Abstract

Cultural backlash research explains voting for populist radical right (PRR) parties mostly by socioeconomic factors and anti-immigration attitudes, neglecting the role of gender values. This study addresses this gap by arguing that gender issue salience triggers backlash against liberalising gender values, resulting in PRR votes by people with conservative gender values. This is tested in the gender-equal context of Sweden by analysing national elections data from 2014 to 2018, comparing voting behaviour before and after a period marked by strong gender issue salience. The study demonstrates that (a) the gap between conservatives’ and liberals’ gender values widens, and (b) conservative gender values predict PRR voting in Sweden in 2018 but not in 2014. These findings suggest that salience of liberalising gender values may trigger backlash, which in turn fuels PRR voting.

Cultural backlash theory explains the rise of PRR parties by social conservatives’ counter-reaction to liberalising values in society, mostly focussing on socioeconomic factors and anti-immigration attitudes (Ivarsflaten Citation2008; Negri Citation2019; Norris and Inglehart Citation2019). Despite strong public debates on gender-related topics, such as the MeToo-debate, and a growing body of literature on the anti-gender movement demonstrating that conservatives mobilise against gender equality and LGBTQI + rights (Kováts Citation2017; Kuhar and Paternotte Citation2018), little research has explored the role of gender values in cultural backlash. This article argues that, in addition to anti-immigration attitudes and socioeconomic factors, gender values provoke cultural backlash.

This article investigates to what extent gender values affect PRR voting when gender issues are salient. Herein, gender issues are political issues that people understand through the lens of cultural ideas about gender or sexuality, such as gender equality policies; and issue salience describes how publicly discussed an issue is and how much it matters to the individual. I draw on cultural backlash and anti-genderism research to theorise the role of gender values in backlash, and the issue salience literature to develop my argument on gender issue salience as a trigger of backlash. The analysis focuses on the case of Sweden. Given its historical political consensus on progressive gender values, Sweden constitutes an interesting case to study backlash against liberalising gender values.

While Sweden is a very gender-equal context, recent events make it a good case for evaluating potential effects of gender issue salience on gender values and PRR voting. Between 2016 and 2018, several events provoked debates about gender equality, including the US election of Donald Trump, known for his sexist statements, the Women’s Marches, and the MeToo-movement. Additionally, in Sweden, a contentious new consent law was passed and a sexual assault scandal in the prestigious Swedish Academy made headlines in 2018. Political issues related to gender were thus highly salient in the build-up to the Swedish national elections in September 2018 (Naurin and Öhberg Citation2019). In these elections, the Sweden Democrats, Sweden’s first successful PRR party and a party promoting relatively conservative gender values, became Sweden’s third-largest party after only two legislative terms in parliament.

This article relates the above-mentioned events to each other in arguing that, as gender issues dominated the Swedish public debate, voters with conservative gender values counter-reacted and became more likely to vote for the Sweden Democrats. Gender values thus became one explanatory factor in the rise of the Sweden Democrats, next to other important predictors of PRR voting such as immigration attitudes. To substantiate this argument, I analyse 2014 and 2018 Swedish National Elections Studies (SNES) survey data, comparing voting behaviour before and after the increase in gender issue salience.

This study addresses the gap in the literature on triggers of cultural backlash (Alter and Zürn Citation2020) by suggesting that issue salience of cultural issues triggers backlash. Furthermore, it addresses the role of gender values in cultural backlash, which has been theorised but remains empirically understudied (Erzeel and Rashkova Citation2017). Moreover, in contrast to most existing studies, the data allows to compare different dimensions of gender values by analysing two gender attitudes indicators over time. The evidence for a backlash against progressive gender values in Sweden suggests that a similar or even stronger backlash in values may occur in less gender-equal democracies, even though it may not translate into PRR voting in political contexts with more gender-conservative mainstream parties. The study thus has implications for research on gender values in cultural backlash more generally.

Gender values in cultural backlash and PRR voting

Burns and Gallagher (Citation2010: 427) define gender values as ‘enduring, consistent ideas about gender and gender relations’. Based on Spierings’ (Citation2020b: 41) definition of the topic of gender as ‘social relations and institutions shaped by gender and sexuality’, I extend their definition to include ideas about sexuality. Individuals’ gender values influence their attitudes towards gender issues, wherein I define gender issues as political issues that people understand through the lens of ‘cultural ideas about gender’ or sexuality (Burns and Gallagher Citation2010: 426). These include women’s and LGBTQI + rights and gender equality policy.

Theoretically, the literature on cultural backlash recognises gender values as a cultural value dimension that divides social conservatives and social liberals (Norris and Inglehart Citation2019). Empirically, research on the US cultural backlash has considered gender values. Bishin et al. (Citation2016) find that salience of gay rights does not trigger backlash in attitudes against gay marriage. However, there is consistent evidence that sexism predicted 2016 Trump votes, which is considered an expression of cultural backlash (Bock et al.Citation2017; Cassese and Barnes Citation2019; Ratliff et al.Citation2019; Valentino et al.Citation2018). Individuals’ conservative gender values thus played a role in the recent US backlash. While European PRR voting is not directly comparable to voting for the Republicans under Trump and European party systems differ from the US two-party system, both represent social conservatives within their respective contexts. The literature on the role of gender values in the Trump elections thus suggests that individuals’ backlash against liberalising gender values may result in increased support for PRR parties in Europe, too.

Research on European cultural backlash in form of growing PRR support mostly focuses on economic factors and immigration attitudes (Amengay and Stockemer Citation2019; Hooghe and Marks Citation2018; Negri Citation2019; Norris and Inglehart Citation2019). While I do not contest these factors’ importance, I argue that gender values are a non-negligible part of European cultural backlash, too. So far, the little existing research on the relationship between gender values and PRR voting has come to contrary conclusions relative to the above-described literature on Trump voting, revealing evidence of PRR voters combining pro-LGBTQI + and nationalist attitudes (Spierings Citation2020a; Spierings et al.Citation2017; Spierings and Zaslove Citation2015). Similarly, Lancaster (Citation2022) shows that progressive gender values increasingly go hand-in-hand with anti-immigration attitudes in the Western European young generation, albeit not in the old generation. Thus, against the common assumption that individuals with conservative immigration attitudes hold similarly conservative attitudes on other cultural issues (Norris and Inglehart Citation2019), PRR voters with progressive gender values seem to constitute a growing group in Western Europe (Lancaster Citation2020).

However, the few existing studies on the role of gender values in backlash have some empirical shortcomings. First, some studies consider only one dimension of gender values, e.g. gay or LGBTQI + rights (Bishin et al.Citation2016; Spierings et al.Citation2017) or sexism (Bock et al.Citation2017; Cassese and Barnes Citation2019; Ratliff et al.Citation2019; Valentino et al.Citation2018), and cannot compare different gender values. Second, some studies rely on small, non-representative population samples (Bock et al.Citation2017; Ratliff et al.Citation2019). Third, previous research on the European context mostly uses data collected prior to the 2016–2018 events sparking increases in gender issue salience that would potentially provoke a backlash against these issues, and are thus unable to capture such a backlash (Lancaster Citation2020; Spierings et al.Citation2017).

