Abstract

Little is known about the staff who support MPs in their work. The literature suggests that these staff serve different important roles in democratic systems. This article compares the size of parliamentary staff in 48 countries and in 66 houses over an eight-year period. It compares three explanations of staff size, which reflect different roles they can have: firstly, that these staff serve MPs as compromise facilitators, planners and scribes. In that case, their number reflects the number of MPs. Secondly, that staff members function as information brokers and advertisers and as such act as intermediaries between the population and MPs. In that case, staff size reflects population size. And thirdly, that these staff primarily serve as a source of independent advice for MPs. In that case, staff size reflects the strength of the house they serve. Population size is found to be the dominant driver of the size of parliamentary staff.

The standard description of parliamentary staffFootnote1 is that these are an ‘invisible force’ (Fox and Hammond Citation1977) or ‘unsung heroes’ (McKee Citation2021) who ‘stay in the shadow’ (Michon Citation2008, p. 169) whose work is shrouded ‘in a degree of mystery’ (Dickin Citation2016, p. 8) and whose role is ‘typically ignored’ (Montgomery and Nyhan Citation2017, p. 745), has ‘largely been overlooked … in scholarly research’ (Christiansen et al. Citation2021, p. 477) or has at best received ‘only marginal scholarly attention’ (Egeberg et al. Citation2013, p. 495).Footnote2 This image of obscurity, however, should not be overstated. Since the mid-1970s, a small but strong cottage industry has sprung up focussed on the staff of the US Congress (Hammond Citation1984, Citation1996).

There is less research on parliamentary staff outside the US (Egeberg et al. Citation2013; Hammond Citation1984). The staff of the European Parliament is the second most studied group of parliamentary staff in the world (Becker and Bauer Citation2021; Egeberg et al. Citation2013, Citation2014; Michon Citation2008; Neuhold and Dobbels Citation2015; Neunreither Citation2002; Pegan Citation2017; Winzen Citation2011, Citation2014). A smaller number of studies have examined the staff of the parliaments of the UK (Crewe Citation2017; Geddes Citation2021; McKee Citation2021; Miller Citation2021; Ryle Citation1981) and Canada (Dickin Citation2016; Snagovsky and Kerby Citation2019). Outside of these cases, there are individual studies of parliamentary staff in Australia (Jones Citation2006), Czechia (Jágr Citation2020), Germany (Blischke Citation1981), France (Campbell and Laporte Citation1981), Italy (Romanelli Citation2016) and Thailand (Chaitep Citation2011). The comparative work is thin: the strongest comparative analyses focus on EU-focussed staff in national parliaments of EU member states (Högenauer Citation2021; Högenauer and Christiansen Citation2015; Högenauer and Neuhold Citation2015). There is also a handful of comparative studies of other aspects of parliamentary staff (Griglio and Lupo Citation2021; Laube et al. Citation2020; Meller Citation1967; Pelizzo Citation2014).

Parliamentary staff may play an important role in the political arena and deserve scholarly attention in the same way that executive staff do (Egeberg et al. Citation2013). Staff are among the most important resources politicians have at their disposal (Peters Citation2021). For instance, their staff provide an MP with information both on the basis of their own policy, political or procedural expertise and by soliciting, screening and summarising information from societal actors and scientists (Campbell and Laporte Citation1981; Egeberg et al. Citation2013; Högenauer and Neuhold Citation2015; Jágr Citation2020; Manley Citation1968; Meller Citation1967; Strøm Citation1998). Important for the balance of power in democratic systems is that they allow MPs to collect information independent from the executive: without staff to gather information, MPs can only rely on the information that the government gives them. However, staff also play an important role in other aspects of the work of MPs: MPs leave most of their day-to-day work to staff because they often have more work than there are hours in the day (McCrain Citation2018).

This article takes a comparative perspective and asks a basic question: what explains the size of parliamentary staff? Three drivers of parliamentary staff size are identified in the following way: first, the six roles staff can play in the political process are presented: advisor, scribe, information broker, advertiser, compromise facilitator and planner. Second, four different types of staff are introduced that can be identified on the basis of their principal. Next, three functionalist explanations of staff size in general are proposed. Each of these three explanations of staff size is connected to a different role that staff can have: if staff primarily serve as expert advisors to MPs, stronger parliaments may need more staff. If staff mainly serve as information brokers (that is, obtaining information from the population) or as advertisers (that is, sending information to the population), countries with a greater population need more staff. Finally, if staff mostly serve MPs in their role as scribe, planner or compromise facilitator, houses with more members will need more staff.

This article offers three key innovations to our existing knowledge on parliamentary staff. It is the first systematic study that uses parliamentary staff size as a dependent variable. Moreover, this is the first large-N comparative study of parliamentary staff, as most of the literature has been case studies. Furthermore, it develops a number of explanations of staff size (reflecting their different functions). This fills a gap in our understanding of parliamentary staff where so far this question has not been theorised. These different explanations are tested concurrently. The article brings together data from different sources to analyse the size of different types of staff as a function of population size, assembly size and parliamentary powers. This article offers a unique contribution to the literature, as it is the first to explain staff size, the first to systematically theorise its drivers and the first to study it comparatively.

Role of staff in the political process

Like MPs, their staff can play different roles in parliament (Andeweg Citation2014). Parliamentary staff play an important role in the processes of policy making, oversight and representation. The literature identifies a whole range of staff functions. Here, these are summarised in six roles, as follows.

Advisor

An MP cannot be an expert on every issue they talk about. They cannot know which solutions are possible for every issue, nor which ones are preferable (Blischke Citation1981). Therefore, staff may provide MPs with advice on their work on the basis of their own expertise on the policy, procedural or political matters: they may sketch different policy alternatives, MPs can choose from, different procedural or legal options MPs have and the political impact of these choices (Blischke Citation1981; Crewe Citation2017; Dobbels and Neuhold Citation2015; Egeberg et al. Citation2013; Högenauer and Neuhold Citation2015; Neunreither Citation2002; Pegan Citation2017). Their expertise is an important source of power and value for MPs (Peters Citation2021). This role is inherently political as this advice may reflect a staff’s judgement, biases and interests (Malbin Citation1980). Information is a crucial resource and if a parliament has more staff, then it has a larger source of information that is independent of the executive (Manley Citation1968).Footnote3 From this perspective, the smaller the staff a parliament has, the more dependent it becomes on the executive and the stronger the dominance of the executive in the political system will be.

Information broker

Information is a valuable resource in parliamentary politics (Romzek and Utter Citation1997). An important part of the work of a parliamentary staffer is to provide MPs with information (Egeberg et al. Citation2013; Fox and Hammond Citation1975; Frantzich Citation1979; Geddes Citation2021; Jágr Citation2020; Patterson Citation1970; Pegan Citation2017; Sabatier and Whiteman Citation1985). Many people, including individual citizens, interest groups and government agencies, seek to provide MPs with information. The parliamentary staff do not simply forward all this information to the MPs: staff screen, select, summarise and synthesise information (Geddes Citation2021; Högenauer and Neuhold Citation2015; Yin Citation2012). They may solicit information from experts or specific interest groups on behalf of MPs (Egeberg et al. Citation2013). As such, staff have an important role as ‘information screens’ for MPs (DeGregorio Citation1988, p. 459). The role of information broker grants staff a considerable degree of influence over MPs (Meller Citation1967). The biases of these staff members play an important role because they may affect how they filter and prioritise information (Hertel-Fernandez et al. Citation2019).

