Abstract

Many citizens are sceptical of policies implemented to mitigate climate change. Existing research shows that citizens’ populist beliefs are significant determinants of climate scepticism. However, little is known about the underlying factors driving populist opposition to climate policies. To address this gap in the literature, this study develops structural equation models with new ideological measures using a high-quality probability sample of Dutch citizens (2019). The findings show that the relationship between populist attitudes and climate policy opposition is mediated through two anti-elite dispositions: the idea that climate science is unreliable and the belief that politicians exploit climate change for political gain. This relationship holds for left- and right-wing individuals alike. Moreover, a replication of a recent study shows that these findings hold alongside mechanisms rooted in institutional trust. These findings provide important evidence that populists’ opposition to climate policy is principally rooted in distrust in political and scientific elites.

Swift action is needed to mitigate the most severe consequences of climate change. However, such decisive action requires support from citizens. Public concern over climate change and public support for mitigating policies are prerequisites for legitimate political action on climate change, as such policies affect citizens’ everyday lives and behaviours. While citizens increasingly accept that climate change is happening, a great number of people remain sceptical about human-induced climate change and, in turn, whether measures should be taken to address it (Drews and Van den Bergh Citation2016; Harring et al. Citation2019; Pidgeon Citation2012; Stoutenborough et al. Citation2014).

Despite the growing body of literature on the determinants of climate attitudes, at least two important gaps remain. A first gap in the literature regards the relationship between populism and climate action. Existing research suggests that variables tied to political preferences overshadow socioeconomic determinants of climate change attitudes (Hornsey et al. Citation2016). For instance, right-wing citizens display higher levels of ‘climate change scepticism’ than left-wing citizens (McCright and Dunlap Citation2011; Poortinga et al. Citation2019; Whitmarsh Citation2011). Moreover, there is mounting evidence that citizens with more populist attitudes are less likely to believe in human-induced climate change (Huber Citation2020; Huber et al. Citation2020, Citation2021). However, it remains unclear how the latter relate to support for climate action (for an overview, see Drews and Van den Bergh Citation2016). Indeed, most studies use standard questions about climate scepticism or environmental policy support rather than variables capturing support for climate policy (Hornsey et al. Citation2016; McCright and Dunlap Citation2011; Poortinga et al. Citation2019; Whitmarsh, Citation2011; Huber Citation2020; Huber et al. Citation2021; but see: Huber et al. Citation2020). This matters, as a lack of support for climate policy, or ‘response scepticism’, is relevant for ‘a much wider general audience’ (Van Rensburg Citation2015: 5). Consequently, it has a bigger potential to derail swift climate action. Examining the relationship between populist attitudes and support for climate policy is thus important.

A second lacuna concerns the attitudinal factors linking populist attitudes to climate action. We know little about the mechanisms underlying ideological opposition to climate action. Assessing such attitudinal factors underlying climate policy opposition is crucial for an understanding of why populist citizens often reject climate policy. The one study that does dig into the why-question examines climate scepticism rather than support for climate mitigation policy (Huber et al. Citation2021). What is more, the mediating factors that Huber et al. (Citation2021) identify are rather broad attitudes, such as instutional trust, which are not necessarily related to climate action.

Our study adds to this literature by being the first to analyse the underlying mediators connecting populism to support for climate mitigation policy. It does so in the Dutch context in which both right-wing and left-wing populist parties are active, allowing us to provide a more complete picture of the interplay between populism and left-right ideology. Our main contribution to the literature is twofold. A first contribution is related to the mediators connecting populism to support for climate policies. Here, we advance the hypothesis that opposition to climate action is rooted in climate-specific anti-elite attitudes. We find that the relationship between populism and climate policy opposition is not only mediated by the belief that the findings of climate scientists on climate change are unreliable, but also via the idea that climate mitigation policies are implemented for political gain (but not via the idea that they are implemented for financial gains). These three mediating variables are new and specific to climate policy. Our second contribution that we examine how left-right ideology moderates the relationship between populism and climate policy opposition. Specifically, we find that regardless of left-right identification, highly populist respondents tend to oppose climate mitigation policy, and that left-right ideology does not moderate the adherence to anti-elite climate beliefs.

Doing so, this study builds on the work of Huber et al. (Citation2021) regarding the effects of institutional trust and trust in science on climate scepticism in Austria. To assess to what extent our findings cumulate with that study, we also provide an additional analysis where we replicate their study on our sample, i.e. one with a different context (the Netherlands rather than Austria) and a different, but related, dependent variable (support for climate policy rather than climate scepticism). We find that Huber et al.’s (Citation2021) findings also hold for our sample. In addition, we find that our climate-specific anti-elite mediators have a substantial effect on climate policy opposition – alongside the broader attitudes of institutional trust and general science scepticism. The finding that anti-elite sentiments independently mediate the relationship between populist attitudes and climate policy opposition is in line with recent work by Geurkink et al. (Citation2020), who find that populist attitudes is distinct from political trust.

To make our empirical contribution, we first collected new data on climate policy support. We then developed structural equation models (SEM) with measures probing the mechanisms underlying populism’s relationship to climate policy opposition.Footnote1 By doing so, we capture which elites are key to populist citizens’ climate policy opposition by examining anti-elite sentiments pertaining to scientific elites, political elites, and financial elites.Footnote2 Furthermore, we examine how left-right self-identification moderates the relationship between populism, climate-specific anti-elite sentiments, and opposition to climate mitigation policy. These measures were implemented in a unique, nationally representative 2019 sample of Dutch citizens in the LISS panel of CenterData (N = 1133). Dutch citizens’ concerns over climate change are largely in line with the European average (Poortinga et al. Citation2019). Moreover, populist politics are abundant in the Netherlands in terms of both parties and citizens and on both the ideological left and right (Meijers and Zaslove Citation2021; Zaslove et al. Citation2021).

Attitudes towards climate policy

Climate scepticism is a multifaceted concept covering different aspects related to the evidence of climate change and human responses to it (Van Rensburg Citation2015). While a lot of research has been devoted to examining whether citizens believe in human-induced climate change, in recent years, research into individual-level drivers of support for climate policy has also increased (Drews and Van den Bergh Citation2016; Van Rensburg Citation2015). Knowledge of what drives such support is important, as it enables policymakers to anticipate public responses and, in turn, craft more effective climate policies (Drews and Van den Bergh Citation2016: 856). Individual and societal risk perceptions with regard to climate change, for instance, play a significant role in explaining support for far-reaching climate policies (Drews and Van den Bergh Citation2016: 858). In addition, ideologies and value orientations constitute important drivers of support for climate policy. Notably, support for climate action is high among left-wing citizens and those who hold pro-environmental values. Low trust in political institutions, a correlate of populism (Geurkink et al. Citation2020), also explains climate change beliefs (see Huber et al. Citation2021). What remains unclear, however, is whether populist orientations drive opposition to climate policy (for information on the relationship between populist attitudes and support for environmental protection see Huber Citation2020) and, more importantly, the underlying mediators through which this may occur. Similarly, while research indicates that right-wing citizens are more likely to reject climate action, the interplay between populism and left-right ideology is still unclear. Therefore, this article examines whether populist citizens are more likely to reject climate action, assesses the substantive mediators driving these hypothesised relationships, and investigates how this relationship is moderated by left-right ideology.

