Abstract

Although scholars emphasise the contentious relationship of populist forces to (liberal) democracy, less attention has been paid to whether this extends to those who support or oppose populist parties. This article utilises a public opinion dataset from ten Western European countries to analyse how citizens’ conceptions of democracy relate to the behavioural intention to vote for or against populist parties. The empirical analysis shows that positive and negative identification with populist parties is driven by different understandings of democracy: While individuals who are less inclined to liberal democracy but more to direct democracy and authoritarian forms of rule are more likely to sympathise with populist parties, the opposite understanding of democracy predicts opposition to both left-wing and right-wing populists. These findings demonstrate that citizens with positive and negative partisanship towards populist parties are divided in their interpretations about both the conceptual meaning and the normative functioning of democracy.

Populist parties have not only established themselves across Western Europe but have also been able to enter government in countries as diverse as Austria, Finland, Greece, Italy, Norway, Spain and Switzerland. If it was not yet apparent to some, it is not far-fetched to suggest that populist forces – and their supporters – are here to stay. A broad corpus of research followed, which has so far focussed mainly on two research areas: first, the impact of populist parties on the (democratic) political system; and second, the individual-level determinants driving support for populist parties.

On the one hand, some studies centre on the impact of populist forces on political systems. Populist parties have a problematic relationship to (liberal) democracy, as they represent alternative conceptions of democracy, challenging the apparent post-war consensus of what democracy means and how democracy should function in Western Europe (e.g. Akkerman et al. Citation2016; Katsambekis and Kiopkiolis Citation2019; March Citation2011; Mudde Citation2007). Empirical evidence suggests that populist parties seemingly erode key principles of liberal democracy, most notably its institutional safeguards (e.g. Houle and Kenny Citation2018; Huber and Schimpf Citation2016, Citation2017; Juon and Bochsler Citation2020).

On the other hand, studies are focussed on individual support for populist forces. Scholars show that citizens with very different socio-demographic and socio-political characteristics support populist parties (e.g. Rooduijn Citation2018; Van Hauwaert and van Kessel Citation2018; van Kessel et al. Citation2021). At the same time, however, populist citizens unite in both their abstract support for democracy and their democratic discontent, as they support democracy as the best form of rule but remain dissatisfied with the way democracy works in practice (Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert Citation2020).

While these findings give us important insights into the reasons for the electoral growth of different kinds of populist forces and their impact on the political system, we remain rather limited in our understanding of the potential link between citizens’ conceptions of democracy and their support for and rejection of populist parties. Previous studies indicate that citizens’ preference for referendums and direct democracy increase the likelihood of supporting populist parties (e.g. Bengtsson and Mattila Citation2009; König Citation2022; Steiner and Landwehr Citation2018), and that right-wing populist voters are more likely to support authoritarian forms of rule such as a strong leader (e.g. Donovan Citation2021).

Nevertheless, if we are interested in having in-depth knowledge of the relationship between populism and democracy, it is imperative to provide empirical evidence on the extent to which citizens’ conceptions of democracy are related to both positive and negative partisanship towards populist parties. After all, if the support and rejection of populist forces are driven by different interpretations of what democracy means and how democracy should work, we have different electoral constituencies with conflicting opinions about the criteria that allegedly make a form of government ‘democratic’. In addition to whether the threat to democracy comes primarily from populist parties and their voters, it remains controversial whether those opposing these parties are more likely to protect democracy, which seems particularly relevant for assessing democratic resilience in Western Europe. If that turns out to be true, a regime divide between supporters and opponents of populist parties, guided by contrasting notions of what constitutes a democratic regime, might become a signatory feature of the 21st century and eventually lead to the kind of populist polarisation we are witnessing in various countries today (Enyedi Citation2016; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2018; Roberts Citation2022; Schulze et al. Citation2020).

With the aim of addressing this research gap, we analyse the extent to which citizens’ conceptions of democracy explain positive and negative partisanship towards populist parties. We tackle this question by relying on a recent public opinion dataset from ten Western European countries that allows us to provide novel empirical evidence. Our contribution is divided in four parts. First, we develop a theoretical argument that highlights the relevance and novelty of studying positive and negative partisanship towards populist parties as the dependent variable and citizens’ conceptions of democracy as the main independent variable. Here, we also provide a clear rationale for our proposed causal pathway. We subsequently discuss our study’s research design. The next section shows the empirical analyses and discusses its broader implications. We finally offer a summary of the main findings and set out the future research agenda related to the link between citizens’ conceptions of democracy and supporting and rejecting populist parties.

Support for populist parties and (liberal) democracy

Within the political science literature, there is a growing agreement on an ideational interpretation of populism (Hawkins et al. 2018; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2017). According to this approach, populism is a set of ideas that not only portrays society as divided between ‘the pure people’ and ‘the corrupt elite’ but also defends popular sovereignty at any cost. Conceptualised in this way, there is little doubt that populism maintains a difficult relationship with liberal democracy (Mudde Citation2004; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2017; Plattner Citation2010). The latter is a regime based on the principles of popular sovereignty and majority rule while simultaneously characterised by the existence of independent institutions that limit self-determination (e.g. protection of minorities and delegation of power to non-majoritarian entities).

By raising the question of ‘who controls the controllers’ (Dahl Citation1989), populism is usually at odds with those independent institutions that might interfere with majority rule and popular sovereignty, implying that the ultimate political authority is vested in unelected entities rather than ‘the people’ (Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2014). Seen in this light and opposite to some scholars’ claims, populism is not by default authoritarian. After all, populism plays by the democratic rules of the game, while it nonetheless can end up subverting the liberal democratic regime from within (Canovan Citation1999). In the words of Berman (Citation2017: 30), ‘although it is certainly true that democracy unchecked by liberalism can slide into excessive majoritarianism or oppressive populism, liberalism unchecked by democracy can easily deteriorate into oligarchy or technocracy’.

Because of this intricate relationship between populism and liberal democracy, academics and pundits alike pay increasing attention to the rise of populist forces, which – in turn – combine the populist set of ideas with a ‘host ideology’ to promote political projects that are appealing to larger sections of the electorate. This results in one of two subtypes: right-wing populist parties tend to advance a nationalist interpretation of ‘the pure people’, while left-wing populist parties tend to develop a socialist interpretation of ‘the pure people’ (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2013). Each subtype presents a substantially different understanding of who belongs (and who does not) to ‘the pure people’ and ‘corrupt elite’, but they share the same critical conception of the liberal democratic regime.Footnote1

In fact, several studies examine these differences and similarities between left- and right-wing populist supporters. Rooduijn (Citation2018), for example, shows that populist electorates in Western Europe are quite heterogeneous and therefore we should be careful when talking about ‘the’ populist voter (see also Rooduijn et al. Citation2017; Rooduijn and Burgoon Citation2018). Van Hauwaert and van Kessel (Citation2018) further demonstrate that populist supporters are democratically dissatisfied citizens with high levels of populist attitudes, but with quite dissimilar views on issues related to immigration and socio-economic inequality (see also van Kessel et al. Citation2021; Zanotti et al. Citation2021). Similarly, Rovira Kaltwasser et al. (Citation2019) find that populist supporters have both high levels of populist attitudes and tend to be Eurosceptic, while nonetheless adopting contrasting positions on the economic and cultural political axes. Recent studies find similar observations when examining populist citizens, rather than populist supporters (Habersack and Wegscheider Citation2021; Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert Citation2020; Van Hauwaert et al. Citation2019).

Despite our increasing knowledge on populist support, there remain important unanswered questions in this extensive body of literature. To begin with, scholars have primarily focussed on similarities and differences between populist supporters, i.e. those who favour populist parties, while overlooking what unites and distinguishes those who oppose populist parties. This seems particularly relevant considering research on increased affective polarisation in Western societies showing that positive and negative emotions towards (different) partisans are strongly connected to (negative) behavioural consequences (Reiljan Citation2020; Wagner Citation2021). Simultaneously, there are few studies examining to what extent citizens’ democratic conceptions relate to favouring (or disfavour) populist forces. As we discuss below, it is important to address this lacuna because it can help us understand whether supporting or rejecting populist parties are linked to individual-level notions of what constitutes a ‘democratic’ regime. If conflicting notions of democracy are indeed related to (dis)liking populist forces, they may foster division between citizens who express antagonistic interpretations of what democracy means and how democracy should function. We briefly explain the relevance of these two avenues of research below, highlighting positive and negative partisanship as well as citizens’ conceptions of democracy.

