Abstract

When dealing with EU’s rule of law (RoL)-related issues, the Commission has often adopted a forbearance approach and the actions taken have crystallised in soft enforcement mechanisms directed at Poland. However, the use of the Conditionality Regulation as an enforcement instrument in 2022 in relation to (lack of) RoL compliance signalled a change into an assertive approach towards Hungary. Why so? This paper argues that exogenous events may change policy priorities and linkage of issues explain this change. Russian aggression against Ukraine prompted a shift in the priorities of member states’ governments making them more receptive towards EU Commission enforcement actions. The Hungarian government’s friendly attitude towards Russia clashes with the position of most member states and the Commission itself. Orban’s partial isolation makes the Commission more willing to exercise RoL enforcement initiatives. Hence, supranational RoL-related forbearance is, at least in critical situations, affected by the calculus of opportunity that the Commission derives from other policy areas. Empirically, the process is traced through official/public documents and statements made by EU actors.

The war in Ukraine has been a game-changer for EU politics, as the Russian invasion has had serious effects on several EU policy areas. This article focuses on the impact of the war on a long-standing internal EU problem: compliance with and enforcement of the rule of law (RoL). Several authors have anticipated that EU institutions have used this crisis to justify further inaction in RoL enforcement (Bárd and Kochenov Citation2022; Kelemen Citation2022). We nuance this prognosis since we found that, the war against Ukraine has led to changes in the EU's approach to RoL enforcement, which are particularly visible in the actions of the European Commission (Commission).

While generally characterised by a ‘forbearance’ approach (Holland Citation2016; Kelemen and Pavone Citation2023), the Commission’s stance towards the Polish authorities’ RoL non-compliance used to be more severe than towards its Hungarian counterparts (Closa Citation2019). However, since the outbreak of the war, the Commission has adopted a much tougher stance against Budapest, leading to more assertive RoL enforcement policies. In line with what some authors anticipate (Hernández Citation2022; Jaraczewski Citation2022), we link this change in the Commission’s attitude with the different positions taken by the Polish and Hungarian governments with regard to a unified EU response vis-à-vis Russia. While Poland strongly and repeatedly condemned the Russian aggression, Hungary has adopted a pro-Moscow and anti-sanctions position. Warsaw’s stance is consistent with that of most national governments and the EU, whereas Budapest’s position has somewhat isolated this government inside the Council. Thus, we argue that the Commission’s differential stance results from prioritising the EU’s response to the war over RoL enforcement policies. This combines both prioritising another issue linked to the RoL and taking stock of national governments’ preferences on the link between the two. Here, enforcement on the secondary issue becomes a tool to try to bring about compliance with the priority issue, while forbearance is used to reward efforts to advance it. This article contributes to the literature by introducing nuance to the notion of forbearance: at least in the case of the Commission’s law enforcement action, this depends on its calculus of national government preferences. Whilst these may lead to forbearance, the Commission may revoke this forbearance (i.e. enhance its enforcement activity to bring member states back into compliance) when the priorities of national governments concerning other issues indicate that it can instrumentalise enforcement to gain support for the preferred option (for both a majority of governments in the Council and itself).

The article is organised as follows. First, we draw on the literature on forbearance, prioritisation of policy issues, and issue-linkage. We argue that the Commission anticipates the effects of its actions in the Council to decide on enforcement (Closa Citation2019; Kelemen and Pavone Citation2023). So far, authors have examined this anticipation as endogenous to RoL, in isolation from other issues. This article argues that other policy areas (not necessarily directly related to the RoL) may affect the Commission’s RoL enforcement approach and prove key to explaining the revocation of forbearance. Second, we present the research design of the article. We identify three different approaches (2010–2018; 2019–2021; 2022) in the Commission’s RoL enforcement practices, and lay particular focus on the most recent period. To do so, we rely on evidence comprising public statements and actions of EU actors and use process-tracing to identify causal mechanisms. Third, we present and discuss our findings. First, we rule out alternative explanations to our hypothesis. Following this, we trace national governments’ responses to the Ukraine crisis, paying particular attention to the different responses in Poland and Hungary, and how the issue has been linked to RoL-related matters, especially funding and the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). The Commission takes stock of the shifting priorities in the Council, and redirects its RoL enforcement action accordingly, prioritising a strong and cohesive Union response to the Russian invasion and seeking to use the RoL as leverage vis-à-vis national governments whose position does not converge with the preferred one concerning the war. Regardless of their different responses to the Ukraine crisis caused by Russian aggression, both the governments of Poland and Hungary instrumentalised it to blackmail the Commission and the Council to deliver RRF funds without carrying out the necessary RoL reforms in their countries. We conclude that forbearance depends on both prioritisation and issue linkage, which can lead to its adoption and its revocation.

Explaining the Commission’s shift on RoL enforcement practices since the outbreak of the war

Explaining the Commission’s change of course in terms of RoL enforcement necessarily requires a review of the existing literature on this issue. The RoL crisis has attracted the attention of several scholars (Closa and Kochenov Citation2016; Coman Citation2022), and most research largely blames the Union’s inability to bring compliance back on track on the Commission’s soft approach towards offending governments (Kelemen Citation2022; Kochenov Citation2019; Pech and Scheppele Citation2017; Uitz Citation2019). Understanding enforcement as ‘public action with the objective of preventing or responding to the violation of a norm’ (Röben Citation2010), the Union has an ample arsenal of RoL enforcement instruments (Closa and Kochenov Citation2016; Coman Citation2022). This includes preventive and reactive mechanisms, as well as soft and strong measures. Strong enforcement mechanisms are those that bring about compliance through sanctions. Falling into this category, the Union disposes of two instruments designed to deal with systemic breaches of the RoL. First, Art.7 TEU allows the Council to issue recommendations (on the basis of a 4/5 majority) or even impose sanctions (including the suspension of the national government’s voting rights in the Council, on the basis of unanimity) to a member state if it considers that the government systematically jeopardises or violates the fundamental values of Art.2 TEU. Second, the 2020 Conditionality Regulation links the disbursement of EU funds to compliance with the RoL. The Conditionality Regulation applies to the 2021–2027 Multiannual Financial Framework, including the RRF. Although its legal basis rests on Art. 322 TFEU and it is therefore a budgetary instrument, both practitioners and academics regard it as a RoL enforcement tool (European Parliament Citation2021, Citation2022; Pech Citation2022; Platon Citation2021; Scheppele et al. Citation2020b). The Commission can trigger both instruments. The Commission is not the only body that can promote the activation of Art.7, as the European Parliament (EP) can also trigger it, while the activation of the Conditionality Regulation is entirely and solely the Commission’s prerogative.

Finally, the Commission also uses the infringement procedures (Art.258 TFEU) which, although not specifically designed to address systemic violations of fundamental values, but breaches of specific Treaty provisions, are often considered as a crucial instrument in the Union’s RoL ‘toolbox’ (Scheppele Citation2016; Scheppele et al. Citation2020a). Infringement procedures, therefore, need to be taken into consideration in any discussion about strong RoL enforcement actions, even though the institution empowered to sanction is the EU’s Court of Justice (CJEU).

