Abstract

Europe remains a destination of an ongoing influx of asylum seekers. The attempts to build an EU-wide political consensus around refugee policy have so far failed. This article provides a perspective on EU citizens’ preferred policy towards refugees and asylum seekers at both the EU and domestic levels. A hidden policy consensus is identified in which European citizens across all social and ideological backgrounds prefer refugees to have the right to work but their freedom of movement to be restricted while their application for asylum is being processed. At the same time, the mode of refugee allocation between countries, which has been prominent in political debates across Europe, is relatively unimportant to respondents, as they focus on the domestic level rather than EU-level policy. The widespread consensus on support for refugees’ participation in the labour market may unite EU citizens around cautious hospitality by deemphasising allocation principles, and stressing country-level solutions.

Recent developments in Afghanistan and on the Polish-Belarusian border, along with the war in Ukraine make the European Union (EU) refugee policy fundamentally important for millions of people. Nevertheless, so far the Member States have failed to develop a common policy suitable for addressing the challenges that the EU faces. The Refugee Crisis in 2015 demonstrated the lack of solidarity among the Member States in terms of managing the flow of asylum applications, and a growing gap in asylum practices has developed among them ever since. Existing research on Europeans’ preferences in respect to asylum seekers either focuses on the management of the flow of asylum seekers within the EU and between the EU and non-EU countries (Bansak et al. Citation2017; Jeannet et al. Citation2021; Vrânceanu et al. Citation2022) or on general preferences on refugee policy that speak only indirectly to specific policy solutions (Thravalou et al. Citation2021; Heizmann and Huth Citation2021; Van Hootegem et al. Citation2020; Abdelaaty and Steele Citation2022). Consequently, we lack evidence on what nature of refugee policy European citizens want and whether a workable consensus among Member States is possible.

In this article we employ a multifactorial survey experiment to examine European citizens’ preferences regarding key aspects of EU-level and domestic refugee policy, including the mode of allocation of refugees among Member States, level of EU border protection, asylum seekers’ access to the labour market and freedom to move around the country while under the asylum procedure, and, lastly, the policy cost to an average household. We also provide an exploration of country- and individual-level heterogeneity. Our design addresses main issues identified by previous research as relevant in the context of an immigration crisis, such as attitudes towards the EU-level immigration policy, concerns related to security or labour market competition, and welfare strain. Unlike most research in the field, we focus specifically on refugees and not on a generic category of ‘immigrants’.1 Our sample of ten countries includes Member States that vary in their experience with flows of immigrants and asylum seekers, position on the current EU-level arrangements, and domestic policies on asylum seekers, which allows for generalising across EU countries.

Our findings suggest that there exists a hidden policy consensus (Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2015), in which European citizens across all social and ideological backgrounds prefer refugees to have the right to work but their freedom of movement to be restricted while their asylum applications are processed. At the same time, the mode of refugee allocation among countries, which has been prominent in the political debate across Europe, is relatively unimportant to citizens, as they focus on domestic and not EU-level policy. These results point to the political rift over immigration and refugee policy at the EU level being driven by the political elites rather than reflecting voters’ expectations (Morales et al. Citation2015; Hutter and Kriesi Citation2022; Krzyżanowski et al. Citation2018). Instead, citizens’ focus on the refugees’ participation in the labour market may allow to unite EU citizens around cautious hospitality by de-emphasising allocation principles, and stressing country-level solutions.

Citizen preferences on refugee policy

While research on general attitudes towards immigrants and asylum seekers in Europe and beyond is vast and growing (Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2014; Dinesen and Hjorth Citation2020), only a few studies directly address preferences towards refugee policy. To start, Bansak et al. (Citation2018) analyse preferences on the mode of refugee allocation among Member States and find that while there is considerable support for proportional allocation based on the relocation of asylum seekers, it is moderated by the information about the consequences of such a solution for each country’s refugee intake. Second, Jeannet et al. (Citation2021) apply a conjoint experiment and find that Europeans choose solutions that limit the numbers of admitted refugees and prefer conditions which minimise the financial burden they may impose on the receiving country. And finally, Vrânceanu et al. (Citation2022), also using a conjoint experiment, find support for some key features of the current EU-Türkiye agreement, as well as for increased financial flows to the Member States overburdened with asylum applications, yet this support is conditional on increased EU border control. All of these studies focus on the volume and conditions of refugee intake, as the management of refugee flows was a strongly politicised and divisive issue during the 2015 Refugee Crisis (Krzyżanowski Citation2018; Gianfreda Citation2018; Triandafyllidou Citation2018). Some other studies attempt to capture general preferences and attitudes towards refugee policy—asking, for example, whether ‘the number of asylum seekers should be better distributed among all EU Member States’, ‘the government should be generous in judging asylum applications’ or ‘the refugees should be allowed to bring family members’ (Van Hootegem et al. Citation2020; Heizmann and Ziller Citation2019; Abdelaaty and Steele Citation2022). While these findings are useful for exploring the over-time dynamic of attitudes towards refugee policy and its distinctiveness from attitudes towards immigration policy, their relevance for designing specific policy solutions is limited.

European policy on refugees

The Refugee Crisis of 2015 demonstrated significant problems with coordinating policy response at the EU level as well as a deep politicisation of the issues of asylum (Gianfreda Citation2018; Krzyżanowski Citation2018). The attempts to introduce an allocation rule based on the principle of solidarity among the EU Member States in the face of a heavily increased burden of asylum applications experienced by some of them failed due to open obstruction by several countries (e.g. Poland or Hungary), while some of those declaring willingness to accept relocated asylum applicants in reality admitted very few (e.g. Spain or Belgium).2 In response, the European Commission proposed a modified ‘flexible solidarity’ approach in its New Pact on Migration and Asylum, whereby in the case of emergency, Member States unwilling to accept relocated asylum applicants from other EU countries can choose to take financial responsibility for returning failed applicants from these Member States to their home countries.3 Thus, in our research on preferences on the mode of refugees’ allocation, we include both relocational solidarity and fiscal solidarity—following the EU Commission’s expectation that the latter policy will satisfy more reluctant Member States by offering them an opportunity to uphold the principle of solidarity through financial obligations instead of accepting relocated asylum seekers.4 Furthermore, in recognition of the multidimensional and multi-level structure of the policy towards refugees and asylum seekers, as well as citizens’ preferences reflecting multiple concerns discussed above, we supplement the EU-level policy dimensions (allocation of refugees to Member States and the EU border control) with domestic policy options (right to work, freedom of movement within a country and policy cost for an average household—presented in the local currency). Citizen preferences on domestic policy solutions towards refugees are significantly under-researched, even though these ‘proximate’ national factors correspond directly to the immigration-related concerns that previous research has identified and thus are likely to be a driving force shaping citizens’ evaluations of proposed refugee policy. Combined, these EU- and national-level attributes address the key policy aspects relevant for understanding the structure of European citizens’ refugee policy preferences. In we list all attributes and attribute levels employed in our survey experiment.

