?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Rural areas have often been labelled by the literature as ‘left-behind’ areas or ‘places that don’t matter’, implicitly suggesting that residents of these communities feel neglected by political elites. This article studies the rural-urban divide in external political efficacy, which reflects individuals’ beliefs about the responsiveness of political elites, while also examining if compositional and contextual factors can explain such a divide. Drawing on data from the European Social Survey, the results reveal a significant rural-urban gap in external efficacy, which is partly explained by differences in the sociodemographic characteristics of rural and urban dwellers, but not by disparities in their evaluation of the provision of basic public services. Notably, this rural-urban gap in external efficacy is substantively smaller in those countries with higher levels of electoral malapportionment that lead to an overrepresentation of rural areas in national parliaments.

Out of the four cleavages discussed in Lipset and Rokkan’s (Citation1967) seminal work, the rural-urban divide is probably the one that has received the least attention in empirical political science (c.f. Knutsen Citation1989; Kriesi Citation1998; Tarrow Citation1971). Recent events such as Brexit, the Yellow Vests movement in France, or the growing and clustered support for populist radical right parties in Europe have led to a renewed interest in this traditional cleavage (see e.g. Harteveld et al. Citation2022).

The acceleration of the processes linked to globalisation has accentuated the gap between the countryside and the city, which goes well beyond demographic and economic aspects (Cramer Citation2016). This has led to the conjecture that those who live in rural areas resent urban dwellers and elites, among other reasons, because they feel like they have been abandoned by them. Underlying this claim is the assumption that urban and rural dwellers differ in their evaluation of the responsiveness of political elites, and more broadly the political system. In fact, rural areas have often been labelled by the literature as ‘left-behind’ areas (Ulrich-Schad and Duncan Citation2018) or ‘places that don’t matter’ (Rodríguez-Pose Citation2018). This, in turn, has been proposed as a potential explanation for the anti-establishment reactions that have emerged from some rural areas. It is, therefore, relevant to ask whether the apparently growing rural-urban political divide is manifested in different attitudes towards the political system in urban and rural areas.

The attention devoted to this topic in the empirical literature is swiftly growing but still scarce. Some of these studies have focused on examining differences in satisfaction with democracy and political trust between urban and rural inhabitants (McKay et al. Citation2021; Mitsch et al. Citation2021; Traunmüller and Ackermann Citation2019). In this article we focus instead on individuals’ perception of political responsiveness or external political efficacy, which is directly related to the notion of being ‘left behind’ (see also McKay Citation2019). Specifically, we analyse whether there are differences in external political efficacy between rural and urban dwellers. Prior evidence regarding the attitudinal and behavioural divides between these areas leads us to expect that the perception of external efficacy will be lower in the countryside. That is, that those living in those areas are likely to feel that politicians are less responsive to their demands.

In order to understand this rural-urban divide in political attitudes we build on the debate about compositional and contextual factors (Maxwell Citation2019). Thus, we propose two different, but potentially complementary, mechanisms that shed light on the extent to which the sociodemographic traits of the population in each area and/or the characteristics of the place itself are what explains this gap. The first mechanism is related to the observation that people with higher educational and economic levels tend to increasingly concentrate in cities (Maxwell Citation2019) and that these characteristics, in turn, are associated with higher levels of perceived external political efficacy (Oser et al. Citation2023). When it comes to the second mechanism, we focus on the evaluation of the provision of public services. Rural inhabitants often complain that they do not have equal access to high-quality public services, which translates into a perception that the elites are not paying attention to their needs and demands (Cramer Citation2016).

In addition, we propose that this relationship should be conditioned by institutions and the distribution of power in each country – specifically by how inclusive institutions are to rural representation. Hence, we assess whether the perceived external efficacy gap between urban and rural areas is smaller in those countries with higher levels of electoral malapportionment, which leads to an overrepresentation of rural areas in national parliaments.

Our analyses, based on data from rounds 8 and 9 of the European Social Survey for 30 countries, reveal that those who live in cities feel more politically efficacious. In other words, they think that the political system is more responsive to their demands. The results also reveal that the gap in perceived external political efficacy between rural and urban communities is not explained by a different evaluation of the provision of basic public services (e.g. healthcare or education) in these areas. Instead, this gap is partially explained by differences in the sociodemographic characteristics of rural and urban dwellers (i.e. a compositional mechanism). Moreover, it appears that the gap in perceived external efficacy is substantively smaller in those countries with higher levels of electoral malapportionment, which lead to an overrepresentation of rural communities in national parliaments.

These findings indicate that a crucial factor in understanding the rural-urban divide lies in the feeling of being neglected by political elites, a feeling particularly prevalent among rural residents. Moreover, to understand these processes it is not enough to consider the patterns of demographic segregation associated with the knowledge economy. The trajectory and the institutional make-up of each territory also seem to be relevant. This idea connects with the call from recent studies to investigate contextual factors, beyond the economic development of the territory, to fully understand the rural-urban divide (Kenny and Luca Citation2020; Luukkonen et al. Citation2021; Traunmüller and Ackermann Citation2019). Our finding regarding the role of electoral malapportionment highlights the relevance of institutions in shaping this increasingly important cleavage.

Theoretical framework

The rural-urban divide in political attitudes and behaviour has recently received increasing attention in the literature (e.g. Brookes and Cappellina Citation2023; Gimpel et al. Citation2020; Huijsmans et al. Citation2021; Roy et al. Citation2015; Scala and Johnson Citation2017; Zumbrunn and Freitag Citation2023). The key takeaway from these recent studies is that there is a stark attitudinal and behavioural contrast between urban and rural areas.

On the one hand, urban areas tend to be more cosmopolitan, more supportive of European integration, and more culturally progressive. Rural dwellers are, by contrast, more conservative and nationalistic, and tend to harbour greater political resentment and discontent, which in turn prompts some anti-system responses (de Dominicis et al. Citation2020; Huijsmans et al. Citation2021; Luca et al. Citation2022; Maxwell Citation2019). Rural and urban communities are, therefore, generally depicted as two worlds that are increasingly drifting apart due to, among other factors, the growing societal divides brought by the transition to knowledge economies. It seems that there is a growing divide between rural and urban residents across several political dimensions.

Against this backdrop, we propose to focus on individuals’ perception of their external political efficacy. Campbell et al. (Citation1954: 187) define political efficacy as the ‘feeling that individual political action does have, or can have, an impact upon the political process, namely, that it is worthwhile to perform one’s civic duties’. During the 1960s, efficacy became one of the prime factors to explain political participation and political behaviour (Craig Citation1979). In the following decade, though, the ambiguity of the concept and its dimensionality became the focus of discussion (Balch Citation1974). This debate exemplifies how research on the rural-urban cleavage can benefit from focusing on subjective external political efficacy. There is now a consensus on the idea that we can distinguish between two dimensions of political efficacy depending on whether the focus is placed on: the individual, as an actor that is capable of influencing politics; or on institutions, as organisations that are receptive and open to citizens’ demands (Westholm and Niemi Citation1986). Internal efficacy refers to the individual feeling about one’s own capacity to understand and participate in politics (Balch Citation1974; Craig Citation1979; Saris and Torcal Citation2009). Instead, external efficacy, or system responsiveness, refers ‘to beliefs about the responsiveness of governmental authorities and institutions to citizen demands’ (Craig et al. Citation1990: 290).