Positive and negative partisanship towards populist parties

Ever since the 1960s, The American Voter has been a classic reference in political science because it demonstrates that partisanship is one of the most important – if not the most significant – variables that explain vote choice (Campbell et al. Citation1960). It gave rise to an immense body of literature about the influence of partisan identities in electoral and political behaviour. Less well known, however, is that The American Voter argues that in order to study partisanship correctly, you have to look at both its positive and negative dimensions. After all, voters might vote for a specific party not only and necessarily because they like that party but also because they dislike its alternative(s). Curiously, most research ignores this relevant distinction and party identification became mostly understood as a positive construct. As Medeiros and Noël (Citation2014) rightly point out, negative party identification is the forgotten side of partisanship – and a crucial dimension when it comes to understanding electoral and political behaviour (Mayer Citation2017). Extant research reveals indeed that negative evaluations and feelings can be more powerful than positive ones, particularly because people tend to give more weight to bad experiences and information than to good (Baumeister et al. Citation2001; Huddy et al. Citation2015).

Regardless of this initial oversight, recent political science research has paid increasing attention to negative party identification. Scholarship from the United States has been at the forefront of this development. This is unsurprising, as the United States is characterised by a bi-partisan political system with increasing levels of (affective) polarisation (Iyengar et al. Citation2019; Iyengar and Krupenkin Citation2018). While positive preference for one party increasingly leads to a negative preference for the alternative, the electoral behaviour of independents is growingly driven by negative rather than positive evaluations of one of the two main political parties (Abramowitz and Webster Citation2016, Citation2018; Bankert Citation2021).

Similar arguments can also be made for the Latin American context. Despite the highly fragmented party system in Brazil, the emergence of one strong party (the centre-left Partido dos Trabalhadores or Workers’ Party) increasingly polarises the electorate and structures political contestation as a struggle between its supporters and detractors (Samuels and Zucco Citation2018). In fact, empirical studies examining Bolsonaro’s 2018 rise to power show that negative partisanship towards the Workers’ Party was one of the most important explanations for his electoral success (Fuks et al. Citation2021; Rennó Citation2020). Similarly, Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser (Citation2019) show high levels of negative partisanship in Chile that structure political competition. More recently, Haime and Cantú (Citation2022) have shown that negative partisanship helps voters in Latin America to distinguish themselves from their non-partisan peers.

While the study of negative partisanship is firmly entrenched in North American scholarship and is slowly becoming more relevant in Latin America (e.g. Meléndez Citation2022), scholars have paid less attention to the role of negative partisanship across Western Europe. This might reflect that measuring positive and negative sentiments in multi-party systems are methodologically more challenging than in two-party systems (e.g. Wagner Citation2021). Yet, recent research has shown that both positive and negative partisanship in Western European multi-party systems entail similar behavioural consequences as in the context of the (US) two-party system (e.g. Harteveld Citation2021; Huddy et al. Citation2018; Mayer Citation2017).

Particularly in Southern Europe, recent studies find that traditional elites gain votes through a combination of their own electoral appeal and the public’s increasing negative partisanship towards opposing political forces (e.g. Orriols and León Citation2020; Tsatsanis et al. Citation2020). In an analysis of 17 European multi-party systems, Mayer (Citation2017) shows that negative partisanship not only has a positive effect on turnout but also influences voting decisions, even when controlling for positive partisanship. Moreover, Spoon and Kanthak (Citation2019) as well as Ridge (Citation2022) show that negative partisanship, especially towards governing parties or major parties, is associated with lower levels of satisfaction with democracy.

Overall, these studies demonstrate that including negative partisanship contributes significantly to a more comprehensive understanding of politics in Western Europe. As longstanding empirical evidence reveals that fewer and fewer Western European citizens develop a positive identity towards parties (Bartolini and Mair Citation1990; Mair Citation2013; Van Hauwaert Citation2015), we could – in consequence – easily anticipate increasing levels of negative partisanship as an explanation for contemporary electoral and political behaviour. While this may be the case for traditional party families across Western Europe, this does not by default translate to populist parties.

Two observations guide our expectations in this regard. First, the transformation of Western European party systems has contributed to the rise and consolidation of populist forces (Kriesi Citation2014; Mair Citation2002), which have been able to attract both defectors from traditional party families and new voter groups. At least for right-wing populist parties, we also know that their electorates are surprisingly loyal (Harteveld et al. Citation2022; Voogd and Dassonneville Citation2020). We therefore expect comparatively high levels of positive partisanship towards populist parties, most notably right-wing ones. Second, populist parties systematically challenge the electoral dominance of traditional parties and put the status quo under stress (Rueda Citation2005). They are not just seen as ‘outsiders’ but as a structural strain and perhaps even a threat to the democratic system (Houle and Kenny Citation2018; Huber and Schimpf Citation2016, Citation2017; Juon and Bochsler Citation2020). This suggests relatively high levels of negative partisanship towards populist parties.

Yet, we have limited knowledge about the extent to which voters in Western Europe support and reject these parties. Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser (Citation2021) show that large parts of national electorates in Western Europe both like and dislike right-wing populist parties. The study further finds that voters who are hostile to right-wing populist parties have a clear affinity with the democratic regime and its liberal-democratic implementation. Harteveld (Citation2021) shows that the polarisation in the Netherlands is particularly strong between supporters and opponents of right-wing populist parties. The finding that right-wing populist parties both radiate and receive high levels of dislike is also confirmed in an analysis of 28 European countries (Harteveld et al. Citation2022).

Building on the findings of these contributions and with the aim of providing evidence beyond them, we explore the extent of positive and negative partisanship towards populist parties across Western Europe as well as towards right-wing and left-wing populist parties separately. Specifically, we explore whether citizens’ conceptions of democracy are an important distinguishing feature between supporters and opponents of populist parties, which can deepen our understanding of democratic resilience in Western Europe.

Citizens’ conceptions of democracy and partisanship towards populist parties

There is no scarcity of empirical studies on support for populist parties. They highlight two main differences between left-wing and right-wing supporters. First, research shows that anti-immigration sentiments, as well as authoritarian and social conservative positions, are the main drivers of right-wing populist support (e.g. Dunn Citation2015; Ivarsflaten Citation2008; van der Brug et al. Citation2000). Second, studies demonstrate that support for left-wing populists is primarily explained by left-wing economic policy preferences, such as state intervention in the economy (Gomez et al. Citation2016; Ramiro Citation2016), but also by the endorsement of egalitarian values, such as gender equality and social liberal values (Marcos-Marne et al. Citation2020, Citation2021). These empirical findings also suggest that it might be inaccurate to speak of ‘the’ populist supporter, as this group tends to be composed of different constituencies representing dissimilar positions on several of the issues that structure political contestation (Rooduijn Citation2018).

Positive partisanship towards populist parties

Despite their idiosyncratic nature, populist supporters effectively share and articulate a populist critique against the establishment and the liberal democratic model. The very fact that populist supporters – despite crucial ideological and behavioural differences – share high levels of populist attitudes reveals that they have a complex relationship with democracy. Van Hauwaert and van Kessel (Citation2018) find that populist supporters across Europe not only share high levels of populist attitudes but are also generally dissatisfied with democracy. Additionally, Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert (Citation2020) show that populist citizens across Europe and Latin America share one very important similarity: They support democracy as a regime but are dissatisfied with the functioning of democracy in practice. This suggests that populist citizens are dissatisfied democrats and want to promote reforms with the aim of ‘democratising democracy’.

This observation, however, comes with important constraints. Most importantly, extant research (e.g. Carlin and Singer Citation2011; Schedler and Sarsfield Citation2007) highlights that diffuse support for democracy is an unreliable measure of the extent to which citizens consider (liberal) democracy as ‘the only game in town’ (Linz and Stepan Citation1996: 15). As Canache (Citation2012: 1133) rightly points out, ‘the adoption of norms, practices and institutions that delineate the liberal architecture of current democratic systems does not imply that all citizens in every nation exclusively endorse a liberal view’ (italics in original). Moreover, we know that democratic regime support is not only very stable (Magalhães Citation2014) but also strongly dependent on its effectiveness (Dahlberg and Holmberg Citation2014; Klingemann Citation1999) and performance (Curini et al. Citation2012; Wagner et al. Citation2009).

