Abstract

This article examines the rare phenomenon of mainstream Euroscepticism that has characterised the British Conservative Party and asks whether a similar pattern has appeared elsewhere in the EU. The study traces the long-term evolution of salience and positions on the EU issue in the manifestos of a heterogenous set of centre-right parties, paying particular attention to whether Brexit or successive EU crises have had some noticeable effect. The thesis of Tory exceptionalism is largely supported by the findings – no other mainstream conservative party in the EU has talked more, and more negatively, about the EU over a long time period. Most other centre-right parties were part of the permissive consensus on the EU and have supported, more or less openly, the integration project throughout the past 30 years. However, some parties of mainstream conservatism have shown a similar negative shift as British Conservatives did in the 2000s, such as the Austrian ÖVP, the Hungarian Fidesz, the Polish PiS and (marginally) the Dutch VVD. Being in opposition or pressured by radical right challengers does not necessarily make the mainstream right more critical of the EU. Internal organisational developments (i.e. the ascent of more Eurosceptic influences within the party) constitute the most convincing proximate explanation for mainstream Euroscepticism on the right.

The aim of this article is to examine the prospect of a Tory scenario playing out in continental Europe – that is, a mainstream party going down a route of profound Euroscepticism, like the British Conservatives, which eventually led to the UK’s exit from the EU. Unlike most centre-right parties in Europe, whose pro-European attitude is a fundamental pillar of their policy, the Conservative Party’s exceptionalism was their relatively unique stance of open hostility towards the EU (e.g. Startin Citation2015). The question is whether or not other mainstream right parties could go also down a similar path, especially in the post-Brexit era.

This is not a trivial question because in many ways centre-right parties hold the key to the escalation of Euroscepticism and any future departures. EU integration was initiated by the centre-right, and the Christian Democrats have played a key role in pushing the European project forward (e.g. Kaiser Citation2007). The European People’s Party has been the largest group in the European Parliament and has shaped EU policies for decades. Consequently, a shift away from this supportive stance could have immensely destabilising consequences for the EU. This is particularly the case when given that mainstream parties are often able to form governments, and are therefore able to actually implement their agenda (unlike their more radical challengers). Even though party-system position is not an accurate indicator of Euroscepticism on its own (Vasilopoulou Citation2013), nonetheless right-wing ideology and Euroscepticism have a close affinity (Marks and Wilson Citation2000); for example, when it comes to the defence of national sovereignty on matters such as immigration. Therefore, the EU issue has been the source of intense ideological and strategic pressures, which has increased the temptation of the mainstream right to go down the Eurosceptic path.

While the Conservative Party’s persistent Euroscepticism is seen as a British phenomenon, an earlier study also detected tendencies of mainstream Euroscepticism in Scandinavia, France, and Poland (Ray Citation2007). The Conservatives could well have been a precursor of a broader centripetal tendency – after all, the continental centre-right faces similar challenges as those faced by the British Conservatives. Moreover, Brexit itself could have unleashed disintegrative dynamics, morphing into a genuine membership crisis for the EU. In this study, we use manifesto data to track the share and trends of Euroscepticism among centre-right parties in the EU, and attempt to locate differences and similarities in the evolution of salience and positions on the EU, as well as their substantive content. We seek to determine whether the Conservative Party was always exceptional in its Euroscepticism compared to its centre-right peers and whether any of those parties have veered towards the Conservative Party’s direction.

We demonstrate that the Conservative Party has indeed been exceptional: it has talked more, and more negatively, about the EU compared to any other similar party on the continent. It has also done so for a notably longer period, at least since the mid-1990s, which is when our analysis begins. Nonetheless, our study stresses that despite the gradual mainstreaming of Euroscepticism that has been registered at least since the euro crisis (Brack and Startin Citation2015), most continental centre-right parties continue to be pro-EU – when talking about Europe, this is done on mostly, or often exclusively, positive terms. The caveat is the salience of Europe in these parties’ programmes, which has remained on consistently low levels and only on rare occasions have we registered isolated spikes of positive attention. The most likely candidates for a Tory scenario can be found in Eastern Europe (i.e. the Hungarian Fidesz and the Polish PiS), where the mainstream right has morphed into radical national conservatism, and among some Frugals (i.e. the Dutch VVD and the Austrian ÖVP). Nevertheless, none of them, at least until now, demonstrate the broad Euroscepticism of the Conservative Party, which spanned a wide range of policy areas and targeted the EU polity itself, which suggests that those parties might be following a different Eurosceptic path.

What is it that puts a mainstream right party on an increasingly Eurosceptic trajectory? We examine three answers to this question that are derived from the extant literature: government/opposition pattern, competitive pressures from the far right, and (changes in) leadership and organisation. We find limited evidence for the assumption that a Eurosceptic shift is driven by government and opposition dynamics because (alternations in) the parties’ role does not neatly mirror this shift. The influence of far-right challengers is more plausible as an explanation, although the relationship is difficult to convincingly demonstrate. In some instances, mainstream right parties are pushed by more radical challengers towards increased Euroscepticism, but at other times they seem to jump on their own. As we shall show, internal organisational developments (i.e. the ascent of more Eurosceptic influences within the party) constitute the most convincing proximate explanation for mainstream Euroscepticism on the right.

Putting the Conservative Party’s exceptionalism into perspective: centre-right views on the EU

Historically, Euroscepticism has been a fringe phenomenon, which has concentrated on the ideological extremes and among opposition parties (Ray Citation2007; Sitter Citation2001; Taggart Citation1998). As the Maastricht Treaty ushered in a new era of constraining dissensus (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009), the positions of the mainstream parties of Europe remained largely sympathetic to the EU project, even if this meant losing some of their electoral strength, such as by doing poorly in European elections (Hobolt and de Vries Citation2016). To this long-term transformation was added a series of acute crises that hit the EU, which were initiated by the Great Recession of the late-2000s (Brack and Startin Citation2015; Zeitlin et al. Citation2019). These developments coincided with, and have fed into, the emergence of challenger parties and the rise of the populist far right (Hobolt and Tilley Citation2016).

Despite countervailing influences, these turbulent short- and long-term dynamics have tentatively eroded the EU’s support among some mainstream right parties, at least in some cases (Abou-Chadi and Krause Citation2021). In this article, we ask if mainstream right parties turned towards Euroscepticism? And, if yes, then where and how? Additionally, we seek to discuss possible explanations for the shifts in the stances of particular parties. Did at least some mainstream right parties follow in the footsteps of the British Conservatives? Do we see the kernels of a similar and rupturing potential among the continental mainstream right? And, which factors might help us understand such a move? Therefore, we want to study whether the passage from a permissive consensus to a constraining dissensus might have shifted the positions of other parties in a dynamic process.