We would argue that, given previous arguments about rural areas being left behind, research on this cleavage can truly benefit from focusing on external political efficacy. The idea of rural communities feeling ignored by political elites is often an implicit assumption in this literature strand. However, this is one of the pillars that structures Cramer’s argument about rural consciousness (2016): the perception of not having influence, because politicians, by not listening to rural inhabitants, are showing them that they are not worthy of their attention. Studying external political efficacy, which focuses precisely on the perceived responsiveness of elites, is, therefore, a good way to shed some light on this crucial assumption of this literature strand.

While the distinction between internal and external efficacy is well established, we must also discuss its similarities and differences with another related concept such as political trust, which has been extensively analysed in the rural-urban cleavage literature (see e.g. McKay et al. Citation2021; Mitsch et al. Citation2021). As Craig (Citation1979) points out, both attitudes are based on the same object: the assessment of the system and its institutions. Hence, the two attitudes are closely related (Saris and Torcal Citation2009). However, they do not measure the same. Political trust is based on the perception of institutions acting in accordance with the pursuit of the public interest (e.g. absence of corruption), while external political efficacy relates to the perception of governments or institutions acting in line with citizens’ needs and demands (Craig et al. Citation1990). Therefore, people can trust an institution (e.g. technocratic government), which pursues the public interests, but in turn can feel less efficacious precisely because that institution is not responsive or necessarily guided by citizens’ needs and demands (Geurkink et al. Citation2020; McKay et al. Citation2021). In fact, regarding rural areas, Cramer (Citation2016) points out that the discontent is not only due to mistrust in the government, but also due to the lack of attention to their concerns.

The literature on the rural-urban divide has focused much more on electoral behaviour than on the study of the political attitudes that precede it, though (Luukkonen et al. Citation2021). In fact, behind the mobilisation and political reactions of certain rural areas there seems to be a feeling of being ignored or excluded. In line with this idea some recent studies point out that there are relevant differences in political support between urban and rural areas (e.g. Kenny and Luca Citation2020; McKay et al. Citation2021; Mitsch et al. Citation2021; Traunmüller and Ackermann Citation2019). Generally, rural inhabitants show lower levels of satisfaction with democracy and political trust than urban dwellers.

Luukkonen et al.’s (Citation2021) geographical study, in fact, points out that urban dwellers present higher levels of political efficacy than rural dwellers. Indirectly, this, and other attitudinal differences, have been attributed to a reaction from the countryside in face of a reality in which power is concentrated in cities, which are the clear winners of globalisation and benefit from the changes brought by the transition to knowledge economies (Cramer Citation2016; Rodríguez-Pose Citation2018). This has led to the assumption that the rural-urban attitudinal and behavioural divides can be traced back to the fact that residents in rural areas might feel ‘left behind’. Cities are not only the clear winners of knowledge economies, increasingly attracting capital and highly qualified workers that concentrate in small clusters, but are also the areas where political power is concentrated (Musterd et al. Citation2016). Moreover, due to their higher population density, basic public services such as hospitals, universities, or cultural infrastructures are generally concentrated in those areas. These phenomena, that can be grouped under the label of ‘political cityism’, imply the privileging of cities and urban areas to the detriment of rural areas’ interests (Luukkonen et al. Citation2021).

In comparison to those who live in rural areas, urbanites might, therefore, be more likely to perceive that political elites care about their needs and are more responsive to their demands. This perception might, in turn, lead to some of the attitudes and behaviours that have been observed among rural dwellers such as lower levels of trust in political elites (McKay et al. Citation2021), higher dissatisfaction with democracy (Traunmüller and Ackermann Citation2019), higher polarisation, or higher support for populist and radical right parties (Scala and Johnson Citation2017). Therefore, it seems pertinent to examine whether and to what extent rural dwellers feel that politicians are less responsive to their demands.

Following this reasoning we expect that:

H1: Urban dwellers will have a stronger feeling of external political efficacy than rural dwellers.

Compositional factors

The first mechanism that could lead to the rural-urban gap in perceived external political efficacy is related to compositional factors. That is, disparities in the composition of the respective dwellers. In addition to being associated with gender (Coffé Citation2013) and age (Marx and Nguyen Citation2016), political efficacy is closely related to factors such as educational attainment (Hakhverdian et al. Citation2012), occupation (Marx and Nguyen Citation2016; Westholm and Niemi Citation1986), and socioeconomic status (Metzger et al. Citation2020). A higher educational and socioeconomic status translate into a greater accumulation of both social and cognitive resources that facilitate access to the political world, which explains why high status groups perceive that the system is more permeable to their demands (Hakhverdian et al. Citation2012; Rosenstone and Hansen Citation1993). Likewise, those who are in a disadvantaged position, both in terms of employment and income, are more likely to feel that the outputs of the political system do not benefit them, which leads to a lower sense of external political efficacy (Emmenegger et al. Citation2015; Norris Citation2015).

Education, occupational status, and socioeconomic status are not equally distributed, though. Transformations associated with the transition to the knowledge economy have led to demographic segregation (Camarero Citation2020). That is, they have led to a heterogeneous spatial distribution of the population according to, for example, their level of education. People with more skills and a high occupational status are concentrated in large cities, because these accumulate more opportunities linked to the development of the service sector and knowledge economies. Meanwhile, the decline of the primary and secondary sectors is gradually relegating manual workers, with a lower educational level and higher unemployment rates, to rural areas (Kenny and Luca Citation2020; Maxwell Citation2019). Consequently, depopulation processes lead to older and more masculinised societies, with higher rates of school failure and people at risk of poverty, and with lower levels of social capital (Camarero Citation2020). Furthermore, segregation could be reinforced by a self-selection mechanism related to the fact that people tend to surround themselves with their equals and peers (Kenny and Luca Citation2020).

The gap between residents of rural and urban areas in terms of perceived external political efficacy could then be explained by compositional factors – age, gender, educational level, occupational status, etc. If this was the case, the driving force for the differences in political efficacy would not be the place or residence by itself, but the sociodemographic characteristics of residents in rural and urban areas. In this sense, Traunmüller and Ackermann (Citation2019) provide evidence about the relevance of compositional factors – and, specifically, educational level – when it comes to understanding the rural-urban gap in satisfaction with democracy. In general, this approach has so far been the predominant one when investigating the rural-urban divide in political dissatisfaction, populist attitudes, and voting behaviour (Kenny and Luca Citation2020) and when researching on political efficacy (Shore Citation2020). From this theoretical reasoning we derive our second hypothesis:

H2: Differences in sociodemographic characteristics will contribute to the gap in perceived external political efficacy between urban and rural dwellers.

