?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Scholars of descriptive representation have paid growing attention to the issue of class. This article contributes to this line of research by examining the educational (mis)match of elected officials and the citizens they serve. Using data from an original paired elite-mass survey experiment, it investigates whether judgements of democratic quality are affected by education-based descriptive representation. The study reveals limited evidence in support of the idea that citizens and politicians value education-based descriptive representation in sociotropic terms. Instead, it provides strong evidence of affinity effects where democratic judgments are influenced by whether descriptive representation, or the lack thereof, favours citizens and politicians based on their own educational background. An important exception though are citizens without higher education, whose assessments of democratic quality are unaffected by education-based descriptive representation. The article ends with a discussion of the implications of these findings for existing and future research.

Descriptive representation is an established topic of study within political science, with most work focussing on the issue of elite-mass mismatch in terms of gender or race and ethnicity. In recent years, however, scholars have paid greater attention to how elected officials have significantly different social and economic backgrounds from citizens (Carnes Citation2013, Citation2018). This article contributes to this line of research by examining how education-based descriptive representation affects mass and elite evaluations of democratic performance.

Though university enrolments have expanded in recent decades, most voters have not completed higher education.Footnote1 By contrast, national politicians are overwhelmingly university educated, and the same is true in many countries for subnational officials (Reynaert Citation2012). The low level of descriptive representation of the less educated is therefore clear. What is less clear is whether the descriptive overrepresentation of the higher educated colours how citizens and elites think about democratic politics. On the one hand, there is evidence, though mixed, that citizens and elites may be unconcerned that politicians are disproportionately better educated perhaps because they view it as a sign of a well-functioning meritocracy (Besley et al.Citation2011; Carnes and Lupu Citation2016b; Congleton and Zhang Citation2013). On the other hand, various strands of empirical research suggest that citizens and elites judge the quality of their political systems based on the educational (mis)match between politicians and voters. Some scholars, for example, argue that education has become a source of and vehicle for political conflict, even amounting to a new structural cleavage, as advanced industrial economies have globalised and shifted to higher-skilled and knowledge-intensive sectors (Bovens and Wille Citation2017; Kriesi et al.Citation2008; Spruyt and Kuppens Citation2015; Stubager Citation2010, Citation2013). Other work examines how the descriptive underrepresentation of the less educated contributes to their being substantively underrepresented (Bovens and Wille Citation2017; Schakel and Hakhverdian Citation2018). Both these lines of research suggest that education-based descriptive representation will affect how people view the functioning of democracy.

Little research has been done on how education-based descriptive representation shapes public opinion and political behaviour. Some studies speak to this question indirectly using data from candidate selection experiments. Carnes and Lupu (Citation2016a) find, for example, that a candidate’s education has little impact on voter perceptions. Cowley (Citation2013), in a more direct observational test of education-based descriptive representation, finds that respondents set little store by national politicians sharing their level of education. We advance this area of research using data from a paired elite-mass survey experiment fielded in Norway. Specifically, we investigate whether citizen and elite assessments of democratic quality are sensitive to the (mis)match between the educational profile of politicians and the people they serve.

Using elite-mass paired data in this way to study the attitudinal effects of education-based descriptive representation has its merits given the fundamentally relational nature of representation. Given their different experiences, it would not be surprising if politicians and citizens think differently about descriptive representation and if, moreover, these differences contributed to calls for change being made by citizens but resisted by politicians. Comparing elite-mass views on the quality of democratic representation conditional on its (non-)descriptive characteristic can therefore offer insights into both the popular legitimacy of a democratic system and the odds of its elected bodies becoming more educationally representative.

Our study reveals limited evidence supporting the idea that citizens and elites conceive of education-based descriptive representation in sociotropic terms (i.e. valuing it as a general norm). We find instead strong evidence that education-based descriptive representation affects both elite and mass democratic assessments via an affinity mechanism. Namely, subjects are more positive about the functioning of democracy when representatives who share their level of education are in the majority, even if this means their education group is descriptively over-represented. An important exception is citizens without higher education. Our study shows that non-college-educated citizens’ assessments of democratic quality are unaffected by education-based descriptive representation. This is a significant finding given public debates in recent years about the growing anti-elitism among the lower educated. Our findings further indicate that higher educated elites and citizens are congruent but lower-educated elites and citizens are not.

In the next section, we outline four alternative accounts of how education-based descriptive representation might affect assessments of democratic quality. We then discuss the case of Norway where our elite-mass survey experiment was fielded. This is followed by a description of the data and methods used to test our hypotheses and a presentation of the findings that emerge from our analyses. The article ends with a discussion of the contributions and implications of our findings for existing and future research.

Theory and hypotheses

Existing research suggests competing hypotheses about the relationship between education-based descriptive representation and perceptions of democratic performance. We begin by reviewing studies and arguments that support the idea of a relationship between the two. This includes two possibilities. The first is that citizens and elites value education-based descriptive representation as a general norm (the sociotropic hypothesis). The second possibility is that education-based descriptive representation affects perceptions of democratic performance via an affinity mechanism (the affinity hypothesis). We end this section of the article by discussing research that gives us pause to think that perceptions of democratic performance and education-based descriptive representation are related. This also includes two possibilities. On the one hand, there is reason to believe that our study subjects might care about politicians’ level of formal education not because they want them to be descriptively representative but rather because they view educational achievement as an indicator of politicians’ ability to do their jobs well (the being-qualified hypothesis). On the other hand, perceptions of democratic performance may be entirely unrelated to the educational make-up of politicians as a group (the null hypothesis).

Why would citizens or elites evaluate politics based on the educational match between elites and the general public? Existing work on descriptive representation suggests that certain conditions likely must hold for individuals to want a characteristic to be represented descriptively (see, e.g. Mansbridge Citation1999). This includes a sense of shared fate among individuals with the characteristic in question, which solidifies over time based on everyday experiences and processes of socialisation and, not unrelated, as a result of the persuasive and mobilising discourse and actions of social and political leaders. A key element connecting a sense of shared fate with a desire for descriptive representation is the understanding among individuals identifying with the group that they have broad beliefs and/or preferences in common, be they more or less narrow or more or less crystallised, to which existing political actors and institutions – dominated by outgroup members – are frustratingly unresponsive. A positive orientation towards descriptive representation is therefore driven by a desire to have the needs and wants of different groups (including the group or groups to which one belongs) heard and heeded in and by the political process.