PRR parties’ positions on gender issues

Research on PRR parties’ positions on gender issues reveals how these parties combine conservative gender values with the instrumentalisation of progressive positions on gender issues to argue against (Muslim) immigration, creating a complex picture of partly contradictory party positions. As regards PRR parties’ conservative positions, Towns (Citation2020: 272) argues that ‘a transnational constellation of self-identified Western actors that mobilise against gender equality’ has emerged in Western democracies. Research on the global rise of anti-genderism since the 2000s, a movement of various actors opposing the liberalisation of gender values, supports this argument (Kováts Citation2017; Kuhar and Paternotte Citation2018). According to Towns (Citation2020: 285), PRR parties constitute a ‘major hub’ in this movement, which fights abortion rights, LGBTQI + rights and so-called ‘gender ideology’, where ‘gender ideology’ is a term used in opposition to feminist and LGBTQI + rights movements (Corredor Citation2019; Mayer and Sauer Citation2017).

PRR parties are a channel for the movement and its followers to seek political representation of conservative gender values. Most PRR parties take conservative views on gender issues, promoting the traditional, heteronormative family model, in which women’s main role is to take care of the family and household. Along with these views comes an opposition to feminism and gender equality policies regarding the labour market, abortion and LGBTQI + rights (Akkerman Citation2015; Kantola and Lombardo Citation2021; Verloo Citation2018).

At the same time, many PRR parties claim to protect gender equality and the LGBTQI + community in face of the alleged threat of Muslim immigration, for instance, by opposing the usage of the headscarf and emphasising problems of honour-related crime and forced marriage (De Lange and Mügge Citation2015; Farris Citation2017; Morgan Citation2017; Spierings Citation2020a). Progressive positions on gender issues are thus instrumentalised to oppose (Muslim) immigration.

Paradoxically, PRR parties may therefore attract both voters who counter-react against and those who endorse liberalising gender values, which corroborates the above presented research on PRR voters with progressive gender values. However, scholars agree that PRR parties’ endorsement of progressive gender values solely serves the purpose to exclude migrants and does not challenge patriarchal heteronormative structures in society. Rather, women are still portrayed as mothers and care-takers, responsible of raising the nation’s future generation, and to be protected by men who still hold power positions in the family and society to ensure the nation’s stability (Norocel Citation2013; Towns et al.Citation2014). Opposing immigration on the grounds of migrants’ alleged commitment of gender-based violence does not contradict PRR parties’ otherwise patriarchal, heteronormative positions on gender issues. PRR parties thus represent voters aiming at upholding or reversing to patriarchal, heteronormative societal structures.

Cultural backlash theory

Norris and Inglehart (Citation2019) explain the rise of PRR parties by cultural backlash theory. Accordingly, the rise of PRR parties results from cultural backlash, which is defined as social conservatives’ counter-reaction to the ‘silent revolution’ of socially liberal values. Social conservatives are individuals who hold traditional beliefs cherishing faith, family and the nation, aspiring to economic and physical safety, stability and order, and prioritising group conformity over individual freedom and self-expression (Norris and Inglehart Citation2019: 33–4). The silent revolution is driven by generational change, increasing education and urbanisation, economic development and increasing ethnic diversity and gender equality, which evoke socially liberal values and respective changes in mainstream values. These values include support for multiculturalism, climate action and feminism. Conservatives’ counter-reaction to these value changes is defined as cultural backlash, which can result in conservatives’ support for socially conservative parties. The rise of European PRR parties exemplifies how backlash in values is expressed in voting behaviour (Norris and Inglehart Citation2019).

While these cultural values are theorised to include gender values (Norris and Inglehart Citation2019), empirically, the role of gender values in cultural backlash remains understudied. Since these values may however affect voting behaviour and the rise of PRR parties, their study is crucial to understanding current political developments in various democracies. Building on the above literature on gender values in PRR voting and PRR parties’ respective positions, this article argues that PRR parties attract voters who counter-react against liberalising gender values and empirically tests this argument.

Issue salience as trigger of cultural backlash

While cultural backlash theory explains why backlash occurs and among whom, it fails to determine when cultural backlash occurs. So far, research identifies cultural backlash by evaluating people’s vote choice in retrospect but cannot predict it. Norris and Inglehart (Citation2019) vaguely suggest that backlash occurs as a function of the spread of socially liberal values, economic and physical security, immigration rates and prevailing ethnic diversity in a society. Alter and Zürn (Citation2020) emphasise the need for further research on triggers of cultural backlash. I speak to this gap in research by proposing issue salience as a trigger of cultural backlash.

The literature defines issue salience differently. On the contextual level, issue salience is defined as how much an issue is discussed in the political debate (Adams Citation1997; Dahlström and Esaiasson Citation2013) or in the media (Wojcieszak et al.Citation2018), often as a result of some related high-profile event (Bishin et al.Citation2016). On the individual level, issue salience is described as the importance that voters ascribe to an issue in their vote choice (Bélanger and Meguid Citation2008; Dennison Citation2020) or how much concern an individual expresses for an issue (Neundorf and Adams Citation2018). Issue salience is thus a matter of the context, i.e. to what extent an issue is discussed in the public debate, and the individual level, i.e. to what extent this public debate affects individuals. As individuals are influenced by their social context (Campbell Citation2013), these two levels of issue salience can be expected go hand in hand.

Being among the first scholars to systematically study backlash in attitudes in response to a salient event, Bishin et al. (Citation2016: 627) argue that ‘salience is a key component in triggering backlash’, because it ‘serves to galvanise negative predispositions into negative opinion by heightening the sense of threat, loss, or change to the status quo’. While they find no evidence for backlash in attitudes towards gay marriage, they suggest that a backlash may manifest itself in political behaviour rather than attitudes. The argument that issue salience triggers changes in attitudes and political behaviour corroborates research arguing that, as an issue becomes salient, individuals perceive it as more important and more information on the issue becomes available (Walgrave and Lefevere Citation2013). They thus form stronger attitudes towards the issue (Dennison Citation2020), which may then affect their voting behaviour. In line with this argument, Dennison (Citation2020) finds that immigration issue salience positively affects voting for anti-immigration parties. Similarly, Neundorf and Adams (Citation2018) find that environmental issue salience increases the support for Green parties. Issue salience may thus increase support for parties that represent a distinct position and ‘hold a reputation of competence’ on the issue (Bélanger and Meguid Citation2008: 477).