Public services provision

Beyond compositional factors, differences in the provision of basic public services in cities and the countryside could also contribute to the gap in political efficacy. Although the effect of an individual’s socio-political context on the development of her political efficacy has not received much academic attention, ‘the idea that public policy can play an important role in shaping patterns of political engagement is by no means a new one’ (Shore Citation2020: 3).

There is solid evidence about the importance of the perception of the quality of the system’s outputs when evaluating its performance (Agerberg Citation2017; Bland et al. Citation2023). As Agerberg (Citation2017) points out, there is a consensus on the positive association between the quality of government and political trust. Specifically, citizens judge the quality of the system based on their closest experience, on the outputs that affect them the most, like, for example, the provision of public services such as education or healthcare and, more broadly, economic prosperity (Agerberg Citation2017; Cramer Citation2016; Mitsch et al. Citation2021). In this sense, there is evidence about the relationship between both the perception of the provision of services and political participation, and between the former and support for populist parties (Agerberg Citation2017). In addition, citizens’ negative perceptions about the provision of public services are linked to lower levels of political trust (Mitsch et al. Citation2021).

The levels of public investment and provision of public services are often insufficient in rural areas, a situation that has become chronic and that is detrimental for rural dwellers, especially among those groups and citizens with greater difficulties to move around the territory (Aksztejn Citation2020; Metzger et al. Citation2020). To the extent that their inhabitants often must travel far to continue studying or to receive advanced medical treatments, the demands arising from rural areas are usually based on the improvement of public services (Cramer Citation2016; Nilsson and Lundgren Citation2019). According to the policy feedback approach, public policies produce ‘resource effects’ and ‘interpretive effects’ (Pierson Citation1993). Although policies can distribute (material, economic) resources that have repercussions on what we have called compositional factors, it is the interpretive effects of these policies that can potentially influence one’s feeling of external political efficacy the most (Shore Citation2020). Moreover, the translation into resources, policies and investment in public policies send powerful messages. That is, a certain public policy ‘may signal to individuals or groups that they have rights to certain benefits or services, that they are entitled to and deserving of support’ (Shore Citation2020: 4). In the case of rural inhabitants, the difficulty in accessing certain public services is the seed for perceiving inequality compared to other citizens (Camarero Citation2020). In fact, this is one of most frequent claims of rural social movements such as the ‘Emptied Spain’ or the ‘Yellow Vests’ (Camarero Citation2022).

The economic and social decline linked to the rural exodus and deindustrialisation has, in fact, spread out a perception of marginalisation and a feeling of dissatisfaction with the system among its dwellers (McKay et al. Citation2021). It is at this point that the grievance, as a consequence of interpretive effects, comes into play: rural people’s attitudes towards who distributes the resources become more negative when they know that others are in a better situation (McKay Citation2019). It is common for the inhabitants of rural areas to feel forgotten, abandoned, or ignored by an elite that often adopts decisions from cities located far away. As Cramer (Citation2016) point out, this feeling of comparative grievance, together with an evocation of a better past, can crystallise into rural resentment. The consequences of this ‘territorial satellitization’ (Camarero Citation2020) have led to the notions of ‘left-behind places’ (Ulrich-Schad and Duncan Citation2018), ‘places that don’t matter’ (Rodríguez-Pose Citation2018) and the ‘geography of discontent’ (McCann Citation2020). These arguments lead us to our third hypothesis:

H3: Differences in perceptions of the provision of public services will contribute to the gap in perceived external political efficacy between urban and rural dwellers.

Malapportionment

While compositional differences and variation in the provision of public services can generate a gap in external efficacy between urban and rural dwellers, the extent to which institutions are able to integrate minority voices can ameliorate or exacerbate this efficacy divide. For example, consensual democratic systems can help increase satisfaction and perceived external political efficacy among electoral ‘losers’ and political minorities (Anderson and Guillory Citation1997; Banducci et al. Citation1999).

We, therefore, expect that being better represented in the policymaking process will play a role in the formation and change of feelings of external political efficacy. For example, among ethnic minorities, greater descriptive representation is related to higher levels of political efficacy. Having representatives of their same ethnicity or nationality empowers minorities in political terms, who believe that they have greater influence (Bobo and Gilliam Citation1990).

Precisely because voting is, par excellence, the way to exert influence in a democracy, it is necessary to consider the role that the electoral system might play in this regard, since some disproportionality mechanisms, such as malapportionment (Gallagher Citation1991), may alter the perception of external political efficacy of certain groups. In other words, perceived external political efficacy can be altered if one’s vote is worth more or less than another one depending on the area where one lives.

In some electoral systems, there is a ‘discrepancy between the shares of legislative seats and the shares of population held by geographical units’ (Samuels and Snyder Citation2001: 652). This bias is known as malapportionment. In other words, in the presence of malapportionment, the weight of each vote, in terms of representation and influence, is not equal across electoral districts. This is because, according to their population share, some districts are overrepresented, while others are underrepresented.

Jacob (Citation1964: 257), in fact, refers to malapportionment as ‘urban underrepresentation’, since it has ‘usually [involved] the deliberate over-representation of rural areas’ (Gallagher Citation1991: 45). This is partly because cities and metropolitan areas are generally gaining population, while the countryside is emptying. In fact, malapportionment can be understood as a compensation tool for the sake of a greater territorial balance; since, should this bias not exist, the most depopulated (i.e. rural) areas, would hardly have a voice (Simón Citation2009).

Malapportionment clearly benefits the rural and less populated areas, and the parties that represent the interests of those areas (Penadés Citation2006: 195). These overrepresented areas have an increased capacity to influence and condition decision-making, since malapportionment ‘can have an important impact on executive-legislative relations, intra-legislative bargaining and the overall performance of democratic systems’ (Samuels and Snyder Citation2001: 653). Because obtaining a seat for an overrepresented district costs fewer votes, political parties will work harder to win votes in these areas (Simón Citation2009). Thus, it makes sense that rural inhabitants may perceive that the system is more responsive to their demands. Specifically, this could be explained through two interlinked mechanisms that we propose but that we do not test below.

In the first place, malapportionment can generate a symbolic effect for rural inhabitants. They feel that they are more decisive, that their representatives are going to pay more attention to them, that they are going to give more voice to their demands. In short, in the presence of malapportionment rural sentiments and interests enjoy greater symbolic representation than urban ones (Lago and Montero Citation2005: 334). Secondly, precisely because of the electoral interest of the parties in these areas, the representatives of rural areas can exercise their greatest influence to obtain benefits for these areas. In fact, Ardanaz and Scartascini (Citation2013) propose that malapportionment has translated into a bias in the territorial distribution of public expenditure, benefiting rural areas, in various regions. In this way, it could be understood that being a beneficiary of the system’s outputs makes rural dwellers perceive that they are more influential. Based on these insights, we expect that differences in malapportionment across countries will modulate the gap in perceived external political efficacy between rural and urban areas. If malapportionment is high, rural areas are likely to be overrepresented in decision making bodies. In that case, the votes of rural dwellers weigh more than those of urbanites. This could lead to a higher sense of external political efficacy among rural dwellers, which might partially compensate for their lower provision of public services or even for the differences induced by compositional factors. Conversely, in countries with low or no malapportionment rural dwellers might feel that their voices are less likely to be heard. This argument leads us to our fourth hypothesis:

H4: The greater the degree of malapportionment, the smaller the perceived external political efficacy gap between urban and rural dwellers.