While the Conservative Party has conventionally been viewed as exceptional, the mainstream right across the EU faces very similar challenges and dilemmas as did the British Conservatives. Post-industrialisation has altered traditional party systems, leading to a relative weakening of the mainstream right, although less dramatically than that of social democrats (Gidron and Ziblatt Citation2019; Bale and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2021). The unbundling of conservative attitudes is a major source of the destabilisation of centre-right parties because centre-right voters increasingly hold conservative attitudes on cultural issues but centrist or even progressive attitudes on the economy (Gidron and Ziblatt Citation2019). This increases the likelihood of defection to the radical right (Pardos-Prado Citation2015; Webb and Bale Citation2014).

Additional tensions arise on the EU integration issue. Historically, right-wing support for supranational integration was based, in large part, on the appeal of creating capital-friendly environments. Growing EU-level market regulation, weakening national sovereignty, increased labour mobility from poorer towards richer member states and perceptions of growing bureaucratisation were among the developments that sat uneasily with the mainstream right (Bale and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2021). These transformations constitute the necessary conditions for a Tory scenario, which are present across the continent and could potentially drive mainstream right parties’ positions on the EU to increasingly negative directions.

High(er) salience of EU integration is risky for the mainstream right because electorates tend to hold more unfavourable positions on the EU than do political elites, while support for European integration among the public has, on average, dropped during the latest decade (Ejrnaes and Jensen Citation2019; Hobolt and de Vries Citation2016). Even as many mainstream right voters support the EU because it serves their economic interests and/or reflects their liberal values, a large part of the traditional constituency of the mainstream right is located on the losing side of globalisation and EU integration, harbouring economically and culturally protectionist preferences (Kriesi et al. Citation2006), while others are also strongly opposed to multiculturalism and common immigration management. This attitude correlates with disenchantment with EU integration, at least in Western Europe (Ejrnaes and Jensen Citation2022). These voters are most successfully mobilised by populist radical right (PRR) parties, whose presence could induce strategic movements on the mainstream right, although not on all issues equally. While PRR pressure seems to matter for the issue of immigration, statistical analysis suggests that far-right challengers may push the mainstream towards a more Eurosceptic direction, although the result fails to reach statistical significance (Abou-Chadi and Krause Citation2021; but see: Meijers Citation2017).

Given that mainstream right parties often form governments, this makes a turn towards Euroscepticism generally unlikely (Ray Citation2007). Because governments are directly involved in European policy making, they find it hard to credibly adopt Eurosceptic positions and rhetoric. However, this factor can be countervailed by others, such as electoral pressures and internal party developments. Electoral pressures can materialise in multiple forms. One factor that can lead to both more or less Eurosceptic position is the format of the electoral system, with two-party systems (such as the UK) being prone to more polarisation and extreme positions because the parties might occasionally seek to attract fringe voters who might vote for the radical right. Demand-side pressures can shift parties towards Euroscepticism, even if public opinion in the UK was uniquely hostile to the EU, to a degree that was not prevalent elsewhere in Europe (Gastinger Citation2021; Vasilopoulou Citation2016). However, the public’s tendency was cultivated by the British Conservatives, who were early adopters of mainstream Euroscepticism. Therefore, adoption of Eurosceptic tendencies by other parties might lead to similar phenomena.

In terms of European integration preferences, the formation of broad-based parties that host multiple and often contradictory factions means that there is a higher possibility that the more extreme internal factions occasionally prevail and help shift the party towards more extreme positions, which has recently manifested in multiple countries in Europe (e.g. the UK, Hungary, Austria, etc.). The Tory scenario is instructive here because the intra-party struggle between frontbenchers and Eurosceptic backbenchers has been a key driver of radicalisation (Lynch and Whitaker Citation2018).

In summary, a move towards more Euroscepticism on the mainstream right is overall unlikely, although not altogether impossible. The extent to which parties emphasise the European dimension and the positions they take on the matter is driven by the dynamics of government-opposition competition (Sitter Citation2001), the structure and pressures of political competition and their internal developments. We will return to these factors after discussing our findings on the trends of mainstream right parties.

Finally, not only could similar tendencies have emerged in more nascent forms elsewhere in continental Europe but the end-result of the Conservative’s Euroscepticism, Brexit, may have also been a factor that influenced these trends. On the one hand, Brexit might have reinforced the mainstream right’s support of the EU by presenting an opportunity to renew and recommit to the integration project (e.g. in the form of a more enthusiastic and explicit endorsement of the Union and/or making the positive case for integration to the electorates). On the other hand, Brexit could have also inspired followers among the mainstream right. Which course each party took may depend on their inclinations towards EU criticism, internal factions expressing dissatisfaction towards the EU and the pressures exercised by radical right rivals.

Conceptualisation and measurement

In this section, we present our main concepts that guide this article and use them to draw our cases. Specifically, we focus on our definition of mainstream right and the criteria by which we selected our set of studied parties, the period concerned and finally our conceptualisation of Euroscepticism in line with the existing literature.

Mainstream right

By mainstream we mean parties that tend to adopt centrist and moderate programmatic positions. By right we mean parties espousing an ideology of naturalised social inequalities, which, it is thought, cannot, and probably should not, be eradicated, and which therefore fall outside the purview of the state (Bale and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2021). In a different definition, centre-right parties are those which construct broad voter coalitions that draw support from various right-wing currents as opposed to right-of-centre parties that focus on narrower agendas and constituencies (Gidron and Ziblatt Citation2019: 24). Centre-right parties within our study are ideologically heterogenous but are selected based on their inclusion in the Christian Democrat and Conservative Party families within our manifesto database (see below).

While all mainstream right parties share some baseline similarities, they also differ in important respects, including their attitudes towards EU integration. Christian Democrats have tended to be supportive across the board, but Conservatives have been much less keen on sovereignty transfers, even if they enthusiastically espouse other aspects of EU integration, such as the promotion of free-market economy. In this article, we have selected to study a wide array of centre-right parties, representing various geographic areas of Europe based on three criteria. The first is their affiliation to centre-right groups in the European Parliament. The second is an electorally prominent position in their party-system in the right-wing end of the spectrum that often leads to their participation in government, which enables us to pursue the idea that Euroscepticism might be influenced by government-opposition dynamics. The third is that they should have (started out as) parties of moderate and right-wing ideology that differentiates them from other centre-left, radical right and liberal parties, thus placing them into the Christian Democrat or Conservative family. We include all parties for which longitudinal data exists and add some parties from Eastern Europe for which data only starts approximately in the early-2000s to also cover this area of Europe.

