Abstract

During the past decade, many parliamentary democracies have experienced bargaining delays when forming governments. The previous literature has attributed protracted government formation processes to a high degree of preference uncertainty among the political parties and a high level of bargaining complexity. The article draws on such theories, but also adds a third theoretical mechanism, commitment problems, and highlights two explanatory variables that have not received much attention so far. The first is pre-electoral coalitions, which are declarations by parties stating that they intend to collaborate with each other after the election. The second is familiarity, which is the mutual trust between parties that comes from having worked together in the past. By combining a large-N study of government formation processes in 17 West European parliamentary democracies (1945–2019) with an in-depth case study of the prolonged Swedish government formation process in 2018–2019, it is shown that pre-electoral coalitions that fail to win a majority can sometimes delay, not speed up, government formation. In addition, a lack of familiarity may sometimes lead to a breakdown of negotiations and drawn-out government formation processes.

It is taking longer and longer to form governments in parliamentary democracies with multi-party systems. Between the early 1970s and the middle of the 1990s, government formation in the Western European democracies took on average about a month. Between the late 1990s and the late 2010s, it took two (Bergman et al. Citation2021a, 691–692).

Extended periods of bargaining before a new government is formed can come with several negative effects, which are mainly related to economic actors’ uncertainty about what policies the future government will implement. This uncertainty can lead to delayed investments and volatility in the currency and stock markets (Bernhard and Leblang Citation2006). An extended period of bargaining usually also means that the country is governed by a caretaker government, which may mean that crisis events are not handled efficiently. Hence, it is important to understand why countries sometimes go through drawn-out government formation processes. We thus ask, why are there sometimes bargaining delays when parliamentary governments form?

The main argument of this article is concerned with the joint effects of long-term changes in party systems and short- and medium-term changes in party strategies. Across Europe, increasing party system fragmentation and the rise of extreme parties have complicated the problems parties need to solve when forming governments, which has contributed to making government-formation processes more long-lasting. These effects have been documented in earlier studies—and our comparative data tell a similar story. But we argue that bargaining duration also depends on the strategic choices parties make. Here we emphasise two factors. The first is pre-electoral coalitions—declarations by parties stating that they intend to collaborate with each other after the election. The second is familiarity—the mutual trust between parties that comes from having worked together in the past. Conversely, a lack of familiarity may negatively influence the ability of parties to come to an agreement.

As we explain in the article, it is difficult to study the effects of these party-strategic factors with the help of quantitative methods. We therefore combine a comparative large-N analysis of government formation processes in 17 countries in Western Europe since the Second World War with case study evidence from the drawn-out government formation process in Sweden in 2018–2019. Our general statistical model can explain some of the sharp increase in bargaining duration in Sweden in 2018–2019, but not all of it—the case-study evidence, which emphasises the role of pre-electoral coalitions and familiarity, explains why it took an exceptionally long time to form a government in the Swedish case.Footnote1

Our article makes both theoretical and empirical contributions to the literature. It presents new theoretical ideas about the consequences of pre-electoral commitments and familiarity—two explanatory factors that have not been stressed much in the previous literature. It also presents a comparative analysis of government formation in Western Europe in the post-war period that is based on new data and generates new findings. Finally, it presents unique case-study evidence on Sweden’s most drawn-out government formation process ever, explaining why pre-electoral coalitions that fail to win a majority can sometimes delay, not speed up, government formation, and why bargaining among parties that have not collaborated previously sometimes breaks down.

Explaining government bargaining duration

The time it takes to form a government after elections varies a lot between and within countries. In Belgium and the Netherlands, in the post-war era, an average government takes about three months to form, and in Austria, it takes about two months. However, in contrast, a government in Greece, France or the United Kingdom is normally formed within a week. As previously mentioned, many of the most protracted government formations occurred in the last two decades. Indeed, nearly all of the most drawn-out government formation processes recorded in the data occurred in Western Europe in the 2000s and 2010s: two in Belgium in 2010–2011, and 2014 that took 541 days and 139 days, respectively. Two in the Netherlands in 2017 and 2021–2022, which took 225 and 299 days. As well as, one in Germany in 2017–2018 and one in Sweden 2018–19, which took 141 and 134 days.

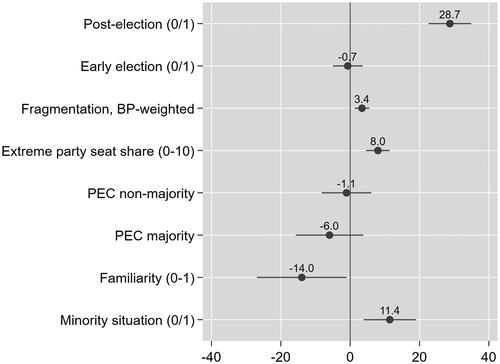

illustrates that these protracted government formations are rare and that less than 5 per cent of all governments (since 1945) take more than three months to form. And as we discuss below, it is the lengthiest formations that are hardest to explain using standard empirical models.Footnote2

Figure 1. Government formation duration in Western Europe, 1945–2019.

Note: The government formations in Belgium 2007 (194 days) and 2010/11 (541 days), as well as in the Netherlands 1977 (208 days) and 2017 (225 days), are not shown in the figure.

In the literature, there are three general theoretical mechanisms that help to explain bargaining failures and government formation delays: preference uncertainty, commitment problems, and bargaining complexity.

If all parties have complete information about what other parties want and what their bargaining space is, government formation should be swift, since a formateur should be able to present a proposal that is accepted immediately by all. But we know government negotiations often take time. One plausible explanation is that the assumption of complete information must be rejected: bargaining occurs under preference uncertainty. Diermeier and Van Roozendaal (Citation1998) argue that political actors are often uncertain about where other actors stand on different issues, how they view different government alternatives, and what general goals they have (see also Ecker and Meyer Citation2020). This uncertainty contributes to bargaining delays since it takes time for parties to learn about the preferences of others: they need the first bargaining rounds to reduce uncertainty.

Even if all parties have complete information about the preferences of others, they will only enter into an agreement if they’re confident that whatever deal is struck today will be implemented tomorrow. If they aren’t, bargaining is complicated by commitment problems. This is a second general mechanism that may lead to bargaining failure or delays. As noted by Fearon (Citation1995) in the context of war, uncertainty and commitment problems are distinct mechanisms since commitment problems may cause a breakdown in bargaining even if all parties have complete information. Commitment problems have so far not received a lot of attention in the literature on government bargaining, but they’re ubiquitous in the general bargaining literature.

