Abstract

A key Eurosceptic argument is that countries can selectively retain only those aspects of European integration from which they benefit, while opting out of those aspects they dislike. How convincing is this “have your cake and eat it, too” argument to voters? This article argues that voters can learn about the feasibility of such a strategy by looking at the experience of countries that pursued a similar path. Positive experiences can strengthen voters’ support for a similar strategy, while negative experiences can deter them. This argument is tested in a study of the effects of the Brexit negotiations on public opinion in Switzerland. Drawing on a panel survey fielded between 2019 and 2021, the article shows that Brexit had a small but non-negligible impact on Swiss voters’ expectations about the EU’s resolve, as well as on vote intentions on two EU-related policy proposals. These findings confirm that voters learn from foreign political developments about the costs of non-cooperation.

Over the past 15 years the European Union (EU) has come under increasing pressure. Geopolitical shifts, deepening integration and various crises have led to a growing politicisation and contestation of EU actors and institutions (De Vries Citation2018; Hobolt and de Vries Citation2016; Hooghe and Marks Citation2009; Hutter et al. Citation2016). Calls for substantial EU reform, opt-outs and even EU exit have become more frequent, and for the first time, a member state has left the Union. A key Eurosceptic argument is that countries can become better off by selectively retaining only those aspects of European integration from which their country benefits, while opting out of those aspects they dislike. The assumption is that the EU will ultimately accommodate such changes rather than insist on an all-or-nothing approach because a full-scale reduction of cooperation levels would cause considerable harm to the EU as well.

At the same time, the EU overall has in fact become less willing to tolerate differentiated integration, that is to support the existence of varying institutional rules across states that participate in some EU arrangements but not necessarily all (Matthijs et al. Citation2019). Core state powers of EU member states have become further integrated during the last decade (Genschel and Jachtenfuchs Citation2018). Increasingly, the EU closes and controls external boundaries, and strives for more boundary congruence. This process of ‘internal debordering with external rebordering’ (Schimmelfennig Citation2021) presents a problem for those voters and elites who seek to increase or maintain ‘differentiated integration’ by selectively opting in policy areas they like to see pooled at the EU level and opting out from those that they prefer to deal with at the national level (Leuffen et al. Citation2013). Rather than accommodate requests for differentiation, the EU now increasingly insists that the benefits of EU integration can only be enjoyed when the costs are also borne.

Differentiation-seeking voters in other countries – both in EU member states and in non-members with more differentiated relations with the EU – are thus confronted with two conflicting narratives: On the one hand, they hear about the benefits of differentiation and the apparent ease of implementing such a strategy. On the other hand, the EU claims it is resolved to not let countries pick and choose their preferred EU rules for a ‘Europe à la carte’. Adjudicating between these two narratives can be hard given that there are good reasons for differentiation-seeking voters to question the EU’s resolve to not allow any cherry-picking. The EU’s threat not to accommodate differentiation requests faces credibility problems because not cooperating is costly for both sides (Jurado et al. Citation2022; Walter Citation2021a, Citation2020; Walter et al. Citation2018). Thus, voters have reasons to doubt the EU’s proclaimed determination to not accommodate differentiation requests and to expect that, ultimately, the EU will be willing to compromise.

We argue that one way for differentiation-seeking voters to assess these competing claims is to look to other country’s differentiation attempts to gauge the EU’s resolve. The more other countries succeed in their differentiation bids, the less convinced voters should become of the EU’s resolve, making them less willing to agree to any institutional proposals that decrease differentiation. At the same time, another country’s positive differentiation experience is likely to reinforce beliefs in the Eurosceptic narrative and to encourage differentiation demands abroad (De Vries Citation2017; Glencross Citation2019; Jurado et al. Citation2022; Malet Citation2022; Walter Citation2021a).

In order to empirically test this argument, we focus on how the Brexit negotiations affected public opinion in Switzerland. Brexit can be understood as an extreme form of differentiation: EU exit, followed by the development of a new external differentiation arrangement (Schimmelfennig Citation2021).Footnote1 Although the withdrawal negotiations did indeed focus on the terms of the ‘divorce’, these terms had significant consequences for future UK-EU relations, and hence the specific type of differentiation the UK would be able to pursue moving forward. In fact, the exact terms of this relationship continue to be subject of significant debate, including the suitability of a ‘Swiss-style’ arrangement for the UK.Footnote2 The EU’s response to Brexit thus provides important information regarding the question of how the EU is likely to respond to other countries’ differentiation bids.

Switzerland has a unique relationship with the EU. It is not an EU member state, but has close relations with the EU characterised by a large number of bilateral treaties regulating these relations. Despite these unique characteristics, two factors make Switzerland a particularly useful case to study the question at hand. First, it is a case where both a reduction and an increase in differentiation were actually on the table at the same time as the EU was negotiating the differentiation bid – in this case withdrawal – of another country (the UK) from the EU. Second, Switzerland is a particularly hard case for finding any diffusion-related changes in EU-related attitudes. Swiss voters have repeatedly voted on EU-related issues in the past and the issue is highly politicised, so attitudes on Swiss-EU relations tend to be rather crystallised (Bornschier Citation2015; Christin and Trechsel Citation2002). Finding any effect of the UK’s Brexit experience on Swiss EU attitudes thus suggests that similar cross-national dynamics are likely to occur in other contexts as well.

We use an original panel survey conducted in Switzerland in three waves between fall 2019 and spring 2021 to examine how the UK’s Brexit experience shaped Swiss voters’ expectations about the EU’s resolve not to accommodate Switzerland’s differentiation requests as well as vote intentions on two proposals about either decreasing or increasing differentiation with the EU. We find that voters’ evaluations of Brexit had a small but not negligible impact on their expectations about the consequences of Swiss differentiation bids, which translated into voting intentions in related referendums. The effect of the Brexit negotiations on Swiss public opinion was strongest among respondents with moderate views of Swiss-EU relations. Overall, our findings suggest individual countries’ differentiation bids reverberate far beyond the individual case because they feed into broader dynamics and create a potential for domino effects across Europe.

No to differentiation – really? Gauging the EU’s resolve by looking at precedents

Perhaps the most prominent argument of Eurosceptics seeking more differentiation from the EU is that their country can enjoy the benefits of European integration without full membership or full adherence to EU rules. This argument has been put forth most famously by then British foreign minister Boris Johnson, who in 2016 described his government’s Brexit policy as ‘having our cake and eating it’.Footnote3 But similar arguments have also been advanced by political actors critical of the EU in Greece (Walter et al. Citation2018a), Denmark (Beach Citation2021), or Switzerland (Armingeon and Lutz Citation2020) during explicit pro-differentiation campaigns such as the 2015 Greek bailout referendum, the 2015 Danish opt-out referendum or the 2014 Swiss ‘Against Mass Immigration’ initiative. Typically, differentiation-seeking actors argue that not accommodating such requests would be very costly for the EU and its member states, as it would substantially reduce existing cooperation gains and also create opportunity costs in terms of forgone new agreements. As Eurosceptics in both EU member states as well as in countries that have close relations with the EU but are not members like to point out, this creates incentives for the EU to ultimately compromise and accommodate differentiation requests.