The literature thus suggests that issue salience triggers a) the formation of stronger attitudes on the salient issue, and b) increased support for parties with distinct party positions on the salient issue. As described in the previous section, PRR parties promote distinctly more conservative positions on gender issues than other parties. As voters adapt stronger attitudes towards gender issues, they may re-evaluate political parties and their own vote choice in light of these attitudes. Considering that PRR parties represent voters with conservative gender values, and gender issue salience may increase the importance that voters ascribe to gender issues, voters with conservative gender values may be more inclined to vote for PRR parties on the grounds of these values when gender issues are salient. I therefore arrive at the following hypotheses:

H1: When gender issues are salient, the difference in gender values between PRR voters and other voters widens.

H2: When gender issues are salient, conservative gender values are positively related to PRR voting.

By investigating these hypotheses, I contribute to cultural backlash theory by (a) exploring the so far understudied role of gender values in cultural backlash, and (b) studying the role of issue salience as a trigger of cultural backlash in attitudes and voting behaviour.

The case of Sweden

Sweden constitutes an interesting case for this analysis because of its long-standing remarkable performance on gender equality indicators, which has however not prevented the rise of a PRR party that both advocates traditional gender values and endorses gender equality as a national value. Given the long history of relatively gender-equal socialisation of Swedes, there is a consensus on progressive gender values in society that cuts across all political camps, excluding the recently growing radical right (Bergqvist Citation2015). Sweden has ranked first on the European Gender Equality Index since the index was first computed in 2005 (EIGE Citation2020) and is one of the most progressive countries regarding LGBTQI + rights worldwide (ILGA World Citation2019). These achievements build upon a long history of gender equality policy, starting in the 1930s (Bergqvist Citation2015). Since the 1960s and 1970s, both social democratic and conservative-led governments have introduced policies to encourage female labour force participation and an individual earner-carer model through parental leave regulations, public childcare and individual taxation of married couples.

Sweden’s remarkably long history of progressive gender equality policy across political camps should thus produce a progressive gender equality norm. In such a context, feminist mobilizations are less norm-challenging and therefore unlikely to provoke backlash, compared to less gender-equal contexts. Indeed, even in previous periods of feminist mobilisation in Sweden, no politically noticeable backlash occurred. For instance, the early 1990s, described as ‘a period with escalation in feminist mobilisation in Sweden’ (Öhberg & Wängnerud Citation2014: 62), did not ensue notable political backlash. Quite the opposite, it was a Liberal/Conservative government that first introduced the so-called ‘daddy month’, i.e. the earmarking of one month of parental leave for each parent, in 1995. Then again, given that mainstream conservative parties form part of the gender-progressive consensus in Swedish politics, conservative Swedish voters who do counter-react against feminist mobilizations despite their gender-equal socialisation are particularly likely to vote for the Sweden Democrats, as I will further explain in the next section.

The years prior to the 2018 Swedish elections marked another period of feminist mobilisation. With the 2016 Trump election and subsequent Women’s Marches, the 2017 MeToo-campaign, and the 2018 new Swedish consent law and sexual assault scandal in the Swedish Academy, women’s rights issues were highly salient in the public debate (Naurin and Öhberg Citation2019). The consent law redefined rape and sexual assault as sexual acts that are not explicitly consensual, creating a debate on how consent can be (dis)proven. Meanwhile, a sexual assault scandal in the renowned Swedish Academy was widely discussed in national media and eventually led to resignation of several board members of the Academy and the cancellation of the 2018 Nobel Prize for literature.

Given Sweden’s historical consensus on progressive gender values and the salience of the 2016–2018 gender-related debates, the 2014 and 2018 Swedish elections constitute an interesting case for this analysis. On the one hand, gender-progressive Swedes are unlikely to counter-react against feminist mobilizations. Evidence of such backlash in Sweden would thus suggest that even stronger backlash against feminist mobilizations may occur in less gender-equal societies, even though it may not translate into PRR voting in political contexts with more gender-conservative mainstream parties. The case selection of Sweden thus constitutes an empirical contribution to the study of gender values in cultural backlash more generally. On the other hand, Swedes who do counter-react against feminist mobilizations are particularly likely to vote for the Sweden Democrats, given the lack of gender-conservative alternatives among Swedish political parties.

The Sweden Democrats

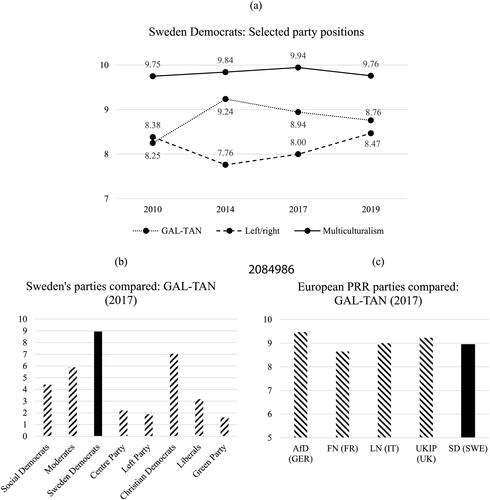

Founded in 1988, the Sweden Democrats first entered the Swedish parliament in 2010. By 2018, the party reached 17.53 percent of votes. Immigration, nationalism and multiculturalism have been the party’s most salient issues (Bakker et al.Citation2020; Polk et al.Citation2017). As shows, the party takes a highly traditional-authoritarian-nationalist (TAN) stand on these issues. On the GAL-TAN dimensionFootnote1, it stands out in comparison with other Swedish parties (see ) and ranks similarly to other Western European PRR parties (see ).

Figure 1. The Sweden Democrats (SD) as PRR party.

Source: Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Bakker et al.Citation2015; Polk et al.Citation2017; Bakker et al.Citation2020).

Note: On a scale from 0 to 10, 10 indicates ‘traditional/authoritarian/nationalist’ (GAL-TAN), ‘extreme right’ (Left/right) and ‘strongly in favor of assimilation as opposed to multiculturalism’ (Multiculturalism). See online appendix A for a more detailed explanation of the GAL-TAN dimension. For , I use 2017 (rather than 2019) data to capture how the Sweden Democrats were assessed prior to the 2018 elections.

Although gender issues are not on top of the Sweden Democrats’ agenda, the party’s positions on gender issues are evident in party manifestos, verbal statements, parliamentary debates, debate articles in Swedish newspapers and politicians’ blog entries (Mulinari and Neergaard Citation2017; Norocel Citation2013; Citation2016; Pettersson Citation2017). The Sweden Democrats advocate women’s protection from the alleged threat of Muslim immigration, but contest gender equality measures in all other contexts (Norocel Citation2013; Towns et al.Citation2014). For instance, as stated in their 2018 manifesto, the Sweden Democrats oppose gender quotas, the regulation of how parents share their parental leave, as well as ‘gender theory’ (Sverigedemokraterna Citation2018). The rejection of gender theory can be linked to the anti-gender movement’s opposition to so-called ‘gender ideology’. At the same time, the party recognises gender equality as a national trait and problematises honour-related gender-based violence and the Islamic full veil, portraying Muslims as a threat to gender equality (Norocel Citation2016).

