?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

A surprising feature of Brexit has been the united front the EU-27 presented during post-referendum negotiations. This membership crisis arrived when the EU had been facing multiple overlapping political and economic crises revealing deep cleavages both between and within member states. How did negotiations prevent a widening politicisation of European integration? In this article a novel dataset is used, containing national and European newspaper Brexit coverage between 2016 and 2020 to establish how negotiating stances were formed in key EU institutions and five influential member states: Ireland, Spain, France, Germany and Poland. The results indicate that the European Commission could maintain a strong, centralised negotiating position over Brexit because the preferences of these member states were mutually inclusive, their negotiating stances aligned, and each national case was subject to generally low levels of domestic politicisation. As a result, while Brexit shocked the EU, its immediate fallout could be contained even during uncertain times.

The UK’s vote to leave the European Union (EU), triggering Brexit, arrived amid a series of crises in Europe. Economic shocks in banking and sovereign debt were followed by unprecedented refugee flows, combining for what former Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker (Citation2016), on the eve of the UK’s referendum, labelled a ‘polycrisis’. These crises became intensely politicised: they were salient but also polarising events for everyday Europeans. Domestic politicisation was uploaded to European negotiations, leading to splits between member states, and lasting scarring effects on EU politics even after the crises had been putatively addressed by policy (Hutter and Kriesi Citation2019; Kriesi et al. Citation2021).

Now, the EU was faced with the departure of its third-largest economy, second-largest net budget contributor and one of two major military powers. Brexit also came with no instruction sheet, its meaning and terms to be negotiated. Article 50 from the Treaty on European Union established a process, but its own architects admitted it was never intended to be used (Independent Citation2016), and there was early speculation that the Commission and Council were jostling for control (Politico Citation2016). Amid this uncertainty, the possibility that politicisation would spread across the EU-27 again was real. Eurosceptics already riding electoral waves initially enthusiastically welcomed the vote (van Kessel et al. Citation2020), and scholars imagined how Brexit might spark contagion and wider processes of differentiated disintegration (Schimmelfennig Citation2018). Rosamond’s (Citation2016: 865) prediction was stark: ‘within the EU system, Brexit is likely to unleash disintegrative dynamics, which could see the EU stagnate into a suboptimal institutional equilibrium’.

However, through the implementation of the Withdrawal Agreement on 1st February 2020, the EU27 showed cohesion throughout lengthy negotiations, the integrity of the European polity being maintained with members holding close to hard Commission negotiating objectives. Given widely varying political and economic relations between member states and the UK, plus the backdrop of recent divisive crisis management, such near total unity is puzzling (Jensen and Kelstrup Citation2019; Laffan Citation2019; Taggart et al. Citation2023). This article contributes to a growing literature addressing this puzzle, containing the disruptive potential of Brexit in a period otherwise defined by crisis salience, polarisation and inter-state division. It draws on a novel dataset of 2,928 hand-coded policy actions drawn from quality newspapers covering five diverse, influential member states – France, Ireland, Germany, Spain, Poland – plus major European institutions from the vote to the end of the transition period, 2016–2020. Reconstructing and interpreting the policy process this way, the article offers a uniquely detailed chronology of how an absence of politicisation on the EU-side provided for a ‘permissive consensus’ that is confounding for a simple post-functionalist account of EU crisis politics. While in the decades prior to the 1990s permissiveness enabled integration, with Brexit it prevented further disintegration.

A focus on policy actions reveals what role the negotiations themselves played in keeping the potential for adverse politicisation (salience, polarisation and widening mobilisation) in member states at bay. With the exception of Ireland and occasional localised flares, the article identifies persistently low levels of domestic salience and politicisation throughout the negotiations. Exploring national issue constellations and government positions in greater qualitative depth, it then describes how the priorities of each of influential member state case were mutually inclusive and could be strategically contained by the process as prescribed by Article 50, without allowing recourse to exceptional side-bargaining and the emergence of competing blocs within the Council. In turn, the UK’s demands defied the EU’s red lines and its attempts to probe the fundamental institutions of the European polity – the single market and customs union – were counterproductive, often eliciting defensive-cohesive reactions among member states.

In sum, the article highlights unique attributes of Brexit qua EU crisis: a limited groundswell of public and business attention, no significant politicisation, and an absence of national pressure uploaded to Europe. The next section restates the puzzle and situates this article’s contribution among similar accounts. The following section addresses cases, methods and data, situates the Brexit negotiations in their historical context and reconstructs stylised scenarios of unity and disunity among sets of dynamic actors. It then reviews the key post-functionalist concepts of salience and politicisation and introduces this article’s operationalisation for the Brexit negotiations based on an archival newspaper dataset covering five influential member state cases and EU institutions. Empirical analysis follows, with data covering two key aspects: quantitative comparative timelines, showing overall levels of salience and politicisation by territory; bookended by EU and country case studies tracing congruence between issue-salience and leaders’ stances as uploaded to the EU. Results indicate high levels of consensus between member states and EU institutions. The article concludes with a brief reflection on its findings and how they indicate clear differences between Brexit and other defining crises of the decade for the EU.

State of the art

Before describing this article’s approach, it is helpful to locate its basic novelty against existing accounts. Competing schools of thought have each been able to stake claims on both the UK and EU’s positions, spawned a multifaceted literature which we cannot hope to fully account for here. Jensen and Kelstrup (Citation2019) group work starting with the ‘unity puzzle’ as typically belonging to the rational choice, identity, bureaucratic or framing traditions. Was EU unity determined by leaders’ common interests (Durrant et al. Citation2018; Frennhoff Larsén and Khorana Citation2020; Hix Citation2018; Kassim and Usherwood Citation2018), their common Europeanist purpose in the face of increasing UK belligerence (Martill and Staiger Citation2022), decisive institutional agenda setting including via Article 50 and the Commission (Greubel Citation2019; Schuette Citation2021), or a common narrative of unity (Bijsmans et al. Citation2018; Koller et al. Citation2019)?

Triangulating, these authors (Jensen and Kelstrup Citation2019; see also Taggart et al. Citation2023) suggest all these factors played a part. However, none of these accounts directly address the puzzle of EU cohesion manifest during a ‘post-functionalist moment’, times of overlapping crisis and heightened mass Euroscepticism. Among these schools, the rationalist-utilitarian approach approximates most closely to post-functionalism, in that leaders must be self-interestedly sensitive to their publics’ preferences. For example, Chopin and Lequesne (Citation2021) identify leaders’ desire to preserve economic integration, early coordination and overall upticks in public EU attitudes that each facilitated unity. More directly, Walter’s (Citation2021) extensive public opinion surveys throughout the negotiations find that economic exposure to Brexit is associated with accommodating attitudes towards the UK, pro-European attitudes the opposite. This indicates that certain states and demographic groups might have exerted pressure for negotiating outcomes, and that Brexit did contain divisive potential both between- and within-states.

In the most explicitly post-functionalist take on the negotiations, Biermann and Jagdhuber (Citation2022) bridge rational choice and post-functionalist arguments, combining the notion of ‘constraining dissensus’ with a game theoretic approach that depicts the negotiations as nested two-level games. It is true that ‘increasing politicisation mandates a new, post-functionalist take on international negotiations’ (Biermann and Jagdhuber Citation2022: 17), but where their study examines the constraints imposed on Theresa May by intense politicisation, we set out to map and measure how unity among EU leaders was permitted by an absence of politicisation at home.

