Abstract

Western democracies have an economic interest in admitting immigrants but at the same time they fear the political costs of doing so. A recurring idea to help reconcile this tension is to allow for temporary mobility of immigrants while restricting their permanent settlement. Trying to shed light on this matter, this article studies whether and when liberal democracies design immigration policies that prioritise (temporary) mobility over (permanent) migration. First, the underlying rationale of states for such a mobility preference is identified, before conceptualising the temporal design of immigration policies based on the combination of entry and stay regulations. Second, three theoretical explanations for the variation of countries’ mobility preference are developed: liberal constraints, institutional path-dependence and domestic politics. Third, a comparative analysis tests the arguments by studying the combination of entry and stay regulations in the immigration policies of 33 OECD countries between 1980 and 2010. The results confirm that most liberal democracies have a mobility preference in their immigration policies, but largely confined to labour migration and to a declining degree over the past decades. The temporal design of immigration policies is path-dependent on historical immigration regimes with a tendency towards a lower mobility preference the more countries become familiar with large-scale immigration.

The regulation of international migration has become a salient policy issue in many Western democracies. Their globally integrated economies create a need for the free flow of labour across borders, whereas electoral pressures from domestic politics create demands for immigration restrictions (Hampshire Citation2013; Hollifield Citation2004). Therefore, migration policy making in liberal democracies takes place within competing policy imperatives stemming from the tension between open economies and closed states. This so-called ‘liberal paradox’ has intensified over time with deepening globalisation and the domestic politicisation of migration issues (e.g. Armingeon and Lutz Citation2020).Footnote1 National governments are thus propelled to reap the economic benefits of open borders and at the same time they are keen to preserve national sovereignty and to minimise the political costs of immigration. How do liberal democracies design their immigration policies to manoeuvre this tension?

A recurring idea in this regard is the temporary migration programmes that allow for (short-term) mobility but prevent immigrants’ (long-term) settlement (see Martin Citation2015; Ruhs Citation2006).Footnote2 The objective of such policies is the manipulation of the temporality of migration as a strategic response to cross-pressures from economic labour needs and political restriction demands. Although this idea is anything but new, we have so far a limited understanding of how states design their immigration policies in terms of the temporality of migration. This is the more surprising since the concepts of temporary and permanent migration feature prominently in the immigration policy literature: Scholars have made a distinction between settler nations that conceive of immigration as permanent settlement and guest-worker countries that consider immigration a temporary exception not affecting society in the long-term (Citrin and Sides Citation2008; Freeman Citation1995). These regime types are however historically contingent and focus on migration demographics instead of specific policies. Other scholars have studied the characteristics of temporary migration schemes (e.g. Castles Citation2006; Dauvergne and Marsden Citation2014; Ruhs Citation2006). The previous literature thus analysed the design of immigration policies in terms of temporality either as a historic phenomenon (e.g. guest-worker era) or as specific policy instruments (e.g. recruitment programmes), but not as a general way to characterise and compare immigration policies.Footnote3 In this article, I aim to close this gap with the comprehensive integration of the perspective of temporality into the conceptualisation and analysis of immigration policies. This will then help to generate insights into countries’ strategic migration management: Do immigration policies of liberal democracies have a systematic preference for temporary mobility to permanent immigration? What are the driving factors behind countries’ policy design regarding the temporality of migration?

I address these questions by studying how countries combine regulations on immigrant entry and regulations on immigrant stay. States allow for international mobility based on their entry policies and they allow for the subsequent settlement of immigrants based on their stay policies. The previous literature offers conflicting indications on how the entry-stay mix compares across countries and over time. Large-scale guest-worker schemes established during the economic boom in the post-war period were abolished in the 1970s and declared ‘dead’ at that point (Castles Citation1986). At the same time, immigrants have gained more post-entry rights over time and thereby their perspectives of permanent settlement in the receiving country increased (e.g. Joppke Citation1998). More recently however, the intensifying globalisation and increased domestic politicisation has increased the tension between economic needs and political demands (Ford et al. Citation2015), and temporary migration regained popularity as means to recruit foreign workers (Skeldon Citation2012; Wright and Clibborn Citation2020). Overall, it remains an open question to what degree immigration policies of Western democracies have a built-in preference for mobility to migration and what factors may explain such a preference.

In order to investigate this matter, I proceed in three steps. First, I systematise the idea that liberal democracies have an inherent preference for temporary mobility over permanent migration. Applying this idea of a mobility preference to the design of immigration policies allows me to introduce a novel perspective of temporality into our understanding of how states regulate migration. The combination of entry and stay regulations is proposed as a policy mix that allows countries to shape the temporal nature of international migration. Second, I theorise what factors may explain receiving countries’ policy designs in terms of mobility and migration. Thereby, I identify liberal constraints, institutional path-dependence and domestic politics as drivers for the variation in how countries combine entry and stay regulations. Third, I conduct an empirical analysis of immigration policies in 33 OECD countries between 1980 and 2010. The results confirm the main argument of a mobility preference but also show significant variations across institutional contexts. The findings demonstrate that regulating the temporality of migration is a core element of immigration policies in liberal democracies.

Temporary mobility as an escape from the liberal paradox?

In order to systematise the political rationale for a preference of temporary mobility to permanent immigration, I start with the ‘liberal paradox’: The idea ubiquitous in the immigration policy literature that liberal democracies face difficult policy trade-offs between competing political demands of being open and closed at the same time (Hampshire Citation2013; Hollifield Citation2004; Schultz et al. Citation2021). Capitalist economies are expansive and require the free flow of production factors such as labour. Representative politics and national identity tend to mobilise pressures for restrictive immigration policies. In other words, immigrant-receiving countries are often dependent on ‘unwanted immigration’ (Joppke Citation1998). In this context, governments have a strong motivation to address the economic need for immigrant workers while keeping the political costs of doing so at a minimum.

The motivation for temporary admission of immigrants

An old and recurring idea of resolving the liberal paradox is temporary migration where immigrants are allowed to enter the country but not to stay permanently (see Castles Citation2006; Martin Citation2015 for an overview). Thereby, governments can address domestic labour demands while preventing permanent immigration and the associated costs that they seek to avoid. The existing literature offers a series of considerations to support this rationale referring either to the feared economic burden or cultural concerns related to immigration.

First, temporary immigrants might be conceived to be more beneficial (or less of a burden) for the receiving country. Due to their limited social, economic and political rights, temporary labour migrants constitute an underprivileged immigrant population that is attractive for employers as a cheap and flexible workforce (Carens Citation2013: 124). If migrants gain more rights with a more permanent status, such as the right to change the employer or to move across labour sectors, this cost advantage is significantly reduced and the exploitation of immigrants becomes more difficult (Ruhs Citation2013). Moreover, the precarious status of temporary migrants limits the competition with native workers and should thus be perceived as less threatening to native workers than permanent immigrants. Finally, temporary immigrants may also be less likely to rely on public services of the receiving country as the access to and need for schooling, housing and health care provision typically increases with permanent settlement (Green Citation2004: 33). Permanent immigration may increase the fiscal costs for receiving countries particularly by involving decisions of family reunification and spending old age in the receiving country. In contrast, if immigration is designed to be temporary, receiving countries can export unemployment and other social problems in bad economic times (Afonso Citation2012). In conclusion, we can expect liberal democracies to prefer temporary mobility over permanent immigration to minimise the feared economic burden.

