Abstract

The article examines the gender politics of populist parties in two countries historically marked by cultural traditionalism – Italy and Spain. It defines and compares the articulation of gender issues cross-nationally and intra-ideologically to understand how populist parties contest the politics of gender in the two countries. Drawing on computer-assisted qualitative content analyses of programmatic documents, it assesses the framing and salience of gender by the populist radical left (the Spanish Podemos) and right (Lega and Fratelli d’Italia in Italy; VOX in Spain), while also accounting for an ideologically ambiguous populist party (the Italian Movimento 5 Stelle). It concludes ascertaining the different salience of gender politics among Italian and Spanish populist parties and evinces multiple axes of programmatic proximity and distance – not only cross-nationally, but also intra-ideologically among parties akin.

The recent spread and success of feminist mobilisations such as Non Una di Meno (Not One Less) and Comisión 8M (Commission 8M) are signalling the growing salience of gender politics in the democratic arrangements of South European countries with a pronounced religious heritage. At the same time, the hard-line opposition to gender and sexual equality by traditionalist actors – both in the electoral and protest arenas – seems at least partial testimony to the re-emergence of related concerns in respective public spheres. These examples suggest that the demarcation lines surrounding gender politics are in flux and that alliance structures are being built around the rights at its core – women’s and LGBTQI + rights, gender equality, sexual, and reproductive rights. Despite a growing interest in populism and gender politics, the complex and varying stances of left- and right-wing populist parties on gender have seldom been part of comparative research efforts (Kantola and Lombardo Citation2021). While populism may indeed provide diverse political actors with a common interpretive framework, there is a tendency to conflate populism with radical-right politics – leading to assume that populist parties altogether are averse to the politics of gender. In order to broaden this perspective and enhance comparative knowledge on this phenomenon, this article examines five populist parties in Italy and Spain spanning the left-right ideological spectrum. Besides common background conditions regarding their welfare models, religious and authoritarian legacies, as well as sociocultural contexts, the two countries have taken different approaches to gender politics, diverging in the implementation of policies in the field. In fact, recent research has questioned the existence of a single South European gender regime, making the case for cross-national comparison between Italy and Spain (Alonso et al. Citation2023). We take stock of these premises to disclose commonalities and differences in the way populist parties contest the politics of gender.

The study of populism counts several approaches (Rovira Kaltwasser et al. Citation2017). The so-called ideational approach (Mudde Citation2017) essentially treats populism as a ‘thin ideology’ centring on the moral superiority of the people and a deep-seated aversion towards the elites, ultimately suggesting that politics should echo what the people want. Two elements of populism are relevant to our enquiry: its ‘empty heart’ (Taggart Citation2000) and its majoritarian drive. The first aspect denotes that populism can attach itself to different ideologies and may thus result in left-wing, centrist, and right-wing variants. Populism rarely manifests itself without a core of some kind; accompanying ideologies range from socialism and libertarianism, to nativism and neoliberalism, through centrist reformism (e.g. Taggart and Pirro Citation2021). The second aspect relates to populism’s tension with pluralism and its tenet of rights and freedoms for all. If populism is meant to embody the will of the majority and its alleged superior common sense, how can it preserve its essence and address rather specific dilemmas such as LGBTQI + or reproductive rights? This and other questions pertaining to the respect for minority stances lie at the very heart of the debate on populism and democracy, and call attention to how populist parties of different ideological persuasions approach the politics of gender. While ‘inclusionary’ populist parties (left-wing populists) would be expected to take a progressive stance on gender politics, ‘exclusionary’ populist parties (right-wing populists) should advocate conservative positions on these issues. The picture is however more composite than that. For example, previous work had already detected patriarchal tendencies within the populist radical left (Kantola and Lombardo Citation2019), whereas a global overview highlighted liberal as well as illiberal elements in the relationship between (left- and right-wing) populism and gender (Abi-Hassan Citation2017). We are thus interested in problematising the different stances that populist parties can take on the politics of gender, net of their common people-centrism and anti-elitism.

Until recently, gender politics, as the complex intertwining of issues related to the institutionalisation of gender equality, women’s and LGBTQI + rights, bodily integrity, kinship structures, and sexual morality tended to figure as a secondary concern to scholars of populism (Akkerman Citation2015; Akkerman and Hagelund Citation2007; de Lange and Mügge Citation2015; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2015; Spierings et al. Citation2015). The gender scholarship has conversely tackled current developments in terms of a backlash against gender politics by populist radical-right parties (Köttig et al. Citation2017), due to these actors’ support for traditional family roles and opposition to same-sex marriage or extended reproductive rights. The politicisation of gender politics by these parties hints at a countervailing dynamic between the left and right (Graff and Korolczuk Citation2022), calling for greater attention to the interdependence between (ultra-)conservative and progressive agendas in populist politics.

The relationship between left-wing populism and feminist politics has featured less prominently in the debate but is acquiring own standing (Dean and Maiguashca Citation2018; Caravantes Citation2021; Caravantes and Lombardo Citation2023). These contributions emphasised the populist left’s attempt to build an inclusionary conception of the ‘neglected’ people (i.e. gender, racial, ethnic, and class minorities) in the form of ‘plurinationality’ – in contrast to the exclusionary, ethnic, and nativist identities propounded by the populist right –, while promoting limited leadership, horizontal practices, and the feminisation of politics more broadly (Caravantes Citation2021). The complex picture we derive prompts to delve deeper into the populist politics of gender to unravel meaning-making processes across and within different national contexts.

In our article, we define and compare populist parties’ articulation of gender issues cross-nationally and intra-ideologically to answer the following research question: how do populist parties contest the politics of gender in Italy and Spain? We see theoretical and substantive value in our endeavour. First, we perceive ‘gender politics’ as a complex bundle to unpack and systematise across a number of categories. This effort allows the analysis of how gender-related concerns are framed at the programmatic level. The implications of this rationalisation go beyond the party politics of populism and could be fruitfully applied to the study of the supply side of gender politics by any political actor. Second, our comparative strategy allows us to highlight not only cross-national but also intra-ideological patterns of convergence and divergence. While expecting the presence of a conservative/traditionalist vs. progressive/libertarian divide to define the populist politics of Italy and Spain, we also account for the possibility that parties from the same country could elaborate on, and attribute salience to, similar gender-related issues on the basis of contextual specificities. The inclusion of relevant parties of the populist radical left and right, on top of an ideologically ambiguous case, helps us cover a lot of ground in the analysis of party-based populism in the two countries.

The article proceeds as follows. We first position ourselves at the intersection of the study of populism and gender politics and make the case for comparative enquiry. We then introduce our research strategy, relying on a partition of gender frames spanning four key categories: cultural, legal, political, and socioeconomic. On the basis of this schema, we move on to the empirical analysis of the gender politics of five populist parties and the discussion of the main findings of our contribution. We conclude ascertaining the different salience of gender politics in Italy and Spain irrespective of the ideological orientation of populist parties. Amid varying salience, we evince multiple axes of programmatic proximity and distance, not only cross-nationally, but also intra-ideologically among parties akin. Just like two sides of the same coin, the populist politics of gender are defined by opposite and mutually reinforcing master frames: a familist frame propounded by socially conservative forces and a liberal-feminist frame advocated by Podemos, the most progressive actor included in our study.

Gender and populism across the political spectrum

Scholarly work at the intersection of populism and gender politics has grown steadily over the past decade (Graff and Korolczuk Citation2022; Norocel and Giorgi Citation2022; Ahrens et al. Citation2018, Citation2021; Kantola and Lombardo Citation2021; Dean and Maiguashca Citation2020; Dietze and Roth Citation2020; Donà Citation2020; Abi-Hassan Citation2017). Interest in this area has been sparked by the appropriation of issues such as gender, women’s rights, sexuality, and family by populist radical-right actors mobilising against a global governance system pushing for greater gender equality (Fangen and Skjelsbæk Citation2020). In this context, the populist radical right constitutes a politically heterogeneous but globally diffused movement fiercely opposed to transnational feminism and gender equality (Corredor Citation2019; Kováts Citation2018). At the heart of this opposition lies a growing resistance to so-called ‘gender ideology’, a notion crafted within clerical and Catholic political circles to signify a social constructivist understanding of gender (Garbagnoli Citation2016). Employed by anti-gender actors to describe an anthropological and epistemological threat as well as a new form of totalitarianism propagated by left-wing and progressive ideologues, ‘gender ideology’ is an ‘ideological matrix of the different reforms they try to oppose, which pertain to intimate/sexual citizenship debates, including LGBT rights, reproductive rights, and sex and gender education’ (Paternotte and Kuhar Citation2018: 8).