Likewise, Kehl (Citation2018) argues that the Sweden Democrats radically opposed LGBTQI + rights until the 2000s. Accordingly, since the mid-2000s, LGBTQI + rights are only protected in the party’s discourse to construct an alleged Islamic threat. Even the Sweden Democrats’ own LGBTQI + organisation, founded in 2014, argues that LGBTQI + people should integrate into heteronormative society rather than challenging its norms (Kehl Citation2018). The party’s 2018 manifesto more cautiously emphasises the nuclear family as the best family model, while recognising other models. Overall, within the progressive context of Sweden, the Sweden Democrats constitute a good example of how PRR parties adapt conservative and partly contradictory positions on gender issues and therein distinguish themselves from mainstream conservative parties.

While acknowledging that the Sweden Democrats’ main issue is immigration, Mulinari and Neergaard (Citation2017) argue that, because the party’s stance on gender issues differs strongly from the Swedish mainstream, its success can be considered a counter-reaction to Sweden’s successful women’s movement. This reasoning supports the argument that liberalising gender values trigger backlash, even in the gender-equal context of Sweden.

Research design, data and methods

My research design is based on the comparison of electoral data before and after the increase in gender issue salience evoked by gender-related public debates between 2016 and 2018. The increase in gender issue salience can be demonstrated in different ways. For instance, Swedish exit polls ask voters how important they considered different political issues in their vote choice, including gender equality. In the 2014 elections, 38 percent perceived gender equality as a very important issue in their vote choice, and the issue ranked ninth out of ten (Holmberg et al. 2015). Responses to the same question were similar in 2010 and 2006. Strikingly, by 2018, gender equality ranked 3rd out of 10, with 48 percent of voters describing the issue as very important in their vote choice (Oscarsson et al.Citation2018). Voters’ perceived importance of gender equality in their vote choice thus considerably increased between 2014 and 2018, which may be ascribed to the strong gender-related public debates during that period.Footnote2

Another way to demonstrate increasing gender issue salience is to assess changes in the frequency of gender-related Google searches undertaken by people in Sweden over time, approximating to what extent people in Sweden seek for and receive information on gender issues. Online appendix B presents a Google Trends analysis revealing stark increases in search frequencies of gender-related issues before the 2018 elections. This further supports my argument that gender issue salience increased between 2014 and 2018, which can in turn affect the relationship between gender values and PRR voting.

Model specification

In order to analyse gender values and voting behaviour, I use 2014 and 2018 cross-sectional SNES survey data (see online appendix C for more information on the survey, online appendix D for summary statistics, and online appendix E for pairwise correlations). My analysis does not allow me to derive any causal inference, given the possibility of reverse causality. As the Sweden Democrats’ voters encounter PRR-dominated fora and information sources, their partisanship may lead them to adopt more conservative gender values. Still, in light of the above-outlined background, and given the lack of research on gender values in cultural backlash, a correlational analysis constitutes a relevant empirical contribution to the literature.

My main independent variables are respondents’ gender values. I approximate gender values by attitudes towards two particular gender issues, i.e. the proposal to redistribute power from men to women and the proposal to strengthen LGBTQI + rights (see online appendix C for the question wording). The first indicator is chosen because it is controversial enough to spark disagreement even in the progressive context of Sweden. While all parties emphasise gender equality as a national Swedish trait, not all parties agree with measures redistributing power between men and women, such as gender quotas or the regulation of fathers’ parental leave. The proposal to redistribute power from men to women represents a concrete threat to men’s status quo by raising the possibility of compromising their power, thus potentially triggering conservative backlash.

The second indicator is the only available indicator to capture attitudes towards LGBTQI + rights. In contrast to male-female power redistribution, LGBTQI + rights challenge heteronormative views on sexuality and gender identity, involving a more abstract threat to the norm of heteronormativity. As strengthening LGBTQI + rights does not directly affect people who are not LGBTQI+, it represents a less tangible threat to heterosexual cis-gender men than male-female power redistribution. Distinguishing between these two indicators allows the comparison between a tangible threat to the status quo of a hitherto powerful population group (i.e. men) and an abstract threat to heteronormativity as the predominant social norm. It is noteworthy that the 2016–2018 increase in gender issue salience was related to events that mostly regard male-female power dynamics rather than LGBTQI + rights. In line with this study’s theoretical argument, the analysis may thus find stronger effects for the indicator on male-female power redistribution. Both indicators are measured on a 0–10 scale, were 10 indicates strong agreement and thus more progressive attitudes.

In order to test the hypothesis that the gender value gap increases between PRR voters and other voters when gender issues are salient (H1), I regress the gender attitudes indicators on an interaction term between voting for the Sweden Democrats and a year dummy. The year dummy captures the increase in gender issue salience between 2014 and 2018. While this model enables me to test my hypotheses, I do not suggest a direction of causality by testing the effect of voting for the Sweden Democrats on gender attitudes.

To test the hypothesis that conservative gender values are positively related to PRR voting when gender issues are salient (H2), I regress voting for the Sweden Democrats on the gender attitudes indicators, using pooled logistic regression analysis. I control for gender, age, rural/urban residence, religiosity, marital status, social class, income, education, public sector employment, immigration attitudes, left-right ideology, political trust and green attitudes (see online appendix G for a detailed explanation of the control variables). I also include an interaction term between the gender attitudes indicators and a year dummy, which captures the increase in gender issue salience between 2014 and 2018.Footnote3

Based on post-estimation tests, I remove deviance outliers and include a dummy variable for leverage outliers.Footnote4,Footnote5 I weight the observations using the weights for party choice provided by SNES. Finally, I control for pre-/post-election survey response, as the election outcome may affect responses. As for all survey data, the data is subject to social desirability bias.

Results

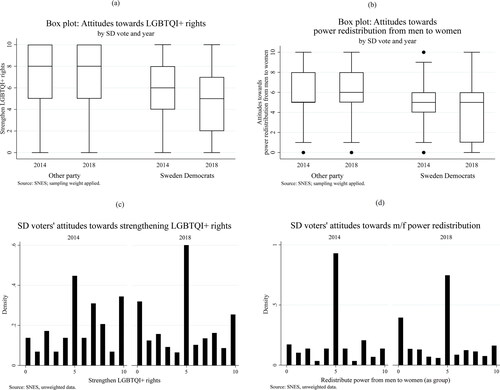

The descriptive analysis reveals that voters of the Sweden Democrats hold consistently less progressive gender attitudes than other voters (). Further, the divergence between the two voters groups’ attitudes increases between 2014 and 2018, as voters of the Sweden Democrats shift towards more conservative attitudes, on average (). In contrast, other voters barely change in their attitudes towards LGBTQI + rights and shift towards more support for male-female power redistribution between 2014 and 2018 (). Balance tables (online appendix F) confirm the significance of the differences between the two voters groups’ attitudes. further demonstrate that the proportions of the Sweden Democrats’ voters who strongly oppose LGBTQI + rights and male-female power redistribution increase notably between 2014 and 2018. The graphs thus support hypothesis 1 that PRR voters counter-react against liberalising gender values, resulting in a widened gender value gap between PRR voters and other voters, when gender issues are salient.