Despite these incentives, the EU has taken an increasingly inflexible stance regarding states’ differentiation requests in recent years, especially with regard to countries that are not (or no longer) members of the EU, but nonetheless want to enjoy close relations with the EU such as the UK (Schimmelfennig Citation2021). In light of growing Eurosceptic pressure and increasing contestation over the EU’s boundaries, the EU faces substantial risk that by accepting tailor-made, differentiated arrangements and opt-outs for individual countries, it may further encourage similar demands elsewhere (De Vries Citation2017; Glencross Citation2019; Jensen and Slapin Citation2012; Walter Citation2021a). Such arrangements can thus be perceived as a threat to the cohesion of the EU and the understanding that the EU is a package deal in which all members make compromises to generate cooperation gains (Adler-Nissen Citation2014). For the EU, differentiation requests thus create a difficult trade-off (Walter Citation2021a, Citation2021b): Not accommodating such requests is costly, yet accommodation carries long-term risks for the stability of the EU.

The existence of this trade-off, however, makes it difficult for differentiation-seeking voters to determine the EU’s true resolve on questions of differentiation, as they are confronted both with the argument that the EU will surely accommodate differentiation bids, and the EU response that it will not (Walter et al. Citation2018). We argue that in such a context, an important way for voters to learn about the EU’s resolve and about the consequences of refusing to cooperate on the EU’s terms, is to observe how the EU responds to other countries’ differentiation bids.

There are several reasons to think that voters learn from foreign experiences and update their preferences about a possible differentiation bid in light of EU resistance. First, much research has demonstrated that voters’ expectations about the consequences of more or less cooperative behaviour affect their preferences for international cooperation (Grynberg et al. Citation2020; Hobolt Citation2009; Sciarini et al. Citation2015; Walter et al. Citation2018). Preferences for a change in the terms of cooperation are rooted in a comparison between the status quo and alternative scenarios of more or less cooperation (De Vries Citation2018). This alternative scenario is hard to predict, will it be a form of differentiated integration? Or will the EU make good on its threat not to accommodate requests for differentiation? Because the EU has an incentive to hide its true propensity to accommodate demands (Walter et al. Citation2018), observing its reaction to other country’s bids provides important pieces of information in this regard. Second, several studies have shown that voters use information about political developments in other countries to form their own opinion about policy issues (Linos Citation2011; Malet Citation2022; Pacheco Citation2012). There is now considerable evidence, for example, that Brexit had an impact on individual EU attitudes (De Vries Citation2018; Hobolt et al. Citation2022; Malet and Walter Citation2021; Walter Citation2021a) and party discourse (Martini and Walter Citation2023; Van Kessel et al. Citation2022) in the remaining EU-27 countries.

For both of these reasons, we expect that observing other countries’ differentiation bids allows voters abroad to glean important information about the EU’s resolve not to accommodate significant differentiation bids, and hence the costs and opportunities of pursuing a similar course of action. Although it can be hard to observe the EU’s resolve in negotiations, media coverage about the negotiations, the process, and its consequences allows voters to form a general opinion of another country’ differentiation attempts and its short- to medium-term success. We expect them to use this information to assess whether the strategy pursued by the other country is an example for their own country to follow or to avoid, and to update their attitudes about potential differentiation bids of their own country. This generates the following hypothesis: The more successful another country’s differentiation bid is perceived to be, the more voters in other countries will support differentiation for their own country, and vice versa.

Research on motivated reasoning (Bisgaard Citation2015; Kraft et al. Citation2015) tells us, however, that not all voters will be susceptible to this updating mechanism. When people hold strong prior beliefs, it is difficult to change their (mis-)perceptions with corrective information (Grynberg et al. Citation2020; Kertzer and Zeitzoff Citation2017; CitationTaber and Lodge 2006). As a result, some voters show themselves unwilling to update their expectations and attitudes, even when confronted with conflicting evidence. In our context, this suggests that the effects of observing another country’s differentiation bid is likely to be weaker both among staunch opponents and staunch supporters of a more differentiated relationship with the EU, and stronger among individuals with less strongly held beliefs about their country’s relation with the EU. The overall effect of another country’s differentiation bid on support for differentiation elsewhere thus depends both on the size and direction of the signal (the success of the differentiation attempt) and the number of voters susceptible to (re)considering their preferences in light of this signal.

Switzerland between differentiated integration and rebordering

In order to empirically examine this argument, we focus on Switzerland, which has for decades had a close but differentiated relationship with the EU. In 1992 Swiss voters rejected membership in the European Economic Area. Subsequently, Switzerland and the EU created a tight web of over 120 bilateral treaties that allow for close cooperation on issues as diverse as market access, research cooperation and free movement, and even membership in the Schengen/Dublin regime (Oesch Citation2020). This approach has been dubbed a ‘customized quasi-membership’ (Kriesi and Trechsel Citation2008), making Switzerland a posterchild of differentiated integration. It is also hugely popular in Switzerland (Dardanelli and Mazzoleni Citation2021; Emmenegger et al. Citation2018).

Against this background, two differentiation-related dynamics have emerged in Switzerland in recent years, which make the country a fascinating case for studying the question at hand. The first dynamic is a push for more Swiss differentiation, in the sense of increasing Switzerland’s ability to deviate from the EU’s rules regarding free movement of people. This push came in the form of a popular initiative launched by Swiss Eurosceptics called ‘Limitation initiative’ which, if approved, would have obliged the Swiss government to renegotiate or withdraw from the free movement treaty with the EU in order to give Switzerland more possibilities for restricting EU migration.Footnote4 Withdrawal would however fundamentally put Switzerland’s bilateral relations with the EU into question because of the ‘guillotine clause’, a legal clause that stipulates that if one of the main seven bilateral treaties is terminated, all of them cease to apply. The Limitation initiative thus effectively confronted Switzerland with a choice between continued adherence to EU immigration rules, and the possibility of losing access to the EU’s Single market overnight. Eurosceptics, however, argued that the EU would not ‘pester and bully one of its best customers’, and that the risks were ultimately low.Footnote5

The second dynamic that has marked Swiss-EU relations in recent years is a push on part of the EU for less differentiation in Switzerland-EU relations. This push reflects the EU’s attempts to encourage more congruence, especially among participants in the Single Market. In 2014 Switzerland and the EU began to negotiate about a new ‘Institutional framework agreement’ (InstA). The idea was to institutionally bundle the seven main bilateral agreements (Bilaterals I) and any future agreements together into one overarching legal agreement. The framework agreement put in writing the supremacy of EU law in issues related to the Single Market and gave the European Court of Justice an important role in dispute resolution processes. The agreement can thus be seen as a rebordering attempt by the EU, designed to reduce differentiation. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there was large resistance against this attempt in Switzerland and the institutional framework agreement was contested in Swiss politics from the start of the negotiations in 2014.