Gender politics has provided populist radical-right actors with new ideological ammunition, enemies to target, and rationales for mobilisation. In this sense, anti-gender populist mobilisation is part of a broader culture war on liberalism (but see Maiguashca Citation2019 for a critique on the overuse of ‘populism’). Fundamentally, however, the stances of right-wing populists should be associated to their moralisation of left-wing concerns such as economic injustice or claims against neoliberalism (Graff and Korolczuk Citation2022). Through an exclusionary vision of the welfare state (e.g. ‘welfare chauvinism’), centred on pro-natalist policies and the traditional family (e.g. native and heteronormative), right-wing populists have undermined ‘the left-wing monopoly on voicing critique towards capitalism and to offer a new version of cultural universalism, an illiberal one’ (Graff and Korolczuk Citation2022: 113). This suggests that the politicisation of gender by the populist radical right is part of a countervailing dynamic in response to left-libertarian values.

Research on gender and politics has drawn a set of explanations for the increasing importance of gender arguments to populist radical-right parties. Among these, the tensions between different ideals of womanhood and manhood are chosen to support national identification and renewal (Walby Citation2006). Gender nationalism has also been tied to the anti-gender and anti-feminist agenda (Bernardez-Rodal et al. Citation2022), and used to justify anti-immigration stances.

On the one hand, conservative national projects promoted by the populist radical right see the ‘domesticated’ role of women as carers and reproducers, namely as biological breeders of the nation (Yuval-Davis Citation1993). Within these, the man is responsible for producing and especially protecting the nation from real or imagined threats and a range of ‘outsiders’ (e.g. migrants, Muslims, feminists, LGBTQI + people, etc.). Moreover, a traditional understanding of the family as patriarchal and heterosexual is a sine qua non to guarantee the survival of the nation. Hence, feminist and LGBTQI + people and movements become the primary target of a war on gender, as they ‘uphold values which are contrary – and therefore pose a threat – to national traditions, the majority religion, and the family model’ (Sledzińska-Simon Citation2020: 449).

On the other hand, gender equality – or, better, gender complementarity – can be vindicated in a conservative national project as a distinctive Western or European value. Combining strong pro-family stances and support for male supremacy and patriarchal societies with femonationalist discourses (Farris Citation2017) is part and parcel of the so-called politics of fear (Wodak Citation2015). Those ‘fears’ boil down to ‘barbaric Muslims’ and immigrants as oppressors and rapists of native women and the inevitable demographic replacement of the ethnic and religious autochthonous majority by migrant invaders (Yuval-Davis Citation2008). In a similar vein, homonationalist arguments (Puar Citation2013) can be deployed to support LGBTQI + rights as a way to signal Western superiority vis-à-vis ‘retrograde’ cultures.

Populist left-wing parties have received relatively less attention in relation to these topics. One could argue that, as a tenet of cultural liberalism and progressivism, gender-related issues should naturally fit in the discourses and policies promoted by populist left parties. Little research documented the integration of these ideological elements in the populist framework of the left, which is however far from automatic or straightforward (Caravantes Citation2021; Kantola and Lombardo Citation2019). The non-Western experience provides an early example of scholarly engagement with this phenomenon, actually testifying the complexity, seeming contradictions, and occasional opportunism emerging at the intersection of gender and left-wing populist politics – and thus the necessity to relate these initiatives to their (il)liberal national context (Kampwirth Citation2010; Jaquette Citation2009).

While rejecting exclusionary and nativist types of justifications, the populist left might promote a different national project, featuring constitutional patriotism, social democracy, and the idea of ‘plurinationality’ (Caravantes Citation2021). Within this framework, internal diversity would be celebrated over homogeneity, particularly with respect to marginalised groups and communities. Yet, some scholars have problematised the compatibility of populist left-wing discourses and practices supporting the ‘feminisation and depatriarchalization of politics’ (Dean and Maiguashca Citation2018; Caravantes Citation2021; Kantola and Lombardo Citation2019; Caravantes and Lombardo Citation2023). For example, by referring to the existing ‘tensions and frictions’ between populist and feminist political projects, scholars have unveiled internal dynamics that contradict the feminist ideals claimed by Podemos, such as the use of charismatic and personalistic leadership, a lexicon of domination and competition, the prioritisation of short-term electoral competition, and excessive bureaucratisation, which erode participatory, non-personalistic, horizontal, and collective mechanisms (Caravantes Citation2021). The opportunity to draw on different parties distributed along the left-right ideological spectrum precisely rests on the aspiration to unravel the populist politics of gender across the ideological board as well as cross-nationally.

Framing gender politics

We value understanding which claims are advanced by populist parties in diagnosing gender-related issues, and the way they provide solutions (i.e. policy proposals) supporting a specific project based on a definite gender order. Just as gender arguments might mobilise supporters and voters, it is crucial to appreciate the underlying commonalities and differences in the way populists frame them. So, while there are reasons to assume that their populism could bring them together in their juxtaposition of a righteous people and a self-serving elite, we expect that the stances on gender politics would match the ideological core of parties under consideration and reflect the dynamics at play in respective national contexts. We therefore posit that the populist right would bear a social conservative outlook and identify gender-related issues as alien and treacherous to their conception of the people and the nation-state, whereas endorsement for progressive policies and a drive for equality would fit the script of the populist left. Yet we know very little about whether these stances effectively hold cross-nationally among similar parties (i.e. members of the same party family) or whether there is indeed a role played by context (as per country-specific pro-gender vs. anti-gender contention dynamics) in the way the politics of gender are framed (but see Engeli et al. Citation2012; Annesley et al. Citation2015).

Political actors addressing gender-related issues engage in the making of claims and policies related to the institutional organisation and the discursive constitution of gender, notably with regard to the norms, elements of legal availability, and social acceptability of lived practices in the areas of bodily integrity, kinship structures, sexual morality, and institutionalisation of gender equality. In our attempt to unpack the populist politics of gender, we see these aspects as that bundle of proposals pertaining to the cultural, legal, political, and socioeconomic understanding of gendered phenomena, and as such provide specific frame categories for our use. Indeed, policy analysis has made a strong case for conceiving gender (equality) as multidimensional, encompassing a broad range of issues (Annesley et al. Citation2015: 527). In arguing that gender politics can be framed in different ways – thus, covering multiple policy dimensions and issues – we claim that these aspects can be singled out in practice.

The framing of gender claims provides us with interpretive schemata to understand their nature and scope. For each claim made in the field of gender politics, we assume that their framing can be rationalised on the basis of their policy domain of reference and respond to a function in collective action. Framing processes are at the core of collective action (Benford and Snow Citation2000) and, just like social movements, (populist) political parties continuously engage in framing processes to make sense of phenomena unfolding before them and to challenge their political competitors. Interactions between political parties and social movements often affect the framing of gender issues in the public debate (Lavizzari and Siročić Citation2023). In this sense, the same adoption of terms diffused by anti-gender movements (e.g. ‘gender ideology’) by populist radical-right parties can be considered an outcome of movement-party interactions.

Moreover, framing allows actors to define problems and attribute blame (diagnostic framing) as well as advance solutions and strategies to tackle them (prognostic framing) (Snow and Benford Citation1988: 200–201; see also Pirro and van Kessel Citation2018 for the study of party-based Euroscepticism). In the conception of classic social movement theory, a third framing task (motivational framing) provides a collective ‘rationale for action’ but we concur that ‘agreement about the causes and solutions to a particular problem does not automatically produce corrective action’ and, thus, mobilisation (Snow and Benford Citation1988: 202). In other words, a call to arms is contingent upon a series of factors, which might include – in our case – the resonance or public salience of gender issues. The investigation of demand-side factors exceeds the scope of this study and we thus limit our enquiry to the definition of diagnostic and prognostic frames by populist parties.