The graphs furthermore suggest that the gap in attitudes towards male-female power redistribution increased to a greater extent than the gap in attitudes towards LGBTQI + rights (balance tables confirm this finding, see online appendix F), which may reflect the fact that the salient issues mostly concerned male-female power dynamics.

Regression analyses

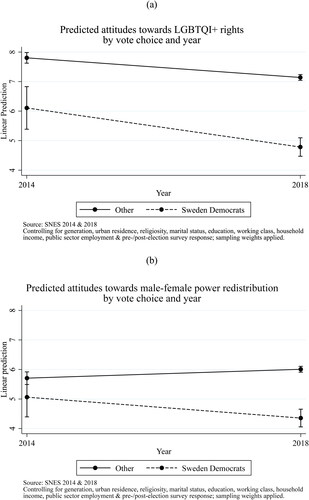

Pooled OLS regression analysis confirms that, between 2014 and 2018, the gender value gap widened between the Sweden Democrats’ voters and other voters (). In 2014, the Sweden Democrats’ voters score on average 1.325 points lower on attitudes towards LGBTQI + rights than other voters (equal to 0.53 std. dev., p-value < 0.01, model 1 in online appendix H). In comparison, the difference between the Sweden Democrats’ voters’ and other voters’ attitudes towards LGBTQI + rights increased to 1.984 points by 2018 (equal to 0.68 std. dev., p-value < 0.01, see model 3 in online appendix H for the same model using a different reference category). visualises the predicted attitudes towards LGBTQI + rights.

demonstrates that, in 2014, the Sweden Democrats’ voters did not differ significantly from other voters in their attitudes towards male-female power redistribution. However, in 2018, the Sweden Democrats’ voters scored on average 1.453 points lower than other voters on these attitudes (equal to 0.53 std. dev., p-value < 0.01, see model 4 in online appendix H). The gap between the Sweden Democrats’ voters’ and other voters’ attitudes thus widened for both analysed gender attitudes, and more strongly so for attitudes towards male-female power redistribution. Again, this finding supports hypothesis 1 that PRR voters counter-react against liberalising gender values, resulting in widening gender values gaps between PRR voters and other voters, when gender issues are salient.

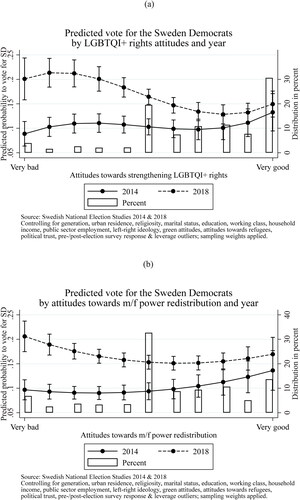

Logistic regression analysis supports hypothesis 2 that conservative gender values predict PRR voting when gender issues are salient (see online appendix I for the models). demonstrates clear differences between the 2014 and 2018 relationships between gender attitudes and the respective predicted probabilities to vote for the Sweden Democrats (see online appendix I for the exact predicted probabilities). In 2014, voters with conservative gender attitudes had a predicted probability of less than 10 percent to vote for the Sweden Democrats and were by 6–7 percentage points less likely to vote for the Sweden Democrats than voters with progressive gender attitudes. The fact that voters with progressive gender attitudes were slightly more likely to vote for the Sweden Democrats provides evidence for homonationalism and femonationalism among the electorate, which corroborates previous literature. The generally weak relationship in 2014 supports the argument that gender attitudes did not play an important role in vote choice when gender issues were not salient.

By 2018, conservative gender attitudes are related to a probability to vote for the Sweden Democrats of approximately 20 percent, which equals more than a doubling in predicted probability to vote for the Sweden Democrats between 2014 and 2018 among the most gender-conservative voters. The curvilinear functional forms further suggest that especially voters with conservative gender attitudes become more likely to vote for the Sweden Democrats. In contrast, voters with progressive gender attitudes do not significantly change in their predicted probability to vote for the Sweden Democrats. Thus, the 2014–2018 increase in predicted probability to vote for the Sweden Democrats is driven by voters with conservative gender attitudes.

Interestingly, there is no significant difference between younger and older generations’ odds of voting for the Sweden Democrats (see models 1–5, online appendix I). Instead, Baby Boomers are consistently more likely to vote for the Sweden Democrats than the Interwar generation. Even though the Interwar generation holds the most conservative gender attitudes (see online appendix H), which is particularly true for attitudes towards LGBTQI + rights, these attitudes do not translate into the highest odds of PRR voting.

Finally, the argument that the Sweden Democrats constitute an option for voters who counter-react against progressive gender values, in contrast to established conservative parties (e.g. the Moderates, the Christian Democrats), is further supported by evidence showing that the relationship between gender attitudes and voting for conservative mainstream parties did not significantly change between 2014 and 2018 (see online appendix J). Multinomial logistic regression further demonstrates that the relationship between gender attitudes and voting for the Moderates or Christian Democrats differs significantly from the relationship between gender attitudes and voting for the Sweden Democrats. This difference is more pronounced in 2018 than in 2014 (see online appendix J).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that gender issue salience in Sweden increased prior to the 2018 elections, providing the bases for analysing gender values and voting in light of increased gender issue salience. Analysing the 2014 and 2018 Swedish elections reveals that the gender value gap widens between voters of the Sweden Democrats and other voters. Furthermore, conservative gender attitudes predict voting for the Sweden Democrats in 2018, however not in 2014, controlling for main predictors of PRR voting. The relationship between conservative gender attitudes and voting for the Sweden Democrats may thus be moderated by gender issue salience.

Some alternative explanations to these findings require consideration. First, an alternative explanation for changes in the relationship between gender values and voting for the Sweden Democrats between 2014 and 2018 would be that the Sweden Democrats became more conservative on gender issues during that time. However, the literature suggests that the opposite is the case (e.g. Kehl Citation2018).

Second, an alternative explanation for voters of the Sweden Democrats adapting on average more conservative gender values could be that the biggest Swedish mainstream conservative party, the Moderates, became more conservative. Consequently, the Moderates may have attracted voters with moderately conservative gender values, leaving more radically conservative voters to the Sweden Democrats. However, the Moderates’ increased conservatism is explained by their positions on immigration rather than gender issues. Between 2014 and 2019, according to CHES data (Bakker et al.Citation2020; Polk et al.Citation2017), the Moderates moved from 2.61 to 8.0 on a 0–10 scale, where higher values equal more restrictive immigration policy positions. In contrast, the Moderates moved from 3.21 to 2.81 on a 0–10 scale where 0 equals strong support for liberal policies on social lifestyle (e.g. homosexuality). Sweden’s mainstream conservative party thus became even slightly more liberal on gender issues.Footnote6 This rules out the alternative explanation that the mainstream conservative party attracted voters with moderately conservative gender values, leaving more radically conservative voters to the Sweden Democrats.