Finally, there may be constraints outside the immediate bargaining environment that make it more difficult for the political parties to reach an agreement. Examples include the need for intra-party signalling, expectations about the level of detail required in coalition agreements, and the sheer number of alternative allocations of cabinet posts. In short, the complexity of the political environment is a third mechanism that may increase the likelihood of failures and delays—especially when combined with preference uncertainty or commitment problems (the first two mechanisms).

Our empirical analysis distinguishes between three types of explanatory factors: the electoral context, the party system, and the strategic choices of the political parties. Although there is no direct mapping, the three general theoretical mechanisms we have just discussed (preference uncertainty, commitment problems, and bargaining complexity) can account for the effects of each of these factors.

Starting with the electoral context, numerous studies have shown that government negotiations that take place immediately after an election take longer than negotiations that take place between elections (Diermeier and Van Roozendaal Citation1998; Golder Citation2010; De Winter and Dumont Citation2008; Ecker and Meyer Citation2015). This result is best explained by preference uncertainty. Uncertainty is greater after an election than at other times (Curini and Pinto Citation2016). Prior to elections, the political parties often revise their platforms, and there are sometimes changes in party organisations and party caucuses as new candidates are elected to political assemblies (Falcó-Gimeno and Indridason Citation2013).

Turning to party-system factors, many scholars have argued that it is more difficult to negotiate and reach an agreement if there are many alternative governments and if there are major conflicts among the political parties. For example, De Winter and Dumont (Citation2008) show in their comprehensive analysis of governments formed in Western Europe during the post-war period that ideological differences among the parties are decisive for how long it takes to form a government. In a similar study, Golder (Citation2010) shows that it takes longer to form governments when the number of parties in parliament is large and when ideological polarisation is high (a finding replicated in Ecker and Meyer Citation2020; Blockmans et al. Citation2016). Bargaining complexity is the general mechanism that best explains these findings. Having more parties, with greater ideological distances between them, complicates the problems that parties need to solve to form a government.

Another factor that may increase complexity is the presence of extremist parties. As originally argued by Sartori (Citation1976), and later stressed by Warwick (Citation1992), the presence of large extremist parties may both decrease and increase bargaining complexity. On one hand, these parties are not seen as suitable coalition partners, so they restrict the number of possible government alternatives, which reduces the complexity of the negotiations (De Winter and Dumont Citation2008; Falcó-Gimeno and Indridason 2013). On the other hand, the presence of parties that are considered unfit for office may force political parties that are far apart ideologically to collaborate with each other, which increases the complexity of negotiations. This ambiguity is the likely explanation for the mixed results of previous empirical analyses of the impact of extreme-party size on bargaining duration (Diermeier and Van Roozendaal Citation1998; De Winter and Dumont Citation2008).

It is not always straightforward to distinguish between uncertainty and complexity. For example, Martin and Vanberg (Citation2003) argue that both party system fragmentation and ideological polarisation can be interpreted as measures of uncertainty, not complexity, since uncertainty is lower if few actors are involved in bargaining and if those actors are ideologically similar.

We now turn to the third category of explanatory factors: the strategic behaviour of the political parties. One explanatory factor that has only been considered in passing in previous research is the presence of pre-electoral coalitions.Footnote3 A pre-electoral coalition exists when some parties have stated publicly that they plan to cooperate in government after the election. We believe that pre-electoral coalitions deserve more theoretical and empirical attention in studies of delays in government formation. Several scholars have stressed the importance of pre-electoral coalitions in general (Golder Citation2006), and it is known that parties are more likely to rule together after an election if they entered into a pre-electoral coalition before it (Martin and Stevenson Citation2001; Debus Citation2009). Pre-electoral coalitions can function as a ‘signalling tool’ to win votes (Golder Citation2006), and to influence which government will form (Bandyopadhyay et al. Citation2011), but also as a coordination mechanism in the anticipation of complex coalition bargaining (Carroll and Cox Citation2007), which suggests they might have an effect on bargaining delays.

However, it is not clear which effect. On the one hand, pre-electoral coalitions might speed up government formation. If the political parties spend a lot of time before the election bargaining with each other over policy, they should understand each other’s policy preferences better and find it easier to overcome commitment problems. When parties publicly commit to the voters that they will be joining a particular coalition after the election, this also ties their hands, which reduces complexity since parties have fewer options. On the other hand, there may be circumstances in which pre-electoral commitments prolong the government formation process. We are thinking in particular of situations in which the election outcome is unfavourable to the parties that have entered into a pre-electoral coalition.

One of the essential conditions that must be met for a pre-electoral coalition to facilitate government formation is that the coalition achieves the electoral majority it desires (Blockmans et al. Citation2016, 135). This might mean an absolute majority, in a system that requires majority governments, but it might also mean a relative majority in a system like the Swedish, with a negative investiture vote (Bergman Citation1995). The presence of a weak pre-electoral coalition that lacks even a relative majority may complicate negotiations with other parties after the election. In such cases, parties in pre-electoral coalitions need to assess the potential electoral costs of going their separate ways. This is a different sort of uncertainty than the one normally theorised in the literature on government formation. The parties in a dissolving pre-electoral coalition are uncertain about their own preferences (De Winter and Dumont Citation2008, 135). This uncertainty can lead to a process of intra-party bargaining that itself takes time (Luebbert Citation1986, 52). But the effect of a pre-electoral coalition not gaining a majority will most likely vary with context.

On the basis of these ideas about the ambiguous effects of pre-electoral coalitions, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 Government formation takes less time when there is an electorally successful pre-electoral alliance (i.e. when the parties in that alliance achieve an electoral majority); otherwise, the presence of a pre-electoral alliance has no clear effect.

Drawing on the idea that parties are more knowledgeable about each other’s preferences and more likely to trust each other if they have experience of cooperating with each other—reducing preference uncertainty and helping parties solve commitment problems—we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 Government formation takes less time when there is more familiarity among the parties in the political system.

Design, data, and methods

This article has a mixed-methods design: it combines a statistical analysis of large-N data on government formation in a sample of 17 West European democracies for the period 1945–2019 with a case study of Sweden in 2018–2019.

As we discussed in the introduction, our statistical analysis gives us robust estimates of the effects of the electoral context and of structural party-system factors, but as we demonstrate in the next section, the effects of factors related to the strategic behaviour of political parties—including pre-electoral coalitions and familiarity—are very difficult to capture with quantitative methods, since the strategic context varies so much among countries and over time. We instead believe the accumulation of knowledge in this area has to rely on case studies of individual countries. That is why we combine our comparative large-N analyses of government formation processes in 17 countries in Western Europe since the Second World War with case study evidence from the drawn-out government formation process in Sweden in 2018–2019. This is a case that is not well-explained by the statistical model and that offers unique opportunities to study the role of pre-electoral coalitions and familiarity.

