?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The extent to which political parties change their policy positions and the emphasis they give to different topics is crucial for the representativeness and responsiveness of contemporary political systems. This article aims to clarify the role of intraparty democracy in explaining the amount of such change. Previous research has shown that a stronger empowerment of members decreases programmatic change. This hypothesis is tested here more broadly, looking at both position shifts and emphasis change, adopting a more comprehensive definition of intraparty democracy and unpacking the Left-Right scale into an economic and cultural subdimension. It is further argued that the effect of intraparty democracy is moderated by the relative salience of the economic vs. cultural subdimensions of political competition. The empirical analysis of 47 parties in 10 countries between 1995 and 2019 confirms that more internally democratic parties change less, while evidence concerning the moderating effect of relative salience is more mixed.

The extent to which political parties change is of great importance for the functioning of democracy. From a normative point of view, it is desirable that party systems express a wide range of positions, to voice the diverse preferences in the electorate. However, parties should also be flexible in the positions they take, for example in order to reflect changes in context, conditions or voter preferences. Similarly, parties should exhibit some level of change in the topics they emphasise, as issues rise or fall in their urgency or salience, so that the most pressing issues are put on the political agenda. On the other hand, change per se is not necessarily beneficial for parties, as policy shifts that are too frequent might decrease parties’ credibility (Downs Citation1957). Accordingly, there might be different incentives to promote or resist change. In this article, I examine the extent to which parties change their positions and issue emphasis and suggest intraparty democracy as a main explanation thereof.

Party organisation affects how much political parties change their policies (Koedam Citation2022b; Schumacher and Giger Citation2018). Assuming that party activists are more policy-motivated (Kitschelt Citation1988) and therefore less inclined towards ideological compromise, larger organisational constraints on the leadership should decrease programmatic change (Pedersen Citation2012a; Sánchez-Cuenca Citation2004). Hence, I expect that parties with more inclusive decision-making procedures are less flexible, due to the increased number of potential veto points and the greater influence of activists. Moreover, I argue that the salience of an issue moderates this effect, with inclusive parties even less likely to change on their core issues. The article will thus explore how intraparty democracy and party salience affect the programmatic changes of political parties.Footnote1

This study is not the first to examine the link between party structure and change, but substantially expands on existing works. Thus, Meyer (Citation2013) only looks at policy positions based on manifesto data and assesses the effect of single components of intraparty democracy. Schumacher and Giger (Citation2018) examine manifestos and expert surveys, but adopt a more limited timeframe (only until 2010) as well as a different dependent variable (counting the number of issues on which parties have changed, which disregards the magnitude of those changes) and measurement of the independent variable (they assess leadership domination through expert surveys only). Both these studies, moreover, ignore the potential role of party salience in moderating the effect of intraparty democracy. Wagner and Meyer (Citation2014) consider this factor, but they exclusively focus on changes in parties’ issue emphasis (based on their manifestos) and measure organisational goals rather than intraparty democracy stricto sensu. Moreover, most contributions measure the balance of power between members and activists, often poorly distinguished, and the leadership, rather than intraparty procedures. I address these shortcomings by (i) observing changes in both position and emphasis, (ii) relying on alternative measurement sources and (iii) adopting a multidimensional definition of intraparty democracy.

By bridging the literatures on party behaviour, issue competition, party change and party organisation, this article makes three main contributions. First, on the theoretical level, I refine existing analyses with a more thorough test of how intraparty dynamics affects the external behaviour of political actors. Moreover, I adopt a thicker definition of intraparty democracy, suggesting a new, more complex index encompassing several dimensions. In fact, the formal openness of party structures might further entrench the power of the leadership. One example is the (quasi-)plebiscitary decision-making process of the Five Star Movement in Italy, allowing only registered members to digitally ratify top-down proposals (Gerbaudo Citation2021). For this reason, other authors (most prominently Wolkenstein Citation2018a) have highlighted the normative desirability of deliberation beyond merely aggregative procedures. Accordingly, I propose a more comprehensive index relying on the pillars identified by Ignazi (Citation2020: 14) as the ‘knights of intra-party democracy’. This conceptualisation incorporates multiple dimensions but has not, so far, been directly operationalised to gauge intraparty democracy.

The second contribution of the article concerns the type of change studied: I observe changes in both position and emphasis – unlike Meyer (Citation2013), who only looks at positions, or Wagner and Meyer (Citation2014), who only focus on emphasis. Moreover, I examine changes not only in the overall Left-Right orientation of political parties, but also those on the economic and cultural subdimensions of political competition. The third contribution consists of relying on multiple data sources: comparing data collected from official party documents (manifestos and statutes) and expert surveys provides the best and most comprehensive test possible for my hypotheses. Finally, I assume a dynamic perspective and expand the timeframe of previous studies.

The topic is also empirically relevant. On the one hand, the extent to which political parties change their agendas is crucial to improve the responsiveness and representativeness of the political system – either through the politicisation of new issues (Meguid Citation2008; Plescia et al. Citation2019) or shifts in party positions, to accommodate the evolving demands of the electorate. On the other hand, the ideological coherence of political parties is key to maintain credibility and guarantee the fulfilment of electoral pledges. This article contributes to this debate by positing that the extent to which political parties change (or not) can help improve the party system capacity to represent voters, and therefore the functioning and quality of contemporary democracy. Indeed, my research indicates party organisation as a pivotal, although often neglected, driver of party change. Moreover, it should be examined jointly with salience, as issue importance moderates the effect of party organisation. I also stress the need to rely on alternative data sources to gain the broadest empirical understanding possible and overcome limitations in measurement strategies.

Explaining party programmatic change

Programmatic change is a key component of party change (Harmel and Janda Citation1994). In this article, I conceive of it as twofold: position change and emphasis change.

Parties might want to shift position for different reasons. The spatial model of competition suggests that vote-seeking parties appeal to the median voter (Downs Citation1957). Ideological moderation might help parties to present themselves as viable coalition partners (cf. Pereira Citation2020; Tromborg Citation2015) and increase perceived competence (Johns and Kölln Citation2020). But, for instance, parties might want to take less centrist positions (Spoon Citation2009; Wagner Citation2012) or avoid change altogether (Adams and Somer-Topcu Citation2009; Ezrow et al. Citation2011; Joon Han Citation2017) to distinguish themselves from other competitors. Indeed, we know that niche parties lose votes when they moderate (Adams et al. Citation2006; Ezrow Citation2008; Maeda Citation2016; but see Tromborg Citation2015) and that conversely, radicalisation might pay off – as exemplified by the True Finns in the wake of the 2011 election, leading the party to its best electoral result (Jungar Citation2016). Parties might therefore have different incentives to change (or not) position in any direction, as following the median voter is no panacea for success.

