?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

How does ministries’ capacity to draft legislation affect the political output of modern governments? This article combines a novel dataset describing the capacity of ministerial bureaucracies to attend to about 250 distinct policy issues with content-coded data on government legislation. The sample consists of Danish, Dutch and German governments, jointly spanning the time from 1995 to 2013. The analysis reveals three main findings: firstly, issue-specific bureaucratic capacity unconditionally increases governments’ legislative activity; secondly, legislative activity is stifled if bureaucratic capacity is spread across different ministries; thirdly, against theoretical expectations the productive effect of bureaucratic capacity is not positively related to governments’ issue salience. The results indicate that the design and resources of ministerial portfolios affect policy making in western governments.

Between political preferences and written laws sits a both restraining and empowering bureaucracy (Berman Citation1966). While politicians provide rough policy sketches, the actual task of drafting government legislation is mostly delegated to ministries’ civil servants, who bear the necessary expertise and capacity to both flesh out policy ideas and translate them into clauses that align with the existing legal framework (Berman Citation1966; Bonnaud and Martinais Citation2014; Page Citation2003). Against this backdrop, the article investigates how bureaucratic capacity, i.e. the amount of issue-specific resources that enable the ministerial bureaucracy to deal with individual policy issues, helps governments to design legislation in different administrative and political contexts.

The baseline expectation is that governments can sponsor more bills if the ministerial bureaucracy possesses more capacity to deal with a policy issue. Yet this correspondence is not unconditional. Although ministries are commonly assumed to have rather exclusive dominance over their policy areas (e.g. Laver and Shepsle Citation1994, Citation1996), the empirical reality often looks messier. Governments regularly allow multiple ministries to engage with the same policy issue (Dewan and Hortala‐Vallve Citation2011; Fernandes et al. Citation2016; Heppell Citation2011; Klüser and Breunig Citation2019; Saalfeld and Schamburek Citation2014), which requires well-documented coordination mechanisms in the ministerial bureaucracy (Mayntz and Scharpf Citation1975; Scharpf and Mohr Citation1994). Hence, diffuse ministerial responsibility potentially makes the process of drafting legislation more costly and impinges on governments’ willingness to initiate it in the first place.

Moreover, while it is well established that governments strive to focus their legislative efforts on salient policy issues (Borghetto et al. Citation2014; Breunig Citation2014; Breunig et al. Citation2019; Chaqués-Bonafont and Palau Citation2014), this literature focuses less on the process of how political attention is translated into legislative outputs. Yet the ministerial bureaucracy linking policy inputs and outputs is interesting as it directly speaks to the limited information-processing capacities of actors in politics, which underpins most of the contemporary agenda-setting literature (Jones and Baumgartner Citation2005). Governments’ ambitions may be high, but unless they are met with the appropriate bureaucratic capacity to turn ideas into bills that may eventually become law, these ambitions are unlikely to be turned into action.

These claims are tested on a novel dataset that informs us about the amount of bureaucratic capacity ministries have at their disposal to deal with individual policy issues. Based on organisation charts of ministries and annual publications on the public sector, the dataset comprises about 30,000 single coded observations of bureaucratic capacity in five Danish, seven Dutch, and four German governments from the mid-1990s to about 2010. Employing a series of negative-binomial regressions, the first two theoretical claims are corroborated. However, the stipulated interaction between bureaucratic capacity and issue salience cannot be established empirically.

Bureaucratic capacity at work

All over the world, politicians rely on bureaucrats – who ‘often have impressive reservoirs of technical expertise that can help cabinet ministers to achieve their policy goals’ (Huber Citation2000: 401) – to draft laws. Speaking to this commonplace, Page (Citation2003) describes distinct phases of ministerial policy making: policy input, drafting, and parliamentary management. The first phase is political and ensures that the democratically elected officials reserve the prerogative to insert policy ideas into the bureaucratic machinery.

Yet the ministerial administration enjoys significant influence in the phase of drafting. This includes the actual work of translating policy inputs into fully fledged policies and finally, legal clauses – a job that is generally commissioned to highly specialised experts within the ministerial bureaucracy. Civil servants have a considerable degree of freedom in developing legislation and are often directly involved in the development of policies. This is necessary as most political inputs lack the sufficient degree of detail and thus need to be fleshed, passing back and forth between the bureaucratic policy experts and the political leadership to draft effective legal language that does not contradict existing provisions (Bonnaud and Martinais Citation2014; Page Citation2003). However, more substantial changes of legislative drafts must be cleared by the political leadership before they can be published. This reservation conforms with the arguments made by delegation theorists, who assert that devices such as monitoring (Banks Citation1989), oversight (Lupia and McCubbins Citation1998; McCubbins and Schwartz Citation1984), and sanction (Weingast and Moran Citation1983) effectively bind bureaucratic agents to their principal’s preferences.

The final step, parliamentary management, concerns the steering of bills through the parliamentary process. While predominantly managerial, during this phase the ministerial bureaucracy is charged with shielding bills against undesired amendments, drafting briefings, or answering inquiries from both the parliament and the media (Page Citation2003).

Regardless of the substantial policy influence the ministerial bureaucracy bears during the drafting of bills, its administrative capacity constitutes the bottleneck through which governments must funnel policy inputs to turn preferences into legislative drafts. Couched in slightly different parlance, this is a similar claim made by the literature on policy agendas, which argues that public officials are forced to prioritise among competing policy issues, as the total amount of their political attention is limited (Baumgartner and Jones Citation1993; Jones and Baumgartner Citation2005). In either case, just as the number of social stimuli to which a government can respond is limited by its political attention, policy inputs provided by elected politicians must meet appropriate bureaucratic capacity and competence to be elaborated and turned into legal language. Put bluntly, more bureaucratic capacity allows governments to produce more legislative paperwork. Restating this more formally as a baseline hypothesis, it is conjectured that for each policy issue, more bureaucratic capacity increases the number of legislative initiatives that governments launch.

In contrast to the theoretical assumption of portfolio exclusivity advocated by models of ministerial governance (Laver and Shepsle Citation1996), studies show that responsibility for policy issues within coalition governments often falls under the purview of multiple ministers (Dewan and Hortala‐Vallve Citation2011; Heppell Citation2011; Klüser and Breunig Citation2019; Saalfeld and Schamburek Citation2014). In such instances, ministerial responsibility is diffuse, meaning that policy-making authority regarding such policy issues spans more than one ministerial jurisdiction. This bears the potential for inter-ministerial disputes because multiple ministries can both credibly claim to be in charge of the policy-making process and provide elaborate, yet distinct policy ideas. A brief episode of German policy making can serve as an illustration. In the early 2000s, cold calls were skyrocketing and became a nuisance in Germany (Graw and Ehrenstein Citation2007; Leins Citation2007). Being regarded as a matter of consumer safety in domestic commerce, the problem largely fell within the jurisdiction of the Ministry for Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection. However, a sizable part of policy-making expertise in this field also rested with four other ministries: Economic Affairs, Finance, Justice, and Social Policy. In 2007, the Ministry of Justice took the lead and announced swift legislative countermeasures. Given the issue was highly salient and resonated well with the public, both the Ministry of Economic Affairs and the Ministry for Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection followed suit and also claimed responsibility for the matter, eager to scoop potential credit. Since the three ministries had different stakes in the issue and thus needed to resolve their inter-ministerial struggles, the introduction of the bill was postponed multiple times for two years and was not signed into law until mid-2009, by which time it officially bore the signatures of three different ministers.Footnote1

Addressing this potential for conflict, governments need coordination mechanisms to sort out potential inter-ministerial disagreement that may arise in policy areas where ministerial responsibility is diffuse. The most apparent coordination device is probably the central authority of the prime minister or other powerful executive actors. Prime ministers are often vested with powers to control and correct proposals submitted by the ministers. For instance, in many countries with ministerial equality, the prime minister’s vote carries some extra weight when it comes to breaking a tie within the cabinet. In other cases, such as France or Germany, the PM is officially allowed to give specific instructions to ministers (Art. 21 French Constitution, Art. 65 German Basic Law). Yet authority is by no means restricted to flow from the prime minister. Particularly in Denmark, the Ministry of Finance has been bestowed with the task of governmental coordination since the 1980s. Due to its function as a watchdog over the national budget, it retains considerable power over ministerial proposals which involve the allocation of funds (Greve Citation2018; Jensen Citation2008).

