Abstract

Residence-by-investment schemes, which enable wealthy people to acquire a visa in return for a financial investment, have become increasingly common. In this article, an original immigration policy index and case studies are used to examine the political economy of residence-by-investment policies in three European countries: France, Spain, and the UK. Two contributions are made to the literature. First, the article compares investment with work visas and shows that across all three countries investor routes are significantly more open and generous than work routes, including for the highly skilled. Second, drawing on theories of comparative political economy, it is explored how investor visas are shaped by capitalist diversity. Based on these three cases, it is argued that investor visa policies are conditioned by national-level economic models and the political interests that underpin them. The article aims to advance understanding not only of how investor visas vary, but why they do so.

One of the more controversial migration policy developments in recent years has been the trend for European countries to adopt citizenship- and residence-by-investment schemes, sometimes known as ‘golden passports’ and ‘golden visas’ respectively. These schemes allow wealthy individuals and their families to acquire citizenship or permanent residence in return for a substantial financial investment. In 2010, just four European Union (EU) Member States offered investor visa programmes; by 2017, nearly half had an investor visa, and all had adopted at least one legal mechanism for facilitating investment-based migration (Džankić Citation2018: 479; Surak Citation2022: 151).

Recent scholarship on residence-by-investment schemes has described investor visa policies, mapped cross-national variation, examined policy drivers, and explored normative questions (e.g. Džankić Citation2015, Citation2018; Gamlen et al. Citation2019; Kochenov and Surak Citation2023; Parker Citation2017; Sumption Citation2021; Surak Citation2022; Surak and Tsuzuki Citation2021). Considerable progress has been made in understanding how and why investment migration has taken off in recent years. However, there is little research that analyses investor policies in relation to other migration policies or situates investment migration within national economic models. In this article we compare investor and work migration policies to shed light on how access to European residence is differentiated by wealth and labour; and by analysing investor visas within the context of national models of political economy, we explore factors that shape investor visa policies.

Our analysis is based on an original policy index, which we use to compare immigration policies for investors and skilled workers across three European countries – France, Spain, and the UK – alongside qualitative case studies, through which we explore how national-level factors influenced the introduction and goals of investor visas. We address three research questions: first, have investor visas become more open over time; second, how do investor routes compare to work routes; and finally, what factors explain variation in investor visa policies across countries?

We show that there has been a general liberalisation of investor routes and that admission to all three countries is significantly easier for the wealthy than skilled workers. Admissions criteria are less stringent, and rights are more expansive, for those who can afford to make financial investments compared with those who bring scarce skills or fill job vacancies. While there has been an overall liberalisation of investor routes, there is considerable variation in the kinds of investments targeted by different countries. We argue that investor visas are embedded in different national growth models (Baccaro and Pontusson Citation2022; Baccaro et al. Citation2022) and shaped by political elites’ ideas about how to generate growth. Building on comparative political economy scholarship on migration policies and capitalist diversity (Afonso and Devitt Citation2016; Consterdine and Hampshire Citation2020; Caviedes Citation2010; Freeman Citation2006; Menz Citation2008) our contribution is intended as a theory-building exercise to help explain cross-national differences in residence-by-investment policies.

Investor visas and migration management

Immigration policies in Europe have become highly selective and stratified (Lutz Citation2019). Relatively small numbers of economic migrants are enticed with generous admissions criteria and rights, while others are admitted on a temporary basis, or excluded altogether. As Christian Joppke neatly puts it, European and other rich countries are ‘courting the top, [while] fending-off the bottom’ (2021: 68). States seek to attract high-skilled migrants – the ‘brightest and best’ as they are often described – by relaxing entry requirements and offering fast-tracked routes to settlement; whereas migrants in low-wage sectors are typically recruited through temporary labour programmes without a route to settlement (Boucher and Cerna Citation2014; Ruhs Citation2013).

Alongside skill-based work migration policies, many states have developed investment-based policies to attract the global super-rich. The most generous of these schemes are arguably not migration policies at all, insofar as they do not require visa holders to reside in the country that issues them (and in practice many of their recipients do not migrate). These ‘golden passport’ schemes grant citizenship in return for a substantial financial investment. In Europe, Cyprus and Malta offer citizenship-by-investment programmes.

More widespread are investor visa programmes, which provide legal residence for an extended period (often with a route to naturalization) in return for a financial investment. Investor visas have proliferated since the 2008 financial crisis (Džankić Citation2018: 479). In Europe, about one-third of residence-by-investment programmes predate the Eurozone crisis, but fully two-thirds were launched since then (Surak Citation2022: 8). Since 2008, more than 165,000 persons have acquired investor visas in the United States, Canada, EU countries, and the UK (Harpaz Citation2022: 556). One study identified 60 different schemes operating across 57 countries by 2019 (Gamlen et al. Citation2019).

Insofar as they retain a link between residence and rights, investor visas are less controversial than citizenship-by-investment schemes, but they nevertheless represent a commercialisation of membership (Parker Citation2017) and raise similar legal concerns. For example, the European Commission has criticised investor visas on the grounds that they may enable money laundering and tax evasion (European Commission Citation2019a). Furthermore, in the EU when one member state sells residence to a third country national it has clear implications for other states: as the European Commission observes, ‘a valid residence permit grants certain rights to third-country nationals to travel freely in particular in the Schengen Area’ (European Commission Citation2019a: 1). A 2014 Resolution of the European Parliament claimed that states involved in the ‘direct or indirect sale of European Citizenship’ are undermining ‘the mutual trust upon which the Union is built’ (European Parliament Citation2014) [emphasis added].

The growing literature on investor visas has examined the different types of programmes (Džankić Citation2015; Sumption Citation2021); the size of the required investment (Džankić Citation2018); states’ aims in developing investor visa schemes (Gamlen et al. Citation2019); and the origins and development of the schemes over time (Džankić Citation2018; Surak Citation2022; Surak and Tsuzuki Citation2021). This research shows that investor visa schemes have diverse aims – some are focused on raising revenue (whether for government or the private sector); others expect investors to contribute to the economy in some form, for example setting up a business; some have more extensive residence requirements for visa-holders than others. There is also considerable variation in terms of the size and type of the investment, which can range from under €100,000 to over €5 million. The type of investment may involve purchase of Government bonds, a direct transfer to the state budget, capital investment, investment in immovable property, or a donation to an activity defined as contributing to the public good. Džankić (Citation2018) argues that the choice of investment reflects the size of a country’s economy: small island states tend to opt for a direct transfer to government coffers; larger economies tend to favour private sector investments or purchase of government bonds. In the largest comparative evaluation of investor schemes, Surak and Tsuzuki (Citation2021) show that governments are more likely to begin resident investor programmes after a decline in economic growth and that the programmes are often targeted to address failing areas of the economy.