As a result, Switzerland is confronted with a choice between signing up to a less differentiated new model of Swiss-EU relations or letting cooperation with the EU erode. Despite these threats, the Swiss government pulled out of the negotiations in spring 2021. Asked about the EU’s threats in an interview, Swiss foreign minister Ignacio Cassis responded ‘We have to be careful not to paint the situation too black. Of course, we will have certain disadvantages. But relations with our neighboring regions are incredibly solid. […] We cannot imagine that there will be a rupture in these relations’.Footnote6

We leverage this unique setting to test our argument in a context in which concrete policy proposals to both differentiate further (the Limitation initiative) and to reduce differentiation (the framework agreement) were high up on the political agenda. Public opinion is particularly meaningful in the case of Switzerland, as Swiss voters regularly vote on proposals concerning Swiss-EU relations. As a direct democracy, no major international treaty can be ratified without an affirmative referendum vote. This context makes it possible to elicit vote intentions on actual upcoming direct democratic votes, rather than voters’ preferences on broad policy issues. Additionally, both policy proposals were debated and discussed against the backdrop of the Brexit negotiations between the UK and the EU, making this case particularly interesting for our purpose. Brexit can be seen as an attempt by the UK to significantly increase differentiation in its relations with the EU (Schimmelfennig Citation2021) and thus serves as precedent both for EU member states and non-EU member states interested in extending the level of differentiation in their relations with the EU. Observing the EU’s actions in the Brexit negotiations thus provided Swiss voters with a unique opportunity to learn about the EU’s willingness to accommodate the UK’s differentiation requests and to use this information to gauge the EU’s resolve with regard to their own differentiation bids.

Brexit featured prominently on the Swiss debate about how to develop the country’s relationship with the EU. A report analysing how Swiss newspapers referred to Brexit finds that the public debate about the Switzerland-EU relationship frequently referred to Brexit and often presented it as a ‘role model’ for Switzerland (Zemp Citation2022). After Boris Johnson finally concluded the Withdrawal Agreement in October 2019, newspapers were full of op-eds discussing what the Brexit Treaty meant for Swiss-EU negotiations, with headlines such as ‘What does the Brexit deal mean for Switzerland?’ (Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 18 October 2019) or ‘The EU and the UK have reached an agreement on Brexit - it’s a lesson for Switzerland’ (Luzerner Zeitung, 18 October 2019).Footnote7 Likewise, politicians from both side of the political spectrum tweeted their rather diverse interpretations of what the deal meant for Switzerland. These interpretations ranged from arguments that just like Johnson, the Federal Council should pressure the EU to achieve results,Footnote8 to warnings that the deal had only happened for fear of fatal consequences of a No-Deal Brexit for the UK, which were echoing the risks of an erosion of the bilateral path.Footnote9 Although politicians and pundits agreed that Brexit did provide important lessons, they diverged in their opinions about what these levels were. Whereas Eurosceptic outlets and politicians celebrated Brexit as an example and suggested that Switzerland should equally play tough with the EU, Europhile pundits and politicians saw Brexit much more as a cautionary tale for Switzerland, suggesting that Switzerland should compromise with the EU rather than insist on its demands.

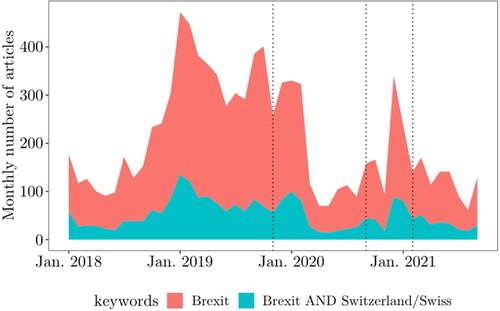

displays the coverage of Brexit in six Swiss newspapers. It reports the monthly number of articles that mention the word ‘Brexit’, alone or in relation with ‘Switzerland’/‘Swiss’. It confirms the high media attention devoted to the British negotiations, and the relevant share of references made to the Swiss case in this context. This attention to Brexit is also reflected in the high levels of knowledge among the Swiss public. In our survey, 87% percent of respondents knew the meaning of a ‘no-deal Brexit’, and 67% correctly identified the party of the British PM (see Figure A1 in the online appendix). Taken together, this evidence suggests that Swiss voters were not just exposed to information about the EU's negotiations with the UK, but also correctly remembered key aspects of this information.

Figure 1. Media coverage of Brexit in Switzerland.

Note: Monthly number of articles mentioning ‘Brexit’ or ‘Brexit’ and ‘Switzerland’/‘Swiss’ (in German and French) in the six following Swiss newspapers: Blick, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Tages-Anzeiger, Weltwoche, Le Temps, 24 Heures. The vertical lines indicate the timing of our survey waves.

Research design: Swiss-EU relations and Brexit negotiations

In order to study how Swiss voters used information from Brexit, we designed and fielded an original online panel survey among the voting-age Swiss population. The survey was implemented as a web survey (CAWI) by the polling company gfs.bern and relies on its internet panel to recruit respondents using quotas for age, gender, and language region. The data is weighted based on language region, age, gender, education, and party affinity in order to ensure the representativeness of the sample.Footnote10

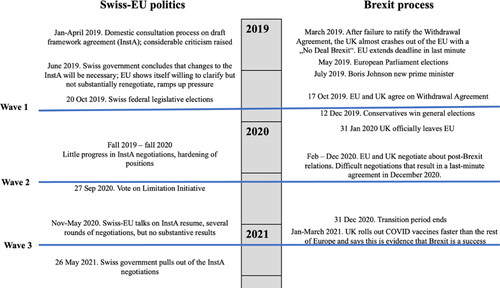

Our study analyzes data collected in three survey waves fielded between October 2019 and February 2021, a turbulent time both for Swiss-EU politics and Brexit politics.Footnote11 This survey design allows us to analyse whether changes in people’s perceptions of the Brexit process are related to changes in people’s expectations about the consequences of Swiss differentiation bids and in their vote intentions. shows that the first survey wave with 2633 respondents was carried out between 25 October and 11 November 2019, right after the Swiss federal legislative elections. This wave fell in a time when Swiss-EU negotiations on the framework agreement were stalled, and shortly after the breakthrough in UK-EU negotiations that was achieved when Boris Johnson signed the revised Withdrawal Agreement. The second wave was fielded among 1613 respondents from 9–28 September 2020, right before the direct democratic vote on the Limitation initiative, and during a time where negotiation positions on both the framework agreement and on the EU-UK post-withdrawal relations had hardened. The third and final wave was carried out from 8–28 February 2021 with 1395 respondents, shortly after the Brexit transition period ended. During this period, Swiss-EU negotiations on the framework agreement had intensified (to ultimately fail a few months later), and the UK was boasting that its fast and successful COVID-vaccine rollout was evidence for the benefits of Brexit.

Dependent variables: expected consequences of differentiation and vote intentions

The Swiss case allows us to explore public opinion on two types of differentiation bids: one bid for increasing differentiation (the Limitation initiative), and one for maintaining existing levels of differentiation (rather than decreasing it) in the context of the negotiations on the framework agreement. Our hypotheses suggest two sets of dependent variables: The first set are voters’ expectations about the EU’s resolve not to accommodate Swiss differentiation requests, and thus about the consequences of pursuing differentiation. A second set are vote intentions in direct democratic votes on each of these differentiation bids. We operationalise each of these concepts as follows.

