Abstract

Polarisation over cultural issues and the emergence of radical, often populist, challenger parties indicate a fundamental restructuring of political conflict in Western Europe. The emerging divide crosscuts and, in part, reshapes older cleavages. This special issue introduction highlights how the transformation of cleavage structures relates to the dynamics of polarisation and political participation. The contributions to the special issue innovate in two ways. First, they adapt concepts and measures of ideological and affective polarisation to the context of Europe’s multi-party and multi-dimensional party competition. Second, they emphasise electoral and protest politics, examining how ideological and affective polarisation shape electoral and non-electoral participation. Apart from introducing the contributions, the introduction combines different datasets – the Chapel Hill Expert Survey, Comparative Study of Electoral Systems and the European Social Survey – to sketch an empirical picture of differentiated polarisation with types of polarisation only weakly associated cross-arena, cross-nationally and over time.

Polarisation over cultural issues and the emergence of radical, often populist, challenger parties indicate a fundamental restructuring of political conflict in Western EuropeFootnote1 in a globalising world (Walter Citation2021). Scholars adopting a structuralist perspective on political change may differ in their explanatory frameworks and labels for the new structural conflict – from ‘integration–demarcation’ (Kriesi et al. Citation2008, Citation2012), ‘universalism–communitarianism’ (Bornschier Citation2010), ‘cosmopolitanism–communitarianism’ (de Wilde et al. Citation2019), ‘cosmopolitanism–parochialism’ (De Vries Citation2018), ‘libertarian pluralist–authoritarian populist’ (Norris and Inglehart Citation2019) to the ‘transnational cleavage’ (Hooghe and Marks Citation2018). However, they agree that political conflict is in a state of flux and that the emerging societal and political divides crosscut and, in part, reshape older cleavages (on the latter, see Häusermann et al. Citation2022). In contrast to classical economic left–right conflict, the new ‘cultural’ cleavage raises fundamental issues of rule and belonging, and taps into various sources of conflicts about national identity, sovereignty, and solidarity. Thus, the emerging controversies concern questions related to the admission and integration of migrants, competing supranational sources of authority, and international economic competition. The contested issues related to the new cleavage – in particular, immigration (Grande et al. Citation2019; Green-Pedersen and Otjes Citation2019; van der Brug et al. Citation2015) and European integration (e.g. De Vries Citation2018; de Wilde et al. Citation2016; Hutter et al. Citation2016) – stand out because they are ever more salient and particularly polarising in party competition.

The scholarly literature on the transformation of cleavage structures in Europe provides the starting point of the special issue Under Pressure: Polarisation and Participation in Western Europe. Research on cleavage formation indicates that the restructuring of West European politics involves significant changes in the substance of contemporary party competition. However, as we argue, the articulation and mobilisation of the new cleavage have changed the ‘landscapes of political contestation’ beyond the programmatic or ideological level.

Yet, contemporary cleavage research is often too narrowly focussed on ideological changes in the electoral arena, zooming in on the substantive (mis)fit between citizens’ preferences and parties’ supply. In contrast, it tends to give short shrift to affective and identity-based processes of group formation (but see: Bornschier et al. Citation2021; Zollinger Citation2022) and to the dynamics in non-electoral politics (but see: Borbáth and Hutter Citation2021; Hutter Citation2014; della Porta Citation2015). To address these limitations, the special issue bridges the analysis of cleavage politics with current research on political polarisation and participation. The three strands of research highlight the interplay of ideological, affective and organisational changes in West European politics. In combination, these changes put existing political parties, institutions and procedures under pressure, challenging the foundations of representative democracy (della Porta Citation2013).

First, ever since Sartori’s (1976) seminal work on party systems, polarisation has been a central topic in the literature on European elections and party systems. However, most Europeanists, until recently, considered distance mainly in an ideological sense – often along a single left–right dimension. A burgeoning literature pioneered by research on the U.S. (Iyengar et al. Citation2012) has begun to distinguish affective from ideological polarisation. This strand of research challenges the view that polarisation is primarily an elite-level phenomenon (Bischof and Wagner Citation2019; Fiorina and Abrams Citation2008) and shows that partisan divisions on the demand side, i.e. among citizens, have an additional affective dimension in the European context as well (Gidron et al. Citation2020; Reiljan Citation2020; Wagner Citation2021). Feelings of group membership based on partisan identity elicit positive evaluations towards people in the same group and negative evaluations towards other groups. Amongst others, affective polarisation reduces citizens’ willingness to consider different points of view (Hobolt et al. Citation2021), makes cross-group cooperation more difficult (Iyengar and Westwood Citation2015), and shapes citizens’ policy positions (Druckman et al. Citation2021). Ultimately, we argue that cleavage theory implies a close link between ideological and affective polarisation along the main contested ‘cleavage issues’.

Second, the emerging cleavages are not only reconfiguring party systems and electoral behaviour. They also shape mobilisation and participation in non-electoral politics (e.g. Giugni and Grasso Citation2019; Hutter Citation2014). On the individual level, different forms of participation – already distinguished in the seminal work of Barnes and Kaase (Citation1979) – do not follow the same trends. While electoral turnout is in decline (Mair Citation2013), forms of ‘non-electoral’ or ‘non-institutionalised’ participation are increasingly widespread, and albeit with generational differences, an integral part of citizens’ action repertoire (Borbáth and Hutter Citation2022; Dalton Citation2008; Oser Citation2017). Moreover, recent social movement scholarship points to ever closer and consequential cross-arena interactions between electoral and protest politics. Again, research on the U.S. offers ample evidence on the impact of protest-induced polarisation on compromise-seeking and defection by moderate voters (e.g. Gillion Citation2020; McAdam and Kloos Citation2014; Tarrow Citation2021). Similarly, Europeanists have shown how so-called ‘movement parties’ from left (e.g. della Porta et al. Citation2017) and right (e.g. Caiani and Císař Citation2018; Castelli Gattinara and Pirro Citation2019) act as transmission belts between street protests and elections, and how protestors’ demands intensify party competition (e.g. Bremer et al. Citation2020; Císař and Vráblíková Citation2019; Walgrave and Vliegenthart Citation2019). In line with cleavage theory, we thus see a transformation of the landscapes of political contestation far beyond the electoral arena.

