Abstract

Media attention is an invaluable electoral asset, and structurally less media attention given to female candidates and politicians could be detrimental to women’s representation. While research has found equal amounts of coverage devoted to male and female politicians in the US and Canada, a gender gap persists in European countries. This article examines whether differences in the political position and background of men and women account for this gender gap. A computer-assisted content analysis of national dailies in six European countries during one full legislative cycle is combined with extensive background information of 3039 MPs. The results confirm that even after controlling extensively for individual differences, female parliamentarians in Europe are less visible in the news than their male counterparts.

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1988387 .

Do the media advantage male politicians by giving them more attention than their female colleagues? This is an important question, as visibility in the media is an indispensable resource for politicians to survive in the current-day mediatised political climate. Voters mostly depend on the media for their political information (Strömbäck Citation2008), they use media exposure as input for political discussions and eventually their vote (Mondak Citation1995). If journalists structurally place more attention on male politicians than female politicians, this would put women in politics at a serious disadvantage.

While research in the US and Canada shows that male and female politicians get on average equal amounts of media attention, research in European countries finds that female politicians lag substantially behind men in media visibility (van der Pas and Aaldering Citation2020). This is striking, not least considering the relatively high levels of female representation and gender equality norms in Europe. It begs the question whether European media really report less on female politicians than on men, or whether some political difference is driving this surprising visibility gap in Europe. In other words, is there gender bias in the media, or is the apparent gap in media attention spurious?

In order to answer this question, this study examines media attention to male and female politicians taking the full set of relevant political factors into account. Scholarship so far has only done this to a very limited extent, and usually in a single-country set-up. This study compares the amount of newspaper coverage of male and female parliamentarians in six European countries – Germany, Spain, France, Italy, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom – by combining a content analysis of newspaper articles during one full electoral term between 2007 and 2015 with an extensive dataset on political positions and paths to power of the legislators. It shows that even when fully controlling for the political past and present of parliamentarians, women are indeed granted less attention than men in European media.

Male and female politicians in the media

The visibility of male and female candidates and sitting politicians has been studied quite extensively since the influential research of Kahn (Citation1994, Citation1996) and Kahn and Goldenberg (Citation1991). Some empirical studies find female politicians to be more visible, some less, and many find no substantial differences (Heldman et al. Citation2005; also see Aday and Devitt Citation2001; Banwart et al. Citation2003; Bystrom et al. Citation2001; Carroll and Schreiber Citation1997; Conroy et al. Citation2015; Devitt Citation2002; Hayes and Lawless Citation2015; Jalalzai Citation2006; Smith Citation1997). Confirming this, a meta-analysis covering 66 separate studies shows that on average men and women in politics are treated with equal attention in the media (van der Pas and Aaldering Citation2020). Yet, remarkably, a robust gender gap in media to the detriment of women remains in Europe (van der Pas and Aaldering Citation2020). Most studies of European countries find that men receive more media attention (Hooghe et al. Citation2015; Lühiste and Banducci Citation2016; Midtbø Citation2011; Ross et al. Citation2013; Semetko and Boomgaarden Citation2007 (analysis of MPs; also see Vos Citation2013); O’Neill et al. Citation2016 (2012 analysis); van Aelst et al. Citation2008), and some find roughly equal attention (Dan and Iorgoveanu Citation2013; Fernandez-Garcia Citation2016; Gattermann and Vasilopoulou Citation2015; O’Neill et al. Citation2016 (analyses of 1992 and 2002); Semetko and Boomgaarden Citation2007 (analysis of Merkel and Schröder)), but the balance never strikes towards female politicians.