Expectations about the consequences of differentiation bids

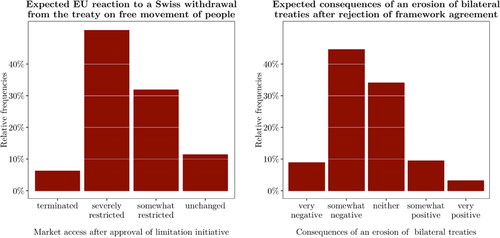

Our survey contained two questions that measure how Swiss voters expected the EU to respond to a Swiss decision to reduce or maintain differentiation. These questions gauge respondents’ assessments of the EU’s resolve. With regard to the Limitation initiative, the survey asked: ‘If Switzerland terminates the Treaty on the Free Movement of Persons, the EU has the right to terminate several bilateral agreements with Switzerland and thus severely restrict Switzerland’s access to the EU market. How do you think the EU is most likely to react? If Switzerland withdraws from the Treaty on the Free Movement of Persons, the EU will (1) terminate/(2) strongly restrict/(3) somewhat restrict/(4) leave unchanged Switzerland’s extensive access to the EU market’. As the EU has repeatedly warned that it would let Swiss-EU relations erode until a framework agreement was concluded, respondents were also asked to assess the consequences of an erosion of the bilateral treaties between Switzerland and the EU. The question informed respondents that the EU had announced that it would not update existing agreements and would not conclude any new agreements with Switzerland until a framework agreement has been signed, and then asked them to rate how this would affect Switzerland. Answers were recorded on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (very negative impact) to 5 (very positive impact).

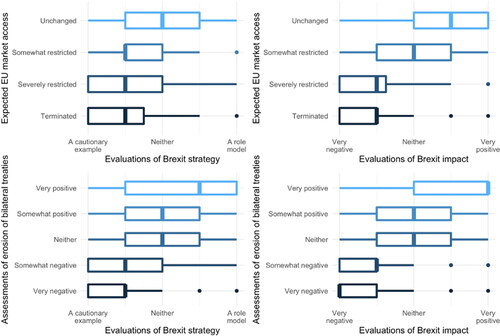

shows that expectations about the EU’s resolve vary considerably.Footnote12 While a majority of people are pessimistic about the possibility to increase differentiation at little cost, few believe that the EU will fully follow through with its threats. At the same time, one third of respondents believe that differentiation would have few consequences which is in line with the argument that ‘the EU is just as dependent on us as we are on it’.Footnote13 About a third of respondents believe that the EU would impose little restrictions to Switzerland’s access to the Single Market if the country withdrew from the Treaty of Freedom of Movement, and 11% of respondents expect the EU not to react at all. Likewise, a third of respondents believe that an erosion of the bilateral relation will have neither positive nor negative consequences for Switzerland overall and 13% even believe that it will have a positive impact.

For ease of interpretation in the analyses below, answers to the expectation questions are dichotomised and rescaled. For the Limitation initiative, 1 indicates unchanged or only slightly reduced market access and 0 a severe restriction or termination, whereas for the framework agreement 1 indicates (very) positive or neutral consequences and 0 (very) negative consequences. Models with fully scaled dependent variables are presented in the online appendix.

Support for differentiation bids

To examine the hypothesis that more negative assessments of the UK’s Brexit experience are associated with more support for the Limitation initiative and less support for the framework agreement, we focus on Swiss vote intentions in two upcoming direct democratic votes. To measure vote intentions on the Limitation initiative, held on 21 September 2020, respondents were asked ‘The popular initiative “For a Moderate Immigration (Limitation Initiative)” calls for the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons with the EU to be suspended or terminated. If the popular vote on the Limitation Initiative was held today, how would you vote?’ Although a referendum on the Framework Agreement was not held during the period covered by our survey, it was always clear that the final agreement would have to be put to a popular vote. We therefore ask: ‘Switzerland is currently discussing the conclusion of an institutional framework agreement with the EU. Thanks to this agreement, Switzerland would continue to benefit from a large degree of access to the European internal market, but in return would be obliged to adapt to EU law to a greater extent than at present. How would you vote if the referendum on the framework agreement were held today?’ Answer categories ranged from 1 (definitely against) to 4 (definitely in favour). The answers were dichotomised for ease of interpretation, and rescaled so that 1 indicates support for increasing/maintaining differentiation and 0 opposition to such bids. Models with fully scaled dependent variables are presented in the online appendix. Vote intentions were measured in wave 1 and 2, and for the Framework Agreement additionally in wave 3.

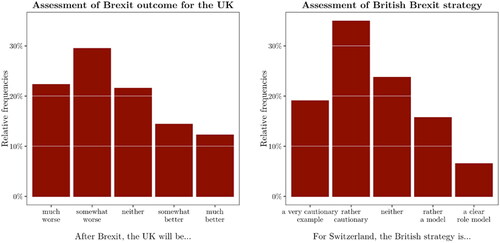

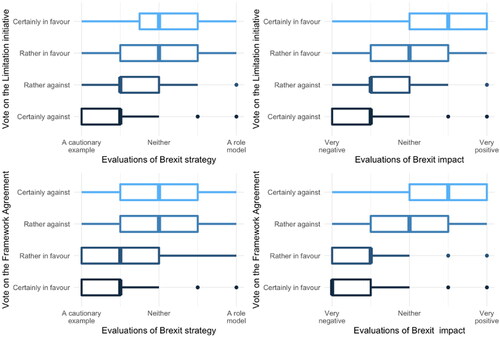

Actual policy support for differentiation is split in our sample: In October 2019 (wave 1) 39% of respondents planned to certainly or probably vote for the Limitation initiative (with 58% against). The Limitation initiative was ultimately rejected at the polls in September 2020 with 61.7% votes against the initiative. Likewise, 42% planned to reject the framework agreement, whereas 53% of respondents planned to vote for it.

Independent variable: assessment of another country’s differentiation attempt

Our argument centres on how differentiation-bids by another country are related to voters’ assessments of their own countries’ bids to maintain or increase differentiation. To examine this argument empirically, our analysis focuses on Swiss voters’ assessment of the UK’s Brexit experience. To proxy Swiss voters’ perceptions about the success of the UK’s differentiation bid, we use two questions that tap respondents’ assessments of the overall medium-term outcome of Brexit for the UK, and about the lessons that Switzerland should draw from the British negotiation strategy.

What do you think will be the overall impact of Brexit over the next 5 years? As a result of Brexit, the UK will be… [much better/somewhat better/neither better nor worse/somewhat worse/much worse].

For Switzerland, the UK’s negotiation strategy is… [a clear role model/rather a role model/neither/rather a cautionary example/a very cautionary example].

These items cover two key aspects of Swiss people’s evaluations of the Brexit process and thus also allow us to measure two key recognisable consequences of the EU’s response to the British differentiation bid. The first measures respondents’ overall assessment of the consequences of Brexit for the UK and thus allows us to gauge how successful Swiss respondents view the UK’s differentiation bid. The second variable gets closer at the cross-national learning mechanism and taps directly to what extent and how Swiss respondents think that the UK’s experience holds lessons for Switzerland’s own relations with the EU. Only about one quarter of respondents think that Brexit holds neither a positive nor negative lesson for Switzerland, providing some initial evidence that cross-national learning is indeed taking place. In the online appendix we also show that (as one would expect) the two items are correlated, as people who think that the UK will be better off after Brexit are also more likely to perceive the British strategy as a role model for Switzerland (Table A6).