Our reading of gender politics spans four key frame categories – i.e. cultural, legal, political, and socioeconomic – and stems from a deductive-inductive logic based on theoretical and substantive knowledge of this phenomenon and the specific reading of programmatic documents. shows the distribution of the issues across the four dimensions. The cultural category refers to how gender issues fit the dominant ideas and customs of a society. The legal, to how these issues relate to changes in the national legal system. The political, to how these issues are linked to institutional politics and representation. The socioeconomic, to how these issues are considered in connection to welfare and the creation of wealth in society. A few examples should suffice to get the point across. Right-wing populist parties might identify the demographic crisis as one of the problems affecting the nation (diagnosis) and advance proposals such as financial bonuses for babies or policies to reduce the number of abortions (prognosis). These frames would pertain to the socioeconomic and cultural dimensions of gender politics. Left-wing populist parties might see the root of gender inequality and gender-based violence in the patriarchal status quo (diagnosis) and advocate remedies such as positive discrimination or legislative reforms aimed at tackling homophobia (prognosis). These aspects would concern cultural, political, and legal interpretations of gender politics. We concede that clear-cut distinctions may not always apply. Some parties might frame a single issue in multiple ways and specific issues lend themselves to multiple interpretations. Any such instances are duly acknowledged in our empirical analysis. Nonetheless, in the analysis, the frame categorisation responds to a party’s own framing of an issue instead of an arbitrary system of classes.

Table 1. Dimensions and issues of party-based gender politics.

While the objective of our fourfold categorisation is trying to be as comprehensive and systematic as possible in defining the multiple framings of gender politics, we also acknowledge that our scheme cannot be deemed conclusive as the realm of asymmetric power dynamics between women and men, and between the ‘feminine’ and the ‘masculine’ (Ahrens et al. Citation2018: 6) is historically bound and culturally defined, and thus in constant evolution and redefinition.

Case selection, data, and methods

The aim of this study is to outline patterns of convergence and divergence in the framing and salience of gender politics by populist parties, cross-nationally as well as intra-ideologically. In this regard, Italy and Spain provide two cases of successful populist mobilisation across the political spectrum (Rooduijn et al. Citation2019): the Italian case with the radical-right Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy, FdI) and the Lega (League, formerly known as Northern League) as well as the ideologically ambiguous Movimento 5 Stelle (5 Star Movement, M5S); the Spanish case with the radical-left Podemos (We Can) and the radical-right VOX (Voice). The three populist radical-right parties bear a number of common ideological traits for their hard-line positions on migration, soft Euroscepticism, and endorsement of neoliberal economic agendas, but the Italian FdI and the Spanish VOX deliver a more traditionalist profile when it comes to social values (Taggart and Pirro Citation2021). VOX also qualifies as a rather idiosyncratic actor due to its politicisation of anti-separatism (Rama et al. Citation2021). The remaining two parties are Podemos in Spain and the M5S in Italy. While Podemos has toned down part of its populist outlook, it still fits the populist radical-left party family with a pronounced libertarian and democratic socialist profile (Kioupkiolis Citation2019). Conversely, the M5S defies straightforward categorisations in terms of left and right due to the inclusion of post-materialist and mild nativist themes in its agenda (Pirro Citation2018). At least initially, the M5S has served as a functional equivalent to a left-libertarian party (Conti and Memoli Citation2015) – a progressive profile that the party has recently tried to revamp after the ideological ambiguity and organisational turmoil of the first years of institutional representation.

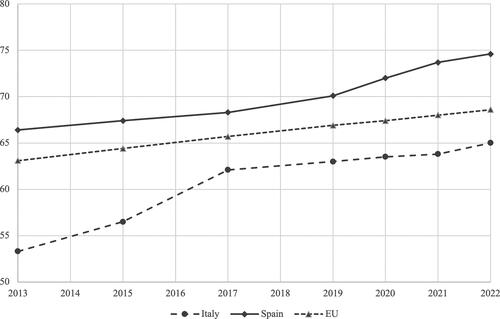

The opportunity to consider Italy and Spain rests in their similar sociocultural context when it comes to their Catholic legacy, strong patriarchal culture, and familistic model of their welfare state – all elements we deem central to the debate on morality and gender politics. Even though we approach Italy and Spain as similar cases, research acknowledges the existence of differences regarding their gender politics, arguing for two different gender regimes: ‘while the Spanish gender regime has become increasingly public-progressive, the Italian gender regime remains public-conservative’ (Alonso et al. Citation2023). We concur that contextual differences should be taken into account. Ecclesiastic hierarchies continue to have a significant influence on the Italian political debate and greater access to state institutions compared to Spain. Italy’s political system and frequent changes of governments, including stronger moderate-right parties, have prevented it from attaining results in the realm of gender politics – lacking the institutional infrastructure to implement and streamline gender equality. Along these lines, women’s representation in the political sphere is still lower in Italy compared to Spain. Overall, according to the latest release of the European Institute for Gender Equality’s (Citation2022) Index, Italy still falls behind the EU average (3.6 points below), while Spain features among the first ten EU countries (6 points above average). Looking at the longitudinal trend from 2013 to 2022, we can observe that, while narrowing, the gap between the two countries is still remarkable – from 13.1 points in 2013 to 9.6 points in 2022 ().

Figure 1. Gender Equality Index (2013–2022). Longitudinal trends in Italy, Spain, and the EU. Source: EIGE – European Institute for Gender Equality. Available from: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-equality-index/2022. Note: The Gender Equality Index gives the EU and Member States a score from 0 to 100, where 100 means the achievement of full gender equality. For visual clarity, the figure shows only the range from 50 to 80.

In both countries, the most significant developments in gender equality policies have come from moderate-left governments – a role generally more marked in Spain than Italy, where progress was mostly pressured from the outside through the adoption of EU directives (Valiente Citation2008). Yet, both the left and right have turned gender into an important turf of contestation (Lombardo and Del Giorgio Citation2013; Valiente Citation2008). Since its transition to democracy, Spain has steadily worked towards the advancement of gender equality initiatives and the consolidation of means to implement them (Bustelo Citation2016; Valiente Citation2008).

In the past few years, both countries have seen the rise of a large-scale feminist movement drawing direct inspiration from Ni Una Menos in Latin America. In Spain, these progressive instances have been partly institutionalised through the alliance with the populist radical-left Podemos. Indeed, in Italy alliances between feminist activists and policy-makers are weaker than Spain – a factor dependent on the different history and type of women’s movements: ‘a strong and state-oriented feminist movement in Spain vs. strong but autonomous Italian feminist movement’ (Alonso et al. Citation2023). The radical-right VOX has also hijacked the debate on gender politics (Alonso and Espinosa Fajardo Citation2021), though from antithetical positions, in a way suggesting a specific countervailing dynamic at play – a dynamic possibly accrued by Podemos’ participation in government between 2019 and 2023, and VOX’s continued opposition status at the national level. Italian parties have been generally less vocal about gender politics compared to Spain, although ‘traditionalist players’ have taken anti-gender positions through public protests, agenda-setting, and alliance-building with right-wing parties (Lavizzari and Prearo Citation2019). The debate on the politics of gender acquired new impetus and the two populist radical-right parties – FdI and Lega – qualify as the most prominent anti-gender actors in the electoral arena (Bellé and Donà Citation2022). Italy also sees a third, ideologically ambiguous, populist party in the M5S, which has shaken Italian politics since its entry to parliament in 2013. The ideological variation among the parties included in this study therefore allows us to assess how ideologically proximate parties (i.e. populist radical right) frame and attribute salience to gender politics cross-nationally – and, in the case of the M5S, ascertain whether the party stands on conservative or progressive grounds with regard to gender.