Considering that there is systematic evidence that populist actors pose a threat to the liberal democratic regime (Houle and Kenny Citation2018; Huber and Schimpf Citation2016, Citation2017; Juon and Bochsler Citation2020) and can even contribute to democratic breakdown (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2017; Ruth Citation2018), it is particularly important to examine what understanding of democracy shapes citizens’ positive partisanship towards populist parties. While evidence suggests that populist citizens endorse democracy as a regime type and support it in an abstract sense, we know relatively little about the extent to which support for or opposition to specific aspects of democracy promotes support for populist forces. These findings are important in assessing whether populist supporters abandon populist parties in light of increased illiberalism because of their continued belief in liberal democracy, or whether populist supporters remain loyal due to converging illiberal ideas about democracy. Furthermore, given their overall levels of discontent (Rooduijn et al. Citation2016; Van Hauwaert and van Kessel Citation2018), it is also important to understand why exactly populist supporters are dissatisfied with the current implementation of democracy. This study therefore examines how citizens’ conceptions of democracy relate to positive identification with populist forces.

Drawing from extant literature, we expect that those sceptical about the basic principles of liberal democracy are more likely to have a positive identification towards populist parties (Berman Citation2017; Mudde Citation2004; Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2012; Zanotti and Rama Citation2021). At the same time, we anticipate that preferring more direct popular participation as an alternative mode of decision making should be linked to a positive identification towards populist parties, as direct democratic mechanisms can help to allegedly represent the will of ‘the pure people’ more truthfully and challenge ‘the corrupt elite’ (Heinisch and Wegscheider Citation2020; Jacobs et al. Citation2018; Zaslove et al. Citation2021). While studies suggest that citizens who support authoritarian forms of rule such as a strong leader are more likely to support right-wing populist parties (e.g. Donovan Citation2021), we do not know whether this applies to populist parties in general or is mainly due to their connection to a right-wing host ideology. Similarly, we remain cautious about expectations of supporters of an egalitarian model of democracy, which might be associated with a positive identification with left-wing populist parties but a rejection of right-wing populist parties due to opposing positions on economic and social equality.

Negative partisanship towards populist parties

Following on from this, the opposite exercise of what understanding of democracy motivates negative identification with populist parties is more intricate. This is not only because there are so few studies on negative partisanship towards populist forces but also – perhaps more importantly – because studies on negative partisanship emphasise that it is not simply the mirror image of positive partisanship (Bankert Citation2021). It is a separate and distinct concept, meaning that ‘hating’ one party does not automatically imply ‘loving’ another. This argument is particularly true in multi-party systems where citizens can choose between many political parties (Rose and Mishler Citation1998). With this in mind, we have only rather tentative expectations about the potential linkage between citizens’ conceptions of democracy and negative partisanship towards populist forces.

Overall, we expect citizens’ conceptions of democracy to help distinguish those with a positive and negative identity towards populist forces, thus forming two distinct electoral constituencies. While previous research remains relatively silent on the theoretical foundations underlying these differences, we can nonetheless expect one notable difference. Theoretical debates on populism suggest that by politicising issues that have been ignored – deliberately or not – by the establishment and by developing a fierce rhetoric, populist forces are able to polarise the electorate into those who are in favour of and oppose the populist project, which is at odds with the liberal-democratic implementation of democracy. Laclau (Citation2005) and Mouffe (Citation2000) indeed argue that a lack of polarisation – the idea that ‘there is no alternative’ to the market economy – has paved the way for the emergence of different kinds of populism that foster the construction of alternative models of democracy that depart from the liberal standard. We therefore expect that those who endorse the typical liberal understanding of democracy that we observe across Western Europe are more likely to oppose populist forces. Against this background, our assumption is that the distinction between positive and negative partisanship towards populist forces is underpinned by the conflict around the post-war consensus of what democracy means across Western Europe.

Two causal pathways

In the theoretical framework, we discuss the relationship between different conceptions of democracy and positive and negative partisanship towards populist parties. This connection resonates with the idea of institutional and democratic learning, according to which regime preferences reflect prior experiences with democracy that crystalise during socialisation but can adapt and change based on more recent experiences with the democratic decision-making process (e.g. Dalton et al. Citation2007). As the rise of populist beliefs is often seen as the result of a lack of representation and policy failure (e.g. Castanho Silva and Wratil Citation2023; Hawkins et al. 2018; Huber et al. Citation2023), it might induce citizens to become sceptical of the liberal model of democracy and to endorse alternatives forms of decision making, which are exploited and mobilised by populist forces.

Although this represents our research puzzle and contribution to the literature, it does not mean that there is no causal effect from the dependent variables (i.e. positive and negative partisanship towards populist parties) to the main independent variable (i.e. citizens’ conceptions of democracy). It may very well be that partisanship, both in terms of its direction and its strength, can influence citizens’ understanding of democracy, and even more, we recognise this as likely. After all, we know that political parties shape the agenda and can impact the salience of certain issues (e.g. Dennison and Geddes Citation2019; Wagner and Meyer Citation2014). Furthermore, given that populist parties reject pluralism and advocate ‘better’ (i.e. more direct) representation, it seems at least plausible, if not likely, that the messages of populist parties also affect how their partisans think of democracy.

With this in mind, it is important to emphasise that we are only examining one part of a more intricate link between conceptions of democracy and partisanship, which certainly runs in both directions. To a certain extent, this connection can be seen as a kind of ‘chicken & egg’ problem. On the one hand, populist parties promote a specific understanding of democracy that appeals to their voters. On the other hand, populist voters have a peculiar notion of democracy that they mirror in the agenda of populist parties. Moreover, once populist parties enter the electoral arena, non-populist parties can emphasise that they are defending the classic liberal understanding of democracy, which is now under threat, and might drive negative partisanship towards populist parties, particularly among voters who endorse the liberal concept of democracy. However, as we explain below, our data is not longitudinal, and we therefore provide correlational evidence rather than a causal explanation. We return to this point in the conclusion, where we outline potential avenues for future research on this topic.

Data and method

We rely on survey data from ten Western European countries: Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom.Footnote2 These countries represent the historical, economic, regional and political diversity of Western Europe and include both established prototypical and more recently successful populist parties.

Positive and negative partisanship towards populist parties

We draw on The PopuList to distinguish whether a party is populist or not, while also further differentiating between left-wing and right-wing populist parties (Rooduijn et al. Citation2019). provides an overview of populist parties in our sample countries, as well as a further distinction whether they can be considered left-wing or right-wing.

Table 1. Classification of populist parties.

While the classification of populist parties is relatively straightforward, assessing partisanship towards them is more complex as there is no formal or standardised measurement. However, this is not necessarily problematic, as different measurements can function differently in certain contexts (e.g. two-party versus multi-party systems) and can help illuminate different intensities of partisanship (e.g. strong versus weak). Overall, scholars rely on one of two approaches to measure partisanship: either they adopt the feeling-thermometer approach, in which voters indicate how much they (dis)like political parties (Richardson Citation1991), or they employ a group identity approach, in which voters identify parties for which they would (never) vote (Rose and Mishler Citation1998; Samuels and Zucco Citation2018).

While both approaches have their merits, we rely on the group-identity approach for two interrelated reasons – one pragmatic and the other conceptual. On the one hand, we are interested in getting information about those who have strong feelings towards populist parties, and therefore whether they would never (always) vote for these parties is a good proxy to measure rejection (approval). On the other hand, given that we conceptualise partisanship as a stable psychological (dis)affection for a specific political party (Campbell et al. Citation1960), a measurement capturing positive or negative evaluations of a populist party is particularly relevant.

