–diffuse spectrum and he concludes that it is related to both specific and diffuse regime support.

2 The coefficient of variation is a standardized measure of dispersion, defined as the ratio of the standard deviation over the mean, demonstrating the variability of the sample or population. Greater variation in trust indicates that government–opposition voters are typically further apart, relative to the mean level of trust in the country.

3 This result is probably largely driven by electoral institutions (McCoy and Somer 2019). Thus, three of these countries have majoritarian electoral systems, where the winner-takes-all logic contributes to the polarization between the government and the opposition camp. Poland is the exception, where the legislature is elected in proportional elections (with a 5-percent threshold for parties, and an 8-percent threshold for coalitions). But Poland also has direct presidential elections, which follow the same winner-takes-all logic. The remaining six countries are parliamentary democracies with proportional electoral systems, or, in the case of Australia, electoral systems including strong proportional elements.

5 We put this threshold at 70, because it was close to the average lockdown stringency (72) during March and April 2020, when the first wave unrolled. We have tried other thresholds (40, 50, 60), too, but the results hardly vary at all when choosing alternative thresholds.

6 This is measured by the average lag in the country’s stringency index compared to the average of 36 EU/OECD democracies and the duration of the lag (the number of days the country is behind average stringency in all 36 countries) during the first month of the pandemic (March 2020). We combine this aspect of the ‘relative’ delay of countries compared to peers with the ‘absolute’ delay relative to their epidemic curve described in the footnote above to characterize latecomers/first movers. Essentially, a country is a latecomer if it’s behind in both relative and absolute measures, a first mover if it’s an early adopter of measures in both categories.

References

- Baker, William , and John Oneal (2001). ‘Patriotism or Opinion Leadership?: The Nature and Origins of the ‘Rally ‘Round the Flag’ Effect’, Journal of Conflict Resolution , 45:5, 661–87.

- Bartels, Larry M. (2002). ‘Beyond the Running Tally: Partisan Bias in Political Perceptions’, Political Behavior , 24:2, 117–54.

- Bisgaard, Martin (2019). ‘How Getting the Facts Right Can Fuel Partisan-Motivated Reasoning’, American Journal of Political Science , 63:4, 824–39.

- Bol, Damien , Marco Giani , André Blais , and Peter John Loewen (2021). ‘The Effect of Covid-19 Lockdowns on Political Support: Some Good News for Democracy?’, European Journal of Political Research , 60:2, 497–505.

- Brouard, Sylvain , Pavlos Vasilopoulos , and Martial Foucault (2018). ‘How Terrorism Affects Political Attitudes: France in the Aftermath of the 2015–2016 Attacks’, West European Politics , 41:5, 1073–99.

- Bullock, John G. , and Gabriel Lenz (2019). ‘Partisan Bias in Surveys’, Annual Review of Political Science , 22:1, 325–42.

- Callaghan, Karen J. , and Simo Virtanen (1993). ‘Revised Models of the ‘Rally Phenomenon’: The Case of the Carter Presidency’, The Journal of Politics , 55:3, 756–64.

- Cavari, Amnon (2019). ‘Evaluating the President on Your Priorities: Issue Priorities, Policy Performance, and Presidential Approval, 1981–2016’, Presidential Studies Quarterly , 49:4, 798–826.

- Chowanietz, Christophe (2011). ‘Rallying around the Flag? Political Parties’ Reactions to Terrorist Acts’, Party Politics , 17:5, 673–98.

- Citrin, Jack , and Laura Stoker (2018). ‘Political Trust in a Cynical Age’, Annual Review of Political Science , 21:1, 49–70.

- Clarke, Harold , and Marianne Stewart (1998). ‘The Decline of Parties in the Minds of Citizens’, Annual Review of Political Science , 1:1, 357–78.

- Dimick, Matthew , David Rueda , and Daniel Stegmueller (2018). ‘Models of Other-Regarding Preferences, Inequality, and Redistribution’, Annual Review of Political Science , 21:1, 441–60.

- Easton, David (1965). Systems Analysis of Political Life . New York: Wiley.

- Gabriel, Oscar , and Eva-Maria Trüdinger (2011). ‘Embellishing Welfare State Reforms? Political Trust and the Support for Welfare State Reforms in Germany’, German Politics , 20:2, 273–92.

- Goerres, Achim , and Stefanie Walter (2016). ‘The Political Consequences of National Crisis Management: Micro-Level Evidence from German Voters during the 2008/09 Global Economic Crisis’, German Politics , 25:1, 131–53.