Second, temporary immigrants might also be perceived as a lesser cultural threat as they are conceived to be returning to their countries of origin instead of becoming a part of the receiving society. In this perspective, the presence of temporary immigrants does not alter the social fabric in the long term and there is no need for their inclusion into the receiving society as equal members. This also means that there is no need for public integration efforts or natives’ openness to the integration of immigrants. Restricting settlement allows governments to uphold a paradigm of non-immigration while justifying the presence of foreign workers to a xenophobic citizenry (Piguet Citation2006). In contrast, the permanent settlement of immigrants involves an expansion of their rights and accepting them as equal members of society which is likely to heighten conflicts with the native population. In conclusion, we can expect liberal democracies to prefer temporary mobility over permanent immigration to limit immigrants’ impact on the society and to appease cultural concerns of the native population.

The attractiveness of temporary mobility for governments stems thus from the idea that it may offer a response to countries’ economic needs while also addressing domestic concerns about immigration. Such policies can be conceived as a compromise between the pro-immigration and the anti-immigration camp (Ruhs and Martin Citation2008: 260) by producing the allocational benefits of migration while avoiding its distributional costs (Straubhaar Citation1992). Following this perspective, the liberal paradox between open economies and closed states is handily solved by manipulating the temporality of migration. Consequently, we may expect liberal democracies to have a systematic preference for short-term mobility over long-term migration.

The historical evolution of temporary migration policies

Past policy experiences provide ample indications for a mobility preference in immigration policies of Western democracies. This is particularly the case for the so-called ‘guest-worker’ policies that have been the preferred model to recruit foreign labour for the growing economies after the Second World War (Castles Citation2006; Chin Citation2007). The guest workers were intentionally kept at distance to the native society and enjoyed limited rights in terms of wages and labour market mobility. These policies institutionalised a regime of return migration where immigrant workers were seen as temporary guests and allowed to stay only for the duration of their employment contract. Thereby, immigrants were supposed to arrive only for a limited period, or on a seasonal basis repeatedly for a certain part of the year. To support the aim of preventing foreign workers to take root in the receiving society, recruitment focussed on young single men. Nevertheless, the main objective of preventing permanent settlement has largely failed while creating costly externalities such as social segregation, contributing to the abolishing of guest-worker policies in the 1970s (Castles et al. Citation1984; Hansen Citation2002; Castles Citation2006).

However, also after the official end of guest-worker policies, the duration of stay played a crucial role in the immigration policy debates of Western democracies (see Ellermann Citation2021). The attractiveness of temporary migration schemes has not disappeared but seen a more recent revival with countries introducing new policies for recruiting temporary migrants to fill domestic labour shortages (Skeldon Citation2012; Wright and Clibborn Citation2020). Moreover, states’ interest in the temporary mobility of foreign workers is no longer confined to low-skilled immigrants. Receiving countries increasingly allow for the temporary residence of high-skilled migrants as part of their international commercial relations (e.g. Lavenex and Jurje Citation2014). The mobility of skilled immigrants for the globalised economies with multinational companies, international investments and global supply chains is thereby considered an element of international trade relations rather than a matter of immigration. Hence, both low-skilled ‘guest workers’ and high-skilled ‘expats’ are desired by states for economic reasons, but often not considered immigrants that would settle on a permanent basis and integrate into the receiving society.

Conceptualising the temporality of immigration rules

If countries prefer temporary mobility to permanent migration, we should see this preference being reflected in the design of their immigration policies. Temporality is an important dimension through which states govern their population (see Cohen Citation2018) and all immigrant-receiving states place some significance on the length of stay (Hammar Citation1994: 193). To distinguish policies favouring mobility and policies favouring migration, I rely on the idea of two sequential entrance gates for immigrants: The first admission is immigrants’ entry to the country in terms of border-crossing and regulates access to the territory; the second admission is immigrants’ stay in the country in terms of settlement and regulates access to permanent residence (Hammar Citation1994).Footnote4 Accordingly, we can define the concept of mobility as temporary residence that involves only the passing of the first gate of entry, whereas migration defined as permanent residence involves also the passing of the second gate of stay. Accordingly, the temporal policy design in terms of mobility and migration can be defined based on two different ‘locus operandi’ of immigration policies (see also Helbling et al. Citation2017): The regulations of mobility in terms of cross-border flows are located at the states’ external borders and determine whether an immigrant is allowed to enter the territory. The regulations of migration in terms of settlement are located on states’ territory and determine whether an immigrant is allowed to stay in the country on a permanent basis. Immigration policies can therefore be understood as a combination of external entry regulations and internal stay regulations with each country choosing its immigration policy mix. Assuming that Western democracies depend on foreign labour but are at unease with large-scale immigration, they should prefer temporary mobility over permanent immigration. Hence, we may expect that liberal democracies are relatively permissive in their external entry policies and relatively restrictive in their internal stay policies.

Explaining the immigration policy mix regarding entry and stay

Building on the previous section that developed a conceptual understanding of immigration policies as a mix of entry and stay regulations, I propose in the next step theoretical explanations for how countries combine these two policy dimensions to regulate the temporality of immigration: What are the determinants of countries’ immigration policy mix in terms of the entry and stay of immigrants? In the following, I elaborate on how liberal constraints, institutional path-dependence and domestic politics shape the temporal design of immigration policies.

Liberal constraints of rights-based policy making

A first theoretical approach builds on a neo-institutionalist perspective and the constraining role of rights-based policy making. In liberal states, immigrants are entitled to rights and governments are constrained by constitutional norms and procedures. In this perspective, immigration policies are shaped by institutions of liberal democracy such as the independent judiciary and bureaucracies with their liberal norms of international human rights and non-discrimination. The judiciary is to some extent shielded from political pressures and obliged to the non-discriminatory and universalistic principles of modern law (Joppke Citation1998, Citation2001). Government policies are subjected to the norms and principles of liberal constitutional regimes that tend to limit the leeway for immigration restrictions and that have been instrumental for the expansion of rights to non-citizens (Guiraudon Citation2000). This means that the norms underlying liberal institutions evoke an inclusionary logic and limit the room for policies that aim to prevent the permanent settlement of immigrants. The permanent settlement of guest workers against the initial policy objective has been facilitated by constitutional residence and family rights (Hansen Citation2002; Joppke Citation1998). More recent scholarship considers the role of courts on immigrant rights to be rather moderate (e.g. Bonjour Citation2011). Beyond a direct influence of courts, their institutional power could also prevent policy-makers from proposing anti-immigration laws that may be in conflict with constitutional provisions. Following this reasoning, the mobility preference of immigration policies should depend on the extent of liberal constraints that limit the political discretion in the admission of immigrants.