Advertisers

Staff may focus on communicating about the work of the MPs, as well as on ‘selling’ the policies of an MP, party, committee or entire parliament (Winzen Citation2011, p. 18). In many parliaments, a major role is played by the press secretaries who contact traditional media (Fox and Hammond Citation1975, Citation1977). With the rise of social media, MPs may now employ social media advisors to inform voters directly and provide them with social media posts, photos, memes and short movies.

Scribe

Staff prepare the work of an MP in parliament. They may write the text of speeches, bills, motions, oral and written questions that the MP presents in parliament (Blischke Citation1981; Crosson et al. Citation2020; Dobbels and Neuhold Citation2015; Egeberg et al. Citation2013; Fox and Hammond Citation1975). Again, their own preferences, biases and interests may shine through in this role.

Compromise facilitator

Staff may have an important role in coordinating and facilitating compromise between political decision makers (Becker and Bauer Citation2021; Egeberg et al. Citation2013; Högenauer and Neuhold Citation2015; Patterson Citation1970; Pegan Citation2017; Winzen Citation2011; Yin Citation2012). In this role, they may identify areas of agreement and disagreement in preparation of a meeting of MPs. They may represent ‘their’ member in negotiations (Patterson Citation1970). Here, they can play a steering role, pushing their own agenda (Neuhold and Dobbels Citation2015). If the process of legislating is mostly done through staff members coordinating with the staff of other MPs, the executive departments and the lawyers in the parliament’s legal department, the MP may become detached from the legislative process and it may lead to legislative outcomes that do not match up with MP preferences (Salisbury and Shepsle Citation1981; Winzen Citation2014).

Planner

Parliament is a number of intersecting calendars. The calendars of individual MPs, the calendar of the government, the calendars of committees, the calendars of PPGs and the plenary calendar, all of which need to be coordinated (Frantzich Citation1979). An important element in the work of parliamentary staff is ensuring that these calendars are synchronised. Even drafting an agenda for a parliamentary meeting is no small political feat and requires knowledge of the procedures and the preferences of MPs (Becker and Bauer Citation2021).

Staff types

In addition to the roles staff play, one can also think of the principal they answer to. One can make a fourfold distinction (Peters Citation2021; Ryle Citation1981): (1) those who work for the entire parliament as an institution and serve all MPs independently of their political colour and position (institutional staff); (2) those who work for specific committees (committee staff); (3) those who work for the parliamentary groups (PPG staff); and (4) those who work for individual MPs (personal staff). The balance between these four segments varies between countries (Christiansen et al. Citation2021). In the US Congress, nearly all staff are personal staff (Salisbury and Shepsle Citation1981). In the European Parliament, there is more balance between the size of the four different staff types (Neunreither Citation2002).

Institutional staff

Institutional staff work for the parliament as a whole. There is a range of different roles here (Blischke Citation1981; Campbell and Laporte Citation1981; Ryle Citation1981; Weiss Citation1989). Some departments play an important role in the flow of information. Many parliaments have a research service that MPs can rely on as a source of information (De Feo and Jacobs Citation2021; Jágr Citation2020). In member states of the European Union, a European department forms an important informational link to the EU level (Högenauer and Christiansen Citation2015). Institutional staff often serve longer than individual MPs and therefore they can build up a lot of expertise and experience (Romzek and Utter Citation1996). The legislative department and budgetary department advise MPs when it comes to writing legislation and estimating budgetary effects (Weiss Citation1989; Yin Citation2012). The clerks advise MPs on procedural matters, plan and coordinate parliamentary meetings and ensure that decision making follows the standing orders (Crewe Citation2017). Parliamentary clerks record every word spoken and every vote taken in parliament. The Information Department communicates the decisions made in parliament to the broader public (Neunreither Citation2002). There are also non-political staff departments that are strongly tied to parliament as a physical office.Footnote4 In European parliaments, the personnel policy of the institutional staff is merit-based (Peters Citation2021). In the US, institutional staff are selected through patronage (Salisbury and Shepsle Citation1981).

Committee staff

The committee secretariat supports the specific standing committees of parliament (Mickler Citation2017). They work closely with the committee chair (Winzen Citation2011). They can advise MPs on the basis of the subject matter or procedural expertise. When a committee is investigating a particular issue, the committee staff play an important role in managing the flow of information and drafting reports. They may also play a special role in facilitating compromise within committees. Committee staff are often recruited in the same way as institutional staff. In the US, committee staff are controlled by the majority party with minority parties specifically having a limited number of staff members assigned (Yin Citation2012).

PPG staff

The PPG staff coordinate the work of the parliamentary party groups. Within these groups they may play the role of advisor with political expertise and subject matter expertise, as well as the role of compromise facilitator. PPG staff may control the ability of MPs to communicate with journalists or use the party’s social media. PPG staff are often recruited through partisan networks. The PPG staff may be financed by parliament but employed by a separate foundation that manages these staff (Ryle Citation1981).

Personal staff

The personal staff of an MP supports them in their work. In individualised legislatures, like the US Congress, staff can play an important role in policy making (Romzek and Utter Citation1996). In PPG-dominated parliaments, the personal staff may be focussed on planning the personal daily schedule of an MP and handling their personal correspondence. In these roles, they play a major role as gatekeepers, who control access to the MP (McKee Citation2021). In polities with a district-based electoral system, part of the personal staff might be based in their districts and focus on fostering contacts with constituents (e.g. MacLeod Citation2006). The personal staff are often recruited through personal and partisan networks (Montgomery and Nyhan Citation2017).

Hypotheses

The central question in this article is: what determines the size of parliamentary staff? The expectations are formulated for parliamentary staff independent of their principal: that is for all staff independent of whether they are personal, PPG, committee or institutional staff.Footnote5 Three explanations are presented: the number of inhabitants, the number of MPs and the strength of parliament.

Each of these explanations is rooted in the theoretical perspective of functionalism. This is the notion that we can explain the existence of particular institutions by locating their significance for the wider political system (Almond Citation1965; Hollis Citation1994). Political institutions exist to meet the needs of that political system. The notion that political actors play specific roles has been linked to the functionalist approach in political science (Andeweg Citation2014): by playing a specific role, political actors perform a particular function in the system and they meet a particular need. The key assumption in this article is that the greater the demand for staff in a particular role the more staff members will be employed. In a cross-country comparison, the size of staff reflects the size of the need for this staff. As discussed above, parliamentary staff can play a number of different roles. In these roles, they can meet the different needs of actors in the system. This leads to three hypotheses based on the different roles staff can play.Footnote6

One can argue that staff primarily serve as intermediaries between the population and MPs. Staff members serve an important communicative function between MPs and the population: as information brokers they obtain information from society. The larger the society, the more information is available, and the more staff are necessary to manage this information flow. As advertisers they send information to citizens, the number of staff is also dependent on the number of outlets they need to communicate with. Larger societies have more media to communicate with. The notion that parliamentary institutions reflect population size is not uncommon in political science, it is prominently reflected in Taagepera’s (Citation1972) cube root law of parliament size.

