Abstract

The willingness of voters on the losing side to accept electoral outcomes – losers’ consent – is essential to democratic legitimacy. This article examines the role of emotions in shaping people’s perceptions of electoral fairness, arguing that voters on the losing side who feel angry are less willing to accept democratic outcomes. This is examined in the context of the 2016 Brexit referendum, as well as the 2019 UK general election, using original survey data and an experiment in which specific emotional responses (anger and happiness) are induced to test the causal effect of emotions. The results show that losers who felt angry about an electoral outcome are less likely to accept the legitimacy of the democratic process and that anger has a causal effect in reducing losers’ consent. These findings suggest that politicians may be able to influence voters’ faith in democracy by mobilising emotional responses.

For democracies to govern effectively, and survive in the long term, people who find themselves on the losing side of a vote must accept both the outcome of the election and the policies implemented by the winners. This acceptance has become known as ‘losers’ consent’ (Anderson et al. Citation2005; Easton Citation1975; Nadeau and Blais Citation1993). While it is easy for winners to be satisfied with election outcomes, the greater challenge is for those on the losing side to recognise that outcome as the product of a fair democratic process. Without such ‘gracious losers’, the democratic process as a whole is called into question after every electoral contest. This undermines trust in democratic institutions and the overall legitimacy of electoral democracy. Yet even in established democracies, some voters on the losing side question the legitimacy of outcomes, especially when the electoral contest is polarised. One example of a highly divisive and polarised electoral context is the 2016 Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom. This gave rise to long-lasting concerns about the fairness of the referendum among many voters on the losing side. Over half of the people who voted to remain in the European Union (EU) continue to think that the decision to leave was not based on a fair democratic process.Footnote1 This has had enduring negative effects on political trust and contributed to affective polarisation (Hobolt et al. Citation2021).

Why are some people on the losing side willing to recognise the legitimacy of democratic outcomes, but others are not? In this article, we focus specifically on the role of emotions in shaping losers’ consent at the individual level. We argue that emotions are critical to understanding why some losers endorse the outcome of an electoral contest, while others remain convinced that the election was rigged in some way against their side. We know from a large literature in political psychology that emotions are powerful determinants of political beliefs and actions (Huddy et al. Citation2007; MacKuen et al. Citation2010; Valentino et al. Citation2008; Webster Citation2020). Drawing on that literature, we argue that losers’ consent is easier for those ‘less emotionally engaged in the debate’ (Nadeau et al. Citation2021: 91). In particular, we argue that anger is likely to undermine losers’ consent since angry people tend to cling more tightly to their prior convictions and are also much less receptive to new information or opposing points of view (Brader and Marcus Citation2013; Vasilopoulou and Wagner Citation2017; Weber Citation2013). In essence, angry losers are both less ready to accept the possibility of defeat being real, but are also more open to in-group arguments that the electoral process was rigged.

While an association between emotions and losers’ consent has been suggested (see Anderson et al. Citation2005: 25–26), it has rarely been tested. One important exception is the recent paper by Nadeau et al. (Citation2021) which shows that ‘graceful losers’ (losers who accept the election result) are less angry than ‘sore losers’ (losers who do not accept the result). However, the direction of causality is unclear: is anger causing people to withhold their consent or are ‘sore losers’ simply angry about the result? We directly address this question of whether anger explains why some people are more likely to perceive electoral outcomes as unfair in two electoral contests in the UK: the 2016 EU referendum and the 2019 general election. This allows us to examine how emotions shape individual-level perceptions of the democratic process in both a highly polarised referendum context and in a general election.

First, we use observational survey data to demonstrate that those who felt angry about the specific electoral outcome are less likely to accept the legitimacy of the democratic process. In line with Nadeau et al. (Citation2021), we find a strong correlation between anger and a lack of losers’ consent in both electoral contests. Nonetheless, these correlations do not allow us to establish whether it is anger causing a shortfall of losers’ consent or whether it is simply that ‘sore losers’ become angry about the result. Therefore, to test the causal effect of emotion, we run an experiment embedded in a nationally-representative survey. In the experiment, we induce specific emotional responses (anger and happiness) to examine the causal effect of emotions on losers’ consent. Our experimental findings provide evidence that anger can cause a loss of faith in the democratic process.

These results have important implications for the understanding of the fragility of democracy and political trust, particularly during times of heightened polarisation. Ideologically polarised voters tend to be angry voters, which suggests that greater polarisation can affect losers’ consent via greater levels of anger. Equally, it is possible that politicians, especially those with more populist tendencies whose rhetoric is more likely to emphasise anger (Widmann Citation2021), may be able to influence people’s emotional responses to an electoral outcome (Gervais Citation2019; Stapleton and Dawkins Citation2022) and thereby undermine voter faith in the legitimacy of the democratic process.