Table 1. Overview of the policy profile attributes and levels.

Policy areas and citizens’ concerns

While we are interested in preferences for specific policy solutions, such preferences may, at least in part, reflect broader sentiments towards immigrants and asylum seekers. Key fears voiced by the members of receiving societies are related to perceived cultural threat (Davidov et al. Citation2020; Lucassen and Lubbers Citation2012; Callens and Meuleman Citation2017), physical threat/security (Branton et al. Citation2011; Legewie Citation2013; Hopkins Citation2010; Fitzgerald et al. Citation2012) and economic concerns (Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2015; Dinesen and Hjorth Citation2020; Fietkau and Hansen Citation2018; Jeannet et al. Citation2021; Heizmann and Huth Citation2021). Fears about the clash of values (symbolic threat) and about terrorist attacks and crime (security threat) have been shown to affect whether European citizens are willing to accept an increased number of refugees and asylum seekers, but they are also likely relevant for whether they are willing to welcome refugees’ presence in the social space or prefer them to be isolated (Alrababa’h et al. Citation2021; Legewie Citation2013; Ferrín et al. Citation2020; Manevska and Achterberg Citation2013; Davidov et al. Citation2020; Green et al. Citation2016; Gorodzeisky and Semyonov Citation2020). This makes solutions adopted to control the admission and allocation processes for refugees and their right to move freely around the country are likely to affect popular acceptance of a refugee policy. Research on attitudes towards immigrants and asylum seekers points to the concerns about labour market structure and participation on the one hand, and welfare state burden on the other as relevant drivers of hostile attitudes. Yet some studies find support for the ego-tropic perspective (Malhotra et al. Citation2013), others for the socio-tropic (Bansak et al. Citation2016; Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2014; Fietkau and Hansen Citation2018), some for neither (Alrababa’h et al. Citation2021; Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2015), and still others for both, as different groups of respondents in different macro-economic contexts formulate different concerns and expectations in relation to an influx of refugees and asylum seekers (Abdelaaty and Steele Citation2022; Van Hootegem et al. Citation2020; Heizmann and Huth Citation2021; Heizmann and Ziller Citation2019). Thus, different scenarios of labour market participation (i.e. restricted, unrestricted or regulated access for asylum seekers) are likely to attract different sentiments from different groups, while the high policy cost should resonate most with respondents concerned with the fiscal burden of providing protection to asylum seekers (Naumann et al. Citation2018; Kolbe and Kayran Citation2019). Overall, the policy dimensions we investigate reflect a range of general explanations for support for immigration more broadly.

Given that we are interested in understanding the dynamics of citizen support for refugee policy, we also draw on previous research on general sentiments towards immigrants and asylum seekers, and their determinants, to explore how individual-level factors influence preferences regarding specific policy solutions. The literature shows that both attitudes and policy preferences are stratified, and research converges on a number of individual characteristics; namely, gender, educational qualifications, age and current personal economic situation, as well as political ideology and national identity (Adida et al. Citation2019; McLaren and Paterson Citation2020; Manevska and Achterberg Citation2013; Aschauer and Mayerl Citation2019; Onraet et al. Citation2021; Berning and Schlueter Citation2016; Dancygier et al. Citation2022; Kende et al. Citation2019; Hasbún López et al. 2019; Nicoli et al. Citation2020). Research into the individual determinants of attitudes towards asylum policy in Europe shows some stable patterns: women, younger people, and those with higher levels of education and better economic situation are supportive of a more open and generous policy towards refugees and asylum seekers, and so are those leaning towards the political left and with weaker national identity and a stronger attachment to the EU (Van Hootegem et al. Citation2020; Heizmann and Ziller Citation2019; Abdelaaty and Steele Citation2022).

Consequently, our key questions are: (1) Which policy features find support among the general EU public? (2) Are preferences driven by EU-level or domestic policy attributes? (3) Do different groups support different policy models? And finally, (4) Can the EU achieve a consensus on the issue of refugees and asylum seekers?

Data and methods

In order to answer these questions we use a multifactorial survey experiment including the above-mentioned EU-level and domestic refugee policy attributes. By employing a forced choice approach in the experiment, where respondents have to choose between two randomly drawn policy profiles, we account for the competing nature of attributes’ levels and approximate real-life political choices while reducing social desirability bias. However, to uncover the absolute desirability of attributes and their respective levels, we supplement the forced choice with an analysis based on the ratings of policy profiles (on a 1 to 7 scale).

The study covers the following 10 Member States that were selected to represent different levels of exposure (number of asylum applicants per capita) and different types of policy (lenient/restrictive) towards asylum seekers: Austria, Denmark, Germany, Portugal, Spain, Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia. The countries that experienced the highest exposure during the 2015 Refugee Crisis are Germany, Austria, Spain, Slovenia and Hungary, while Poland, Portugal and Bulgaria experienced the lowest.5 Hungary, Poland and Bulgaria have been noted for non-compliance with the EU regulations regarding asylum procedure, reception conditions, detention and protection. Procedurally, Denmark, Portugal, Slovenia, Croatia and Poland present open systems (with minimal restrictions on asylum seekers’ right to work and freedom of movement), Germany and Austria are restrictive, while Hungary, Bulgaria and Spain are mixed, although the reality often diverts from the adopted legal principles (Schultz et al. Citation2021).6 Finally, the 10 Member States in our study represent different positions on the issue of relocation of asylum applicants from overburdened Member States: Poland, Hungary and Denmark are the three countries in our sample that do not accept relocated applicants, and Denmark is revoking residency permits, even though no one has been forced to leave the country yet.7 It is the relocation-reluctant countries that the fiscal solidarity principle is largely aimed at by offering an option to ‘buy out’ in an effort to preserve unity and solidarity in the EU.