Several typologies have been proposed to make sense of investor visas. Sumption (Citation2021) categorises them into four groups based on the type of investment involved: non-refundable cash payments to the government or non-governmental ‘worthy causes’; investment in private businesses; residential property investment; and ‘display of wealth’ programmes (in which applicants must show that they have funds, but do not have to make a productive investment). Džankić (Citation2018) analyses immigrant investor programmes on two dimensions: the investment obligation (the amount of investment) and status obligation (obligations to maintain residence rights). She concludes that the objective of programmes which require high investment thresholds and little to no physical presence is a short-term inflow of funds, whereas programmes that exchange ordinary residence rights for investment tend to ‘target migrants who will offer continuous input in the respective country’s economic and politics’ (Džankić Citation2018: 77). As we discuss below, there is considerable variation over what kind of ‘input’ is sought by governments.

The existing literature provides important insights into governments’ aims in encouraging investment migration. With few exceptions, however, investor visas have tended to be analysed in isolation, rather than as part of wider migration policy regimes. Furthermore, there has been no systematic application of a comparative political economy framework to the analysis of investor programmes. As a result, we do not have much understanding of how investment-based migration policies relate to other types of migration, notably the degree to which investors are prioritised over workers, and how investment migration is influenced by (or insulated from) the political economic factors that shape migration policies.

Political economy research on immigration policy argues that organised interest groups, especially employers and employer associations, play an important role in immigration policymaking. In an early (and widely critiqued) formulation Freeman (Citation1995) argued that the influence of pro-immigration ‘clients’ created an ‘expansionary bias’ in the immigration policies of liberal democracies; more recent work has examined how the institutional arrangements of different varieties of capitalism affect the policy preferences of governments, employers, and unions, and their influence on immigration policy outputs (Afonso and Devitt Citation2016; Boräng and Cerna Citation2019; Caviedes Citation2010; Consterdine and Hampshire Citation2020; Devitt Citation2011; Menz Citation2008).

We argue that investor regimes are, like work migration, shaped by national economic models. However, compared to work migration, we contend that investor migration policy is less influenced by the demands of employers and employer organisations (who mainly mobilise on labour migration) and less affected by anti-immigrant mobilisation, which tends to focus on larger and more visible migration flows, including authorised labour migrants and especially asylum-seekers and irregular migrants. The smaller scale of investor migration and its negligible impact on labour markets means that the dynamic familiar in labour migration policymaking, where the ‘quiet politics’ (Culpepper Citation2010) of business power interacts with the loud politics of popular mobilisation, is largely absent. Economic interests that directly benefit from investor visa schemes, such as wealth management firms and global visa agencies, are not insignificant, but they have less structural power than large companies whose operations are integral to economic growth.

Rather than interest group lobbying, the influence of national economic models on investor visas flows through policymaking elites’ ideas about the kinds of investment that will stimulate growth, conditioned by the prevailing ‘growth model’ (Baccaro et al. Citation2022) and sectoral composition of the national economy. While the widespread adoption of investor visas in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis was driven by a common attempt to stimulate growth, the objectives and design of investor policies reflect elites’ ideas about the kinds of investment conducive to their nation’s growth model and its dominant sectors. As we discuss in the case studies, the UK investor visa was designed to enable flows of capital into London’s financial services and property market; the French visa was integral to Presidents Sarkozy and Macron’s projects of economic liberalisation; while the Spanish visa was underpinned by a bipartisan conviction to rescue a collapsed property market and construction sector.

The relative degree of autonomy enjoyed by governments over investor visas helps to explain their rapid adoption as well as the abrupt closure of the UK scheme. As we discuss in the conclusion, allegations of corruption, shifting geopolitics (especially European relations with Russia and China), and wider de-globalisation have undermined an elite consensus that selling visas to the rich is an unalloyed good.

Methodology

We analyse investor visa policies alongside policies that regulate the entry of migrant workers. This comparison enables a more nuanced understanding of the kinds of migration that states actively seek to encourage. We therefore go beyond a binary distinction between ‘wanted’ and ‘unwanted’ migration – i.e. between migrants that states actively solicit and those that they at best tolerate and often try to prevent, such as family migrants and asylum seekers (see Joppke Citation2021). In stratified migration management systems, even among the relatively few ‘wanted’ migrants there are degrees of openness and, as we show below, the relative openness towards different migrants varies considerably across Western European countries. By examining how eligibility criteria and residency rights compare between investor routes and the routes for workers we show that there is a hierarchy among ‘wanted’ migrants, in which the wealthy are placed above the skilled and even highly skilled.

We analyse three Western European countries: France, Spain, and the United Kingdom. These countries are selected as large economies encompassing different varieties of capitalism. The three countries encompass three of the four categories described in Sumption’s (Citation2021) typology. We first compare policies across these three countries, then, using case studies, we explore national-level factors that influenced the introduction and design of each country’s investor visa. We explore how differences in the sectoral composition and drivers of economic growth help explain variation in the trajectories and the kinds of investment targeted by each country’s scheme.

The first stage of our analysis is based on an original immigration policy index (ImPol), which we use to measure the restrictiveness of immigration policies during the period 1990-2016. ImPol enables analysis of cross-national variations between countries and comparison of the relative restrictiveness of different routes within countries: for example, between investor, high-skilled, and skilled work routes. This approach distinguishes ImPol from other immigration policy indexes such as IMPIC (Helbling et al. Citation2017), IMPALA (Beine et al. Citation2016), DEMIG (De Haas et al. Citation2018) and Ruhs’ labour migration index (2018). In a small n study such as this, we cannot draw generalisable conclusions; rather we use the ImPol index to trace policy changes over time and systemically compare policies across the three countries and between the various routes within countries. We then examine the qualitative detail of how and why investor visa policies vary in the case studies.

ImPol measures restrictiveness using a total of 24 indicators: 12 for entry criteria, and 12 for rights attached to admission. Indicators for entry criteria measure the requirements for a given route, such as qualifications, work experience, and language proficiency. Examples of rights-based indicators include whether the visa applicant can bring dependants, the length of residency permitted, and whether there is a route to permanency. Each indicator is measured using an ordinal scale, with three potential values: restrictive (-1), neutral (0), and open (1). The codebook sets thresholds for coding decisions using objective criteria. For example, if a language requirement is set at B1 or above on the Common European Framework of References for Language then the route is coded as −1, a requirement at a lower level is coded 0, whereas no language requirement is coded 1. This approach to thresholds means that ImPol captures changes in restrictiveness over time for a given country and enables systematic comparison across countries. Drawing on and referencing policy documents and legislation, for a given entry route each indicator is coded for each year in the time series. Scores are averaged with equal weighting for each indicator. Space constraints preclude further discussion of the methodology and coding scheme.Footnote1

Migration policies are highly, and increasingly, differentiated, and their structure varies across national policy regimes. In most countries, there is not a single route or set of criteria for economic migrants, but multiple visas, each with different entry criteria and conditions attached to admission. This creates significant challenges for consistent and reliable measurement, especially across countries and time. In our analysis below we compare ‘investor’ routes with, ‘high-skilled’ and ‘general’ work routes. These categories sometimes, but not always, map onto dedicated visas.