When we go from the quantitative analysis to the case study, we follow the approach of Coppedge (Citation2005) by using the statistical results to explain as much as possible of the outcome of the Swedish government formation process in 2018–2019; we then use the qualitative evidence from the case study to examine the specifics of the Swedish case.

The qualitative material for the case study most importantly consists of 37 face-to-face interviews that were conducted in the summer and fall of 2019 with the actors who were most directly involved in the government formation process: the party leaders, the party secretaries, the Speaker of the Riksdag, and a few other party functionaries and others who played an important role in the different bargaining rounds. To allow the interviewees to speak as freely as possible, they were guaranteed 10 years of anonymity.

Our quantitative data come from the Party Government in Europe Database (PAGED), which provides information on parties, governments, party systems, and political institutions in representative democracies in Europe from 1945 onward (Hellström et al. Citation2021; Bergman et al. Citation2021b). lists all variables used in the empirical analyses.

Table 1. List of variables (averaged by the sample for model 2 in table 2).

There are many ways to decide when one government ends and another begins. Following the existing literature on government formation (Müller and Strøm Citation2000, 15), we define bargaining duration as the time that passed between the end of the previous cabinet and the start of the next government. To be precise, for post-election governments the bargaining period is defined as the passage of time between the parliamentary election and the day a new government is appointed. For inter-election governments—that is, replacement cabinets where one or more parties leave or join a government—the termination of the previous government, and therefore the beginning of the bargaining period, is defined as any change in the government’s party composition. In contrast to previous studies of bargaining duration, we concentrate on pure bargaining situations. That is, we exclude all cases where no bargaining over office took place. Consequently, we exclude ‘new’ cabinets that were only due to a change of prime minister, and we exclude incumbent governments that never resigned or were dismissed after elections (so-called continuation cabinets). In addition, we exclude replacement cabinets that simply remained in office without resigning and without initiating bargaining with new potential partners. Since we concentrate on instances where bargaining over office between the different parties actually happened, we are confident that our empirical models are more in line with the theories that have been developed to explain bargaining duration, since those theories are concerned with the behaviour of and interactions between political parties during actual bargaining or in the anticipation of actual bargaining.

Turning to our main explanatory variables, we use two categorical indicator variables for pre-electoral coalitions (PECs): one takes the value 1 when there is a PEC but it doesn’t get a parliamentary majority (otherwise it takes the value 0), the other takes the value 1 when a PEC receives a parliamentary majority (otherwise 0). In the PAGED data, a PEC is defined as an official commitment of two or more parties (before the election) to form a joint government after the election. However, only mutual agreements are considered and one party issuing a preference for another party as a future coalition partner but receiving no commitment in return does not count as a PEC. This means that we have a more restrictive, but at the same time more reliable, measurement of PECs than previous studies (e.g. Golder Citation2006).

In order to test our hypothesis that government formation processes are shorter when there is more ‘familiarity’ among the parties in the political system, we create an index of familiarity. In order to avoid biasing the results in favour of our hypothesis, our index mimics the one used in one of the most influential studies of familiarity, that is, Martin and Stevenson (Citation2010). Following their approach, we take all party pairs into account at any given time and set familiarity to 1 for two parties M and K that take part in the same government coalition, 0 otherwise. Like Martin and Stevenson (Citation2010), we also assume that a party is ‘completely familiar with itself’, so familiarity is 1 also when M = K. We then weigh each pair by their portfolio share.Footnote4 Finally, we take the time-weighted stock of these weighted values with time counted in months and the depreciation rate set to 5 per cent.Footnote5 The resulting values are then averaged across all party pairs to yield an aggregate measure of familiarity among all parties at any given time point. We lag this measure one month to ensure that familiarity with the government that results from a given formation attempt is not counted.Footnote6

When it comes to party-system variables, we investigate the effect of the legislative size of extreme parties on bargaining duration by measuring the share of parliamentary seats that were won by radical-left parties and (populist) radical-right parties.Footnote7 The fragmentation of the party system is usually measured using an index of the effective number of parties in parliament (Diermeier and Van Roozendaal Citation1998; Ecker and Meyer Citation2020; Golder Citation2010; Ecker and Meyer Citation2015; Martin and Vanberg Citation2003), since negotiations become more difficult if there are many alternative coalitions (Diermeier and Stevenson Citation1999) or many bargaining parties (Martin and Vanberg Citation2003). In this study, we opt for an alternative measurement of fragmentation that we believe is superior to the standard effective-number-of-parties measure originally proposed by Laakso and Taagepera (Citation1979). As shown by Caulier and Dumont (Citation2005), the standard effective-number-of-parties index produces misleading results when there is a single-party majority winner, since the index still indicates that more than one party is relevant for government formation. By using bargaining weights (Banzhaf’s normalised index) rather than seat shares, it is possible to get a more precise measurement of fragmentation for the specific purpose of analyses of government formation.Footnote8

Finally, our empirical models include a set of controls for the electoral context that have been found to be important in previous research. The first is an indicator variable for post-election periods since it is well-known that cabinet formation takes longer after elections than between elections. Many scholars have even used post-election period dummies as a proxy for bargaining uncertainty (Diermeier and Van Roozendaal Citation1998; Ecker and Meyer Citation2020, Citation2015; Martin and Vanberg Citation2003). We also include a second indicator variable for bargaining processes that occur immediately after early parliamentary elections, since those bargaining situations are in a sense endogenous to the ensuing government formation process (Ecker and Meyer Citation2015). The final control variable is an indicator variable for ‘minority situations’, that is, when there is no single-party-majority winner (Golder Citation2010; Ecker and Meyer Citation2015; Martin and Vanberg Citation2003).