Data and methods

In order to test these hypotheses, we draw on data from rounds 8 and 9 of the European Social Survey (ESS), conducted in 2016 and 2018 in 30 European democracies.Footnote1 Our dependent variable measuring external political efficacy is based on two questions. The first asks respondents to what extent they think that the political system allows people to have a say in what governments does. The second question captures to what extent they think that the political system allows people to have influence in politics. Both items are measured on 5-point agreement scales. These two questions are adequate to capture and measure the latent concept of perceived external political efficacy in comparative studies (Saris and Torcal Citation2009).Footnote2 Our dependent variable is based on the combination of the responses to these two questions (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79). The resulting additive index, after recoding the items into a 0–4 scale, ranges between 0 and 8, with higher values indicating higher levels of perceived external political efficacy.

In order to measure whether respondents live in an urban or rural community, we rely on a self-reported measure. Respondents were asked to describe the place where they live with the following response categories: ‘A big city’; ‘Suburbs or outskirts of big city’; ‘Town or small city’; ‘Country village’; ‘Farm or home in countryside’. To simplify the estimation, we collapsed the first two categories into a single urban category, and the last two categories into a rural category. Hence, the resulting variable has three categories: urban, town, and rural. The intermediate category town allows us to nuance the rural-urban difference, which is more of a continuum (Nemerever and Rogers Citation2021). In addition, the use of these three categories is common in objective indicators, such as the DEGURBA or degree of urbanisation indicator (Eurostat Citation2021). While self-reported measures of rural-urban residence are not free of problems (Nemerever and Rogers Citation2021), this is the only measure often available in comparative surveys and it has been used extensively in the recent literature on the rural-urban divide (see e.g. Traunmüller and Ackermann Citation2019).

To capture the mechanism related to compositional factors, our models include variables measuring respondents’ sex, age (in years), education (measured in years of schooling), citizenship, income (measured subjectively on a 1–4 scale as how respondents think they are coping on with their current income), and an indicator variable capturing whether respondents have a paid job.

To measure the mechanism related to the provision of public services, our models include variables capturing how satisfied, on a 0–10 scale, respondents are with the state of education and healthcare in their countries. Although asking about satisfaction with services at the national level is not optimal for our purpose, most comparative surveys do not include this question at the local level. Moreover, to fully capture the potential influence of government’s output on the relationship between urban and rural residence and political efficacy we also include a variable measuring respondents’ evaluation of the state of the economy in their countries.

Another key variable of interest is the degree of malapportionment in each country. The country-level measure of malapportionment is based on Ong et al. (Citation2017), who create an original and up-to-date dataset of malapportionment for 160 countries using data for the latest available election in each country. They use the malapportionment index proposed by Samuels and Snyder (Citation2001), which is based on a modification of Loosemore and Hanby’s (Citation1971) disproportionality index of the mismatch between the proportion of seats and the proportion of votes obtained by a candidacy. As noted, malapportionment refers to the mismatch between the percentage of seats that are elected in a district and the percentage of the population residing in it (Samuels and Snyder Citation2001). Thus, the widely used formula to measure the level of malapportionment is as follows:

where si and vi are, respectively, the percentage of elected seats and the percentage of resident population in district i (Samuels and Snyder Citation2001).Footnote3

According to this formula, the resulting percentage would correspond to the total deviation of all the districts with respect to what would be a perfect apportionment (Ardanaz and Scartascini Citation2013). For instance, if the resulting value of the malapportionment index is 0.2, this means that one fifth of the representatives are elected in districts that would not correspond to them if there were proportionality between the distribution of seats and population. The measure mimics the one proposed by Samuels and Snyder (Citation2001), with higher values indicating higher levels of malapportionment. In our sample, the countries with the lowest levels of malapportionment are Israel, Montenegro, the Netherlands, Serbia, and Slovakia, which receive a value of 0 in the malapportionment index due to their single-district electoral system. The countries with the highest levels of malapportionment are Cyprus (0.172), Spain (0.106), and Iceland (0.091).

Our analyses also include a control variable that measures whether the respondent is an electoral winner or loser.Footnote4 According to previous literature, being a winner or loser affects the levels of perceived external political efficacy, since those who have voted for a party in government feel that institutions are more responsive to their preferences and demands than those who have voted for other political options (Nadeau and Blais Citation1993). To this end, we use a variable that measures which party the respondent voted for in the last election. Based on ParlGov data, the variable takes the value 0 when she is a loser, while the value 1 is assigned to winners.

In order to estimate our models,Footnote5 we implement a twofold strategy. Our initial examination of the gap in political efficacy between urban and rural dwellers, as well as of the potential mechanisms, that might drive this relationship is exclusively based on individual-level data. Hence, these models are based on an OLS estimation, which includes country-round fixed-effects to account for any unexplained variance across countries and ESS waves. Second, to analyse how malapportionment might moderate the gap in political efficacy between rural and urban dwellers we estimate a series of multilevel (mixed-effects) linear models. These models include country random-intercepts as well as random slopes for the individual-level variable measuring whether respondents live in an urban area, a town, or a rural area, which is interacted with each country’s degree of malapportionment (Heisig and Schaeffer Citation2019). These multilevel models also include wave fixed-effects.

Results

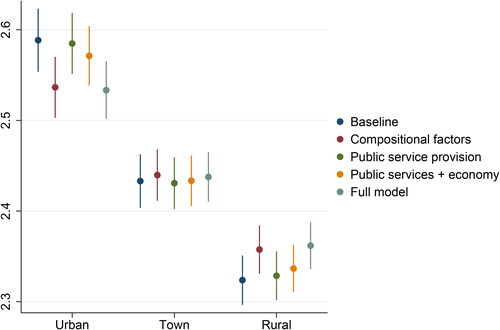

We begin by discussing the results related to the gap in political efficacy between rural and urban areas. Model 1 in reveals that, prior to including any controls, there are significant differences in perceived external political efficacy between those living in urban areas (reference category) and those who live in towns and rural areas, who feel less efficacious than those who live in cities. Those who live in urban areas have an average level of perceived external efficacy of 2.59, those who live in towns of 2.43 and those who live in rural areas of 2.32. As expected, we find the greatest difference in perceived external efficacy between those who live in urban areas and those who live in rural areas, where the difference amounts to 0.265 points on the 0–8 scale. This gap is equivalent to a change of 0.15 standard deviations in the perceived external efficacy index.

Table 1. Rural-urban differences in perceived external political efficacy.