Henceforth, we rely on the question of how likely respondents are to cast their vote for a particular party. The variable contains a four-point scale, ranging from ‘would definitely not vote’ (1) to ‘would definitely vote’ (4). Additionally, we also consider the complexity of European electoral arenas by measuring the variable in three electoral arenas: the European Parliament, the national parliament, and the regional parliament (or the local parliament in cases where there is no regional parliament). We subsequently operationalise partisanship towards populist parties as follows. Those who respond that they ‘would rather’ or ‘definitely vote’ for a populist party in all three elections have a positive partisanship towards populist parties. Those who respond that they ‘would rather not’ or ‘definitely not vote’ for a populist party in all three elections are considered to have a negative identity towards populist parties. This particular approach captures positive and negative partisanship across consistent party preferences, i.e. those who support or reject a populist party in all three electoral arenas simultaneously.Footnote3

Conceptions of democracy

Drawing on the debate over how democracy should be conceptualised (Dahl Citation1989) and in line with to the 2012 European Social Survey (Ferrín and Kriesi Citation2016), our survey includes 12 items that capture citizens’ conceptions of democracy across Western Europe (see ). Respondents were asked on an eleven-point scale from ‘not at all important’ (0) to ‘very important’ (10) how important they consider certain elements of democracy.

Table 2. Measuring citizens’ conceptions of democracy.

presents an exploratory factor analysis of these 12 democracy indicators to examine how citizens conceptualise democracy. The results show that the items are structured into four factors. The first factor includes characteristics of the electoral and liberal dimensions of democracy. This might be surprising, as theoretical debates typically separate electoral and liberal components of democracy. However, it seems that citizens do not make this conceptual distinction, as the factor analysis reveals that the survey items designed to measure these two regime types are considered as a singular democratic concept. The second factor measures an egalitarian conception of democracy. Interestingly, the item on minority rights, which is usually seen as a component of liberal democracy, aligns with two items on economic equality. This suggests that from the perspective of Western European citizens, egalitarian democracy is not only about providing social protection (economic issues) but also about respecting minorities (cultural issues). Again, this is not particularly surprising given that liberal and egalitarian democracy is the norm in most – if not all – countries in our sample. The third factor measures the preference for direct democratic measures such as referendums and impeachment procedures. The fourth factor includes preferences for authoritarian forms of rule such as an unconstrained leader as well as military rule. We use factor scores to estimate support for each dimension, with higher scores indicating higher support.

Control variables

While we are mainly interested in the relationship between citizens’ conceptions of democracy and negative and positive partisanship towards populist parties, our analysis also accounts for a number of control variables. As an important explanation for the support of populist forces, we include a populist attitudes scale (Van Hauwaert et al. Citation2018, Citation2020). We also approximate respondents’ ‘host ideologies’ by including various scales that capture specific economic, cultural and immigration-related preferences. Higher values mean economically liberal, culturally conservative and anti-immigrant positions. In addition, we use an eleven-point scale to measure respondents’ left–right self-placement as well as an item that captures Euroscepticism, measured by their rejection of their country’s membership in the European Union. We also include separate indicators of democratic satisfaction and political interest. Finally, we include a range of socio-demographic controls, such as age, gender and education. We refer to the online appendix for further details on the question wordings, factor analyses and descriptive statistics of all these control variables.

Analysis and discussion

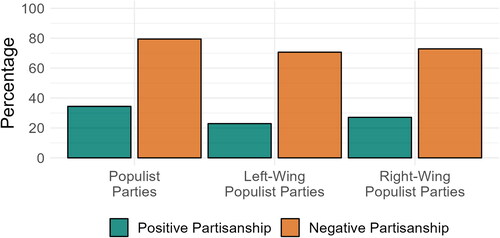

presents the percentage of respondents with positive and negative partisanship towards populist parties within our sample. It reveals that the number of respondents with an aversion to populist parties (about 80%) significantly exceeds the number who support them (about 35%). More specifically, it also shows that while a relatively higher share of respondents identifies positively with right-wing than with left-wing populist parties, there is slightly more disapproval of right-wing populists (see also Harteveld et al. Citation2022). It is therefore not far-fetched to claim that populist parties have an apparent electoral ceiling. That is, they face an uphill battle to expand their electoral base beyond their current core constituencies, simply because of the electorate is so polarised towards them (Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2021).

Figure 1. Positive and negative partisanship towards populist parties.

Notes: Percentages do not add to 100 because individuals in countries with more than one populist party can have both positive and negative partisanship. Percentages for partisanship towards left-wing populist parties refer only to countries with these parties in parliament (France, Germany, Greece, the Netherlands and Spain). Percentages for partisanship towards right-wing populist parties allude to all countries except Greece. The online appendix includes figures with a comparison to all party families and non-populist parties.

Conceptions of democracy and partisanship towards populist parties

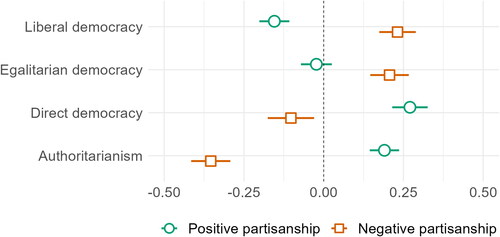

We further explore the observations from and scrutinise the origins of both groups by conducting a multivariate analysis. shows how the four conceptions of democracy are related to positive and negative partisanship towards populist parties. After all, it is important that we understand the democratic profile that informs positive and negative partisanship so that we can assess how wide the gulf is between them and, more importantly, how we might bridge the gap between them.

Figure 2. Citizens’ conceptions of democracy and partisanship towards populist parties.

Notes: Plot shows standardised coefficients with 95% confidence intervals and robust standard errors from logistic regression models with country-fixed effects. Full models are reported in the online appendix.

The effects of each conception of democracy return an interesting finding. First, the more respondents support liberal democracy, the less likely they are to identify positively with populist parties and the more likely they are to identify negatively with them. Accordingly, individuals’ commitment to the liberal ideal of democracy serves as a key differentiator between those who support and oppose populist parties. In other words, those who tend to have a certain disdain for decision making by elected representatives and judicial control of political decisions are more likely to identify with populist parties. While we know that populism has a complicated relationship with liberal democracy on a conceptual and party-level (e.g. Huber and Ruth Citation2017; Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2012), we show that this distrust of the liberal components of democracy also translates to citizens who identify with populist parties.

The results on egalitarian democracy are less revealing. While suggests that there is no necessary relationship between an affinity towards egalitarian democracy and positive partisanship towards populist parties, we also find that it increases the likelihood of rejecting populist parties. Although several scholars posit that social democracy in Europe might be retrenching (e.g. Benedetto et al. Citation2020), it remains widely embedded across the various Western European countries we include in our analysis. With that in mind, it appears that most Western Europeans consider egalitarian democracy as so deeply rooted in democracy that it is almost a necessary or natural part of it, i.e. something at the heart of Western European democracy which they want to see maintained. While this observation is perhaps not too surprising, it is nonetheless worth exploring in more detail, most notably by disaggregating the types of populist parties that people oppose or support.

also highlights that support for direct democracy significantly contributes to the distinction between positive and negative partisanship towards populist parties. More precisely, those more supportive of direct democratic tools are more likely to positively identify with populist parties, while those opposing a more direct democratic form and – by proxy – have more trust in their representatives to make decisions are more likely to negatively identify with populist parties. Although the populists’ desire for more direct democracy is widely established in the literature, both theoretically (Canovan Citation1999; Mudde Citation2004) and empirically (Jacobs et al. Citation2018; Mohrenberg et al. Citation2021), the finding that hostility of direct democracy is associated with rejection of populist parties is novel. This is certainly in part due to the increasing affinity towards elitism and technocratic solutions among mainstream voters (Bertsou and Caramani Citation2022; Bertsou and Pastorella Citation2017). Moreover, some of the recent findings related to supposed tensions between existing processes of representative democracy and reformers’ calls for more participatory or deliberative forms of democracy are put into perspective. After all, at least those citizens rejecting populist forces might not place so much value on more opportunities to participate in the political process, or they simply fear that populist forces will hijack these direct instruments as strategic opportunities for involvement.

A final take-away from is that the more people reject authoritarian forms of rule, the more likely they are to be hostile to populist parties, while the more important authoritarian procedures are for a person, the more they tend to identify with populist parties. The support for and rejection of authoritarian forms of rule thus contributes significantly to the division between partisans and opponents of populist parties. While the desire to limit the democratic powers of the legislature and executive in favour of unconstrained leaders and military rule contributes significantly to a positive identification with populist parties, we must also be careful not to confuse authoritarianism and populism. Despite some rather crude claims of deconsolidation following an alleged tendency of European electorates to be, or rather to become, more authoritarian (Foa and Mounk Citation2016, Citation2017), there appears to be no real trend towards authoritarian forms of rule amongst the broader electoral cohorts and most notably those citizens who reject populist parties (see also Alexander and Welzel Citation2017; Welzel Citation2021; Wuttke et al. Citation2022).

