Abstract

Since the Eurozone crisis, intense political debate has resurfaced about deservingness judgements in European solidarity. To contribute to this debate, this article proposes a refined concept of ‘multi-level blame attribution’. It postulates that public support for EU-level welfare policies crucially depends on how citizens attribute responsibility for economic outcomes across different levels of agency. Results from an original public opinion survey conducted in 10 European Union member states demonstrate that attributing blame to individuals decreases citizens’ willingness to show solidarity with needy Europeans, whereas attributing blame to the EU increases support. The role of attributing blame to national governments is dependent on the country context; beliefs that worse economic outcomes are caused by national governments’ policy decisions tend to dampen support for EU targeted welfare policies only in the Nordic welfare states. The article concludes by discussing the implications of multi-level blame attribution for the formation of public attitudes towards European solidarity.

The European integration project was built on the assumption that economic growth would increase social cohesion and reduce poverty, nevertheless, large socioeconomic inequalities remain present in Europe. More than 91 million Europeans currently live at risk of poverty or social exclusion, with poverty rates varying considerably across member states (Eurostat Citation2021a). Against this background, the European Union (EU) has expressed its ambition to strengthen the social dimension of the European project through the proclamation of the European Pillar of Social Rights (EPSR), which aims to deliver new and more effective rights for citizens (European Commission Citation2017a). To achieve this aim, diverse EU-level welfare policies targeted at vulnerable groups are being discussed. For example, a European framework on minimum incomes has been proposed, to ensure that people lacking sufficient resources have the right to adequate minimum income benefits (European Parliament Citation2017; Peña-Casas and Bouget Citation2014). In a similar vein, proposals for establishing a European Unemployment Benefit Re-insurance Scheme aim to ensure a guaranteed minimum level of unemployment benefits (Dullien Citation2013; European Commission Citation2017b) and the debated European Child Guarantee aims to ensure that every child in poverty can have access to healthcare, education, childcare, decent housing and adequate nutrition (European Commission Citation2021; European Parliament Citation2015). Each of these EU policy proposals aims to strengthen the social rights of vulnerable groups – notably the poor, the unemployed and disadvantaged children – and they constitute incremental steps towards a more ‘Social Europe’ (Vandenbroucke et al. Citation2017).

Are Europeans, however, willing to show solidarity with needy groups at an EU-wide level? And why or why not? While a coordinated European strategy in the fight against poverty and social exclusion has received extensive scholarly attention, only a few studies have examined how citizens perceive the development of EU-level social policies, in particular policies targeted towards vulnerable groups (Baute and Meuleman Citation2020; Burgoon Citation2009; Gerhards et al. Citation2019; Kuhn et al. Citation2020). Nevertheless, the development of a ‘Social Europe’ is a highly contested aspect of European integration, since it redraws the boundaries of welfare that have traditionally been defined by national welfare states (Ferrera Citation2005; Leibfried and Pierson Citation1995). In this article, we argue that Europeans’ willingness to support fellow citizens in need crucially depends on how they attribute responsibility for economic outcomes.

The notion of blame attribution for economic outcomes nonetheless remains poorly conceptualised in current literature. More specifically, existing studies into welfare attitudes and blame attribution in multi-level systems deal with this concept in a fragmented and overly-simplistic way. Previous research that focusses on lay explanations for poverty distinguishes individual blame (that is, the belief that poverty results from the behaviour of individuals themselves) from social blame (the belief that poverty results from the actions of certain actors in society) (Kallio and Niemelä Citation2014; van Oorschot and Halman Citation2000). This distinction between individual and social agency falls short with regard to grasping fully how citizens attribute responsibility for economic outcomes in Europe. In the current multi-level governance system of the EU, Europeans may attribute responsibility for economic outcomes to national as well as supranational institutions (Baglioni and Hurrelmann Citation2016; Bellucci Citation2014; Guinjoan and Bermúdez Citation2020; Heinkelmann-Wild et al. Citation2018; Hobolt and Tilley Citation2014a) that increasingly influence their life chances. The idea that national and EU policy decisions are to blame for economic misfortune found strong resonance during the Eurozone crisis (Fourcade et al. Citation2013; Matthijs and McNamara Citation2015; Teperoglou et al. Citation2014). In this context, the most crisis-stricken member states were criticised for having mismanaged their economy and public finances, while the EU austerity measures have been accused of worsening the situation in these member states, where the welfare state was comparatively weak even before the crisis (de la Porte and Heins Citation2016). However, individuals are nested within nation states, which are in turn nested within the European Union. Therefore, current research does not account for how Europeans simultaneously attribute responsibility for economic outcomes across multiple, nested levels of agency (that is, individual, national and supranational) and how this affects solidarity with fellow Europeans in need.

In order to fill this gap in literature, the current study develops an integrated theoretical framework of multi-level blame attribution – that is, the joint attribution of individual, national and supranational blame for economic outcomes – and investigates how the attribution of blame at these three nested levels simultaneously shapes support for EU-level welfare policies targeted at vulnerable groups. By focussing on EU-level policies targeted at the poor, the unemployed and disadvantaged children, we cover the most prominent groups which are being targeted in EU-level welfare policy proposals aiming to reduce inequality (Jessoula and Madama Citation2020). Analysing data from the 2019 REScEU survey (‘Reconciling the Economic and Social Europe’) conducted in 10 EU member states, the study reveals that citizens clearly link cause and solution when it comes to economic inequality in Europe. Attributing blame to individuals dampens support for EU-level welfare policies targeted at vulnerable groups, whereas attributing blame to the EU increases support. We find little evidence of a negative effect if attributing blame to national governments on public support in more generous welfare states. As our integrated theoretical framework of multi-level blame attribution provides an unprecedented fine-grained insight into why people support EU-level targeted welfare policies, we see important implications for future research on European solidarity.

Linking cause and solution: multi-level blame attribution and support for EU welfare policies

Previous research lacks an integrated theoretical framework of blame attribution which takes into account that citizens may simultaneously blame individuals, national governments and the EU for economic outcomes. We propose a refined concept of ‘multi-level blame attribution’ that is innovative in two ways. First, ours is more comprehensive than previous conceptualisations, as we consider the individual, national and EU level of agency as three distinct constitutive components of multi-level blame attribution: (1) the individual agency level captures the extent to which individuals themselves are blamed for their economic misfortune, (2) the national agency level captures the extent to which national governments are blamed for poor economic outcomes, and (3) the EU agency level captures the extent to which the European Union is blamed for poor economic outcomes. Second, we treat the relationship between these three agency levels as nested within one another: individuals function within a national context, which in turn is shaped by supranational decision making. This nested approach implies that blame for economic outcomes can be attributed to each of these three levels of agency simultaneously because of the multitude of relevant economic, decision-making actors and the blurring of responsibility in multi-level governance settings.

Integrating the literature on welfare attitudes and blame attribution in multi-level governance systems, in the next paragraphs we theorise on ways in which the three constitutive levels of our concept of multi-level blame attribution jointly shape support for EU-level welfare policies targeted at vulnerable groups.