These liberal constraints are not of the same relevance across different domains of immigration policy. Liberal constitutions and the international law guarantee the right to asylum and the right to family, which constitute two main channels of immigrant admission. For the area of asylum policy, non-majoritarian institutions have been identified as important drivers of the expansion of refugee rights against popular pressures for more restrictive policies (Thielemann and Hobolth Citation2016). Family migration policies are strongly shaped by norms of equal treatment (Bonjour Citation2011). These rights-based provisions for asylum and family migration should make it more difficult for governments to combine liberal entry with restrictive stay. This contrasts with labour migration where countries enjoy considerable discretionary space and are less constrained by liberal norms. Consequently, we should find a mobility preference primarily for labour migration policies, and less for the rights-based admission channels of asylum and family migration.Footnote5 In conclusion, the perspective of liberal constraints suggests that to what degree immigration policies prioritise temporary mobility over permanent migration should depend on their exposure to liberal constraints.

Hypothesis H1: The mobility preference of immigration policies is smaller the stronger the liberal constraints to discretionary policy making.

The institutional path-dependence of immigration regimes

A second theoretical approach to explain how countries combine regulations on the entry and stay of immigrants builds on historical institutionalism suggesting that policies are shaped by legacies of the past (see Hansen Citation2002; Messina Citation2007: 102–5). The idea is that the institutionalisation of policies at a critical juncture constrains subsequent policy making and creates lock-in effects for specific institutional arrangements (Goldstone Citation1998). In the context of immigration policies, scholars have argued that the policy regime that modern states established in response to the experience of large-scale immigration has made it difficult to implement reforms that break with that historical legacy (Freeman Citation2006; Wright Citation2012). To identify such path-dependencies, the literature classifies the policy regimes of immigrant-receiving countries based on their different historical experience with immigration into settler nations (or traditional immigration countries), guest-worker countries (or reluctant immigration countries) and new immigration countries (Cornelius and Tsuda Citation2004; Freeman Citation1995).

The settler nations comprise countries such as the United States or Australia whose foundation and development as nations is closely intertwined with immigration. Large-scale immigration took place during their nation-building process and continued with successive waves thereafter. For this reason, immigration is central to their collective identity and social fabric. Accordingly, the immigration policies of these settler nations were designed to make immigration a routine procedure and a permanent feature of the nation’s development (Freeman Citation2006: 231).Footnote6 The incorporation of immigrants as permanent settlers is part of their national myth and ethnic diversity is celebrated. Moreover, the long experience with immigration should increase public tolerance of immigrants as integral part of society (Freeman Citation1995: 891).

This contrasts with the guest-worker countries in Western and Northern Europe whose modern experience with large-scale immigration occurred only when they had already developed nation states with rigid collective identities. Their strong sense of cultural homogeneity makes them reluctant to the social change brought by immigration (Cornelius and Tsuda Citation2004: 24–39). When these countries were faced with domestic labour shortages after the Second World War, they established temporary migration policies to recruit guest workers to allow for labour migration while leaving the societal demographic unaltered (Castles Citation2006; Ellermann Citation2013; Hammar Citation1985). The dominant view of immigration in these regimes is that of a temporary necessity. Given the structural dependencies on foreign workers, guest-worker countries expanded the permanent settlement rights over time (Castles and Kosack Citation1973: 39) and significant pressure lasted on these countries to acknowledge that they have become countries of immigration (Messina Citation2007: 184). The unintended consequence of permanent immigration has triggered policy-learning and shaped countries’ policy paradigms (Ellermann Citation2015). While we might expect these former guest-worker countries to remain reluctant to large-scale immigration and to have greater barriers to permanent settlement, the post-war experience and new social realities of multicultural societies has institutionalised a new paradigm that permanent immigration is not avoidable (Miller and Martin Citation1982).

The third regime type of new immigration countries is found primarily in the South and East of Europe but also among advanced economies outside of Europe (Cornelius and Tsuda Citation2004; Freeman Citation1995). These are the countries that have been emigration countries during most of the 20th century and only recently experienced growing immigration. They have no shared memory of large-scale immigration that shaped their national identity. Their societies are built on the idea of cultural and ethnic homogeneity and the share of immigrants tends to be low. They lack a salient immigration experience and are for that reason likely to be most reluctant to large-scale permanent immigration. The new immigration countries are therefore expected to have the strongest preference for temporary mobility over permanent migration.

A similar argument of path-dependence has been formulated for the historical legacy of colonialism on immigration policies. The large minority populations resulting from colonialism gradually shaped popular attitudes and scholars have argued that former colonial powers have in consequence become more liberal to immigration than countries without such colonial history (e.g. Breunig and Luedtke Citation2008; Hansen Citation2002; Koopmans and Michalowski Citation2017). The historical ties from long and special relations with colonies are expected to have contributed to the institutionalisation of immigration rights and to have constrained future attempts to prevent permanent immigration.

More recent scholarship has shown empirically that the immigration policies of OECD countries have converged towards more openness over time across all policy dimensions except for border controls (Helbling and Kalkum Citation2018; Schultz et al. Citation2021). On a global level, Boucher and Gest (Citation2018) have identified a convergence towards the ‘market model’ with liberal admission of primarily temporary labour migrants and restrictive naturalisation. To what extent the entry-stay mix of liberal democracies has converged over time or is shaped by institutional path-dependence remains an open question. Following the reasoning of historical institutionalism, we may expect that the legacy of historical regimes that evolved from the (non-)experience with immigration shapes countries’ policy design. The assumption is that the policy arrangement that countries have chosen when experiencing the first large-scale immigration limited the options of subsequent policy-makers and encouraged continuity. Despite variation and possible convergence between countries, we should thus observe systematic differences in the immigration policy mix between different regimes that move along specific trajectories circumscribed by their initial institutionalisation of immigration policies.

Hypothesis H2: The later a nation state has experienced large-scale immigration, the higher the mobility preference of its immigration policies.

The dynamics of domestic politics

A third theoretical explanation of countries’ immigration policy mix in terms of the entry and stay of immigrants is based on the influence of domestic politics. Scholars have advanced the notion that competing economic interests and partisan orientations shape the immigration policy choices of national governments (e.g. Givens and Luedtke Citation2005; Odmalm Citation2011). Following the idea of a ‘liberal paradox’ (see above), we should expect the conflicting imperatives of economic needs and political costs to motivate states to design immigration policies that facilitate mobility at the expense of migration. Following this argument, we would expect that the degree of countries’ mobility preference can be explained by their exposure to these domestic political pressures. This is on the one hand the domestic labour demand that motivates governments to admit more immigrants. Guest-worker policies and other temporary mobility schemes are clearly a response to domestic labour shortages (Castles Citation2006). A high demand for foreign labour should hence be associated with a stronger mobility preference in countries’ immigration policies. On the other hand, the political costs associated with immigration are likely to depend on the political mobilisation of anti-immigration sentiments. The prime actors in this regard are the radical-right populist parties that have gained electoral weight in many Western democracies and pressure governments to get tough on immigration (Lutz Citation2019). Accordingly, the incentive for national governments to give priority to mobility over migration should be stronger the better anti-immigration parties perform in elections. These considerations lead to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis H3a: The stronger the domestic labour demand, the stronger the mobility preference of immigration policies.

Hypothesis H3b: The stronger radical-right populist parties, the stronger the mobility preference of immigration policies.