1. Population Hypothesis: the larger the population, the larger the size of parliamentary staff.

One can also argue that staff primarily serve MPs. This is the case for their role as scribe, planner and compromise facilitator. The more MPs there are, the more staff are necessary to keep track of their schedules and to communicate between them. If staff serve primarily as intermediaries between MPs, the greater the number of MPs, the more staff are required (Högenauer and Christiansen Citation2015; Peters Citation2021). A small parliament does not need many staff members because there are few MPs to serve.

2. Assembly Size Hypothesis: the greater the number of MPs, the larger the size of parliamentary staff.

A third explanation is derived from the notion that staff are an important resource for a parliament to function independently from the executive (e.g. Manley Citation1968). If that is the case, more powerful parliaments that have a greater independent role in the political process have a greater need for staff. A parliament that is completely dominated by the government has less need for staff than a parliament that has its own independent role. This perspective places emphasis on the role of staff in providing MPs with their expert advice. Within the US Congress, there is a positive correlation between staff size and committee activity: the more work a committee does, the more staff they have (Fox and Hammond Citation1977). When it comes to EU-oriented staff in national parliaments, there is some indication that systems with greater scrutiny power employ more specifically EU staff (Högenauer Citation2021). In Central and Eastern Europe, the number of parliamentary staff was expanded when parliaments were strengthened during the transition to liberal democracy (Jágr Citation2020).

The central concept here is parliamentary strength. This is a complex, multifaceted concept (Sieberer Citation2011): parliamentary power is the institutional resource a parliament has to reach the goal of ensuring that policy outputs are in line with the preferences of the parliamentary majority. A parliament can do so by its direct influence on legislation and policy making. It can also influence policy by the ex ante selection of the ministers who can propose and implement policy. Parliaments also have ex post oversight powers over those ministers: they can monitor ministerial behaviour and sanction them if necessary.

Parliamentary power is further complicated by bicameralism. The power of a higher house is also a complex concept. Russell (Citation2013), who based her work on Lijphart (Citation2012), identified three dimensions of higher house power: their formal legislative power (which can be symmetrical or asymmetrical to the lower house); the congruence in their composition to the lower house (which allows for different outcomes of decision making to the lower house); and their election method, where direct election grants them legitimacy.

In general, the expectation is that the more powerful a (house of) parliament, the more staff it needs to perform its function.

3. Parliamentary Strength Hypothesis: the stronger a house of parliament is, the larger the size of its parliamentary staff.

Methods

This section discusses the data necessary to measure the dependent variable (staff size), the independent variables and method of analysis. This article limits itself to countries with similar levels of democratic and economic development. Specifically, it examines the so-called Twelve Plus group in the Inter-Parliamentary Union, which are: 48 parliaments in Europe, Canada and the US in North America;Footnote7 Australia and New Zealand in Oceania; and Turkey, Israel and Cyprus in Asia. The countries are listed in .

Table 1. Overview.

Dependent variable

There is no dataset that lists all the different types of staff (e.g. institutional, committee, PPG and personal staff) of a large number of houses of parliament in a comprehensive way. There are two datasets available that each have their own limitations, in particular where it comes to the kinds of staff that they cover. This article will employ both in order to get a grasp of the drivers of the number of different kinds of staff.

The first source of data is the IPU (Interparliamentary Union Citation2021). The IPU has data on the size of parliamentary staff for 43 of the 48 countries studied here. The IPU, however, only offers one number for the staff of each house.Footnote8 This data is available for multiple years. The second dataset is Rozenberg and Tsaireli (Citation2016). They have compiled information on a wide range of aspects of European lower houses or unicameral parliaments around 2015. They specifically include the number of institutional and committee staff, on the one hand,Footnote9 and the number of personal and PPG staff members on the other.Footnote10 This is available for 31 (institutional and committee staff) and 22 (personal and PPG staff) countries for a single year. Table A1 in the online appendix shows that the institutional and committee staff from Rozenberg and Tsaireli (Citation2016) come closest to a one-on-one relationship with the IPU’s reported data. This indicates that the IPU data mainly encompass institutional and committee staff.

Independent variables

Four different independent variables are employed: population size, parliament size and parliamentary strength of lower houses and of upper houses. For the population hypothesis, the UN’s estimate of population per country with a one-year lag is used (UN Population Division Citation2019).Footnote11 For the parliamentary size hypothesis, the number of higher or lower house members from the Interparliamentary Union (Citation2021) is employed.

For the parliamentary strength hypothesis, two indicators are used: one for lower houses and one for higher houses. The first is an index made up of measures from the Varieties of Democracy project. This is an expert coding consortium employing a multifaceted approach to democracy (Coppedge et al. Citation2021; Pemstein et al. Citation2021). Their dataset includes three items on ex post oversight.Footnote12 These three items form a strong scale (H = 0.76). This data is available yearly for 44 parliaments; it is included with a one-year lag. This data is chosen because of its comprehensive coverage and because it reflects the actual exercise of power instead of merely the constitutional rights a parliament has. The online appendix looks at four alternative measures: one measure comes from the Democracy Barometer (Bühlmann et al. Citation2012).Footnote13 It measures the balance between the executive and legislative powers. This measure reflects both the constitutional provisions for legislative ex post and ex ante control powers that parliament has in relation to an executive and the constitutional provision for checks that the executive has over the parliament. This measure has the drawback that it only looks at a parliament’s constitutional rights instead of the actual exercise of power.Footnote14 Three of the other alternative measures come from Sieberer (Citation2011). These specifically tap into agenda control, ex ante and ex post control.Footnote15 The drawback of these measures is that they have smaller geographic coverage: it is only available for 15 West European democracies (listed in Table A2 in the online appendix). They are not employed in the analysis with Rozenberg and Tsaireli (Citation2016) data because the N dips below acceptable levels. It is available for a single year (2006). This data is assumed to be valid for the entire period. As can be seen in online appendix Table A3, the five measures tap into different elements of parliamentary power and are not strongly correlated to each other.

Table 2. Regression results.