Why have studies found female politicians to be less visible in European news media, while elsewhere male and female politicians are equally present in the news? One explanation is spuriousness, rather than journalists treating female politicians differently because of their gender. Specifically, female politicians might feature less prominently in the news as a result of their functions and the pathways into politics they have followed. More powerful actors are granted more media attention (Bennett Citation1990), and men are overrepresented in party leadership and in more powerful positions in parliament and government (Paxton and Hughes Citation2017; see also O’Brien Citation2015). Therefore, if journalists ‘index’ by power, it results in male politicians receiving more media coverage. Similarly, previous positions can exert continuing impact. Politicians with previous high functions have a reputation among media consumers, making them attractive news sources, and also have had more time to build up connections with journalists. Accordingly, the longer duration and higher level of prior positions of male politicians could advantage their media presence, even if journalists do not differentiate on gender. In other words, it would not be journalistic gender bias, but a difference resulting from a bias in the political system (see also Lühiste and Banducci Citation2016; Vos Citation2012).

Spuriousness might explain why a gender gap is found only in Europe if it is harder in European countries to take all the relevant political factors into account. The overwhelming majority of studies outside of Europe are conducted in the US or Canada, both of which have first-past-the-post electoral systems. This system arguably leads to a juxtaposition of two candidates with comparable political experience, making extensive controls for prior positions less crucial. By contrast, a number of European countries and the European Parliament elect members through proportional representation. This is associated with a higher number of parties, which vary more in electoral strength and appeal to the media than parties in two-party systems. It also makes it pertinent to control for list position, which is usually done only minimally. Therefore, it is conceivable that the persistent gender gap in media visibility in Europe results from a greater difficulty to attain a ceteris paribus condition in the European context.

Methods

In order to test whether political factors explain the European gender gap in media visibility, newspaper coverage of MPs was tracked in Germany, Spain, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. These countries were chosen to allow the use of a rich dataset collected in the project ‘Pathways to Power: The Political Representation of Citizens of Immigrant Origin in Seven European Democracies’, which contains extensive information on individual parliamentarians (Morales et al. Citation2017). The legislative terms included are: 2009–2013 for Germany, 2008–2011 for Spain, 2007–2012 for France, 2008–2013 for Italy, 2010–2012 for the Netherlands, and 2010–2015 for the United Kingdom. These six countries include diverse electoral systems, with the mixed-member system in Germany, the two-round elections in France, single-member plurality in the UK, flexible-list proportional representation in the Netherlands, and closed-list proportional representation in Spain and Italy (André et al. Citation2016). They cover Hallin and Mancini’s (Citation2004) media systems, with the liberal model in the UK, the polarised pluralist model in Spain, France, and Italy, and the democratic corporatist model in Germany and the Netherlands.Footnote1 The geographical spread of the cases over Europe is skewed, with no Scandinavian or East European cases. However, the prior studies into gender-differentiated media attention in Europe mostly focussed on West Europe, so these countries are well suited to examine the reasons for the gender gap found earlier.

Content analysis

Media attention to individual politicians was gauged in 3–5 large daily newspapers per country. Newspapers were chosen as a medium to relate the results back to earlier studies that found a gender gap, which mostly used the same medium. Specific papers were chosen based on circulation, spread over the political spectrum, regional spread if relevant, and availability in LexisNexis. The newspapers were collected from the start date until the end date of one entire legislative term in each country. Articles were collected that broadly covered parliamentary and party politics, using country-specific search strings covering parliament-related words and political party names. For MPs who also served in government during the term or before, the corpus was extended with articles mentioning government-related words (e.g. minister, secretary, etc.). This resulted in a corpus of 207,606 newspaper articles for Germany, 309,367 for Spain, 428,488 for France, 260,458 for Italy, 42,515 for the Netherlands and 121,982 for the United Kingdom.

For each country, the corpus was searched for the first name and last name of all parliamentarians, excluding those who served for less than a year. For German MPs, both English and German name spellings were searched; for Spanish MPs up to two alternative versions of their name were searched, as their names are often abbreviated. This count of articles per person over all included newspapers of the country is the dependent variable. A list of included newspapers, the search strings used and the reliability measures for the content analysis can be found in Online Appendices A, B and C.