The universalist values of left-wing parties call for equal rights for immigrants, whereas labour market protectionism suggests restrictive entry rules. These positions are in line with the interests of trade unions that historically favoured restrictive immigration admission in order to prevent supply-driven wage suppression and the fragmentation of organised labour into natives and immigrants (Afonso and Devitt Citation2016: 13–14). While unions have toned down their opposition to immigrant admission over time (e.g. Haus Citation2002), they continue to be more focussed on expanding the rights of migrant workers than on easing admission rules (Caviedes Citation2010). Organised labour and its political representation are thus expected to give priority to rights over numbers. Consequently, we can expect that left-wing parties favour immigration policies that combine restrictive entry regulations and liberal stay regulations.

Right-wing parties favour a liberal labour market aligned with the interests of employers in a cheap and flexible labour force. This aim is supported by the availability of immigrants that only enjoy a limited set of rights and can be hired on short-term contracts.Footnote7 This interest makes it likely that employers give priority to numbers over rights in their immigration preference. Therefore, we can expect that right-wing parties and employer organisations favour immigration policies that combine liberal entry regulations with restrictive stay regulations. Based on these considerations, political ideology and partisan orientation should shape how external and internal dimension of immigration policies are combined and thus to what extent there is a preference for mobility over migration.

Hypothesis H3c: With right-wing parties in power countries have a stronger mobility preference than with left-wing parties in power.

Data and method

The outlined hypotheses on the temporal design of immigration policies are tested with a comparative analysis across 33 OECD countries.Footnote8 This country selection includes advanced economies with different policy regimes and a large variation in their immigration histories. To measure their immigration policies, I use the ‘Immigration Policies in Comparison’ (IMPIC) dataset by Helbling et al. (Citation2017) that provides various immigration policy indices for all OECD countries between 1980 and 2010. Most importantly, the dataset not only allows me to distinguish between external entry policies and internal stay policies, but also to assess them across different admission channels (labour, family, asylum).Footnote9 For each policy dimension the degree of restrictiveness on a scale from zero (most liberal) to one (most restrictive) is coded. More restrictive policies grant fewer rights and freedoms to immigrants than more liberal policies. This structure of the dataset is uniquely suited for the analysis of countries’ immigration policy mix in terms of temporary mobility and permanent migration.

As the main dependent variable, I measure countries’ immigration policy mix in terms of their mobility preference. This is operationalised by the restrictiveness gap between regulations on external entry and on internal stay. Entry regulations are measured with eligibility requirements and conditions as its two sub-indices. Eligibility requirements stipulate which criteria an immigrant has to fulfil to qualify for a certain entry route. These are for example quota rules or age limits. Conditions are the additional requirements that need to be fulfilled to be granted entry such as language skills or labour market tests. Stay regulations are measured with the items ‘security of status’ containing all policies that regulate the duration of permits and access to long-term settlement and ‘rights associated’ containing all policies that govern which rights immigrants receive in regard to access to employment, and how they are monitored once they are within the territory.Footnote10 The security of status sub-index contains rules such as the renewal of a permit or the transition from a temporary to a permanent permit. The associated rights closely relate to settlement such as permit flexibility and rights of employment. For details of the operationalisation based on various sub-indices see Table A1 in the Online appendix. Each indicator measures the policy restrictiveness on a scale from zero to one. To ensure comparability across policy dimensions, a certain isomorphism between the measurement aspects and the numerical properties of the indicators is necessary (see Schultz et al. Citation2021: 771). The design of the IMPIC indicators addresses this challenge by building indicators based on the theoretical range and not the empirical range. Moreover, an indicator has the value of 0.5 if a specific legal provision is present. For these reasons, the IMPIC data is well suited for valid comparisons across different policy-dimensions.

Table 1. Model estimates for domestic politics determinants of countries’ mobility preference.

The mobility preference of countries immigration policies is then calculated as relative restrictiveness by subtracting the restrictiveness of stay policies from the restrictiveness of entry policies. The resulting variable measures the relative openness of entry policies vis-a-vis stay policies, i.e. to what degree a policy combines liberal entry and restrictive stay. A positive value means that immigration restrictions are concentrated in the internal dimension of stay regulations (preferring mobility over migration). A negative value means that immigration restrictions are concentrated in the external dimension of entry regulations (preferring migration over mobility).Footnote11

A series of further variables operationalise potential determinants of countries’ immigration policies in order to test the hypotheses. First, liberal constraints are captured by different admission channels as well as countries’ extent of judicial constraints on legislation. Following the theoretical elaboration above, immigration policies are separated into the three channels of labour migration, family migration and asylum migration. The immigration policy mix is measured separately for each channel. Judicial constraints are measured by the strength of countries’ judicial review as proposed by Lijphart (Citation2012).Footnote12 The index covers the period from 1980 to 2010 and ranges from one to four taking into account the existence of procedures for judicial review of legislation, the active assertion of this power by courts, and the difficulty to change the constitution. This index captures to what extent courts can invalidate (anti-immigration) legislation and to what extent courts act as policy activists.

Second, to account for institutional path-dependence from immigration experience, I classify the OECD countries into three different immigration regimes following the previous literature: Settler nations are Australia, Chile, Israel, New Zealand, United States and Canada, guest-worker countries are Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, Denmark, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, France, Sweden and the United Kingdom. The remaining countries are classified as new immigration countries.Footnote13 Alternatively, I classify countries based on whether they were significant colonial powers (France, Belgium, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Spain and Portugal) or do not have a comparable colonial past (cf. Koopmans and Michalowski Citation2017). To get more fine-grained variation in countries’ migration context, I also look at their share of the foreign born and their overall immigration policy restrictiveness from the IMPIC dataset.

Third, the forces of domestic politics are measured with the domestic labour demand and the strength of anti-immigration parties. I use the unemployment rate as a proxy for domestic labour demand, and measure the electoral strength of radical-right populist parties with their cumulative vote share at the last national election. Additionally, the political ideology of governments is measured based on whether a cabinet is dominated by left, right or centrist parties.Footnote14 Except for the regime dummies, the domestic politics variables are provided by the Comparative Political Data Set by Armingeon et al. (Citation2018) (for more details on the operationalisation see Table A1 in the Online appendix).

The empirical analysis first provides descriptive evidence for countries’ immigration policy mix in terms of their mobility preference by assessing the variation across countries and over time. I then compare the policy mix across different admission channels to test the predictions of the liberal constraints hypothesis. For that purpose, I employ distributional and correlational measures such as box-plots and bi-variate scatter plots with LOESS (locally estimated scatter plot smoothing) curve lines. The same procedure is used to compare the outcome variable across different immigration regimes and their average trajectories over time as well as the relationship with countries’ immigration policy context. The relative explanatory power of different determinants of countries’ immigration policy mix is then tested with a series of panel regression models. The time-serial cross-sectional nature of the dataset requires accounting for the additional heterogeneity to avoid biased estimates. For this reason, all models include country-clustered standard errors. I estimate separate models for the within-country variation and the between-country variation. The within-models capture the change over time, whereas the between-models capture the variation between countries. In addition, separate models test for convergence (interaction of regime-dummies with a time-trend variable) and path-dependence (interaction of the initial condition, the policy mix in 1980, with a time-trend variable).Footnote15 A series of alternative model specifications and measurements serve as robustness check to assess effect stability.