Losers’ consent and emotions

Losers’ consent is crucial to the functioning of democracies. It is well established that democracies are more stable when those on the losing side accept that elections have been resolved in a legitimate fashion (Anderson et al. Citation2005). Losers’ consent captures the notion that ‘the viability of democracy depends on its ability to secure the support of a substantial proportion of individuals who are displeased with the outcome of an election’ (Nadeau and Blais Citation1993: 553). Losers’ consent is thus essential to representative democracy. Without it, every election represents a potential challenge to the political system as a whole, since the losers of the election will be unwilling to accept legal and institutional processes. One way in which we see a general consequence of ‘sore losers’ in political systems is in their satisfaction with democracy. People who vote for parties forming the government express higher satisfaction with democracy when compared to those who supported parties that enter opposition (Anderson and Guillory Citation1997; Blais and Gélineau Citation2007; Bowler and Donovan Citation2002; Henderson Citation2008; Listhaug et al. Citation2009; Singh et al. Citation2011). Similar findings emerge when it comes to trust in specific political institutions (Anderson and LoTempio Citation2002; Anderson and Tverdova Citation2001).

Referendums in this context are especially interesting. There are winners and losers in all democratic contests, but the gap between winners and losers is particularly stark in referendums. While referendums tend to decide significant constitutional issues with lasting consequences, they do not provide the scheduled opportunity for a re-run that voters are familiar with in an ordinary electoral cycle (Hobolt Citation2009; Hobolt et al. Citation2022). There is little hope for the losing side in a referendum of reversing the outcome and the majority decisions reached by direct democracy have been criticised as an unchecked ‘tyranny of the majority’ with little regard for the minority (Butler and Ranney Citation1978; Gamble Citation1997; Lijphart Citation1999). While governments in representative democracies derive their legitimacy from regular free and fair elections, referendums are typically sporadic one-off events. Nobody likes being on the losing side, but being a loser is likely even harder when there are no clear procedures in place to overturn an electoral outcome and when, as with Brexit, the campaign and outcome give rise to deeply held political identities (Hobolt et al. Citation2021; Hobolt and Tilley Citation2022). Yet, while there is some excellent work on how emotions affect the process of choosing a side in the run up to a referendum (Garry Citation2014; Vasilopoulou and Wagner Citation2017), we know much less about losers’ consent in the aftermath of referendums. In this article, we therefore look at losers’ consent in the context of both election and referendum outcomes.

We are not, however, interested primarily in aggregate levels of losers’ consent, but rather in individual-level differences: why are some losers more discontented than others to the point of contesting the legitimacy of an electoral outcome? Much of the literature has argued for a rational utilitarian approach to explaining differences in levels of consent. This assumes that winners’ greater satisfaction with democracy is primarily instrumental: they expect that their winning party will implement their preferred policies and that makes them more satisfied with democracy. If that is the case, then different political and institutional contexts may explain differences in consent. In particular, winner-take-all electoral contests, such as referendums or elections in presidential and majoritarian elections, should produce more ‘sore losers’ than contests in proportional and consensual systems where losing parties are likely to have more policy influence (Anderson and Guillory Citation1997; Anderson and Mendes Citation2006; Anderson and LoTempio Citation2002; Anderson and Tverdova Citation2001; Anderson et al. Citation2005; Moehler Citation2009). At the individual-level, the same approach can explain why losers who are at a greater ideological distance from winners are more likely to be ‘sore losers’ (Anderson et al. Citation2005; Esaiasson Citation2011; Ezrow and Xezonakis Citation2011).

The other approach has been to focus more on political identities and how they influence consent. The key individual level explanation here is thus rooted in social psychology and relates to the strength of political in-group attachments. On this account, being part of the political majority provides psychological benefits that are not driven simply by instrumental policy considerations. Similarly, those on the losing side whose political identity is more central to their lives may become embittered and discontented with the system as a whole when that side is defeated (Anderson and LoTempio Citation2002; Anderson et al. Citation2005). Effectively, voters with stronger attachments to the losing party are more likely to interpret the result through their partisan lens and are therefore less able to accept victory of the out-group party.

This social identity approach hints at another difference between people that might affect the granting of losers’ consent: their emotions. While some work has pointed out that being on the winning side generates a positive feeling and defeat produces negative emotions (Anderson et al. Citation2005; Esaiasson Citation2011; Singh et al. Citation2011), there are few systematic empirical studies of emotion in this context. One exception is Nadeau et al. (Citation2021), who demonstrate that losers who were angry about the result of the 2016 Brexit referendum were more likely to be ‘sore losers’ than those who were happy about the result. Yet the causal direction of this correlation is unclear. Do emotions cause losers’ consent? It seems likely that they do, given that emotions generally affect political behaviour and attitudes (Marcus and MacKuen Citation1993; Nadeau et al. Citation1995; Neuman et al. Citation2007). Specifically, discrete emotions, such as anger and enthusiasm, influence how people deal with threats, how they form preferences, and how they seek out, process and use information (Brader and Marcus Citation2013). We argue that one discrete emotion, anger, is likely to affect responses to an electoral defeat. Specifically, we expect anger to increase the likelihood that voters on the losing side withhold their losers’ consent. There are three reasons to expect this pattern.