Besides those unitary actors, authority and coordination can also flow from institutions comprised of multiple actors. In the case of coalition governments, many countries know coalition committees that generally consist of top ministers and prominent party figures (cf. DeWinter Citation1993; Müller Citation1997; von Beyme Citation1983). In those committees, coalition parties sort out contentious issues and settle inter-ministerial disputes (for a German example, see Miller and Müller Citation2010). Thus, from the perspective of ordinary ministers, such committees fulfil a hierarchical function similar to those of prime ministers or ministers of finance.

Apart from drawing on central authority, governments may foster direct inter-ministerial coordination to sort out disagreements between ministries. Such coordinating mechanisms can be either (semi-)formalised venues or incentive structures, which encourage ministers to consider their colleagues’ preferences during the process of designing legislation. Referred to as positive coordination (Scharpf and Mohr Citation1994: 18), the German federal bureaucracy, for instance, routinely creates inter-ministerial working groups in response to policy problems that transgress the jurisdictions of individual ministries (Mayntz and Scharpf Citation1975; Wegrich and Hammerschmid Citation2018). This form of inter-ministerial coordination is even defined in the by-laws regulating the interaction of German federal ministries, which stipulate that for issues falling under the purview of more than one ministry, the administration must cooperate to ensure a cohesive governmental policy. In contrast to those ad hoc committees, Danish governments use two standing committees to coordinate policy proposals between ministries. Chaired by the permanent secretaries from the Prime Minister’s Office and the Ministry of Finance, these bodies seek solutions to policy problems that cross-cut ministerial boundaries. The result is comprehensive inter-ministerial coordination that has turned ministerial decision making into a reconciliatory process, in which contentious issues must be resolved among involved ministries (Bo Smith-udvalget Citation2015: 85–86).

Regardless of which mechanism governments prefer, inter-ministerial coordination imposes transaction costs (North Citation1990) on the relevant ministries and thus makes the process of drafting legislation more costly and time-consuming. Therefore, at the margin, diffuse ministerial responsibility is likely to diminish the positive effect of bureaucratic capacity on legislative activity, since a substantial amount of bureaucratic capacities must be spent on inter-ministerial coordination.

The first two lines of reasoning ignore the question whether governments use bureaucratic capacity strategically: do governments particularly use bureaucratic capacity to initiate legislation in issue areas salient to them? In this context, it is important to remember that the ministerial administration generally does not initiate legislation on its own, but relies on inputs from elected politicians, which it translates into legislative drafts (Bonnaud and Martinais Citation2014; Page Citation2003). Therefore, bureaucratic capacity only becomes a bottleneck for the legislative process if the number of political stimuli exceeds the ministerial bureaucracy’s capacity to address them. In other words, when there is no steady stream of political inputs being squeezed through the funnel of bureaucratic capacity, the bureaucratic ‘machinery of government’ (White and Dunleavy Citation2010) runs dry.

The steadiest stream of political inputs can be expected for policy issues that are salient to governments. In these policy areas, governments are particularly eager to initiate legislation, be it because they intrinsically care about the underlying social condition or because their constituting parties have promised to act during their electoral campaigns. These promises can be more general mandates for policies (Budge and Hofferbert Citation1990; McDonald and Budge Citation2005) or very specific policy pledges (Thomson et al. Citation2017). Parties’ statements of intent are by no means just empty promises but bind them (Thome Citation1999; Thomson Citation2001) and trickle down to both public budgets (Budge and Hofferbert Citation1990) and, especially, legislative activity (Stimson et al. Citation1995; Walgrave et al. Citation2006). Either way, governments are likely to be particularly eager to have the ministerial bureaucracy draft legislation in those issue areas that are salient to them. Consequentially, at the margin, the positive effect of bureaucratic capacity on legislative activity should be more pronounced for salient policy issues.

The hypothesised claims can be summarised as follows. Regardless of the institutional and political context, more bureaucratic capacity is expected to yield a larger number of legislative drafts supplied by the government (H1). However, this effect diminishes if ministerial responsibility for a policy issue is diffuse (H2), or the government does not regard the issue as salient (H3).

Data

The theoretical conjectures are tested on a sample consisting of five Danish, seven Dutch, and four German governments, jointly spanning the time from 1995 to 2013. Undeniably, the selection of these three parliamentary democracies with a stable tradition of multiparty governments is partly driven by both language restrictions and data availability concerns, as the outlined hypotheses draw on a pool of different sources which are not readily available for the entire universe of developed parliamentary systems. However, there are also compelling theoretical reasons supporting the sample selection (see country studies in Thijs and Hammerschmid Citation2018). Firstly, all three countries represent least likely cases regarding the effect of bureaucratic capacity, as they feature strong parliaments with ample corrective competencies that do not necessarily rely on bureaucratic drafts to issue legislation (Martin and Vanberg Citation2011).

Secondly, within this set of least-likely cases, Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands are sufficiently diverse as to allow generalisations beyond those three countries. Their organisational models of the top-tier public bureaucracy are fundamentally different, and they enforce ministerial cooperation both to a varying degree and via distinct means. Denmark structures most of its ministries according to an agency model, where decision-making authority is shared between a small central political department and various semi-independent public agencies. While ministries are generally independent, the strong role of the Prime Minister’s Office and the Finance Ministry nevertheless ensure a considerable degree of governmental cohesion (Greve Citation2018). In contrast, the German ministerial bureaucracy also employs a variety of affiliated public agencies, but fully concentrates decision-making authority within the actual ministry. Cohesion between ministries is primarily enforced through a semi-institutionalised process of negative coordination (Mayntz and Scharpf Citation1975), which requires ministries to have their policy drafts checked by other units for potential turf violations (Wegrich and Hammerschmid Citation2018). Lastly, Dutch ministries have always been a collection of quite autarkic departments – and while some reforms have been put in place to strengthen governmental cohesion, the powers of the prime minister to enforce cooperation are still limited (van der Meer Citation2018). Therefore, the selection of cases offers a sufficient variety of different types of organisational patterns to ensure that insights are not merely produced by individual features of analysed polities.