Next, we analyse whether and to what extent differences in perceived external efficacy between urban and rural areas are driven by compositional mechanisms. As shown in Table A1 of the Online appendix, rural and urban populations show statistically significant differences in their sociodemographic profile. Compared to urbanites, among rural inhabitants there are more men, less immigrants, and more people with paid jobs. In addition, the rural population presents a higher average age, lower educational levels, and greater difficulties to live with their current income. To the extent that these sociodemographic factors are associated with feelings of external efficacy, such compositional differences may contribute to explain the rural-urban gap in efficacy.

Model 2 of includes the variables related to the respondents’ sociodemographic profile. According to the estimates, being a woman has a significant negative effect on the feeling of external political efficacy. The same happens with being older and having more difficulties to face the day to day with one’s current level of income. In contrast, there is a statistically significant positive relationship between years of schooling and the level of perceived external political efficacy. What is more relevant for our purposes, though, is how the impact of being an urban or rural dweller changes once sociodemographic differences are accounted for. When these variables are included in the model, the gap in political efficacy between urban and rural areas shrinks considerably. These changes can be better assessed in . For example, in the model including compositional factors, the difference in efficacy between urban and rural areas shrinks from 0.265 points to 0.179 points. This is a substantively relevant change that amounts to almost a third of the difference identified between these two areas through the unconditional baseline model (Model 1). In fact, if we analyse the effect of each sociodemographic variable separately, we see that education is, by far, the most influential: the gap in the perceived external political efficacy between urban and rural dwellers is reduced from 0.244 to 0.157 points.Footnote6 These results are consistent with the idea that differences in perceived external efficacy between urban and rural areas are partially linked to compositional mechanisms.

Figure 1. Predicted levels of perceived external efficacy by place of residence.

Note: Predicted values with 95% confidence intervals, based on estimates of .

We next assess the mechanism related to the provision of public services. As shown in Table A2 of the Online appendix, there are statistically significant differences in satisfaction with the provision of public services between urban and rural inhabitants. Regarding satisfaction with the educational system, the results go in the opposite direction to our expectations. That is, controlling for sociodemographic characteristics, both residents of towns and rural areas show higher levels of satisfaction than urbanites. On the other hand, urbanites are more satisfied with the health system than inhabitants of towns and rural areas, although the difference is statistically significant only in the latter case. In the case of satisfaction with the economy, we find the same statistically significant effect: rural inhabitants are more dissatisfied than urban dwellers.

Table 2. Multilevel mixed-effects linear model.

When respondents’ evaluations of the state of healthcare and education are included in the models, we find that being more satisfied both with the education and health systems is positively related to being more politically efficacious. What is more important for our purposes, though, is that this hypothesised mechanism does not seem to play a role in accounting for the gap between rural and urban areas. Model 3 in reveals that the rural-urban gap in political efficacy slightly decreases in this model, although the difference with respect to the unconditional model (Model 1) is of trivial magnitude. It does not appear that differences in satisfaction with the provision of basic services can explain differences in political efficacy between urban and rural dwellers.

In the fourth model, we include the evaluation of the state of the economy along with the evaluation of public services. This allows us to assess if beyond the provision of public services, a better evaluation of the economic situation might explain differences in efficacy between cities and villages. Being more satisfied with the state of the economy has a significant positive effect on the level of perceived external political efficacy. However, again, the estimate of the gap in political efficacy between rural and urban areas is somewhat reduced when comparing this estimation and the baseline model (Model 1), but the magnitude of the change is substantively negligible. Hence, we can conclude that differences in perceived external efficacy between urban and rural areas do not seem to be related to the different provision of basic public services in each of these areas. The last model in (Model 5) includes both variables related to compositional factors and those related to the evaluation of public services. In Table A5 of the Online appendix we include the same models as robustness checks without the winner/loser control variable. In this case, the gaps remain almost the same, with the coefficients being slightly lower.

The differences in perceived external political efficacy are more pronounced the more nuances are introduced in the measurement of the rural-urban axis. In Table A4 in the Online appendix, we distinguish the population of big cities from urban dwellers. To do this, we follow Maxwell’s (Citation2019) criterion: based on the regional classification in NUTS (Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics) provided by the ESS, we consider as inhabitants of an additional category, ‘big cities’, those respondents who live in the most populous metropolitan region of each country and who say they reside in a big city. Results indicate that they perceive themselves as more efficacious than rural and town dwellers, but also than other urban dwellers.

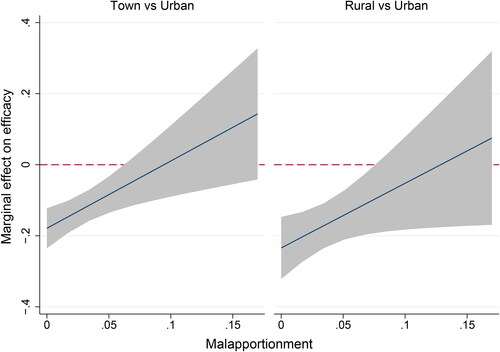

Once examined the mechanisms that might drive the differences in efficacy between cities and the countryside, we consider whether countries’ degree of electoral malapportionment moderates the impact of living in a city or in the countryside when it comes to perceived external political efficacy (hypothesis 4). The results of the multilevel mixed-effects linear model that we fit to test this argument are summarised in . The results of our baseline model (Model 1) when it comes to the differences in political efficacy between urban and rural areas are very similar to those obtained with the OLS specification summarised in . Interestingly, it appears that country’s degree of electoral malapportionment does not have a direct and statistically significant impact on individuals’ feeling of external political efficacy.

Model 2 of summarises the results of the specification including a cross-level interaction between the rural-urban residence individual-level indicator and electoral malapportionment at the country-level. This model, which includes control variables for all the individual-level variables included in Model 5 of , reveals that, as expected, countries’ degree of electoral malapportionment moderates the gap in perceived external political efficacy, at least when it comes to both the differences between urban areas and towns, and between urban areas and rural areas.

summarises this cross-level interaction. In countries with low or no malapportionment there is a significant and substantively relevant difference in perceived external efficacy, both between those living in urban areas and towns (left-hand panel) and between those living in urban areas and rural ones (right-hand panel). This difference in efficacy becomes smaller as levels of malapportionment – and, hence, the overrepresentation of rural areas – increase. Indeed, in those countries with the highest levels of electoral malapportionment, the differences in political efficacy between urban and rural zones are indistinguishable from zero. The pattern is similar for the difference between urban areas and towns and that between urban areas and rural areas. All in all, these results clearly suggest that the overrepresentation of rural areas in decision-making bodies can ameliorate or even eliminate the gap in political efficacy between cities and the countryside.

Figure 2. Differences in perceived external efficacy between rural and urban areas at different levels of malapportionment (country-level).

Note: Marginal effects with 95% confidence intervals, based on Model 2 of .