First, anger has been shown to depress information seeking. This means that angry people consume less countervailing political information and are more likely to support emotionally framed political positions (Huddy et al. Citation2007; Redlawsk et al. Citation2007; Suhay and Erisen Citation2018; Valentino et al. Citation2008). For example, in his study of how emotions affect people’s assessment of political facts, Weeks (Citation2015) shows that anger exacerbates the influence of partisanship and makes participants more susceptible to party-consistent misinformation. This builds on work in psychology which shows that people induced to feel angry generally process information more superficially, take shortcuts to arrive at decisions and make judgements about other people more easily (Tiedens Citation2001). This all implies that angry losers are less open to factual information about political events, especially information which contradicts their preconceptions, and more receptive to partisan narratives about why a defeat is illegitimate.

Second, anger makes people more committed to their in-group and less conciliatory. This is related to the fact that angry people tend to cling harder to their pre-existing positions, but it is also due to the relationship between anger and a willingness to ‘respond in a hostile manner towards people and ideas that undermine them’ (Suhay and Erisen Citation2018: 797). Unsurprisingly given this, MacKuen et al. (Citation2010) argue that anger decreases people’s willingness to consider policy compromises and Webster (Citation2020) shows experimentally that anger reduces generalised trust in government. In the context of losers’ consent, this all means that angry losers may be less compromise-oriented, less trusting and, ultimately, less likely to consent to their defeat.

Third, anger tends to encourage greater participation in politics (Huddy et al. Citation2007; Valentino et al. Citation2011; Weber Citation2013). As anger heightens perceptions of control, it makes people more likely to think they are politically efficacious. At the same time, it tends to facilitate adversarial participation rather than deliberative engagement. In the context of an electoral defeat, this would suggest that angry losers are more politically active, but also more adversarial in their defence of the in-group and less likely to consent to that defeat.

In summary, we therefore hypothesise that anger is negatively correlated with losers’ consent, whereas the contrasting emotion of happiness is positively correlated with losers’ consent. Moreover, we expect that at least part of that correlation is due to the fact that anger has a negative causal effect on losers’ consent. We thus also hypothesise that people on the losing side who are induced to feel angrier will perceive the electoral process as more unfair.

Hypothesis 1: For people on the losing side, anger is negatively correlated with perceptions of fair electoral process, while happiness is positively correlated with perceptions of fair electoral process.

Hypothesis 2: People on the losing side with an induced increase in anger will perceive electoral processes to be less fair compared to people with an induced increase in happiness.

Methods and data

We combine observational survey analysis with an experimental design in order to test this argument. In order to test hypothesis 1, we use data from an original survey of a nationally representative sample of the British electorate collected in July 2020 in partnership with YouGov. The dependent variable is a question designed to elicit perceptions of unfairness in the election process and thereby the withholding of losers’ consent. We asked respondents about their perceptions of the 2016 EU referendum and the 2019 general election as follows:

Regardless of whether you think it was right or wrong to vote to leave the European Union, do you think that the decision to leave was based on a fair democratic process?

[Yes, it was based on a fair democratic process; No, it was not based on a fair democratic process; Don’t know]

Regardless of how you voted in the general election last December, do you think that the result was based on a fair democratic process?

[Yes, it was based on a fair democratic process; No, it was not based on a fair democratic process; Don’t know]

Our key independent variables are measures of emotion. We measure anger using a 0-10 scale which asks about people’s feelings towards political events. For the EU this reads as follows:

How do you feel about the fact that Britain has now left the EU?

[0–10 scale labelled: Not at all angry (0) to Extremely angry (10)]

How do you feel about the fact that Britain now has a Conservative government?

[0–10 scale labelled: Not at all angry (0) to Extremely angry (10)]

Finally, our models also include important control variables that are highly likely to affect perceptions of electoral unfairness: support for the winning side. For the EU referendum we measure people’s actual vote choice in 2016 (as measured on previous surveys by YouGov) and whether people now had a different view (here the question is: ‘In hindsight, do you think Britain was right or wrong to vote to leave the European Union?’). Given the close proximity of the December 2019 general election to our survey in 2020, we simply control here for respondents’ 2019 general election vote choice.

Hypothesis 2 concerns the causal relationship between emotion and losers’ consent. We use an experimental design in which people are randomly assigned to four groups. We ask people in groups 1 and 2 to reflect on a situation that has made them angry and those in groups 3 and 4 to reflect on a situation that has made them happy. The happiness condition can be considered as either the opposite of the anger condition or as a type of control condition which gives people a similar task. We then measure perceptions of electoral unfairness for those on the losing side of the referendum (groups 1 and 3) or election (groups 2 and 4). This survey experiment was run separately from the survey used to test hypothesis 1, but was also conducted by YouGov on a nationally representative sample of the British electorate in July 2020. There are three main elements to the experimental design. First, we identify ‘losers’. We define general election losers as those who voted Labour in 2019 and referendum losers as those who voted Remain in 2016 and have not subsequently changed their mind (again using the ‘in hindsight’ question as above).