Our survey experiment is a fully randomised conjoint design, following the work of Hainmueller et al. (Citation2014). This is a popular design for the study of attitudes towards immigrants and refugees (Adida et al. Citation2019; Bansak et al. Citation2016; Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2015) as well as policy preferences, including refugee policy (Jeannet et al. Citation2021; Vrânceanu et al. Citation2022; Nicoli et al. Citation2020; Bechtel et al. Citation2020). We include five attributes in our conjoint experiment: i) allocation of refugees among Member States, ii) EU border control, iii) right to work, iv) freedom of movement while under the asylum procedure, and v) the policy’s yearly cost per capita. In our conjoint we randomise all 12 levels of the five attributes, which results in 72 possible policy profiles. We do not observe any logical inconsistencies in the combinations of the levels of the attributes, thus we do not introduce conditional independence to our design and offer a completely independent randomisation (Hainmueller et al. Citation2014). This allows us to generate an unbiased estimate from simple differences in means. We do, however, eliminate the probability of a draw of two policy profiles that are the same on all attributes’ levels bar the cost attribute, following the suggestions of Hainmueller et al. (Citation2014) to address improbable choices.

Respondents had to choose one policy profile from a set of two, and then they were asked to rate each of the two policy profiles on a scale from 1 to 7; they repeated this task six times (in we offer an example of a choice set).8 Thus, we presented 12 policy profiles to 3,349 respondents in 10 Member States, which translates to a total of 40,188 policy profiles shown to respondents and, consequently, offers over 370 choice and rating outcomes for each of the 108 possible profiles.9

Our sample is quota-representative at the country level in respect to age, gender, education and geographical location at the NUTS1 level (NUTS2 for smaller states). For a comparison of each country in our sample with the Eurostat data please see Table A1 in the online appendix. We have further inspected the quality of our data and compared it with the latest (9th) round of the European Social Survey (ESS) in the respective countries—using the questions in our survey that are drawn from the ESS (see A.3 for the list of questions). We only observe marginal differences between the two samples and offer a balancing exercise where we compare the results from our survey with the ESS9 data in Table A2 in the online appendix. The sample was collected by Bilendi & Respondi (we worked with the branch of the company based in London).

Finally, we registered our study, before the data collection began, with a Pre-Analysis Plan, in which we listed our research design and hypotheses. In the article, we highlight which of the empirical tests were pre-registered. We also stored a visual archive of our survey experiment, with a screenshot of each page of the survey. In addition, we offer an overview of translations for all the components of the study in all the languages in which the study was conducted in an accessible format following the Master English Questionnaire for this study.10

Results

Overall preferences of Europeans

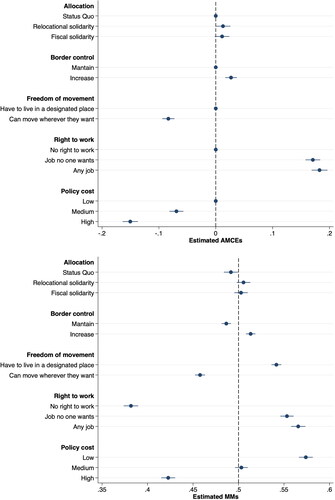

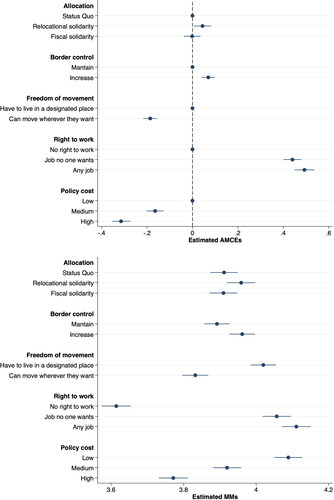

In this section we report two estimands—the Average Marginal Component Effects (AMCE) and the Marginal Means (MM) for both forced choice () and rating analyses () (Hainmueller et al. Citation2014; Leeper and Slothuus Citation2014).11 The AMCE allows us to study multidimensional preferences and offer a causal interpretation of the role of a level of an attribute in respect to favourability of a refugee policy profile, relative to a baseline. However, the AMCE is suitable only for causal analysis and is of limited use for descriptive inferences about respondents’ preferences. We address this limitation with the use of MM that allows to draw descriptive inferences about preference differences across subgroups in a multidimensional experimental setting (Leeper et al. Citation2020).12

Figure 2. Refugee policy attributes and the probability of accepting the policy by respondents—(a) causal effect of attributes’ levels relative to baseline computed with the AMCE, and (b) descriptive summary of attributes’ levels computed with the MM. Dots with horizontal lines are point estimates from linear least squares regressions. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals computed from robust standard errors clustered by respondent. Regression table displaying underlying results and a robustness test using continuous policy rating outcome and regression weighted by population and by quality is available in the online appendix (Table A4).

Figure 3. Refugee policy attributes and the rating of a policy by respondents—(a) causal effect of attributes’ levels relative to respective country baseline computed with the AMCE, and (b) descriptive summary of attributes’ levels computed with the MM. Dots with horizontal lines are point estimates from linear least squares regressions. Table A4 shows the underlying analysis. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals computed from robust standard errors clustered by respondent. Estimands based on the continuous policy-rating (1–7) outcome variable.

Despite that the EU-level policy receives widespread attention from researchers and commentators alike, the two EU-level policy attributes in our model—allocation and EU border control—are the least relevant for understanding support for a given policy profile (). In panel (a), using AMCE, we observe that a policy profile is more likely to be selected if the allocation attribute level changes from the (baseline) status quo to either relocational solidarity or fiscal solidarity, however only at the p = .1 significance level (β = .0127, p = .058, 95% CIs (-0.0004, .0258) and β = .0111, p = .090, 95% CIs (-0.0017, .0240), respectively). The MMs in panel (b) signal that this effect is driven by the dislike for the status quo policy in respect to allocation, as neither relocational solidarity nor fiscal solidarity has a significant effect on the probability of selecting a policy profile (p = .1504 and p = .4630, respectively); the effect of the status quo, while small, is negative and statistically significant (β = .4916, p = .0335, 95% CIs (.4839, .4993)).13

In respect to border control, we observe from panel (a) of that a change to an increased level of border control, relative to maintaining the current level, positively affects the probability of a policy profile being selected (β = .0268, p = .001, 95% CIs (.0167, .0370)). Panel (b) signals that profiles where the border control attribute level is maintained are less likely to be selected and, consistently with the AMCE, policy profiles with an increased border control are more likely to be selected, on average. Both coefficients for the MM estimation are significant at p < .001.