We follow Sumption’s definition of investor programmes as ‘policies in which the government awards residence status […] to individuals and/or family members in return for a financial transaction, with relatively limited requirements to be actively involved’ (2021: 4). For coding purposes, investor programmes are comparatively straightforward to measure, as there is usually either a dedicated investor visa or no route. The same cannot be said for work routes. For example, not all countries operate a visa for ‘high-skilled’ workers distinct from other work visas, yet there will usually be an entry route for those who are high-skilled. Even within a given country it is not always possible to track a single visa, since categories are created, amalgamated, and abolished over time. To overcome this problem, we measure work-related migration policies using selected occupations at different skill levels as defined by the International Labour Organization’s International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-08).Footnote2

One caveat to note is that the ImPol scores for investor visas do not include the monetary amount of investment thresholds. There are two reasons for this: firstly, to enable comparison with non-investment routes it is necessary to measure only generic criteria (i.e. criteria that apply across different types of entry route); secondly, as each indicator is measured using an ordinal scale with three values, the measurement of monetary amounts would have significant (and arbitrary) cliff-edge effects on the results, depending on where thresholds were set. Since the cost of investment is clearly an important eligibility criterion for investor visas – for most people it will be the most significant barrier to applying for such a visa – it should be considered when comparing schemes across countries. We address this in our case studies and the discussion that follows.

The case studies allow us to analyse the specificities of each country’s investor migration policies and situate them in political and economic context. Quantitative indexes such as ImPol allow the systematic comparison of policies within and across countries, but they cannot capture all the nuances of variation in policy. In the three case studies, we examine the specificities of each investor scheme, for example the kinds of investors or sectors that each country’s policy seeks to encourage, then consider how national political economy influenced the timing and design of the investor visas.

Comparing investor visas in Western Europe

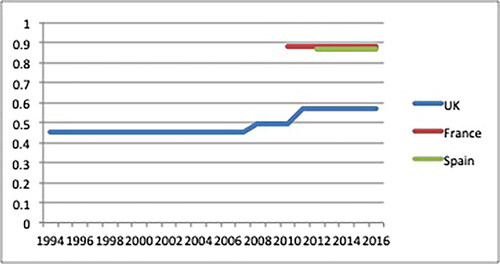

The wider trend towards residence-by-investment schemes can be seen in France, Spain and the UK. All three adopted an investor visa during the period 1990-2016. gives details of the three schemes, while shows the ImPol scores for investor visas over time (higher scores indicate a more open and lower scores a more restrictive policy).Footnote3 The UK operated a route for investors from 1994 to 2022, while France and Spain introduced their schemes in 2009 and 2013 respectively, part of the ‘second wave’ of investor visas following the Eurozone crisis. The creation of two schemes, and the liberalisation of the UK scheme, in the years after the 2008 financial crisis illustrates that these countries became more open to investment migration in the last decade or so.

Table 1. Summary of investor visas in UK, France and Spain.

While all three countries introduced investor visas during the period under analysis, the timing and degree of openness vary considerably. To examine this variation and compare investor routes in relation to work routes, we present a series of in-country analyses. For each country we present the ImPol data on investor, high-skilled and skilled work routes, and a case study which examines qualitative details of policies and their drivers. We begin with the UK, one of the first European countries to introduce an investor visa (and, recently, the first to close its scheme).

The United Kingdom: loosening investment, tightening work

The UK operates one of the oldest investor schemes in Europe. It was the first EU Member State to introduce an investor visa in 1994 (Surak Citation2022: 7). To obtain an investor visa in 1994, applicants needed £1 million in disposable cash and were required to invest no less than £750,000 in government bonds, share capital or loan capital in active and trading UK registered companies. In 2008, the UK’s investor route was placed in the new ‘Tier 1′ of the new Point Based System (PBS), as part of the Labour Government’s wider liberalisation of economic migration, which included the creation of a new high-skilled work visa (Consterdine Citation2018; Consterdine and Hampshire Citation2014; Wright Citation2012). The Home Office announcement that a scheme ‘for those who have substantial funds to invest in the UK’ (Home Office Citation2006: 24) would be included in the PBS drew no opposition from the Conservatives (unsurprisingly, given it was the previous Conservative Government that had introduced an investor route). Both the investor and the new high-skilled visas were a good ideological fit with New Labour’s embrace of globalisation, its commitment to attract the ‘brightest and best’ to the UK, and its support for financial services and associated industries in the City of London.

Applicants for a Tier 1 (Investor) visa were required to invest a minimum of £1 million in the UK, a sum increased to £2 million after 2015. In return, applicants were issued with a visa for three years, renewable for a further two years, at the end of which they could apply for permanent residency. In 2011, the government introduced provisions for accelerated settlement, under which applicants who invested more money gained faster access to permanent residence: in return for a £5 million investment, the residency requirement was reduced to three years, and for £10 million, to just two years.

The UK was a ‘passive’ investment scheme: applicants did not have to establish a business or create any jobs in the UK, nor was the investment targeted at a specific sector or region. Applicants usually made their investment in UK gilts, effectively loaning the UK government money for the duration of their visa. The Tier 1 Investor Visa was a no-strings-attached form of residence-by-investment: admission was granted in return for a loan to government and, unlike most other visas, applicants did not have to satisfy any English language requirements.

The passive design of the scheme was a striking – and would later become a controversial – feature of the UK’s approach to investor migration. Without any requirement to invest in business or to direct funds to a particular region or sector of the economy, the UK investor visa enabled very wealthy people to establish themselves in the UK with few strings attached. One of the few demanding requirements of the UK visa was its comparatively stringent physical presence requirements. From 1994 until 2011, the visa-holder had to make the UK their main home, with only short absences permitted: no more than three months at a time and a total of no more than six months over the five years. After 2011, this was relaxed so that investors could be absent from the UK for up to 180 days per year (MAC Citation2014: 12; Sumption and Hooper Citation2014: 16). Yet even these revised conditions were more demanding than other residence-by-investment programmes in the EU, which generally have lower requirements to spend time in the country. The UK scheme was therefore unsuitable for wealthy people seeking to acquire an EU passport while remaining domiciled in their country of origin.

Between 2008 and 2019, a total of 4,211 investor visas were issued (Surak Citation2022: 159), making the UK investor route one of the most popular in Europe. The most common nationalities issued with a Tier 1 Investor visa were China (33%), Russia (18%), and USA (6%).Footnote4 The annual numbers were small at first, but grew steadily, peaking in 2014 at 1,172. The scheme was successful in terms of the number of applicants it attracted, but critics soon began to claim that it was enabling flows of illicit and corrupt money into the UK. Transparency International described the time between 2008 and 2015 as ‘the blind faith period’, concluding that there was ‘a reasonable basis for concern that the UK’s Tier 1 Investor programme has attracted corrupt Russian and Chinese high net worth individuals (Transparency International 2015: 6). In response, in 2015 the government doubled the investment threshold and introduced a requirement to establish a UK bank account to reduce the risk of money laundering.