Second, we stimulate emotions. There are various techniques used to do this in a survey or laboratory setting. Subjects can be asked to look at images or videos which provoke emotional reactions, look at faces which are displaying particular emotions, read out loud emotionally charged statements (typically increasing in intensity of the charge), think about a particular scenario designed to be emotion inducing, or describe and reflect on their own emotional state in a situation specific to them (Albertson and Gadarian Citation2016; Searles and Mattes Citation2015). Our design uses the last of these. This is particularly useful in a survey experiment setting as it is relatively quick and we are able to evaluate compliance to some extent by looking at the descriptions provided. It also allows subjects to reflect on specific situations which make them happy or angry, rather than generic images, videos or scenarios which affect the average person’s emotional state. It is a similar strategy to Valentino et al. (Citation2008, Citation2009), but we aim to induce emotions which are unrelated to a particular political event. In terms of the instructions to subjects, we used a modified version of the approach used by Lerner and Keltner (Citation2001) and Webster (Citation2020). Groups 1 and 2 were asked to ‘briefly describe three things, or three situations, that make you feel the most angry’. Respondents were then given three boxes to fill with free text. After that, they were then asked:

Could you describe in more detail a situation which has recently made you feel angry? It is okay if you don’t remember all the details, just be specific about what exactly it was that made you angry and what it felt like to be angry. If you can, write your description so that someone reading it might even feel angry. We are not concerned with grammar or how well you can write, just your feelings.

Third, we measure whether our stimulus affects the consent that losers extend to electoral outcomes. To do that we use the same questions as in the cross-sectional data. Groups 1 and 3 were asked whether they thought that after the EU referendum ‘the decision to leave was based on a fair democratic process’ and groups 2 and 4 were asked whether they thought that the result of the 2019 general election ‘was based on a fair democratic process’. We also include a manipulation check and ask people at the end of the questionnaire to report their anger and happiness about the political event in question. Again, we replicate the questions in the cross-sectional data. Consequently, we asked people in group 1 and 3 to report how angry and happy they were about ‘the fact that Britain has now left the EU’ and people in groups 2 and 4 how angry and happy they were about ‘the fact that Britain now has a Conservative government’.

Results

Are emotions associated with losers’ consent?

In the first part of this section, we present two logit regressions which use the cross-sectional data. These predict perceptions of the electoral process, separately for the EU referendum and the general election, for all respondents. Dissatisfaction with the process, a withholding of consent, is coded as 1. The independent variables in these models are measures of people’s winner/loser status and their emotional state in terms of their levels of anger and happiness.

and show the results for the two electoral contests. In both cases being a winner or loser is a very strong predictor of one’s subsequent view of the fairness of the referendum or election. Leavers think the referendum was fairer than Remainers and Conservative voters think the general election was fairer than Labour voters. This is not surprising. More interesting are the effects of emotions. In both cases greater levels of anger are associated with greater perceptions of unfairness and greater levels of happiness with greater perceptions of fairness. All these effects are statistically significant at the 5 per cent level.Footnote4 They are also large effects, especially for anger. If we just take Remainers and Labour votersFootnote5 and look at the percentages who think the referendum or general election was unfair, the relationships are clear. Overall, 66 per cent of Remain voters thought the referendum was unfair, but this rises to 85 per cent for Remainers who were very angry (scored 9-10 on the scale) and falls to 43 per cent of Remainers who were less angry (scored 0-5 on the scale). Similarly, 59 per cent of Labour voters who were very angry (9-10 on the scale) thought the general election was unfair, but only 17 per cent of Labour voters who scored 0-5 in terms of anger had perceptions of unfairness. This matches Nadeau et al.’s (Citation2021) findings who also examine the association between emotions and losers’ consent in the Brexit referendum. Given that their data comes from 2016 and ours from 2020, this shows the longevity of the Brexit referendum division in Britain and probably reflects the new embedded political identities of Leavers and Remainers (Hobolt et al. Citation2021).

Table 1. Logit regressions predicting perceptions of unfair process: EU referendum.

Table 2. Logit regressions predicting perceptions of unfair process: general election.

Anger and happiness are clearly correlated with perceptions of the fairness of both elections and referendums. Angry losers extend less consent than happy losers. Emotions are thus an important correlate of losers’ consent. Nonetheless, it is far from clear that emotional states cause losers’ consent. After all, if you think that the outcome is unfair, it might make you angry about that outcome. As Anderson et al. (Citation2005: 25) put it: ‘losing leads to anger and disillusion while winning makes people more euphoric’. This relationship remains interesting to those who study the consequences of high or low levels of losers’ consent, but it tells us little about when losers’ consent will be granted by electorates. Whereas if emotions cause losers’ consent, we can predict that angry campaigns will likely lead to lower levels of consent and people who are innately angrierFootnote6 will be more likely to be sore losers. In order to adjudicate between these two situations, we use a survey experiment in which we induce emotions and thus test directly whether anger reduces losers’ consent.

Do emotions cause losers’ consent?