Parliamentarians’ data

Prior experience is captured by a dummy indicating whether the MP served their first term, the number of years the MP had served in that chamber at inauguration of the term, the highest position the MP had so far fulfilled in the party, and whether the MP had any prior experience in local politics, regional politics, national government or regional government. Among current political positions are variables regarding the position on the list through which the parliamentarian was elected in those countries using list systems, whether the MP served as a (shadow) cabinet minister in the national government during the term, and whether the MP was part of the parliamentary party leadership team or is a party leader. Finally, the number of parliamentary committees the MP took a seat on is included. The individual characteristics of parliamentarians included in the controls are age in years and the highest completed educational level. Party size is measured as the number of MPs starting the term at inauguration for the party. Government participation by the party of the MP is indicated in a dummy. More information and descriptive statistics of the control variables is in Online Appendix D.

Analytical strategy

The dependent variable is the total number of articles in which an individual parliamentarian was mentioned during one entire legislative period. Because this is an over-dispersed count variable, negative binomial regression was used (Hilbe Citation2011; Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal Citation2005). Separate models were run for every country to allow for country-specific effects of the control variables.

Results

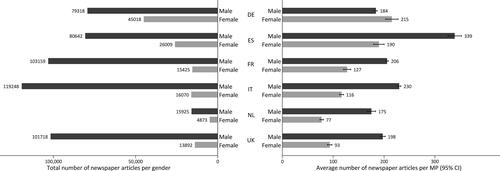

The left-hand side of displays the total number of newspaper articles about MPs per gender. While these raw differences in newspaper visibility cannot tell whether reporting is biased, they do paint a picture of what media consumers get to see, and that is an overwhelmingly masculine picture of parliamentary politics. This is perhaps not surprising, given that in all six countries men outnumber women in parliament. To account for this, the right-hand panel displays the average per person visibility of parliamentarians. In all countries except Germany, on average there are more articles written about an individual male MP than a female MP during the legislative term. Only in Germany are women slightly more visible per person than men, but this is driven entirely by the understandably high visibility of Angela Merkel. Excluding Merkel, female MPs feature in 130 articles per person during the term, so markedly less than the average of 184 for men. In the rest of the countries, male MPs appear in roughly twice as many newspaper articles per person as their female colleagues.

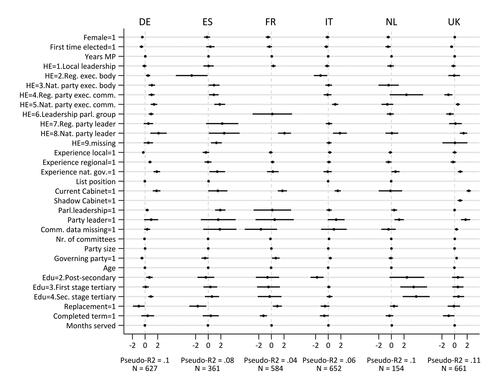

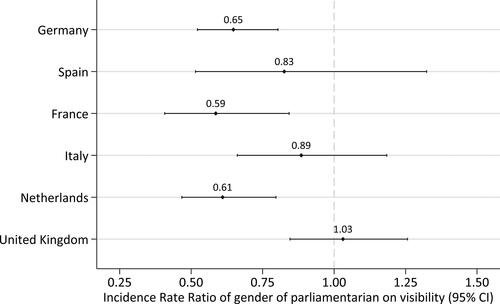

Is there a gender difference in newspaper visibility if we account for prior experience and current positions? displays the coefficients of the full models explaining visibility, while focusses on the effect of parliamentarians’ gender from these models, expressed in Incidence Rate Ratios (IRR). Remarkably, in the United Kingdom, the entire gender gap in visibility can be accounted for by the political factors included. The most important variable in closing the initial gap is length of tenure as an MP, and second, government and leadership positions. Spain and Italy still show a difference in visibility between male and female politicians, but the estimates are very uncertain and not statistically significant. By contrast, in France, the gap is unaffected by the political control variables, as female MPs still appear in just over half as many newspaper articles as men. Concretely, the model predicts that an average male MP is typically mentioned in 113 articles in France, while a comparable female MP is mentioned in only 66. In Germany and the Netherlands, part of the initial difference in visibility can be explained by the political standing and background of MPs, but still a substantial gender gap remains, with IRRs of 0.65 and 0.63 respectively. The prediction is that in Germany an average male MP features in 63 articles per term and a comparable female MP in 41; in the Netherlands average male MPs can expect 93 newspaper articles and female MPs only 57. In summary, therefore, in half the cases political factors are unable to account for the difference in media visibility between male and female parliamentarians, while the UK presents the only clear case of equal media attention to male and female MPs.