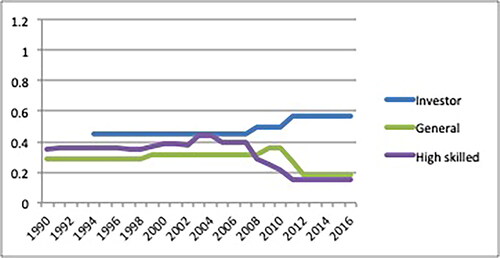

The UK’s investment route was consistently more open than its work migration routes – both the high-skilled route and ‘general’ work permits for migrants with a job offer (Tier 2 of the PBS). Unlike work migrants, applicants for the investor visa did not need to meet language requirements (it was one of the only visas exempt from language proficiency requirements) nor did they have to demonstrate a specified level of qualifications or experience. Moreover, investor visa-holders’ residency rights were more generous, including a longer leave period of three years (compared to two years under most work routes), flexibility to transition to any other visa, and a facilitated pathway to settlement, through which it was possible to acquire indefinite leave to remain after two years of continuous residence compared to five years for the Tier 2 general work route.

shows a considerable and growing divergence between investment and work migration routes from 2010 onwards, so that by 2016 the discrepancy between investment and work was the largest of any of the countries we analysed. While the UK’s investor route scores lower than either France or Spain, by 2016 the gap between investment and work routes (about 0.4 on the ImPol scale, or 20% of total possible variance) was much higher in the UK than elsewhere. Relative to overall immigration policy, then, investment migration enjoyed an especially privileged position in the UK.

The investment routes bucked the overall restrictive immigration policy trend from 2010 onwards. After committing to reduce net migration, the Conservative-led Coalition Government tightened work as well as family and student routes, while the investor scheme was liberalised. As the total number of investor visas was small compared to work, study, and family routes, investment migration had a negligible impact on the overall volume of migration to the UK, so it was not a route that had much effect on the net migration target. Nevertheless, at a time when UK policies for most other kinds of immigration – not only workers, but also international students and family migrants – were being tightened, the investor route became more open.

The UK closed its investor scheme in early 2022. Two factors converged to produce this outcome: growing scepticism among government officials that the investors had significant economic benefits for the UK; and concerns that the route was being used to launder money. Doubts about its economic benefits were publicly voiced in 2014 by the government’s own Migration Advisory Committee (MAC), in a report analysing the economic impacts of the Tier 1 (Investor) route. The MAC concluded that ‘we are sceptical that the route, as currently constituted, does deliver significant economic benefits’ (MAC Citation2014: 89). The MAC acknowledged that there may be other benefits, such as signalling openness of the UK to ‘high net worth individuals’, and it did not advocate closure, but recommended reforms including raising the minimum investment threshold to £2 million.Footnote5 The overall tone of the report was undoubtedly sceptical, and coming from the government’s own advisory committee, it put the economic case for the visa on shaky ground.

While the MAC report had thrown doubt on the economic benefits of the Tier 1 Investor visa, there were separate concerns – outside the committee’s purview – that the scheme was open to abuse by wealthy individuals with questionable motives and backgrounds. As media scrutiny of money flows through the ‘London laundromat’ intensified, and as allegations of Russian interference in politics mounted after the Brexit referendum, a Home Office audit of the investor visa scheme was begun in 2018. In July 2020, a report by the Intelligence and Security Committee of the House of Commons on Russian influence in the UK expressed concern that Britain had been ‘welcoming oligarchs with open arms’ and that ‘Londongrad’ had become the city of choice for both money and reputation laundering. The Committee found that ‘exploitation’ of the Tier 1 Investor visa was ‘the key to London’s appeal’ (Intelligence and Security Committee 2020: 15).

As pressure built on the government to cut ties with Russia in the build-up to the invasion of Ukraine, the then Home Secretary, Priti Patel, announced the closure of the investor route with immediate effect in February 2022, claiming that it ‘had failed to deliver for the UK people and gave opportunities for corrupt elites to enter the UK’ (quoted in BBC Citation2022). In a written statement made on 12 January 2023, the new Home Secretary, Suella Braverman, reported that a review of the investor route had identified ‘a small minority of individuals connected to the Tier 1 (Investor) visa route that were potentially at high risk of having obtained wealth through either corruption or other illicit financial activity, and/or being engaged in serious and organised crime’. In language unthinkable a few years earlier, the Home Secretary stated that ‘kleptocracies such as Russia’, should not be able to ‘act with impunity overseas’. Any future scheme would not be based on passive investment and ‘must not offer entry solely on the basis of the applicant’s personal wealth’ (House of Commons Citation2023).

‘Entrepreneur is the new France’: investors as agents of economic liberalisation

The French residence-by-investment scheme has, thus far, escaped the kind of political controversy seen in the UK. The first investor visa was introduced in 2008 during the wave of wealth-based immigration programmes following the financial crisis. The Exceptional Economic Contribution (EEC) Residence Permit was a business investment programme, with applicants required to invest a minimum of €10 million in fixed assets in the private sector or to create or ‘protect’ at least 50 jobs in France. Direct investments included share capital investments, reinvested earnings or ‘loans between affiliated companies’ (European Commission Citation2019b: 2); exclusively financial investments were outside the scope of the scheme. EEC permit holders were granted 10 years’ residency, which was renewable subject to continuing to meet the investment conditions. Permit holders were eligible for permanent residency after five years. Family dependants could accompany the permit holder and had unrestricted access to the labour market.

The EEC permit was at first spectacularly unsuccessful, with a total of just nine applications between 2010 and 2013, likely due to the high level of required investment (Sumption and Hooper Citation2014: 19). In 2017, the EEC permit was replaced with the Business Investor permit, with a much lower investment threshold of €300,000. The new scheme was part of a set of initiatives variously dubbed as ‘French Tech’ or ‘Talent Passports’, designed to encourage skilled professionals and entrepreneurs to migrate to France. While the investment threshold was reduced, the Business Investor permit has broadly the same eligibility criteria as the previous EEC permit and carries the same residency rights. The effect on applications was, however, modest: only 29 residence permits were issued to investors in 2017, generating about €9 million of inward investment (European Commission Citation2019b).

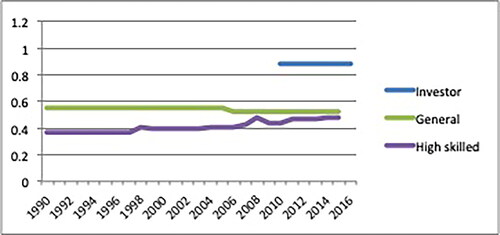

Yet France’s investor route is the most generous of our three cases (see ), particularly in terms of in-country rights. The permit did not require continuous physical residence and allowed holders to leave and return to France without having to re-apply for a permit.Footnote6 Éric Besson, then Minister of Immigration, boasted that rather than the standard one-year renewable leave attached to all other residence permits, the EEC permit granted an unprecedented 10-year residency card (Besson Citation2009). Unlike the ordinary work route, there were also no language requirements and no requirements to demonstrate experience or qualifications. As shows, France’s investor visa is considerably more generous than its high-skilled and skilled work routes.