Our sample consists of a subset of mainstream right parties, which are identified according to our criteria of party family, ideology/spatial position in the national party-system and electoral relevance (see ). Our analytical window includes the past 25 years, starting from the mid-1990s (i.e. the onset of the constraining dissensus era), where we consider it most likely to see a burgeoning Euroscepticism, in line with an increasingly hostile public opinion (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009).

Table 1. List of major mainstream right parties included in the analysis.

Euroscepticism

We define Euroscepticism as opposition to (aspects of) European integration. This disapproval can be contingent/qualified and outright/unqualified, or hard and soft (Taggart and Szczerbiak Citation2002). Given that there is currently barely any political party which does not object to some aspect of the EU edifice (Flood Citation2009), and to capture the complexity of the different stances, various typologies of Euroscepticism have been proposed (e.g. Kopecký and Mudde Citation2002; Sørensen Citation2008). Another helpful distinction has been made between the possible targets of opposition, which are the principle, polity, and project of European integration (De Wilde and Trenz Citation2012). We build on these insights, especially in the qualitative analysis of selected manifestos and years. In our quantitative analysis, we treat Euroscepticism as a ‘one-dimensional concept’ (see: Ray Citation2007, 156), which is primarily a matter of differences in degree rather than in kind; that is, parties can be more or less opposed to the EU, in one or more issue areas, and this can shift over time. We are interested in temporal evolution, and we seek to capture the process of hardening (or softening) Euroscepticism. The persistent presence of complaints about Europe, a widening range of the contested policy issues, and increasingly negative issue positions signal a hardening attitude.

To measure stances towards Europe by mainstream right parties, we utilise the MARPOR dataset (Lehmann et al. Citation2022), which is formed of party programmatic documents released at the start of a general election campaign. For the purposes of our study, we focus on two indicators to measure the positive and negative mentions of the EU from centre-right parties in their manifestos. The indicators measure the share of quasi-sentences (i.e. the relative number of coded sentences) related to the EU, positive or negative, within a manifesto, over the total number of sentences. From this initial point, we construct two further indices: one that we denote as the salience of the EU for centre-right parties, which is simply the sum of positive and negative mentions of the EU; and another that we define as the position of centre-right parties, which is the difference between positive and negative mentions of the EU.Footnote1

Tracing positions and issue salience over time and across contexts helps us to identify those parties that are most likely to adopt Euroscepticism and go down the path of the Conservative Party. However, this broad comparison is less well placed to capture the policies they most oppose and the arguments they use to justify these positions. Therefore, in a second step, we zoom into the manifestos of selected parties in key years (Burst et al. Citation2021), undertaking a qualitative content analysis (Mayring Citation2019). Following a close reading of the source material, we compare the emerging perspectives from which the Conservative Party and a selected set of centre-right parties on the continent complained about the EU. We perform this exercise because the pathway to Brexit might have followed a specific set of grievances, but it is equally possible, as suggested by Ejrnaes and Jensen (Citation2022), that there are qualitatively different pathways to a European exit or European discontent in any case. We summarise the major themes in inductively identified categories, which we use for our comparative assessment of the parties.

Findings: the prospects of a Tory scenario in the EU

The evolution of EU-related salience and positions over time

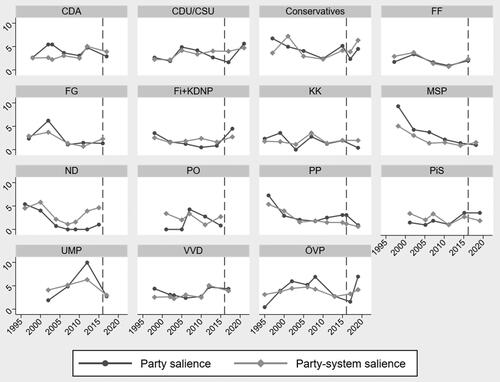

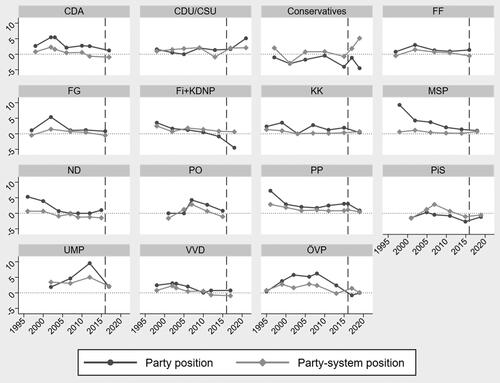

We present the development of the mainstream right parties’ positions and the salience attributed to the EU issue dimension to explore whether the Conservative Party is a deviant case in terms of Euroscepticism or if there are other parties for which the issue was salient and/or took a negative position on it throughout the years. We utilise the MARPOR (manifesto) data from 1995 to 2021, and track the salience and position of those parties in each election (as explained in the operationalisation section). The results are presented in and . In , we measure salience on the y axis as the share of quasi-sentences in manifestos that concern European integration. In , we measure the difference of positive to negative quasi-sentences. Each panel therefore represents a party’s positive or negative stances on the EU (position) and the extent to which it highlights this issue dimension (salience), along with the overall party-system averages. This serves as a benchmark because the divergence of the party-system salience/position and the party-specific salience/position on the EU issue dimension hint at whether centre-right parties are driving the politicisation of Europe or whether there is a different party behind this.

Figure 1. Salience of the EU issue dimension, centre-right parties and party-system averages, Manifesto Project. The dashed line signifies Brexit.

Figure 2. Position on the EU issue dimension, centre-right parties and party-system averages, Manifesto Project. The dashed line signifies Brexit.

In terms of salience, presented in , we record large fluctuations between the different elections, with the party-system and centre-right parties’ averages closely aligned. In terms of positions, presented in , mainstream right parties tend be above the average; that is, they are on the whole more supportive of the EU than most of their competitors. There are only a few exceptions to this rule: the British Conservatives, Fidesz in Hungary and PiS in Poland. In addition, a large decline over time can be observed in the position of the Austrian ÖVP, which since the mid-1990s has been more negative or, at minimum, neutral, towards the EU. This position was upheld in the post-Brexit period. The only exception is the German CSU/CDU, who have become slightly more positive in the 2021 federal elections. The British Conservative Party is unique in terms of both its durably negative position (also vis-à-vis the party-system) and the high salience that it attributes to the EU: their net position is negative for almost all of the elections covered in their manifestos from 1997 to 2019, reaching its peak in the 2019 elections when the issue of finalising Brexit dominated the electoral campaign. There are no other parties for which such a strong and consistent trend exists.