The results are robust to a number of alternative specifications, which are detailed in Online Appendix E. As the main analysis aims to be inclusive of any alternative explanation of media visibility, the high number of variables creates some multicollinearity, but leaving out variables with inflation factors over 2.5 gives substantively the same results on the effect of gender. In addition, models with party dummies, models excluding the coverage of the first three and last six months of the term, separate models per election type in Germany’s mixed member system, and different dependent variables all lead to the same conclusions.

Discussion

The results leave us with a puzzle: Why do the media in some countries pay less attention to female politicians while in other countries attention is equal? The solution to this puzzle may be sought in two areas (see also Rodelo Citation2016). The first is context-specific journalistic norms and practices. Notably, the UK is the only country in this study clearly displaying no gender bias and it is also the only country falling in the liberal media system (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004). In the liberal system, which is shared by the US, journalism is more professionalised, which conceivably entails a stronger emphasis on non-sexist reporting. Beyond the media systems, other differences in the journalistic norms of these countries may matter. For instance, media companies in the US and the UK have adopted gender equity policies at higher rates (Byerly Citation2011), perhaps signalling a greater awareness gender biases that may translate into more equitable reporting.

The second explanation for real gender differences in media attention in Europe is the behaviour of politicians towards the media in these electoral systems. Legislators pursue more personalised campaigns in single-member plurality systems and more party-focussed campaigns in proportional list systems (André et al. Citation2016). In a personalised electoral context, every politician is incentivised to maintain media relations, while in a party-focussed electoral context, legislators can divide the labour within the party, with some specialising in media relations and others in other activities (e.g. see Gattermann and Vasilopoulou Citation2015). If such a division of labour is partly based on legislators’ gender, it could explain the men being more visible in the media in party-centred countries. Both explanations, however, are merely speculative. The aim of this study was to exclude political factors as an explanation, it is now up to further research to investigate these two mechanisms, so we can understand why female politicians get less media attention in these countries.

Conclusion

Personal media attention is an important asset for political actors and is often necessary to achieve re-election or political advancement. Previous research has shown that in Canada and the US, men and women in politics receive equal amounts of journalistic attention, while in European countries female politicians still lag behind men. This note has examined whether political differences between male and female politicians are responsible for the gender gap invisibility. The conclusion is that they are not, as even politicians with similar pasts and equal positions differ by gender in levels of media attention in Germany, France and the Netherlands. Thus, while there is some justified optimism in the literature about the visibility gender gap among politicians disappearing in the US, the optimism is not warranted for many other countries. Beyond the amount of attention, scholars have found gender differences in the content of coverage of politicians to women’s detriment throughout the world (Van der Pas and Aaldering Citation2020). Accordingly, media coverage likely affects opportunities for women to reach the highest echelons of politics, and further compounds an already masculinised image of politics.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (15.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.3 MB)Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the two reviewers, and in addition João Areal for excellent research assistance, Loes Aaldering and Katjana Gattermann for their help developing search strings and for their feedback, the participants and discussants at the ECPG conference in 2019 for their feedback, and the contributors to the Pathways consortium, formed by the University of Amsterdam (Jean Tillie), the University of Bamberg (Thomas Saalfeld), the University of Leicester (Laura Morales), and the CEVIPOF-Sciences Po Paris (Manlio Cinalli).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Daphne J. van der Pas

Daphne J. van der Pas is Assistant Professor at the Political Science Department, University of Amsterdam. Her research focusses on democratic representation, gender and political communication. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 In addition, the selection includes different party systems in terms of the effective number of parties in the legislature (about 2.5 in Spain, France and the UK, and 3 to about 7 in Italy, Germany and the Netherlands) and in terms of polarisation (high in Spain, France, Italy and the Netherlands, medium in Germany and low in the UK) (Dalton Citation2008; Gallagher and Mitchell Citation2006; Hallin and Mancini Citation2004).