Do any of the above conditions hold for education? Do people with differing levels of formal education have distinct beliefs and preferences from each other? Are the less educated underserved by politicians, and does this relate to their numerical under-representation? Do people experience a sense of shared fate bound by education?

A growing body of work has emerged in the past decade that provides cross-national evidence of differences in beliefs and policy preferences between higher- and lower-educated citizens. This includes attitudes towards immigration and immigrants (Cavaille and Marshall Citation2019), inequality and the welfare state (Häusermann and Kriesi Citation2015), globalisation (van der Waal and de Koster Citation2015) and European integration (Hakhverdian et al.Citation2013), as well as process preferences related to direct democracy (Coffé and Michels Citation2014). Scholars have also examined how political elites reflect the divergent attitudes and policy preferences of the lower and higher educated. Some have studied this question in terms of attitudinal (in)congruence between politicians and citizens grouped by education (Hakhverdian Citation2015), others from the point of view of policy responsiveness (Schakel and van der Pas Citation2021).

While political scientists have identified education as a key marker of inter-group difference and a driver of structural change in the political economies of Europe and beyond (Kriesi et al.Citation2008), citizens (and elites) may not understand or experience reality in the same way. Research that confirms divergences in voting behaviour between the more and less educated does, however, speak to the ways in which education has increasingly become (and elites have helped it to become) an anchor for how citizens think about and engage with politics (Bovens and Wille Citation2017; Kriesi et al.Citation2012; Stubager Citation2013). Despite these attitudinal and behavioural differences between higher- and lower-educated citizens, education may still fall short of serving as a source of shared fate or group consciousness for voters (or even elites). If this is the case, education-based descriptive representation is unlikely to affect how citizens (or elites) view the functioning of democracy. There is little direct empirical social scientific research on this question of an educationally-bound shared fate, and what exists relates to a small number of countries and focuses on the attitudes of citizens rather than elites (Kuppens et al.Citation2018; Spruyt Citation2014; Spruyt and Kuppens Citation2015; Stubager Citation2013). The results of this work do point, however, to the existence of education-based collective identity as well as antipathies, even mutual stigmatisation, between the lower and higher educated (Noordzij et al.Citation2019). Taken together, these various strands of research suggest that (at least in certain contexts) educational group consciousness will colour how citizens (and perhaps elites) evaluate the functioning of democracy.

Based on the above research, we hypothesise that there are two ways in which education-based descriptive representation might relate to perceptions of democratic performance. The first depends on subjects holding a sociotropic view of education-based descriptive representation; that is to say, they understand citizen-elite matching in societal terms as the degree to which the educational background of politicians, as a group, corresponds to that of the general population (or voters). The basic argument here is that, at the same time as subjects recognise their shared fate with others with a similar educational background, they also set democratic store by the educational representativity of political bodies as a whole. This does not mean that individuals will forgo evaluating or supporting candidates on the basis of their education or, by extension, parties based on their past or promised responsiveness to citizens with different educational backgrounds. What it does mean is that their judgments of the overall performance of democracy will be affected by how educationally representative elected bodies are (or understood to be).

If our survey subjects value education-based descriptive representation in sociotropic terms, we expect them to assess the functioning of democracy most positively when presented with scenarios where there is an educational match between citizens and representatives and least positively when citizens and representatives do not match educationally (Hypothesis 1A). Moreover, we expect that their democratic assessments will be unaffected by the match between their own level of education and that of the representatives in the scenarios with which they are randomly presented (Hypothesis 1B).

An alternative way in which education-based descriptive representation could affect how citizens and elites evaluate the functioning of democracy is through the operation of a so-called affinity effect. An affinity effect exists when individuals are differentially sensitive to the descriptive representation of a particular characteristic or attribute depending on whether they themselves possess or identify with that characteristic or attribute. Researchers have observed many kinds of affinity effects regarding race and ethnicity (Gay Citation2002; Wallace Citation2014) and gender (Allen and Cutts Citation2016; Campbell et al.Citation2010). Much of this research acknowledges the complex nature of affinity effects, including the ways in which gender and race and ethnicity intersect with each other and other characteristics, including – crucially – partisanship (Campbell et al.Citation2010; Teele et al.Citation2018).

Based on existing research, we know little about the operation of education-based affinity effects. Several candidate selection studies, using experimental data, have been published on how candidates’ educational level affects voter choice (e.g. Campbell and Cowley Citation2014, Carnes and Lupu Citation2016a), but none of these has to date examined the conditioning effects of voters’ own level of education. As for elites, no research to date has been done on whether representatives view each other through the lens of educational achievement or, for that matter, on the basis of their own level of education. That said, the research on affinity effects related to gender and race/ethnicity coupled with existing work that points to the emergence of education as a political cleavage in advanced industrial democracies strongly suggests that we should expect to observe evidence of affinity effects in our experimental study. If this is true, our survey subjects will be more positive about the functioning of democracy when representatives who share their level of education are in the majority, even if this means their education group is descriptively over-represented. Specifically, we should expect that, compared to the higher educated, lower educated respondents will be more critical of the functioning of democracy when reacting to scenarios where the non-college educated are under-represented and, on the other hand, provide more positive assessments of democratic quality when the non-college educated are over-represented (Hypothesis 2A). We expect the opposite to be true for the higher educated (Hypothesis 2B).

An alternative to the above sociotropic and affinity hypotheses is that education-based descriptive representation is unrelated to assessments of democratic quality. This line of reasoning also finds support in different strands of existing research. This work suggests two additional possibilities: first, that our study subjects might look favourably on the descriptive over-representation of the higher educated regardless of their own level of education; second, that their democratic assessments might be entirely unaffected by representatives’ level of education.