Finally, another alternative explanation would be that the Sweden Democrats increased their party discourse on gender issues in reaction to the ongoing public debates. In consequence, their discourse would influence their voters. To alleviate this concern, I conduct dictionary-based quantitative text analysis on all press releases (n = 993) issued by the Sweden Democrats between 2009 and 2018 (see online appendix K). The analysis reveals that the party’s press releases addressed gender issues less frequently between 2014 and 2018 than before. It seems that the party restricted their formal communication on salient gender issues, distinguishing itself from the outspokenly gender-progressive Swedish mainstream. This supports the argument that gender issue salience in the public debate, rather than increased party discourse on salient gender issues, drive changes in the relationship between gender values and PRR voting. As the Sweden Democrats’ positions were known to voters, for instance through media coverage of informal party communicationFootnote7 and party manifestos, the party still constituted an option for voters who disagree with the mainstream.

Given the lack of support for these alternative explanations, this article’s findings contribute to the literature in at least four ways. First, I theorise and attempt to demonstrate that issue salience triggers backlash and widens existing value gaps, which contributes to research on triggers of backlash. While previous research investigates this mechanism for the immigration issue (Dennison Citation2020), this study suggests that the same mechanism may hold for gender issues. Exploiting real-world increases in gender issue salience supports the research design. However, any inference on the effects of issue salience is limited, as I cannot meaningfully measure it at the individual level and I only analyse two time periods. Changing the wording of survey questions on issue salience could address the problem of measuring individual-level issue salience over time in future research. Rather than asking for the most important issues in individual vote choice, surveys may ask for the perceived importance of a list of issues. Such question wording would help capture issues that usually are not named among the most important issues in vote choice, including gender issues.

Second, I show that gender values play a role in cultural backlash and PRR voting, which has so far received little scholarly attention. This supports the arguments that a) the anti-gender movement is an expression of cultural backlash, and b) conservative backlash to liberalising gender values contributes to the rise of PRR parties. Simultaneously, my data also shows some evidence of homonationalism and femonationalism, which however did not grow between 2014 and 2018. The rise of PRR parties thus partly reflects an increasing opposition to gender equality measures and strengthening LGBTQI+ rights.

Third, I add to the literature by comparing different dimensions of gender values. My results suggest that voters’ attitudes diverged more strongly on male-female power redistribution than on LGBTQI + rights, which may reflect the fact that the 2016–2018 public debates addressed male-female power redistribution. However, the predicted probabilities to vote for the Sweden Democrats based on the two gender attitudes increased to a comparable degree. This finding suggests that issue salience did not only affect attitudes towards the discussed issues but also towards closely related issues, as contemporary feminism often includes LGBTQI + issues.

Finally, my results suggest that middle-aged rather than elderly individuals are most likely to vote for the Sweden Democrats, which contradicts cultural backlash theory (Norris and Inglehart Citation2019). This finding aligns with recent research (Schäfer Citation2021) questioning generational value change as the main mechanism behind cultural backlash. Future research may explore other mechanisms behind cultural backlash.

Overall, this study shows that, rather than creating a consensus in society for more progressive gender values, the 2016–2018 gender-related debates widened existing gender value gaps and provoked backlash among social conservatives in the short-term. Future research may investigate whether this backlash persists equally strongly in the long-term.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that gender issue salience can trigger a conservative backlash against liberalising gender values, and this backlash can fuel PRR support. More precisely, it explores the role of gender values in cultural backlash between 2014 and 2018 in Sweden, as expressed by voting for the Sweden Democrats. Due to various gender-related events, gender issue salience increased during that time period. At the same time, the gender value gap widened between voters of the Sweden Democrats and other voters. While gender values were not related to voting for the Sweden Democrats in 2014, conservative gender values predicted voting for the Sweden Democrats in 2018, controlling for main predictors of PRR voting. I therefore argue that gender issue salience triggered cultural backlash. As the public debate was dominated by these issues, liberalising gender values provoked social conservatives’ counter-reaction, resulting in a backlash against gender values. This backlash was in turn reflected in the rise of the Sweden Democrats.

This study’s main contribution to cultural backlash theory is twofold: First, I suggest that issue salience of social liberalising values triggers cultural backlash, thereby addressing the lack of research on triggers of cultural backlash. Second, I demonstrate that gender values play a role in cultural backlash, whereas previous research has mostly explained cultural backlash by socioeconomic factors and anti-immigration attitudes.

Empirically, this study’s contribution is threefold: Its research design enables the comparison of attitudes and vote choice before and after real-world increases in issue salience, supporting the validity of my argument. Second, in contrast to much previous research, it tests and compares different dimensions of gender values. Finally, I study the gender-equal context of Sweden, where backlash against feminist mobilisation is unexpected. The fact that backlash against gender values occurred in this context suggests that such backlash in attitudes may be similar or stronger in other democracies, even though it may not translate into PRR voting in political contexts with more gender-conservative mainstream parties.

Politically, my findings imply that large-scale debates on liberalising gender issues can provoke short-term conservative counter-reactions and societal divisions in gender values, rather than creating agreement on progressive gender values. Thus, even though many PRR parties partly take supposedly progressive stances by claiming to protect women’s and LGBTQI + rights from the alleged threat of immigration, their voters continue to oppose women’s empowerment and LGBTQI + rights.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.3 MB)Acknowledgements

I thank Amy Alexander, Nicholas Charron, Elena Leuschner, Jana Schwenk and Luca Versteegen, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments throughout different stages of the manuscript. I also thank Henrik Oscarsson, Jakob Ahlbom and Richard Karlsson from the Swedish National Election Studies team for their support with the data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gefjon Off

Gefjon Off is a PhD student in Political Science at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Her PhD dissertation explores backlash against feminism and populist radical right voting. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 See online appendix A for a more detailed explanation of the GAL-TAN dimension.

2 The SNES survey contains a question measuring issue salience but only allows for three issues to be named. Gender issues are mentioned too rarely to include this variable as individual-level salience measure (only 2.59% of 2018 answers regard gender equality).

3 The Akaike information criterion (AIC) suggests that the models significantly improve when including a cubic term of the LGBTQI + rights variable (AIC: 1923.584 with vs. 1926.902 without cubic term) and a quadratic term of the variable on male-female power redistribution (AIC: 1943.252 with vs. 1947.168 without quadratic term).