Furthermore, parties can adjust the emphasis they give to different issues: they should prioritise issues they own (Budge and Farlie Citation1983; Dolezal et al. Citation2014; Green-Pedersen Citation2007; Green-Pedersen and Mortensen Citation2010; Wagner Citation2012) and those perceived as important in the public debate (Spoon and Klüver Citation2019; Wagner and Meyer Citation2014). But while a narrow issue appeal is beneficial for new parties (Zons Citation2016), over time they might want to expand their agenda: for instance, under certain conditions, challengers can increase their vote share by also competing on the economic dimension (Bergman and Flatt Citation2020; Spoon and Williams Citation2021). This suggests that parties may choose which issues are most convenient to emphasise, instead of relying exclusively on issue ownership. Moreover, as argued by Meyer and Wagner (Citation2019: 758), pursuing ‘emphasis-based’ policy change, which is usually less noticeable and therefore less costly, might be easier.

Party position and/or emphasis change might be prompted by external factors, such as rival parties’ behaviour (Adams Citation2012; Adams and Somer-Topcu Citation2009) or opinion shifts of voters and supporters (Ezrow et al. Citation2011; Laver Citation2005). This article, however, analyses internal pressures, arguing that the extent to which parties change depends on (i) how they are organised and (ii) which issues are most salient for them.

Party organisation

Programmatic change can be affected by the level of intraparty democracy, which I define as the openness of party structures to input from members or activists in decision-making processes.Footnote2

Indeed, it has been suggested (Pedersen Citation2012b; Schumacher and Giger Citation2018; Strøm Citation1990) that party organisation influences party goals (Müller and Strøm Citation1999) and that whether the party prioritises policy outcomes, office positions or vote maximisation drives party choices in terms of position and emphasis change (Harmel and Janda Citation1994). In brief, the most powerful organisational component of the party would shape its strategy. If leaders are more prone to sacrificing ideological purity to gain votes or office (Kitschelt Citation1988; Panebianco Citation1988; Pedersen Citation2012a),Footnote3 while activists privilege policy coherence, higher activist power should decrease the likelihood that a party is office-seeking or vote-maximising (Ezrow et al. Citation2011; Pedersen Citation2012b). Moreover, inclusive decisional procedures increase potential veto points (Tsebelis Citation1990) and overall ideological rigidity (Sánchez-Cuenca Citation2004), therefore making party change harder to achieve practically. Accordingly, parties that are highly internally democratic should be less likely to change. I therefore expect that (H1) more inclusive parties change less than parties with a strongly centralised leadership.

Previous scholarship found a link between party organisation and programmatic change. Schumacher and Giger (Citation2018) show that leadership-dominated parties change more than activist-dominated ones, but the effect is only significant for position and not for emphasis shifts.Footnote4 However, they focus on the number of changes, therefore disregarding their magnitude. Meyer (Citation2013) has also investigated the effect of different dimensions of party organisation (mass organisational strength, financial resources, candidate selection processes), but only for position shifts. I suggest here a further, more thorough test of this important hypothesis using (i) the absolute amount of position and emphasis changes as dependent variables; (ii) a detailed measurement approach relying on alternative sources and (iii) a multidimensional definition of intraparty democracy.

Dimensional salience

The salience of an issue for the party and in the political system may also explain programmatic change. Some parties might in fact want to keep a limited issue appeal, on topics they own, while others might not be able to avoid addressing issues that are deemed important by voters. As party competition in Western Europe is increasingly multidimensional (De Sio and Weber Citation2014), we can expect parties to tackle issues beyond those that they own, although with different costs and benefits.

The literature addressing emphasis change usually focuses on individual issues – mostly immigration, environment and welfare – whereas research on position change mainly looks at the Left-Right spectrum. The overall Left-Right orientation is described as a super-issue (Inglehart and Klingemann Citation1976) with a ‘multidimensional character’ (Freire Citation2015: 45), subsuming an economic and a cultural subdimension (Kriesi et al. Citation2008; Meyer and Wagner Citation2020; Sani and Sartori Citation1983). We know that the salience of these subdimensions shapes the perceived position of a party (Meyer and Wagner Citation2020) and that policy shifts are rewarded differently depending on which dimension they concern (Tavits Citation2007). Moreover, it is worth analysing them individually because the Left-Right scale may conceal differences in the distribution of voters’, members’ and leaders’ preferences across subdimensions (as shown empirically by Wager et al. Citation2022). For the scope of this article, I thus unpack the Left-Right position in the two main dimensions of political competition: economy (including preferences on welfare and state/market relations) and culture (assimilated to the GAL/TAN scale, thus including nationalism and environmentalism).

Previous research has shown that party change is indeed affected by the relative salience of the economic and cultural subdimensions of political competition (Koedam Citation2022a; Meyer and Wagner Citation2020). In particular, parties tend to maintain ideological stability on the dimension that is most salient for them (primary dimension), changing more on the secondary one (Koedam Citation2022a). In fact, as shifting positions on topics that are more strongly associated with the party might risk alienating some supporters, we can expect parties to change less on their primary dimension. This effect should be smaller for emphasis changes, which are less easy to detect and do not necessarily come at the expense of stable policy positions on the core dimension (Meyer and Wagner Citation2019). Moreover, this effect could be moderated by the organisation of the party: a particularly inclusive party should be even less likely to change on its primary dimension, since it is perceived as the most important by members, who value policy coherence. Accordingly, I expect that (H2) the more inclusive a party, the less it changes on its primary dimension of competition.

Summing up, I analyse intraparty democracy and dimensional salience as independent variables, taking programmatic change (in terms of both position and emphasis) as dependent variable. I thus study the effect of more inclusive decision-making procedures on parties’ ideological flexibility, showing that their behaviour might depend on their organisation and on the relative salience of political subdimensions.

Operationalisation and methods

Programmatic change

Following the twofold operationalisation of the dependent variable, party programmatic change, I will measure positions with expert survey data and emphasis with manifesto data. I argue that expert surveys are the preferable source to measure party positions: assessments are not limited to party manifestos (which might not be the only, nor the most relevant, platform through which politicians communicate their programmes) and embrace a wider, although potentially vague, time horizon (Budge Citation2000). However, expert surveys also have disadvantages when it comes to measuring party positions. In particular, their tendency to overestimate position stability biases my research towards null findings. While I focus on the results using expert survey positions, in Online Appendix V I also perform sensitivity analyses using measurements of party positions derived from manifestos.

The Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES, Jolly et al. Citation2022) data include variables codifying party position on specific dimensions (usually ranging between 0 and 10). Besides the overall Left-Right position (which has no corresponding salience measure), for this article I will use positions on the economic and cultural (GAL/TAN) subdimensions. From each relevant variable, I calculate the absolute shift between consecutive waves of the survey.

However, expert survey data are not well-suited to measure issue emphasis, since they fail to capture the zero-sum effect of allocating salience to different topics. They thus overlook not only the relative salience of issues, but also the fact that devoting more space to a topic necessarily shrinks the space of others. Conversely, manifesto data directly quantify issue emphasis and can capture more change than an expert survey, limiting the risk of having too little variation on the dependent variable. This could be especially problematic considering that programmatic changes tend to be incremental. On the other hand, formal programmes as captured by manifestos might not necessarily be substantiated by the behaviour of the party: beside electoral pledges, the party agenda could still change, for instance if new issues come up during the campaign.