Conceptions of democracy and partisanship towards left-wing and right-wing populist parties

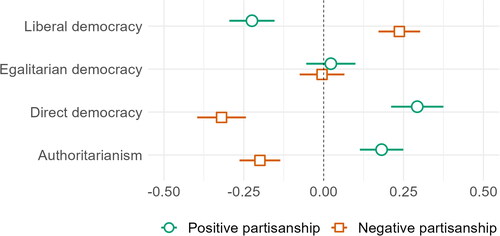

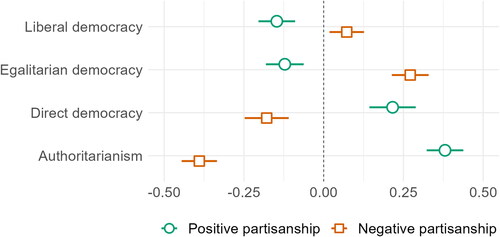

Given the heterogeneity within the populist party family, and further distinguish between positive and negative partisanship for left-wing and right-wing populist parties, respectively. This allows us to get a more fine-grained sense of how citizens’ understanding of democracy might relate to their support for and rejection of different kinds of populist parties.

Figure 3. Citizens’ conceptions of democracy and partisanship towards left-wing populist parties.

Notes: Plot shows standardised coefficients with 95% confidence intervals and robust standard errors from logistic regression models with country-fixed effects. Full models are reported in the online appendix.

Figure 4. Citizens’ conceptions of democracy and partisanship towards right-wing populist parties.

Notes: Plot shows standardised coefficients with 95% confidence intervals and robust standard errors from logistic regression models with country-fixed effects. Full models are reported in the online appendix.

shows the effects of the four conceptions of democracy for positive and negative partisanship towards left-wing populist parties. Following the previous results, the analysis reveals that those who are less in favour of liberal democracy and more in favour of direct democracy are more likely to identify with left-wing populist parties. Accordingly, those critical of the principles of liberal democracy, while favouring the inclusion of the people in the political decision-making process over constitutional controls, are more likely to have a positive identity towards left-wing populist parties. At the same time, the opposite understanding of democracy contributes to a rejection of left-wing populist parties. Considering that these two democratic components relate very strongly to populism and not directly to the host ideology, it is not that surprising that this resembles the results from .

Much more surprising, however, is that we find no significant relationship between the importance of egalitarian democracy and supporting or rejecting left-wing populist parties. Accordingly, support for the promotion of equality for underprivileged groups does not seem to contribute to a distinction between positive and negative partisanship towards populist parties. While this remains a tentative explanation, we might argue that – especially across Western Europe – an egalitarian component is so firmly embedded in our current understanding of democracy that few non-populists and left-wing populist would argue against it. Whether this result also applies to partisanship towards right-wing populist parties will be analysed in a next step.

Finally, although we had no specific expectations as to whether support for authoritarian forms of rule has an impact on support for left-wing populist parties, as seems to be the case for right-wing populist parties (e.g. Donovan Citation2021), we show that support for unconstrained leaders and military rule contributes significantly to the distinction between positive and negative partisanship of left-wing populist parties. This might reflect not only that most populist parties – even left-wing ones – have a relatively narrow hierarchy with strong or at least clearly identified and visible leadership but also show a certain contempt for the legislature and the executive as important democratic institutions.

shows how the four conceptions of democracy relate to positive and negative partisanship towards right-wing populist parties. In line with the observations from and , we find that those who are more in favour of liberal democracy and less in favour of direct democracy are more likely to oppose right-wing populist parties. Although the differences seem less pronounced, support for liberal democracy and direct democracy contributes significantly to the distinction between positive and negative partisanship towards right-wing populist parties. While this is a common finding among right-wing populist candidates and parties, we knew much less about whether this also translates to their electoral base and those opposing these parties.

further indicates that those who support the inclusion and empowerment of economically and socially disadvantages groups are more likely to oppose right-wing populist parties. This probably stems from the clearly exclusionary right-wing host ideology in terms of providing support to marginalised groups, which contrasts with the aforementioned longstanding tradition of social democracy in Western Europe. In turn, those who are less supportive of egalitarian democracy are more likely to have a positive identity towards right-wing populist parties, perhaps because they equate (or conflate) social and nativist interpretations of inequality. That is, they often combine a preference for redistributive policies with a rather exclusionary idea of who can benefit from them. This suggests that those giving less credence to egalitarian democracy are more likely to identify with right-wing populist parties, which in turn suggests that both parties and partisans endorse welfare chauvinism.

Previous research already highlighted that those supporting right-wing populist parties tend to be more authoritarian in their worldview (Van Hauwaert and van Kessel Citation2018). further supports this result, as we find clear evidence that those who attach more importance to authoritarian procedures are more likely to identify with right-wing populist parties. This might reflect a preference for a clear-cut hierarchical structure, but also a disdain for key democratic institutions such as democratically elected parliaments and governments. In contrast, people who are supportive of authoritarian forms of rule are significantly less likely to oppose right-wing populist parties. Preferences for authoritarianism thus also clearly distinguish between positive and negative partisanship for right-wing populist parties.

Conclusion

Despite increasing academic interest in populist parties across Western Europe, little attention has been paid to how citizens’ conceptions of democracy relate to positive and negative identification towards populist parties. We seek to fill this research gap by analysing a novel dataset covering ten Western European countries. In fact, we are able to present rich empirical evidence on how support for four different regime concepts – liberal democracy, egalitarian democracy, direct democracy and authoritarianism – relates to positive and negative partisanship towards different kinds of populist forces. The ensuing results are threefold.

First, citizens in Western Europe conceptualise democracy differently from how the concept of democracy is usually presented in academic debates. While scholars usually distinguish between electoral and liberal democracy, citizens consider these two concepts to be one and the same. In addition, seen through the eyes of citizens, minority rights are part of an egalitarian model of democracy that fosters a better integration of underprivileged groups of the population. Consequently, citizens in Western Europe consider egalitarian democracy as a type of democracy characterised by the protection of both socio-economic and socio-cultural principles.

Second, those who are less in favour of liberal democracy and more in favour of direct democracy are more likely to identify with populist parties in general and left-wing and right-wing populist parties more specifically. In contrast, the opposite understanding of democracy explains opposition towards both left-wing and right-wing populist parties. We thus clearly show that the scepticism of populist parties towards liberal democracy also translates to the level of citizens and positive partisanship towards populist parties. Thus, support for the liberal principles of democracy contributes significantly to a divide between those who support and oppose populist parties. Moreover, endorsing direct democratic mechanisms is also significantly linked to the support and rejection of populist parties. While this finding can be related to the emphasis populist parties put on respecting popular sovereignty at any cost and their usual demand to undertake referendums to give voice to the ‘silent majority’, we nonetheless believe further research into this relationship is necessary to uncover its intricacies. For instance, the link between favouring direct democracy and supporting populist forces might be related to the fact that the latter are usually in opposition; once in government, and particularly if they can stay in power for a long time, it might be that both the parties and their supporters not emphasise direct democratic mechanisms as much, since the government now represents ‘the pure people’, so there is no need to activate popular sovereignty.

Third, while support for egalitarian democracy contributes primarily to the distinction between opponents and supporters of right-wing populist parties, support for authoritarian forms of rule helps significantly to distinguish between positive and negative identification with both left-wing and right-wing populist parties. These empirical findings can therefore be interpreted both as a sign of democratic resilience and increasing polarisation around the notion of democracy in Western Europe. As the rejection of authoritarianism and the defence of liberal principles of democracy are linked with opposition of populist parties of different kinds, there seems to be a significant part of the population committed to the post-war consensus on what democracy means and how it should work in Western Europe.

On a final note, we emphasise that studies on negative partisanship are still in their infancy in Western Europe. Given that the number of people who positively identify with political parties is clearly diminishing across the region, future research on negative partisanship can shed light on the ways in which citizens are relating to political parties nowadays. This means that we need more analyses and new data on both positive and negative partisanship in Western Europe. In this context, it would be particularly interesting to develop longitudinal data in order to examine the stability of negative partisanship (towards populist parties). For instance, one might assume that populist parties could increase their legitimacy by forming a government coalition with mainstream parties, thereby reducing the level of negative partisanship.