In previous studies, bargaining delays have mainly been studied with Cox proportional-hazards models. An obvious advantage of the Cox proportional hazards model is that it allows for censoring (cases where the exact survival time is unknown) (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones Citation2004). In our study, however, bargaining duration is known in all cases, so there is no need to consider censoring. We therefore model bargaining duration using negative binomial regression models, which generate comparatively easy-to-interpret results. Negative binomial regression is a method that is suitable for over-dispersed count-outcome variables. It relies on a standard linear function of the explanatory variables to predict the logarithmic value of the outcome variable (in our case the length of the government formation process measured in days). Negative binomial regression differs from the standard linear regression model since the dependent variable is an observed count that is assumed to follow the negative binomial distribution.Footnote9 The main advantage of negative binomial regression over the Cox proportional hazards model is that the latter only estimates deviations from a baseline hazard rate; it therefore cannot be used to predict the survival time directly. Since we are interested in evaluating the empirical model’s performance when predicting the outcome of the Swedish government formation process in 2018–2019, this is an important consideration for us.Footnote10

Statistical findings

presents the results of four negative binomial regression models with bargaining duration (in days) as the outcome variable. All models include country-fixed effects to control for unmeasured time-constant country-specific characteristics that may affect bargaining duration.Footnote11 Model 1 and 2 provides estimates for a sub-sample that only includes pure bargaining situations. As we explained earlier, we exclude ‘new’ cabinets that only represent a change of prime ministers (if the party composition is unaltered) as well as ‘continuation cabinets’ (when incumbent cabinets remain in office without any bargaining taking place). In Models 1 and 2, we also exclude governments formed when there’s a single-party majority in the parliament.Footnote12 For reference, we also present results for all instances of government formation, regardless of whether inter-party bargaining took place or not, in Models 3 and 4 (this is the standard sample that is examined in previous studies). Models 1 and 3 measure whether the incumbent government receives a parliamentary majority after the election. This measure captures an immediate ‘familiarity’ among parties, and that parties that worked together in the outgoing government received a parliamentary majority. In such situations, bargaining over the government should, in most cases, be uncomplicated. Our main measurement of ‘familiarity’ is, however, as described above, more broadly defined, and models 2 and 4 show the results when using this measurement.

Table 2. Bargaining duration in Western Europe, 1945–2019 (only pure bargaining situations).

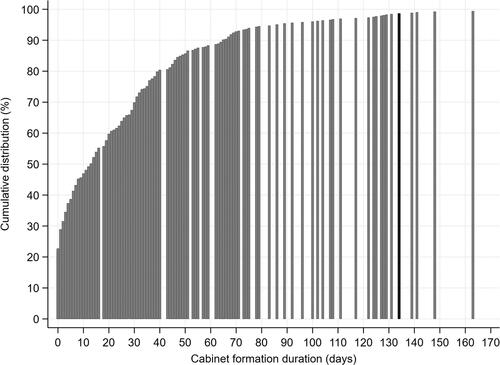

To help evaluate the substantive effects of the explanatory variables on bargaining duration, presents the estimated number of extra days of bargaining that is associated with a one-unit increase in each predictor in the model.Footnote13

Starting with the electoral context, the models show that, as expected, post-election bargaining situations are associated with bargaining delays (about one month on average compared with between-election government formation processes). Also as expected, government formation takes longer when there is no single-party majority winner after the election. But early elections do not seem to make any difference: the coefficient is very close to zero.

Turning to the party-system variables, as many previous studies have found, there is a considerable bargaining delay when there is more party-system fragmentation, and, therefore, a greater number of possible coalitions available. As seen in , in the most fragmented party systems, there is almost one month of additional delay in the government formation process compared with party systems with a single-party majority winner. The seat share of extreme parties also matters. On average, a 10 per centage-point increase in the seat share of extreme parties (i.e. a one-unit increase of the variable) is associated with a delay in government formation of about 8 days. Where previous research has found no discernible effects (Martin and Vanberg Citation2003), or mixed effects (De Winter and Dumont Citation2008), we find considerable support for the idea that the extreme-party share is associated with longer government formation processes.

We now get to the variables we will further explore in the case study of Sweden: pre-electoral coalitions (Hypothesis 1) and familiarity (Hypothesis 2). Here the findings are less conclusive. Starting with Hypothesis 1, the estimated parameter for pre-electoral coalitions with majority support is in the right direction, indicating that these coalitions are associated with shorter bargaining duration, but the effect is not statistically significant. Meanwhile, at least on average, pre-electoral coalitions that fail to win a parliamentary majority do not seem to have any effect on bargaining duration: the coefficient is close to zero.

To learn more about what’s behind these results, we have examined the pre-electoral coalitions in detail. There is much heterogeneity among the PECs that we included in our statistical analyses. Most of the examples of pre-electoral coalitions with majority support are from France and Italy, and in both cases, the main motive for forming pre-electoral coalitions has been to benefit from the implicit (France) and explicit (Italy) majority bonus in the electoral rules. In Italy, government formation has often taken quite a lot of time even if there have been strong pre-electoral coalitions, since the parties only agreed to run together, not on how to govern together. As for pre-electoral coalitions without majority support, we note that the results are influenced by the presence of many small pre-electoral coalitions among parties that have had little influence over cabinet bargaining.

Because of this heterogeneity in the purpose and size of pre-electoral coalitions, we believe that case studies are likely to tell us more about the effects of these party-strategic choices. The same goes for familiarity (Hypothesis 2). Incumbent governments that get a parliamentary majority appear not to shorten governments formation processes on average (model 1 and 3); however, there is some support in the cross-country comparative data for the idea that greater familiarity speeds up government formation (models 2 and 4), but not by much: the estimated difference between situations where there is no familiarity and situations where there is maximum familiarity among the parties—as measured by our index—is approximately 14 days. Also, as we show in the online appendix, the familiarity measurement is not robust to alternative ways of measuring familiarity (such as using a smaller depreciation rate or not counting a party as perfectly familiar with itself). Again, we have more confidence in the qualitative evidence that case studies can offer.

Government formation in Sweden, 2018–2019

In this section, we examine the uniquely long government formation process in Sweden in 2018–2019, which took 134 days. The previous record, 40 days, was the protracted government formation after the election of 1920, almost a century earlier.

Predicting bargaining duration

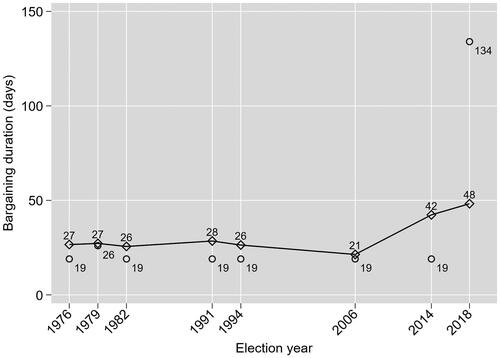

The empirical model presented in can be used to predict the duration of the Swedish government formation process after the 2018 election. describes the predicted bargaining duration for post-election cabinets in Sweden between 1976 and 2018, taking into account all the information about the observable factors that are included in our empirical models.Footnote14 In the figure, we also show how long it actually took to form a government in these years.