Blaming individuals

Why are some people poor? Numerous empirical studies have shown that different lay explanations prevail about why poverty exists in society (Bullock et al. Citation2003; da Costa and Dias Citation2015; Feagin Citation1972; Kallio and Niemelä Citation2014; Lepianka et al. Citation2009; Schneider and Castillo Citation2015). Such explanations have been theoretically structured in a widely-used typology crosscutting two dimensions; an individual–societal dimension, where poverty is seen as the result of individual or social forces, and a blame–fate dimension, where poverty is the result of bad luck or bad decisions (van Oorschot and Halman Citation2000). Individual blame attribution corresponds with the idea that the poor are in control of their own situation and thus are themselves to blame for their predicament; if they only made an effort, they would be able to escape poverty.

Attributing blame to individuals matters for solidarity, because it is closely linked to perceptions of the poor as being undeserving of welfare support (van Oorschot Citation2000). Deservingness theory postulates that support for welfare policies largely depends on a person’s perceptions about the recipients of welfare. One of the deservingness criteria that citizens apply, according to the ‘CARIN criteria’Footnote1 developed by van Oorschot (Citation2000), precisely matches the idea of individual blame, namely the control criterion, according to which people are perceived as being more deserving of welfare support if they have little personal control over their predicament and thus cannot be blamed for it. The deservingness framework allows us to compare the relative importance of the different criteria, putting the individual control criterion into perspective. Empirical studies have consistently found that control is among the most important criteria in explaining support for welfare programmes (Gollust and Lynch Citation2011; Heuer and Zimmermann Citation2020; Reeskens and van der Meer Citation2019). These findings align with scholarly work that directly links social policy preferences to beliefs about the causes of poverty. People who attribute poverty to individual agency are found to be less supportive of minimum income proposals (Hastie Citation2010), of redistribution more generally (Fong Citation2001), and also less likely to vote for left-wing parties that support welfare expansion (Attewell Citation2021). Furthermore, individualistic beliefs about the causes of poverty are associated with stronger preferences for making welfare programmes less generous and more conditional (Bullock et al. Citation2003).

Taken together, these studies show that citizens’ support for welfare policies is affected by whether they attribute poverty to individual agency. The more someone considers needy groups as being personally responsible for their own situation, the less they are likely to support welfare programmes targeted towards these groups. However, to the best of our knowledge, no prior research has investigated how attributing blame to individuals affects support for EU-level instead of national-welfare policies. We hypothesise that the deservingness criterion of control transcends national boundaries and thus those who more strongly attribute blame to individuals will be less willing to share risks and resources with fellow Europeans in need. Hence, our first hypothesis:

H1: Individuals who believe that poverty is caused by circumstances within the control of the individual are less inclined to support EU-level welfare policies targeted at needy groups.

Blaming national governments

Since poverty and unemployment rates diverge greatly across EU member states (Eurostat Citation2021a, Citation2021b), some countries are more likely than others to be recipients of EU-level welfare policies. The existence of cross-national differences, with Southern and Eastern European countries facing worse conditions than Northern European ones, is not an obstacle per se to European solidarity. Instead, we argue that it is how citizens reason about the causes of cross-national differences in economic outcomes that is decisive for their willingness to support EU-wide welfare assistance. Whether national governments are to blame for macroeconomic and social outcomes became a particularly salient and contentious issue during the Eurozone crisis. Two different narratives portrayed by national media and political elites separated the core countries of Northern Europe, with their more affluent economies and generous welfare states, from the Eurozone periphery which struggled with high public debt levels, stagnant economies and increasing poverty rates (Pérez Citation2019). The emergence of different narratives is rooted in divergent economic interests between these two groups of countries, but also in entrenched cultural worldviews as well as stereotypes, reflected by their nicknames: ‘frugal’ countries for the Northerners and ‘PIIGS’Footnote2 for the Southerners (Bulmer Citation2014; Ferrera Citation2017; Matthijs and McNamara Citation2015). Conflicting views on who was to blame for the crisis hindered the adoption of collective responses, strengthening solidarity between EU member states and citizens and contributed to the erosion of the stock of mutual trust that European countries had accumulated since the end of the Second World War (Grabbe Citation2012; Olmastroni and Pellegata Citation2018).

Northern countries tend to blame ‘idle Southerners’ and the fiscal profligacy of their governments, which are unable to adopt structural reforms to make the national labour market and the welfare state more efficient while keeping public debt under control. Accordingly, the fiscal imbalances and poor macroeconomic performance of Southern countries reflect the damaging policy decisions implemented by national political elites in the past. In line with the ‘moral hazard’ logic, since the outbreak of the Eurozone crisis, political leaders of the Northern countries have repeatedly appeared concerned that providing financial help to countries in economic and financial difficulties means that such governments can take advantage of their solidarity, wasting these contributions without helping those in need. Therefore, Southern countries are considered less deserving of help, and it has been argued that the burdens of fiscal adjustment should fall exclusively on national governments and taxpayers. This explains why Northern political leaders have supported a strong conditionality regime for the bailout countries, according to which transfers should be accompanied by precise conditions for repayment and linked to domestic structural reforms. Northern leaders have also strongly opposed any form of mutualisation of public debt across countries through the adoption of Eurobonds (Ferrera Citation2017).

The current literature has discussed the divergent views of the role played by national governments across Europe, with reference to the adoption of financial transfers to countries in severe economic and financial difficulty to help the recovery of their national economy from the consequences of the Eurozone crisis (Fourcade et al. Citation2013; Matthijs and Blyth Citation2015; Matthijs and McNamara Citation2015). In this line of argument, citizens’ willingness to help those in need on an EU-wide scale may strongly depend on the attribution of responsibility to national governments for economic outcomes. The more one attributes prevailing cross-national differences in economic outcomes to national policy decisions, the less likely one is to be in favour of sharing risks and resources at an EU-wide level. However, we expect the effect of national blame to be moderated by the national context. Especially in the core countries – characterised by more generous welfare states that withstood the crisis better – attributing blame for economic outcomes to national governments is likely to be detrimental to European solidarity. In these contexts, citizens can already depend on a more generous social safety net and could therefore give more weight to the criterion of control in order to support international redistribution. Hence, those who blame weaker member states for poor economic conditions will consider these states as less deserving of international aid. By contrast, in less generous welfare states attributing blame to the national level for poor economic outcomes may be less detrimental for EU-wide solidarity targeted at the needy, since these countries are more likely to become net recipients of EU-level measures to tackle economic hardship. Moreover, in such contexts, citizens may embrace EU-level governance more readily if national governments are blamed for the problems. In this regard, previous studies have shown that citizens in less generous welfare states are more supportive of EU-level welfare policies (Baute and Meuleman Citation2020; Burgoon Citation2009; Mau Citation2005). Therefore, we postulate that the prospect of one’s own country becoming a beneficiary of EU-level welfare assistance may counterbalance the negative effect of national blame.