Finally, beyond theoretical standpoints, other studies overlap empirically with this article, comparing a similar member case set to explain unity (Taggart et al. Citation2023), or using similar newspaper sources for inductive frame identification (Bijsmans et al. Citation2018). This article makes two empirical advances. First, it introduces a dataset reconstructing the entire Brexit process from the referendum vote on 23 June 2016 to the signing of the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement on 30 December 2020. Tracking this full trajectory is necessary because Brexit’s temporal structure was initiated by a sudden shift (the referendum result), but engendered a much longer-term, contingent negotiation. Second, our data cover five countries plus EU institutions studying the policy process in detail and offering a rich, two-way insight into state-to-EU interactions and agenda control.

Analytical framework

As noted, Brexit presented all the hallmarks of a nascent crisis for the EU because after the initial shock, it presented existential threat and uncertainty downstream. This was embodied in the twin, antagonistic challenges of contagion and disunity. Emboldened Eurosceptic movements across the bloc might seek to mimic the UK, creating a powerful incentive for a punitive EU approach. Equally, member governments had varying entanglements with the UK and different conceptions of EU primacy, suggesting a flexible, accommodating stance especially for those with close bilateral British ties. In addition, the EU-27 had offered no a priori guarantees of unshakeable unity in future negotiations and, as noted, many of them had been embroiled in recent divisive conflicts with one another.

Both the Euro and migration crises appeared to be ‘post-functionalist moments’ – policy shocks bringing unprecedented levels of mass public salience and polarisation, politicising questions of European integration (Statham and Trenz Citation2015). While for Hooghe and Marks (Citation2009) the politics of ‘constraining dissensus’ had increasingly come to dominate this debate in the preceding decades, in the crisis-laden 2010s, constraints on further integration now threatened to tip over into active disintegration. More precisely, the post-functionalist features and mechanisms driving the dissensus apply acutely to crises: mainstream centre-left and -right parties being more pro-integration than voters-at-large; the rise of populist anti-European parties to fill the void; tighter coupling of domestic and European politics; and consequently, ‘an intensification of national stubbornness in European negotiations…[as] leaders have less room for manoeuvre’ (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009: 22).

The formation and rapid growth of populist challenger parties from the left and right and a broad north-south or core-periphery divide was a defining feature of the Euro crisis (Hutter and Kriesi Citation2019), while a similar divide emerged between frontline and destination states during the migration crisis (Kriesi et al. Citation2021). This is to suggest that post-functionalist pressures were necessary but not sufficient conditions for disintegration – indeed scholars have puzzled over the EU’s capacity to hold together in the face of such intense pressures. Facing bottom-up dissent from states and populations, EU actors are said to engage in strategic politicisation and depoliticisation, depending on their status and the issue at hand (Schimmelfennig Citation2020). Though their disintegrative effects are debateable, there is broad consensus that these pressures existed and that they contributed to significant disunity and contentious compromises between entrenched blocs of essentially-opposed states (Webber Citation2019).

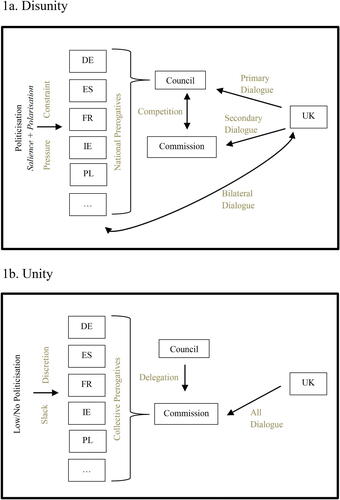

This article concerns whether and how similar pressures applied during the Brexit negotiations, and consequently whether Brexit should be considered a crisis on par with those preceding it. presents stylised scenarios of two potential Brexit negotiations processes. In 1a, Brexit is politicised at the national level, being both salient and polarising, leading to increased pressure on national leaders to strongly foreground their own national prerogatives, treating the negotiations as an instrumental opportunity to deliver wins. Subsequent sections discuss how these national prerogatives were not clearly aligned from the outset, with the potential for disruptive disagreement given crisis politicisation. The knock-on impact in this counterfactual scenario is then hypothesised. National prerogatives would be uploaded by each state into the intergovernmental Council, potentially leading to blocs or factions jostling to establish the EU’s official stance in the negotiations, likely to attract further public interest at home. Though the Commission is nominally empowered by Article 50 to lead the negotiations, its own position could be in competition with any number of these Council factions. In turn, the UK would be conducting dialogue with multiple partners: primarily with the Council and attendant informal multi-lateral factions; procedurally with a disempowered Commission; and bilaterally with like-minded states, a channel that the UK sought to exploit at key junctures throughout the negotiations. A positive exit experience would increase the threat of a domino effect in other countries (Walter Citation2021), and/or lead to emulation by Eurosceptic parties (van Kessel et al. Citation2020), feeding domestic salience and partisan polarisation, potentially translating into disunity. Again, this disunity counterfactual does not assume that the EU would not find some compromise to hold together, but it would make Brexit categorically more comparable to the Euro and migration crises.

By contrast, a unity scenario (1b) presents a simpler process for the EU, whereby the default architecture of Article 50 holds and the Commission retains tight control over the talks. This depicts Brexit as a ‘remote conflict’ (de Wilde and Lord Citation2016), characterised by the opposite of the post-functionalist menu: limited media coverage; issue confinement to foreign policy; and a mode of executive politics quietly dominated by mainstream pro-European parties. By extension, this assumes that EU incumbents enjoy slack and discretion in EU negotiations, away from the glare and heat of a domestically salient, politicised issue. The lack of elite-level conflict itself continues to keep press salience at a low level (since, to a large extent, conflict is what the media are in the business of reporting), allowing leaders to prioritise the Commission’s stated collective prerogatives: safeguarding the integrity of the Single Market and Customs Union and avoiding à la carte membership for the UK. Here, member states and the Council both delegate issue ownership to the Commission, the UK remains formally and informally excluded from Council discussions and is unable to establish bilateral footholds. Once again, the result is low levels of public salience and polarisation. Both scenarios imply a continuous interplay between the negotiations, national political elites’ stances, and public opinion. In other words, politicisation is both a dependent and independent variable, a factor constraining actors’ possible responses, but also at the same time, a product of these very responses.

As noted, is stylised, with actual outcomes likely existing on a spectrum somewhere between these two points and including variation over time. The key objective of this article is to establish to what extent, where and when Brexit exerted pressures on EU-level policymaking and how this potential was contained. To explore this, the article analyses a diverse and influential case set, presenting quantitative trends in key measures over time and a qualitative discussion of politicisation in each case. Before presenting results, this research design is first outlined at greater length.

Research design

Case selection

Member state selection comprises countries that were both influential in their own right, but also representative of wider shared sentiments. Following Taggart et al. (Citation2023: 2), we include France and Germany, the two most influential states and representatives of a ‘pro-integration core…motivated by preserving the unity and stability of the EU’. They contrast this dyad with Ireland, one of the ‘traditional UK allies’ alongside the Netherlands, Scandinavian and Baltic states, who were ‘motivated, in part, by a close economic relationship with the UK’; and Poland, totem of the Viségrad group, which prioritised trade and security, citizens’ rights and the EU’s financial settlement (Taggart et al. Citation2023: 2). To this selection we add Spain: a large, influential state from southern Europe, site of the largest population of British emigrants and of the sensitive diplomatic issue of Gibraltar. While we cannot claim to capture all national idiosyncrasies or a truly representative sample of EU27 sentiment, the five cases offer broad scope of influential positions, offering valuable insight on the key sites of potential pressure ‘uploaded’ to EU institutions. In turn, we also capture data on those institutions proper, so that we can assess interplay over time and whether the process was closer to the archetypes depicted in or .