Results

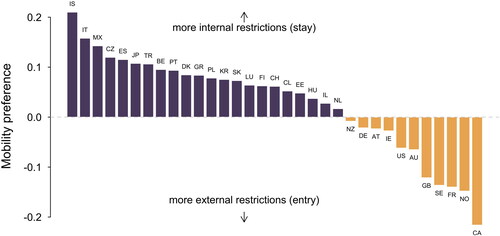

This section presents the empirical findings to test the theoretical hypotheses using immigration policy data of 33 OECD countries. First, I establish descriptive evidence on countries’ mobility preference based on the relationship between external entry policies and internal stay policies. There is a strong correlation of r = 0.83 between entry and stay policies. This suggests that countries tend to have similarly liberal or restrictive immigration policies in place across the two policy-dimensions.Footnote16 Nevertheless, there is substantial cross-country variation in the restrictiveness gap between entry and stay policies (see ). Two thirds of countries have more liberal entry policies than stay policies in place and only one third is more liberal on stay than on entry. Overall, the stay policies are significantly (p < 0.001) more restrictive than the entry policies. These findings are a first tentative confirmation of the idea that immigration policies in most Western democracies combine liberal entry with restrictive stay.

Figure 1. Empirical comparison of entry and stay policies.

Note: The figure shows the mobility preference of OECD countries as the average over the period of observation. The mobility preference measures how much more liberal entry policies are than stay policies. The bars in violet display a mobility preference and the bars in yellow a migration-preference. Each bar is labelled with the ISO2 country code.

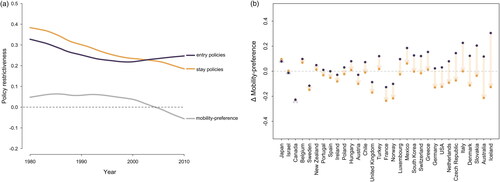

In a next step, I assess how these policies have evolved over time in terms of their restrictiveness. displays the smoothed lines (LOESS) comparing the external entry and the internal stay regulations. Both policy dimensions have become more liberal over time. While stay policies were clearly more restrictive than entry policies in the 1980s, this gap has closed over time and after 2000 the entry policies became more restrictive than the stay policies. This pattern results primarily from the continuous liberalisation of stay policies after 1995 and from entry policies remaining largely stable between the 1990s and 2010. In the most recent period, there is a clear trend towards externalisation of immigration regulations in the sense that immigration restrictions are shifting from the internal to the external dimension. This is confirmed by the evolution of the average mobility preference that has slowly decreased and turned negative after 2005, hence becoming a migration-preference. This means that over time countries became less likely to combine liberal entry with restrictive stay. No country has moved substantially towards a higher mobility preference, but many have reduced their mobility preference to a significant extent. While all countries have liberalised their entry regulations over time, there is a particularly large variation in the extent to which they facilitate permanent settlement of immigrants.

Figure 2. Evolution of the mobility preference over time.

Note: The line plot on the left displays the evolution of the average entry and stay policy restrictiveness as well as the average mobility preference in OECD countries. The lines represent a locally estimated scatter plot smoothing (LOESS, span = 0.2). The plot on the right displays for each country how the mobility preference changed between 1980 and 2010. The arrows display the size of change and the colour the direction of change (violet = change towards higher mobility preference, yellow = change towards lower mobility preference).

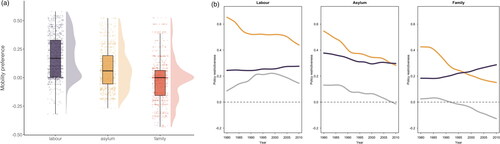

What factors explain the variation in countries’ mobility preference? In the following, I present analyses to test the hypotheses regarding these policy determinants. First, I assess the role of liberal constraints by analysing whether the mobility preference varies across different admission channels. Is the different scope of policy discretion across admission channels reflected in the extent of their mobility preference? A descriptive comparison reveals substantial differences in this regard: While around 94% of OECD countries are more liberal on entry than on stay regarding labour migration, this is only the case for two thirds of countries in asylum migration and less than half of them in family migration (see in the Online appendix). As revealed by the box plots in below, the mobility preference is highest for labour migration and lowest for family migration. The change over time is also distributed unequally across the three admission channels. While the mobility preference has declined for family and asylum migration, it has even increased over time for labour migration and only slightly reversed after the year 2000. Only labour migration policies have a clear and continuous mobility preference. Very few countries have increased their mobility preference for asylum and family, whereas most countries shifted towards higher mobility preference in their labour migration policies (see in the Online appendix). These results provide support for Hypothesis H1 that admission channels with stronger liberal constraints have a lower mobility preference. The institutional feature of judicial constraints (on anti-immigration legislation) does however not explain the cross-country variation in mobility provision (see below and Table A2 in the Online appendix). The slight negative association is the result of Canada as an influential outlier. Right-based policy making hence shapes countries’ entry-stay mix primarily through a differentiation by admission channel rather than an overall constraint on rights restrictions.

Figure 3. Mobility preference across admission channels.

Note: The box plots display the distribution of the mobility preference across the three main admission channels. The line plots display for each admission channel the evolution of the immigration policy restrictiveness in external entry policies and internal stay policies. The lines represent a locally estimated scatter plot smoothing (LOESS, span = 0.2), yellow = stay policies, violet = entry policies, gray = mobility preference. Data from 33 OECD countries.

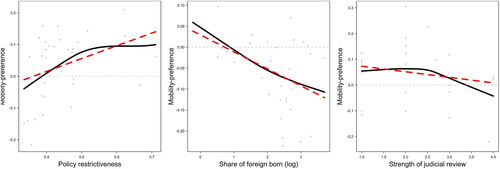

Figure 5. Mobility preference and immigration policy context.

Note: Scatter plots with LOESS-estimate (black line) and OLS-estimate (red dashed line). The plot on the left represents country averages for the period from 1980 to 2010, whereas the plot in the middle and on the right represent only the values from the year 2010.

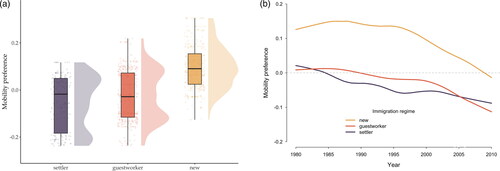

Second, I test the hypothesis that immigration policies are path-dependent and shaped by countries’ historic immigration experience. In , I present a descriptive analysis of how the mobility preference compares across different immigration regimes. The box plots and the LOESS-estimates suggest that settler nations have the lowest mobility preference, followed closely by the guest-worker countries and with the new immigration countries having clearly the highest mobility preference. The estimated averages across the three regime types have declined in parallel over time with only a slight convergence. The regime differences have remained largely stable: After 30 years during which the political context of immigration politics has changed significantly, the differences between historically shaped immigration regimes are still clearly visible. What is more, there is a moderate positive correlation between the initial policy mix and the policy mix in 2010 (r = 0.54). A formal estimation of temporal dynamics confirms a significant path-dependence of the mobility preference based on countries’ initial policy mix and the absence of substantial convergence between regime types (see Tables A3 and A4 and Figure A3 in the Online appendix). This pattern confirms the theoretical expectations and shows that the difference runs primarily between those countries whose societies have been shaped by large-scale immigration in the past (settler nations and guest-worker countries) and those that lack this historical experience (new immigration countries). This pattern is confirmed when controlling for countries’ colonial past that does not lend substantial explanatory power to the variation in mobility preference. These results for the regime type could be strongly influenced by the process of country classification. For this reason, I re-estimate the regime comparison by dropping the more ambiguous cases of Norway, United Kingdom, Ireland and Finland (see in the Online appendix). This sub-sampling results in more pronounced regime differences between guest-worker countries and settler countries in line with the theoretical expectations. These results confirm Hypothesis H2 postulating that countries without a modern experience with large-scale immigration until very recently are most likely to give priority to temporary mobility over permanent migration.