While a large number of empirical studies have analysed support for financial assistance between member states (Bechtel et al. Citation2014; Daniele and Geys Citation2015; Gerhards et al. Citation2019; Vasilopoulou and Talving Citation2020), these studies have overlooked the role of national blame considerations in influencing support for European solidarity. There are, however, three studies that are exceptions in this regard and suggest that the attribution of national blame is an important element for European solidarity, not least in the creditor states. First, drawing on data from electoral candidate surveys in nine EU member states, Reinl and Giebler (Citation2021) demonstrated that political elites tend to be somewhat less supportive of transnational solidarity if they believe that the recipient states themselves are responsible for their precarious situation. Second, Koos and Leuffen (Citation2020), using a vignette experiment among German respondents, found that the willingness to provide help to other countries during the COVID-19 crisis is lower if the recipient country has taken damaging institutional actions in the past. The authors suggested that this may result from feelings of resentment persisting in the North since the sovereign debt crisis. Lastly, an eight-country study by Lahusen and Grasso (Citation2018) showed that Europeans in Northern and Western welfare states are more sensitive towards national responsibility compared with Southern Europeans. The former more often think that financial help should not be given to countries that have been proven to handle money badly. Based on these findings and taking into account the divergent self-interests across European countries, we formulate a two-fold hypothesis:

H2a: Individuals who believe that worse economic outcomes are caused by national governments’ policy decisions are less inclined to support EU-level welfare policies targeted at needy groups.

H2b: The negative association between blaming national governments and supporting EU-level welfare policies targeted at needy groups is stronger in generous welfare states.

Blaming the EU

Over recent decades, we have witnessed a gradual shift towards increasing EU decision making which also covers social policy areas (Ferrera Citation2005; Leibfried and Pierson Citation1995). This has contributed to exacerbating the conflict between the so-called winners and losers of European integration (Kriesi et al. Citation2008). In the realisation that policies have become Europeanised, citizens – especially those who feel threatened by the integration process – may increasingly blame Europe for undesired outcomes (Beaudonnet Citation2015; Kumlin Citation2009). In this regard, Hobolt and Tilley (Citation2014a: 4) argue that since EU institutions increasingly hold the same policy levers as national governments, we should expect the EU to shoulder more of the blame when things go wrong. Recent studies show that citizens not only hold national governments accountable, but also attribute responsibility to the EU for various policy outcomes, including economic conditions, health care and social welfare in their country (Devine Citation2021; Goldberg et al. Citation2022; Hobolt and Tilley Citation2014b; León et al. Citation2018; Wilson and Hobolt Citation2015). Furthermore, EU citizens have expressed concerns that European integration may pose a threat to domestic labour markets and social protection systems (Baute et al. Citation2018; Grauel et al. Citation2013).

The belief that the EU is responsible for social-economic outcomes found strong resonance during the Eurozone crisis (Baglioni and Hurrelmann Citation2016; Bellucci Citation2014). During this period, the effects of the European Monetary Union (EMU) in terms of EU fiscal and monetary policy, as well as public finances more generally, have become highly visible (Mourlon-Druol Citation2014). The EU has forced national governments – in particular the bailout countries – to implement stringent austerity measures and structural reforms in an attempt to restore financial stability. Consequently, countries that received EU bailouts have been more constrained in steering national policies, as they were subject to much greater scrutiny from supranational institutions (Okolikj and Quinlan Citation2016). In this particular crisis context, European populations have witnessed limited room for manoeuvre by national governments (Devine Citation2021).

In Greece, Italy and Spain, for instance, most of the media, parties and public opinion shifted the blame for the poor macroeconomic performance of the national economy and the worsened social conditions to EU institutions and the more affluent member states (Conti et al. Citation2020; Teperoglou et al. Citation2014). Indeed, the role of the EU institutions was often lumped together with the responsibility of core member states and their leaders, Germany and Angela Merkel in primis, for pursuing the financial stability of the Eurozone almost exclusively, even to the detriment of economic growth and social cohesion; an economic governance that strongly penalises debt-ridden member states (Blyth Citation2013; Bulmer Citation2014; Ferrera Citation2017). Therefore, southern European countries have argued against austerity measures, calling for more flexibility in the application of rules, the mobilisation of EU resources for investment and growth, and most importantly, the mutualisation of risks. Public demonstrations have been held in several member states, precisely revolving around the looming negative consequences of EU fiscal policies for national social protection levels. For instance, Greek citizens took to the streets to protest against the reform policies that threatened pensions and unemployment benefits (Rüdig and Karyotis Citation2014).

We argue that multi-level governance and the blurring of responsibility between the national and European institutions have implications for citizens’ deservingness judgements and EU agenda preferences. If the EU is perceived as the cause of the malaise – that is, social economic problems such as poverty, unemployment and economic decline – people may expect the EU to take responsibility by remediating economic suffering, in particular for the most vulnerable. We thus expect that the more one attributes blame for economic outcomes to the EU, the more one will embrace EU-level welfare policies targeted at vulnerable groups, as a way of compensating those groups for the negative consequences of the EU-induced (austerity) policies. This compensation hypothesis implies that the EU should not only compensate the losers of globalisation – which it currently does by means of the EU structural funds (Schraff Citation2019) – but also compensate for the negative side-effects of its own policies. Although attributing blame to the EU might relate to a more negative image of the EU and a lower trust in its institutions (we explore this contingency in materials in the online appendix, supplementary materials, discussed below), we expect it to increase the demand for EU-level welfare assistance, since such policies are precisely aimed at remediating the living conditions of the most precarious groups. According to this compensation logic, blaming the EU for having worsened economic and social conditions in the member states by means of its austerity policies may not be associated with a request for more EU competences as such, but should instead foster a stronger demand for EU policy initiatives that have an explicit social purpose and raise the profile of the EU as a provider of, instead of a threat to, social protection. Hence, our third hypothesis:

H3: Individuals who believe that worse economic outcomes are caused by EU policies are more inclined to support EU-level welfare policies targeted at needy groups.

Data and methods

Data

In order to test our hypotheses, we draw on data from the 2019 REScEU survey (Donati et al. Citation2021) which was fielded in 10 EU member states: Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain and Sweden. The selected countries vary with regard to welfare state regimes, macro-economic conditions and Eurozone membership. The survey was administered online (CAWI methodology) by IPSOS between 28 June and 2 August 2019, using national samples of adult respondents stratified by gender, age, education level and region of residence (NUTS-1 level). The total sample includes 15,149 respondents (see online appendix Table A for country sample sizes).

Variables

The dependent variable, support for EU targeted welfare assistance to vulnerable groups, is measured by the following question:

To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements about whether the EU should help citizens in need in every European member state:

The EU should provide financial help to all poor people…

The EU should provide financial help to all the unemployed…

The EU should provide financial help to all disadvantaged children…

even if this means that all member states, including (COUNTRY), would have to pay more money to the EU.