Populist attitudes and climate policy opposition

The literature on climate scepticism has overwhelmingly found that citizens’ political orientations are important determinants of climate change beliefs (Hornsey et al. Citation2016). One of these political orientations is populism (Lockwood Citation2018). In what follows, we first discuss the concept of populism and then relate it to climate change by examining the factors that may connect populism to (a lack of) support for climate policy.

Populism can be defined as a set of ideas positing that there is an essential conflict between ‘the pure people’ and ‘the corrupt elite’ (Hawkins and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2018). ‘Ordinary people’ are seen as a homogenous entity with whom the only legitimate source of political power resides. The people’s interests are seen as indivisible, as they share one volonté générale – one general will (Mudde Citation2004: 543). Populism deems the aims and interests of the elites, by contrast, to be inherently incompatible with those of ordinary people. Populism is a global phenomenon that can be found on both the ideological left and right among political parties and citizens (Meijers and Zaslove Citation2021; Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel Citation2018). Citizens with populist attitudes tend to hold lower levels of political trust and show low levels of external efficacy, suggesting that they feel that they are not heard by politicians (Geurkink et al. Citation2020; Spruyt et al. Citation2016). In contrast, citizens with populist attitudes boast high levels of internal efficacy, meaning they perceive themselves to be very competent to understand politics (Rico et al. Citation2020). In line with the assertion that the will of ordinary people should constitute the core of political decision making, populist citizens perceive themselves to be informed and, as a result, feel capable of challenging political elites on certain issues (Rico et al. Citation2020: 799).

The issue of climate change is particularly subject to challenges from citizens with a higher degree of populist attitudes. While research into the relationship between populism and support for climate action is limited, evidence from the UK and Austria shows that populist citizens are more likely to be sceptical of anthropogenic climate change and climate policy (Huber Citation2020; Huber et al. Citation2021). Although extreme weather events may bring the urgency of climate action to the fore (cf. Howe et al. Citation2019), climate change remains rather distant from most European citizens’ everyday lives (Huber et al. Citation2021). As a result, discussions about climate change are generally informed by technical scientific reports. Despite their high levels of internal efficacy (Rico et al. Citation2020), populist citizens also tend to be less educated, meaning they are less equipped to evaluate the scientific evidence behind anthropogenic climate change (Hornsey et al. Citation2016). Moreover, climate-oriented policy initiatives are usually negotiated at the international level (e.g. 1992 Kyoto Protocol, 2015 Paris Agreement), feeding the perception of climate policies as highly elite-driven (Huber et al. Citation2020: 376).

Importantly, populist citizens are prone to conspiratorial beliefs (Castanho Silva et al. Citation2017). As conspiracy theories are ‘explanations of events’ (Castanho Silva et al. Citation2017: 425), they influence beliefs about why the climate is changing (i.e. whether climate change is human-induced). This, in turn, influences beliefs about whether climate change can or should be countered (Lewandowsky et al. Citation2013). The issue of climate change is arguably one that is particularly vulnerable to conspiratorial beliefs. The climate issue is complex, abstract, and surrounded by uncertainty, leaving ample room for interpretation (Huber Citation2020: 7). Taken together – the nature of climate change, the propensity of populist citizens to challenge elites, and conspiratorial beliefs – we expect citizens with stronger populist convictions to be more likely to be opposed to climate mitigation policies.

But how would this relationship between populist attitudes and climate scepticism materialize? We argue that populists’ anti-elite dispositions account for their opposition to climate policies. Indeed, most studies on populism and climate change emphasise populists’ anti-elitism (Huber Citation2020; Jylhä and Hellmer Citation2020; Lockwood Citation2018). Yet, who constitutes the ‘elite’? Arguably, the ‘elite’ is not limited to the political establishment, as populists also criticise other types of actors, including economic, cultural, and media elites (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2017: 12–13). Unfortunately, extant empirical studies rarely specify which elites are targeted by populist attitudes. We contribute to the populist attitude literature by distinguishing anti-elite sentiment towards different elites in the context of climate policy.

First, in the context of climate change, anti-elitism may refer to scientists studying climate change (Cann and Raymond Citation2018). The scientific process of knowledge creation is often complex and opaque, especially when dealing with abstract, large-scale phenomena such as climate change (Van Rensburg Citation2015: 4). Indeed, ‘the overarching framework for climate policy is constructed by distant international processes of science’ (Lockwood Citation2018: 724). Huber et al. (Citation2020) show that anti-science views mediate the relationship between populism and climate scepticism. As a result of such anti-science views, populists may be more likely to believe the evidence for climate change is unreliable, which in turn may erode their support for climate mitigation policies. Hence, we expect an important mediator of the relationship between populist attitudes and climate policy opposition to be the conviction that climate scientists’ evidence for climate change is unreliable:

Hypothesis 1a: Populist attitudes have an indirect positive effect on climate policy opposition via the belief that climate scientists’ evidence for climate change is unreliable.

Hypothesis 1b: Populist attitudes have an indirect positive effect on climate policy opposition via the belief that politicians exploit climate change for their own political gain.

Hypothesis 1c: Populist attitudes have an indirect positive effect on climate policy opposition via the belief that some people benefit financially from climate action.

Populist attitudes, left-right ideology and climate policy opposition

Given that populism centres on abstract concepts such as ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’, it typically needs ‘host ideologies’ to provide substantive meaning to these concepts (Mudde Citation2004). Indeed, left-wing populists have a different understanding of who is part of the people/elite than right-wing populists. Given that left-wing and right-wing individuals hold different views about climate policy, it is plausible that the relationship between populist ideation and climate policy opposition differs for left- and right-wing populists.Footnote3 Therefore, in this section we discuss how the impact of populist attitudes on climate policy opposition could be moderated by left-right ideology.