Figure 4. Mobility preference across immigration regimes.

Note: The box plots on the left display the distribution of countries’ mobility preference by immigration regimes. The line plot displays the same variable in terms of evolution over time using LOESS-estimates. Both figures are based on 33 OECD countries.

If immigration history does explain countries’ current combination of entry and stay policies, we should find an association between the mobility preference and countries’ immigration policy context. reveals that the mobility preference is higher the more reluctant countries are to admit immigrants (based on their policy restrictiveness) and that it is lower the higher the immigrant share in a country. The LOESS-lines further demonstrate that these associations are particularly strong among the most restrictive countries and those with the fewest immigrants. This pattern provides further confirmation that the lack of immigration experience that makes countries at unease with the idea of immigrant settlement is an important predictor of whether a country prefers temporary mobility to permanent migration in its immigration policy mix. Finally, the multivariate panel regression model using country-characteristics as determinants confirms the presented results (see Table A2 in the Online appendix). Overall, these analyses suggest that countries’ mobility preference has evolved largely path-dependent based on the legacies from past immigration experience.

These results so far have analysed the cross-sectional variation in countries’ immigration policy mix. In a next step, I look at the determinants of change over time and the explanatory power of domestic politics. How do political and economic pressures shape the evolution of countries’ mobility preference? The panel regression results are presented in below. Neither unemployment nor the political variables of radical-right strength and government ideology exert a significant effect on countries’ mobility preference. The four independent variables explain less than five per cent of the inter-temporal variation in countries’ mobility preference. Both left-wing and right-wing cabinets have a negative coefficient, suggesting that centrist governments are most likely to design immigration policies with a mobility preference. These results for domestic politics hold when using alternative operationalizations of political ideology and alternative model specifications (see Table A5 in the Online appendix).

One might argue that the rights-dimension of internal stay regulations reflects integration policies rather than immigration policies. I therefore rerun the main results by leaving out the rights-dimension and only include the security of stay to calculate countries’ mobility preference. The results are largely similar with the main pattern confirmed. Finally, since policy restrictiveness is measured on a fixed scale from zero to one, the model estimates might be influenced by ceiling or floor effects. I account for such effects by the inclusion of a variable that measures the distance of overall policy restrictiveness to the top or bottom of the scale yielding no substantially different results. The results are hence robust regarding a series of alternative operationalisation, sampling and estimation strategies. The empirical evidence provides thus very limited support for the domestic politics hypotheses. Instead, the mobility preference of countries changes only incrementally over time driven by long-term dynamics rather than short-term partisan politics.

Conclusion

For long, scholars have discussed the idea that competing political pressures motivate states to allow for temporary mobility to realise economic gains while simultaneously limiting permanent migration to prevent an anti-immigration backlash. This article investigates to what extent this motivation is reflected in the design of immigration policies in OECD countries. For that purpose, I conceptualise how states regulate movements in terms of temporary mobility and permanent migration. I argue that the combination of entry and stay policies allows governments to shape the temporality of immigration. While these two aspects are often treated as one dimension, I demonstrate that they have evolved in clearly distinctive ways and their combination has important substantive implications for countries’ immigration policy.

The empirical analysis confirms that liberal democracies tend to be more permissive on the entry of immigrants than on their subsequent stay. From 1980 to 2010 the mobility preference has declined primarily because of more liberal stay policies. To understand this policy variation, I test three theoretical explanations. First, I find that liberal constraints from rights-based policy making explain important variation in the policy mix: The mobility preference is primarily a feature of labour migration policies where governments enjoy considerable discretion, whereas it does appear much less for the admission channels of asylum and family migration with their pronounced constraints from constitutionally guaranteed rights. Second, the entry-stay policy mix evolves largely along path-dependent trajectories determined by countries’ historical experience with large-scale immigration. The lowest mobility preference is found for settler nations where permanent immigration is the default mode. While guest-worker countries tend to have only a slightly stronger mobility preference, it is primarily the new immigration countries that prefer mobility to migration. The combination of liberal entry and restrictive stay seems to be a feature of those countries that are at unease with immigration due to a lack of historical experience with large-scale immigration in their recent past and their rather homogenous societies. Third, the analysis does not find robust evidence for the influence of domestic politics on the immigration policy mix. Short-term fluctuations in domestic pressures or the political orientation of governments seem not to substantially alter countries’ immigration policy design. Overall, the combination of entry and stay regulations follows structural long-term developments and is best explained by countries’ experience with immigration and constraints from liberal institutions.

These findings have implications for the understanding of immigration policies in liberal democracies and advance the literature in several ways. I show that over time the migration restrictions moved from the internal policy dimension towards the external policy dimension. While such an externalisation has been discussed extensively for immigration controls (e.g. Lavenex Citation2006), this result demonstrate that immigration regulations are also subject to an externalisation dynamics. An exception to the externalisation trend are labour migration policies where states have strong interests to allow for mobility and fewer constitutional obligations that prevent them from implementing restrictive stay regulations. Previous research studying immigration policy regimes has mostly highlighted the distinction between settler nations and guest-worker countries. The empirical analysis shows however that the regime differences are primarily found between countries with historical immigration experience and those who lack such an experience. Moreover, while previous research has suggested that different dimensions of immigration policies have strongly converged over time (Helbling and Kalkum Citation2018; Schultz et al. Citation2021), this study suggests that this is not the case regarding the combination of entry and stay policies. However, it will be of interest to observe whether new immigration countries are increasingly converging with old immigration countries the more accustomed they get with being an immigrant-receiving country. The finding of limited influence of partisan politics on immigration policies confirms previous research suggesting that the party composition of governments is of minor importance for immigrant admission in contrast to other dimensions of migration policy (Givens and Luedtke Citation2005; Lutz Citation2019). Despite the contentious and polarising nature of immigration in domestic politics, some core features of the policy regimes seem largely unaffected by these political conflicts.