In everyday life, we rely on the work and advances of doctors, scientists and engineers who gained their knowledge as a direct result of higher education. Moreover, the positions of authority and influence across multiple domains of social, economic and political life, enjoyed by the higher educated grant them an advantaged position to legitimise higher education discursively as good for society (Spruyt Citation2014). It therefore seems plausible that many people, including the lower educated, might be positively predisposed to higher education and the higher educated. This seems especially likely where access to higher education is (or is perceived to be) open and freely available and enrolments in higher education are expanding and where social mobility is high (or, again, perceived to be high). In such contexts, the privileged social and economic positions and contributions of the higher educated are likely viewed as the result of a well-functioning meritocracy. Politicians may also be positively inclined towards higher education. Work based on data from Italy (Galasso and Nannicini Citation2011), indicating that parties select better educated candidates to run in more competitive electoral districts, is suggestive of the value that political elites attribute to education. Though empirical research in this area is limited, the above arguments suggest that our study subjects – lower and higher educated alike – will provide more positive democratic assessments when their representatives are majority higher educated, even if this means that an elected body is descriptively unrepresentative of the general population (Hypothesis 3).

The reported findings of existing candidate selection studies (where affinity effects are untested for) strongly support a fourth and final expectation – namely, that democratic assessments are entirely unrelated to representatives’ educational make-up (Hypothesis 4). What this research underscores is how little voters care about candidates’ level of education (Carnes and Lupu Citation2016a; Mechtel Citation2014; though see Schneider and Tepe Citation2011). Other qualities matter more, not least whether voters believe an aspiring politician will be able to defend and promote their values and interests (Cowley Citation2013; Franchino and Zucchini Citation2015). If voters generally do not set much store by candidates’ level of education, why should politicians? Having the skills and knowledge to realise partisan victories at the ballot box and in the legislative process will surely weigh more heavily on politicians’ minds. Analyses of data from surveys of national elected officials in Belgium, France, and Portugal support this line of reasoning (Lisi and Freire Citation2012).

Finally, before turning to the details of our research study, it is worth noting that in presenting our hypotheses, we avoided weighing in on whether any of our expectations might apply more to citizens than to elites in our study. Due to the importance of party discipline and party cohesion in many high-income democracies, coupled with the fact that citizens could be the target of strategic identity-mobilising efforts of elites without elites themselves necessarily internalising an educationally-bound identity, there is good reason to believe that we will find a null effect among elected officials in our sample. Still, given the dearth of elite-focussed attitudinal research in this area (and on descriptive representation more generally), this is pure speculation.

The case of Norway

We test our hypotheses using response data from a survey experiment fielded in Norway. Like elsewhere, the higher educated are overrepresented among Norway’s national politicians compared to the country’s general population (Fiva and Smith Citation2017). The share of politicians with a university degree drops when we include officials elected to municipal and county councils. However, including subnational officials when analysing the scale and nature of descriptive underrepresentation is particularly important in the case of Norway given local politicians’ significant powers in financing, planning, and delivering welfare services, including in education and social care (see, e.g. Baldersheim and Rose Citation2011).Footnote2

While Norway is therefore largely similar to other high-income democracies in terms of the educational mismatch between elites and citizens, its political economy is not. Like other Nordic democracies, Norway is characterised by a culture of egalitarianism and high levels of social mobility. Both of these features are rooted in national welfare policies and programs implemented by social democratic governments in the course of the post-war period, building off earlier welfare reforms advanced by right-leaning governments (Bjørnson Citation2001). At the heart of Norway’s form of welfare capitalism lies the country’s system of education. There are no difficult admission tests for university in Norway, nor are there college tuition fees for the country’s network of public universities that enrol close to 90 percent of college students (Koutsogeorgopoulou Citation2016). Moreover, most students are eligible for public financial support (via grants and loans) through Lånekassen, Norway’s Educational Loan Fund. Researchers have also found that the relationship between educational achievement and social status is weaker in Norway than other high-income democracies, and that Norwegian parents are less likely to push their children to pursue higher education (Skarpenes and Sakslind Citation2010).

Taking these facts and factors together, educational achievement in Norway – including most notably graduating from university – is arguably more reflective of personal choice than familial wealth or broader socio-economic inequalities, as is the case in many other market economies. Norwegians are therefore unlikely to view the political overrepresentation of the higher educated as evidence of a rigged system but rather as indicating that people who get elected to public office also (happen to) choose to go to university. If true, Norwegians will likely be unmoved by the educational (mis)match between politicians and voters; it simply would not register as a relevant social fact when assessing the functioning of their political system. As such, we consider Norway as a least likely case for observing a relationship between education-based descriptive representation and mass and elite evaluations of democratic performance.

Data and methods

We use a paired elite-mass survey experiment to test for the effects of education-based descriptive representation on evaluations of democratic performance. This experimental approach allows us to vary both the nature of the (mis)match in educational composition of politicians and citizens while controlling for the effects of a range of other factors (Mutz Citation2011; Sniderman Citation2011). The elite component of the experiment was part of the first round of the Panel of Elected Representatives (PER) fielded in March–April 2018. The citizen component was included in the 12th round of the Norwegian Citizen Panel (Norwegian Citizen Panel Wave 12, Citation2018) fielded in June 2018. The PER is a web-panel that invites participation from all Norwegian officials elected at the municipal, county, and national levels, as well as those elected to the Sami parliament.Footnote3 At the time of the experiment there were 11,362 elected officials in Norway. In all, 4321 partially or fully completed the first round of the panel survey, producing a response rate of 38.2 percent.Footnote4 The NCP is a web-panel based on a probability sample of the general population of Norway, aged 18 and over, drawn from the Norwegian National Registry.Footnote5 A total of 1384 individuals belonging to the citizen panel were presented with the experiment.Footnote6