Existing evidence shows that citizens’ left-right political orientations indeed affect their views on climate change; citizens on the left are more likely to believe that anthropogenic climate change is real and that measures against climate change are necessary (McCright et al. Citation2016; McCright and Dunlap Citation2011; Poortinga et al. Citation2019; Whitmarsh Citation2011; Ziegler Citation2017). While most of the aforementioned studies examined the impact of ideology on climate scepticism (Hornsey et al. Citation2016; Whitmarsh Citation2011), the relationship also stands for support of climate mitigation policies (McCright et al. Citation2016). To explain these findings, the literature advances two types of mechanisms.

A first type of explanation suggested by the literature is that climate change mitigation policies may be viewed as at odds with economic prosperity (Huber Citation2020). For instance, right-wing citizens may view a carbon tax as something that will hamper productivity and increase costs for both individuals and companies. Moreover, climate policy may be viewed as a form of market regulation – as mitigation policies may involve far-reaching regulations for companies – to which citizens are ideologically predisposed in many different ways (Harring and Sohlberg Citation2017: 281).

A second type of explanation that is offered in the literature is related to party cues. In a context of a highly complex issue with a high degree of uncertainty, such as climate change, many people ‘use cues from parties as a cognitive shortcut’ (Stecula and Merkley Citation2019: 2). Right-wing political actors tend to be more reluctant to embrace climate mitigation policies, or prioritise other issues, such as immigration, crime and economic growth (cf. Lockwood Citation2018). Moreover, climate and environmental issues could also be subsumed under the cultural dimension, in which party positioning on climate policy is part and parcel of a broader polarisation on cultural issues. Hence even when right-wing individuals are not so much concerned about the impact on economic prosperity, they may still be more opposed to climate policies because they are more likely to take cues from political actors who are opposed to such policies.

Now we turn to the question how left-right self-placement may moderate the three mediating factors we identified in the previous section. The first mediator focussed on the belief that the scientific data underlying climate change was unreliable. Here, left-right ideology is likely to moderate the relationship between populist attitudes and climate policy. Particularly populist radical right politicians tend to call into question the evidence upon which climate policy is based (Fraune and Knodt Citation2018). Indeed, ‘the political right is generally responsible for conspiracy theories that call into question the legitimacy of climate science’ (Uscinski and Olivella Citation2017: 14). This science scepticism is, arguably, less the case for left-wing populist respondents, who tend to accept that human-induced climate change is happening, but rather question the effects of climate policies on the people and the motives of politician pursuing those policies (see below). Hence, we hypothesise that:

Hypothesis 2a: The more right-wing a respondent is, the stronger the effect of populist attitudes is on the belief that climate scientists’ evidence for climate change is unreliable.

Hypothesis 2b: Left-right ideology does not significantly moderate the effect of populist attitudes on the belief that politicians exploit climate change for their own political gain. (null hypothesis)

A third mediator we identified relates to the belief that some people may benefit financially from climate policies. This argument may resonate particularly with left-wing populists who define the elite in economic terms and often see policies as hijacked by economic special interests (cf. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2017: 13). Indeed, populist radical left conspiracy theories about climate action typically centre on the role of ‘big business’ and ‘illicit profiteering’ (Uscinski and Olivella Citation2017: 14). Hence, we expect that:

Hypothesis 2c: The more left-wing a respondent is, the stronger the effect of populist attitudes is on the belief that some people benefit financially from climate action.

Data and methods

Limited data availability has hindered researchers’ ability to conduct innovative research into climate policy attitudes. The use of standard measures in prominent surveys, such as the European Social Survey (Poortinga et al. Citation2019) and Gallup (McCright and Dunlap Citation2011), precludes investigation into how populist attitudes affect opposition to climate policy, let alone study specific anti-elite sentiments as mediators connecting populism to opposition to climate policies. Existing data sources rarely measure citizens’ attitudes towards both climate change and populism. Thus, we fielded a new survey in the Netherlands in 2019 specifically designed to assess citizens’ degree of populism, views on climate policy, and the attitudinal pathways that connect them.Footnote4

Case selection: The Netherlands

Dutch citizens’ concerns about climate change are largely in line with the European average (Poortinga et al. Citation2019). The issue of climate policy was rather salient around the time of our fieldwork; the government was negotiating a climate law that would enshrine the goal of reducing Dutch CO2 emissions by 49 per cent by 2030 and by 95 per cent by 2050 in national law. A climate agreement was being negotiated among several stakeholders regarding how to achieve this goal. These negotiations triggered a backlash, with one far-right populist party – the Forum for Democracy (Forum voor Democratie, FvD) – explicitly campaigning against climate action in advance of the provincial elections in March 2019. Both the FvD and the Green party (Green Left [GroenLinks]) were viewed as the largest winners of these elections, suggesting that climate policy constituted a salient issue at the time. The 2019 Dutch case has the advantage of having both a populist party on the left, the Soclialist Party (Socialistische Partij, SP), and several populist parties on the right: Freedom Party (Partij voor de Vrijheid, PVV) and Forum for Democracy. While Huber et al. (Citation2021), for instance, focussed on Austria where only right-wing populist parties are present, our study allows us to study the relationship between populist attitude and climate attitudes in a context where also a left-wing populist party is present. The SP indeed noted its opposition to current climate policies, as it wants ‘climate justice’ and felt ordinary people bore the blunt of the burden while large companies did not contribute their fair share.Footnote5

Data

Our data were collected by the Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences (LISS) panel, a high-quality probability sample survey panel run by CenterData at the University of Tilburg. We principally rely on an original dataset collected between June and July 2019. We use the panel structure of the LISS data to complement our data with variables from another recent LISS survey. We take the left-right self-identification variable as well as the trust items for our replication of Huber et al.’s (Citation2021) study from wave 11 of the LISS Core Study ‘Political and Values’ module fielded between December 2018 and March 2019.

A total of 1133 respondents completed the surveys with non-missing values on the variables of interest. The final dataset consists of 55.1 per cent males. The mean age is 58 years old. In terms of education, 40.5 per cent of the respondents were higher educated (higher vocational education and university), 34.6 per cent were middle educated (higher secondary education and secondary vocational education), and 24.9 per cent were lower educated (primary school and prevocational secondary education). Data from the Dutch Central Agency for Statistics estimate that, in 2019, 49.7 per cent of the Dutch population was male, the mean age was 42 years old, and 30 per cent of the population was higher educated, 37 per cent was middle educated, and 31 per cent was lower educated. Thus, while our sample is by and large representative of the Dutch population, our sample is somewhat more male, older, and higher educated.Footnote6 At the same time, the benefit of a probability sample LISS provides is that self-selection bias is likely lower than in other online panels.