Building on these insights, the special issue Under Pressure: Polarisation and Participation in Western Europe innovates in two ways. First, inspired by cleavage research, the special issue offers novel measurement strategies and findings for both ideological and affective polarisation, adapting U.S.-based indicators to Europe’s multi-dimensional and multi-party context. Second, it advances our understanding of how ideological and affective polarisation drives citizens’ participation in electoral and non-electoral politics. Overall, the special issue demonstrates that we can only grasp the far-reaching restructuring of contemporary West European politics when considering polarisation ‘as rooted in affect and identity’ (Iyengar et al. Citation2019: 131) and when studying contestation across political arenas.

The introduction is structured in four sections. First, we sketch our dynamic and actor-centred approach to cleavage formation. Second, we link this approach with ideological and affective polarisation research and empirically illustrate the aggregate relationships between different types of polarisation. The third section shifts to the question of how polarisation affects participation, where we, again, empirically illustrate the dynamics at play. We conclude by providing a summary of our main arguments and introducing the individual contributions to the special issue.

Cleavage theory meets ideological and affective polarisation

Scholars in the Rokkanean tradition (Lipset and Rokkan Citation1967; Rokkan Citation2000) use the term ‘cleavages’ to label particularly salient and sticky patterns of opposition (for reviews, see Bornschier Citation2010; Deegan-Krause Citation2007). Following Bartolini and Mair’s (1990: 213ff.) influential definition, a fully developed cleavage includes an empirical, a normative, and an institutional element – i.e. a distinct social-structural basis, specific values and beliefs (a political consciousness), and their political organisation and mobilisation.Footnote2 Individualisation, cognitive mobilisation, and the general complexity of contemporary societies make it less likely to observe cleavages of a similar nature as the historical examples of Stein Rokkan. However, current scholarly work shows the lasting appeal of a Rokkanean framework, as taking such a perspective comes with at least two distinct advantages. On the one hand, it allows a holistic view by linking changes in contemporary conflict structures to long-term societal transformations and short-term shocks such as crises or catastrophes. On the other hand, it allows linking different levels of analysis, highlighting how political action at the micro-level lies at the intersection of meso-level mobilisation and macro-level opportunities and constraints (Kriesi Citation2008).

Yet, recent work in the Rokkanean tradition indicates that one should adopt a more dynamic and actor-centred perspective on cleavage formation (Enyedi Citation2005). Such perspective takes the role of contemporary political conflict for the perpetuation and transformation of cleavages more seriously than classic cleavage theory. Illustrative examples for this approach are the writings by Bornschier (Citation2010), Kriesi et al. (Citation2008, Citation2012) and Hooghe and Marks (Citation2018). Following a structuralist logic, these authors start from the idea that political parties and other political intermediaries are constrained to operate within a given competitive space. New issues and changes in the dimensions of party competition emerge exogenously, i.e. from social conflicts, which are products of long-term social change and exacerbate during crises. At the same time, they consider the agency of political actors in structuring new divides. A fundamental assumption is that to keep a cleavage alive or reinforce the relevance of a new social divide, the core issues linked to it need to give rise to publicly visible conflicts and activate citizens.

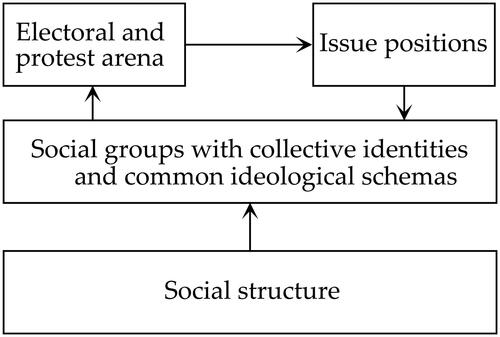

illustrates the recursive process of cleavage formation and perpetuation. The simple figure underscores the demand-driven nature of any cleavage model while emphasising the importance of the ideological content in party competition – and related political arenas. It assumes that conflict over specific issues activates people’s ideological schemata and ‘reinforces the established interpretation of what politics is about in the specific country’ (Bornschier Citation2010: 62). Manifest conflicts render group attachments salient and allow individuals to locate themselves in the political spaces. This is also where ideological polarisation – defined as ideological or programmatic distance – enters the picture of cleavage theory. That is, we should observe publicly visible and structured patterns of opposition along core issues linked to a cleavage, otherwise it will fade in the medium to long term.

Figure 1. A simple model of cleavage formation and perpetuation.

Source: Bornschier (Citation2010: 62), with modifications by the authors.

It is well documented that mainstream parties from left and right have been ill prepared to respond to the emerging new ideological polarisation because it crosscuts their traditional electoral coalitions (e.g. de Vries and Hobolt Citation2020; Häusermann and Kriesi Citation2015; Hooghe and Marks Citation2018). In turn, new political entrepreneurs – especially from the populist radical right – have successfully seised this opportunity by mobilising issues of order and belonging, and tapping into conflicts about national identity, sovereignty, and solidarity. Across Western Europe, the ‘twin issues’ related to the emergence of the new ‘cultural’ cleavage have been immigration (e.g. Grande et al. Citation2019; Green-Pedersen and Otjes Citation2019; van der Brug et al. Citation2015) and European integration (e.g. De Vries Citation2018; de Wilde et al. Citation2016; Hutter et al. Citation2016). Polarisation related to both issues has increased during Europe’s latest phase of multiple crises (Hooghe and Marks Citation2018; Hutter and Kriesi Citation2019), and their salience is highly predictive of the strength of populist radical right parties (e.g. Dennison and Geddes Citation2019).

As Dassonneville and Çakır (Citation2021) note in their recent review, most empirical research on ideological polarisation, however, still assesses the phenomenon on a single left–right dimension.Footnote3 Yet, an emerging strand of scholarly work incorporates insights from cleavage research by considering the role of a second ‘cultural’ dimension in this context (e.g. Dassonneville and Çakır Citation2021; McCoy et al. Citation2018; Roberts Citation2022). Dassonneville and Çakır (Citation2021) themselves observe, based on the comparative manifesto data, persistent socio-economic polarisation alongside a cross-national trend towards increasing polarisation over social and postmaterialist issues. At the same time, they do not find a uniform trend towards polarisation over national identity and immigration issues. As the authors document substantial heterogeneity across countries and elections, they argue that the extent to which the rise of the new cleavage brings about ideological polarisation depends on the salience of the cultural dimension. In this regard, Dassonneville and Çakır distinguish two scenarios, one in which the new cleavage exists alongside the old socio-economic division and one in which the new cleavage replaces the old socio-economic divide as the central dimension of conflict.