Data and methodology

In order to reconstruct the negotiations, we use Policy Process Analysis (PPA), a methodological innovation that seeks to capture the public face of policy making (Bojár et al. Citation2023). PPA is a form of media content analysis that reconstructs policy processes by identifying actors and connecting them to policy positions by coding statements made in the public sphere. We apply this method to (1) map the policy issues raised by actors throughout the Brexit process and whether these issues were reflected in the EU’s negotiating agenda; (2) document the interactions of actors and, through them, coordination dynamics during the negotiations; and (3) measure and track salience and politicisation of various stages in the Brexit saga.

Our corpus comprises newspaper articles in each country accessed via the repository Factiva (Citation2023). Nationally, we sample from a quality daily newspaper, for EU institutions we use the Financial Times. Where data were available, we tried to select newspapers with high ranking circulations, and to ensure a degree of cross-case consistency we opted for newspapers with a similar centre-right editorial leaning, the exception being Spain, where data availability issues meant we needed to work with El País rather than El Mundo. While this contains some potential for editorial bias, we mitigate this by collecting factual news articles and disregarding in-house comment pieces. Search terms included the word ‘Brexit’ and the name of a country, widening or narrowing depending on the number of resulting hits.Footnote1 Once downloaded, we discarded ‘false positive’ hits before hand-coding actions in remaining relevant articles.

In PPA coding, the unit of observation is an ‘action’ relating to Brexit. This may be a meeting, letter, vote, or any relevant statement or intervention documented in the policy process. For each such action, we recorded the date and arena, the initiating actor, their nationality, role and affiliation (e.g. civil society, Prime Minister, official); the policy issue addressed by the action;Footnote2 the position of the actor on the issue (positive/negative/neutral); and any actor targeted by the action (if relevant). All actions that are related to the policy-making aspects of Brexit contained in the selected articles can be coded. However, to avoid overweighting any single search result, a maximum of three actions are coded per article. This already yields a widely differing number of results per case, indicating the varying salience of Brexit across borders ().

Table 1. Newspapers, article hits and actions by case.

While this methodological approach allows us to systematically collect and analyse longitudinal data, the primary focus on public debates as developed in media outlets comes with limitations. We are only able to map publicly visible, mediated aspects of the developments we are interested in. Nonetheless, our methodological approach is grounded in the post-functionalist tenet that, in the era of constraining dissensus and politicised Europe, EU decisions are decisively influenced by debates that take place and are visible in the public sphere.

Analysis spans approximately four and a half years, bookended by the referendum (23 June 2016) and the end of the Withdrawal Agreement transition period (31 December 2020). While procedurally negotiations only commenced in March 2017 with the UK’s triggering of Article 50, debates and manoeuvres over the coming process were activated by the referendum result, and necessitate an earlier start date. Equally, debates over Brexit did not conclude in 2020, but this period marked the definitive conclusion of negotiations with the signing of the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement and the end of the transitional withdrawal agreement.

Provisionally agreed Council guidelines prioritised Single Market integrity; the indivisibility of the four freedoms of labour, goods, services, and capital; ensuring that non-members cannot enjoy the same rights as members; and conducting negotiations exclusively through EU channels (European Council Citation2017). By contrast, the main British aspiration throughout the negotiations would be to retain access to specific elements of the internal market while being able to strike third-party bilateral trade deals, plus an end to freedom of movement and European Court of Justice jurisdiction (Laffan and Telle Citation2023: 9). The essential incompatibility of these positions ultimately focused on Northern Ireland, as the Irish case documents below.

Quiet unity: empirical analysis

EU-27 coordinative dynamics

In the immediate aftermath of the Brexit referendum, the UK government’s initial strategy was to probe for internal divisions within the EU-27 by establishing bilateral channels with targeted states. The uncertainty surrounding Brexit suggests that this held promise. While the topic of EU unity had become ubiquitous in the discourse of mainstream political leaders across the EU in the immediate aftermath of the referendum, the Visegrád Four in contrast attacked Commission President Juncker, calling into question his leadership (Financial Times Citation2016a). However, just a handful of bilateral inter-governmental contacts between the British and other EU governments (from the Netherlands, France, Germany, Ireland, and Poland) are identified in our dataset. Contact with Poland was arguably deepest and most threatening to EU unity. During the early, pre-negotiations period, Theresa May met multiple times with high-ranking Polish officials in both Poland and the UK, including Prime Minister Beata Szydło and PiS leader Jaroslaw Kaczyński (Financial Times Citation2017a). Initially, the discussions centred on NATO cooperation and the rights of Polish citizens in the UK, and it appeared the Polish government was unilaterally seeking reassurances concerning the country’s large UK diaspora. Less than a month before the British government officially triggered Article 50, in early March 2017, Szydło and May announced the establishment of a ‘Polish-British Civic Forum’, a platform through which the two governments could coordinate informally ahead of the negotiations (Rzeczpospolita Citation2017a). Furthermore, immediately after Article 50 was triggered, the premiers and the foreign ministers of both countries held telephone conferences with the British side presumably seeking reassurances of Polish support (Rzeczpospolita Citation2017b). While there were some further instances of British-Polish bilateral coordination, pursued mostly by the UK, they never threatened the united position of the EU-27, neither did they call into question the Commission’s negotiation mandate.

Similarly, there was no appetite to challenge the withdrawal process as outlined by Article 50. Instead, its design proved key in disarming the UK’s divisive tactics. On the one hand, by expressly affirming that the withdrawing state must negotiate with the Union, Article 50 discourages member states from being directly involved in the negotiations, therefore limiting de jure the ability of the withdrawing country to play a divide-and-rule strategy after notification (Gatti Citation2017). However, on the other, beyond the mandate to negotiate withdrawal with the Union as a whole, a concrete governance system to organise the negotiation by the EU had to be defined (Laffan and Telle Citation2023: 81). The institutional system put in place had the European Council at the top, reassuring the member states that they had a say: it set the guidelines to be followed in the negotiations, oversaw the negotiation process, and was the only actor capable of determining whether ‘sufficient progress’ had been made in the negotiations. Nevertheless, the institution negotiating with the UK government was not the European Council, but the European Commission. The Commission appointed Michel Barnier as its chief – and only – Brexit negotiator. He was supported by a Task Force on Article 50, composed of experts and Commission officials on all major policy areas affected by the negotiations, as well as by a dedicated Council Working Party, chaired by Didier Seeuws. Finally, the European Parliament was marginally involved in the process through its Brexit Steering Group. As such, the operationalisation of Article 50 reduced EU-level fragmentation ex ante by ensuring inter-institutional coordination and, more important, by making compatible the diversity of member states’ interests with a centralised negotiating strategy. Indeed, aware of its constraining potential, EU leaders pushed the British government to initiate Article 50 proceedings even earlier than March 2017 (e.g. Financial Times Citation2016a), but Theresa May resisted initiating formal exit negotiations for several months.