Dependent and independent variables

While some studies measure support for ‘specific’ government policies to combat climate change, we are interested in ‘diffuse’ support for government climate change mitigation policies (Easton Citation1975). Instead of assessing support for specific policy measures, such as a carbon tax and road pricing (Hammar and Jagers Citation2006; Kim et al. Citation2013), diffuse climate policy support refers to ‘overall evaluations’ of the necessity of climate policy (Easton Citation1975: 444). While this measure lacks specificity, a distinct benefit is that it abstracts from specific design features of individual climate policies, which are shown to draw varying levels of support (Drews and Van den Bergh Citation2016: 859). Our dependent variable opposition to climate policy is measured with the statement, ‘It is necessary to take public policy measures in order to tackle climate change’, which respondents can answer on a five-point Likert scale. We invert the variable so that higher values indicate higher levels of opposition to climate change mitigation policy. As we are interested in overall support for climate action, we do not specify the level of government at which these mitigation measures are taken. Such specification would likely prime respondents’ exogenous views on the institution in question, confounding support for climate policy with institutional evaluations.

The key independent variable of interest concerns respondents’ populist attitudes. We measure populist attitudes using the populism scale developed by Akkerman et al. (Citation2014). This scale consists of six items (see ) and is designed to capture the three core elements of populism. All six items are measured on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1, ‘fully disagree’, to 5, ‘fully agree’. Through these six items, we operationalise populism as a latent variable (Castanho Silva et al. Citation2018).

Table 1. Populist attitude items.

With three new measures, we aim to capture the mediators between respondents’ climate policy opposition and their populist attitudes First, we measure the belief that climate scientists’ evidence for climate change is unreliable with the following item: ‘‘Climate scientists’ evidence for climate change is unreliable’ (science unreliable). Second, we measure anti-political elite dispositions with the following item: ‘Politicians mainly talk about climate change for their own political gain’ (political gain). Third, we assess the fear that special interests – the economic elite – benefit from climate action with the following item: ‘There is a group of people who benefit financially from the government’s climate policies’ (financial gain).Footnote7 All these variables are measured on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 represents ‘fully disagree’ and 5 represents ‘fully agree’.

Respondents’ ideological orientation is measured with the item left-right self-identification, which asks respondents to place themselves on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 represents ‘left’ and 10 represents ‘right’. We also measure a number of control variables that may confound the relationship between climate policy opposition and our explanatory variables of interest. We control for gender, as evidence shows that women are more likely to believe that climate change is a problem and that mitigation policies are necessary (Hornsey et al. Citation2016). We control for age, as research shows that older citizens are less likely to believe in anthropogenic climate change (Hornsey et al. Citation2016) and less likely to accept the need to combat it (McCright et al. Citation2016). Furthermore, we control for educational level, as it has been shown to influence climate change attitudes (Hornsey et al. Citation2016). Education is measured by the highest degree that respondents have obtained; it is operationalised into three categories: (1) lower educated (primary school and prevocational secondary education), (2) middle educated (higher secondary education and secondary vocational education), and (3) higher educated (higher vocational education and university). All three variables have also been shown to be predictors of populist attitudes (Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert 2018: 11). Online appendix A provides an overview of all descriptive statistics for all variables.

It needs to be stressed that our dataset did not include data on emotional predispositions and perceptions of well-being. As suggested by meta-analyses on the determinants of climate policy support and populist attitudes (Drews and Van Den Bergh Citation2016; Marcos-Marne et al. Citation2022), these are plausible confounders of the relationship between populism and support for climate policy. So far, no studies on populism and climate change attitudes have included these variables, but they may affect the relationships we find. While including our set of control variables (gender, age, education) is in line with other studies on populism and climate change attitudes (e.g. Huber et al. Citation2021), this is nevertheless a limitation to keep in mind, and we will return to this in the conclusion.

Analytical approach: structural equation modelling

We employ structural equation modelling (SEM) to test our hypotheses, enabling us to fit a measurement model for the latent construct of populist attitudes and estimate the direct and indirect effects between several pathways in a single model (Kline Citation2011). We construct the structural equation model using two steps. First, we apply confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to fit the measurement model of our latent construct, populist attitudes. Second, we incorporate the latent variable of populist attitudes into a structural regression model to test our hypotheses. In a first step, we estimate a model including only the direct effect of populist attitudes on climate scepticism as well as some controls. To test Hypotheses 1a-1c, we then estimate a model including all the indirect effects of populist attitudes via the three theorised mediators. We control for age, gender and education in all of the pathways. We estimate our models in R using the lavaan package (Rosseel Citation2012). To test Hypotheses 2a-2c, we estimate whether left-right self-placement affects the mediating relationship between populist attitudes and climate policy opposition via anti-elite sentiment using OLS models and first-stage moderated mediation models. In a last step, we replicate a recent study by Huber et al. (Citation2021) who examined the mediating role of institutional trust and general science scepticism on climate attitudes in Austria. Doing so, we ascertain that our hypothesised effects have similar effects when also including the mediation paths related to institutional trust and general science scepticism, as proposed by Huber et al. (Citation2021).

Results

In order to ensure the validity of our latent construct of populist attitudes, in the first step we specify the measurement model using CFA. Model fit for the measurement model is assessed using the following widely employed goodness-of-fit statistics (Hu and Bentler Citation1999): the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (< 0.08), the comparative fit index (CFI) (> 0.95), and the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) (< 0.06).Footnote8 The measurement model indicates a good fit (RMSEA = 0.069; CFI = 0.984; SRMR = 0.022) when we add residual covariance between items POP1 and POP2 and between items POP2 and POP3. These items tap into the people-centric aspect of populism, and this covariance structure has been validated in previous studies (e.g. Geurkink et al. Citation2020).

Having specified our measurement model and confirmed its validity, we add the measurement model to a structural regression model. In a first step, we estimate a model that only includes the direct effect of populist attitudes on opposition to climate policies controlling for age, education level and left-right self-placement. We test whether respondents’ populist attitudes are related to climate policy opposition. In line with previous studies (Huber Citation2020; Huber et al. Citation2020, Citation2021), the results show a positive significant effect (0.247, p-value < 0.001), indicating that people with higher populist attitudes are indeed more likely to oppose climate policies, while controlling for left-right orientation, age, education, and gender.Footnote9

The mediating role of different types of anti-elite sentiments

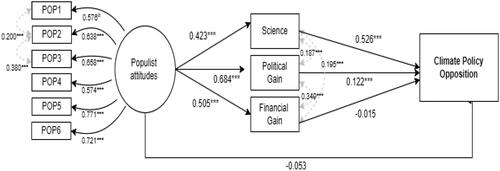

In a second step, we assess whether the effect of populist attitudes on climate policy opposition is mediated by our three hypothesised mediators. We predicted that populist attitudes have an indirect positive effect on opposition to climate change mitigation policies via the belief that climate scientists’ evidence for climate change is unreliable (Hypothesis 1a), the belief that politicians exploit climate change for political gain (Hypothesis 1b), and the belief that some people benefit financially from climate action (Hypothesis 1c). To do so, we add the mediating pathways to the abovementioned structural model. presents a visualisation of the model, including factor loadings and standardised regression estimates. Online appendix C (Model 2) presents the estimates of the control variables, as well as the indirect effects and total effects of populist attitudes on climate policy opposition via the three mediating variables.