Echoing the replacement scenario, McCoy et al. (Citation2018: 18) suggest defining polarisation as a process where the ‘multiplicity of differences in a society increasingly align along a single dimension, crosscutting differences become instead reinforcing, and people increasingly perceive and describe politics and society in terms of “Us” versus “Them”’. Based on illustrative cases studies for Hungary, the U.S., Turkey, and Venezuela, the authors show how such a relational and political understanding of polarisation helps to conceive processes of democratic erosion. As Roberts (Citation2022) aptly shows in another recent contribution on the link between populism and polarisation, such a reconfiguration depends heavily on actors’ strategies and their ability to navigate in the new multi-dimensional political space. Thus, distinguishing ideological polarisation over the two dimensions provides analytical and empirical leverage even in contexts where they align along a single axis of competition.

Contemporary research in the Rokkanean tradition has been key in advancing the understanding that ideological polarisation should be studied along multiple dimensions and what kind of social-structural features drive support for the opposing ideological positions. However, it tends to neglect the distinctive collective identities that are emerging (but see: Bornschier et al. Citation2021; Zollinger Citation2022). This limitation is remarkable given the historical references and the theoretical emphasis on what Bartolini and Mair (Citation1990: 224) have called the ‘degree of closure’ of a cleavage – closure referring to clearly separated and highly integrated social groups ‘through marriage, educational institutions, the urban and spatial setting of the population, social customs, religious practices and so on’. Relatedly, studies on consociational democracy have dealt extensively with the challenges of ‘social closure’ and ‘pillarisation’ associated with cleavage politics. In this line of scholarly work, experiences in Western Europe during the 19th and 20th centuries have provided critical examples of institutional mechanisms that successfully integrate conflict and provide possible governance models for ethnically, religiously, or economically divided societies (e.g. Lijphart Citation2002).

We consider the U.S.-focussed literature on affective polarisation – typically referring to partisan animosity (Iyengar et al. Citation2019) – a good starting point to revive the study of the social-identitarian dimension of cleavage politics (cf. Helbing and Jungkurz Citation2020). First, this line of research puts notions of in- and out-group evaluations at the centre stage. Second, it emphasises affect and emotions, i.e. positive feelings for the in-group and negative feelings for the out-group. Third, it focuses on the attitudinal and behavioural consequences of affective distances, considering the spill-over to everyday life and social encounters. Ultimately, high affective polarisation makes cleavage boundaries less permeable. It reduces citizens’ willingness to consider other points of view (Hobolt et al. Citation2021) and makes cross-group cooperation more difficult (Iyengar and Westwood Citation2015). Thus, we argue that a fully-fledged cleavage implies a close link between ideological and affective polarisation, shaping behaviour far beyond Election Day.

Research on the U.S. (e.g. Iyengar et al. Citation2012) and Europe (e.g. Gidron et al. Citation2020; Reiljan Citation2020; Wagner Citation2021) highlights that current political conflicts cannot be reduced to ideological elements only. Distinguishing affective from ideological polarisation renders it an open empirical question to what extent the emerging ideological distances linked to new cleavage issues are (already) related to mobilised group identities (Druckman et al. Citation2021; Harteveld Citation2021a, Citation2021b). From this perspective, affective polarisation does not necessarily ‘move together’ with ideological polarisation. Affective polarisation might result from ‘top-down’ processes of collective identity formation, unencumbered by socio-demographic anchors, or be based on socio-demographic distinctions that are not programmatically mobilised, e.g. certain ethnic divides (Reiljan Citation2020).

As a simple first cut at this question, we calculated the correlations between aggregate ideological and affective polarisation levels across eleven West European countries. Regarding ideological polarisation, we rely on Dalton’s (Citation2008) measure and calculated economic left–right and the cultural GAL–TAN polarisation for eleven West European party systems based on the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) (Jolly et al. Citation2022).Footnote4 We matched those measures to the nearest year in Wagner’s (Citation2021) data for affective polarisation among citizens. Overall, we find no relationship between these aggregate measures: The correlation coefficients are 0.06 for the link between economic left–right polarisation and affective polarisation and −0.02 for the link between GAL–TAN polarisation and affective polarisation. Our results mirror research on the U.S., which clearly indicates growing affective polarisation but finds less clear-cut evidence for ideological polarisation (e.g. Iyengar et al. Citation2019; Mason Citation2015). They are also in line with individual-level evidence for Europe by Wagner (Citation2021), showing a positive, yet weak association of affective polarisation and perceived ideological polarisation.

One could conclude that the weak empirical associations between ideological polarisation in party competition and affective polarisation among citizens renders the latter useless for studying cleavage politics in Western Europe. As Mason (Citation2015: 142) argues for the U.S. case, the mismatch may signal the power of partisan identities and ‘a nation of people driven powerfully by team spirit, but less powerfully by logically connections of issues to action’. However, interpreted from a cleavage perspective, it may also signal that in the European context the emerging collective identities and related in-/out-group dynamics are less structured by political parties as identity-markers but by other politicised social identities. As Bornschier et al. (Citation2021: 2113) show in their ground-breaking study on the Swiss case, the new cultural divide has the ‘potential to structure how people think about who they are and where they stand in an emerging group conflict’. The most politicised identities are structurally rooted, yet they are culturally connoted such as cosmopolitanism, Swiss or ‘being culturally interested’ (see also Zollinger Citation2022). Relatedly, Hobolt et al. (Citation2021) show how opinion-based identities – in their case Brexit-related identities of ‘Leavers’ and ‘Remainers’ – can also in the short-run lead to new politicised identities, crosscutting partisan identities. As the authors argue, not every issue can trigger comparatively strong polarisation. Put differently, it seems no coincidence that Brexit involves heightened conflicts over both issues – European integration and immigration – singled out as key for the emerging new cleavage (see above).

To sum up, we argue that Europeanist should not too quickly consider the concept of affective polarisation pointless when studying emerging cleavage structures. However, as for ideological polarisation, the concept and its measurement need adaption to Europe’s multi-party systems and the emerging collective identities on both sides of the new cleavage.

