Abstract

Governments increasingly apply collaborative governance based on deliberation that typically takes place in non-majoritarian institutions. However, collaborative institutions face accountability challenges depending on their institutional design. Still, empirical research is missing on the different choices member states make when designing collaborative institutions implementing European Union (EU) political goals. Using four theoretical principles of accountability, the study compares how Finland and Sweden implement the requirements for collaborative governance of two EU directives in national legislation and management plans. While Finland has provided more detailed and stricter rules resulting in higher process accountability, Sweden has delegated final decision making to authorities, achieving a higher degree of institutional independence. The results reveal that since the directives set only some of the key rules and procedures needed for achieving accountable collaborative institutions, member states’ discretion can lead to institutional variation even in similar governance contexts, resulting in differing institutional accountability and legitimacy of EU policies.

Responsibility for the outcomes of decisions in representative democracy is traditionally attributed to politicians who are held accountable through regular elections. Non-majoritarian institutions, however, are comprised of non-elected representatives authorised within a certain domain and not ‘directly managed by elected officials’ (Thatcher and Stone Sweet Citation2002: 2). The Europeanisation of national policies, and the national implementation of European Union (EU) legislation, has resulted in the increased delegation of decision making to non-majoritarian institutions (Majone Citation1999). Some of these institutions are established for enabling collaborative governance. Due to its potential to increase the legitimacy and effectiveness of policies aimed at addressing ‘wicked societal problems’ (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015), collaborative governance is promoted from the top-down by international conventions and EU legislation (Batory and Svensson Citation2020; Eckerberg and Bjärstig Citation2020; Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015). The enhanced legitimacy stems from the deliberative nature of collaborative governance, where decisions are based on deliberation and consensus between a broad array of actors with different and even conflicting interests (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015; Hysing Citation2022). Collaborative governance decisions are thus less likely to be contested at a later stage (Brisbois and de Loë Citation2016), making them more effective, especially if resources are invested in deliberation and a wide range of interests is represented (Biddle 2017; Dressel et al. Citation2020). The effectiveness of collaborative governance is further attributed to its potential to provide interaction between actors across policy sectors and levels of government – an interplay that is seen as key for achieving ambitious political goals (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015; Hysing Citation2022).

This notwithstanding, collaborative governance and its policy outcomes receive equal criticism for their low accountability and legitimacy. This is due to the unclarity in decision-making responsibilities, as well as the symbolic inclusion, exclusion, or even marginalisation of certain actors from the collaborative governance process by limiting their influence on agenda-setting and decision making (Brisbois and de Loë Citation2016; Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015; Kallis et al. Citation2009; Purdy Citation2012). Accountability is especially difficult to trace in collaborative institutions since they can involve a multitude of actors in decision making, including non-governmental actors (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015). Moreover, they are usually established outside of the principal institutions of government and therefore outside the reach of the traditional mechanisms of democratic accountability (Skelcher Citation2000). Given that accountability is a key dimension of legitimacy, the decisions made by collaborative institutions can therefore lack legitimacy (Kronsell and Bäckstrand Citation2010).

As with non-majoritarian institutions (Majone Citation1999), the accountability challenges that collaborative governance faces can be addressed through institutional design (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015). However, institutional design (Majone Citation1999; Martinsen and Vollaard Citation2014) and approaches to the legal and practical implementation of EU policies (Princen et al., Citation2022; Treib Citation2014; Zhelyazkova and Thomann Citation2022) vary between EU member states, resulting in ‘differentiated implementation’ – a diversity of policy choices and outcomes (Fink and Ruffing Citation2017; Thomann and Sager Citation2017; Zhelyazkova and Thomann Citation2022). Despite research focusing on member states’ implementation and the attainment of EU policy goals (Bondarouk et al. Citation2020; Martinsen and Vollaard Citation2014; Zhelyazkova et al. Citation2016), less attention has been paid to this diversity of policy choices and solutions (Thomann and Sager Citation2017) and the differentiation in the legal and practical implementation of EU policies (Zhelyazkova and Thomann Citation2022), including through the establishment of varying governance structures and decision-making procedures. Moreover, although the ‘legal framework helps shape collaborative governance’ (Amsler Citation2016: 709), collaborative governance scholarship has rarely focused on it (Batory and Svensson Citation2020) and knowledge regarding how states can design accountable collaborative institutions through the implementation of top-down policy is lacking.

Our explorative study aims at addressing these research gaps by comparing both the different institutional choices made by two member states in the transposition and implementation of two EU directives and the accountability of the resulting collaborative institutions. The study thus contributes to this special issue by investigating empirically the varieties of governance structures in differentiated EU policy implementation and the consequences they have on the legitimacy of these policies (Zhelyazkova et al. Citation2023). Our analysis of differentiated implementation is based on the concept of ‘customisation’, or member states’ interpretation and adaptation of EU policies in the process of implementation (Fink and Ruffing Citation2017; Zhelyazkova and Thomann Citation2022). Since the accountability of institutions depends on their design (Amsler Citation2016; Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015; Majone Citation1999), we focus on ‘customised restrictiveness’ in the rules establishing collaborative institutions, or ‘how domestic rules differ from the EU legislation in content’ (Zhelyazkova and Thomann Citation2022: 4, emphasis in original). In our comparison, we explore whether one of the two member states ‘restricts the behaviour of target groups’ (Zhelyazkova and Thomann Citation2022: 4) more than the other by enacting requirements for the design of collaborative institutions that are more detailed and stricter than those stipulated by the two EU directives, resulting in more accountable collaborative institutions. By combining theories on non-majoritarian (Majone Citation1999) and collaborative (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015; Sabatier et al. Citation2005) institutions, we derive four principles deemed as crucial for designing accountable institutions. These are as follows: 1) authorisation of institutions enabling joint action across sectors and levels through the delegation of decision making; 2) process rules for participation and ex-ante control; 3) rules and procedures for ex-post control; and 4) institutions allowing continuity.

In our analysis, we focus on policy documents at three institutional levels – the supranational (EU directives), and the national (national laws, decrees) and subnational (marine strategies and river basin management plans) in Finland and Sweden. Our results indicate that Finland has applied a higher level of customised restrictiveness in relation to the design of collaborative institutions and jointly implemented the two directives through legislation governing the political goals of both, indicating a higher degree of process accountability and policy cohesion. Sweden, on the other hand, has made the implementation of EU policy goals more independent from political interference by delegating final decision making to semi-autonomous governmental agencies and expert groups. This differentiated implementation of EU policies underlines the important role that top-down legal frameworks play in enabling or limiting member states’ discretion in institutional design, resulting in different governance structures and decision-making procedures with varying degrees of accountability, and consequently, policy legitimacy. Our findings further demonstrate the usefulness of applying the principles of accountability of non-majoritarian institutions to the analysis of collaborative institutions.