Explanations that point to a deficit of resources to ensure compliance with the RoL should therefore be dismissed, given the extensive ‘toolbox’ of enforcement instruments at the Commission’s disposal. Instead, a preference for forbearance seems to have prevailed. Forbearance is understood as ‘the intentional and revocable nonenforcement of law’ (Holland Citation2016). Kelemen and Pavone (Citation2023) extend the conceptual framework of forbearance, initially designed for national contexts, and give it a supranational dimension: the wish to rekindle intergovernmental support for its policy agenda explains the general decline of the Commission’s enforcement practices in relation to EU law in recent years. Consistently, the Commission’s decision not to enforce or to do so softly concerning RoL (Kelemen Citation2022; Kochenov Citation2019; Pech and Scheppele Citation2017; Uitz Citation2019) is partially explained by the strong influence of the Council on enforcement procedures, which deters the Commission from acting when it does not expect to garner sufficient support in the former, fearing ‘several negative consequences’ (Closa Citation2019; Kelemen Citation2017). Likewise, considerations on the possible reaction of the Council explain the differences in the Commission’s use of some enforcement instruments, specifically Art.7.1, used against Poland but not Hungary (Closa Citation2019).

The Council normally has the last word in deciding whether to apply sanctions. As the operation of the Council relies on the aggregation of individual preferences to achieve high levels of consensus even when unanimity is not required (Closa Citation2019; Heisenberg Citation2005), pointing the finger at a national government owing to its RoL offences might create tensions that hamper efforts to achieve consensus. The 2000 Haïder affair in Austria is a case in point. Bilateral sanctions imposed by member states not only resulted in the Austrian government threatening to block EU decision making in the Council, but also triggered a rally-round the flag effect in Austrian public opinion (Falkner Citation2001; Schlipphak and Treib Citation2017). Following with this negative experience, national governments have watered down RoL enforcement action in the Council in recent years (Pech Citation2019, Citation2020; Priebus Citation2022). Therefore, the Council has normally been reluctant towards RoL enforcement, although it has shown greater tolerance towards Hungary than Poland as documented by Closa (Citation2019).

The partisanship argument is the most widely accepted explanation (Herman et al. Citation2021; Kelemen Citation2017, Citation2020) to decipher the Council’s protective attitude towards Hungary and not towards Poland. EU party politics allowed the EPP to shield Fidesz party in exchange for seats at the EP and ‘an ally of EPP governments in the Council’ (Kelemen Citation2020). Similarly, Herman et al. (Citation2021) confirmed that EPP Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) were less likely to vote for a resolution targeting Hungary and pointed out the Council’s need to broaden consensus in decision-making processes as an explanation. However, the partisanship argument falls short in explaining the current turn of events: neither Polish PiS nor Hungarian Fidesz are any longer protected under the umbrella of any big EP family, forcing us to seek alternative explanations.

Forbearance is revocable by definition (Holland Citation2016), although the conditions under which this revocation occurs in the supranational context have not been comprehensively examined. Kelemen and Pavone (Citation2023) argue that the revocation of forbearance has proven to be a ‘difficult and contentious’ process since national governments and the Commission itself have got used to it and prefer to avoid confrontation. Considering that the expectation that the Council will refuse to endorse enforcement is a key dynamic to understand forbearance in the Commission’s approach to RoL non-compliance (Closa Citation2019), we argue that anticipation of the Council’s support for enforcement actions also plays a role in its revocation. Nevertheless, while supranational forbearance is argued to be general in scope (Kelemen and Pavone Citation2023), its revocation can also be targeted, i.e. directed to only one member state and/or policy area. We also argue that the revocation of supranational forbearance can be triggered by an exogenous event, and, accordingly, that the war in Ukraine has activated the revocation of the Commission’s RoL forbearance in relation to Hungary.

The rationale is as follows: the Commission forfeits its previous choices (inaction on law enforcement) and choses to act when it anticipates political payoffs from this decision. The literature on how governments prioritise problems and on issue-linkage sheds light on this underlying logic in the context of the Ukraine crisis.

Political actors ‘set priorities and change these from time to time as new crises emerge’ (Jones and Baumgartner Citation2005). Thus, the amount of attention paid to political issues is not constant over time, but rather changes as perceived urgency (Jones and Baumgartner Citation2005). The more visible the policy domain, the easier for it to become an active agenda item (Kingdon Citation2014). This might be helpful to explain why exogenous events, particularly those related with security aspects, which are often highly visible, easily occupy prominent places in decision-makers’ agendas. Conversely, problems related to the RoL do not attract attention so easily, as a slow deterioration of democratic conditions is more difficult to perceive, and especially since the RoL itself is often even argued to be an abstract concept. The Commission is aware of the intergovernmental distributional conflict that arises from crisis, i.e. the fact that consequences and costs affect member states differently (Moravcsik Citation1993; Schimmelfennig Citation2018), and it prioritises an ongoing unified EU response vis-à-vis Russia while other issues are left on the backburner.

We hypothesise that the different positions adopted by the governments of Poland and Hungary explain the revocation of the Commission’s forbearance only in the Hungarian case: a confrontational attitude in the prioritised issue is penalised through action on the secondary one. The literature on issue-linkage has broadly explored how a bargaining party ‘introduces a new issue into the dispute’ (Lacy and Niou Citation2004) to gain leverage in a negotiation. Indeed, the Commission has occasionally used ‘urgency’ to link issues that could provide the member states ‘with the motivation’ to adopt proposals during a crisis (Vaagland Citation2021). Issue-linkage strategy implies a negative dimension, referred to by Hovi and Skodvin (Citation2008) as ‘a threat: unless country B does as country A wants on issue X, country A will use issue Y to harm country B’. Mckibben (Citation2010) indicates that the issues that the Commission links in its proposals may be the result of the ‘anticipation of the constellation of interests among the member states […] Thus, member states can also indirectly influence the issues laid out’, creating a problem of endogeneity.

Therefore, the argument works as follows: the Commission, which prioritises a coherent and cohesive EU response to the events in Ukraine vis-à-vis Russia, takes stock of the national governments’ preferences on the Ukraine crisis and the RoL issue. As the former is a priority policy field vis-à-vis the latter in the Council, it therefore lets the RoL crisis take a subordinated position as a second-order issue, and uses the enforcement mechanisms as a bargaining chip to ‘reward’ efforts (by Poland) and ‘sanction’ dissent (by Hungary) in the prioritised matter. Forbearance is thus revocable when enforcement can be used to try to rekindle intergovernmental support in a prioritised issue.

Research design

The outcome: enhanced assertiveness in the Commission’s enforcement policies

This article aims to explain a given outcome: the change in the Commission’s forbearing stance on RoL enforcement with regard to Poland and Hungary since the outbreak of the Ukraine war. To establish such an outcome, we first compare the Commission’s RoL enforcement practices before and after the war to determine whether its approach has in fact changed. We draw empirical evidence from official Commission documents and Commissioners’ statements. This evidence can be consulted in Online Appendix I. In the main text, the endnotes refer to observation numbers in Online Appendix I. From 2015 to 2021, the evidence on the outcome is classified under the category ‘Commission activation of RoL enforcement instruments’. For Commission 2022 enforcement activity, we looked at actions related to the MFF and the RRF, as they are intrinsically linked to the use of the RoL Conditionality Regulation. Hence, these are classified under the category ‘Rule of law status in Hungary and Poland and demands for funds/RRF’.

The Commission’s approach can be divided into three periods. The following table summarises the main actions implemented by the Commission in each period ().

Table 1. Evolution of Commission’s initiation of RoL enforcement actions.