The other parties are not homogeneous. Their only commonality is the starting point: sometime in the 1990s, they were all almost uniformly positive towards the EU, marking the era of permissive consensus. After that initial period, the parties’ positions and salience developed along three distinct paths defining three broad categories. The first is the ever-silent parties (i.e. parties that almost never mention the issue of the EU in their manifestos explicitly and are instead continuing showcasing permissive consensus, supporting the EU as a self-evident part of their policies rather than as an explicit preference). The Irish mainstream right parties, FF and FG, belong to this group because, with a brief exception in 2002, when the election was sandwiched between the two Treaty of Nice referenda, they never mentioned the EU in their manifestos. The Finnish KK, the Polish PO, the Spanish PP, and the Greek New DemocracyFootnote2 (after 2000) also belong to this category.

The second category includes consistent Europhiles (i.e. parties that tend to mention the EU in several of their manifestos and are reliably positive about it). In this category we find the Swedish MSP, and the French UMP and the Dutch CDA, even if any of those parties can also fall into the silent category for some of the elections covered here.

The third category includes those parties that belonged to one of the two latter categories in the past but have turned somewhat negative towards the EU in recent years. The net position of the Hungarian Fidesz and the Polish PiS became negative, while the Austrian ÖVP and the Dutch VVD remain neutral or positive on average, but with a higher incidence of negative mentions of the EU than previously. In particular, ÖVP under Kurz’s leadership has undergone a noticeable departure from its previous enthusiastic Europhilia. Like the British Conservative Party, the positions of PiS and Fidesz are consistently below the party-system average, while in the last couple of elections the ÖVP and the VVD edged close to it. Another distinguishing characteristic of these parties is the relatively high salience that they attribute to the EU in their electoral programmes because for most elections they are close to or above the party-system average.

The salience of the EU seems to be largely supply-driven and context-dependent. What we mean by this is epitomised by the British Conservative Party. Whereas manifesto data showed a relatively consistent trend throughout the years, this was the official line whose implementation changed depending on leadership and context. The Eurosceptic leaderships of Duncan Smith and Hague promoted the issue and members felt they should prioritise the EU in the early-2000s, but their replacement with Howard and then Cameron meant the issue was de-prioritised in the succeeding electoral campaigns, up until it resurfaced around the time of the Brexit referendum announcement again. In hindsight, this may seem paradoxical. However, Cameron’s 2013 pledge for an in-out referendum on EU membership sought, in part, to suppress or at least harness Eurosceptic tendencies to the advantage of the less militant Conservative mainstream (Ganderson and Kyriazi Citation2021). Nevertheless, even in the turmoil following Brexit, Europe was talked about less than when the party leadership was outright Eurosceptic.

The dashed vertical line in and represents the Brexit referendum held in 2016 and implies continuity rather than change, even though the parties taking a more sceptical trajectory also show a small negative tendency appearing right before or after the referendum. While we do not detect signs of major deterioration post-Brexit, we also do not find traces of an attempt to prop up the EU project domestically. The other noteworthy cases are those that talk about the issue contextually, defending the EU at times of crises. For example, during the Euro Area crisis, the positions of both the Greek New Democracy and the German CDU/CSU are higher than the party-system averages, which suggests that the two parties defended the EU against their competitors but also against an ever more sceptical public. Interestingly, in Germany the EU remains a high salience issue for the centre-right from the 2010s onwards, whereas in Greece it receded.

Zooming into the EU dimension in party manifestos

We begin our qualitative manifesto analysis by tracking the Conservative Party’s stances on the EU throughout the years, followed by the programmes of a select group of other parties that we identified as turning sourer on the EU (i.e. the ÖVP, Fidesz, PiS and marginally, the VVD) in key points in time.Footnote3

Starting with the Conservative Party’s manifestos of 2001, 2005 and 2010, we note that large parts are dedicated to Europe. Despite the obvious discontent about the EU, the Conservative position under Hague and Duncan Smith is still subsumed under the ‘in Europe, not run by Europe’ motto (Conservatives 2001). However, the text foreshadows many of the complaints that would later fuel the Leave vote. ‘Red tape’ and bureaucracy appear prominently, and then the transfer of powers from Westminster to Brussels and concerns about an EU army outside the NATO confines (Conservatives 2001). The Conservative Party’s preference was for a flexible Europe, in which member states only adopt legislation that they consider beneficial to them. The seeds of a referendum idea are also included in this manifesto because the Conservatives promise to introduce legislation requiring a referendum for any future power transfers to Brussels (Conservatives 2001), and subsequently promising to hold a referendum on the EU’s (failed) Constitutional Treaty (Conservatives 2005).

All manifestos contain varying issues according to context (e.g. the Treaty of Nice, the Social Charter, the EU Constitution, etc.) but the main problems remained the same: bureaucracy, over-regulation, overreach and unwanted transfer of powers, as well as fraud and misadministration. Nevertheless, the issue was dwindling in centrality, as the manifestos grew longer and the space dedicated to Europe became smaller, especially after Cameron took over. However, the 2010 elections ushered in the influx of a new and overwhelmingly Eurosceptic cohort of Conservative parliamentarians, both in the parliamentary party and in Cameron’s ministerial team (Heppell Citation2013). In 2015, the focus on Europe expanded again qualitatively and quantitatively (Conservatives 2015). The party’s stance was ambivalent but still net positive towards Europe. More pages of the manifesto were devoted to the EU but more topics were included. Promises of European reform were incorporated not only in the pages allocated to discussing the EU specifically but also in other parts of the manifesto. Apart from the continuing claims about cancelling power transfers and regaining sovereignty, a new addition would be the promise to contain and restrict EU immigration, reform the ECHR participation and UK obligations to it, and (again) a promise was made to hold an in/out referendum on EU membership in line with Cameron’s 2013 pledge.

What is noteworthy is that the EU complaints in the last elections prior to Brexit were not contained to sovereignty, regulation, and economic policy more generally, but spilled over to immigration and law and order (i.e. core issues to the Conservative Party’s electorate). Successful reform of these sectors was implicitly linked to the in/out referendum promised on that election. Hence, Tory Euroscepticism across the years was deep and expansive. It was deep because it cast doubt on the fundamentals of the EU as an ever closer union, contesting the transfer of power from member states to the supranational institution. It was expansive because it grew over years: first in terms of expanding opposition to every new integration initiative and second because it finally percolated into other policy areas rather than stand as an issue on its own.

How similar was this trajectory to other parties that have also shown some negative attitudes towards the EU? We base our selection of parties to study here on trend persistence and recent position. The Hungarian Fidesz has the most persistent decline of net position towards Europe and has the most negative position. Fidesz is followed by the Polish PiS, which has also seen a stable trend of negativity towards Europe in the last decade. After this, the ÖVP is studied here because of an accelerating declining trend on its position, leaving the party in a net neutral position towards Europe, followed by the VVD, which charts a similar trend pattern but still retained an overall marginally positive position. We include it with some caution nonetheless because the party under the Rutte leadership has engaged in a noticeable downward trend in its position on Europe, while talking more about it and, more importantly, in ways reminiscent of the ÖVP and the Conservatives (see and ).