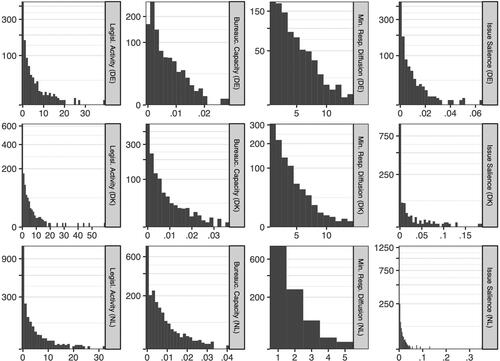

The following paragraphs outline in detail the data collection and measurement of the response variable, as well as the main explanatory variables. Furthermore, it briefly introduces the content-coding scheme that the data collection draws on. summarises all central variables by plotting their distribution, which is complemented by descriptive statistics shown in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 1. Histograms of bureaucratic capacity and the three explanatory variables. Grouped by country. Square root transformation applied to y-axis to accommodate the discrepancies in empirical frequencies. For tabular representation, please refer to Table A1 in the Supplementary Material. Figure A2 in the Supplementary Material shows Pearson correlation coefficients for all relevant variables.

Legislative activity

The dependent variable is defined as the amount of legislation a government initiates per policy issue during its term in office. Therefore, the unit of analysis is the bill count per policy issue within a government (policy issue × government). Importantly, the count variable only includes bills that were drafted by a governmental actor, which excludes all parliamentary bills drafted by either the government parties, individual members of parliament, or the opposition. While bills undoubtedly vary in scope and impact, this article follows the literature on the policy process, which commonly resorts to simple bill and law counts to gauge the legislative attention political actors devote to policy issues (Borghetto et al. Citation2014; Breunig Citation2014; Breunig et al. Citation2019; Chaqués-Bonafont and Palau Citation2014).

The data stems from the respective country projects of the Comparative Agenda Project (CAP), which studies how political actors deal with policy issues across numerous political systems (Baumgartner et al. Citation2019; Breunig and Schnatterer Citation2019; Green-Pedersen and Mortensen Citation2019). The central interest of this comparative project lies in investigating the rise and fall of policy issues on different political agendas (Baumgartner and Jones Citation1993; Baumgartner et al. Citation2019). To this end, the project developed a policy coding scheme consisting of roughly 250 exclusive and exhaustive policy issues, which are grouped in about 20 larger policy clusters.Footnote2 Although the general scheme has been adapted to account for country characteristics, the resulting country data is fully compatible and thus facilitates comparative analyses (Bevan Citation2019).

Bureaucratic capacity

The central explanatory variable cannot be measured in a similarly straightforward fashion. Generally, scholarship on portfolio allocation assumes that responsibility – and thus bureaucratic capacity – regarding policy issues is concentrated in one portfolio (Laver and Shepsle Citation1996). Since the policy information contained in the portfolio nomenclature is rather unspecific, a detailed analysis of ministerial policy capacity needs to unravel the allocation of distinct policy issues to ministerial portfolios. Moreover, any measure based on ministries’ names would be dichotomous and hence could not accommodate the continuous hypotheses spelt out previously.

Therefore, this article takes a different approach to elicit information about the policy issues ministries are devoted to. Be it in the form of organisational charts or recurring publications on the public sector, governments furnish information on the structure of their ministerial bureaucracy and, more importantly, information on the precise tasks individual working units within each ministry perform. Within each ministry, the unit of data elicitation is a working unit at the lower end of the formal hierarchy as described in the organisational structure.Footnote3 These working units are conventionally called ‘enhed’ or ‘kontor’ in Denmark, ‘Referat’ in Germany, and ‘bureau’ or ‘directie’ in the Netherlands.

The structural differences between Danish, Dutch, and German ministries feed back into the actual object of study. While it suffices to focus on the actual ministerial department in Germany and the Netherlands, the Danish agency model requires a broader perspective. Thus, the Danish data collection does not just draw on the actual ministerial department but understands a ministry as the larger ministerial conglomerate comprised of the department and its affiliated agencies. For each observed ministerial unit, all identified policy tasks are mapped onto the set of policy issues as defined by the Comparative Agenda Project’s codebook, which makes the resulting data comparable with the legislative activity count variable.Footnote4

The process of coding policy tasks was as follows: First, a sample of ministries was selected. For each policy unit within this sample, three trained student coders and the article’s author – all of whom have ample experience with the CAP coding scheme – decided whether (a) the office is not merely in charge of administrative tasks (e.g. IT maintenance) and, if this is the case, (b) how many policy tasks an office is responsible for. Depending on the latter decision, each task was coded according to the CAP codebook. The intercoder agreement is about 87% at the level of major policy codes and 80% for minor policy codes, that are clustered within the major categories. Based on this hand-coded sample, a supervised classifier was trained and subsequently applied to the remaining ministries. In case of low probability predictions, the classifications were reviewed and potentially adapted by the coders. In a second step, all assigned codes were computationally checked for internal consistency to ensure that, given a similar description of policy tasks, the same content code had been assigned during the coding procedure. If similar task descriptions were found to have been classified as different codes, it was decided on one alternative and the codes were adapted accordingly. Moreover, the algorithm checked whether offices existing in multiple governments were coded equally. As many policy tasks are described through concise and consistent keywords, this procedure ensures a high degree of internal consistency of the coding. The entire procedure yielded more than 30,000 coded observations, which inform us about the policy tasks carried out by each lowest sub-unit within the ministerial hierarchy.

Aggregating from these lowest sub-units to the level of ministries and, further, to the entire government summarises the amount of bureaucratic capacity a government possesses for each policy issue. To account for the fact that some sub-units deal with multiple topics and hence devote their resources to distinct policy issues, the aggregation procedure weights each coded policy task by the inverse of the number of tasks the sub-unit deals with. This aggregation rests on the simplifying assumption that all working units are equally well endowed and staffed. To ensure comparability across governments, the issue-wise bureaucratic capacity is expressed relative to the entire bureaucratic capacity of a government. Therefore, the resulting score can be interpreted as the percentage of a government’s total bureaucratic resources that are devoted to one specific policy issue.

Changes to the organisational structure of ministries are frequent, and often driven by policy preferences of governments or even individual ministers (Kuipers et al. Citation2021; White and Dunleavy Citation2010). However, while ministries can also change their organisational structure during a government’s term, the overwhelming majority of ministerial redesigns occurs during the formation of a new government (Sieberer et al. Citation2021). Hence, each ministry was only coded once per government, drawing on the first document published six months after the inauguration of a new government. Besides rendering the data collection manageable, this selection of cases ensures a focus on the political aspects of ministerial redesigns, in contrast to changes later in a government’s incumbency, which might rather be driven by administrative concerns. In two Danish governments – Nyrup Rasmussen IV and Fogh Rasmussen I – the allocation of portfolios was changed over the term. In these cases, only the first cabinet is retained to ensure that the distribution of bureaucratic attention, which is only measured once at the onset of a government, remains accurate.

Ministerial responsibility diffusion

Ministerial responsibility diffusion measures the extent to which responsibility for individual policy issues is concentrated in one or spread across numerous ministries of a given government. The measure is based on the bureaucratic capacity variable and is operationalised as the number of ministries per government that attend to a given policy issue. Low integer values denote policy issues where ministerial responsibility is precise, whereas high values describe contexts of diffuse responsibility. Due to the operationalisation, the variable cannot be consistently measured for policy issues for which there is no bureaucratic capacity within a government.