By 2018, the Commission had triggered all the RoL mechanisms at its disposal against the Polish government. It launched the RoL Framework as a pre-step towards the activation of Art.7,Footnote1 issued four recommendations,Footnote2 and activated Art.7.1.Footnote3 The Commission also pushed forward the Art.7.1 procedure by requesting the Council to conduct hearings on Poland.Footnote4 However, the Commission did not activate any of these mechanisms against Budapest, although its conditions for liberal democracy deteriorated further than in Warsaw (see V-DEM reports from 2017 to 2020) and despite the fact that the EP requested it to do so.Footnote5

From 2019 to 2021, the Commission’s role as the promoter of RoL enforcement actions froze. The Commission decided not to activate the Conditionality Regulation until the CJEU ruled on its legality,Footnote6 but in November 2021 it sent letters to Warsaw and Budapest about serious RoL concerns. The letters did not entail the activation of the formal Conditionality procedure but rather were ‘a mechanism of clarification’.Footnote7 RoL-related concerns prevented the Commission from greenlighting Poland’s and Hungary’s RRF plans.

The Ukraine war started in February 2022, a few days after the CJEU upheld the legality of the Conditionality Regulation. From April to December, the Commission launched the Conditionality procedure against Hungary by sending the formal letter of notification,Footnote8 and advanced a proposal to the Council to cut €7.5 billion in funding,Footnote9 although it also gave the green light to the Hungarian RRF plan.Footnote10 As for Poland, in early June the Commission unlocked the Polish RRF plan.Footnote11 However, in October, it decided to withhold €75 billion in payments due to RoL concerns.Footnote12 Although the national RRF plans were approved, the Commission made clear that any payments would require serious changes in these countries’ RoL statusFootnote13. By the end of 2022, neither Hungary nor Poland had received any RRF payments.

The Commission’s stance in relation to infringement proceedings has been substantially different during the three periods, as reflected by the data presented in Online Appendix III: it has used this tool more frequently against Budapest than against Warsaw. Since the Fidesz party came to power in 2010 until 2022, a total of 16 infringement procedures related to the RoL have been initiated against Hungary, 14 of them from 2015 onwards. This is almost double the number of infringement proceedings initiated against Poland in the same period (a total of 8), i.e. since the PiS party came to power in 2015. This supports the argument that, in anticipation of the Council’s refusal to adopt RoL enforcement measures against Hungary, the Commission preferred to resort to a procedure entirely independent from the Council to address RoL status in this member state. However, it should be noted that the nature of the infringement proceedings initiated against these two governments is significantly different. The reasons that explain these differences in approach are beyond the scope of this article. But the fact that only one infringement case levelled against Hungary is related to judicial independence (although serious concerns in this regard exist, see for example EP’s Art.7.1 activation proposal) tentatively suggests that the Commission has not used the infringements as extensively as it could have (Scheppele Citation2016; Scheppele et al. Citation2020b; Kelemen and Pavone Citation2023). Thus, in order to enforce RoL compliance, the Commission acted indirectly via other issues, the enforcement of which relied on a sound technical and legal basis (Anders and Priebus Citation2021; Bárd and Kazai Citation2022).

Inducing explanations

In order to explain the change in the Commission’s approach to RoL enforcement in Poland and Hungary after the Russian invasion of Ukraine we rely on process-tracing, ‘an analytical tool for drawing descriptive and causal inferences from diagnostic pieces of evidence, often understood as part of a temporal sequence of events or phenomena’ (Collier Citation2011). Therefore, we attempt to identify causal-process observations (CPOs), i.e. ‘pieces of data that provide information about context, process, or mechanism and contribute distinctive leverage in causal inference’ (Seawright and Collier Citation2010). Our aim is not to provide a general theory of forbearance revocation, but rather, as Blatter and Haverland (Citation2014) point out, to ‘contribute to the debate about which pathways and causal configurations make a certain type of outcome possible’ by examining a possible pathway through which this revocation can occur. The presentation of our results is inspired by Pavone and Stiansen’s (Citation2022) study on the shadow effect of courts: first we present ruled-out explanations; second, we present the triggering event and the process trace; and, finally, we explain the mechanisms that link cause and outcome.

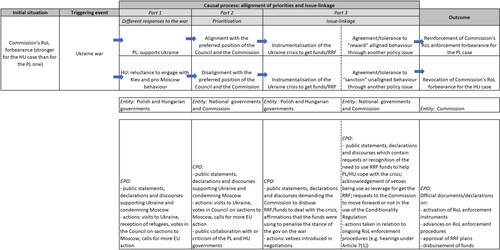

summarises the sequence of actions, entities, and CPOs in our argument. We have relied on Beach’s (Citation2022) definition of the ‘productive’ account of process-tracing, i.e. mechanisms are understood as ‘productive linkages in actual cases’. We compare the paths followed in the Polish and Hungarian instances to identify why the revocation of forbearance has only applied to the latter.

Figure 1. Process of revocation/maintenance of Commission’s RoL forbearance: actions, entities and CPO.

Source: own elaboration on the basis of Beach (Citation2022) and Pavone and Stiansen (Citation2022).

Methodological consideration: As clarified in the main text, it is difficult to ilustrate whether the ‘prioritisation’ and ‘issue linkage’ mechanisms are originated by national governments or by the Commission, hence both are included as ‘entities’ since the CPOs are traceable in the actions and statements of both.

In the empirical section we also explore, first, whether the change in the Commission’s behaviour is not justified by a significant change in the RoL status in these member states and, second, whether it is not the result of the introduction of third issues other than these countries’ stance on the war against Ukraine, the negotiation of sanctions, and the adoption of the RRF plans that could explain the change in the Commission’s behaviour regarding RoL enforcement. If we can rule out these explanations, we can tentatively reinforce our argument that the reactions of both administrations to the war in Ukraine and the imposition of sanctions on Russia explain changes in EU rule of law enforcement-related actions.

Sources for evidence

The evidence to argue for causal mechanisms covers from February to December 2022. It can be consulted in Online Appendix I, including 526 statements and actions from national governments, diplomats, and EU actors from 24 February to December 2022. These statements constitute our ‘evidentiary base’ (Elman and Kapiszewski Citation2014). Although it is impossible to cover all the events and statements from this time bracket, the list is comprehensive enough for a thorough examination of the issue at hand.

In order to trace positions in the Council, governments’ official statements, governments’ official web pages, statements by government members in their official social media accounts (Facebook and Twitter), and the media have been taken into account. Communications and statements are used as primary sources because they concern revealed preferences, making it unnecessary to decipher hidden ones in this case. The aim is to ‘measure’ the preferences of the Council for or against assisting Ukraine and for or against RoL enforcement, but no need exists to consider national governments’ motivations to adopt one position or the other. Moreover, revealed preferences and the actual position the governments took in voting are highly consistent, and, therefore, these revealed preferences are regarded as reliable indicators. In instances in which governments appear reluctant to adopt the Commission’s proposals (both in terms of sanctions and RoL enforcement instruments), these are publicly expressed.

The evidence has been classified into several categories that correspond to topics that have become prominent since the beginning of the war. The topics include: ‘Reactions to the invasion of Ukraine and the imposition of sanctions on Russia’; ‘Ukrainian refugee crisis’; and ‘Rule of law status in Hungary and Poland and demands for funds/RRF’. Given word count limitations, all the evidence used to substantiate the interpretation in Section 4 is presented in Online Appendix I. In the text, the endnotes mirror the numbers used in Online Appendix I. Methodological considerations for the collection of evidence can be consulted in the Research Protocol (Online Appendix II).

