Abstract

Public opinion polarisation can impair society’s ability to reach a democratic consensus in different political issue areas. This appears particularly true when the polarisation of opinions coincides with clearly identifiable social groups. The literature on public opinion polarisation has mostly focussed on the US two-party context. We lack concepts and measures that can be adapted to European countries with multi-party systems and multi-layered group identities. This article proposes a conceptualisation of polarisation between groups in society. It presents a measure that captures the overlap of ideology distributions between groups. The two-step empirical framework includes hierarchical IRT models and a measure for dissimilarity of distributions. The second part presents an empirical application of the measure based on survey data from Switzerland (1994–2016), which reveals insightful dynamics of public opinion polarisation between party supporters and education groups.

Political polarisation has been a much debated topic in European countries and the USA in recent years. Yet, many different political developments are summarised under this term. Most research focuses on the US context, and reveals an extreme case of homogenisation within and polarisation between the two dominant parties and their voters (see e.g. Mason Citation2018). This opposition to the other party on the elite-level (Poole and Rosenthal Citation1984) and the voter-level (Baldassarri and Park Citation2020; Fiorina and Abrams Citation2008) extends beyond ideological differences, as Republicans and Democrats have developed strong and socially consequential identification with their respective political camps (Iyengar et al. Citation2012). Political polarisation increasingly includes important aspects of American culture and society (DellaPosta et al. Citation2015; Mutz and Rao Citation2018).

In Europe, the evidence is not as clear-cut. While earlier European research found a general trend of convergence rather than polarisation (Adams et al. Citation2012a, Citation2012b), more recent studies claim that the rise of extreme parties, and in particular right-wing populist parties, can lead to a more polarised general public in many European countries (Bischof and Wagner Citation2019; Silva Citation2018). But the premise that this is reflective of general public opinion polarisation in European is debated (Adams et al. Citation2012; Borbáth et al. Citation2022; Down and Wilson Citation2008; Munzert and Bauer Citation2013).

The adaptation of concepts and measures for public opinion polarisation from the US-context to European multi-party systems poses a number of challenges. One key question: is how can we grasp polarisation in Europe, where the political space is more complex and multi-layered? Existing research on European opinion polarisation has used conceptualisations and measures that focus on the overall spread of preferences in society. But this perspective likely hides the micro-level mechanisms and dynamics of public opinion polarisation. And it does not acknowledge that public opinion polarisation is particularly challenging if it coincides with clearly identifiable social groups (DiMaggio et al. Citation1996; Hobolt et al. Citation2021). From our perspective, it is especially relevant to focus on the polarisation between political groups if we intend to understand polarisation in Europe.

In this article, we present a redefined concept and measure for group-based public opinion polarisation.

We argue that to understand the micro-level mechanisms and dynamics of political polarisation we need to take into account ideological polarisation between as well as within groups. To this end, we propose an empirical framework that focuses on the distributions of ideology. Our measure of group-based polarisation captures the distance between ideology distributions of politically relevant groups in society. The perspective on distribution entails that not only the ideological mean difference between groups matters, but also the coherence, or variance, of the groups’ ideology.

We combine hierarchical item response models (Zhou Citation2019) with a distance measure between probability distributions (Bhattacharyya Citation1946). The item response model can be used with ordinal survey items about policy-related questions and estimates ideology traits of respondents. The hierarchical part of the model permits researchers to define groups by including covariates to model both the mean and the spread of the distribution of group ideology. The resulting estimates of group-based ideology distributions can be used to evaluate the extent of polarisation by comparing the distance between the distributions. The flexible hierarchical model further allows to model temporal dynamics in the case when rolling cross-section survey data is available.

In the second part, we present an application of the empirical approach. We study the polarisation between party supporters and education groups in Switzerland from 1993 to 2016. We rely on surveys following Swiss direct-democratic votes (Kriesi et al. Citation2017) that include a set of identical questions on several cultural and economic policies. The results show that polarisation in Switzerland between party supporter groups has increased between the 1990s and mid-2000s and decreased afterwards. Tertiary-educated supporters of the SVP and SP have been the primary source of this pattern.

The article makes a number of contributions to the literature. It takes insights from two central literatures, cleavage theories and public opinion research, to develop a notion of group-based polarisation that is particularly well-suited for the multi-party context in Europe. With this, it is the first to conceptualise group-based public opinion polarisation based on the overlap of ideology distributions between groups. Second, it introduces a flexible measurement method to pin down the dynamic evolution of group-based polarisation. Future research can rely on this method to study group-based polarisation in different contexts and between different types of groups. Finally, the article provides empirical evidence on the extent of public opinion polarisation in Switzerland over the period from 1994 to 2016.

Two perspectives on group-based political conflict

Political polarisation has been a much debated topic in public and scientific discourse in recent years. While definitions differ widely, depending on discipline and research interest, one common element in most concepts is that political polarisation involves opposition of two (or more) groups that might be purely ideologically divided (Fiorina and Abrams Citation2008) or emotionally opposed (Iyengar et al. Citation2012, Citation2019). In addition, while political conflict is inherent and necessary in democracies (Schattschneider Citation1960), the challenges are expected to become more serious if conflicts consolidate, different lines of conflict overlap, and if they are closely associated with salient social identities (DiMaggio et al. Citation1996; Hobolt et al. Citation2021).

If we see polarisation as group-based conflict, two perspectives are important. The macro-sociological literature on political cleavages has been a prominent view on political conflict structures in Europe. It sheds light on structural realignment between social groups and parties at the end of the 20th century (see e.g. Bartolini and Mair Citation2007; Bornschier Citation2010; Bornschier et al. Citation2021; Kriesi Citation1998; Kriesi et al. Citation2008, Citation2012). By contrast, in public opinion research, studies of political polarisation have focussed on the dynamics of mass opinion change (e.g. DiMaggio et al. Citation1996; Fiorina and Abrams Citation2008). Both views – the cleavage perspective and research on opinion polarisation – are interested in social and political change. However, while the former seeks to explain big structural realignments that might happen over a long time period, the latter puts more emphasis on within-group dynamics and incremental change.

Structural conflicts and political cleavages

The cleavage perspective seeks to answer two questions: What are the important structural elements (i.e. divisive factors) that characterise the cleavage? And how does the conflict structure translate into politics? A political cleavage is defined as a politically mobilised structural conflict (see e.g. Kriesi Citation1998); in this sense, a social conflict only becomes relevant if it is taken up, supported and even amplified by political organisations. This view has a particular interest in critical junctures, phases in history during which we see disruption of existing structures, and the emergence of a new equilibrium (Hooghe and Marks Citation2018).