Designing accountable institutions for collaborative governance

Analysing the accountability of collaborative institutions requires us to first define collaborative governance and then lay out the four theoretical principles of institutional design that foster accountability (the summary of the four principles A-D and their sub-categories is presented in ). We define collaborative governance the same as Emerson et al. (Citation2012: 2), i.e. as ‘the processes and structures of public policy decision making and management that engage people constructively across the boundaries of public agencies, levels of government, and/or the public, private and civic spheres in order to carry out a public purpose that could not otherwise be accomplished.’ Accordingly, collaborative governance is cross-sectoral in two ways: in terms of allowing interaction between different policy arenas, as well as between governmental and non-governmental actors (Berardo et al. Citation2020; Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015; Fischer and Sciarini Citation2016; Lubell et al. Citation2010).

Table 1. Four key principles for designing accountable collaborative institutions (A, B, C, D) together with related coding categories and codes, derived from Majone (Citation1999), Emerson et al. (Citation2012); Lubell et al. (Citation2010); Fischer and Sciarini (Citation2016); Metz et al. (Citation2020) and Ulibarri et al. (Citation2020).

The general principles of accountable non-majoritarian institutions (Majone Citation1999) apply also to collaborative institutions, with some specifics related to the latter’s deliberative nature. We focus here on four such principles. First, if their accountability is to be of importance (Majone Citation1999; Thatcher and Stone Sweet 2002), collaborative institutions must be authorised and delegated decision-making power, or at least have actual influence on decision making (Hysing Citation2022; Purdy Citation2012). However, since they are collaborative and rely on integration with other policy-making processes (Koontz and Newig Citation2014), these institutions should be authorised to function as arenas for the participation of actors across sectors and levels, allowing these different sectors and levels to influence planning, decision making and implementation (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015; Fischer and Sciarini Citation2016). The authorisation of this sort of interaction can be deliberate, through the creation of ‘institutional opportunity structures’ (Fischer and Sciarini Citation2016: 65), or established ‘ad-hoc’, as we refer to them, by authorities or other actors. Deliberate collaborative institutions are typically established by legislation that requires interaction across policy arenas in institutional structures, while ad-hoc collaborative institutions are created when the need for exchange across sectors to achieve a certain goal is recognised. However, the latter case requires one or more actors to take initiative and that kind of leadership is dependent on their resources (Metz et al. Citation2020). This makes the establishment of ad-hoc collaborative institutions less certain and less transparent than if established through legislation.

According to the second principle, collaborative institutions should have process rules and procedures guaranteeing that all relevant actors participate and influence decisions equally (Brisbois and de Loë Citation2016; Emerson et al. Citation2012; Hysing Citation2022; Purdy Citation2012); decision making is transparent; and decision-makers are held accountable through mechanisms for ex-ante control, just as in non-majoritarian institutions (Majone Citation1999; Thatcher and Stone Sweet 2002). Participation is a multidimensional concept and inclusion can be limited to a few governmental actors or open to the public (Trachtenberg and Focht Citation2005). Diversified actor participation in collaborative institutions can lead to more legitimate decisions, but also generate conflict and undermine the collaborative process (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015). Nevertheless, collaborative governance aiming to foster interaction across policy sectors and governmental levels should at least include actors representing different policy arenas and levels. Clear rules about who is included and how lead to transparency regarding who is responsible for the outcomes of the decisions made (Amsler Citation2016; Sabatier et al. Citation2005). Process rules determine the varying degrees of information exchange and knowledge production: from information supply (one-way information), through consultation (two-way information), to active involvement (Newig et al. Citation2014), which leads to joint knowledge production and increased trust (Emerson et al. Citation2012; Fischer and Sciarini Citation2016). The exchange of two-way information in the form of consultations and peer-review increases transparency by allowing the public to influence planning and decision making. Moreover, peer-review that requires decision-makers to address the received feedback and give reasons for decisions allows for ex-ante control and improves accountability (Majone Citation1999; Thatcher and Stone Sweet 2002). Ex-ante control can also be exercised by political leaders through procedures that allow them to review and stop decisions if they are against public interests. The option of overruling draft decisions ‘should be neither too easy nor too difficult’, as the former has a direct effect on the institution’s political independence and the latter on its accountability (Majone Citation1999: 15). This is especially relevant for collaborative governance since it requires the investment of significant resources from all participating actors (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015; Sabatier et al. Citation2005) and having too-easy-to-apply mechanisms for the review of draft decisions could make collaboration futile and the institutions meaningless. Ex-ante control is therefore a balancing act: peer-review and requiring reasoning for decisions keeps decision-makers accountable, but overly simple procedures for governmental intervention and overruling of draft-decisions places institutions under the direct influence of the government (Thatcher and Stone Sweet 2002).

The third principle in question, mechanisms for ex-post control, concerns allowing elected officials or other actors to intervene after the decisions have been made if they conflict with public interests or politically prioritised goals. These mechanisms are important for holding non-majoritarian institutions accountable (Majone Citation1999), and depend on the extent of the delegation of decision-making power (Thatcher and Stone Sweet 2002). Since these conflicts might not be immediately apparent, political leaders can set formal procedures requiring reporting and evaluation (Miljand and Eckerberg Citation2022) of both the collaborative process (e.g. if it was inclusive and fair), as well as any related decisions and their social and environmental outcomes (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015). As with ex-ante interventions, the procedures for the ex-post overruling of decisions should, for transparency reasons, be clearly defined and not overly easy, ensuring the institution’s independence (Majone Citation1999). Given member states’ differentiated approaches to implementation (Fink and Ruffing Citation2017), this independence is likely to vary according to the extent of delegation and the mechanisms of ex-ante and ex-post control that are put in place (Majone Citation1999; Thatcher and Stone Sweet 2002).

Finally, the fourth principle is that most of the procedures and mechanisms for ex-ante and ex-post control require that collaborative institutions function under a longer time-period. Providing an institution with the means to function continuously and build trust between participants is an important precondition for cross-sectoral interactions to be considered as collaborative (Sabatier et al. Citation2005; Ulibarri et al. Citation2020). Moreover, long-term collaboration, or continuity, allows for the review and evaluation of the decisions made, and for collaboration to be ‘adapted’ and re-designed accordingly (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015).