Our sources of analysis are official manifestos and thematic documents released by the five parties. Manifestos qualify as one of the most authoritative sources to infer the ideological and policy positions of political parties (Budge Citation2001). Unlike other sources (e.g. interviews, speeches, or statements issued by single party officials), they are meant to convey the collective position of a party at a given point in time, thus enhancing the validity our comparative research effort. For reasons related to the lifespan of these parties and the comparability of sources, we consider 25 programmatic documents released since 2013 (see Appendix).Footnote1 All parties have issued at least one electoral programme in concomitance with general and/or European elections (FdI Citation2013, Citation2018, Citation2019; Lega Nord Citation2013; Lega Citation2018; M5S Citation2013, Citation2018, Citation2018; Podemos Citation2015, Citation2016, Citation2019a; VOX Citation2014a, Citation2015a, Citation2016, Citation2019). The Spanish parties have however released additional thematic documents (Podemos Citation2019b, Citation2019c, Citation2019d, Citation2019e; VOX Citation2014b, Citation2015b, Citation2015c, Citation2015d, Citation2015e, Citation2015f), focusing on issues pertinent to this study: organisational structure, political principles, ethical guidelines, feminism, abortion, equality, family, and gender-based violence. While these documents are not fully-fledged electoral programmes, they are presented as complementary, in-depth material, which is directly relevant to our enquiry. For the analysis, we read all documents in their entirety, singling out and coding relevant sentences and paragraphs with the software NVivo. The coding consisted in identifying the frame dimension of reference (i.e. cultural, legal, political, and socioeconomic, as per ); the problems and solutions advanced by populist parties (i.e. their diagnostic and prognostic framing); and the overall salience of the different dimensions in their discourse. Specifically, our holistic measure of salience refers to the overall frequency of frames, for each dimension, across all party documents considered. A party may thus score higher or lower on a given dimension based on whether issues falling into such dimension are present and salient (core), present but not salient (not core), or absent in official party documents.

Contesting gender across different dimensions

Starting our empirical analysis from the salience attributed to gender-related themes, we observe that Spanish parties show comparatively greater attention to these issues compared to Italian ones. The overall frequency of these issues and the very same number of programmatic documents released on the subject suggest that the radical-left Podemos and radical-right VOX both list gender politics as core questions in their agendas, while the radical-right FdI and Lega as well as the ideologically ambiguous M5S show remarkable variation across frame categories (). We take this as preliminary evidence of the countervailing dynamic at play among Spanish populist parties.

Table 2. Populist party frames on gender politics, scores per dimension, Italy and Spain.

Cultural dimension

In its first programmatic document, the Italian radical-right FdI defined the ‘right to future’ as the right to become parents. Within a cultural framework, Giorgia Meloni’s party first reference to gender politics is found in the commitment to ‘resolutely promote natality and support the couple in their important educational role’ (FdI Citation2013). More direct and confrontational claims on gender politics are successively addressed in the 2018 manifesto, including explicit references to the defence of the natural family, combating gender ideology, and overt pro-life stances (FdI Citation2018). A trend towards more assertive positions on gender policies is confirmed in 2019, when FdI set out to ‘contrast the unacceptable practice of the uterus for rent’ (FdI Citation2019). On the practice of surrogacy, complex debates exist inside (and outside) feminist and LGBTQI + movements too, which are then mirrored in the rhetoric of populist parties, especially in terms of ‘exploitation of women’s bodies as a form of neo-colonialism, women’s right to be a mother, and the commodification of birth rights’ (Lavizzari and Siročić Citation2023: 483).

The other radical-right party of Italy, the Lega, initially placed the accent on the defence of the natural family and protection of life; and educational freedom on the part of the family – i.e. allowing parents not to expose children to ostensibly contentious educational choices (Lega Nord Citation2013: 4). Since Matteo Salvini’s rise to leadership, the party has raised awareness on the important role of the education system in promoting the social value of the family (Lega Citation2018: 51).

The ideologically ambiguous M5S (Citation2018) also provided a cultural interpretation of gender-related issues, stressing the generic role of education, yet from a different, overall progressive perspective. The party indeed envisaged a society free from violence and hate to be contrasted primarily through school education. The ambition was to train citizens to respect and value diversity, promoting the culture of tolerance against any form of discrimination – hereby included the struggle against gender violence. The party thus proposed to invest in interdisciplinary training on emotional education, affect, and gender equality.

The Spanish radical-right VOX placed gender politics at the forefront of its ideological supply. Its initial diagnosis is one of ‘multiple crises’, among which the most dramatic is the crisis of collective morality or values (VOX Citation2014a, Citation2014b). According to the party, a morally fit society should promote the culture of life. In order to defend life, VOX claimed that it is crucial to preserve its primary unit, i.e. the natural family. Once affirmed the primacy of the family, the education of its members becomes key for society as a whole. The pinnacle of VOX’s pro-life credo is the objective of ‘zero abortions’, to be attained through ‘information’, ‘support’, and ‘alternatives’. The party notably framed its stance in terms of a clash between the culture of life and the culture of death (VOX Citation2014b).

In its following documents, Santiago Abascal’s party further elaborated on these issues. The party opposed the notion that abortion could be equated to a right, thus challenging the current cultural and legal framework surrounding abortion in Spain. We note a dramatisation and pathologisation of the issue in which all aspects of abortion are seen to bear health and psychological consequences for the mother. VOX identified several means to counter abortion and thus safeguard the mental health of the mother and the life of children (even those deriving from sexual assault or those with difficulties). In addition to these aspects, the party campaigned against conscientious objection and firmly stood against surrogate maternity – an issue framed in terms of human trafficking and biological colonisation. VOX also interpreted education as a cultural tool, attributing problems in this area to the instrumentalisation by ideological opponents. Similar to the Lega in Italy, the party suggested that parents should enjoy educational freedom of choice on the basis of their own beliefs. Within this context, emphasis was given to Christian and single-sex education (VOX Citation2015b). Finally, one of VOX’s cultural leitmotifs rested in its defence of equality – of dignity, rights, and duties – irrespective of gender: ‘We do not believe in positive discrimination as a means to reach this objective’ (VOX Citation2015d: 2).

With regard to the radical-left Podemos, the party advocated a number of measures to guarantee women’s self-determination and choice, such as assisted reproduction and voluntary termination of pregnancy in the public health system as well as distribution and access to contraceptives. While much attention was paid to aspects related to pregnancy, Podemos also stressed the adoption of cultural activities promoting gender equality, countering sexist stereotypes, supporting women in art, etc. (Podemos Citation2015) – an opposite framing compared to VOX and endorsing positive discrimination.

By the year 2019, the party proposed the creation of feminist classes/courses in public education and – similarly to the Italian M5S – a greater focus on sexual and affective education in schools; preventive measures in cases of bullying related to sexual orientation, gender identity, or expression; and the promotion of female sports (Podemos Citation2019a). Notably, Podemos’ gendered agenda actively included the LGBTIFootnote2 community, on the one hand seeking to build alliances with this movement and, on the other, to mend and revive its historical memory (Podemos Citation2019b).

Populist parties in Italy and Spain thus often framed cultural aspects in terms of education, providing clear evidence that schools and children’s curricula have become a central ideological battleground. Indeed, all radical-right parties privileged a familist frame, identifying parents as educators within a system freed from gender ideology. Podemos – and to a lesser extent the M5S – engaged with the promotion of affective education and gender equality. The Spanish parties finally placed pregnancy at heart of their discourse, with Podemos advocating freedom of choice and VOX a radical pro-life stance.

Legal dimension

Among Italian parties, FdI addressed shared custody in its 2013 manifesto. Meloni’s party framed the issue in terms of ‘dual parenthood’, defined as the right of children to be raised in a balanced manner by both parents also in the event of their separation (FdI Citation2013).