What explains this openness in comparison to labour migration routes? And what explains the combination of a high investment threshold, with the comparatively liberal eligibility criteria and generous in-country rights which lie behind the high ImPol score? We argue that a mix of protectionism and liberalism embodied in the EEC permit is rooted in a particular juncture of French political economy; specifically, its ‘post-dirigiste’ moment, in which capitalist restructuring and liberalisation co-existed with longer traditions of state intervention (Clift and McDaniel Citation2021: 6). While the politics of immigration in France has ensured that labour migration policy remains relatively restrictive, the comparative openness of the investor programme, as well as its combination of a high investment threshold with liberal eligibility criteria and rights, reflects Presidents Sarkozy and Macron’s projects of economic liberalisation.

Throughout the post-war period, successive French administrations adopted a dirigiste approach to economic management, distinguished by high levels of state intervention. In the early 1980s, a combination of international and domestic factors led the newly elected Left government to implement far-reaching liberalising reforms, in what became known as the 1983 U-turn. This neoliberal turn was, however, ‘reluctant, hidden and half-hearted’ (Levy Citation2017: 608). France did not decisively break with its statist model, as evidenced by the increase in state spending on social and labour market programmes, the maintenance of high employment protection, and continued rescues of failing enterprises. Levy (Citation2008) describes this as ‘social anaesthesia’ strategy, whereby state authorities pacified and demobilised potential opponents of economic liberalisation through increased spending. Since then, the French approach to economic management has combined state intervention and protectionism with partial liberalisation.

While the 2008 financial crisis seemed an opportune moment for a return to dirigisme – and the Sarkozy administration did indeed bail out auto industries and established a sovereign wealth fund to support French companies − the government did not commit additional resources to industrial policy and did little to direct business strategies. Sarkozy was elected on a campaign of change, vowing to ‘break with the ideas, the habits and the behaviour of the past’ (Sarkozy quoted in the Sciolino Citation2007). He blamed France’s social model for generating high rates of unemployment and advocated a neoliberal economic model as the solution to economic stagnation. Sarkozy’s business-friendly proposals, including new tax breaks and limits on trade union powers, would, in his own words, administer ‘an economic and fiscal shock so that France sets out to capture this point of growth which it lacks’ (quoted in LeParmentier Citation2007). As a result, by 2010 the state was heading towards a more liberal model of capitalism, notably in the financial sector (Clift and McDaniel Citation2021; Levy Citation2017).

As part of this liberalisation strategy, France introduced a policy to attract technology entrepreneurs and businesses, in a programme called ‘la French Tech’.Footnote7 The creation of an investor route in 2009 was a core part of this package. As Éric Besson, then Minister of Immigration, put it, the aim was to ‘bring dynamism and innovation to our economy’ by ‘ensuring those who wish to invest benefit from a 10-year residency permit’ (Besson Citation2009). For the first time in France’s history, the criterion for issuing a residence permit was ‘directly and explicitly linked to the economic contribution made to our country’ (Besson Citation2009). Thus, the investor scheme was intended to facilitate foreign investment and internationalise the French economy. Besson spoke of a ‘Golden residence permit’ that was ‘meant to attract foreign investors, entrepreneurs, talents from overseas’.’ ‘We are now’ he claimed, ‘at a time of global competition to seduce the best’ (Besson quoted in Gabizon Citation2009). This discursive shift persisted under President Macron, who has continued to promote La French Tech, claiming: ‘I want France to attract new entrepreneurs, new researchers, and be the nation for innovation and start-ups… I will ensure that we create a most attractive and creative environment, I will ensure that the state and government acts as a platform not a constraint… Entrepreneur is the new France’ (quoted in Kharpal Citation2017).

Despite Sarkozy and Macron’s neoliberalism, French authorities still aspired to shape how French capitalism and corporate governance evolves, an approach Clift and McDaniel (Citation2021: 6) describe as post-dirigiste. The EEC permit’s mix of protectionist characteristics (a high investment threshold and stipulation to protect French jobs) combined with a generous rights package arguably exemplifies post-dirigisme, where the state operates ‘with the grain of the market, albeit a French conception of market, comfortable with permissive interventionism and selective liberalisation seeking to bolster international champions’ (Clift and McDaniel Citation2021: 8).

Spain: reflating the property market

The Spanish government introduced an investor visa in the 2013 law to Support Entrepreneurs and their Internationalisation,Footnote8 which was passed in response to the economic crisis engulfing the country after 2008. The investor visa has two main channels: real estate and capital investment. Applicants must make either a €500,000 investment in property or a ‘significant capital investment’ in Spain of €1 million in either bank deposits or shares. Investor visas can also be granted to applicants with business projects that are assessed by the Spanish Government to create jobs, impact a specific geographical area, or contribute to scientific or technological innovation.

Real estate investment is by far the most significant option in terms of both applications and amounts invested. Between 2014 and 2019, there were 6,064 applications for the investor visa (Surak and Tsuzuki Citation2021: 7), with the vast majority being issued for real estate: 94 per cent of all investor visas in Spain between 2013 and 2017 were through the real estate route, amounting to a total of €2.3 billion in property purchases (Surak and Tsuzuki Citation2021: 16). A total of 531 visas were issued in the first year alone, generating €446 million (European Commission Citation2019c). The popularity of Spain’s scheme has driven a wider surge in real estate investment visas, which now account for the majority of investor visa applications in the EU (Surak and Tsuzuki Citation2021: 16). According to the European Commission, the scheme ‘established a favourable framework for internationalisation of the Spanish market’ and ‘boost[ed] opportunities in the negotiation of international economic agreements’ (European Commission Citation2019c).

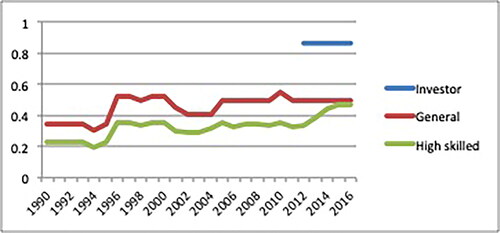

As shown in , the investor visa is considerably more open than Spain’s work routes: applicants for the investor visa do not need to meet language requirements or demonstrate a specified level of qualifications or experience; unlike most work routes, family dependents of the investor are granted unrestricted access to the labour market; and in contrast to the general one-year residency permit, the investor visa grants residence for two years, with facilitated eligibility for permanent residence after five years. Visa holders can renew their temporary permits without being physically present in Spain, but the visa requires that investors live in Spain for the majority of a five-year period in order to apply for permanent residence (Sumption and Hooper Citation2014: 16). Family dependents can accompany the main applicant.