Finally, to rule out that changes in the Commission’s approach are a result of a change in Polish and Hungarian RoL status, the data provided by the V-DEM Democracy Reports for 2022 (Boese et al. Citation2022) and 2023 (Papada et al. Citation2023), which contain information for 2021 and 2022, respectively, has been traced. This comprises the Liberal Democracy Index (LDI), which reflects electoral and liberal components of democracy; and, more specifically, the Liberal Component Index (LCI), which reflects liberal features of democracy, including checks and balances on the executive, respect for civil liberties, the rule of law, and the independence of the legislature and the judiciary. The possibility that changes in the Commission’s enforcement path have been triggered by the introduction of third issues in the negotiation of sanctions and the adoption of the RRF plan has been dismissed on the basis of the evidence presented in Online Appendix II under the category ‘Vetoes to the Global Tax’.

Findings

Discarded explanations

In order to test our argument, we first explore alternative pathways to the hypothesis presented in this article that might have led to the given outcome. The evidence based on democracy and RoL indicators rules out a significant improvement or deterioration of the situation in Poland and Hungary that could explain the Commission’s change of approach in 2022. Similarly, although the introduction of third issues, in particular the adoption of the Global Tax, played a role in negotiations, explanations that point to the use of the veto by the Polish and Hungarian governments as the cause of the Commission’s different attitude must also be dismissed on the basis of evidence traced in public statements and documents related to this issue.

A shift in democratic backsliding

The 2022 and 2023 V-DEM Reports suggest no major changes in either Poland and Hungary in terms of LDI and LCI, although the LCI reported a slight improvement in Poland from 2021 to 2022. Therefore, the Commission’s harder stance on Budapest than on Warsaw does not seem to be sustained by significant changes in the RoL status in either of these two member states ().

Table 2. LDI and LCI for Poland and Hungary according to V-DEM reports.

Based on these indicators and their evolution over the last ten years, V-DEM ranks both countries among the world’s top ten ‘autocratisers’. Poland is currently considered an ‘electoral democracy’, while Hungary is no longer classified as a ‘democracy’ but as an ‘electoral autocracy’. However, the 2023 report indicates that autocratisation has slowed down or even stalled in both countries. Owing to these concerns, EP groups (S&D, EPP, Renew, and Greens/EFA, also with the support of The Left) have repeatedly demanded that no RRF funds be disbursed to either Budapest or Warsaw despite the impact of the Ukrainian crisis.Footnote14

Given the Commission’s past behaviour, and considering that the situation remains critical in both Member States, it would be difficult to expect a revocation of forbearance, a position maintained for several years, solely on RoL grounds. Therefore, this explanation cannot account for the reasons that have led the Commission to revoke forbearance towards Hungary and adopt a softer approach towards Poland.

Veto threats to the global tax

Another explanation for changes in the Commission’s enforcement path is the introduction of a third issue, the approval of the Global Tax, in the negotiation of sanctions and the adoption of RRF plans, which was prioritised over the protection of the RoL. In early April, the Polish government vetoed the approval of the Global Tax, although it denied accusations of holding the Commission hostage to force it to disburse RRF funds.Footnote15 Polish authorities lifted the veto just after the Commission greenlighted its RRF plan in June, a decision followed by Hungary’s announcement of the introduction of its own veto.Footnote16 Several national governments accused Poland of lacking transparent reasons for imposing the veto on the Global Tax and raised suspicions that it did so to unblock RRF funds,Footnote17 a view shared by external partners, such as the US,Footnote18 and some MEPs.Footnote19 Similarly, concerning the subsequent Hungarian veto, suspicions arose that Budapest was trying to blackmail the Commission, as reported by EU diplomats and MEPs.Footnote20

Poland introduced a new vetoFootnote21 in the member states’ package negotiation of 15 December 2022 (which included the Global Tax, financial assistance to Ukraine, approval of the Hungarian RRF plan, and cutting funds to Budapest under the Conditionality Regulation). Diplomatic sources reported great frustration in the CouncilFootnote22 and suspected that the veto was a strategy to push the EU to divert RRF funds to Poland.Footnote23 However, Poland withdrew the veto the same day,Footnote24 with no further consequences.

Threats of a veto on the Global Tax played a role in the negotiations, which was especially visible at several junctures: first, when Poland decided to lift the veto after obtaining Commission approval for its RRF plan on 15 June; second, in the proposal made in early December by a dozen national governments for the Commission to reconsider Hungary’s RoL reforms before going ahead with its funding cut proposal, to persuade Hungary to lift its veto.Footnote25 The proposal was led, among others, by France, which was among the most interested governments in pushing ahead with the Global Tax, a task that was in fact deemed a priority during its Presidency of the EU Council in the first half of 2022. And, finally, in the fact that the Hungarian government tried to gain leverage by introducing new vetoes in the following negotiations, namely on the €18 billion aid package to Ukraine.Footnote26

However, vetoes hardly explain the fact that the Commission has revoked its forbearing approach towards Hungary while upholding it for Poland: both governments introduced vetoes, but the results were very different. Although the Global Tax could have gone ahead without the Polish government, as demonstrated by the reactions to the Hungarian veto, neither the Commission nor the Council put these proposals on the table, displaying a preference to keep Poland on board. Conversely, the Commission advanced the procedure of the Conditionality Regulation for Hungary despite the veto threat (although it also passed its RRF plan). In addition, several national delegations pressed the Commission to move forward on the Global Tax, even without Hungary.Footnote27 Similarly, both the Commission and the Council signalled their intention to move forward on the Ukraine aid package despite Hungary’s opposition.Footnote28 Thus, although the vetoes allowed Hungary to push certain delegations to waver in their support for the suspension of funds, not all of them agreed,Footnote29 nor did the Commission backtrack on its proposal.Footnote30 Given these differences, it is difficult to argue that the Global Tax negotiations account for the different attitude of the Commission and the Council regarding RoL enforcement, although they played a role at certain stages. Therefore, it is probably a third factor that explains the different treatment of Poland and Hungary concerning both RoL enforcement and the Global Tax negotiations.

Triggering event and necessary conditions: the war in Ukraine and the different responses of the Polish and Hungarian governments

In this section, we explore our argument by tracing the different responses of the Polish and Hungarian governments to the war and the reactions they triggered in the Council and the Commission. We draw on evidence from documents and public statements, which allow us to observe the convergence or misalignment of priorities in terms of the response to the war, as well as their relationship to RoL enforcement-related events that took place during these months.

The Polish government’s reaction to the war

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 sparked reactions from all EU national governments. The Polish authorities showcased a strong commitment to support Ukraine and to impose EU sanctions on Moscow.Footnote31 PM Mateusz Morawiecki visited KievFootnote32 and the Polish government expressed its support of Ukraine’s EU candidacy statusFootnote33 and of the provision of reconstruction assistance.Footnote34 Poland also spearheaded the reception of Ukrainian refugees:Footnote35 as of 31 May 2022, 3.5 million of the total 5 million Ukrainians crossing into the EU did so into Poland (Frontex Citation2022), of which 1,246,315 had requested asylum in the country by July 2022 (UNHCR Citation2022). Warsaw repeatedly demanded economic support from the Commission to assist Ukrainian refugees.Footnote36

In the first months of the war, support for Ukraine and calls for sanctions against Russia were also particularly strong among Baltic member states (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania),Footnote37 which often carried out common actions with the Polish government.Footnote38 Eastern member states also supported UkraineFootnote39, publicly showing their alignment with the Polish stance,Footnote40 and particularly agreed with the Ukrainian EU candidacyFootnote41. As for the refugee crisis, the Eastern governments also acted in a coordinated manner to ask the EU for help for the most affected member statesFootnote42. Some governments of the so-called RoL Friends made public appearances with the Polish government to express their solidarity and support regarding the refugee crisis (PM of the Netherlands Mark Rutte in March, PM of Belgium Alexander de Croo in April, and PM of Sweden Magdalena Andersson in May) and admitted the need to help Warsaw with financial assistance.Footnote43