To sum up, a collaborative institution should be designed in a manner that facilitates interactions across policy sectors and governmental levels with the aim of influencing decisions. It should thus be authorised to an extent that allows it to have an actual influence on planning and decision making. Clear process rules specifying who should participate in collaboration and how, requiring two-way information exchange, peer-review and reasoning on behalf of decision-makers, and thus allowing for the ex-ante control of decisions without crippling their independence, can foster accountable collaborative institutions. Mechanisms for ex-post control such as reporting allow elected leaders and the public to monitor the outcomes and intervene through appeal if public interests are threatened. Finally, continuous, or long-term collaborative institutions can be held accountable for their decisions and adapted as needed.

The analysis of the design of collaborative institutions for implementing political goals requires defining what aspects of implementation are included and why. In this study, we refer to implementation as the policy and institutional changes that take place during the transposition of EU legislation into national law (Treib Citation2014) and its adaptation to domestic circumstances and political preferences through ‘customisation’ (Zhelyazkova and Thomann Citation2022). Our analysis focuses specifically on the choice of establishing different decision-making procedures and governance structures facilitating interactions between actors and institutions, since that choice depends on political and administrative contextual factors and affects the outcomes of policy implementation (Martinsen and Vollaard Citation2014; Sager Citation2009; Thomann and Sager Citation2017). We focus on the ‘intermediate outcomes’ that come in-between the formulation of a policy and the achievement of its aims (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015). That includes both the transposition of EU legislation into national legislation, as well as its further implementation through management plans. Our analysis does not consider implementation in practice, or the ‘actions’ that follow once the formal policies (laws, rules, governance structures and plans) are put in place (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015; Zhelyazkova and Thomann Citation2022), since they do not depend only on institutional design but also on actors’ willingness and ability (Ostrom Citation2005).

Research design and materials

We designed the study as an embedded comparative case (Yin Citation2014), where we compare the implementation of two EU directives in two EU member states. The directives are the Water Framework Directive (WFD) and the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD). We chose water policy due to its cross-cutting role in societies, its linkages to several other sectors, and implementation, which does not typically coincide with administrative boundaries, making it a particularly suitable resource to focus on when investigating collaborative governance (Smajgl et al. Citation2016). We focus on the WFD and the MSFD for several reasons. First, the MSFD widens the scope of the WFD on inland and coastal water by including sea areas in EU water policy (Mee et al. Citation2008). Further, due to the interlinkages between human activities at different levels, as well as between the state of inland waters and the state of the sea (Borja et al. Citation2010), the two directives require not only coordination and cooperation across levels, sectors and states but also a coordination of implementation efforts if, their overarching goals are to be achieved. Finally, public participation (cf. with ‘mandated participatory planning’ in Newig and Koontz Citation2014), and cooperation and coordination across sectors, levels and states (Art. 3, 11, 12, and 14 of WFD; Preamble 13, 16, Art. 3, 5, 6, 7 of MSFD) are among the substantive requirements of the directives, indicating that collaborative governance institutions provide a feasible way for their implementation. Exploring whether one of the two member states has enacted more restrictive rules (than those stipulated by the EU directives, and in comparison) with respect to how collaborative institutions should be designed can help shed light on how differentiated implementation can result in accountable decision making within the EU.

Finland and Sweden were chosen for the comparative analysis because of their contextual similarities in terms of both environmental and governance aspects. Regarding the latter, both states joined the EU simultaneously and are characterised by decentralised political systems and a governance tradition of collaborative decision making with the participation of non-governmental actors (Laegreid Citation2017). Furthermore, the preparation of their national marine strategies (for the Baltic Sea) is coordinated within the framework of the Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission (HELCOM). These similar governance and environmental contexts limit some of the factors that could affect implementation (Ostrom Citation2005; Sabatier et al. Citation2005).

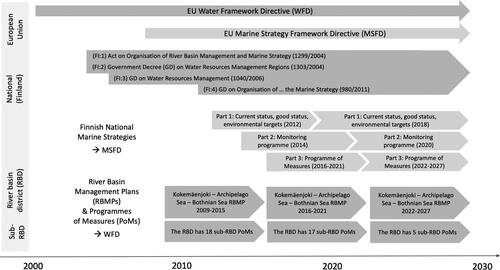

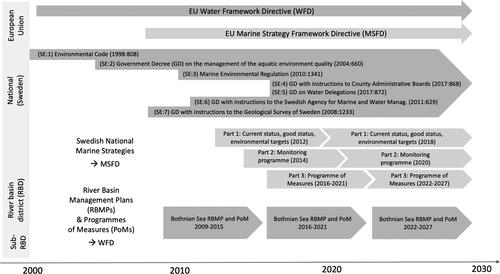

We analysed the national legislation transposing the WFD and MSFD in Finland and Sweden, as well as the official policy documents that further implement the directives in the form of national marine strategies (NMSs), and river basin management plans and programmes of measures (hereafter RBMPs) from one river basin district in each country (see and and Table A in the Online appendix for a detailed summary of the documents and selection criteria). To account for change over time, we analysed all management cycles that have occurred since the enactment of the two directives: three for the WFD and two for the MSFD.

We chose to focus on official policy documents for three reasons. First, policy documents provide the legal framework and thus determine the institutional design, opportunities and hinders for decision making (Ostrom, Citation2005), as well as the accountability (Majone Citation1999) of collaborative institutions (Amsler Citation2016; Hysing Citation2022). Focusing on both EU and member states’ policy documents allows for the inclusion of both top-down (EU) and bottom-up (member state) dimensions of implementation (Heidbreder Citation2017). Second, we are looking for differences in the level of restrictiveness of the rules that design collaborative institutions: that is, if one state applies more detailed and stricter rules in policy documents. This comparison explores how implementation differs from the substantive requirements of the directives, as well as between the two member states. Since cross-sectoral interaction that is not mandated by legislation is dependent on authorities’ initiation and leadership (Metz et al. Citation2020), and leadership alone is not a guarantee for the initiation of collaboration (Emerson et al. Citation2012), the absence of EU (top-down) or national (bottom-up) policy mandating collaboration results in a high degree of uncertainty concerning whether collaborative governance will be initiated and maintained. Finally, analysing policy texts, as opposed to interviewing or surveying actors engaged in the institutions, limits the risk for the potential interpretation bias of implementors and process participants (Sabatier et al. Citation2005).