References

- Aday, Sean, and James Devitt (2001). ‘Style over Substance: Newspaper Coverage of Elizabeth Dole’s Presidential Bid’, Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 6:2, 52–73.

- André, Audrey, Sam Depauw, and Shane Martin (2016). ‘The Classification of Electoral Systems: Bringing Legislators Back In’, Electoral Studies, 42, 42–53.

- Banwart, Mary Christine, Dianne G. Bystrom, and Terry A. Robertson (2003). ‘From the Primary to the General: A Comparative Analysis of Candidate Media Coverage in Mixed-Gender 2000 Races for Governor and U.S. Senate’, American Behavioral Scientist, 46:5, 658–76.

- Bennett, W. Lance (1990). ‘Toward a Theory of Press-State Relations in the United States’, Journal of Communication, 40:2, 103–27.

- Byerly, Carolyn M. (2011). ‘Global Report on the Status of Women in the News Media’, Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://www.iwmf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/IWMF-Global-Report.pdf

- Bystrom, Dianne G., Terry A. Robertson, and Mary Christine Banwart (2001). ‘Framing the Fight: An Analysis of Media Coverage of Female and Male Candidates in Primary Races for Governor and U.S. Senate in 2000’, American Behavioral Scientist, 44:12, 1999–2013.

- Carroll, Susan J., and Ronnee Schreiber (1997). ‘Media Coverage of Women in the 103rd Congress’, in Pippa Norris (ed.), Women, Media, and Politics. New York: Oxford University Press, 131–48.

- Conroy, Meredith, Sarah Oliver, Ian Breckenridge-Jackson, and Caroline Heldman (2015). ‘From Ferraro to Palin: Sexism in Coverage of Vice Presidential Candidates in Old and New Media’, Politics, Groups, and Identities, 3:4, 573–91.

- Dalton, Russell J. (2008). ‘The Quantity and the Quality of Party Systems: Party System Polarization, Its Measurement, and Its Consequences’, Comparative Political Studies, 41:7, 899–920.

- Dan, Viorela, and Aurora Iorgoveanu (2013). ‘Still on the Beaten Path: How Gender Impacted the Coverage of Male and Female Romanian Candidates for European Office’, The International Journal of Press/Politics, 18:2, 208–33.

- Devitt, James (2002). ‘Framing Gender on the Campaign Trail: Female Gubernatorial Candidates and the Press’, Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 79:2, 445–63.

- Fernandez-Garcia, Núria (2016). ‘Framing Gender and Women Politicians Representation: Print Media Coverage of Spanish Women Ministers’, in Carla Cerqueira, Rosa Cabecinhas, and Sara I. Magalhães (eds.), Gender in Focus: (New) Trends in Media. Braga: CECS, 141–60.

- Gallagher, Michael, and Paul Mitchell (eds.) (2006). The Politics of Electoral Systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gattermann, Katjana, and Sofia Vasilopoulou (2015). ‘Absent yet Popular? Explaining News Visibility of Members of the European Parliament’, European Journal of Political Research, 54:1, 121–40.

- Hallin, Daniel C., and Paolo Mancini (2004). Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hayes, Danny, and Jennifer L. Lawless (2015). ‘A Non-Gendered Lens? Media, Voters, and Female Candidates in Contemporary Congressional Elections’, Perspectives on Politics, 13:1, 95–118.

- Heldman, Caroline, Susan J. Carroll, and Stephanie Olson (2005). ‘“She Brought Only a Skirt”: Print Media Coverage of Elizabeth Dole’s Bid for the Republican Presidential Nomination’, Political Communication, 22:3, 315–35.

- Hilbe, Joseph M. (2011). Negative Binomial Regression. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hooghe, Marc, Laura Jacobs, and Ellen Claes (2015). ‘Enduring Gender Bias in Reporting on Political Elite Positions: Media Coverage of Female MPs in Belgian News Broadcasts (2003–2011)’, The International Journal of Press/Politics, 20:4, 395–414.