The power of higher houses is a second measure. The coding is based on Lijphart’s (Citation2012) classification of bicameral strength with my own additions for the missing countries (based among others on Drexhage Citation2015). This data is available for all 17 bicameral systems (see ). These three items form a barely sufficient scale (H = 0.31), which is employed in the article. The online appendix looks at alternative measures: specifically, the three items are applied separately, as Russell (Citation2013) argues that these are separate and they do not form a strong scale. In addition, Lijphart’s (Citation2012) own expert assessment is used (available for 13 bicameral systems, listed in Table A2 in the online appendix). All these items of higher house power are significantly related (see Table A4 in the online appendix). Bicameral strength is assumed to be constant during the studied period. Table A5 in the online appendix shows the descriptives of all the variables.Footnote16

Method of analysis

The guidelines by Green (Citation1991) for the number of cases required in a regression model with a particular number of predictors are used here.Footnote17 the Rozenberg and Tsaireli (Citation2016) data for every lower house or unicameral parliament is a single case, therefore OLS is employed for this data. The data for PPG and personal staff covers so few cases that even simple regressions fall beneath the bar provided by Green (Citation1991). Therefore, the regressions here should be interpreted with great caution. In the IPU data, lower and higher houses are included separately and data is included for multiple years. Two sets of multilevel regression models are presented: one for lower houses and one for higher houses. In each of these models, the country*year dyad is level one and country is level two. Given the relationship between parliament size and population size (Taagepera Citation1972),Footnote18 one should approach models with both variables with some caution. Particularly when the number of cases is low, significance may be low and a better indicator of the value of the inclusion of a particular variable is the (difference in) explained variance.

Descriptive results

gives an overview of the number of staff per country in four clusters:

Lower house institutional and committee staff from Rozenberg and Tsaireli (Citation2016)

Lower house personal and PPG staff from Rozenberg and Tsaireli (Citation2016)

Lower house institutional and committee staff from the Interparliamentary Union (Citation2021)

Upper house institutional and committee staff from the Interparliamentary Union (Citation2021)

Rozenberg and Tsaireli offer data for European parliaments from a single year per country between 2012 and 2015. Their dataset has information for 31 houses/parliaments on institutional and committee staff and for 22 houses/parliaments on personal and PPG staff. An average parliament has around 700 institutional and committee staff members. The smallest institutional and committee staff can be found in micro-states like Malta and the largest can be found in Turkey. The average lower house has about 550 members of PPG and personal staff. Iceland has the least personal and PPG staff and Germany the most.

The IPU data covers more countries outside of Europe and has data on 39 lower houses. The average lower house staff is around 850 people. As already well established in the literature, the US House of Representatives has the largest staff for any lower house (Peters Citation2021).Footnote19 The fewest staff members can be found in micro-states such as Liechtenstein. The average higher house has 700 members of staff. The US Senate has the largest staff of any higher house. The smallest higher house staff can be found in Austria. The indication appears to be that population size is a strong predictor: the lower house of the most populous country in (the United States of America) has more staff than the lower houses of the 28 countries with the least population combined.

Regression results

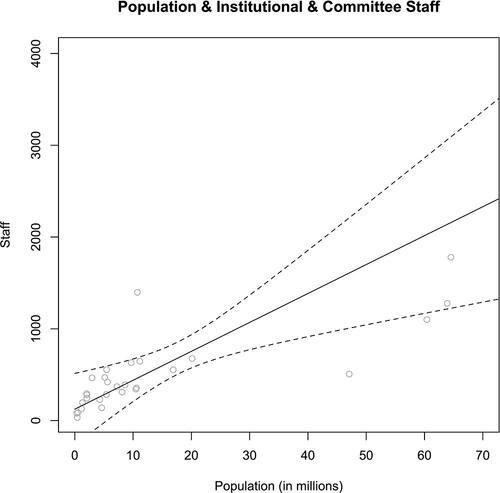

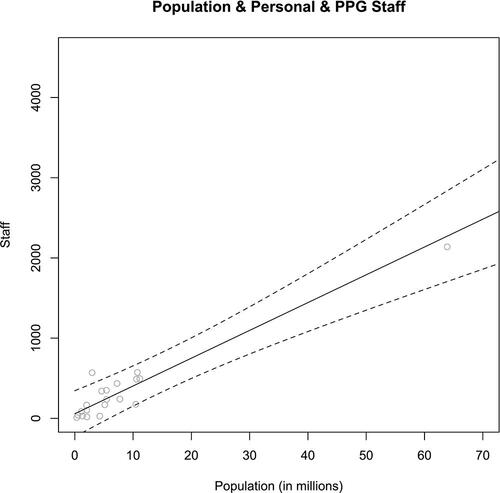

presents four regressions, one for each of the dependent variables. The models for the IPU data on lower and higher houses have measures for population size, the number of house members of the specific house and its power. The models using the Rozenberg and Tsaireli (Citation2016) data have far fewer cases and therefore look at fewer predictors. The model for institutional and committee staff looks at two variables (house size and population) and the model for personal and PPG staff only looks at one variable (population).

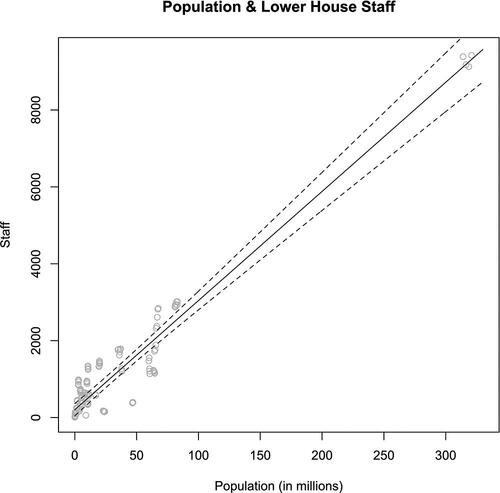

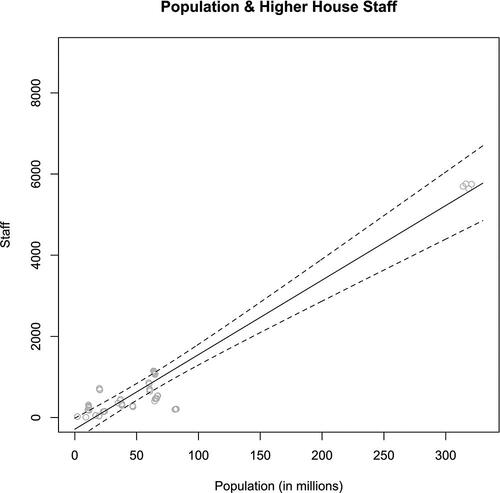

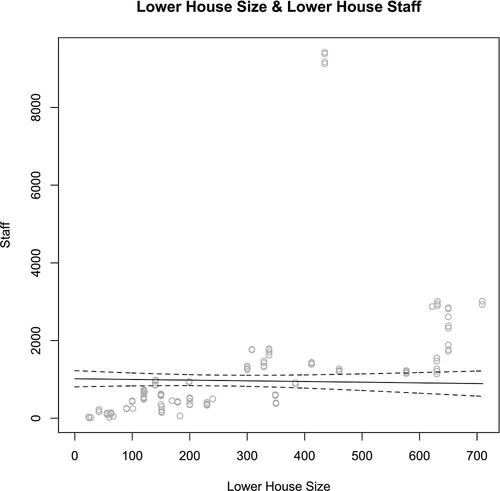

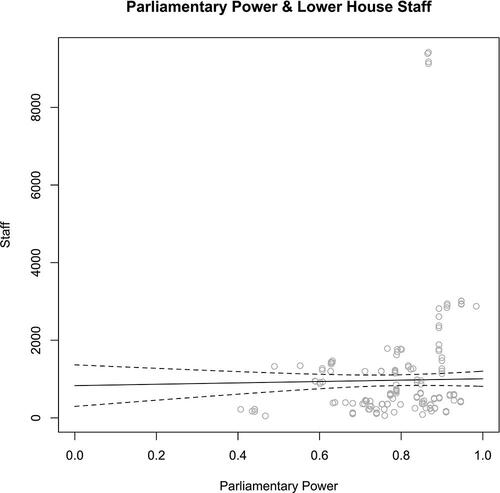

All these models point in one direction: population size is a positive, strong and significant predictor of the numbers of staff members in every model. visualise this relationship. Both Models 1 and 3, which are concerned with institutional and committee staff (based on IPU and Rozenberg and Tsaireli (Citation2016) data), predict about 30 members of staff per 1 million inhabitants. For higher houses, the relationship is less steep (18 members of staff per 1 million inhabitants). The results for personal and PPG staff should be treated with great caution, but point in the same direction.