Based on the four theoretically derived principles of institutional design fostering accountability in collaborative institutions (A-D), we defined a set of related coding categories and specific codes for each of them (). We used the same term in Finnish and Swedish translations for our searches (see Table B in Online Appendix). We then coded the EU and national documents in the qualitative data analysis software Atlas.ti and extracted tables of codes and coded texts. We read through the tables for each analytical unit (the EU directives, Finnish, and Swedish documents) separately, removed repetitive texts and summarised the results according to each theoretical category. Using tables with the same theoretical principles and coding categories, we compared and synthesised the results for the two countries in three rounds and in reference to the results derived from the two EU directives in order to obtain the summarised results for each country. The results from the country-comparative analysis are presented as a synthesis in the next section and in (see the Online Appendix for the detailed reports).

Table 2. A summary of how the EU Directives have prescribed, and how Finland and Sweden have implemented, the four theoretical principles.

Differentiated implementation in designing accountable collaborative governance institutions

This chapter first provides a short introduction to the implementation of the two EU directives in Finland and Sweden and then presents the key results from our analysis, structured according to the four principles described above. In Finland, the WFD and the MSFD were transposed through the adoption of new legislation: the Act on the Organisation of River Basin Management and the Marine Strategy (FI:1) and three related government decrees that give more detailed provisions (FI:2; FI:3; FI:4). The legislation assigns responsibilities and tasks to relevant governmental actors across sectors and levels in the organisation of river basin management and marine management. The Ministry of the Environment (MoE) and the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MoAF) are given the overall responsibility for implementation and coordination, while the local-regional cross-sectoral Centres for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment (ELY-Centres) are identified as the main authorities preparing the RBMPs for the seven mainland River Basin Districts (RBDs). However, the administrative borders of the ELY-Centres do not match the RBD borders, requiring coordination between the ELY-Centres. In our RBD case, for example, the RBMPs were prepared jointly by five ELY-Centres. The legislation stipulates the establishment of a steering group in each RBD to coordinate the preparation. The MoE is responsible for drawing up the NMS in collaboration with the Finnish Environment Institute and the ELY-Centres and in coordination with the MoAF and the Ministry of Transport and Communications. The RBMPs and NMSs are finally approved by the government and may be appealed ex-post as such.

In Sweden, the WFD and the MSFD were transposed through the revision of the overarching Swedish Environmental Act (SE:1), as well as through the enactment or revision of six decrees: one specifically for river basin management (SE:2), one specifically for marine management (SE:3) and four with instructions to authorities (SE:4, SE:5, SE:6, SE:7). While the management of marine waters is structured according to two sea regions, river basins are managed in five water districts (comparable to the Finnish RBDs) that do not correspond to regional administrative territories. The implementation of both marine and river basin management is coordinated by semi-autonomous (in relation to the government) governmental agencies (see Jacobsson and Sundström Citation2007 on the relationship between the government and governmental agencies): the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management in collaboration with the Geological Survey of Sweden (responsible for the coordination of groundwater management). In river basin management, one of the local-regional cross-sectoral County Administrative Boards within each water district is assigned the role of Water Authority (cf. with Finnish steering groups at RBD level). While decision-making power for NMSs is delegated by national legislation to the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management, for RBMPs it is delegated to Water Delegations at the district level. They consist of government-appointed actors from various sectors, but they act as experts as opposed to representing these interests. The government holds the right to review their decisions ex-ante, but their final decisions cannot be appealed ex-post.

Authorisation of institutions enabling joint action

Since directives only set goals and the frame within which they are to be attained, states enjoy a large level of discretion when deciding on how to achieve them (Princen et al. Citation2022; Treib Citation2014). This holds true for both the WFD and the MSFD and their requirements regarding the authorisation of collaborative institutions. They outline the need for the establishment of institutions that enable cross-sectoral water management within the member states and the EU as well as with third countries, but without detailed requirements concerning how they should be designed. Both directives underline the importance of integrating water protection and management into all relevant policy areas and promoting cohesion between plans, measures and goals. The EU Commission is also granted a coordinative role in cases when member states identify issues hindering the attainment of the WFD goals and to ensure cohesion between plans and measures. The WFD requires a summary of the ‘institutional relationships established to ensure coordination’ (Annexe I, v and vi), while the MSFD requires a list of all authorities that are to be coordinated (Annexes II and VI). The MSFD refers to the institutions established for implementing the WFD as potential institutions for coordination and cooperation between countries in the MSFD implementation. The directives set requirements for initial assessments and the establishment of environmental objectives, monitoring programmes, management plans and programmes of measures for surface and groundwater and for marine waters, but there are no requirements regarding how decision making should be delegated and at what level.

The establishment of coordinating authorities is prescribed in both countries by national legislation. However, as seen in and , and , Finland and Sweden chose different approaches to the transposition and implementation of the directives and designing institutions for river basin and marine management. Finland transposed both the WFD and the MSFD into a single act (FI:1), providing a common synergistic framework for river basin and marine protection and allowing for implementation efforts and institutions to focus on the goals of both directives. Sweden transposed the directives by revising an overarching Environmental Act (SE:1) and enacting separate decrees specifically for river basin management and marine management (), largely detaching the implementation of the MSFD from that of the WFD. The achievement of the directives’ common policy goals in Sweden thus relies on authorities’ own initiative to coordinate actions and establish the necessary institutions. Moreover, such ad-hoc institutions are not held accountable by rules and procedures that stem from implementing legislation and management plans.

In Finland, two ministries were delegated the responsibility for coordinating the main act implementing both directives (the MoE and the MoAF), with the Ministry of Transport and Communications being formally instructed to participate in marine management. By transposing the two directives through a single act, and delegating responsibility to relevant ministries representing a broad set of policy sectors, Finland created what Fischer and Sciarini (Citation2016) call ‘opportunity structures’, making the implementation of the two directives cross-sectoral. In Sweden, the responsibility for the coordination of the WFD implementation was initially delegated to the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency for surface water and the Geological Survey of Sweden for groundwater. However, after the transposition of the MSFD, the newly established Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management that was to be responsible for MSFD implementation took over the responsibility for river basin management in WFD implementation. This agency is specifically geared towards water governance and therefore has a more limited sectoral focus than the previously responsible Environmental Protection Agency.

The restrictiveness of the rules for interaction between governmental levels also varies. In Finland, collaborative institutions are established across governmental levels, including the national, local-regional (RBD) and local (sub-RBD) levels, whereas in Sweden the bulk of cross-sectoral interaction is concentrated at the local-regional (RBD) level, where the collaborative institutions for WFD implementation are set-up. While in the Finnish case RBMPs are compilations of sub-RBD plans, formally integrating the local (sub-RBD) level in decision making, the less restrictive Swedish policy allows local-regional authorities to prepare sub-RBD plans ‘if needed’, although this is not a requirement (SE:2). The Finnish legislation and procedures implementing the directives are more restrictive than those in Sweden, offering more detail on what should be prepared in collaboration and by whom, even identifying specific actors that are to participate and be represented. This restrictiveness increases the transparency of the planning process making it easier to attribute responsibility to actors and hold them accountable.