From polarisation to participation in electoral and non-electoral politics

Next to adapting concepts of polarisation to a multi-party and multi-dimensional context, the articles in the special issue Under Pressure: Polarisation and Participation in Western Europe push the agenda of cleavage research beyond a narrow focus on vote choice. Specifically, they examine how ideological and affective polarisation influences people’s decision to participate in politics. Although the theoretical linkages between polarisation and participation seem relatively straightforward, empirical evidence on the matter is mixed (e.g. Bischof and Wagner Citation2019; Houle and Kenny Citation2018; Huber and Ruth Citation2017; Leininger and Meijers Citation2021; Spittler Citation2018). The prevailing view on the link between ideological polarisation (which most of the literature focuses on) and participation has been positive because programmatic differentiation between parties should make elections more ‘meaningful’ to citizens (see, for instance, Wessels and Schmitt Citation2008). Indeed, while results are less clear for the U.S. (Fiorina et al. Citation2008; Hetherington Citation2008), there is now robust evidence that ideological polarisation increases turnout in multi-party systems (Abramowitz and Saunders Citation2008; Béjar et al. Citation2020; Hobolt and Hoerner Citation2020; Moral Citation2017; Steiner and Martin Citation2012; Wilford Citation2017). Evidence comes from a variety of geographical contexts, from Asia (Wang and Shen Citation2018), Europe (Moral Citation2017) and Latin America (Béjar et al. Citation2020). Also, proximity voting (Lachat Citation2011; Singer Citation2016) and correct voting (Pierce and Lau Citation2019) seem to be strengthened by ideological polarisation. However, as ideological polarisation also intensifies party attachments (Lupu Citation2016), whether these results reflect better informed or simply more partisan vote choices is unclear.

Scholars’ views of the link between affective polarisation and participation are decidedly less favourable compared to ideological polarisation. Here, negative interpretations dominate as affective polarisation is seen as reducing citizens’ willingness to consider other points of view (Hobolt et al. Citation2021) and making cross-group cooperation more difficult (Iyengar and Westwood Citation2015). However, affective polarisation may still be ‘a blessing in disguise’, as Harteveld and Wagner in this special issue put it, in that these dynamics can lead to popular mobilisation. The greater the dislike of other parties, the more is perceived to be at stake in the political contest and the more critical it becomes to vote not just to support the in-party but to keep the out-party, the political opponent, away from political office.

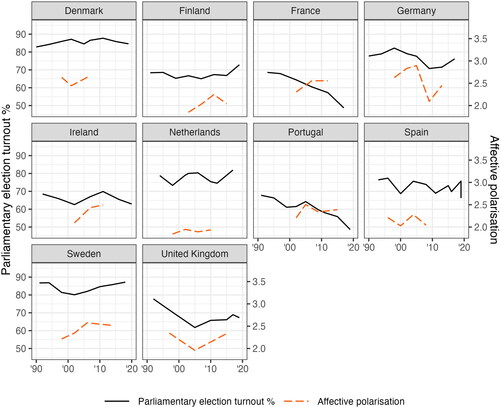

In that regard, it is interesting to notice that the well-documented, long-term decline in turnout (Gray and Caul Citation2000; Hooghe and Kern Citation2017; Leininger Citation2015) seems to have halted or even reversed in some countries, as illustrates for 10 West European countries. We also plot in the temporal development of affective polarisation, again drawing on Wagner’s (Citation2021) measure and data. While the figure shows that the geographic and temporal coverage of aggregate affective polarisation is still limited, the initial stock-taking of the available evidence is nevertheless informative. For instance, Germany displays a conspicuous parallel movement of turnout and affective polarisation. The rise in turnout and affective polarisation from 2009 to 2013 coincides with the populist right Alternative for Germany’s (AfD) appearance on the German political scene. Similar suggestive patterns appear, among others, in Spain and United Kingdom. However, there are cases where affective polarisation and turnout seem to be trending in opposite directions, such as in France, or not correlated, such as in Finland.

Figure 2. Trends in electoral turnout and affective polarisation.

Note: We rely on ParlGov to measure electoral turnout in national parliamentary elections.

As emphasised in the introductory section, the new cleavages are not only reconfiguring party systems and electoral behaviour, but have also left their marks on mobilisation and participation beyond Election Day (e.g. Giugni and Grasso Citation2019; Hutter Citation2014). To emphasise this point, Kriesi et al. (Citation2012) have introduced the concept of ‘cleavage coalitions’, referring to the diverse constellation of actors that articulate and mobilise conflicts not only in the electoral but also in the protest and civil society arenas. Such cross-arena mobilisation might originate from a coalition between different types of organisations or from direct mobilisation by political parties on the streets (Borbáth and Hutter Citation2021). Hutter and Kriesi (Citation2013) argue that it is in crucial moments of cleavage transformation that mobilisation in the two arenas strongly reinforces each other (see also Borbáth and Hutter Citation2022). The initially cited literature from the U.S. (e.g. Gillion Citation2020; McAdam and Kloos Citation2014; Tarrow Citation2021) and Europe (e.g. Bremer et al. Citation2020; Caiani and Císař Citation2018; Castelli Gattinara and Pirro Citation2019; Císař and Vráblíková Citation2019; della Porta et al. Citation2017) offers ample evidence on the close and consequential interplay of protest and electoral politics.

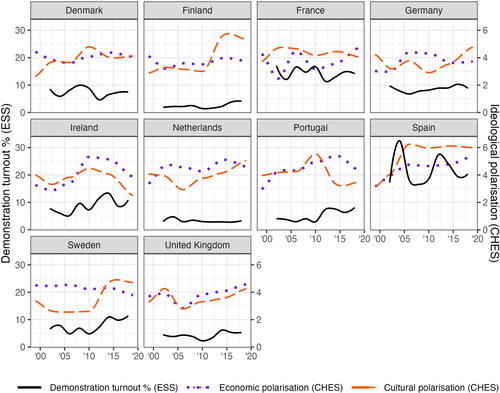

From such a perspective, as the new cleavage becomes fully mobilised, we might also expect an ever-closer relationship between polarisation in the electoral arena and protest participation. We empirically illustrate the idea by comparing developments in demonstration turnout with trends in ideological polarisation. To do so, shows aggregate trends from the European Social Survey (ESS) based on whether respondents have taken part in a lawful public demonstration in the last 12 months.Footnote5 As shows, while participation in demonstrations develops in waves, ideological polarisation among parties follows a more organic development with punctuated moments of change that alter its long-term trend. Focussing on polarisation on the cultural dimension, the case of Sweden is illustrative: Between 2010 and 2014, after the populist radical right Sweden Democrats entered parliament, cultural polarisation dramatically increased, and this development went hand in hand with an increase in participation in demonstrations. We can also observe different patterns, with Germany as an illustrative example where we observe increasing polarisation on the cultural dimension after the AfD’s entrance to parliament in 2017. However, that trend started earlier, and it did not come with a significant rise in demonstration turnout. In some cases (most notably in France and Portugal), the development of demonstration turnout is also more closely related to polarisation on the economic dimension. Overall, these aggregate associations do not speak for a direct translation of increasing polarisation to increasing levels of participation. Yet, they point to interesting avenues for research, explaining under what conditions polarisation relates to the dynamics of protest and other forms of participation. These questions are addressed in the second part of this special issue.