For emphasis and salience, I thus take my measurements from the Manifesto Research on Political Representation (CMP/MARPOR, Lehmann et al. Citation2022). Following Bakker and Hobolt (Citation2013), I calculate the emphasis on the economic and liberal-authoritarian (resembling the GAL/TAN scale) dimensions, using the logit scaling method developed by Lowe et al. (Citation2011). For the dependent variable of changes in emphasis between elections, I calculate the absolute change in emphasis on economic and cultural topics, respectively. To measure the dimensional salience for individual parties, I follow Koedam (Citation2022a) in using a continuous ratio between the emphasis given to these dimensions. I therefore obtain a variable ranging between −1 (if the party only emphasises cultural issues) and 1 (if only economic issues are mentioned). Positive values for this variable indicate that the economic dimension is the primary one for the party, while negative values indicate that the cultural dimension is primary.

Intraparty democracy

The concept of party organisation entails different dimensions. Overall, it is used to describe how the party is structured (on a formal level), and therefore functions (in practice). As already discussed, the internal structure of parties – in particular, the inclusiveness of decision-making procedures – also influences their strategic behaviour. Indeed, I expect that when rank-and-file members are more powerful, a party is less likely to initiate major policy shifts. The opposite should be true for strongly leadership-dominated parties, in which the lower complexity of centralised decisions allows for more flexibility in the programmatic stances.

We know that the internal structure of political parties is changing (Pizzimenti et al. Citation2022). To increase their democratic legitimacy, many parties have introduced primaries for leadership or candidate selection, and these are sometimes open to non-members, too (Sandri and Seddone Citation2016). The Social Democratic Party of Germany has even consulted its members concerning potential coalition agreements with the Christian Democrats in 2013 and 2018 (Wolkenstein Citation2018b). However, such formal entitlements can disguise a plebiscitarian tendency, further strengthening the leadership’s position through direct validation from below – at the expense of intermediate levels, for instance representing local interests. For this reason, as suggested by Ignazi (Citation2020), it is more appropriate to consider a party as truly internally democratic if it presents: (1) the formal involvement of members through ballots, (2) a degree of pluralism (in terms of internal currents and factions),Footnote5 (3) deliberative processes engaging multiple actors in policy elaboration, and (4) diffusion of power in collective organs at different levels. In my measurement of intraparty democracy, I shall therefore try to retrace each of these ‘four knights of intra-party democracy’ (Ignazi Citation2020: 14). This, I argue, contributes to a thicker and more comprehensive conceptualisation of intraparty democracy.

The participation of different components of a party (especially members and activists) is, however, quite difficult to assess. Some have relied on expert surveys (especially those by Jolly et al. Citation2022; Laver and Hunt Citation1992; Rohrschneider and Whitefield Citation2012), with specific items assessing how influential party activists (or members, often without a clear distinction between the two categories) are compared to the leadership (Bischof and Wagner Citation2020; Koedam Citation2022b; Meyer and Wagner Citation2019; Citation2020; Schumacher et al. Citation2013; Schumacher and Giger Citation2017; Citation2018). Others have retraced this information from primary or secondary sources (statutes and previous literature; Poguntke et al. Citation2016; Webb et al. Citation2022). Both types of data collection present strengths and flaws, which will not be discussed in detail here. For my analysis, I will use both the Political Party Database (PPDB) Project by Poguntke et al. (Citation2016, updated by Scarrow et al. Citation2022) and the Democratic Accountability and Linkages Project (DALP, Kitschelt Citation2013). The former, being based on official party documents, can track changes over time (if statutes are amended) but is subject to a potential mismatch between formal provisions and their actual implementation. The latter, conversely, is based on an expert survey, and therefore has the advantage of providing a broader picture than official documents. The two datasets also cover a rather similar timeframeFootnote6 and capture multiple dimensions of intraparty democracy.

Both sources measure all the relevant aspects for my operationalisation of intraparty democracy: (1) the consultation of members for candidate/leadership selection and policy ballots, (2) the explicit recognition of factions, (3) the extent to which party structures are involved in policy elaboration and (4) the participation of different levels to decision making. For each of these items I assign a score ranging between 0 (for the least inclusive) and 1 (for the most inclusive option). I then calculate the mean of the four components to obtain my final indices of intraparty democracy: one from the PPDB, statute-based, the other from the DALP, an expert survey. More details on the items used are provided in Table A1 in Online Appendix I.Footnote7 Online Appendix VII replicates the main analysis taking each individual component, instead of the aggregated index, as main predictor. Online Appendix IV also reports the results of models using the measure of inclusiveness from the expert survey by Rohrschneider and Whitefield (Citation2012).

Control variables

Moreover, I control for potential confounders, i.e. elements that could influence both party organisation and programmatic shifts. Firstly, past government status. Governmental constraints can affect the extent to which parties are free to change position. Also, becoming a government party might require some organisational adaptation. Previous research has shown that parties in government can afford not to rely on infrastructure because they can use ‘policies, appointments and patronage as rewards instead’ (Bolleyer Citation2009: 575). Moreover, Kaltenegger et al. (Citation2021) show that the loss of executive power can make elites more responsive to activists. I therefore include in my analysis a dummy variable indicating government participation in the previous term, taken from the ParlGov database (Döring et al. Citation2022).

Second, I control for the size of the party. Since it is more difficult to ensure the active participation of vast masses, smaller parties could more easily adopt deliberative procedures among members. Research has indeed shown that changes in membership size lead to organisational reform (Kölln Citation2015; Rohlfing Citation2015). On the other hand, membership size could also influence the amount of programmatic change: parties with a smaller base could identify members’ preferences more clearly and need less adjustments to maintain policy coherence. I take membership figures from the MAPP (Members and Activists of Political Parties) dataset project (van Haute and Paulis Citation2016).Footnote8 However, it is also important to account for electoral defeat. We know that electoral shocks can prompt programmatic change (Budge et al. Citation2010; Koedam Citation2022b; Somer-Topcu Citation2009), as a loss of support might encourage parties to adjust positions or emphasise different issues, to become more appealing (Kaltenegger et al. Citation2021). I therefore also control for vote loss, measured as the difference in vote share in the last two elections.

Lastly, I control for ideological extremism. Indeed, a party’s ideological background might affect the way it organises internally, while constraining further position shifts, by making some options undesirable or unviable. I measure ideological extremism as a dummy variable indicating whether the position of the party is more than one standard deviation above or below the average party position of that country in that election. Several contributions (Adams et al. Citation2006; Adams and Somer-Topcu Citation2009; Ezrow et al. Citation2011) have hypothesised some (particularly non-mainstream or niche) parties to be more responsive to position shifts among their supporters rather than in the median voter. Accordingly, I include both these elements pertaining to public opinion as controls for further robustness analyses (Online Appendix VI), retrieving mean voter and party voter position shifts from the European Social Survey (ESS).