The remaining three attributes are related to domestic policy. It transpires that whether asylum seekers work or not in their host country is decisive for whether a given policy profile is selected. It does not matter whether it is a job no one wants or any job available (β = .1708., p < .001, 95% CIs (.1578, .1837) and β = .1825, p < .001, 95% CIs (.1686, .1965), respectively). MM estimates in panel (b) show that these effects are largely driven by the baseline level—no right to work—as policies with this option are least likely to be chosen (β = .3817., p < .001, 95% CIs (.3738, .3897)). At the same time, European citizens are negatively predisposed towards freedom of movement of refugees and would prefer to see them confined to a designated place (β = −.0834, p < .001, 95% CIs (-0.0941, −0.0727), in panel (a)). Panel (b) shows that offering freedom of movement to refugees under asylum procedure makes a policy profile less likely to be selected on average, while confining them to a designated place makes a policy more likely to be selected, on average (β = .4577, p < .001, 95% CIs (.4522, .4632) and β = .5416, p < .001, 95% CIs (.5362, .5470), respectively).

Finally, in panel (a) we observe that a change from low policy costs (0.0005% real GDP per capita) to medium or to high costs (respectively, 0.0025% real GDP per capita and 0.005% real GDP per capita) causes a decrease in the average probability of a profile being selected (β = −.0692, p < .001, 95% CIs (-0.0815, −0.0569) and β = −.1504, p < .001, 95% CIs (-0.1638, −0.1370), respectively). Both coefficients are statistically significantly different from one another at p < .01—with, intuitively, policy cost level high being less preferred to medium. The MM estimates inform us that low policy cost increases the probability of a profile being selected, and high policy cost level decreases the probability of a profile being selected (both statistically significant at p < .001). Respondents appear indifferent about the medium policy cost.

depicts preferences in respect to refugee policy based on the rating outcome variable, which complements our main findings. We observe a structure of preferences largely similar to what has been identified using the forced choice outcome for both quantities of interests—the AMCE (panel (a)) and the MM (panel (b)). In respect to particular attributes, using MM, we see that no right to work is rated the lowest (β = 3.6142, p < .001, 95% CIs (3.5740, 3.6545)) and any job the highest (β = 4.1109, p < .001, 95% CIs (4.0713, 4.1505)), with job no one wants and low cost rated at a similarly high level (β = 4.0569, p < .001, 95% CIs (4.0179, 4.0958) and β = 4.0888, p < .001, 95% CIs (4.0506, 4.1270), respectively). Interestingly, the analysis based on the rating outcome variable shows even more clearly what the forced choice outcome has already indicated—that there is no significant difference between the evaluation of different modes of refugee allocation (status quo is rated at β = 3.9114, p < .001, 95% CIs (3.8730, 3.9498), relocational solidarity at β = 3.9587, p < .001, 95% CIs (3.9197, 3.9978) and fiscal solidarity at β = 3.9099, p < .001, 95% CIs (3.8716, 3.9481)).

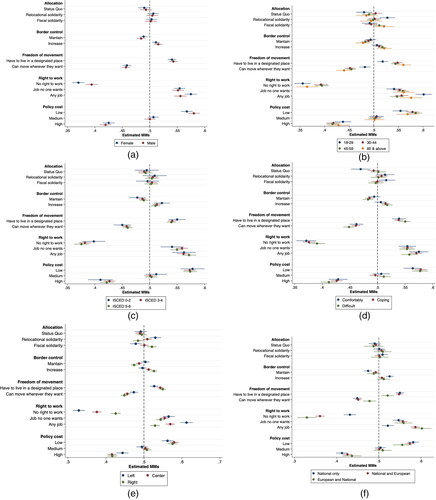

Preference heterogeneity related to socio-economic background and political attitudes

We pre-registered a number of tests for potential heterogeneity in our findings driven by education, political preferences, age and gender. In addition, we supplement these analyses with post-hoc (i.e. chosen after the data has been collected) tests of heterogeneous effects by income satisfaction and national vs European identity. In general, our heterogeneity tests indicate that policy preferences are related to attitudes (i.e. ideology and identity), while the effect of the remaining characteristics is relatively small, as they affect the strength rather than the direction of preferences.

Regarding gender (a), our results seem consistent with expectations derived from research on general attitudes towards immigrants and asylum seekers as well as policy preferences (Aschauer and Mayerl Citation2019; Van Hootegem et al. Citation2020; Heizmann and Ziller Citation2019), but only in the area of asylum seekers’ right to work, where women seem more open than men are. They are more against no right to work than men are and more for any job than men are. There are no other statistically significant differences between genders. Age (b) is also related to policy preferences in a manner consistent with previous research (McLaren and Paterson Citation2020; Onraet et al. Citation2021; Van Hootegem et al. Citation2020; Heizmann and Ziller Citation2019), indicating that younger people are more positively disposed towards refugees and asylum seekers. It is the youngest respondents (aged 18–29) that are more supportive than anyone else of relocational solidarity; less supportive of confining refugees to a designated place and less against their freedom of movement. In contrast to existing research on attitudes towards refugees and asylum seekers (McLaren and Paterson Citation2020; Manevska and Achterberg Citation2013; Aschauer and Mayerl Citation2019; Onraet et al. Citation2021; Van Hootegem et al. Citation2020; Heizmann and Ziller Citation2019), education does not stratify refugee policy preferences in our data.14 Also, income situation (d)15 is only weakly related to policy preferences, yet the direction of the effects is consistent with previous research (Aschauer and Mayerl Citation2019; Van Hootegem et al. Citation2020). The only group that has relatively distinctive preferences are those who ‘live comfortably on the present income’, as in terms of allocation policy they are against the status quo, while this effect is statistically insignificant for the remaining income categories. The respondents who ‘live comfortably’ are not affected by the border control option, while the two groups that are less well-off financially favour the increase of border control and are less likely to choose policies with the current level of border control. Interestingly, while income situation is related to these two EU-level policy dimensions, it does not explain any of the domestic policy options.

The most significant moderating effects we find are for ideology and identity. In panel (e) of we present results on the preferences based on respondents’ self-placement on the Left-Right scale.16 Following previous research on the heterogeneous meaning of ideological ‘Left’ and ‘Right’ in Western and Eastern Europe (De Vries and Tillman Citation2011; Kostelka and Rovny Citation2019; Allen Citation2017), we have analysed the effect of ideology separately for both regions (Table A12), yet few significant differences were present.17 For simplicity, in the pooled sample is presented, and we report the relevant regional differences in the discussion below. We have observed that respondents on the Left and Right have markedly different preferences regarding the EU-level policy dimensions, with the Centre most of the time either being indifferent about a given dimension or overlapping with the Right. Right-wing respondents are strongly against relocational solidarity, but this result is driven by the Eastern European Right, while Left-wing respondents are strongly for relocational solidarity, but this time the result is driven by the Western European Left. In the case of fiscal solidarity, Right-wing respondents are supportive of it (both East and West), while the Left-wing ones are against it. Ideology also influences preferences regarding border control: Rightwing and Centre respondents are against maintaining the current level of border protection and for increasing the level of border protection, while the Left-wing respondents are not affected by either of the two options. Regarding domestic policy towards refugees, ideology-related differences are more subtle, as all groups have similar preferences, with the Left being less against freedom of movement and less for living in a designated place than anyone else, and more against no right to work and more for right to work than anyone else. Finally, the highest policy cost is less discouraging for the Left than for anyone else, while there are no differences considering other cost levels.