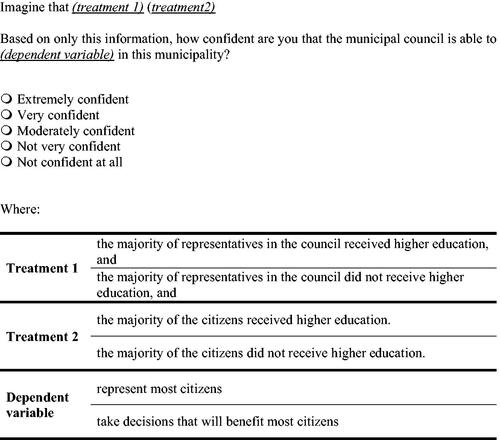

In our experimental vignettes, respondents were asked to react to a scenario that describes the educational composition of representatives and citizens in a municipality. The scenarios include information about the educational level of most citizens and most local councillors in a municipality (specifically, whether they completed (or did not complete) higher education). Our design resulted in four scenarios: two where politicians are descriptively representative of citizens; and two where they are not. Respondents were presented with one of four scenarios, i.e. using a between-subjects design, and the treatments varied randomly with respondents having an equal chance of being presented with any one of the four scenarios. The first describes a situation where the majority of both representatives and citizens have higher education (which we refer to as the HighHigh scenario). A second is where the majority of representatives received higher education, while most citizens did not (the HighLow scenario). A third is where the majority of representatives did not receive higher education but most citizens did (the LowHigh scenario). Finally, a fourth scenario is where the majority of both representatives and citizens did not receive higher education (the LowLow scenario). These four treatments are our main independent variables.

Respondents were then asked to evaluate the representational performance of the municipality. Given this set-up, there may be a risk of social desirability in respondents’ answers (Clayton et al.Citation2019). However, it is not clear which scenario would be the most socially desirable for respondents—would they feel pressure to signal that having higher-educated councillors or a descriptively representative scenario is more appealing? The LowHigh scenario may be viewed as the least socially desirable. If true, then a social desirability bias would result in the LowHigh scenario being the least appealing to our respondents. We do not find this to be the case, and our results rather show meaningful variation among the different scenarios. These results suggest that social desirability bias is not a major concern for our design.

Having been randomly presented with one of the above scenarios, citizens and politicians were asked to indicate how confident they are that the local council would carry out one of two democratic functions: representing most citizens; and making decisions that benefit most citizens. Each respondent was assigned to assess the quality of the local democratic process from one of these two vantage points. The treatments were again randomised so that reactions to the two democratic functions could be examined separately. All combinations of the experiment were equally likely to be presented to any one respondent.Footnote7 The full experimental design is presented in .

The outcome variables of this study capture – in deliberately broad terms – two key aspects of democratic performance.Footnote8 The first (‘representing most citizens’) corresponds to the notion of democracy of and by the people where elected officials are expected to ‘stand for’ and ‘make present again’ (to borrow the words of Hannah Pitkin (Pitkin Citation1967)) the voices and preferences of citizens in public policy-making processes. The second (‘making decisions that benefit most citizens’) captures the notion of democracy for the people (or ‘acting for’, in Pitkin’s words) where elected officials are expected to legislate and pursue public policies that are responsive to the needs and wants of citizens. In both instances, we measure these from an implied majoritarian perspective by asking survey respondents to evaluate democratic performance through the lens of how the system is working for ‘most’ citizens. This mirrors the design of the survey treatments where respondents are presented with scenarios that describe the educational background of most representatives and most citizens.Footnote9

We focus here on the results related to democracy for the people (i.e. ‘acting for’ or democratic responsiveness) and include the results for democracy of and by the people (i.e. ‘standing for’ or democratic inclusion) in in the Online Appendix. The results for these two aspects of democratic quality are very similar.

In addition to the survey experiment, citizens and politicians provided information on their highest educational qualification, ranging from no formal education to holding a doctorate. These response data were used to generate a dummy measure of education (where 1 means having completed higher education).

We analyse the resulting data by estimating a series of OLS models and plotting the predicted values associated with the different scenarios along with 84% confidence intervals.Footnote10 To test whether subjects’ treatment responses are conditional on level of education, we interact our measure of education with the dummy variable for each treatment. The following equations are therefore estimated:

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

Results

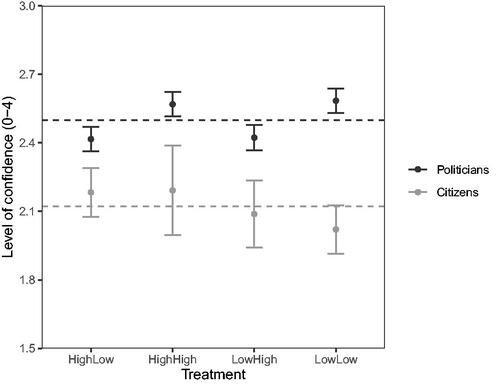

We begin by examining the data for evidence that citizens’ and politicians’ evaluations of democratic performance are sensitive to the descriptive (mis)representation of education (H1A). The results of the first set of models presented in provide only partial support for this idea. If descriptive representation based on education shapes evaluations for the better, we would expect to observe higher predicted values on the HighHigh and LowLow coefficients. shows that this is the case for politicians, but not for citizens. In fact, citizens as whole think that a LowLow scenario would be less democratically responsive than the others, though this difference is not statistically significant.

Figure 2. Evaluations of democratic responsiveness and education-based descriptive representation.

Notes: The figure gives the predicted values, including 84% confidence intervals. Table A5 in the Online Appendix provides detailed estimates. The dashed lines indicate the mean value of the outcome for politicians and citizens respectively.

Our data indicate that politicians are moved by descriptive representation (supporting H1A). The educationally descriptive scenarios produce more positive assessments of democratic representation than on average (black dashed line), and significantly higher levels than non-descriptive scenarios.Footnote11 This suggests that politicians generally believe democracy is more responsive when representatives and voters share the same educational background. By contrast, and in line with H4, citizens set little store by education-based descriptive representative. Levels of confidence in democratic responsiveness are always close to the mean (grey dashed line) and are statistically the same across all four experimental scenarios. Neither the results for politicians nor those for citizens provide support for Hypothesis 3, which stated that people would value politicians with higher education, regardless of their personal educational background.

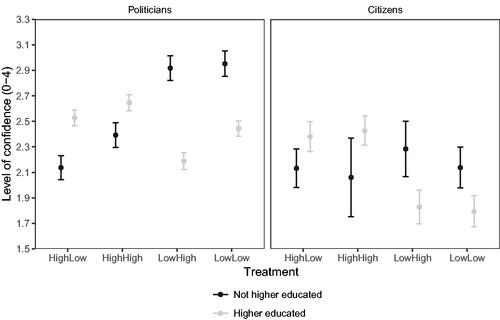

We now turn to the models that include interaction terms testing for the conditioning effect of individual-level education (as per H1B, H2A and H2B). These models allow us to examine whether taking into account citizens’ and politicians’ personal educational background alters the average-effect results reported above. To provide a substantial understanding of these interactive tests, we calculate estimates of how democratically responsive citizens and politicians, with and without higher education, judge the four experimental scenarios. The predicted values are plotted in . The results regarding confidence in democratic inclusion can be found in in the Online Appendix.