The Lega presented diagnostic and prognostic frames vis-à-vis legal aspects only later compared to FdI, hinting at the central role of new leader Salvini in further steering the party in a nativist and authoritarian direction. Salvini’s party defined gender-based violence as a problem, further aggravated by the inadequate protection of, and assistance to, the victim. The party proposed to tackle the slow judicial process and criminalise and severely punish stalking. As an additional measure, the Lega also advocated chemical castration for sexual offenders such as paedophiles and rapists. The party then identified another problem: the disparity in parental rights and the inadequacy of the legislation on separation and divorce, for example leaving fathers not being recognised as even having access to child custody. To resolve this problem, the party proposed equal access to both parents through legislative reform. Notably, this problem could lend itself to a socioeconomic interpretation, since fathers are portrayed as increasingly burdened by child allowances. Finally, the Lega outlined another proposal – in this case cutting across cultural and legal frame categories – demanding that references to the mother and father, as well as their birthnames, are the only rightful ways to address parental figures (Lega Citation2018).

The objective transpiring from VOX’s programmatic documents is similar to the Lega: attributing more rights – or equal standing – to the father figure. Right from the outset, the party defined the neglect of children’s rights in the case of divorce a clear problem, suggesting that the child should be spared any repercussion and the legislator adopt shared and cooperative custody (VOX Citation2014a). Exclusive custody is seen to hamper the child’s learning prospects by missing one reference figure (i.e. the father). In response to this problem, VOX framed shared custody not only as a norm, but also a right of the child and a legal imperative (VOX Citation2015a). VOX reiterated these positions in successive documents (VOX Citation2016, Citation2019).

In addition, VOX has consistently attempted to redefine the notion of gender-based violence, framing it in terms of ‘intra-family violence’.

VOX stands for the abrogation of the legislation based on gender ideology and the reform of law on gender-based violence, converting it into a law on intra-family violence. (VOX Citation2015a: 2)

The party has argued that punishment should be equal regardless of the gender of the perpetrator and that there should be a presumption of innocence – and no jailing – for those who were not found guilty. In addition, VOX suggested the creation of a system to guarantee the veracity of denounced facts against the possibility that crimes are staged, undertaking remedies to tackle false accusations. Abascal’s party also sought to amend the praxis behind the protection of victims of abuse (VOX Citation2015a).

From an opposite ideological angle, Podemos prospected changes to the Ley de Violencia de Genero so as to interpret women as active subjects and not as victims, and recognise all those forms of sexist violence identified by the Istanbul Convention. The party also envisaged forms of psychosocial assistance for convicted men alongside swift housing solutions for targets of violence (Podemos Citation2015).

Podemos then called for a constitutional reform to tackle discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity; the creation of a law on gender identity paying attention to transexual and intersex people; and the change of the Ley de Autonomía y Dignidad to integrate the claims of the feminist and independent living movements (Podemos Citation2015: 114). The party endorsed the recognition of all types of families – especially for the sake of adoptions – to make sure that ‘lesbian couples do not have to fill out paternity forms to become mothers’ (Podemos Citation2015: 128). Podemos also advocated the repeal of the Ley de Interrupción Voluntaria del Embarazo to guarantee that minor girls can voluntarily interrupt their pregnancy without paternal consent (in case of abuse or vulnerable conditions); the approval of the Ley de Asilo revising the admission system to strengthen admissions on grounds of gender-based discrimination and violence, sexual orientation, etc. (Podemos Citation2015).

Podemos preserved its proposals unchanged across time, introducing only a few issues in later manifestos. Those included a proposal on the introduction of a law for sexual freedom, based on a shift in the sexual consent paradigm – from ‘no means no’ to ‘yes means yes’ (Podemos Citation2019a). The party finally called for the creation of a civil registry including a non-determined sex for intersex and queer people – ‘a perspective that breeds into the fact that in today’s society sex is becoming irrelevant in the legal field’ – and the indenisation of LGBTI people unfairly condemned for their sexual orientation (Podemos Citation2019b: 16, 19).

Overall, Italian populist parties placed relatively little emphasis on a legal interpretation of gender politics; the M5S effectively did not address any such issue. All radical-right parties subscribed to a patriarchal frame and called for a revision of respective national legislation, which is perceived to favour the mother over the father figure. The Lega in Italy and VOX in Spain however took different stances on gender-based violence: while the first adopted an authoritarian frame and advocated harsh measures for perpetrators, the second contested the concept of gender-based violence to the core. In this regard, Podemos once again moved from opposite premises, advancing – within a liberal-feminist framework of action – several proposals to counter gender-based violence and enhance the rights of LGBTQI + people.

Political dimension

As far as the political interpretation of gender politics is concerned, VOX (Citation2015d, Citation2019) repeatedly asserted its hostility towards positive discrimination, proposing to eliminate gender quotas in electoral lists, political parties, companies, and institutions.

Podemos initially proposed mainstreaming gender in public administration offices as well as adopting measures and establishing a number of public institutions dealing with LGBTI rights and gender equality (Podemos Citation2015). In the documents issued in 2019, Podemos clearly subscribed to a feminist perspective and claimed to stand for gender equality and zero tolerance against sexism and homophobia, not only within participatory spaces, but also its own organisation (Podemos Citation2019c). The party denounced the masculine and patriarchal character of traditional political practices, calling for a feminist revision of the relational, organisational, and participatory models of Podemos, e.g. through cooperation and deliberation instead of competition and imposition as well as a series of measures on female representation at local, regional, and national levels (Podemos Citation2019d). Podemos then advocated depatriarchalising the organisation: ‘We need to incorporate feminism into our organisational practices and habits, and not just guarantee equal or bigger presence of women in bodies or most visible posts’ (Podemos Citation2019e: 41). Finally, the party acknowledged itself a laggard in terms of feminist practices and female support. One of the proposals to decentralise and adopt horizontality lied in the promotion of ‘municipalism’, which guarantees the representation of women and other underrepresented groups (Podemos Citation2019b).

Overall, Italian populist parties were not found addressing gender-related issues linked to the political dimension. Even among Spanish parties, these qualified as salient only for the radical-left Podemos. While VOX, from a patriarchal perspective, opposed any form of positive discrimination, Podemos tightly linked the discourse on representation to an anti-patriarchal frame, advancing proposals to favour women and LGBTQI + people in public institutions and its organisation.

Socioeconomic dimension

Looking at the socioeconomic understanding of gender politics, FdI framed the economic crisis as one of the main sources of uncertainty, affecting birth-rate in Italy and ultimately family planning for young couples (FdI Citation2013). In order to solve these problems, Meloni’s party advanced several proposals on childcare: introducing nurseries in the workplace, enhancing life-work balance by linking nurseries’ opening hours to parents’ office hours, extending parental leave to both parents (especially in the first year of life of the child), reducing the VAT on children’s products, introducing a ‘family quotient’,Footnote3 improving labour market conditions for women through remote work and part-time hiring for female labour force, and subsidising housing for young couples.

While FdI’s early proposals centred on the family and how to remedy the treacherous effects of the economic crisis, the issue progressively lost salience and a specific diagnostic frame. Leaving aside the remuneration of domestic work, the 2018 manifesto reiterated and summarised most of earlier proposals (FdI Citation2018). Within the context of its European manifesto, Meloni’s party only introduced a supranational dimension to the issue, proposing the establishment of an EU-wide maternity allowance to tackle the demographic crisis (FdI Citation2019).

The Lega interpreted the family as the ‘first economic unit of society’ (Lega Citation2018: 51), which thus deserved fiscal incentives. The party initially advanced a number of proposals related to taxation (e.g. a ‘no-tax area’ for low-income families), incentives (e.g. a ‘baby bonus’), life-work balance, and childcare (e.g. development plan for nurseries) (Lega Nord Citation2013). In outlining a prognosis to the ongoing demographic crisis, the Lega then called for a structural plan to relaunch natality, envisioning allowances for children of Italian families. Among other proposals, the party called for free nurseries, abolishing the VAT on child products, a pay raise for female employees during maternity leave, and early retirement for mothers (Lega Citation2018).