Our statistical model predicts a bargaining duration of 48 days after the 2018 election. This is the highest predicted value for any Swedish post-election government formation process. The main reasons for the increase in the predicted duration are party-system fragmentation and the growth of Sweden’s radical-right populist party, the Sweden Democrats. There is also a lower level of familiarity in the Swedish party system than a decade ago. In other words, if we look at the factors that proved to be important in our comparative analysis, it is unsurprising that it took longer than usual to form a government after the 2018 election.

But our model does not predict that it would take as much as 134 days to form a new government. In fact, our empirical model fails to predict the most protracted government formations in Europe and grossly underestimates the length of these (see in the online appendix). Since our statistical model can only partially explain the protracted government formation process in 2018–2019, we now turn to qualitative evidence of the party-strategic factors that can explain the difference between the predicted bargaining duration of 48 days and the actual bargaining duration of 134 days.

The government formation process

Sweden’s rules on government formation, laid down in the Instrument of Government, are meant to facilitate a speedy process.Footnote15 But it took more than four months to form a government after the 2018 election, which was held on September 9. Two weeks after the election, on September 24, the Riksdag was summoned, and the day after, Prime Minister Stefan Löfven, who led a coalition between the Social Democrats and the Greens, failed to pass the compulsory vote of no confidence. After failed formateur attempts by the Moderate Party (Conservatives) and the Social Democrats, the Speaker nominated Ulf Kristersson of the Moderates as prime minister, but he also failed to pass an investiture vote on November 14.

After a failed informateur attempt by Annie Löof of the Centre Party, a first bargaining round proper followed in early December, which included the caretaker government parties, as well as the Centre Party and the Liberals. These negotiations broke down when a prospective deal was turned down by the Centre Party. The Speaker nevertheless nominated the Social Democratic party leader Löfven to form a new government, but on December 14 he too failed to pass the investiture vote. Following a brief Christmas recess, a second bargaining attempt between the same four parties resulted in a deal—the ‘January Agreement’. On the basis of this deal, the Centre Party and the Liberals could support a new coalition government between the Social Democrats and the Greens, but without themselves being part of the coalition. Löfven was again nominated as prime minister and passed the investiture vote on January 18. The new minority coalition—with the same party composition as the old one—was formally installed on January 21.

Our analyses suggest that two critical junctures in the formation process are key to explaining the long duration. These two junctures intersect with the two failed investiture votes in November and December.

Why no bargaining before December?

When Kristersson of the Moderate party was proposed as prime minister in November, he was only supported by his own party, the Christian Democrats, and the right-wing-radical Sweden Democrats. With all other parties voting against him—including the Centre Party and the Liberals, with whom the Moderates and the Christian Democrats had cooperated in government before—he couldn’t form a government. But if the Centre Party and the Liberals did not want the Moderate party leader to form a government, why did they not bargain over an alternative government earlier on? The four centre-right parties together received 133 seats in the Riksdag, one fewer than the 134 seats controlled by the so-called ‘red-green’ bloc (the Social Democrats, the Greens and the Left Party). The Centre Party and the Liberals were unwilling to support a centre-right government that would be dependent on the votes of the Sweden Democrats to form, pass the budget, and pass legislation. But this was known to them already a few days after the election in September. So why then didn’t they begin to bargain with the Social Democrats right away?

The answer is the remarkably close pre-electoral coalition that was formed almost fifteen years before the 2018 election between the Centre Party, the Liberals, the Moderates, and the Christian Democrats: ‘Alliance for Sweden’. This had been the most successful collaboration ever between political parties in Sweden’s political history. The Alliance was formed in 2004, won the election in 2006, and formed the first majority government in Sweden since 1981. It remained in government after the election of 2010, despite losing its majority when the Sweden Democrats entered the Riksdag. In three elections in a row, the Alliance campaigned on a common platform. In the legislature, the four Alliance parties formed such a coherent bloc between 2006 and 2014 that it functioned like one single party (Lindvall et al. Citation2020, Chapter 4). In 2018, with the exception of the leader of the Christian Democrats, the party leaders of the centre-right parties had worked together in the same cabinet; they also knew each other well. They were thus very much held together by ‘familiarity’ in Franklin and Mackie’s sense (1983), but also by vote-seeking considerations: the Alliance was a strong brand in the Swedish electoral market and many voters identified themselves with the Alliance, not the individual parties (Hagevi Citation2015).

A strong pre-electoral coalition such as the Alliance could reasonably have been expected to facilitate government formation after the 2018 election. The reason it didn’t was that the Alliance didn’t achieve the relative majority it sought. In this situation, the Alliance parties didn’t know how to proceed. The lack of electoral success led to uncertainty among the Alliance parties over their own preferences, which caused an internal bargaining process within each party.

This process was swift for the Moderates and the Christian Democrats, who had already in October agreed to form a (minority) coalition government despite its presumed reliance on the support of the Sweden Democrats. In the Centre and Liberal Parties, by contrast, the process was arduous and ridden by serious internal dissension. In our interviews—and also in statistical analyses of the views of individual members of parliament within the two parties—we have been able to distinguish two ways of viewing this conflict. First, one may view it in voter-strategic terms. Both parties had made strong pre-electoral commitments not to form a government that would be dependent on the support of the Sweden Democrats. They feared they would lose votes if they reneged on this promise and supported a government that was dependent on the Sweden Democrats in the Riksdag. Second, it is possible to view the conflict in policy terms. The centre-right parliamentarians that supported the Moderate Kristersson as prime minister, granting the Sweden Democrats influence, were also significantly closer to the Sweden Democrats in the GAL-TAN dimension (Teorell et al. Citation2020; Lindvall and Teorell Citation2022; Lindvall et al. Citation2017, 119–121).

Regardless of the underlying rationale for the conflict, it was a difficult one for both parties, so it took time to resolve. After the Centre leader Annie Löof’s failed informateur attempt in mid-November, the internal decision-making process intensified. In joint meetings of the party board and the parliamentary caucus, a majority reluctantly approved of negotiations with the Social Democrats and the Greens, which started on December 4. But in both parties, there was disagreement at the very top. In the Liberal party, about a third of the board members and members or parliament voting against working with the Social Democrats.

In sum, the answer to why there was no bargaining before December lies in the strong pre-electoral coalition, the Alliance. Schematically, supporting Hypothesis 1, the argument can be summarised as follows: pre-electoral coalition without majority → preference uncertainty → intra-party bargaining → bargaining delay.