In these regressions, there is no evidence that the number of members of a house is related to the size of the staff. Rather, if anything, the insignificant coefficients in Models 1 and 3 (both concerning lower house institutional and committee staff) are negative. visualises this relationship on the basis of Model 1. There is no evidence that parliamentary power is related to the size of staff (see and Models 1 and 2).

The online appendix further tests the robustness of these results, including different measures of parliamentary power, additional control variables, different set-ups for the analyses with a limited number of cases and without outliers. These point in the same direction: population size is the best predictor of parliamentary size. Tables A6 and A7 in the online appendix further analyse lower house staff. Four additional measures of parliamentary power are included. These are drawn from different datasets and tap into different aspects of parliamentary power. These are not significant predictors of parliament size (in one case the relationship is significant at the 0.1 level but in the opposite direction). These models also show that the relationship between population size and the size of parliamentary staff persists when additional controls are included. The cube root of the population is used as an alternative for population size, and the AICs of these models are 40 points higher than the AICs in the models using the actual population This means there is no support that these are a better fit for the data (Burnham and Anderson Citation2004). Finally, excluding the US House of Representatives (a clear outlier in terms of population size) does not affect the results.

Tables A8 and A9 in the online appendix present additional regression models concerning the size of higher house staff looking at both the effect of the variables studied individually and other measures of higher house power. These models show that in a simple model, the number of higher house members predicts the size of the higher house staff. The models including population size have an AIC that is 20 to 40 points lower, meaning that the models that only include higher house members have essentially no support for being better than the models with population size. The additional measures of higher house power are not significantly related to the size of the higher house staff. Excluding the US Senate (a clear outlier in terms of population size) does affect the results predicting higher house staff. In that case, there is only one significant predictor and only at the 0.1 level and that is the number of higher house members. This indicates that the main result presented above for higher houses should be treated with some caution as one outlier plays an important role.

Table A10 in the online appendix presents additional models concerning institutional and committee staff using the Rozenberg and Tsaireli (Citation2016) data. Because of the lower number of cases, one can only run models with two dependent variables. Moreover, the Sieberer’s (Citation2011) alternative measures of parliamentary power are not used here because the N dips below acceptable levels. These models show that population is a stronger predictor of staff size than the number of house members. The R-squared values of models that exclude the population as a predictor, however, are markedly lower than the models that include it. Moreover, in Model 3, where both lower house members and population are included, the relationship between staff size and house size is no longer significant. Also, none of the measures of parliamentary power are significantly related to the size of institutional and committee parliamentary staff. A final model examines whether institutional and committee staff are a function of PPG staff, controlling for population size. Note here that these models should be interpreted with caution because the N fall beneath established rules of thumb for analysis and also because both staff sizes are cotemporaneous, which makes it difficult to disentangle causality. The models tentatively show that a larger personal and PPG staff is related to having a smaller institutional and committee staff. This indicates that one staff may be substituted with another. For all these analyses, the main conclusion is that population size is the strongest predictor of institutional and committee staff.

Finally, Table A11 in the online appendix shows additional models with personal and PPG staff. The N in all these models is lower than Green (Citation1991) advises. Therefore, the models should be interpreted with caution. Separate regressions show significant relationships between both staff size and number of lower house members and population size. The R-squared is comparable for the two models but it is slightly higher for population, indicating that this is the stronger predictor. There is also a negative relationship for one of the two measures of parliamentary power (and a non-significant relationship for the other). The substitution pattern that was seen for institutional and committee staff can be found here as well: a larger institutional and committee staff is related to having a smaller personal and PPG staff. All of this sustains the interpretation presented in the article that population size is the key predictor of staff size, but the evidence here is weaker than for institutional staff.

Conclusion

There is considerable support for the notion that population predicts the staff size of parliamentary staff. This evidence is strongest for lower houses and institutional and committee staff. From the functionalist perspective in this article, this has an implication for the role that staff primarily play in democratic systems. As population size is the strongest predictor of parliamentary staff, the role of staff is mainly as information broker or advertiser. The larger the society, the greater the staff required to obtain information from citizens and to send information to citizens. Parliamentary staff primarily serve as conveyor belts between MPs and citizens. Population size is a stronger explanation than the number of MPs. If this had been the key predictor of staff size, then parliamentary staff would primarily serve as assistants to MPs. This relationship is not present in the data if one controls for population size. Population size is also a better explanation than parliamentary power. If this were to be the key explanation, then more powerful parliaments should have more staff. There is no evidence for this.

This last element is striking, in particular given the emphasis in the literature on the relationship between the size of staff and the power of parliament to obtain information independent from the executive. There are three possible explanations for this: the first reason may be that what is important for the collection of information is the size of the society that the MPs interact with rather than independence from the executive. In a micro-state like Liechtenstein fewer staff members are necessary to connect with all the relevant actors than in a medium-sized country like Denmark or a large country like the US. The second reason may be that the measures of parliamentary power employed do not reflect the actual scope of parliamentary power. Yet, in the online appendix a large number of different measures of parliamentary power were tested, which were all unrelated to staff size. Finally, it may be the case that the number of staff is not identical to the quality of staff; a single experienced expert may be a more valuable resource than 10 employees without experience or expertise (Crosson et al. Citation2020; Högenauer and Christiansen Citation2015; Peters Citation2021).

A key limitation of this study is that there is only information about the different kinds of staff in a very limited timeframe and only for two instead of four types of staff. Future research may want to examine more precisely what the drivers are for the four different kinds of staff more specifically, and obtain data over time about their number. Some evidence has been found in this study that the size of PPG and personal staff on the one hand and institutional and committee staff on the other are negatively related: that is, parliaments that have more of the one, have less of the other. This implies that staff are in part substitutable. Conceptually this makes sense: their roles partially overlap as well. If one has an extensive PPG advisory staff, there is less need for an extensive committee advisory staff as well. Future research may want to investigate this relationship further.