While this study provides a novel conceptual understanding of temporality in immigration policies and reveals some important empirical patterns, much remains to be done. The results suggest that long-term dynamics shape countries’ policy design. However, the analysis covers only a time period of thirty years and ends in 2010. Further research is thus necessary to assess how the significant policy changes that have been implemented in the time thereafter have shaped the temporality of immigrant admission. This study looks at the design of national immigration regulations, and thereby leaves out other policy elements such as short-term policy instruments or international migration agreements as additional policy layers. Immigration policies are multi-dimensional and future research should pay more attention to the specific policy mix that countries choose to regulate immigration and to reconcile competing policy objectives.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (632.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The article has benefited substantially from generous feedback and comments from participants of research seminars at the University of Geneva, the University of Neuchâtel, the London School of Economics and Political Science as well as the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, and in particular from Loes Aaldering, Paula Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik, Jim Hollifield, Sandra Lavenex, Angelo Martelli, Didier Ruedin, Samuel Schmid, Elisa Volpi, Kristina Weißmüller and Natascha Zaun. Finally, I am grateful to the editors and reviewers for their careful reading of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Philipp Lutz

Philipp Lutz is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and a Visiting Fellow at the London School of Economic and Political Science. His main research interest is in understanding the political consequences of international migration covering comparative politics as well as international governance. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 Note that while public attitudes towards immigration have not become more negative over time (e.g. Dennison and Geddes Citation2019), the politicization of the issue mobilizes primarily anti-immigration voters as they tend to care more about the issue than pro-immigration voters (Kustov Citation2022).

2 There are other strategies that governments might employ to reconcile open economies and closed states such as admission selectivity or tacit acceptance of irregular immigration.

3 For a partial exception, see the comparative case study by Ellermann (Citation2021) discussing the evolution of immigration policy in Germany, Switzerland, the United States and Canada and the role of temporality therein.

4 Hammar (Citation1994) identifies naturalization, the process of becoming citizen, as a third entrance gate. This refers to citizenship policies and is therefore not included in the analysis of immigration policies dealing with the admission of immigrants.

5 While temporary migration schemes are most discussed for labour migration, we can also find elements of various temporality in the case of asylum and family migration policy. In the area of asylum, receiving countries have created subsidiary protection schemes that allow them to grant humanitarian protection only temporarily and send refugees back to their country of origin once their protection need has ceased to exist. In family policy, governments have introduced instruments to revoke residence rights by restricting the provision of autonomous residence to family migrants.

6 Note that settler nations also implemented temporary migration programs such as the Bracero guest-worker scheme in the US or temporary work visa schemes in Canada or Australia (e.g. Wright and Clibborn Citation2020).

7 The preference of employers for a flexible labour force with limited bargaining power might not be uniform as Afonso (Citation2012) convincingly argues but differ between tradable and non-tradable sectors of the economy.

8 List of countries: Austria, Australia, Belgium, Switzerland, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, Germany, Denmark, Greece, Estonia, Spain, Finland, France, United Kingdom, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Iceland, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal Sweden, Slovakia, Turkey and the United States. As the analysis focuses on liberal democracies, some countries are included with a reduced time-series for the time after the end of authoritarian rule (Chile, Czech Republic, Turkey, Estonia, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Turkey).

9 The IMPIC dataset explicitly includes both temporary and permanent migration and only excludes short-term mobility such as commuting and tourism as well as student migration. The IMPIC-reference to temporary migration is equivalent with the mobility-term used in this article.

10 There are N = 35 missing values for internal regulations (Finland, Estonia).

11 The mobility preference is calculated based on the three categories of labour, family and asylum. The fourth category of co-ethnics is left out due to the many missing values and the minor substantial importance. If they are included, the resulting pattern remains unaltered.

12 The index is not available for all OECD countries since Eastern European countries are not included. Data from CPDS (Armingeon et al. Citation2018).

13 Some of the countries are not clear-cut cases. The United Kingdom and Norway were latecomers compared to the classic guestworker countries. Finland and Ireland experienced net-immigration already experienced net-immigration in the 1970s and 1980s. For a robustness check, these cases are dropped from the analysis.

14 Two alternative measurements are used as robustness check: government ideology measured based on the head of government, union density as a measurement of the strength of the crucial economic interest group linked with left-wing parties.

15 The actual initial condition (of early immigration experience) cannot be modelled because of a lack of data prior to 1980. We can use however the policy value of the year 1980 that dates after the guestworker era and before the new waves of large-scale immigration to Western countries. If countries’ policy designs tend to evolve along stable trajectories, we should observe this starting point to affect the outcomes later in time.

16 The mobility preference as the differential between the two policies does correlate with stay policy restrictiveness (r = 0.55) but not with entry policy restrictiveness (r = 0.00).

References

- Afonso, Alexandre (2012). ‘Employer Strategies, Cross-Class Coalitions and the Free Movement of Labour in the Enlarged European Union’, Socio-Economic Review, 10:4, 705–30.

- Afonso, Alexandre, and Camilla Devitt (2016). ‘Comparative Political Economy and International Migration’, Socio-Economic Review, 14:3, mww026–613.

- Armingeon, Klaus, and Philipp Lutz (2020). ‘Muddling between Responsiveness and Responsibility: The Swiss Case of a Non-Implementation of a Constitutional Rule’, Comparative European Politics, 18:2, 256–80.

- Armingeon, Klaus, Virginia Wenger, Fiona Wiedemeier, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner, and Sarah Engler (2018). Comparative Political Data Set 1960-2015. Bern: Institute of Political Science, University of Berne.

- Bonjour, Saskia (2011). ‘The Power and Morals of Policy Makers. Reassessing the Control Gap Debate’, International Migration Review, 45:1, 89–122.

- Boucher, Anna K., and Justin Gest (2018). Crossroads: Comparative Immigration Regimes in a World of Demographic Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Breunig, Christian, and Adam Luedtke (2008). ‘What Motivates the Gatekeepers? Explaining Governing Party Preferences on Immigration’, Governance, 21:1, 123–46.

- Carens, Joseph (2013). The Ethics of Immigration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Castles, Stephen (1986). ‘The Guest-Worker in Western Europe: An Obituary’, International Migration Review, 20:4, 761–78.

- Castles, Stephen (2006). ‘Guestworkers in Europe: A Resurrection?’, International Migration Review, 40:4, 741–66.

- Castles, Stephen, Heather Booth, and Tina Wallace (1984). Here for Good: Western Europe’s New Ethnic Minorities. London: Pluto Press.

- Castles, Stephen, and Godula Kosack (1973). Immigrant Workers and the Class Structure in Western Europe. London: Oxford University Press.

- Caviedes, Alexander A. (2010). Prying Open Fortress Europe: The Turn to Sectoral Labor Migration. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Chin, Rita (2007). The Guest Worker Question in Postwar Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Citrin, Jack, and John Sides (2008). ‘Immigration and the Imagined Community in Europe and the United States’, Political Studies, 56:1, 33–56.

- Cohen, Elizabeth F. (2018). The Political Value of Time: Citizenship, Duration, and Democratic Justice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cornelius, Wayne A., and Takeyuki Tsuda (2004). ‘Controlling Immigration: The Limits to Government Intervention’, in Wayne A. Cornelius, Takeyuki Tsuda, Philip L. Martin, and James F. Hollifield (eds.), Controlling Immigration: A Global Perspective, 2nd ed. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1–48.

- Dancygier, Rafaela, and Yotam Margalit (2020). ‘The Evolution of the Immigration Debate: Evidence from a New Dataset of Party Positions Over the Last Half-Century’, Comparative Political Studies, 53:5, 734–74.