The M5S’s diagnosis concerned housing problems affecting, among others, single-parent families and young couples; and a health system failing to provide house assistance, thus burdening women in their performance of care work in the household. The party advocated support for family relationships within the public administration and proposed early retirement for women (‘opzione donna’), incentives in the form of reimbursements for nurseries, diapers, and babysitters as well as VAT exemptions on childcare products (M5S Citation2018). The M5S explicitly framed welfare incentives for families as the solution to declining birth-rate (M5S Citation2019).

VOX firmly stood for large families and incentives proportional to the number of children, although most policy proposals should be interpreted in terms of welfare measures for mothers and pregnant women. While linking declining birth-rate to the presence of a multiple and deep systemic crisis, the party prospected fiscal incentives regarding housing, child benefits, and jobs (remote work, flexible workhours, and work leaves); but also facilitated access to healthcare for pregnant women (VOX Citation2014a).

The desired demographic growth has to unfold naturally through the family […] and through a strong fiscal policy in support of the family. (VOX Citation2014b: 12)

Abascal’s party successively reiterated its stances and proposals, especially seeking to rejig subsidies to organisations engaged in contrasting gender-based violence, by monitoring the funds they receive and delinking their allocation from the number of cases processed (VOX Citation2015a). The party also envisaged a ‘baby bonus’ (also for adopted children) and other incentives for companies hiring women victim of violence (VOX Citation2016). By the time of the 2019 elections, the gendered agenda of VOX was fully developed and the party summarised its position as follows:

The macroeconomic strategy has to create an environment of stability within which families and companies plan their future and make their work, saving, and investment decisions without the interference of discretionary government actions. (VOX Citation2019)

Come the election year in 2019, Podemos had framed the financial crisis, the austerity imposed by mainstream parties, and ultimately neoliberalism as the root of all – economic, political, environmental, etc. – crises and the enemy of women’s rights (Podemos Citation2019b, Citation2019e). At this stage, the party notably introduced the concept of ‘economia de los cuidados’ (care economy), which is linked to a ‘care system’ interpreted as follows:

Our welfare State has been built on a massive quantity of unpaid feminine (care) work in order to sustain the family and the austerity took away even more oxygen to this model, bringing it to collapse […] Yet feminist mobilisations have changed everything, putting life at the core of our priorities and showing that this is already a feminist country that can organise itself in a different way. (Podemos Citation2019e: 25)

Overall, socioeconomic frames often boiled down to advocating incentives for parents and opportunities for women. This is the sphere where all populist parties, departing from respective ideological premises, attained greater convergence and addressed gender issues in some degree or form. Zooming in on the radical right, there were essentially no issues addressed by FdI and the Lega in Italy that VOX did not elaborate upon – all subscribing to a familist interpretation of socioeconomic matters. Yet the Spanish case provides another illuminating example of diverging frames: while VOX sought to support mothers within a context of demographic crisis, Podemos advanced a clear anti-neoliberal frame and championed the primacy of care economy.

Discussion and conclusions

We have recently witnessed the increasing salience of gender issues and the emergence of gender politics as a renewed area of contestation. Just as gender politics is entering the mainstream political debate – where this has not already happened – political parties are picking up on these issues and elaborating on specific frames. In our attempt to disclose cross-national as well as intra-ideological patterns of convergence and divergence over the framing and salience of the populist politics of gender, we have focused on two similar country cases displaying differences in terms of gender regimes, and on populist parties that were expected to seise the debate on these issues. In , we summarise the frames employed by these parties, based on the multiple arguments presented, and distributed across the four key dimensions of party-based gender politics identified above. Against the variety of frames and issues propounded, there are a number of comparative conclusions we can derive about the framing and salience of gender politics by populist parties in Italy and Spain.

Table 3. Overview of populist party frames on gender issues, Italy and Spain.

First, in light of the differences noted between the two gender regimes, Spanish populist parties were found to elaborate more on gender politics compared to Italian populist parties. Not only the salience, but also the very same terms of politicisation of gender by the populist radical-left Podemos and the populist radical-right VOX evoke a countervailing dynamic at play in Spanish politics. The antithetical yet substantial correspondence between frames deployed by these parties show, on the one hand, Podemos’ co-optation of progressive grassroots demands and, on the other, the overall relevance and institutionalisation of the traditionalist/libertarian struggle over the politics of gender. Notably, the two Spanish parties released specific programmatic documents addressing in painstaking detail their views on the politics of gender, placing gender equality and feminism (Podemos) and pro-life and familism (VOX) at the core of their concerns. If we were to locate the populist actors included in this study along a traditionalist/libertarian continuum, the Spanish parties would occupy opposite and the most extreme positions – in a way hinting at the salience and polarisation of the debate on gender in Spain. Despite the increasing mobilisation potential and significance of the Italian feminist movement, no such dynamics could be ascertained in the stances of FdI, the Lega, or the M5S. None of these parties has taken positions as radical and detailed as the Spanish populist parties in their manifestos. In other words, contextual specificities have contributed to shape the populist politics of gender in Spain and set them apart from the Italian case.

Second, looking at the content of gender-related discourses – and particularly those of parties akin like the Italian FdI and Lega, and the Spanish VOX – we note both intra-ideological and cross-national differences among populist parties. While Salvini’s leadership has undoubtedly steered the Lega on a nativist and authoritarian track, and thus contributed to integrating aversion to progressive gender politics and patriarchal frames into the ideology of the party, the Lega delivered a less traditionalist character compared to both FdI and VOX. This in a way confirms the internal variety characterising the populist radical right across Europe, not only regarding ‘trademark issues’ such as opposition to migrants and ethnic minorities (Mudde Citation2007; Pirro Citation2014), but also the politics of gender (Verloo and Paternotte Citation2018; Engeli et al. Citation2012). At the same time, it substantiates the ideological proximity between FdI and VOX, which also share a common home in the European Conservatives and Reformists group.

Considering the ideologically ambiguous M5S, we ascertained the gradual inclusion of liberal frames in its platform. These frames were neither particularly elaborate nor salient, but somehow suggest that the M5S might serve as a functional equivalent to a left-libertarian party – at least on paper and as far as gender politics are concerned. In the day-to-day practice of representation in national institutions, however, the behaviour of the party has been quite erratic; one day blocking proposals on same-sex civil partnerships, the next supporting key legislation on gender-based discrimination and violence. While the M5S has struggled to reconcile its inner ideological contradictions, one could also argue that the relatively little emphasis – or even silence – on these issues might actually signal the acceptance of the (stagnant) status quo on gender equality in Italy.

Third, the analysis of different dimensions of gender politics highlighted variety in the type of frames and issues put forward by populist parties. For example, framing gender in political terms was essentially irrelevant to Italian populists, but quite central to the way Podemos envisaged the working of its internal organisation and the political life of the country, thus showing an enhanced elaboration of frames in this category. In this sense, we could interpret Podemos’ gender agenda as an indication of grassroots instances spilling over into institutional and electoral politics, in particular with regard to feminism and LGBTQI + rights. Furthermore, all populist parties seemed to converge in their use of economic arguments, though from distinctive ideological premises. Such a convergence might also testify to a tendency to pay greater attention to ‘class-based gender equality issues’ (Htun and Weldon Citation2010; Annesley et al. Citation2015) regardless of ideology. Finally, regarding the cultural dimension, we ascertained the populist radical right’s instrumentalisation of education as a means to attack gender ideology and, by way of that, their ideological opponents. Interestingly enough, we noted the absence of femonationalist frames in populist radical-right parties’ manifestos – a rather unexpected finding given the popularity of such arguments in nativist campaigns across Europe (Farris Citation2017).

More generally, our enquiry lends credence to the configuration of gender contestation along competing master frames: a familist framing by traditionalist actors, upholding the natural family as the panacea of gender politics on the one hand, and a liberal-feminist framing by progressive forces focused on the mainstreaming of gender equality policies (Gwiazda Citation2021; Engeli et al. Citation2012) on the other. Yet, the extent to which the latter is compatible with feminist goals and practices of democratic transformation has already been put into question (Caravantes Citation2021).