While the UK government struggled to gain much traction for its interests, proactive member state governments could easily secure concrete assurances within the EU side. Following the referendum, a flurry of intergovernmental meetings took place between various sets of member states (Financial Times Citation2016b). French President Hollande toured select smaller states (Austria, Portugal, Ireland, Slovakia, Czech Republic) to secure consensus and simultaneously push the UK to swiftly initiate exit proceedings. No member state government used this approach more than Ireland, with Taoiseach Enda Kenny and Foreign Minister Charles Flanagan extensively touring the continent seeking to convey the depth of Irish concerns. Irish officials convinced the three largest EU-27 states – Germany, France and Italy – to formally acknowledge the special nature of the country’s interests. These centred on sensitive economic and border-related linkages between Ireland and the UK, which were in turn linked to bilateral treaties between the two, such as their Common Travel Area (CTA) and the Good Friday Agreement (GFA). Visiting Dublin in August 2016, the President of the EU Council, Donald Tusk, acknowledged this sensitivity. Once Michel Barnier was appointed as the Commission’s head negotiator, Irish leaders stressed the same point to him and President Juncker, impressing on them both the necessity of prioritising Irish interests in any negotiation.

By the time the British government triggered Article 50 on 29 March 2017, their Irish counterparts had already pushed their interests to the front of the negotiation table. The success of this strategy was reflected in Barnier’s regular reassurances once the negotiations proper had started that the satisfaction of Irish demands needed to be met before the second round of talks with the UK, focusing on future trade relationships, could be initiated. This would prove problematic, as the UK would often note that the Irish question and UK-EU trade and customs relationships are inextricably linked. In fact, the prioritisation of Irish issues was not only beneficial to Ireland, but also provided strong leverage for EU negotiators to push the UK on the customs issue while revealing fractures within British domestic politics. In any case, when considering how the EU consensus was forged, one of the answers was through sustained diplomatic efforts and meetings between interested parties to support each other’s idiosyncratic interests, with Ireland proving especially influential. Irish leaders were also able to exert this pressure at the EU level while negotiating bilaterally with the UK over the CTA, receiving assurances about the rights of UK-based Irish citizens, even as the critical border issue remained unresolved. Prominent Leave campaigners’ prediction that the commercial interests of large exporting nations such as Germany would outweigh Ireland’s apparently esoteric concerns proved to be a major misreading of EU-27 dynamics (The Guardian Citation2017).

EU-level analysis corroborates the success of coordinated and centralised negotiating strategy. The range of actors the UK could engage with in the Brexit negotiations was limited throughout the entire period of our study. The major protagonists of the Brexit talks were the EU (intra-EU actions), Ireland, and the UK (making up 18%, 23% and 31% of all recorded actions in our dataset, respectively). A further breakdown of the EU actors reveals that the legal competence of the Commission and the Barnier negotiating team per Article 50 was respected, with approximately a quarter of all the recorded EU actions being initiated by these actors. In fact, if we only look at the actions having the UK as target actor coming from outside the UK, 40% of them are initiated by European institutions, with the Brexit negotiating team taking the lead, 24% by the Irish government and then only 15% by the rest of the national executives of the other four state cases. Barnier reinforced his role by providing regular updates to the Council and the European Parliament, which in turn gave input and guidance. Moreover, the EU’s chief negotiator toured Europe participating in consultations with governmental and civil society actors from the member states to ensure that their concerns were allayed (Frennhoff Larsén and Khorana Citation2020).

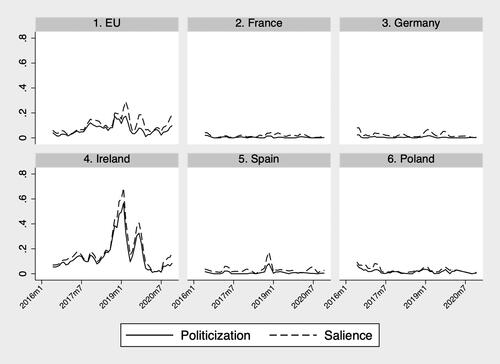

Salience, polarisation and politicisation

Tracking domestic salience and polarisation over the entire Brexit negotiation period, data reveal that in all countries but Ireland these were limited: Brexit-related issues were treated mainly by governmental actors in a high-level manner. To be sure, at the supranational level, conflict between the UK and EU reached high levels of intensity. As shown in the first panel of , the most politicised phase of the negotiations occurred between 2018 and 2019, including repeated extensions and the May government’s (unsuccessful) attempts to push through a deal in the British parliament. However, among the five country cases a sizeable level of politicisation is only visible in Ireland, and indeed we take this as a benchmark to assess those of our other studied countries. Our politicisation index is constructed by multiplying salience (the number of actions in a given month over total actions) by polarisation (roughly an index of the proportion of opposing positions on a given issue in any month), in line with other recent work on the topic (Kriesi et al. Citation2019; Kriesi and Hutter Citation2019). Defining politicisation in this way allows us to capture both the attention paid to an issue, as it rises in salience, but also actor expansion indirectly, as more actions and more polarised actions essentially indicate a wider set of actors becoming involved (see de Wilde et al. Citation2016). While this is not a perfectly comprehensive encapsulation of politicisation qua actor expansion, it is nonetheless better suited for our studies where the range of leading, influential actors is pre-defined (governments plus European institutions), and where we focus on the actions and counter-actions of these main players. We also show the time series of the salience metric along politicisation to demonstrate that salience is the main driver of politicisation. The second component, polarisation, was low for most issues and any polarisation was rather an artefact of low salience or the result of a confrontation either within the UK (for example between business actors and the government) or between the UK and its European interlocutors. In contrast, we have no evidence of any significant overt conflict between the EU partners which would have driven up levels of salience and politicisation.

More specifically, in Ireland, Brexit became particularly politicised over the course of 2018, when the Varadkar government was accused by domestic opposition of hindering progress that was already achieved in talks by the Northern Irish unionist parties and of not pushing the Irish agenda forcefully or successfully, mainly by squandering the opportunity to force Britain’s hand on the customs union (The Irish Times Citation2018b, Citation2018c).

In Germany domestic political debate of Brexit was brief, frontloaded through summer 2016, and did not lead to widespread politicisation. Immediately after the referendum an inflection period saw a limited amount of contestation between the two Volksparteien and Grand Coalition partners: in July 2016 SPD ministers led by Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel presented reports including roadmaps for further European integration in the absence of the blocking influence of the UK (Die Welt Citation2016a). However, these were rejected by CDU-CSU leaders, including Chancellor Angela Merkel and Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble, who instead wanted to hold the line and maintain a low profile, seeking to treat Brexit as a damage control process rather than a positive opportunity to be exploited. Even Alternative für Deutschland leaders were themselves split immediately after the vote, with some celebrating Brexit and others lamenting it as leaving Europe weaker (Die Welt Citation2016b).

The case of Poland is also interesting because of the role of former Prime Minister Donald Tusk serving as the Council President at the time. In this role, he was occasionally the target of accusations by political opponents, because of his handling of the negotiations (Rzeczpospolita Citation2016b). In turn, opposition politicians sometimes criticised the PiS-led Polish government on its Brexit-related positions, also pointing out Poland’s marginalisation in the shifting post-Brexit political landscape of Europe, and its conflict with the EU over the rule of law (Rzeczpospolita Citation2016a). Overall, however, the levels of both salience and politicisation remained low.