Beyond these commonalities of increased salience combined with decreased popularity of the EU, the contents of the negative trends for these parties differ greatly. In the case of Fidesz and PiS, concerns about immigration and the general vision of the EU contrast those of their peers. Conspiratorial elements about population replacement, the de-Christianization of Europe, and the lack of desire of the EU to protect Western civilisation and the Europe of nations are permanent themes. FideszFootnote4 focuses relentlessly on immigration and the government’s resistance of the impositions of ‘Brussels’ (e.g. the migrant relocation scheme). The perspective of PiS on the EU is broader, mentioning the problem in relation to several policy areas in their lengthy manifestos but always from the prism of state sovereignty and national identity: ‘Europe needs neither a cultural revolution nor social engineering. Europe needs normal social relations based on the traditions of the European peoples and Christian culture’ (PiS 2019). In summary, perhaps because Hungary and Poland are net receivers of EU funds, both Fidesz and PiS focus on the non-economic aspects of EU integration, their Euroscepticism reflecting a more general preoccupation of what EU priorities and values should be.

At the other end of the spectrum, the VVD and especially the ÖVP do not mainly follow this line of critique, and sometimes with the PiS chiming in, focus mostly on their grievances with particular EU policies, specifically economic ones. A common theme among all these parties, shared with the Conservative Party, is the abuse of European funds, the bureaucracy inflicted on business by the EU and the burden on the national budget. The VVD manifestos communicate red lines; such as, indicatively, ‘We do not want Europe meddling in our pensions’ (VVD 2017) and ‘The VVD sees nothing in Eurobonds, because this removes the main incentive for problem countries to put their budgets in order and to keep them in order’ (VVD 2012). The idea that EU policies of solidarity create moral hazards is also echoed by ÖVP: ‘It should not be that states like Austria stick to the rules, manage their budget properly and implement reforms, while others get negligently into debt and rely on the help of other states’ (ÖVP 2019). Beyond this, the ÖVP 2019 manifesto is replete with references to subsidiarity, while it calls for downsizing the institutions of the EU. Generally, both the VVD’s and the ÖVP’s main claim against the EU on which they have become more vocal in recent years is the perception that the EU has expanded its reach too far and it should concentrate instead on the fundamentals that work (i.e. the common market and monetary union). Rather than the more civilisational discourse dominating PiS and Fidesz’s manifestos, the Western European parties still support the current Europe but a more barebones version that goes back to the original rationale of plain market integration.

Comparative assessment

In , we summarise the dimensions of Euroscepticism prevalent among this subset of mainstream right parties. We denote a party as negative when it seeks either to bring authority back to the nation state, scale back some of the EU authority, or when it opposes territorial and jurisdictional expansion of the EU. The five dimensions are EU enlargement, deepening (i.e. transferring further power to the EU), economic critique about regulation, fraud and waste, critique about EU migration rules and finally the cultural critique levelled by PiS and Fidesz about how the EU should, but does currently not, act as a bulwark of European civilisation.

Table 2. Dimensions of Euroscepticism among selected centre-right parties.

The parties that we identified as mostly negative about the EU share some characteristics with the British Conservative Party. Specifically, most of them have focussed on economic complaints, the need to cut waste, fight fraud, impose fiscal discipline and abolish over-regulation. They have also recently assumed a negative attitude towards any expansion of EU authority and jurisdiction, converging to a Conservative Party position that was held since the early 1990s. Apart from Fidesz, which has its own idiosyncratic criticism, PiS, ÖVP and VVD have all tended to be negative about any further EU integration that does not revolve around issues such as the climate and migration deterrence. Any further involvement (including integrating military, healthcare or welfare systems) has become explicitly unwelcome by these parties. Their comments about the Euro Area do not focus on potential positive solutions but simply refusing any further involvement of their countries in the problems of others.

Their pathways towards increasing Euroscepticism are not identical. One notable difference between parties is summarised in the last two columns of . The Dutch VVD and the Austrian ÖVP recognise the need for further integration in migration policy. In contrast, the Hungarian Fidesz and the Polish PiS are only willing to discuss border protection and definitely not refugee redistribution, which is a major red flag for both. This is linked to complaints by the Fidesz and PiS that the EU is failing to protect European civilisation from religiously and racially diverse immigrants. Some of this concern is echoed in the other parties’ unwillingness to admit Turkey to the EU under any circumstances. However, the two Eastern European parties adopt a comprehensively alternative vision of the EU. All these parties remained different to the British Conservative Party, who neither spoke about Europe in terms of civilisational identity or as a project that went anywhere beyond a common market.

Overall, it is mostly in the manifestos of the ÖVP, the VVD and partially the PiS that we can situate the most extensive and similar critique to the EU as that applied by the Conservative Party in the past. The difference is one of scale rather than style because they balance this out with more positive mentions of what the EU could potentially provide or become and do not repeat those points as often or as persistently as the Conservatives. In general, the core of the British concerns (i.e. scepticism about the expansion of EU powers, disagreement with the economic model and gripes about the EU’s overreach) are all present. However, these parties do not advocate leaving the EU but simply taking it towards a different direction that is leaner and more liberal. As such, while they quantitatively differ significantly in terms of scale and duration of Euroscepticism to the Conservatives, they showcase seeds of scepticism.

Explaining Eurosceptic trajectories

What may lead a mainstream right party on a Eurosceptic trajectory? In this section, we assess three potential factors for a move towards Euroscepticism of mainstream right parties drawing on the existing literature on party-based Euroscepticism. First, we may suppose that government status lowers the chances of Euroscepticism. As Mair (Citation2009) explains:

Since much of what keeps parties in contemporary European governments busy is Europe itself – negotiating, understanding, transposing – and since Europe has become a very large part of the administration of things, when there is opposition from outside the governing circles it is very likely to take on a Eurosceptic hue. To mobilise against the government in this sense is also to mobilise again Europe, since Europe is, par excellence, the business of government. (Mair Citation2009: 17)

A second factor that influences the Euroscepticism of mainstream right parties are pressure from the radical right, which is the party family’s closest electoral competitor in terms of policy positions and issue ownership (Abou-Chadi and Krause Citation2021). Research has shown that Eurosceptic challenger support can contribute to shifts in mainstream parties’ positions on EU integration and that the mainstream right is susceptible to radical right success (Meijers Citation2017). Notably, in all the countries where we see a tendency towards increased Euroscepticism on the mainstream right, we also find electorally significant radical right parties or currents which also tend to veer Eurosceptic. This fits in the Tory scenario; namely, the idea that Cameron was pressured to politicise EU membership because the British Conservatives sought to see off the challenge of UKIP and the Brexit Party (Hayton Citation2021). Nonetheless, we find mixed evidence for this explanation across our cases. It is perhaps most plausible in the Netherlands, where the VVD moved into the ideological territory of the electorally quite successful radical right, though it has not adopted its extreme policy positions on the EU (Van Kessel Citation2021). In Austria, the ÖVP shifted to a more Eurosceptic position in 2017 when it formed a coalition with the FPÖ, although the coalition agreement between the two parties did not challenge their commitment to European integration but only added qualifiers and demands for reform (Heinisch and Werner Citation2021). Likewise, both the Hungarian Fidesz and the Polish PiS have selectively adopted the positions and narratives of their PRR competitors (Enyedi and Róna Citation2018; Pytlas Citation2021a).