Figure 1. Indirect model of climate policy opposition.

Note: N = 1133. No significance level because factor loading is fixed for identification purposes. Grey dotted lines indicate covariances; bold lines indicate statistically significant indirect effects (p < 0.05); * = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01; *** = p < 0.001. Goodness of fit M1: χ2 (df = 51, N = 1133) =351.38, p-value < 0.001; CFI = 0.936; RMSEA = 0.072; SRMR = 0.0.81. Indirect effects and total indirect effects are reported in online appendix C. Endogenous variables are controlled for gender, age, and education. Control variables are excluded for visualisation purposes; see online appendix C (Model 2) for estimates of the control variables.

Confirming Hypothesis 1a, the results indicate that populist attitudes are positively correlated with the belief that evidence for climate change is unreliable, which is, in turn, positively correlated with opposition to climate change. The indirect path from populist attitudes to opposition to climate action via the ‘science is unreliable’ variable is positive and significant (0.223, p < 0.001). As postulated in Hypothesis 1b, populist attitudes are positively correlated with the belief that politicians exploit climate change for political gain; this belief, in turn, has a positive effect on opposition to climate action. The indirect path is positive and significant (0.084, p < 0.01), though it is less substantial than the indirect effect associated with the belief that the scientific evidence for climate change is unreliable. Regarding the third indirect path, we find that populist attitudes significantly affect the belief that some people benefit financially from climate policies. However, this belief does not significantly affect opposition to climate policies. Therefore, there is no significant indirect effect of populist attitudes on opposition to climate policies via the belief that some people benefit financially from climate policies.Footnote10

Interestingly, the inclusion of these three indirect effects renders the direct effect of populist attitudes insignificant. This suggests that the two significant indirect effects related to anti-elite sentiments towards climate scientists and political elites drive the positive relationship between populist attitudes and climate policy opposition. In other words, populists’ rejection of climate action seems to be rooted in distrust towards scientific and political elites. Overall, we find that the total effect of populist attitudes on opposition to climate action is positive (0.245, p < 0.001). Regarding the control variables (see online appendix C, Model 2), we find no significant effect of gender or age on opposition to climate action. However, we find that less-educated respondents are more likely to oppose climate policy. Moreover, we find that right-wing respondents are more strongly opposed to climate policy.

The moderating role of left-right ideology

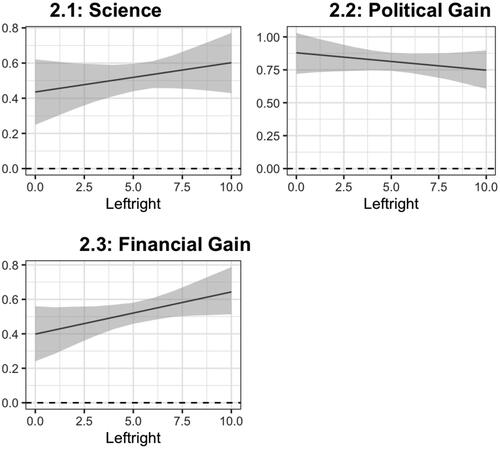

Does respondents’ left-right ideology alter the relationship between populist attitudes and anti-elite climate attitudes examined in the previous section? And how does this affect the relationship between populist attitudes on climate policy opposition? Hypothesis 2a formulated the expectation that for right-wing individuals the effect of populist attitudes on the belief that scientists’ evidence for climate change is unreliable is significantly stronger given that especially populist radical right parties spread narratives that call into question the legitimacy of climate science. To examine this, we conduct an OLS regression with ‘science’ as the dependent variable (see online appendix D). visualises the result. We see that for both left- and right-wing respondents the effect of populist attitudes on ‘science’ is positive and statistically significant. While the effect seems to be more pronounced for right-wing respondents, as hypothesised, the overlapping confidence intervals suggest the difference between left- and right-wing respondents is not statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

Figure 2. Marginal effects plots of the effect of populist attitudes on anti-elite sentiment for different levels of left-right placement.

Note: N = 1133. Estimates based on OLS models with interaction between populist attitudes and left-right placement shown in online appendix D.

Hypothesis 2b stipulated that we would expect to find no statistically significant difference between respondents who identify as left-wing and those who identify as right-wing on support for the idea that politicians commit to climate policy for their own political gain. Indeed, here we expected the anti-elite attitudes linked to populism to prevail over the host ideology it was attached to. In line with this expectation, we see in that the effect of populist attitudes on ‘political gain’ is similar for left- and right-wing individuals. Whilst the slope points faintly downward, suggesting that the effect is slightly more pronounced among extreme leftists, this difference is not statistically significant.

Lastly, Hypothesis 2c formulated the expectation that for left-wing individuals the effect of populist attitudes on the idea that there is a financial elite that benefits economically from climate mitigation measures would be more pronounced than for their right-wing counterparts. However, there is no evidence to support this hypothesis. For both left- and right-wing respondents, the effect of populist attitudes on ‘financial gain’ is significant. The results visualised in show that contrary to our expectation, if anything, the effect of populist attitudes on ‘financial gain’ seems to be more pronounced for right-wing respondents instead of left-ring respondents.Footnote11

These findings hold when we specify a structural equation model with a first-stage moderation mediation between the main independent variable (populist attitudes) and the key mediators (‘science unreliable’, ‘political gain’, and ‘financial gain’) (see online appendix E.1–E.3). Specifically, we estimate whether the indirect effect of populist attitudes on climate policy opposition via anti-elite sentiment (‘science unreliable’, ‘political gain’, or ‘financial gain’) depend on respondents’ left-right ideology. In line with the findings presented in c, we find that left-right self-placement does not moderate the mediating relationship between populist attitudes on climate policy opposition via the belief that science is unreliable or the belief that politicians talk about climate policies for their own political gain. Left-right ideology does slightly moderate the relationship between populist attitudes on climate policy opposition via the belief that some groups gain financially from climate policies, being more strongly expressed among right-wing respondents.