4 2 deviance residual outliers out of 3,923 observations are dropped based on the rule of thumb that deviance residuals should not exceed 3 standard deviations, thus incorporating 99.7% of all observed data (based on the assumption of normal residual distribution). Both dropped observations regard voters of the Sweden Democrats who oppose restrictive refugee immigration policy, contradicting the party’s most salient position. Very likely, these respondents were not paying attention to the survey questionnaire, which justifies their exclusion from the analysis.

5 471 (model 2, table 2) and 475 (model 4, table 2) out of 3,921 (remaining) observations are considered leverage outliers (i.e. leverage > 3× mean leverage).

6 Multinomial logistic regression (online appendix J) shows that the relationship between immigration attitudes and voting for the Moderates/ Christian Democrats differs significantly from the relationship between immigration attitudes and voting for the Sweden Democrats. However, this difference slightly decreases between 2014 and 2018. In contrast, the relationships between voting for these party groups and gender attitudes diverge between 2014 and 2018. This supports the CHES assessment that the Moderates became more restrictive towards immigration but more liberal towards gender issues, thereby becoming more similar to the Sweden Democrats on the former and more distinct from the Sweden Democrats on the latter issue.

7 In interviews, party leader Åkesson expressed worry about the MeToo-movement resulting in a people’s court (TV4 2017), and described the Swedish Academy’s sexual assault scandal as minor problem compared to crime (Sveriges Radio Citation2018). The journalist and author Anna-Lena Lodenius (Citation2018) cites various other examples of media reports on politicians of the Sweden Democrats who express opposition to gender equality policy, mostly prior to 2014 but also during later years.

References

- Adams, Greg D. (1997). ‘Abortion: Evidence of an Issue Evolution’, American Journal of Political Science, 41:3, 718–37.

- Akkerman, Tjitske (2015). ‘Gender and the Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis of Policy Agendas’, Patterns of Prejudice, 49:1–2, 37–60.

- Alter, Karen J., and MichaelZürn (2020). ‘Conceptualising Backlash Politics: Introduction to a Special Issue on Backlash Politics in Comparison’, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 22:4, 563–84.

- Amengay, Abdelkarim, and DanielStockemer (2019). ‘The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Meta-Analysis of Structural Factors’, Political Studies Review, 17:1, 30–40.

- Bakker, Ryan, Catherine De Vries, Erica Edwards, Liesbet Hooghe, SethJolly, GaryMarks, JonathanPolk, JanRovny, MarcoSteenbergen, and Milada A.Vachudova (2015). ‘Measuring Party Positions in Europe: The Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File, 1999–2010’, Party Politics, 21:1, 143–52.

- Bakker, Ryan, LiesbetHooghe, SethJolly, GaryMarks, JonathanPolk, JanRovny, MarcoSteenbergen, and Milada A.Vachudova (2020). 2019 Chapel Hill Expert Survey. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina.

- Bélanger, Éric, and Bonnie M.Meguid (2008). ‘Issue Salience, Issue Ownership, and Issue-Based Vote Choice’, Electoral Studies, 27:3, 477–91.

- Bergqvist, Christina (2015). ‘The Welfare State and Gender Equality’, in JonPierre (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Swedish Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 55–68.

- Bishin, Benjamin G., Thomas J.Hayes, Matthew B.Incantalupo, and Charles A.Smith (2016). ‘Opinion Backlash and Public Attitudes: Are Political Advances in Gay Rights Counterproductive?’, American Journal of Political Science, 60:3, 625–48.

- Bock, Jarrod, JenniferByrd-Craven, and MelissaBurkley (2017). ‘The Role of Sexism in Voting in the 2016 Presidential Election’, Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 189–93.

- Burns, Nancy, and KatherineGallagher (2010). ‘Public Opinion on Gender Issues: The Politics of Equity and Roles’, Annual Review of Political Science, 13:1, 425–43.

- Campbell, David E. (2013). ‘Social Networks and Political Participation’, Annual Review of Political Science, 16:1, 33–48.

- Cassese, Erin C., and Tiffany D.Barnes (2019). ‘Reconciling Sexism and Women’s Support for Republican Candidates: A Look at Gender, Class, and Whiteness in the 2012 and 2016 Presidential Races’, Political Behavior, 41:3, 677–700.

- Corredor, Elizabeth S. (2019). ‘Unpacking ‘Gender Ideology’ and the Global Right’s Antigender Countermovement’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 44:3, 613–38.

- Dahlström, Carl, and PeterEsaiasson (2013). ‘The Immigration Issue and anti-Immigrant Party Success in Sweden 1970–2006: A Deviant Case Analysis’, Party Politics, 19:2, 343–64.

- De Lange, Sarah L., and Liza M.Mügge (2015). ‘Gender and Right-Wing Populism in the Low Countries: Ideological Variations across Parties and Time’, Patterns of Prejudice, 49:1–2, 61–80.

- Dennison, James (2020). ‘How Issue Salience Explains the Rise of the Populist Right in Western Europe’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 32:3, 397–420.

- EIGE (2020). Gender Equality Index 2020: Sweden. Vilnius: European Institute for Gender Equality.

- Erzeel, Silvia, and Ekaterina R.Rashkova (2017). ‘Still Men’s Parties? Gender and the Radical Right in Comparative Perspective’, West European Politics, 40:4, 812–20.

- Farris, Sara R. (2017). In the Name of Women’s Rights: The Rise of Femonationalism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Holmberg, Sören, PerNäsmanTorbjörn Gustafsson, and Sveriges Television AB (2015). ‘VALU 2014 – SVT:S Vallokalsundersökning Riksdagsvalet 2014’, Svensk nationell datatjänst.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and GaryMarks (2018). ‘Cleavage Theory Meets Europe’s Crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the Transnational Cleavage’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:1, 109–35.

- ILGA World (2019). Maps – Sexual Orientation Laws. Geneva: The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association.

- Ivarsflaten, Elisabeth (2008). ‘What Unites Right-Wing Populists in Western Europe? Re-Examining Grievance Mobilization Models in Seven Successful Cases’, Comparative Political Studies, 41:1, 3–23.

- Kantola, Johanna, and EmanuelaLombardo (2021). ‘Strategies of Right Populists in Opposing Gender Equality in a Polarized European Parliament’, International Political Science Review, 42:5, 565–79.

- Kehl, Katharina (2018). ‘In Sweden, Girls Are Allowed to Kiss Girls, and Boys Are Allowed to Kiss Boys’: Pride Järva and the Inclusion of the ‘LGBT Other’ in Swedish Nationalist Discourses’, Sexualities, 21:4, 674–91.

- Kováts, Eszter (2017). ‘The Emergence of Powerful Anti-Gender Movements in Europe and the Crisis of Liberal Democracy’, in MichaelaKöttig, RenateBitzan, and AndreaPetö (eds.), Gender and Far Right Politics in Europe. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG, 175–89.