As a robustness-check, we have carried out additional analyses considering two other institutional characteristics related to the territorial distribution of power: the degree of decentralisation and bicameralism (see Tables A6 and A7 in the Online appendix). None of these variables was found to moderate the rural-urban in perceived external political efficacy, while malapportionment effect remains practically the same. This could be because, although all three are proxies for the territorial distribution of power, only malapportionment strictly entails the overrepresentation of rural areas.

Conclusion

This article contributes to the recent debate on the rural-urban divide in political attitudes and behaviours. Existing research has shown that a gap does exist and that, generally, rural dwellers are more dissatisfied and more likely to support anti-establishment political options than urbanites (e.g. de Dominicis et al. Citation2020; Kenny and Luca Citation2020; Luca et al. Citation2022; Mitsch et al. Citation2021). This has led to the notion that rural inhabitants feel left behind by the political elites, who neglect the interests and demands of rural areas.

In this article we put this assumption to a comprehensive test by exploring whether, why, and under which conditions rural inhabitants might feel that the political system is not responsive to their demands. This is why we have focused on perceived external political efficacy, since this is the attitude that best connects with the roots of rural discontent: the inhabitants of the countryside feeling ignored or less listened to. Indeed, in line with our first hypothesis, results show that, compared to rural inhabitants, urban dwellers have higher levels of external political efficacy. That is, they feel that the political system is more permeable and responsive to their preferences and demands.

We expected that this rural-urban gap in efficacy would be explained by the sociodemographic differences between urban and rural dwellers, as well as by differences in the provision of public services in these two areas. Our results indicate that the rural-urban divide in perceived external political efficacy is partially explained by differences in the sociodemographic characteristics of the population of each area. In contrast, we do not find empirical support for our third hypothesis, as the gap does not seem to be related to differences in the evaluation of public service provision – an argument with a strong media presence in some national debates about this phenomenon (Nilsson and Lundgren Citation2019). These results about the mechanisms are consistent with recent analysis of the rural-urban divide for other attitudes or behaviours, which also find support for the compositional explanation (Kenny and Luca Citation2020; Maxwell Citation2019; Traunmüller and Ackermann Citation2019).

Beyond the mechanisms driving this divide, our article has also explored how institutions might ameliorate or exacerbate the rural-urban gap in external political efficacy. We have focused on malapportionment, a key institutional feature that directly impacts on the representation of rural interests in legislative bodies. In line with our expectations, the rural-urban gap in perceived external political efficacy is moderated by electoral malapportionment. Hence, in those political systems in which rural areas are overrepresented in national parliaments, the gap in political efficacy is narrower.

This study’s contributions are threefold. First, we have placed external political efficacy at the centre of our theoretical and empirical models. Whereas in most of the existing literature the feeling of not being represented is an implicit element, in our article we directly tested if it is really the case that rural dwellers feel left behind by the political system (see also Luukkonen et al. Citation2021). We would argue that the rural-urban gap in perceived external political efficacy can help us to understand the divide in other political attitudes and behaviours (Daoust and Nadeau Citation2021; Mcevoy Citation2016; Oser et al. Citation2023; Sarsfield and Echegaray Citation2006). Thus, the fact that rural inhabitants feel neglected by political elites may contribute to explain their lower levels of political trust or satisfaction with democracy, as well as their greater electoral support for anti-establishment options through which they can channel their discontent.

Second, we examined the factors behind the attitudinal differences between urban and rural areas. Our results confirm the relevance of the compositional mechanism and defy the prevailing notion that differences in the provision of public services are the reason why rural inhabitants feel abandoned by political elites. Third, our study goes beyond these mechanisms and studies if institutional frameworks that integrate and give more voice to rural areas can ameliorate the perceived external efficacy gap. This clearly seems to be the case, which suggests that initiatives that increase the formal representation of rural interests in institutions might be a good tool to counteract the increasing political dissatisfaction from these areas.

In order to understand which institutional reforms may be more effective, it would be useful to further analyse the role played by other contextual factors, such as the size of electoral districts or the involvement of different levels of government in decision-making. Future research could also analyse and test the mechanisms that we propose in our theoretical framework to explain how malapportionment may reduce the rural-urban external efficacy gap. Likewise, it would be interesting to know if this gap exists at all levels of government. This line of research would also connect with the debate on the role of the regions and to what extent rural political discontent and that of peripheral regions are related (De Lange et al. Citation2023).

Despite our findings, other relevant contextual factors remain to be identified. This is undoubtedly a key issue to address in this literature strand. Another relevant limitation of our study has to do with the analysis of the evaluation of public services. It would be interesting to examine it with survey measures that gauge the evaluation of services at the local level or that involve a comparison with other areas (e.g. between urban and rural areas). Another relevant option would be to study both satisfaction with the provision of services and other indicators of living standards, such as economic growth or depopulation, that shed light on interpersonal and interterritorial inequalities (Rodríguez-Pose Citation2018) in time perspective. Political discontent may be greater in areas that have perceived a drop in quality of life than in those where the situation has always been just as bad (Rodríguez-Pose Citation2018), since rural resentment is related to the evocation of a better past (Cramer Citation2016). In any case, due to increased mobility and communication flows, comparisons with more prosperous areas and feelings of grievance are inevitable, so it seems clear that reforms are necessary – at the level of inputs (involvement in decision-making) and outputs (improved quality of life) – to reward rural areas.

The direction of causality is also a limitation of this research, especially when it comes to the two explanatory mechanisms. First, the place of residence can be chosen precisely based on sociodemographic characteristics due to the self-selection mechanism. Second, it may also be that perceived efficacy influences service satisfaction. Thus, in future research it would be advisable to have panel data, experimental data or objective data on the provision of services, which could help to overcome these problems.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (528.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and discussants of the 2021 AECPA Conference, of the ‘The Rural-Urban Divide in Europe’ workshop at the Goethe University Frankfurt, of the Barcelona PhD Workshop on Empirical Political Science 2021 (winter) at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, of the 2022 CES International Conference of Europeanists, of the NORFACE Governance Mid-term Conference, and of the Democracy, Elections and Citizenship seminars at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, as well as the West European Politics editors and reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions on previous versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rubén García del Horno

Rubén García del Horno is a doctoral candidate at the Department of Political Science at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. His research focuses on the rural-urban cleavage in political attitudes and behaviours. [[email protected]]

Guillem Rico

Guillem Rico is an Associate Professor at the Department of Political Science at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. His research interests are in the fields of political behaviour and public opinion. [[email protected]]

Enrique Hernández

Enrique Hernández is an Associate Professor at the Department of Political Science at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. He completed a PhD in Political and Social Sciences at the European University Institute in 2016. His main research interests are in political attitudes, public opinion, electoral behaviour and democracy. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 We limit our analyses to those countries that participated in at least one of the two rounds and can be classified as democratic: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

2 These questions, with the same formulation and the same response scale, are only available in waves 8 and 9 of the ESS. It is for this reason that this research does not include previous rounds.