The major weakness of this account is the presence of equivalent competitors in France, Germany, and Southern Europe, where mainstream right parties have not shifted towards Euroscepticism. While the electoral system’s pressure was offered as a tentative explanation for the Conservative Party’s stance because they needed to recollect the votes of potential UKIP voters to enhance their position in their two-party race, we are not certain why the French or Southern European systems, which are also polarised if not exactly two-party systems, would not result in a similar outcome. At best, the pressure from these parties could have lowered the salience of the European issue dimension because mainstream right parties would want to de-emphasise an issue owned by their direct competitors. For this reason, we argue that competitive pressures may play some role, but nonetheless cannot be a sufficient explanation for mainstream Euroscepticism. Moreover, even in the event of hardening mainstream Euroscepticism, it is not clear whether these changes are strategic reactions to radical right parties, whether we observe the autonomous actions of mainstream right parties or whether, and quite plausibly, there is a kind of symbiotic relationship between the two camps (Bale Citation2018).

This takes us to a third potential factor in growing mainstream Euroscepticism that raises the problem of endogenous transformations that accentuate Eurosceptic currents inside the parties. During the long tenure of these parties in government, we observe the growth of their fringe and internal oppositions. For the British Conservatives, the period of the most vehement Euroscepticism coincided with the party’s marginalisation from power. However, it is useful to remember that it was the party’s internal Eurosceptic faction that spearheaded the politicisation of the EU, which undermined Cameron’s effort to suppress the issue of Europe (Gamble Citation2012). As the Tory case shows, the chances for intra-party conflict on the issue of EU integration can actually be higher in government than in opposition because no European government can fully control the EU agenda but they are all tasked with justifying controversial policies and compromises back home (Lynch and Whitaker Citation2013).

While the continental parties might not have such a robust Eurosceptic faction within them as the Conservative Party, their long tenure in power has allowed them to feel less pressured electorally and to freely radicalise their programme accordingly. This suggests a different pathway of Euroscepticism, which juxtaposes the national government to the EU in an effort to bolster support for the former and solidifies their position of power, unperturbed by EU interferences. In particular, Fidesz and PiS have such a tight grip of their countries’ institutions and levers of power that radicalisation on a number of issues poses little threat to them and may actually benefit them electorally. Both Orbán and Kaczyński have been able to maintain full control of the governing parties and to neutralise or marginalise more moderate voices should they emerge (Metz and Várnagy Citation2021; Pytlas Citation2021b). The ÖVP has also shifted towards more extreme positions under Sebastian Kurz, who represented the more hardline faction of the party, aligning himself with a more unapologetic and radicalised emerging right-wing that strayed from the liberal paradigm of the 1990s (Liebhart Citation2022). Although the VVD seems to be the exception, it is worth noting that internal dissent over (also) the EU issue dimension resulted in a rupture in the party, leading to the departure of Geert Wilders in 2004 because he rejected further integration and Turkey’s EU accession (Startin and Krouwel Citation2013). It is difficult to fully assess the importance of endogenous radicalisation here but it is a topic for further research because it seems that it is internal developments and shifts within these parties, rather than competitive pressures or government-opposition dynamics, that are most critical for their shifts on Europe.

Concluding discussion

The starting point of our analysis was the exceptionalism of the British Conservatives as a case of particularly strong mainstream Euroscepticism. We asked whether the peculiar trajectory of the Conservative Party was present elsewhere in continental Europe. After all, mainstream right parties everywhere face similar challenges, including electoral decline, increasingly divided and hostile constituencies over the issue of European integration, and competition from the radical right (Bale and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2021). Some of them were already turning more critical of the EU around the early-2000s (Ray Citation2007). The evolution of the EU polity (i.e. the passage from the era of permissive consensus to constraining dissensus; Hooghe and Marks Citation2009), and the EU’s progressive expansion beyond regulation to the turf of core state powers (Genschel and Jachtenfuchs Citation2014), along with a series of destabilising crises could have provided further impetus towards more Euroscepticism. Moreover, despite countervailing forces, Brexit itself could have led to imitative tendencies, at least in some instances, which would lead to a full-blown membership crisis for the EU.

Our article has shown that this crisis has not (yet) materialised. Mainstream right parties differ in the extent to which they touch on the issue of Europe, some of them being ever-silent, some expressly Europhile and some exhibiting increasing Euroscepticism. However, no other continental mainstream right party has followed in the footsteps of the British Conservatives, even if a similar template of grievances seems to be emerging in some of their discourse. The Conservative Party’s exceptionalism mostly differed in terms of scale and duration: it preceded the era of constraining dissensus and was negative even at a time of a more affirmative or, at minimum, indifferent climate. We did detect some traces of the beginning of such an erosive process among a minority of mainstream right parties but whether it will ever turn into the deep and expansive Euroscepticism of the Conservatives remains an open question. The Conservative Party’s perception of the structural incompatibility of the UK and the EU, and their ideological agony over sovereignty is only faintly echoed by a handful of parties examined here and only in a weaker form. Furthermore, the spill-over that we saw from EU scepticism into policies such as intra-EU migration or crime has not occurred for any other party to the same extent. This suggests that the increasing Euroscepticism that we noted among other European mainstream right parties might not have the same origins or follow the same pathway that led to Brexit but draw power from other sources and lead to other outcomes, such as a push for a more fragmented, market and border protection-focussed EU.

Based on our results, we can draw broader lessons about mainstream Euroscepticism. To begin with, we are able to confirm that mainstream Euroscepticism is rare but possible. We see an amplification of EU criticism among mainstream right parties across very diverse political spaces and contexts of competition. Moreover, mainstream Euroscepticism seems to go beyond purely transactional/instrumental considerations – it is also anchored in a deeper ideological commitment and criticism towards the EU polity. Meanwhile, other factors that are often invoked to understand the Tory scenario, such as radical right pressure or government-opposition dynamics, do not seem to deterministically lead towards a more Eurosceptic trajectory. Radical right challengers are present in countries where the mainstream right has turned more critical of the EU but they are also present in countries where the mainstream right has stood firm in its support for the EU, such as France or Germany. However, the radicalisation of the mainstream right in a handful of EU countries could be a source of Euroscepticism, similar to the discontent that characterised the Conservative Party. Indeed, those parties that move even further to the right also tend to become more negative about the EU, albeit not necessarily in the same terms or with the same grievances.