For a long time the cleavage-centred perspective on political competition was the dominant approach to study political conflict in multiparty systems (Kriesi Citation2008; Lipset and Rokkan Citation1967). The cleavage perspective has brought valuable insight with regard to the ideological divide and realignment in Europe since the mid-20th century. According to these authors, the cultural revolution in the 1960s indicates a first ‘realignment’ of the ideological space (Inglehart Citation1977; Kitschelt Citation1994). An important factor was the new social movements, which introduced socially liberal values that were contradictory to the traditional conservative and authoritarian values of a large part of societies at the time. Hence, the structure of ideological conflict changed from a purely religious cleavage to one between socially liberal and authoritarian values (Kriesi Citation1998; Kriesi et al. Citation2008).

At the beginning of the 21st century, the cleavage perspective has focussed on the new political conflicts that developed as a consequence of changes in the labour market (Oesch Citation2008; Oesch and Rennwald Citation2018), as well as of cultural and economic globalisation (Kriesi et al. Citation2008; Walter Citation2021). A number of studies argued that a new value conflict between the ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ of globalisation has emerged since the late 1990s. Again, it is argued that this realignment integrates new elements into an earlier conflict – the liberal vs. conservative divide. The most critical issues in this new conflict dimension are disputes regarding immigration, (national) traditions and European integration (Bornschier Citation2010; Kriesi et al. Citation2006, Citation2008, Citation2012; Oesch Citation2008; Oesch and Rennwald, Citation2018). The recent crises in Europe, – first the economic and debt crisis (ca. 2010–2015) and shortly after the migration crisis (2015) – have led to a deepening of this ‘transnational conflict’ on the party level, albeit with different political outcomes in different regions across Europe (Hooghe and Marks Citation2018; Hutter and Kriesi Citation2019).

This new divide seems however less clear-cut when we focus on voters and individual ideology. First, despite the wealth of survey data on voter preferences and values in Europe, it remains an open question to what degree public opinion has become more polarised in Europe since the late 20th century; in other words, to what degree the backlash against globalisation is manifest in voters’ ideology (Walter Citation2021). Second, an extensive definition of the ‘cultural’ conflict, one that combines the opposition between socially liberal vs. conservative values (e.g. Norris and Inglehart Citation2019), and the conflicts around immigration and European integration into one single dimension – has become less useful for explaining current political divides. European societies have become more socially liberal overall, but a fierce and politically salient conflict still revolves around issues of migration, border control and the trade-off between national self-determination vs. international cooperation (De Vries Citation2018; Lancaster Citation2022).

With its focus on long-term structural realignment, the cleavage perspective can inform us about the nature of political conflict, and the type of groups that are opposed – typically social status or occupational groups. It is less suited, however, to investigate the distribution of preferences within the opposing groups. In other words, cleavage theory focuses more on ‘the ways in which disagreement is expressed’ and less on the ‘extent of disagreement’ (DiMaggio et al. Citation1996: 692). In this sense, the cleavage approach can describe large shifts in politically mobilised conflict in a given country over a long time period. We need other empirical approaches, however, to investigate the degree of public opinion polarisation in a given country and time, and in particular, the dynamics of polarisation on the micro-level, that are often developing over a shorter time period. In more technical terms, we would need an appropriate empirical strategy to answer questions such as: Are the two distributions flat or narrow? How large is the overlap between them? Eventually, the distributional properties of political cleavages might indicate whether a specific social division will develop into a full-blown political cleavage or remain a temporal phenomenon that fades after political competition has shifted to another salient issue concern (Wagner and Meyer Citation2014).

Dynamics of mass opinion polarisation

Research on public opinion polarisation has almost exclusively focussed on the US-American context. Early studies have examined the consequences of elite polarisation, in other words, to what degree the increasing polarisation on the party level is mirrored among the mass public (Layman et al. Citation2006; Poole and Rosenthal Citation1984). Polarisation is generally (most often implicitly) defined as increasing bimodality of an ideological distribution (left-right or specific issues), caused by a movement of politicians, parties, or people, from the centre towards both extremes of the distribution (e.g. Fiorina and Abrams Citation2008). In this sense, a large part of the public opinion literature investigates polarisation as a process rather than a state (DiMaggio et al. Citation1996).Footnote1

Related to this definition of opinion polarisation, it is an ongoing dispute among US-scholars whether public opinion has actually become more polarised in recent decades. In particular, many researchers argue that contrary to the popular view, political attitudes have not polarised, i.e. not become more extreme, but Democratic and Republican voters have become more homogeneous in their preferences and at the same time more apart from each other, a development that is generally referred to as ‘partisan sorting’ (Fiorina and Abrams Citation2008; Fiorina and Levendusky Citation2006). Partisan sorting is especially pronounced among politically sophisticated citizens (Hetherington Citation2009) and has further increased since the Great Recession (Brooks and Manza Citation2013). In general, the American literature provides a fruitful basis for studies of political polarisation in Europe. The concept of partisan sorting in particular offers an interesting starting point and can be applied to other types of social groups to detect fractions on the sub-population level.

There is a smaller but growing literature concerned with mass opinion polarisation in Europe. The British case, which is most similar to the US party system, has long been portrayed as the ‘mirror’ image of the US in terms of political polarisation, with a striking depolarisation on the party level, and a weakening relationship between voter ideology and party preferences (decline of partisan sorting) (Adams et al. Citation2012a, Citation2012b; Evans and Tilley Citation2017). However, as in the US literature, it was harder to pin down mass opinion depolarisation, and the results were less clear-cut in this regard (Adams et al. Citation2012a, Citation2012b; Milazzo et al. Citation2012). More recent evidence points to a reversal of this trend, and increased partisan sorting since the financial crisis (Cohen and Cohen Citation2021). Again, trends in mass opinion seem less clear.

The empirical assessment of opinion polarisation poses already fundamental measurement problems in a two-party context and these are of course even worse in an ideological space that is characterised by multi-party competition.Footnote2 Only a few studies have taken a dynamic perspective on public opinion polarisation and find mixed results (Adams et al. Citation2012; Down and Wilson Citation2008; Munzert and Bauer Citation2013). While earlier research pointed to a moderate depolarisation of European publics, there is growing evidence that the rise of right-wing populist parties has led to more polarised publics in countries where these parties entered parliament (Bischof and Wagner Citation2019; Silva Citation2018). Similarly, but reversing the causal argument, the theory of ‘cultural backlash’ states that ideological polarisation regarding cultural issues lies at the root of the populist parties’ success in Europe and the USA (Norris and Inglehart Citation2019).

In this approach – in contrast to the cleavage literature, the main interest lies in mass public opinion or opinion of voters. Thus, party identity is seen as the most important group identity that matters for political polarisation. Polarisation is described as a (gradual) process, as movement to ideological extremes. Further, while in the macro-sociological cleavage theory changes in the social and labour market structure are usually seen as the cause of realignment between social groups and parties, which may lead to political polarisation, it is an ongoing debate in the public opinion literature whether elite-level polarisation causes public opinion divergence or vice versa (e.g. Cohen and Cohen Citation2021). Finally, one important difference between the two literature strands lies in the conceptualisation of the ideological space, which has consequences for measurement. Studies of political cleavages are interested in the dimensionality of the ideological space, whereas polarisation research focuses on general ideology – mostly traditional left–right – or specific attitudes.