We recoded the variables so that higher values correspond to more positive evaluations of Brexit. shows that people’s assessment of the Brexit outcome (measured in wave 1) were quite negative, with more than a half of respondents predicting the UK to be worse off or much worse off after Brexit. Our respondents also tended to see the British strategy rather as a cautionary example (around 55%) than as role model for Switzerland (around 22%). This suggests that Swiss respondents in general were aware that the EU proved rather resolved not to accommodate the UK’s Brexit-related differentiation bids, depressing their appetite to emulate the British approach. Especially for Eurosceptics, however, Brexit had considerable appeal. In our sample, those who had a negative view of the EU were more likely to think that the UK after Brexit would be better off (40%) than worse off (30%).

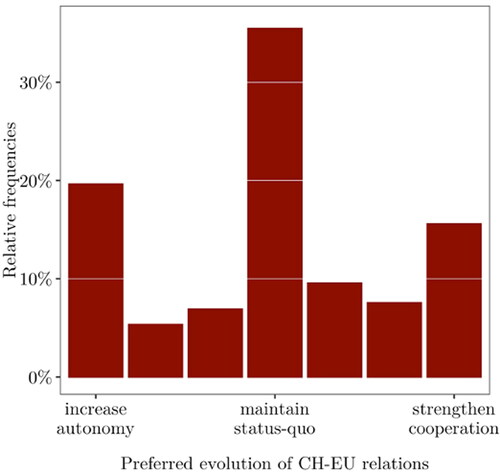

Moderating variable: attitudes towards Swiss-EU cooperation

In order to test our hypothesis about the moderating role of motivated reasoning, we additionally include a variable on the strength of respondents’ prior beliefs about Swiss-EU relations. This variable records respondents’ preferred evolution of Swiss-EU relations by asking them to place themselves on a scale that goes from 1 (increase autonomy from the EU) to 7 (increase cooperation with the EU), where 4 indicates support for maintaining the status-quo. shows that more than a third of respondents exhibit a strong preference for the status-quo. However, the two peaks at the extreme ends of the distribution also indicate a strong polarisation of attitudes, suggesting that the high politicisation of the European integration issue in the Swiss political debate over the last thirty years has left a mark on voters’ attitudes (Bornschier Citation2015; Kriesi Citation2007). We analyse the heterogenous effect of previous attitudes towards Swiss-EU cooperation by focussing on these attitudes measured at wave 1, as such they are not included as constitutive term in the fixed-effect model.

Models

Our analyses leverage the panel structure of our survey, which means that the same respondents answered the same questions at several points in time. This means that we can analyse whether changes in people’s assessment of the Brexit experience affect changes in expectations about the consequences of differentiation bids and changes in policy support for such bids. Focussing on changes allows us to circumvent the problem, that Brexit evaluations, expected consequences of differentiation, and vote intentions, are all strongly correlated with Euroscepticism. The drawback of this approach is that it limits our ability to detect a substantive effect and sets a bound to a general interpretation of a one-unit change in Brexit evaluations in the analysis of the Limitation initiative because of the stability of opinions. If we consider only the first two waves, we observe that a majority of respondents did not change their assessments at all.Footnote14 We observe larger shifts when we analyse three waves, as we do when we study the framework agreement and its consequences. Here a one-unit change is the median change in Brexit assessments among our respondents.

In the analyses below, we present results from two-way fixed-effects models. While such models account for time-invariant unobserved confounders, we additionally control for observed time-variant confounders by including a set of control variables measured at each wave. We control for exposure to Brexit-related news, interest in Swiss-EU relations, dissatisfaction with democracy, economic dissatisfaction, government approval, vote intention for the radical-right SVP, ideology (left-right) and its squared term, support for immigration (a three-item index), and populism (a five-item index).

How Brexit affects Swiss-EU relations: descriptive evidence

Our data show a strong relation between interpretations of the Brexit process and expected or desired developments in Swiss politics. Those evaluating Brexit positively question EU resolve much more strongly and support more differentiation in Switzerland’s relations with the EU. For example, shows that respondents who see Brexit as a role model and who expect the UK to benefit from Brexit are much more likely to believe that the EU would not restrict Switzerland’s access to the internal market were the country to terminate the Treaty on the free movement of persons. They are also much less concerned about an erosion of the bilateral treaties. In contrast, respondents who view the British Brexit strategy as a cautionary example and the consequences of Brexit as negative, are more likely to believe that the EU will indeed restrict or even terminate Switzerland’s access and more concerned about an erosion of the bilateral treaties.

Similarly, suggests a strong correlation between Brexit assessments on the one hand, and support for the Limitation initiative and the framework agreement on the other. People who see the British strategy as a cautionary example and foresee negative consequences for the UK are much more likely to vote against the Limitation initiative and much more likely to vote in favour of the framework agreement.

While Brexit featured prominently both in the discussions on Swiss-EU relations and is strongly correlated with expectations and vote intentions, it is less clear that it actually changed these expectations and vote intentions, as suggested by our argument. Indeed, and show that public opinion on Swiss-EU relations is strongly crystallised and hard to move. With regard to the Limitation initiative, for example, almost 90% of the people maintained their position in the ten months before the vote. We also find a high degree of stability of voting intentions on a hypothetical referendum on the framework agreement (). Between fall 2019 and winter 2021, 1080 out of 1285 respondents (84%) did not change their mind.

Table 1. Changes in vote on limitation initiative and changes in expected EU accommodation (October/November 2019–September 2020).

Table 2. Changes in vote on the framework agreement and changes in expected consequences of an erosion of bilateral treaties (Oct./Nov. 2019–February 2021).

At the same time, we observe more variation in people’s expectations about the consequences of a decision to terminate the treaty on the free movement of people. Whereas 63.4 percent did not change their mind about the expected EU reaction, 21% became less optimistic (i.e. expecting the EU to be less accommodative) and the expectations of 16% of respondents became rosier overtime. With regard to the consequences of not concluding a framework agreement, 20% of our respondents become more pessimistic and 24% more optimistic over time. This suggests that in the fifteen months covered by our survey, the EU was not able to convince Swiss voters that a failure to sign up to the framework agreement would derail Swiss-EU relations.

and also show a strong correlation between changes in vote intentions and changes in expectations. Of the 97 people (6.6%) who decided to change their vote towards a rejection of the Limitation Initiative (cooperative shift), more than one third expected the EU to be less accommodative in September 2020 compared to ten months before. Conversely, around one third of the people who moved from opposition to support (non-cooperative shift) expected the EU to be more accommodative in September 2020 compared to October/November 2019. We see similar dynamics for the framework agreement. At the same time, also for expectations we see that many respondents did not change their assessments, even if they adjusted their vote intentions.

Altogether, these numbers show a very high stability of both expectations and vote choice which makes it unlikely to find statistically significant effects. However, they also suggest that among the few who changed their vote intentions, a good share also updated their expectations about the EU’s resolve. We therefore next turn to a more systematic analysis of these relationships.

The effect of Brexit evaluations on expectations

We start by analysing whether changing evaluations of Brexit were related to changes in Swiss voters’ perceptions of EU resolve, measured as the likely EU response to a Swiss bid to increase or maintain differentiation. shows that, on average, respondents whose assessments of Brexit become more positive over time become more likely to expect an accommodative reaction from the EU (models 1, 3, 5, and 7). Reflecting the high stability of opinions documented above, we find that in most cases changes in Brexit assessments have no statistically significant effect on the expected EU response. Model 3 provides an exception, and it estimates that a voter whose evaluations of the Brexit impact on the UK become more positive by one-point becomes 4 percent more likely to expect an accommodative reaction from the EU in case of popular approval of the Limitation initiative (i.e. market access unchanged or only slight reduced).