Figure 4. Heterogeneity: probability of accepting a policy by respondents across levels of attributes—(a) Gender, (b) Age, (c) Education, (d) Income situation, (e) Ideology and (f) National vs European identity—descriptive summary of attributes’ levels computed with the MM. Dots with horizontal lines are point estimates from linear least squares regressions. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals computed from robust standard errors clustered by respondent. Regression table displaying underlying results is available in the online appendix, respectively, in Tables A6–A11.

In terms of right to work, all ideological groups are unfavourable towards no right to work, but Left is most against it, followed by the Centre and the Right; all between-group differences are statistically significant at p < .001. While all groups are similarly supportive towards job no one wants, they are differently favourable towards any job. The Right is least favourably disposed towards this policy option, and the Centre is statistically significantly more favourable towards it. For both those on the Right and Centrists, the level of support for any job is not statistically significantly different than their support for job no one wants. In contrast, the Left is the most supportive of any job, and it is also more supportive of this option than of job no one wants. Finally, in terms of the policy cost, the only statistically significant difference is that of the Left being less against high cost than the Centre and the Right. While all these effects seem consistent with previous research (Abdelaaty and Steele Citation2022; Adida et al. Citation2019; Heizmann and Ziller Citation2019; Berning and Schlueter Citation2016), with Left-leaning voters more open and liberal in their attitudes towards refugees and asylum seekers than the Right-wingers, the Left’s support for limiting asylum seekers’ freedom of movement comes as a surprise.

Respondent’s identity18—National vs European—does not differentiate policy preferences regarding the mode of refugee allocation, but it does in respect to the EU border control, as those who declare National identity as their only one are supportive of border control increase and against maintaining the current level of border control, while those who declare European identity (as dominant or the only one) are not affected in their decisions by this policy dimension. In contrast, those with European identity as dominant or the only one are the most negatively predisposed towards no right to work and most favourably towards any job, while their preference for the policies containing the job no one wants option are not statistically significantly different than the preferences of the other two categories, for whom this option is the most favoured one. In contrast, those declaring National identity as the only one are much less strongly negatively predisposed towards the no right to work option and do not strongly favour the any job option. Finally, in terms of preferences on asylum seekers’ freedom of movement, respondents with National identity as the only or dominant one more strongly favour restrictive solutions and are put off by the solution allowing freedom of movement, in comparison with the respondents with European identity, yet these are only differences of degree and not direction of preference.

Overall, heterogeneity in policy preferences can be linked predominantly to attitudes and not to respondents’ socio-economic background. The issues of relocational and fiscal solidarity resonate differently with Left- and Right-wingers; however, it is mostly the Eastern European Right that are against relocation and the Western European Left that are for relocation of asylum seekers. In contrast, fiscal solidarity is equally popular among the Right and unpopular among the Left across Europe. The Left is not affected by the level of border control, but is the most progressive in terms of access to the labour market. Respondents declaring National identity as the only or dominant one would prefer an increase of border control and are reluctant to grant refugees and asylum seekers freedom of movement and right to take a job, while those with European identity are unaffected by any of the EU-level policy options (allocation and border control) and are very open regarding refugees’ right to work.

Flexible solidarity will not bring unity

It is perhaps surprising that allocation of refugees is the least important policy attribute of those presented to the respondents, given that this was a highly divisive issue during the 2015 Refugee Crisis, with a number of countries (Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic) breaking the EU regulations and in 2017 being referred by the EC to the EU Court of Justice, which subsequently confirmed the infringement. The new flexible solidarity approach has been intended to provide an option (fiscal solidarity) for the countries unwilling to accept relocated asylum seekers, to support other, overburdened Member States. This raises the question whether flexible solidarity will enable to reach a consensus across countries in terms of allocation of refugees.

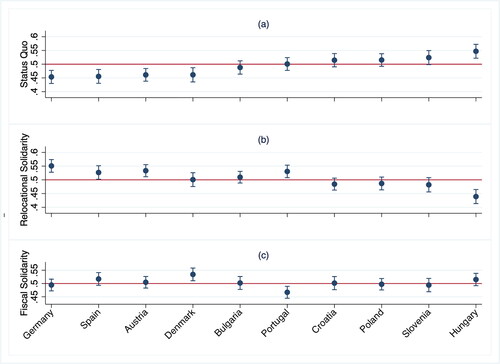

In , we present the MM estimates subset for the allocation dimension by country. In panel (a) we depict the coefficients for status quo, in panel (b) relocational solidarity, and in panel (c) fiscal solidarity. Only one country—Hungary—is in favour of the current principle of allocation of asylum seekers, but in Slovenia the preference for status quo only marginally misses conventional significance levels. Germany, Austria, Spain and Denmark are against it, while for other countries this mode of asylum seekers’ allocation neither increases nor decreases the probability of choosing a policy profile. In contrast, citizens from Germany, Austria, Spain and Portugal are more likely to choose a given policy if it contains relocational solidarity, while in Hungary this option significantly lowers such probability. Finally, most countries are indifferent towards fiscal solidarity, as it only increases the probability of choosing a given policy in Denmark and lowers it in Portugal. Considering the remaining four policy attributes, there is a remarkable cross-country consensus regarding policy preferences; the only differences appear in the degree of importance of particular attribute levels, but not in the direction of their effects. Equally importantly, the impact of the allocation policy attribute is relatively weak in all countries, as only in Hungary does the strength of the effects of status quo, relocational solidarity or fiscal solidarity rival (but not exceed) the strength of the effects of the right to work or policy cost ( and Table A13 in the online appendix).

Figure 5. Allocation: probability of accepting a policy by respondents across countries—descriptive summary of attributes’ levels computed with the MM. Dots with horizontal lines are point estimates from linear least squares regressions. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals computed from robust standard errors clustered by respondent. Regression table displaying underlying results is available in the online appendix in Table A14.