The Commission was very supportive of Warsaw regarding the Ukrainian refugee crisis. In March, it visited the borders of Poland, Slovakia, and Romania,Footnote44 and proposed redirecting funds from DG Home towards migration or using money earmarked for regional development.Footnote45 In May, it granted Poland €144.6 million from the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund.Footnote46

In parallel to developments in Ukraine, Polish authorities carried out a series of reforms in the justice system in an attempt to comply with Commission-set milestones to unlock the RRF.Footnote47 In early June, the Commission finally unlocked the Polish RRF plan. The President of the Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, announced that the approval was ‘linked to clear commitments by Poland on the independence of the judiciary’.Footnote48 However, two Commissioners (Frans Timmermans and Margrethe Vestager) voted against the plan, while another three (including the two Commissioners managing the RoL portfolio, Věra Jourová and Didier Reynders, as well as Ylva Johansson) raised concerns on the real improvement of the RoL status in Poland.Footnote49 The governments of Belgium, Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands also raised doubts about unlocking the Polish RRF, although the Netherlands was the only one that abstained in the Council vote.Footnote50

EU officials justified von der Leyen’s decision to approve the Polish plan as a reaction to the refugee crisis and a strategy to drive a wedge between Poland and Hungary.Footnote51 Some commissioners (Valdis Dombrovskis and Paolo Gentiloni) acknowledged the importance of the plan in helping Poland deal with the Ukrainian refugee situationFootnote52 and the energy transition away from Russian supply.Footnote53 Polish authorities celebrated the Commission’s decision to pass their RRF plan,Footnote54 and claimed that the funds were essential for Poland to deal with the Ukraine crisis.Footnote55

Following the EU’s adoption of the RRF plan, the Polish authorities continued their tough rhetoric in favour of sanctions against Russia,Footnote56 often in close coordination with the Baltic states.Footnote57 The Polish government also maintained its demands for financial support from the Commission to help Ukrainian refugees through disbursements from the RRF,Footnote58 although the issue became less relevant over the months. The Commission, as well as national governments, acknowledged the Polish efforts to help Ukraine on several occasions.Footnote59

Serious tensions arose during the summer when the Polish authorities toughened their rhetoric in the face of the Commission’s doubtsFootnote60 about Poland’s compliance with RoL milestones and the decision not to disburse the money for the time being.Footnote61 The Commission decided not to initiate the Conditionality procedure against Poland despite the ongoing problems with RoL, as confirmed by Budget Commissioner on 18 September.Footnote62 However, on 17 October, the Commission decided to withhold €75 billion of EU funds due to RoL concerns.Footnote63 As the year drove to an end (November-December), a number of meetings were held between the Commissioners for Justice and Values and the Polish authorities,Footnote64 who returned to a conciliatory tone and announced further justice reforms.Footnote65 On 30 November, Commissioner Věra Jourová stated ‘I see signals from the side of the government to fulfil the judicial independence milestone and this is a welcomed step. The Polish people deserve these funds’.Footnote66

The Hungarian government’s reaction to the war

The Hungarian authorities refused to take a firm stance against the war. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán disapproved of the Russian invasion but indicated that Hungary should stay out of the war and was reluctant to impose sanctions against Moscow and provide aid to Ukraine.Footnote67 The Hungarian authorities even accused Kiev of interfering in the country’s April elections against the Fidesz party.Footnote68 Hungary’s ties with Russia continued, and Russian President Vladimir Putin even congratulated Orbán on his re-election.Footnote69 The Hungarian government’s soft response to the war caused tensions in the Visegrad 4 group (V4), even leading to the cancellation of a defence ministers’ meeting at the end of March.Footnote70

In contrast, the Hungarian government showed a welcoming attitude towards Ukrainian refugees.Footnote71 The Hungarian authorities requested financial assistance from the Union, including the RRF, to help cope with the humanitarian crisis,Footnote72 but manipulated refugee figures to request additional funding,Footnote73 as reported by NGOs.Footnote74 UNHCR (Citation2022) estimated a total of 27,316 Ukrainian refugees in Hungary by July 2022. The Commission did not visit the Hungarian border, although it did visit other neighbouring Member States affected by the crisis. In May, the Commission granted Hungary €21 million from the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund as part of the resources allocated to the Member States most affected by the crisis.

On 5 April, just a couple of days after Orbán won the election, the Commission announced its intention to ‘move on to the next step and formally launch the rule of law conditionality mechanism’.Footnote75 On 27 April, the Commission sent the Hungarian government the first notification under this procedure.Footnote76 The Hungarian authorities criticised the Commission’s decision to trigger the Conditionality Mechanism, claiming it was the result of Hungary’s reluctance to support Ukraine.Footnote77

The Hungarian soft stance towards the war and its ties with Moscow continued,Footnote78 while its anti-sanctions rhetoric hardened, turning into open vetoes in subsequent negotiations around sanctions.Footnote79 The government put a price on lifting its vetoes and demanded additional EU funding to transform the country’s energy infrastructure through the EU's RePower programme, whose funds are to be channelled through the RRF.Footnote80 Budapest also unilaterally decided to buy additional gas from RussiaFootnote81 and demanded the removal of EU sanctions.Footnote82

The vetoes on energy sanctions drove a wedge between the Hungarian government and the rest of the delegations in the Council. The Baltic governments were highly critical of Hungary vetoing sanction packages and calls for a ceasefire.Footnote83 The Czech Republic, Slovakia, Germany and Austria were wary of sanctions at certain junctures,Footnote84 as were Cyprus, Greece and Malta,Footnote85 but none of them systematically vetoed the packages. The Friends of the RoL (Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Sweden) insisted on weaning the EU from its energy dependence on Russia,Footnote86 and some of them even openly criticised Hungary’s attitude.Footnote87 Budapest’s relationship with Helsinki and Stockholm further deteriorated in later months because of the Hungarian authorities’ delays to approve the accession of Finland and Sweden to NATO.Footnote88 Tensions between Poland and Hungary because of their different stance towards the war also emerged,Footnote89 which hindered their mutual cooperation, although they have subsequently denied such a rift.Footnote90

The Art.7.1 hearing regarding Hungary held on 5 May 2022 broke a participation record: a total of 18 delegations submitted questions, including several eastern member states such as Estonia, Slovenia, Slovakia, Lithuania, and Latvia (the last three were first-time questioners).Footnote91 Afterwards, the Hungarian government expressed on several occasions its willingness to reach an agreement with the Commission and unlock the RRF by addressing some of its RoL concerns.Footnote92 However, the Commission concluded that these attempts were insufficient, and on 18 September proposed to the Council to cut €7.5 billion in funding to Hungary. It also announced 17 corrective measures to be implemented by 19 November for the Hungarian government to access the funds.Footnote93 The Council approved an extension of the initial one-month deadline proposed by the Commission to decide on the funding cuts,Footnote94 although some delegations (Benelux and Ireland) insisted that the Commission should carry out a detailed assessment of whether Hungary had taken corrective measures after 19 November.Footnote95