This article only analysed staff in Western democracies. These are all mid- to high-income countries and all of them are democracies. This allowed for only a limited test of the predictive power of parliamentary power. It may be that in an autocratic regime where parliament only rubberstamps legislation and is not an arena for serious debates or a venue for policy making, the staff do not neatly line up with population. Therefore, it may be useful to look outside the Western world. Note, however, that in this analysis the data availability for countries with less stable democratic institutions was already lower than in the most stable democracies.

This article has analysed staff over the period of one decade. One should note here that the strongest expansion of parliamentary staff occurred between the 1940s and the 1970s. Parliamentary staff in Western democracies developed from minimalistic enterprises to much larger and much more professional operations (Blischke Citation1981; Campbell and Laporte Citation1981; Dickin Citation2016; Fox and Hammond Citation1975; Griglio and Lupo Citation2021; Hammond Citation1984; Jones Citation2006; Patterson Citation1970; Ryle Citation1981; Sidlow and Henschen Citation1985). This period coincides with a number of societal changes: population growth, but also major economic growth and the expansion of the government. Future research may want to examine the growth of parliamentary staff over a longer period to uncover more precisely what drives staff size over time.

Finally, this article employed a functionalist framework to provide a first-order explanation of the size of parliamentary staff. The notion is that the need for staff explains the size of the staff. This neglects the role of political actors, constrained by political institutions, to respond to changes in the demand for staff. Future research, in particular research taking a historical perspective, may want to pay particular attention to the motivations of the actors when deciding to expand (or contract) staff size and the institutional constraints under which they function.

The key insight of this study is the examination of staff size outside of the US case, which has thus far received the most attention. It may be useful to examine the position of these staff in greater detail. The US model, with a highly personalised staff structure, appears to be an exception. Comparative work may want to examine the balance between institutional, committee, PPG and institutional staff. The US literature offers fascinating questions that may be studied usefully outside the confines of the Capitol: the norms and values that govern their work, the reasons for taking and leaving staff work, the balance between genders and the presence of marginalised groups, the way staff process information and the biases they have. All in all, this article has taken one small step in the comparative study of parliamentary staff, and future research is necessary to make a greater leap.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (136 KB)Acknowledgements

This paper was presented at the ECPR Standing Group on Parliaments 1–2 July 2021. I would like to thank the participants, in particular Stefanie Bailer, as well as the anonymous reviewers of this journal for their comments and Niki Haringsma for his editorial advice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Simon Otjes

Simon Otjes is Assistant Professor of Dutch Politics at Leiden University and researcher at the Documentation Centre Dutch Political Parties of Groningen University. His research focuses on parliaments, parties and party systems. He has previously published in the American Journal of Political Science, European Journal of Political Research and Party Politics. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 The term ‘parliamentary staff’ is used here instead of the term ‘legislative staff’ because the latter may suggest that these staff are primarily occupied with legislation.

2 This lack of visibility is actually a deep norm among parliamentary staff (Romzek and Utter Citation1997).

3 The same is true with regard to MPs’ independence from interest groups (Peters Citation2021), in part also because the institutional and committee staff of parliaments are not the focus of lobbyists (Becker and Bauer Citation2021).

4 This includes the IT Department which keeps parliament online, the Art Department which manages the art that the parliament displays, the Refreshments Department which provides MPs and their staff with food and drink, the HR Department which manages the employment of all the other staff, the Finance Department which keeps the financial side of parliament running, the Security Department which ensures the safety of the MPs and their staff and the Housekeeping Department which ensures that parliament is cleaned and maintained.

5 These mechanisms only apply to political staff, the size of non-political staff (see note 4) is likely to be a function of staff size itself: say a parliament has 200 people working there in political roles and therefore it needs 10 members of non-political staff (one per every 20 staff members). Now the parliament decides to double the political staff: it will need 20 members of non-political staff (still one per 20 people). But then it will actually need a 21st non-political staff member (as there now are 20 members of political staff).

6 In political science, functionalism has been criticized by political institutionalists because it neglects the role that political actors with specific motivations in specific institutional settings play in bringing about this match between societal needs and institutional choices (Hall and Taylor Citation1996). As such, it can only be a first-order explanation of societal phenomena and further deeper research may be useful to study the specific institutional design choices specific actors make.

7 The US has left the IPU but used to be a member of the Twelve Plus group and therefore is included here.

8 The data specifically concerns ‘number of permanent staff employed by parliament (full time equivalent (FTE) positions) and excludes PPG or personal assistants that work inside of parliament but are employed by other entities, such as the parliamentary party groups’ (Interparliamentary Union Citation2021).

9 This data concerns ‘the absolute number of people permanently employed by the assembly full-time or part-time, excluding MPs and PPGs’ assistants’ (Rozenberg & Tsaireli (Citation2016).

10 The specific question was: ‘Here you should indicate the total number of permanent staff of MPs and PPGs. Here we are interested in parliamentary officials permanently employed by the assembly, excluding clerks, parliamentary civil servants and secretaries’ (Rozenberg & Tsaireli (Citation2016).

11 The online appendix pursues the possibility of a cube-root relationship between staff and population size.

12 (1) The extent to which parliament questions executive officials in practice; (2) the likelihood of parliament investigating the executive if it engaged in unconstitutional, illegal or unethical activity as well as parliament writing an unfavourable report if it found evidence for this; (3) and the extent to which opposition parties are able to exercise oversight and investigatory functions in parliament against the wishes of the governing party or coalition.

13 Low values indicate unbalanced checks in favour of either the executive or the legislative, whereas high values are assigned when there is a balance in checks between the legislative and the executive branches. This measure is available yearly between 1990 and 2017 for 41 countries. Given the stability of the systems, the data for 2017 is assumed to apply to other years. This is included with a one-year lag.

14 For instance, the Democracy Barometer rates Germany as among the systems where parliament is the weakest, most likely because the constructive vote of no confidence is necessary there. This score is in stark contrast with the image (that also emerges from the V-Dem data) of the Bundestag as one of the most powerful parliaments in Europe in day-to-day practice.

15 On the basis of a factor analysis of the formal powers that parliaments have over matters like the plenary agenda, appointment of cabinet officers and oversight structures, Sieberer created three factors related to direct influence over policy making, ex ante powers (over the selection of political officers) and ex post powers (oversight over the executive). These are examined separately. The first of these factors captures considerably more variance than the others. Given their multidimensional nature, they measure more aspects of parliamentary power compared to the V-Dem measure.

16 In the online appendix, in the analyses where the N allows this, control variables are included. Högenauer and Christiansen (Citation2015) look at GDP per capita. The assumption is that richer countries may have more wealth to spend on parliament. GDP per capita is included (with a one-year lag) from the UN Statistics Division (Citation2021). The size of the public sector is also taken into account: when the public sector is larger, more staff may be necessary to oversee it. The size of the public sector as a share of total GDP is calculated on the basis of data from the OECD (Citation2021). This data is also lagged by one year. The multilevel structure is also taken into account: federal systems or systems where the government is strongly decentralized may have less need for staff at the federal level than in unitary states because most of the policy is made at the federal level. The OECD dataset also allows the share of government expenditure by central government as opposed to regional and local governments to be measured. EU membership may also affect the number of staff. Parliaments employ EU staff to oversee this level of government (Högenauer and Christiansen Citation2015; Högenauer and Neuhold Citation2015).