Why did the bargaining attempt in December fail?

If the negotiations that started in December had led to an agreement accepted by the four parties, the investiture vote on the Social Democrat party leader Löfven as prime minister on December 14 would have led to the formation of a new government at that time. This would have shortened the government formation process by around 40 days.

Since the Centre Party was the one that rejected the deal reached in the early hours of December 9, after five days of intense bargaining, we will here mostly concentrate on their reasoning. We can also gain some analytical traction from the fact that we have two bargaining rounds of about equal duration (ca 5 days), one occurring in December and the other in January, involving the same parties and almost the same individuals, both times executed in complete secrecy (no journalist was even aware the bargaining occurred)—but where the first attempt failed, the second succeeded.

The reason for failure, in our view, was a lack of familiarity: these four parties had never before sat around the same table to negotiate over government formation. The causal mechanisms explaining why this led to bargaining delays are in perfect alignment with the game-theoretical bargaining literature on preference uncertainty and commitment problems. All people we interviewed who took part in the talks testify to the ‘bad atmosphere’ in the room. The tension was most deeply felt between the Centre Party and the Social Democrats. When bargaining commenced, Löfven was not even present. This is due to a tradition in the Social Democratic party stipulating that the party leader only needs to get involved when the final bits and pieces are to be resolved. But when the party leader of the Left Party at the same time appeared in the Swedish media to talk about the ‘red lines’ that could not be crossed for him to accept a Social Democratic government, the absence of the Social Democrat leader from the bargaining table made the Centre Party and the Liberals suspect that they were being double-crossed.

But the Social Democrats also doubted the sincerity of the Centre Party. Since the Centre Party leadership was so sceptical of the Social Democrats, they started the negotiation by stating their demands publicly, to the media, and they did so in a tone that suggested they were not open to discussion but instead made take-it-or-leave-it proposals. When the Social Democrats tried to respond in a private note to the Centre Party leader, she again went public and called the response ‘a bid so low as to be humiliating’ (a skambud in Swedish). This made the Social Democrats think that the Centre Party only joined the negotiations to signal to their activists and voters that they had tried but failed to reach an agreement.

The bad start had further repercussions. The perception of the Social Democrats was that the Centre Party was only there to extract information about how far-reaching concessions the Social Democrats were willing to make. When the negotiations were drawing to a close, the Centre Party leader tried to signal that the deal was not going to be acceptable to her party, but the Social Democrats interpreted that as a bluff. When they realised that the party board and parliamentary caucus of the Centre Party had actually turned down the proposal, they were surprised.

This is preference uncertainty in action. According to our interviews, all actors involved however agree that the situation was very different when the parties bargained again in January. On certain issues that were critical for the Centre Party, bilateral deals with the Social Democrats had been struck right before the Christmas recess in talks that only included senior officials and functionaries, which helped to reduce preference uncertainty on both sides.

But on top of the preference uncertainty, there were also commitment problems at play during the failed bargaining round in December. Even when a part of the deal was acceptable to a party, that party didn’t trust the other side not to renege on the deal. Since the Centre Party and the Liberals were not going to be part of the government, but needed the deal to promote their preferred policies, these commitment problems were most relevant for them. Although the deal that was rejected in December was never made public, we were able to get hold of a copy, and when comparing it with the ‘January agreement’ that all parties later accepted, we note that the differences in terms of actual policy agreements are small—especially when seen from the perspective of the Centre Party. What is strikingly different, however, is the extent to which the agreed-upon deals in the January version now had a detailed timetable. The initiation and execution of the different reforms and pieces of legislation were explicitly dated, which is likely to have increased the confidence of the Centre Party that the policies the parties agreed on would be implemented.

This is very clearly stated in the explanation the Centre Party leader Löof offered the public on December 10 about why the Centre Party had not accepted the deal. The Social Democrats, she said, hadn’t been precise enough about the labour market and housing-market reforms. ‘The wording that exists may look beautiful, but it is vague and imprecise. …They try to bury quite a lot in government commissions and postpone specifying timetables to the future’. Interestingly, she then continued by tying back to the first explanation offered above, the pre-electoral coalition: ‘Me and the Centre Party, we are used to the constructive culture of cooperation that we have had and have within the Alliance …But in these sharp negotiations with the Social Democrats, it has become clear that the Social Democrats are used to a completely different kind of cooperation, where they are in the driver’s seat and other parties just follow’.

We suggest that the case study evidence presented here supports Hypothesis 2, stressing that bargaining delays can be the result of lack of familiarity. Schematically, the explanation as to why the first bargaining round failed can be summarised as follows: lack of familiarity → preference uncertainty + commitment problems → bargaining failure.

Conclusions

In this article, we have combined quantitative evidence on government formation processes in Western Europe in the post-war period with qualitative evidence on the exceptionally drawn-out government formation process in Sweden in 2018–2019. Based on this quantitative and qualitative evidence, our article offers several new insights into the causes of delays in government formation—an increasingly common phenomenon in contemporary Europe.

Although we do not find any robust effect of pre-electoral coalitions in the cross-country comparative data, the evidence from Sweden strongly suggests that whereas a pre-electoral coalition that wins a majority may well reduce bargaining duration in some contexts, a pre-electoral coalition that fails to win a majority can have the opposite effect. Meanwhile, we find that familiarity—when parties have prior experiences of governing together—reduces bargaining duration, whereas a lack of familiarity prolongs government formation, but again, that finding is not particularly robust in the large-N analysis but most importantly supported in the case-study evidence from Sweden.

One of the limitations of this study is that we only have evidence from one particular case that suggests that pre-electoral commitments can, in some situations, seriously hinder the formation of a government, and thereby prolong the bargaining process. Ideally, we should have additional evidence in favour of this claim, and we therefore suggest that future research should further analyse under which conditions pre-electoral commitments cause bargaining delays, both in large-N and small-N studies.

What is clear for Sweden is that if we compare the government formation processes after the three elections before the case study in focus, that is, after the 2006, the 2010, and the 2014 elections, they were much quicker affairs, with a government forming within a few weeks. During the campaigns of these elections, pre-electoral coalitions had formed in all cases on the non-socialist (Alliance) side, and in two of the cases on the socialist side (Hellström and Lindahl Citation2021). In all three cases, the parties forming these pre-electoral coalitions did not have to break their electoral promises about which government to form but could form a government within the blocs. The main difference between these three cases and the 2018–2019 case was that the right-wing populist Sweden Democrats had grown significantly in size and that there was tension within one of the blocs (the Alliance) about whether the Sweden Democrats should be seen as a ‘pariah’ or not. Hence, it became necessary for some parties to break one of the pre-electoral commitments they had made, either about cooperating with the parties in their announced blocs, or about (not) cooperating with the Sweden Democrats.