Spain’s investor visa scores about the same as France on the ImPol measurement (see ). Once the relatively low investment threshold is taken into account, the Spanish investor route can be considered more open than France’s scheme. With a threshold of €500,000 for property, it has comfortably the lowest investment threshold of the three countries.

The investor visa was part of a wider shift in Spanish immigration policy towards an approach based on economic and labour market needs (Balch Citation2010: 1039), as the Zapatero and then Rajoy governments attempted to harness migration for economic recovery. The introduction of the visa followed the 2011 protocol ‘Invest in Spain’, an agreement signed by the State of Secretary for Immigration and Emigration, Ana Terón, and the State Secretary for Foreign Trade, Alfredo Bonet, to ‘promote and attract foreign investment’ by ‘cutting through red tape’ (La Moncloa Citation2011). High-skilled routes were liberalised in 2012 and the investor visa scheme followed the year after. The preamble to the Law to Support Entrepreneurs and their Internationalisation explicitly referenced the ‘profound economic crisis that Spain has been suffering, with acute social consequences’ (Law 14/2013), as a reason for introducing the investor visa.

In order to understand why the Spanish scheme focused on property investment, it is necessary to situate it within Spain’s growth model, in which construction and property play an outsized role compared to many other European countries. This model has its origins in the modernisation programme of the Franco dictatorship in the late 1950s, which was premised on the development of mass-market tourism and the expansion of private home ownership. As López and Rodríguez (Citation2011: 6) note, ‘this Thatcherism avant la lettre transformed the Spanish housing market’. The election of a socialist government in 1982 did not result in a change of course. In fact, under Prime Minister Felipe Gonzalez, Spain’s economic reliance on tourism, property development, and construction deepened (López and Rodríguez Citation2011: 7). Expansion of the construction sector was fuelled by the Land Act of 1990, colloquially known as the ‘build anywhere’ law, which increased the scope of local governments to urbanise, and then by 1998 reforms passed by the Aznar government, which loosened procedures for building permits and significantly increased the stock of land available for construction (Baccaro and Bulfone Citation2022: 311). In the decade preceding the Eurozone crisis, domestic demand grew from 22 per cent of GDP in 1995 to 30 per cent in 2006, largely due to construction investment, which increased from 14 per cent to 21 per cent of GDP.

The construction boom was to a large extent driven by immigration, as record numbers of migrants from Latin America and Eastern Europe, and the purchase of homes by foreign nationals, fuelled demand (Baccaro and Bulfone Citation2022: 311). Spanish house prices more than tripled between the early 1990s and the mid-2000s, and housing stock expanded by 30 per cent (López and Rodríguez Citation2011), while household debt doubled as a percentage of disposable income. As Baccaro and Pontusson (Citation2022: 214) put it, ‘all the elements of a debt-driven construction boom’ were present. And indeed, after the Eurozone crisis came a housing crash: the market collapsed, and property prices fell by 42 per cent.

The investor visa was one of several policies designed to reflate the property market. The Spanish scheme, with a much lower investment threshold reserved for those who invest in property, was an explicit attempt to inject cash into the construction sector, in the hope of stimulating a domestic demand-led recovery. The investor programme certainly generated a significant inflow of foreign capital: investment through the visa programme represented about 13-15 per cent of all foreign transactions in the real estate market between 2013 and 2017 (Surak and Tsuzuki Citation2021: 17).

While the two main governing parties – the Conservative People’s Party (PP) and the Spanish Socialist Workers Party (PSOE) – diverge on many other issues, there is a long-established political consensus over the construction-centric economic model. Both parties have pursued similar policies towards construction and housing when in government (Baccaro and Pontusson Citation2022: 215) and both parties sought to encourage foreign investment in property after the crash. López and Rodríguez describe how rising property values was seen as ‘a matter of the state’ (2011: 17).

With a relatively modest threshold of €500,000, exactly half the amount required if an applicant opts for the capital investment route, Spain’s investor scheme is clearly focused more on generating investment into the property market than on attracting high net worth foreigners. Unlike the French policy, Spain’s investor visa does not look to attract entrepreneurial migrants, so much as stimulate growth in the housing sector. While both policies emerged in response to the Eurozone crisis, the contrast between them illustrates how different economic models, and the diagnosis of economic problems and their solutions by political elites within the context of those models, have shaped the types of investment targeted by investor programmes.

Discussion

Our case studies show that behind the common trend towards residence-by-investment schemes, lie significant differences in their policy aims. On the one hand, the introduction or liberalisation of investor schemes after the 2008 crisis can be seen in all three countries. As part of their attempts to stimulate economic growth in the context of recession and fiscal austerity, the governments of the three countries all sought to facilitate migration of the global rich: France and Spain by introducing a new investor route, the UK by liberalising its existing one. In all three cases, the admissions criteria and in-country rights afforded to investors were significantly more generous than for skilled and high-skilled workers.

Another common theme is the relative absence of political contestation surrounding the introduction of residence-by-investment schemes. The introduction of investor visas did not, at least initially, attract political controversy that often surrounds proposals to open routes for migrant workers. This is surely in part because investor migration is much smaller than labour migration, so barely registers on overall numbers; but it also seems to reflect cross-party assumptions that investor migration could be championed as a straightforward benefit to the host country. In none of the three countries we examined did opposition parties mobilise against investor migration. Indeed, there was a cross-party consensus that attracting wealthy people was beneficial, whether to stimulate the housing market (Spain), liberalise the economy (France), or enable flows of foreign capital into a global financial centre (the UK).

This said, with the closure of the UK scheme in 2022, and the announcement by the Portuguese government in February 2023 that it intends to close its golden visa scheme, cracks are beginning to show in this consensus. As long ago as 2014, research for the UK government had found the economic benefits of the Tier 1 investor scheme to be unclear (MAC Citation2014). Others have questioned the potential for investor visas to facilitate illegal and corrupt activity. The European Commission raised concerns that investor visas may facilitate money laundering and tax evasion (European Commission Citation2019a). Ana Gomes, the former Portuguese MEP who campaigned on corruption, was more direct: ‘golden visas are an insane program, because obviously they are conduits for importing organised crime in the European Union’ (quoted in Transparency International 2015: 16). It is too early to judge whether the closure of the UK and Portuguese schemes will be followed by a wider retrenchment, but geopolitical shifts do appear to be undermining European governments’ enthusiasm for golden visas.

The elite-driven character of investor visa policymaking arguably means that investor visas are more susceptible to geopolitical shifts than labour migration policies embedded in the demands of domestic interest groups. When the political heat goes up, investor visas can be quickly dropped, as the UK case illustrates. The Russian invasion of Ukraine, and what the European Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen, has called ‘more distant and more difficult’ relations with China (European Commission Citation2023) have redrawn the geopolitical map, reinforcing concerns about permissive approaches towards those country’s elites (notably, Russia and China were the top two nationalities for the UK investor scheme). It is possible that other investor visa schemes will come under pressure given the ‘economic de-risking’ that von der Leyen advocates, and the EU’s wider ‘strategic autonomy’ agenda.