Our article has also provided empirical evidence in support of the inclusive and liberal character of populist radical-left stances on gender. In a context where European populism is often – erroneously – equated to illiberal principles such as nativism or authoritarianism, our findings call for a greater engagement with, and debate on, the populist (radical) left in Europe and its relationship to pluralism and liberal democracy. The fact that there could be parties like Podemos systematically calling for the emancipation of, and more civil rights for, minorities, and that these actors may be perceived in tension with liberal-democratic tenets (due to their populist majoritarianism) is part of a long-overdue discussion in the field of populism and begs for further problematisation. This observation does not necessarily question the moral foundations of the antagonism between ‘the people’ and ‘the elites’ in populists’ framework of action, but prompts the defining of their relationship with pluralism and (liberal) democracy on the basis of their ideology and nuances these aspects as contingent on context.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their careful reading of our work and for their perceptive and constructive comments. We also wish to extend our gratitude to the editors of the journal for their support throughout the process. Andrea Pirro would like to acknowledge the support from the European University Institute; part of this work was carried out during his visiting fellowship at the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anna Lavizzari

Anna Lavizzari is Ramón y Cajal research fellow in the Faculty of Political Science and Sociology, Department of Political Science and Administration, Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Her research interests include social movements and contentious politics, gender studies, LGBTQI + rights and youth political participation. [[email protected]]

Andrea L. P. Pirro

Andrea L. P. Pirro is Assistant Professor in the Department of Political and Social Sciences, University of Bologna. He is editor of the journal East European Politics and editor of the Routledge Book Series in Extremism and Democracy. He is convenor of the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) Summer School on ‘Concepts and Methods for Research on Far-Right Politics’ and has previously served as Steering Committee chair of the ECPR Standing Group on Extremism and Democracy. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 With the sole exception of the Lega (founded in 1991), all populist parties included in this study are relatively ‘new’. The M5S was established in 2009, FdI in 2012, VOX in 2013, and Podemos in 2014. The Lega however completed its transformation into a populist radical-right party since Matteo Salvini stepped in as federal secretary in late 2013, thus offering further grounds to consider the timespan of reference as our period of analysis.

2 This is how Podemos refers to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Intersex people across its programmatic documents. We otherwise use the acronym ‘LGBTQI+’ throughout the article.

3 The family quotient is a mechanism allowing calculation of due taxation on the basis of all family members’ incomes, therefore favouring large families.

References

- Abi-Hassan, Sahar. (2017). ‘Populism and Gender’, in Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul Taggart, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Pierre Ostiguy (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Populism. Oxford University Press, 426–44.

- Ahrens, Petra, Karen Celis, Sarah Childs, Isabelle Engeli, Elizabeth Evans, and Liza Mügge (2018). ‘Politics and Gender: Rocking Political Science and Creating New Horizons’, European Journal of Politics and Gender, 1:1–2, 3–16.

- Ahrens, Petra, Silvia Erzeel, Elizabeth Evans, Johanna Kantola, Roman Kuhar, and Emanuela Lombardo (2021). ‘Gender and Politics Research in Europe: Towards a Consolidation of a Flourishing Political Science Subfield?’, European Political Science, 20:1, 105–22.

- Akkerman, Tjitske (2015). ‘Gender and the Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis of Policy Agendas’, Patterns of Prejudice, 49:1–2, 37–60.

- Akkerman, Tjitske, and Anniken Hagelund (2007). ‘“Women and Children First!” anti-Immigration Parties and Gender in Norway and The Netherlands’, Patterns of Prejudice, 41:2, 197–214.

- Alonso, Alba, Rossella Ciccia, and Emanuela Lombardo (2023). ‘A Southern European Model? Gender Regime Change in Italy and Spain’, Women’s Studies International Forum, 98, 102737.

- Alonso, Alba, and Julia Espinosa Fajardo (2021). ‘Blitzkrieg against Democracy: Gender Equality and the Rise of the Populist Radical Right in Spain’, Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 28:3, 656–81.

- Annesley, Claire, Isabelle Engeli, and Francesca Gains (2015). ‘The Profile of Gender Equality Issue Attention in Western Europe’, European Journal of Political Research, 54:3, 525–42.

- Bellé, Elisa, and Alessia Donà (2022). ‘Power to the People? The Populist Italian Lega, the anti-Gender Movement and the Defence of the Family’, in Bianka Vida (ed.), The Gendered Politics of Crises and De-Democratization. Opposition to Gender Equality. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield/ECPR Press.

- Benford, Robert D., and David A. Snow (2000). ‘Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment’, Annual Review of Sociology, 26:1, 611–39.

- Bernardez-Rodal, Asuncion, Paula Requeijo Rey, and Yanna G. Franco (2022). ‘Radical Right Parties and anti-Feminist Speech on Instagram: Vox and the 2019 Spanish General Election’, Party Politics, 28:2, 272–83.

- Budge, Ian (2001). ‘Theory and Measurement of Party Policy Positions’, in Ian Budge, Hans-Dieter Klingeman, Andrea Volkens, Judtih Bara, and Eric Tanebaum (eds.), Mapping Policy Preferences Estimates for Parties, Electors, and Governments 1945-1998. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 75–90.

- Bustelo, Maria (2016). ‘Three Decades of State Feminism and Gender Equality Policies in Multi-Governed Spain’, Sex Roles, 74:3–4, 107–20.

- Caravantes, Paloma (2021). ‘Tensions between Populist and Feminist Politics: The Case of the Spanish Left Populist Party Podemos’, International Political Science Review, 42:5, 596–612.

- Caravantes, Paloma, and Emanuela Lombardo (2023). ‘The Symbolic Representation of the ‘People’ and the ‘Homeland’ in Spanish Left Populism: An Opportunity for Feminist Politics?’, Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 31:3, 902–15.

- Conti, Nicolò, and Vincenzo Memoli (2015). ‘The Emergence of a New Party in the Italian Party System: Rise and Fortunes of the Five Star Movement’, West European Politics, 38:3, 516–34.

- Corredor, Elizabeth S. (2019). ‘Unpacking “Gender Ideology” and the Global Right’s Antigender Countermovement’, Signs, 44:3, 614–37.

- de Lange, Sarah, and Lize Mügge (2015). ‘Gender and Right-Wing Populism in the Low Countries: Ideological Variations across Parties and Time’, Patterns of Prejudice, 49:1–2, 61–80.

- Dean, Jonathan, and Bice Maiguashca (2018). ‘Gender, Power, and Left Politics: From Feminization to “Feministization’, Politics & Gender, 14:3, 376–406.

- Dean, Jonathan, and Bice Maiguashca (2020). ‘Did Somebody Say Populism? Towards a Renewal and Reorientation of Populism Studies’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 25:1, 11–27.

- Dietze, Gabriele, and Julia Roth (eds.) (2020). Right-Wing Populism and Gender: European Perspectives and Beyond. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Donà, Alessia (2020). ‘What’s Gender Got to Do with Populism?’, European Journal of Women’s Studies, 27:3, 285–92.

- European Institute for Gender Equality (2022). ‘Gender Equality Index’, available at: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-equality-index/2022.

- Engeli, Isabelle, Christoffer Green-Pedersen, and Lars Thorup Larsen (eds.) (2012). Morality Politics in Western Europe: Parties, Agenda, and Policy Choices. London: Palgrave.

- Fangen, Katrine, and Inger Skjelsbæk (2020). ‘Special Issue on Gender and the Far Right’, Politics, Religion & Ideology, 21:4, 411–5.

- Farris, Sara R. (2017). In the Name of Women’s Rights: The Rise of Femonationalism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- FdI (2013). Le Sfide per L’Italia.

- FdI (2018). Il Voto Che Unisce L’Italia.

- FdI (2019). Programma Elezioni Europee.

- Garbagnoli, Sara (2016). ‘Against the Heresy of Immanence: Vatican’s ‘Gender’ as New Rhetorical Device against the Denaturalization of the Sexual Order’, Religion and Gender, 6:2, 187–204.

- Graff, Agnieszka, and Elżbieta Korolczuk (2022). Anti-Gender Politics in the Populist Moment. London: Routledge.