Figure 3. Evaluations of democratic responsiveness, conditional on education.

Notes: The figure gives the predicted values, including 84% confidence intervals. Table A6 in the Online Appendix provides detailed estimates.

If citizens and politicians judge democratic performance on the basis of a sociotropic norm of descriptive representation, we would expect the descriptive representation scenarios to produce more positive responses than the other scenarios—regardless of the respondents’ own level of education (H1A and H1B). , however, offers no support for this. While higher-educated politicians seem to value the descriptive representation scenarios, they value the HighLow scenario over the LowLow scenario.Footnote12 What we observe is evidence of affinity effects, supporting H2A and H2B. shows that politicians without higher education assess the LowHigh and LowLow scenarios significantly more positively than the HighHigh scenario, with the HighLow scenario prompting the least positive responses. This pattern is somewhat mirrored among higher-educated politicians. They offer more positive assessments in response to the HighHigh and HighLow scenarios, although the HighLow scenario is not significantly different from the LowLow scenario.Footnote13

Overall, this suggests that it is not so much the descriptive mismatch that is driving the assessments of politicians but rather whether or not they and their kind are in the majority, which indicates that their democratic assessments are more likely moved by an affinity effect. That said, higher-educated politicians do view democracy as working better in terms of responsiveness under the LowLow condition than under the LowHigh condition, and lower-educated politicians value the HighHigh condition more than the HighLow condition, which suggests affinity effects cannot fully explain the variations that we observe.

As for citizens, indicates that the democratic assessments of higher-educated subjects also seem to be driven by affinity effects. They give more positive assessments in response to the HighLow and HighHigh scenarios than the LowLow and LowHigh ones (H2b). Among higher-educated citizens, judgements of democratic responsiveness are equally favourable regardless of whether they are randomly assigned to the HighHigh or HighLow treatment conditions. Similarly, the less favourable democratic assessments of higher-educated citizens do not show any difference between the LowLow and the LowHigh treatment conditions. Interestingly, this pattern is not mirrored in the results for lower-educated citizens. We find rather that the differences in how democratically responsive lower-educated citizens expect democracy to be are statistically insignificant from each other across all four treatment groups. This provides strong evidence that citizens without higher education are unmoved by variations in education-based descriptive representative (supporting H4).Footnote14

When comparing the results of politicians to those of citizens, one thing that stands out is that politicians provide higher assessments of democratic representation. At the same time, we observe larger variation in politicians’ democratic assessments across the four scenarios, which suggests that education-based (non-)descriptive representation affects politicians’ views of what good representation is more than it does citizens’. Although average levels of confidence vary between politicians and citizens, the impact of the four scenarios on politicians and citizens, grouped by education, is similar: higher-educated citizens and politicians value representation by the higher educated and are more sceptical when lower-educated representatives are in the majority; lower-educated citizens and politicians appear somewhat sceptical towards representation by the higher educated. However, lower-educated citizens do not value representation by the lower educated any more than they do representation by the higher educated. This finding may indicate a trade-off experienced by citizens without higher education; namely, they may see value in being represented by politicians without a university degree but also value representation by those they see as more capable, i.e. those with higher education. That said, it is possible that subjects without higher education simply do not see any of the scenarios as better or worse based on their experience. The politicians in our sample, on the other hand, can draw on their own experiences as representatives, which could reinforce their belief that they are good representatives, maybe better than the other group. This difference in experience may thus partly explain the divergent findings for citizens and politicians.

Robustness tests

We conduct various robustness checks to account for potential alternative explanations, confounding effects, and coding choices. First, we examined the government level at which politicians are elected and their years of experience as well as citizens’ and politicians’ political ideology as alternative explanations that may be related to educational background. The level of government at which a politician serves could indicate some form of professional development in politics potentially associated with their educational background. In our data, we find a weak correlation between these indicators, with municipal councillors somewhat less likely to be higher educed (68%) than non-municipal politicians (82%). Moreover, we find that politicians’ democratic assessments do not vary substantially across the four scenarios based on the level of government to which they are elected. Politicians’ years of experience is weakly correlated with their level of education: where those with more experience (≥12 years) are somewhat less likely to have higher education (63–65%) than those with less experience (<12 years; 70–73%). Using years of experience as the interaction variableFootnote15 instead of education, we observe an echo of our main results: politicians with less experience tend to value representation by higher-educated representatives somewhat more than by lower-educated representatives, and politicians with more experience tend to value the LowHigh and LowLow more. Lastly, political ideology is largely unrelated to citizens’ and politicians’ education level, though politicians from right-leaning parties tend to value the HighHigh and HighLow scenarios more than the other scenarios, but also more than their left-wing colleagues. This is somewhat similar for citizens, though less clear-cut.Footnote16 Figures A3–A5 in the Online Appendix present the results of these tests.

Second, to test whether the effect of education is unaffected by other relevant variables, we introduce the alternative explanations as control variables. In experimental analyses, the use of control variables is normally not needed due to the randomisation process. However, subjects’ education was not part of the experiment itself and its effect may therefore depend on other indicators especially if they are related to both the dependent and main independent variable. However, introducing these controls (i.e. government level, experience and ideology) to our models does not alter our results. Table A7 in the Online Appendix presents the results of these tests.

Third, we measured education in four different ways to test whether our findings were dependent on our coding choice. Table A4 and Figures A6–A8 in the Online Appendix provide further information on these alternative codings and the results they produced, which substantively replicate the results of our main models.