Introducing the individual contributions

This introduction argues for bridging studies on cleavage politics with polarisation and political participation research. Taken together, the three strands of research help us to understand better the interplay of ideological, affective and organisational transformations in West European politics. We have set out to make two key contributions connecting the articles in the special issue. First, we have linked current cleavage research to studies of ideological and affective polarisation, both from a conceptual as well as from a methodological perspective. Second, we have zoomed in on the role ideological and affective polarisation play in shaping citizens’ engagement in electoral and non-electoral forms of participation.

Regarding our first ambition, we have theoretically examined and empirically illustrated how the rise in the salience of crosscutting cleavage issues transformed party competition in the region. We argue that, Western European parties compete in a two-dimensional political space. We have also contributed to the cleavage literature by arguing that non-ideological, affective dynamics should be accounted for not only as an add-on to ideological polarisation but as a phenomenon in its own right. In this regard, our descriptive results are instructive as they show that aggregate levels of ideological and affective polarisation do not systematically relate to each other. The contributions to the special issue highlight the consequences of a restructured political space for researching polarisation in contemporary West European democracies and beyond. The individual articles offer innovations in terms of novel measurement strategies and insights regarding group-based ideological divisions (Traber et al. Citation2022), the effects of consistent party positions in a two-dimensional space (Dassonneville et al. Citation2022), and affective divides related to European integration (Hahm et al. Citation2022).

In their contribution Group-based Public Opinion Polarisation in Multi-Party Systems, Traber et al. (Citation2022) propose a refined measure of ideological polarisation and apply it to survey data from Switzerland. Following the cleavage perspective, the authors argue that scholars should put conflicts between groups in society centre stage. Methodologically, the authors innovate by combining hierarchical item response models with a distance measure based on probability distributions. This allows the examination of the overlap of ideology distributions between groups and the development of group-based polarisation over time. For cleavage research, it is important that the proposed measure allows differentiating across and within-group polarisation, thus showing whether the restructuring of party competition and the rise of challenger parties go along with ever more ideologically distant and internally cohesive groups.

In Partisan Attachments in a Multidimensional Space, Dassonneville et al. (Citation2022) provide new evidence about how the restructuring of party competition affects party identification. The authors argue that scholars should move beyond a one-dimensional understanding of ideological polarisation when studying the European context. Dassonneville et al. demonstrate that what matters for mass partisanship are both distances between the political parties on each dimension and their overall location in the political space. Combining European Social Survey and Chapel Hill Expert data, they show that the more political parties position themselves along a new economic-cultural diagonal, the higher the share of citizens in the electorate identifying with these parties.

Concluding this first set of articles, Hahm et al. (Citation2022) examine affective polarisation over European integration. In their article Divided by Europe: Affective Polarisation in European Parliament Elections, the authors zoom in on how affective divides relate to one of the key new ‘cleavage issues’. To investigate the multidimensional structure of political conflict, the authors combine a conjoint experiment with decision-making games from behavioural economics, fielded in 25 EU member states. Hahm et al. demonstrate that the divide over European identities feeds on out-group animosity rather than in-group favouritism – a result that underscores its potential for polarisation.

Regarding our second ambition, we have argued that the effect of supply-side transformations alters patterns of participation in and beyond the electoral arena. As our literature review and descriptive analyses indicate, polarisation does not always lead to higher participation in elections and protests. Still, in key transformative moments, the two follow each other more closely. In this regard, increasing polarisation can turn around the long-term decline of electoral participation and reinvigorate participation in general. The contributions to the special issue highlight the positive effect of affective polarisation on electoral turnout (Harteveld and Wagner Citation2022) and how the rise and success of populist parties may not necessarily lead to higher participation but can spur political interest (Nemčok et al. Citation2022). The contributions also provide novel insights into how the heterogeneity of social media platforms is reshaping citizens’ participation repertoire (Theocharis et al. Citation2022) and the links between ideological polarisation and citizens’ willingness to protest during the Covid-19 pandemic (Hunger et al. Citation2023).

In their contribution Does Affective Polarisation Increase Turnout? Harteveld and Wagner (Citation2022) assemble an impressive array of longitudinal datasets – from Germany, Spain and the Netherlands – to demonstrate a robust positive effect of affective polarisation on participation in elections. Using individual-level data allows them to investigate who is mobilised by affective polarisation. The polarisation effect appears to be strongest for those less interested in politics. Importantly, their use of longitudinal data also allows them to ascertain that polarisation precedes the decision to turn out to vote.

The article Softening the Corrective Effect of Populism, by Nemčok et al. (Citation2022) argue that the impact of populist parties, as key mobilising agents of non-mainstream positions, does not result in higher participation rates immediately, which explains mixed empirical evidence found in previous research. Therefore, they propose taking a step back in the chain of causality and examining the effect of polarisation on political interest. Nemčok et al. find, based on cross-national data of 97 national elections, that the mere presence of at least one populist party, their number and their electoral success are all positively correlated with individual political interest. Importantly, this relationship is stronger for less-educated citizens.

A limitation of the scholarly literature on participation and polarisation is the insufficient attention to how the heterogeneity of social media platforms alters the structure of participation modes. In Platform Affordances and Political Participation, Theocharis et al. (Citation2022) distinguish between digitally-supported versus digitally-enabled acts and stress the importance of platform affordances to further differentiate among the latter. Based on original survey data for France, the U.S. and the U.K., Theocharis et al. find support for the argument that social media-enabled forms of participation are independent of traditional modes of participation and do not consist of a uniform block. The one-sided ‘following decisions’ on Twitter result in different dynamics than the two-sided decisions on Facebook where both parties need to agree to follow each other.