- Gwiazda, Anna (2021). ‘Analysing the “What” and “When” of Women’s Substantive Representation: The Role of Right-Wing Populist Party Ideology’, East European Politics, 37:4, 681–701.

- Htun, Mala, and S. Laurel Weldon (2010). ‘When Do Governments Promote Women’s Rights? A Framework for the Comparative Analysis of Sex Equality Policy’, Perspectives on Politics, 8:1, 207–16.

- Jaquette, Jane S. (ed.) (2009). Feminist Agenda and Democracy in Latin America. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Kampwirth, Karen (ed.) (2010). Gender and Populism in Latin America: Passionate Politics. State College: Penn State.

- Kantola, Johanna, and Emanuela Lombardo (2019). ‘Populism and Feminist Politics: The Cases of Finland and Spain’, European Journal of Political Research, 58:4, 1108–28.

- Kantola, Johanna, and Emanuela Lombardo (2021). ‘Populism and Feminist Politics’, International Political Science Review, 42:5, 561–4.

- Kioupkiolis, Alexandros (2019). ‘Late Modern Adventures of Leftist Populism in Spain: The Case of Podemos, 2014-2018’, in Giorgos Katsambekis and Alexandros Kioupkiolis (eds.), The Populist Radical Left in Europe. London: Routledge.

- Köttig, Michaela, Renate Bitzan, and Andrea Petö (2017). Gender and Far Right Politics in Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Kováts, Eszter (2018). ‘Questioning Consensus: Right-Wing Populism, anti-Populism, and the Threat of “Gender Ideology”’, Sociological Research Online, 23:2, 528–38.

- Lavizzari, Anna, and Zorica Siročić (2023). ‘Contentious Gender Politics in Italy and Croatia: Diffusion of Transnational anti-Gender Movements to National Contexts’, Social Movement Studies, 22:4, 475–93.

- Lavizzari, Anna, and Massimo Prearo (2019). ‘The anti-Gender Movement in Italy: Catholic Participation between Electoral and Protest Politics’, European Societies, 21:3, 422–42.

- Lombardo, Emanuela, and Elena Del Giorgio (2013). ‘EU Antidiscrimination Policy and Its Unintended Domestic Consequences: The Institutionalization of Multiple Equalities in Italy’, Women’s Studies International Forum, 39:1, 12–21.

- Lega Nord (2013). Programma Elezioni Politiche 2013.

- Lega (2018). Salvini Premier: La Rivoluzione Del Buonsenso.

- Maiguashca, Bice (2019). ‘Resisting the ‘Populist Hype’: A Feminist Critique of a Globalizing Concept’, Review of International Studies, 45:5, 768–85.

- M5S (2013). Programma.

- M5S (2018). Programma Affari Costituzionali.

- M5S (2019). Continuare x Cambiare Anche in Europa.

- Mudde, Cas (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, Cas (2017). ‘Populism: An Ideational Approach’, in Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul Taggart, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Pierre Ostiguy (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Populism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 27–47.

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (2015). ‘Vox Populi or Vox Masculini? Populism and Gender in Northern Europe and South America’, Patterns of Prejudice, 49:1–2, 16–36.

- Norocel, Ov Cristian, and Alberta Giorgi (2022). ‘Disentangling Radical Right Populism, Gender, and Religion: An Introduction’, Identities, 29:4, 417–28.

- Paternotte, David, and Roman Kuhar (2018). ‘Disentangling and Locating the “Global Right”: Anti-Gender Campaigns in Europe’, Politics and Governance, 6:3, 6–19.

- Pirro, Andrea L. P. (2014). ‘Populist Radical Right Parties in Central and Eastern Europe: The Different Context and Issues of the Prophets of the Patria’, Government and Opposition, 49:4, 600–29.

- Pirro, Andrea L. P. (2018). ‘The Polyvalent Populism of the 5 Star Movement’, Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 26:4, 443–58.

- Pirro, Andrea L. P., and Stijn van Kessel (2018). ‘Populist Eurosceptic Trajectories in Italy and The Netherlands during the European Crises’, Politics, 38:3, 327–43.

- Podemos (2015). Queremos, Sabemos, Podemos.

- Podemos (2016). 26.J.

- Podemos (2019a). Las Razones Siguen Intactas.

- Podemos (2019b). Documento de Feminismos.

- Podemos (2019c). Documento Ético.

- Podemos (2019d). Documento Organizativo.

- Podemos (2019e). Documento Político.

- Prearo, Massimo (2020). L’Ipotesi Neocattolica: Politologia Dei Movimenti Anti-Gender. Milano: Mimesis.

- Puar, Jasbir (2013). ‘Rethinking Homonationalism’, International Journal of Middle East Studies, 45:2, 336–9.

- Rama, José, Lisa Zanotti, Stuart J. Turnbull-Dugarte, and Andrés Santana (2021). VOX: The Rise of the Spanish Populist Radical Right. Boca Raton: Routledge.

- Rooduijn, Matthijs, Stijn van Kessel, Caterina Froio, Andrea L. P. Pirro, Sarah de Lange, Daphne Halikiopoulou, Paul Lewis, Cas Mudde, and Paul Taggart (2019). The PopuList: An Overview of Populist, Far Right, Far Left and Eurosceptic Parties in Europe. www.popu-list.org.

- Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal, Paul Taggart, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Pierre Ostiguy (eds.) (2017). The Oxford Handbook of Populism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sledzińska-Simon, Anna (2020). ‘Populists, Gender, and National Identity’, International Journal of Constitutional Law, 18:2, 447–54.

- Snow, David A., and Robert D. Benford (1988). ‘Ideology, Frame Resonance, and Participant’s Mobilization’, in Bert Klandermans, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Sidney Tarrow (eds.), From Structure to Action: Social Movement Participation across Cultures. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 197–217.

- Spierings, Niels, Andrej Zaslove, Liza Mügge, and Sarah de Lange (2015). ‘Gender and Populist Radical-Right Politics: An Introduction’, Patterns of Prejudice, 49:1–2, 3–15.

- Taggart, Paul (2000). Populism. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Taggart, Paul, and Andrea L. P. Pirro (2021). ‘European Populism before the Pandemic: Ideology, Euroscepticism, Electoral Performance, and Government Participation of 63 Parties in 30 Countries’, Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica, 51:3, 281–304.

- Valiente, Celia (2008). ‘Spain at the Vanguard in European Gender Equality Policies’, in Silke Roth (ed.), Gender Politics in the Expanding European Union: Mobilization, Inclusion, Exclusion. New York: Berghahn.

- Verloo, Mieke, and David Paternotte (2018). ‘Special Issue: The Feminist Project under Threat in Europe’, Politics and Governance, 6:3, 1–5.

- VOX (2014a). Manifiesto Fundacional.

- VOX (2014b). Compromiso Por la Vidas y Los Valores.

- VOX (2015a). Tu Voz en el Congreso: Programa Electoral.

- VOX (2015b). Asuntos Sociales: Capitulo 1: Derecho a la Vida y Aborto Cero.

- VOX (2015c). Asuntos Sociales: Capitulo 2 y 3: Familia, Demografia y Natalidad.

- VOX (2015d). Asuntos Sociales: Capitulo 4: Political de Igualdad.

- VOX (2015e). Asuntos Sociales: Capitulo 5: Violencia de Genero.

- VOX (2015f). Asuntos Sociales: Capitulo 6: Custodia Compartida.

- VOX (2016). Hacer España Grande Otra Vez.

- VOX (2019). 100 Medidas Para la España Viva.

- Walby, Sylvia (2006). ‘Gender Approaches to Nations and Nationalism’, in Gerard Delanty and Krishan Kumar (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Nations and Nationalism. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 118–28.

- Wodak, Ruth (2015). The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Yuval-Davis, Nira (1993). ‘Gender and Nation’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 16:4, 621–32.

- Yuval-Davis, Nira (2008). ‘Citizenship, Territoriality and the Gendered Construction of Difference’, in Neil Brenner, Bob Jessop, Martin Jones, and Gordon MacLeod (eds.), State/Space: A Reader. Oxford: Blackwell, 309–25.