Group-based public opinion polarisation

The cleavage literature and research on public opinion polarisation highlight different aspects of political conflict, and we think that a combination of both approaches provides a fruitful basis for the concept of group-based opinion polarisation. As our previous discussion shows, both approaches are complementary. The polarisation approach is able to detect the distributional aspects of value conflicts, but often remains on the population level. Cleavage research, on the other hand, provides insights into structural conflicts, while no attention is paid to the distributional properties of the preference gap. Empirically, the focus lies on the macro level and structural change. When interested in individual preferences, research in the cleavage theory tradition focuses on between-group distances, measured by difference in group means. We argue that a dynamic view of public opinion polarisation should combine both, a view on the structure of group-based conflict, as well as the distributional properties of the preference divide.

We present a novel approach to public opinion polarisation. First, unlike much of the existing literature in the field of political behaviour, we conceptualise polarisation as a divergence in key political issues between groups in a society. Second, this view on group conflict differs from earlier cleavage research insofar as we analye preferences of groups as distributions of ideology. Ideology serves a latent dimension that influences and summarises an ‘interrelated network of beliefs, opinions and values’ (Jost 2006: 310) about political issues. We argue that only when taking the full properties of ideology distributions between groups into account, we can grasp the extent of group conflict.

We conceptualise political polarisation as the decreasing overlap or increasing dissimilarity between group-based distributions of ideology. The overlap between two distributions is greater if (1) either one of both distributions is flat (groups are less ideologically homogeneous) or (2) the distance between the average positions is low. In this, we follow research interested in the relation between polarisation and conflict, which considers groups as more important actors than individuals when studying polarisation, since homogeneity within groups is crucial for potential societal conflict (Esteban and Ray Citation1994; Esteban and Schneider Citation2008). More specifically, theoretical foundations for the use of a group-based definition of polarisation are based on the idea that group conflict is particularly strong when opposing groups are internally homogeneous, since homogeneous groups have a higher capacity to mobilise and organise their interest compared to heterogeneous groups (DiMaggio et al. Citation1996). Applying this perspective to opinion polarisation, we assume that ideological differences are more consequential with clearly separated ideological group distributions. This view aligns closely with the cleavage perspective that sees organised group interests as the central foundation of conflict dimensions in Europe.

When studying multiple groups – e.g. in a multiparty system – it is straightforward to consider the overlap of each pair of groups, in addition to an overall distribution of preference on the population level. Finally, this concept also allows to detect sub-group polarisation, e.g. within partisan groups. It can be applied to both types of polarisation that are discussed in the literature: opinion polarisation due to preference shifts, and due to group sorting, that is, realignment between group characteristics and preferences. The following examples illustrate this.

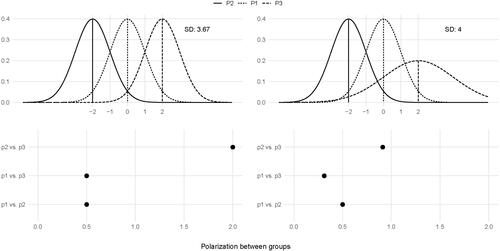

depicts the hypothetical ideology distribution of equally sized groups on one ideological dimension. It illustrates two different cases of group-based polarisation. Below the distributions, we indicate the distance between the distributions, which is calculated using Bhattacharyya distance (see measurement section). The left panel shows a hypothetical case of ideological polarisation with three groups: In this situation, p2 and p3, have shifted to the extremes (left and right), so that the expected values of both distributions are now −2 and 2, respectively. The groups remain ideologically homogeneous (same variance). The distance measure for between-group polarisation indicates that polarisation between p1 and p2 as well as between p1 and p3 is slightly increased, compared to a situation where all preferences overlap. Most importantly, we see a high level of polarisation between p2 and p3. Because of the group’s movements to the left and right, the overall variance (mass polarisation) has increased as well (SD = 3.67, compared to 1.17 in case of full overlap).

The panel on the right illustrates a slightly different situation, in which p2 moves to the left, and p3 moves to the right but becomes less ideologically coherent. As a consequence, the overlap between p3 and the two other groups is larger than in the previous situation, in other words, between-group polarisation is lower (as indicated by the lower distance values shown in the bottom half of the graph). It is important to note, however, that the distance in means between each pair of groups is the same in both situations. Consequently, when focussing on this simple distance measure, we will overestimate the degree of polarisation between the groups. A global measure of polarisation (i.e. the overall variance) might be equally misleading: In case of similar group size (our example), the overall variance is larger in the right panel (SD = 4) compared to the left panel (SD = 3.67), even though the dissimilarity of positions is lower.

The illustrations in underline several important aspects that have to be taken into account when studying polarisation of public opinion. First, it is necessary to consider both, an overall population level (e.g. the overall variance of positions), and the level of sub-groups, because polarisation may be ‘hidden’ when between-group polarisation is ignored. Group-based polarisation could occur because of preference shifts and/or due to a sorting mechanism.Footnote3 The literature has been mainly interested in partisan sorting, but the sorting mechanism could happen with regard to any social groups, more broadly related to social, cultural or ethnic identities (see, for example, Mason Citation2018). Second, when studying polarisation between sub-groups of a society, it is important to study not only the differences between the mean of ideological positions of two groups – the general approach in cleavage research – but also to look at the distributional properties of between-group polarisation. When the distance between group means increases, but within-group unity is low (large within-group variance, as shown in the right panel), it may be less consequential for society, because the likelihood that the differences will lead to conflict is lower, and more heterogeneous groups have a lower capacity to mobilise (DiMaggio et al. Citation1996). Finally, the illustrations make a more general case for the importance of polarisation studies in public opinion: The two types of polarisation depicted in give an example of how we might miss important changes when focussing solely on aggregate shifts of public opinion. While the average ideological position might not have changed (0 in all examples), there could still be important divides in society that can only be detected by studying the distributional properties of public opinion.

In sum, we argue that it is important to take a view on polarisation that considers different aspects of between- and within-group conflict. The perspective on polarisation we present here takes into account the full properties of ideology distributions, in contrast to approaches that focus on single measures such as the distance of group means or the overall variance of ideological positions on the population level.Footnote4

Measuring group-based opinion polarisation

This section introduces an empirical framework to study our concept of group-based polarisation based on survey data. Our measurement strategy includes two steps: (1) estimation of respondents’ ideology and properties of subgroup ideological distributions, (2) calculation of a polarisation measure. Both steps maintain the idea that the distribution of ideology within and across groups is central to our understanding of group-based polarisation. We build on a recently proposed hierarchical item response model (Zhou Citation2019), and combine it with a measure of distribution similarity (Bhattacharyya Citation1946). We describe the intuition of the empirical framework in the following and provide more mathematical details in the Online Appendix A.1.