However, it is not clear that those who have a positive identity towards populist parties would change their understanding of democracy once populist forces come to power. To answer these kinds of questions, it is crucial to have longitudinal data on positive and negative partisanship as well as on citizens’ conceptions of democracy. This kind of data could also help to better understand the two causal pathways discussed earlier: populist parties might promote a specific understanding of democracy that their voters find appealing, while populist voters probably advance a peculiar notion of democracy that they mirror in the ideas developed by populist parties. If this argument holds true, Western European societies might experience the rise of a regime divide between those who favour and oppose populist parties holding contrasting notions of what constitutes a democratic regime in the 21st century.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (659.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Robert Huber, Markus Wagner, Zoe Lefkofridi, and Ann-Kristin Kölln as well as the anonymous reviewers and the editors for their valuable comments and suggestions on the article. Earlier versions of the paper were presented at the ECPR General Conference 2020 and at the Jour Fixe of the Cluster of Excellence ‘Contestations of the Liberal Script’ (SCRIPTS) in 2021, where we received valuable feedback from various colleagues, including Tanja Börzel, Heike Klüver, Jan-Werner Müller, Thomas Risse, and Michael Zürn.

Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser acknowledges the support from Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (FONDECYT Project 1220053), the Centre for Social Conflict and Cohesion Studies (COES; CONICYT/FONDAP/151330009), and the Observatory for Socioeconomic Transformations (ANID/PCI/Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies/MPG190012).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Carsten Wegscheider

Carsten Wegscheider is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Department of Political Science at the University of Münster. His main area of research is comparative politics with an interest in democratisation, populism and political behaviour. [[email protected]]

Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser

Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser is Professor of Political Science at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (UC) and Universidad Diego Portales (UDP) and Associate Researcher at the Centre for Social Conflict and Cohesion Studies (COES). He is the co-author, with Cas Mudde, of Populism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2017) as well as the co-editor, with Tim Bale, of Riding the Populist Wave. Europe’s Mainstream Right in Crisis (Cambridge University Press, 2021). [[email protected]]

Steven M. Van Hauwaert

Steven M. Van Hauwaert is an Excellence Fellow at Radboud University and an Associate Professor in Comparative Politics at Forward College Paris. His research interests focus on how different components of democracy interact with one another and how they get challenged or potentially challenge each other. The corresponding research has appeared in the European Journal of Political Research, Politics, West European Politics, European Political Science Research, the International Journal of Public Opinion Research, and the Journal of European Public Policy, amongst others. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 For an interesting discussion on populist governments and their impact on different models of democracy, see Ruth-Lovell and Grahn (Citation2022).

2 The survey was conducted online by YouGov in January 2019 on behalf of the Bertelsmann Foundation. National samples are representative of the respective eligible population for the 2019 European Parliament elections and have been stratified according to official socio-demographic distributions (age, gender, education, region) using census data provided by Eurostat.

3 We operationalise partisanship in a conservative manner, using a rather exclusive and rigid set of criteria. This allows us to be more confident in our claims based on the results of the analysis. However, to further validate our findings, we also used a more flexible operationalization of partisanship by relying only on the national election variable. The results remain substantively similar to the more conservative operationalisation.

References

- Abramowitz, Alan, and Steven Webster (2016). ‘The Rise of Negative Partisanship and the Nationalization of U.S. Elections in the 21st Century’, Electoral Studies, 41, 12–22.

- Abramowitz, Alan, and Steven Webster (2018). ‘Negative Partisanship: Why Americans Dislike Parties but Behave like Rabid Partisans’, Advances in Political Psychology, 39:S1, 119–35.

- Akkerman, Tjitske, Sarah de Lange, and Matthijs Rooduijn (2016). Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Alexander, Amy C., and Christian Welzel (2017). ‘The Myth of Deconsolidation: Rising Liberalism and the Populist Reaction’, Journal of Democracy. https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/online-exchange-democratic-deconsolidation/

- Bankert, Alexa (2021). ‘Negative and Positive Partisanship in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Elections’, Political Behavior, 43:4, 1467–85.

- Bartolini, Stefano, and Peter Mair (1990). Identity, Competition, and Electoral Availability: The Stabilisation of European Electorates – 1885–1985. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Baumeister, Roy, Ellen Bratslavsky, Catrin Finkenauer, and Kathleen D. Vohs (2001). ‘Bad is Stronger than Good’, Review of General Psychology, 5:4, 323–70.

- Benedetto, Giacomo, Simon Hix, and Nicola Mastrorocco (2020). ‘The Rise and Fall of Social Democracy, 1918–2017’, American Political Science Review, 114:3, 928–39.

- Bengtsson, Asa, and Mikko Mattila (2009). ‘Direct Democracy and Its Critics: Support for Direct Democracy and “Stealth” Democracy in Finland’, West European Politics, 32:5, 1031–48.

- Berman, Sheri (2017). ‘The Pipe Dream of Undemocratic Liberalism’, Journal of Democracy, 28:3, 29–38.

- Bertsou, Eri, and Daniele Caramani (2022). ‘People Haven’t Had Enough of Experts: Technocratic Attitudes among Citizens in Nine European Democracies’, American Journal of Political Science, 66:1, 5–23.

- Bertsou, Eri, and Giulia Pastorella (2017). ‘Technocratic Attitudes: A Citizens’ Perspective of Expert Decision-Making’, West European Politics, 40:2, 430–58.

- Campbell, Angus, Philip E. Converse, Warren E. Miller, and Donald E. Stokes (1960). The American Voter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Canache, Damarys (2012). ‘Citizens’ Conceptualizations of Democracy: Structural Complexity, Substantive Content, and Political Significance’, Comparative Political Studies, 45:9, 1132–58.

- Canovan, Margaret (1999). ‘Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy’, Political Studies, 47:1, 2–16.

- Carlin, Ryan E., and Matthew W. Singer (2011). ‘Support for Polyarchy in the Americas’, Comparative Political Studies, 44:11, 1500–26.

- Castanho Silva, Bruno, and Christopher Wratil (2023). ‘Do Parties’ Representation Failures Affect Populist Attitudes? Evidence from a Multinational Survey Experiment’, Political Science Research and Methods, 11:2, 347–62.

- Curini, Luigi, Willy Jou, and Vincenzo Memoli (2012). ‘Satisfaction with Democracy and the Winner/Loser Debate: The Role of Policy Preferences and Past Experience’, British Journal of Political Science, 42:2, 241–61.

- Dahl, Robert (1989). Democracy and Its Critics. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Dahlberg, Stefan, and Sören Holmberg (2014). ‘Democracy and Bureaucracy: How Their Quality Matters for Popular Satisfaction’, West European Politics, 37:3, 515–37.

- Dalton, Russell J., To-chʻŏl Sin, and Willy Jou (2007). ‘Understanding Democracy: Data from Unlikely Places’, Journal of Democracy, 18:4, 142–56.

- Dennison, James, and Andrew Geddes (2019). ‘A Rising Tide? The Salience of Immigration and the Rise of Anti‐Immigration Political Parties in Western Europe’, The Political Quarterly, 90:1, 107–16.

- Donovan, Todd (2021). ‘Right Populist Parties and Support for Strong Leaders’, Party Politics, 27:5, 858–69.

- Dunn, Kris (2015). ‘Preference for Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties among Exclusive-Nationalists and Authoritarians’, Party Politics, 21:3, 367–80.

- Enyedi, Zsolt (2016). ‘Populist Polarization and Party System Institutionalization’, Problems of Post-Communism, 63:4, 210–20.

- Ferrín, Mónica, and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. (2016). How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Foa, Roberto S., and Yascha Mounk (2016). ‘The Democratic Disconnect’, Journal of Democracy, 27:3, 5–17.

- Foa, Roberto S., and Yascha Mounk (2017). ‘The Signs of Deconsolidation’, Journal of Democracy, 28:1, 5–15.

- Fuks, Mario, Ednaldo Ribeiro, and Julian Borba (2021). ‘From Antipetismo to Generalized Antipartisanship: The Impact of Rejection of Political Parties on the 2018 Vote for Bolsonaro’, Brazilian Political Science Review, 15:1, 1–28.