The extent of the delegation of decision-making power, or the influence that collaborative institutions have on final decisions, determines whether the governance mode can be considered as collaborative or if the collaboration is only of symbolic value (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015; Hysing Citation2022; Purdy Citation2012). The collaborative institutions established in both Finland and Sweden in relation to the two EU directives have an undeniable influence on the planning and drafting of decisions. Regardless, both countries take different approaches in delegating responsibility for final decision making in river basin and marine management. In Finland, the responsibility for final decisions on both RBMPs and NMSs lies with the government. In Sweden, the final decisions on NMSs are made by the governmental Agency for Marine and Water Management. However, governmental agencies in Sweden due to the so-called ‘dualism’ principle (Jacobsson and Sundström Citation2007), although accountable to and steered by the government, are semi-autonomous compared to ministries in other parliamentary states, including Finland (Laegreid Citation2017). Moreover, final decision making for RBMPs in Sweden is assigned to Water Delegations, the government-appointed expert groups. Consequently, the ruling government in Finland has more formal influence on the final decisions for river basin and marine management than their counterpart in Sweden.

Process rules for participation and ex-ante control

The importance of participation and public consultation in the planning, decision making and implementation of RBMPs and NMSs is underlined by both directives. The WFD, known for promoting participation (Newig et al. Citation2014), sets stricter rules and timeframes for consultation, as well as requirements for the inclusion of summaries of the consultation feedback and corresponding changes to RBMPs (Art. 14, Annexe VII, WFD). The MSFD states that programmes of measures should include communication, stakeholder involvement and raising public awareness, without requirements for summaries of received feedback (Annexe VI, MSFD). While the MSFD places less emphasis on participation, it nevertheless underlines that all interested parties should be involved and consulted in the development of criteria and standards for good environmental status and ensured early and effective opportunities to participate in implementation.

Both Finland and Sweden have followed the requirements set by the directives and applied similar mechanisms for public participation and peer-review, thus providing opportunities for an ex-ante review of the proposed decisions. Summaries of feedback are required for the RBMPs but not for the NMSs, in line with the two respective directives. Public consultations are organised in both countries at several governmental levels during both the planning and decision-making phases. This allows for two-way information exchange, and active involvement and peer-review throughout the management cycles. Both Finland and Sweden require reasoning on behalf of decision-makers. However, the Finnish legislation, in contrast to the Swedish one, has not limited public participation to consultation and peer-review processes, which research has shown are mainly utilised by experts (Newig et al. Citation2014). The Finnish national legislation identifies specific actors responsible for preparing plans and decisions and coordinating collaboration across sectors and levels (FI:1; FI:2; FI:3; FI:4). It prescribes the establishment of deliberate collaborative institutions, i.e. cooperation groups, to facilitate participation of governmental and non-governmental actors in planning (FI:1; FI:2). It is thus more restrictive than the Swedish legislation, which underlines that Water Authorities should collaborate with state, municipal and ‘other’ actors but without specifying the particular groups of actors (apart from the coordinating authorities), or the fora for participation (SE:2; SE:4). A similar pattern is seen in the management plans, where Finnish RBMPs and NMSs identify specific governmental and non-governmental actors who are responsible for the implementation of measures. Our analysis over time indicates that the Swedish RBMPs and NMSs become more detailed with every additional cycle.

Ex-ante procedures for the review and control of proposed decisions can ensure that the interests of the public or political priorities are defended by elected representatives (Majone Citation1999), but they can also limit the discretion of institutions in decision making (Thatcher and Stone Sweet 2002). In Finland, where the ministries are involved in the preparation of final drafts that have undergone peer-review through procedures for public consultation, and the government makes the final decisions for both RBMPs and NMSs, there is no need for additional mechanisms for the ex-ante review of the draft decisions. However, there is also a risk for agreements achieved in the collaborative institutions to be toned-down by the government in the final decisions, making them more prone to political control. In Sweden, where final decisions for RBMPs are delegated to the government-appointed expert group, there are clear mechanisms for the government to review the drafts of RBMPs and overrule them. This review is not automatic but can be instigated by governmental and non-governmental actors (SE:2), ensuring that the outputs produced through collaboration are not easily discarded while also holding the institutions that have prepared the proposal and those deciding on it accountable. At the same time, final decisions are not made by the government, distancing to a degree the decision-making authorities from formal political control.

Rules and procedures for ex-post control

Both directives require member states to report to the Commission on the progress of implementation by sending in their programmes of measures and interim reports regarding the progress of their implementation. The Commission is also responsible for reporting on the overall progress of the WFD and the MSFD implementation in the EU. The directives set the monitoring and assessment frame for RBMPs and NMSs in six-year cycles. Since the requirements for reporting to the Commission are already given within the directives, they have been transposed by both states in a nearly identical manner.

Apart from reporting, among the important mechanisms for ex-post control at the state level is the possibility for appeal against decisions that are already made but may go against public interests or entail unanticipated consequences for other policy sectors (Majone Citation1999; Thatcher and Stone Sweet 2002). An ex-post appeal of the government’s final decisions is possible in Finland for both RBMPs and NMSs. In Sweden, the decisions on NMS follow the same logic of appeal as all governmental agency decisions. However, the Swedish legislation specifically stipulates that the decisions on the river basin programmes of measures, once made by the Water Delegation, cannot be appealed. This could in theory mean that there is a lack of ex-post control mechanisms that hold the government-appointed experts (who do not represent their sectors) accountable for their decisions. In practice, however, since they are government-appointed, the ultimate responsibility for their decisions lies with the government. Moreover, the rules structuring the processes for drafting the RBMPs, as well as the multiple steps of ex-ante review and control, mean that the decisions the Water Delegations make are extensively scrutinised and reviewed by both governmental authorities and the government itself.