Multi-level blame attribution is measured by means of three separate items. First, to measure attribution of blame to individuals, we rely on a standard item asking respondents why there are people living in poverty (Lepianka et al. Citation2009; van Oorschot and Halman Citation2000). The response categories consist of: (1) because they have been unlucky, (2) because of laziness and lack of willpower, (3) because there is much injustice in our society, or (4) because some poverty is an inevitable part of progress. In line with previous research, we operationalise individual blame as ‘laziness and lack of willpower’ (=1) versus the other explanations (=0), as the former clearly refers to a situation where the poor are in control of their neediness (Albrekt Larsen Citation2006; Kallio and Niemelä Citation2014). Second, attribution of blame to national governments is measured by an item tapping into the responsibility of national governments for economic outcomes during the Eurozone crisis (see online appendix Table B for the question wording). Agreement with or opposition to the statement that ‘The weaker member states have mismanaged their economy and public finances’ was recoded into a binary variable (1 = strongly or somewhat agree, 0 = strongly or somewhat disagree). The dataset allows us to perform robustness analyses using an item that captures distrust in other EU member states, which we report in online appendix Tables F–H and Figure B. Third, attribution of blame to the EU is measured by an item that taps into the responsibility of the EU for economic outcomes during the Eurozone crisis: ‘The EU policies of fiscal austerity have worsened the social and economic problems of weaker member states’. Responses were again recoded into a binary variable (1 = strongly or somewhat agree, 0 = strongly or somewhat disagree). We acknowledge that the operationalisation of attributing blame to national governments and the EU captures specific beliefs about the responsibility of national and EU actors that prevailed in the political discourse during the Eurozone crisis, rather than generalised national and EU blame for economic outcomes. Ideally, we would also have generic measurements at our disposal to investigate how national and EU blaming operate outside a crisis context. However, the Eurozone crisis may have awakened national and EU blame attributions among European citizens. Furthermore, in contrast to individual blame, it is much more complex to form an opinion on generalised spatial national and EU levels of blame. The Eurozone crisis can be considered an ideal test case to study the relationship between multi-level blame attribution and European solidarity, since the crisis led to widely diverging social-economic outcomes across EU member states (in terms of unemployment, poverty and growth rates). Furthermore, making a direct reference to the concrete situation of the Eurozone crisis helps respondents to understand where the responsibilities lie between member states and the EU. To capture beliefs about the cause of cross-national differences in economic outcomes during the Eurozone crisis, the statements refer to weaker member states instead of the respondents’ own government in particular. As these two items measure specific sentiments of blame attribution to both national and supranational institutions in relation to economic outcomes that emerged strongly during the Eurozone crisis, we believe that our measurement is well-suited for the purposes of this study. The combination of the three items measuring individual, national and EU blame allows us to study multi-level blame attribution from a nested perspective. Since 15.7 per cent and 20.5 per cent of the total sample gave a ‘don’t know’ response to the statements concerning national and EU blame, respectively, we report descriptive statistics of these respondents (online appendix Table D) and performed robustness checks including a separate category for missing values on these items (online appendix ).

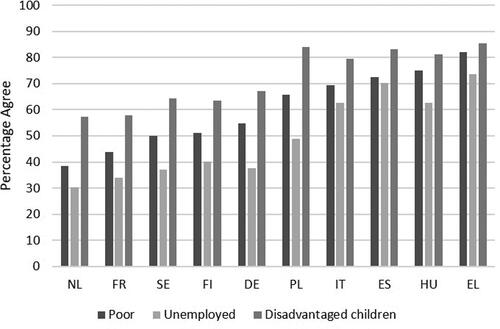

Figure 1. Support for EU targeted welfare policies in percentage by country (weighted).

Source: Authors’ elaboration on REScEU 2019 survey data.

As control variables we include in the regression models a dummy for exclusive national identity, because people without a sense of European identity are less likely to perceive fellow Europeans as part of the in-group and thus as less deserving of welfare assistance. Furthermore, we control for respondents’ level of EU support, as they might oppose EU welfare policies simply because they are Eurosceptic in the first place (0 = European integration has already gone too far, 10 = European integration should be pushed further). Support for redistribution is included by means of a standard item on reducing differences in income levels in the respondent’s country. This question asks whether respondents are fully opposed to state measures to reduce differences in income levels in their country (0), fully in favour of state measures to reduce differences in income levels (10), or somewhere in-between. As a robustness check, we ran the models using left-right self-placement instead of support for redistribution (online appendix Figures J and K). Lastly, we control for a number of social-structural variables, since these have been found to correlate with poverty attributions (da Costa and Dias Citation2015; Fong Citation2001). Education is categorised into lower-secondary or below, upper-secondary and tertiary. Occupational class is measured by four categories: employers and self-employed, salaried middle class, socio-cultural specialists, service and production workers, and separate categories for the unemployed, welfare recipients and other ‘inactive’ people. Subjective household income is included in four categories: living comfortably on the present income, coping on the present income, finding it difficult on the present income and finding it very difficult on the present income. We control for welfare dependence by including a dummy indicating whether or not the respondent or another household member received at least one type of social security benefit, (excluding pensions) during the two years before the survey. Lastly, we include a dummy for respondents living with children in their household and include the respondents’ age (18–34, 35–54 and 55+) and gender (1 = Female, 0 = Male). Descriptive statistics are provided in online appendix Table C.

Methods

In order to test our hypotheses, we estimate a series of logistic regression models. Because the sample contains an insufficient number of level-2 units (N = 10) for multilevel modelling (Stegmueller Citation2013), we include country dummies in the regression models as a best-practice solution to account for cross-national variation in support for EU welfare policies, using the Netherlands as the reference country. We performed two different specifications of the regression models. First, to test H1, H2a and H3, we regress support for EU welfare policies targeted at the poor, the unemployed and disadvantaged children on the multi-level blame attribution and controls. Second, to test H2b, we interact national blame with country dummies. To facilitate the interpretation of the regression coefficients, we standardised all continuous variables (EU support, support for redistribution and left-right placement). Post-stratification weights and robust standard errors are included in all the models. These weights correct for biases in representation according to age, gender, education and region of residence. As a robustness check, we performed OLS regression models, which yielded very similar results (online appendix Figures E and F).

Results

presents the level of support for EU targeted welfare support in each country. Two important observations result from this figure. First, we find a universal rank order when comparing the relative levels of support for EU policies targeted at disadvantaged children, the poor and the unemployed. In all countries, respondents are most willing to show solidarity towards disadvantaged children and least willing towards the unemployed. This pattern aligns with the traditional deservingness literature, showing that groups with a more negative public image – notably the unemployed – are considered as less deserving of welfare support, while poor children are usually viewed as a highly deserving group (van Oorschot Citation2000). The generous support for disadvantaged children could result either from a strong recognition of their vulnerability, as innocent third parties who depend on adult carers, or Europeans may reason that the future return on investment is greatest for policies targeted at younger age groups (Garritzmann et al. Citation2018; Heuer and Zimmermann Citation2020). Second, shows the cross-national variation in the level of support, which is structured by national welfare state generosity. Respondents in Southern and Eastern European countries are clearly more supportive of EU welfare policies than their equivalent in Northern and Western European countries, who enjoy more generous welfare provision at home. Looking at the extremes, we observe that only 38 per cent of the Dutch respondents support policies targeted at the poor, while we find a large majority of 82 per cent in Greece. For a more detailed insight into how support for EU-level policies correlates with national welfare policy, we refer to online appendix Figure A.Footnote3

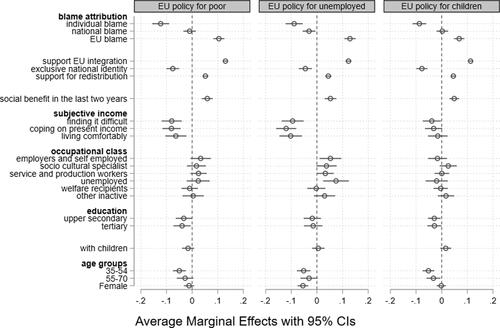

Turning to the regression models, logit coefficients are complex to interpret and could be misleading, given the non-linear nature of logistic regression. To make the findings more straightforward, we plot the average marginal effects of covariates on the probability that individuals support EU-level policies (the full regression tables of the logit models are reported in Model 1 of online appendix Tables F–H). displays the change in the predicted probability of supporting EU-level policies targeted at the poor, the unemployed and disadvantaged children, respectively, at changing levels of individual blame, national blame, EU blame and controls. Positive values, on the right of the dashed vertical line, indicate that higher values of the predictors, or the discrete changes from the reference category, increase the likelihood that a person supports EU-level welfare policies. Negative values, on the left of the vertical line, are associated with a lower predicted probability of supporting these policies.