- Kuhar, Roman, and DavidPaternotte (2018). Anti-Gender Campaigns in Europe: Mobilizing Against Equality. London: Rowman & Littlefield International.

- Lancaster, Caroline M. (2020). ‘Not so Radical after All: Ideological Diversity among Radical Right Supporters and Its Implications’, Political Studies, 68:3, 600–16.

- Lancaster, Caroline M. (2022). ‘Value Shift: Immigration Attitudes and the Sociocultural Divide’, British Journal of Political Science, 52:1, 1–20.

- Lodenius, Anna-Lena (2018). Antifeministerna: Sverigedemokraterna Och Jämställdheten. Stockholm: Arenagruppen.

- Mayer, Stephanie, and BirgitSauer (2017). ‘Gender Ideology in Austria: Coalitions Around an Empty Signifier’, in RomanKuhar and DavidPaternotte (eds.), Anti-Gender Campaigns in Europe: Mobilizations against Equality. London: Rowman & Littlefield International, 23–40.

- Morgan, Kimberly J. (2017). ‘Gender, Right-Wing Populism, and Immigrant Integration Policies in France, 1989–2012’, West European Politics, 40:4, 887–906.

- Mulinari, Diana, and AndersNeergaard (2017). ‘Doing Racism, Performing Femininity: Women in the Sweden Democrats’, in MichaelaKöttig, RenateBitzan, and AndreaPetö (eds.), Gender and Far Right Politics in Europe. Springer International. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG, 13–27.

- Naurin, Elin, and PatrikÖhberg (2019). ‘Kvinnors Och Mäns Politiska Åsikter Och Intresse under 30 År’, in UlrikaAndersson, BjörnRönnerstrand, PatrikÖhberg, and AnnikaBergström (eds.), Storm Och Stiltje. Gothenburg: Göteborgs universitet: SOM-institutet, 395–408.

- Negri, Fedra (2019). ‘Economic or Cultural Backlash? Rethinking Outsiders’ Voting Behavior’, Electoral Studies, 59, 158–63.

- Neundorf, Anja, and JamesAdams (2018). ‘The Micro-Foundations of Party Competition and Issue Ownership: The Reciprocal Effects of Citizens’ Issue Salience and Party Attachments’, British Journal of Political Science, 48:2, 385–406.

- Norocel, Ov C. (2013). ‘Give Us Back Sweden!’ A Feminist Reading of the (Re) Interpretations of the Folkhem Conceptual Metaphor in Swedish Radical Right Populist Discourse’, NORA – Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 21:1, 4–20.

- Norocel, Ov C. (2016). ‘Populist Radical Right Protectors of the Folkhem: Welfare Chauvinism in Sweden’, Critical Social Policy, 36:3, 371–90.

- Norris, Pippa, and RonaldInglehart (2019). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambrige: Cambridge University Press.

- Öhberg, Patrik, and LenaWängnerud (2014). ‘Testing the Impact of Political Generations: The Class of 94 and Pro‐Feminist Ideas in the Swedish Riksdag’, Scandinavian Political Studies, 37:1, 61–81.

- Oscarsson, Henrik, PerNäsman, EvaLandahl, and SörenHolmberg and Sveriges Television AB (2018). VALU 2018 – SVT:S Vallokalsundersökning Riksdagsvalet 2018. Gothenburg: Svensk Nationell Datatjänst.

- Pettersson, Katarina (2017). ‘Ideological Dilemmas of Female Populist Radical Right Politicians’, European Journal of Women’s Studies, 24:1, 7–22.

- Polk, Jonathan, JanRovny, RyanBakker, EricaEdwards, LiesbetHooghe, SethJolly, JelleKoedam, FilipKostelka, GaryMarks, GijsSchumacher, MarcoSteenbergen, MiladaVachudova, and MarkoZilovic (2017). ‘Explaining the Salience of anti-Elitism and Reducing Political Corruption for Political Parties in Europe with the 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey Data’, Research & Politics, 4:1.

- Ratliff, Kate A., LizRedford, JohnConway, and Colin T.Smith (2019). ‘Engendering Support: Hostile Sexism Predicts Voting for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton in the 2016 US Presidential Election’, Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 22:4, 578–93.

- Schäfer, Armin (2021). ‘Cultural Backlash? How (Not) to Explain the Rise of Authoritarian Populism’, British Journal of Political Science, 1–17.

- Spierings, Niels (2020a). ‘Homonationalism and Voting for the Populist Radical Right: Addressing Unanswered Questions by Zooming in on the Dutch Case’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 33:1, 171–82.

- Spierings, Niels (2020b). ‘Why Gender and Sexuality Are Both Trivial and Pivotal in Populist Radical Right Politics’, in GabrieleDietze and JuliaRoth (eds.), Right-Wing Populism and Gender. Bielefeld: transcript-Verlag, 41–58.

- Spierings, Niels, MarcelLubbers, and AndrejZaslove (2017). ‘Sexually Modern Nativist Voters’: Do They Exist and Do They Vote for the Populist Radical Right?’, Gender and Education, 29:2, 216–37.

- Spierings, Niels, and AndrejZaslove (2015). ‘Gendering the Vote for Populist Radical-Right Parties’, Patterns of Prejudice, 49:1–2, 135–62.

- Sverigedemokraterna (2018). Valmanifest. Stockholm: Sverigedemokraterna.

- Sveriges Radio (2018). När Ska SD Komma in i Stugvärmen, Jimmie Åkesson?. Ekots Lördagsintervju, available at https://sverigesradio.se/avsnitt/1054348.

- Towns, Ann (2020). ‘Gender, Nation and the Generation of Cultural Difference across ‘the West’, in AndrewPhillips and ChristianReus-Smit (eds.), Culture and Order in World Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 271–93.

- Towns, Ann, ErikaKarlsson, and JoshuaEyre (2014). ‘The Equality Conundrum: Gender and Nation in the Ideology of the Sweden Democrats’, Party Politics, 20:2, 237–47.

- TV4 (2017). Jimmie Åkesson (SD) Om Metoo-Kampanjen: ‘Jag Ser Vissa Risker’. Stockholm: TV4 Play.

- Valentino, Nicholas A., CarlyWayne, and MarziaOceno (2018). ‘Mobilizing Sexism: The Interaction of Emotion and Gender Attitudes in the 2016 US Presidential Election’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 82:S1, 799–821.

- Verloo, Mieke (2018). Varieties of Opposition to Gender Equality in Europe. New York and London: Routledge.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, and JonasLefevere (2013). ‘Ideology, Salience, and Complexity: Determinants of Policy Issue Incongruence between Voters and Parties’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties, 23:4, 456–83.

- Wojcieszak, Magdalena, RachidAzrout, and ClaesDe Vreese (2018). ‘Waving the Red Cloth: Media Coverage of a Contentious Issue Triggers Polarization’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 82:1, 87–109.