Table 3. The impact of changes in Brexit evaluations on changes in expected consequences of differentiation.

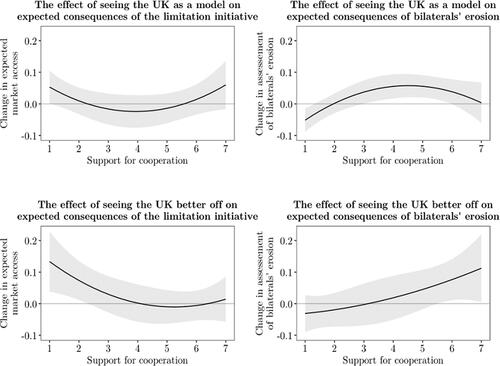

However, we also hypothesised that the effects of observing another country’s differentiation bid should be moderated by respondents’ pre-existing attitudes about Switzerland’s relations with the EU. Models 2, 4, 6 and 8 therefore include interaction terms to test our hypothesis that voters with less extreme pre-existing attitudes are more likely to update their expectations as they may have less entrenched convictions about the EU’s reaction than those with extreme attitudes. plots the interaction effects.

These analyses show that changes in evaluation of the British negotiation strategy have a heterogenous effect on expectations depending on respondents’ pre-existing attitudes. With regard to the Limitation initiative (, left panel), Eurosceptic voters are the only ones who change their expectations about the market access that Switzerland would be granted by the EU in case of unilateral termination of the free movement of people. Among Eurosceptic voters, those who came to perceive the British strategy more as a model, or the impact of Brexit on the UK as more positive, became more likely to believe that the EU would accommodate Swiss demands for further differentiation, while the expectations of those who saw Brexit as a cautionary example became more negative. These results suggest that the Brexit process had a limited but clear effect in Switzerland as it sent a signal to those voters who were more willing to follow a similar path. In contrast, with regard to the framework agreement and a possible erosion of the bilateral treaties, only people with middle positions, or only slightly favourable to increase Swiss-EU cooperation, changed their evaluations of an erosion of the bilateral treaties based on how they perceived the British Brexit strategy. The more they came to see the UK as a cautionary example, the more they were likely to see the consequences of an erosion of the current treaties as negative for Switzerland. We find that the effects of seeing the UK worse or better off on the expected consequences of the bilateral treaties’ erosion is stronger among Europhile citizens, but this effect is not statistically significant in Model 8.

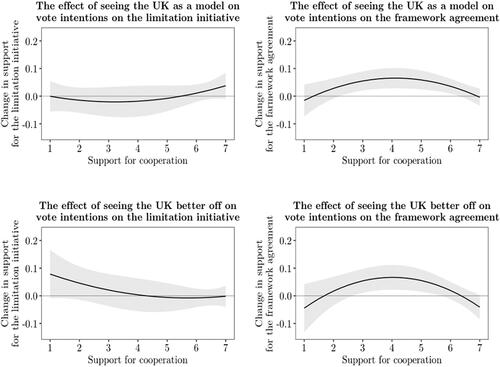

The effect of Brexit evaluations on vote intentions

We next analyse whether voters’ assessments of Brexit directly affected their vote intentions on concrete reform proposals concerning Swiss-EU relations. Here, we focus on the question whether voters’ assessments of Brexit directly affect their referendum vote intentions (). Again, the results differ across issues: With regard to the Limitation initiative, changes in Brexit evaluations, however measured, have no effect on changes in referendum vote intentions (Models 9 and 11). There are also no statistically significant heterogenous effects of Brexit evaluations across different levels of support for Swiss-EU cooperation (Models 10 and 12, and , left panels).

Table 4. The impact of changes in Brexit evaluations on changes in vote intentions.

We find more evidence of a ‘Brexit effect’ when we analyse vote intentions in a hypothetical referendum on the framework agreement, which span three waves of our survey. Here, we see that on average, voters who changed their evaluation of the British negotiation strategy in a positive direction, were more likely to express growing opposition to the framework agreement (Model 13). Instead, voters’ assessments of the Brexit impact on the UK, on average, do not have an impact on Swiss vote intentions. We find significant interaction effects in line with our expectations (Models 14 and 16 and , right panels). Voters with non-extreme attitudes on Swiss-EU cooperation changed their preferences towards the framework agreement based on their updated evaluations of the Brexit impact and of the Brexit strategy. Among people in favour of the status-quo of Swiss-EU relations, a one-point positive change in assessments of the British strategy or in evaluations of the Brexit impact on the UK increased people’s opposition to the framework agreement by around 7 percentage points.

How can we interpret these conflicting findings? On the one hand, the findings for the Limitation initiative underscore that the power of the EU to signal its resolve is limited when faced with entrenched attitudes. The issue of free movement of people has been a contentious issue in Swiss politics for year, and the Limitation initiative was a second try to restrict it after an initial, successful popular initiative on restricting ‘mass immigration’ had not been fully implemented in light of the EU’s unwillingness to accommodate Switzerland (Armingeon and Lutz Citation2020). In such a setting it is hard to sway people’s minds and the low share of ‘vote switchers’ of only 10% attests to this difficulty. On the other hand, the findings for the framework agreement confirm our expectations that people with middle positions tend to be more malleable, giving the EU an opportunity to influence this group of people when opinions are less entrenched and when the negotiation situation is similar. After all, difficult negotiations between Switzerland and the EU were ongoing during the Brexit negotiations, whereas negotiations in the aftermath of the Limitation initiative remained a hypothetical scenario. In sum, our analysis suggests that the capacity of the EU to signal its resolve and to deter further differentiation attempts finds a strong limit in the polarisation of public opinion, yet it may succeed in reducing support for such attempts among the most persuadable voters, especially when they find their country in a comparable situation.

Robustness tests

In the online appendix, we replicate all the analyses with the dependent variable in their original scale (Tables A4 and A5). Moreover, we show that people’s assessments of the relevance of the British Brexit strategy for Switzerland track their evaluations of the impact of Brexit for the UK (Table A6). Finally, to probe a causal interpretation of our findings, in the online appendix we present results from cross-lagged models (see Table A7 and Figure A3). While two-way fixed effects improve our confidence in the estimated coefficients by accounting for time-invariant confounders, they are still prone to issues of reverse causation. For example, voters may change their evaluations of Brexit so as to align them to changes in voting intentions to avoid cognitive dissonance. As cross-lagged models require at least three repeated measures, we focus on voting intentions on the framework agreement. Results show that people changed their referendum vote intentions based on their (previous) evaluations of British strategy, but did not change their evaluations of the British strategy based on their (previous) vote intentions. We find no effect in either causal direction in the case of people’s evaluations of the Brexit impact on the UK.

Conclusions

In response to the recent crises and challenges it faces, the EU overall has become less enthusiastic about differentiated integration, because it has the potential to threaten the EU’s stability. To avoid being confronted with new differentiation bids, the EU therefore has an incentive to signal its resolve not to accommodate further differentiation demands. Ongoing negotiations provide an opportunity to signal such resolve and thus to highlight the risks of refusing to cooperate on the EU’s terms. In this study, we have asked whether and to which extent voters actually observe and act on these signals.