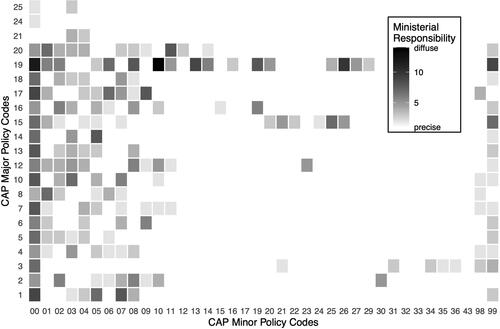

Providing an example of the prevalence of ministerial responsibility diffusion, shows whether policy issues are attended to by one or multiple ministries in Angela Merkel’s first government. The figure plots all policy issues (as defined in the CAP coding scheme) which at least one ministry attends to along two axes. The y-axis denotes 23 broader issue categories, while the x-axis shows all potential minor content codes within these larger categories. Combined, both axes span a matrix of squares, in which all potential CAP issue categories can be located. For instance, the bottom row contains all minor policy issues related to macroeconomics (CAP major policy code 1). Within this category, 1-00 contains more general discussions of the matter, 1-03 represents the issue of unemployment, and 1-04 shows ‘monetary policies’.Footnote5

Figure 2. Ministerial responsibility diffusion in Angela Merkel’s first government, 2005–2009. Each square represents one policy issue as defined by the Comparative Agenda Project’s codebook. Shading denotes the degree of responsibility diffusion running from 1 responsible ministry (light grey) to 14 responsible ministries (black).

The shading of the squares represents the extent to which ministerial responsibility is diffuse, with light grey illustrating policy issues that have been assigned to only one ministry. Examples of such policy issues include the containment of anti-government movements (2-09), energy conservation policies (8-07), as well as most issues in the rubric of health care (3-XX). In contrast, black squares such as the tax code (1-07), computer industry and internet regulation (17-09), and matters about Western Europe (19-10) represent policy issues with diffuse ministerial responsibility, which are, hence, dealt with by multiple ministries.

Issue salience

Issue salience, which in political science is customarily defined as the importance of certain policy issues, has traditionally been measured using individual responses to ‘most important problem’ survey questions (Wlezien Citation2005). Other approaches draw on media attention (Wolfe et al. Citation2013) or the prevalence of topics on social media (Barberá et al. Citation2019). Scholars more interested in institutional or partisan political actors have relied on parties’ press releases (Sagarzazu and Klüver Citation2017), parliamentary questions asked by political parties (Höhmann and Sieberer Citation2020), or coalition agreements (Klüver and Bäck Citation2019; Müller and Strøm Citation2008; Timmermans Citation2003).

However, to the best of my knowledge, there is no systematic collection of content-coded press releases, parliamentary questions or coalition agreements that matches the empirical scope and coding pattern of the present analysis. Therefore, the operationalisation of issue salience draws on content-coded party manifestos. This approach has the drawback that salience is only measured once at the onset of a government and thereafter assumed to be constant. However, relying on party manifestos to measure issue salience has a long tradition in political science and underpins one of the most widely used research projects, the Manifesto Project (Volkens et al. Citation2019). Moreover, such measures are frequently used in government studies seeking to explain coalition formation (Bäck et al. Citation2011), the drafting of coalition agreements (Joly et al. Citation2015; Moury and Timmermans Citation2013; Thomson Citation1999; Timmermans and Breeman Citation2014), and legislative policy making more generally (Borghetto et al. Citation2014; Breunig Citation2014; Breunig et al. Citation2019; Chaqués-Bonafont and Palau Citation2014).

In line with this research, the measure of issue salience used in this article draws on party manifestos that have been content-coded according to the CAP coding scheme.Footnote6 Based thereon, salience is operationalised as the relative frequency of issue mentions within a manifesto. Since the unit of analysis is policy issues within governments – and the sample largely consists of coalition governments – these salience scores are first weighted by the incumbent parties’ seat contribution and subsequently summed across all incumbent parties to estimate the government’s salience for each policy issue.

Control variables

The analysis controls for the effect of government majority status, assuming that governments controlling less than 50% of parliamentary seats generally cannot just assume a safe passage of their bills through the legislative process and, hence, are less active in drafting legislation. On a more technical matter, the analysis offsets each model for a government’s lifespan measured in days to account for the fact that governments enjoying longevity have more time to initiate legislation. Moreover, the analysis controls for unobserved variation at the level of CAP major policy clusters and countries, in which the observations are clustered.

Estimation strategy

The estimation of effects must account for important data characteristics of the dependent variable legislative activity. As the operationalisation relies on legislative counts, the potential outcome is the set of natural numbers including zero. Since the empirical distribution of legislative activity suggests substantial overdispersion () and a formal test for overdispersion yields a test statistic of z = 5646 (p < 0.001), a Poisson distribution cannot properly accommodate the empirical data. Therefore, the estimation strategy relies on a negative-binomial model, which generalises the Poisson model. A likelihood ratio test comparing the Poisson model with a corresponding negative-binomial model suggests that the latter fits the legislative activity data significantly better ( = 5743 on 1 df).Footnote7

Before proceeding to the findings, two points about the interpretation of count models are in order. Firstly, as count models do not model counts per se, but logged counts, exponentiating the coefficient facilitates a more substantial interpretation in terms of the multiplicative effect on the average number of bills parties draft (Coxe et al. Citation2009). As with virtually all generalised linear models, the coefficients denote the effect for a one-unit increase in the explanatory variable for a given specification of all other explanatory variables. For most covariates, such a unit change is an unrealistic scenario, as most observations cluster around zero. Taking the central explanatory variable, bureaucratic capacity, as an example, a mere 2.5% of all observations exceeds 0.02, which is equivalent to saying that in only 2.5% of all observations a government possesses bureaucratic capacity for a policy issue worth at least 2% of the entire government’s bureaucratic capacity. To aid interpretation, the effect size should therefore be scaled down to a meaningful increment such as a one standard deviation increase in the explanatory variable. However, as the exponentiated coefficients denote a multiplicative effect, this requires transforming the one-unit multiplicative effect as follows (with being the effect size for the desired increment

of the explanatory variable):

Secondly, the interpretation of interaction effects in generalised linear models requires a modicum of caution. In contrast to linear models, the full interaction effect does not equal the corresponding model coefficient but instead is equal to the cross-partial derivative of the expected value of the response variable (Ai and Norton Citation2003; Norton et al. Citation2004; Tsai and Gill Citation2013). Therefore, a significant interaction effect is even possible if the corresponding model coefficient equals zero, which means that statistical significance cannot be established using a conventional Wald test. Moreover, the magnitude of the interaction effect is conditional on all covariates – a fact that is generally considered when gauging simple effect sizes in generalised linear models.

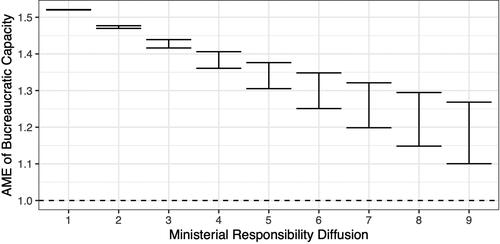

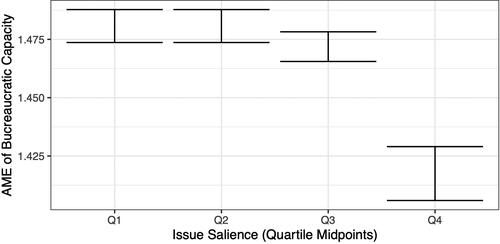

While showing the common regression tables, the presentation of the results corresponding to hypotheses 2 and 3 accounts for this complication by discussing the average marginal effect (AME) of bureaucratic capacity against different levels of the moderator (cf. and ). In essence, the AME is the marginal effect of bureaucratic capacity on legislative activity calculated for all observations at different moderator values and subsequently averaged across all observations. Therefore, the AME shows both the average magnitude of the central effect and its development across different levels of moderators.