- Groeling, Tim , and Matthew A. Baum (2008). ‘Crossing the Water’s Edge: Elite Rhetoric, Media Coverage, and the Rally-Round-the-Flag Phenomenon’, The Journal of Politics , 70:4, 1065–85.

- Hale, Thomas , Sam Webster, Anna Petherick, Toby Phillips , and Beatriz Kira (2020). Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Blavatnik School of Government.

- Harring, Niklas (2018). ‘Trust and State Intervention: Results from a Swedish Survey on Environmental Policy Support’, Environmental Science & Policy , 82, 1–8.

- Hetherington, Marc J. (1998). ‘The Political Relevance of Political Trust’, American Political Science Review , 92:4, 791–808.

- Hetherington, Marc J. , and Suzanne Globetti (2002). ‘Political Trust and Racial Policy Preferences’, American Journal of Political Science , 46:2, 253–75.

- Hetherington, Marc J. , and Michael Nelson (2003). ‘Anatomy of a Rally Effect: George W. Bush and the War on Terrorism’, Political Science and Politics , 36:01, 37–42.

- Highton, Benjamin (2012). ‘Updating Political Evaluations: Policy Attitudes, Partisanship, and Presidential Assessments’, Political Behavior , 34:1, 57–78.

- Holmberg, Sören (2007). ‘Partisanship Reconsidered’, in Russell J. Dalton and Hans-Dieter Klingemann (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 557–70.

- Iyengar, Shanto , Yphtach Lelkes , Matthew Levendusky , Neil Malhotra , and Sean J. Westwood (2019). ‘The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States’, Annual Review of Political Science , 22:1, 129–46.

- Jeannet, Anne-Marie , Ademmer Esther , Ruhs Martin , and Stöhr Tobias (2020). ‘A Need for Control? Political Trust and Public Preferences for Asylum and Refugee Policy’, SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3633816, Rochester: Social Science Research Network.

- Kunda, Ziva (1990). ‘The Case for Motivated Reasoning’, Psychological Bulletin , 108:3, 480–98.

- Lauka, Alban , Jennifer McCoy , and Rengin Firat (2018). ‘Mass Partisan Polarization: Measuring a Relational Concept’, American Behavioral Scientist , 62:1, 107–26.

- Leeper, Thomas J. , and Rune Slothuus (2014). ‘Political Parties, Motivated Reasoning, and Public Opinion Formation’, Political Psychology , 35:S1, 129–56.

- Levendusky, Matthew S. , and Neil Malhotra (2016). ‘(Mis)Perceptions of Partisan Polarization in the American Public’, Public Opinion Quarterly , 80:S1, 378–91.

- Milton, Lodge , and Charles S. Taber (2013). The Rationalizing Voter . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McCoy, Jennifer , and Murat Somer (2019). ‘Toward a Theory of Pernicious Polarization and How It Harms Democracies: Comparative Evidence and Possible Remedies’, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , 681:1, 234–71.

- Mueller, John E. (1970). ‘Presidential Popularity from Truman to Johnson’, American Political Science Review , 64:1, 18–34.

- Norrander, Barbara , and Clyde Wilcox (1993). ‘Rallying Around the Flag and Partisan Change: The Case of the Persian Gulf War’, Political Research Quarterly , 46:4, 759–70.

- Reeves, Andrew (2011). ‘Political Disaster: Unilateral Powers, Electoral Incentives, and Presidential Disaster Declarations’, The Journal of Politics , 73:4, 1142–51.

- Reiljan, Andres (2020). ‘“Fear and Loathing across Party Lines” (Also) in Europe: Affective Polarisation in European Party Systems’, European Journal of Political Research , 59:2, 376–96.

- Roberts, Andrew (2008). ‘Hyperaccountability: Economic Voting in Central and Eastern Europe’, Electoral Studies , 27:3, 533–46.

- Rudolph, Thomas (2009). ‘Political Trust, Ideology, and Public Support for Tax Cuts’, Public Opinion Quarterly , 73:1, 144–58.

- Rudolph, Thomas J. (2017). ‘Political Trust as a Heuristic’, in Sonja Zmerli and Tom W. G. Van Der Meer (eds.), Handbook on Political Trust . Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 197–211.

- Rudolph, Thomas J. , and Elizabeth Popp (2009). ‘Bridging the Ideological Divide: Trust and Support for Social Security Privatization’, Political Behavior , 31:3, 331–51.

- Velez, Yamil , and David Martin (2013). ‘Sandy the Rainmaker: The Electoral Impact of a Super Storm’, PS: Political Science & Politics , 46:02, 313–23.