Hungary continued to criticise the sanctions and kept its energy relations with Russia.Footnote96 In November, Hungary’s veto on €18 billion of EU financial aid to UkraineFootnote97 attracted criticism from some other EU governments, which acknowledged the existence of a link between this decision and Budapest’s aim to pile pressure upon the EU to release funds, an opinion shared by EU Diplomats.Footnote98 Budapest denied such accusations.Footnote99

On 30 November, the Commission formalised its proposal by concluding that Hungary had not taken corrective measures,Footnote100 despite Budapest’s pledge to carry out some reforms.Footnote101 However, the Commission also approved Hungary’s RRF plan. At this point, the Council was split between the governments that pressed the Commission to soften its proposal, including France, Germany, and Italy,Footnote102 and the governments of the Benelux, and the Scandinavian and Baltic countries, which wanted the Commission to withhold the €7.5 billion.Footnote103 Several governments also told Budapest that they would not approve its RRF plan unless it lifted the veto on financial assistance to Ukraine and the Global Tax.Footnote104 As a result, most delegations were irritated with Budapest’s vetoesFootnote105 and its lack of commitment to RoL reforms. In December, the Council decided to cut €6.3 billion of cohesion funds to Budapest,Footnote106 but it also gave the green light to its RRF plan.Footnote107 Orbán lifted the veto.

The causal mechanism: re-alignment of priorities and issue-linkage

As traced in the previous section, the priorities of the Polish government and the rest of governments and the Commission converged, while Hungary entered serious confrontations with both the Commission and some national delegations. Hungarian divergence in the response to the Ukrainian crisis was penalised with the loss of some rule of law alliances and a harsher treatment than Poland in this regard. This section explores in detail how these two mechanisms, re-alignment of priorities and issue-linkage, worked in the revocation of forbearance.

The following table summarises statements coming from national governments and the EU concerning support to Ukraine and the imposition of sanctions on Russia. It clearly displays the alignment of preferences of the national governments in the Council and the Commission, except for Hungary, which appears as the only dissonant voice ().

Table 3. Demands for strong EU reaction vis-à-vis Russia and support for Ukraine.

Although, as noted in the methodological section, the table does not cover all the statements and actions undertaken by national governments and the EU during these months, it shows a clear preference for pro-Ukrainian attitudes in the EU and the national governments, Hungary being the most reluctant government to engage in this common stance (although other actors also expressed reservations at certain junctures). In contrast, the Polish position was widely supported and aligned with the position preferred by both the Commission and most national delegations.

Four key topics have emerged during 2022, three of them directly related with the war in Ukraine. All issues have been perceived as linked to that of RoL, either directly or via demands for additional EU funding (RRF or other resources), which is RoL-conditional, as summarised in :

Figure 2. Issue-linkage among the four key thematic areas.

Source: own elaboration [colour on line only].

Total: 142 pieces of evidence (statements/actions).

The X-axis reflects the main theme of the statement, while links are made to secondary themes that also appear/arise from the statement.

Those issues related to energy (in)dependence and inflation crisis have been included under the category ‘Reactions to the invasion of Ukraine and sanctions’ imposition to Russia’ in order to simplify the graphic and since concerns on these topics emerged from the war.

![Figure 2. Issue-linkage among the four key thematic areas.Source: own elaboration [colour on line only].Total: 142 pieces of evidence (statements/actions).The X-axis reflects the main theme of the statement, while links are made to secondary themes that also appear/arise from the statement.Those issues related to energy (in)dependence and inflation crisis have been included under the category ‘Reactions to the invasion of Ukraine and sanctions’ imposition to Russia’ in order to simplify the graphic and since concerns on these topics emerged from the war.](/cms/asset/ea43645d-23f9-44cd-8137-c8bbd9604efe/fwep_a_2268492_f0002_c.jpg)

The Polish and Hungarian governments, recognising the existence of these links, tried to use them to further their own goals of accessing EU funds. This was particularly visible, first, in the instrumentalization of the Ukrainian refugee crisis and, second and foremost, in the negotiations around the Global Tax. However, these attempts to use the approval of the Global Tax as leverage to gain access to funds from the RRF do not explain the Commission’s differential approach to Poland and Hungary in terms of RoL enforcement.

Conversely, issue-linkage worked here as a mechanism for the Union to ‘reward’ or ‘sanction’ aligned and misaligned behaviour. The reception and protection of Ukrainian refugees, as well as the imposition of sanctions on Russia, were political priorities for both the Commission and the Council. Thus, RoL enforcement was relegated as a second-order issue, even (to some extent) for the most pro-RoL governments. Acknowledging Poland’s leading role in the Ukraine crisis and demonstrating European solidarity towards this member state was prioritised over the possibility of using the approval of the RRF plan as leverage to push the Polish government to undertake significant judicial reforms. Some voices in the Council raised concerns, but not open opposition. Therefore, the Commission, taking stock of the Council’s majority stance, chose to ‘reward’ Poland, kept it on board with the Global Tax, and let aside (to a certain extent) enforcement to maintain cohesion.

The Hungarian government’s attitude not only further eroded the relationship with the Commission, but also with its traditional anti-RoL enforcement allies, who distanced themselves from Budapest, leading to a certain isolation of Orbán in the Council. However, this isolation was somewhat eased at the end of the year, when some governments demanded that the Commission soften its proposal to cut funds under the conditionality procedure in order to convince Orbán to lift his vetoes. In fact, the final amount of the funding cut approved by the Council was lower than that proposed by the Commission, and the Hungarian RRF plan was approved. Nonetheless, it can be argued that the traditional reluctance towards using funding as a RoL enforcement tool was set aside by most national governments in recognition of the need to keep a united front concerning sanctions on Russia and aid to Ukraine. Budapest’s ongoing misalignment on this point was therefore ‘sanctioned’ with the loss (though not complete) of the traditional protection it enjoyed in the Council in terms of RoL enforcement.

The following figure summarises the results and how the process worked as explained here (). It should be noted that, although the use of RoL enforcement instruments has changed, the outcome has been fairly similar: the Commission has withheld or cut funding to both Member States, and neither of them has received any payments from the RRF, even though both plans were finally given the green light in 2022. This suggests that, while in this instance the enforcement of RoL has been instrumentalised to ensure a cohesive EU response to the war, the Commission has recognised the potential value of using funding to push for reforms. Therefore, perhaps the Commission does not want to lose this leverage, even if in the Polish case it is currently using means other than the Conditionality procedure (e.g. not to disburse the RRF funds) to maintain it.

Conclusions

The change in the Commission’s attitude towards Hungary and Poland concerning enforcement cannot be explained by a significant change in the RoL status of these member states, which remains critical despite the announced reforms, but is arguably the result of the different positions of these two governments on the war against Ukraine. The Commission’s activation of the Conditionality Regulation against Hungary not only constitutes a key shift from its previous behaviour, but it also sheds light on the conditions under which the revocation of forbearance can occur. When launching RoL enforcement mechanisms, the Commission considers the Council’s preferences regarding RoL enforcement itself, while anticipating reactions on a number of issues and seeking convergence of priorities with national governments. Consequently, alignment on a priority issue can neutralise (or activate) enforcement on a secondary issue.

Recent developments appear to be consistent with the idea that, for EU institutions and national governments, there is always a more important crisis than that caused by RoL non-compliance. Both the Council and the Commission treated the RoL as a secondary issue in the face of the Ukraine crisis. We have therefore identified that the revocation of forbearance can be caused by an exogenous shock. This is consistent with what the literature on agenda-priorities anticipates: the most visible issues are more likely to occupy prominent places in the agenda, and more efforts to be devoted to find a common EU response. The exogenous shock has led to changes in the position of some national governments’ in the RoL enforcement issue, as a result of the priority assigned to addressing the Ukrainian crisis. Here, the Commission has demonstrated to be able to exploit these shifts to pursue its own priorities, as long as they coincide with the preferred option in the Council.