A widely used method to estimate ideological positions from survey data is item response theory (IRT). IRT methods consider binary, ordinal, or nominal answers to survey questions and estimate a statistical model in which both item parameters and latent trait of the respondent are unknown. In public opinion research, the items are often batteries of policy questions that measure respondents’ attitudes towards different policy proposals, such as the taxation issues or abortion rights (see, for example, Treier and Hillygus Citation2009). In these applications, the latent trait describes a summary measure of these policy attitudes and is hence interpreted as latent ideology. Recently, Zhou (Citation2019) proposed hierarchical item response models to analyse how citizens’ political ideologies differ among and between groups, evolve or vary across regions.Footnote5

The hierarchical item response model approach is perfectly suited for our purpose as it permits us to define groups of respondents. This method combines measurement and analysis by scaling items to a latent ideology and simultaneously estimating the effects of individual characteristics on it. The model allows both the mean and variance of the normally distributed ideology measure to vary based on covariates. The inclusion of covariates defines groups of respondents and estimates the mean ideology of these groups and the in-group variance. For example, to analyse the distribution of educational groups, a dummy variable that indicates a respondent’s educational attainment can be included in the estimation. The education groups’ means and variances in ideology can then be constructed from the parameter estimates. Hence, the model offers a flexible instrument for analysing patterns of ideological polarisation between different groups.

The hierarchical item response model can further integrate the variation of the latent ideology of groups over time. The timing of the survey can be a covariate of the hierarchical model. By interacting time covariates with the group covariates (such as educational attainment), we can model varying group means and variances of the ideology measure over time. A linear interaction specification would allow group means and variances to increase, stay stable, or decrease over time. A more flexible version incorporates the possibility that the centre and spread of ideological positions of a group can go up and down. In our applications, we employ B-splines that combine higher degree polynomials with cut-points (so-called knots) to have considerable flexibility in the evolution of group ideology (see also Zhou Citation2019).Footnote6 We evaluate on the use of B-splines for our application in the Online Appendix B.3 and select a parsimonious model based on the Bayesian information criterion for our applications.

The hierarchical item response model yields parameter estimates of the distribution of group-based latent ideology over time, which is assumed to be normally distributed. Based on these measures of ideological distribution we can calculate the degree of polarisation between groups. Following our definition of polarisation as decreasing overlap between distributions of ideology, we suggest to use the distance between probability distributions in form of the Bhattacharyya distance. The Bhattacharyya distance is a widely used measure to evaluate the similarity between distributions and has desirable properties for our applications. It is defined as the negative logarithm of the Bhattacharyya coefficient, which measures the overlap of two distributions by multiplying the densities of two distributions over the sampling space. The measure takes both the mean and the spread of the distribution into account, and as a result gives information about the overlap of the two groups. While the Bhattacharyya coefficient is defined on the interval 0 (no overlap) to 1 (complete overlap), the Bhattacharyya distance is defined from 0 (zero distance, the distributions are identical) to positive infinity (complete distance between the distributions with no overlap). Hence, as a distance measure the lowest possible value is zero, indicating perfect overlap and similarity. In our interpretation this would mean that two groups have identical ideological distributions and are not polarised at all. Higher values indicate smaller overlap and higher degrees of polarisation. For the comparison of our normally distributed group ideology the Bhattacharyya distance has a closed form solution and researchers can calculate it from the estimated group means and variances directly (see Online Appendix A.3).Footnote7

The comparison of the polarisation between groups further leads to an aggregated group-based measure of polarisation. For an aggregated polarisation measure we calculate a weighted average of the different group comparisons. A sensible weighting scheme is the chance that two randomly drawn people in the population are from a pair of groups. This can be achieved by multiplying the group sizes of the two groups for each comparison, such that two large groups have a higher weight in the aggregated measures, compared to two small groups. For example, a comparison between two partisan groups with polarisation of 0.6 is weighted by the product of their groups’ sizes. Partisan group one is 30% of the total population and partisan group two of size 20%, giving a weight of 0.06. Two different smaller partisan groups with a polarisation measure of 1.5 and of same size 10% only receive a weight of 0.01. For the aggregated polarisation measure we then sum up the weighted polarisation comparisons (0.06 × 0.6 + 0.01 × 1.5). This is important for the interpretation of the aggregated measure as the group sizes can influence* polarisation. If an extreme group grows in size, this substantially influences the aggregated polarisation for identical ideological distributions of the groups. For more details on the calculation of the aggregated measure please see Online Appendix A.4.

Public opinion polarisation in Switzerland between education and partisan groups

In order to illustrate the usefulness of our approach in studying public opinion polarisation, we apply the measurement strategy to Switzerland in the last three decades. We select Switzerland because it has been central in the discussion about the degree of polarisation in Western Europe. In Switzerland, the party system has polarised considerably since the 1990s, such that the distance between parties on the right (Swiss People’s Party (SVP)) and on the left (Social Democrats (SP) and Green Party) is larger than in most European countries (Bochsler et al. Citation2015; Traber Citation2015). But the finding of increased elite polarisation has so far not been mirrored in studies of public opinion polarisation. This makes Switzerland an interesting case to provide evidence for group-based polarisation.

While our approach could be extended to different groups of interest, our analysis relies on social groups that are distinguished along two dimensions: education level and partisan support. These two characteristics represent some of the main groups of interest in the two literatures we discussed, the cleavage theory and public opinion research of polarisation. Education levels and labour-market relevant skill levels are important features of cleavage theory. This embodies a bottom-up view of political polarisation, whereby structural change – such as changes in the labour market or educational upgrading – leads to heightened salience of education for ideological positions, and thus to ideological polarisation between education groups.Footnote8 Party identity plays a central role in the public opinion literature, especially in debates regarding polarisation in the U.S. This literature focuses on political determinants of polarisation, and generally takes a more top-down perspective on ideological conflict. We combine both perspectives by focussing on education and partisan support as two group characteristics. This also allows us to study how parties are internally divided along educational groups. We evaluate the potential to apply the measure to alternative group definitions in the discussion section of the article.

Data and operationalisation

For Switzerland, the analyses rely on the VoxIt survey which contains individual-level information on citizens’ interests, knowledge and political attitudes in the context of Swiss national votes. The survey is conducted two or three weeks after each ballot is held and it includes a representative sample of approximately 1000 voters (Kriesi et al. Citation2017). Because the Swiss party system has polarised substantially since the beginning of the 1990s, we restrict the time frame of the analyses to the years from 1993 to 2016.