3 For details on the variants of this formula in multi-tier electoral systems, see Samuels and Snyder (Citation2001).

4 In any case, in Table A5 in the Online appendix, we replicate our analyses without this control variable, as a robustness check.

5 All our models include analyses weights, as recommended by the ESS.

6 Table A3 in the Online appendix shows the separate effects of each of the sociodemographic characteristics on the rural-urban gap in perceived external political efficacy.

References

- Agerberg, Mattias (2017). ‘Failed Expectations: Quality of Government and Support for Populist Parties in Europe’, European Journal of Political Research, 56:3, 578–600.

- Aksztejn, Wirginia (2020). ‘Local Territorial Cohesion: Perception of Spatial Inequalities in Access to Public Services in Polish Case-Study Municipalities’, Social Inclusion, 8:4, 253–64.

- Anderson, Christopher J., and Christine A. Guillory (1997). ‘Political Institutions and Satisfaction with Democracy: A Cross-National Analysis of Consensus and Majoritarian Systems’, American Political Science Review, 91:1, 66–81.

- Ardanaz, Martín, and Carlos Scartascini (2013). ‘Inequality and Personal Income Taxation: The Origins and Effects of Legislative Malapportionment’, Comparative Political Studies, 46:12, 1636–63.

- Balch, George I. (1974). ‘Multiple Indicators in Survey Research: The Concept "Sense of Political Efficacy’, Political Methodology, 1:2, 1–43.

- Banducci, Susan A., Todd Donovan, and Jeffrey A. Karp (1999). ‘Proportional Representation and Attitudes about Politics: Evidence from New Zealand’, Electoral Studies, 18:4, 533–55.

- Bland, Gary, Derick Brinkerhoff, Diego Romero, Anna Wetterberg, and Erik Wibbels (2023). ‘Public Services, Geography, and Citizen Perceptions of Government in Latin America’, Political Behavior, 45:1, 125–52.

- Bobo, Lawrence, and Franklin D. Gilliam Jr. (1990). ‘Race, Sociopolitical Participation, and Black Empowerment’, American Political Science Review, 84:2, 377–93.

- Brookes, Kevin, and Bartolomeo Cappellina (2023). ‘Political Behaviour in France: The Impact of the Rural-Urban Divide’, French Politics, 21:1, 104–24.

- Camarero, Luis (2020). ‘Despoblamiento, Baja Densidad y Brecha Rural: un Recorrido por una España Desigual’, Panorama Social, 31, 47–73.

- Camarero, Luis (2022). ‘Los Habitantes de los Territorios de Baja Densidad en España. Una Lectura de las Diferencias Urbano-Rurales’, Mediterráneo Económico, 35, 45–66.

- Campbell, Angus, Gerald Gurin, and Warren E. Miller (1954). The Voter Decides. Evanston: Row, Peterson.

- Coffé, Hilde (2013). ‘Women Stay Local, Men Go National and Global? Gender Differences in Political Interest’, Sex Roles, 69:5–6, 323–38.

- Craig, Stephen C. (1979). ‘Efficacy, Trust, and Political Behavior: An Attempt to Resolve a Lingering Conceptual Dilemma’, American Politics Quarterly, 7:2, 225–39.

- Craig, Stephen C., Richard G. Niemi, and Glenn E. Silver (1990). ‘Political Efficacy and Trust: A Report on the NES Pilot Study Items’, Political Behavior, 12:3, 289–314.

- Cramer, Katherine J. (2016). The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Daoust, Jean-François, and Richard Nadeau (2021). ‘Context Matters: Economics, Politics and Satisfaction with Democracy’, Electoral Studies, 74, 102133.

- De Lange, Sarah, Wouter van der Brug, and Eelco Harteveld (2023). ‘Regional Resentment in The Netherlands: A Rural or Peripheral Phenomenon?’, Regional Studies, 57:3, 403–15.

- de Dominicis, Laura, Lewis Dijkstra, and Nicola Pontarollo (2020). ‘The Urban-Rural Divide in anti-EU Vote: Social, Demographic and Economic Factors Affecting the Vote for Parties Opposed to European Integration’, Working paper, 05/2020, 24.

- Emmenegger, Patrick, Paul Marx, and Dominik Schraff (2015). ‘Labour Market Disadvantage, Political Orientations and Voting: How Adverse Labour Market Experiences Translate into Electoral Behaviour’, Socio-Economic Review, 13:2, 189–213.

- Eurostat (2021). Applying the Degree of Urbanisation. A Methodological Manual to Define Cities, Towns and Rural Areas for International Comparisons. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union.

- Gallagher, Michael (1991). ‘Proportionality, Disproportionality and Electoral Systems’, Electoral Studies, 10:1, 33–51.

- Geurkink, Bram, Andrej Zaslove, Roderick Sluiter, and Kristof Jacobs (2020). ‘Populist Attitudes, Political Trust, and External Political Efficacy: Old Wine in New Bottles?’, Political Studies, 68:1, 247–67.

- Gimpel, James G., Nathan Lovin, Bryant Moy, and Andrew Reeves (2020). ‘The Urban–Rural Gulf in American Political Behavior’, Political Behavior, 42:4, 1343–68.

- Hakhverdian, Armen, Wouter van der Brug, and Catherine de Vries (2012). ‘The Emergence of a "Diploma Democracy"? The Political Education Gap in The Netherlands, 1971-2010’, Acta Politica, 47:3, 229–47.

- Harteveld, Eelco, Wouter van der Brug, Sarah de Lange, and Tom van der Meer (2022). ‘Multiple Roots of the Populist Radical Right: Support for the Dutch PVV in Cities and the Countryside’, European Journal of Political Research, 61:2, 440–61.

- Heisig, Jan Paul, and Merlin Schaeffer (2019). ‘Why You Should Always Include a Random Slope for the Lower-Level Variable Involved in a Cross-Level Interaction’, European Sociological Review, 35:2, 258–79. https://academic.oup.com/esr/advance-article/doi/10.1093/esr/jcy053/5306121.

- Huijsmans, Twan, Eelco Harteveld, Wouter van der Brug, and Bram Lancee (2021). ‘Are Cities Ever More Cosmopolitan? Studying Trends in Urban-Rural Divergence of Cultural Attitudes’, Political Geography, 86, 102353.

- Jacob, Herbert (1964). ‘The Consequences of Malapportionment: A Note of Caution’, Social Forces, 43:2, 256–61.

- Kenny, Michael, and Davide Luca (2020). ‘The Urban-Rural Polarisation of Political Disenchantment: An Investigation of Social and Political Attitudes in 30 European Countries’, LSE Europe in Question Discussion Paper Series, 161/2020.

- Knutsen, Oddbjørn (1989). ‘Cleavage Dimensions in Ten West European Countries: A Comparative Empirical Analysis’, Comparative Political Studies, 21:4, 495–533.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter (1998). ‘The Transformation of Cleavage Politics: The 1997 Stein Rokkan Lecture’, European Journal of Political Research, 33:2, 165–85.