Discussion and conclusion

Using data from an original elite-mass paired survey experiment, our study examines whether education-based descriptive representation matters for how citizens and politicians view democratic performance. At first blush, the data provide partial support for our sociotropic hypothesis insofar as politicians (but not citizens) appear to value education-based descriptive representation as a general norm. Further analyses make clear, however, that our affinity hypothesis finds stronger support in the data. That is to say, subjects are more positive about the functioning of democracy when representatives who share their level of education are in the majority, even if this means their education group is descriptively over-represented. The evidence in support of this finding is clear and compelling for politicians without higher education, and our data provide strong evidence to suggest that this is also the case among higher-educated politicians and higher-educated citizens. As for citizens without higher education, our analyses indicate that their democratic evaluations are unaffected by whether elected officials match or mismatch the people they serve in terms of education (thereby supporting the null hypothesis). In short, with the notable exception of citizens without higher education, when it comes to evaluating democratic quality, where you stand depends on where you sit.

Our study contributes to the large empirical literature on descriptive representation in several ways. It adds to our understanding of the positive relationship between political attitudes and descriptive representation, extending prior research – focussed on political trust and efficacy – to evaluations of democratic performance. Building off our findings and recent work on gender-based descriptive representation (Clayton et al.Citation2019), an important topic for future research will be to examine whether and how education-based descriptive representation affects the perceived legitimacy of policy decisions (beyond assessments of democratic quality). Our study also extends and adds to existing mass attitudinal work by examining the attitudes of political elites. In so doing, it provides a sobering insight into the unlikelihood of existing elected bodies (dominated by higher-educated politicians) becoming more educationally representative.

For important reasons, existing scholarship on descriptive representation has mainly centred on gender and race. In recent years, however, an empirical literature has emerged on class-based descriptive representation (Carnes Citation2013, Citation2018). The number of published pieces focussed on class-based descriptive representation remains relatively small and mainly focuses on the occupational background of politicians and candidates; moreover, of the studies that use data from high-income democracies, the sample of countries remains limited. With our focus on education, this study contributes directly to this line of research. Class is a multi-dimensional concept often captured by political scientists using data on occupation, education and income. While these three indicators may be highly correlated at the individual level, none by itself can fully capture a person’s class status. Reading the findings of our study alongside those of existing research underscores this point. Past candidate selection studies (as summarised earlier in the article) clearly show, for example, that voters care more about aspiring politicians’ occupation than their level of education. Yet, the past decade has seen a growing scholarly interest in education as an emergent political cleavage (see, e.g. Bovens and Wille Citation2017; Kriesi et al.Citation2012; Stubager Citation2010), which suggests we should observe citizens and politicians caring about education-based descriptive representation. Our findings are largely consistent with this expectation, with the notable exception of citizens without higher education. Still, more research is needed to confirm our findings in other contexts and, most importantly, to better understand the ways in which occupation and education (as well as income) intersect in how citizens and politicians think about class and the political representation of different class groups.

Our study also contributes to research on descriptive representation by underscoring the analytic importance of distinguishing between elite-mass matching as a sociotropic feature of a system that individuals might value normatively (independent of whether that means they are themselves personally underrepresented in some way) and descriptive representation understood in egocentric or affinity terms as the match between one or more politicians and the individual in question. Few studies (see, e.g. Arnesen and Peters Citation2018; Cowley Citation2013) directly test whether citizens sociotropically value a norm of descriptive representation. In addressing this gap in the literature, our study points to a need for more empirical work in this area.

A second literature to which our findings speak is research on education-based divisions in public opinion. While a growing body of research demonstrates systematic variations in the policy preferences of higher- and lower-educated citizens, less work has been done on how education shapes processual attitudes (Coffé and Michels Citation2014). Our study provides evidence of an attitudinal divide between higher- and lower-educated citizens on the issue of descriptive representation. Higher-educated citizens value descriptive representation of their own kind but lower-educated citizens do not. Our data also suggest that lower-educated politicians have a more intense preference for education-based descriptive representation than higher-educated politicians.

This structuring of public opinion resonates with existing studies on education-based group consciousness (Spruyt Citation2014; Spruyt and Kuppens Citation2015) as well as research on the growing strength of a political cleavage centred on education (Bovens and Wille Citation2017; Stubager Citation2010). Our findings have some implications for this line of research. First, our study points to the difficulties that elites without higher education may encounter when trying to use educational under-representation as a way of mobilising lower-educated citizens. A question for future research is whether the insensitivity of the lower educated to their political under-representation is limited to countries like Norway with high social mobility and free access to higher education. In such contexts, the lower educated may be untroubled by a higher-educated skew in elected bodies because they do not view the system as rigged against them. Still, the fact that we find that higher-educated citizens and politicians assess the functioning of democracy more negatively when lower-educated representatives are in the majority (even if this means the elected body in question is descriptively representative of the local population) suggests that attempts to improve educational representativity will be resisted. That we find this using data from Norway, which we consider to be a least likely case, is therefore telling and interestingly consistent with work by Kuppens et al. (Citation2018) showing intergroup bias among the higher educated but not among the lower educated. The implication is that in more socio-economically unequal societies we might expect to find the higher educated to be even more sensitive and resistant to efforts to improve the descriptive representation of the lower educated. Our hope is that future research using experimental and observational data from other countries will be able to put this expectation to the test.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (485.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the WEP reviewers and editors for their valuable and thoughtful feedback. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at a ‘Politics of Inequality’ workshop held at Harvard Kennedy School, the ‘Unequal Democracies Seminar’ at the University of Geneva, the Ash Center Democracy Seminar at Harvard Kennedy School, and the ‘Citizens, Opinion, and Representation Research Group’ at the Department of Comparative Politics, University of Bergen. We thank the participants of these workshops and seminars as well as Sveinung Arnesen, Dan Butler, and Jane Mansbridge for their helpful comments on earlier drafts. We would also like to acknowledge financial support from the Trond Mohn Foundation and the University of Bergen (Grant # 811309).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

Trond Mohn stiftelse (formerly Bergens Forskningsstiftelse), Grant # 811309.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Quinton Mayne

Quinton Mayne is Ford Foundation Associate Professor of Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School, Harvard University. His research interests include comparative political behaviour, democratic representation, subnational and urban politics, and social policy. [[email protected]]

Yvette Peters

Yvette Peters is Professor in Comparative Politics at the University of Bergen, Norway. Her research has been published in Comparative Political Studies, Governance, and the European Journal of Political Research, amongst others. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 According to 2017 data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, across its 35 member countries, 37 percent of 25–64 year-olds have completed some form of tertiary education.