The unit of analysis is citizens’ political attitudes on policy relevant issues. We consider only opinion questions that were asked consistently throughout the entire time period. Consequently, the data includes a total of 10 opinion questions with different numbers of response categories. The questions cover various topics, such as national defence, redistribution, equal rights for men and women and attitudes towards protection of the environment (see Online Appendix B.1).

We distinguish between two education groups, based on the highest completed degree: respondents with tertiary education (including university degree as well as colleges of higher education) and those with lower education levels.Footnote9 We use party supporter groups to identify party closeness, which is operationalised by the question which party represented in the National Council or Council of States most closely corresponds to the respondents’ views and preferences.Footnote10 The focus lies on the five main parties in Switzerland: Green Party (GPS), Social Democratic Party (SP), Christian Democratic People’s Party (CVP), The Liberals (FDP), Swiss People’s Party (SVP). All remaining parties, no party identification and non-responses are summarised in an additional category ‘others’.Footnote11

Results: group-based opinion polarisation in Switzerland

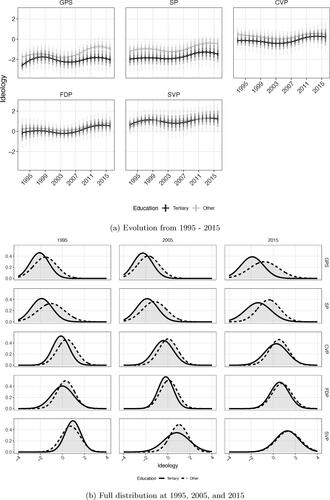

Based on the above described hierarchical item response model, we estimate political ideology of partisan and education groups over time. shows the estimated distributions of ideology on one dimension among lower and higher educated supporters of the GPS, SP, CVP, FDP and SVP from 1993 to 2016. The bars show 10%, 20%, 50% and 80% of the estimated ideological distribution around the mean.

first illustrates how the ideology of party supporters changes over time. Overall, preferences are quite stable. We see a small right-wing shift in all parties in the mid-2000s, and a reverse movement (again on a low scale) towards slightly more leftist positions in the latest years. Second, depicts the coherence within parties, that is, between voters with different education levels. Left parties are more internally divided than right-wing parties, in particular the SVP, which is the most cohesive.

Polarisation between education groups within parties is shown in more detail in . Here we plot the full distributions of both education groups for three points in time – 1995, 2005 and 2015. Again, it is striking how the internal cohesion of parties differs. In addition, highlights several important aspects of sub-group polarisation: First, tertiary educated voters appear more left-wing than voters with lower education levels, which is the case in particular in left-wing parties, but also in the more centre-right parties. Supporters of the right-wing SVP mostly overlap in their ideological views, regardless of their education. Second, illustrates that the variance of ideological distributions varies considerably between parties, but also over time. For example, supporters of the two most extreme parties, the Greens on the left and the SVP on the right, with a tertiary degree were a very homogeneous ideological group in the 1990s but have become less cohesive in recent years (see also Online Appendix B.4).

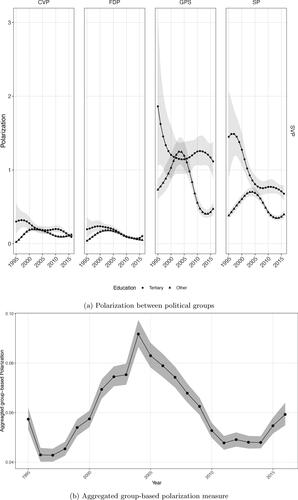

In a second step, we calculate the polarisation measure based on the ideological distributions. There are many ways to compare the groups. We chose to look more closely at polarisation between parties here, by focussing on polarisation between supporters of the most right-wing party (SVP) and the rest.Footnote12 Note that our measure of polarisation depends not only on the difference in average ideology, but also on the internal cohesiveness (i.e. the variance) of the ideological distributions. contains our measure for polarisation between party supporters over time. The measures compare each education group separately. For example, the dots in the most left panel show polarisation between CVP supporters with a tertiary degree and SVP supporters with a tertiary degree. In general, polarisation is most pronounced between supporters of the left parties and the SVP, but much more so between the highly educated. Reflecting the ideological split between education groups in the left parties, those supporters with lower education appear less distant from supporters of the SVP with similar education. It is striking how this difference is only visible among the left parties. The overlap between supporters of the FDP and the SVP is considerably high, notwithstanding their education, and remains so over the whole time period.

We finally calculate a global measure of political polarisation, which is the average distance weighted by group means. shows an increase in polarisation from the 1990s until the mid-2000s, and depolarisation afterwards. The spike in average group-based polarisation around 2004 is related to the increasing size of the SVP supporter group, which overall increases from around 5% to around 11% in our sample (Note that the sample includes non-voters). After 2005, the share of SVP supporters stays constant. The average right-wing shifts in ideology of the other party supporter groups and the increasingly heterogeneous ideology distribution of SVP support groups explains the decrease in polarisation after 2005.

These results illustrate several interesting dynamics of polarisation in Switzerland. First, public opinion polarisation reaches its peak during the years when Christoph Blocher – the most prominent figure in the transformation of the centre-right SVP into a right-wing populist party – was a government minister (2003–2007). Afterwards, however, voter preferences became less divided, while on the party level Switzerland remained one of the most polarised systems in Europe (Bochsler et al. Citation2015). Second, we see how supporters of the left parties are more polarised and less ideologically cohesive compared to supporters of the right-wing parties. This result is quite contrary to what we know from party elites: Left parties are the most ideologically homogeneous and have the highest party discipline in parliament (Traber Citation2015; Traber et al. Citation2014). Third, in line with research on polarisation in the US, we find that between-party polarisation is most pronounced among voters with tertiary education. However, in a multiparty system the pattern is more nuanced. Finally, our findings highlight an important feature of our concept of polarisation as ideological overlap. When groups become less cohesive internally, polarisation is reduced, even if the average ideological distance between two groups remains the same.

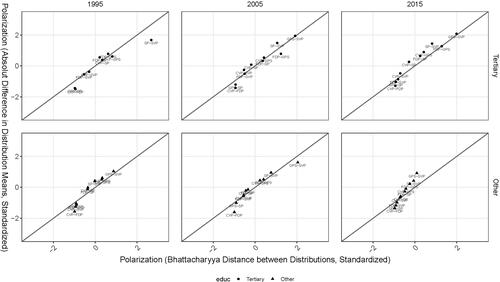

Comparison to alternative polarisation measures

In order to put these results into context, we compare our measure of group-based public opinion polarisation to an alternative measure that only considers the mean group differences. We calculate the absolute difference between the group means in our hierarchical item response model instead of the Bhattacharyya distance. The correlation between the two measures overall is around 0.9 but can generate a subtle difference in our understanding of polarisation between groups. shows the scatter plot of the two measures in 1995, 2005 and 2015. To make the two measures comparable, we standardise the measures and draw the 45-degree equivalence line in the plot. While the measures more or less follow the equivalence line, we observe some systematic deviations. The deviations are most pronounced for comparisons between lower education groups in 2015, where the mean polarisation measures estimate a higher extend of polarisation, in particular between the left parties (GPS and SP) and the SVP. The difference can be attributed to the increased ideological spread among SVP and GPS lower educated groups (see Online Appendix B.4). In the last couple of years of our study, the ideological distribution of the SVP partisan base has widened considerably, resulting in larger distributional overlaps and less distance to other groups. A similar pattern exists for the tertiary-educated groups in 2015, where for example the mean difference between the SP–SVP and CVP–GPS is slightly larger than the distributional distance.