Anti-elitism, institutional trust and trust in science: a replication

Finally, we assess whether our results cumulate with those of a recent article that used SEM to assess the mediating factors guiding the relationship between populist attitudes and climate scepticism. Huber et al. (Citation2021) study the mediating role of institutional trust and attitudes towards science attitudes on climate scepticism in Austria (2017–2019). They found that populist attitudes are significantly mediated through institutional trust, attitudes towards science, and left-right self-identification. We first replicate this model for our dependent variable climate policy opposition (see online appendix F).Footnote12 Our findings align with theirs: populism is substantively and significantly mediated through institutional trust, trust in science, and left-right self-identification. Now, how does this alternative model speak to our indirect model presented in ? To assess this, we incorporate our theorised mediators – unreliable science, political gain, and financial gain – into Huber et al.’s (Citation2021) replication analysis. Online appendix G shows that the indirect pathways from populist attitudes to opposition to climate action – unreliable science and political gain – remain sizeable and statistically significant. Political gain and belief in science are found to constitute important independent mediators of the relationship between populist attitudes and climate policy opposition, alongside institutional trust and science scepticism. This suggests that discontent towards climate policy is not just structured by broad trust attitudes, but also by specific climate-related anti-elite dispositions. Our finding that anti-elite sentiments independently mediate the relationship between populist attitudes and climate policy opposition is in line with recent work by Geurkink et al. (Citation2020), who find that populist attitudes are distinct from political trust.

Conclusion

Climate change is one of the central challenges of our time. Immediate decisive action is necessary to prevent the most severe potential outcomes. However, effective climate change mitigation policies rely on widespread public support. Recent studies show that citizens’ populist attitudes matter for climate attitudes. In this article, we set out to understand why citizens with populist attitudes reject climate policy. Employing data from the Netherlands in 2019, we studied the mediating factors connecting populist attitudes and climate change mitigation policies.

Our structural equation models show that the relationship between populism and opposition to climate action is mediated through two anti-elite dispositions: the belief that climate science is unreliable and, to a lesser extent, the belief that politicians exploit climate change for political gain. Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not uncover an indirect effect of populist attitudes through the belief that some people benefit financially from climate action. Since we find no remaining significant effect of populist attitudes on climate policy, our findings suggest that populists’ opposition climate measures is principally rooted in anti-elite views regarding scientists’ and politicians’ actions.

What is more, we find that citizens’ left-right self-placement does not moderate the mediating relationship between populist attitudes and climate policy opposition via anti-elite sentiment. For each mediating variable (‘unreliable science’, ‘political gain’, and ‘financial gain’), we found that populist attitudes had consistent positive effect on anti-elite sentiment – with no significant difference between left- and right-wing individuals. All in all, this suggests that citizens with higher populist attitudes are susceptible to messages coming from populist politicians in general, regardless of these politicians’ position on the left-right spectrum.

In a final step, we replicated a previous study which found that institutional trust and trust in science affect climate change beliefs (Huber et al. Citation2021). Applied to the dependent variable of climate policy opposition, we corroborate Huber et al.’s findings. More importantly, however, we find that the anti-elite mediators of our study continue to have a substantial, independent effect alongside the broader trust measures used by Huber et al. (Citation2021) This suggests that discontent towards climate policy is not just structured by political and societal trust, but also by specific climate-related anti-elite dispositions.

It is important to understand whether our findings are generalisable to other contexts. While our study examines opposition to climate action in the Netherlands, other recent studies suggest that our findings may be broadly applicable. Huber (Citation2020), for example, shows that populist citizens in the UK tend to reject the existence of anthropogenic climate change. Evidence from Jylhä and Hellmer (Citation2020) in Sweden shows that anti-establishment views are associated with climate change denial and pseudoscientific beliefs. Moreover, in a replication analysis we showed that our findings align with those of Huber et al. (Citation2021) in Austria: populist attitudes and views on climate change are mediated through attitudes towards science and institutional trust. In addition, the radical populist right throughout Europe is increasingly rejecting climate change (Farstad Citation2018; Forchtner et al. Citation2018; Żuk and Szulecki Citation2020).

Our article contributes to the study of climate policy opposition by examining overall, diffuse support/opposition for climate policy. This is important as previous research has shown that support for climate policies can hinge on the types of policies implemented (Drews and Van den Bergh Citation2016: 859). That said, future research would be well placed to examine how ideological disposition are relevant for explaining opposition against different kinds of climate policies. In addition, our study focussed on the effect of populist attitudes as well as the moderating role of left-right ideology. Yet, increasingly climate policy opposition is seen as being part and parcel of a broader cultural backlash. Future studies should therefore assess the importance of cultural attitudes and values for support for climate mitigation measures. Another promising venue for future research regards potential confounders related to emotional states and perceptions of well-being. We had no data on these characteristics, and it is useful to include them in future research to check whether the relationship between populist attitudes, the three mediating factors and opposition to climate mitigation policy changes when including such factors.

Our findings have important implications for policymakers pursuing climate change mitigation policies. They suggest that policymakers should directly address anti-elite sentiments related to scientists and politicians to ensure the effectiveness and legitimacy of climate action. In other words, policymakers and scientists must develop a communication strategy that highlights the people behind climate research and explains how they draw their conclusions in an accessible manner. If climate scientists continue to be perceived as distant elites, citizens are unlikely to embrace their findings.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (420.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editors of West European Politics and the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback. We would also like to thank Bruno Castanho Silva, Alberto Stefanelli, and Andrej Zaslove for their comments. This paper was presented at the seminar of the Radboud Centre for Sustainability Challenges network in November 2021. We would like to thank all participants for their feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maurits J. Meijers

Maurits J. Meijers is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Radboud University Nijmegen. His research focuses on public opinion, political representation, and party competition. His work has been published in The Journal of Politics, European Journal of Political Research, Comparative Political Studies and Journal of European Public Policy, amongst other outlets. [[email protected]]

Yaël van Drunen

Yaël van Drunen is a doctoral candidate at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel and Radboud University Nijmegen. Her main research interest lies in political sociology, with special attention to questions pertaining to political attitudes, polarisation and social cleavages. Her previous work has been published in Social Indicators Research. [[email protected]]

Kristof Jacobs

Kristof Jacobs is Associate Professor at the Department of Empirical Political Science, Radboud University Nijmegen. He has specialised in populism, democratic innovations and democratic challenges. His articles have appeared in journals such as European Journal of Political Research, British Journal of Political Science, Political Behaviour and West European Politics. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 Whenever we use the word ‘effect’ in this article we do use it in the conventional statistical sense, and do not imply to make bold causal claims.