Figure 2. Average marginal effects of determinants of support for EU-level welfare policies.

Notes: Horizontal lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Source: Authors’ elaboration on REScEU 2019 survey data.

shows that, in line with H1, respondents who blame the poor themselves for their economic conditions are significantly less likely to support EU-level welfare programmes to help needy Europeans, compared with their counterparts who do not attribute direct responsibility to the individual. The probability of supporting EU-level policies targeted at the poor is 12 percentage points lower among those who blame the poor for their situation. The results are similar for EU-level policies targeted at the unemployed and at disadvantaged children (both 9 percentage points lower among those who blame the poor).

Furthermore, illustrates that attributing blame to national governments does not reduce support for EU-level policies targeted at the poor or at disadvantaged children, while it slightly reduces support targeted at the unemployed (by 3 percentage points; p<.05). However, excluding one country at a time from the pooled dataset, we observe that this effect is exclusively driven by Finland and Sweden. Overall, H2a is thus not corroborated.

By contrast, indicates that blaming the EU fiscal austerity policies for the worsening economic and social conditions of people living in weaker member states is associated with a higher likelihood of supporting EU-level welfare policies, corroborating H3. Blaming the EU increases the predicted probability of supporting EU welfare policies by 10 percentage points for policies targeted at the poor, by 13 percentage points for those targeted at the unemployed and by 7 percentage points for policies targeted at disadvantaged children. It should be noted that the effect of blaming the EU may be partly driven by anti-austerity sentiments, as respondents’ general attitude towards austerity measures is not taken into account in the analysis. However, to provide further empirical evidence in support of H3, we have interacted the variable measuring EU blame with support for EU integration and European/national identity, respectively. Marginal effects plotted in online appendix Figures C and D show that the positive relationship between EU blame and support for EU welfare policies holds for citizens across the entire spectrum of pro- versus anti-EU attitudes, indicating that individuals with Eurosceptic attitudes are also more inclined to support EU welfare policies if they blame the EU. Interestingly, while blaming the EU thus relates to stronger demand for EU-level welfare policy, we observe a negative relation with EU support and trust in EU institutions (online appendix Table E), suggesting that EU blame attribution turns people in favour of a different kind of Europe (i.e. more Social Europe) rather than more Europe as such.

Additional analyses confirm that the results for individual, national and EU blame are robust across different model specifications (online appendix Figures E-F) and by country (online appendix Figures G–HFootnote4). We also report the results of the models including a separate category for missing values on the survey items on national and EU blame in online appendix . Respondents indicating ‘don’t know’ do not differ significantly from the reference group (i.e. those who do not attribute blame nationally or to the EU) in their support for EU-level social policies.

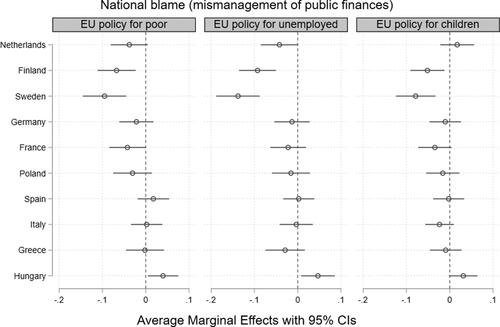

To gain insight into the conditional role of attributing blame to national governments (H2b), plots the average marginal effects of national blame – that is, beliefs of mismanagement by weaker countries – on support for EU policies to help the poor, the unemployed and disadvantaged children in different sample countries. The full regression tables of the logit models are reported in Model 2 in online appendix Tables F–H. To facilitate visual detection of a systematic pattern, the countries in are ranked from the most to the least generous net replacement rate for unemployment.Footnote5 The Nordic welfare states in our sample, Finland and Sweden, are the only two in which respondents are less likely to support EU-level policies for needy Europeans when those respondents believe that weaker countries have mismanaged their public finances. For example, the middle panel of shows that Swedish and Finish respondents who believe that the weaker member states are themselves to blame for their economic outcomes are, respectively, 14 and 9 percentage points less likely to support EU-wide policies targeted at the unemployed compared with their fellow nationals who do not hold national governments accountable. We further explored the logic of blame attribution to national governments by interacting a variable measuring distrust in other EU member states with the country dummies (Model 3 in online appendix Tables F–H and Figure B). These results are more straightforward because in the most generous welfare states (the Netherlands, Finland, Sweden, Germany and France) stronger distrust in other EU member states is associated with lower support for EU-level policies targeted at the poor, the unemployed and disadvantaged children, as expected. The same results are, however, also observed in Poland and – in the case of support for the unemployed – also for Italy and Spain. By contrast, in the two least generous welfare states of our sample – Greece and Hungary – the associations between distrust in other EU member states and support for EU-level welfare programmes are insignificant. In sum, although the negative association between national blame and support for EU welfare policies is not always stronger in more generous welfare states than in less generous ones (H2b), this hypothesis is partly confirmed by the data because the negative association between national blame and support for EU-level welfare programmes is observed in some of the generous welfare states while it is almost absent in the least generous welfare states.

Figure 3. Average marginal effects of attributing blame to national governments on support for EU-level welfare policies by country.

Notes: Horizontal lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Source: Authors’ elaboration on REScEU 2019 survey data.

Although not the focus of this study, the regression analyses also provide insights into the effects of socio-political attitudes and social-structural variables on public support for EU-level welfare policies. shows that those who are generally more supportive of European integration are more willing to show solidarity with needy Europeans, while exclusive national identities reduce people’s willingness to support the poor, the unemployed and disadvantaged children across Europe. This shows that deservingness judgements in European solidarity are not only linked to the concept of blame, but also relate to identity considerations, corroborating the assumption that people apply multiple deservingness criteria in expressing their solidarity with others (van Oorschot Citation2000). Furthermore, those who support redistribution within their own country are significantly more in favour of EU welfare policies targeted at vulnerable groups. A similar result is found when using left-right political orientation, indicating that leftist ideology increases support for EU-level policies to help needy Europeans (see online appendix Figures J and K). With regard to socio-structural variables, the results indicate that groups with a lower socioeconomic status are more supportive of EU welfare policies; having a lower education, lower subjective income, being unemployed and being in a family in which one of the members had received a social benefit (excluding pensions) in the last two years are all significantly associated with support for at least one of the EU targeted welfare policies under investigation. These findings align with previous research showing that lower socioeconomic status groups are more supportive of EU welfare policies targeted at the poor and the unemployed (Baute and Meuleman Citation2020; Kuhn et al. Citation2020).