Such circumstances may clearly occur in other countries than Sweden, for example since right-wing populist parties have grown significantly in size in several other contexts, which may create difficulties for parties that have previously treated such parties as pariahs, causing bargaining delays when some parties feel pressed to break their pre-electoral commitments.

On a general level, the evidence we present in this article suggests that bargaining delays in contemporary Western Europe are in part due to long-term structural changes such as party-system fragmentation and the rise of new, sometimes extreme parties that have not previously been involved in governing coalitions. However, to understand the causes of bargaining delays in particular cases—such as the drawn-out government formation process in Sweden in 2018–2019—one also needs to consider medium-term party strategic choices. There would not have been a long bargaining delay in Sweden after the 2018 election if there had not been a party in the parliament that was widely shunned by other parties. But that was not enough to cause the exceptionally long government formation process after the 2018 election. To understand that outcome, we must also consider factors that led to the high levels of preference uncertainty and the difficult commitment problems that complicated government formation in Sweden at this time, such as pre-electoral coalitions and lack of familiarity.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (779.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers, as well as the comments and suggestions made by the participants at the ‘Coalition Dynamics: Advances in the Study of the Coalition Life-Cycle’ conference. In addition, we wish to thank Riksbankens jubileumsfond for funding the original project. Jan Teorell wishes to acknowledge sabbatical support from the Wenner-Gren Foundation. Bäck and Hellström would like to thank Vetenskapsrådet (2020-01396) for financial support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hanna Bäck

Hanna Bäck is a Professor of Political Science at Lund University. Her research mainly focuses on political parties, legislators, and governments in parliamentary democracies. Her articles have for example appeared in British Journal of Political Science, Comparative Political Studies, and European Journal of Political Research. [[email protected]]

Johan Hellström

Johan Hellström is a Docent of Political Science at Umeå University. His research focuses on coalition politics, political parties and democratic representation in Parliamentary democracies. He has published books and articles on mainly comparative European politics and is responsible for the (European) Representative Democracy Data Archive—a data research infrastructure for coalition research [[email protected]]

Johannes Lindvall

Johannes Lindvall is the August Röhss Professor of Political Science at the University of Gothenburg. His most recent book is Inward Conquest: The Political Origins of Modern Public Services (Cambridge University Press 2021, with Ben Ansell). He is also the author of Reform Capacity (Oxford University Press 2017), Mass Unemployment and the State (Oxford University Press 2010), and numerous articles in scholarly journals. [[email protected]]

Jan Teorell

Jan Teorell is Lars Johan Hierta Professorial Chair in Political Science at Stockholm University. His research interests include comparative politics, comparative democratisation, state making and party politics. His work has appeared in journals such as the American Political Science Review, Comparative Political Studies, and European Journal of Political Research. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 This article draws on evidence compiled for a Swedish-language book (Teorell et al. Citation2020) but also on new and updated evidence that we have compiled for the article.

2 The following (West European) countries are included in this study: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. The data cover government formation opportunities in these countries over the period 1945 (or the beginning of the present democratic regime) to 2019.

3 Diermeier and Van Roozendaal (Citation1998) include a measure of ‘identifiability’—the availability of pre-electoral government options—in their empirical models, but only as a control variable. Similarly, in a more recent study, Ecker and Meyer (Citation2020) include a control for pre-election coalitions. They find that such coalitions speed up the government formation process significantly.

4 More precisely, Martin and Stevenson (Citation2010) specifies the weight as two times the product for the two parties’ individual portfolio shares unless M=K, when the weight is that party’s squared portfolio share. This ensures that the weight for all party pairs in a given coalition sum to 1.

5 In this case, our approach differs slightly from Martin and Stevenson (Citation2010, 509–510), who instead count the ‘per centage of days …that the two parties have participated in the same cabinet up until that point,’ discounted by an unspecified discount rate ‘that is sufficiently high to ensure that periods of cabinet partnership occurring more than approximately eight years before … are almost completely discounted.’ We try to mimic this approach by using the month as the time unit and a 5 per cent discount rate. This ensures that after 8 years, that is, 96 months, only 0.9596=.007≈0 of a unit shock remains.

6 In the online appendix we show the results from alternative specifications of depreciation rates and ‘weights’ for the familiarity measurement.

7 As former communist parties were increasingly seen as potential coalition partners after the collapse the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold war, we do not count former communist parties that ceased to be communist in the 1990s, or other moderate left parties, as extreme.

8 Bargaining weights for individual parties are measured as the share of cabinets where a party is necessary to produce a majority-winning cabinet of all ‘potential coalitions’ or ‘potential governments’. The latter term refers to the combination of parties, or an individual party, that hypothetically could form a government in some bargaining situation. The normalised Banzhaf’s index goes from 0 to 1, where 1 indicates that there is a single-party majority winner after a parliamentary election.

9 The negative binomial model is preferred over the Poisson model since there are clear signs of over-dispersion in our data.

10 As shown in the online appendix, using Cox proportional hazards models gives results that are nearly analogous to those reported in the article.

11 Since we include country-fixed effects, we are not able to estimate the effects of political institutions such as semi-presidentialism that do not vary or vary very little over time.

12 When we analyse sub-samples of post-election and inter-election government formations or the conditional effect of post-election situations on our main independent variables, the results are fairly similar to the ones presented here.

13 The predictions are based on Model 4 to increase power (as the sample size is somewhat larger), but as seen in , Model 2 would produce similar predictions.

14 The predictions from the different models in are very similar.

15 A government does not automatically resign after an election, but unless the prime minister steps down voluntarily, a compulsory vote of no confidence is held once the new parliament, the Riksdag, is summoned. If the prime minister fails in this vote, the Speaker nominates a new prime minister after consulting all Riksdag parties. The nominee must pass an investiture vote with a negative decision rule. After four unsuccessful investiture votes, parliament is dissolved and new elections are called; this has never happened so far (see, for example, Wockelberg Citation2015).

References

- Bandyopadhyay, Siddhartha, Kalyan Chatterjee, and Tomas Sjöström (2011). ‘Pre-Electoral Coalitions and Post-Election Bargaining’, Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 6:1, 1–53.