17 When expecting a large effect size, 24 cases are necessary for 1 predictor, 30 cases for 2 predictors, 35 cases for three predictors, 39 cases for 4 predictors, 42 cases for 5 predictors, 46 cases for 6 predictors and 48 cases for 7 predictors.

18 The correlation between parliament size and population size is 0.59 (significant at the 0.01 level) for all countries in the data set, but 0.93 for the Rozenberg and Tsaireli (Citation2016) data.

19 House members have on average 16 personal staffers on average and senators on average 40 (Peters Citation2021). Yet there is also a considerable institutional staff: the Library of Congress employs more people than many legislatures (Pelizzo Citation2014).

References

- Almond, Gabriel A. (1965). ‘A Developmental Approach to Political Systems’, World Politics, 17:2, 183–214.

- Andeweg, Rudy B. (2014). ‘Roles in Legislatures’, in Shane Martin, Thomas Saalfeld, and Kaare Strøm (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Legislative Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 267–86.

- Becker, Stefan, and Michael W. Bauer (2021). ‘Two of a Kind? On the Influence of Parliamentary and Governmental Administrations’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 27:4, 494–512.

- Blischke, Werner (1981). ‘Parliamentary Staffs in the German Bundestag’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 6:4, 533–58.

- Bühlmann, Marc, Wolfang Merkel, Lisa Müller, and Bernhard Weßels (2012). ‘The Democracy Barometer: A New Instrument to Measure the Quality of Democracy and Its Potential for Comparative Research’, European Political Science, 11:4, 519–36.

- Burnham, Kenneth P., and David R. Anderson (2004). ‘Multimodel Inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in Model Selection’, Sociological Methods & Research, 33:2, 261–304.

- Campbell, Stanley, and Jean Laporte (1981). ‘The Staff of the Parliamentary Assemblies in France’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 6:4, 521–31.

- Chaitep, Wannapat, Simon Simn Usherwood, and Mark Olssen (2011). ‘The Role of Parliamentary Secretariat Staff in Supporting International Diplomatic Duties of Parliamentarians (Case Study: Thai Senate)’, Paper presented at the Parliamentary Conference: Assisting Parliamentarians to Develop Their Capacities, Bern.

- Christiansen, Thomas, Elena Griglio, and Nicola Lupo (2021). ‘Making Representative Democracy Work: The Role of Parliamentary Administrations in the European Union’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 27:4, 477–93.

- Coppedge, Michael, et al. (2021). “V-Dem [Country–Year/Country–Date] Dataset v11.1” Varieties of Democracy Project. Retrieved from https://www.v-dem.net/en/data/archive/previous-data/v-dem-dataset/

- Crewe, Emma (2017). ‘Magi or Mandarins? Contemporary Clerkly Culture’, in Paul Evans (ed.). Essays on the History of Parliamentary Procedure: In Honour of Thomas Erskine May. Bloomsbury: Bloomsbury Publishing, 45–68.

- Crosson, Jesse M., Geoffrey M. Lorenz, Craig Volden, and Alan E. Wiseman (2020). ‘How Experienced Legislative Staff Contribute to Effective Lawmaking’, in Timothy M. LaPira, Lee Drutman, and Kevin R. Kosar (eds.). Congress Overwhelmed: The Decline in Congressional Capacity and Prospects for Reform. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 209–24.

- De Feo, Alfredo, and Francis Jacobs (2021). ‘The European Experience of Parliamentary Administrations in Comparative Perspective’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 27:4, 554–76.

- DeGregorio, Christine (1988). ‘Professionals in the US Congress: An Analysis of Working Styles’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 13:4, 459–76.

- Dickin, Daniel (2016). ‘Organizing the Halls of Power: Federal Parliamentary Staffers and Members of Parliament’s Offices’, Canadian Parliamentary Review, 39:2, 9–16.

- Drexhage, Betty (2015). Bicameral Legislatures: An International Comparison. The Hague: Ministry of Home Affairs and Kingdom Relations.

- Egeberg, Morten, Åse Gornitzka, and Jarle Trondal (2014). ‘People Who Run the European Parliament: Staff Demography and Its Implications’, Journal of European Integration, 36:7, 659–75.

- Egeberg, Morten, Åse Gornitzka, Jarle Trondal, and Mathias Johannessen (2013). ‘Parliament Staff: Unpacking the Behaviour of Officials in the European Parliament’, Journal of European Public Policy, 20:4, 495–514.

- Fox, Harrison W., and Susan W. Hammond (1975). ‘The Growth of Congressional Staffs’, Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science, 32:1, 112–24.

- Fox, Harrison W., and Susan W. Hammond (1977). Congressional Staffs: The Invisible Force in American Lawmaking. New York: The Free Press.

- Frantzich, Stephan (1979). ‘Who Makes Our Laws? The Legislative Effectiveness of Members of the US Congress’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 4:3, 409–28.

- Geddes, Marc (2021). ‘The Webs of Belief around ‘Evidence’ in Legislatures: The Case of Select Committees in the UK House of Commons’, Public Administration, 99:1, 40–54.

- Green, Samuel B. (1991). ‘How Many Subjects Does It Take to Do a Regression Analysis’, Multivariate Behavioral Research, 26:3, 499–510.

- Griglio, Elena, and Nicola Lupo (2021). ‘Parliamentary Administrations in the Bicameral Systems of Europe: Joint or Divided?’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 27:4, 513–34.

- Hall, Peter A., and Rosemary C. Taylor (1996). ‘Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms’, Political Studies, 44:5, 936–57.

- Hammond, Susan W. (1984). ‘Legislative Staffs’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 9:2, 271–317.

- Hammond, Susan W. (1996). ‘Recent Research on Legislative Staffs’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 21:4, 543–76.

- Hertel-Fernandez, Alexander, Matto Mildenberger, and Leah C. Stokes (2019). ‘Legislative Staff and Representation in Congress’, American Political Science Review, 113:1, 1–18.

- Högenauer, Anna-Lena (2021). ‘The Mainstreaming of EU Affairs: A Challenge for Parliamentary Administrations’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 27:4, 535–53.

- Högenauer, Anna-Lena, and Thomas Christiansen (2015). ‘Parliamentary Administrations in the Scrutiny of EU Decision-Making’, in Claudia Hefftler, Christine Neuhold, Olivier Rozenberg, and Julie Smith (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of National Parliaments and the European Union. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 116–32.

- Högenauer, Anna-Lena, and Christine Neuhold (2015). ‘National Parliaments after Lisbon: Administrations on the Rise?’, West European Politics, 38:2, 335–54.

- Hollis, Martin (1994). The Philosophy of Social Science: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Interparliamentary Union (2021). Parline. Global Data on National Parliaments, available at: https://data.ipu.org/ (accessed 1 June 2021).

- Jágr, David (2020). ‘Parliamentary Research Services as Expert Resource of Lawmakers. The Czech Way’, Journal of Legislative Studies.