Results

The results of the negative-binomial regression models are shown in . The first model only includes the different cluster dummies as well as the control variables. The results align with the conventional assumptions and show that both minority status and low salience induce governments to furnish fewer legislative drafts. The subsequent models test each theoretical hypothesis individually, whereas model 5 tests all postulated relationships simultaneously. All models including the variable ministerial responsibility diffusion are estimated on a sample where bureaucratic capacity is greater than zero, since the extent of diffusion cannot be consistently measured from the data in situations where not a single ministry holds any extent of bureaucratic capacity for a policy issue.

Table 1. Negative-binomial regression models.

The first hypothesis postulates that governments draft more bills in issue areas for which their ministries possess ample bureaucratic capacity. The corresponding effect of bureaucratic capacity in model 2 is 111.92 and statistically significant on the 1% level. While this statement does not carry a lot of substantive information, applying the transformation described above, the effect size can be expressed as the multiplicative effect on legislative activity induced by a 1 standard deviation increase of bureaucratic capacity. Doing so shows that the coefficient corresponds to a 75% ( rise in the number of drafted bills, given bureaucratic capacity increases by 1 standard deviation (0.005).

Moreover, the relationship can be expressed in terms of predicted counts of initiated bills. A typical Danish government – meaning that all continuous covariates are fixed at their mean, all categorical variables at their median and discrete variables at their mode – drafts about 0.27 bills per policy issue if it possesses limited bureaucratic capacities (first decile). Yet the same government possessing 1 standard deviation more bureaucratic capacity for the same policy issue is predicted to initiate about 0.24 bills more, or 0.51 bills in total. In conclusion, the analysis supports the theorised effect of bureaucratic capacity on legislative activity. If ministries attend to a policy issue, they are likely to draft legislation, and indeed governments’ legislative activity regarding a policy issue increases as their ministries possess more bureaucratic capacity.

The second hypothesis contends that, due to coordination requirements within the ministerial administration, bureaucratic capacity is a weaker driver of legislative activity if the responsibility for dealing with a policy issue is distributed across multiple ministries. Within the framework of regression analysis, this would translate to a negative interaction effect of bureaucratic capacity and ministerial responsibility diffusion. In line with this expectation, the corresponding coefficient in model 3 is −6.98 and statistically significant at the 1% level, meaning that bureaucratic capacity becomes a less potent driver of legislative activity once it is spread out across different ministries.

However, recalling the previous brief discussion about the interpretability of interaction coefficients in generalised linear models, the full interaction effect cannot directly be gauged from . Addressing this complication, plots the AME of bureaucratic capacity on legislative activity across different levels of ministerial responsibility diffusion (i.e. the number of ministries within a government that possess the capacity to deal with a given policy issue). To aid interpretation, the y-axis denotes the multiplicative effect induced by a 1 standard deviation change in the focal variable instead of the estimated coefficients on the scale of logged counts.

The errors bars in represent the 95% confidence interval around the estimated average marginal effect. The negative interaction itself is visualised by the fact that the error bars step downwards. This illustrates how the average marginal effect of bureaucratic capacity on legislative activity changes according to how much ministerial responsibility for a policy issue is diffused. If bureaucratic capacity for one individual policy issue is consolidated in just one ministry, a standard deviation increment of bureaucratic capacity lifts a government’s legislative activity by approximately 55%. Yet this AME falls below 30% in situations where there are more than six ministries in a government able to address a policy issue. These results largely align with the expectations laid out in the second hypothesis.

The last hypothesis contends that the marginal effect of bureaucratic capacity is more prevalent in issue areas that are salient to governments. However, looking at the corresponding coefficients shown in model 4 (), this statement does not appear to be supported by the data. In contrast, it appears as if salience decreases the effect of bureaucratic capacity; however, the effect is not statistically significant across all model specifications.Footnote8 Again, plots the AME of bureaucratic capacity against the quartile midpoints of salience to gauge the full interaction effect. The errors bars show that the negative interaction effect is predominantly driven by observation of highly salient policy issues. For the bottom 75% of observations, the AME of bureaucratic capacity is rather stable at a roughly 48% increase in legislative activity induced by a 1 standard deviation increment of the main explanatory variable. Only for the highest quartile does the AME drop by 6 percentage points.

At face value, it appears that the positive effect of bureaucratic capacity drops slightly once governments are strongly committed to a policy matter. Hence, these results suggest that governments strive to push through their agenda and instruct their ministries to design legislation in issue areas that, administratively, are outside of their comfort zone. In doing so, the amount of bureaucratic capacity within their ministries becomes less relevant. However, compared to the effect of ministerial responsibility diffusion discussed previously, this effect is not substantial.

There is a methodological and a theoretical ad hoc explanation speaking to this counter-intuitive finding. Regarding the former, it may be related to the hierarchical structure of the CAP coding scheme, which groups detailed policy issues into more general policy clusters. However, within each cluster, the first category is meant to capture more general discussions of the larger policy cluster. For example, within the cluster of domestic commerce (15), the first category contains more general questions related to domestic commerce (1500). In , these more general policy issues are shown in the leftmost column. Upon closer inspection, it is exactly those general categories within the larger policy clusters that tend to be the most salient ones. However, it is questionable to what extent this salience translates into higher bureaucratic capacity. The problem is that, apart from working units serving as an interface between more specialised policy units within ministries, there may be little incentive to create a lot of bureaucratic capacity ‘specialised’ to address more general matters in a policy area. Rather, ministries may rely on the combination of expertise related to several more detailed policy issues. If this was true, applying the CAP coding scheme to the ministerial bureaucracy would underestimate the bureaucratic capacity available to tackle more general matters within a larger policy cluster and therefore explain the negative interaction effect between bureaucratic capacity and salience.

More theoretically, it may be the case that governments attempt to ignore the amount of bureaucratic capacity available to them when addressing salient policy issues. Feeling pressured to live up to their own policy goals and promises, governments might be tempted to push through their policy agenda regardless of their civil servants’ capacity to professionally attend to policy issues. This pressure to increase legislative output may substantially diminish the marginal value of each additional unit of bureaucratic capacity – which is exactly what the findings show: bureaucratic capacity becomes a less potent driver of legislative activity if governments consider policy issues to be paramount. Put more bluntly, high issue salience trumps bureaucratic capacity in accounting for legislative output.

Robustness checks

All results presented above have been subjected to a series of robustness checks. The presentation of these results is largely relegated to the Supplementary Material and only summarised here briefly. Firstly, all results can be replicated modelling the response variable according to a Poisson distribution (Table A4 in the Supplementary Material).

Secondly, all models have been re-estimated replacing the country dummies with government dummies to capture unobserved variation at this level. Importantly, the results do not change substantively (Table A5 in the Supplementary Material).