At the same time, we have shown that investor visas policies are embedded in national political economies in ways that may ensure their resilience where the risks are perceived to be low and economic benefits high. The different aims and investment targets of the various schemes can be traced to differences in the sectoral composition and drivers of growth in national economic models, and to elites’ diagnoses of how to revive growth in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis. Thus, successive UK governments sought to fuel London as a global financial centre, enabling the super-rich to channel money into the City of London, property, and luxury consumption; the French investor policy was part of the Sarkozy government’s attempt to attract technology entrepreneurs and liberalise the French economy; while Spain’s investor scheme was intended to reflate the property market and rescue the dominant construction sector by attracting real estate investments. These findings contribute to our understanding of investor visas and to the wider literature on the comparative political economy of immigration policy. Investor visas reflect policymaking elites’ ideas about economic growth, which are influenced by dominant sectors of the prevailing ‘growth model’ (Baccaro et al. Citation2022). Drawing out these connections illustrates how economic structures interact with both domestic and global politics to influence immigration policy outputs.

Conclusion

In this article we have made two contributions to the literature on residence-by-investment schemes. First, by comparing investor visas with labour migration policies we have shown that admission is easier for the wealthy than for those who migrate to work across three major European economies. In all three of the countries we examined, admissions criteria were less stringent, and in-country rights more generous, for those with significant financial and not merely human capital. This finding reinforces the argument that even among migrants that states ‘court’, let alone those that they seek to ‘fend off’ such as family migrants (Joppke Citation2021: 68), access to residence in Europe has been commodified. In France, Spain and (until 2022) the UK, wealthy foreigners could gain residence on terms that were significantly more advantageous than migrant workers, including those deemed to be highly skilled. European governments often talk about attracting the ‘brightest and best’, but it is, to coin a phrase, the ‘wealthy who invest’ who often enjoy preferential entry conditions and rights.

Second, we have explored how variation in investor visas is influenced by national configurations of capitalism. While there has been a Europe-wide trend to adopt residence-by-investment programmes, investor visa policies take different forms across countries. We have shown how investor visa policies are shaped by political elites’ ideas about growth within the context of distinct national economic models, specifically the kinds of investment that are considered conducive to growth given the sectoral composition of the national economy. Across the UK, France and Spain, different kinds of investor, and different kinds of investment, have been courted: the UK investor visa scheme enabled a flow of no-strings-attached foreign capital into London’s financial services and property market; the French scheme sought tech-entrepreneurs as part of Sarkozy’s project to liberalise the economy; while the Spanish investor visa targeted property buyers in an explicit attempt to rescue the construction sector after its post-2008 collapse. Three cases are not sufficient to draw general conclusions, but our findings suggest that comparative analysis grounded in national models of political economy can help to explain not only how, but why investor visa policies vary between countries.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Erica Consterdine

Erica Consterdine is a Senior Lecturer in Public Policy at the Department for Politics, Philosophy and Religion, Lancaster University. Her research focuses on immigration policy and governance and has been published in the Journal of European Public Policy and British Journal of Politics and International Relations amongst others. [[email protected]].

James Hampshire

James Hampshire is a Professor of Politics at the University of Sussex, and Deputy Editor of the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 We can present only a short summary of the ImPol methodology in this section. For more details including the coding scheme see Consterdine and Hampshire (Citation2016).

2 Further details on ISCO can be found at https://www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/stat/isco/isco08/.

3 ImPol scores range from 1 to -1. We show only 0-1 in this Figure since the policies for economic migrants (investors, high-skilled and skilled workers) that we examine in this article fall within this range. Policies for some other kinds of migration (for example, family migrants) often fall between 0 and -1.

4 Analysis of Home Office data at https://getgoldenvisa.com/uk-tier-1-investor-visa-statistics

5 Note that our Impol measures do not capture the quantum of visa fees, which is why our coding of the investor visa does not change after 2014. This may however be considered a restrictive move, and as such, a caveat to our index recording a stasis from 2014-16.

6 Absence from territory does not appear in list of situations for which a residence permit can be withdrawn; CESEDA, art. R311-14.

7 See la French Tech website, available at http://www.lafrenchtech.com/en-action/pass-french-tech.

8 Law 14/2013, of 27 September, on the support to entrepreneurs and their internationalisation (Ley 14/2013, de 27 de septiembre, de apoyo a los emprendedores y su internacionalización), Official State Gazette 233 of 29 September 2013, BOE-A-2013-10074, available at https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2013-10074 (Law 14/2013).

References

- Afonso, Alexandre, and Camilla Devitt (2016). ‘Comparative Political Economy and International Migration’, Socio-Economic Review, 14:3, 591–613.

- Baccaro, Lucio, and Fabio Bulfone (2022). ‘Growth and Stagnation in Southern Europe’, in Mark Blyth, Jonas Pontusson and Lucio Baccaro (eds.), Diminishing Returns: The New Politics of Growth and Stagnation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 293–322.

- Baccaro, Lucio, and Jonas Pontusson (2022). ‘The Politics of Growth Models’, Review of Keynesian Economics, 10:2, 204–21.

- Baccaro, Lucio, Mark Blyth, and Jonas Pontusson (eds.) (2022). Diminishing Returns: The New Politics of Growth and Stagnation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Balch, Alex (2010). ‘Economic Migration and the Politics of Hospitality in Spain: Ideas and Policy Change’, Politics & Policy, 38:5, 1037–65.

- BBC (2022). ‘UK Scraps Rich Foreign Investor Scheme’, 17 February 2022. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-60410844.

- Beine, Michel, Anna Boucher, Brian Burgoon, Mary Crock, Justin Gest, Michael Hiscox, Patrick McGovern, Hillel Rapoport, Joep Schaper, and Eiko Thielemann (2016). ‘Comparing Immigration Policies: An Overview from the IMPALA Database’, International Migration Review, 50:4, 827–63.

- Besson, Eric (2009). ‘Eric Besson a présenté la carte de résident pour contribution économique exceptionnelle’, interieur.gouv.fr

- Boräng, Frida, and Lucie Cerna (2019). ‘Constrained Politics: Labour Market Actors, Political Parties and Swedish Labour Immigration Policy’, Government and Opposition, 54:1, 121–44.

- Boucher, Anna, and Lucie Cerna (2014). ‘Current Policy Trends in Skilled Immigration Policy’, International Migration, 52:3, 21–5.

- Caviedes, Alexander (2010). Prying Open Fortress Europe? The Turn to Sectoral Labour Migration. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers.

- Clift, Ben, and Sean McDaniel (2021). ‘Capitalist Convergence? European (Dis?)Integration and the Post-Crash Restructuring of French and European Capitalisms’, New Political Economy, 26:1, 1–19.

- Consterdine, Erica (2018). Labour’s Immigration Policy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Consterdine, Erica, and James Hampshire (2014). ‘Immigration Policy under New Labour: Exploring a Critical Juncture’, British Politics, 9:3, 275–96.