2 We take advantage of this fact in the design of our survey experiment by asking citizen and elite respondents to evaluate democratic performance at the local level.

3 For more detailed information (in Norwegian) on the PER, see https://www.uib.no/representant.

4 The sample is largely representative of the population of elected representatives. See Table A1 in the Online Appendix. While there is a slight gender bias with more women responding at the national level (+5%), and more men at the municipal (+2.8%) and county (+1.5%) levels, the sample corresponds well to the population in terms of age, education, geographic location (county), and party affiliation.

5 For detailed information (in Norwegian) on the NCP, see https://www.uib.no/medborger.

6 The sample (see Table A1 in the Online Appendix) is skewed in terms of age and education. Models using the citizen data have weights applied.

7 The randomization procedure is executed live as the respondent completes the survey. All respondents are randomly assigned to receive one of two alternatives, for each of the three treatments, and each treatment-randomization is independent. Normally this results in groups that are equal in size when the sample is large enough. This was also the case here. For each of the treatments, about 50 percent of respondents were selected in each of the two options (with a ±1–2% deviation). However, since we cannot be certain that the randomization process was performed exactly as intended, we also carried out a balance check for the treatment groups on the basis of education, gender, and age and found no systematic differences in the composition of the groups. We further checked whether any of the scenarios affected respondents disproportionately by examining the number of missing values in each group, and similarly found no systematic differences (see Tables A2a–c in the Online Appendix).

8 We randomize the assignment of the dependent variables. We did this to avoid the risk of response bias that would prevent us from examining how education-based descriptive representation affects the assessments of the two types of representation in different ways.

9 See Table A3 in the Online Appendix for descriptive statistics related to the dependent variables across the four treatment groups.

10 95% confidence intervals can be used to assess whether a point estimate is significant at the 5% level, two-sided, based on its overlap with zero. An overlap in 84% confidence intervals of two point estimates indicates that they are not statistically different from each another at the 5% level, two-sided (Julious 2004).

11 The same is true for confidence in democratic inclusion, see Figure A1 in the Online Appendix

12 Looking at the alternative dependent variable of confidence in democratic inclusion (see Figure A2 in the Online Appendix), we only observe suggestive support for the value of the norm of representation among higher-educated politicians. They value the HighHigh and LowLow scenarios most, though again, the HighLow scenario scores nearly as well.

13 This pattern is similar for the assessments of democratic inclusion reported in the Online Appendix.

14 We observe similar patterns for citizens’ assessments of democratic inclusion (as shown in the Online Appendix).

15 Using a three-point index, where 0 = 0–3 years, 1 = 4–11 years, and 2 = 12+ years of experience.

16 Ideology is measured using the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) data on overall left-right positions of political parties, so that people belonging/voting for a particular party receive the CHES left-right score. See https://www.chesdata.eu/.

References

- Allen, Peter, and DavidCutts (2016). ‘Exploring Sex Differences in Attitudes towards the Descriptive and Substantive Representation of Women’, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 18:4, 912–29.

- Arnesen, Sveinung, and YvettePeters (2018). ‘The Legitimacy of Representation: How Descriptive, Formal, and Responsiveness Representation Affect the Acceptability of Political Decisions’, Comparative Political Studies, 51:7, 868–99.

- Baldersheim, Harald, and Lawrence E.Rose (2011). ‘Norway: The Decline of Subnational Democracy?’, in JohnLoughlin, FrankHendriks, and AndersLidström (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Local and Regional Democracy in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 282–304.

- Besley, Timothy, Jose G.Montalvo, and MartaReynal‐Querol (2011). ‘Do Educated Leaders Matter?’, The Economic Journal, 121:554, F205–227.

- Bjørnson, Øyvind (2001). ‘The Social Democrats and the Norwegian Welfare State: Some Perspectives’, Scandinavian Journal of History, 26:3, 197–223.

- Bovens, Mark, and AnchritWille (2017). Diploma Democracy: The Rise of Political Meritocracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Campbell, Rosie, SarahChilds, and JoniLovenduski (2010). ‘Do Women Need Women Representatives?’, British Journal of Political Science, 40:1, 171–94.

- Campbell, Rosie, and PhilipCowley (2014). ‘What Voters Want: Reactions to Candidate Characteristics in a Survey Experiment’, Political Studies, 62:4, 745–65.

- Carnes, Nicholas (2013). White-Collar Government: The Hidden Role of Class in Economic Policy Making. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Carnes, Nicholas (2018). The Cash Ceiling: Why Only the Rich Run for Office–and What We Can Do about It. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Carnes, Nicholas, and NoamLupu (2016a). ‘Do Voters Dislike Working-Class Candidates? Voter Biases and the Descriptive Underrepresentation of the Working Class’, American Political Science Review, 110:4, 832–44.

- Carnes, Nicholas, and NoamLupu (2016b). ‘What Good Is a College Degree? Education and Leader Quality Reconsidered’, The Journal of Politics, 78:1, 35–49.

- Cavaille, Charlotte, and JohnMarshall (2019). ‘Education and anti-Immigration Attitudes: Evidence from Compulsory Schooling Reforms across Western Europe’, American Political Science Review, 113:1, 254–63.

- Clayton, Amanda, Diana Z.O’Brien, and Jennifer M.Piscopo (2019). ‘All Male Panels? Representation and Democratic Legitimacy’, American Journal of Political Science, 63:1, 113–29.

- Coffé, Hilde, and AnkMichels (2014). ‘Education and Support for Representative, Direct and Stealth Democracy’, Electoral Studies, 35, 1–11.

- Congleton, Roger, and YongjingZhang (2013). ‘Is It All about Competence? The Human Capital of U.S. Presidents and Economic Performance’, Constitutional Political Economy, 24:2, 108–24.

- Cowley, Philip (2013). ‘Why Not Ask the Audience? Understanding the Public’s Representational Priorities’, British Politics, 8:2, 138–63.

- Fiva, Jon H., and Daniel M.Smith (2017). ‘Norwegian Parliamentary Elections, 1906–2013: Representation and Turnout across Four Electoral Systems’, West European Politics, 40:6, 1373–91.