To sum up, I measure intraparty democracy (the independent variable) relying on two indices from the PPDB and DALP datasets, whereas party change (the dependent variable) is measured as position shifts from the CHES and emphasis change from CMP/MARPOR, which I also use to calculate the relative dimensional salience for each party. Some control variables (ideological extremism, vote share and vote loss) are measured through the CMP/MARPOR, while government participation comes from the ParlGov database, and membership figures from the MAPP project. Key descriptive statistics for all variables, as well as graphs showing their distributions, are reported in Online Appendix II. In further Online Appendices, I also estimate alternative models using a different measure of inclusiveness (IV), capturing positional changes through manifesto data (V) and incorporating the mean voter position (VI). summarises my measurement choices.

Table 1. Summary of the variables of interest, their operationalisation and measurement. Variables in square brackets are used for robustness checks in the Online Appendices.

Methods of estimation

In order to perform the empirical test, I take party/election as the unit of analysis.Footnote9 The resulting dataset includes 47 parties from 10 West European countries (Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Spain, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands and Portugal), for a total of 733 observations. The timespan ranges between 1995 and 2019.

Due to the multilevel nature of the data, with parties nested in countries as well as time effects, I rely on mixed-effects (hierarchical) linear models. In fact, most of the variation in my data is between rather than within observations, meaning that parties differ more between each other than they change over time. This is not unexpected, since party change is rather incremental and my measures of intraparty democracy only account for few time-points. I estimate multilevel models with random effects at the level of party and country and robust standard errors.Footnote10 In order to exclude endogeneity, I use a lagged version of government participation, vote share and vote loss. However, it might be possible that the size of the party is influenced by the amount of policy change on the one hand and by the level of intraparty democracy on the other. I have therefore assessed the robustness of my results against the risk of post-treatment bias, by lagging party size, too: results do not change (see also Online Appendix IV for models measuring party size as lagged vote share).

As stated above, the dependent variable is programmatic change, measured as position and emphasis on economic and cultural dimensions (as well as the Left-Right scale, only for position). In particular, I look at absolute changes in position and emphasis between elections, with measurements taken respectively from the CHES and the CMP/MARPOR. The independent variable is intraparty democracy, measured by the indices I propose (one from the DALP dataset and one from the PPDB). The other main predictor is dimensional salience, intended as the ratio between the emphasis given to the economic and cultural dimension. Additionally, I include as controls the membership size of the party, its ideological extremism, its participation in government in the last legislature and its vote loss since previous elections. I also include interaction terms between intraparty democracy and party salience, that I expect to moderate the effect of IPD on programmatic change. The general structure for a series of alternative models relying on the different measurements of the dependent and independent variables – as discussed above – therefore looks as follows:

below summarises my hypotheses and the expected signs of the relevant coefficients.

Table 2. Summary of hypotheses and expected coefficient signs.

Results

Position shifts

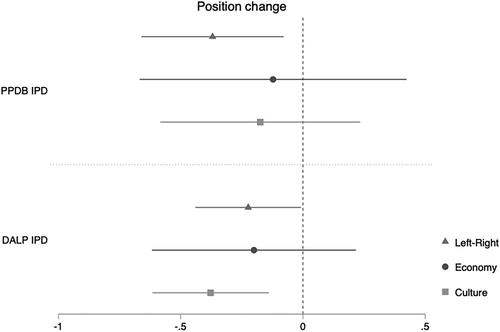

reports the results of models estimating the effect of intraparty democracy (IPD) on the overall position of the party on the Left-Right scale. The models take the measurements of intraparty democracy from the PPDB (model 1) and the DALP datasets (model 2). As can be seen, the alternative indices lead to rather similar results. As expected, the effect of intraparty democracy is negative and significant, indicating that more inclusive parties tend to change their Left-Right position less. This supports H1: more inclusive parties change less overall.

Table 3. Models estimating position shifts on the Left-Right scale.

Let us now proceed to the examination of each subdimension of political competition. reports the coefficients for the models estimating the effect of intraparty democracy (with indices taken from PPDB and DALP) on position shifts along the economic (3–4) and cultural (5–6) dimension. Although largely not significant, the coefficients are consistent. Looking at the economic dimension, intraparty democracy is again negatively correlated with position change, as expected by H1. The effect of salience ratio – indicating whether a party primarily competes on the economic compared to the cultural dimension – is positive, suggesting that, against expectations, parties change their position on the economy more if they primarily emphasise the economic dimension.

Table 4. Models estimating position shifts on the economic and cultural dimension.

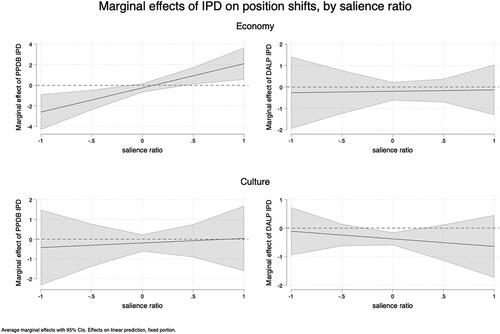

The interaction terms between intraparty democracy and salience ratio are instead positive, although only significant for the model with PPDB data. This would suggest that the effect of intraparty democracy becomes less negative as the party-level salience of the economic dimension increases. Looking at the average marginal effects plotted in (especially the upper-left graph), we therefore see that the results contradict H2. In fact, it seems that the effect of intraparty democracy on position shifts is negative if the party mainly competes on the cultural dimension (i.e. the value of salience ratio is below 0). In other words, parties change less on their secondary dimension if they are more inclusive.

Figure 1. Marginal effects of intraparty democracy by party salience (DV: position shift on economy and culture).

When taking as dependent variable the cultural position shifts (models 5–6), the results seem again consistent across different model specifications. Coefficients for intraparty democracy (IPD) are negative and significant with the DALP predictor, thus supporting H1. The effect size seems to be slightly larger, suggesting that intraparty democracy affects changes on the cultural dimension more than on the economic one. The effect of salience ratio is negative although not significant, suggesting that (against expectations) parties that mainly emphasise the economic dimension change less on the cultural dimension. The interaction terms between intraparty democracy and party-level salience are not significant and differ in sign, bringing mixed evidence for H2. Looking at the marginal effect plots in (lower-right corner), it seems that the effect of intraparty democracy on cultural position change is slightly more negative when the party’s primary dimension is the economic one.