Examining the RoL crisis by considering its relations to other EU crises might bring mechanisms of institutional action regarding RoL enforcement that have been neglected to date into the limelight. The dynamics of issue priority and issue linkage may have contributed to explain, at least partially, the failure to bring the Polish and Hungarian governments back to compliance in previous occasions. Therefore, the suboptimal result achieved in tackling the RoL crisis may be to a certain extent explained by the achievement of optimal results in other policy areas linked with the former by the Commission and the other national governments. Evidence suggests that this may be the case, as the different activity of national governments during the Art.7 hearings could be the result of their decision to act or not based on their calculations about other matters. This presents a challenge in research terms, as the issue of endogeneity arises: it is difficult to establish which is the actor that bears original responsibility for issue prioritisation. Further research is needed to clarify the behavioural mechanisms at play in these dynamics, but the Ukraine crisis provides a solid point of departure to expand knowledge into this field through other case-studies. Finally, Commission revocation of forbearance may end up when the priorities of national governments concerning other issues indicate that enforcement of RoL compliance may block agreement on these issues. In short, time will tell whether revocation of forbearance is a permanent or temporary situation.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (812 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (231.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sonia Rodrigo for her research assistance in expanding the annexes. We would also like to thank the WEP anonymous reviewers and editors, who provided excellent comments on the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gisela Hernández

Gisela Hernández is currently developing her Ph.D. project on rule of law enforcement in the European Union at the Institute of Public Goods and Policies of the Spanish National Research Council (IPP-CSIC) and Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (UAM). She has been visiting researcher at the Institute for European Studies of the Université libre de Bruxelles (IEE-ULB). She has published in Politics and Governance and The Hague Journal on the Rule of Law. [[email protected]]

Carlos Closa

Carlos Closa is Vice-President for Organisation and Institutional Relations of the Spanish National Research Council and Research Professor at the Institute of Public Goods and Policies. He is also Professor at the School of Transnational Governance at the EUI. He was co-editor of the European Political Science Review until 2021. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 See Online Appendix I, observation no. 274

2 275, 276, 277, 278, 279

3 280

4 282, 283

5 281

6 284

7 285

8 272, 93

9 273, 300, 304, 327, 452, 454

10 455

11 173, 181

12 382

13 172, 451, 453, 457, 459

14 44, 169, 186, 187, 206, 207, 219

15 76, 77, 141

16 194, 195, 196, 213

17 78, 141

18 168

19 199

20 196, 215, 461

21 527

22 515, 516

23 518, 521

24 520

25 462, 463, 464, 491

26 490

27 200, 266, 531, 532, 533, 534, 535, 536

28 497, 537, 538, 493, 494

29 478, 479, 480, 481, 482, 483, 484, 485, 486, 497, 488

30 496

31 11, 24, 40, 45, 56, 62, 69, 104, 166

32 22

33 32

34 15, 19, 22

35 55, 117

36 52, 105

37 3, 4, 5, 25, 26, 27, 37, 38, 39, 41, 42, 43, 63, 64, 65, 125, 134, 137, 139, 160, 161

38 40, 45, 69

39 54, 140

40 20, 23

41 6, 7, 10, 28, 29, 34, 35

42 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 108, 109, 110, 111, 138

43 13, 47, 46, 48, 49, 91, 92, 112

44 12

45 17

46 133

47 149

48 173, 181

49 172, 174, 175, 176, 177

50 188, 189, 190, 191

51 170, 171

52 528

53 529

54 182, 289, 324

55 289, 325

56 247, 258, 270, 294, 338, 402, 426, 433, 443, 446, 477, 505

57 242, 244, 245, 246, 248, 253, 254, 255, 295, 296, 297, 339, 340, 341, 390, 391, 392, 427, 428, 429, 444, 447, 506, 507, 508

58 180, 325

59 470, 471

60 236

61 237, 239, 240, 251, 252, 344, 404, 414

62 331, 529, 530

63 382

64 407, 408, 458, 459

65 501, 512, 513, 514

66 458

67 1, 8, 21, 25, 60, 59, 68

68 57, 72

69 73

70 53, 54

71 2, 292, 293

72 31, 102, 103

73 61

74 58

75 79

76 93

77 75, 94, 146

78 83, 113, 114, 156, 193, 269, 290, 291, 305, 329

79 84, 120, 123, 157, 185, 197, 217, 224, 225, 226, 229, 232, 233, 261, 268

80 130, 143, 144, 147, 148, 165, 167

81 221, 222, 223, 231, 241, 257, 287, 288

82 343

83 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 262, 263, 264

84 30, 81, 85, 118, 119, 122, 124

85 348, 349, 350

86 67, 80, 82, 89, 163

87 184, 228, 333, 361

88 403, 435, 436, 437

89 87, 88

90 260, 299, 330

91 306 to 323

92 146, 192, 208, 209, 210, 249, 250, 301, 302, 303, 326, 336, 337

93 327, 354

94 540

95 372, 373, 374, 376

96 342, 345, 346, 351, 352, 362, 366, 367, 368, 369, 377, 378, 379, 384, 393, 394, 396, 397, 399, 400, 421, 431, 438

97 411

98 410, 419

99 448, 450

100 451, 452, 453, 454, 457, 472

101 406

102 462, 463, 464, 473, 474, 475, 491

103 465, 466, 467, 468, 469, 478

104 484, 485, 486, 487, 488

105 492

106 499

107 500

References

- Anders, Lisa H., and S. Sonja Priebus (2021). ‘Does It Help to Call a Spade a Spade? Examining the Legal Bases and Effects of Rule of Law-Related Infringement Procedures against Hungary’, in Astrid Lorenz and Lisa H. Anders (eds.), Illiberal Trends and Anti-EU Politics in East Central Europe. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 235–62.

- Bárd, Petra, and Dimitry Kochenov (2022). ‘War as a Pretext to Wave the Rule of Law Goodbye? The Case for an EU Constitutional Awakening’, European Law Journal, 27:1-3, 39–49.

- Bárd, Petra, and Viktor Zoltán Kazai (2022). ‘Enforcement of a Formal Conception of the Rule of Law as a Potential Way Forward to Address Backsliding: Hungary as a Case Study’, Hague Journal on the Rule of Law, 14:2-3, 165–93.

- Beach, Derek (2022). ‘Process Tracing Methods in the Social Sciences’, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.176

- Blatter, Joachim, and Markus Haverland (2014). ‘Case Studies and (Causal-) Process Tracing’, in Isabelle Engeli and Christine Rothmayr Allison (eds.), Comparative Policy Studies. Research Methods Series. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 59–83.

- Boese, Vanessa A., et al. (2022). ‘Democracy Report 2022 Autocratization Changing Nature?’, V-DEM.

- Closa, Carlos (2019). ‘The Politics of Guarding the Treaties: Commission Scrutiny of Rule of Law Compliance’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:5, 696–716.

- Closa, Carlos, and Dimitry Kochenov (2016). Reinforcing Rule of Law Oversight in the European Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Collier, David (2011). ‘Understanding Process Tracing’, PS: Political Science & Politics, 44:4, 823–30.