In France, yet another line of potential conflict appeared, between mainstream and challenger parties with Brexit receiving early approval from both the radical left and right. Leading figures from the Front National and Debout La France celebrated the referendum result, depicting it as a win for the forces of democracy (Figaro Citation2016). On the radical left (La France Insoumise), Brexit was met with more conditional understanding, but this initial tendency quickly subsided, and the subsequent negotiations were not particularly salient or controversial in France. Politicisation was even lower in Spain, where the negotiations proved entirely uncontentious, and the opposition parties’ positions on the negotiations were rarely reported by El País. The exception in this regard was the Gibraltar question, which during the last months of the Mariano Rajoy government and the early ones of the Pedro Sánchez government became a matter of inter-party debate but was soon resolved to the satisfaction of the Spanish government.

In general, then, except for Ireland, we see low levels of interest in Brexit with some flares of salience and politicisation, which were geographically and temporally limited. For example, we see that for France politicisation is only high around the time of the first agreement (between the May government and the EU) and around the end of the negotiations when the trade deal and fisheries are discussed. Conversely, politicisation in Ireland was highest when the protocol was negotiated and then renegotiated by the Johnson government (two peaks in ).

Country-specific concerns

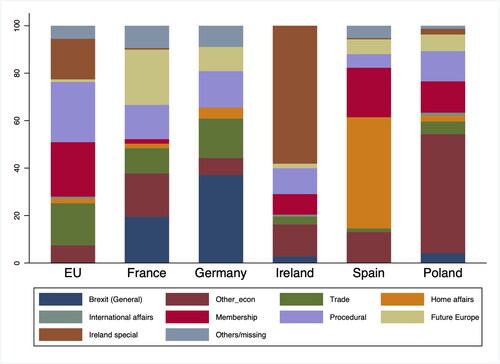

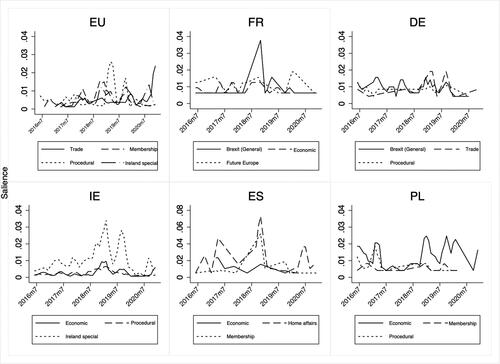

Our data allow us to zoom into the issues that have driven politicisation in our country cases as well as at the EU level (between the EU-UK negotiators). In , we present the salience of the three major issues as a share of the totality of issues over the entire time of the negotiations for each case.Footnote3 displays all the main issues as they have been discussed in each case so as to provide a different comparative perspective.

Figure 3. Issue salience during the Brexit negotiations.

Note: The Spanish case scaled differently due to the preponderance of the Home Affairs category, which concerned Gibraltar.

At the country level, we see a variety of priorities in the different member states (). A closer look at the development of debates related to Brexit in our selected countries shows that these were marked by elite-led strategising and argumentation, rather than bottom-up transmission of popular concern. Low levels of domestic salience were only occasionally breached by a few idiosyncratic issues. These issues reflected each state’s policy priorities and were generally mutually inclusive. Indeed, throughout the negotiations, national governments showed a consensus-seeking attitude, generally framed in technical terms, that nurtured the depoliticisation of the Brexit debate.

Spain’s most salient issues are instructive. Here, the Brexit debate was dominated by implications for Gibraltar, a British Overseas Territory bordering and claimed by Spain, an issue included in our ‘home affairs’ category. The issue was framed in a different manner under two different Spanish governments. Under the conservative administration led by Rajoy (until June 2018), sovereignty concerns predominated. The subsequent socialist government led by Sánchez focused instead on Gibraltar’s tax regime and the cross-border movement of people and goods. During EU Council negotiations over the UK withdrawal agreement, in November 2018, Sánchez blocked the deal for three days, dissatisfied with terms related to Spain’s right to veto EU decisions over Gibraltar (El País Citation2018). Once Spain obtained guarantees about its right to control Gibraltar’s inclusion in the future EU-UK trade agreement, the Sánchez government, during 2018 and 2019, bilaterally negotiated with the UK one protocol and four memoranda of understanding on transborder cooperation in Gibraltar, which were later included as a chapter in the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement of 2020. In December 2022, the European Commission, representing the EU, and the UK reached an agreement on a fully-fledged treaty on Gibraltar (which ensured an ‘invisible’ border between Spain and the British territory). Two other issues were also salient in the Spanish debate on Brexit: first, the economic consequences of the UK’s exit for Spain, perhaps unsurprising given that the UK is the main destination of Spanish exports and UK tourists represent the highest share of visitors. Secondly, the respective rights of Spanish and British immigrants in the UK and Spain in the post-Brexit scenario, categorised under the ‘membership’ model issue in , also predictable given the high number of British pensioners in Spain as well as the high number of Spanish workers in the UK.

These issue priorities mirror the ones we find in Poland. Here, the economic costs but also occasionally, the potential benefits of Brexit were the most salient issue for the entire duration of the negotiations. The fate of the significant number of Polish citizens living and working in the UK was also discussed, though it was not as salient in the media as we would have expected (‘Home affairs’ in and ). Coalescing with Spain’s interests, the decision of the EU negotiating team to prioritise citizens’ rights during the divorce talks likely came primarily in response to the above-mentioned bilateral dealings between the Polish and British governments. Other salient issues in Poland have to do with the country’s traditional preoccupation with international security. Furthermore, especially in the early post-referendum period, Brexit seems to have prompted a broader reflection on the changing balance of power in an EU without the UK (‘Future of Europe’ in and ). In the immediate aftermath of the referendum, PiS party leader Jarosław Kaczyński declared that there was a need for a new European treaty, arguing that ‘we must find a model for Europe that reflects Europe as it really is […] It’s still a Europe of nations, of nation states’ (Euractiv Citation2016). However, Kaczyński did not assess Brexit as a positive development, while he also ruled out any talk of a referendum on Poland’s EU membership (Euractiv Citation2016).

The case of Ireland involved an even more insurmountable challenge to the integrity of the EU’s and the UK’s borders than Gibraltar: Northern Ireland, placed in our coding scheme under the more general ‘Ireland Special’ category ( and ). Talks of Irish unity and proposals about retaining a special status for Northern Ireland within the EU morphed into an even more politicised debate there over how to avoid a hard border and how a hard border would affect and likely be incompatible with the Good Friday Agreement. Constant reassurances from the EU, UK, and Irish governments about their mutual willingness to respect the sensitivity of the Irish border issue were accompanied by puzzlement from European and Irish authorities as to how this will be achieved while allowing for the UK to depart from the EU’s customs area (see for example The Irish Times Citation2017, Citation2018a). Other salient issues were the rights of Irish people in the UK and the CTA, arrangements that predated both states’ EU membership and that both sides wanted to maintain. Eventually, an agreement to conserve the CTA and pre-existing arrangements on British travel was struck, leaving Northern Ireland as the last, most thorny outlying issue to be addressed iteratively under a new protocol regime.