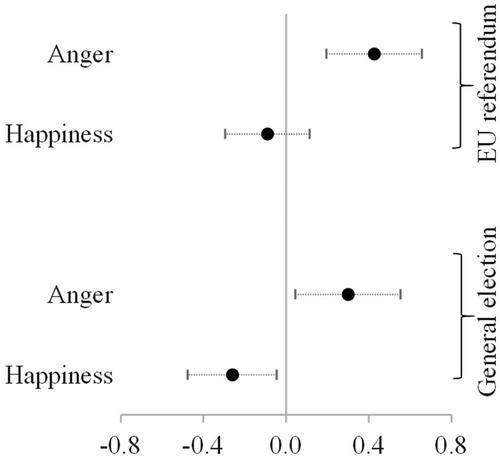

Before turning to the effects of the treatment on losers’ consent in our survey experiment, it is worth discussing how our treatment affects anger and happiness about political outcomes. shows the marginal effects of treatment from OLS regressions which predict anger and happiness on 0–10 scales about the referendum outcome and general election outcome. Included in the models are previous vote, current vote intention and treatment, where treatment means being in the anger induction group relative to being in the happiness induction group. The full models are in online appendix 2. Three of the four effects of treatment are statistically significant – being asked to think about an angering event makes you angrier and less happy about politics than thinking about a happy event. In that sense our treatments worked: we successfully changed people’s emotional states about politics by inducing general emotions.

Figure 1. The effect of emotion treatments on levels of anger and happiness at political outcomes.

Note: Marginal effects of treatment on anger/happiness scales shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals. Anger/happiness scales are 0–10 in which 0 is not at all angry/happy and 10 is extremely angry/happy.

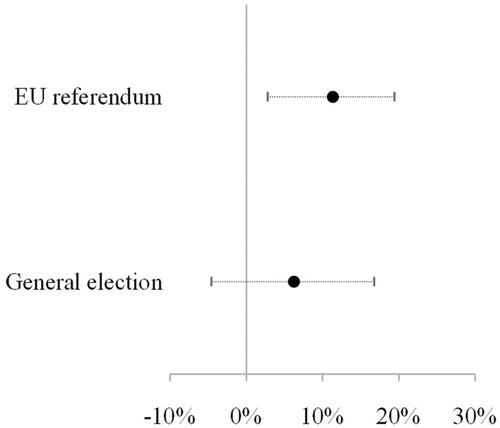

What of losers’ consent? The effects of the treatment on losers’ consent can be straightforwardly displayed. shows the difference between the two treatment groups in the percentage of losers (that is people who voted for the losing side and have not subsequently changed to the winning side) who think the referendum or general election was unfair. The difference between the anger and happiness groups is over 11 per cent for the referendum and statistically significant at the 1 per cent level. The difference for the general election is 6 per cent, although this is not statistically significant.

Figure 2. The effect of emotion treatment (anger versus happiness) on perceptions of unfair process by people on the losing side.

Note: Effect of treatment on the perceived unfairness of the democratic process with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Given the brief, and apolitical, nature of our treatment, these are quite large effects. Clearly they also have implications for how we view the relationship between emotions and losers’ consent. If people’s changing emotional states affect the giving of losers’ consent then that means that we can identify (1) types of people who are less likely to be gracious losers (angry people) and (2) types of rhetoric and campaigns which are less likely to generate gracious losers (angry campaigners and campaigns). Both of these claims are implicit in some of the writing around losers’ consent, but there is little correlational and no causal evidence of them. and provide further evidence of the correlation and provides the first steps in the direction of showing a causal relationship running from emotion to consent.

Conclusion

Lack of losers’ consent can undermine faith in democratic processes and institutions. In the aftermath of the Brexit referendum a majority of Remain voters continued to question the legitimacy of the process and outcome. It is notable that the debate, both during and after the vote, was highly emotionally charged (Osnabrügge et al. Citation2021; Umit and Auel Citation2020) which raises the question of how emotions shape losers’ consent among voters. Our study has focused on the role of emotions in explaining why some voters on the losing side accept outcomes while others do not. In line with our expectations, we find that people who feel angry are less likely to display losers’ consent and that this correlation is at least partially driven by the fact that anger causes people to become ‘sore losers’.

Our study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, we build on the political psychology literature to present an argument for why losers’ consent is driven not only by instrumental considerations, but also emotions. Second, we present a systematic empirical investigation of the role of emotions, combining survey analysis with an innovative experiment that induces emotions to test their causal effect on losers’ consent. While previous literature has suggested that emotions play a role, this study presents the first evidence of a causal effect of emotions on losers’ consent. Of course, perceptions of unfairness may also cause emotions, but our evidence suggests that it is at least a reciprocal relationship in which anger is causing people to withdraw their acceptance of the electoral outcome. Finally, we examine this in two electoral contexts – the 2016 Brexit referendum and the 2019 general election – and show that emotions are associated with differences in perceptions of electoral fairness in both contexts. While it is difficult to make inferences about the impact of context when looking at just two cases, it may be that the more divisive and winner-takes-all nature of the referendum explains why the effect of anger on losers’ consent appears greater in this context compared to the general election context.Footnote7

Thinking about the Brexit vote specifically, the lack of losers’ consent among Remainers several years after the referendum illustrates the potentially corrosive effect of referendums on trust in democratic institutions. It is likely that the institutional context has contributed to the lack of losers’ consent following the Brexit referendum. Not only did the binary nature of the referendum ballot mean that complex policy problems were reduced to a stark either/or choice (Bowler and Donovan Citation2002; Rose Citation2019), but the mandate to exit the EU provided little specific guidance as to the final political settlement (Hobolt et al. Citation2022). In such an open-ended high-stakes vote, it is perhaps not surprising that many on the losing side continue to question the fairness of the process that led to Brexit.