Institutions allowing continuity

The directives do not contain any requirements regarding the duration of the institutions established for the implementation of the two directives. In both Finland and Sweden, there are deliberately established collaborative institutions at the local-regional (RBD) level, but also several collaborative institutions that were established ad-hoc by responsible authorities at different levels. In Finland, these include joint national coordination and follow-up groups for river basin and marine management (after the MSFD transposition), as well as the expert and working groups for marine management. Still, both the collaborative institutions prescribed by the legislation and those established ad-hoc were always set for the whole planning cycle and have persisted through planning cycles. In Sweden, the ad-hoc groups established at national level by authorities, although separate for river basin and marine management, have also endured and become long-term. Their primary aim is state-level coordination and collaboration, and they complement the few deliberately established collaborative institutions at local-regional level, namely the Water Authorities and the decision-making Water Delegation. Contrary to Finland, a large part of the collaboration at the local-regional (RBD) and local (sub-RBD) level that includes non-governmental actors is realised in the form of dialogues, briefings, consultations and projects that have not been formally prescribed by policy and are dependent on project financing, making them short-termed. According to theory, this limits the possibilities for knowledge production among participants, as well as for the adaptation of the collaborative institutions (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015). In Finland, where the requirements for collaborative governance in planning and the preparation of decisions was implemented more restrictively, the main structure and contents of the RBMPs and NMSs have hardly changed throughout the management cycles. In Sweden, where the requirements were implemented less restrictively, various changes can be observed in the structure and level of detail of RBMPs and NMSs.

Concluding discussion

Collaborative governance encompasses broad actor participation and deliberation and is therefore often the governance mode of choice for the implementation of political goals that affect and are affected by different levels and policy sectors. However, collaborative institutions are prone to power inequalities and thus require clear process rules and mechanisms that warrant accountability. By applying the principles for accountability of non-majoritarian institutions to collaborative governance theory, our study’s aim was to compare Finland and Sweden’s differentiated implementation of two EU directives through the customisation of the requirements for establishing collaborative institutions and investigate their accountability.

Our findings indicate, similarly to the results of Zhelyazkova and Thomann (Citation2022), that Finland has implemented the two directives through a higher than required level of restrictiveness of national level legislation and management plans, and more restrictively than Sweden. In our case, this restrictiveness is related to the rules for establishing collaborative institutions. As a consequence, the interactions across sectors and levels in Finland are defined in policy, leading to a clearer than in Sweden integration of governmental levels, including the local level, in the preparation of plans and decision making. The more restrictive instructions for collaborative governance in Finland, detailing who should participate and where, as well as delegating responsibilities to governmental and non-governmental actors, have resulted in not only what should be more accountable institutions but also what literature has defined as collaborative institutions with diverse actor representation (Brisbois and de Loë Citation2016; Emerson et al. Citation2012; Hysing Citation2022; Purdy Citation2012; Trachtenberg and Focht Citation2005). Since the inclusion of non-state actors in planning and implementation aims at increasing the legitimacy of EU policy (Newig and Koontz Citation2014), and accountability is a key dimension of legitimacy (Kronsell and Bäckstrand 2010), designing more transparent and accountable collaborative institutions for planning and decision making can help achieve that aim.

By choosing to transpose and implement the two directives through the same legislation (), the implementation efforts and the collaborative institutions in Finland can simultaneously consider the goals of both directives, enhancing cohesion. This has resulted in the establishment of institutional ‘opportunity structures’ for interaction across sectors and levels (Berardo et al. Citation2020; Fischer and Sciarini Citation2016), that foster lasting collaboration and consequently learning and adaptation (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015). Moreover, while Finland chose to delegate the overarching responsibility for the implementation of the two water directives to governmental authorities representing several policy sectors, Sweden delegated the responsibility for river basin and marine management to a specialised water authority with a relatively narrow sectoral focus. Consequently, Finland applies a cross-sectoral approach in the implementation of the two directives already at the national level. In Sweden, cross-sectoral interactions with other governmental authorities and municipalities lack the same ‘opportunity structures’ and rely on the authorities’ initiative, which previous research has shown can make the interactions less likely (Fischer and Sciarini Citation2016; Metz et al. Citation2020).

The less restrictive prescriptions of collaborative governance in Sweden, in combination with the limited number of lasting institutions, have led to a significant part of cross-sectoral interactions being realised in the form of temporary ad-hoc collaboration in projects. As previously underlined by research, this makes collaboration vulnerable to the presence or absence of initiatives from authorities (Metz et al. Citation2020) and prevents the long-term learning, control, and adaptation of the decisions made, as well as the collaborative institutions making them (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015; Sabatier et al. Citation2005; Ulibarri et al. Citation2020).

However, the findings of this study also show that, in Finland, the effects of collaboration during planning and the preparation of proposals might be dampened by the formal control that the government exercises on final decisions (see ). The less decision-making power is delegated to institutions, the less need there is to restrict them through ex-ante control mechanisms (Majone, Citation1999; Thatcher and Stone Sweet 2002). If final decisions are made by the government, then political leaders can review, and if deemed necessary, revise the decisions agreed upon through collaboration. While both member states have applied similar processes for public consultation and peer-review requiring reasoning for decisions, they differ in the extent of delegating final decision making. Sweden has delegated final decision making for marine management to a semi-autonomous governmental agency and river basin management to government-appointed experts. This is different from Finland, where final decision making for both river basin and marine management rests with the government. On the one hand, this means that although collaborative institutions are authorised in planning and in the preparation of decisions, the government may detract from the agreements made in the collaborative processes if they go against its political interests. In such cases, the decisions may not be considered as truly collaborative since the collaboration before final decisions may be of mostly symbolic value (Hysing Citation2022; Purdy Citation2012). Nevertheless, research has shown that even when final decisions are not made by the collaborative institutions that drafted them, they can still contribute to their content (Hysing Citation2022), and despite the government having the final say, Finnish RBMPs might reflect the collaborative planning and decision making to a much higher extent than the Swedish RBMPs.

On the other hand, the lesser extent of delegating decision making in Finland could mean that the accountability of the decisions made is higher, since the ultimate responsibility rests with the government that is held accountable through the mechanisms of parliamentarism. In Sweden, the responsibility for final decisions concerning river basin management is delegated to an expert group, but the rules outlining the processes for preparing decisions lack restrictiveness. It is thus less clear not only how collaborative these processes are in character, but also, despite the additional ex-ante control mechanisms in place, who bears the responsibility and should be held accountable for the decisions. The observed changes over time show that Swedish authorities may have recognised the need for more detailed and stricter provisions on how collaborative governance should be designed and carried out.

The possibilities for an appeal of final decisions also differ between the two states. While in Finland the final decisions are subject to appeal, Sweden has made an exception regarding decisions on river basin management and the ex-post review through an appeal is restricted. The consequences could be two-fold. On the one hand, final decisions are detached from political pressure, allowing the goals of the directives to be prioritised. On the other, elected representatives cannot intervene when public interests or other political goals are compromised, and this can increase the risk for value conflicts (Majone Citation1999). Nonetheless, both states are held accountable for the decisions they make by the mechanisms for ex-post control set at EU level.