Emphasis change

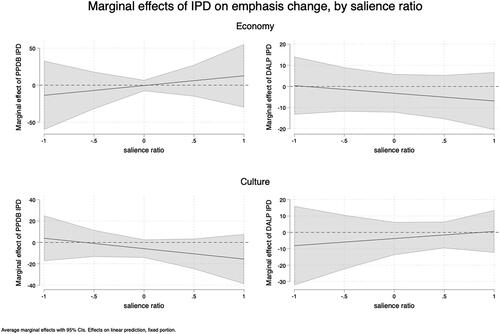

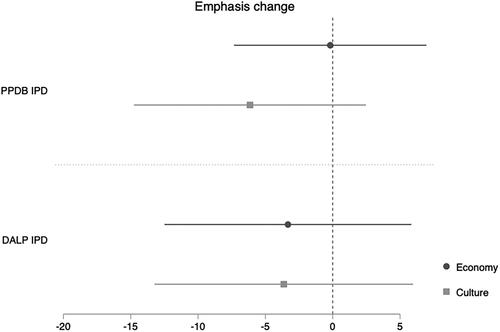

The last set of models estimates changes in the emphasis that parties give to the economic and cultural dimension. Model results are reported in , while interaction effects are shown in . As concerns models 7 and 8, estimating emphasis change on the economic dimension, we find some evidence for H1. In fact, coefficients for intraparty democracy (albeit not significant) are always negative, suggesting that higher intraparty democracy is indeed associated with lower changes in emphasis. The coefficients for salience ratio are positive and significant, meaning that parties change their emphasis on the economic dimension more if that dimension is the most salient for them. However, the picture is more complex when considering salience and its interactions. The model with PPDB data predicts a positive and significant interaction coefficient, which would suggest that more inclusive parties change their emphasis on the economic dimension less if it is their secondary dimension, against H2 (see plot on the upper-left corner of ). The model with DALP data has instead a negative and not significant interaction term.

Figure 2. Marginal effects of intraparty democracy by party salience (DV: emphasis change on economy and culture).

Table 5. Models estimating emphasis change on the economic and cultural dimension.

Models 9 and 10, predicting emphasis change on the cultural dimension, lead to similar conclusions. Both intraparty democracy indices have a negative effect on emphasis change, as per H1. Coefficients for party salience, although not significant, suggest that against expectations parties change less on the cultural dimension, the more they prioritise the economic one. Evidence for H2 is again mixed, due to the different sign of interaction effects. The marginal effect plots in show this contradiction: the model with PPDB predictors (lower-left corner) shows that intraparty democracy has a negative effect on emphasis change on the cultural dimension for parties that mainly emphasise the economic dimension. The model with DALP data, however, would suggest the opposite.

In Online Appendices III to VI, I report additional models that (1) use membership figures as a measure of party size instead of vote share, (2) take another expert survey measure for inclusiveness, (3) take measurements of position shifts from manifesto data instead of expert surveys, and (4) add mean voter and mean party voter positions as controls. The results of these models are extremely similar to those using my indices, so the findings are robust to different model specifications, with alternative measurements of both dependent and independent variables.

Two case studies: the German FDP and the Danish Conservatives

In order to further elucidate the patterns identified through the large-N study, I now focus on two typical cases (Seawright and Gerring Citation2008) of important changes in party organisation, to retrace the programmatic shifts that followed. This more qualitative evidence may further support the results of the quantitative estimation, in a nested design (Lieberman Citation2005). I therefore estimate changes in the IPD measure from PPDB (the one that indeed varies over time, see Table A2 in Online Appendix II) and focus on parties that have contested more than three consecutive elections and for which we have at least three different values of IPD over time. The largest increase in the intraparty democracy index (around 0.3 points, corresponding to almost three times the standard deviation) was experienced by the Free Democratic Party (FDP) in Germany,Footnote11 whereas the Conservative People’s Party in Denmark experienced the strongest negative change in intraparty democracy, with a decrease of nearly 0.3 points.

The trend towards a higher intraparty democracy for the FDP is mainly marked by the opening of candidate selection to members, especially in the Länder. In fact, although the selection of the leader remains prerogative of the national level, the PPDB identifies a change in the FDP rules concerning candidate selection, in which members as well as local and regional party branches have become formally involved since 2017. In my measurement, this translates in an increase in inclusiveness (from 0.2 to 0.7) but also in diffusion (from 0.3 to 0.5) between 2013 and 2017. Indeed, we can argue that this evolution towards a higher intraparty democracy culminated with the primary election organised in Bavaria to select the regional candidate for the 2018 election (Küppers Citation2021).

How was this organisational change reflected in the programmatic choices of the party? shows that, while the IPD index increases, the amount of change also takes on lower values – if we exclude the exceptional emphasis change in 2017, probably connected to the fact that the party had lost parliamentary representation in the previous term. While on the economic dimension we see more stability both in position and emphasis, on the Left-Right scale (that, however, presents rather low values across time) and on the cultural dimension results are more nuanced. The change in cultural positions does follow the general downwards trend apart from 2013, when that was the primary dimension for the FDP (salience ratio < 0). This is therefore also in line with our finding that more inclusive parties tend to change more on their main dimension. For cultural emphasis change, data report instead increasing values over time – again with a peak in 2017, which contradicts our expectations.

Table 6. Evolution of intraparty democracy, salience and programmatic change.

The other case study addressed in this section is the Conservative People’s Party in Denmark. Starting with relatively high levels of IPD (one standard deviation above the dataset mean), the party experienced a sharp decrease in 2015, which was followed by a new rise in 2017, although not up to the previous levels. This was mainly driven by the lower power of members in candidate selection (decreasing inclusiveness) as well as more centralised procedures for leadership selection, previously involving local as well as national party bodies, and manifesto drafting (decreasing diffusion and deliberation, respectively). The partial increase in 2017 is instead due to a higher involvement of local and regional levels in candidate selection. My hypotheses would predict bigger changes in position and emphasis in 2015 compared to 2011 – which is the case for the Left-Right scale as well as for cultural position and emphasis, less so on the economic dimension. Again, this could be connected to the interaction with salience: the party changes less on the economy when it is its primary dimension of competition, in 2015. Moreover, since the Conservatives were part of the governing coalition between 2016 and 2019, this could have prevented major shifts on the economic dimension in 2019.

These two cases therefore illustrate that the evidence from the large-N analysis is largely confirmed by a more in-depth examination, while maintaining many of the nuances that also appear in the models.

Conclusion

This article advances our understanding of how intraparty dynamics can influence the policy change of political parties. It tests theoretical implications more broadly compared to previous contributions: not only considering both changes in position and emphasis, but also focusing on different subdimensions of political competition, while adopting a multidimensional definition of intraparty democracy that goes beyond merely aggregative procedures. Statistical analyses bring empirical support for the core expectation (H1) that more internally democratic parties change less. As can be seen in and , summarising the effect of intraparty democracy on position and emphasis change, respectively, intraparty democracy is always negatively correlated with party change. This suggests that more inclusive parties change their Left-Right orientation and their position and emphasis on economic and cultural subdimensions less, compared to less internally democratic parties, although effects are only statistically significant in some models. This confirms findings from previous studies, but validates their conclusions further, using a more complex measure of intraparty democracy and alternative data sources. In fact, results are consistent across different model specifications, relying either on official party documents (the CMP/MARPOR for the dependent variables and the PPDB for the independent variable) or on expert surveys (CHES for the dependent variables and DALP for the independent variable). This suggests that formal changes, captured by official documents, are also mirrored in the actions of political parties, as they can be captured by experts.

Figure 3. Plot of the coefficients for models estimating absolute position shifts on the Left-Right scale as well as on the economic and cultural dimensions.

Figure 4. Plot of the coefficients for models estimating absolute emphasis changes on the economic and cultural dimensions.

