Abstract

Do nativists differ from other citizens in their attitudes towards democracy? In this article it is demonstrated that nativism goes hand in hand with preferences for a type of democracy where the interests of the natives should prevail, even at the cost of diminished minority rights, checks and balances, and other constraints on executive power. Liberal representative democracy is not for nativists. It is also shown that nativists seem to believe that the end justifies the means when it comes to different forms of decision making, and that this opportunistic trait usually translates into support for more direct democracy and scepticism towards representative democracy, because nativists tend to believe that they are in the majority (even if they are not). This article concludes that this tendency may in fact be a blessing of sorts, as it keeps nativists from supporting alternatives to democracy.

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.2007459 .

In recent decades, parties and politicians mobilising on a nativist agenda have repeatedly scored electoral successes and have, in several cases, also gained access to government in several countries, predominantly in Europe (Harteveld et al. Citation2021). A growing literature has tried to establish if these electoral triumphs threaten liberal representative democracy, focussing especially on the populist ideology that often accompanies nativism (e.g. Abts and Rummens Citation2007; Galston Citation2018; Kaltwasser Citation2012; Mudde Citation2007; Müller Citation2016). In this article we shift the focus from populism to nativism, and from parties and politicians to citizens, and ask whether nativists differ from other citizens in their attitudes to democracy (cf. Bartels Citation2020).Footnote1 More specifically, we do this by examining the tension between nativism and liberal democracy along two dimensions. First, we examine the ideational tension between nativism and majority-constraining institutions of liberal democracy (e.g. protection of minority rights and judicial control). Secondly, we investigate the relationship between nativism and democracy in a more electoral sense by examining nativists’ support for alternatives to representative democracy (e.g. support for direct democracy and strong leaders).

Having its origins in analyses of anti-immigrant sentiments in North America, the concept of ‘nativism’ has frequently been used to understand the success of populist radical right parties and leaders (Betz Citation2019; Guia Citation2016; Mudde Citation2007). Within this research, nativism has been conceptualised as an ‘ideology which holds that states should be inhabited exclusively by members of the native group (‘the nation’) and that non-native elements (persons and ideas) are fundamentally threating the homogenous nation state’ (Mudde Citation2010: 1173).

We contend that this ideal of a homogenous nation state embodied in the ‘interest of the native people’ is at odds with the fundamentals of liberal representative democracy, in which the protection of minority rights, civil liberties and checks and balances on the executive are defining elements (Galston Citation2018). This is primarily because nativists deny fundamental value conflicts within the native people. Morally relevant minorities do simply not exist.

We also argue, and empirically demonstrate, that nativists are more likely than others to believe themselves to be in the majority among those who matters politically. The reason is that they do not see members of ethnic minorities and foreigners as part of the people and often see natives with ‘foreign’ ideas as traitors – and hence not worthy of a voice (Guia Citation2016). This tendency to conflate their own opinions with that of the people (because those who do not agree are seen as traitors) might also lead them to support alternatives to representative liberal democracy if the representatives do not deliver the desired nativist policies. Thus, a nativist worldview should imply a sceptical view of the foundations of liberal representative democracy, and a more positive outlook on ‘unconstrained’ forms of government that emphasise majority rule and either more decision-making directly by the people (if it understands what its interests are) or more power for a strong leader who implements policies that are in the interest of the people (if elites and parts of the people do not realise what is in the people’s interest). For nativists democracy is just one of several strategies to implement policies that favour the native people. Hence the paradox that nativist voters are both more supportive of direct democracy and strong leaders.

Surprisingly little empirical research has been devoted to the relationship between nativism and attitudes to democracy (though see Bartels Citation2020 for an exception). In a first attempt to fill this gap in the research, we investigate nativists’ conceptions of democracy using a wide variety of datasets and indicators. The empirical analysis is divided into four separate, but interrelated, studies. In the first study we use the sixth round of the European Social Survey (ESS) to investigate nativists’ understanding of liberal democracy by assessing perceptions of how important constraints on majority rule and protection of minority rights are for democracy in general. The second study uses data from the fifth module of the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) to examine nativists’ support for ‘unconstrained’ forms of political decision-making. The third study uses the 2017 European Values Study (EVS) to study whether nativists support strong leaders. The fourth study explores data from the Norwegian Citizen Panel (NCP) to study if nativists are more likely to believe themselves to be in the majority (regarding views on immigration policy), and whether this belief matters for their principled support for direct democracy.

Nativism and notions of democracy

The tension between populism and liberal representative democracy has been thoroughly examined and debated both within and outside academia (e.g. Canovan Citation1999; Kriesi Citation2014; Moffitt Citation2020; Müller Citation2016; Taggart Citation2000). However, much less attention has been devoted to the relationship between nativism and liberal representative democracy. In the following, we discuss what nativism’s horizontal and exclusionary definition of the people should imply for a nativist vision of democracy.

While the nativist utopia is a monocultural state, most contemporary parties with a nativist agenda – who represent the most elaborate versions of contemporary nativist ideology – are rather striving for a more attainable ‘ethnocracy’ (Golder Citation2016: 480). In such a polity, ethnic minorities may be accommodated within the state, but there can be only one official national culture (Mudde Citation2007: 144). And immigrants should assimilate to that culture. So, although there is a strong desire to reduce immigration among parties based on the nativist ideology, today only a few ‘advocate a totally closed conception of the nation either ethnically or in terms of new immigration’ (Eatwell and Goodwin Citation2018: 76). Rather, contemporary nativist parties’ policy platforms emphasise stricter immigration and asylum policies, protection of the native population’s economic interests, welfare chauvinism, and a rejection of multi-culturalism (Betz Citation2019).

The struggle for a homogenous dominant national culture free from interference from outsiders has not always been seen to stand in conflict with liberal representative democracy. As noted by Ghia Nodia (Citation1992: 9), struggles for national self-determination and demands for democracy have often gone together historically:

[I]n emergent democracies, movements for democracy and movements for independence are often one and the same. Both are acting in the name of ‘self-determination’: ‘We the People’ (i.e. the nation) will decide our own fate; we will observe only those rules that we ourselves set up; and we will allow nobody – whether absolute monarch, usurper, or foreign power – to rule without consent.