France and Germany exhibited similarities but also diverged in their primary concerns. We notice a more opportunistic approach to Brexit in terms of its potential benefits in both cases. Prior to the referendum, French actors appeared wary about Britain’s departure as a potential catastrophe with serious implications for the future of France and Europe ( and ). But in the vote’s aftermath, like in the Polish case, political and business elites coalesced around a more positive vision of how Brexit could benefit France in two areas: domestic economic reforms, helping France to capitalise on business and investment opportunities; and European leadership, allowing France to reshape Europe in its image without the historical blockage of the UK. With the arrival of Emmanuel Macron in 2017, both domestic and European causes found a champion and agenda setter. Brexit was increasingly cast as an opportunity for France to take over high-value industry share from the UK, particularly in financial services.

In Germany, there was substantial reflection on what Brexit meant for the future of the European project and whether it might be considered a precedent or a one-off (Brexit – General on and ). Political leaders appeared more concerned about the costs of Brexit than excited about the opportunities it provided, particularly what it meant for bilateral trade. While all warnings of the effects of Brexit highlight an asymmetry of impact on the UK, German business leaders, including the President of the main automotive industry body, stressed the importance of maintaining a free trade compromise (Die Welt Citation2016c). However, local leaders in Hamburg, Berlin and Frankfurt also sought to take advantage of the weakening of London as a European centre of finance and innovation (Die Welt Citation2017). Rather than a nationally endorsed effort as in France under Macron, Brexit upsides were instead occasionally trumpeted by German cities and states, leaving national leaders to push a more conciliatory line.

Unlike in the case of Spain, where procedural issues about the Brexit talks were not salient – in line with the low-profile traditionally maintained by Spanish representatives in EU debates that do not directly concern Spain (Perarnaud and Arregui Citation2023) – German and particularly French actors referred to such issues frequently ( and ). While the former took a more accommodative and the latter a more confrontational approach, these disagreements did not spill-over to the public debate in any dramatic fashion. In Germany, both leading political parties generally responded to the precise issue of negotiations in a similar fashion, with influential parliamentarians such as Foreign Affairs Committee Chair Norbert Röttgen repeatedly emphasising that Brexit à la carte was not acceptable and that the UK would face genuine trade-offs and costs (Die Welt Citation2019). Here, the agreed stated preference was for a ‘soft Brexit’ and the maintenance of as many trading and security relationships as possible.

Hollande and then Macron took a less accommodating approach. Especially as negotiations dragged on, over the course of 2019, French officials appeared to lose patience with the continued uncertainty produced by the UK’s delays (Figaro Citation2019). Only in this respect did France depart substantively from the negotiating goals of the EU-27 and institutions by opposing the extension of the deadlines, even if, in the end, they accepted the other members’ willingness to postpone the end date yet again (Financial Times Citation2019). However, this debate over timing was always a second-order concern in French politics and did not amount to a fundamental disagreement over negotiating goals or objectives. In this respect, even though France was eager to move on from Brexit, its domestic politics was not compromised in any serious way by being outweighed by Germany or the Council and Commission who were prepared to give the UK as much time as it needed in the hope of a softening or reversal of its departure. Similar to Germany, Poland preferred dragging negotiations out indefinitely to find the most accommodative solution for everyone and was willing to allow the UK to stall further.

Managing EU-UK negotiations

If the UK government ever planned to conduct bilateral negotiations and divide the member states, it failed. While the EU27 continued to regularly coordinate with each other both in intra-institutional venues (Council) and extra-institutionally (in various bilateral and multilateral formats), the British government’s primary interlocutor during the Brexit negotiations was the Commission’s negotiating team. EU unity hinged on the team’s ability to reassure national governments that their core specific interests were being protected. Initially, the negotiations became focused mainly on four major issues: citizens’ rights, the UK’s financial obligations to the EU, the border with Ireland and the post-post-withdrawal ‘future relationship’ between the UK and EU27. As decided by the EU, the later aspect would be negotiated in a separate agreement under Article 2018 of the TFEU, and only after the negotiations on the Withdrawal Agreement had been concluded (see Online appendix).

Among the three ‘pre-withdrawal’ issues, the financial settlement was, in the initial period of the negotiations, the most keenly contested by the British government and became the source of intense confrontation between the two sides. However, this was also the issue that had the smallest potential to divide the EU-27 since it was in line with the interests of both net contributors and net recipients of the EU budget. The other thing to notice is that all the major issues that have been nationally salient in our country cases were given attention by the negotiators. The rights of Poles in the UK were the major Polish concern immediately after the referendum and once the issue had been successfully settled (after ‘sufficient progress’ had been reached) interest faded in Poland and was mainly confined to the economic terrain. Over the course of 2019 the Irish border became the central issue of the UK-EU negotiations particularly in anticipation of the withdrawal agreement for the EU institutions.

Despite the negotiations revolving around more general EU-UK issues, the Commission’s negotiating team also accommodated any idiosyncratic issues or preferences of the EU-27. The negotiations on Gibraltar are particularly instructive as they began through a different (bilateral) channel and continued in a different time frame (post-2021) than the rest of the Brexit negotiations. The reason for this has to do with Spain’s preference for a bilateral format, as well as with the existence of previously institutionalised negotiation channels between both countries on the Gibraltar question (the so-called Forum of Dialogue). The EU demonstrated flexibility in this respect, and indeed the big spike in the salience of the Gibraltar issue in Spain faded once the issue was resolved.

Alongside substantive issues, the negotiations revolved around two aspects. On the one hand, there were various partly overlapping versions of Brexit: ‘soft’ or ‘hard’, ‘orderly’ or ‘disorderly’ or ‘no deal’. On the other hand, there was debate over procedural aspects of the negotiations, such as their pace and sequencing (reflected in our codes ‘Brexit models’ and ‘procedural issues’ in and ). The participants continuously disputed the terms of their engagement and reflected on negotiation strategies more generally. As already mentioned, initially, the apple of discord was whether the UK government would trigger Article 50, and then if the talks about the divorce and the future relationship would proceed in parallel or not. The British government sought to link the debate on the financial settlement with the negotiations of the post-exit cooperation framework (Financial Times Citation2017b), a prerogative eventually blocked by the EU’s red line that future relationships would only be discussed after a withdrawal agreement. Throughout the negotiations, the EU side put constant pressure on the British government to come up with ‘substantive proposals’, to work faster, and later, it insisted that what had been agreed could not be renegotiated (Financial Times Citation2018). This rigid approach to the negotiation process worked to the EU’s advantage, allowing it to control it while also criticising the British government for its negotiation tactics.

By the Spring of 2019, procedural issues revolved around the British government’s repeated appeals to ask for an extension of Britain’s exit from the EU as Theresa May was struggling to get the agreed deal through Parliament. At this point some rifts finally appeared among the EU-27, seeping through the filter of carefully calibrated mediated discourse. On one side were the hardliners: the French government, Barnier and Juncker; and on the other those advocating for a softer approach: President Tusk, the German and Irish governments. The disagreement was prompted by three successive deadline extensions, with Macron opposing further delays, while Merkel and Varadkar prepared to give the British government more time (Financial Times Citation2019). Deadlines were finally agreed in all instances without causing any major disturbance and despite Eurosceptic groups’ attempts to deepen divisions. In March 2019, Nigel Farage declared that he would lobby select EU leaders to veto any deadline extension (Euractiv Citation2019). This resurfaced again seven months later with Eurosceptic Conservatives suggesting that the Hungarian or Polish governments might be willing to wield vetoes (Financial Times Citation2019b). Such a Eurosceptic action plan failed to materialise, and we see little indication of any public pressure for it in any of the states analysed. This suggests that EU-27 divisions on this question were superficial or perhaps even tactical, designed to apply external pressure to the UK’s own fractured domestic deal making.