Thirdly, excluding extreme observation, i.e. observations where bureaucratic capacity is below the 95% quantile, does not change the results substantively. If at all, the effects stipulated in hypotheses 1 and 2 become more pronounced, meaning that the results presented earlier may be attenuated by outlier observations (Table A6 in the Supplementary Material).

Fourthly, the robustness checks address two often violated assumptions of interaction models (Hainmueller et al. Citation2019). Except for extreme observations, there is common support for the response variable regarding bureaucratic capacity and ministerial responsibility diffusion (Figure A3 in the Supplementary Material), as well as bureaucratic capacity and issue salience (Figure A4 in the Supplementary Material). Hence, the results do not unduly extrapolate to contexts where there is no data available.

Fifthly, models 2 and 3 are re-estimated relaxing the linearity assumption commonly imposed on the interaction effect (Hainmueller et al. Citation2019). To this end, the models are fitted using a dichotomised version of the ministerial responsibility diffusion and issue salience variable. The dichotomisation simply assigns a 0 to observations that are in the bottom half of all observations within a country with respect to the moderator and a 1 otherwise. Again, the results remain essentially the same (cf. Table A7 in the Supplementary Material).

Lastly, while the fixed-effect models employed here capture unobserved heterogeneity among Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands, they still assume the hypothesised effect to be equal in all three cases. Relaxing this assumption, Table A8 in the Supplementary Material shows the results of the full model (model 5 in ) estimated on each country individually. This closer inspection yields three main takeaways. Firstly, the interaction effect of salience and bureaucratic capacity is negative within each country but remains insignificant for Denmark and Germany. Secondly, most of the main effects are robust and point in the right direction for all sampled countries. However, and lastly, ministerial responsibility distribution remains ineffectual in the Netherlands: neither the related main nor interaction effect meets conventional levels of statistical significance.

This finding speaks to the Dutch institutional setup. Recalling the previous discussion of ministerial structure in the three countries studied here, it was stressed that cohesion among Dutch ministries is comparatively low. The prime minister does not enjoy ample powers to make ministries abide by coalition guidelines, nor are there strong connections between the rather autonomous Dutch ministries (van der Meer Citation2018). Therefore, mechanisms that generally tend to harmonise government policy, such as positive inter-ministerial coordination or simple hierarchy, only exist to a minor extent in the Netherlands. Consequently, diffuse ministerial responsibility probably imposes considerably fewer transaction costs during the drafting stage and hence is less likely to dampen legislative activity.

Conclusion

This article analyses how the bureaucratic capacity of governments translates into legislation. To this end, it draws on a novel dataset describing the amount and distribution of policy-specific bureaucratic capacity within Danish, Dutch, and German governments from the mid-1990s to about 2010. This new data is subsequently used to explain governments’ legislative activity in different policy areas, which is measured as the number of bills governments draft and forward to parliament. The actual process of bill sponsorship is modelled according to a negative-binomial distribution.

As the most general result, it was found that governments that devote more bureaucratic capacity to specific policy issues are also more active in addressing these issues via legislation. Going beyond this central finding, it is found that the effect of bureaucratic capacity diminishes if there are numerous ministries with the potential to address a policy issue. Lastly, there is some tentative evidence that – against the theoretical conjecture – issue salience does not increase the effect of bureaucratic salience on legislative activity. In contrast, it appears that for highly salient policy issues bureaucratic capacity becomes a weaker driver of the number of bills governments draft. However, this finding is not robust across all model specifications.

While this article focuses on the level of government, the finding that diffuse ministerial responsibility for policy issues dampens productivity also bears interesting implications for classical models of ministerial government, which stress the rather unchallenged discretion ministers enjoy in designing policies (Laver and Shepsle Citation1994, Citation1996). Adding a party dimension would speak to previous studies criticising the notion of ministerial discretion (Dewan and Hortala‐Vallve Citation2011; Fernandes et al. Citation2016). Investigating whether the productive effect of bureaucratic capacity is particularly curtailed in situations where responsibility spans across ministries of different parties would elucidate the role of party competition next to the coordination cost argument presented here.

In this vein, while this study sought to spell out potential links between bureaucratic capacity and legislative activity by discussing various in-depth studies about the impact of civil servants on the policy-making process (Bonnaud and Martinais Citation2014; Page Citation2003), especially the restraining effect of ministerial responsibility diffusion would benefit from some case-level evidence. Here, it has been conjectured that governments are wary of the costs of bills being caught up in inter-ministerial committees. However, the quantitative analysis provided in this article cannot ascertain whether this causal explanation indeed conforms with ministers’ rationale. Going into the field and both studying minutes of meetings and interviewing decision makers in ministries could shed light on how and when parties feel comfortable instructing their civil servants to turn their policy ideas into legal language.

Moreover, the article presents tentative evidence that institutional features of the core executive moderate the stifling effect of diffuse ministerial responsibility on policy making. Running the analyses individually on each sampled country shows that responsibility diffusion is both less prevalent and impactful in the Netherlands. This finding is cautiously interpreted as being a result of the structure of the Dutch machinery of government, which consists of rather autonomous ministries with comparatively little policy cohesion (van der Meer Citation2018). Hence, potential policy disagreements between jointly responsible ministries imply fewer transaction costs and thus are less likely to stifle policy making. However, seriously investigating this institutional effect of government cohesion requires expanding the scope of this article beyond Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands.

Lastly, this article assumed that ministries must possess a modicum of corresponding capacity to draft legislation addressing a policy issue. Yet this claim is not explicitly tested on the level of individual ministries, but simply assumed on the level of governments. Given that recent studies on ministerial policy domains show how ministries regularly leave their ‘home turf’ to draft legislation within the policy areas of adjacent ministries, this might be an oversimplification (Klüser and Breunig Citation2019). Hence, future studies should investigate whether the productive effect of bureaucratic capacity also prevails within ministries and to what extent a lack or the complete absence of issue-specific capacity stifles their legislative activity. In this vein, the detailed data on bureaucratic capacity used in this article also facilitates an investigation into how far potential ministerial turf violations extend. It is imaginable that ministers of economic affairs transgress into the issue domain of colleagues responsible for social affairs. In contrast, ministers of defence, who by virtue of their portfolio have less substantial contact points with their colleagues, may be less likely to commit turf violations. Yet whether and how exactly this ‘closeness’ of different portfolios affects ministers’ likelihood to draft bills outside their bureaucrats’ issue focus remains to be researched.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (681 KB)Acknowledgements

I am grateful for comments and suggestions on previous versions of this article by Christoffer Green-Pedersen, Carsten Jensen, Ulrich Sieberer, Peter Bjerre Mortensen, and Lanny Martin. I thank Julie Bauer-Jensen, Emma Kempf, and Matthias Frey for their excellent and independent research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

K. Jonathan Klüser

K. Jonathan Klüser is a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Political Science, University of Zurich. His research interests include agenda setting and party competition, with a focus on how the involved actors behave in coalition governments. Furthermore, he researches how political actors frame and respond to the chances and challenges of digital democracies.

Notes

1 Gesetz zu Bekämpfung unerlaubter Telefonwerbung und zur Verbesserung des Verbraucherschutzes bei besonderen Vertriebsformen (http://www.bgbl.de/xaver/bgbl/start.xav?startbk=Bundesanzeiger_BGBl&jumpTo=bgbl109s2413.pdf).