We do not deny that nationalist feelings may motivate people to demand democracy (self-determination), and thus further democratisation efforts, especially, in a situation where the nation lives in a state ruled by a ‘foreign’ power. Such feelings were definitely important for motivating nationalistic demands for democracy in the Habsburg, Ottoman and Russian empires in the 19th century and they played a central role in the revolutions against communist rule in Central and Eastern Europe. Neither do we deny that it may be easier to build stable democracies when ‘the people’ share a national identity and is not split between different nations (Horowitz Citation1993), even though the empirical evidence for this is scant (Teorell 2010: 39–53). However, we do contend that there is an intrinsic conflict between a nationalist worldview – in its ethno-nationalist, or nativist, version – and liberal representative democracy at the ideational level, which may undermine support for liberal representative democracy, especially after it has been established.

Nativism builds on the assumption that there is one native people, whose interests should be prioritised over those of foreigners and minorities. Every strand of nativism thus has a conception of who belongs and who does not belong to the people (Betz Citation2019). Although nativists can admit that natives may have different preferences in a trivial sense, they usually describe the people as a homogenous entity, with a shared culture, values, and interests, which distinguishes it from others (foreigners and ethnic minorities). This is especially true today when nativism is increasingly defined in civic terms, and foreigners are described as threatening core values of the native identity (Guia Citation2016). It is from this homogenous entity – the native people, its culture, its values, and its interest – that legitimate political and moral authority stems. Fundamental value conflicts and conflicts of interests within the native people are denied. Trivial differences in preferences may be allowed, but they must not get out of hand and threaten the unity of the people. Foreigners can, for example, only be tolerated if they assimilate fully to the majority culture and become part of the native people. And natives who threaten the interests and unity of the native people by adopting ‘foreign ideas’ are often seen as ‘traitors’ (Guia Citation2016).

The degree of ‘trivial’ differences that are allowed among natives do of course vary with how extreme the nativist ideology is. But it is obvious that the very idea of a homogenous nation with common interests reduces the acceptable level of preference heterogeneity within the nation. This is especially true for issues that are important for nativists, such as immigration and the protection of the native people’s interests.

Nativism in relation to populism

The fact that nativism constitutes a radical form of nationalism (Mudde Citation2007) is relevant for distinguishing populism from nativism. The most important difference between populism and nativism relates to the question of representation, or rather the question of ‘who’ is represented. While populism offers a Manichaean moral worldview that claims to represent ‘the people’ (in general) against the interests of ‘the elite’ (Mudde Citation2007; Müller Citation2016), nativism seeks to represent the interests of the nation and ‘the natives’ against the interests of those who are not rightful members of the nation, i.e. immigrants, members of ethnic minorities, and other out-groups. Indeed, some researchers go as far as arguing that ‘natives’ who do not share the perceived ‘native values’ may themselves be perceived as foreign by nativists: ‘[S]ome ‘natives’ are actually considered foreign, culturally alien. In nativist discourses, foreignness is not only imputed to foreigners’ (Kesic and Duyvendak Citation2019).

Thus, the central concern of populism is the vertical and down-up relationship between the ‘pure’ people and the ‘corrupt’ elite. Nativism, on the other hand, is primarily occupied with the antagonism between natives and non-natives. It thus comprises a ‘horizontal, in-out directionality whereby the distinction between those who belong to ‘the nation’ and those who do not is based on membership or identity constructed around a shared sense of territory, time and space’ (Moffitt Citation2020: 35; see also Betz Citation2019: 132; Rooduijn et al. Citation2021: 2). This distinguishing identity can be ethnic. But nativism can also be of the civic kind, as when nativist politicians stress that (especially Muslim) immigrants constitute a threat to the nation’s secular culture, for example tolerance of homosexuals and support for gender equality (Berntzen Citation2020; Guia Citation2016). There is no necessary conflict between the people and the elite according to nativism; whether there is a conflict depends on the elite’s nativist inclinations.

In terms of actual politics, the formula of combining nativism and populism has shown to be the most successful in Europe. Perhaps because nativism provides an answer to the question of who ‘the people’ are – a question that populism does not answer on its own (Ivarsflaten et al. Citation2020). However, we contend that it is important to distinguish nativism and populism. Populist parties are not always nativist, and nativist parties and movements are not always populist. Political parties that mix populism with other ideologies have gained strong electoral support in recent years. In Spain and Greece, Podemos and Syriza have successfully combined radical left-wing ideology with anti-elitism and a more inclusionary type of populism (Font et al. Citation2021). There are also non-populist nativist parties that are more authoritarian than populist in character. Such parties were common in the past. The NSDAP is a – admittedly radical – case in point. But similar extreme right parties are still around, as illustrated by Greece’s Golden Dawn and Hungary’s Jobbik, even though they are less successful than their more populist counterparts. Indeed, it has been argued that nativism is the only ideological feature that radical right parties have in common (Ivarsflaten Citation2008).

There are also examples of less extreme non-populist parties with a nativist agenda that support representative democracy, even if they are critical of the liberal features of democracy. A case in point are the Danish mainstream parties Venstre (Denmark’s Liberal Party) and Socialdemokratiet (the Social Democrats), which in recent years have adopted what some observers call a ‘far-right’ policy on immigration (Poulsen Citation2021). Although both parties stand strongly committed to Danish representative democracy, they advocate assimilatory policies that can be described as illiberal. For example, both parties have suggested that new citizens should be forced to shake hands with the opposite sex to exclude conservative Muslims, who find such customs offensive, from Danish citizenship.

Nativism and democracy

But how does it come that nativism couples itself with such different outlooks on the political system? Populism with its critique against elites and demands for influence by the people does not at first sight go together with demands for strong authoritarian leaders and parties that do not have to bother with the people’s representatives. We argue that the reason for this ambiguity is that nativism is opportunistic when it comes to many of the fundaments of the political system. This argument echoes Rooduijn et al. (Citation2021), who suggest that radical-right parties (no doubt the most eloquent proponents of nativism) may be using populism as an ‘innocuous stand-in for their core nativist messages’ for strategic rather than ideological reasons. What really matters is whether or not the system protects the native people’s culture, values, and interests. If elites are seen as traitors to a nativist minded people, because they implement liberal immigration laws, nativism goes well together with populism. If instead large parts of the native people act like traitors to the native culture, values and interest and want liberal immigration laws, a strong leader – or other authoritarian alternatives – may very well be preferable to populism. In short, we expect people with nativist attitudes to harbour a vision of politics as an instrument which first and foremost should pursue the interests of the native people.