In the final contribution The Mobilisation Potential of Anti-containment Protests in Germany, Hunger et al. (Citation2023) focus on protest and ideological polarisation triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic. While most European citizens supported the governments’ containment measures, others took to the streets and voiced dissatisfaction. Analysing Germany, where large-scale demonstrations took place, the authors examine understanding for and willingness to participate in demonstrations against the state’s containment measures. Based on 16 waves of a cross-sectional survey, Hunger et al. show that every fifth respondent understands the protesters, and around 60 percent of those are ready to participate. Political distrust, far-right orientations, and an emerging ‘freedom divide’ structure the potential. Moreover, the findings indicate a radicalisation process and show how ideology and threat perceptions drive the step from understanding to a willingness to participate.

In times of multiple crises, in which politics often responds to short-term pressures of recessions, pandemics or even war, we highlight the role of long-term structural processes. We argue that the transformation of cleavage structures underpins ideological and affective polarisation dynamics, shaping in turn patterns of mobilisation and participation far beyond Election Day. In this regard, the contributions to this special issue, we hope, provide crucial insights for a more extensive research agenda that combines cleavage politics with polarisation and participation research to grasp better the ongoing transformations in Europe’s democracies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all contributors to the special issue, participants of the ‘Under pressure: Electoral and non-electoral participation in polarizing times’ workshop, the anonymous reviewers, Wolfgang C. Müller and Raphaël Létourneau. Endre Borbáth and Swen Hutter would also like to acknowledge financial support from the Volkswagen Foundation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Endre Borbáth

Endre Borbáth is a postdoctoral researcher at the Freie Universität Berlin and at the Centre for Civil Society Research, a joint initiative of Freie Universität and the WZB Berlin Social Science Centre. [[email protected]]

Swen Hutter

Swen Hutter is Lichtenberg-Professor of Political Sociology at Freie Universität Berlin and Vice Director of the Centre for Civil Society Research, a joint initiative of Freie Universität and the WZB Berlin Social Science Centre. [[email protected]]

Arndt Leininger

Arnd Leininger is an Assistant Professor for Political Science Research Methods at the Chemnitz University of Technology. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 The contributions to the special issue mainly but not exclusively cover Western Europe.

2 In that sense, cleavages cannot be reduced either to social divides (‘social cleavages’) or purely political struggles (‘political cleavages’). As Bartolini (Citation2005) aptly stated in a later publication, the concept of ‘cleavages’ does not come with adjectives attached.

3 Dalton (Citation2021), for instance, finds that polarisation along a left-right dimension is primarily predicted by cross-national characteristics of the electoral and party system. While he also tests the role of more dynamic factors, some associated with the second conflict dimension, these play a limited role in explaining changes in general left-right polarisation.

4 These are Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom, the Western European countries for which both the ideological and the affective polarisation measure is available for at least two time points.

5 For polarisation, we rely again on the economic left-right and cultural GAL-TAN positions of political parties from CHES and the measure proposed by Dalton (Citation2008: 906).

References

- Abramowitz, Alan I., and Kyle L. Saunders (2008). ‘Is Polarization a Myth?’, The Journal of Politics, 70:2, 542–55.

- Barnes, Samuel H., and Max Kaase (1979). Political Action: Mass Participation in Five Western Democracies. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

- Bartolini, Stefano (2005). Restructuring Europe: Centre Formation, System Building, and Political Structuring between the Nation State and the European Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bartolini, Stefano, and Peter Mair (1990). Identity, Competition, and Electoral Availability: The Stabilisation of European Electorates 1885–1985. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Béjar, Sergio, Juan A. Moraes, and Santiago López-Cariboni (2020). ‘Elite Polarization and Voting Turnout in Latin America, 1993–2010’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 30:1, 1–21.

- Bischof, Daniel, and Markus Wagner (2019). ‘Do Voters Polarize When Radical Parties Enter Parliament?’, American Journal of Political Science, 63:4, 888–904.

- Borbáth, Endre, and Swen Hutter (2021). ‘Protesting Parties in Europe: A Comparative Analysis’, Party Politics, 27:5, 896–908.

- Borbáth, Endre, and Swen Hutter (2022). ‘Bridging Electoral and Nonelectoral Political Participation’, in Maria T. Grasso and Marco Giugni (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Participation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 451–70.

- Bornschier, Simon (2010). Cleavage Politics and the Populist Eight: The New Cultural Conflict in Western Europe. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Bornschier, Simon, Silja Häusermann, Delia Zollinger, and Céline Colombo (2021). ‘How “Us” and “Them” Relates to Voting Behavior – Social Structure, Social Identities, and Electoral Choice’, Comparative Political Studies, 54:12, 2087–122.

- Bremer, Björn, Swen Hutter, and Hanspeter Kriesi (2020). ‘Dynamics of Protest and Electoral Politics in the Great Recession’, European Journal of Political Research, 59:4, 842–66.

- Caiani, Manuela, and Ondřej Císař (2018). Radical Right Movement Parties in Europe. London: Routledge.

- Castelli Gattinara, Pietro, and Andrea L. P. Pirro (2019). ‘The Far Right as Social Movement’, European Societies, 21:4, 447–62.

- Císař, Ondřej, and Kateřina Vráblíková (2019). ‘National Protest Agenda and the Dimensionality of Party Politics: Evidence from Four East-Central European Democracies’, European Journal of Political Research, 58:4, 1152–71.

- Dalton, Russell J. (2008). ‘Citizenship Norms and the Expansion of Political Participation’, Political Studies, 56:1, 76–98.

- Dalton, Russell J. (2021). ‘Modeling Ideological Polarization in Democratic Party Systems’, Electoral Studies, 72, 102346.

- Dassonneville, Ruth, and Semih Çakır (2021). ‘Party System Polarization and Electoral Behavior’, in William R. Thompson (ed.), Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1979.

- Dassonneville, Ruth, Patrick Fournier, and Zeynep Somer-Topcu (2022). ‘Partisan Attachments in a Multi-Dimensional Space’, West European Politics, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2087387.

- De Vries, Catherine E. (2018). Euroscepticism and the Future of European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- de Vries, Catherine E., and Sara B. Hobolt (2020). Political Entrepreneurs: The Rise of Challenger Parties in Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- de Wilde, Pieter, Ruud Koopmans, Wolfgang Merkel, Oliver Strijbis, and Michael Zürn, eds. (2019). The Struggle Over Borders: Cosmopolitanism and Communitarianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- de Wilde, Pieter, Anna Leupold, and Henning Schmidtke (2016). ‘Introduction: The Differentiated Politicisation of European Governance’, West European Politics, 39:1, 3–22.