- Bergman, Torbjörn (1995). Constitutional Rules and Party Goals in Coalition Formation. Umeå: Umeå universitet (Doctoral dissertation).

- Bergman, Torbjörn, Hanna Bäck, and Johan Hellström (2021). ‘Coalition Governance Patterns across Western Europe’, in Torbjörn Bergman, Hanna Bäck, and Johan Hellström (eds.), Coalition Governance in Western Europe, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 680–726.

- Bergman, Torbjörn, Hanna Bäck, and Johan Hellström, eds. (2021b). Coalition Governance in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bernhard, William, and David Leblang (2006). Democratic Processes and Financial Markets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Blockmans, Tom, Benny Geys, Bruno Heyndels, and Bram Mahieu (2016). ‘Bargaining Complexity and the Duration of Government Formation: Evidence from Flemish Municipalities’, Public Choice, 167:1–2, 131–43.

- Box-Steffensmeier, Janet M., and Bradford S. Jones (2004). Event History Modeling. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Carroll, Royce, and Gary W. Cox (2007). ‘The Logic of Gamson’s Law’, American Journal of Political Science, 51:2, 300–13.

- Coppedge, Michael (2005). ‘Explaining Democratic Deterioration in Venezuela through Nested “Inference”’, in Frances Hagopian and Scott Mainwaring (eds.), The Third Wave of Democratization in Latin America, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 289–316.

- Caulier, Jean-François, and Patrick Dumont (2005). ‘The Effective Number of Relevant Parties: How Voting Power Improves Laakso-Taagepera’s Index’, MPRA Paper 17846, https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/17846.

- Curini, Luigi, and Luca Pinto (2016). ‘More than Post-Election Cabinets: Uncertainty and the “Magnitude of Change” during Italian Government Bargaining’, International Political Science Review, 37:2, 184–97.

- Debus, Marc (2009). ‘Pre-Electoral Commitments and Government Formation’, Public Choice, 138:1–2, 45–64.

- De Winter, Lieven, and Patrick Dumont (2008). ‘Uncertainty and Complexity in Cabinet Formation’, in Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman (eds.), Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 123–58.

- Diermeier, Daniel, and Randolph T. Stevenson (1999). ‘Cabinet Survival and Competing Risks’, American Journal of Political Science, 43:4, 1051–68.

- Diermeier, Daniel, and Peter Van Roozendaal (1998). ‘The Duration of Cabinet Formation Processes in Western Multi-Party Democracies’, British Journal of Political Science, 28:4, 609–26.

- Ecker, Alejandro, and Thomas M. Meyer (2015). ‘The Duration of Government Formation Processes in Europe’, Research & Politics, 2:4. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168015622796.

- Ecker, Alejandro, and Thomas M. Meyer (2020). ‘Coalition Bargaining Duration in Multiparty Democracies’, British Journal of Political Science, 50:1, 261–80.

- Falcó-Gimeno, Albert, and Indridi H. Indridason (2013). ‘Uncertainty, Complexity, and Gamson’s Law’, West European Politics, 36:1, 221–47.

- Fearon, James D. (1995). ‘Rationalist Explanations for War’, International Organization, 49:3, 379–414.

- Franklin, Mark N., and Thomas T. Mackie (1983). ‘Familiarity and Inertia in the Formation of Governing Coalitions in Parliamentary Democracies’, British Journal of Political Science, 13:3, 275–98.

- Golder, Sona N. (2006). ‘Pre-Electoral Coalition Formation in Parliamentary Democracies’, British Journal of Political Science, 36:2, 193–212.

- Golder, Sona N. (2010). ‘Bargaining Delays in the Government Formation Process’, Comparative Political Studies, 43:1, 3–32.

- Luebbert, Gregory M. (1986). Comparative Democracy. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Hagevi, Magnus (2015). ‘Bloc Identification in Multi-Party Systems: The Case of the Swedish Two-Bloc System’, West European Politics, 38:1, 73–92.

- Hellström, Johan, Torbjörn Bergman, and Hanna Bäck (2021). Party Government in Europe Database (PAGED). Main sponsor: Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (IN150306:1). Available at https://erdda.org.

- Hellström, Johan, and Jonas Lindahl (2021). ‘Sweden: The Rise and Fall of Block Politics’, in Torbjörn Bergman, Hanna Bäck, and Johan Hellström (eds.), Coalition Governance in Western Europe, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 574–610.

- Laakso, Markku, and Rein Taagepera (1979). ‘Effective Number of Parties’, Comparative Political Studies, 12:1, 3–27.

- Lindvall, Johannes, Hanna Bäck, Carl Dahlström, Elin Naurin, and Jan Teorell (2020). ‘Sweden’s Parliamentary Democracy at 100’, Parliamentary Affairs, 73:3, 477–502.

- Lindvall, Johannes, Hanna Bäck, Carl Dahlström, Elin Naurin, and Jan Teorell (2017). Samverkan och strid i den parlamentariska demokratin. Stockholm: SNS.

- Lindvall, Johannes, and Jan Teorell (2022). ‘Konfliktstrukturen i riksdagen och regeringsbildningen 2018–2019’, in Patrik Öhberg, Henrik Oscarsson, and Jakob Ahlbom (eds.), folkviljans förverkligare, Gothenburg: SOM-Institutet, 133–45.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Randolph T. Stevenson (2001). ‘Government Formation in Parliamentary Democracies’, American Journal of Political Science, 45:1, 33–50.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Randolph T. Stevenson (2010). ‘The Conditional Impact of Incumbency on Government Formation’, American Political Science Review, 104:3, 503–18.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Georg Vanberg (2003). ‘Wasting Time? The Impact of Ideology and Size on Delay in Coalition Formation’, British Journal of Political Science, 33:2, 323–32.

- Müller, Wolfgang C., and Kaare Strøm, eds. (2000). Coalition Governments in Western Europe, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sartori, Giovanni (1976). Parties and Party Systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Teorell, Jan, Hanna Bäck, Johan Hellström, and Johannes Lindvall (2020). 134 Dagar: Om regeringsbildningen efter valet 2018, Göteborg: Makadam.

- Warwick, Paul V. (1992). ‘Ideological Diversity and Government Survival in Western European Parliamentary Democracies’, Comparative Political Studies, 25:3, 332–61.

- Wockelberg, Helena (2015). ‘Weak Investiture Rules and the Emergence of Minority Governments in Sweden’, in Bjørn Erik Rasch, Shane Martin, and José Antonio Cheibub (eds.), Parliaments and Government Formation, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 233–49.