In part this may reflect a general inclination among humans to favour decision making processes that produce favourable outcomes. Experimental research has shown that perceptions of procedural fairness are endogenous to outcome favorability, i.e. people who receive an unfavourable outcome tend to perceive an objective process as less fair than those who receive a favourable outcome (Doherty and Wolak Citation2012; Esaiasson et al. Citation2019; Skitka Citation2002). People do, for example, tend to be more supportive of direct democratic initiatives, such as referendums, if they believe that their own preferences align with the preferences of the majority (Werner Citation2020; Landwehr and Harms 2020). However, this tendency may have particularly strong implications for nativists’ support for direct democratic forms of decision making, because they exclude foreigners, minorities and ‘traitors’ from the morally relevant nation. We argue that this exclusionary trait makes nativists more prone to believe they are in the majority among the (morally relevant) people, and therefore more likely to support direct democracy when the liberal representative system does not deliver the policies they want.

However, if the native people consistently vote against nativists policies, nativists may instead turn to more authoritarian political alternatives. Therefore, we argue that support for liberal representative democracy will in general will be lower among nativists, even though support for specific alternative forms of decision-making will vary with the nativists’ worldview (i.e. on whether they believe that elites, leaders, and the people strive for the native people’s interests or not).

We also argue that the strong focus on the native people’s interests in almost all circumstances is likely to lead to scepticism towards some of the main institutions of liberal representative democracy. On the most general level, we expect that people with strong nativist attitudes will reject pluralism, protection of minority rights, civil liberties and checks and balances on the executive, as such institutions are anathema to the idea of value and interest homogeneity. From these two overarching hypotheses we derive seven specific and testable sub-hypotheses detailed below.

Hypotheses

Connecting our theoretical argument about a positive relationship between nativism and unconstrained forms of decision making to perceptions of democracy, it follows that nativists should be reluctant to grant minorities or counter-majoritarian institutions the right to override the interests of the (native) majority, which is a fundamental element of liberal democracy. Indeed, nativists may even perceive such institutions to be harmful to democracy, as the very idea of morally relevant minorities within the native people is strange for nativists. Hence,

H1. Nativists are less likely than non-nativists to perceive institutions that constrain majority rule and protect the right of minorities as important for democracy in general.

This mindset should also reflect itself in their support for ‘unconstrained’ forms of decision-making. Nativists’ reluctance towards minority rights and judicial control should logically be translated into a preference for decision-making based on the will of the majority, as the morally relevant ‘people’ is the natives. Hence,

H2. Nativists are more likely than non-nativists to support unrestricted majority rule without provisions for minority rights.

In a time of globalisation and increasing migration, re-delegating political power from political representatives to the people could arguably also come across as very attractive to people with nativist attitudes. For a nativist who perceives immigration to be a threat and who believes that the native people (i.e. the majority) share his/her views, representative liberal democracy is likely to be perceived as a sub-optimal, or even an unfair, political system if the elected representatives implement liberal immigration policies. With a few exceptions, nativists have also been on the losing side of politics in most western countries in the last decades, as immigration has continued, and immigrant population have continued to grow. Although they sometimes have had temporary success in stemming this development, populations in all western countries have become more heterogenous since the Second World War.Footnote2 Earlier research has generated ample empirical evidence of a negative relationship between anti-immigration attitudes and political and institutional trust: People perceiving immigration as a threat demonstrate significantly lower levels of trust in core democratic political institutions and politicians (McLaren Citation2012; Citation2015). The strong association between nativist attitudes and political discontent has been interpreted as evidence that nativists feel betrayed by political elites, especially in countries with a longstanding history of immigration (McLaren Citation2012, Citation2015). And research shows that, in practice, direct democracy leads to more nativist policy outcomes that hurt immigrant minorities – at least in Switzerland (Hainmueller and Hangartner Citation2019). Hence,

H3. Nativists are more likely than non-nativist to support decision-making directly by the people instead of politicians.

Delegating power to the people is, however, only one way of circumventing representatives who do no act in the interest of the people. A strong leader who disregards political elites and institutions intended to counter-balance executive power may also be seen as an attractive alternative for discontented nativists. At least when the leader is seen as acting in the interest of the nation, as Trump pretended to do in the US (cf. Bartels Citation2020), and/or in situations when the people vote wrongly (i.e. on non-nativist politicians). Hence,

H4. Nativists are more likely than non-nativists to support a strong leader even if s/he sidesteps fundamental principles of liberal democracy.

Of course, the last two hypotheses are contingent on the assumptions that nativists believe themselves to be in the majority (on immigration policy) and that elites do not listen to the will of the majority. We put the first of these assumptions to the test:

H5. Nativists are more prone than non-nativists to believe themselves to be in the majority (on immigration policy).

The hypotheses also build on the assumption that nativists’ support for direct democracy is opportunistic and contingent on their belief that they are in the majority (on immigration policy) and that political elites are of a different opinion. Hence,

H6. Nativists are more supportive of direct democratic decision-making if they believe themselves to be in majority.

H7. Nativists are less supportive of direct democratic decision-making if they believe politicians to have the same opinions (on immigration policy) as themselves.

(The lack of) earlier research on nativism and democracy

Empirical research on the relationship between nativism and perceptions of democracy is scarce but the results from a few contributions indeed suggest that nativist attitudes have important consequences for attitudes to democracy. In an early study, Watts and Feldman (Citation2001) demonstrate that nativist attitudes tend to be strongly related to a ‘defensive’ model of democracy, which they describe as ‘illiberal and exclusionary – that is, democratic in form but illiberal in spirit’ (2001: 658). However, the fact that the study’s sample consists of Japanese students implies a great deal of uncertainty regarding external validity and generalisability of the findings, in particular to European democracies. In a more recent study of populist attitudes and conceptions of democratic decision-making in Austria and Germany, Heinisch and Wegscheider (Citation2020) find nativist attitudes to be positively associated with a preference for majoritarian democracy (in both countries).Footnote3 In Germany, people with nativist views are also more likely to reject ‘trusteeship democracy’ (i.e. representative democracy), but not in Austria.