More broadly, our findings chime with the intuition that democratic resilience may depend on ideological polarisation at both the voter and elite level. At the voter level, we know that political anger is related to both ideological sorting (Webster and Abramowitz Citation2017) and social sorting (Mason Citation2015, Citation2018; Webster Citation2020). Societies with more polarised electorates will thus find themselves with angrier voters who are less likely to accept electoral outcomes for which they did not vote. Equally, we know that ideologically polarised elites display greater anger in their rhetoric (Webster Citation2021) and that angry and uncivil language by politicians affects voters’ own emotions (Clayton et al. Citation2021; Gervais Citation2019; Stapleton and Dawkins Citation2022). This means that elite anger can produce voter anger, which can in turn create democratic dissatisfaction. The intentionality of this is unclear, however. On the one hand, losing parties and politicians might intentionally use anger to make their supporters discontented to the point of contesting the legitimacy of an electoral outcome and the democratic institutions themselves. On the other hand, it could be much more unintentional: for example, the actions and rhetoric of winning politicians might anger voters on the losing side and create losers’ discontent. Either way, given the potential importance of anger in causing voters to withhold losers’ consent, future research should examine more closely the role of political elites, and political processes, in inducing such emotions.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (434 KB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the special issue editors, Waltraud Schelkle, Argyrios Altiparmakis, Joseph Ganderson and Anna Kyriazi, for their encouragement and very helpful comments. We would also like to thank Tarik Abou-Chadi, Chris Bickerton, Miriam Sorace, Stefanie Walter, Anthony Wells as well as the SOLID workshop participants and the anonymous West European Politics reviewers for their insightful suggestions about earlier versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

James Tilley

James Tilley is a Professor of Politics at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of Jesus College, Oxford. His research focuses on public opinion and political behaviour. He has written two books: The New Politics of Class (co-authored with Geoff Evans, 2017, OUP) and Blaming Europe? (co-authored with Sara Hobolt, 2014, OUP). [[email protected]]

Sara B. Hobolt

Sara B. Hobolt is the Sutherland Chair in European Institutions and a Professor in the Department of Government, London School of Economics and Political Science. She has written five books on European politics, most recently Political Entrepreneurs: The Rise of Challenger Parties in Europe (co-authored with Catherine De Vries, 2020, PUP). [[email protected]]

Notes

1 58 per cent of respondents disagreed with the statement that the Brexit referendum was based on a fair democratic process. Question wording: ‘Regardless of whether you think it was right or wrong to vote to leave the European Union, do you think that the decision to leave was based on a fair democratic process?’ (YouGov, February 2022).

2 Our measures differ, therefore, from work which uses a single scale with happiness and anger at each end (for example, Nadeau et al. Citation2021). In practice, this probably makes little difference, but theoretically it is more satisfying to allow people to be neither angry nor happy as they are not necessarily always conflicting emotions.

3 To avoid any doubt, the first was an example of a happy experience, the second an angry experience.

4 We also measured two other emotional states (on the same 0–10 scales) towards the EU referendum: anxiety and sadness. While we might see these as related ‘negative emotions’ they are distinct from anger (Huddy et al. Citation2007). When all three negative emotions, alongside happiness, are included in a model, anger and happiness remain statistically significantly associated with perceptions of unfairness. Anxiety is also statistically significantly associated with higher levels of democratic dissatisfaction, but this effect is smaller than for anger and happiness. Sadness, holding constant the three other emotions, is not statistically significantly associated with dissatisfaction.

5 Few ‘winners’ perceive any unfairness. Only 2 per cent of Conservative voters thought that the election was unfair and under 2 per cent of people who voted Leave, and would still vote Leave, thought that the referendum was unfair.

6 Some losers are likely to be angrier than others due to their temperament and commitment to their side. Using separate data gathered in March 2021, it is clear that personality traits, identity strength and ideological values correlate with the anger of losers. Labour partisans and Remainers high in the big five trait of neuroticism, low in the big five trait of agreeableness and high in the dark triad trait of narcissism are generally angrier. Labour partisans and Remainers who are more attached to their identity and have more extreme ideological positions (so more pro-EU and less patriotic for Remainers and more economically leftwing and less patriotic for Labour partisans) are also angrier on average. The full models are in online appendix 1.

7 It is worth noting, however, that this may not be due to more strongly held Brexit identities compared to partisan identities. As the tables in online appendix 4 show, anger appears to have a slightly greater effect on the strength of partisan identities.

References

- Albertson, Bethany, and Shana Kushner Gadarian (2016). ‘Did That Scare You? Tips on Creating Emotion in Experimental Subjects’, Political Analysis, 24:4, 485–91.

- Anderson, Christopher J., André Blais, Shaun Bowler, Todd Donovan, and Ola Listhaug (2005). Losers’ Consent: Elections and Democratic Legitimacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Anderson, Christopher J., and Christine A. Guillory (1997). ‘Political Institutions and Satisfaction with Democracy: A Cross-National Analysis of Consensus and Majoritarian Systems’, American Political Science Review, 91:1, 66–81.