- Coman, Ramona (2022). The Politics of the Rule of Law in the EU Polity: Actors, Tools and Challenges. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Elman, Colin, and Diana Kapiszewski (2014). ‘Data Access and Research Transparency in the Qualitative Tradition’, PS: Political Science & Politics, 47:01, 43–7.

- European Commission (2014). ‘Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council a New EU Framework to Strengthen the Rule of Law’, COM/2014/0158 final.

- European Parliament (2021). ‘Rule of Law: Parliament Prepares to Sue Commission for Failure to Act’, Press Release, 10-06-2021.

- European Parliament (2022). ‘Rule of Law Conditionality: Commission Must Immediately Initiate Proceedings’, Press Release, 10-03-2022.

- Falkner, Gerda (2001). ‘The EU14’s “Sanctions” against Austria: Sense and Nonsense’, ECSA Review, 14:1, 14–5.

- Frontex (2022). ‘5.3 Million Ukrainians Have Entered EU Since The Beginning of The Invasion’, Frontex News 02-06-2022, available at https://www.frontex.europa.eu/media-centre/news/news-release/5-3-million-ukrainians-have-entered-eu-since-the-beginning-of-invasion-HbXkUz.

- Heisenberg, Dorothee (2005). ‘The Institution of ‘Consensus’ in the European Union: Formal versus Informal Decision-Making in the Council’, European Journal of Political Research, 44:1, 65–90.

- Herman, Lise E., Julian Hoerner, and Joseph Lacey (2021). ‘Why Does the European Right Accommodate Backsliding States? An Analysis of 24 European People’s Party Votes (2011–2019)’, European Political Science Review, 13:2, 169–87.

- Hernández, Gisela (2022). ‘European Commission Launches Rule of Law Conditionality Mechanism against the Hungarian Government’, UKICES, Commentary, 18 April 2022.

- Holland, Alisha C. (2016). ‘Forbearance’, American Political Science Review, 110:2, 232–46.

- Hovi, Jon, and Tora Skodvin (2008). ‘Which Way to U.S. Climate Cooperation? Issue Linkage versus a U.S.-Based Agreement’, Review of Policy Research, 25:2, 129–48.

- Jaraczewski, Jakub (2022). ‘Unexpected Complications: The Impact of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on the Rule of Law Crisis in the EU: An Anti-Rule of Law Alliance’, VerfBlog, 23 December 2022.

- Jones, Bryan D., and Frank R. Baumgartner (2005). The Politics of Attention: How Government Prioritizes Problems. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Kelemen, R. Daniel (2017). ‘Europe’s Other Democratic Deficit: National Authoritarianism in Europe’s Democratic Union’, Government and Opposition, 52:2, 211–38.

- Kelemen, R. Daniel (2020). ‘The European Union’s Authoritarian Equilibrium’, Journal of European Public Policy, 27:3, 481–99.

- Kelemen, R. Daniel (2022). ‘Appeasement, Ad Infinitum’, Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law, 29:2, 177–81.

- Kelemen, R. Daniel, and Tommaso Pavone (2023). ‘Where Have the Guardians Gone? Law Enforcement and the Politics of Supranational Forbearance in the European Union’, World Politics, 75:4, 779–825.

- Kingdon, John W. (2014). Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. London: Pearson New International Edition.

- Kochenov, Dimitry (2019). ‘Elephants in the Room: The European Commission’s 2019 Communication on the Rule of Law’, Hague Journal on the Rule of Law, 11:2-3, 423–38.

- Lacy, Dean, and Emerson M. S. Niou (2004). ‘A Theory of Economic Sanctions and Issue Linkage: The Roles of Preferences, Information, and Threats’, The Journal of Politics, 66:1, 25–42.

- McKibben, Heather E. (2010). ‘Issue Characteristics, Issue Linkage, and States’ Choice of Bargaining Strategies in the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy, 17:5, 694–707.

- Moravcsik, Andrew (1993). ‘Preferences and Power in the European Community: A Liberal Intergovernmentalist Approach’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 31:4, 473–524.

- Papada, Evie, et al. (2023). ‘Democracy Report 2023 Defiance in the Face of Autocratization’, V-DEM.

- Pavone, Tomasso, and Øyvind Stiansen (2022). ‘The Shadow Effect of Courts: Judicial Review and the Politics of Preemptive Reform’, American Political Science Review, 116:1, 322–36.

- Pech, Laurent (2019). ‘From “Nuclear Option” to Damp Squib?’, Verfassungsblog, 13 November 2019, available at https://verfassungsblog.de/from-nuclear-option-to-damp-squib/.

- Pech, Laurent (2020). ‘Article 7 TEU: From “Nuclear Option” to “Sisyphean Procedure”?’, in Uladzislau Belavusau and Aleksandra Gliszczyńska Grabias (eds.), Constitutionalism under Stress: Essays in Honour of Wojciech Sadurski. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 157–74.

- Pech, Laurent (2022). ‘No More Excuses’, VerfBlog, 16 February 2022.

- Pech, Laurent, and Kim Lane Scheppele (2017). ‘Illiberalism within: Rule of Law Backsliding in the EU’, Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies, 19, 3–47.

- Platon, Sébastien (2021). ‘Bringing a Knife to a Gunfight: The European Parliament, the Rule of Law Conditionality, and the Action for Failure to Act’, VerfBlog, 11 June 2021.

- Priebus, Sébastien (2022). ‘Watering down the ‘Nuclear Option’? The Council and the Article 7 Dilemma’, Journal of European Integration, 44:7, 995–1010.

- Röben, Volker (2010). ‘The Enforcement Authority of International Institutions’, in Armin von Bogdandy, Rüdiger Wolfrum, Jochen von Bernstorff, Philipp Dann, and Matthias Goldmann (eds.), The Exercise of Public Authority by International Institutions. Berlin: Springer, 819–42.

- Scheppele, Kim Lane (2016). ‘Enforcing the Basic Principles of EU Law through Systemic Infringement Actions’, in Carlos Closa and Dimitry Kochenov (eds.), Reinforcing Rule of Law Oversight in the European Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 105–32.

- Scheppele, Kim Lane, Dimitry Kochenov, and Barbara Grabowska-Moroz (2020a). ‘EU Values Are Law, after All: Enforcing EU Values Through Systemic Infringement Actions by the European Commission and the Member States of the European Union’, Yearbook of European Law 38:3–121.

- Scheppele, Kim Lane, Pech Laurent, and Platon Sébastien (2020b). ‘Compromising the Rule of Law While Compromising on the Rule of Law’, VerfBlog, 13 December 2020.

- Schimmelfennig, Frank (2018). ‘European Integration (Theory) in Times of Crisis: A Comparison of the Euro and Schengen Crises’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:7, 969–89.

- Schlipphak, Bernd, and Oliver Treib (2017). ‘Playing the Blame Game on Brussels: The Domestic Political Effects of EU Interventions against Democratic Backsliding’, Journal of European Public Policy, 24:3, 352–65.

- Seawright, Jason, and David Collier (2010). ‘Glossary’, in Henry E. Brady and David Collier (eds.), Rethinking Social Inquiry: Diverse Tools, Shared Standards. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Uitz, Renáta (2019). ‘The Perils of Defending the Rule of Law through Dialogue’, European Constitutional Law Review, 15:1, 1–16.

- UNHCR (2022). ‘Ukraine Refugee Situation’, available at https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine/location?secret=unhcrrestricted.

- Vaagland, Karin (2021). ‘Crisis-Induced Leadership: Exploring the Role of the EU Commission in the EU–Jordan Compact’, Politics and Governance, 9:3, 52–62.