Empirical evidence for the second expectation is instead more mixed. The assessment of how party salience moderates the effect of intraparty democracy largely contradicts my theoretical assumptions (H2). Indeed, it seems that more inclusive parties change position more on the dimension that they primarily emphasise. This might be explained by the fact that a party that is more inclusive probably enjoys a stronger legitimation from its base in decision making. Indeed, programmatic changes on their core dimension might be perceived as less risky if they are endorsed by different party components. It is also more likely that members are especially involved on topics that are the most salient to the party rather than on peripheral ones. Accordingly, internally democratic parties might feel more confident in changing position on their primary dimension of competition. Although further research is needed to elucidate this point, this study provides a first insight into the mechanisms connecting the increasingly multidimensional party competition with the relative salience of these dimensions.

This analysis has shed light on whether and when parties change and what explains possible differences. As a further theoretical implication, results encourage to downsize the importance of the median voter model of political competition as well as May’s (Citation1973) law of curvilinear disparity: researchers should not assume that the preferences of simple members are close to the median voter position, nor that party activists hold more extreme positions compared to the leader. Moreover, we should acknowledge that these assumptions may hold to a different extent across political subdimensions, as previous research has shown (Van Holsteyn et al. Citation2017; Wager et al. Citation2022). In addition to the already mentioned theoretical and methodological contributions, this article is also empirically relevant. In fact, the extent to which parties change their policy positions and emphasis influences the capacity of the political system to adequately represent citizens’ preferences. By examining intraparty democracy and issue salience as key constraints for policy shifts, I highlight a trade-off between change and stability on which the quality of contemporary democracies depends.

As an avenue for future research, it could also be useful to account for the direction of changes rather than simply looking at the absolute amount. This would allow to test whether political parties respond to evolving preferences in the electorate, which falls outside the scope of this study. Moreover, I have focused here on intraparty democracy, but further dimensions of intraparty power might be equally worth addressing: cohesiveness, distribution of power, support for the leader and the party are some of them. Overall, this article contributes to our understanding of whether changes in party position and emphasis are encouraged by external factors (such as government participation or vote loss) and/or internal ones (party issue salience, intraparty democracy and ideological extremism). By providing alternative specifications of the models, relying on a thicker conceptualisation of intraparty democracy and comparing different measurement sources, this study offers an especially thorough test of the connection between party organisation and party change.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.1 MB)Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. Furthermore, I am grateful to my supervisors Markus Wagner and Carolina Plescia, to Ann-Kristin Kölln, to participants of the 2021 SISP conference and all my colleagues at the Department of Government, for their feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sofia Marini

Sofia Marini is a PhD candidate and pre-doctoral researcher at the Department of Government, University of Vienna. Her main research interests lie in the field of comparative politics and include party organisation, party competition and party change, as well as national and European political parties and party systems.

Notes

1 Note, however, that it is not the aim of this study to address party responsiveness, but simply party change.

2 Although party organisation encompasses several dimensions, from territorial articulation to membership or resource distribution (Poguntke et al. Citation2016), I deem the internal distribution of power as the most theoretically relevant aspect for understanding programmatic change.

3 With, of course, important limitations: a party leader inducing changes that infringe on the core ideology of the party (Panebianco Citation1988) would likely face strong resistance from members and activists.

4 This is in line with other studies (Meyer and Wagner Citation2019) that find that activist-dominated parties change their issue emphasis more than positions.

5 Although I am aware that highly democratic parties might present quite homogeneous internal preferences, I prefer to still include pluralism within my indices. Indeed, although it is not a necessary requirement, I argue that the recognition of the possibility that different factions (co)exist inside the party is a possible sign of intraparty democracy. Moreover, I deem it relevant to account for pluralism because the presence of factions can affect the leadership’s leeway in promoting programmatic changes.

6 The PPDB has its earliest observation from 2002 and the latest in 2019, but excluding these two observations the timespan is 2005–2018. I refer to the combination of the first and second round, the former with data up to 2015, the latter adding four more years. The DALP includes expert survey data collected between 2008 and 2009, therefore well aligned with the time span of the PPDB.

7 The authors of the PPDB themselves suggest a very detailed index (AIPD, assembly-based intraparty democracy), which captures the inclusiveness of intraparty decision making, including drafting the manifesto, personnel selection, and the structural distribution of powers. However, this measurement is quite cumbersome and overlooks the involvement of members, which are only considered in the complementary PIPD (plebiscitary intraparty democracy) index.

8 Another option is to rely on party vote share as a proxy for party size. In Online Appendix IV I estimate additional models with this alternative measurement of party size.

9 Since the expert survey waves did not perfectly overlap with the election years, I use the closest wave to the national elections. The IPD indices that were only available for one point in time were extended to all time points. This is the only procedure that would allow me to compare the alternative measurements. Also, we can expect party organisation to change incrementally, with slow and small adjustments, especially in the time frame covered in the analysis.

10 Running fixed-effect models did not seem to be the most appropriate strategy since it would not be able to capture the effect of time-invariant predictors, as is the case for the measurements relying on expert surveys which were conducted only once – specifically, DALP and Rohrschneider and Whitefield. Also, the Hausman test shows no significant support in favour of a fixed-effect model. On the other hand, this does not necessarily speak in favour of using random-effect models: the test does not exclude that there is correlation between the covariates and the unit effects, therefore random-effect specifications are still likely subject to bias (Clark and Linzer Citation2015). Online Appendix VIII reports the results of fixed-effect models estimated using the PPDB index of IPD.

11 The Italian Democratic Party and the German Green Party also experienced increases of 0.4 and 0.3 points in the IPD index, respectively. However, since the initial value of 0 is due to a high number of missing observations and the consequent conservative estimation of IPD, I prefer not to focus on these parties in this paragraph. Conversely, the Red-Green Alliance in Denmark shows the strongest decrease (−0.3), but was excluded as it only had two distinct IPD scores.

References

- Adams, James (2012). ‘Causes and Electoral Consequences of Party Policy Shifts in Multiparty Elections: Theoretical Results and Empirical Evidence’, Annual Review of Political Science, 15:1, 401–19.

- Adams, James, Michael Clark, Lawrence Ezrow, and Garret Glasgow (2006). ‘Are Niche Parties Fundamentally Different from Mainstream Parties? The Causes and the Electoral Consequences of Western European Parties’ Policy Shifts, 1976–1998’, American Journal of Political Science, 50:3, 513–29.

- Adams, James, and Zeynep Somer-Topcu (2009). ‘Policy Adjustment by Parties in Response to Rival Parties’ Policy Shifts: Spatial Theory and the Dynamics of Party Competition in Twenty-Five Post-War Democracies’, British Journal of Political Science, 39:4, 825–46.

- Bakker, Ryan, and Sara Hobolt (2013). ‘Measuring Party Positions’, in Geoffrey Evans and Nan Dirk De Graaf (eds.), Political Choice Matters: Explaining the Strength of Class and Religious Cleavages in Cross-National Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 27–45.

- Bergman, Matthew E., and Henry Flatt (2020). ‘Issue Diversification: Which Niche Parties Can Succeed Electorally by Broadening Their Agenda?’, Political Studies, 68:3, 710–30.