Discussion and conclusion

The key objective of the European Commission in the context of a continuous influx of immigrants is to advance the common EU policy on refugees and asylum seekers in a direction that will enhance the principle of solidarity between Member States. Nevertheless, past experiences have shown that it is a challenging task. The key question for European policy makers is therefore: Which policies do European citizens support? And are they united or divided in their preferences? While we do find some cross-country heterogeneity in preferences for EU-level policy regarding the mode of refugee allocation, these effects are arguably weak. The majority of countries—with the exception of Hungary and Slovenia—are against the current mode of asylum seekers’ allocation, only some countries (Germany, Austria, Spain and Portugal) favour relocational solidarity, and only one (Denmark) favours fiscal solidarity, thus—paradoxically—fiscal solidarity is not attractive for citizens in the countries it was aimed at by the Commission. Importantly, the mode of refugees’ allocation is of limited importance for policy choice in all countries, in comparison with other policy attributes.

At the same time we have identified a hidden consensus (Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2015) regarding domestic policy, as EU citizens generally want refugees to work while under the asylum procedure: in all countries and across all respondent groups, policies containing the option of refugees taking any job or job no one wants were more likely to be chosen, and those containing no right to work were less likely to be chosen. Somewhat related to that is the fact that respondents are discouraged by a high policy cost and encouraged to choose a low policy cost. Both dimensions—right to work and low policy cost—show that limiting the expected fiscal burden of processing asylum applications and accommodating the refugees while under procedure is the concern that unites the EU public, and we find no evidence for labour market protectionism, as job no one wants is never a preferred option over any job. This corresponds to the earlier research identifying socio-tropic concerns as an important factor shaping attitudes towards immigrants and asylum seekers (Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2015; Weiss and Tulin Citation2021; Callens and Meuleman Citation2017). Furthermore, the European public appears largely committed to the asylum procedure as a means of verification of refugees’ right to remain in a country of choice, as it prefers to see refugees’ freedom of movement limited until their eligibility for asylum is confirmed and the status is granted, which in turn is in line with earlier evidence on the relevance of immigrants’ perceived deservingness (Bansak et al. Citation2016; Nielsen et al. Citation2020). These findings suggest the presence of cautious hospitality towards refugees in Europe, and they speak to the ongoing relevance of a decades-long debate about the European Social Model in the context of immigration. In particular, they show that there exists public support for the harmonisation of refugees’ rights and entitlements across Member States, as European citizens wish refugees to not be dependent on welfare, but to contribute to it (Bloch and Schuster Citation2002; Düvell and Jordan Citation2002).

Finally, our results show that where Member States can exercise their right to structure policy specifically to cater to the expectations of their citizens, i.e. at the level of internal, domestic regulations, there is largely agreement in terms of preferred policy solutions, and neither ideology nor national identity can be exploited to mobilise voters around mutually exclusive policy options. At the same time, at the EU level, where consensus is necessary to advance the common European policy on asylum seekers, we witness considerable heterogeneity. The role played by political ideology in structuring preferences towards different forms of exercising solidarity with other Member States shows that while relocation remains an issue that can be successfully used to mobilise Right-wing voters in Eastern Europe, it does not have the same potential among Right-wing voters in Western Europe. Fiscal solidarity does not provide any form of leverage, as despite the European Right-wing citizens being united in support for this type of solidarity, the Eastern European Left is strongly against it. As a result, preferences concerning the EU-level regulations on allocation of refugees will most likely continue to be politically exploited along the lines of more general anti-EU sentiments within and between old and new Member States. However, while flexible solidarity is unlikely to deliver a fully fledged policy solution, an effective base for the managing of future immigration crises can be built on coordinated efforts to encourage integration and labour market participation of refugees and asylum seekers, as both Left and Right have identical preferences in this regard. Overall, the main contribution of our research lies in demonstrating that despite the cross-country and ideological differences regarding preferred modes of managing refugee and asylum-seeker flows, a pan-European consensus can be built by addressing the socio-tropic economic concerns shared by citizens of all Member States. The Temporary Protection Directive, activated in response to the influx of refugees from Ukraine, guarantees wider provisions in terms of freedom of movement and right to work in the EU than any of the EU Members has offered to asylum seekers so far, yet it has not sparked any wide protests, and the majority of Europeans remain committed to providing help and protection to refugees and asylum seekers (Kyliushyk and Jastrzebowska Citation2023).

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (624.8 KB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their comments. An earlier version of this paper was presented at Political Science Seminar, Nuffield College, University of Oxford, and University of Groningen Political Economy Colloquium.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Natalia Letki

Natalia Letki is Associate Professor at the Faculty of Political Science and International Studies and Centre for Excellence in Social Sciences at the University of Warsaw. Her research interests include attitudes and behaviour towards public goods, social cohesion, social trust, and corruption. [[email protected]]

Dawid Walentek

Dawid Walentek is a post-doctoral researcher in the ‘Valuing Refugee Policy’ project. His work focuses on conflict and cooperation in international relations. Dawid received the START Award 2022 from the Polish Foundation for Science. [[email protected]]

Peter Thisted Dinesen

Peter Thisted Dinesen is Professor of Political Science at University College London and the University of Copenhagen. His research focuses on, inter alia, social trust, immigration attitudes, well-being, and political participation. His work has appeared in journals such as the American Political Science Review, the American Sociological Review, and Nature Human Behaviour. [[email protected]]

Ulf Liebe

Ulf Liebe is Professor of Sociology and Quantitative Methods at the Department of Sociology, University of Warwick. His research interests include discrimination, multifactorial survey experiments, and prosociality. [[email protected]]

References

- Abdelaaty, Lamis, and Liza G. Steele (2022). ‘Explaining Attitudes toward Refugees and Immigrants in Europe’, Political Studies, 70:1, 110–30.

- Abramson, Scott F., Korhan Koçak, and Asya Magazinnik (2022). ‘What Do We Learn about Voter Preferences from Conjoint Experiments?’, American Journal of Political Science, 66:4, 1008–20.

- Adida, Claire L., Adeline Lo, and Melina R. Platas (2019). ‘Americans Preferred Syrian Refugees Who Are Female, English-Speaking, and Christian on the Eve of Donald Trump’s Election’, PLoS One, 14:10, e0222504.

- Allen, Trevor J. (2017). ‘All in the Party Family? Comparing Far Right Voters in Western and Post-Communist Europe’, Party Politics, 23:3, 274–85.