Conclusions

Predictions that Brexit would undermine the cohesion of the EU-27 or even prompt wider EU disintegration failed to materialise. This was not inevitable but resulted from the EU’s ability to mobilise sufficient political resources and control the negotiating process with the aim of containing, compartmentalising, and managing the fallout caused by Brexit. This article offers a detailed account of this process, illuminating the following aspects as key to ensuring EU unity and polity maintenance.

First, EU institutions were strongly empowered to steer the negotiating agenda. Preference ‘uploading’ from key member states never seriously threatened to undermine the centralised process. Leaders in each member state developed their own idiosyncratic preferences on Brexit, but these were not in strong conflict with one another, and did not threaten to compromise the unity of the EU-27. This owes to the fact that, while Brexit was an ultra-salient, highly politicised struggle in British politics, it was only a niche issue within other states, except in Ireland, where it was salient but not especially polarising. Negotiations were an elite-driven, strategic process, steered by the EU institutions and, at key junctures (such as immediately after the referendum), influential member states such as France and Germany, whose leaders used informal contact with others from around Europe to shore-up EU unity. The implemented negotiating strategy showed two strengths. On one hand, by jointly identifying priorities and periodically confirming consensus, it ensured not only the full support of national governments, but it also disincentivised these governments to ‘go public’ (Kernell Citation1997), to expand potential conflicts in the public sphere. On the other, by ensuring the respect of the issue priorities defined by each member state, it reduced the Commission’s room of manoeuvre in the negotiations, and, by implication, diminished the UK’s possibility of persuading the Commission to compromise on less favourable outcomes from an EU-27 perspective.

Second, the analysis also shows that the pattern of politicisation generated by this negotiation dynamic in the EU member states was that of a ‘remote conflict’ (de Wilde and Lord Citation2016), that is, a foreign problem not necessarily feeding into highly politicised patterns of polarisation, as expected by the ‘domestic conflicts’ on EU integration predicted by post-functionalism. In contrast to a post-functionalist dynamic marked by identity-based demands, nationalist discourses and mass politics, the Brexit process for the EU-27 might better fit a neo-functionalist perspective, according to which the shared preference for the integrity of the single market overrides other concerns (Schimmelfennig Citation2018: 14), and a certain permissive consensus enables ample margins for supranational elites and national executives to square differences behind closed doors. To the extent that Brexit sparked politicisation, it can be characterised, in Wolff and Ladi’s (Citation2020) terms as ‘politicisation at the top’.

Further research is needed to assess the applicability to other policy areas and crises of the governance practices adopted by EU actors to handle Brexit, and more generally, on the conditions that transform potential bottom-up politicisation pressures in constraining or enabling EU polity maintenance. Yet, echoing Laffan (Citation2019), our analysis indicates that though Brexit started out as an existential moment, it ultimately exerted a counter-effect: solidifying member states by focusing them on the basic privileges of membership.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (717.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anna Kyriazi

Anna Kyriazi is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Social and Political Sciences, University of Milan. Her research focuses on comparative European politics and public policy, migration and political communication. [[email protected]]

Argyrios Altiparmakis

Argyrios Altiparmakis is a Research Fellow at the European University Institute. His research focuses on party politics, political behaviour and the recent European crises. He is currently working on the SOLID-ERC project. [[email protected]]

Joseph Ganderson

Joseph Ganderson is a postdoctoral researcher at the European Institute, London School of Economics. His research interests include the political economy of banking and finance and the wider impact of political crises in the UK and European Union. [[email protected]]

Joan Miró

Joan Miró is Assistant Professor in EU Politics & Policy at Pompeu Fabra University. His research interests lie in European integration, particularly the socioeconomic governance of the EMU, social policy, and international political economy. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 In Factiva, the format of the search is: ‘Brexit’ AND ‘X’, where X is the country name (local language). If we wish to narrow the field, we add an ‘atleastY’ clause, limiting the hits to articles where Brexit and/or the name of the country appear Y times. For example, for Ireland we look for ‘atleast3 Brexit and atleast3 Ireland’. While this may seem narrow, we are confident we do not miss much, because hits are appearing at extremely high frequencies. Brexit has been more peripheral as an issue in Spain and our widest searches yield approximately 300 articles, while a similar search in Ireland yields 5000+ articles. As such, for a case such as Ireland, we tighten the search terms, adding a certain amount of times Brexit or Ireland must be referenced in the text in order to focus our attention on articles more centred specifically on this subject.

2 For a full list of issues and sub-issues, see Table A4 in the Online appendix.

3 The formula is , where i is issue, t is time and j is a country case. In essence, the y axis measures the relative importance of the issue and how much it occupied our actors at each point in time. Only the three most important issue categories for each country are included.

References

- Biermann, Felix, and Stefan Jagdhuber (2022). ‘Take It and Leave It! A Postfunctionalist Bargaining Approach to the Brexit Negotiations’, West European Politics, 45:4, 793–815.

- Bijsmans, Patrick, Charlotte Galpin, and Benjamin Leruth (2018). ‘“Brexit” in Transnational Perspective: An Analysis of Newspapers in France, Germany and The Netherlands’, Comparative European Politics, 16:5, 825–42.

- Bojár, Abel, Anna Kyriazi, Ioana E. Oana, and Zbigniew Truchlewski (2023). ‘A Novel Method for Studying Policymaking: Policy Process Analysis (PPA) Applied to the Refugee Crisis’, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Paper No. RSC, 24.

- Chopin, Thierry, and Christian Lequesne (2021). ‘Disintegration Reversed: Brexit and the Cohesiveness of the EU-27’, Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 29:3, 419–31.

- De Wilde, Pieter, and Christopher Lord (2016). ‘Assessing Actually Existing Trajectories of EU Politicisation’, West European Politics, 39:1, 145–63.

- De Wilde, Pieter, Anna Leupold, and Henning Schmidtke (2016). ‘Introduction: The Differentiated Politicisation of European Governance’, West European Politics, 39:1, 3–22.

- Die Welt (2016a). ‘Warum Gabriel und Tsipras jetzt ziemlich beste Freunde sind’, 30 June, retrieved from Factiva.

- Die Welt (2016b). ‘AfD fordert mehr direkte Demokratie und gibt Merkel Schuld an Brexit’, 24 June, retrieved from Factiva.

- Die Welt (2016c). ‘Deutsche Autobranche will das "norwegische Modell’, 5 July, retrieved from Factiva.

- Die Welt (2017). ‘Banken-Umzug; "Es reicht nicht aus, einen Briefkasten anzuschrauben’, 31 January, retrieved from Factiva.

- Die Welt (2019). ‘Brexit-Krise; Johnson schiebt Merkel den Schwarzen Peter zu’, 9 October, retrieved from Factiva.

- Durrant, Tim., Alex Stojanovic, and Lewis Lloyd (2018). Negotiating Brexit: the Views of the EU-27: Our Brexit Work. Available online at: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/IfG_views-eu-27-v5_WEB.pdf.

- El País (2018). ‘Sánchez amenaza con votar contra del acuerdo del Brexit por Gibraltar’, November 21.

- Euractiv (2016). ‘Poland urges ‘new EU treaty’, based on nation states’, 24 June.