- Consterdine, Erica, and James Hampshire (2016). ‘Coding Legal Regimes of Immigration Entry to the EU with a Focus on Labour Migration’, https://www.temperproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Working-Paper-8.pdf.

- Consterdine, Erica, and James Hampshire (2020). ‘Convergence, Capitalist Diversity, or Political Volatility? Immigration Policy in Western Europe’, Journal of European Public Policy, 27:10, 1487–505.

- Culpepper, Pepper (2010). Quiet Politics and Business Power: Corporate Control in Europe and Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- De Haas, Hein, Katharina Natter, and Simona Vezzoli (2018). ‘Growing Restrictiveness or Changing Selection? The Nature and Development of Migration Policies’, International Migration Review, 52:2, 324–67.

- Devitt, Camilla (2011). ‘Varieties of Capitalism, Variation in Labour Immigration’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 37:4, 579–96.

- Džankić, Jelena (2015). ‘Investment-Based Citizenship and Residence Programmes in the EU’, EUDO/RSCAS Working Paper 2015/08. Florence: EUI.

- Džankić, Jelena (2018). ‘Immigrant Investor Programmes in the European Union (EU)’, Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 26:1, 64–80.

- European Commission (2019a). ‘Investor Citizenship and Residence Schemes in the European Union. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, and the Committee of the Regions’, COM(2019) 12 final.

- European Commission (2019b). ‘Executive Summary – Investors’ Residence Schemes in France’ in B.II Detailed Research – Country Summary Reports’, Online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/eu-citizenship/eu-citizenship/investor-citizenship-schemes_en.

- European Commission (2019c). ‘Executive Summary – Investors’ Residence Schemes in Spain’ in B.II Detailed Research – Country Summary Reports’, Online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/eu-citizenship/eu-citizenship/investor-citizenship-schemes_en.

- European Commission (2023). ‘Speech by President von der Leyen on EU-China Relations to the Mercator Institute for China Studies and the European Policy Centre,’ 30 March 2023. Online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_23_2063.

- European Parliament (2014). Resolution of 16 January 2014 on EU citizenship for sale (2013/2995 (RSP)).

- Freeman, Gary P. (1995). ‘Modes of Immigration Politics in Liberal Democratic States’, International Migration Review, 29:4, 881–902.

- Freeman, Gary P. (2006). ‘National Models, Policy Types, and the Politics of Immigration in Liberal Democracies’, West European Politics, 29:2, 227–47.

- Gabizon, Cécilia (2009). Le gouvernement veut attirer les immigrés entrepreneurs, 16/09 (lefigaro.fr)

- Gamlen, Alan, Chris Kutarna, and Ashby Monk (2019). ‘Citizenship as Sovereign Wealth: Re-Thinking Investor Immigration’, Global Policy, 10:4, 527–41.

- Harpaz, Yossi (2022). ‘One Foot on Shore: An Analysis of Global Millionaires’ Demand for US Investor Visas’, The British Journal of Sociology, 73:3, 554–70.

- Helbling, Marc, Liv Bjerre, Friederike Römer, and Malisa Zobel (2017). ‘Measuring Immigration Policies: The IMPIC Database’, European Political Science, 16:1, 79–98.

- Home Office (2006). A Points-Based System: Making Migration Work for Britain, Cm 6741. London: HMSO.

- House of Commons (2023). The Tier 1 (Investor) route: Review of operation between 30 June 2008 and 6 April 2015. Statement made on 12 January 2023, UIN HCWS492

- Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament (2020). Russia, HC 632, 21 July 2020. https://isc.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/20200721_HC632_CCS001_CCS1019402408-001_ISC_Russia_Report_Web_Accessible.pdf.

- Joppke, Christian (2021). Neoliberal Nationalism: Immigration and the Rise of the Populist Right. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kharpal, Arjun (2017). ‘French President Macron Launches Tech Visa to Make France a ‘Country of Unicorns’’, CNBC, June 15. https://www.cnbc.com/2017/06/15/french-president-macron-france-should-be-a-country-of-unicorns.html.

- Kochenov, Dimitry, and Kristin Surak (2023). Citizenship and Residence Sales: Rethinking the Boundaries of Belonging. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- La Moncloa (2011). ‘Foreign Trade and Immigration Sign Protocol to Promote Foreign Investment’ https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/lang/en/gobierno/news/Paginas/2011/041111Comercio.aspx.

- Leparmentier, P. A. (2007). ‘Le Malentendu, Déjà?’ Le Monde, June 18.

- Levy, Jonah D. (2008). ‘From the Dirigiste State to the Social Anesthesia State: French Economic Policy in the Longue Durée’, Modern & Contemporary France, 16:4, 417–35.

- Levy, Jonah D. (2017). ‘The Return of the State? France’s Response to the Financial and Economic Crisis’, Comparative European Politics, 15:4, 604–27.

- López, Isidro, and Emmanuel Rodríguez (2011). ‘The Spanish Model’, New Left Review, 69:3, 5–29.

- Lutz, Philipp (2019). ‘Variation in Policy Success: Radical Right Populism and Migration Policy’, West European Politics, 42:3, 517–44.

- Menz, Georg (2008). Varieties of Capitalism and Europeanization: National Response Strategies to the Single European Market. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) (2014). Tier 1 (Investor) Route: Investment Thresholds and Economic Benefits. London: Migration Advisory Committee.

- Parker, Owen (2017). ‘Commercializing Citizenship in Crisis EU: The Case of Immigrant Investor Programmes’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 55:2, 332–48.

- Ruhs, Martin (2013). The Price of Rights. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ruhs, Martin (2018). ‘Labor Immigration Policies in High-Income Countries: variations across Political Regimes and Varieties of Capitalism’, The Journal of Legal Studies, 47:S1, S89–S127.

- Sciolino, Elaine (2007). ‘Sarkozy Wins in France and Vows Break with the Past’, New York Times, May 7.

- Sumption, Madeleine, and Kate Hooper (2014). Selling Visas and Citizenship: Policy Questions Form the Global Boom in Investor Migration. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

- Sumption, Madeline (2021). ‘Can Investor Residence and Citizenship Programmes Be a Policy Success?’, in Dimitry Kochenov and Kristin Surak (eds.), The Law of Citizenship and Money. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Surak, Kristin (2022). ‘Who Wants to Buy a Visa? Comparing the Uptake of Residence by Investment Programs in the European Union’, Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 30:1, 151–69.

- Surak, Kristin, and Yusuke Tsuzuki (2021). ‘Are Golden Visas a Golden Opportunity? Assessing the Economic Origins and Outcomes of Residence by Investment Programmes in the EU’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47:15, 3367–89.

- Transparency International UK (2015). Gold Rush: Investment Visas and Corrupt Capital Flows into the UK. London: Transparency International UK.

- Wright, Chris (2012). ‘Policy Legacies, Visa Reform and the Resilience of Immigration Politics’, West European Politics, 35:4, 726–55.