- Anderson, Christopher J., and Andrew J. LoTempio (2002). ‘Winning, Losing and Political Trust in America’, British Journal of Political Science, 32:2, 335–51.

- Anderson, Christopher J., and Silvia M. Mendes (2006). ‘Learning to Lose: Election Outcomes, Democratic Experience and Political Protest Potential’, British Journal of Political Science, 36:1, 91–111.

- Anderson, Christopher J., and Yuliya V. Tverdova (2001). ‘Winners, Losers, and Attitudes about Government in Contemporary Democracies’, International Political Science Review, 22:4, 321–38.

- Blais, André, and François Gélineau (2007). ‘Winning, Losing and Satisfaction with Democracy’, Political Studies, 55:2, 425–41.

- Bowler, Shaun, and Todd Donovan (2002). ‘Democracy, Institutions and Attitudes about Citizen Influence on Government’, British Journal of Political Science, 32:2, 371–90.

- Brader, Ted, and George E. Marcus (2013). ‘Emotion and Political Psychology’, in Leonie Huddy, David O. Sears, and Jack S. Levy (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 165–204.

- Butler, David, and Austin Ranney, eds. (1978). Referendums: A Comparative Study of Practice and Theory. Washington DC: American Enterprise Institute for Policy Research.

- Clayton, Katherine, Nicholas T. Davis, Brendan Nyhan, Ethan Porter, Timothy J. Ryan, and Thomas J. Wood (2021). ‘Elite Rhetoric Can Undermine Democratic Norms’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118:23, e2024125118.

- Easton, David (1975). ‘A Re-Assessment of the Concept of Political Support’, British Journal of Political Science, 5:4, 435–57.

- Esaiasson, Peter (2011). ‘Electoral Losers Revisited – How Citizens React to Defeat at the Ballot Box’, Electoral Studies, 30:1, 102–13.

- Esaiasson, Peter, Mikael Gilljam, and Mikael Persson (2012). ‘Which Decision-Making Arrangements Generate the Strongest Legitimacy Beliefs? Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment’, European Journal of Political Research, 51:6, 785–808.

- Esaiasson, Peter, Mikael Persson, Mikael Gilljam, and Torun Lindholm (2019). ‘Reconsidering the Role of Procedures for Decision Acceptance’, British Journal of Political Science, 49:1, 291–314.

- Ezrow, Lawrence, and Georgios Xezonakis (2011). ‘Citizen Satisfaction with Democracy and Parties’ Policy Offerings’, Comparative Political Studies, 44:9, 1152–78.

- Gamble, Barbara S. (1997). ‘Putting Civil Rights to a Popular Vote’, American Journal of Political Science, 41:1, 245–69.

- Garry, John (2014). ‘Emotions and Voting in EU Referendums’, European Union Politics, 15:2, 235–54.

- Gervais, Bryan T. (2019). ‘Rousing the Partisan Combatant: Elite Incivility, Anger, and Antideliberative Attitudes’, Political Psychology, 40:3, 637–55.

- Henderson, Ailsa (2008). ‘Satisfaction with Democracy: The Impact of Winning and Losing in Westminster Systems’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 18:1, 3–26.

- Hobolt, Sara B. (2009). Europe in Question: Referendums on European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hobolt, Sara, Thomas Leeper, and James Tilley (2021). ‘Divided by the Vote: Affective Polarization in the Wake of the Brexit Referendum’, British Journal of Political Science, 51:4, 1476–93.

- Hobolt, Sara B., and James Tilley (2022). ‘British Public Opinion towards EU Membership’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 85:4, 1126–50.

- Hobolt, Sara B., James Tilley, and Thomas Leeper (2022). ‘Policy Preferences and Policy Legitimacy after Referendums: Evidence from the Brexit Negotiations’, Political Behavior, 44:2, 839–58.

- Huddy, Leonie, Stanley Feldman, and Erin Cassese (2007). ‘On the Distinct Political Effects of Anxiety and Anger’, in W. Russell Neuman et al. (eds.), The Affect Effect: Dynamics of Emotion in Political Thinking and Behavior. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 202–30.

- Lerner, Jennifer S., and Dacher Keltner (2001). ‘Fear, Anger, and Risk’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81:1, 146–59.

- Lijphart, Arendt (1999). Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Listhaug, Ola, Bernt Aardal, and Ingunn Opheim Ellis (2009). ‘Institutional Variation and Political Support: An Analysis of CSES Data from 29 Countries’, in Hans-Dieter Klingemann (ed.), The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 311–32.

- MacKuen, Michael, Jennifer Wolak, Luke Keele, and George E. Marcus (2010). ‘Civic Engagements: Resolute Partisanship or Reflective Deliberation’, American Journal of Political Science, 54:2, 440–58.

- Marcus, George E., and Michael B. MacKuen (1993). ‘Anxiety, Enthusiasm, and the Vote: The Emotional Underpinnings of Learning and Involvement during Presidential Campaigns’, American Political Science Review, 87:3, 672–85.

- Marien, Sofie, and Anna, Kern (2018). ‘The Winner Takes It All: Revisiting the Effect of Direct Democracy on Citizens’ Political Support’, Political Behavior, 40:4, 857–82.