- Deegan-Krause, Kevin (2007). ‘New Dimensions of Political Cleavage’, in Russell J. Dalton and Hans-Dieter Klingemann (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 538–56.

- della Porta, Donatella (2013). Can Democracy Be Saved?: Participation, Deliberation and Social Movements. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- della Porta, Donatella (2015). Social Movements in Times of Austerity: Bringing Capitalism Back into Protest Analysis. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- della Porta, Donatella, Joseba Fernández, Hara Kouki, and Lorenzo Mosca (2017). Movement Parties Against Austerity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Dennison, James, and Andrew Geddes (2019). ‘A Rising Tide? The Salience of Immigration and the Rise of Anti-Immigration Political Parties in Western Europe’, The Political Quarterly, 90:1, 107–16.

- Druckman, James. N., Samara Klar, Yanna Krupnikov, Matthew Levendusky, and John Barry Ryan (2021). ‘Affective Polarization, Local Contexts and Public Opinion in America’, Nature Human Behaviour, 5:1, 28–38.

- Enyedi, Zsolt (2005). ‘The Role of Agency in Cleavage Formation’, European Journal of Political Research, 44:5, 697–720.

- Fiorina, Morris P., and Samuel J. Abrams (2008). ‘Political Polarization in the American Public’, Annual Review of Political Science, 11:1, 563–88.

- Fiorina, Morris P., Samuel A. Abrams, and Jeremy C. Pope (2008). ‘Polarization in the American Public: Misconceptions and Misreadings’, The Journal of Politics, 70:2, 556–60.

- Gidron, Noam, James Adams, and Will Horne (2020). American Affective Polarization in Comparative Perspective (Elements in American Politics). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gillion, Daniel Q. (2020). The Loud Minority: Why Protests Matter in American Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Giugni, Marco, and Maria T. Grasso (2019). Street Citizens: Protest Politics and Social Movement Activism in the Age of Globalization. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Grande, Edgar, Tobias Schwarzbözl, and Matthias Fatke (2019). ‘Politicizing Immigration in Western Europe’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:10, 1444–63.

- Gray, Mark, and Miki Caul (2000). ‘Declining Voter Turnout in Advanced Industrial Democracies, 1950 to 1997: The Effects of Declining Group Mobilization’, Comparative Political Studies, 33:9, 1091–122.

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer, and Simon Otjes (2019). ‘A Hot Topic? Immigration on the Agenda in Western Europe’, Party Politics, 25:3, 424–34.

- Hahm, Hyeonho, David Hilpert, and Thomas König (2022). ‘Divided by Europe: Affective Polarization in the Context of European Elections’, West European Politics, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2133277

- Harteveld, Eelco (2021a). ‘Ticking All the Boxes? A Comparative Study of Social Sorting and Affective Polarization’, Electoral Studies, 72, 102337.

- Harteveld, Eelco (2021b). ‘Fragmented Foes: Affective Polarization in the Multiparty Context of The Netherlands’, Electoral Studies, 71, 102332.

- Harteveld, Eelco, and Markus Wagner (2022). ‘Does Affective Polarisation Increase Turnout? Evidence from Germany, The Netherlands and Spain’, West European Politics, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2087395.

- Häusermann, Silja, and Hanspeter Kriesi (2015). ‘What Do Voters Want? Dimensions and Configurations in Individual-Level Preferences and Party Choice’, in Pablo Beramendi, Silja Häusermann, Herbert Kitschelt, and Hanspeter Kriesi (eds.), The Politics of Advanced Capitalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 202–30.

- Häusermann, Silja, Michael Pinggera, Macarena Ares, and Matthias Enggist (2022). ‘Class and Social Policy in the Knowledge Economy’, European Journal of Political Research, 61:2, 462–84.

- Helbling, Marc, and Sebastian Jungkunz (2020). ‘Social Divides in the Age of Globalization’, West European Politics, 43:6, 1871–10.

- Hetherington, Marc J. (2008). ‘Turned Off or Turned On? How Polarization Affects Political Engagement’, in Pietro S. Nivola and David W. Brady (eds.), Red and Blue Nation?: Consequences and Correction of America’s Polarized Politics. Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 1–54.

- Hobolt, Sara B., and Julian M. Hoerner (2020). ‘The Mobilising Effect of Political Choice’, European Journal of Political Research, 59:2, 229–47.

- Hobolt, Sara B., Thomas J. Leeper, and James Tilley (2021). ‘Divided by the Vote: Affective Polarization in the Wake of the Brexit Referendum’, British Journal of Political Science, 51:4, 1476–93.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks (2018). ‘Cleavage Theory Meets Europe’s Crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the Transnational Cleavage’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:1, 109–35.

- Hooghe, Marc, and Anna Kern (2017). ‘The Tipping Point between Stability and Decline: Trends in Voter Turnout, 1950–1980–2012’, European Political Science, 16:4, 535–52.

- Houle, Christian, and Paul. D. Kenny (2018). ‘The Political and Economic Consequences of Populist Rule in Latin America’, Government and Opposition, 53:2, 256–87.

- Huber, Robert A., and Saskia P. Ruth (2017). ‘Mind the Gap! Populism, Participation and Representation in Europe’, Swiss Political Science Review, 23:4, 462–84.

- Hunger, Sophia, Swen Hutter, and Eylem Kanol (2023). ‘The mobilisation potential of anti-containment protests in Germany’, West European Politics, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2023.2166728

- Hutter, Swen (2014). Protesting Culture and Economics in Western Europe: New Cleavages in Left and Right Politics. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

- Hutter, Swen, Edgar Grande, and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. (2016). Politicising Europe: Integration and Mass Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hutter, Swen, and Hanspeter Kriesi (2013). ‘Movements of the Left, Movements of the Right Reconsidered’, in Jacquelien Van Stekelenburg, Conny Roggeband, and Bert Klandermans (eds.), The Future of Social Movement Research: Dynamics, Mechanisms, and Processes. Mineapolis: Minnesota Scholarship Online, 281–98.

- Hutter, Swen, and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. (2019). European Party Politics in Times of Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Iyengar, Shanto, Yphtach Lelkes, Matthew Levendusky, Neil Malhotra, and Sean J. Westwood (2019). ‘The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States’, Annual Review of Political Science, 22:1, 129–46.

- Iyengar, Shanto, Gaurav Sood, and Yphtach Lelkes (2012). ‘Affect, Not Ideology: A Social Identity Perspective on Polarization’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 76:3, 405–31.