Finally, while there is no uniform trend towards the exit among the mainstream right, we do not detect an enthusiastic commitment to the EU. Brexit could have presented an opportunity to re-energise the integration project and to make a positive case for the EU, such as was done by the German CSU/CDU and the Greek New Democracy during the Euro Area crisis. However, when confronted with the various tensions related to the EU, the mainstream right normally opts to de-emphasise EU issues or in some cases stress their sourness towards them, unless they are propelled onto the agenda by other means.

Funding

Argyrios Altiparmakis and Anna Kyriazi acknowledge financial support from the research project ‘Policy Crisis and Crisis Politics: Sovereignty, Solidarity and Identity in the EU Post-2008’ (SOLID), funded by an Advanced Grant of the European Research Council (Grant no 810356 ERC-2018-SyG).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Argyrios Altiparmakis

Argyrios Altiparmakis is a Research Fellow at the European University Institute. His research focuses on party politics, political behaviour and the recent European crises. He is currently working on the SOLID-ERC project. [[email protected]]

Anna Kyriazi

Anna Kyriazi is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Social and Political Sciences, University of Milan. Her research focuses on comparative European politics and public policy, migration and political communication. Her articles have appeared in the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, the Journal of European Public Policy, the Journal of Common Market Studies and Electoral Studies, among others. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 Using manifesto data presents distinct advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, parties are much more likely to touch upon the issue of Europe, as the manifesto provides an opportunity to survey the entirety of issues the party wants to take a stance upon. As such, the party’s position should be documented there, even if perhaps presented in a more sophisticated or elegant way than the everyday way its members speak (or do not speak) about the issue of European integration. On the other hand, exactly because the manifesto has no strict space constraints, it does not necessarily portray the priorities of a party in the most transparent way and could also provide a more rounded image of what the party line is on any issue.

2 Manifesto data is not available for the latest general elections held in 2019 in Greece.

3 The texts are available at the Manifesto project website. For this analysis, we downloaded, translated (when necessary), and closely read the relevant programmatic documents. They are listed in the Appendix.

4 Fidesz has not published an electoral manifesto for general elections since 2014. The MARPOR data, and therefore our own qualitative analysis, is based mainly on a compilation of speeches and interviews by the Hungarian Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán.

References

- Abou-Chadi, Tarik, and Werner Krause (2021). ‘The Supply Side: Mainstream Right Party Policy Positions in a Changing Political Space in Western Europe’, in Tim Bale and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (eds.), Riding the Populist Wave: Europe’s Mainstream Right in Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 67–90.

- Bale, Tim (2018). ‘Who Leads and Who Follows? The Symbiotic Relationship between UKIP and the Conservatives – and Populism and Euroscepticism’, Politics, 38:3, 263–77.

- Bale, Tim, and Christobal Rovira Kaltwasser (2021). ‘The Mainstream Right in Western Europe: Caught between the Silent Revolution and Silent Counter-Revolution’, in Tim Bale and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (eds.), Riding the Populist Wave: Europe’s Mainstream Right in Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1–37.

- Brack, Nathalie, and Nicholas Startin (2015). ‘Introduction: Euroscepticism, from the Margins to the Mainstream’, International Political Science Review, 36:3, 239–49.

- Burst, Tobias, Werner Krause Lehmann, Pola Lewandowski, Jirka Matthies, Nicolas Theres Merz, Sven Regel, and Lisa Zehnter (2021). Manifesto Corpus version: 2021-1. Berlin: WZB Berlin Social Science Center.

- Csehi, Robert, and Edit Zgut (2021). ‘“We Won’t Let Brussels Dictate Us”: Eurosceptic Populism in Hungary and Poland’, European Politics and Society, 22:1, 53–68.

- De Wilde, Pieter, and Hans-Jörg Trenz (2012). ‘Denouncing European Integration: Euroscepticism as Polity Contestation’, European Journal of Social Theory, 15:4, 537–54.

- Ejrnaes, Anders, and Mads Dagnis Jensen (2019). ‘Divided but United: Explaining Nested Public Support for European Integration’, West European Politics, 42:7, 1390–419.

- Ejrnaes, Anders, and Mads Dagnis Jensen (2022). ‘Go your Own Way: The Pathways to Exiting the European Union’, Government and Opposition, 57:2, 253–75.

- Enyedi, Zsolt, and Dániel Róna (2018). ‘Governmental and Oppositional Populism: Competition and Division of Labour’, in Stephen Wolinetz and Andrej Zaslove (eds.), Absorbing the Blow: The Impact of Populist Parties on European Party System. Colchester: ECPR Press, 251–72.

- Flood, Chris (2009). ‘Dimensions of Euroscepticism’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 47:4, 911–7.

- Gamble, Andrew (2012). ‘Better off out? Britain and Europe’, The Political Quarterly, 83:3, 468–77.

- Ganderson, Joseph, and Anna Kyriazi (2021). ‘Braking and Exiting: Referendum Games, European Integration and the Evolution of British Euroscepticism’. Paper presented at the 27th International Conference of Europeanists, 21–25 June.

- Gastinger, Markus (2021). ‘Introducing the EU Exit Index Measuring Each Member State’s Propensity to Leave the European Union’, European Union Politics, 22:3, 566–85.

- Genschel, Philipp, and Markus Jachtenfuchs, eds. (2014). Beyond the Regulatory Polity? The European Integration of Core State Powers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gidron, Noam, and Daniel Ziblatt (2019). ‘Center-Right Political Parties in Advanced Democracies’, Annual Review of Political Science, 22:1, 17–35.

- Hayton, Richard (2021). ‘The British Conservatives and Their Competitors in the Post-Thatcher Era’, in Tim Bale and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (eds.), Riding the Populist Wave: Europe’s Mainstream Right in Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 269–89.

- Heinisch, Reinhard K., and Annkina Werner (2021). ‘Austria: Tracing the Austrian Christian Democrats’ Adaptation to the Silent Counter-Revolution’, in Tim Bale and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (eds.), Riding the Populist Wave: Europe’s Mainstream Right in Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 91–112.

- Heppell, Timothy (2013). ‘Cameron and Liberal Conservatism: Attitudes within the Parliamentary Conservative Party and Conservative Ministers’, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 15:3, 340–61.

- Hobolt, Sara B., and E. Catherine de Vries (2016). ‘Public Support for European Integration’, Annual Review of Political Science, 19:1, 413–32.