- Gomez, Raul, Laura Morales, and Luis Ramiro (2016). ‘Varieties of Radicalism: Examining the Diversity of Radical Left Parties and Voters in Western Europe’, West European Politics, 39:2, 351–79.

- Habersack, Fabian, and Carsten Wegscheider (2021). ‘Populism and Euroscepticism: Two Sides of the Same Coin?’, in Reinhard Heinisch, Christina Holtz-Bacha, and Oscar Mazzoleni (eds.), Political Populism: Handbook on Concepts, Questions and Strategies of Research. Baden-Baden: Nomos, 195–212.

- Haime, Agustina, and Francisco Cantú (2022). ‘Negative Partisanship in Latin America’, Latin American Politics and Society, 64:1, 72–92.

- Harteveld, Eelco (2021). ‘Fragmented Foes: Affective Polarization in the Multiparty Context of the Netherlands’, Electoral Studies, 71, 102332.

- Harteveld, Eelco, Philipp Mendoza, and Matthijs Rooduijn (2022). ‘Affective Polarization and the Populist Radical Right: Creating the Hating?’, Government and Opposition, 57:4, 703–27.

- Hawkins, Kirk A., Ryan E. Carlin, Levente Littvay, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, eds. (2018). The Ideational Approach to Populism: Concept, Theory and Analysis. New York: Routledge.

- Heinisch, Reinhard, and Carsten Wegscheider (2020). ‘Disentangling How Populism and Radical Host Ideologies Shape Citizens’ Conceptions of Democratic Decision-Making’, Politics and Governance, 8:3, 32–44.

- Houle, Christian, and Paul D. Kenny (2018). ‘The Political and Economic Consequences of Populist Rule in Latin America’, Government and Opposition, 53:2, 256–87.

- Huber, Robert A., and Saskia P. Ruth (2017). ‘Mind the Gap! Populism, Participation and Representation in Europe’, Swiss Political Science Review, 23:4, 462–84.

- Huber, Robert A., and Christian Schimpf (2016). ‘A Drunken Guest in Europe? The Influence of Populist Radical Right Parties on Democratic Quality’, Zeitschrift für vergleichende Politikwissenschaft, 10:2, 103–29.

- Huber, Robert A., and Christian Schimpf (2017). ‘On the Distinct Effects of Left-Wing and Right-Wing Populism on Democratic Quality’, Politics and Governance, 5:4, 146–65.

- Huber, Robert A., Michael Jankowski, and Carsten Wegscheider (2023). ‘Explaining Populist Attitudes: The Impact of Policy Discontent and Representation’, Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 64:1, 133–54.

- Huddy, Leonie, Alexa Bankert, and Caitlin Davies (2018). ‘Expressive versus Instrumental Partisanship in Multiparty European Systems’, Political Psychology, 39:S1, 173–99.

- Huddy, Leonie, Lilliana Mason, and Lene Aaroe (2015). ‘Expressive Partisanship: Campaign Involvement, Political Emotions, and Partisan Identity’, American Political Science Review, 109:1, 1–17.

- Ivarsflaten, Elisabeth (2008). ‘What Unites Right-Wing Populists in Western Europe?’, Comparative Political Studies, 41:1, 3–23.

- Iyengar, Shanto, and Masha Krupenkin (2018). ‘The Strengthening of Partisan Affect’, Political Psychology, 39:S1, 201–18.

- Iyengar, Shanto, Yphtach Lelkes, Matthew Levendusky, Neil Malhotra, and Sean J. Westwood (2019). ‘The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States’, Annual Review of Political Science, 22:1, 129–46.

- Jacobs, Kristof, Agnes Akkerman, and Andrej Zaslove (2018). ‘The Voice of Populist People? Referendum Preferences, Practices and Populist Attitudes’, Acta Politica, 53:4, 517–41.

- Juon, Andreas, and Daniel Bochsler (2020). ‘Hurricane or Fresh Breeze? Disentangling the Populist Effect on the Quality of Democracy’, European Political Science Review, 12:3, 391–408.

- Katsambekis, Giorgos, and Alexandros Kiopkiolis, eds. (2019). The Populist Radical Left in Europe. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Klingemann, Hans-Dieter (1999). ‘Mapping Political Support in the 1990s: A Global Analysis’, in Pippa Norris (ed.), Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 31–56.

- König, Pascal D. (2022). ‘Support for a Populist Form of Democratic Politics or Political Discontent? How Conceptions of Democracy Relate to Support for the AfD’, Electoral Studies, 78, 102493.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter (2014). ‘The Populist Challenge’, West European Politics, 37:2, 361–78.

- Laclau, Ernesto (2005). On Populist Reason. London: Verso.

- Linz, Juan J., and Alfred C. Stepan (1996). ‘Toward Consolidated Democracies’, Journal of Democracy, 7:2, 14–33.

- Magalhães, Pedro C. (2014). ‘Government Effectiveness and Support for Democracy’, European Journal of Political Research, 53:1, 77–97.

- Mair, Peter (2002). ‘Populist Democracy vs Party Democracy’, in Yves Mény and Yves Surel (eds.), Democracies and the Populist Challenge. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 81–98.

- Mair, Peter (2013). Ruling the Void: The Hollowing of Western Democracy. London: Verso.

- March, Luke (2011). Radical Left Parties in Europe. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Marcos-Marne, Hugo, Carolina Plaza-Colodro, and Tina Freyburg (2020). ‘Who Votes for New Parties? Economic Voting, Political Ideology and Populist Attitudes’, West European Politics, 43:1, 1–21.

- Marcos-Marne, Hugo, Carolina Plaza-Colodro, and Ciaran O’Flynn (2021). ‘Populism and New Radical-Right Parties: The Case of VOX’, Politics, https://doi.org/10.1177/02633957211019587

- Mayer, Sabrina (2017). ‘How Negative Partisanship Affects Voting Behavior in Europe: Evidence from an Analysis of 17 European Multi-Party Systems with Proportional Voting’, Research & Politics, 4:1, 1–7.

- Medeiros, Mike, and Alain Noël (2014). ‘The Forgotten Side of Partisanship: Negative Party Identification in Four Anglo-American Democracies’, Comparative Political Studies, 47:7, 1022–46.

- Meléndez, Carlos, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (2019). ‘Political Identities: The Missing Link in the Study of Populism’, Party Politics, 25:4, 520–33.

- Meléndez, Carlos, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (2021). ‘Negative Partisanship towards the Populist Radical Right and Democratic Resilience in Western Europe’, Democratization, 28:5, 949–69.

- Meléndez, Carlos (2022). The Post-Partisans. Anti-Partisans, Anti-Establishment Identifiers, and Apartisans in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mohrenberg, Steffen, Robert A. Huber, and Tina Freyburg (2021). ‘Love at First Sight? Populist Attitudes and Support for Direct Democracy’, Party Politics, 27:3, 528–39.

- Mouffe, Chantal (2000). The Democratic Paradox. London: Verso.

- Mudde, Cas (2004). ‘The Populist Zeitgeist’, Government and Opposition, 39:4, 541–63.

- Mudde, Cas (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (2013). ‘Exclusionary vs. Inclusionary Populism: Comparing Contemporary Europe and Latin America’, Government and Opposition, 48:2, 147–74.

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (2017). Populism: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (2018). ‘Studying Populism in Comparative Perspective: Reflections on the Contemporary and Future Research Agenda’, Comparative Political Studies, 51:13, 1667–93.

- Orriols, Lluís, and Sandra León (2020). ‘Looking for Affective Polarisation in Spain: PSOE and Podemos from Conflict to Coalition’, South European Society and Politics, 25:3–4, 351–79.

- Plattner, Marc F. (2010). ‘Populism, Pluralism, and Liberal Democracy’, Journal of Democracy, 21:1, 81–92.

- Ramiro, Luis (2016). ‘Support for Radical Left Parties in Western Europe: Social Background, Ideology and Political Orientations’, European Political Science Review, 8:1, 1–23.

- Reiljan, Andres (2020). ‘“Fear and Loathing across Party Lines” (Also) in Europe: Affective Polarisation in European Party Systems’, European Journal of Political Research, 59:2, 376–96.