Drawing on recent survey data from the US, Larry Bartels (Citation2020) demonstrates that ethnic antagonism (hostility towards immigrants and ethnic minorities) is a strong predictor of antidemocratic sentiments among Republicans, including support for strong leaders and the use of force to save the traditional way of life. However, Bartels is reluctant to say that ethnic antagonism always erodes public commitment to democracy, as the US situation is rather unique as ‘one of the most political salient features of the contemporary United States is the looming demographic transition from a majority-White to a “majority-minority” country’ (Bartels Citation2020). Bartels may be right, but we suspect the negative relationship between nativism and commitment to democracy he finds in the US to be a more widespread phenomenon. Especially given that much of the world – in particular Western Europe – has experienced large scale immigration and demographic change in recent years. We therefore go on and test whether the proposed theoretical tensions between nativism and liberal representative democracy exists also in other countries, using high quality comparative data from a wide variety of democracies.

Empirical analysis

The empirical analysis consists of four separate but interrelated studies, based on four different survey data sources. In the first three studies – testing the first four hypotheses – the empirical strategy is to regress perceptions of democracy on nativism. We start all analyses with a bivariate OLS model with an index of nativism as the independent variable. The construction of the indices is described in the Online Appendices. In a second step, we introduce a battery of potential confounders. In the main models we aim to separate the effects of nativism from populism and authoritarianism. All models include country dummies. In the fourth study (H5-7) we examine beliefs about public and elite opinion and the interaction between those beliefs and nativism. The main models are presented graphically in the main text. The full regression models can be found in Online Appendix A.

Study 1: Nativism and the perceived importance of majority constraints for democracy

In our first study, we investigate nativists’ notions of democracy using the European Social Survey (ESS). We use two items from the 6th round of the ESS to measure how important respondents believe executive constraints are for democracy in general. Specifically, the questions ask how important (on a scale from 0 to 10) it is that: ‘The rights of minority groups are protected’, and that ‘The courts are able to stop the government acting beyond its authority’. It should be noted that these items tap public perceptions of how important these elements are for democracy in general rather than respondents’ own opinions about them. However, as argued above we believe that nativists do not think that constraints on the majority’s will are part of democracy, but rather impediments to it (H1).

In order to measure nativist attitudes, we draw on earlier studies of nativism (Ivarsflaten Citation2008; Rydgren Citation2008; Zhao Citation2019) and construct an index of nativism from three items that tap attitudes towards immigrants, as the perceived threat from immigrants is at the heart of contemporary definitions of nativism (e.g. Betz Citation2019; Guia Citation2016; Kesic and Duyvendak Citation2019). The index varies from 0 to 10 (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85). Higher scores denote stronger anti-immigration sentiments. The construction of the index is presented in Online Appendix B1.

In order to examine our hypotheses, we regress perceptions of the importance of minority rights and judicial control on nativism. To separate the effect of nativism from populism and authoritarianism we include measures for populist radical right voteFootnote4 and authoritarian values.Footnote5 To make sure that the found associations are not confounded by other factors we also include several variables that have been shown in previous research to be associated with perceptions of democracy: Satisfaction with democracy, political interest, education, age, gender, and employment status.

Results

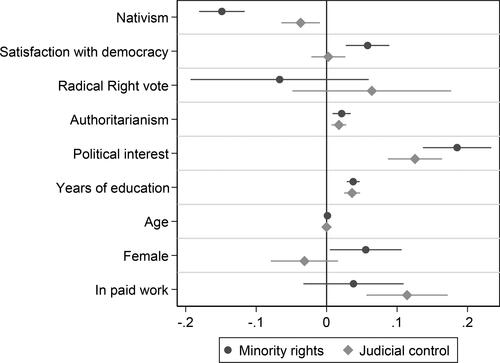

Do nativists have different opinions about how important constraints on the majority’s will are for democracy? displays a strong association between nativism and perceptions of the importance of minority rights. Extreme nativists (scoring 10 on the nativism index) are about 1.5 units less likely than extreme non-nativists to perceive the protection of minority rights to be important for democracy on the 0 to 10 scale of the dependent variable.

Figure 1. Nativism and perceived importance of executive constraints and minority rights, ESS (OLS with country clustered standard errors). Comment: Regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals. 24 countries are included in the analysis. Country dummies are included but not shown. The graph is based on models 3 and 6 in Table A2. Descriptive statistics can be found in Table A3.

The effect on the perceived importance of courts being able to stop the government acting beyond its authority is substantially weaker but still significant. Perhaps the weaker effect can be explained by the fact that the question asks about courts stopping the government ‘acting beyond its authority’.Footnote6 If we had only asked about courts being able to stop the government, the association may have been stronger.

In this first study we can – in line with our theoretical expectations – conclude that nativists are less likely than non-nativist to perceive constraints on the majority’s will to be important for democracy in general. Thus, the analysis provides strong support for H1.

Study 2: Nativism and support for unconstrained forms of democratic decision-making

In this study, we use data from module 5 of the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) to test hypotheses 2 and 3, stipulating that nativism is positively related to support for unconstrained forms of decision-making. To test H2, we use an item tapping support for explicitly majoritarian decision-making. It asks the respondents to agree or disagree with the statement ‘The will of the majority should always prevail, even over the rights of minorities’. Arguably, this item taps support for a type of democracy where policymaking is based purely on the unconstrained will of the majority, and where there are no counter-majoritarian, or ‘minoritarian’ (Claassen Citation2020), institutions in place to protect the rights and interests of minorities.

In order to test H3, we use an item measuring support for a more direct type of democratic decision-making and that asks respondents to agree or disagree to the proposition that ‘The people, not politicians, should make our most important policy decisions’. This item has earlier been included as a component in indices measuring more general populist attitudes, with the purpose of tapping the populist conception that politics should be the fulfilment of the ‘will of the people’ (e.g. Akkerman et al. Citation2017; Geurkink et al. Citation2020). Nevertheless, we argue that this is a valid measure of public support for the main principle of direct democracy, where the will of the people prevails through re-delegation of power from political representatives to the people (it also correlates strongly with more explicit questions about direct democratic institutions, see Study 4 below). Both dependent variables are scaled from 1 (‘strongly agree’) to 5 (‘strongly disagree’). To measure nativist attitudes, we construct an index similar to the one used in study 1, ranging from 1 (low nativism) to 5 (high nativism) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80) (see Online Appendix B2).