Conclusion

Since the Eurozone crisis, and more recently during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, political and academic debate has intensified on whether the EU should take responsibility for the living standards of European citizens, in particular the most vulnerable. To contribute to this debate, the current study has explored public support for EU-level targeted welfare assistance towards three groups: the poor, the unemployed and disadvantaged children. We proposed a refined concept of multi-level blame attribution that captures the blaming of individual, national and supranational agency, and we postulated that the attributed locus of blame for economic outcomes determines what, if any, policy solutions citizens consider legitimate to remediate economic inequality and suffering in Europe.

Analysing data from an original cross-national opinion survey in 10 EU countries, we show that our notion of multi-level blame attribution is a fruitful theoretical lens through which to understand public support for European solidarity. Each of the three loci of blame constitutes a piece of the puzzle that explains the extent to which citizens support EU-level welfare assistance to redress economic suffering in Europe. First, we find that attributing blame to individuals is negatively related to support for needy groups across Europe. This finding extends the traditional welfare attitudes literature, which has examined the role of poverty attributions in public support for national welfare policies (Fong Citation2001; Hastie Citation2010), by showing that beliefs about individual responsibility of the needy are also appealed to when welfare policies transcend national boundaries. Second, we find that the association between national blame and support for EU welfare policies is conditional on the national context. In countries with more generous welfare states, we find that blaming national governments dampens support for EU welfare policies. However, our hypothesis is only consistently confirmed for the Nordic welfare states in our sample. This could be partly due to our operationalisation of national blame, which makes reference to weaker EU member states instead of individual EU member states and therefore does not allow a very fine-grained testing of the attribution of blame to national governments. Third, we find the belief that the EU is responsible for aggravating economic conditions in the weaker member states through its austerity policies, strengthens citizens’ demand for EU policies that compensate the most vulnerable members of society.

Our results have important implications for the literature on deservingness theory and European solidarity. First, our study elaborates deservingness theory (van Oorschot Citation2000) by applying it to the transnational arena. In the current study, the relevance of the control criterion of welfare deservingness has been tested in an original way and with regard to different actors simultaneously (that is, individuals, national governments and the EU). By doing so, we take into account that European welfare recipients are nested within member states, which are in turn nested within the EU polity. In addition to individual agency, the roles played by the national and EU actors are further components in citizens’ deservingness considerations with regard to policies that transcend national boundaries. Hence, we could argue that European social citizenship transforms deservingness rationales into a multi-layered debate. Deservingness in the European social space not only depends on the perceived behaviour of the individual recipient, but also on the responsibility that people ascribe to national and EU actors for economic outcomes. By integrating distinct levels of the multi-level governance architecture of the EU in our study, we are able to provide a deeper understanding of the basic deservingness question of who should get what and why. Our study has shown in a ‘fine-grained’ manner that Europeans clearly link cause and solution when expressing their solidarity with needy Europeans.

Second, our study advances European solidarity literature, which has been predominantly occupied with solidarity between EU member states rather than interpersonal solidarity between EU citizens (Bechtel et al. Citation2014; Daniele and Geys Citation2015; Gerhards et al. Citation2019; Vasilopoulou and Talving Citation2020). Our findings suggest that European solidarity is not necessarily undermined by Eurosceptic sentiments. Those who blame the EU for its negative effect on the social-economic development of the weaker member states are, interestingly, the strongest advocates of a more ‘Social Europe’. This reveals that feelings of social resentment that are linked to the consequences of EU policies, notably the strict fiscal policies during the Eurozone crisis, can be mobilised into support for further European integration steps, if these have a strong social dimension. In this sense, multi-level blame attribution thus informs us about how citizens conceive the future of the European project.

Importantly, our study opens up a new research agenda on multi-level blame attribution. Foremost, future research should elaborate on the measurement of multi-level blame attribution. In doing so, research could design measurements that capture the beliefs of the individual, as well as national and EU blame for economic outcomes outside a crisis context. While our operationalisations of blame attribution to national governments and the EU are framed within the Eurozone crisis, an important question remains with regard to the extent to which our theoretical model can be transferred to different crisis or non-crisis contexts. Since the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on EU member states appears more homogeneous than that of the Eurozone crisis, the attribution of blame for economic outcomes might be reshuffled. Instead of relying on three specific items, a more generic measurement instrument for multi-level blame attribution could be developed, in which respondents are asked the extent to which economic wellbeing is the result of (a) individual behaviour, (b) national policy making and (3) EU policy making. Such a generic measurement would allow the construction of blame differentials between the three levels which inform us about relative blame attribution. Furthermore, future research is needed to map the role of the national context in shaping multi-level blame attribution and subsequent support for EU-level welfare policies. Whereas the sample of this study did not allow for fully-fledged, multi-level modelling, the cross-national variation in the results suggests that macro-level factors such as welfare state generosity and macro-economic conditions explain diverging levels of support for EU social policies. Lastly, our work provides a promising theoretical framework for studying public support for social policy preferences in multi-level systems, including redistribution within and across EU member states. While the current study focusses on explaining support for EU-level social policies, it is not yet fully understood how the attribution of blame towards each level and combination of decision-making actors (individual, regional, national and EU) simultaneously shapes public preferences for policies at different levels in the EU’s current multi-level governance system. For instance, in a similar vein as the attribution of blame to the EU for economic outcomes triggers a stronger demand for EU welfare compensation, citizens may also turn towards their national government to ask for compensatory measures that cushion the negative effects of European integration. Because socioeconomic inequality may be further on the rise since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is crucial to understand how Europeans attribute blame for economic outcomes across different actors, and how that defines public preferences regarding the nature and scope of solidarity in Europe.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (2.4 MB)Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the CES 27th International Conference of Europeanists, 21–25 June, 2021 and at the 10th Conference of the Standing Group of the European Union, 10–12 June, 2021. We are grateful to the participants in these meetings for their comments and in particular to the discussants Julian Garritzmann and Irina Ciornei for providing excellent feedback. We also thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions on previous versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sharon Baute

Sharon Baute is Assistant Professor of Comparative Social Policy at the Department of Politics and Public Administration at the University of Konstanz. Her research covers topics in social policy, European integration and Euroscepticism, focussing in particular on public attitudes concerning the social dimension of the European Union. [[email protected]]

Alessandro Pellegata

Alessandro Pellegata is Associate Professor of Political Science at the Department of Social and Political Sciences, University of Milan. His research interests include electoral competition, political support, Euroscepticism and attitudes towards European solidarity, and corruption. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 The other CARIN criteria (attitude, reciprocity, identity and need) are not covered here, because they go beyond the scope of this study.

2 Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain.

3 Because of the limited number of countries in the sample, we provide an exploratory scatterplot analysis of country differences.

4 Overall, the results of country-specific models show that individual blame is negatively associated with public support for EU-level welfare policies, while EU blame is positively associated with it. However, given the lower number of observations in country-specific models, it is not surprising that in a very few cases the investigated relations are not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

5 Net replacement rates for the unemployed by sample countries are available in online appendix Table A.

References

- Albrekt Larsen, C. (2006). The Institutional Logic of Welfare Attitudes: How Welfare Regimes Influence Public Support. Hampshire: Ashgate.