Figure 4. Comparison of polarisation measures, Switzerland 1995, 2005 and 2015 for partisan and education groups.

Using the mean differences on the group level also results in a different description on the aggregated level (see Online Appendix B.7). While the measure based on distributional distance shows relatively stable and low polarisation levels from 2010 to 2015, the measure based on the difference in means sees higher polarisation levels for this period. The increase since 2015 is also more pronounced when using the mean differences. Overall, the choice of group-based polarisation can make a small and subtle difference in the description of polarisation dynamics, in particular when the ideological cohesion of relevant groups strongly changes over time.

Conclusion

Public opinion polarisation is of central concern to political scientists and the general public. Did polarisation increase in European publics in recent years? The answer, partially, depends on the measurement method we apply to address this question. In this article, we propose a group-based public opinion polarisation measurement that relies on one central idea: Polarisation is particularly challenging when it coincides with clearly identifiable social groups. We propose a conceptualisation of polarisation as the ideological divergence between different groups in a society. We outline hierarchical item response models and the usage of a distance measure between distributions to evaluate the extent of polarisation between social groups over time.

Focussing on party supporters and education groups, our application to public opinion data in Switzerland from 1993 to 2016 reveals insightful patterns. While the Swiss party system is highly polarised (Bochsler et al. Citation2015), we find an overall slightly decreasing polarisation between right-wing voters and supporters of the other parties. With our measure, we can show that this is partly due to the fact that supporters of left parties and the SVP have become less ideologically homogeneous and that the major increase in polarisation from 1995 to 2005 aligns with the increase in SVP supporters.

We showcase our approach with an additional application to Germany from 1990 to 2014 in Online Appendix C. The findings underline existing descriptions of public opinion depolarisation in Germany during this time period (Munzert and Bauer Citation2013). The additional application shows that while our method provides similar results on the aggregate, it can provide a more nuanced portrayal of the group dynamics that can generate public opinion polarisation.

Our conceptualisation of group-based public opinion polarisation unites research on cleavage theory and public opinion. Beyond the mere description of public opinion polarisation and cleavage structures in European politics, we are convinced that the conceptualisation can prove useful to evaluate its consequences. We expect that especially ideological cohesiveness of a group can matter in this regard. Ideologically cohesive groups are easier to mobilise by political actors (see e.g. DiMaggio et al. Citation1996; McGann Citation2002), and parties might find it easier to formulate clear policy programs for their ideologically cohesive followers (Nyhuis and Stoetzer Citation2021).

Our conceptualisation and measurement strategy can be applied to more countries and different groups. In our application we rely on education groups and party supporters to reflect the current focus of the cleavage and public opinion theory. Further research could integrate different groups of interest. More specific research calls for other group definitions, such as classes (Evans and Tilley Citation2017; Oesch and Rennwald Citation2010), distribution of income (Lim and Tanaka Citation2022), gender (Knutsen Citation2001), regional divides (Barrio et al. Citation2018) or generational divides.

The measurement model can be extended to take into account higher dimensions of the latent ideological space. In fact, much of the cleavage theory argues that political conflict in Europe is two-dimensional (e.g. Bornschier Citation2010; Kriesi et al. Citation2008, Citation2012). While our focus is on an overall summary of political conflict in terms of a general left–right ideology dimension, dividing the ideological dimensions might result in a more detailed picture of public opinion polarisation. This can be achieved by either estimating a multiple dimensional hierarchical IRT model (Sheng and Wikle Citation2008), or dividing the issues into different issue areas (Zhou Citation2019).

While our approach provides a description of polarisation between groups, it remains agnostic about the theoretical mechanisms that drive polarisation. We discussed shifts and sorting as two important mechanisms. It is not possible to separate both mechanisms with the data used in this article. Further studies could employ panel data to decompose the overall polarisation between groups into (1) shifts in ideology of group members and (2) changes in the composition of a group.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (743.8 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Macarena Ares, Fabio Ellger, the special issue editors Arndt Leininger, Swen Hutter, and Endre Borbáth and the anonymous reviewers for valuable suggestions and comments on the article. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at SVPW general conference 2020 and the FU-WZB Workshop ‘Under pressure: Electoral and non-electoral participation in polarising times’ 2020.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Denise Traber

Denise Traber is an Assistant Professor of Political Sociology at the University of Basel. Her research focuses on party competition, political behaviour and representation in the context of societal and economic changes. [[email protected]]

Lukas F. Stoetzer

Lukas F. Stoetzer is a Senior Lecturer and Researcher at the Humboldt University of Berlin. His research focuses on the comparative study of political behaviour, coalition politics, public opinion and political methodology. [[email protected]]

Tanja Burri

Tanja Burri is a quantitative analyst at the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority.

Notes

1 In contrast to traditional research on party systems, which has been more interested in polarisation as a specific characteristic of a specific party system at a certain point in time (Sartori Citation2005).

2 This is especially true for studies of ideological polarisation. A number of studies have recently suggested measures for affective polarisation in multiparty contexts (Boxell et al. Citation2020; Gidron et al. Citation2020; Reiljan Citation2020; Wagner Citation2021; Harteveld and Wagner Citation2022).

3 It is important to note that in this application we cannot distinguish between the two mechanisms. The distance measure and aggregation procedure we suggest in this article is agnostic about group composition. Thus, it is possible that polarisation increases due to individual shifts in ideology or due to individuals sorting into specific groups. We discuss this important distinction in the concluding section and make some suggestions how future research could address the distinction between polarisation due to ideological shifts and group sorting.

4 A few earlier studies have included separate additional properties, such as the skewness or kurtosis (DiMaggio et al. Citation1996), which provide additional information on the shape of preference distributions.

5 The method is similar to recently proposed group-based IRT models that also have been employed to study ideology in Europe (Caughey and Warshaw Citation2015). For our purpose the maximum-Likelihood estimation proposed by Zhou (Citation2019) is more time-efficient. The IRT model requires a set of identification assumptions for the latent scale. We restrict the discrimination parameter of the first item to be positive to identify the direction of the scale. For mean and variance, we constrain the overall mean of the latent scale to zero and the geometric mean of prior variance to one.