In order to examine our hypotheses, we regress support for majority rule and rule by the people on nativism. When available, we use the same control variables as before. Unfortunately, the CSES does not include any indicators of authoritarianism. However, to separate the effects of nativism and populism, we control for populist radical right vote and introduce an index measuring anti-elite attitudes.Footnote7 Descriptive data for the variables are presented in Table A5 in the Online Appendices.

Results

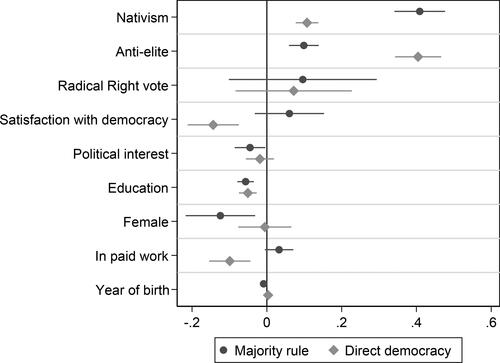

presents the results from two regressions on the pooled sample of countries from the CSES. The full models can be found in Table A6. A simple inspection reveals that nativist attitudes constitute an important predictor of support for both majority rule and direct democracy. Rule by the majority without taking interests of minorities into account stands out as particularly attractive to nativists.

Figure 2. Nativism and support for unconstrained forms of democracy, CSES (OLS with country clustered standard errors).

Comment: Regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals. Country dummies are included but not shown. The full models are presented in Table A6 (models 3 and 6). Descriptive statistics can be found in Table A5.

The coefficient of 0.41 implies that the difference in support for majority rule between the lowest level and highest level of nativism is more than one and a half point on the five-point scale of the dependent variable. All in all, the data provide solid support for hypotheses 2 and 3.

Study 3: Nativism and support for strong leaders

In order to test H4 – i.e. that nativists are more likely than non-nativists to support a strong leader even if s/he sidesteps fundamental principles of liberal representative democracy – we investigate how nativism correlates with an item from the European Values Study (EVS) tapping respondents’ preferences for having a strong leader that does not have to bother with parliament and elections. The variable is scaled from 1 (‘very bad’) to 4 (‘very good’). We measure nativist attitudes with an index like the ones used in the previous studies (see Online Appendix C2). The variable ranges from 1 to 10 (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78) We use the same control variables as in Study 1.Footnote8 The index measuring authoritarian attitudes does, however, differ in its construction.Footnote9

Results

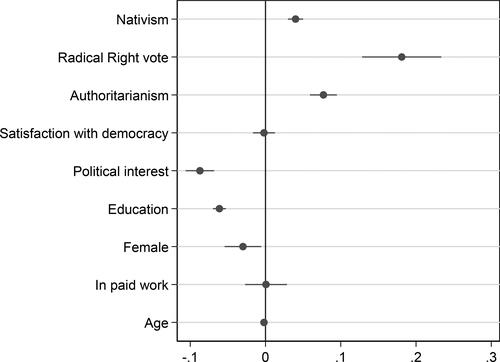

displays the results of a model where support for a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament and elections is regressed on nativism and our control variables. The results support our expectation that nativists are more likely than non-nativists to view this explicitly non-democratic form of government as an attractive option. There is, thus, solid support for H4.

Figure 3 . Nativism and support for a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament and elections, EVS (OLS with country clustered standard errors).

Comment: Regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals. Country dummies are included but not shown. The full model is presented in Table A8. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table A9.

Study 4: Nativism, majority beliefs and support for direct democracy

In our last study we test hypotheses 5-7. First, we investigate whether nativists are more prone than non-nativist to believe themselves to be in the majority on immigration policy (H5). Second, we investigate whether nativists’ support for direct democracy is based on a principled understanding of democracy, or whether they rather are ‘democratic opportunists’ that support direct democracy only when they believe themselves to be in the majority (H6) and their political representatives to be of a different opinion (H7). If nativists are principled adherents of direct democracy, they should be more supportive than non-nativists regardless of their beliefs about people’s and politicians’ opinions. However, if they are mainly opportunists, we should expect their support to vary with their beliefs about the people’s and politicians’ attitudes to restrict immigration.

In order to test these hypotheses, we collected data on nativist attitudes and beliefs about people’s and politicians’ support for restrictive immigration policies, which is arguably nativists’ most important political issue, using the probability-based online national survey the Norwegian Citizen Panel (NCP), administered by the Digital Social Science Core Facility (DIGSSCORE) at the University of Bergen. The survey was fielded in October and November 2019 (N = 2,473).Footnote10 We measure nativism by the same index as in Study 2.Footnote11 To tap respondents’ beliefs about opinions we ask them to what extent they believe that a) politicians, and b) the Norwegian people think it is a good proposal to accept fewer refugees into the country.Footnote12

In order to measure attitudes towards direct democracy we use two variables. The first is the same as the CSES item in Study 2 (‘The people, not politicians, should make our most important policy decisions’). We complement this item with a question that asks whether ‘It should be possible for ordinary people to take the initiative regarding national referendums’, to be certain that the respondents understand that we are asking about direct democracy per se, and not about the general democratic principle of decision-making by a majority of the people. Both items have a response scale ranging from 1 (‘completely disagree’) to 5 (‘completely agree’). The Pearson’s correlation coefficient for the two dependent variables is 0.62, which indicates that they capture a common underlying attitude to direct democracy. Descriptive statistics of all variables are presented in Table A12 in the Online Appendices.

Results

Before we put hypotheses 5-7 to test, it should be noted that we find the same positive association between nativism and support for direct democracy in the NCP data as in the analysis based on the CSES (see Table A10). As we argue in the theoretical section, the positive association between nativism and direct democracy can potentially be explained by the fact that nativists believe themselves to be in the majority. As demonstrated in , a whopping 80 percent of nativists believe a majority of the people to be on their side on immigration policy, whereas only about half of non-nativists hold a similar belief.

Table 1. Beliefs about the majority position on immigration policy.