- Hobolt, Sara B., and James Tilley (2016). ‘Fleeing the Centre: The Rise of Challenger Parties in the Aftermath of the Euro Crisis’, West European Politics, 39:5, 971–91.

- Holesch, Adam, and Anna Kyriazi (2022). ‘Democratic Backsliding in the European Union: The Role of the Hungarian-Polish Coalition’, East European Politics, 38:1, 1–20.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks (2009). ‘A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus’, British Journal of Political Science, 39:1, 1–23.

- Kaiser, Wolfram (2007). Christian Democracy and the Origins of European Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kopecký, Petr, and Cas Mudde (2002). ‘The Two Sides of Euroscepticism: Party Positions on European Integration in East Central Europe’, European Union Politics, 3:3, 297–326.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey (2006). ‘Globalization and the Transformation of the National Political Space: Six European Countries Compared’, European Journal of Political Research, 45:6, 921–56.

- Mair, Peter (2009). ‘Representative versus Responsible Government’, MPIfG Working Paper 09/8.

- Mayring, Philipp (2019). ‘Qualitative Content Analysis: Demarcation, Varieties, Developments’, in Forum: Qualitative Social Research, vol. 20, no. 3, 1–26.

- Meijers, Maurits J. (2017). ‘Contagious Euroscepticism: The Impact of Eurosceptic Support on Mainstream Party Positions on European Integration’, Party Politics, 23:4, 413–23.

- Metz, Rudolf, and Réka Várnagy (2021). ‘“Mass,” “Movement,” “Personal,” or “Cartel” Party? Fidesz’s Hybrid Organisational Strategy’, Politics and Governance, 9:4, 317–28.

- Lehmann, Pola, Tobias Burst, Theres Matthieß, Sven Regel, Andrea Volkens, Bernhard Weßels, and Lisa Zehnter (2022). ‘The Manifesto Data Collection’, in Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2022a. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin Für Sozialforschung (WZB).

- Liebhart, Karin (2022). ‘Right-Wing Populism in Austrian Politics: Traditional and Recent Aspects’, in Simona Kukovič and Petr Just (eds.), The Rise of Populism in Central and Eastern Europe. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 24–38.

- Lynch, Philip, and Richard Whitaker (2013). ‘Where There Is Discord, Can They Bring Harmony? Managing Intra-Party Dissent on European Integration in the Conservative Party’, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 15:3, 317–39.

- Lynch, Philip, and Richard Whitaker (2018). ‘All Brexiteers Now? Brexit, the Conservatives and Party Change’, British Politics, 13:1, 31–47.

- Marks, Gary, and Carole J. Wilson (2000). ‘The Past in the Present: A Cleavage Theory of Party Response to European Integration’, British Journal of Political Science, 30:3, 433–59.

- Pardos-Prado, Sergi (2015). ‘How Can Mainstream Parties Prevent Niche Party Success? Center-Right Parties and the Immigration Issue’, The Journal of Politics, 77:2, 352–67.

- Pytlas, Bartek (2021a). ‘Party Organisation of PiS in Poland: Between Electoral Rhetoric and Absolutist Practice’, Politics and Governance, 9:4, 340–53.

- Pytlas, B. (2021b). ‘From Mainstream to Power: The Law and Justice Party in Poland’, in Aufstand der Außenseiter. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, 401–14.

- Ray, L. (2007). ‘Mainstream Euroscepticism: Trend or Oxymoron?’, Acta Politica, 42:2–3, 153–72.

- Sitter, Nick (2001). ‘The politics of Opposition and European Integration in Scandinavia: Is Euro‐Scepticism a Government‐Opposition Dynamic?’, West European Politics, 24:4, 22–39.

- Sørensen, Catharina (2008). Love Me, Love Me Not…: A Typology of Public Euroscepticism. Brighton: Sussex European Institute.

- Startin, Nicholas (2015). ‘Have We Reached a Tipping Point? The Mainstreaming of Euroscepticism in the UK’, International Political Science Review, 36:3, 311–23.

- Startin, Nick, and André Krouwel (2013). ‘Euroscepticism Re‐galvanized: The Consequences of the 2005 French and Dutch Rejections of the EU Constitution’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 51:1, 65–84.

- Taggart, Paul (1998). ‘A Touchstone of Dissent: Euroscepticism in Contemporary Western European Party Systems’, European Journal of Political Research, 33:3, 363–88.

- Taggart, Paul, and Aleks Szczerbiak (2002). The Party Politics of Euroscepticism in EU Member and Candidate States. Brighton: Sussex European Institute.

- Talving, Liisa, and Sofia Vasilopoulou (2021). ‘Linking Two Levels of Governance: Citizens’ Trust in Domestic and European Institutions over Time’, Electoral Studies, 70:April, 102289.

- Van Kessel, Stijn (2021). ‘The Netherlands: How the Mainstream Right Normalized the Silent Counter-Revolution’, in Tim Bale and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (eds.), Riding the Populist Wave: Europe’s Mainstream Right in Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 193–215.

- Vasilopoulou, Sofia (2013). ‘Continuity and Change in the Study of Euroscepticism: Plus ça Change?’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 51:1, 153–68.

- Vasilopoulou, Sofia (2016). ‘UK Euroscepticism and the Brexit Referendum’, The Political Quarterly, 87:2, 219–27.

- Webb, Paul, and Tim Bale (2014). ‘Why do Tories Defect to UKIP? Conservative Party Members and the Temptations of the Populist Radical Right’, Political Studies, 62:4, 961–70.

- Zeitlin, Jonathan, Francesco Nicoli, and Brigid Laffan (2019). ‘Introduction: The European Union beyond the Polycrisis? Integration and Politicization in an Age of Shifting Cleavages’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:7, 963–76.

Appendix

Programmatic documents used for qualitative content analysis (retrieved from the MARPOR database):

Conservatives (2001): Time for common sense.

Conservatives (2005): Are you thinking what we’re thinking? It’s time for action.

Conservatives (2010): Invitation to Join the Government of Britain.

Conservatives (2015): Strong leadership, a clear economic plan, a brighter more secure future.

Conservatives (2017): Forward together.

Conservatives (2019): Get Brexit done. Unleash Britain’s potential.

Fidesz (2014): Selected speeches of and interviews with Viktor Orbán.

Fidesz (2018): Selected speeches of and interviews with Viktor Orbán.

ÖVP (2019): Unser Weg für Österreich [Our way for Austria].

PiS (2014): Zdrowie, Praca, Rodzina [Health, Work, Family].

PiS (2019): Polski Model Państwa [The Polish state model].

VVD (2012): Niet doorschuiven maar aanpakken [Don’t move on but tackle it]

VVD (2017): Zeker Netherland [The Netherlands safe].