- Bischof, Daniel, and Markus Wagner (2020). ‘What Makes Parties Adapt to Voter Preferences? The Role of Party Organization, Goals and Ideology’, British Journal of Political Science, 50:1, 391–401.

- Bolleyer, Nicole (2009). ‘Inside the Cartel Party: Party Organisation in Government and Opposition’, Political Studies, 57:3, 559–79.

- Budge, Ian (2000). ‘Expert Judgements of Party Policy Positions: Uses and Limitations in Political Research’, European Journal of Political Research, 37:1, 103–13.

- Budge, Ian, Lawrence Ezrow, and Michael D. McDonald (2010). ‘Ideology, Party Factionalism and Policy Change: An Integrated Dynamic Theory’, British Journal of Political Science, 40:4, 781–804.

- Budge, Ian, and Dennis Farlie (1983). ‘Party Competition: Selective Emphasis or Direct Confrontation? An Alternative View with Data’, in Hans Daalder and Peter Mair (eds.), Western European Party Systems: Continuity and Change. London: Sage Publications, 267–305.

- Clark, Tom S., and Drew A. Linzer (2015). ‘Should I Use Fixed or Random Effects?’, Political Science Research and Methods, 3:2, 399–408.

- De Sio, Lorenzo, and Till Weber (2014). ‘Issue Yield: A Model of Party Strategy in Multidimensional Space’, American Political Science Review, 108:4, 870–85.

- Dolezal, Martin, Laurenz Ennser-Jedenastik, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Anna Katharina Winkler (2014). ‘How Parties Compete for Votes: A Test of Saliency Theory’, European Journal of Political Research, 53:1, 57–76.

- Döring, Holger, Constantin Huber, and Philip Manow (2022). ParlGov 2022 Release (V1) [Data set]. Harvard Dataverse. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/UKILBE

- Downs, Anthony (1957). An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper and Row.

- European Social Survey (2020). European Social Survey Cumulative File, ESS 1–9. Data File Edition 1.1, NSD – Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Norway – Data Archive and Distributor of ESS Data for ESS ERIC. Retrieved from https://ess-search.nsd.no/CDW/RoundCountry

- Ezrow, Lawrence (2008). ‘Research Note: On the Inverse Relationship between Votes and Proximity for Niche Parties’, European Journal of Political Research, 47:2, 206–20.

- Ezrow, Lawrence, Catherine De Vries, Marco Steenbergen, and Erica Edwards (2011). ‘Mean Voter Representation and Partisan Constituency Representation: Do Parties Respond to the Mean Voter Position or to Their Supporters?’, Party Politics, 17:3, 275–301.

- Freire, André (2015). ‘Left–Right Ideology as a Dimension of Identification and of Competition’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 20:1, 43–68.

- Gerbaudo, Paolo (2021). ‘Are Digital Parties More Democratic than Traditional Parties? Evaluating Podemos and Movimento 5 Stelle’s Online Decision-Making Platforms’, Party Politics, 27:4, 730–42.

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer (2007). ‘The Growing Importance of Issue Competition: The Changing Nature of Party Competition in Western Europe’, Political Studies, 55:3, 607–28.

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer, and Peter B. Mortensen (2010). ‘Who Sets the Agenda and Who Responds to It in the Danish Parliament? A New Model of Issue Competition and Agenda-Setting’, European Journal of Political Research, 49:2, 257–81.

- Harmel, Robert, and Kenneth Janda (1994). ‘An Integrated Theory of Party Goals and Party Change’, Journal of Theoretical Politics, 6:3, 259–87.

- Ignazi, Piero (2020). ‘The Four Knights of Intra-Party Democracy: A Rescue for Party Delegitimation’, Party Politics, 26:1, 9–20.

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Hans-Dieter Klingemann (1976). ‘Party Identification, Ideological Preference and the Left-Right Dimension among Western Mass Publics’, in Ian Budge, Ivor Crewe, and Dennis Farlie (eds.), Party Identification and Beyond: Representations of Voting and Party Competition. Colchester: ECPR Press, 243–73.

- Johns, Robert, and Ann-Kristin Kölln (2020). ‘Moderation and Competence: How a Party’s Ideological Position Shapes Its Valence Reputation’, American Journal of Political Science, 64:3, 649–63.

- Jolly, Seth, Ryan Bakker, Liesbet Hooghe, Gary Marks, Jonathan Polk, Jan Rovny, Marco Steenbergen et al. (2022). ‘Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File, 1999–2019’, Electoral Studies, 75:February, 102420.

- Joon Han, Kyung (2017). ‘It Hurts When It Really Matters: Electoral Effect of Party Position Shift regarding Sociocultural Issues’, Party Politics, 23:6, 821–33.

- Jungar, Ann-Cathrine (2016). ‘From the Mainstream to the Margin? The Radicalisation of the True Finns’, in Tjitske Akkerman, Sarah L. de Lange, and Matthijs Rooduijn (eds.), Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe: Into the Mainstream?. London: Routledge, 113–43.

- Kaltenegger, Matthias, Katharina Heugl, and Wolfgang C. Müller (2021). ‘Appeasement and Rewards: Explaining Patterns of Party Responsiveness towards Activist Preferences’, Party Politics, 27:2, 363–75.

- Kitschelt, Herbert (1988). ‘Left-Libertarian Parties: Explaining Innovation in Competitive Party Systems’, World Politics, 40:2, 194–234.

- Kitschelt, Herbert (2013). Democratic Accountability and Linkages Project. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Koedam, Jelle (2022a). ‘A Change of Heart? Analysing Stability and Change in European Party Positions’, West European Politics, 45:4, 693–715.

- Koedam, Jelle (2022b). ‘Who’s at the Helm? When Party Organization Matters for Party Strategy’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 32:2, 251–74.

- Kölln, Ann-Kristin (2015). ‘The Effects of Membership Decline on Party Organisations in Europe’, European Journal of Political Research, 54:4, 707–25.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Tobias Frey (2008). West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Küppers, Anne (2021). ‘Effects of Party Primaries in German Regional Party Branches’, German Politics, 30:2, 208–26.

- Laver, Michael (2005). ‘Policy and the Dynamics of Political Competition’, American Political Science Reivew, 99:2, 263–81.

- Laver, Michael, and W. Ben Hunt (1992). Policy and Party Competition. London: Routledge.

- Lehmann, Pola, Tobias Burst, Jirka Lewandowski, Theres Matthieß, Sven Regel, and Lisa Zehnter (2022). Manifesto Corpus. Version: 2022-a. Berlin: WZB Berlin Social Science Center.

- Lieberman, Evan S. (2005). ‘Nested Analysis as a Mixed-Method Strategy for Comparative Research’, American Political Science Review, 99:3, 435–52.

- Lowe, Will, Kenneth Benoit, Slava Mikhaylov, and Michael Laver (2011). ‘Scaling Policy Preferences from Coded Political Texts’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 36:1, 123–55.

- Maeda, Ko (2016). ‘What Motivates Moderation? Policy Shifts of Ruling Parties, Opposition Parties and Niche Parties’, Representation, 52:2-3, 215–26.