- Euractiv (2019). ‘Farage to Lobby EU Countries in Search of Brexit Extension Veto’, 14 March.

- European Council (2017). ‘Special Meeting of the European Council (Art. 50) – Guidelines’, EUCOXT20004/17, Brussels, April 29.

- Factiva (2023). Online Newspaper Archive.

- Figaro (2016). ‘Guaino: «Attention à ne pas confondre Brexit et Frexit: la différence s'appelle l'euro…»’, 26 June, retrieved from Factiva.

- Figaro (2019). ‘Les puissances du G7 en ordre dispersé’, 24 August, retrieved from Factiva.

- Financial Times (2016a). ‘Eastern Europeans Bemoan Brexit and Shun Closer EU Integration’, June 30, retrieved from Factiva.

- Financial Times (2016b). ‘European Leaders Seek to Bolster Economy; Naples Summit’, 22 August, retrieved from Factiva.

- Financial Times (2017a). ‘Theresa May Seeks Poland’s Support for Brexit Deal’, March 23, retrieved from Factiva.

- Financial Times (2017b). ‘May Warns EU27 against Pushing Her Too Far’, 20 October, retrieved from Factiva.

- Financial Times (2018). ‘May Kicks Brexit Vote to New Year as Threat Escalates of Tory Mutiny’, 12 December, retrieved from Factiva.

- Financial Times (2019). ‘France Digs in Heels as EU Weighs Brexit Extension’, 26 October, retrieved from Factiva.

- Frennhoff Larsén, Magdalena, and Sangeeta Khorana (2020). ‘Negotiating Brexit: A Clash of Approaches’, Comparative European Politics, 18:5, 858–77.

- Gatti, Matteo (2017). ‘Art. 50 TEU: A Well-Designed Secession Clause’, European Papers, 2:1, 159–81.

- Greubel, Johannes (2019). ‘The EU’s Governance System of Brexit and Its Impact on the Negotiations’, Policy Brief, European Policy Centre.

- Hix, Simon (2018). ‘Brexit: Where is the EU-UK Relationship Heading?’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56:S1, 11–27.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks (2009). ‘A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus’, British Journal of Political Science, 39:1, 1–23.

- Hutter, Swen, and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. (2019). European Party Politics in Times of Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Independent (2016). ‘Brexit: Article 50 Was Never Actually Meant to Be Used, Says Its Author’, 26 July.

- Jensen, Mads Dagnis, and Jesper Dahl Kelstrup (2019). ‘House United, House Divided: Explaining the EU’s Unity in the Brexit Negotiations’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57:S1, 28–39.

- Juncker, Jean-Claude (2016). ‘Speech by President Jean-Claude Juncker at the Annual General Meeting of the Hellenic Federation of Enterprises (SEV) ’, 21 June. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_16_2293.

- Kassim, Hussein, and Simon Usherwood, eds. (2018). Negotiating Brexit: What Do the UK’s Negotiating Partners Want? London: UK in a Changing Europe.

- Kernell, Samuel (1997). Going Public. New Strategies of Presidential Leadership. Washington: Congressional Quarterly Press.

- Koller, Veronika, Susanne Kopf, and Marlene Miglbauer, eds. (2019). Discourses of Brexit. London: Routledge

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, and Swen Hutter, eds. (2019). Restructuring European Party Politics in Times of Crises. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Argyrios Altiparmakis, Abel Bojar, and Ioana E. Oana (2021). ‘Debordering and Re-Bordering in the Refugee Crisis: A Case of “Defensive Integration”’, Journal of European Public Policy, 28:3, 331–49.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Swen Hutter, and Abel Bojar (2019). ‘Contentious Episode Analysis’, Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 24:3, 251–73.

- Laffan, Brigid (2019). ‘How the EU-27 Came to Be’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57:S1, 13–27.

- Laffan, Brigid, and Stefan Telle (2023). The EU's Response to Brexit: United and Effective. Basingstoke: Palgrave McMillan.

- Martill, Benjamin, and Uta Staiger (2022). ‘Prisoners of the Own Device: Brexit as a Failed Negotiating Strategy’, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 24:4, 582–97.

- Perarnaud, Clément, and Javier Arregui (2023). ‘Still a “Spectator”? Capabilities of the Spanish REPER and Spain’s Influence in the Council of the EU’, Revista Española de Ciencia Política, 61:1, 13–35.

- Politico (2016). ‘Brussels Power Struggle over Brexit Negotiations’, 28 June.

- Rosamond, Ben (2016). ‘Brexit and the Problem of European Disintegration’, Journal of Contemporary European Research, 12:4, 864–71.

- Rzeczpospolita (2016a). ‘Festiwal głupoty’, 4 July, retrieved from Factiva.

- Rzeczpospolita (2016b). ‘Terlecki: Tusk do dymisji’, 7 July, retrieved from Factiva.

- Rzeczpospolita (2017a). ‘Żadnego rozwodu nie będzie’, 3 March, retrieved from Factiva.

- Rzeczpospolita (2017b). ‘Pierwszy spór w rokowaniach’, 31 March, retrieved from Factiva.

- Schimmelfennig, Frank (2018). ‘Brexit: Differentiated Disintegration in the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:8, 1154–73.

- Schimmelfennig, Frank (2020). ‘Politicisation Management in the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy, 27:3, 342–61.

- Schuette, Leonard (2021). ‘Forging Unity: European Commission Leadership in the Brexit Negotiations’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 59:5, 1142–59.

- Statham, Paul, and Hans-Jörg Trenz (2015). ‘Understanding the Mechanisms of EU Politicization: Lessons from the Eurozone Crisis’, Comparative European Politics, 13:3, 287–306.

- Taggart, Paul, Kai Oppermann, Neil Dooley, Aleks Szczerbiak, and Susan Collard (2023). ‘Drivers of Consensus: Responses to Brexit in Germany, France, Ireland and Poland’, German Politics, 1–25.

- The Guardian (2017). ‘German Industry Warns UK Not to Expect Help in Brexit Negotiations’, 9 July.

- The Irish Times (2017). ‘British Pledges on Border “Hard to Reconcile’, Claim EU Negotiators’, 10 December, retrieved from Factiva.

- The Irish Times (2018a). ‘Key Brexit MP: “Astonishing’, No EU Relationship Negotiated, 26 January, retrieved from Factiva.

- The Irish Times (2018b). ‘Hardline Brexiteers Say They Will Not Back May’s Latest Brexit Motion’, 13 February, retrieved from Factiva.

- The Irish Times (2018c). ‘Sinn Féin Seeks Emergency Summit on Irish Brexit Issues’, 23 July, retrieved from Factiva.

- Van Kessel, Stijn, Nicola Chelotti, Helen Drake, Juan Roch, and Patricia Rodi (2020). ‘Eager to Leave? Populist Radical Right Parties’ Responses to the UK’s Brexit Vote’, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 22:1, 65–84.

- Walter, Stefanie (2021). ‘EU-27 Public Opinion on Brexit’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 59:3, 569–88.

- Webber, Douglas (2019). ‘Trends in European Political (Dis)Integration: An Analysis of Postfunctionalist and Other Explanations’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:8, 1134–52.

- Wolff, Sarah, and Stella Ladi (2020). ‘European Union Responses to the Covid-19 Pandemic: Adaptability in Times of Permanent Emergency’, Journal of European Integration, 42:8, 1025–40.