- Franchino, Fabio, and FrancescoZucchini (2015). ‘Voting in a Multi-Dimensional Space: A Conjoint Analysis Employing Valence and Ideology Attributes of Candidates’, Political Science Research and Methods, 3:2, 221–41.

- Galasso, Vincenzo, and TommasoNannicini (2011). ‘Competing on Good Politicians’, American Political Science Review, 105:1, 79–99.

- Gay, Claudine (2002). ‘Spirals of Trust? The Effect of Descriptive Representation on the Relationship between Citizens and Their Government’, American Journal of Political Science, 46:4, 717–32.

- Hakhverdian, Armen (2015). ‘Does It Matter That Most Representatives Are Higher Educated?’, Swiss Political Science Review, 21:2, 237–45.

- Hakhverdian, Armen, Erikavan Elsas, Woutervan der Brug, and TheresaKuhn (2013). ‘Euroscepticism and Education: A Longitudinal Study of 12 EU Member States, 1973–2010’, European Union Politics, 14:4, 522–41.

- Häusermann, Silja, and HanspeterKriesi (2015). ‘What Do Voters Want? Dimensions and Configurations in Individual-Level Preferences and Party Choice’, in PabloBeramendi, SiljaHäusermann, HerbertKitschelt, and HanspeterKriesi (eds.), Politics of Advanced Capitalism. New York: Cambridge University Press, 202–30.

- Julious, Steven A. (2004). ‘Using Confidence Intervals around Individual Means to Assess Statistical Significance between Two Means’, Pharmaceutical Statistics, 3:3, 217–22.

- Koutsogeorgopoulou, Vassiliki (2016). ‘Addressing the Challenges in Higher Education in Norway’, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1285.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, EdgarGrande, MartinDolezal, MarcHelbling, DominicHöglinger, SwenHutter, and BrunoWüest (2012). Political Conflict in Western Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, EdgarGrande, RomainLachat, MartinDolezal, SimonBornschier, and TimotheosFrey (2008). West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Kuppens, Toon, RussellSpears, Antony S. R.Manstead, BramSpruyt, and Matthew J.Easterbrook (2018). ‘Educationism and the Irony of Meritocracy: Negative Attitudes of Higher Educated People towards the Less Educated’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, 429–47.

- Lisi, Marco, and AndréFreire (2012). ‘Political Equality and the Process of Candidate Selection: MPs’ Views in Comparative Perspective’, Representation, 48:4, 373–86.

- Mansbridge, Jane (1999). ‘Should Blacks Represent Blacks and Women Represent Women? A Contingent “Yes”’, The Journal of Politics, 61:3, 628–57.

- Mechtel, Mario (2014). ‘It’s the Occupation, Stupid! Explaining Candidates’ Success in Low-Information Elections’, European Journal of Political Economy, 33, 53–70.

- Mutz, Diana C. (2011). Population-Based Survey Experiments. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Noordzij, Kjell, JeroenVan der Waal, and WillemDe Koster (2019). ‘The Educational Gradient in Trust in Politicians in The Netherlands: A Status-Based Cultural Conflict’, The Sociological Quarterly,60:3, 439–18.

- Norwegian Citizen Panel Wave 12 (2018). Data Collected by Ideas2evidence for Elisabeth Ivarsflaten. Bergen: University of Bergen.

- Pitkin, Hannah F. (1967). The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Reynaert, Herwig (2012). ‘The Social Base of Political Recruitment. A Comparative Study of Local Councillors in Europe’, Lex localis – Journal of Local Self-Government, 10:1, 19–36.

- Schakel, Wouter, and ArmenHakhverdian (2018). ‘Ideological Congruence and Socio-Economic Inequality’, European Political Science Review, 10:3, 441–65.

- Schakel, Wouter, and Daphnevan der Pas (2021). ‘Degrees of Influence: Educational Inequality in Policy Representation’, European Journal of Political Research, 60:2, 418–37.

- Schneider, Sebastian, and MarkusTepe (2011). ‘Dr. Right and Dr. Wrong: Zum Einfluss des Doktortitels auf den Wahlerfolg von Direktkandidaten bei der Bundestagswahl 2009’, Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 52:2, 248–85.

- Skarpenes, Ove, and RuneSakslind (2010). ‘Education and Egalitarianism: The Culture of the Norwegian Middle Class’, The Sociological Review, 58:2, 219–43.

- Sniderman, Paul M. (2011). ‘The Logic and Design of the Survey Experiment: An Autobiography of a Methodological Innovation’, in James N.Druckman, Donald P.Greene, James H.Kuklinski, and ArthurLupia (eds.), Cambridge Handbook of Experimental Political Science. New York: Cambridge University Press, 102–14.

- Spruyt, Bram (2014). ‘An Asymmetric Group Relation? An Investigation into Public Perceptions of Education-Based Groups and the Support for Populism’, Acta Politica, 49:2, 123–43.

- Spruyt, Bram, and ToonKuppens (2015). ‘Education-Based Thinking and Acting? Towards an Identity Perspective for Studying Education Differentials in Public Opinion and Political Participation’, European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 2:3-4, 291–312.

- Stubager, Rune (2010). ‘The Development of the Education Cleavage: Denmark as a Critical Case’, West European Politics, 33:3, 505–33.

- Stubager, Rune (2013). ‘The Changing Basis of Party Competition: Education, Authoritarian–Libertarian Values and Voting’, Government and Opposition, 48:3, 372–97.

- Teele, Dawn Langan, JoshuaKalla, and FrancesRosenbluth (2018). ‘The Ties That Double Bind: Social Roles and Women’s Underrepresentation in Politics’, American Political Science Review, 112:3, 525–41.

- van der Waal, Jeroen, and Willemde Koster (2015). ‘Why Do the Less Educated Oppose Trade Openness? A Test of Three Explanations in The Netherlands’, European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 2:3-4, 313–44.

- Wallace, Sophia J. (2014). ‘Examining Latino Support for Descriptive Representation: The Role of Identity and Discrimination: Latino Support for Descriptive Representation’, Social Science Quarterly, 95:2, 311–27.