- Alrababa’h, Ala’, Andrea Dillon, Scott Williamson, Jens Hainmueller, Dominik Hangartner, and Jeremy Weinstein (2021). ‘Attitudes toward Migrants in a Highly Impacted Economy: Evidence from the Syrian Refugee Crisis in Jordan’, Comparative Political Studies, 54:1, 33–76.

- Aschauer, Wolfgang, and Jochen Mayerl (2019). ‘The Dynamics of Ethnocentrism in Europe. A Comparison of Enduring and Emerging Determinants of Solidarity towards Immigrants’, European Societies, 21:5, 672–703.

- Bansak, Kirk, Jens Hainmueller, and Dominik Hangartner (2016). ‘How Economic, Humanitarian, and Religious Concerns Shape European Attitudes toward Asylum Seekers’, Science, 354:6309, 217–22.

- Bansak, Kirk, Jens Hainmueller, and Dominik Hangartner (2017). ‘Europeans Support a Proportional Allocation of Asylum Seekers’, Nature Human Behaviour, 1:7, 1–6.

- Bansak, Kirk, Jeremy Ferwerda, Jens Hainmueller, Andrea Dillon, Dominik Hangartner, Duncan Lawrence, and Jeremy Weinstein (2018). ‘Improving Refugee Integration through Data-Driven Algorithmic Assignment’, Science, 359:6373, 325–9.

- Bechtel, Michael M., Kenneth F. Scheve, and Elisabeth van Lieshout (2020). ‘Constant Carbon Pricing Increases Support for Climate Action Compared to Ramping up Costs over Time’, Nature Climate Change, 10:11, 1004–9.

- Berning, Carl C., and Elmar Schlueter (2016). ‘The Dynamics of Radical Right-Wing Populist Party Preferences and Perceived Group Threat: A Comparative Panel Analysis of Three Competing Hypotheses in The Netherlands and Germany’, Social Science Research, 55, 83–93.

- Bloch, Alice, and Liza Schuster (2002). ‘Asylum and Welfare: Contemporary Debates’, Critical Social Policy, 22:3, 393–414.

- Branton, Regina, Erin C. Cassese, Bradford S. Jones, and Chad Westerland (2011). ‘All along the Watchtower: Acculturation Fear, anti-Latino Affect, and Immigration’, The Journal of Politics, 73:3, 664–79.

- Callens, Marie Sophie, and Bart Meuleman (2017). ‘Do Integration Policies Relate to Economic and Cultural Threat Perceptions? A Comparative Study in Europe’, International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 58:5, 367–91.

- Dancygier, Rafaela, Naoki Egami, Amaney Jamal, and Ramona Rischke (2022). ‘Hate Crimes and Gender Imbalances: Fears over Mate Competition and Violence against Refugees’, American Journal of Political Science, 66:2, 501–15.

- Davidov, Eldad, Daniel Seddig, Anastasia Gorodzeisky, Rebeca Raijman, Peter Schmidt, and Moshe Semyonov (2020). ‘Direct and Indirect Predictors of Opposition to Immigration in Europe: Individual Values, Cultural Values, and Symbolic Threat’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46:3, 553–73.

- De Vries, Catherine E., and Erik R. Tillman (2011). ‘European Union Issue Voting in East and West Europe: The Role of Political Context’, Comparative European Politics, 9:1, 1–17.

- Dinesen, Peter Thisted, and Frederik Georg Hjorth (2020). ‘Attitudes toward Immigration: Theories, Settings, and Approaches’, in The Oxford Handbook of Behavioral Political Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1–30.

- Düvell, Franck, and Bill Jordan (2002). ‘Immigration, Asylum and Welfare: The European Context’, Critical Social Policy, 22:3, 498–517.

- Férrin, Mónica, Moreno Mancosu, and Teresa M. Cappiali (2020). ‘Terrorist Attacks and Europeans’ Attitudes towards Immigrants: An Experimental Approach’, European Journal of Political Research, 59:3, 491–516.

- Fietkau, Sebastian, and Kasper M. Hansen (2018). ‘How Perceptions of Immigrants Trigger Feelings of Economic and Cultural Threats in Two Welfare States’, European Union Politics, 19:1, 119–39.

- Fitzgerald, Jennifer, K. Amber Curtis, and Catherine L. Corliss (2012). ‘Anxious Publics: Worries about Crime and Immigration’, Comparative Political Studies, 45:4, 477–506.

- Gelman, Andrew (2019). ‘Don’t Calculate Post-Hoc Power Using Observed Estimate of Effect Size’, Annals of Surgery, 269:1, e9–e10.

- Gianfreda, Stella (2018). ‘Politicization of the Refugee Crisis? A Content Analysis of Parliamentary Debates in Italy, the UK, and the EU’, Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica, 48:1, 85–108.

- Gorodzeisky, Anastasia, and Moshe Semyonov (2020). ‘Perceptions and Misperceptions: Actual Size, Perceived Size and Opposition to Immigration in European Societies’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46:3, 612–30.

- Green, Eva G. T., Oriane Sarrasin, Robert Baur, and Nicole Fasel (2016). ‘From Stigmatized Immigrants to Radical Right Voting: A Multilevel Study on the Role of Threat and Contact’, Political Psychology, 37:4, 465–80.

- Hainmueller, Jens, and Daniel J. Hopkins (2014). ‘Public Attitudes toward Immigration’, Annual Review of Political Science, 17:1, 225–49.

- Hainmueller, Jens, and Daniel J. Hopkins (2015). ‘The Hidden American Immigration Consensus: A Conjoint Analysis of Attitudes toward Immigrants’, American Journal of Political Science, 59:3, 529–48.

- Hainmueller, Jens, Daniel J. Hopkins, and Teppei Yamamoto (2014). ‘Causal Inference in Conjoint Analysis: Understanding Multidimensional Choices via Stated Preference Experiments’, Political Analysis, 22:1, 1–30.

- Hasbún López, Paola, Borja Martinović, Magdalena Bobowik, Xenia Chryssochoou, Aleksandra Cichocka, Andreea Ernst-Vintila, Renata Franc, Éva Fülöp, Djouaria Ghilani, Arshiya Kochar, Pia Lamberty, Giovanna Leone, Laurent Licata, and Iris Žeželj (2019). ‘Support for Collective Action against Refugees: The Role of National, European, and Global Identifications, and Autochthony Beliefs’, European Journal of Social Psychology, 49:7, 1439–55.

- Heizmann, Boris, and Nora Huth (2021). ‘Economic Conditions and Perceptions of Immigrants as an Economic Threat in Europe: Temporal Dynamics and Mediating Processes’, International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 62:1, 56–82.