2 See master codebook: https://www.comparativeagendas.net/pages/master-codebook

3 Some Danish agencies do not provide a detailed organisational structure. In those cases, the unit of study is the entire agency.

5 The data in the Danish Policy Agenda Project has been collected by Christoffer Green-Pedersen and Peter B. Mortensen with support from the Danish Social Science Research Council and the Research Foundation at Aarhus University. The data on manifestos of German parties has been collected by Christoffer Green-Pedersen and Isabelle Guinaudeau. The Dutch data has been collected by Simon Otjes.

6 For a description of all policy codes spanned by the two axes please consult the CAP online cookbook at https://www.comparativeagendas.net/pages/master-codebook.

7 Please refer to ‘model selection’ in the Supplementary Material for additional information on the modelling decision.

8 Compare different model specifications in Tables A4–A7 in the Supplementary Material.

References

- Ai, Chunrong, and Edward C. Norton (2003). ‘Interaction Terms in Logit and Probit Models’, Economics Letters, 80:1, 123–9.

- Bäck, Hanna, Marc Debus, and Patrick Dumont (2011). ‘Who Gets What in Coalition Governments? Predictors of Portfolio Allocation in Parliamentary Democracies’, European Journal of Political Research, 50:4, 441–78.

- Banks, Jeffrey S. (1989). ‘Agency Budgets, Cost Information, and Auditing’, American Journal of Political Science, 33:3, 670.

- Barberá, Pablo, Andreu Casas, Jonathan Nagler, Patrick J. Egan, Richard Bonneau, John T. Jost, and Joshua A. Tucker (2019). ‘Who Leads? Who Follows? Measuring Issue Attention and Agenda Setting by Legislators and the Mass Public Using Social Media Data’, The American Political Science Review, 113:4, 883–901.

- Baumgartner, Frank R., and Bryan D. Jones (1993). Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Baumgartner, Frank R., Christian Breunig, and Emiliano Grossman, eds. (2019). Comparative Policy Agendas: Theory, Tools, Data. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Berman, Daniel M. (1966). A Bill Becomes Law: Congress Enacts Civil Rights Legislation. 2nd ed. London: Macmillan.

- Bevan, Shaun (2019). ‘Gone Fishing: The Creation of the Comparative Agendas Project Master Codebook’, in Frank R. Baumgartner, Christian Breunig, and Emiliano Grossman (eds.), Comparative Policy Agendas: Theory, Tools, Data. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 17–34.

- Bo Smith-udvalget (2015). Embedsmanden I Det Moderne Folkestyre. 1st ed. Copenhagen: Jurist- og ØkonomforbundetsForlag.

- Bonnaud, Laure, and Emmanuel Martinais (2014). ‘Drafting the Law: Civil Servants at Work at the French Ministry of Ecology’, Sociologie du Travail, 56, e1–e20.

- Borghetto, Enrico, Marcello Carammia, and Francesco Zucchini (2014). ‘The Impact of Party Policy on Italian Lawmaking from the First to the Second Republic’, in Christoffer Green-Pedersen and Stefaan Walgrave (eds.), Agenda Setting, Policies, and Political Systems: A Comparative Approach. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 164–82.

- Breunig, Christian (2014). ‘Content and Dynamics of Legislative Agendas in Germany’, in Christoffer Green-Pedersen and Stefaan Walgrave (eds.), Agenda Setting, Policies, and Political Systems: A Comparative Approach. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 125–44.

- Breunig, Christian, Emiliano Grossman, and Tinette Schnatterer (2019). ‘Connecting Government Announcements and Public Policy’, in Frank R. Baumgartner, Christian Breunig, and Emiliano Grossman (eds.), Comparative Policy Agendas: Theory, Tools, Data. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 300–16.

- Breunig, Christian, and Tinette Schnatterer (2019). ‘Political Agendas in Germany’, in Frank R. Baumgartner, Christian Breunig, and Emiliano Grossman (eds.), Comparative Policy Agendas: Theory, Tools, Data. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 97–104.

- Budge, Ian, and Richard I. Hofferbert (1990). ‘Mandates and Policy Outputs: U.S. Party Platforms and Federal Expenditures’, American Political Science Review, 84:1, 111–31.

- Chaqués-Bonafont, Laura, and Anna M. Palau (2014). ‘Policy Promises and Governmental Activities in Spain’, in Christoffer Green-Pedersen and Stefaan Walgrave (eds.), Agenda Setting, Policies, and Political Systems: A Comparative Approach. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 183–200.

- Coxe, Stefany, Stephen G. West, and Leona S. Aiken (2009). ‘The Analysis of Count Data: A Gentle Introduction to Poisson Regression and Its Alternatives’, Journal of Personality Assessment, 91:2, 121–36.

- Dewan, Torun, and Rafael Hortala‐Vallve (2011). ‘The Three As of Government Formation: Appointment, Allocation, and Assignment’, American Journal of Political Science, 55:3, 610–27.

- DeWinter, Lieven (1993). ‘The Links between Cabinets and Parties and Cabinet Decision-Making’, in Jean Blondel and Ferdinand Müller-Rommel (eds.), Governing Together: The Extent and Limits of Joint Decision-Making in Western European Cabinets. London: St. Martin’s Press, 153–78.

- Fernandes, Jorge M., Florian Meinfelder, and Catherine Moury (2016). ‘Wary Partners: Strategic Portfolio Allocation and Coalition Governance in Parliamentary Democracies’, Comparative Political Studies, 49:9, 1270–300.

- Graw, Ansgar, and Claudia Ehrenstein (2007). ‘Parteien wollen gegen unerlaubte Telefonwerbung vorgehen’, Die Welt, January 30, 4.

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer, and Peter B. Mortensen (2019). ‘The Danish Agendas Project’, in Frank R. Baumgartner, Christian Breunig, and Emiliano Grossman (eds.), Comparative Policy Agendas: Theory, Tools, Data. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 82–9.

- Greve, Carsten (2018). ‘Public Administration Characteristics and Performance in EU28: Denmark’, in Nick Thijs and Gerhard Hammerschmid (eds.), The Public Administration in the EU 28. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 216–42.

- Hainmueller, Jens, Jonathan Mummolo, and Yiqing Xu (2019). ‘How Much Should We Trust Estimates from Multiplicative Interaction Models? Simple Tools to Improve Empirical Practice’, Political Analysis, 27:2, 163–92.

- Heppell, Timothy (2011). ‘Departmental Restructuring under New Labour’, The Political Quarterly, 82:3, 425–34.

- Höhmann, Daniel, and Ulrich Sieberer (2020). ‘Parliamentary Questions as a Control Mechanism in Coalition Governments’, West European Politics, 43:1, 225–49.

- Huber, John D. (2000). ‘Delegation to Civil Servants in Parliamentary Democracies’, European Journal of Political Research, 37:3, 397–413.

- Jensen, Lotte (2008). Vaek Fra Afgrunden: Finansministeriet Som Økonomisk Styringsaktør. Odense: University of Sothern Denmark Press.

- Joly, Jeroen, Brandon C. Zicha, and Régis Dandoy (2015). ‘Does the Government Agreement’s Grip on Policy Fade over Time? An Analysis of Policy Drift in Belgium’, Acta Politica, 50:3, 297–319.

- Jones, Bryan D., and Frank R. Baumgartner (2005). The Politics of Attention: How Government Prioritizes Problems. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Klüser, K. Jonathan, and Christian Breunig (2019). ‘Ministerial Issue Dominance in Four European Countries’, in 115th American Political Science Association’s Annual Meeting & Exhibition. Washington, DC, USA.