To answer this question, this article has analysed how Swiss voters responded to the Brexit negotiations, one of the biggest popular challenges to the EU to date. We hypothesised that the more the UK was perceived to succeed in the Brexit negotiations with the EU, the more Swiss voters would expect the EU to accept Swiss attempts to increase or maintain differentiation, and that such optimism would make them more likely to vote for such differentiation bids. We measure how Swiss voters perceived the medium-term impact of Brexit on the UK and the relevance of the British strategy for Switzerland, two more recognisable consequences of the EU’s resolve. Our results show that the EU’s non-accommodative strategy was observed in Switzerland, but that it only had a limited though not negligible effect in changing Swiss voters’ expectations and vote intentions.

We study two Swiss differentiation bids that were ongoing at the same time as the Brexit negotiations: A bid to increase differentiation (the Limitation initiative), and opposition to the EU’s efforts to reduce differentiation (the framework agreement). With regard to the Limitation initiative, we found that the Brexit negotiations affected the expectations of the most Eurosceptic voters about the EU’s willingness to accommodate Swiss demands. This would suggest that the EU’s signal was clearly perceived among the people who were the most important target as they were willing to follow a similar path. However, voters did not update their vote intentions in the referendum, thus confirming the difficulty to change opinions on highly politicised issues. In the context of the framework agreement, voters’ changing evaluations of the Brexit experience had an impact on voters with middle positions on Swiss-EU cooperation. These voters, who tend to like to status quo of Swiss-EU relations, updated their expectations about the consequences of an erosion of the bilateral treaties, and also changed their vote intentions in a hypothetical vote on the framework agreement as a result of changes in their assessments of Brexit. The stronger findings for the framework agreement likely reflect that politicians and the media frequently commented on the similarity between the UK-EU Brexit negotiations and the Switzerland-EU framework agreement negotiations.

Of course, even though Switzerland has a close relationship with the EU, it is not an EU member state. As such, it cannot itself exit the EU, and this raises the question to which extent the results of this study travel to other EU countries. To the extent that the issue at stake is the perceived feasibility of differentiation demands vis-à-vis the EU’s resolve not to accommodate such demands, however, we believe that they do hold beyond Switzerland. Our argument applies to all situations where voters seek to increase differentiation with the EU, irrespectively of the current levels of integration of their country with the EU. Previous differentiation attempts such as Brexit thus hold a lesson for differentiation-seeking voters irrespectively of whether they live in an EU member state or not, as similar studies focussed on EU countries underscore (Hobolt et al. Citation2022; Walter Citation2021a). Against this background, our findings have important implications for our understanding of European integration in times of internal contestation and external rebordering.

First of all, our findings shed new light on how growing Euroscepticism creates difficulties for differentiation-seeking voters and elites. As the EU becomes more contested and differentiation becomes riskier for the EU, voters in countries that have so far benefitted from such selective integration are forced to reassess the bargaining space and recalibrate the expected costs of non-cooperation. In this process, other countries’ differentiation attempts, and the subsequent negotiations, become an invaluable source of information. Our findings thus confirm a growing number of studies which show that voters learn from foreign experiences to form political preferences (De Vries Citation2018; Malet Citation2022; Malet and Walter Citation2021; Walter Citation2021a). However, our findings also suggest that the ability of the EU to signal its resolve to differentiation-seeking voters in other countries is limited by the high polarisation of attitudes that nowadays marks public opinion on international cooperation in many European countries. Yet, the deterrence effect of the EU’s non-accommodation stance does resonate among voters with less extreme opinions and may thus prove effective in reducing overall support for further differentiation attempts. Finally, our results suggest a strong link between political dynamics at the centre and at the border of the EU (Bartolini Citation2005; Rokkan Citation1999). While scholars have so far investigated the effect of external debordering on the de-consolidation of the EU’s central power (Schimmelfennig Citation2021; Vollaard Citation2018), our findings highlight that the contestation of the centre also generates political dynamics at the borders.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (555.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Andreas Goldberg, Catherine De Vries, Sara Hobolt, Martijn Huysmans, Miriam Sorace, Waltraud Schelkle, Lora Anne Viola and participants at APSA 2021, EUSA 2022, the INDIVEU workshop in Amsterdam, the Swiss Political Science Conference 2022, and at the online workshops on ‘Causes and Modes of EU Disintegration’ and on ‘The Crisis That Wasn’t? Brexit and Membership Crisis in the European Union’ for very helpful comments and suggestions. Finally, the authors would like to thank Théoda Woeffray, Lukas Stiefel and Nicole Plotke-Scherly for excellent research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Giorgio Malet

Giorgio Malet is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Zurich. He obtained his PhD at the European University Institute. His research focuses on public opinion formation, party competition, and European politics. [[email protected]]

Stefanie Walter

Stefanie Walter is Full Professor for International Relations and Political Economy at the Department of Political Science at the University of Zurich. Her research focuses on distributional conflicts, the political economy of financial crises, and the backlash against globalisation and European integration. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 The process has also been referred to as “differentiated disintegration”, that is, the selective reduction of a state’s level and scope of integration (Schimmelfennig Citation2018: 1154). Of course, Brexit can be also seen as a failure of the differentiation attempt previously made by David Cameron’s government. However, the negotiations that followed the Brexit referendum vote made clear that the British exit was not a wholesale withdrawal, but an attempt to maintain only those links with the EU from which the country was perceived to benefit (see also Gänzle et al. Citation2019, and Schimmelfennig Citation2018).

2 See, for example «Britain mulls Swiss-style ties with Brussels», The Sunday Times 20 November 2022.

4 The initiative followed upon a similar earlier, but failed attempt (Armingeon and Lutz Citation2020).

5 Interview with populist-right MP Roger Köppel https://www.aargauerzeitung.ch/schweiz/svp-nationalrat-roger-koppel-zur-personenfreizugigkeit-das-ist-wie-ein-offener-kuhlschrank-ld.1257277

7 “Was bedeutet der Brexit-Vertrag für die Schweiz?” (Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 8 October 2019), “Die EU und Grossbritannien haben sich in Sachen Brexit geeinigt – es ist eine Lektion für die Schweiz?” (Luzerner Zeitung, 18 October 2019).

10 The questionnaire was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Zurich (approval no. 19.10.12).

11 A fourth wave was added to the original design for panel maintenance following the postponement of the vote on the Limitation initiative, and is not used for the present analyses as it does not include all the relevant questions.

12 Based on data from the Fall 2019 wave (wave 1).

14 In the online appendix (Figure A2), we present histograms of the within-respondents ranges of the main independent variable to get a sense of the relevant shifts that occur in the data.

References

- Adler-Nissen, Rebecca (2014). Opting out of the European Union: Diplomacy, Sovereignty and European Integration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Armingeon, Klaus, and Philipp Lutz (2020). ‘Muddling between Responsiveness and Responsibility: The Swiss Case of a Non-Implementation of a Constitutional Rule’, Comparative European Politics, 18, 256–80.

- Bartolini, Stefano (2005). Restructuring Europe: Centre Formation, System Building, and Political Structuring between the Nation State and the European Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Beach, Derek (2021). ‘If You Can’t Join Them…’: Explaining No Votes in Danish EU Referendums’, in Julie Smith (ed.), The Palgrave Handbook of European Referendums. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 537–52.