These figures should be compared with the fact that only 34 percent of the respondents (who constitute a representative sample of the Norwegian population) think it is a good proposal to reduce the number of refugees, whereas 37 percent think it is a bad proposal (with the remaining not having a strong opinion). Nativists thus overestimate the extent to which their opinions are shared by (a majority of) the people, and they do so to a larger extent than non-nativists. H5 is thus confirmed.

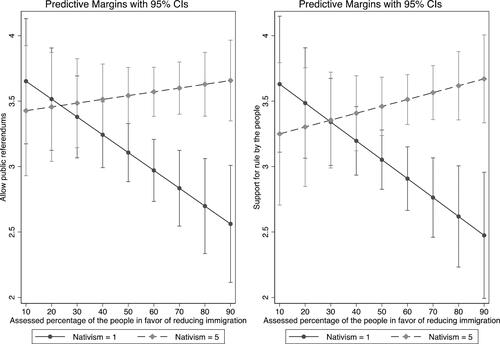

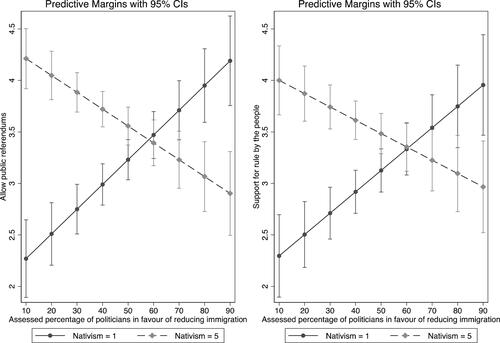

To investigate if nativists’ support for direct democracy is contingent on beliefs about the opinion among the people and politicians (i.e. whether H6 and H7 are true), we run models with interactions between nativism and respondents’ beliefs about the immigration opinion among a) politicians, and b) the people (with controls for a number of possible confounders). The interactions between nativism and beliefs about the Norwegian people’s support for more restrictive immigration policies are displayed separately for the two dependent variables in .

Figure 4. Assessed percentage of the people in favour of reducing immigration and support for direct democracy among nativists and non-nativists (NCP).

Comment: The full models are presented in Table A11 in the Appendix.

The results show that strong nativists (those who score 5 on the nativist index, which ranges from 1 to 5) and strong non-nativists (those who score 1 on the same index) express similar preferences for direct democracy when they believe that a minority of the people support restrictive immigration policies (although less than 20 percent of nativists do so). However, nativists are much more likely to express a preference for direct democracy among those respondents who believe that 50 percent or more of the population want more restrictive immigration policies. The gap between nativists and non-nativists is substantial and can be ascribed to the fact that nativists become more, and non-nativists less, positive to direct democracy as they believe that a larger share of the people favour reducing immigration. H6 is, thus, confirmed.

We find an even stronger interaction between nativism and respondents’ beliefs about politicians’ support for restrictive immigration policies. This interaction is illustrated separately for the two dependent variables in . The figure shows that nativists are only more supportive of direct democracy than are non-nativists if they believe that less than 50 percent of politicians want to reduce immigration. H7 is thus confirmed. This is both because nativists become less, and non-nativists more, positive to direct democracy the more positive they believe politicians are to reduce the influx of refugees. When nativists start to believe that a majority of politicians is in favour of reducing immigration, they become less positive than non-nativist to direct democracy.

Figure 5. Assessed percentage of politicians in favour of reducing immigration and support for direct democracy among nativists and non-nativists (NCP).

Comment: The full models are presented in Table A11.

Source: Norwegian Citizen Panel 16 (2019).

To sum up, the analyses presented here indicate that both nativists and non-nativists are opportunistic in their support for direct democracy. The more they believe the people, and the less they believe politicians, to be on their side on immigration policy, the more they prefer direct democratic decision-making. These results correspond neatly to recent research demonstrating that people in general take their outcome expectations and the perception of being in the majority into account when expressing support for direct democracy (Landwehr and Harms Citation2020; Werner Citation2020).

That being said, there is little variation in nativists’ beliefs about the people’s opinion on immigration. The overwhelming majority of nativists believe that a majority of the people are on their side on immigration, whereas in fact only a minority are. Non-nativists have much more realistic beliefs about the public opinion. Thus, it is not strange that nativists come out as stronger supporters on direct democracy and majority rule in general.

Concluding remarks

During the last decades, nativism has manifested itself as a central political phenomenon in an increasing number of western democracies. The surge of nativism in politics will probably have both short- and long-term consequences for how people perceive democracy, both as an actual system of government and as a normatively loaded concept. In this study, we advance the argument that nativism as a political idea entails an understanding of and preference for democracy that differs from the currently dominating liberal representative democratic model.

We contend that a nativist worldview – emphasising the homogenous native people and its interests and values as the moral foundation of society – always implies a sceptical view of minority rights and constraints on the executive. We also argue that for nativists democracy is just one of several possible strategies to implement policies that favour the native people, and that their support for more specific forms of decision making is contingent on their beliefs about whether the people and the politicians strive for the native people’s interests. However, their tendency to see the morally relevant native people as a homogenous entity makes them more prone than non-nativist to believe that the people are of the same opinion as themselves on important matters (as, for example, immigration policy). Hence their populist support for direct democracy.

We test our argument in four studies. In the first study, we use data on public perceptions of democracy from the European Social Survey to show that nativists are less likely than others to perceive constraints on the majority’s will as being important for democracy in general. The second study, which builds on recent data from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems, reveals a strong positive association between nativism and support for direct decision-making by the people and pure majoritarian rule. The third study, which is based on data from the European Values Study, shows that nativists are also more prone than non-nativists to support strong leaders that do not have to bother with parliaments and elections, indicating that nativists are less principled supporters of democracy.

In the fourth study we use the Norwegian Citizen Panel to first show that nativists believe themselves to be in the majority on immigration policy, even though they in fact are in the minority. We then find substantial opportunistic support for direct democracy, both among nativists and non-nativists. The more nativists believe the people, and the less they believe politicians, to be on their side on immigration policy, the more they prefer decision-making by the people rather than by politicians. Coupled with their (incorrect) belief that they are in the majority, this opportunistic trait can to a large extent explain why nativists are more supportive of direct democracy than non-nativists are. Hence, nativists are not ideological, but opportunistic, adherents of direct democracy, and there is no necessary connection between nativism and populist forms of decision making (as far as support for direct democracy is part of populism).