- Attewell, David (2021). ‘Deservingness Perceptions, Welfare State Support and Vote Choice in Western Europe’, West European Politics, 44:3, 611–34.

- Baglioni, Sebastian, and Achem Hurrelmann (2016). ‘The Eurozone Crisis and Citizen Engagement in EU Affairs’, West European Politics, 39:1, 104–24.

- Baute, Sharon, and Bart Meuleman (2020). ‘Public Attitudes Towards a European Minimum Income Benefit: How (Perceived) Welfare State Performance and Expectations Shape Popular Support’, Journal of European Social Policy, 30:4, 404–20.

- Baute, Sharon, Bart Meuleman, Koen Abts, and Marc Swyngedouw (2018). ‘European Integration as a Threat to Social Security: Another Source of Euroscepticism?’, European Union Politics, 19:2, 209–32.

- Beaudonnet, Laurie (2015). ‘A Threatening Horizon: The Impact of the Welfare State on Support for Europe’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 53:3, 457–75.

- Bechtel, Michael M., Jens Hainmueller, and Yotam Margalit (2014). ‘Preferences for International Redistribution: The Divide over the Eurozone Bailouts’, American Journal of Political Science, 58:4, 835–56.

- Bellucci, Paolo (2014). ‘The Political Consequences of Blame Attribution for the Economic Crisis in the 2013 Italian National Election’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 24:2, 243–63.

- Blyth, Marc (2013). Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bullock, Heather E., Wendy R. Williams, and Wendy M. Limbert (2003). ‘Predicting Support for Welfare Policies: The Impact of Attributions and Beliefs about Inequality’, Journal of Poverty, 7:3, 35–56.

- Bulmer, Simon (2014). ‘Germany and the Eurozone Crisis: Between Hegemony and Domestic Politics’, West European Politics, 37:6, 1244–63.

- Burgoon, Brian (2009). ‘Social Nation and Social Europe: Support for National and Supranational Welfare Compensation in Europe’, European Union Politics, 10:4, 427–55.

- Conti, Nicolò, Danilo Di Mauro, and Vincenzo Memoli (2020). ‘Immigration, Security and the Economy: Who Should Bear the Burden of Global Crises? Burden-Sharing and Citizens’ Support for EU Integration in Italy’, Contemporary Italian Politics, 12:1, 77–97.

- da Costa, Leonor P., and José G. Dias (2015). ‘What Do Europeans Believe to be the Causes of Poverty? A Multilevel Analysis of Heterogeneity Within and Between Countries’, Social Indicators Research, 122:1, 1–20.

- Daniele, Gianmarco, and Benny Geys (2015). ‘Public Support for European Fiscal Integration in Times of Crisis’, Journal of European Public Policy, 22:5, 650–70.

- de la Porte, Caroline, and Elke Heins (2016). The Sovereign Debt Crisis, the EU and Welfare State Reform. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Devine, Daniel (2021). ‘Perceived Government Autonomy, Economic Evaluations, and Political Support during the Eurozone Crisis’, West European Politics, 44:2, 229–52.

- Donati, Niccolò, Alessandro Pellegata, and Francesco Visconti (2021). ‘European Solidarity at a Crossroads. Citizen Views on the Future of the European Union’. REScEU Working Paper, available at: http://www.euvisions.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/mass_survey_report_2019-1.pdf (accessed 17 August 2022).

- Dullien, Sebastian (2013). ‘A Euro-Area Wide Unemployment Insurance as an Automatic Stabilizer: Who Benefits and Who Pays?’, unpublished paper prepared for the European Commission (DG EMPL).

- European Commission (2017a). European Pillar of Social Rights. available at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/social-summit-european-pillar-social-rights-booklet_en.pdf.

- European Commission (2017b). Reflection Paper on the Deepening of the Economic and Monetary Union. available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/reflection-paper-emu_en.pdf.

- European Commission (2021). Council Recommendation Establishing a European Child Guarantee.

- European Parliament (2015). European Parliament Resolution of 24 November 2015 on Reducing Inequalities with a Special Focus on Child Poverty (2014/2237(INI)).

- European Parliament (2017). European Parliament Resolution of 24 October 2017 on Minimum Income Policies as a Tool for Fighting Poverty (2016/2270(INI)). available at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getdoc.do?pubref=-//ep//nonsgml+ta+p8-ta-2017-0403+0+doc+pdf+v0//en.

- Eurostat (2021a). People at Risk of Poverty or Social Exclusion. available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/sdg_01_10/default/table?lang=en.

- Eurostat (2021b). Unemployment Rate – Annual Data. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tipsun20/default/table?lang=en.

- Feagin, Joe R. (1972). ‘Poverty: We Still Believe That God Helps Those Who Help Themselves?’, Psychology Today, 6:6, 101–10.

- Ferrera, Maurizio (2005). The Boundaries of Welfare: European Integration and the New Spatial Politics of Social Protection. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ferrera, Maurizio (2017). ‘The Stein Rokkan Lecture 2016. Mission Impossible? Reconciling Economic and Social Europe after the Euro Crisis and Brexit’, European Journal of Political Research, 56:1, 3–22.

- Fong, Christina (2001). ‘Social Preferences, Self-Interest, and the Demand for Redistribution’, Journal of Public Economics, 82:2, 225–46.

- Fourcade, M., P. Steiner, W. Streeck, C. Woll, M. Fourcade, C. Woll, P. Steiner, C. Woll, W. Streeck, and M. Fourcade (2013). ‘Moral Categories in the Financial Crisis’, Socio-Economic Review, 11:3, 601–27.

- Garritzmann, Julian L., Martin R. Busemeyer, and Erik Neimanns (2018). ‘Public Demand for Social Investment: New Supporting Coalitions for Welfare State Reform in Western Europe?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:6, 844–61.

- Gerhards, Jürgen, Holger Lengfeld, Zsófia S. Ignácz, Florian K. Kley, and Maximilian Priem (2019). European Solidarity in Times of Crisis: Insights from a Thirteen-Country Survey. London: Routledge.

- Goldberg, Andreas C., Anna Brosius, and Claes H. De Vreese (2022). ‘Policy Responsibility in the Multilevel EU Structure: The (Non-) Effect of Media Reporting on Citizens’ Responsibility Attribution across Four Policy Areas’, Journal of European Integration, 44:3, 381–409.

- Gollust, Sarah E., and Julia Lynch (2011). ‘Who Deserves Health Care? The Effects of Causal Attributions and Group Cues on Public Attitudes about Responsibility for Health Care Costs’, Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 36:6, 1061–95.

- Grabbe, Heather (2012). The EU Must Re-Create Trust between Member States if the Benefits of Integration Are not to Ebb Away–And Persuade its Citizens that Credible State Institutions Can Be Rebuilt in Greece. EUROPP – European Politics and Policy. available at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2012/03/15/eu-trust-institutions/.

- Grauel, Jonas, Jana Heine, and Christian Lahusen (2013). ‘Who Is Afraid of the (Big Bad) European Union? European Integration and Fears about Job Losses’, in Wil Arts and Loek Halman (eds.), Value Contrasts and Consensus in Present-Day Europe: Painting Europe’s Moral Landscapes. Leiden: Brill, 19–43.