- Mason, Liliana (2015). ‘“I Disrespectfully Agree”: The Differential Effects of Partisan Sorting on Social and Issue Polarization’, American Journal of Political Science, 59:1, 128–45.

- Mason, Liliana (2018). Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Moehler, Devra C. (2009). ‘Critical Citizens and Submissive Subjects: Election Losers and Winners in Africa’, British Journal of Political Science, 39:2, 345–66.

- Nadeau, Richard, Éric Bélanger, and Ece Özlem Atikcan (2021). ‘Emotions, Cognitions and Moderation: Understanding Losers’ Consent in the 2016 Brexit Referendum’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 31:1, 77–96.

- Nadeau, Richard, and André Blais (1993). ‘Accepting the Election Outcome: The Effect of Participation on Losers’ Consent’, British Journal of Political Science, 23:4, 553–63.

- Nadeau, Richard, Richard G. Niemi, and Timothy Amato (1995). ‘Emotions, Issue Importance, and Political Learning’, American Journal of Political Science, 39:3, 558–74.

- Neuman, W. Russell, George E. Marcus, Ann N. Crigler, and Michael MacKuen (2007). The Affect Effect: Dynamics of Emotion in Political Thinking and Behavior. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Osnabrügge, Moritz, Sara B. Hobolt, and Toni Rodon (2021). ‘Playing to the Gallery: Emotive Rhetoric in Parliaments’, American Political Science Review, 115:3, 885–99.

- Redlawsk, David P., Andrew J. W. Civettini, and Richard R. Lau (2007). ‘Affective Intelligence and Voting: Information Processing and Learning in a Campaign’, in W. Russell Neuman et al. (eds.), The Affect Effect: Dynamics of Emotion in Political Thinking and Behavior. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 152–79.

- Rose, Richard (2019). ‘Referendum Challenges to the EU’s Policy Legitimacy – and How the EU Responds’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:2, 207–25.

- Searles, Kathleen, and Kyle Mattes (2015). ‘It’s a Mad, Mad World: Using Emotion Inductions in a Survey’, Journal of Experimental Political Science, 2:2, 172–82.

- Singh, Shane, Ignacio Lago, and André Blais (2011). ‘Winning and Competitiveness as Determinants of Political Support’, Social Science Quarterly, 92:3, 695–709.

- Stapleton, Carey E., and Ryan Dawkins (2022). ‘Catching My Anger: How Political Elites Create Angrier Citizens’, Political Research Quarterly, 75:3, 754–65.

- Suhay, Elizabeth, and Cengiz Erisen (2018). ‘The Role of Anger in the Biased Assimilation of Political Information’, Political Psychology, 39:4, 793–810.

- Tiedens, Larissa Z. (2001). ‘The Effect of Anger on the Hostile Inferences of Aggressive and Nonaggressive People: Specific Emotions, Cognitive Processing, and Chronic Accessibility’, Motivation and Emotion, 25:3, 233–51.

- Umit, Resul, and Katrin Auel (2020). ‘Divergent Preferences and Legislative Speeches on Brexit’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 30:2, 202–20.

- Valentino, Nicholas A., Vincent L. Hutchings, Antoine J. Banks, and Anne K. Davis (2008). ‘Is a Worried Citizen a Good Citizen? Emotions, Political Information Seeking, and Learning via the Internet’, Political Psychology, 29:2, 247–73.

- Valentino, Nicholas A., Antoine J. Banks, Vincent L. Hutchings, and Anne K. Davis (2009). ‘Selective Exposure in the Internet Age: The Interaction between Anxiety and Information Utility’, Political Psychology, 30:4, 591–613.

- Valentino, Nicholas A., Ted Brader, Eric W. Groenendyk, Krysha Gregorowicz, and Vincent L. Hutchings (2011). ‘Election Night’s Alright for Fighting: The Role of Emotions in Political Participation’, The Journal of Politics, 73:1, 156–70.

- Vasilopoulou, Sofia, and Markus Wagner (2017). ‘Fear, Anger and Enthusiasm about the European Union: Effects of Emotional Reactions on Public Preferences towards European Integration’, European Union Politics, 18:3, 382–405.

- Weber, Christopher (2013). ‘Emotions, Campaigns, and Political Participation’, Political Research Quarterly, 66:2, 414–28.

- Webster, Steven W. (2020). American Rage: How Anger Shapes Our Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Webster, Steven W. (2021). ‘The Role of Political Elites in Eliciting Mass-Level Political Anger’, The Forum, 19:3, 415–37.

- Webster, Steven W., and Alan I. Abramowitz (2017). ‘The Ideological Foundations of Affective Polarization in the US Electorate’, American Politics Research, 45:4, 621–47.

- Weeks, Brian E. (2015). ‘Emotions, Partisanship, and Misperceptions: How Anger and Anxiety Moderate the Effect of Partisan Bias on Susceptibility to Political Misinformation’, Journal of Communication, 65:4, 699–719.

- Widmann, Tobias (2021). ‘How Emotional Are Populists Really? Factors Explaining Emotional Appeals in the Communication of Political Parties’, Political Psychology, 42:1, 163–81.