Our findings show that despite seemingly similar governance characteristics, Finland and Sweden have applied differentiated approaches in transposing and implementing the two EU directives, resulting in governance structures with varying degrees of accountability and collaborative characteristics. The customised implementation through a higher level of restrictiveness in Finland has resulted in more transparent and accountable collaborative governance institutions, in terms of planning and decision-making processes, but less independent from the government in terms of final decisions. Sweden, on the other hand, has delegated final decision making to authorities, distancing it from political influence, since the semi-autonomous governmental agencies responsible for overall implementation are more politically independent than the Finnish ministries. These results point to the importance of both granting discretion and having clear rules and procedures governing planning and decision making to ensure accountability. Our findings therefore indicate that although governments have the tools to ensure greater transparency and accountability, designing accountable collaborative institutions is not simple. Indeed, as underlined by Thatcher and Stone Sweet (2002), a balance must be struck between delegating responsibility and ensuring independence, on the one hand, and limiting power to safeguard accountability on the other. Our results suggest that such a balancing act is by no means straightforward and might even be harder where collaborative institutions are concerned, whose very aim is decision making that reflects consensus between actors with differing interests, some non-governmental.

The study also has broader implications in terms of differentiated policy implementation in the EU and contributes empirical knowledge to this special issue (Zhelyazkova et al. Citation2023) concerning the consequences that the differentiated implementation of governance structures can have on the legitimacy of EU policies. These observed differences in implementation can partly be explained by the varying administrative traditions in the two countries. In Sweden, authorities are generally more independent from the formal influence of the government than in Finland – a tradition mirrored in the governance structures established when implementing EU policy. Thus, while Finland and Sweden share many similarities in terms of their governance and societal contexts, a detailed look into the implementation of the two EU directives reveals the room for manoeuvre that governments have when implementing EU legislation and the responsibility member states bear for the accountability of the governance structures they put in place. Further, this differentiated implementation of governance structures demonstrates the important role that top-down mandated legal frameworks and bottom-up state implementation play in collaborative governance by creating opportunity structures for collaboration, increasing or limiting states’ and actors’ discretion in institutional design, and, as a consequence, shaping the accountability and legitimacy of decision making. The latter outcome is especially important for EU policy making, given that, as underlined by Newig and Koontz (Citation2014), participatory approaches are mandated with the ambition of increasing democratic legitimacy. Future research focusing on implementation in practice should investigate whether the actions that follow from the decisions made by more accountable collaborative institutions also result in a higher degree of attainment of the EU political goals that the two directives are set out to accomplish.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (55.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Matilda Miljand for her thoughtful comments and suggestions, to Elsa Reimerson, and the ENRP research group at Umeå University. Previous versions of this manuscript have been presented at the 2021 ECPR Joint Sessions, SWEPSA 2021, and the ECPR 2021 General Conference. We would like to thank the participants and convenors for the feedback provided, as well as the editors and anonymous reviewers for their constructive and helpful comments. This research was supported by the Swedish Research Council under Grant 2020-06415.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Irina Mancheva

Irina Mancheva is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Political Science, Umeå University. Her research interests include policy legitimacy, natural resource governance and environmental politics. Most recently she has published in Environmental Science and Policy, Energy Research and Social Science and Local Environment. [[email protected]].

Mia Pihlajamäki

Mia Pihlajamäki is a postdoctoral researcher at Aalto University. Her research focuses on marine and water policy and governance. She has published in Marine Policy, Environmental Policy and Planning and Technological Forecasting and Social Change, amongst others. [[email protected]].

Marko Keskinen

Marko Keskinen is an Associate Professor at Aalto University. His research interests include water resources governance, transboundary waters and sustainability as well as multi- and interdisciplinary approaches. His articles have appeared in journals such as Global Environmental Change, Water Alternatives and Journal of Hydrology. [[email protected]].

References

- Amsler, Lisa Blomgren (2016). ‘Collaborative Governance: Integrating Management, Politics and Law’, Public Administration Review, 76:5, 700–11.

- Batory, Agnes, and Sara Svensson (2020). ‘Regulating Collaboration: The Legal Framework of Collaborative Governance in Ten European Countries’, International Journal of Public Administration, 43:9, 780–9.

- Berardo, Ramiro, Manuel Fischer, and Matthew Hamilton (2020). ‘Collaborative Governance and the Challenges of Network-Based Research’, The American Review of Public Administration, 50:8, 898–913.

- Bondarouk, Elena, Duncan Liefferink, and Ellen Mastenbroek (2020). ‘Politics or Management? Analysing Differences in Local Implementation Performance of the EU Ambient Air Quality Directive’, Journal of Public Policy, 40:3, 449–72.

- Borja, Angel, Mike Elliott, Jacob Carstensen, Anna-Stiina Heiskanen, and Wouter van de Bund (2010). ‘Marine Management – Towards an Integrated Implementation of the European Marine Strategy Framework and the Water Framework Directives’, Marine Pollution Bulletin, 60:12, 2175–86.

- Brisbois, Marie Claire, and Rob C. de Loë (2016). ‘Power in Collaborative Approaches to Governance for Water: A Systematic Review’, Society & Natural Resources, 29:7, 775–90.

- Dressel, Sabrina, Göran Ericsson, Maria Johansson, Christer Kalén, Sabine E. Pfeffer, and Camilla Sandström (2020). ‘Evaluating the Outcomes of Collaborative Wildlife Governance: The Role of Social-Ecological System Context and Collaboration Dynamics’, Land Use Policy, 99, 105028.

- Eckerberg, Katarina, and Therese Bjärstig (2020). ‘Environmental Policy – the Challenge of Institutional Fit in a Complex Policy Area’, in Mats Öhlén and Daniel Silander (eds.), Sweden and the European Union: An Assessment of the Influence of EU-Membership on Eleven Policy Areas in Sweden. Stockholm: Santérus Förlag.

- Emerson, Kirk, and Tina Nabatchi (2015). Collaborative Governance Regimes. Washington DC: Georgetown University Press

- Emerson, Kirk, Tina Nabatchi, and Stephen Balogh (2012). ‘An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22:1, 1–29.

- Fink, Simon, and Eva Ruffing (2017). ‘The Differentiated Implementation of European Participation Rules in Energy Infrastructure Planning: Why Does the German Participation Regime Exceed European Requirements?’, European Policy Analysis, 3:2, 274–94.