- Lago, Ignacio, and José Ramón Montero (2005). ‘Todavía No Sé Quiénes, pero Ganaremos: Manipulación Política del Sistema Electoral Español’, Zona Abierta, 110–111, 279–348.

- Lipset, Seymour Martin, and Stein Rokkan, eds. (1967). Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York: Free Press.

- Loosemore, John, and Victor J. Hanby (1971). ‘The Theoretical Limits of Maximum Distortion: some Analytic Expressions for Electoral Systems’, British Journal of Political Science, 1:4, 467–77.

- Luca, Davide, Javier Terrero-Dávila, Jonas Stein, and Neil Lee (2022). ‘Progressive Cities: Urban-Rural Polarisation of Social Values and Economic Development around the World’, International Inequalities Institute III working paper, 74 http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/113458/1/III_WPS_progressive_cities_paper_74.pdf.

- Luukkonen, Juho, Mikko Weckroth, Teemu Kemppainen, Teemu Makkonen, and Heikki Sirviö (2021). ‘Urbanisation and the Shifting Conditions of the State as a Territorial-Political Community: A Study of the Geographies of Political Efficacy’, Transaction of the Institute of British Geographers, 00, 1–17.

- Marx, Paul, and Christoph Nguyen (2016). ‘Are the Unemployed Less Politically Involved? A Comparative Study of Internal Political Efficacy’, European Sociological Review, 32:5, 634–48.

- Maxwell, Rahsaan (2019). ‘Cosmopolitan Immigration Attitudes in Large European Cities: Contextual or Compositional Effects?’, American Political Science Review, 113:2, 456–74.

- McCann, Philip (2020). ‘Perceptions of Regional Inequality and the Geography of Discontent: Insights from the UK’, Regional Studies, 54:2, 256–67.

- Mcevoy, Caroline (2016). ‘The Role of Political Efficacy on Public Opinion in the European Union’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 54:5, 1159–74.

- McKay, Lawrence (2019). ‘"Left behind" People, or Places? The Role of Local Economies in Perceived Community Representation’, Electoral Studies, 60, 102046.

- McKay, Lawrence, Will Jennings, and Gerry Stoker (2021). ‘Political Trust in the “Places That Don’t Matter”’, Frontiers in Political Science, 3, 642236.

- Metzger, Aaron, Lauren Alvis, and Benjamin Oosterhoff (2020). ‘Adolescent Views of Civic Responsibility and Civic Efficacy: Differences by Rurality and Socioeconomic Status’, Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 70, 101183.

- Mitsch, Frieder, Neil Lee, and Elizabeth Ralph Morrow (2021). ‘Faith No More? The Divergence of Political Trust between Urban and Rural Europe’, Political Geography, 89, 102426.

- Musterd, Sako, Marco Bontje, and Jan Rouwendal (2016). Skills and Cities. London: Routledge.

- Nadeau, Richard, and André Blais (1993). ‘Accepting the Election Outcome: The Effect of Participation on Losers’ Consent’, British Journal of Political Science, 23:4, 553–63.

- Nemerever, Zoe, and Melissa Rogers (2021). ‘Measuring the Rural Continuum in Political Science’, Political Analysis, 29:3, 267–86.

- Nilsson, Bo., and Anna Sofia Lundgren (2019). ‘Morality of Discontent: The Constitution of Political Establishment in the Swedish Rural Press’, Sociologia Ruralis, 59:2, 314–28.

- Norris, Mikel (2015). ‘The Economic Roots of External Efficacy: Assessing the Relationship between External Political Efficacy and Income Inequality’, Canadian Journal of Political Science, 48:4, 791–813.

- Ong, Kian-Ming, Yuko Kasuya, and Kota Mori (2017). ‘Malapportionment and Democracy: A Curvilinear Relationship’, Electoral Studies, 49, 118–27.

- Oser, Jennifer, Fernando Feitosa, and Ruth Dassonneville (2023). ‘Who Feels They Can Understand and Have an Impact on Political Processes? Socio-Demographic Correlates of Political Efficacy in 46 Countries, 1996’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 35:2, 1–11.

- Penadés, Alberto (2006). ‘La Difícil Ciencia de los Orígenes de los Sistemas Electorales’, Revista de Estudios Políticos, 131, 193–218.

- Pierson, Paul (1993). ‘When Effect Becomes Cause: Policy Feedback and Political Change’, World Politics, 45:4, 595–628.

- Rodríguez-Pose, Andrés (2018). ‘The Revenge of the Places That Don’t Matter (and What to Do about It)’, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11:1, 189–209.

- Rosenstone, Steven J., and John Mark Hansen (1993). Mobilization, Participation, and Democracy in America. New York: Macmillan.

- Roy, Jason, Andrea M. L. Perrella, and Joshua Borden (2015). ‘Rural, Suburban and Urban Voters: Dissecting Residence Based Voter Cleavages in Provincial Elections’, Canadian Political Science Review, 9:1, 112–27.

- Samuels, David, and Richard Snyder (2001). ‘The Value of a Vote: Malapportionment in Comparative Perspective’, British Journal of Political Science, 31:04, 651–71.

- Saris, Willem E., and Mariano Torcal (2009). ‘Alternative Measurement Procedures and Models for Political Efficacy’, working paper 3, Research and Expertise Centre for Survey Methodology, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain.

- Sarsfield, Rodolfo, and Fabián Echegaray (2006). ‘Opening the Black Box: How Satisfaction with Democracy and Its Perceived Efficacy Affect Regime Preference in Latin America’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 18:2, 153–73.

- Scala, Dante J., and Kenneth M. Johnson (2017). ‘Political Polarization along the Rural-Urban Continuum? The Geography of the Presidential Vote, 2000–2016’, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 672:1, 162–84.

- Shore, Jennifer (2020). ‘How Social Policy Impacts Inequalities in Political Efficacy’, Sociology Compass, 14:5, e12784.

- Simón, Pablo (2009). ‘La Desigualdad y el Valor de un Voto: el Malapportionment de las Cámaras Bajas en Perspectiva Comparada’, Revista de Estudios Políticos, 143, 165–88.

- Tarrow, Sidney (1971). ‘The Urban-Rural Cleavage in Political Involvement: The Case of France*’, American Political Science Review, 65:2, 341–57.

- Traunmüller, Richard, and Kathrin Ackermann (2019). ‘The Rural-Urban Divide in Citizen Discontent’, Presented at the EPSA Meeting.

- Ulrich-Schad, Jessica D., and Cynthia M. Duncan (2018). ‘People and Places Left behind: Work, Culture and Politics in the Rural United States’, The Journal of Peasant Studies, 45:1, 59–79.

- Westholm, Anders, and Richard G. Niemi (1986). ‘Youth Unemployment and Political Alienation’, Youth & Society, 18:1, 58–80.

- Zumbrunn, Alina, and Markus Freitag (2023). ‘The Geography of Autocracy. Regime Preferences along the Rural-Urban Divide in 32 Countries’, Democratization, 30:4, 616–34.