All in all, our examination of the relationship between nativism and notions of democracy has implications for future studies on democratic attitudes. We have demonstrated that nativism goes hand in hand with preferences for a type of democracy where the interests of the natives should prevail, even at the cost of diminished minority rights, checks and balances, and other constraints on executive power. Liberal representative democracy is not for nativists.

What is potentially more troublesome is that nativists seem to believe that the end justifies the means when it comes to representative democracy. This opportunistic trait usually translates into support for more direct democracy and scepticism towards representative democracy, because nativists (often erroneously) believe that they are in the majority. As long as they do so, Klingemann and Hofferbert (Citation1994: 36) may be right in noting that ‘one can be a nativist and still be a democrat.’ But if so, the nativist is a different kind of democrat compared to the one we are used to.

But what happens if the nativists come to believe/realise that a majority of the morally relevant people and political elites are non-nativists? In such circumstances they may potentially turn away from democracy altogether. The fact that some nativists are positive to a strong leader, who does not have to bother with parliaments and elections, indicates that some of them may have already done so (if they do not interpret the question as a vote of confidence for political elites in the parliament). In the past, nativists have also been much more prone to embrace authoritarian leaders than they are today (as illustrated by politics in interwar Europe). Nativists’ tendency to believe that they are in the majority may thus be a blessing of sorts: Even if it undermines their support for representative democracy, it may at least keep them from supporting political alternatives to democracy.

Admittedly, the findings in this article are correlational in nature. It remains for future studies to explore whether nativists really are as opportunistic as we argue, and that beliefs about public and elite opinions have the causal effects on their support for different forms of decision making that we claim. But potentially our findings have important repercussions for democratic politics as we know it, given that nativism in recent years has become a more important mobilising ground for political parties.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (618.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for valuable and constructive comments throughout the process. We appreciate helpful and constructive comments from Peter Esaiasson and Stefan Dahlberg as well as from participants at the 2019 APSA and ECPR annual conferences. This research was made possible by grants from the Research Council of Norway (grant number 275308) and the Swedish Research Council (VR 2018-01468).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrej Kokkonen

Andrej Kokkonen is Associate Professor of Political Science, University of Gothenburg. His research focuses on history and politics, autocracies, populist radical right parties, and anti-immigrant attitudes. His articles have appeared in American Political Science Review, British Journal of Political Science, Comparative Political Studies, and Journal of Politics, amongst others. [[email protected]]

Jonas Linde

Jonas Linde is Professor at the Department of Comparative Politics, University of Bergen. His research on political support and attitudes towards democracy has been published in journals such as European Journal of Political Research, Governance, Journal of Politics, and Party Politics. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 It should be noted that nativism is a continuous attitude – both theoretically and in our empirical models – with no obvious cut-off point. When we refer to ‘nativists’ and ‘non-nativists’, we are using this as shorthand to distinguish between high and low levels of nativism.

2 In recent years immigration laws have become stricter in many countries, partially due to the rise of nativist parties. Even if this can be seen as evidence that nativists are not always on the losing side of politics, we still believe that (extreme) nativists do not see it that way. Immigration does, after all, still continue in all western countries, even if at lower levels than previously. And from a extreme nativist perspective that is a failure.

3 They measure majoritarian democracy by asking respondents to agree or disagree with the proposition that ‘majority decisions must apply, even if they curtail minority rights’.

4 We construct a dummy variable where 1 denotes that the respondent voted for a populist radical right party and 0 for all other parties. Coding of parties is presented in Table A1 in the Online Appendices.

5 The index ranges from –15 to +15. See Online Appendix C1 for details.

6 As Table A2 shows, the strong bivariate relationships between nativism and these elements of liberal democracy are only marginally weakened when introducing control variables.

7 The populist radical right vote variable is a dummy where respondents stating that they voted for a populist radical right party in the latest election is coded as 1 (and the rest as 0). Coding of parties is described in Table A4. Anti-elite attitudes are measured by an index from three propositions about political elites: ‘Politicians are the main problem in [country]’, ‘Most politicians do not care about the people’, and ‘Most politicians are trustworthy’. These items are scaled from 1 (‘strongly agree’) to 5 (‘strongly disagree’). Using the same procedure as for the nativism index, we construct an “anti-elite” index that runs from 1 to 5 (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74).

8 Coding of populist radical right parties can be found in Table A7. Descriptives for all variables can be found in Table A9 in the Online Appendices.

9 The index builds on twelve items and is detailed in Online Appendix C2.

10 See the NCP methodology report for details (Skjervheim et al. 2019).

11 ‘Immigrants are generally good for Norways’s economy’, ‘Norwegian culture is generally harmed by immigrants’, and ‘Immigrants increase crime rates in Norway’.

12 The exact wordings of the questions are: (a) ‘In your opinion, what percentage of politicians believe that it is a good proposal for Norway to accept fewer refugees?’, (b) ‘In your opinion, what percentage of the Norwegian people believe that it is a good proposal for Norway to accept fewer refugees?’ (response scale: 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100 per cent).

References

- Abts, Koen, and Stefan Rummens (2007). ‘Populism versus Democracy’, Political Studies, 55:2, 405–24.

- Akkerman, Agnes, Andrej Zaslove, and Bram Spruyt (2017). “We the People” or “We the Peoples”? A Comparison of Support for the Populist Radical Right and Populist Radical Left in The Netherlands’, Swiss Political Science Review, 23:4, 377–403.

- Bartels, Larry M. (2020). ‘Ethnic Antagonism Erodes Republicans’ Commitment to Democracy’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117:37, 22752–9.

- Berntzen, Lars Erik (2020). Liberal Roots of Far Right Activism: The Anti-Islamic Movement in the 21st Century. London: Routledge.

- Betz, Hans-Georg (2019). ‘Facets of Nativism: A Heuristic Exploration’, Patterns of Prejudice, 53:2, 111–35.

- Canovan, Margaret (1999). ‘Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy’, Political Studies, 47:1, 2–16.

- Claassen, Christopher (2020). ‘In the Mood for Democracy? Democratic Support as Thermostatic Opinion’, American Political Science Review, 114:1, 36–53.