- Dauvergne, Catherine, and Sarah Marsden (2014). ‘The Ideology of Temporary Labour Migration in the Post-Global Era’, Citizenship Studies, 18:2, 224–42.

- Dennison, James, and Andrew Geddes (2019). ‘A Rising Tide? The Salience of Immigration and the Rise of Anti-Immigration Political Parties in Western Europe’, The Political Quarterly, 90:1, 107–16.

- Ellermann, Antje (2013). ‘When Can Liberal States Avoid Unwanted Immigration? Self-Limited Sovereignty and Guest Worker Recruitment in Switzerland and Germany’, World Politics, 65:3, 491–538.

- Ellermann, Antje (2015). ‘Do Policy Legacies Matter? Past and Present Guest Worker Recruitment in Germany’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41:8, 1235–53.

- Ellermann, Antje (2021). The Comparative Politics of Immigration: Policy Choices in Canada, the United States, Germany, and Switzerland. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Ford, Robert, Will Jennings, and Will Somerville (2015). ‘Public Opinion, Responsiveness and Constraint: Britain’s Three Immigration Policy Regimes’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41:9, 1391–411.

- Freeman, Gary P. (1995). ‘Modes of Immigration Politics in Liberal Democratic States’, International Migration Review, 29:4, 881–902.

- Freeman, Gary P. (2006). ‘National Models, Policy Types, and the Politics of Immigration in Liberal Democracies’, West European Politics, 29:2, 227–47.

- Givens, Terri, and Adam Luedtke (2005). ‘European Immigration Policies in Comparative Perspective: Issue Salience, Partisanship and Immigrant Rights’, Comparative European Politics, 3:1, 1–22.

- Goldstone, Jack A. (1998). ‘Initial Conditions, General Laws, Path Dependence, and Explanation in Historical Sociology’, American Journal of Sociology, 104:3, 829–45.

- Green, Simon (2004). The Politics of Exclusion: Institutions and Immigration Policy in Contemporary Germany. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Guiraudon, Virginie (2000). ‘The Marshallian Triptych Reordered: The Role of Courts and Bureaucracies in Furthering Migrants’ Social Rights’, in Michael Bommes and Andrew Geddes (eds.), Immigration and Welfare: Challenging the Borders of the Welfare State. London: Routledge, 72–89.

- Hammar, Tomas (1985). European Immigration Policy: A Comparative Study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hammar, Tomas (1994). ‘Legal Time of Residence and the Status of Immigrants’, in Rainer Bauböck (ed.), From Aliens to Citizens: Redefining the Status of Immigrants in Europe. Avebury: Aldershot, 187–97.

- Hampshire, James (2013). The Politics of Immigration. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Hansen, Randall (2002). ‘Globalization, Embedded Realism, and Path Dependence: The Other Immigrants to Europe’, Comparative Political Studies, 35:3, 259–83.

- Haus, Leah A. (2002). Unions, Immigration, and Internationalization: New Challenges and Changing Coalitions in the United States and France. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Helbling, Marc, Liv Bjerre, Friederike Römer, and Malisa Z. Zobel (2017). ‘Measuring Immigration Policies: The IMPIC Database’, European Political Science, 16:1, 79–98.

- Helbling, Marc, and Dorina Kalkum (2018). ‘Migration Policy Trends in OECD Countries’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:12, 1779–97.

- Hollifield, James F. (2004). ‘The Emerging Migration State’, International Migration Review, 38:3, 885–912.

- Joppke, Christian (1998). ‘Why Liberal States Accept Unwanted Immigration’, World Politics, 50:2, 266–93.

- Joppke, Christian (2001). ‘The Legal-Domestic Sources of Immigrant Rights: The United States, Germany, and the European Union’, Comparative Political Studies, 34:4, 339–66.

- Koopmans, Ruud, and Ines Michalowski (2017). ‘Why Do States Extend Rights to Immigrants? Institutional Settings and Historical Legacies Across 44 Countries Worldwide’, Comparative Political Studies, 50:1, 41–74.

- Kustov, Alexander (2022). ‘Do Anti-Immigration Voters Care More? Documenting the Issue Importance Asymmetry of Immigration Attitudes’, British Journal of Political Science, First View. doi:10.1017/S0007123422000369.

- Lavenex, Sandra (2006). ‘Shifting Up and Out: The Foreign Policy of European Immigration Control’, West European Politics, 29:2, 329–50.

- Lavenex, Sandra, and Flavia Jurje (2014). ‘Trade Agreements as Venues for “Market Power Europe”? The Case of Immigration Policy’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 52:2, 320–36.

- Lijphart, Arend (2012). Patterns of Democracy: Government Form and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Lutz, Philipp (2019). ‘Variation of Policy-Success: Radical Right Populism and Migration Policy’, West European Politics, 42:3, 517–44.

- Martin, Philip (2015). ‘Guest or Temporary Foreign Worker Programs’, in Barry Chiswick and Paul Miller (eds.), Handbook of the Economics of International Migration. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 717–73.

- Messina, Anthony M. (2007). The Logics and Politics of Post-WWII Migration to Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Miller, Mark J., and Philip Martin (1982). Administering Foreign Worker Programs: Lessons from Europe. Lexington: Lexington Books.

- Odmalm, Pontus (2011). ‘Political Parties and ‘the Immigration Issue’: Issue Ownership in Swedish Parliamentary Elections 1991-2010’, West European Politics, 34:5, 1070–91.

- Piguet, Etienne (2006). ‘Economy Versus the People? Swiss Immigration Policy between Economic Demand, Xenophobia, and International Constraint’, in Marco G. Giugni and Florence Passy (eds.), Dialogues on Migration Policy. Lanham: Lexington Books, 67–89.

- Ruhs, Martin (2006). ‘The Potential of Temporary Migration Programmes in Future International Migration Policy’, International Labour Review, 145:1-2, 7–36.

- Ruhs, Martin (2013). The Price of Rights – Regulating International Labor Migration. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Ruhs, Martin, and Philip Martin (2008). ‘Numbers vs. Rights: Trade-Offs and Guest Worker Programs’, International Migration Review, 42:1, 249–65.

- Schultz, Caroline, Philipp Lutz, and Stephan Simon (2021). ‘Explaining the Immigration Policy Mix: The Relative Openness towards Asylum and Labour Migration’, European Journal of Political Research, 60:4, 763–84.

- Skeldon, Ronald (2012). ‘Going Round in Circles: Circular Migration, Poverty Alleviation and Marginality’, International Migration, 50:3, 43–60.

- Straubhaar, Thomas (1992). ‘The Allocational and Distributional Effects of Immigration to Western Europe’, The International Migration Review, 26:2, 462–83.

- Thielemann, Eiko, and Mogens Hobolth (2016). ‘Trading Numbers vs. Rights? Accounting for Liberal and Restrictive Dynamics in the Evolution of Asylum and Refugee Policies’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42:4, 643–64.

- Wright, Chris F. (2012). ‘Policy Legacies, Visa Reform and the Resilience of Immigration Politics’, West European Politics, 35:4, 726–55.

- Wright, Chris F., and Stephen Clibborn (2020). ‘A Guest-Worker State? The Declining Power and Agency of Migrant Labour in Australia’, The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 31:1, 34–58.