- Guinjoan, Marc, and Sandra Bermúdez (2020). ‘Nested or Exclusive? The Role of Identities on Blame Attribution during the Great Recession’, Nations and Nationalism, 26:1, 197–220.

- Hastie, Brianne (2010). ‘Linking Cause and Solution: Predicting Support for Poverty Alleviation Proposals’, Australian Psychologist, 45:1, 16–28.

- Heinkelmann-Wild, Tim, Berthold Rittberger, and Bernhard Zangl (2018). ‘The European Blame Game: Explaining Public Responsibility Attributions in The European Union’, in Andreas Kruck, Kai Oppermann and Alexander Spencer (eds.), Political Mistakes and Policy Failures in International Relations. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 171–89.

- Heuer, Jan-Ocko, and Katharina Zimmermann (2020). ‘Unravelling Deservingness: Which Criteria Do People Use to Judge the Relative Deservingness of Welfare Target Groups? A Vignette-Based Focus Group Study’, Journal of European Social Policy, 30:4, 389–403.

- Hobolt, Sara B., and James Tilley (2014a). Blaming Europe? Responsibility Without Accountability in the European Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hobolt, Sara B., and James Tilley (2014b). ‘Who’s in Charge? How Voters Attribute Responsibility in the European Union’, Comparative Political Studies, 47:6, 795–819.

- Jessoula, Matteo, and Ilaria Madama (2020). Fighting Poverty and Social Exclusion in the EU: A Chance in Europe 2020. London: Routledge.

- Kallio, Johanna, and Mikko Niemelä (2014). ‘Who Blames the Poor? Multilevel Evidence of Support for and Determinants of Individualistic Explanation of Poverty in Europe’, European Societies, 16:1, 112–35.

- Koos, Sebastian, and Dirk Leuffen (2020). ‘‘Beds or Bonds? Conditional Solidarity in the Coronavirus Crisis’ Universität Konstanz’, Policy Paper No. 01, July 1, 2020.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey (2008). West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kuhn, Theresa, Francesco Nicoli, and Frank Vandenbroucke (2020). ‘Economic Ideology, EU Support and Preferences for European Unemployment Insurance: Results of a Conjoint Experiment in 13 EU Member States’, Journal of European Public Policy, 27:2, 208–26.

- Kumlin, Staffan (2009). ‘Blaming Europe? Exploring the Variable Impact of National Public Service Dissatisfaction on EU Trust’, Journal of European Social Policy, 19:5, 408–20.

- Lahusen, Christian, and Maria Grasso (2018). Solidarity in Europe: Citizens’ Responses in Times of Crisis. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Leibfried, Stephan, and Paul Pierson (1995). European Social Policy: Between Fragmentation and Integration. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

- León, Sandra, Ignacio Jurado, and Amuitz G. Madariaga (2018). ‘Passing the Buck? Responsibility Attribution and Cognitive Bias in Multilevel Democracies’, West European Politics, 41:3, 660–82.

- Lepianka, Dorota, Wim van Oorschot, and John Gelissen (2009). ‘Popular Explanations of Poverty: A Critical Discussion of Empirical Research’, Journal of Social Policy, 38:3, 421–38.

- Matthijs, Matthias, and Marc Blyth (2015). The Future of the Euro. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Matthijs, Matthias, and Kathleen McNamara (2015). ‘The Euro Crisis’ Theory Effect: Northern Saints, Southern Sinners, and the Demise of the Eurobond’, Journal of European Integration, 37:2, 229–45.

- Mau, Steffen (2005). ‘Democratic Demand for a Social Europe? Preferences of the European Citizenry’, International Journal of Social Welfare, 14:2, 76–85.

- Mourlon-Druol, Emmanuel (2014). ‘Don’t Blame the Euro: Historical Reflections on the Roots of the Eurozone Crisis’, West European Politics, 37:6, 1282–96.

- Okolikj, Martin, and Stephen Quinlan (2016). ‘Context Matters: Economic Voting in the 2009 and 2014 European Parliament Elections’, Politics and Governance, 4:1, 145–66.

- Olmastroni, Francesco, and Alessandro Pellegata (2018). ‘Members Apart: A Mass-Elite Comparison of Mutual Perceptions and Support for the European Union in Germany and Italy’, Contemporary Italian Politics, 10:1, 56–75.

- Peña-Casas, Ramón, and Denis Bouget (2014). ‘Towards a European Minimum Income? Discussions, Issues and Prospects’, in David Natali (ed.), Social Developments in the European Union 2013, Brussels: ETUI Aisbl, 131–59.

- Pérez, Sofía A. (2019). ‘A Europe of Creditor and Debtor States: Explaining the North/South Divide in the Eurozone’, West European Politics, 42:5, 989–1014.

- Reeskens, Tim, and Tom van der Meer (2019). ‘The Inevitable Deservingness Gap: A Study into the Insurmountable Immigrant Penalty in Perceived Welfare Deservingness’, Journal of European Social Policy, 29:2, 166–81.

- Reinl, Ann-Kathrin, and Heiko Giebler (2021). ‘Transnational Solidarity among Political Elites: What Determines Support for Financial Redistribution Within the EU in Times of Crisis?’, European Political Science Review, 13:3, 371–90.

- Rüdig, Wolfgang, and Georgios Karyotis (2014). ‘Who Protests in Greece? Mass Opposition to Austerity’, British Journal of Political Science, 44:3, 487–513.

- Schneider, Simone M., and Juan C. Castillo (2015). ‘Poverty Attributions and the Perceived Justice of Income Inequality: A Comparison of East and West Germany’, Social Psychology Quarterly, 78:3, 263–82.

- Schraff, Dominik (2019). ‘Regional Redistribution and Eurosceptic Voting’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:1, 83–105.

- Stegmueller, Daniel (2013). ‘How Many Countries for Multilevel Modelling? A Comparison of Frequentist and Bayesian Approaches’, American Journal of Political Science, 57:3, 748–61.

- Teperoglou, Eftichia, André Freire, Ioannis Andreadis, and Jose Manuel L. Viegas (2014). ‘Elites’ and Voters’ Attitudes towards Austerity Policies and Their Consequences in Greece and Portugal’, South European Society and Politics, 19:4, 457–76.

- van Oorschot, Wim (2000). ‘Who Should Get What and Why? On Deservingness Criteria and the Conditionality of Solidarity among the Public’, Policy & Politics, 28:1, 33–48.

- van Oorschot, Wim, and Loek Halman (2000). ‘Blame or Fate, Individual or Social? An International Comparison of Popular Explanations of Poverty’, European Societies, 2:1, 1–28.

- Vandenbroucke, Frank, Catherine Barnard, and Geert De Baere (2017). A European Social Union after the Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Vasilopoulou, Sofia, and Liisa Talving (2020). ‘Poor Versus Rich Countries: A Gap in Public Attitudes towards Fiscal Solidarity in the EU’, West European Politics, 43:4, 919–43.

- Wilson, Traci L., and Sara B. Hobolt (2015). ‘Allocating Responsibility in Multilevel Government Systems: Voter and Expert Attributions in the European Union’, The Journal of Politics, 77:1, 102–13.