- Rennó, Lucio (2020). ‘The Bolsonaro Voter: Issue Positions and Vote Choice in the 2018 Brazilian Presidential Elections’, Latin American Politics and Society, 62:4, 1–23.

- Richardson, Bradley M. (1991). ‘European Party Loyalties Revisited’, American Political Science Review, 85:3, 751–75.

- Ridge, Hannah M. (2022). ‘Enemy Mine: Negative Partisanship and Satisfaction with Democracy’, Political Behavior, 44:3, 1271–95.

- Roberts, Kenneth M. (2022). ‘Populism and Polarization in Comparative Perspective: Constitutive, Spatial and Institutional Dimensions’, Government and Opposition, 57:4, 680–702.

- Rooduijn, Matthijs (2018). ‘What Unites the Voter Bases of Populist Parties? Comparing the Electorates of 15 Populist Parties’, European Political Science Review, 10:3, 351–68.

- Rooduijn, Matthijs, and Brian Burgoon (2018). ‘The Paradox of Well-Being: Do Unfavorable Socioeconomic and Sociocultural Contexts Deepen or Dampen Radical Left and Right Voting among the Less Well-Off’, Comparative Political Studies, 51:13, 1720–53.

- Rooduijn, Matthijs, Brian Burgoon, Erika J. van Elsas, and Herman G. van de Werfhorst (2017). ‘Radical Distinction: Support for Radical Left and Radical Right Parties in Europe’, European Union Politics, 18:4, 536–59.

- Rooduijn, Matthijs, Stijn van Kessel, Caterina Frioi, Andrea Pirro, Sarah L. de Lange, Daphne Halikiopoulou, Paul Lewis, Cas Mudde, and Paul Taggart (2019). The PopuList: An Overview of Populist, Far Right, Far Left and Eurosceptic Parties in Europe, available at www.popu-list.org (accessed 12 December 2021).

- Rooduijn, Matthijs, Wouter van der Brug, and Sarah L. de Lange (2016). ‘Expressing or Fuelling Discontent? The Relationship between Populist Voting and Political Discontent’, Electoral Studies, 43:1, 32–40.

- Rose, Richard, and William Mishler (1998). ‘Negative and Positive Party Identification in Post-Communist Countries’, Electoral Studies, 17:2, 217–34.

- Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal (2012). ‘The Ambivalence of Populism: Threat and Corrective for Democracy’, Democratization, 19:2, 184–208.

- Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal (2014). ‘The Responses of Populism to Dahl’s Democratic Dilemmas’, Political Studies, 62:3, 470–87.

- Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal, and Steven M. Van Hauwaert (2020). ‘The Populist Citizen: Empirical Evidence from Europe and Latin America’, European Political Science Review, 12:1, 1–18.

- Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal, Robert Vehrkamp, and Christopher Wratil (2019). Europe’s Choice: Populist Attitudes and Voting Intentions in the 2019 European Election. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Foundation.

- Rueda, David (2005). ‘Insider–Outsider Politics in Industrialized Democracies: The Challenge to Social Democratic Parties’, American Political Science Review, 99:1, 61–74.

- Ruth, Saskia P. (2018). ‘Populism and the Erosion of Horizontal Accountability in Latin America’, Political Studies, 66:2, 356–75.

- Ruth-Lovell, Saskia P., and Sandra Grahn (2022). ‘Threat or Corrective to Democracy? The Relationship between Populism and Different Models of Democracy’, European Journal of Political Research. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12564

- Samuels, David, and Cesar Zucco (2018). Partisans, Antipartisans, and Nonpartisans. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schedler, Andreas, and Rodolfo Sarsfield (2007). ‘Democrats with Adjectives: Linking Direct and Indirect Measures of Democratic Support’, European Journal of Political Research, 46:5, 637–59.

- Schulze, Heidi, Marlene Mauk, and Jonas Linde (2020). ‘How Populism and Polarization Affect Europe’s Liberal Democracies’, Politics and Governance, 8:3, 1–5.

- Spoon, Jae-Jae, and Kristin Kanthak (2019). ‘He’s Not My Prime Minister! Negative Party Identification and Satisfaction with Democracy’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 29:4, 511–32.

- Steiner, Nils D., and Claudia Landwehr (2018). ‘Populistische Demokratiekonzeptionen und die wahl der AfD: Evidenz aus einer Panelstudie’, Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 59:3, 463–91.

- Tsatsanis, Emmanouil, Eftichia Teperoglou, and Angelos Seriatos (2020). ‘Two-Partyism Reloaded: Polarisation, Negative Partisansip, and the Return of the Left–Right Divide in the Greek Elections of 2019’, South European Society and Politics, 25:3–4, 503–32.

- van der Brug, Wouter, Meindert Fennema, and Jean Tillie (2000). ‘Anti-Immigrant Parties in Europe: Ideological or Protest Vote?’, European Journal of Political Research, 37:1, 77–102.

- Van Hauwaert, Steven M. (2015). ‘An Initial Profile of the Ideologically Volatile Voter in Europe: The Multidimensional Role of Party Attachment and the Conditionality of the Political System’, Electoral Studies, 40, 87–101.

- Van Hauwaert, Steven M., and Stijn van Kessel (2018). ‘Beyond Protest and Discontent: A Cross-National Analysis of the Effect of Populist Attitudes and Issue Positions on Populist Party Support’, European Journal of Political Research, 57:1, 68–92.

- Van Hauwaert, Steven M., Christian H. Schimpf, and Flavio Azevedo (2018). ‘Public Opinion Surveys: Evaluating Existing Measures’, in Kirk A. Hawkins, Ryan E. Carlin, Levente Littvay, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (eds.), The Ideational Approach to Populism: Concept, Theory, and Analysis. London: Routledge, 128–49.

- Van Hauwaert, Steven M., Christian Schimpf, and Flavio Azevedo (2020). ‘The Measurement of Populist Attitudes: Testing Cross-National Scales Using Item Response Theory’, Politics, 40:1, 3–21.

- Van Hauwaert, Steven M., Christian Schimpf, and Régis Dandoy (2019). ‘Populist Demand, Economic Development and Regional Identity across Nine European Countries: Exploring Regional Patterns of Variance’, European Societies, 21:2, 303–25.

- van Kessel, Stijn, Javier Sajuria, and Steven M. Van Hauwaert (2021). ‘Informed, Uninformed or Misinformed? A Cross-National Analysis of Populist Party Supporters across European Democracies’, West European Politics, 44:3, 585–610.

- Voogd, Remko, and Ruth Dassonneville (2020). ‘Are the Supporters of Populist Parties Loyal Voters? Dissatisfaction and Stable Voting for Populist Parties’, Government and Opposition, 55:3, 349–70.

- Wagner, Alexander F., Friedrich Schneider, and Martin Halla (2009). ‘The Quality of Institutions and Satisfaction with Democracy in Western Europe – A Panel Analysis’, European Journal of Political Economy, 25:1, 30–41.

- Wagner, Markus (2021). ‘Affective Polarization in Multiparty Systems’, Electoral Studies, 69, 102199.

- Wagner, Markus, and Thomas M. Meyer (2014). ‘Which Issues Do Parties Emphasise? Salience Strategies and Party Organisation in Multiparty Systems’, West European Politics, 37:5, 1019–45.

- Welzel, Christian (2021). ‘Why the Future is Democratic’, Journal of Democracy, 32:2, 132–44.

- Wuttke, Alexander, Konstantin Gavras, and Harald Schoen (2022). ‘Have Europeans Grown Tired of Democracy? New Evidence from Eighteen Consolidated Democracies, 1981–2018’, British Journal of Political Science, 52:1, 416–28.

- Zanotti, L., and J. Rama (2021). ‘Support for Liberal Democracy and Populist Attitudes: A Pilot Survey for Young Educated Citizens’, Political Studies Review, 19:3, 511–9.

- Zanotti, Lisa, José Rama, and Talita Transcheit (2021). ‘Assessing the Fourth Wave of the Populist Radical Right’: Jair Bolsonaro’s Voters in Comparative Perspective’, Opinião Pública https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/qxyp4

- Zaslove, Andrej, Bram Geurkink, Kristof Jacobs, and Agnes Akkerman (2021). ‘Power to the People? Populism, Democracy, and Political Participation: A Citizen’s Perspective’, West European Politics, 44:4, 727–51.