2 For ease of formulation, we refer to populist attitudes in a binary way. However, empirically, we conceptualize and measure populist attitudes as a latent construct in a continuous dimension, ranging from low populist attitudes to high populist attitudes (cf. method section).

3 In a similar vein, Guinjoan (Citation2022) has shown that individuals’ left-right position moderates the relationship between populist attitudes and preferences for minority rights and civil liberties.

4 Replication data for this study is available at Meijers, Maurits; van Drunen, Yaël; Jacobs, Kristof, 2022, "Replication Data for: It’s a Hoax! The Mediating Factors of Populist Climate Policy Opposition", https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HVX2DV, Harvard Dataverse.

5 Tweede Kamer, Algemene Politieke Beschouwingen, 22 September 2021: 2–51: https://www.tweedekamer.nl/downloads/document?id=92a288b2-a10c-44f3-8bdc-f45f159a0272andtitle = Algemene%20Politieke%20Beschouwingen.pdf (accessed December 16, 2021).

6 CBS gender, age, and income are calculated for the whole population; CBS education data is only calculated for individuals aged 15 and above. Our dataset does not include any individuals below 18 years of age.

7 A correlation matrix in online appendix B shows that two of the constitutive variables (POP5 and POP6) of the latent populist attitudes variable correlate moderately with the ‘political gain’ variable. This is not surprising as all three variables address a form of discontent with political elites.

8 We do not rely on the chi-square statistic to assess model fit due to its sensitivity to sample size, as we work with a large sample (N = 1133) (Kline Citation2011).

9 In line with the previous literature, we also find we find that the more right wing people are, the more they are opposed to climate policies (McCright and Dunlap Citation2011; Poortinga et al. Citation2019). The control variables (see online appendix C M1) indicate that older people and those who are less educated are more opposed to climate policies.

10 We can speculate that this finding is insignificant because individuals with pro-climate policy attitudes believe that some groups, such as the fossil fuel industry, benefit from the current lack of climate change mitigation policies.

11 If we relax the threshold of statistical significance to p < 0.1, the result even becomes statistically significant.

12 We assess institutional trust with measures that gauge trust in government, parliament, the media, the legal system, and the European Parliament (0–10; no trust–full trust). We assess trust in science with a single item on a 0–10 scale (no trust–full trust). The measurement model for the latent construct of institutional trust shows a good model fit (see online appendix D).

References

- Akkerman, Agnes, Cas Mudde, and Andrej Zaslove (2014). ‘How Populist Are the People? Measuring Populist Attitudes in Voters’, Comparative Political Studies, 47:9, 1324–53.

- Cann, Heather W., and Leigh Raymond (2018). ‘Does Climate Denialism Still Matter? The Prevalence of Alternative Frames in Opposition to Climate Policy’, Environmental Politics, 27:3, 433–54.

- Caramani, Daniele (2017). ‘Will vs. Reason: The Populist and Technocratic Forms of Political Representation and Their Critique to Party Government’, American Political Science Review, 111:1, 54–67.

- Castanho Silva, Bruno, Ioannis Andreadis, Eva Anduiza, Nebojsa Blanusa, Yazmin M. Corti, Gisela Delfino, Guillem Rico, Saskia P. Ruth-Lovell, Bram Spruyt, Marco R. Steenbergen, and Levente Littvay (2018). ‘Public Opinion Surveys: A New Scale’, in Kirk A. Hawkins, Ryan Carlin, Levente Littvay, and Cristobal Rovira Kaltwasser (eds.), The Ideational Approach to Populism: Concept, Theory, and Analysis. Abingdon: Routledge, 150–78.

- Castanho Silva, Bruno, Federico Vegetti, and Levente Littvay (2017). ‘The Elite is up to Something: Exploring the Relation between Populism and Belief in Conspiracy Theories’, Swiss Political Science Review, 23:4, 423–43.

- Drews, Stefan, and Jeroen C. Van den Bergh (2016). ‘What Explains Public Support for Climate Policies? A Review of Empirical and Experimental Studies’, Climate Policy, 16:7, 855–76.

- Easton, David (1975). ‘A Re-Assessment of the Concept of Political Support’, British Journal of Political Science, 5:4, 435–57. 10.1017/S0007123400008309

- Farstad, Fay M (2018). ‘What Explains Variation in Parties’ Climate Change Salience?’, Party Politics, 24:6, 6, 698–707.

- Forchtner, Bernhard, Andreas Kroneder, and David Wetzel (2018). ‘Being Skeptical? Exploring Far-Right Climate-Change Communication in Germany’, Environmental Communication, 12:5, 589–604.

- Fraune, Cornelia, and Michèle Knodt (2018). ‘Sustainable Energy Transformations in an Age of Populism, Post-Truth Politics and Local Resistance’, Energy Research & Social Science, 43, 1–7.

- Geurkink, Bram, Andrej Zaslove, Roderik Sluiter, and Kristof Jacobs (2020). ‘Populist Attitudes, Political Trust, and External Political Efficacy: Old Wine in New Bottles?’, Political Studies, 68:1, 247–67.

- Guinjoan, Marc (2022). ‘How Ideology Shapes the Relationship between Populist Attitudes and Support for Liberal Democratic Values. Evidence from Spain’, Acta Politica. doi:10.1057/s41269-022-00252-9.

- Hammar, Henrik, and Sverker C. Jagers (2006). ‘Can Trust in Politicians Explain Individuals’ Support for Climate Policy? The Case of CO2 Tax’, Climate Policy, 5:6, 613–25.

- Harring, Niklas, Sverker C. Jagers, and Simon Matti (2019). ‘The Significance of Political Culture, Economic Context and Instrument Type for Climate Policy Support: A Cross-National Study’, Climate Policy, 19:5, 636–50.

- Harring, Niklas, and Jacob Sohlberg (2017). ‘The Varying Effects of Left–Right Ideology on Support for the Environment: Evidence from a Swedish Survey Experiment’, Environmental Politics, 26:2, 278–300.

- Hawkins, Kirk A., and Cristobal Rovira Kaltwasser (2018). ‘Introduction. The Ideational Approach’, in Kirk A. Hawkins, Ryan Carlin, Levente Littvay, and Cristobal Rovira Kaltwasser (eds.), The Ideational Approach to Populism: Concept, Theory, and Analysis, Abingdon: Routledge, 1–24.