- Bisgaard, Martin (2015). ‘Bias Will Find a Way: Economic Perceptions, Attributions of Blame, and Partisan-Motivated Reasoning during Crisis’, The Journal of Politics, 77:3, 849–60.

- Bornschier, Simon (2015). ‘The New Cultural Conflict, Polarization, and Representation in the Swiss Party System, 1975–2011’, Swiss Political Science Review, 21:4, 680–701.

- Christin, Thomas, and Alexander H. Trechsel (2002). ‘Joining the EU? Explaining Public Opinion in Switzerland’, European Union Politics, 3:4, 415–43.

- Dardanelli, Paolo, and Oscar Mazzoleni (2021). Switzerland–EU Relations. Abingdon: Routledge.

- De Vries, Catherine (2017). ‘Benchmarking Brexit: How the British Decision to Leave Shapes EU Public Opinion’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 55, 38–53.

- De Vries, Catherine (2018). Euroscepticism and the Future of European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Emmenegger, Patrick, Silja Häusermann, and Stefanie Walter (2018). ‘National Sovereignty vs. International Cooperation: Policy Choices in Trade-Off Situations’, Swiss Political Science Review, 24:4, 400–22.

- Gänzle, Stefan, Benjamin Leruth, and Jarle Trondal (2019). Differentiated Integration and Disintegration in a post-Brexit Era. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Genschel, Philipp, and Markus Jachtenfuchs (2018). ‘From Market Integration to Core State Powers: The Eurozone Crisis, the Refugee Crisis and Integration Theory’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56:1, 178–96.

- Glencross, Andrew (2019). ‘The Impact of the Article 50 Talks on the EU: Risk Aversion and the Prospects for Further EU Disintegration’, European View, 18:2, 186–93.

- Grynberg, Charlotte, Stefanie Walter, and Fabio Wasserfallen (2020). ‘Expectations, Vote Choice, and Opinion Stability Since the 2016 Brexit Referendum’, European Union Politics, 21:2, 255–75.

- Hobolt, Sara B. (2009). Europe in Question: Referendums on European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hobolt, Sara B., and Catherine de Vries (2016). ‘Public Support for European Integration’, Annual Review of Political Science, 19:1, 413–32.

- Hobolt, Sara B., Sebastian Adrian Popa, Wouter Van der Brug, and Hermann Schmitt (2022). ‘The Brexit Deterrent? How Member State Exit Shapes Public Support for the European Union’, European Union Politics, 23:1, 100–19.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks (2009). ‘A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus’, British Journal of Political Science, 39:1, 1–23.

- Hutter, Swen, Edgar Grande, and Hanspeter Kriesi (2016). Politicising Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jensen, Christian B., and Jonathan B. Slapin (2012). ‘Institutional Hokey-Pokey: The Politics of Multispeed Integration in the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy, 19:6, 779–95.

- Jurado, Ignacio, Sandra Léon, and Stefanie Walter (2022). ‘Shaping Post-Withdrawal Relations with a Leaving State: Brexit Dilemmas and Public Opinion’, International Organization, 76:2, 273–304.

- Kertzer, Joshua D., and Thomas Zeitzoff (2017). ‘A Bottom-Up Theory of Public Opinion about Foreign Policy’, American Journal of Political Science, 61:3, 543–58.

- Kraft, Patrick W., Milton Lodge, and Charles S. Taber (2015). ‘Why People “Don’t Trust the Evidence” Motivated Reasoning and Scientific Beliefs’, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 658:1, 121–33.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter (2007). ‘The Role of European Integration in National Election Campaigns’, European Union Politics, 8:1, 83–108.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, and Alexander H. Trechsel (2008). The Politics of Switzerland: Continuity and Change in a Consensus Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Leuffen, Dirk, Berthold Rittberger, and Frank Schimmelfennig (2013). Differentiated Integration: Explaining Variation in the European Union. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Linos, Katerina (2011). ‘Diffusion through Democracy’, American Journal of Political Science, 55:3, 678–95.

- Malet, Giorgio (2022). ‘Cross-National Social Influence: How Foreign Votes Can Affect Domestic Public Opinion’, Comparative Political Studies, 55:14, 2416–46.

- Malet, Giorgio, and Stefanie Walter (2021). ‘The Reverberations of British Brexit Politics: A Case Study in Voter Cross-National Learning’, unpublished manuscript, Zurich.

- Martini, Marco, and Stefanie Walter (2023). ‘Learning from Precedent: How the British Brexit Experience Shapes Nationalist Rhetoric Outside the UK’, Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2176530

- Matthijs, Matthias, Craig Parsons, and Christina Toenshoff (2019). ‘Ever Tighter Union? Brexit, Grexit, and Frustrated Differentiation in the Single Market and Eurozone’, Comparative European Politics, 17:2, 209–30.

- Oesch, Matthias (2020). Schweiz–Europäische Union: Grundlagen, Bilaterale Abkommen, Autonomer Nachvollzug. Zurich: Buch and Netz.

- Pacheco, Julianna (2012). ‘The Social Contagion Model: Exploring the Role of Public Opinion on the Diffusion of Antismoking Legislation across the American States’, The Journal of Politics, 74:1, 187–202.

- Rokkan, Stein (1999). State Formation, Nation-Building, and Mass Politics in Europe: The Theory of Stein Rokkan: Based on His Collected Works. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schimmelfennig, Frank (2018). ‘Brexit: Differentiated Disintegration in the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:8, 1154–73.

- Schimmelfennig, Frank (2021). ‘Rebordering Europe: External Boundaries and Integration in the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy, 28:3, 311–30.

- Sciarini, Pascal, Simon Lanz, and Alessandro Nai (2015). ‘Till Immigration Do Us Part? Public Opinion and the Dilemma between Immigration Control and Bilateral Agreements’, Swiss Political Science Review, 21:2, 271–86.

- Taber, Charles S., and Milton Lodge (2006). ‘Motivated Skepticism in the Evaluation of Political Beliefs’, American Journal of Political Science, 50:3, 755–69.

- Van Kessel, Stijn, Nicola Chelotti, Helen Drake, Juan Roch, and Patricia Rodi (2022). ‘Eager to Leave? Populist Radical Right Parties’ Responses to the UK’s Brexit Vote’, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 22:1, 65–84.

- Vollaard, Hans (2018). European Disintegration: A Search for Explanations. London: Springer.

- Walter, Stefanie (2020). ‘The Mass Politics of International Disintegration’, unpublished manuscript, Zurich.

- Walter, Stefanie (2021a). ‘Brexit Domino? The Political Contagion Effects of Voter-Endorsed Withdrawals from International Institutions’, Comparative Political Studies, 54:13, 2382–415.

- Walter, Stefanie (2021b). ‘EU-27 Public Opinion on Brexit’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 59:3, 569–88.

- Walter, Stefanie, Elias Dinas, Ignacio Jurado, and Nikitas Konstantinidis (2018). ‘Noncooperation by Popular Vote: Expectations, Foreign Intervention, and the Vote in the 2015 ‘, International Organization, 72:4, 969–94.

- Zemp, Simon D. (2022). ‘Is the Grass Greener on the Other Side of the Channel? How Swiss News Media Presented Brexit as a ‘Benchmark’ for Switzerland’, ARENA Report 5/22. Oslo.