- Klüver, Heike, and Hanna Bäck (2019). ‘Coalition Agreements, Issue Attention, and Cabinet Governance’, Comparative Political Studies, 52:13–14, 1995–2031.

- Kuipers, Sanneke, Kutsal Yesilkagit, and Brendan Carroll (2021). ‘Ministerial Influence on the Machinery of Government: Insights on the Inside’, West European Politics, 44:4, 897–920.

- Laver, Michael, and Kenneth A. Shepsle (1996). Making and Breaking Governments: Cabinets and Legislatures in Parliamentary Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Laver, Michael, and Kenneth A. Shepsle, eds. (1994). Cabinet Ministers and Parliamentary Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Leins, Carolin (2007). ‘Kein Abschluss unter dieser Nummer’, Stuttgarter Zeitung, July 16, 8.

- Lupia, Arthur, and Mathew D. McCubbins (1998). The Democratic Dilemma: Can Citizens Learn What They Need to Know? New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Georg Vanberg (2011). Parliaments and Coalitions: The Role of Legislative Institutions in Multiparty Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mayntz, Renate, and Fritz W. Scharpf (1975). Policy-Making in the German Federal Bureaucracy. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- McCubbins, Mathew D., and Thomas Schwartz (1984). ‘Congressional Oversight Overlooked: Police Patrols versus Fire Alarms’, American Journal of Political Science, 28:1, 165–79.

- McDonald, Michael D., and Ian Budge, eds. (2005). Elections, Parties, Democracy: Conferring the Median Mandate. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Miller, Bernhard, and Wolfgang C. Müller (2010). ‘Managing Grand Coalitions: Germany 2005–09’, German Politics, 19:3–4, 332–52.

- Moury, Catherine, and Arco Timmermans (2013). ‘Inter-Party Conflict Management in Coalition Governments: Analyzing the Role of Coalition Agreements in Belgium, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands’, Politics and Governance, 1:2, 117–31.

- Müller, Wolfgang C. (1997). ‘Österreich: Festgefügte Koalitionen und Stabile Regierungen’, in Wolfgang C. Müller (ed.), Koalitionsregierungen in Westeuropa: Bildung, Arbeitsweise und Beendigung, Schriftenreihe des Zentrums für angewandte Politikforschung. Wien: Signum, 109–61.

- Müller, Wolfgang C., and Kaare Strøm (2008). ‘Coalition Agreements and Cabinet Governance’, in Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman (eds.), Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining: The Democratic Life Cycle in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 159–99.

- North, Douglass C. (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Norton, Edward C., Hua Wang, and Chunrong Ai (2004). ‘Computing Interaction Effects and Standard Errors in Logit and Probit Models’, The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 4:2, 154–67.

- Page, Edward C. (2003). ‘The Civil Servant as Legislator: Law Making in British Administration’, Public Administration, 81:4, 651–79.

- Saalfeld, Thomas, and Daniel Schamburek (2014). ‘Labels and Jurisdictions: An Empirical Critique of Standard Models of Portfolio Allocation in Political Science’, in Tapio Raunio and Hanno Nurmi (eds.), The Serious Game of Politics: Festschrift for Matti Wiberg. Tampere: Juvenes, 193–219.

- Sagarzazu, Iñaki, and Heike Klüver (2017). ‘Coalition Governments and Party Competition: Political Communication Strategies of Coalition Parties’, Political Science Research and Methods, 5:2, 333–49.

- Scharpf, Fritz W., and Matthias Mohr (1994). ‘Efficient Self-Coordination in Policy Networks. A Simulation Study’, MPIFG discussion paper, Köln.

- Sieberer, Ulrich, et al. (2021). ‘The Political Dynamics of Portfolio Design in European Democracies’, British Journal of Political Science, 51:2, 772–87.

- Stimson, James A., Michael B. Mackuen, and Robert S. Erikson (1995). ‘Dynamic Representation’, American Political Science Review, 89:3, 543–65.

- Thijs, Nick, and Gerhard Hammerschmid, eds. (2018). The Public Administration in the EU 28. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Thome, Helmut (1999). ‘Party Mandate Theory and Time-Series Analysis: A Methodological Comment’, Electoral Studies, 18:4, 569–85.

- Thomson, Robert (1999). ‘Election Pledges and Coalition Agreements in the Netherlands’, Acta Politica, 34, 302–30.

- Thomson, Robert (2001). ‘The Programme to Policy Linkage: The Fulfilment of Election Pledges on Socio–Economic Policy in the Netherlands, 1986–1998’, European Journal of Political Research, 40:2, 171–97.

- Thomson, Robert, et al. (2017). ‘The Fulfillment of Parties’ Election Pledges: A Comparative Study on the Impact of Power Sharing’, American Journal of Political Science, 61:3, 527–42.

- Timmermans, Arco (2003). High Politics in the Low Countries: An Empirical Study of Coalition Agreements in Belgium and the Netherlands. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Timmermans, Arco, and Gerard Breeman (2014). ‘The Policy Agenda in Multiparty Government: Coalition Agreements and Legislative Activity in the Netherlands’, in Christoffer Green-Pedersen and Stefaan Walgrave (eds.), Agenda Setting, Policies, and Political Systems: A Comparative Approach. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 86–104.

- Tsai, Tsung-han, and Jeff Gill (2013). ‘Interactions in Generalized Linear Models: Theoretical Issues and an Application to Personal Vote-Earning Attributes’, Social Sciences, 2:2, 91–23.

- van der Meer, Frits M. (2018). ‘Public Administration Characteristics and Performance in EU28: The Netherlands’, in Nick Thijs and Gerhard Hammerschmid (eds.), The Public Administration in the EU 28. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 755–84.

- Volkens, Andrea, et al. (2019). The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2019a. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WBZ).

- von Beyme, Klaus (1983). ‘Coalition Government in Western Germany’, in Vernon Bogdanor (ed.), Coalition Government in Western Europe. London: Heinemann Educational Books, 16–33.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, Frédéric Varone, and Patrick Dumont (2006). ‘Policy with or without Parties? A Comparative Analysis of Policy Priorities and Policy Change in Belgium, 1991 to 2000’, Journal of European Public Policy, 13:7, 1021–38.

- Wegrich, Kai, and Gerhard Hammerschmid (2018). ‘Public Administration Characteristics and Performance in EU28: Germany’, in Nick Thijs and Gerhard Hammerschmid (eds.), The Public Administration in the EU 28. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 354–88.

- Weingast, Barry R., and Mark J. Moran (1983). ‘Bureaucratic Discretion or Congressional Control? Regulatory Policymaking by the Federal Trade Commission’, Journal of Political Economy, 91:5, 765–800.

- White, Anne, and Patrick Dunleavy (2010). Making and Breaking Whitehall Departments: A Guide to Machinery of Government Changes. London: Institute for Government.

- Wlezien, Christopher (2005). ‘On the Salience of Political Issues: The Problem with “Most Important Problem”’, Electoral Studies, 24:4, 555–79.

- Wolfe, Michelle, Bryan D. Jones, and Frank R. Baumgartner (2013). ‘A Failure to Communicate: Agenda Setting in Media and Policy Studies’, Political Communication, 30:2, 175–92.