6 To achieve even higher degrees of flexibility, researchers could estimate the group ideology means and variance for each point in time using time dummy variables. In applications, this could be problematic if the composition of items in the survey changes over time, as strong changes in means and variance could be due to the composition of items.

7 The normality of the group ideology distributions is an assumption of the hierarchical IRT model. In case that of other measurement strategies that do not lead to the usages of normal distributions, researchers can approximate the Bhattacharyya distance using histograms. We discuss this in more detail in Online Appendix A.3.

8 In addition to education, income, occupation and social status are relevant characteristics in research on social cleavages. Measures of individual income from surveys can be problematic because they tend to suffer from downward bias. While our approach can be extended to measures of social status, we decided to focus on education for practical reasons. Education levels can be difficult to compare between different countries, but provide a straightforward measure when we compare tertiary vs. non-tertiary educated individuals.

9 We classify respondents with ‘Höhere Fachschule’ and ‘Universität, Hochschule’ as tertiary education groups. ‘Obligatorische Schule’, ‘Lehre’, ‘Maturitätsschule + Primarlehrerausbildung’, and ‘höhere Fach- und Berufsausbildung’ are part of the other group.

10 Literal question: ‘Welche heute im National- oder Ständerat vertretene Partei entspricht in den Zielen und Forderungen am ehesten Ihren eigenen Ansichten und Wünschen?’

11 For a description of group sizes in our study please refer to Online Appendix B.2.

12 In the online appendix we present the results regarding polarisation within party supporter groups, and polarisation between all party supporter groups (Online Appendices B.4–B.6).

References

- Adams, James, Catherine E. De Vries, and Debra Leiter (2012). ‘Subconstituency Reactions to Elite Depolarization in The Netherlands: An Analysis of the Dutch Public’s Policy Beliefs and Partisan Loyalties, 1986–98’, British Journal of Political Science, 42:1, 81–105.

- Adams, James, Jane Green, and Caitlin Milazzo (2012a). ‘Has the British Public Depolarized along with Political Elites? An American Perspective on British Public Opinion’, Comparative Political Studies, 45:4, 507–30.

- Adams, James, Jane Green, and Caitlin Milazzo (2012b). ‘Who Moves? Elite and Mass-Level Depolarization in Britain, 1987–2001’, Electoral Studies, 31:4, 643–55.

- Baldassarri, Delia, and Barum Park (2020). ‘Was There a Culture War? Partisan Polarization and Secular Trends in US Public Opinion’, The Journal of Politics, 82:3, 809–27.

- Barrio, Astrid, Oscar Barberà, and Juan Rodríguez-Teruel (2018). ‘“Spain Steals from Us!” The “Populist Drift” of Catalan Regionalism’, Comparative European Politics, 16:6, 993–1011.

- Bartolini, Stefano, and Peter Mair (2007). Identity, Competition and Electoral Availability: The Stabilisation of European Electorates 1885–1985. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Bhattacharyya, Anil (1946). ‘On a Measure of Divergence between Two Multinomial Populations’, Sankhy¯a: The Indian Journal of Statistics, 7:4, 401–6.

- Bischof, Daniel, and Markus Wagner (2019). ‘Do Voters Polarize When Radical Parties Enter Parliament?’, American Journal of Political Science, 63:4, 888–904.

- Bochsler, Daniel, Regula Hänggli, and Silja Häusermann (2015). ‘Introduction: Consensus Lost? Disenchanted Democracy in Switzerland’, Swiss Political Science Review, 21:4, 475–90.

- Borbáth, Endre, Swen Hutter, and Arndt Leininger (2022). ‘Introduction: Polarisation and Participation in Western Europe’, West European Politics.

- Bornschier, Simon (2010). ‘The New Cultural Divide and the Two-Dimensional Political Space in Western Europe’, West European Politics, 33:3, 419–44.

- Bornschier, Simon, Silja Häusermann, Delia Zollinger, and Céline Colombo (2021). ‘How ‘Us’ and ‘Them’ Relates to Voting Behavior – Social Structure, Social Identities, and Electoral Choice’, Comparative Political Studies, 54:12, 2087–122.

- Boxell, Levi, Matthew Gentzkow, and Jesse Shapiro (2020). ‘Cross-Country Trends in Affective Polarization’, Working Paper 26669, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

- Brooks, Clem, and Jeff Manza (2013). ‘A Broken Public? Americans’ Responses to the Great Recession’, American Sociological Review, 78:5, 727–48.

- Caughey, Devin, and Christopher Warshaw (2015). ‘Dynamic Estimation of Latent Opinion Using a Hierarchical Group-Level IRT Model’, Political Analysis, 23:2, 197–211.

- Cohen, Gidon, and Sarah Cohen (2021). ‘Depolarization, Repolarization and Redistributive Ideological Change in Britain, 1983–2016’, British Journal of Political Science, 51:3, 1181–202.

- De Vries, Catherine E. (2018). ‘The Cosmopolitan-Parochial Divide: Changing Patterns of Party and Electoral Competition in The Netherlands and Beyond’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:11, 1541–65.

- DellaPosta, Daniel, Yongren Shi, and Michael Macy (2015). (1473). ‘Why Do Liberals Drink Lattes?’, American Journal of Sociology, 120:5, 1473–511.

- DiMaggio, Paul, John Evans, and Bethany Bryson (1996). ‘Have American’s Social Attitudes Become More Polarized?’, American Journal of Sociology, 102:3, 690–755.

- Down, Ian, and Carole J. Wilson (2008). ‘From ‘Permissive Consensus’ to ‘Constraining Dissensus’: A Polarizing Union?’, Acta Politica, 43:1, 26–49.

- Esteban, Joan, and Gerald Schneider (2008). ‘Polarization and Conflict: Theoretical and Empirical Issues’, Journal of Peace Research, 45:2, 131–41.

- Esteban, Joan-Maria, and Debraj Ray (1994). ‘On the Measurement of Polarization’, Econometrica, 62:4, 819–51.

- Evans, Geoffrey, and James Tilley (2017). The New Politics of Class in Britain: The Political Exclusion of the British Working Class. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fiorina, Morris P., and Matthew S. Levendusky (2006). ‘Disconnected: The Political Class versus the People’, in Pietro S. Nivola and David W. Brady (eds.), Red and Blue Nation? Characteristics and Causes of America’s Polarized Politics. Washington, DC: Brookings, 49–71.

- Fiorina, Morris P., and Samuel J. Abrams (2008). ‘Political Polarization in the American Public’, Annual Review of Political Science, 11:1, 563–88.

- Gidron, Noam, James Adams, and Will Horne (2020). American Affective Polarization in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harteveld, Eelco, and Markus Wagner (2022). ‘Does Affective Polarisation Increase Turnout? Evidence from Germany, 1990’, West European Politics. doi:10.1080/01402382.2022.2087395

- Hetherington, Marc J. (2009). ‘Review Article: Putting Polarization in Perspective’, British Journal of Political Science, 39:2, 413–48.