- Jalalzai, Farida (2006). ‘Women Candidates and the Media: 1992–2000 Elections’, Politics & Policy, 34:3, 606–33.

- Kahn, Kim Fridkin (1994). ‘The Distorted Mirror: Press Coverage of Women Candidates for Statewide Office’, The Journal of Politics, 56:1, 154–73.

- Kahn, Kim Fridkin (1996). The Political Consequences of Being a Woman: How Stereotypes Influence the Conduct and Consequences of Political Campaigns. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Kahn, Kim Fridkin, and Edie N. Goldenberg (1991). ‘Women Candidates in the News: An Examination of Gender Differences in U.S. Senate Campaign Coverage’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 55:2, 180–99.

- Lühiste, Maarja, and Susan Banducci (2016). ‘Invisible Women? Comparing Candidates’ News Coverage in Europe’, Politics & Gender, 12:02, 223–53.

- Midtbø, Tor (2011). ‘Explaining Media Attention for Norwegian MPs: A New Modelling Approach’, Scandinavian Political Studies, 34:3, 226–49.

- Mondak, Jeffery J. (1995). ‘Media Exposure and Political Discussion in U.S. Elections’, Journal of Politics, 57:1, 62–85.

- Morales, Laura, et al. (2017). ‘Codebook and Data Collection Guidelines of Work Package 1 on Descriptive Political Representation in Regional Parliaments of the Project Pathways to Power’, V1. Retrieved from https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KZMOAM.

- O’Brien, Diana Z. (2015). ‘Rising to the Top: Gender, Political Performance, and Party Leadership in Parliamentary Democracies’, American Journal of Political Science, 59:4, 1022–39.

- O’Neill, Deirdre, Heather Savigny, and Victoria Cann (2016). ‘Women Politicians in the UK Press: Not Seen and Not Heard?’, Feminist Media Studies, 16:2, 293–307.

- Paxton, Pamela M. Mari, and Melanie M. Hughes (2017). Women, Politics, and Power: A Global Perspective. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: CQ Press.

- Rabe-Hesketh, Sophia, and Anders Skrondal (2005). Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata. 2nd ed. College Station, TX: Stata Press.

- Rodelo, Frida V. (2016). ‘Gender Disparities in the Media Coverage of Local Electoral Campaigns in Mexico’, Cuadernos.info, 39, 87–99.

- Ross, Karen, Elizabeth Evans, Lisa Harrison, Mary Shears, and Khursheed Wadia (2013). ‘The Gender of News and News of Gender a Study of Sex, Politics, and Press Coverage of the 2010 British General Election’, The International Journal of Press/Politics, 18:1, 3–20.

- Semetko, Holli A., and Hajo G. Boomgaarden (2007). ‘Reporting Germany’s 2005 Bundestag Election Campaign: Was Gender an Issue?’, Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 12:4, 154–71.

- Smith, Kevin B. (1997). ‘When All’s Fair: Signs of Parity in Media Coverage of Female Candidates’, Political Communication, 14:1, 71–82.

- Strömbäck, Jesper (2008). ‘Four Phases of Mediatization: An Analysis of the Mediatization of Politics’, The International Journal of Press/Politics, 13:3, 228–46.

- van Aelst, Peter, Bart Maddens, Jo Noppe, and Stefaan Fiers (2008). ‘Politicians in the News: Media or Party Logic? Media Attention and Electoral Success in the Belgian Election Campaign of 2003’, European Journal of Communication, 23:2, 193–210.

- van der Pas, Daphne Joanna, and Loes Aaldering (2020). ‘Gender Differences in Political Media Coverage: A Meta-Analysis and Review’, Journal of Communication, 70:1, 114–43.

- Vos, Debby (2012). ‘Is gender bias een mythe? Op zoek naar verklaringen voor de beperkte aanwezigheid van vrouwelijke politici in het Vlaamse televisienieuws’, Res Publica, 54:2, 193–217.

- Vos, Debby (2013). ‘The Vertical Glass Ceiling: Explaining Female Politicians’ Underrepresentation in Television News’, Communications, 38:4, 389–410.