- Iyengar, Shanto, and Sean J. Westwood (2015). ‘Fear and Loathing across Party Lines: New Evidence on Group Polarization’, American Journal of Political Science, 59:3, 690–707.

- Jolly, Seth, et al. (2022). ‘Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File, 1999–2019’, Electoral Studies, 75, 102420.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter (2008). ‘Political Mobilisation, Political Participation and the Power of the Vote’, West European Politics, 31:1-2, 147–68.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Martin Dolezal, Marc Helbling, Dominic Höglinger, Swen Hutter, and Bruno Wüest (2012). Political Conflict in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey (2008). West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lachat, Romain (2011). ‘Electoral Competitiveness and Issue Voting’, Political Behavior, 33:4, 645–63.

- Leininger, Arndt (2015). ‘Direct Democracy in Europe: Potentials and Pitfalls’, Global Policy, 6:S1, 17–27.

- Leininger, Arndt, and Maurits J. Meijers (2021). ‘Do Populist Parties Increase Voter Turnout? Evidence from Over 40 Years of Electoral History in 31 European Democracies’, Political Studies, 69:3, 665–85.

- Lijphart, Arend (2002). ‘The Evolution of Consociational Theory and Consociational Practices, 1965–2000’, Acta Politica Special Issue, 37:1–2, 11–22.

- Lipset, Seymour Martin, and Stein Rokkan (1967). Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York: Free Press.

- Lupu, Noam (2016). Party Brands in Crisis: Partisanship, Brand Dilution, and the Breakdown of Political Parties in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mair, Peter (2013). Ruling the Void: The Hollowing of Western Democracy. London: Verso Books.

- Mason, Liliana (2015). ‘"I Disrespectfully Agree”: The Differential Effects of Partisan Sorting on Social and Issue Polarization’, American Journal of Political Science, 59:1, 128–45.

- McAdam, Doug, and Karina Kloos (2014). Deeply Divided: Racial Politics and Social Movements in Post-War America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McCoy, Jennifer, Tahmina Rahman, and Murat Somer (2018). ‘Polarization and the Global Crisis of Democracy: Common Patterns, Dynamics, and Pernicious Consequences for Democratic Polities’, American Behavioral Scientist, 62:1, 16–42.

- Moral, Mert (2017). ‘The Bipolar Voter: On the Effects of Actual and Perceived Party Polarization on Voter Turnout in European Multiparty Democracies’, Political Behavior, 39:4, 935–65.

- Nemčok, Miroslav, Constantin Manuel Bosancianu, Olga Leshchenko, and Alena Kluknavská (2022). ‘Softening the Corrective Effect of Populism: How Populist Parties Increase Political Interest, Not Turnout, among Individuals’, West European Politics, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2089963

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart (2019). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Oser, Jennifer (2017). ‘Assessing How Participators Combine Acts in Their “Political Tool Kits”: A Person-Centered Measurement Approach for Analyzing Citizen Participation’, Social Indicators Research, 133:1, 235–58.

- Pierce, Douglas R., and Richard R. Lau (2019). ‘Polarization and Correct Voting in U.S. Presidential Elections’, Electoral Studies, 60, 102048.

- Reiljan, Andres (2020). ‘"Fear and Loathing Across Party Lines” (also) in Europe: Affective Polarisation in European Party Systems’, European Journal of Political Research, 59:2, 376–96.

- Roberts, Kenneth M. (2022). ‘Populism and Polarization in Comparative Perspective: Constitutive, Spatial and Institutional Dimensions’, Government and Opposition, 57:4, 680–702.

- Rokkan, Stein (2000). Staat, Nation und Demokratie in Europa: Die Theorie Stein Rokkans aus seinen gesammelten Werken rekonstruiert und eingeleitet von Peter Flora. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- Sartori, Giovanni (1976). Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Singer, Matthew M. (2016). ‘Informal Sector Work and Evaluations of the Incumbent: The Electoral Effect of Vulnerability on Economic Voting’, Latin American Politics and Society, 58:2, 49–73.

- Spittler, Marcus (2018). ‘Are Right-Wing Populist Parties a Threat to Democracy?’, in Wolfgang Merkel and Sascha Kneip (eds.), Democracy and Crisis: Challenges in Turbulent Times. Basel: Springer International Publishing, 97–121.

- Steiner, Nils. D., and Christian W. Martin (2012). ‘Economic Integration, Party Polarisation and Electoral Turnout’, West European Politics, 35:2, 238–65.

- Tarrow, Sidney (2021). Movements and Parties. Critical Connections in American Political Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Theocharis, Yannis, Shelley Boulianne, Karolina Koc-Michalska, and Bruce Bimber (2022). ‘Platform Affordances and Political Participation: How Social Media Reshape Political Engagement’, West European Politics, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2087410

- Traber, Denise, Lukas F. Stoetzer, and Tanja Burri (2022). ‘Group-Based Public Opinion Polarisation in Multi-Party Systems’, West European Politics, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2110376

- Van der Brug, Wouter, Gianni D’Amato, Didier Ruedin, and Joost Berhout (2015). The Politicisation of Migration. London: Routledge.

- Wagner, Markus (2021). ‘Affective Polarization in Multiparty Systems’, Electoral Studies, 69, 102199.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, and Rens Vliegenthart (2019). ‘Protest and Agenda-Setting’, in Frank R. Baumgartner, Christian Breunig, and Emiliano Grossman (eds.), Comparative Policy Agendas: Theory, Tools, Data. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 260–70.

- Walter, Stefanie (2021). ‘The Backlash Against Globalization’, Annual Review of Political Science, 24:1, 421–42.

- Wang, Tianjiao, and Fei Shen (2018). ‘Perceived Party Polarization, News Attentiveness, and Political Participation: A Mediated Moderation Model’, Asian Journal of Communication, 28:6, 620–37.

- Wessels, Bernhard, and Hermann Schmitt (2008). ‘Meaningful Choices, Political Supply, and Institutional Effectiveness’, Electoral Studies, 27:1, 19–30.

- Wilford, Allan M. (2017). ‘Polarization, Number of Parties, and Voter Turnout: Explaining Turnout in 26 OECD Countries’, Social Science Quarterly, 98:5, 1391–405.

- Zollinger, Delia (2022). ‘Cleavage Identities in Voters’ Own Words: Harnessing Open-Ended Survey Response’, American Journal of Political Science, 1–48.