- Doherty, David, and Jennifer Wolak (2012). ‘When Do the Ends Justify the Means? Evaluating Procedural Fairness’, Political Behavior, 34:2, 301–23.

- Eatwell, Roger, and Matthew Goodwin (2018). National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy. London: Penguin.

- Esaiasson, Peter, Mikael Persson, Mikael Gilljam, and Torun Lindholm (2019). ‘Reconsidering the Role of Procedures for Decision Acceptance’, British Journal of Political Science, 49:1, 291–314.

- Font, Nuria, Paulo Graziano, and Myrto Tsakatika (2021). ‘Varieties of Inclusionary Populism? SYRIZA, Podemos and the Five Star Movement’, Government and Opposition, 56:1, 163–83.

- Galston, William A. (2018). Anti-Pluralism: The Populist Threat to Liberal Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Geurkink, Bram, Andrej Zaslove, Roderick Sluiter, and Kristof Jacobs (2020). ‘Populist Attitudes, Political Trust, and External Political Efficacy: Old Wine in New Bottles?’, Political Studies, 68:1, 247–67.

- Golder, Matt (2016). ‘Far Right Parties in Europe’, Annual Review of Political Science, 19:1, 477–97.

- Guia, Aitana (2016). The Concept of Nativism and Anti-Immigrant Sentiments in Europe. Max Weber Programme Working Paper 2016/20. Fiesole: European University Institute.

- Hainmueller, Jens, and Dominik Hangartner (2019). ‘Does Direct Democracy Hurt Immigrant Minorities? Evidence from Naturalization Decisions in Switzerland’, American Journal of Political Science, 63:3, 530–47.

- Harteveld, Eelco, Andrej Kokkonen, Jonas Linde, and Stefan Dahlberg (2021). ‘A Tough Trade-Off? The Asymmetrical Impact of Populist Radical Right Inclusion on Satisfaction with Democracy and Government’, European Political Science Review, 13:1, 113–33.

- Heinisch, Reinhard, and Carsten Wegscheider (2020). ‘Disentangling How Populism and Radical Right Ideologies Shape Citizens’ Conceptions of Democratic Decision-Making’, Politics and Governance, 8:3, 32–44.

- Horowitz, Donald L. (1993). ‘The Challenge of Ethnic Conflict: Democracy in Divided Societies’, Journal of Democracy, 4:4, 18–38.

- Ivarsflaten, Elisabeth (2008). ‘What Unites Right-Wing Populists in Western Europe? Re-Examining Grievance Mobilization Models in Seven Successful Cases’, Comparative Political Studies, 41:1, 3–23.

- Ivarsflaten, Elisabeth, Scott Blinder, and Lise Lund Bjånesøy (2020). ‘How and Why the Populist Radical Right Persuades Citizens’, in Elizabeth Suhay, Bernard Grofman, and Alexander H. Trechsel (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Persuasion. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 814–37.

- Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2012). ‘The Ambivalence of Populism: Threat and Corrective for Democracy’, Democratization, 19:2, 184–208.

- Kesic, Josip, and Jan Willem Duyvendak (2019). ‘The Nation under Threat: Secularist, Racial and Populist Nativism in The Netherlands’, Patterns of Prejudice, 53:5, 441–63.

- Klingemann, Hans-Dieter, and Richard I. Hofferbert (1994). ‘The Axis Powers 50 Years Later: Germany-a New Wall in the Mind’, Journal of Democracy, 5:1, 30–44.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter (2014). ‘The Populist Challenge’, West European Politics, 37:2, 361–78.

- Landwehr, Claudia, and Philipp Harms (2020). ‘Preferences for Referenda: Intrinsic or Instrumental? Evidence from a Survey Experiment’, Political Studies, 68:4, 875–94.

- McLaren, Lauren (2012). ‘The Cultural Divide in Europe: Migration, Multiculturalism, and Political Trust’, World Politics, 64:2, 199–241.

- McLaren, Lauren (2015). Immigration and Perceptions of National Political Systems in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Moffitt, Benjamin (2020). ‘Populism’, Cambridge: Polity.

- Mudde, Cas (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, Cas (2010). ‘The Populist Radical Right: A Pathological Normalcy’, West European Politics, 33:6, 1167–86.

- Müller, Jan-Werner (2016). What Is Populism? Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Nodia, Ghia (1992). ‘Nationalism and Democracy’, Journal of Democracy, 3:4, 3–22.

- Rooduijn, Matthijs, Bart Bonikowski, and Jante Parlevliet (2021). ‘Populist and Nativist Attitudes: Does Ingroup-Outgroup Thinking Spill over across Domains?’, European Union Politics, 22:2, 248–65..

- Rydgren, Jens (2008). ‘Immigration Sceptics, Xenophobes or Racists? Radical Right-Wing Voting in Six West European Countries’, European Journal of Political Research, 47:6, 737–65.

- Skitka, Linda (2002). ‘Do the Means Always Justify the Ends or Do the Ends Sometimes Justify the Means? A Value Protection Model of Justice Reasoning’, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28:5, 588–97.

- Skjervheim, Øivind, Asle Høgestøl, Olav Bjørnebekk, and Amund Eikrem (2019). Norwegian Citizen Panel 2019, Sixteenth Wave: Methodology Report. Bergen: Ideas2Evidence and Norsk Medborgerpanel.

- Taggart, Paul (2000). Populism. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Teorell, Jan (2010). Determinants of Democratization: Explaining Regime Change in the World, 1972–2006. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Watts, Meredith W., and Ofer Feldman (2001). ‘Are Nativists a Different Kind of Democrat? Democratic Values and “Outsiders” in Japan’, Political Psychology, 22:4, 639–63.

- Werner, Hanna (2020). ‘If I’ll Win It, I Want It: The Role of Instrumental Considerations in Explaining Public Support for Referendums’, European Journal of Political Research, 59:2, 312–30.

- Poulsen, Winther Regin (2021). ‘How the Danish Left Adopted a Far-Right Immigration Policy’, Foreign Policy, available at https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/07/12/denmark-refugees-frederiksen-danish-left-adopted-a-far-right-immigration-policy/ (accessed 19 November 2021).

- Zhao, Yikai (2019). ‘Testing the Measurement Invariance of Nativism’, Social Science Quarterly, 100:2, 419–29.