- Heizmann, Boris, and Conrad Ziller (2019). ‘Who is Willing to Share the Burden? Attitudes towards the Allocation of Asylum Seekers in Comparative Perspective’, Social Forces, 98:3, 1026–51.

- Hopkins, Daniel J. (2010). ‘Politicized Places: Explaining Where and When Immigrants Provoke Local Opposition’, American Political Science Review, 104:1, 40–60.

- Hutter, Swen, and Hanspeter Kriesi (2022). ‘Politicising Immigration in Times of Crisis’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48:2, 341–65.

- Jeannet, Anne Marie, Tobias Heidland, and Martin Ruhs (2021). ‘What Asylum and Refugee Policies Do Europeans Want? Evidence from a Cross-National Conjoint Experiment’, European Union Politics, 22:3, 353–76.

- Kende, Anna, Márton Hadarics, and Zsolt Péter Szabó (2019). ‘Inglorious Glorification and Attachment: National and European Identities as Predictors of Anti- and Pro-Immigrant Attitudes’, The British Journal of Social Psychology, 58:3, 569–90.

- Kolbe, Melanie, and Elif Naz Kayran (2019). ‘The Limits of Skill-Selective Immigration Policies: Welfare States and the Commodification of Labour Immigrants’, Journal of European Social Policy, 29:4, 478–97.

- Kostelka, Filip, and Jan Rovny (2019). ‘It’s Not the Left: Ideology and Protest Participation in Old and New Democracies’, Comparative Political Studies, 52:11, 1677–712.

- Krzyżanowski, Michał (2018). ‘Discursive Shifts in Ethno-Nationalist Politics: On Politicization and Mediatization of the “Refugee Crisis” in Poland’, Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 16:1–2, 76–96.

- Krzyżanowski, Michał, Anna Triandafyllidou, and Ruth Wodak (2018). ‘The Mediatization and the Politicization of the “Refugee Crisis” in Europe’, Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 16:1–2, 1–14.

- Kyliushyk, Ivanna, and Agata Jastrzebowska (2023). ‘Aid Attitudes in Short- and Long-Term Perspectives among Ukrainian Migrants and Poles during the Russian War in 2022’, Frontiers in Sociology, 8, 1–8.

- Leeper, Thomas J., and Rune Slothuus (2014). ‘Political Parties, Motivated Reasoning, and Public Opinion Formation’, Political Psychology, 35:Suppl.1, 129–56.

- Leeper, Thomas J., Sara B. Hobolt, and James Tilley (2020). ‘Measuring Subgroup Preferences in Conjoint Experiments’, Political Analysis, 28:2, 207–21.

- Legewie, Joscha (2013). ‘Terrorist Events and Attitudes toward Immigrants’, American Journal of Sociology, 118:5, 1199–245.

- Lucassen, Geertje, and Marcel Lubbers (2012). ‘Who Fears What? Explaining Far-Right-Wing Preference in Europe by Distinguishing Perceived Cultural and Economic Ethnic Threats’, Comparative Political Studies, 45:5, 547–74.

- Malhotra, Neil, Yotam Margalit, and Cecilia Hyunjung Mo (2013). ‘Economic Explanations for Opposition to Immigration: Distinguishing between Prevalence and Conditional Impact’, American Journal of Political Science, 57:2, 391–410.

- Manevska, Katerina, and Peter Achterberg (2013). ‘Immigration and Perceived Ethnic Threat: Cultural Capital and Economic Explanations’, European Sociological Review, 29:3, 437–49.

- McLaren, Lauren, and Ian Paterson (2020). ‘Generational Change and Attitudes to Immigration’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46:3, 665–82.

- Morales, Laura, Jean Benoit Pilet, and Didier Ruedin (2015). ‘The Gap between Public Preferences and Policies on Immigration: A Comparative Examination of the Effect of Politicisation on Policy Congruence’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41:9, 1495–516.

- Naumann, Elias, Lukas F. Stoetzer, and Giuseppe Pietrantuono (2018). ‘Attitudes towards Highly Skilled and Low-Skilled Immigration in Europe: A Survey Experiment in 15 European Countries’, European Journal of Political Research, 57:4, 1009–30.

- Nicoli, Francesco, Theresa Kuhn, and Brian Burgoon (2020). ‘Collective Identities, European Solidarity: Identification Patterns and Preferences for European Social Insurance’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 58:1, 76–95.

- Nielsen, Mathias Herup, Morten Frederiksen, and Christian Albrekt Larsen (2020). ‘Deservingness Put into Practice: Constructing the (Un)Deservingness of Migrants in Four European Countries’, The British Journal of Sociology, 71:1, 112–26.

- Onraet, Emma, Alain Van Hiel, Barbara Valcke, and Jasper Van Assche (2021). ‘Reactions towards Asylum Seekers in The Netherlands: Associations with Right-Wing Ideological Attitudes, Threat and Perceptions of Asylum Seekers as Legitimate and Economic’, Journal of Refugee Studies, 34:2, 1695–712.

- Schultz, Caroline, Philipp Lutz, and Stephan Simon (2021). ‘Explaining the Immigration Policy Mix: Countries’ Relative Openness to Asylum and Labour Migration’, European Journal of Political Research, 60:4, 763–84.

- Thravalou, Elisavet, Borja Martinovic, and Maykel Verkuyten (2021). ‘Humanitarian Assistance and Permanent Settlement of Asylum Seekers in Greece: The Role of Sympathy, Perceived Threat, and Perceived Contribution’, International Migration Review, 55:2, 547–73.

- Triandafyllidou, Anna (2018). ‘A “Refugee Crisis” Unfolding: “Real” Events and Their Interpretation in Media and Political Debates’, Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 16:1–2, 198–216.

- Valentino, Nicholas A., Vincent L. Hutchings, and Ismail K. White (2002). ‘How Political Ads Prime Racial Attitudes’, American Political Science Review, 96:1, 75–90.

- Van Hootegem, Arno, Bart Meuleman, and Koen Abts (2020). ‘Attitudes toward Asylum Policy in a Divided Europe: Diverging Contexts, Diverging Attitudes?’, Frontiers in Sociology, 5, 35.

- Vranceanu, Alina, Elias Dinas, Tobias Heidland, and Martin Ruhs (2022). ‘The European Refugee Crisis and Public Support for the Externalisation of Migration Management’, European Journal of Political Research.

- Weiss, Akiva, and Marina Tulin (2021). ‘Does Mentoring Make Immigrants More Desirable? A Conjoint Analysis’, Migration Studies, 9:3, 808–29.