- Jones, Kate (2006). ‘One Step at a Time: Australian Parliamentarians, Professionalism and the Need for Staff’, Parliamentary Affairs, 59:4, 638–53.

- Laube, Stefan, Jan Schank, and Thomas Scheffer (2020). ‘Constitutive Invisibility: Exploring the Work of Staff Advisers in Political Position-Making’, Social Studies of Science, 50:2, 292–316.

- Lijphart, Arend (2012). Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- MacLeod, Peter (2006). ‘How to Organize an Effective Constituency Office’, Canadian Parliamentary Review, 29:1, 9–12.

- Malbin, Michael J. (1980). Unelected Representatives: Congressional Staff and the Future of Representative Government. New York: Basic Books.

- Manley, J. F. (1968). ‘Congressional staff and public policy-making: The joint committee on internal revenue taxation’, The Journal of Politics, 30:4, 1046–67.

- McCrain, Joshua (2018). ‘Revolving Door Lobbyists and the Value of Congressional Staff Connections’, The Journal of Politics, 80:4, 1369–83.

- McKee, Rebecca (2021). Who Are the ‘Unsung Heroes’ of Westminster? Results from a Survey of MPs Staff. Constitution Unit April 30, 2021, available at: https://constitution-unit.com/2021/04/30/who-are-the-unsung-heroes-of-westminster-results-from-a-survey-of-mps-staff/ (accessed 1 June 2021).

- Meller, Norman (1967). ‘Legislative Staff Services: Toxin, Specific, or Placebo for the Legislature’s Ills’, The Western Political Quarterly, 20:2, 381–9.

- Michon, Sébastien (2008). ‘Assistant Parlementaire au Parlement Européen: Un Tremplin Pour Une Carrière Européenne’, Sociologie du travail, 50:2, 169–83.

- Mickler, Tim A. (2017). ‘Committee Autonomy in Parliamentary Systems-Coalition Logic or Congressional Rationales?’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 23:3, 367–91.

- Miller, Cherry M. (2021). ‘The House Service: ‘Servants’ and ‘Stewards’, in Cherry M. Miller (ed.). Gendering the Everyday in the UK House of Commons: Beneath the Spectacle. New York: Springer, 183–223.

- Montgomery, Jacob M., and Brendan Nyhan (2017). ‘The Effects of Congressional Staff Networks in the US House of Representatives’, The Journal of Politics, 79:3, 745–61.

- Neuhold, Christine, and Mathias Dobbels (2015). ‘Paper Keepers or Policy Shapers? The Conditions under Which EP Officials Impact on the EU Policy Process’, Comparative European Politics, 13:5, 577–95.

- Neunreither, Karlheinz (2002). ‘Elected Legislators and Their Unelected Assistants in the European Parliament’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 8:4, 40–60.

- OECD (2021). Consolidated Government Expenditure as Percentage of GDP, available at: https://www.oecd.org/tax/federalism/fiscal-decentralisation-database/ (accessed 1 June 2021).

- Patterson, Samuel C. (1970). ‘The Professional Staffs of Congressional Committees’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 15:1, 22–37.

- Pegan, Andreja (2017). ‘The Role of Personal Parliamentary Assistants in the European Parliament’, West European Politics, 40:2, 295–315.

- Pelizzo, Riccardo (2014). ‘An International Comparative Study of the Sources of Parliamentary Information and Support for Legislators’, Journal of the South African Legislative Sector, 1:1, 97–108.

- Peters, B. Guy (2021). ‘Bureaucracy for Democracy: Administration in Support of Legislatures’, Journal Legislative Studies, 27:4, 577–94.

- Pemstein, Daniel, et al. (2021). ‘The V-Dem Measurement Model: Latent Variable Analysis for Cross-National and Cross-Temporal Expert-Coded Data’. V-Dem Working Paper No. 21, 6th edition. University of Gothenburg: Varieties of Democracy Institute.

- Romanelli, Mauro (2016). ‘Understanding Governance of Parliamentary Administrations’, in Constantin Brătianu, Alexandra Zbuchea, Florina Pînzaru, Ramona-Diana Leon, and Elena-Mădălina Vătămănescu (eds.), Opportunities and Risks in the Contemporary Business Environment. Proceedings of the Fourth International Academic Conference Strategica, Bucharest, 1098–106.

- Romzek, Barbara S., and Jennifer A. Utter (1996). ‘Career Dynamics of Congressional Legislative Staff: Preliminary Profile and Research Questions’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 6:3, 415–42.

- Romzek, Barbara S., and Jennifer A. Utter (1997). ‘Congressional Legislative Staff: Political Professionals or Clerks?’, American Journal of Political Science, 41:4, 1251–79.

- Rozenberg, Olivier, and Eleni Tsaireli (2016). Vital Statistics on European Legislatures. Paris: Sciences Po, available at: https://statisticslegislat.wixsite.com/mysite/data (accessed 1 June 2021).

- Russell, Meg (2013). ‘Rethinking Bicameral Strength: A Three-Dimensional Approach’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 19:3, 370–91.

- Ryle, Michael T. (1981). ‘The Legislative Staff of the British House of Commons’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 6:4, 497–519.

- Sabatier, Paul, and David Whiteman (1985). ‘Legislative Decision Making and Substantive Policy Information: Models of Information Flow’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 10:3, 395–421.

- Salisbury, Robert H., and Kenneth A. Shepsle (1981). ‘US Congressman as Enterprise’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 6:4, 559–76.

- Sidlow, Edward I., and Beth Henschen (1985). ‘The Performance of House Committee Staff Functions: A Comparative Exploration’, Western Political Quarterly, 38:3, 485–94.

- Sieberer, Ulrich (2011). ‘The Institutional Power of Western European Parliaments: A Multidimensional Analysis’, West European Politics, 34:4, 731–54.

- Snagovsky, Feodor, and Matthew Kerby (2019). ‘Political Staff and the Gendered Division of Political Labour in Canada’, Parliamentary Affairs, 72:3, 616–37.

- Strøm, Kaare (1998). ‘Parliamentary Committees in European Democracies’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 4:1, 21–59.

- Taagepera, Rein (1972). ‘The Size of National Assemblies’, Social Science Research, 1:4, 385–401.

- UN Population Division (2019). 2019 Revision of World Population Prospects, available at: https://population.un.org/wpp/ (accessed 1 June 2021).

- UN Statistics Division (2021). Per Capita GDP at Current Prices – US Dollars, available at: https://population.un.org/wpp/ (accessed 1 June 2021).

- Weiss, Carol H. (1989). ‘Congressional Committees as Users of Analysis’, Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 8:3, 411–31.

- Winzen, Thomas (2011). ‘Technical or Political? An Exploration of the Work of Officials in the Committees of the European Parliament’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 17:1, 27–44.

- Winzen, Thomas (2014). ‘Bureaucracy and Democracy: Intra-Parliamentary Delegation in European Union Affairs’, Journal of European Integration, 36:7, 677–95.

- Yin, George K. (2012). ‘Legislative Gridlock and Nonpartisan Staff’, Notre Dame Law Review, 88, 2287.