- Fischer, Manuel, and Pascal Sciarini (2016). ‘Drivers of Collaboration in Political Decision Making: A Cross-Sector Perspective’, The Journal of Politics, 78:1, 63–74.

- Heidbreder, Eva (2017). ‘Strategies in Multilevel Policy Implementation: Moving Beyond the Limited Focus on Compliance’, Journal of European Public Policy, 24:9, 1367–1384.

- Hysing, Erik (2022). ‘Designing Collaborative Governance That is Fit for Purpose: Theorising Policy Support and Voluntary Action for Road Safety in Sweden’, Journal of Public Policy, 42:2, 201–23.

- Jacobsson, Bengt, and Göran Sundström (2007). Governing State Agencies: Transformations in the Swedish Administrative Model. Stockholm: Score

- Kallis, Giorgos, Michael Kiparsky, and Richard Norgaard (2009). ‘Collaborative Governance and Adaptive Management: Lessons from California’s CALFED Water Program’, Environmental Science & Policy, 12:6, 631–43.

- Koontz, Thomas M., and Jens Newig (2014). ‘From Planning to Implementation: Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches for Collaborative Watershed Management’, Policy Studies Journal, 42:3, 416–42.

- Kronsell, Annica, and Karin Bäckstrand (2010). ‘Rationalities and Forms of Governance: A Framework for Analysing the Legitimacy of New Modes of Governance’, in Karin Bäckstrand, Jamil Khan, Annica Kronsell and Eva Lövbrand (eds.) Environmental Politics and Deliberative Democracy: Examining the Promise of New Modes of Governance. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 28–46.

- Laegreid, Per (2017). ‘Nordic Administrative Traditions’, in Peter Nedergaard and Anders Wivel (eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Scandinavian Politics. London: Routledge, 80–91.

- Lubell, Mark, Adam Douglas Henry, and Mike McCoy (2010). ‘Collaborative Institutions in an Ecology of Games’, American Journal of Political Science, 54:2, 287–300.

- Majone, Giandomenico (1999). ‘The Regulatory State and Its Legitimacy Problems’, West European Politics, 22:1, 1–24.

- Martinsen, Dorte Sindbjerg, and Hans Vollaard (2014). ‘Implementing Social Europe in Times of Crises: Re-Established Boundaries of Welfare?’, West European Politics, 37:4, 677–92.

- Mee, Laurence D., Rebecca L. Jefferson, Dan d‘A Laffoley, and Michael Elliott (2008). ‘How Good is Good? Human Values and Europe’s Proposed Marine Strategy Directive’, Marine Pollution Bulletin, 56:2, 187–204.

- Metz, Florence, Mario Angst, and Manuel Fischer (2020). ‘Policy Integration: Do Laws or Actors Integrate Issues Relevant to Flood Risk Management in Switzerland?’, Global Environmental Change, 61, 101945.

- Miljand, Matilda, and Katarina Eckerberg (2022). ‘Using Systematic Reviews to Inform Environmental Policy-Making’, Evaluation, 28:2, 210–30.

- Newig, Jens, Edward Challies, Nicolas Jager, and Eliza Kochskämper (2014). ‘What Role for Public Participation in Implementing the EU Floods Directive? A Comparison with the Water Framework Directive, Early Evidence from Germany and a Research Agenda’, Environmental Policy and Governance, 24:4, 275–88.

- Newig, Jens, and Thomas M. Koontz (2014). ‘Multi-Level Governance, Policy Implementation and Participation: The EU’s Mandated Participatory Planning Approach to Implementing Environmental Policy’, Journal of European Public Policy, 21:2, 248–67.

- Ostrom, Elinor (2005). Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Princen, Sebastiaan, Frank Schimmelfennig, Ronja Sczepanski, Hubert Smekal, and Robert Zbiral (2022). ‘Different yet the Same? Differentiated Integration and Flexibility in Implementation in the European Union’, West European Politics. doi:10.1080/01402382.2022.2150944.

- Purdy, Jill M. (2012). ‘A Framework for Assessing Power in Collaborative Governance Processes’, Public Administration Review, 72:3, 409–17.

- Sabatier, Paul A., Will Focht, Mark Lubell, Zev Trachtenberg, and Arnold Vedlitz (eds.) (2005). Swimming Upstream: Collaborative Approaches to Watershed Management. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Skelcher, Chris (2000). ‘Changing Images of the State: Overloaded, Hollowed-Out, Congested’, Public Policy and Administration, 15:3, 3–19.

- Smajgl, Alex, John Ward, and Lucie Pluschke (2016). ‘The Water–Food–Energy Nexus–Realising a New Paradigm’, Journal of Hydrology, 533, 533–40.

- Thatcher, Mark, and Alec Stone Sweet (2002). ‘Theory and Practice of Delegation to Non-Majoritarian Institutions’, West European Politics, 25:1, 1–22.

- Thomann, Eva, and Fritz Sager (2017). ‘Moving beyond Legal Compliance: Innovative Approaches to EU Multilevel Implementation’, Journal of European Public Policy, 24:9, 1253–68.

- Trachtenberg, Zev, and Will Focht (2005). ‘Legitimacy and Watershed Collaborations: The Role of Public Participation’, in Sabatier (eds.), Swimming Upstream: Collaborative Approaches to Watershed Management. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Treib, Oliver (2014). ‘Implementing and Complying with EU Governance Outputs’, Living Reviews in European Governance, 9, 1.

- Sager, Fritz (2009). ‘Governance and Coercion’, Political Studies, 57:3, 537–58.

- Ulibarri, Nicola, Kirk Emerson, Mark T. Imperial, Nicolas W. Jager, Jens Newig, and Edward Weber (2020). ‘How Does Collaborative Governance Evolve? Insights from a Medium-N Case Comparison’, Policy and Society, 39:4, 617–37.

- Yin, Robert (2014). Case Study Research Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

- Zhelyazkova, Asya, Cansarp Kaya, and Reini Schrama (2016). ‘Decoupling Practical and Legal Compliance: Analysis of Member States’ Implementation of EU Policy’, European Journal of Political Research, 55:4, 827–46.

- Zhelyazkova, Asya, and Eva Thomann (2022). ‘I Did It My Way’: Customisation and Practical Compliance with EU Policies’, Journal of European Public Policy, 29:3, 427–47.

- Zhelyazkova, Asya, Eva Thomann, Eva Ruffing, and Sebastiaan Princen (2023). ‘Differentiated Policy Implementation in the European Union’, West European Politics, forthcoming.