- May, John D. (1973). ‘Opinion Structure of Political Parties: The Special Law of Curvilinear Disparity’, Political Studies, 21:2, 135–51.

- Meguid, Bonnie M. (2008). Party Competition between Unequals: Strategies and Electoral Fortunes in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Meyer, Thomas M. (2013). Constraints on Party Policy Change. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Meyer, Thomas M., and Markus Wagner (2019). ‘It Sounds Like They Are Moving: Understanding and Modeling Emphasis-Based Policy Change’, Political Science Research and Methods, 7:04, 757–74.

- Meyer, Thomas M., and Markus Wagner (2020). ‘Perceptions of Parties’ Left-Right Positions: The Impact of Salience Strategies’, Party Politics, 26:5, 664–74.

- Müller, Wolfgang C., and Kaare Strøm (1999). Policy, Office, or Votes? How Political Parties in Western Europe Make Hard Decisions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Panebianco, Angelo (1988). Political Parties: Organization and Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pedersen, Helene Helboe (2012a). ‘Policy-Seeking Parties in Multiparty Systems: Influence or Purity?’, Party Politics, 18:3, 297–314.

- Pedersen, Helene Helboe (2012b). ‘What Do Parties Want? Policy versus Office’, West European Politics, 35:4, 896–910.

- Pereira, Miguel M. (2020). ‘Responsive Campaigning: Evidence from European Parties’, The Journal of Politics, 82:4, 1183–95.

- Pizzimenti, Eugenio, Enrico Calossi, and Lorenzo Cicchi (2022). ‘Removing the Intermediaries? Patterns of Intra-Party Organizational Change in Europe (1970–2010)’, Acta Politica, 57:1, 191–209.

- Plescia, Carolina, Sylvia Kritzinger, and Lorenzo De Sio (2019). ‘Filling the Void? Political Responsiveness of Populist Parties’, Representation, 55:4, 513–33.

- Poguntke, Thomas, Susan E. Scarrow, Paul D. Webb, Elin H. Allern, Nicholas Aylott, Ingrid van Biezen et al. (2016). ‘Party Rules, Party Resources and the Politics of Parliamentary Democracies: How Parties Organize in the 21st Century’, Party Politics, 22:6, 661–78.

- Rohlfing, Ingo (2015). ‘Asset or Liability? An Analysis of the Effect of Changes in Party Membership on Partisan Ideological Change’, Party Politics, 21:1, 17–27.

- Rohrschneider, Robert, and Stephen Whitefield (2012). The Strain of Representation: How Parties Represent Diverse Voters in Western and Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sánchez-Cuenca, Ignacio (2004). ‘Party Moderation and Politicians’ Ideological Rigidity’, Party Politics, 10:3, 325–42.

- Sandri, Giulia, and Antonella Seddone (2016). ‘Introduction: Primary Elections across the World’, in Giulia Sandri, Antonella Seddone and Fulvio Venturino (eds.), Party Primaries in Comparative Perspective. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 19–38.

- Sani, Giacomo, and Giovanni Sartori (1983). ‘Polarization, Fragmentation and Competition in Western Democracies’, in Hans Daalder and Peter Mair (eds.), Western European Party Systems: Continuity and Change. London: SAGE Publications, 307–40.

- Scarrow, Susan, Paul D. Webb, and Thomas Poguntke (2022). Political Party Database Round 2 v4 (First Public Version). Harvard Dataverse, V1. Retrieved from https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/0JVUM8

- Schumacher, Gijs, Catherine E. De Vries, and Barbara Vis (2013). ‘Why Do Parties Change Position? Party Organization and Environmental Incentives’, The Journal of Politics, 75:2, 464–77.

- Schumacher, Gijs, and Nathalie Giger (2017). ‘Who Leads the Party? On Membership Size, Selectorates and Party Oligarchy’, Political Studies, 65:1_suppl, 162–81.

- Schumacher, Gijs, and Nathalie Giger (2018). ‘Do Leadership-Dominated Parties Change More?’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 28:3, 349–60.

- Seawright, Jason, and John Gerring (2008). ‘Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options’, Political Research Quarterly, 61:2, 294–308.

- Somer-Topcu, Zeynep (2009). ‘Timely Decisions: The Effects of Past National Elections on Party Policy Change’, The Journal of Politics, 71:1, 238–48.

- Spoon, Jae-Jae (2009). ‘Holding Their Own: Explaining the Persistence of Green Parties in France and the UK’, Party Politics, 15:5, 615–34.

- Spoon, Jae-Jae, and Heike Klüver (2019). ‘Party Convergence and Vote Switching: Explaining Mainstream Party Decline across Europe’, European Journal of Political Research, 58:4, 1021–42.

- Spoon, Jae-Jae, and Christopher J. Williams (2021). ‘“It’s the Economy, Stupid”: When New Politics Parties Take on Old Politics Issues’, West European Politics, 44:4, 802–24.

- Strøm, Kaare (1990). ‘A Behavioral Theory of Competitive Political Parties’, American Journal of Political Science, 34:2, 565–98.

- Tavits, Margit (2007). ‘Principle vs. Pragmatism: Policy Shifts and Political Competition’, American Journal of Political Science, 51:1, 151–65.

- Tromborg, Mathias Wessel (2015). ‘Space Jam: Are Niche Parties Strategic or Looney?’, Electoral Studies, 40, 189–99.

- Tsebelis, George (1990). Nested Games: Rational Choice in Comparative Politics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- van Haute, Emilie, and Emilien Paulis (2016). MAPP Dataset [Dataset], Zenodo. Retrieved from https://zenodo.org/records/61234

- Van Holsteyn, Joop J. M., Josje M. Den Ridder, and Ruud A. Koole (2017). ‘From May’s Laws to May’s Legacy: On the Opinion Structure within Political Parties’, Party Politics, 23:5, 471–86.

- Wager, Alan, Tim Bale, Philip Cowley, and Anand Menon (2022). ‘The Death of May’s Law: Intra-and Inter-Party Value Differences in Britain’s Labour and Conservative Parties’, Political Studies, 70:4, 939–61.

- Wagner, Markus (2012). ‘Defining and Measuring Niche Parties’, Party Politics, 18:6, 845–64.

- Wagner, Markus, and Thomas M. Meyer (2014). ‘Which Issues Do Parties Emphasise? Salience Strategies and Party Organisation in Multiparty Systems’, West European Politics, 37:5, 1019–45.

- Webb, Paul, Susan Scarrow, and Thomas Poguntke (2022). ‘Party Organization and Satisfaction with Democracy: Inside the Blackbox of Linkage’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 32:1, 151–72.

- Wolkenstein, Fabio (2018a). ‘Intra-Party Democracy beyond Aggregation’, Party Politics, 24:4, 323–34.

- Wolkenstein, Fabio (2018b). ‘Membership Ballots and the Value of Intra-Party Democracy’, Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 21:4, 433–55.

- Zons, Gregor (2016). ‘How Programmatic Profiles of Niche Parties Affect Their Electoral Performance’, West European Politics, 39:6, 1205–29.