- Hornsey, Matthew J., Emily A. Harris, Paul G. Bain, and Kelly S. Fielding (2016). ‘Meta-Analyses of the Determinants and Outcomes of Belief in Climate Change’, Nature Climate Change, 6:6, 622–6.

- Howe, Peter D., Jennifer R. Marlon, Matto Mildenberger, and Brittany S. Shield (2019). ‘How Will Climate Change Shape Climate Opinion?’, Environmental Research Letters, 14:11, 113001.

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler (1999). ‘Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives’, Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6:1, 1–55.

- Huber, Robert A (2020). ‘The Role of Populist Attitudes in Explaining Climate Change Skepticism and Support for Environmental Protection’, Environmental Politics, 29:6, 959–82.

- Huber, Robert A., Lukas Fesenfeld, and Thomas Bernauer (2020). ‘Political Populism, Responsiveness, and Public Support for Climate Mitigation’, Climate Policy, 20:3, 373–86.

- Huber, Robert A., Esther Greussing, and Jakob-Moritz Eberl (2021). ‘From Populism to Climate Scepticism: The Role of Institutional Trust and Attitudes towards Science’, Environmental Politics, 1–24.

- Jylhä, Kirsti M., and Kahl Hellmer (2020). ‘Right‐Wing Populism and Climate Change Denial: The Roles of Exclusionary and anti‐Egalitarian Preferences, Conservative Ideology, and Antiestablishment Attitudes’, Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 20:1, 315–35.

- Kim, Junghwa, Jan-Dirk Schmöcker, Satoshi Fujii, and Robert B. Noland (2013). ‘Attitudes towards Road Pricing and Environmental Taxation among US and UK Students’, Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 48, 50–62.

- Kline, Rex B. (2011). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (3rd ed). New York City: Guilford Press.

- Lewandowsky, Stephan, Giles E. Gignac, and Klaus Oberauer (2013). ‘The Role of Conspiracist Ideation and Worldviews in Predicting Rejection of Science’, PLoS One, 8:10, e75637.

- Lockwood, Matthew. (2018). ‘Right-Wing Populism and the Climate Change Agenda: Exploring the Linkages’, Environmental Politics, 27:4, 712–32.

- Marcos-Marne, Hugo, Gil de Zúñiga Homero, and Porismita Borah (2022). ‘What Do we (Not) Know about Demand-Side Populism? A Systematic Literature Review on Populist Attitudes’, European Political Science, 1–15. doi:10.1057/s41304-022-00397-3.

- McCright, Aaron M., and Riley E. Dunlap (2011). ‘The Politicization of Climate Change and Polarization in the American Public’s Views of Global Warming, 2001–2010’, The Sociological Quarterly, 52:2, 155–94.

- McCright, Aaron M., Sandra T. Marquart-Pyatt, Rachael L. Shwom, Steven R. Brechin, and Summer Allen (2016). ‘Ideology, Capitalism, and Climate: Explaining Public Views about Climate Change in the United States’, Energy Research & Social Science, 21, 180–9.

- Meijers, Maurits J., and Andrej Zaslove (2021). ‘Measuring Populism in Political Parties: Appraisal of a New Approach’, Comparative Political Studies, 54:2, 372–407.

- Mudde, Cas (2004). ‘The Populist Zeitgeist’, Government and Opposition, 39:4, 541–63.

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristobal Rovira Kaltwasser (2017). Populism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pidgeon, Nick (2012). ‘Public Understanding of, and Attitudes to, Climate Change: UK and International Perspectives and Policy’, Climate Policy, 12:sup01, S85–S106.

- Poortinga, Wouter, Whitmarsh Lorraine, Linda Steg, Gisela Böhm, and Stephen Fisher (2019). ‘Climate Change Perceptions and Their Individual-Level Determinants: A Cross-European Analysis’, Global Environmental Change, 55, 25–35.

- Rico, Guillem, Marc Guinjoan, and Eva Anduiza (2020). ‘Empowered and Enraged: Political Efficacy, Anger and Support for Populism in Europe’, European Journal of Political Research, 59:4, 797–816.

- Rosseel, Yves (2012). ‘Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling’, Journal of Statistical Software, 48:2, 1–36.

- Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristobal, and Steven M. Van Hauwaert (2020). ‘The Populist Citizen: Empirical Evidence from Europe and Latin America’, European Political Science Review, 12:1, 1–18.

- Spruyt, Bram, Gil Keppens, and Filip Van Droogenbroeck (2016). ‘Who Supports Populism and What Attracts People to It’, Political Research Quarterly, 69:2, 335–46.

- Stecula, Dominik A., and Eric Merkley (2019). ‘Framing Climate Change: Economics, Ideology, and Uncertainty in American News Media Content from 1988 to 2014’, Frontiers in Communication, 4, 6. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2019.00006.

- Stoutenborough, James W., Rebecca Bromley-Trujillo, and Arnold Vedlitz (2014). ‘Public Support for Climate Change Policy: Consistency in the Influence of Values and Attitudes over Time and across Specific Policy Alternatives’, Review of Policy Research, 31:6, 555–83.

- Uscinski, Joseph E., and Santiago Olivella (2017). ‘The Conditional Effect of Conspiracy Thinking on Attitudes toward Climate Change’, Research and Politics, 4:4, 1–9.

- Van Rensburg, Willem (2015). ‘Climate Change Scepticism: A Conceptual Re-Evaluation’, SAGE Open, 5:2, 215824401557972–13.

- Van Hauwaert, Steven M., and Stijn Van Kessel (2018). ‘Protest and Discontent: A Cross-National Analysis of the Effect of Populist Attitudes and Issue Positions on Populist Party Support: Beyond Protest and Discontent’, European Journal of Political Research, 57:1, 68–92. Beyond

- Whitmarsh, Lorraine (2011). ‘Scepticism and Uncertainty about Climate Change: Dimensions, Determinants and Change over Time’, Global Environmental Change, 21:2, 690–700.

- Zaslove, Andrej, Bram Geurkink, Kristof Jacobs, and Agnes Akkerman (2021). ‘Power to the People? Populism, Democracy, and Political Participation: A Citizen’s Perspective’, West European Politics, 44:4, 727–51.

- Ziegler, Andreas (2017). ‘Political Orientation, Environmental Values, and Climate Change Beliefs and Attitudes: An Empirical Cross-Country Analysis’, Energy Economics, 63, 144–53.

- Żuk, Piotr, and Kacper Szulecki (2020). ‘Unpacking the Right-Populist Threat to Climate Action: Poland’s Pro-Governmental Media on Energy Transition and Climate Change’, Energy Research & Social Science, 66, 101485.