- Hobolt, Sara B., Thomas J. Leeper, and James Tilley (2021). ‘Divided by the Vote: Affective Polarization in the Wake of the Brexit Referendum’, British Journal of Political Science, 51:4, 1476–93.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks (2018). ‘Cleavage Theory Meets Europe’s Crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the Transnational Cleavage’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:1, 109–35.

- Hutter, Swen, and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. (2019). European Party Politics in Times of Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Inglehart, Ronald (1977). The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Iyengar, Shanto, Gaurav Sood, and Yphtach Lelkes (2012). ‘Affect, Not Ideology: A Social Identity Perspective on Polarization’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 76:3, 405–31.

- Iyengar, Shanto, Yphtach Lelkes, Matthew Levendusky, Neil Malhotra, and Sean J. Westwood (2019). ‘The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States’, Annual Review of Political Science, 22:1, 129–46.

- Jost, John T. (2006). ‘The End of the End of Ideology’, The American Psychologist, 61:7, 651–70.

- Kitschelt, Herbert (1994). The Transformation of European Social Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Knutsen, Oddbjørn (2001). ‘Social Class, Sector Employment, and Gender as Party Cleavages in the Scandinavian Countries: A Comparative Longitudinal Study, 1970–95’, Scandinavian Political Studies, 24:4, 311–50.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter (1998). ‘The Transformation of Cleavage Politics: The 1997 Stein Rokkan Lecture’, European Journal of Political Research, 33:2, 165–85.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter (2008). Direct Democratic Choice: The Swiss Experience. Lanham: Lexington Books.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Martin Dolezal, Marc Helbling, Dominic Hoglinger, Swen Hutter, and Bruno Wuest (2012). Political Conflict in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey (2006). ‘Globalization and the Transformation of the National Political Space: Six European Countries Compared’, European Journal of Political Research, 45:6, 921–56.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey (2008). West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Matthias Brunner, and François Lorétan (2017). ‘Standardisierte Umfragen VoxIt 1981–2016’, available at https://forsbase.unil.ch/datasets/dataset-public-detail/15357/1281/ (accessed 26 February 2018).

- Lancaster, Caroline Marie (2022). ‘Value Shift: Immigration Attitudes and the Sociocultural Divide’, British Journal of Political Science, 52:1, 1–20.

- Layman, Geoffrey C., Thomas M. Carsey, and Juliana Menasce Horowitz (2006). ‘Party Polarization in American Politics: Characteristics, Causes, and Consequences’, Annual Review of Political Science, 9:1, 83–110.

- Lim, Sijeong, and Seiki Tanaka (2022). ‘The Paradoxical Effect of Welfare Knowledge: Unveiling Income Cleavage over Attitudes to Welfare in South Korea’, International Political Science Review, 43:1, 67–84.

- Lipset, Seymour Martin, and Stein Rokkan (1967). Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York: Free Press.

- Mason, Lilliana (2018). Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- McGann, Anthony J. (2002). ‘The Advantages of Ideological Cohesion: A Model of Constituency Representation and Electoral Competition in Multi-Party Democracies’, Journal of Theoretical Politics, 14:1, 37–70.

- Milazzo, Caitlin, James Adams, and Jane Green (2012). ‘Are Voter Decision Rules Endogenous to Parties’ Policy Strategies? A Model with Applications to Elite Depolarization in Post-Thatcher Britain’, The Journal of Politics, 74:1, 262–76.

- Munzert, Simon, and Paul C. Bauer (2013). ‘Political Depolarization in German Public Opinion, 1980–2010’, Political Science Research and Methods, 1:1, 67–89.

- Mutz, Diana C., and Jahnavi S. Rao (2018). ‘The Real Reason Liberals Drink Lattes’, PS: Political Science & Politics, 51:4, 762–7.

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart (2019). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nyhuis, Dominic, and Lukas F. Stoetzer (2021). ‘The Two Faces of Party Ambiguity: A Comprehensive Model of Ambiguous Party Position Perceptions’, British Journal of Political Science, 51:4, 1421–38.

- Oesch, Daniel (2008). ‘Explaining Workers’ Support for Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe: Evidence from Austria, Belgium, France, Norway, and Switzerland’, International Political Science Review, 29:3, 349–73.

- Oesch, Daniel, and Line Rennwald (2010). ‘The Class Basis of Switzerland’s Cleavage between the New Left and the Populist Right’, Swiss Political Science Review, 16:3, 343–71.

- Oesch, Daniel, and Line Rennwald (2018). ‘Electoral Competition in Europe’s New Tripolar Political Space: Class Voting for the Left, Centre-Right and Radical Right’, European Journal of Political Research, 57:4, 783–807.

- Poole, Keith T., and Howard Rosenthal (1984). ‘The Polarization of American Politics’, The Journal of Politics, 46:4, 1061–79.

- Reiljan, Andres (2020). ‘“Fear and Loathing across Party Lines” (Also) in Europe: Affective Polarisation in European Party Systems’, European Journal of Political Research, 59:2, 376–96.

- Sartori, Giovanni (2005). Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis. Colchester: ECPR.

- Schattschneider, Elmer Eric (1960). The Semisovereign People. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Sheng, Yanyan, and Christopher K. Wikle (2008). ‘Bayesian Multidimensional IRT Models with a Hierarchical Structure’, Educational and Psychological Measurement, 68:3, 413–30.

- Silva, Bruno Castanho (2018). ‘Populist Radical Right Parties and Mass Polarization in The Netherlands’, European Political Science Review, 10:2, 219–44.

- Traber, Denise (2015). ‘Disenchanted Swiss Parliament Electoral Strategies and Coalition Formation’, Swiss Political Science Review, 21:4, 702–23.

- Traber, Denise, Simon Hug, and Pascal Sciarini (2014). ‘Party Unity in the Swiss Parliament: The Electoral Connection’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 20:2, 193–215.

- Treier, Shawn, and D. Sunshine Hillygus (2009). ‘The Nature of Political Ideology in the Contemporary Electorate’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 73:4, 679–703.

- Wagner, Markus (2021). ‘Affective Polarization in Multiparty Systems’, Electoral Studies, 69, 102199.

- Wagner, Markus, and Thomas M. Meyer (2014). ‘Which Issues Do Parties Emphasise? Salience Strategies and Party Organisation in Multiparty Systems’, West European Politics, 37:5, 1019–45.

- Walter, Stefanie (2021). ‘The Backlash against Globalization’, Annual Review of Political Science, 24:1, 421–42.

- Zhou, Xiang (2019). ‘Hierarchical Item Response Models for Analyzing Public Opinion’, Political Analysis, 27:4, 481–502.